Materialism and the Task of Anthroposophy

GA 204

30 April 1921, Dornach

Lecture XI

In the course of these lectures we have seen that the middle of the nineteenth century is an important time in the development of Western humanity. Attention was called to the fact that in a sense the culmination of the materialistic way of thinking and the materialistic world view occurred during this time. Yet it also had to be pointed out that this trend that has emerged in the human being since the fifteenth century was really something spiritual. Thus, it can be said that the characteristic of this developmental phase of recent human evolution was that simultaneously with becoming the most spiritual, the human being could not take hold of this spirituality. Instead, human beings filled themselves only with materialistic thinking, feeling, and even with materialistic will and activity. Our present age is still dominated by the aftereffects of what occurred in so many people without their being aware of it, and then reached its climax in mankind's development. What was the purpose of this climax? It occurred because something decisive was meant to take place in regard to contemporary humanity's attainment of the consciousness soul stage.

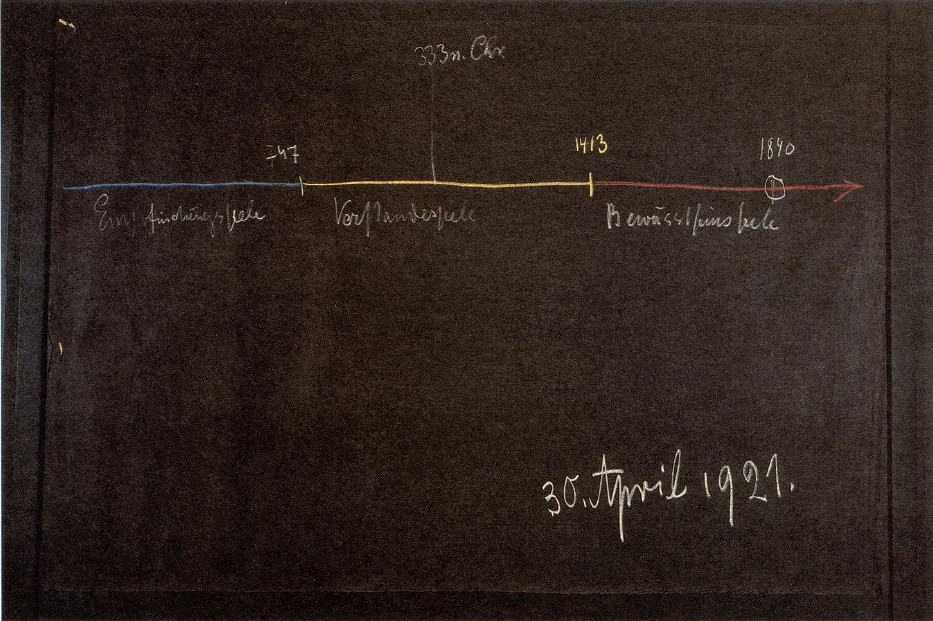

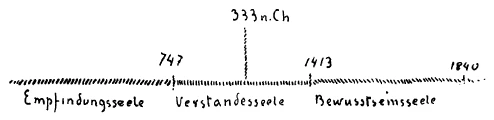

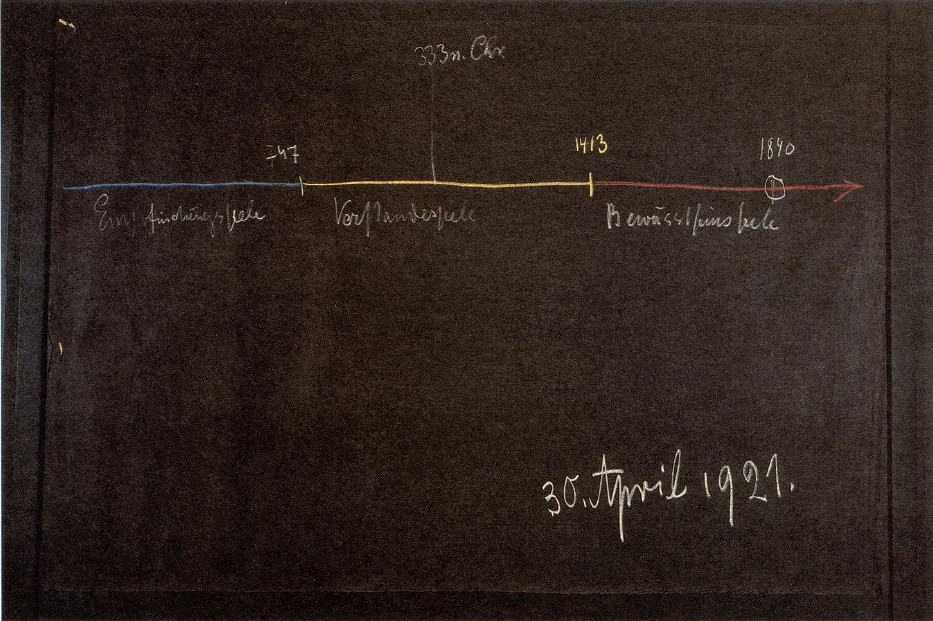

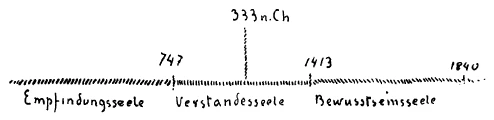

In focusing on the evolution of humanity from the third post-Atlantean epoch until approximately the year 747 (see sketch) before the Mystery of Golgotha, we find that a process runs its course that can be called the development of the sentient soul in humanity. Then the age of the rational or mind soul begins and lasts roughly until the year 1413. It reaches its high point in that era of which external history has little to report. It must be taken into consideration, however, if European development is to be comprehended at all. This culmination point occurs approximately in the year 333 after Christ. Since the year 1413, we are faced with the development of the consciousness soul, a development we are still involved in and that saw a decisive event around the year 1850, or better, 1840.

A.D.333

----------747-----------/-------------1413----------1840

Sentient Soul........Rational Soul....Consciousness Soul

For mankind as a whole, matters had reached a point around 1840 where, insofar as the representative personalities of the various nations are concerned, we can say that they were faced with an intellect that had already assumed its most shadowy form. (Following this, we shall have to consider the reaction of the individual nations.) The intellect had assumed its shadow-like character. I tried yesterday to characterize this shadow nature of the intellect. People in the civilized world had evolved to the extent that, from then on it was possible on the basis of the general culture and without initiation to acquire the feeling: We possess intellect. The intellect has matured, but insofar as its own nature is concerned, it no longer has a content. We have concepts but these concepts are empty. We must fill them with something.

This, in a sense, is the call passing through humanity, though dimly and inaudibly. But in the deep, underlying, subconscious longings of human beings lives the call, the wish to receive a content, substance, for the shadow nature of rational thinking. Indeed, it is the call for spiritual science.

This call can also be comprehended concretely. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the human organization, in the physical part of which this shadowy intellect is trained, had simply progressed to the point where it could cultivate this empty shadowy intellect particularly well. Now, something was required for this shadowy intellect; it had to be filled with something. This could only happen if the human being realized: I have to assimilate something of what is not offered to me on the earth itself and does not dwell there, something I cannot learn about in the life between birth and death. I actually have to absorb something into my intellect that, although it was extinguished and became obscured when I descended with the results of my former earth lives out of spiritual soul worlds into a physical corporeality, nevertheless rests in the depths of my soul. From there, I have to bring it up once again, I have to call to mind something that rests within me simply by virtue of the fact that I am a human being of the nineteenth century.

Earlier, it would not have been possible for human beings to have practiced self-awareness in the same manner. This is why they first had to advance in their human condition to the point where the physical body increasingly acquired the maturity to perfect and utilize the shadowy intellect completely. Now, at least among the most advanced human beings, the physical bodies had reached the point where one could have said, or rather, since then it is possible to say: I wish to call to mind what it is that I am seeking to bring up from the depths of my soul life in order to pour a content into this shadowy intellect. This shadowy intellect would have been filled with something and in this way the consciousness soul age would have dawned. Therefore, at this point in time, the occasion arose where the consciousness soul could have unfolded.

Now you will say: Yes, but the whole era prior to that, beginning with the year 1413, was the age of the consciousness soul. Yes, certainly, but at first it has been a preparatory development. You need only consider what basic conditions existed for such a preparation particularly in this period as compared to all earlier times. Into this period falls, for example, the invention of the printing press; the dissemination of the written word. Since the fifteenth century, people by and by have received a great amount of spiritual content by means of the art of printing and through writing. But they absorb this content only outwardly; it is the main feature of this period that an overwhelming sum of spiritual content has been assimilated superficially. The nations of the civilized world have absorbed something outwardly which the great masses of people could receive only by means of audible speech in earlier times. It was true of the period of rational development, and in the age of the sentient soul it was all the more true that, fundamentally speaking, all dissemination of learning was based on oral teaching. Something of the psycho-spiritual element still resounds through speech. Especially in former days, what could be termed “the genius of language” definitely still lived in words. This ceased to be when the content of human learning began to be assimilated in abstract forms, through writing and printed works. Printed and written words have the peculiarity of in a sense extinguishing what the human being brings with him at birth from his pre-earthly, heavenly existence.

It goes without saying that this does not mean that you should forthwith cease to read or write. It does mean that today a more powerful force is needed in order to raise up what lies deep within the human being. But it is necessary that this stronger force be acquired. We have to arrive at self-awareness despite the fact that we read and write; we have to develop this stronger faculty, stronger in comparison to what was needed in earlier times. This is the task in the age of the development of the consciousness soul.

Before taking a look at how the influences of the spiritual world have now started to flow down in a certain way into the physical, sensory world, let us pose the question today, How did the nations of modern civilization actually meet this point of time in 1840?

From earlier lectures we know that the representative people for the development of the consciousness soul, hence for what matters particularly in our age, is the Anglo-Saxon nation. The Anglo-Saxon people are those who through their whole organization are predisposed to develop the consciousness soul to a special degree. The prominent position occupied by the Anglo-Saxon nation in our time is indeed due to the fact that this nation is especially suited for the development of the consciousness soul. But now let us ask ourselves from a purely external viewpoint, How did this Anglo-Saxon nation arrive at this point in time that is the most significant one in modern cultural development?

It can be said that the Anglo-Saxon nation in particular has survived for a long time in a condition—naturally with the corresponding variations and metamorphoses—that could perhaps be described best by saying, Those inner impulses, which had already made way for other forms in Greek culture, were preserved in regard to the inner soul condition of the Anglo-Saxon people. The strange thing in the eleventh and tenth centuries B.C. is that the nations experienced what is undergone at different periods, that the various ages move, as it were, one on top of the other. The problem is that such matters are extraordinarily difficult to notice because in the nineteenth century all sorts of things already existed—reading, writing—and because the living conditions prevailing in Scotland and England were different from those in Homeric times.

And yet, if the soul condition of the people as a nation is taken into consideration, the fact is that this soul condition of the Homeric era, which in Greece was outgrown in the tragic age and changed into Sophoclism, has remained. This age, a kind of patriarchal conception of life and existence, was preserved in the Anglo-Saxon world up until the nineteenth century. In particular, this patriarchal life spread out from the soul condition in Scotland. This is the reason why the influence proceeding from the initiation centers in Ireland did not have an effect on the Anglo-Saxon nation. As was mentioned on other occasions, that influence predominantly affected continental Europe. On the British isle itself, the predominant influence originated from initiation truths that came down from the north, from Scotland. These initiation truths then permeated everything else. But there is an element in the whole conception of the human personality that, in a sense, has remained from primordial times. This still has aftereffects; it lingers on even in the way, say, the relationship between Whigs and Tories develops in the British Parliament. The fact is that fundamentally we are not dealing with the difference between liberal and conservative views. Instead, we have to do with two political persuasions for which people today really have no longer any perception at all.

Essentially, the Whigs are the continuation of what could be called a segment of mankind imbued with a general love of humanity and originating in Scotland. According to a fable, which does have a certain historical background, the Tories were originally Catholicizing horse thieves from Ireland. This contrast, which then expressed itself in their particular political strivings, reflects a certain patriarchal existence. This patriarchal existence retained certain primitive forces, which can be observed in the kind of attitude exhibited by the owners of large properties toward those people who had settled on these lands as their vassals.

This relationship of subservience actually lasted until the nineteenth century; nobody was elected to Parliament who did not possess a certain power by virtue of being a landowner. We only have to consider what this implies. Such matters are not weighed in the right manner. Just think what it signifies, for example, that it was not until the year 1820 that English Parliament repealed the law according to which a person was given the death penalty for having stolen a pocket watch or having been a poacher. Until then, the law decreed that such misdeeds were capital offenses. This certainly demonstrates the way in which particular, ancient, and elementary conditions had remained. Today, people observe life in their immediate surroundings and then extend the fundamental aspects of present-day civilization backwards, so to speak. In regard to the most important regions of Europe, they are unaware of how recently these things have developed from quite primitive conditions.

Thus, it is possible to say that these patriarchal conditions survived as the foundation and basis of a society that was subsequently infused with the most modern impulse, unimaginable in the social structure without the development of the consciousness soul. Just consider all the changes in the social structure of the eighteenth century due to the technological metamorphosis in the textile industry and the like. Note how the mechanical, technological element moved into this patriarchal element. Try to form a clear idea of how, owing to the transformation of the textile industry, the nascent modern Proletariat pushes into the social structure that is based on this patriarchal element, this relationship of landowner to subjects. Just think of this chaotic intermingling, think how the cities develop in the ancient countryside and how the patriarchal attitude takes a daring plunge, so to say, into modern, socialistic, proletarian life.

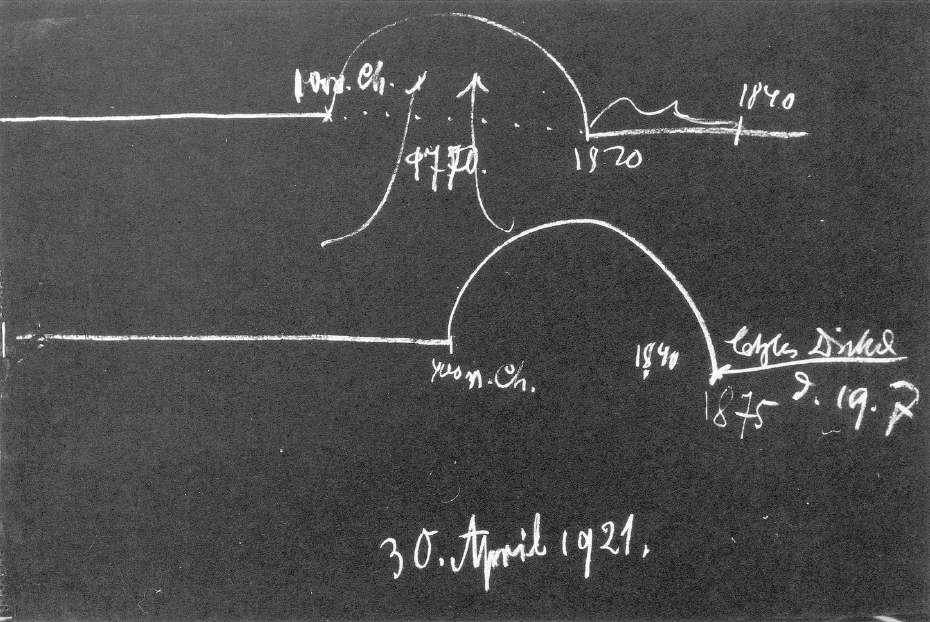

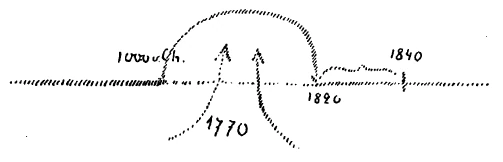

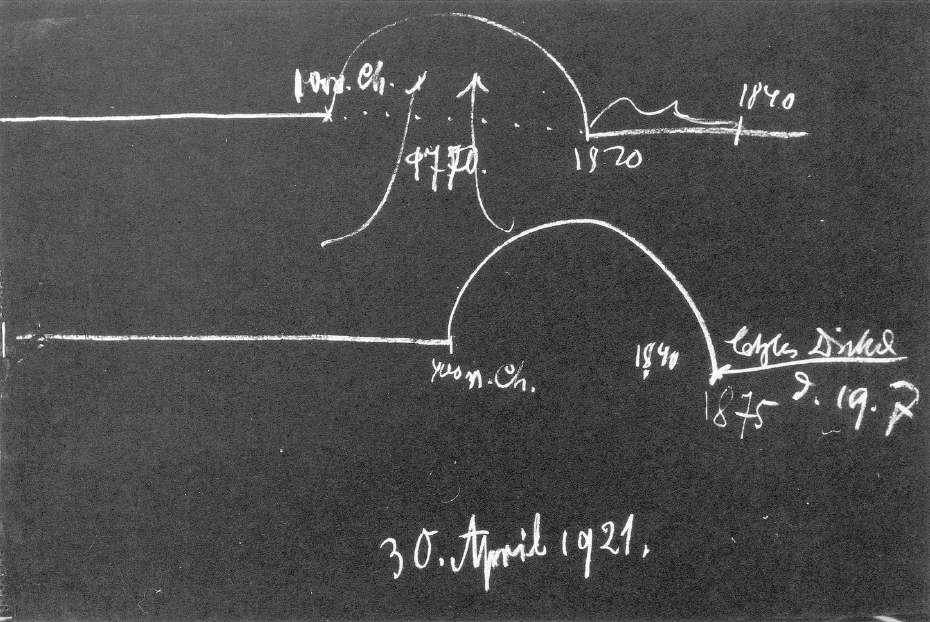

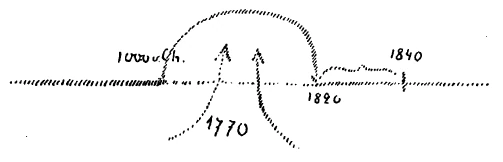

To picture it graphically, we can actually say that this form of life develops in the way it existed in Greece approximately until the year 1000 B.C. (see drawing). Then it makes a daring jump and we suddenly find ourselves in the year A.D. 1820. Inwardly, the life of the year 1000 B.C. has been retained, but outwardly, we are in the eighteenth century, say 1770 (see arrows). Now everything that then existed in modern life, indeed, even in our present time, pours in. But it is not until 1820 that this English life makes the connection, finds it necessary to do so (see drawing); it is not until then that these matters even became issues, such as the abolition of the death penalty for a minor theft. Thus we can say that, here, something very old has definitely flown together with the most modern element. Thus, the further development then continues on to the year 1840.

Now, what had to occur specifically among the Anglo-American people during this time period, the first half of the nineteenth century? We have to recall that only after the year 1820, actually not until after 1830, it became necessary to pass laws in England according to which children under twelve years of age were not allowed to be kept working in factories for more than eight hours a day, no more than twelve hours a day in the case of children between thirteen and eighteen years of age. Please, compare that with today's conditions! Just think what the broad masses of working people demand today as the eight-hour day! As yet, in the year 1820, boys were put to work in mines and factories in England for more than eight hours; only in that year was the eight-hour day established for them. The twelve-hour day still prevailed, however, in regard to children between twelve and eighteen.

These things must certainly be considered in the attempt to figure out the nature of the elements colliding with each other at that time. Basically, it could be said that England eased its way out of the patriarchal conditions only in the second third of the nineteenth century and found it necessary to reckon with what had slowly invaded the old established traditions due to technology and the machine. It was in this way that this nation, which is preeminently called upon to develop the consciousness soul, confronted the year 1840.

Now take other nations of modern civilization. Take what has remained of the Latin-Roman element; take what has carried over the Latin-Roman element from the fourth post-Atlantean cultural period, what has brought over the ancient culture of the intellectual soul as a kind of legacy into the epoch of the consciousness soul. Indeed, what had remained of this life of the intellectual soul reached its highest point, its culmination, in the French Revolution at the end of the eighteenth century. We note that the ideals, freedom, equality, and brotherhood appear all at once in the most extreme abstraction. We see them taken up by skeptics such as Voltaire,1Francois de Voltaire (actually d'Arouet), 1694–1778, French philosopher of the Enlightenment. by enthusiasts such as Rousseau;2Jean Jacques Rousseau, 1712–1778, French philosopher and pedagogue. we see them emerge generally in the broad masses of the people. We see how the abstraction, which is fully justified in this sphere, affects the social structure

It is a completely different course of events from the one over in England. In England, the vestiges of the old Germanic patriarchal life are permeated by what the element of modern technology and modern materialistic, scientific life could incorporate into the social structure. In France, we have tradition everywhere. We could say that the French Revolution has been enacted in the same manner in which a Brutus or a Caesar once acted in the most diverse ways in ancient Rome. Thus, here also, freedom, equality and brotherhood surfaced in abstract forms. Unlike in England, the old existing patriarchal element was not destroyed from the outside. Instead, the Roman juridical tradition, the adherence to the ancient concept of property and ownership of land, inheritance laws, and so on, what had been established in the Roman-juristic tradition was corroded by abstraction, driven asunder by abstraction.

We need only consider the tremendous change the French Revolution brought to all of European life. We only need remind ourselves that prior to the French Revolution those who, in a sense, distinguished themselves from the masses of the nation also had legal privileges. Only certain people could aspire to particular positions in government. What the French Revolution demanded based on abstraction and the shadowlike intellect was to make breaches into that system to undermine it. But it did bear the stamp of the shadowy intellect, the abstraction. Therefore, the demands that were being made fundamentally remained a kind of ideology. For this reason, we can say that anything that is of the shadowy intellect immediately turns into its opposite.

Then we observe Napoleonism; we watch the experimentation in the public and social realm during the course of the nineteenth century. The first half of the nineteenth century was certainly experimentation without a goal in France. What is the nature of the events through which somebody like Louis-Philippe, for example, becomes king of France, and so on—what sort of experimenting is carried out? It is done in such a way that one can recognize that the shadowy intellect is incapable of truly intervening in the actual conditions. Everything basically remains undone and incomplete; it all remains as legacy of ancient Romanism. We are justified in saying that even today the relationship to, say, the Catholic Church, which the French Revolution had quite clearly defined in abstraction, has not been clarified in France in external, concrete reality. And how unclear was it time and again in the course of the nineteenth century! Abstract reasoning had struggled up to a certain level during the Revolution; then came experimentation and the inability to cope with external conditions. In this way, this nation encountered the year 1840.

We can also consider other nations. Let us look at Italy, for instance, which, in a manner of speaking, still retained a bit of the sentient soul in its passage through the culture of the intellect. It brought this bit of the sentient soul into modern times and therefore did not advance as far as the abstract concepts of freedom, equality, and brotherhood attained in the French Revolution. It did, however, seek the transition from a certain ancient group consciousness to individual consciousness in the human being. Italy faced the year 1840 in a manner that allows us to say, The individual human consciousness trying to struggle to the fore in Italy was in fact constantly held down by what the rest of Europe now represented. We can observe how the tyranny of Habsburg weighed terribly on the individual human consciousness that tried to develop in Italy. We see in the 1820's the strange Congress of Verona3Congress of Verona: Congress of the “Holy Alliance” (1822) to which all the European powers belonged with the exception of England and the Vatican. Under Metternich, it pursued a clearly reactionary course. that tried to determine how one could rise up against the whole substance of modern civilization. We note that there proceeded from Russia and Austria a sort of conspiracy against what the modern consciousness in humanity was meant to bring. There is hardly anything as interesting as the Congress of Verona, which basically wished to answer the question: How does one go about exterminating everything that is trying to emerge as modern consciousness in mankind?

Then we see how the people in the rest of Europe struggled in certain ways. Particularly in Central Europe, only a small percentage of the population was able to attain to a certain consciousness, experiencing in a certain manner that the ego is now supposed to enter into the consciousness soul. We notice attempts to achieve this at a certain high mental level. We can see it in the peculiar high cultural level of Goethe's age in which a man like Fichte was active;4Johann Gottlieb Fichte, 1762–1814, German philosopher. we see how the ego tried to push forward into the consciousness soul. Yet we also realize that the whole era of Goethe actually was something that lived only in few individuals. I believe people study far too little what even the most recent past was like. They simply think, for example the Goethe lived from 1749 until 1832; he wrote Faust and a number of other works. That is what is known of Goethe and that knowledge has existed ever since.

Until the year 1862, until thirty years after Goethe's death, with few exceptions, it was impossible for people to acquire a copy of Goethe's works. They were restricted; only a handful of people somehow owned a copy of his writings. Hence, Goetheanism had become familiar only to a select few. It was not until the 1860's that a larger number of people could even find out about the particular element that lived in Goethe. By that time, the faculty of comprehension for it had disappeared again. An actual understanding of Goethe never really came about, and the last third of the nineteenth century was not suited at all for such comprehension.

I have often mentioned that in the 1870's Hermann Grimm gave his “Lectures on Goethe” at the University of Berlin.5Hermann Grimm, 1828–1901, German art historian and literary critic. That was a special event and the book that exists as Hermann Grimm's Goethe is a significant publication in the context of central European literature. Yet, if you now take a look at this book, what is its substance? Well, all the figures who had any connection with Goethe are listed in it but they are like shadow images having only two dimensions. All these portrayals are shadow figures, even Goethe is a two-dimensional being in Hermann Grimm's depiction. It is not Goethe himself. I won't even mention the Goethe whom people at the afternoon coffee parties of Weimar called “the fat Privy Councillor with the double chin.” In Hermann Grimm's Goethe, Goethe has no weight at all. He is merely a two-dimensional being, a shadow cast on the wall. It is the same with all the others who appear in the book; Herder—a shadow painted on a wall. We encounter something a little more tangible in Hermann Grimm's description of those persons coming from among the ordinary people who are close to Goethe, for example, Friederike von Sesenheim who is portrayed there so beautifully, or Lilli Schoenemann from Frankfurt—hence those who emerge from a mental atmosphere other than the one in which Goethe lived. Those are described with a certain “substance.” But figures like Jacobi and Lavater are but shadow images on a wall. The reader does not penetrate into the actual substance of things; here, we can observe in an almost tangible way the effects of abstraction. Such abstraction can certainly be charming, as is definitely the case with Hermann Grimm's book, but the whole thing is shadowy. Silhouettes, two-dimensional beings, confront us in it.

Indeed, it could not be otherwise. For it is a fact that a German could not call himself a German in Germany at the time when Hermann Grimm, for example was young. The way one spoke of Germans during the first half of the nineteenth century is misunderstood, particularly at present. How “creepy” it seems to people in the West, those of the Entente, when they start reading Fichte's Addresses to the German Nation today and find him saying: “I speak simply to Germans, to Germans as such.” In the same way, the harmless song “Germany, Germany above all else”T1“Deutschland, Deutschland über alles,” the German national anthem. is interpreted foolishly, for this song means nothing more than the desire to be a German, not a Swabian, a Bavarian, an Austrian, a Franconian, or Thuringian. Just as this song referred only to Germans as such, so Fichte wished simply to address himself to Germans, not to Austrians, Bavarians, those from the province of Baden, Wuerttemberg, Franconia, or Prussia; he wanted to speak “to Germans.” This is naturally impossible to understand, for instance, in a country where it has long since become a matter of course to call oneself a Frenchman. However, in certain periods in Germany, you were imprisoned if you called yourself German. You could call yourself an Austrian, a Swabian, a Bavarian, but it amounted to high treason to call yourself a German. Those who called themselves Germans in Bavaria expressed the sentiment that they did not wish to look up merely to the Bavarian throne and its reign within Bavaria's clearly defined borders, but implied that they also wished to look beyond the borders of Bavaria. But that was high treason! People were not permitted to call themselves Germans.

It is not understood at all today that these things that are said about Germans and Germany, refer to this unification of everything German. Instead, the absurd nonsense is spread that, for example, Hoffmann's song refers to the notion that Germany should rule over all the nations of the world although it means nothing else but: Not Swabia, not Austria, not Bavaria above all else in the world, but Germany above all else in the world, just as the Frenchman says: France above all else in the world. It was, however, the peculiar nature of Central Europe that basically a tribal civilization existed there. Even today, you can see this tribal culture everywhere in Germany. A Wuerttembergian is different from a Franconian. He differs from him even in the formulation of concepts and words, indeed, even in the thought forms disseminated in literature. There really is a marked difference, if you compare, say, a Franconian, such as cloddy Michael Conrad—using modern literature as an example—with something that has been written at the same time by a Wuerttembergian, hence in the neighboring province.

Something like this plays into the whole configuration of thoughts right into the present time. But everything that persists in this way and lives in the tribal peculiarities remains untouched by what is now achieved by the representatives of the nations. After all, in the realm commonly called Germany something has been attained such as Goetheanism with all that belongs to it. But it has been attained by only a few intellectuals; the great masses of people remain untouched by it. The majority of the population has more or less maintained the level of central Europe around the year A.D. 300 or 400. Just as the Anglo-Saxon people have stayed on the level of around the year 1000 B.C., people in Central Europe have remained on the level of the year A.D. 400. Please do not take this in the sense that a terrible arrogance might arise with the thought that the Anglo-Saxons have remained behind in the Homeric age, and we were already in the year A.D. 400. This is not the way to evaluate these matters. I am only indicating certain peculiarities.

In turn, the geographic conditions reveal that this level of general soul development in Germany lasted much longer than in England. England's old patriarchal life had to be permeated quickly with what formed the social structure out of the modern materialistic, scientific, and technological life first in the area of the textile industry, and later also in the area of other technologies. The German realm and Central Europe in general opposed this development initially, retaining the ancient peculiarities much longer. I might say, they retained them until a point in time when the results of modern technology already prevailed fully all over the world. To a certain extent, England caught up in the transformation of the social structure in the first half of the nineteenth century. Everything that was achieved there definitely bypassed central Europe.

Now, Central Europe did absorb something of abstract revolutionary ideas. They came to expression through various movements and stirrings in the 1840's in the middle of the nineteenth century. But this region sat back and waited, as it were, until technology had infused the whole world. Then, a strange thing happened. An individual—we could also take other representatives—who in Germany had acquired his thinking from Hegelianism, namely, Karl Marx, went over to England, studied the social structure there and then formulated his socialist doctrines. At the end of the nineteenth century, Central Europe was then ready for these social doctrines, and they were accepted there. Thus, if we tried to outline in a similar manner what developed in this region, we would have to say: The development progressed in a more elementary way even though a great variety of ideas were absorbed from outside through books and printed matter.

The conditions of A.D. 400 in central Europe continued on, then made a jump and basically found the connection only in the last third of the nineteenth century, around the year 1875. Whereas the Anglo-Saxon nation met already the year 1840 with a transformation of conditions, with the necessity of receiving the consciousness soul, the German people continued to dream. They still experienced the year 1840 as though in a dream. Then they slept through the grace period when a bridge could have been built between leading personalities and what arose out of the masses of the people in the form of the proletariat. The latter then took hold of the socialist doctrine and thereby, beginning about the year 1875, exerted forcible, radical pressure in the direction of the consciousness soul. Yet even this was in fact not noticed; in any case it was not channeled in any direction, and even today it is basically still evaluated in the most distorted way.

In order to arrive at the anomalies at the bottom of this, we need only call to mind that Oswald Spengler, who wrote the significant book The Decline of the West, also wrote a booklet concerning socialism of which, I believe, 60,000 copies or perhaps more have been printed. Roughly, it is Spengler's view that this European, this Western civilization, is digging its own grave. According to Spengler, by the year 2200, we will be living on the level of barbarism. We have to agree with Spengler concerning certain aspects of his observations; for if the European world maintains the course of development it is pursuing now, then everything will be barbarized by the time the third millennium arrives. In this respect Spengler is absolutely correct. The only thing Spengler does not see and does not want to see is that the shadowy intellect can be raised to Imaginations out of man's inner being and that hence the whole of Western humanity can be elevated to a new civilization.

This enlivening of culture through the intentions of anthroposophical spiritual science is something a person like Oswald Spengler does not see. Rather, he believes that socialism—the real socialism, as he thinks, a socialism that truly brings about social living—has to come into being prior to this decline. The people of the Occident, according to him, have the mission of realizing socialism. But, says Oswald Spengler, the only people called upon to realize socialism are the Prussians. This is why he wrote the booklet Prussianism and Socialism. Any other form of socialism is wrong, according to Spengler. Only the form that revealed its first rosy dawn in the Wilhelminian age, only this form of socialism is to capture the world. Then the world will experience true, proper socialism.

Thus speaks a person today whom I must count among the most brilliant people of our time. The point is not to judge people by the content of what they say but by their mental capacities. This Oswald Spengler, who is master of fifteen different scientific disciplines, is naturally “more intelligent than all the writers, doctors, teachers, and ministers” and so on. We can truly say that with his book about the decline of the West he has presented something that deserves consideration, and that, by the way, is making a most profound impression on the young people in Central Europe. But next to it stands this other idea that I have referred to above, and you see precisely how the most brilliant people can arrive today at the strangest notions. People take hold of the intellect prevalent today and this intellect is shadowy. The shadows flit to and fro, one is caught up in one shadow, then one tries to catch up with another—nothing is alive. After all, in a silhouette, in a woman's shadow image cast on the wall, her beauty is not at all recognizable. So it is also with all other matters when they are viewed as shadow images. The shadow image of Prussianism can certainly be confused with socialism. If a woman turns her back to the wall and her shadow falls on it, even the ugliest woman might be considered beautiful. Likewise, Prussianism can be mistaken for socialism if the shadowlike intellect inwardly pervades the mind of a genius.

This is how we must look at things today. We must not look at the contents, we must aim for the capacities; that is what counts. Thus, it has to be acknowledged that Spengler is a brilliant human being, even though a great number of his ideas have to be considered nonsense. We live in an age when original, elementary judgments and reasons must surface. For it is out of certain elementary depths that one has to arrive at a comprehension of the present age and thus at impulses for the realities of the future.

Naturally, the European East has completely slept through the results of the year 1840. Just think of the handful of intellectuals as opposed to the great masses of the Russian people who, because of the Orthodox religion, particularly the Orthodox ritual, are still deeply immersed in Orientalism. Then think of the somnolent effect of men like Alexander I, Nicholas I, and all the other “I's” who followed them! What has come about today was therefore the element that aimed for this point in which the consciousness soul was to have its impact on European life.

We shall say more tomorrow.

Elfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wir haben im Verlaufe dieser Betrachtungen gesehen, welch wichtiger Punkt in der Menschheitsentwickelung des Abendlandes die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts ist. Wir haben aufmerksam darauf gemacht, wie in dieser Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts gewissermaßen der Höhepunkt materialistischer Gesinnung, materialistischer Lebensansicht vorhanden ist; aber wir haben auch aufmerksam darauf machen müssen, wie das, was sich da im Menschen seit dem Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts herausgerungen hat, eigentlich ein Geistiges ist, so daß man sagen könnte: Das war das Charakteristische in diesem Entwickelungspunkt neuzeitlicher Menschheitsentwickelung, daß der Mensch, indem er am geistigsten geworden ist, diese Geistigkeit nicht erfassen konnte, sondern sich nur erfüllte mit materialistischem Denken, materialistischem Fühlen und auch materialistischem Wollen und Tun. Und die Gegenwart steht ja noch immer unter den Nachwirkungen desjenigen, was sich da, ich möchte sagen, von vielen Menschen unvermerkt vollzogen hat und was ja innerhalb der Menschheitsentwickelung einen Höhepunkt erreicht hat. Wozu war dieser Höhepunkt da? - Er war da, weil ja ein Entscheidendes geschehen sollte in bezug auf das Erringen der Bewußtseinsseelenstufe durch die neuzeitliche Menschheit.

[ 2 ] Fassen wir einmal ins Auge, wie sich die Menschheitsentwickelung abgespielt hat, dann müssen wir sagen: Wir haben, wenn wir beginnen beim dritten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, etwa bis, sagen wit, zum Jahre 747 (siehe Zeichnung) vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha, was wir als die Entwickelung der Empfindungsseele in der Menschheit bezeichnen können. Es beginnt dann das Zeitalter der Verstandes- oder Gemütsseele, die bis zum Jahre 1413 etwa dauert, die ihren Höhepunkt erreicht in demjenigen Zeitpunkt, von dem die äußere Geschichte ja wenig mitteilt, der aber ins Auge gefaßt werden muß, wenn man überhaupt die europäische Entwickelung begreifen will. Es ist ungefähr der Zeitpunkt 333 nach Christus. Seit dem Jahre 1413 haben wir es zu tun mit der Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele, in welcher Entwickelung wir noch darinnenstehen, die eben ein entscheidendes Ereignis erlebte um das Jahr 1850, besser gesagt 1840.

[ 3 ] Es war um dieses Jahr 1840 die Sache so, daß wenn wir die Menschheit als Ganzes auffassen - wie sich die einzelnen Nationen dazumal verhielten, das werden wir nachher gleich zu betrachten beginnen -, wir sagen können, daß, insofern wir auf repräsentative Persönlichkeiten der Nationen hinschauen, sie in diesem Jahre 1840 vor dem Punkte standen, wo der Verstand schon am meisten zum Schattenwesen geworden war. Der Verstand hatte seinen Schattencharakter angenommen. Ich habe Ihnen ja gestern diesen Schattencharakter des Verstandes zu charakterisieren versucht. So weit war die Menschheit der zivilisierten Erde gediehen, daß von da ab die Möglichkeit bestand, aus der allgemeinen Kultur heraus ohne Einweihung die Empfindung zu bekommen: Wir haben den Verstand, der Verstand hat sich heraufentwickelt, aber dieser Verstand hat für sich selber keinen Inhalt mehr. Wir haben Begriffe, aber diese Begriffe sind leer, wir müssen sie mit etwas erfüllen. — Das ist der Ruf, der sozusagen durch die Menschheit, allerdings noch dunkel und unvernehmlich, geht. Aber in den tiefen, untergründigen, unterbewußten Sehnsuchten der Menschen lebt der Ruf, eine Erfüllung zu bekommen für das Schattenhafte des Verstandesdenkens. Es ist eben der Ruf, der nach Geisteswissenschaft geht. Wir können aber diesen Ruf auch konkret fassen.

[ 4 ] Es war einfach in dieser Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts die menschliche Organisation, in deren physischem Teil ja dieser schattenhafte Verstand geübt wird, so weit, daß sie den Verstand, den leeren schattenhaften Verstand gut ausbilden konnte. Nun gehörte in diesen schattenhaften Verstand etwas hinein, er mußte mit etwas erfüllt werden. Erfüllt werden kann er nur, wenn der Mensch sich bewußt wird: Ich muß etwas aufnehmen von dem, was sich mir auf der Erde selbst nicht darbietet, was auf der Erde selber nicht lebt, was ich nicht erfahren kann in dem Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Ich muß wirklich in diesen Verstand herein etwas aufnehmen, was zwar ausgelöscht wurde, als ich aus geistigen Seelenwelten mit den Ergebnissen meiner früheren Erdenleben in eine physische Körperlichkeit herunterstieg, etwas, was zwar verdunkelt worden ist, was aber ruht in den Tiefen meiner Seele. Ich muß es von da heraufbringen, ich muß mich auf etwas besinnen, was in mir ist einfach dadurch, daß ich ein Mensch des 19. Jahrhunderts bin.

[ 5 ] Es war vorher nicht so, daß die Menschen in derselben Weise hätten Selbstbesinnung üben können. Daher mußten sie erst ihre Menschheit so weit bringen, daß der physische Leib eben sich immer reifer und reifer machte, um den schattenhaften Verstand vollständig auszubilden, vollständig zu üben. Jetzt waren die physischen Leiber, wenigstens bei den vorgerücktesten Menschen, so weit, daß man hätte sagen können, besser gesagt, man kann es seither: Ich will mich darauf besinnen, was suche ich aus den Untergründen meines Seelenlebens heraufzubringen, um in diesen schattenhaften Verstand etwas hineinzugießen? - Dadurch wäre dann dieser schattenhafte Verstand von etwas durchgossen worden, und dadurch hätte aufgedämmert die Bewußtseinsseele. Es war also gewissermaßen in diesem Zeitpunkt die Gelegenheit dazu gegeben, daß die Bewußtseinsseele hätte aufdämmern können.

[ 6 ] Nun werden Sie sagen: Ja, aber schon die ganze Zeit vorher, seit dem Jahre 1413, war ja das Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele. — Gewiß, aber es ist eben eine vorbereitende Entwickelung zunächst gewesen, und Sie brauchen nur zu bedenken, welche Grundbedingungen zu einer solchen Vorbereitung gerade in diesem Zeitalter gegenüber allen früheren Zeitaltern vorhanden waren. In dieses Zeitalter fällt ja zum Beispiel die Entdeckung der Buchdruckerkunst, die Ausbreitung der Schrift. Die Menschen nehmen seit dem 15. Jahrhundert dutch die Buchdruckerkunst und durch die Schrift nach und nach eine ganze Menge von geistigem Inhalt auf. Aber sie nehmen ihn eben äußerlich auf; und das Wesentliche dieses Zeitalters ist ja, daß eine ungeheure Summe von geistigem Inhalt äußerlich aufgenommen worden ist. Die Völker der zivilisierten Erde haben ja äußerlich etwas aufgenommen, was sie früher eigentlich in ihren großen Massen nur durch die hörbare Sprache haben aufnehmen können. Im Zeitalter der Verstandesentwickelung war es so, und im Zeitalter der Empfindungsseele war es erst recht so, daß im Grunde genommen alle Verbreitung der Bildung auf dem mündlichen Sprechen beruht hat. Durch die Sprache klingt noch etwas durch von GeistigSeelischem. In den Worten lebte besonders in früheren Zeiten durchaus das, was man nennen kann den «Genius der Sprache». Das hörte auf, als in abstrakter Form, durch Schrift und Druck, der Inhalt der menschlichen Bildung aufgenommen wurde. Das Gedruckte und Geschriebene hat ja die Eigentümlichkeit, daß es in einer gewissen Weise das auslöscht, was der Mensch durch die Geburt mitbekommt aus seinem überirdischen Dasein.

[ 7 ] Selbstverständlich soll das nicht heißen, daß Sie nun aufhören sollen zu lesen oder zu schreiben, sondern es soll heißen, daß eine stärkere Kraft heute notwendig ist, um das, was in der menschlichen Wesenheit unten liegt, heraufzuheben. Aber diese stärkere Kraft muß auch notwendig erlangt werden. Wir müssen auf Selbstbesinnung kommen, trotzdem wir lesen und schreiben, wir müssen eben diese stärkere Kraft entwickeln gegenüber der früheren. Das ist die Aufgabe im Zeitalter der Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele.

[ 8 ] Bevor wir uns nun ein wenig ansehen können, wie ja nun in einer gewissen Weise doch begonnen hat das Herunterwirken der geistigen Welt in die physisch-sinnliche Welt herein, wollen wir uns einmal heute die Frage vorlegen: Wie haben denn eigentlich die Nationen der neueren Zivilisation diesen Zeitpunkt von 1840 angetroffen?

[ 9 ] Wir wissen aus früheren Vorträgen, daß das charakteristische Volk für die Ausbildung der Bewußtseinsseele, also für dasjenige, worauf es gerade in diesem Zeitalter ankommt, das angelsächsische Volk ist. Dieses angelsächsische Volk ist das Volk, das durch seine ganze Organisation daraufhin angelegt ist, die Bewußtseinsseele besonders auszubilden. Darauf beruht ja die besondere Stellung des angelsächsischen Volkes, des anglo-amerikanischen Volkes in unserem Zeitalter, daß es für die Ausbildung der Bewußtseinsseele besonders veranlagt ist. Aber jetzt fragen wir uns einmal rein äußerlich: Wie ist denn eigentlich dieses angelsächsische Volk angekommen an diesem Zeitpunkte, der der wichtigste ist in der modernen Kulturentwickelung?

[ 10 ] Man kann sagen: Gerade das angelsächsische Volk hat lange Zeit fortgelebt in einem Zustande, den man vielleicht am besten dadurch bezeichnen kann - selbstverständlich mit den entsprechenden Varianten und Metamorphosen -, daß man sagt: Es haben sich in bezug auf die innere Seelenverfassung innerhalb des angelsächsischen Volkes bis ins 19. Jahrhundert herein diejenigen inneren Impulse erhalten, welche im Griechentum schon anderen Formen gewichen sind. — Man könnte sagen, im 11. und 10. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert ist das Eigentümliche, daß da die Nationen das, was durchgemacht wird, in verschiedenen Zeiten durchmachen, daß sich gewissermaßen die Zeiten übereinanderschieben. Nur bemerkt man solche Dinge außerordentlich schwer aus dem Grunde, weil ja natürlich im 19. Jahrhundert schon alles mögliche da war - Schreiben, Lesen -, weil andere Daseinsbedingungen da waren in Schottland und in England, als sie vorhanden waren in der Homerischen Zeit.

[ 11 ] Aber dennoch, wenn man die Seelenverfassung des Volkes eben als Nation ins Auge faßt, so ist das so, daß geblieben ist diese Seelenverfassung der Homerischen Zeit, die in Griechenland im tragischen Zeitalter überwunden worden ist, die in den Sophoklismus übergegangen ist. Diese Zeit hat sich in der angelsächsischen Welt erhalten bis ins 19. Jahrhundert herein, eine Art patriarchalischer Lebensauffassung, eine Art patriarchalischen Lebens. Insbesondere hat sich ausgebreitet dieses patriarchalische Leben von der Seelenverfassung in Schottland herein, und es ist aus diesem Grunde, warum gerade auf das angelsächsische Volk nicht etwa dasjenige gewirkt hat, was von den Einweihungsstätten Irlands ausgegangen ist. Das hat ja, wie wir bei anderen Gelegenheiten gehört haben, hauptsächlich im kontinentalen Europa gewirkt. Auf der britischen Insel selber hat hauptsächlich dasjenige gewirkt, was vom Norden, von Schottland herunter auch an Einweihungswahrheiten gekommen ist, und diese Einweihungswahrheiten haben dann das andere durchdrungen. Aber es ist etwas in der ganzen Auffassung der menschlichen Persönlichkeit, das gewissermaßen uralt geblieben ist. Und das wirkt noch nach, das wirkt nach selbst in der Artund Weise, wie, sagen wir, das Verhältnis von Whigs und Tories in dem englischen Parlamente sich entfaltete. Es ist ja so, daß wir es ursprünglich nicht etwa zu tun haben mit dem Gegensatz von liberal und konservativ, sondern wir haben es zu tun mit zwei Schattierungen in politischen Ansichten, für die man heute eigentlich gar keine Empfindungen mehr hat.

[ 12 ] Die Whigs sind ja im wesentlichen eigentlich die Fortpflanzung desjenigen, was man nennen könnte, eine von allgemeiner Menschenliebe getragene, in Schottland aufgegangene Menschheitsströmung. Die Tories sind ursprünglich katholisierende, der Sage nach, die aber einen gewissen historischen Hintergrund hat, sogar katholisierende Pferdediebe aus Irland gewesen. Dieser Gegensatz, der sich dann ausdrückt in dem besonderen politischen Wollen, der spiegelt ein gewisses patriarchalisches Sein; und dieses patriarchalische Sein, das hat gewisse elementare Kräfte fortbehalten. Man kann das sehen aus der Art und Weise, wie die Besitzer größerer Ländereien zu denjenigen Menschen gestanden haben, die als Untertanen auf diesen Ländereien gesessen haben. Bis ins 19. Jahr- . hundert geht ja dieses Untertanenverhältnis; bis ins 19. Jahrhundert war es ja so, daß im Grunde genommen niemand ins Parlament gewählt wurde, der nicht durch ein solches grundbesitzerliches Verhältnis eine gewisse Macht hatte. Man muß nur bedenken, was das bedeutet. Solche Dinge wiegt man nicht in der richtigen Weise. Man muß nur bedenken, was es bedeutet, daß zum Beispiel erst im Jahre 1820 im englischen Parlament das Gesetz abgeschafft wurde, wonach man einen Menschen, der eine Uhr gestohlen oder der gewildert hat, mit dem Tode bestrafte. Bis dahin war es durchaus gesetzliche Bestimmung, daß jemand, der eine Taschenuhr gestohlen hatte oder der Wilddieb war, mit dem Tode bestraft wurde. Das zeigt ja durchaus, wie geblieben waren gewisse alte elementare Zustände. Heute sieht der Mensch das, was in seiner unmittelbaren Gegenwart lebt, und er verlängert sozusagen die wesentlichsten Grundbestandteile der Zivilisation der Gegenwart nach rückwärts und sieht nicht, wie kurz eigentlich die Zeit ist, in der für die wichtigsten europäischen Gegenden diese Dinge sich aus ganz elementaren Zuständen erst herausgebildet haben.

[ 13 ] So können wir sagen, daß sich da diese patriarchalischen Zustände als der Grund und Boden desjenigen erhalten haben, in was dann einschlug das Allerallermodernste, das nicht zu denken ist in der sozialen Struktur ohne die Entwickelung der Bewußtseinsseele. Bedenken Sie nur schon im 18. Jahrhundert den ganzen Umschwung, der in der sozialen Struktur eingetreten war durch die technische Metamorphose in bezug auf die Textilindustrie und so weiter. Bedenken Sie, wie da das maschinelle Element, das technische Element hineingezogen ist in dieses Patriarchalische, und bilden Sie sich eine anschauliche Vorstellung, wie auf dem Grunde des Patriarchalischen, dieses gutsherrlichen Verhältnisses zu den Untertanen, sich da hineinschiebt die Entstehung des modernen Proletariats durch die Umgestaltung der Textilindustrie. Denken Sie sich, was da für ein Chaos sich durcheinanderschiebt, wie sich die Städte herausbilden aus den alten Landschaften, wie das Patriarchalische, ich möchte sagen, mit einem kühnen Sprung hineinspringt in das moderne sozialistische, proletarische Leben.

[ 14 ] Man kann geradezu, wenn man es graphisch darstellen will, sagen, es entwickelt sich dieses Leben in der Form, wie es in Griechenland bis etwa um das Jahr 1000 vor Christus war (siehe Zeichnung). Dann macht es einen kühnen Sprung, und wir stehen plötzlich im Jahr 1820. Innerlich ist das Leben im Jahre 1000 vor Christus stehengeblieben; aber äußerlich sind wir im 18. Jahrhundert, sagen wit 1770 (Pfeile). Da wälzt sich hinein alles dasjenige, was dann im modernen Leben, ja in der Jetztzeit dasteht. Aber den Anschluß, die Notwendigkeit findet dieses englische Leben erst 1820 (siehe Zeichnung); da sind ja solche Dinge überhaupt erst spruchreif geworden, wie die Abschaffung der Todesstrafe für einen kleinlichen Diebstahl und dergleichen. So kann man sagen: Es ist durchaus hier zusammengeflossen ein Uraltes mit dem Allerallermodernsten; und so trifft dann die Weiterentwickelung hinein in das Jahr 1840.

[ 15 ] Was hatte nun in diesem Zeitalter hier, in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, gerade bei dem anglo-amerikanischen Volke zu geschehen? Wir müssen bedenken, daß erst nach dem Jahre 1820, sogar erst nach 1830 Gesetze notwendig geworden sind in England, wodurch Kinder unter zwölf Jahren nicht zu längerer Fabrikarbeit angehalten werden durften als zu achtstündiger, Kinder von dreizehn bis zu achtzehn Jahren höchstens zu zwölfstündiger Tagesarbeit. Bitte, vergleichen Sie das mit den heutigen Verhältnissen! Bedenken Sie, was heute als Achtstundentag von der breiten Masse des Proletariats gefordert wird! Im Jahre 1820 noch wurden in England Knaben länger als acht Stunden beschäftigt in Bergwerken und Fabriken, und erst in diesem Jahre wurde für diese der Achtstundentag angesetzt; aber für Kinder vom zwölften bis achtzehnten Lebensjahre herrschte noch der Zwölfstundentag.

[ 16 ] Man muß diese Dinge durchaus ins Auge fassen, wenn man sehen will, was da eigentlich zusammengestoßen ist, und im Grunde genommen könnte man sagen, erst im zweiten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts wandte sich England heraus aus dem Patriarchalischen und sah sich genötigt, zu rechnen mit dem, was sich langsam durch die Maschinentechnik hineingeschoben hat in dieses Alte. So traf dasjenige Volk, welches vorzugsweise berufen ist, die Bewußtseinsseele sozusagen auszubilden, so traf dieses Volk der Zeitpunkt von 1840.

[ 17 ] Nehmen Sie jetzt andere Völker der modernen Zivilisation; nehmen Sie dasjenige, was vom lateinisch-romanischen Elemente geblieben ist, was also das Romanisch-Lateinische vom vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum herübergetragen hat, was gewissermaßen als Erbgut herübergebracht hat die alte Verstandesseelenkultur im Zeitalter der Bewußtseinsseele. Seine Kulmination, seinen Höhepunkt hat ja das, was da noch vorhanden war an Leben der Verstandesseele, in der Französischen Revolution am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts gefunden. Wir sehen, wie da plötzlich in äußerster Abstraktion auftauchen die Ideale von «Freiheit», «Gleichheit», «Brüderlichkeit». Wir sehen, wie sie ergriffen werden von solchen Skeptikern wie Voltaire, von solchen Enthusiasten wie Rousseau, wir sehen, wie sie überhaupt auftauchen aus der breiten Masse des Volkes; wir sehen, wie die Abstraktion, die vollberechtigt ist auf diesem Gebiete, hier eingreift in das Gefüge der sozialen Struktur - eine ganz andere Entwickelung als drüben in England. In England die Überreste des altgermanischen patriatchalischen Lebens, durchsetzt von dem, was die moderne Technik, was das moderne materialistische wissenschaftliche Leben in die soziale Struktur hineinsenden konnte, in Frankreich alles Überlieferung, alles Tradition. Man möchte sagen: Mit demselben Duktus, mit dem einstmals ein Brutus oder Cäsar in Rom in den verschiedensten Schattierungen gewirkt haben, mit demselben Duktus wird jetzt die Französische Revolution in Szene gesetzt. So taucht wiederum auf in abstrakten Formen das, was Freiheit, Gleichheit und Brüderlichkeit ist. Und nicht von außen herein wird da zersprengt, wie in England, dasjenige, was als altes patriarchalisches Element vorhanden ist, sondern das romanisch-juristische Festsetzen, das Festhalten an dem alten Eigentumsbegriff, an den Grundbesitzerverhältnissen und so weiter, an den Erbschaftsverhältnissen namentlich, das, was römisch-juristisch festgesetzt ist, wird von der Abstraktion her zersetzt, wird von der Abstraktion her auseinandergetrieben.

[ 18 ] Man braucht nur zu denken, welchen ungeheuren Einschnitt in das ganze europäische Leben die Französische Revolution brachte. Man braucht ja nur daran zu erinnern, daß vor der Französischen Revolution diejenigen, die, ich möchte sagen, herausgesondert waren aus der Masse des Volkes, auch Rechtsvorteile hatten. Nur gewisse Leute konnten, sagen wir, zu gewissen Staatsstellungen kommen. Da Breschen hineinzuschlagen, das zu durchlöchern, das war dasjenige, was aus der Abstraktion heraus, aus dem schattenhaften Verstande heraus die Französische Revolution forderte. Aber sie trug eben durchaus in sich das Gepräge des schattenhaften Verstandes, der Abstraktion, und es blieb im Grunde genommen das, was da gefordert wurde, eine Art Ideologie. Daher, könnte man sagen, schlägt dasjenige, was schattenhafter Verstand ist, sogleich um in sein Gegenteil.

[ 19 ] Wir sehen dann den Napoleonismus und wir sehen das staatlich-soziale Experimentieren im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts. Die erste Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts ist ja in Frankreich ein Experimentieren ohne Ziel. Wie sind die Ereignisse, durch welche so ein Louis-Philippe zum Beispiel König von Frankreich wird und dergleichen, wie wird da experimentiert? — Es wird so experimentiert, daß man sieht, der schattenhafte Verstand vermag nicht wirklich in die realen Verhältnisse einzugreifen. Es bleibt alles ungetan im Grunde genommen, es bleibt alles unvollendet, es bleibt alles Erbschaft des alten Romanismus. Man könnte sagen: Heute ist noch immer nicht das Verhältnis, das die Französische Revolution im Abstrakten ganz klar hatte, das Verhältnis, sagen wir zur katholischen Kirche, in der äußeren konkreten Wirklichkeit in Frankreich geklärt. Und wie unklar war es von Zeit zu Zeit immer wiederum im Laufe des 19. Jahrhunderts. Der abstrakte Verstand hatte sich zu einer gewissen Höhe heraufgerungen in der Revolution, und dann ein Experimentieren, ein Nicht-Gewachsensein den äußeren Verhältnissen. Und so traf diese Nation das Jahr 1840.

[ 20 ] Wir könnten auch andere Nationen in Betracht ziehen. Sehen wit zum Beispiel Italien an, das noch, ich möchte sagen, ein Stück Empfindungsseele mitbehielt beim Durchgang durch die Verstandeskultur, das dieses Stück Empfindungsseele in die neuere Zeit heraufbrachte, und es daher nicht bis zu den abstrakten Begriffen von Freiheit, Gleichheit und Brüderlichkeit brachte, bis zu denen man es in der Französischen Revolution gebracht hatte, das aber doch den Übergang suchte von einem gewissen alten Gruppenbewußtsein der Menschen zu dem individuellen Menschheitsbewußtsein. Italien traf das Jahr 1840 so, daß man sagen kann: Was sich da in Italien heraufarbeiten will an individuellem Menschheitsbewußtsein, wird eigentlich immerfort niedergehalten von demjenigen, was.nun im übrigen Europa ist. Wir sehen ja, wie die Habsburgische Tyrannei in einer furchtbaren Weise lastet gerade auf dem, was sich in Italien an individuellem Menschheitsbewußtsein heraufarbeiten will. Wir sehen ja jenen merkwürdigen Kongreß von Verona, der in den zwanziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts eigentlich ausmachen wollte, wie man sich auflehnen kann gegen den ganzen Sinn der modernen Zivilisation. Wir sehen, wie da von Rußland, Österreich ausging, ich möchte sagen eine Art von Verschwörung gegen dasjenige, was das moderne Menschheitsbewußtsein bringen sollte. Es ist kaum etwas so interessant, wie dieser Veroneser Kongreß, der im Grunde genommen die Frage beantworten wollte: Wie schlägt man alles das tot, was sich als modernes Menschheitsbewußtsein heraufentwickeln will?

[ 21 ] Und dann sehen wir, wie nun die Menschheit im übrigen Europa ringt, so ringt, daß in Mitteleuropa ja überhaupt nur immer ein kleiner Teil der Menschheit sich heraufringen kann zu einem gewissen Bewußtsein, sozusagen in einer gewissen Weise erlebt, daß jetzt das Ich eintreten soll in die Bewußtseinsseele. Wir sehen, wie das in einer gewissen geistigen Höhe erreicht werden soll. Wir sehen es in jener merkwürdigen Kulturhöhe des Goetheschen Zeitalters, in der ein Fichte gewirkt hat, wir sehen, wie sich da das Ich vordrücken will zur Bewußtseinsseele herein. Aber wir sehen, wie die ganze GoetheKultur etwas bleibt, was im Grunde genommen nur bei ganz wenigen lebt. Ich glaube, die Menschen studieren allzuwenig, was selbst noch in der jüngsten Vergangenheit war. Die Menschen denken zum Beispiel einfach: Goethe hat gelebt von 1749 bis 1832; er hat den «Faust» und alles Mögliche geschrieben. - Das ist das, was man weiß von Goethe, und das war seither da.

[ 22 ] Bis zum Jahre 1862, also dreißig Jahre nach Goethes Tode, war ja überhaupt für die wenigsten Menschen ein Exemplar von Goethe zu beschaffen. Goethe war nicht frei; nur ganz wenige Menschen besaßen irgendwie ein Exemplar von Goethes Schriften. Es war also dasjenige, was Goetheanismus ist, etwas, was ganz wenigen eigen geworden war. Erst in den sechziger Jahren konnte eine größere Anzahl von Menschen überhaupt Kunde erlangen von dem, was in Goethe lebte, und da war im Grunde genommen schon das Verständnis, die Verständnisfähigkeit wiederum hinuntergeschwunden. Es ist zu einem richtigen Verständnis Goethes im Grunde genommen gar nicht gekommen. Und das letzte Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts war überhaupt gar nicht geeignet, ein rechtes Verständnis für Goethe hervorzurufen.

[ 23 ] Ich habe es ja öfters erwähnt, wie Herman Grimm in den siebziger Jahren zunächst seine «Vorlesungen über Goethe» an der Berliner Universität gehalten hat. Das war ein Ereignis, und das Buch, das vorhanden ist als der «Goethe» Herman Grimms, ist eine bedeutende Erscheinung innerhalb der mitteleuropäischen Literatur. Aber wenn man jetzt dieses Buch nimmt, was bedeutet es denn? Ja, alle Gestalten, die mit Goethe im Zusammenhange lebten, kommen darinnen vor, aber sie haben immer nur Ausdehnungen nach zwei Dimensionen; sie sind Schattenfiguren. Alles das, was da Porträts sind, sind Schattenfiguren. Goethe selber ist bei Herman Grimm eine zweidimensionale Wesenheit. Es ist gar nicht der Goethe selber. Ich will gar nicht sprechen von dem Goethe, den man in Weimar in den Nachmittags-Kaffeekränzchen den «dicken Geheimrat mit dem Doppelkinn» nannte; von dem will ich gar nicht sprechen; aber er hat überhaupt keine «Dicke» in Herman Grimms «Goethe», sondern er ist dort ein zweidimensionales Wesen, er ist der Schatten, der an eine Wand hingeworfen ist. Und ebenso all die anderen, die da auftreten; Herder, ein Schatten, der an eine Wand hingemalt ist. Etwas mehr Greifbarkeit tritt uns gerade bei Herman Grimm bei denjenigen Persönlichkeiten entgegen, die aus dem Volke heraufsteigen zu Goethe, wie Friederike von Sesenheim, die so wunderschön da geschildert ist, oder wie die Frankfurterin Lili Schönemann, also gerade dasjenige, was heraufsteigt nun nicht aus der Atmosphäre, in der Goethe eigentlich geistig lebte. Das ist mit einer gewissen «Dicke» geschildert. Aber so ein Jacobi, so eine Gestalt wie Lavater - alles Schattenbilder an der Wand. Man kommt nicht in das eigentliche Wesen der Sachen hinein, man sieht, ich möchte sagen, handgreiflich, wie die Abstraktion wirkt. Die Abstraktion kann ja auch durchaus anmutig sein, was das Herman Grimmsche Buch durchaus ist; aber schattenhaft ist das Ganze. Es sind Silhouetten, zweidimensionale Wesenheiten, die uns da entgegentreten.

[ 24 ] Und das konnte auch nicht anders sein. Denn es ist wirklich so: Deutscher durfte man sich ja in Deutschland überhaupt nicht nennen in der Zeit, in der zum Beispiel Herman Grimm noch jung war. Die Art und Weise, wie man von Deutschen gesprochen hat in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts, die wird ja insbesondere in der Gegenwart mißverstanden. Wie «gruselt» es die Leute des Westens, die Ententeleute, wenn sie heute anfangen Fichtes «Reden an die deutsche Nation» zu lesen und da finden: «Ich spreche zu Deutschen schlechtweg, von Deutschen schlechtweg.» Geradeso wird das unschuldige Lied «Deutschland, Deutschland über alles», töricht interpretiert, indem ja dieses Lied nichts anderes heißen soll als, man will Deutscher sein, nicht Schwabe, nicht Bayer, nicht Österreicher, nicht Franke, nicht Thüringer. Wie dieses Lied sich nur auf die Deutschen stellt allseitig, so wollte Fichte nur sprechen «zu Deutschen schlechtweg», nicht zu Österreichern, zu Bayern, zu Badensern, zu Württembergern oder zu Franken, oder zu Preußen gar; er wollte «zu Deutschen» sprechen. Das versteht man natürlich zum Beispiel in einem Lande nicht, wo es längst selbstverständlich geworden ist, daß man sich einen Franzosen nennen kann. In Deutschland wurde man in gewissen Zeiten eingesperrt, wenn man sich einen Deutschen nannte. Man konnte sich einen Österreicher, einen Schwaben, einen Bayer nennen; aber Deutscher sich zu nennen, war hochverräterisch. Wer in Bayern sich einen Deutschen nannte, der bekundete damit, daß er nicht nur hinaufschauen wollte zum bayerischen Throne, der seine Grenze da und dort hat, sondern daß er hinausschauen wollte über die Grenze von Bayern hinaus. Das war aber Hochverrat! Man durfte sich nicht einen Deutschen nennen. Daß diese Dinge, die von Deutschen und über Deutschland gesagt worden sind, eben Bezug haben auf dieses Zusammendrängen desjenigen, was deutsch ist, das wird heute gar nicht verstanden, und man stellt das törichte Zeug hin, als wenn so etwas wie das Hoffmannsche Lied sich darauf beziehen würde, daß Deutschland herrschen soll über alle Nationen der Welt; während es nichts anderes heißen soll als: nicht Schwaben, nicht Österreich, nicht Baden über alles in der Welt, sondern Deutschland über alles in der Welt, gerade wie der Franzose sagt: Frankreich über alles in der Welt. Aber gerade da in Mitteleuropa war dieses Eigentümliche, daß man im Grunde genommen eine Stammeskultur hatte. Sie können ja heute noch diese Stammeskultur in Deutschland überall sehen. Der Württemberger ist verschieden vom Franken, er ist verschieden bis in die Begriffs- und Wortformen, bis in die Gedankenformen hinein, die sich in der Literatur ausbreiten. Es ist ja auch durchaus, sagen wir, ein grandioser Unterschied, wenn Sie einen Franken nehmen, wie zum Beispiel den klotzigen Michael Conrad - wenn ich die neuere Literatur hernehme -, und ihn vergleichen mit irgend etwas, was etwa von einem Württemberger, also im Nachbarlande, in derselben Zeit geschrieben worden ist. Bis in die ganze Konfiguration der Gedanken spielt ja das bis in die neueste Zeit hinein. Aber all das, was sich da ausbreitet, was da in den Stammeseigentümlichkeiten lebt, das bleibt ja unberührt von dem, was nun eigentlich erreicht wird von den repräsentativen Trägern der Nationen. Man hat doch, sagen wir, in dem Gebiete, das man Deutschland nennt, so etwas erreicht, wie den Goetheanismus mit alledem, was dazugehört. Aber das ist ja nur von wenigen intellektuellen Menschen erreicht worden, davon ist die große Masse der Menschheit gar nicht berührt. Die große Masse der Menschheit bleibt ungefähr auf dem Standpunkte, der eigenommen worden ist in Mitteleuropa etwa um das Jahr 300 oder 400 nach Christus. Geradeso wie man im angelsächsischen Volke stehengeblieben ist bei dem Jahre 1000 vor Christus, so bleibt man in Mitteleuropa stehen bei dem Jahre 400 nach Christus. Das bitte ich nicht so zu nehmen, daß jetzt wiederum ein furchtbarer Hochmut aufkommen könnte, indem man sagt: Die Angelsachsen, die sind im homerischen Zeitalter zurückgeblieben, und wir waren schon im Jahre 400 nach Christus! - So sind die Dinge nicht zu bewerten, sondern es wird eben nur auf gewisse Eigentümlichkeiten hingewiesen.

[ 25 ] Nun ergeben aber wiederum die geographischen Verhältnisse, daß dieser Stand der allgemeinen Seelenbildung in Deutschland viel länger dauert als in England drüben. England hat in sein altes patriarchalisches Leben schnell hineinfließen lassen müssen dasjenige, was zunächst bei ihm auf dem Gebiete der Textilindustrie, aber später auch auf dem Gebiete anderer Techniken aus dem modernen materialistisch-wissenschaftlich-technischen Leben die soziale Struktur gestaltet hat. Was deutsches Gebiet war, und was überhaupt Mitteleuropa war, das hat sich dem zunächst entgegengestellt, das hat die alten Eigentümlichkeiten viel länger behalten, bis, ich möchte sagen, zu einem Zeitpunkte, wo schon über die ganze Welt in voller Geltung war, was durch die moderne Technik gekommen ist. England hat noch den Anschluß gefunden mit der Umgestaltung der sozialen Struktur bis zu einem gewissen Grade in der ersten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Das alles, was da errungen worden ist, das ging durchaus vorüber an Mitteleuropa.

[ 26 ] Mitteleuropa nahm zwar etwas von abstrakten Revolutionsideen auf. Das kam in den vierziger Jahren, in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts, dann in verschiedenen Wogen und Wellen zum Durchbruch; aber es wartete gewissermaßen ab, bis die Technik die ganze Welt erfüllte, und dann trug sich ja das Eigentümliche zu, daß solch ein Mensch - wir könnnten auch andere Repräsentanten nehmen -, der in Deutschland denken gelernt hat vom Hegelismus, wie Karl Marx , dann hinübergegangen ist nach England und dort sich das soziale Leben angeschaut und daraus die sozialistischen Doktrinen gebildet hat. Für diese sozialen Doktrinen war dann am Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts Mitteleuropa reif. Diese sozialen Doktrinen wurden dann von Mitteleuropa angenommen, so daß also, wenn man in einer etwa ähnlichen Weise nun aufzeichnen wollte, was sich in Mitteleuropa entwickelt hat, man sagen müßte: Es ging die Entwickelung elementarer fort, wenn auch durch Schrift und Druck Mannigfaltiges von außen aufgenommen worden ist. Es ging dasjenige, was wie vierhundert Jahre nach Christus war, weiter, machte dann einen Sprung und fand erst im Grunde genommen im letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts den Anschluß, etwa im Jahre 1875. So daß, während das Jahr 1840 von der angelsächsischen Nation schon mit einer Umwandlung der Verhältnisse angetroffen wird, schon mit der Notwendigkeit, die Bewußtseinsseele aufzunehmen, das deutsche Volk fortträumte, und im Traume erlebte es noch das Jahr 1840 und verschlief dann die Zeit, die da gewesen wäre, um eine Brücke zu bauen zwischen den führenden Persönlichkeiten und dem, was aus der Masse des Volkes als Proletariat aufstieg und was sich dann der sozialistischen Doktrin bemächtigte und eben dadurch einen gewaltsamen, radikalen Zwangsdruck ausübte hin zu der Bewußtseinsseele, etwa von 1875 an. Aber auch dies ist eigentlich nicht bemerkt worden, jedenfalls nicht in irgendwelche Kanäle gebracht worden, und wird ja im Grunde genommen heute noch immer in der schiefsten Weise beurteilt.

[ 27 ] Um aufall die Anomalien zu kommen, welche da zugrundeliegen, braucht man ja nur daran zu erinnern, daß Oswald Spengler, der das bedeutende Buch geschrieben hat über den «Untergang des Abendlandes», ja auch ein Büchelchen, das, wie ich glaube, schon in 60 000 Exemplaren verbreitet ist, oder vielleicht in noch mehr, geschrieben hat über den Sozialismus. Spengler hat ja ungefähr die Anschauung, daß diese europäische, diese abendländische Zivilisation überhaupt sich ihr Grab gräbt. Wenn das Jahr 2200 geschrieben sein wird, so wird man nach Spengler auf dem Boden der Barbarei leben. Man muß Spengler Recht geben in bezug auf gewisse Seiten seiner Ausführungen; denn wenn die europäische Welt dabei bleibt, sich so weiter entwickeln zu wollen, wie sie es jetzt tut, so wird, wenn das dritte Jahrtausend beginnt, alles barbarisiert sein. In dieser Beziehung hat Spengler vollständig recht; nur sieht Spengler nicht und will nicht sehen, wie aus dem Inneren des Menschen der schattenhafte Verstand zu Imaginationen und damit die ganze Menschheit des Abendlandes zu einer neuen Kultur erhoben werden kann. Diese Belebung der Kultur durch das, was anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft will, das sieht nämlich ein Mensch wie Oswald Spengler nicht. Aber er hat den Gedanken, der Sozialismus — der richtige Sozialismus, wie er meint, dieser Sozialismus, der wirklich ein soziales Leben herbeiführt -, der müsse noch vor diesem Untergange entstehen; es habe noch die Menschheit des Abendlandes die Mission, den Sozialismus zu verwirklichen. Aber, sagt Oswald Spengler, die einzigen Menschen, die berufen sind, den Sozialismus zu verwirklichen, das sind die Preußen. Daher hat er das Büchelchen geschrieben «Preußentum und Sozialismus». Jeder andere Sozialismus ist nach Spengler falsch, lediglich derjenige, der im Wilhelminischen Zeitalter seine ersten rosigen Strahlen gezeitigt hat, lediglich dieser Sozialismus müsse die Welt erobern; dann werde die Welt den wahren, den richtigen Sozialismus erleben. So spricht heute ein Mensch, den ich zu den genialsten Menschen der Gegenwart zu zählen habe. Es kommt nicht darauf an, die Menschen zu beurteilen nach dem Inhalte dessen, was sie sagen, sondern es kommt darauf an, die Menschen nach ihrer geistigen Kapazität zu beurteilen. Dieser Oswald Spengler, der fünfzehn Wissenschaften beherrscht, ist natürlich «gescheiter als alle die Schreiber, Doktoren, Magister und Pfaffen» und so weiter, und man kann schon sagen, er hat mit seinem Buch über den Untergang des Abendlandes etwas hingestellt, was Berücksichtigung verdient, was ja übrigens auch namentlich in der Jugend Mitteleuropas einen ungeheuer tiefen Eindruck macht. Aber daneben steht die Idee, die ich nunmehr jetzt ausgeführt habe, und Sie sehen, wie heute gerade genialische Menschen zu den ausgefallensten Ideen kommen können. Man ergreift Verstand, der heute wirkt, und der ist schattenhaft. Die Schatten huschen hin, man ist in einem Schatten drinnen, dann huscht man den anderen nach, nichts lebt. Es ist ja auch in der Silhouette, in dem Schattenbild einer Frau, das auf die Wand geworfen wird, ihre Schönheit gar nicht zu erkennen, und so ist es, wenn die Sachen in Schattenbildern betrachtet werden, auch. Das Preußentum im Schattenbilde ist durchaus zu verwechseln mit dem Sozialismus. Wenn eine Frau der Wand den Rücken zuwendet und ihr Schatten auf die Wand fällt, dann kann man die Häßlichste für schön halten; in gleicher Art kann man auch das Preußentum für den Sozialismus halten, wenn der schattenhafte Verstand dasjenige, was die Genialität ist, innerlich durchsetzt.

[ 28 ] So muß man heute diese Dinge ansehen. Man darf heute nicht auf die Inhalte gehen, sondern man muß auf die Kapazitäten gehen, das ist das Wichtige. Und so muß man anerkennen, daß so ein Mensch wie Spengler ein genialer Mensch ist, wenn man auch eine große Anzahl seiner Ideen für eine Narretei halten muß. Wir leben in einem Zeitalter, wo ursprüngliche, elementare Urteilsbegründungen auftreten müssen; denn aus gewissen elementaren Untergründen heraus muß zu einem Verständnis der Gegenwart und damit zu Impulsen für Wirklichkeiten für die Zukunft gekommen werden.

[ 29 ] Vollkommen verschlafen natürlich hat der Osten dasjenige, was sich im Jahre 1840 ergeben hat. Denken Sie doch nur an die Handvoll Intellektueller in der großen Masse der durch die orthodoxe Religion, namentlich durch den orthodoxen Kultus noch tief im Orientalismus steckenden Angehörigen des russischen Volkes. Und denken Sie an die einschläfernde Wirkung eines Alexanders I., Nikolaus I. und aller derjenigen «I.», die nachgefolgt sind! Was heute gekommen ist, war also dasjenige, was hin wollte nach diesem Punkte, an dem die Bewußtseinsseele ihren Einschlag haben sollte in das europäische Leben.

[ 30 ] Davon wollen wir dann morgen weiterreden.

Eleventh Lecture

[ 1 ] In the course of these reflections, we have seen what an important point in the development of Western civilization the middle of the 19th century is. We have pointed out how, in the middle of the 19th century, there was, so to speak, a climax of materialistic thinking and a materialistic view of life; but we have also had to point out how what had been struggling to emerge in human beings since the beginning of the 15th century was actually something spiritual, so that one could say: The characteristic feature of this stage in the development of modern humanity was that, having become most spiritual, human beings were unable to grasp this spirituality, but instead filled themselves with materialistic thinking, materialistic feeling, and also materialistic willing and acting. And the present is still under the after-effects of what I would say has been accomplished unnoticed by many people and which has reached a climax in human evolution. What was the purpose of this climax? It was there because something decisive had to happen in relation to the attainment of the consciousness soul stage by modern humanity.

[ 2 ] If we consider how human evolution has unfolded, we must say that, beginning with the third post-Atlantean period, roughly until, say, the year 747 (see illustration) before the Mystery of Golgotha, we have what we can call the development of the sentient soul in humanity. Then begins the age of the intellectual or mind soul, which lasts until about 1413 and reaches its peak at a point in time about which external history tells us little, but which must be taken into account if we want to understand European development at all. This is approximately the time 333 after Christ. Since 1413, we have been dealing with the development of the consciousness soul, in which development we still find ourselves, and which experienced a decisive event around the year 1850, or rather 1840.

[ 3 ] Around the year 1840, the situation was such that if we consider humanity as a whole—how the individual nations behaved at that time, which we will begin to examine shortly—we can say that, insofar as we look at representative personalities of the nations, they stood at a point in 1840 where the intellect had already become mostly a shadow being. The intellect had taken on its shadow character. I tried to characterize this shadow character of the intellect for you yesterday. Humanity on the civilized earth had progressed to such an extent that from then on it was possible to gain the following feeling from general culture without initiation: We have the intellect, the intellect has developed, but this intellect has no content of its own. We have concepts, but these concepts are empty; we must fill them with something. This is the call that is going through humanity, so to speak, though still dark and inaudible. But in the deep, subterranean, subconscious longings of human beings lives the call for fulfillment of the shadowy aspects of intellectual thinking. It is precisely this call that leads to spiritual science. But we can also grasp this call in concrete terms.

[ 4 ] In the middle of the 19th century, human organization, in whose physical part this shadowy intellect is practiced, had simply progressed to such an extent that it was able to develop the intellect, the empty, shadowy intellect, very well. Now, something had to belong to this shadowy intellect; it had to be filled with something. It can only be filled if human beings become conscious of the fact that they must take in something that is not presented to them on earth itself, something that does not live on earth itself, something that they cannot experience in the life between birth and death. I must really take something into this mind that was erased when I descended from the spiritual soul worlds with the results of my previous earthly lives into physical corporeality, something that has been darkened but lies in the depths of my soul. I must bring it up from there, I must reflect on something that is in me simply because I am a human being of the 19th century.

[ 5 ] It was not previously the case that people could practice self-reflection in the same way. Therefore, they first had to develop their humanity to such an extent that the physical body became more and more mature in order to fully develop and practice the shadow-like intellect. Now the physical bodies, at least among the most advanced human beings, had reached the point where one could say, or rather, one can say since then: I want to reflect on what I am seeking to bring up from the depths of my soul life in order to pour into this shadowy intellect. This would have filled the shadow-like mind with something, and the consciousness soul would have dawned. So, at this point in time, there was, so to speak, an opportunity for the consciousness soul to dawn.

[ 6 ] Now you will say: Yes, but the whole time before that, since 1413, was the age of the consciousness soul. — Certainly, but it was first a preparatory development, and you need only consider what basic conditions were present in this age, as opposed to all previous ages, for such a preparation. This age saw, for example, the discovery of printing and the spread of writing. Since the 15th century, people have gradually absorbed a great deal of spiritual content through printing and writing. But they absorb it externally, and the essential feature of this age is that an enormous amount of spiritual content has been absorbed externally. The peoples of the civilized world have outwardly absorbed something that they could previously only absorb in large numbers through audible language. In the age of intellectual development, and even more so in the age of the sentient soul, all dissemination of education was based on oral speech. Something of the spiritual soul still resonates through language. In earlier times, words were imbued with what might be called the “genius of language.” This ceased when the content of human education was absorbed in abstract form through writing and printing. The printed and written word has the peculiarity of erasing, in a certain sense, what human beings receive at birth from their super-earthly existence.