Materialism and the Task of Anthroposophy

GA 204

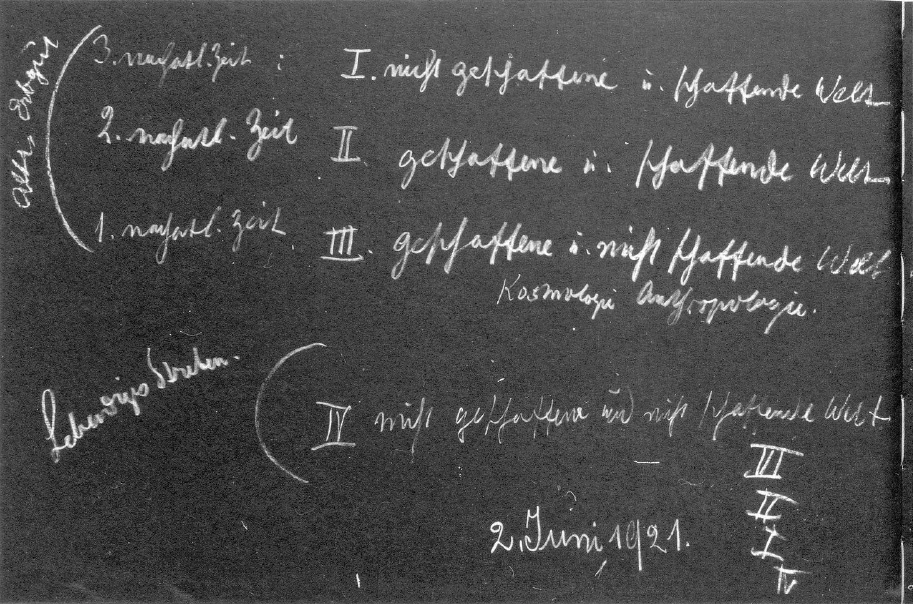

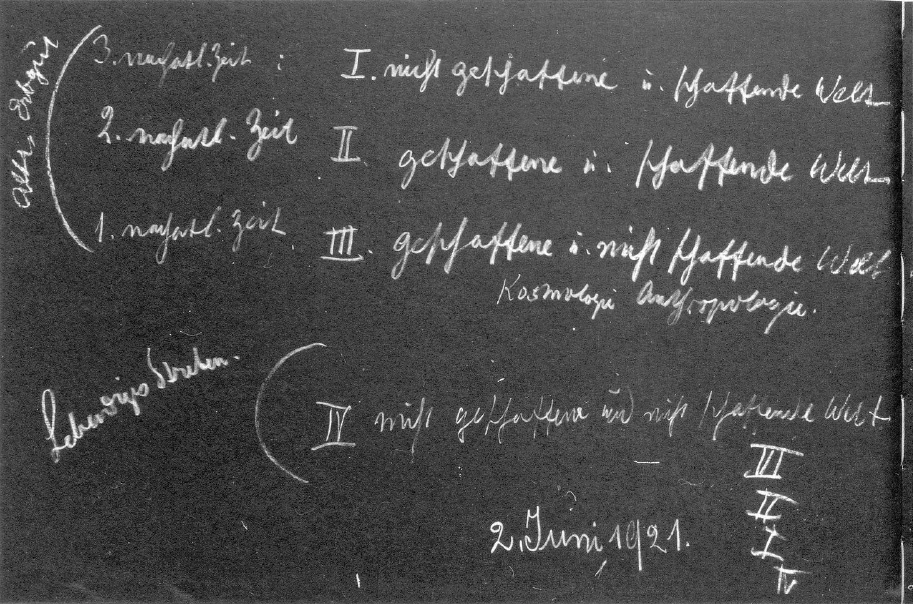

Dornach, June 2, 1921

Lecture XV

In the past few weeks, I have repeatedly spoken of the great change that took place in Western civilization during the fourth century A.D. When such a matter is discussed, one is obliged to point out one thing again and again, that has already been the subject of discussion here many times. Yet it is necessary to focus on it time and again. I am referring to the metamorphoses of human development, markedly differing from each other on the soul level. When speaking of such a major point in human evolution as the one in the fourth century, one has to pay heed to the fact that the soul life of humanity changed in a sense with one great leap.

This view is not prevalent today. The prevailing opinion holds that the human race has undergone a certain history. This history is traced back to about the third or fourth millennium along the lines of the most recent documented records. Then, going back further, there is nothing for a long time; finally, one arrives at animalistic-human conditions. But in regard to the duration of the historical development, it is assumed that human beings have in the main always thought and felt the way they do today; at most, they formerly adhered to a somewhat more childish stage of scientific pursuit. Finally, however, human beings have struggled upward to the level of which we say today that it is splendid how far we have come in the comprehension of the world. To be sure, a reasonably unbiased consideration of human life arrives at the opposite view. I have had to indicate to you the presence of a mighty transition in the fourth Christian century; I outlined the other change in the whole human soul life at the beginning of the fifteenth century. Finally, I described how a turning point in human soul life occurred also during the nineteenth century.

Today, we shall consider one detail in this whole development. I would like to place before you a personality who illustrates particularly well that human beings in the relatively recent past thought completely differently from the way we think today. The personality, who has been mentioned also in earlier lectures, is John Scotus Erigena,1Johannes Scotus Erigena, 810–877, Irish philosopher of scholasticism in Paris. who lived in the ninth century A.D. at the court of Charles the Bald in France.2Charles the Bald, 828–877, king of the Franconians, emperor from 875–877. Erigena, whose home was across the Channel, who was born approximately in the year 815 and lived well into the second half of the ninth century, is truly a representative of the more intimate Christian mode of thinking of the ninth century A.D. It is, however, a manner of thinking that is still completely under the influence of the first Christian centuries. John Scotus Erigena apparently was intent on immersing himself in the prevalent scholarly and theological culture of his time. In his age, scholarly and theological knowledge were one and the same. And such learning was most readily acquired across the British Channel, particularly in the Irish institutions where Christianity was cultivated in a certain esoteric manner. The Franconian kings then had ways of attracting such personalities to their courts. The Christian knowledge permeating the Franconian kingdom, even spreading from there further east into western Germany, was mainly influenced by those who had been attracted from across the Channel by these Franconian kings.

John Scotus Erigena also immersed himself into the contents of the writings by the Greek Church Fathers, studying also the texts of a certain problematic nature within Western civilization, namely, the texts by Dionysius the Areopagite.3Dionysius the Areopagite: connected Christianity with neo-Platonic philosophy. Had strong influence on medieval mysticism. As you know, the latter is considered by some to be a direct pupil of Paul. Yet, these texts only surfaced in the sixth century, and many scholars therefore refer to them as pseudo-Dionysian writings composed in the sixth century by an unknown person, which were then accredited to Paul's disciple.

People who say that are ignorant of the way spiritual knowledge was passed on in those early centuries. A school like the one in which Paul himself taught in Athens possessed insights that initially were taught only orally. Handed down from generation to generation, they were finally written down much, much later on. What was thus recorded at a later time, was not necessarily anything less than genuine for that reason; it could preserve to some extent the identity of something that was centuries old. Furthermore, the great value that we place on personality today was certainly not attached to personality in those earlier ages. Perhaps we will be able to touch upon a circumstance in this lecture that must be discussed in connection with Erigena, namely, why people did not place much value on personality in that age.

There is no doubt about one thing: The teachings recorded in the name of Dionysius the Areopagite were considered especially worthy of being written down in the sixth century. They were considered the substance of what had been left from the early Christian times, which were now in particular need of being recorded. We should consider this fact as such to be significant. In the times prior to the fourth century, people simply had more confidence in memory working from generation to generation than they had in later periods. In earlier ages, people were not so eager to write everything down. They were aware, however, that the time was approaching when it would become increasingly necessary to write down things that earlier had been passed on by word of mouth with great ease; for the things that were then recorded in the writings of Dionysius were of a subtle nature.

Now, what John Scotus Erigena was able to study in these writings was certainly apt to make an extraordinarily profound impression on him. For the mode of thinking found in this Dionysius was approximately as follows. With the concepts we from and the perceptions we acquire, we human beings can comprehend the physical sensory world. We can then draw our conclusions from the facts and beings of this sensory world by means of reasoning. We work our way upward, as it were, to a rational content that is then no longer visually perceptible but is experienced in ideas and concepts. Once we have developed our concepts and thoughts from the sensory facts and beings, we have the urge to move upward with them to the supersensory, to the spiritual and divine.

Now, Dionysius does not proceed by saying that we learn this or that from the sensory things; he does not say that our intellect acquires its concepts and then goes on to deduce a deity, a spiritual world. No, Dionysius says, the concepts we acquire from the things of the senses are all unsuitable to express the deity. No matter how subtle the concepts we form of sensory things, we simply cannot express what constitutes divinity with the aid of these concepts. We must therefore resort to negative concepts rather than positive ones. When we encounter our fellowmen, for example, we speak of personality. According to this Dionysian view, when we speak of God, we should not speak of personality, for the concept of personality is much too small and too lowly to designate the deity. Rather we should speak of super-personality. When referring to God, we should not even speak of being, of existence. We say, a man is, an animal, a plant is. We should not ascribe existence to God in the same sense as we attribute existence to us, the animals, and the plants; to Him, we ought to ascribe a super-existence. Thus, according to Dionysius, we should try to rise from the sensory world to certain concepts but then we should turn them upside down, as it were, allowing them to pass over into the negative. We should rise from the sense world to positive theology but then turn upside down and establish negative theology. This negative theology would actually be so sublime, so permeated by God and divine thinking that it can only be expressed in negative predicates, in negations of what human beings can picture of the sensory world.

Dionysius the Areopagite believed he could penetrate into the divine spiritual world by leaving behind, so to speak, all that can be encompassed by the intellect and thus finding the way into a world transcending reason.

If we consider Dionysius a disciple of Paul, then he lived from the end of the first Christian century into the second one. This means that he lived a few centuries prior to the decisive fourth century A.D. He sensed what was approaching: The culmination point of the development of human reason. With a part of his being, Dionysius looked back into the days of antiquity. As you know, prior to the eighth century B.C., human beings did not speak of the intellect in the way they did after the eighth century. Reason, or the rational soul was not born until the eigth century B.C., and from the birth of the rational soul originated the Greek and Roman cultures. These then reached their highest point of development in the fourth century A.D. Prior to this eighth century B.C. people did not perceive the world through the intellect at all; they perceived it directly, through contemplation. The early Egyptian and Chaldean insights were attained through contemplation; they were attained in the same manner in which we acquire our external sensory insights, despite the fact that these pre-Christian insights were spiritual insights. The spirit was perceived just as we today perceive the sensory world and as the Greeks already perceived the sensory world. Therefore, in Dionysius the Areopagite, something like a yearning held sway for a kind of perception lying beyond human reason.

Now, in his mind, Dionysius confronted the mighty Mystery of Golgotha. He dwelled in the intellectual culture of his time. Anybody studying the writings of Dionysius sees—regardless of who Dionysius was—how immersed this man was in all that the intellectual culture of his time had produced. He was a well educated Greek but at the same time a man whose whole personality was imbued with the magnitude of the Mystery of Golgotha. He was a man who realized that regardless of how much we strain our intellect, we cannot comprehend the Mystery of Golgotha and what stands behind it. We must transcend the intellect. We have to evolve from positive theology to negative theology.

When John Scotus Erigena read the writings of this Dionysius the Areopagite, they made a profound impression on him even in the ninth century. For what followed upon the fourth Christian century had more of an Augustine character and developed only slowly in the way I described in the earlier lectures. The mind of such a person, particularly of one of those who had trained themselves in the schools of wisdom over in Ireland, still dwelled in the first Christian centuries; he clung with all the fibers of his soul to what is written in the texts of Dionysius the Areopagite. Yet, at the same time, John Scotus Erigena also had the powerful urge to establish by means of reason, by what the human being can attain through his intellect, a kind of positive theology, which, to him, was philosophy. He therefore diligently studied the Greek Church Fathers in particular. We discover in him a thorough knowledge, for example of Origen,4Origen, around 185–254, Greek Church Father in Alexandria, later presbyter in Caesarea; basis of his philosophical theology: De principiis (“Peri archon”). Under Justinian I, during the fifth ecumenical council in Constantinople in 553, his teachings were condemned as heretical. who lived from the second to the third century A.D.

When we study Origen, we actually discover a world view completely different from the Christian view, that is from what appeared later as the Christian view. Origen definitely still holds the opinion that one has to penetrate theology with philosophy. He believes that it is only possible to examine the human being and his nature only if he is considered as an emanation of the deity, as having had his origin in God. Then, however, man lowered himself increasingly; yet through the Mystery of Golgotha, he has gained the possibility of ascending once again to the deity in order once more to unite with God. From God into the world and back to God—this is how one could describe the path that Origen perceived as his own. Basically, something like this also underlies the Dionysian writings, and then was passed on to such personalities as John Scotus Erigena. But there were many others like him.

One could say that it is a sort of historical miracle that posterity came to know the writings of John Scotus Erigena at all. In contrast to other texts of a similar nature from the first centuries that have been completely lost, Erigena's writings were preserved until the eleventh, twelfth, a few even until the thirteenth century. At that time, they were declared heretical by the Pope; the order was given to find and burn all copies. Only much later, manuscripts from the eleventh and thirteenth century were rediscovered in some obscure monastery. In the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries, people knew nothing of John Scotus Erigena. His writings had been burned like so many other manuscripts5After the Church had forbidden the reading of Scotus Erigena's texts, all editions were ordered burned in 1225. of a similar content from that period. From Rome's point of view the search was more successful in the case of other manuscripts: all copies were fed to the flames. Yet, of Erigena's works, a few copies remained.

Now, considering the ninth century and also taking into account that in John Scotus Erigena we have an expert in the wisdom and insights of the first Christian centuries, we must conclude the following. He is a characteristic representative of what extended form an earlier age, from the time preceding the fourth century, into later periods. One could say that in these later times, all knowledge had ossified in the dead Latin language. All the wisdom of the spiritual world that had been alive earlier became ossified, dogmatized, rigid, and intellectualized. Yet, in people like Erigena lived something of the ancient aliveness of direct spiritual knowledge that had existed in the first Christian centuries and was utilized by the most enlightened minds to comprehend the Mystery of Golgotha.

For a time, this wisdom had to die out in order for the intellect of man to be cultivated from the first third of the fifteenth century until our era. While the intellect as such is a spiritual achievement of the human being, initially it turned only to the material realm. The ancient wealth of wisdom had to die so that the intellect in its shadowy nature could be born. If, instead of immersing ourselves in a scholarly, pedantic manner into his writings, we do so with our whole being, we will notice that through Scotus Erigena something had spoken out of soul depths other than those from which people spoke later on. There, the human being had still spoken out of mental depths that subsequently could no longer be reached by human soul life. Everything was more spiritual, and if human beings spoke intellectually at all, they spoke of matters in the spiritual realm.

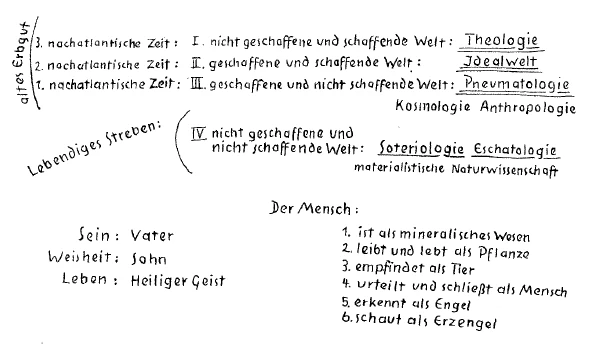

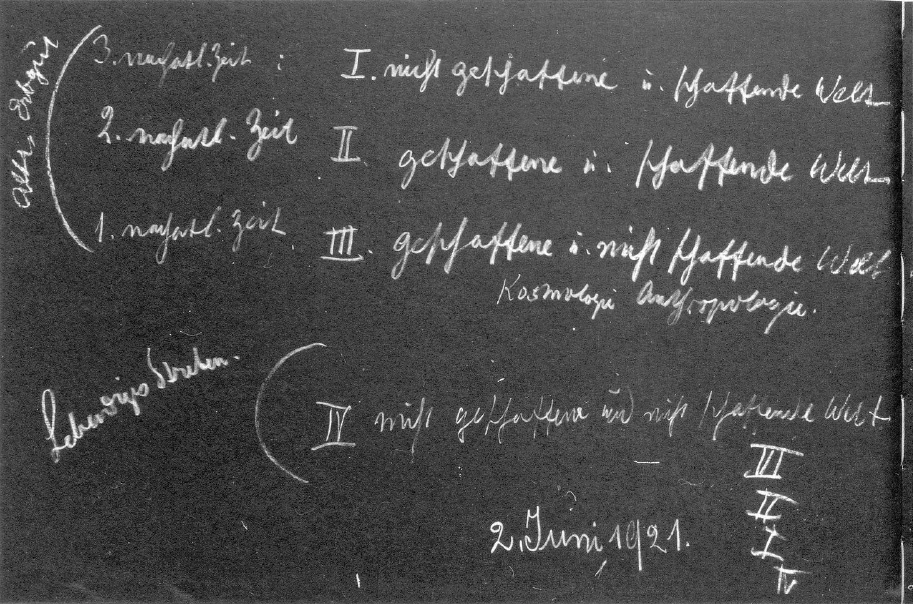

It is extremely important for one to scrutinize carefully what the structure of Erigena's knowledge was like. In his mighty work on the divisions of nature that has come down to posterity in the manner I described, he divided what he had to say concerning the world in four chapters. In the first, he initially speaks of the uncreated and the created world (see outline below). In the way Erigena believed himself able to do it, the first chapter describes God and the way He was prior to His approaching something like the creation of the world.

Ancient Legacy

3. post-Atlantean Age: |

I. Uncreated and created |

2. post-Atlantean Age: |

II. Created and creating |

1. post-Atlantean Age: |

III. Created and noncreating |

Living Striving: |

IV. Uncreated and noncreating world: Soteriology, Eschatology |

The Human Being

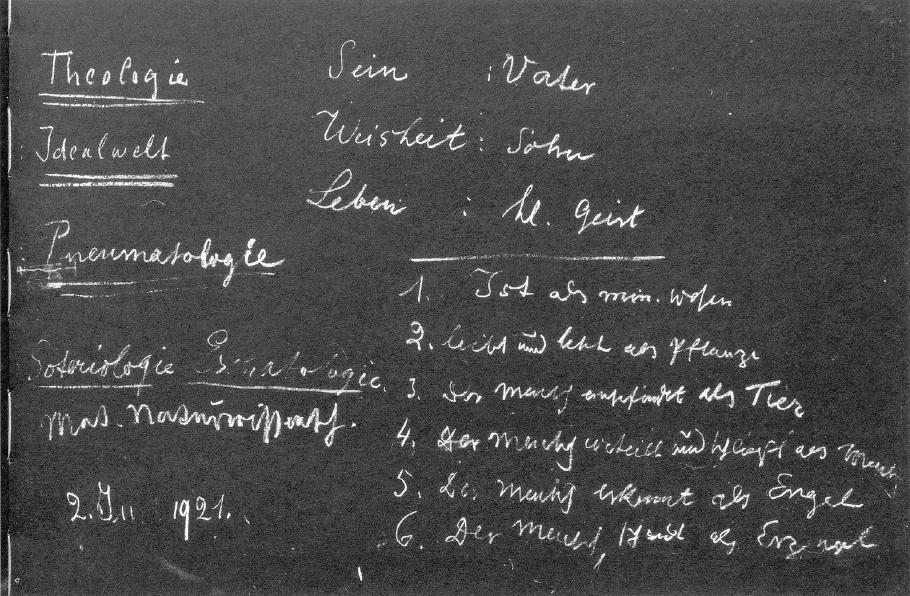

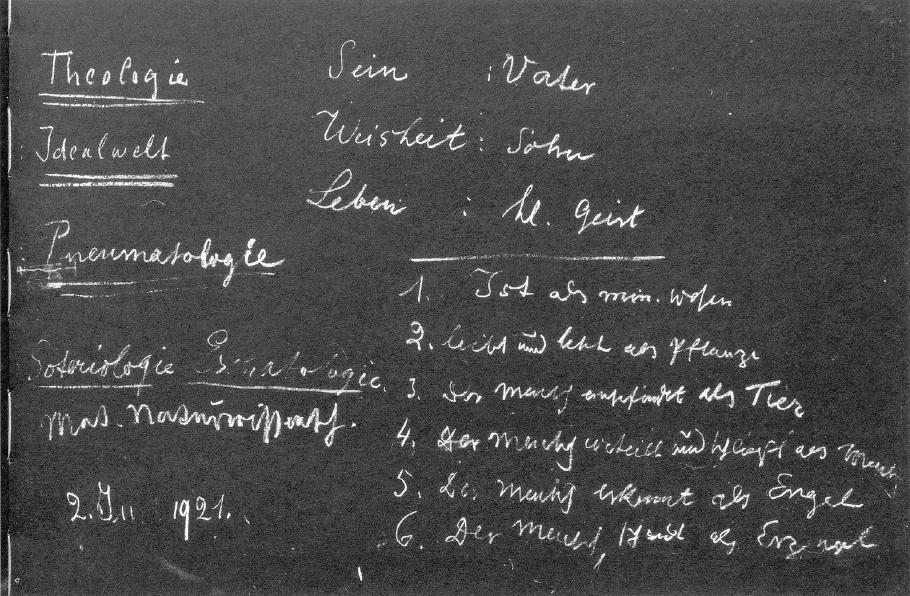

Existence: Father |

1. is as a mineral being. |

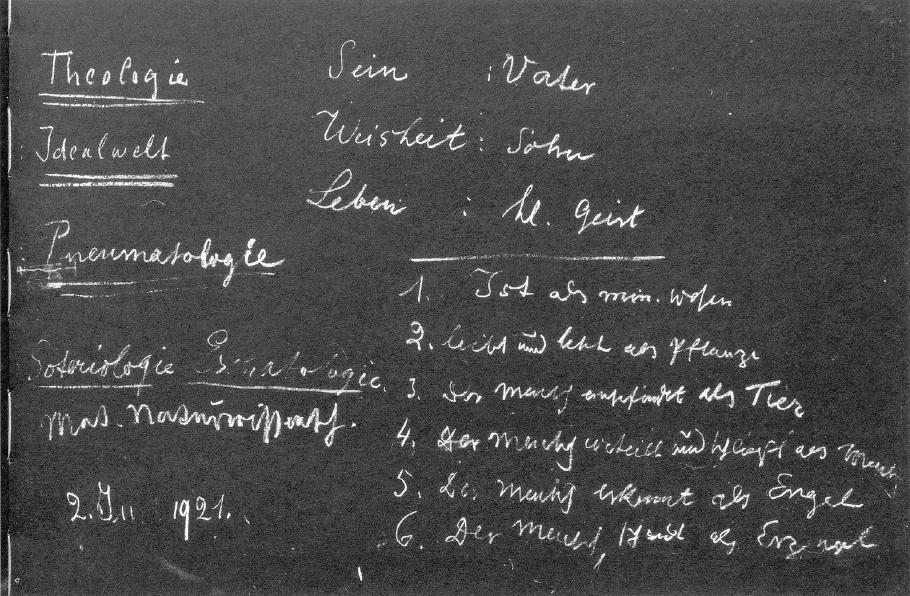

John Scotus Erigena clearly describes this in the way he learned through the writings of Dionysius. He describes by means of developing the most refined intellectual concepts. At the same time, he is aware that with them he only reaches up to a certain limit beyond which lies negative theology. He therefore merely approaches the actual true being of the spirit, of the divine. Among other topics, we find in this chapter the beautiful discourse about the Trinity, instructive even for our age. He states that when we view the things around us, we initially discover existence as an overall spiritual quality (see above). Existence embraces everything. Now, we should not attribute existence as possessed by things to God. Yet, looking upward to existence transcending existence, we cannot but speak summarily of the deity's existence.

Likewise, we find that things in the world are illuminated and permeated by wisdom. To God, we should not merely ascribe wisdom but wisdom beyond wisdom. But when we proceed from things, we arrive at the limit of wisdom-filled things. Now, there is not only wisdom in all things. They live; there is life in all things. Therefore, when Erigena calls to mind the world, he says: I see existence, wisdom, life in the world. The world appears to me in these aspects as an existing, wisdom-filled, living world. To him, these are three veils, so to speak, that the intellect fashions when it surveys all things. One would have to see through these veils, then, to see into the divine-spiritual realm. To begin with, Erigena describes these veils: When I look upon existence, this represents the Father to me; when I look upon wisdom, it represents the Son to me; when I look upon life, it represents the Holy Spirit in the universe.

As you can see, John Scotus Erigena certainly proceeds from philosophical concepts and then makes his way up to the Christian Trinity. Inwardly, proceeding from the comprehensible, he still experiences the path from there to the so-called incomprehensible. Indeed, of this he is convinced. Yet, from the way he speaks and presents his insights we can see that he has learned from Dionysius. Precisely when he arrives at existence, wisdom, and life, which to him represent the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, he would really like to have these concepts dissolve in a general spiritual element into which the human being would then have to rise by transcending concepts. However, he does not credit the human being with the faculty of arriving at a state of mind that goes beyond the conceptual.

In this, John Scotus Erigena was a product of the age that developed the intellect. Indeed, if this age had understood itself correctly, it would have had to admit that it could not enter into the realm transcending the conceptual level.

The second chapter then describes something like a second sphere of world existence, the created and the creating world (see above). It is the world of the spiritual beings where we find the angels, the archangels, the Archai, and so on. This world of spiritual beings, mentioned already in the writings of Dionysius the Areopagite. is creative everywhere in the world. Yet this hierarchical world is itself created; it is begun, hence created, by the highest being and in turn is active creatively in all details of existence surrounding us.

In the third chapter, Erigena then describes as a third world the created world that is noncreating. This is the world we perceive around us with our senses. It is the world of animals, plants, and minerals, the stars, and so on. In this chapter, Erigena deals with almost everything we would designate as cosmology, anthropology, and so forth, all that we would call the realm of science.

In the fourth chapter, Erigena deals with the world that has not been created and does not create. This is again the deity, but the way it will be when all creatures, particularly all human beings, will have returned to it. It is the Godhead when it will no longer be creating, when, in blissful tranquility—this is how John Scotus Erigena imagines it—it will have reabsorbed all the beings that have emerged from it.

Now, in surveying these four chapters, we find contained in them something like a compendium of all traditional knowledge of the schools of wisdom from which Scotus Erigena had come. When we consider what he describes in the first chapter, we deal with something that can be called theology in his sense, the actual doctrine of the divine.

Considering the second chapter, we find in it what he calls in terms of our present-day language the ideal world. The ideal is pictured, however, as existing. For he does not describe abstract ideas but angels, archangels, and so forth. He pictures the whole intelligible world, as it was called. Yet it was unlike our modern intelligible world; instead it was a world filled with living beings, with living, intelligible entities.

As I said, in the third chapter Erigena describes what we would term science today, but he does so in a different way. Since the days of Galileo and Copernicus, who, after all, lived later, we no longer possess what was called cosmology or anthropology in Scotus Erigena's age. Cosmology was still described from the spiritual standpoint. It depicted how spiritual beings direct and also inhabit the stars, how the elements, fire, water, air, and earth are permeated by spiritual beings. What was described as cosmology, was indeed something different. The materialistic way of viewing things that has arisen since the middle of the fifteenth century did not yet exist in Erigena's time, and his form of anthropology also differed completely from what we call anthropology in our materialistic age.

Here, I can point out something extraordinarily characteristic for what anthropology is to John Scotus Erigena. He looks at the human being and says: First, man bears existence within himself. Hence, he is a mineral being, for he contains within himself a mineral nature (see outline above). Secondly, man lives and thrives like a plant. Third, man feels as does the animal. Fourth, man judges and draws conclusions as man. Fifth, man perceives as an angel.

It goes without saying that in our age this would be an unheard-of statement! When John Scotus Erigena speaks of judgment and conclusions, something that is done, for instance, in a legal court where one pronounces judgment over somebody—then, so he says, human beings do this as human beings. But when they perceive, when they penetrate the world in perception then human beings do not behave as human beings but as angels! The reason for pointing this out is that I am trying to show you that for that period anthropology was something different from what it is for our present age. For it is true that you could hardly hear anywhere, not even in a theological seminar, that human beings perceive as angels. Therefore, one is forced to conclude that our science no longer resembles what Erigena describes in the third chapter. It has turned into something different. If we wanted to call Erigena's science by a word that is no longer applicable to anything existing today, we would have to say that it was a spiritual doctrine of the universe and man, pneumatology.

Now to the fourth chapter: This contains, first of all, Erigena's teaching of the Mystery of Golgotha and the doctrine concerning what the human being has to expect in the future, namely, entrance into the divine-spiritual world, hence, what in modern usage would be called soteriology. “Soter,” after all, means savior; the teaching of the future is eschatology. We find that Erigena here deals with the concepts of the Crucifixion and Resurrection, the emanation of Divine Grace, man's path into the divine-spiritual, world, and so on.

There is one thing that truly holds our attention, if we study attentively a work such as the De divisione naturae by John Scotus Erigena about the divisions of nature. The world is definitely discussed as something that is perceived in spiritual qualities. He speaks of something spiritual as he observes the world. But what is not contained in this work? We have to pay attention, after all, to what is not included in a universal science such as Erigena is trying to establish there.

In John Scotus Erigena's work, you discover as good as nothing of what we call sociology today, social science, and things of that kind. One is almost inclined to say it appears from the way Erigena pictures human beings that he did not wish to give mankind social sciences, no more so than any animal species, say the lion, the tiger, or any bird species, would come out with a sociology if it produced some sort of science. For a lion would not talk about the way it ought to live together with the other lions or how it ought to acquire its food and so on; this is something that comes instinctively. Just as little could we imagine a sociology of sparrows. Surely sparrows could reveal any number of the most interesting cosmic secrets from their viewpoint, but they would never produce any teaching about economics, for sparrows would consider this a subject that goes without saying, something they do because their instinct tells them to do it.

This is what is remarkable: Because we discover as yet nothing like this in Erigena's writings, we realize that he still viewed human society as if it produced the social elements out of its instincts. With his special kind of insight, he points to what still lived in the human being in the form of instincts and drives, namely, the impulses of social living. What he describes transcends this social aspect. He describes how the human being had emerged from the divine, and what sort of beings exist beyond the sense world. Then, in a form of pneumatology, he shows how the spirit pervades the sensory world, and he presents the spiritual element that penetrated into the world of the senses in his fourth chapter on soteriology and eschatology. Nowhere is there a description, however, of how human beings ought to live together. I should say, everything is elevated above the sensory world. It was generally a characteristic of this ancient science that everything was elevated beyond the sense world.

Now, if we contemplate writings such as John Scotus Erigena's teaching in a spiritual scientific sense, we discover that he did not think at all with the same organs humanity thinks with today. We simply do not understand him if we try to understand him with the thinking employed by mankind today. We understand him only when, through spiritual science, we have acquired an idea of how to think with the etheric body, the body that, as a more refined body, underlies the coarse sensory corporeality.

Thus Erigena did not think with the brain but with the etheric body. In him, we simply have a mind which did not yet think with the brain. Everything he wrote down came into being as a result of thinking with the etheric body. Fundamentally speaking, it was only subsequent to his age that human beings began to think with the physical body, and only since the beginning of the fifteenth century did people think totally with the physical body. It is normally not recognized that during this period the human soul life has truly changed, and that if we go back into the thirteenth, twelfth, and eleventh centuries, we encounter a form of thinking that was not yet carried out with the physical but with the etheric body. This thinking with the etheric body was not supposed to extend into later ages when, dialectically and scholastically, people discussed rigid concepts. This former thinking with the etheric body, which certainly was the form of thinking employed during the first Christian centuries, was declared to be heretical. This was the reason for burning Erigena's writings. Now, the actual soul condition of a thinker in that age becomes comprehensible.

Going back to earlier times, we find a certain form of clairvoyance in all people. Human beings did not think at all with their physical body. In past ages, they thought with their etheric body and carried on their soul life even with the astral body. There, we should not speak of thinking at all, since the intellect only originated in the eighth century B.C., as I have pointed out. However, certain remnants of this ancient clairvoyance were retained, and it is particularly true of the most outstanding minds that with the intellect, which had already come into being, they tried to penetrate into the knowledge that had been handed down through tradition from former ages. People tried to comprehend what had been viewed in a completely different manner in past times. They tried to understand, but now had to have the support of abstract concepts such as existence, wisdom, life. I would say that these individuals still knew something of an earlier spirit-permeated insight and at the same time felt quite at home within the purely intellectual perception.

Later on, when the intellectual perception had turned into a shadow, this was not felt anymore. Earlier, however, people felt that in past ages insights had existed that permeated human beings in a living way out of spiritual worlds, it was not something merely thought up. Erigena lived in such a divided state. He was only capable of thinking, but when this thinking arrived at perception, he sensed that there was something of the ancient powers that had permeated the human being in the ancient manner of perception. Erigena felt the angel, the angelos, within himself. This is why he said that human beings perceive as angels. It was a legacy from ancient times, extending into his age of intellectual knowledge, that made it possible for a mind like Scotus Erigena's to say that man perceives like an angel. In the days of the Egyptian, Chaldean, and the early ages of the Hebrew civilization, nobody would have said anything else but: The angel perceives within me; as a human being, I share in the knowledge of the angel. The angel dwells within me, he cognizes, and I take part in what he perceives.

This was true of the era when reason did not yet exist. When the intellect had appeared, it became necessary to penetrate this older knowledge with reason. In Scotus Erigena, however, there still existed an awareness of this state of permeation with the angel nature.

Now, it is a strange experience to become involved in this work of Erigena's and to try and understand it completely. You finally arrive at a feeling of having read something most significant, something that still dwells very much in spiritual regions and speaks of the world as something spiritual. But then, in turn, the feeling arises that everything is basically mixed up. You realize that with this text you find yourself in the ninth century when the intellect had already brought much confusion. And this is truly the case. For if you read the first chapter, you are dealing with theology. But it is a theology that is certainly secondary even for John Scotus Erigena, a theology which evidently points back to something greater and more direct. I shall now speak as if all these matters were hypotheses, but what I now develop as a hypothesis can be established by spiritual science as a fact. A condition must once have existed, and we look back on it, when as yet theology was not addressed in such an intellectual manner but was considered to be something one delved into in a living way. Without doubt, it was that kind of theology the Egyptians spoke of, those Egyptians of whom the Greeks—I mentioned it above—report that Egyptian sages told them: You Greeks are like children;6These words are reported by Plato in Timaios, 22 B.C. you have no knowledge of the world's origin, we do possess this sacred knowledge of the world's beginnings.

Obviously, the Greeks were being referred to an ancient, living theology. Thus, we have to say: During the time of the third post-Atlantean period, which begins in the fourth millennium and ends in the first millennium B.C. in the eighth pre-Christian century, approximately in the year 747 B.C., there existed a living theology. It now needed to be penetrated by Erigena's intellect. It was obviously present in a much more vital form to the personality who must be recognized as Dionysius the Areopagite. Dionysius had a much more intense feeling for this ancient theology. He felt that it was something that existed but could no longer be approached, that becomes negative as one tries to approach it. Based on the intellect, so he thought, one can only arrive at positive theology. Yet, with the term, negative theology, he was really referring to an ancient theology that had disappeared.

Again, when we consider what appears in the second chapter as the ideal world, we could believe that it is something modern. That, however, is not the case, That ideal world actually is identical with a true idea of what appears in the ancient Persian epoch, just as I described it in my Occult Science, hence in the second post-Atlantean period. Among Plato and the Platonists, this ancient Persian living world of angels, the world of the Amshaspands, and so on, had already paled into the world of ideals and ideas due to a later development. Yet, what is actually contained in this ideal world and is clearly discernible in Scotus Erigena goes back to this second ancient Persian age.

What appears in Erigena's book as pneumatology, as a kind of pantheism is not vague and nebulous such as is frequently the case today, but a pantheism that is alive and spiritual, though dimmed in Erigena's writing. This pneumatology is the last remnant, the very last vestige filtered out of the first post-Atlantean, ancient Indian period.

And what about the fourth chapter? Well, it contains Erigena's living perception of the Mystery of Golgotha and the future of humanity. We hardly speak of this anymore today. As an ancient tradition, it is still mentioned by theologians, but they know of it only in rigidified dogmas. They even deny that man could attain such insight through living knowledge. But it did originate from what was thus cultivated as soteriology and eschatology. You see, the theology of former times was handed over, as it were, to the councils; there, it was frozen into dogmas and incorporated into Christology. It was not to be touched anymore. It was viewed as impenetrable to perception. It was removed, so to speak, from what was carried out in schools by means of knowledge. As it was, exoteric matters were already being preserved like nebulous formations from ancient times. But at least the activities in schools were to be linked with thoughts that emerged in the age of thinking. They were to be connected, after all, with the Mystery of Golgotha and the future of mankind. There, one spoke of the Christ being's rule among human beings; one spoke of a future day of judgment. The concepts that people could come up with were used for that.

Thus, we see that Scotus Erigena actually records the first three chapters as though they had been handed down to him. Finally, he applies his own intellect to the fourth chapter but in such a manner that he speaks of things that far surpass the physical, sensory world, yet have something to do with this world. We realize that he took pains to apply the intellect to eschatology and soteriology. After all, we know the kind of scholarly disputes and discussions Scotus Erigena was involved in. For example, he was involved in discussions of the question whether in Communion, that is, in something that was related to the Mystery of Golgotha, human beings confront the actual blood and the actual body of Christ. He took part in all the discussions of human will, its freedom and lack of freedom in connection with divine grace. Hence, he honed and schooled his intellect in regard to everything that was the subject of his fourth chapter. This is what people discussed then.

We could say that the content of the first three chapters was an ancient tradition. One did not change it much but simply communicated it. The fourth chapter, on the other hand, was a living striving; there, the intellect was applied and schooled.

What became of this intellect that was schooled there? What happened to the concepts of soteriology and eschatology arrived at by people like Scotus Erigena in the ninth century? You see, my dear friends, since the middle of the fifteenth century this has become our science, the basis of the perception of nature. Once, people employed the intellect in order to consider whether bread and wine in the Sacrament are transformed into the body and blood of Christ. They pondered whether grace is bestowed on man in one way or another. This same intellect was later used to consider whether the molecule consists of atoms and whether the sun's body consists of one form of substance or another, and so on. It is the continuation of the theological intellect that inhabits natural science today. Precisely the same intellect that stimulated Scotus and the others who were involved with him in the dispute over Communion—and the discussions were indeed very lively in those days—survived in the teachings of Galileo and Copernicus. It survived in Darwinism, even, say, in Strauss's materialism. It has lived on in a straight line. You know that the old is always preserved alongside the new. Therefore, the same intellect that in David Friedrich Strauss hatched the book The Old and the New Faith, which preaches total atheism, occupied itself in those days, with soteriology and eschatology; it continues in a straight line.

We could therefore say that if this book had to be written today based as much on modern conditions as Scotus Erigena based what he wrote on the conditions of his age, then, here (referring to outline above), total atheism would not appear, but rather our natural science. For, naturally, complete atheism would contradict the first chapter. In the ninth century soteriology and eschatology still appeared there, for then the intellect was applied to other things. But here, (see p. 281), materialistic science would emerge today. History reveals to us nothing else but this. Now, we can perhaps see what becomes evident from the whole conception of this work.

Basically, what is listed here (outline above) would have to appear in a different sequence. The third chapter would have to read: world view of the first post-Atlantean age. The second chapter, would have to read: world view of the second post-Atlantean age, and the first chapter: world view of the third post-Atlantean age. In the sense of Scotus Erigena—who lived in the fourth post-Atlantean age that only came to an end in the fifteenth century—the last chapter applies to the fourth post-Atlantean epoch. The sequence (in the outline) would therefore have to be: III, II, I, IV. This is what I meant when I said earlier that one receives the impression that things are actually mixed up. Scotus Erigena simply possessed bits of the ancient legacy but he did not list them in accordance with their sequence in time. They were part of the knowledge of his age, and he mentioned them in the order in which they were most familiar to him. He listed the nearest at hand as the highest; the others appeared so nebulous to him that he considered them to be inferior.

Yet, the fourth chapter is nevertheless most remarkable. Let us try to understand from a certain viewpoint what it should actually be. Let us go back into pre-Christian times. If we were to seek among the Egyptians a representative mind such as Scotus Erigena was for the ninth century, such a person would still have known something concerning theology in a most lively way. He would have had even more alive concepts of the ideal or angelic world, of the sphere that illuminates and permeates the whole world with spirit. He would still have known all that and would have said: In the very first age, there once existed a human world view that beheld the spirit in all things. But then, the spirit was abstractly lifted up into the heights. It became the ideal world, finally the divine world. Then, the fourth epoch arrived. It was supposed to be even more spiritualized than the theological epoch. This Greco-Latin period was really supposed to be more spiritualized than the third epoch. And above all, the fifth which then followed, namely our time, would have to be an even more spiritualized era, for with materialistic science in place of soteriology or eschatology it would have to be listed in fourth place, or we would have to add a fifth listing with our natural science, and the latter would have to be the most spiritual view.

Yet, in fact, my dear friends, matters are buried. We hear Scotus Erigena saying that man exists as a mineral being, lives and thrives as a plant, feels as an animal, judges and draws conclusions as a human being, perceives as an angel—something Erigena still knew from ancient traditions. Now, we who aspire to spirit knowledge would have to go even further. We would have to say: Right, human beings exist as mineral beings, live and thrive as plants, feel as animals, judge and draw conclusions as human beings, perceive as angels and, sixth, human beings behold—namely, imaginatively, the spiritual world—as archangels. When we speak of the human being since the first third of the fifteenth century, we would have to ascribe to ourselves the following. We perceive as angels and develop the consciousness soul by means of soul faculties of vision—to begin with, unconsciously, but yet as consciousness soul—as archangels.

Thus, we face the paradox that in the materialistic age human beings actually live in the spiritual world, dwelling on a higher spiritual level than they did in earlier times. We can actually say: Yes, Scotus Erigena is right, the angel experience is awakening in man, but the archangel experience is also awakening since the first third of the fifteenth century. We should rightfully be in a spiritual world.

In realizing this, we could really look back also to a passage in the Gospels that is always interpreted in a most trivial way, namely, the one saying: The end of the world is near and the kingdoms of heaven are at hand. Yes, my dear friends, when we have to say of ourselves that in us the archangel is developing vision so that we can receive the consciousness soul, then there results a strange view of this approach of the heavens. It appears that it is necessary to revise such conceptions of the New Testament once more from the standpoint of spiritual science. These views are very much in need of revision, and we really have two tasks: First, to understand whether our age is not actually meant to to be different than the age when Christ walked on earth and whether the end of the world of which Christ spoke might not be something we have behind us already? This is the one task we confront. And if it is true that we have the so-called end of the world behind us and we therefore already face the spiritual world, then we would have to explain why it has such an unspiritual appearance, why it has become so material, arriving finally at that terrible, astounding life that characterizes the first third of the twentieth century? Two mighty and overwhelming questions place themselves before our soul. We shall continue speaking about that tomorrow.

Fünfzehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich habe wiederholt in diesen verflossenen Wochen über den großen Umschwung gesprochen, der sich in der abendländischen Zivilisation vollzogen hat innerhalb des 4.. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts. Wenn eine solche Sache besprochen wird, dann muß man immer wieder auf etwas hinweisen, das ja auch oftmals schon hier den Gegenstand der Betrachtungen gebildet hat, das aber immer wieder notwendig ist ins Auge zu fassen; ich meine die stark voneinander seelisch sich unterscheidenden Metamorphosen der menschlichen Entwickelung. Wenn man von einem solchen Hauptpunkte in der menschlichen Entwickelung spricht, wie er fällt in das 4. nachchristliche Jahrhundert, so muß man eben aufmerksam darauf sein, daß das seelische Leben der Menschen sich ja gewissermaßen mit einem Sprung geändert hat. Diese Ansicht hat man ja heute eben nicht. Man hat heute schon einmal die Ansicht: Nun, das Menschengeschlecht hat eine Geschichte durchgemacht, die verfolgt man zurück, sagen wir etwa bis in das 3., 4. Jahrtausend nach den neuesten Urkunden; dann folgt lange, wenn man zurückgeht, nichts, bis man zu den ganz noch tierisch-menschlichen Zuständen gelangt. Aber für die Zeit der geschichtlichen Entwickelung denkt man, die Menschen haben eben im wesentlichen immer so gedacht, so empfunden, wie sie heute empfinden, höchstens daß sie früher auf einer kindlichen Stufe des wissenschaftlichen Lebens gestanden, und daß sie sich endlich zu dem hindurchgerungen haben, von dem wir heute sagen, wie herrlich weit wir es in der Erkenntnis der Welt gebracht haben. Nun, eine einigermaßen unbefangene Betrachtung des menschlichen Lebens spricht allerdings von dem Gegenteil, und ich mußte Ihnen ja schildern, wie ein gewaltiger Umschwung da war im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert, wie dann der andere Umschwung im ganzen menschlichen Seelenleben da war im Beginn des 15. Jahrhunderts, und wie auch im 19. Jahrhundert eine Wendung im menschlichen Seelenleben sich abgespielt hat.

[ 2 ] Wir wollen heute, ich möchte sagen, eine Art Detail dieser ganzen Entwickelung betrachten. Ich möchte heute zunächst eine Persönlichkeit vor Sie hinstellen, die so recht zeigt, wie Menschen in verhältnismäßig gar nicht weit zurückliegenden Zeitaltern eben anders gedacht haben, als man heute denkt. Die Persönlichkeit, die ja auch in früheren Vorträgen schon erwähnt worden ist, soll sein die des im 9. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert am Hofe Karls des Kahlen in Frankreich lebenden Johannes Scotus Erigena. Johannes Scotus Erigena, der drüben, jenseits des Kanals, seine Heimat hatte, etwa im Jahre 815 geboren ist und bis weit in die zweite Hälfte des 9. Jahrhunderts hinein gelebt hat, er ist eine Persönlichkeit, die eigentlich so recht die intimere christliche Denkweise des 9. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderts darstellt, aber diejenige Denkweise, die noch ganz unter den Nachwirkungen der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte steht. Johannes Scotus Erigena war offenbar durchaus beflissen gewesen, sich zu vertiefen in dasjenige, was die gewöhnliche Gelehrten- und theologische Bildung seiner Zeit war. Beide fielen ja in seiner Zeit zusammen, die Gelehrten- und die theologische Bildung. Und diese Gelehrten- und theologische Bildung konnte man sich ja am besten aneignen drüben, jenseits des Kanals, in den irischen Anstalten namentlich, wo in einer gewissen esoterischen Art das Christentum gepflegt worden ist. Dann haben die Frankenkönige verstanden, solche Persönlichkeiten an ihren Hof zu ziehen, und dasjenige, was an christlicher Bildung dann das Frankenreich durchsetzt hat, vom Frankenreiche ja auch weiter nach Osten gegangen ist in das westliche Deutschland, das ist ja im wesentlichen beeinflußt von denjenigen Persönlichkeiten, die von den Frankenkönigen herübergezogen worden sind von jenseits des Kanals. Johannes Scotus Erigena hat sich aber auch vertieft in alles dasjenige, was namentlich eigen war den griechischen Kirchenvätern, und er hat sich vertieft in diejenigen Schriften, die eine gewisse problematische Natur an sich tragen innerhalb der abendländischen Zivilisation, in die Schriften des Dionysius des Areopagiten. Dieser Dionysius der Areopagite wird ja von einigen für einen unmittelbaren Schüler des Paulus gehalten. Die Schriften tauchen aber erst im 6. Jahrhunderte auf, und manche sprechen daher von pseudo-dionysischen Schriften, die im 6. Jahrhunderte von irgend jemandem abgefaßt worden und dann dem Paulus-Schüler zugeschrieben worden seien.

[ 3 ] Wer so spricht, kennt nicht die ganze Art und Weise, wie sich geistige Erkenntnisse in diesen älteren Jahrhunderten fortgepflanzt haben. Solch eine Schule, wie diejenige war, in der Paulus selbst in Athen gelehrt hatte, sie hatte Erkenntnisse, welche zunächst nur mündlich gelehrt worden sind, welche sich dann von Generation zu Generation fortgepflanzt haben, und welche erst viel, viel später aufgeschrieben worden sind. Das, was da später aufgeschrieben worden ist, braucht deshalb durchaus nicht unecht zu sein, sondern kann mit einer gewissen Identität dasjenige wiedergeben, was Jahrhunderte alt ist. Und einen solchen Wert auf die Persönlichkeit, wie wir heute legen, einen solchen Wert hat man ja in diesen ältesten Zeiten auf die Persönlichkeit nicht gelegt. Und wir werden ja vielleicht gerade heute rühren können an einem Umstand, den wir zu besprechen haben werden bei Johannes Scotus Erigena, warum das der Fall war, warum man auf die Persönlichkeit in der damaligen Zeit wenig Wert gelegt hat.

[ 4 ] Nun aber steht ja eines ohne Zweifel fest: die Lehren, die aufgezeichnet worden sind auf den Namen des Dionysius des Areopagiten hin, die hielt man im 6. Jahrhundert als der Aufzeichnung besonders wert. Man hielt sie für dasjenige, was aus den ersten christlichen Zeiten erhalten war, und was gerade um diese Zeit besonders aufgezeichnet werden mußte. In dieser Tatsache als solcher sollte man etwas Besonderes sehen. Man hatte einfach in den Zeiten vor dem 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert zu dem von Generation zu Generation fortwirkenden Gedächtnis mehr Vertrauen als man in der späteren Zeit hatte. So sehr aufs Niederschreiben war man eben in den älteren Zeiten nicht erpicht. Aber man sah die Zeit herankommen, in der es immer mehr und mehr notwendig wurde, die Dinge, die sich früher mit Leichtigkeit mündlich hatten fortpflanzen lassen, aufzuzeichnen, denn es ist in der Tat etwas Subtiles, was da in den Schriften des Dionysius aufgezeichnet wird. Und dasjenige, was Johannes Scotus Erigena in diesen Schriften hat studieren können, das war ganz gewiß geeignet, auf ihn einen außerordentlich tiefen Eindruck zu machen. Denn ungefähr war die Denkweise, welche man in diesem Dionysius findet, die folgende: Wir Menschen, wir können mit unseren Begriffen, die wir uns bilden, mit den Anschauungen, die wir gewinnen können, die sinnlich-physische Welt überschauen. Wir können dann mit dem Verstande unsere Schlüsse ziehen aus den Tatsachen und Wesenheiten dieser physisch-sinnlichen Welt. Wir entwickeln uns gewissermaßen hinauf zu einem Verstandesinhalte, der dann nicht mehr sinnlich anschaulich ist, der in Vorstellungen, in Begriffen erlebt wird, und wenn wir aus den Sinnestatsachen und Sinneswesen unsere Begriffe, unsere Vorstellungen gebildet haben, dann bekommen wir den Drang, uns mit diesen Vorstellungen zu dem Übersinnlichen, zu dem Geistigen, zu dem Göttlichen hinaufzubewegen.

[ 5 ] Aber nun geht Dionysius nicht in der Weise vor, daß er etwa sagt, wir lernen aus den Sinnesdingen dieses oder jenes, unser Verstand bekommt seine Vorstellungen und er schließt dann auf eine Gottheit, er schließt auf eine geistige Welt -, so sagt er nicht, sondern er sagt: Diejenigen Vorstellungen, die wir bekommen aus den Sinnesdingen, sind alle ungeeignet, die Gottheit auszudrücken. Wir können einfach, wenn wir uns noch so subtile Vorstellungen bilden von den Sinnesdingen, wir können mit Hilfe dieser Vorstellungen nicht dasjenige ausdrücken, was die Wesenheit des Göttlichen ist. Wir müssen daher unsere Zuflucht nehmen von den positiven Vorstellungen zu den negativen Vorstellungen. Wir sprechen zum Beispiel, wenn wir unseren eigenen Mitmenschen begegnen, von Persönlichkeit. Wenn wir von der Gottheit sprechen, so sollten wir nach dieser Anschauung des Dionysius nicht von Persönlichkeit sprechen, weil die Vorstellung der Persönlichkeit viel zu klein, viel zu niedrig ist, um die Gottheit zu bezeichnen. Wir sollten vielmehr sprechen von Überpersönlichkeit. Wir sollten nicht einmal, wenn wit von der Gottheit sprechen, vom Sein sprechen. Wir sagen, ein Mensch ist, ein Tier ist, eine Pflanze ist. Gott sollten wir nicht in demselben Sinne wie dem Menschen, dem Tier, der Pflanze ein Sein zuschreiben, sondern wir sollten ihm ein Übersein zuschreiben. Und so sollten wir versuchen, meint Dionysius, uns allerdings hinaufzuschwingen von der Sinneswelt zu bestimmten Vorstellungen, aber dann sollten wir gewissermaßen diese Vorstellungen überall umkippen, ins Negative übergehen lassen. Wir sollten gewissermaßen uns hinaufschwingen aus der Sinneswelt zur positiven Theologie, dann aber umkippen und die negative Theologie begründen, die eigentlich so hoch ist, so von Gott und dem göttlichen Denken durchdrungen, daß sie sich nur ausspricht in negativen Prädikaten, in Verneinungen desjenigen, was man sich von der Sinneswelt vorstellen kann. |

[ 6 ] Und so glaubte Dionysius der Areopagite hinüberzudringen in die göttlich-geistige Welt, indem er gewissermaßen alles dasjenige, was man im Verstande haben kann, verläßt und sich zu einer überverständigen Welt hinüberlebt.

[ 7 ] Sehen Sie, wenn wir den Dionysius für einen Paulus-Schüler halten, dann lebt er ja am Ende des 1. christlichen Jahrhunderts in das 2. christliche Jahrhundert hinüber und er lebt also ein paar Jahrhunderte vor dem entscheidungsvollen 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert. Er fühlt, was da herankommt: den Höhepunkt menschlicher Verstandesentwickelung. Er sieht gewissermaßen mit einem Teil seines Wesens zurück in die alten Zeiten. Sie wissen, vor dem 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert haben die Menschen noch nicht so vom Verstande geredet, wie seit dem 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert. Der Verstand oder die Verstandesseele ist ja erst im 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert geboren worden, und aus dieser Geburt der Verstandesseele ging die griechische, ging die lateinische Kultur hervor. Die waren dann im 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert auf ihrem Höhepunkt. Vor diesem 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert hat man ja gar nicht die Welt mit dem Verstande erkannt; man hat sie erkannt durch die Anschauung. Die älteren ägyptischen, die älteren chaldäischen Erkenntnisse sind durch die Anschauung gewonnen, sind gewonnen so, wie wir unsere äußeren sinnlichen Erkenntnisse gewinnen, trotzdem diese vorchristlichen Erkenntnisse geistige Erkenntnisse waren. Der Geist wurde eben so angeschaut, wie wir heute das Sinnliche anschauen und wie schon die Griechen das Sinnliche angeschaut haben. Es ist also gewissermaßen in Dionysius dem Areopagiten etwas wie ein Zurücksehnen zu einer Anschauung, die jenseits des Verstandes liegt.

[ 8 ] Nun stand vor dem Dionysius das große Mysterium von Golgatha. Er lebte in der Verstandeskultur seiner Zeit. Wer sich in die Schriften des Dionysius vertieft, der sieht, gleichgültig wer es war, wie stark dieser Mann lebte in alldem, was die Verstandeskultur seiner Zeit hervorgebracht hat. Ein feingebildeter Grieche, aber zu gleicher Zeit ein Mann, der in seiner ganzen Persönlichkeit erfüllt war von der Größe des Mysteriums von Golgatha, und der sich sagte: Wenn wir uns mit unserem Verstande auch noch so sehr anstrengen, an das Mysterium von Golgatha und dasjenige, was dahintersteht, kommen wir nicht heran. Wir müssen über den Verstand hinauskommen. Wir müssen von der positiven Theologie zu der negativen Theologie uns hinüberentwickeln.

[ 9 ] Das machte auf Johannes Scotus Erigena, als er die Schriften dieses Dionysius Areopagita las, noch im 9. Jahrhundert einen großen Eindruck; denn dasjenige, was auf das 4. nachchristliche Jahrhundert folgte, was mehr augustinisch war, das entwickelte sich ja nur langsam weiter in der Art, wie ich das in den vorigen Vorträgen dargestellt habe. Solch ein Geist, gerade einer derjenigen, die sich in den Weisheitsschulen drüben in Irland ausgebildet hatten, lebte noch in den ersten christlichen Jahrhunderten, solch ein Geist konnte noch mit allen Fasern seiner Seele hängen an dem, was in Dionysius dem Areopagiten steht. Und gleichzeitig war doch aber wiederum in Johannes Scotus Erigena der Drang ganz heftig, mit dem Verstande, mit demjenigen, was der Mensch in seinem Intellekt erreichen kann, eine Art positiver Theologie zu begründen, die ihm zu gleicher Zeit Philosophie war, und emsig studierte Scotus Erigena gerade die griechischen Kirchenväter. Wir finden bei ihm eine genaue Kenntnis zum Beispiel des Origenes, der vom 2. ins 3. nachchristliche Jahrhundert herübergelebt hat.

[ 10 ] Wenn wir diesen Origenes studieren, finden wir tatsächlich noch eine ganz andere Anschauung als die christliche, das heißt als diejenige, die dann später als die christliche Anschauung aufgetreten ist. Origenes ist durchaus noch der Meinung, daß man mit Philosophie die Theologie durchdringen müsse, daß man nur studieren könnte den Menschen mit seinem ganzen Wesen, wenn man ihn als einen Ausfluß der Gottheit betrachtet, wenn man ihn so betrachtet, daß er einstmals aus der Gottheit seinen Ursprung genommen hat, sich dann immer weiter und weiter erniedrigt, aber durch das Mysrerium von Golgatha die Möglichkeit empfangen hat, wiederum zu der Gottheit aufzusteigen, um sich dann wiederum mit der Gottheit zu vereinigen. Von Gott in die Welt zu Gott zurück, so etwa kann man den Weg bezeichnen, den Origenes als den seinigen erkannte. Und im Grunde genommen liegt so etwas auch den Dionysischen Schriften zugrunde, und es ging dann über auf solche Persönlichkeiten, von denen Johannes Scotus Erigena eine war. Es gab deren aber viele.

[ 11 ] Man könnte sagen, wie dutch eine Art historischen Wunders ist ja eigentlich die Nachwelt dazu gekommen, die Schriften des Johannes Scotus Erigena zu kennen. Sie erhielten sich, im Gegensatz zu anderen Schriften aus den ersten Jahrhunderten, die ähnlich waren und die ganz verlorengegangen sind, bis ins 11., 12. Jahrhundert, einige wenige noch bis ins 13. Sie waren ja in dieser Zeit vom Papste als ketzerisch erklärt worden, es war der Befehl gegeben worden, daß alle Exemplare aufgesucht und verbrannt werden müßten. Nur viel später in einem verlorenen Kloster hat man Handschriften aus dem 11. und 13. Jahrhundert wieder gefunden. Im 14., 15., 16., 17. Jahrhundert wußte man ja von Johannes Scotus Erigena nichts. Die Schriften waren verbrannt worden wie ähnliche Schriften, welche Ähnliches enthielten aus derselben Zeit, und bei denen man eben vom Standpunkte Roms aus glücklicher war: man hatte alle anderen Exemplare dem Feuer übergeben können! Von Scotus Erigena blieben eben einzelne zurück.

[ 12 ] Wenn wir nun das 9. nachchristliche Jahrhundert bedenken, und wenn wir dazu rechnen, daß in Johannes Scotus Erigena ein genauer Kenner der Weisheiten der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte lebte, dann werden wir uns doch sagen müssen: Das ist ein charakteristischer Repräsentant für dasjenige, was aus der früheren Zeit, aus der Zeit vor dem 4. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert noch herübergeragt hat in spätere Zeiten. In diesen späteren Zeiten ist ja alles verknöchert, möchte man sagen, in der toten lateinischen Sprache. Es hat sich dasjenige, was früher lebendig war als eine Weisheit von der übersinnlichen Welt, verknöchert, dogmatisiert, ist start, verstandesmäßig geworden. Aber in solchen Leuten wie in Scotus Erigena lebte noch etwas von der alten Lebendigkeit des unmittelbaren geistigen Wissens, wie es vorhanden war in den ersten christlichen Zeiten, und wie es verwendet worden war von den erleuchtetsten Geistern, gerade um das Mysterium von Golgatha zu verstehen.

[ 13 ] Diese Weisheit mußte eine Zeitlang aussterben, damit von dem ersten Drittel des 15. Jahrhunderts bis in unsere Zeiten der Verstand des Menschen kultiviert werden konnte. Der Verstand als solcher ist zwar eine geistige Eigenschaft des Menschen, aber er wandte sich zunächst dem Materiellen zu. Das alte Weisheitsgut mußte verschwinden, damit der Verstand in seiner Schattenhaftigkeit geboren werden konnte. Wenn wir uns nicht in schulmäßig-pedantischer Weise in seine Schriften vertiefen, sondern mit dem ganzen Menschen, so merken wir, daß bei Scotus Erigena noch etwas aus anderen seelischen Untergründen heraus redet als diejenigen sind, aus denen heraus später gesprochen worden ist. Da redet gewissermaßen der Mensch noch aus Tiefen heraus, die später nicht mehr erreicht werden konnten von dem seelischen Leben. Alles ist geistiger, und wenn der Mensch überhaupt erkenntnismäßig redete, redete er von Dingen, die sich im Geistigen abspielen.

[ 14 ] Es ist außerordentlich wichtig, einmal genau hinzusehen, wie die Gliederung der Erkenntnis bei Johannes Scotus Erigena war. Er unterscheidet in seiner großen Schrift über die Gliederung der Natur, die eben auf die geschilderte Weise auf die Nachwelt gekommen ist, in vier Kapiteln dasjenige, was er über die Welt zu sagen hat, und er spricht zuerst im ersten Kapitel von der nichtgeschaffenen und schaffenden Welt (siehe Darstellung S. 262). Das ist das erste Kapitel, das schildert in der Art, wie Johannes Scotus Erigena dies glaubt tun zu können, gewissermaßen Gott, wie er war, bevor er herangetreten ist an irgend etwas, das Weltschöpfung ist. Johannes Scotus Erigena schildert da durchaus so, wie er es, ich möchte sagen, gelernt hat durch die Schriften des Dionysius, und er schildert, indem er höchste Verstandesbegriffe ausbildet, aber zu gleicher Zeit sich bewußt ist, mit denen kommt man nur bis zu einer gewissen Grenze, jenseits welcher die negative Theologie liegt. Man nähert sich also nur dem, was eigentlich wahres Wesen des Geistigen, des Göttlichen ist. Wir finden da in diesem Kapitel unter anderem die schöne, für die heutige Zeit noch lehrreiche Abhandlung über die göttliche Trinität. Er sagt, wenn wir die Dinge um uns herum anschauen, so finden wir zuerst als allgeistige Eigenschaft das Sein (siehe $. 262). Dieses Sein ist gewissermaßen das, was alles umfaßt. Wir sollten Gott nicht das Sein, so wie es die Dinge haben, beilegen, aber wir können doch nur gewissermaßen, indem wir hinaufschauen auf das, was Übersein ist, doch nur zusammenfassend vom Sein der Gottheit sprechen. Ebenso finden wir, daß die Dinge in der Welt von Weisheit durchstrahlt und durchsetzt sind. Wir sollten Gott nicht bloß Weisheit, sondern Überweisheit beilegen. Aber eben, wenn wir von den Dingen ausgehen, kommen wir bis zu der Grenze des Weisheitsvollen. Aber es ist nicht nur Weisheit in allen Dingen: Alle Dinge leben; es ist Leben in allen Dingen. Wenn also Johannes Scotus Erigena sich die Welt vergegenwärtigt, so sagt er: Ich sehe in der Welt Sein, Weisheit, Leben. Die Welt erscheint mir gewissermaßen in diesen drei Aspekten als seiende, als weisheitsvolle, als lebendige Welt. Gleichsam sind ihm das drei Schleier, die sich der Verstand ausbildet, wenn er über die Dinge hinblickt. Man müßte durchsehen durch die Schleier, dann würde man in das GöttlichGeistige hineinsehen. Aber er schildert zunächst die Schleier und sagt: Wenn ich auf das Sein sehe, so repräsentiert mir das den Vater; wenn ich auf die Weisheit sehe, so repräsentiert mir das den Sohn im All; wenn ich auf das Leben sehe, so repräsentiert mir das den Heiligen Geist im All.

[ 15 ] Sie sehen, Johannes Scotus Erigena geht durchaus von philosophischen Begriffen aus und erhebt sich zu dem, was die christliche Trinität ist. Er macht also den Weg im Inneren noch durch, vom Begreifen ausgehend, in das sogenannte Unbegreifliche hinein. Das ist auch durchaus seine Überzeugung. Aber er redet eben so, daß man der Art und Weise, wie er die Dinge gibt, ansieht, daß er von Dionysius gelernt hat. Er möchte eigentlich in dem Momente, wo er zu Sein, Weisheit, Leben kommt, und ihm diese repräsentieren Vater, Sohn und Geist, er möchte eigentlich diese Begriffe auseinanderschwimmen lassen in ein allgemeines Geistiges hinein, in das sich der Mensch dann überbegrifflich erheben müßte. Aber er schreibt dem Menschen nicht zu die Fähigkeit, zu solchem Überbegrifflichen zu kommen.

[ 16 ] Damit ist Johannes Scotus Erigena ein Sohn seines Zeitalters, das den Verstand ausbildete, und das ja wirklich, wenn es sich selbst richtig verstand, sich sagen mußte, es könne nicht hineinkommen in das Überbegriffliche.

[ 17 ] Das zweite Kapitel schildert dann gewissermaßen eine zweite . Schichte des Weltendaseins, die geschaffene und schaffende Welt (siehe S. 262). Das ist diejenige Welt der geistigen Wesenheiten, in der wir zu suchen haben Angeloi, Archangeloi, Archai und so weiter. Diese Welt der geistigen Wesenheiten, die wir ja auch bei dem Dionysius dem Areopagiten verzeichnet finden, diese Welt der geistigen Wesenheiten schafft überall in der Welt, aber sie ist selbst geschaffen, sie ist von dem höchsten Wesen angefangen, also geschaffen, und sie schafft in allen Einzelheiten des Daseins, das uns umgibt.

[ 18 ] Als dritte Welt im dritten Kapitel schildert er dann die geschaffene und nichtschaffende Welt. Das ist die Welt, die wir um uns herum mit unseren Sinnen wahrnehmen. Das ist die Welt der Tiere, Pflanzen und Mineralien, der Sterne und so weiter. In diesem Kapitel behandelt er ungefähr alles dasjenige, was wir nennen würden Kosmologie, Anthropologie und so weiter, dasjenige, was wit etwa heute bezeichnen als den Umfang des Wissenschaftlichen.

[ 19 ] In dem vierten Kapitel behandelt er die nichtgeschaffene und nichtschaffende Welt. Es ist wiederum dieses die Gottheit, aber so, wie sie sein wird, wenn alle Wesen, namentlich alle Menschen, zu ihr zurückgekehrt sein werden, wenn sie nicht mehr schaffend sein wird, wenn sie in sich aufgenommen hat in seliger Ruhe - so stellt sich ja Johannes Scotus Erigena das vor - alle diejenigen Wesen, die eben aus ihr hervorgegangen sind.

[ 20 ] Nun, wenn wir diese vier Kapitel überschauen, so haben wir ja darinnen eigentlich, ich möchte sagen, etwas wie ein Kompendium alles Überlieferten, so wie es vorhanden war in den Weisheitsschulen, aus denen Johannes Scotus Erigena hervorgegangen ist. Wenn man dasjenige nimmt, was er schildert in dem ersten Kapitel, so haben wir etwa dasjenige, was man in seinem Sinne die Theologie genannt hat, die Theologie, die eigentliche Lehre von dem Göttlichen.

[ 21 ] Wenn man das zweite Kapitel nimmt, so hat man darinnen dasjenige, was er nennt Idealwelt, etwa in unserer heutigen Sprache, Ideal aber vorgestellt als wesenhaft. Er schildert ja nicht abstrakte Ideen, sondern eben Engel, Erzengel und so weiter, er schildert die ganze intelligible Welt, wie man es nannte, die aber nicht eine intelligible Welt wie die unsre war, sondern die eine Welt von lebendiger Wesenheit war, von lebendigen intelligiblen Wesenheiten.

[ 22 ] In dem dritten Kapitel schildert er, wie gesagt, dasjenige, was wir heute unsere Wissenschaft nennen würden, aber doch anders. Wir haben seit der Galilei-Kopernikus-Zeit, die ja später fällt, nicht mehr dasjenige, was man in der Zeit des Scotus Erigena Kosmologie oder Anthropologie nennt. Was man die Kosmologie nennt ‚ist durchaus noch etwas, das aus dem Geiste heraus beschrieben wird, ist etwas, das so beschrieben wird, daß geistige Wesenheiten die Sterne lenken, daß geistige Wesenheiten auch in den Sternen leben, daß die Elemente Feuer, Wasser, Luft, Erde durchsetzt werden von geistigen Wesenheiten. Also es ist etwas anderes, was da als Kosmologie geschildert wird. Jene materialistische Anschauungsweise, die seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts heraufgekommen ist, die gab es eben dazumal noch nicht, und was er etwa als Anthropologie hat, das ist auch etwas ganz anderes, als was wir heute etwa Anthropologie in unserem materialistischen Zeitalter nennen.

[ 23 ] Da kann ich Ihnen ja etwas sagen, was außerordentlich charakteristisch ist für dasjenige, was bei Johannes Scotus Anthropologie ist. Er sieht den Menschen an und sagt: Der Mensch trägt zunächst das Sein in sich. Er ist also mineralisches Wesen, er hat in sich mineralisches Wesen. Also erstens: der Mensch ist ein mineralisches Wesen (siehe S. 262). Zweitens: der Mensch leibt und lebt wie eine Pflanze. Drittens: der Mensch empfindet als Tier. Viertens: der Mensch urteilt und schließt, macht Schlüsse als Mensch. Fünftens: der Mensch erkennt als Engel.

[ 24 ] Nun, das ist selbstverständlich etwas in unserer Zeit Ungeheuerliches! Wenn Johannes Scotus Erigena von Urteilen, Schließen spricht, was man ja zum Beispiel auch macht in der Gerichtsstube, wenn man über jemanden aburteilen will, dann urteilt und schließt der Mensch als Mensch. Wenn er aber erkennt, wenn er erkennend eindringt in die Welt, dann verhält sich der Mensch nicht als Mensch, sondern als Engel! Ich will das zunächst aus dem Grunde sagen, um Ihnen zu zeigen, daß Anthropologie für diese Zeit noch etwas anderes ist als für die jetzige Zeit, denn, nicht wahr, es würde heute kaum irgendwo, nicht einmal an einer theologischen Fakultät gehört werden können, daß der Mensch erkennt als Engel. So daß man sagen muß: Dasjenige, was Johannes Scotus Erigena im dritten Kapitel schildert, das haben wir als unsere Wissenschaft nicht mehr. Es ist etwas anderes geworden bei uns. Wenn wir es mit einem Worte nennen wollten, das heute auf nichts Betriebenes anwendbar ist, so würden wir etwa sagen müssen: Geistige Lehre vom Weltall und dem Menschen, Pneumatologie.

[ 25 ] Und dann das vierte Kapitel. Dieses vierte Kapitel enthält bei Johannes Scotus Erigena erstens die Lehre von dem Mysterium von Golgatha und die Lehre von dem, was der Mensch als die Zukunft zu erwarten hat, als seinen Hingang in die göttlich-geistige Welt, also dasjenige, was man etwa nach heutigem Gebrauche benennen würde Soteriologie, Soter ist ja der Heiland, der Erlöser, und die Lehre von der Zukunft, Eschatologie. Wir finden da behandelt die Begriffe von Kreuzigung, Auferstehung, von der Ausströmung der göttlichen Gnade, von dem Hingang des Menschen zur göttlich-geistigen Welt und so weiter.

[ 26 ] Eines sollte Ihnen dabei auffallen, und das fällt einem ja wirklich auf, wenn man unbefangen ist, indem man so etwas wie dieses Werk «De divisione naturae» von Johannes Scotus Erigena, von der Gliederung der Natur, aufmerksam liest. Da ist von der Welt geredet durchaus als von etwas, das in geistigen Qualitäten erkannt wird. Man spricht vom Geistigen, indem man die Welt betrachtet. Und was ist nicht darinnen? Man muß ja auch auf das aufmerksam sein, was nicht in einer solchen Universalwissenschaft ist, wie sie da Johannes Scotus Erigena begründen will.

[ 27 ] Sie finden bei Johannes Scotus Erigena ungefähr gar nichts von dem, was wir heute Soziologie nennen, Sozialwissenschaft und dergleichen. Man möchte fast sagen, es sieht so aus, als ob der Johannes Scotus Erigena den Menschen, wie er sich sie dachte, ebensowenig eine Sozialwissenschaft habe geben wollen, wie etwa, wenn irgendeine Tierart, die Löwenart oder die Tigerart, oder irgendeine Vogelart eine Wissenschaft herausgeben würde, sie auch nicht eine Soziologie herausgeben würde. Denn der Löwe würde nicht reden über die Art und Weise, wie er mit anderen Löwen zusammenleben soll, oder wie er zu seiner Nahrung kommen soll und so weiter; das ist ihm instinktmäßig gegeben. Ebensowenig können wir uns eine Soziologie der Spatzen denken. Spatzen könnten gewiß allerlei höchst Interessantes an Weltengeheimnissen von ihrem Gesichtspunkte aus hervorbringen, aber sie würden niemals eine Ökonomie, eine Ökonomielehre hervorbringen, denn das würden die Spatzen für das ganz Selbstverständliche ansehen, daß sie das tun, was ihnen eben ihr Instinkt sagt. Das ist das Eigentümliche: Indem wir bei Johannes Scotus Erigena so etwas noch nicht finden, sind wir uns klar darüber, daß er die menschliche Gesellschaft noch so ansah, als ob sie das Soziale aus ihren Instinkten hervorbrächte. Er weist hin gerade in seiner besonderen Art von Erkenntnis auf dasjenige, was in dem Menschen noch als Instinkt lebte, auf die Triebe, die Impulse des sozialen Zusammenseins. Über diesem sozialen Zusammensein ist dasjenige, was er schildert. Er schildert, wie der Mensch aus dem Göttlichen hervorgegangen ist, welche Wesenheiten über der Sinneswelt liegen. Er schildert dann, wie der Geist die Sinneswelt durchzieht, etwa in einer Art Pneumatologie, er schildert dasjenige, was in die Sinneswelt als Geistiges eingedrungen ist in seinem vierten Kapitel in der Soteriologie, in der Eschatologie. Aber er schildert nirgendwo, wie die Menschen zusammenleben sollen. Ich möchte sagen, alles ist herausgehoben über die Sinneswelt. Das war überhaupt ein Charakteristikum dieser älteren Wissenschaft, daß alles über die Sinneswelt hinausgehoben war.

[ 28 ] Und vertieft man sich im geisteswissenschaftlichen Sinn in so etwas wie die Lehre des Johannes Scotus Erigena, so sieht man, er hat gar nicht mit denjenigen Organen gedacht, mit denen heute die Menschheit denkt. Man versteht ihn eben nicht, wenn man ihn verstehen will mit demjenigen Denken, das heute die Menschheit vollführt. Man versteht ihn nur, wenn man sich durch Geisteswissenschaft eine Anschauung errungen hat von dem, wie man mit dem Ätherleib denkt, mit demjenigen Leib, der als ein feinerer Leib dem groben sinnlichen Leib zugrunde liegt.

[ 29 ] Also Johannes Scotus Erigena hat nicht mit dem Gehirn, sondern mit dem Ätherleib gedacht. Wir haben in ihm einfach einen Geist, der noch nicht mit dem Gehirn gedacht hat. Und alles dasjenige, was er niederschreibt, kommt zustande als Ergebnis des Denkens mit dem Ätherleib. Im Grunde genommen beginnt man erst nach seiner Zeit mit dem physischen Leib zu denken, und so recht eigentlich erst vom 15. Jahrhundert an. Was man gewöhnlich nicht sieht, ist daß sich wirklich das menschliche Leben als Seelenleben in dieser Zeit geändert hat, daß man wirklich, wenn man zurückgeht ins 13., 12., 11. Jahrhundert, auf ein Denken stößt, wie es der Johannes Scotus Erigena hatte, daß man da kommt an ein Denken, das noch nicht mit dem physischen Leib, sondern mit dem Ätherleib vollzogen worden ist. Dieses Denken mit dem Ätherleib, das sollte nicht hereinragen in die spätere Zeit, in der man scholastisch dialektisiert hat über starte Begriffe; da wurde dieses ältere Denken mit dem Ätherleib, das aber durchaus auch das Denken der ersten christlichen Jahrhunderte war, eben verketzert. Deshalb auch die Verbrennung der Schriften des Johannes Scotus Erigena. Und man wird es nun begreifen, wie die Seelenverfassung eines solchen Denkers in der damaligen Zeit eigentlich war

[ 30 ] Wenn wir in ältere Zeiten zurückgehen, so finden wir da bei allen Menschen ein gewisses Hellsehen. Die Menschen dachten überhaupt nicht mit ihrem physischen Leib, sondern sie dachten mit ihrem Ätherleib in älteren Zeiten, und sogar mit ihrem astralischen Leib beziehungsweise führten sie ihr Seelenleben durch. Vom Denken sollten wir da gar nicht reden, da ja der Intellekt, wie gesagt, erst im 8. votchristlichen Jahrhundert entstanden ist. Aber von diesem alten Hellsehen hatten sich Erbstücke erhalten, und gerade bei den hervorragendsten Geistern sucht man durch den Verstand, der jetzt schon geboren ist, einzudringen in dasjenige, was sich heraufvererbt hat durch die Tradition aus älteren Zeiten. Man versuchte zu begreifen, was in ganz anderer Art in älteren Zeiten angeschaut worden war. Man versuchte zu begreifen, aber mußte nun Hilfe haben durch abstrakte Begriffe: Sein, Weisheit, Leben. Man wußte also, möchte ich sagen, noch etwas von einer früheren durchgeistigteren Erkenntnis und fühlte sich schon ganz drinnensteckend in der rein intellektualistischen Erkenntnis.

[ 31 ] Das wurde später gar nicht mehr gefühlt, als die intellektualistische Erkenntnis dann zum Schatten geworden war; aber dazumal fühlten die Menschen: es war in alten Zeiten etwas, was den Menschen aus den höheren Welten lebendig durchlebte, was er nicht bloß dachte. Bei Johannes Scotus ist es so, daß er in diesem Zwiespalt lebt. Er kann bloß denken; aber wenn dieses Denken zum Erkennen wird, da fühlt er, da ist noch etwas da von den alten Mächten, welche den Menschen durchdrungen haben in der alten Art der Erkenntnis. Er fühlt den Engel, den Angelos in sich. Daher sagt er, der Mensch erkenne als Engel. Es war Erbstück aus den alten Zeiten, daß in dieser Zeit der Verstandeserkenntnis ein solcher Geist wie Scotus Erigena noch sagen konnte, der Mensch erkenne wie ein Engel. In den Zeiten der ägyptischen, der chaldäischen Zeit, in den älteren Zeiten der hebräischen Zivilisation würde niemand etwas anderes gesagt haben, als: Der Engel erkennt in mir, und ich nehme Teil als Mensch an der Erkenntnis des Engels. Der Engel wohnt in mir, der erkennt, und ich mache das mit, was der Engel erkennt. Das war in der Zeit, als noch kein Verstand da war. Als dann der Verstand heraufgekommen war, da mußte man das mit dem Verstande durchdringen; aber es war eben in Scotus Erigena noch ein Bewußtsein von diesem Durchdrungensein mit der Angelosnatur.

[ 32 ] Nun geht es einem aber ganz eigentümlich, wenn man sich einläßt in diese Schrift des Scotus Erigena und sie ganz verstehen will. Schließlich bekommt man doch ein Gefühl, man habe etwas sehr Bedeutendes gelesen, etwas gelesen, was noch sehr in geistigen Regionen lebt, was über die Welt als eine geistige Angelegenheit spricht. Aber dann wieder hat man doch das Gefühl: Ja, es geht im Grunde alles durcheinander. Und dann sagt man sich: Wir leben eben mit dieser Schrift schon im 9. nachchristlichen Jahrhunderte; der Verstand hat schon manches in Unordnung gebracht. Und so ist es wirklich. Liest man nämlich das erste Kapitel, so hat man es mit der Theologie zu tun, aber mit einer Theologie, die für Johannes Scotus schon durchaus sekundär ist, der man es ansieht, daß sie auf etwas Größeres, Unmittelbareres zurückweist. Es muß einmal etwas dagewesen sein - ich rede jetzt so, als wenn die Dinge Hypothese wären, aber Geisteswissenschaft kann dann das, was ich jetzt in der Hypothese entwickele, durchaus als Tatsache konstatieren -, man sieht gewissermaßen auf etwas zurück, wo diese Theologie noch nicht so verstandesmäßig angesprochen wurde, wo sie angesprochen wurde als etwas, in das man sich hineingelebt hat. Und von solcher Theologie haben ohne Zweifel jene Ägypter gesprochen, von denen jene Griechen, die ich angeführt habe, berichteten, daß ägyptische Weise zu ihnen gesagt hätten: Ihr Griechen seid ja wie die Kinder, ihr habt kein Wissen von dem Weltenursprung; wir haben dieses heilige Wissen von dem Weltenursprung. — Da wurden die Griechen offenbar auf eine alte lebendige Theologie hingewiesen. Und so muß man sagen: In dem, was wir immer genannt haben die dritte nachatlantische Zeit, die ja im 4. vorchristlichen Jahrtausend beginnt und im 1. vorchristlichen Jahrtausend endet, im 8. vorchristlichen Jahrhundert, im Jahre 747 approximativ endet, in dieser Zeit gab es eine lebendige Theologie, die jetzt mit dem Verstande von Scotus Erigena durchschaut werden will. Viel lebendiger stand sie offenbar noch vor derjenigen Persönlichkeit, die als Dionysius der Areopagite anzuerkennen ist und viel intensiver noch fühlte dieser Dionysius gegenüber dieser alten Theologie. Er fühlte, da ist etwas, was da war, dem man sich nicht mehr nähern kann, das negativ wird, indem man sich ihm nähern will. Wir können nur, so meinte er, vom Verstande aus zur positiven Theologie kommen. Aber er meinte eigentlich mit der negativen Theologie eine alte, die entschwunden ist.