The Human Being as a Physical and Spiritual Entity

GA 205

8 July 1921, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Eighth Lecture

Today, in preparation for the next two reflections, we want to call to mind something about the nature of the human being, insofar as the human being is a being of thought. It is precisely this characteristic of the human being, that he is a being of thought, that is scientifically unrecognized today, interpreted in a completely wrong way. It is thought that thoughts, as they are experienced by the human being, come about in the human being, that the human being is, so to speak, the bearer of thoughts. No wonder this view is held, for the human being's essential being is only accessible to a finer observation. Precisely this human essence withdraws from coarser observation.

If we regard the human being as a being of thought, it is because we perceive, in the waking state, from waking to sleeping, that he accompanies his other experiences with thoughts, with the content of his thinking. These thought experiences seem to arise somehow from within the person and to cease to some extent during the period between falling asleep and waking up, that is, during sleep. And because one is of the opinion that thought experiences are there for a person as long as he is awake, but get lost in sleep in some kind of vagueness, about which one does not try to get further clarification and one just imagines the matter, one cannot actually enlighten oneself about the human being as a thinking being. A more delicate observation, which does not yet advance very far into the region I have described in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds,” shows that the life of thought is not at all as simple as one usually imagines it to be. We need only compare this ordinary thought life, the coarse thought life, of which everyone becomes aware when observing a person between waking and sleeping, with an element that is indeed problematic for ordinary consciousness, namely the element of dreaming.

Usually, when we talk about dreams, we do not really get involved in anything other than a general characteristic of dreaming. One compares the state of dreaming with the state of waking thought and finds that in dreaming, arbitrary associations of thoughts are present, as one would say, that images string together without such a connection being perceptible in this stringing together as it is perceptible in the external world of being. Or else one relates what takes place in the dream to the external sense world, sees how it stands out, as it were, how it does not fit into the processes of the external sense world after beginning and end.

Of course, one does advance to these observations, and in relation to these observations, beautiful results can certainly be seen. But what is not noticed is that, firstly, when a person abandons themselves a little, I would say with a touch of contemplation, lets themselves go a little and lets their thoughts run free, they can then perceive how something is mixed into this ordinary train of thought, which follows on from the external course of events, that is not unlike dreaming, even when we are awake. One could say that from the moment we wake until we fall asleep, while we are making an effort to adapt our thoughts to the external circumstances in which we are immersed, there is a kind of vague dreaming. It can seem to us, in a sense, like two currents that are there: the upper current, which we control with our arbitrariness, and a lower current, which actually runs much as dreams themselves run in their succession of images. Of course, you have to give yourself a little to your inner life if you want to notice what I am talking about right now. But it is always there. You will always notice: there is an undercurrent. Thoughts swirl around in just as pictorial a way as they do in dreams, where the most colorful things line up next to each other. Memories arise from all sorts of things, and just as in dreams mere similarity of sound may call other thoughts and connect them with them. And people who let themselves go inwardly, people who are too indolent to adapt themselves to outer conditions with their train of thought, they may notice how there is an inner striving to give themselves up to such waking dreams.

These waking dreams differ from ordinary dreams only in that the images are more faded, more like mental images. But in terms of the mutual relationship of these images, waking dreams do not differ particularly from so-called real dreams. There are, of course, all degrees of people, from those who do not even notice that such waking dreams are present in the undercurrents of their consciousness, who thus let their thoughts run entirely along the lines of external events, to those who indulge in waking dreams and let them run in their consciousness, as, I might say, the thoughts there want to interweave and intertwine. There are, after all, all degrees of human nature, from those of a dreamy nature, as they are also called, to those who are very dry natures, who accept nothing but what exactly matches some factual course of events. And we must say that a large part of what inspires people artistically, poetically, and so on, comes from this undercurrent of waking dreams during the day.

That is one side of the matter. It should certainly be taken into account. Then we would know that a surging dreaming is actually constantly taking place within us, which we only tame through our contact with the outside world. And then we would also know that it is essentially the will that adapts to the outside world and brings system, coherence, and logic into the otherwise randomly flowing inner mass of thoughts. It is the will that brings logic into our thinking. But as I said, that is only one side of it.

The other side of the matter is this: here too one can notice, observe – as soon as one only enters a little into those regions which I have described in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds” – how, when one wakes up, one takes something with one from the state in which we were from falling asleep to waking up. And if you add just a little to what you can perceive, you will be able to see very clearly how you wake up, as it were, from a sea of thoughts when you wake up. You do not wake up from a vague, dark state, but rather from a sea of thoughts, thoughts that seem to have been very, very distinct while you were asleep, but you cannot hold on to them when you transition into the waking state.

And if you continue such observations, you will be able to notice that these thoughts, which you bring with you, as it were, from the state of sleep, are very similar to the ideas, the inventions that we have in relation to something we are supposed to do in the outer world, that even these thoughts, which we bring with us when we wake up, are very similar to the moral intuitions, as I have called them in my “Philosophy of Freedom”.

While in the former kind of thought weaving, which to a certain extent runs as an undercurrent of our clear consciousness, we always have the feeling that we are standing face to face with our waking dreams, that something is seething and bubbling within us, we cannot say that about the latter. Rather, we have to say to ourselves about the latter: when we return to our body and to the use of our body when we wake up, we are no longer able to hold on to what we have lived in thought from falling asleep to waking up.

Whoever truly realizes these two sides of human life will cease to regard thought as something that is, as it were, produced in the human organism. For what I characterized last, in particular, what we distinguish ourselves from when we wake up, we cannot directly see as some product of the human organism as such, but we can only see it as something that we experience between falling asleep and waking up, when we are torn out of our body with our ego and our astral body.

Where are we then? This is the first question we must ask ourselves. We are outside our physical and etheric bodies with our ego and our astral body. A simple consideration, which one cannot escape from if one simply devotes oneself to life without prejudice, must tell us: in that which appears to us when we direct our senses to the external world, as the sensory veil of the world, as everything that sensory qualities present to us, in that we are when we are outside ourselves. Only then, in ordinary life, does consciousness fade away. And we feel why consciousness fades when we wake up from this state in the morning. We then feel weak in our body, too weak to hold on to what we have experienced from falling asleep to waking up. Our ego and our astral body cannot hold on to what they have experienced by immersing themselves in the physical and etheric bodies. And by then participating in the experiences that are made through the body, what is experienced from falling asleep to waking up is erased for them. And as I said, only when we have ideas that relate to the external world, or when we have moral intuitions, do we experience something like what must appear to us in an immediate contemplation of what we live in between falling asleep and waking up.

If we look at it this way, we see a very clear contrast between our inner and outer world. In a sense, this also sheds light on the statement we often make that the outer world, as it presents itself to us from waking to sleeping, is a kind of delusion, a kind of maya. For in this world, which shows its outside to us, we are in it when we are not in our body, but when we are outside our body. Then we dive into the world that we otherwise perceive only through our sense revelation. So that we have to say to ourselves: This world, which we perceive through our sense revelation, has subsoils, subsoils that actually contain its causes, its essences. And in our ordinary consciousness we are too weak to perceive these causes and these essences directly.

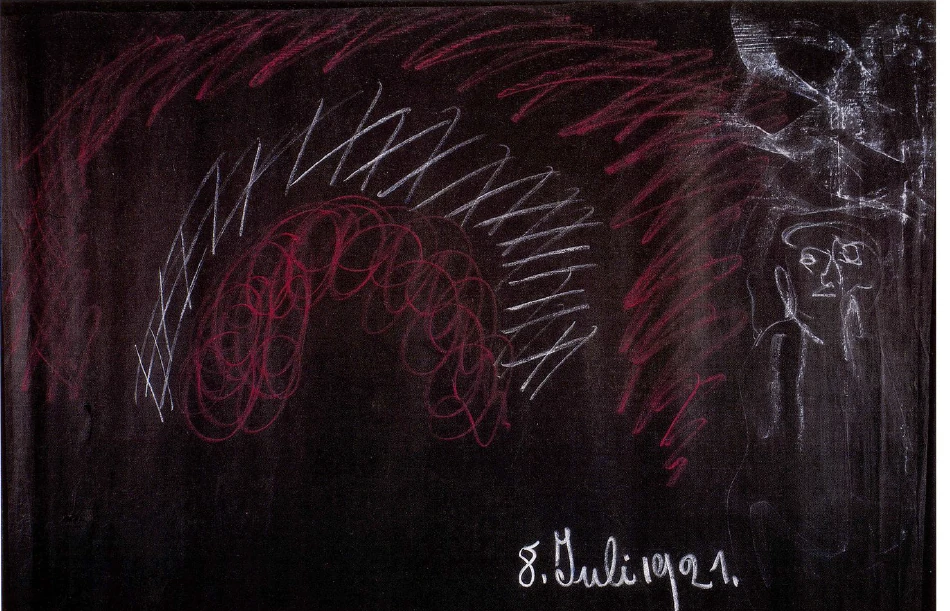

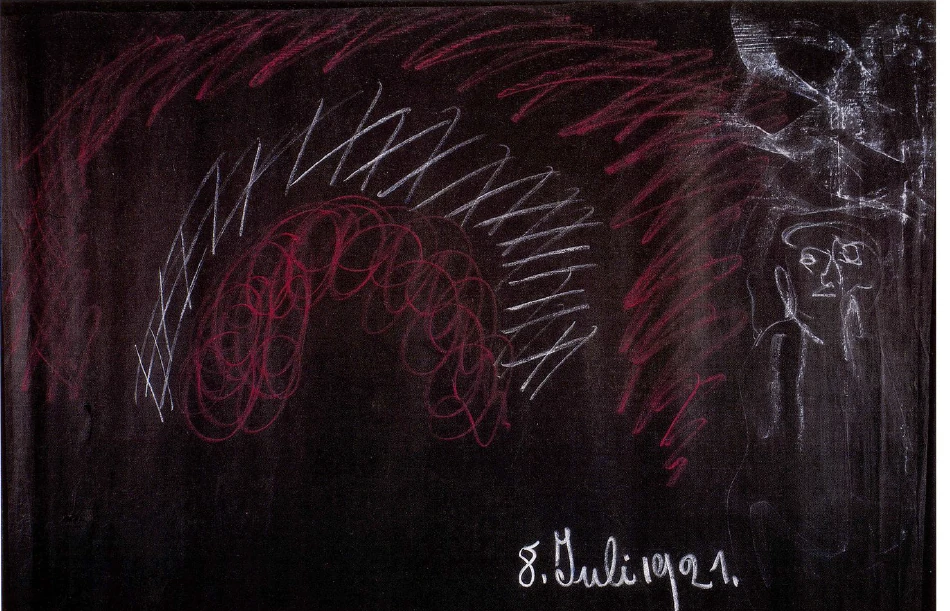

Nevertheless, even unprejudiced observation yields something that reaches far into the regions described in “How to Know Higher Worlds”; unprejudiced observation already yields that which I can schematically present in the following way. If I want to depict the ordinary life of thought, then I do so by having it embrace everything that a person experiences inwardly and mentally from waking up to falling asleep, whether in terms of external perceptions or in terms of physical pain, physical feelings of pleasure, and so on. What is experienced in the mind during ordinary consciousness, I would like to represent schematically as follows (see drawing, white). Below this, like a waking dream, weaves and lives, not subject to the laws of logic, what I first depicted (red below). On the other hand, when we pass into the external world between falling asleep and waking up, we live, as we can perceive in reminiscence after waking up, again in a world of thought, but of thoughts that absorb us, that are not in us, from which we emerge when we wake up (red outside). So that, as it were, we have separated two worlds of thought from each other through our ordinary thinking: an inner world of thought and an outer world of thought, a world of thought that fills the cosmos that receives us when we fall asleep. We can call the latter world of thought the cosmic world of thought. The former is just any world of thought; we will discuss it in more detail in the course of these days.

Thus we see ourselves, as it were, with our ordinary world of thoughts placed in a general world of thoughts, which is kept apart as if by a boundary, and of which one part is in us and one part is outside us. That which is in us appears to us very clearly as a kind of dream. There always rests at the bottom of our soul a chaotic web of thoughts, we can say, something that is not permeated by logic. But this outer world of thoughts, yes, it cannot be perceived by the ordinary consciousness. So only the real spiritual vision can reveal the nature of this outer world of thoughts from direct observation, from direct experience, and then it enters even more deeply into the regions described in “How to Know Higher Worlds”. But then it also turns out that this world of thoughts, into which we plunge between falling asleep and waking up, is a world of thoughts that is not only as logical as our ordinary world of thoughts is logical, but that contains a much higher logic. If one does not want to misunderstand the expression, I would like to call this world of thoughts a super-logical world of thoughts. I would say that it is just as far above ordinary logic as our dream world, our waking dream world, is below logic.

As I said, this can only be fathomed through spiritual vision. But there is another way by which you can check this spiritual vision on this point. It is clear to you, however, that ordinary consciousness cannot penetrate into certain regions of one's own organism. I have spoken about this a great deal in recent lectures. I have said that in the fact that we have our memory, our ability to remember, for ordinary consciousness, we have, as it were, a skin drawn inwardly towards our inner organs. We cannot observe directly through inner vision what the inner organs are, lungs, liver and so on. But I also said: It is a false mysticism, a nebulous mysticism, which only fantasizes about the inner being and speaks in the manner of Saint Therese or Mechthild of Magdeburg, who find all sorts of beautiful poetic images (the beauty of which should not be denied), but which are nothing more than organic effusions. If instead of devoting oneself to this nebulous mysticism, one really studies the human mind, then, when one penetrates to the inner being of man, one comes to an understanding of the organs. One sees spiritually the significance of the lungs, liver, kidneys, etc., one pierces spiritually the memory membrane and comes to an inner insight into man. But this is something that cannot be achieved with ordinary consciousness. With ordinary consciousness, it is only possible to observe externally through anatomy how the organs look when they are viewed as belonging to the ordinary physical and mineral world. But to look inwardly and see what permeates them, what is active in them, what I have described to you in recent days, requires a truly developed spiritual vision.

So there is something in man that he cannot reach with ordinary consciousness. Why can he not reach it with ordinary consciousness? Because it does not belong to him alone. What can be reached with the ordinary consciousness belongs to the human being alone. That which pulsates down there in the organs does not belong to the human being alone, it belongs to the human being as a world being, it belongs to the human being and at the same time to the world.

Perhaps it will become most clear to us through the following discussion. If we look at the human being schematically and have any organ, lung or liver in him, we have forces in such an organ. These forces are not merely inner human forces, these forces are world forces. And when everything that is the external physical world and appears to us as the physical world, when all this has once disappeared with the end of the earth, what now exists as the inner forces of our organs will continue to work. One might be tempted to say that everything our eyes can see and our ears can hear, the whole external world, will fade away with the end of the earth. What covers our skin, what we carry within us, what is enclosed by our organization, is what spiritually contains that which will continue to exist when the external world that our senses see will no longer be there. In essence, something works within the human skin that lives beyond the earth; within the human skin lie the centers, the forces of that which works beyond earthly existence. We do not stand as human beings in the world merely to enclose our organs for ourselves; we stand in the world as human beings so that the cosmos itself is formed within our skin. In that which our ordinary consciousness does not reach, we enclose something that does not merely belong to us, that belongs to the world. Is what belongs to the world built out of the chaotic processes of waking dreaming?

We need only look at these chaotic processes of waking dreaming and you will say to yourself: the whole structure, everything that you perceive as a kind of undercurrent of your consciousness, is most certainly not the builder of your organs, of your entire organism. The organism would look beautiful if everything that lives chaotically in your subconscious were to build your organs, your whole organism! You would see what strange caricatures you would be if you were a reflection of what pulsates in your subconscious. No, just as the outer world, which reveals itself to us through the senses, so to speak on the surface that it presents to us, is constructed from the thoughts that we experience between falling asleep and waking up, so we ourselves are constructed from the same outer powers of thought, within our ordinary consciousness, in what we do not reach within ourselves. If I want to fully represent what a human being is, then I would have to draw it schematically like this. I would have to say: There is the surrounding world of thought (red). This surrounding world of thought also builds up the human organism, and this human organism produces, as it were, flooding over it, the higher world of thought (white), which inclines towards the sensual outer Maya between our thoughts and the surrounding world (blue).

Try to visualize how only a small part of yourself is actually aware of what you are encompassing with your consciousness, and how a large part of yourself is constructed from the same external world into which you submerge yourself between falling asleep and waking up. But this can also be seen from another point of view when you look at a person impartially, and I have already pointed out this point of view here on several occasions.

Man, in his ordinary consciousness, actually encompasses only his thoughts; his feelings are already like dreams floating among thoughts. Feelings arise and subside. Man does not see through them with the clarity with which he sees through his thoughts, his ideas. But the experience between falling asleep and waking up is quite different from the experience of what is willed in us during the day. And what does a person know – as I have often told you – of what happens when he moves his hand or arm through the will! He knows all of this conceptually; first he knows: I want to move my arm. That is a concept. Then he knows what it looks like in his form when he has moved his arm: again, an idea. What he knows of it in his ordinary consciousness is a fabric of ideas; feelings surge beneath this fabric of ideas. But what works in him as will sleeps just as deeply during waking as our whole being sleeps from falling asleep to waking.

What sleeps there? That which sleeps down there, which is built into us from the outer cosmos, is just as much asleep as the minerals and plants are asleep for us outside. That is to say, we do not penetrate into them from the outside, do not look down into what is cosmic for us. We weave and live in this cosmic from falling asleep to waking up. And to the same extent that we see through the outer world, we live ourselves into our own organization. To the same extent that we stop having mere reminiscences, as we peel them from life's events, we get ideas of forces that constitute and build up our organs — the lungs, liver, stomach, and so on. To the same extent that we learn to see through the outer world, we learn to see through our piece of cosmos, which we have incorporated, in which we are, which is in our skin, without us knowing anything about it in our ordinary consciousness.

What do we take with us from this cosmos when we wake up in the morning? The thing that we take with us is very clearly experienced by the unbiased observer as will. And basically, the difference between the life of waking thought and that which flows dreamily in the subconscious is nothing other than that the former is permeated by the will. It is the will that introduces logic, and logic is basically not actually a doctrine of thinking, but a doctrine of how the will orders and tames thought images and brings them into a certain external order, which then corresponds to the external course of the world.

When we wake up with a dream, we perceive particularly strongly this surge down there of chaotic, illogical swirls of images, and we can notice how we plunge our will into this chaotic swirling of images, and our will then orders what lives in us in such a way that it is logically ordered. But we do not take with us the world logic, what I just called super-logic, we only take the will with us.

How is it that this will now works logically in us? You see, here lies an important human mystery, something extraordinarily significant. It is this: when we delve into our cosmic existence, which is not present in ordinary consciousness, when we delve into our whole organization, then we feel in our will, which is spreading there, the cosmic logic of our organs. We feel the cosmic logic of our organs.

It is extremely important to realize that when we wake up in the morning and plunge into our body, we are forced by this immersion to form our will in a certain way. If our body were not already formed in a certain way, the will would swirl like a jellyfish in all directions when we wake up; the will could strive chaotically in all directions like a jellyfish when we wake up. It does not do that because it is immersed in the existing human form. There it submerges, takes on all these forms; this gives it a logical structure. This is why he gives logic to the otherwise chaotically swirling thoughts within the human body. At night, when man sleeps, he is incorporated into the super-logic of the cosmos. He cannot hold on to it. But when he submerges into the body, the will takes on the form of the body. Just as when you pour water into a vessel and the water takes on the shape of the vessel, so the will takes on the form of the body. But it is not just that the will takes on the spatial forms, like when you pour water into a vessel and the water takes on the whole shape of the vessel. Rather, it flows into the smallest veins everywhere. That cannot move, at most, according to Professor Traub, tables and chairs in the room move by themselves, but that is theological university logic, otherwise such a device does not move – the water takes on the resting form and only touches the outer walls. But in the case of humans, this will is completely integrated into all the individual branches and from there it then dominates the otherwise chaotic sequence of images. What one perceives as an undercurrent is, I would say, released from the body. It is truly released from the body, it is something that is connected to the human body, but which actually constantly strives to free itself from the human body, which constantly wants to get out of the forms of this human body. But what the human being carries out of the body when falling asleep, what he carries into the cosmos, what then submerges, that submits to the law of the body.

Now it is the case that with all the organization, which is the human head organization, the human being would only come to images. It is a general physiological prejudice that we also reason and draw conclusions with our heads. No, we merely imagine with our heads. If we only had a head and the rest of the body were inactive for our imaginative life, then we would be waking dreamers. The head has only the ability to dream while awake. And when we return from the head to the body in the morning, passing through the will, the dreams come to our consciousness. Only when we penetrate deeper into our body, when the will adapts not only to the head but also to the rest of the organization, only then is this will again able to bring logic into the otherwise pictorially intertwined powers of images.

This will lead you to something that I have already mentioned in previous lectures. It must be clear to you that man visualizes with his head and that he judges, as strange and paradoxical as it may sound, with his legs and also with his hands, and then again concludes with his legs and hands. This is how we arrive at what we call a conclusion, a judgment. When we imagine, it is only the image that is reflected back into our heads; we are judging and concluding as a whole person, not just as a head person. Of course, it does not occur to us that if a person is mutilated, they cannot or should not judge and conclude, because it depends on how things are arranged

in such people who, as it were, happen to lack one or other limb. We must learn to relate what the human being is spiritually and soulfully to the whole human being, to realize that we bring logic into our imaginative life from the same regions that we do not even reach with ordinary consciousness, which are occupied by the being of feeling and the being of will. Our judgments and conclusions arise from the same sleeping regions of our own inner being, from which our feelings and our will resound.

The most cosmic region in us is the mathematical region. The mathematical region belongs to us not only as a resting human being, but as a walking human being. We always move somehow in mathematical figures. When we look at a walking person from the outside, we see something spatial; when we experience it internally, we experience the mathematics within us, which is cosmic, only that the cosmic also builds us up. The spatial directions that we have outside also build us up and we experience them within us. And by experiencing them, we abstract them, take the images that are mirrored in the brain and interweave them with what is shown to us externally in the world.

It is important to note today that what man puts into the world in the form of mathematics is actually the same thing that builds him up, that is, what is cosmic in nature. For through nonsensical Kantianism, space has been made merely a subjective form. It is not a subjective form; it is something that we experience in the same region as the will. And there it shines forth. There the shining forth becomes something with which we then penetrate that which presents itself externally.

Today's world is still far from being able to study this inner interweaving of the human being with the cosmos, this standing within the cosmos. I have drawn attention to this relationship in a striking way in my Philosophy of Freedom, where you will find remarkable passages in which I show that, in our ordinary consciousness, human beings are connected with the whole cosmos, that they are a part of the whole cosmos, and that, as it were, the individual human element blossoms out of this general cosmic element, which is then embraced by ordinary consciousness. This passage in particular of my “Philosophy of Freedom” has been understood by very few people; most have not known what it is about. It is no wonder that in an age in which abstraction flourishes to the point of being taken for granted, in an age in which this view, which is admittedly extremely ingenious in itself but absolutely abstract, is presented to the world as something special, that which seeks to introduce reality, true reality, is not understood.

It must be emphasized again and again: it is not enough for something to be logical. Einsteinism is logical, but it is not in touch with reality. All relativism is not in touch with reality as such. Thinking in touch with reality begins only where one can no longer leave reality by thinking. Isn't it true that today man reads, or listens, I should say, quite calmly, when Einstein says, as an example: What would happen if a clock were to fly out into the cosmos at the speed of light? Yes, a person today listens to that quite calmly. A clock flying out into the cosmos at the speed of light is, for someone who lives in reality in his thinking, lives in reality in his soul, roughly the same as if someone were to say: What happens to a person when I cut off his head, and in addition, his right hand and his left hand, or his right arm and so on? He simply ceases to be a human being. In the same way, what one is still justified in imagining when one talks about a clock flying out into the cosmos at the speed of light immediately ceases to be a clock! It is not possible to imagine that. If one wants to arrive at valid thinking, the reality must be adhered to. Something can be logical and ingenious to an enormous degree, but it does not necessarily follow that it is in accordance with reality. And it is thinking in accordance with reality that we need in this age. For abstract thinking ultimately really leads us to no longer seeing reality at all because of all the abstractions. And today humanity admires the abstractions that are presented to it in this way. It does not matter whether these abstractions are somehow logically substantiated or the like. What matters is that man learns to grow together with reality, so that he can no longer say anything other than what is actually spoken from reality.

But such conceptions about the human being, as I have presented to you today, provide a kind of guide to realistic thinking. They are often ridiculed today by those who have been trained in our abstract thinking. For three to four centuries, Western humanity has been trained through mere abstraction. But we live in the age in which a reversal in this direction must take place, in which we must find our way back to reality. People have become materialistic, not because they have lost logic, but because they have lost reality. Materialism is logical, spiritualism is logical, monism is logical, dualism is logical, everything is logical, as long as it is not based on real errors in reasoning. But just because something is logical does not mean that it corresponds to reality. Reality can only be found if we bring our thinking more and more into that region of which I said: in pure thinking, one has the world event at one corner. This is in my epistemological writings, and this is what must be gained as the basis for an understanding of the world.

In the moment when one still has thinking, despite having no sensory perception, in that moment one has thinking as will at the same time. There is no longer any difference between willing and thinking. For thinking is a willing and willing is then a thinking. When thinking has become completely free of sensuality, then one has a glimpse of world events. And that is what one must strive for above all: to get the concept of this pure thinking. We will continue our discussion from this point tomorrow.

Achter Vortrag

Wir wollen heute zur Vorbereitung für die beiden nächsten Betrachtungen uns vor die Seele rufen einiges über das Wesen des Menschen, insofern der Mensch ein Gedankenwesen ist. Gerade diese Eigenschaft des Menschen, daß er ein Gedankenwesen ist, die wird ja wissenschaftlich heute verkannt, in einer ganz falschen Weise gedeutet. Man denkt, Gedanken, wie sie der Mensch erlebt, kommen in dem Menschen zustande, der Mensch sei gewissermaßen der Träger der Gedanken. Kein Wunder, daß man diese Anschauung hat, denn eigentlich ist ja die Wesenheit des Menschen nur einer feineren Beobachtung zugänglich. Der gröberen Beobachtung entzieht sich gerade diese Menschenwesenheit.

Wenn wir den Menschen als Gedankenwesen betrachten, so geschieht es ja deshalb, weil wir im Wachzustande, vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen, wahrnehmen, daß er seine sonstigen Erlebnisse mit Gedanken, mit dem Inhalt seines Denkens begleitet. Diese Gedankenerlebnisse kommen einem so vor, als ob sie auf irgendeine Weise im Inneren des Menschen entstehen und als ob sie in einer gewissen Weise für die Zeit zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, also für den Schlafzustand, aufhören würden. Und weil man der Meinung ist, Gedankenerlebnisse seien für den Menschen eben da, so lange er wacht, verlieren sich aber im Schlafe in irgendein Unbestimmtes, über das man sich nicht weiter Aufklärung zu verschaffen versucht und man sich die Sache eben so vorstellt, so kann man eigentlich über den Menschen als Gedankenwesen sich nicht aufklären. Eine feinere Beobachtung, die ja noch gar nicht besonders stark vorrückt bis in diejenige Region, die ich gezeichnet habe in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», zeigt, daß das Gedankenleben durchaus nicht jenes Einfache ist, als das man es sich gewöhnlich vorstellt. Wir brauchen nur dieses gewöhnliche Gedankenleben, das grobe Gedankenleben, dessen jeder gewahr wird, der eben den Menschen zwischen Aufwachen und Einschlafen betrachtet, zunächst zu vergleichen mit einem für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein allerdings problematischen Element, mit dem Element des Träumens.

Gewöhnlich läßt man sich doch eigentlich nicht auf etwas anderes ein, wenn von Träumen die Rede ist, als auf eine allgemeine Charakteristik des Träumens. Man vergleicht den Zustand des Träumens mit dem Zustand des wachen Denkens und findet, daß im Träumen willkürliche Gedankenverbindungen, wie man etwa sagen würde, vorhanden sind, daß Bilder sich aneinanderreihen, ohne daß in dieser Aneinanderreihung ein solcher Zusammenhang wahrnehmbar wäre, wie er wahrnehmbar ist in der äußeren Seinswelt. Oder auch man bezieht dann dasjenige, was im Traum abläuft, auf die äußere Sinneswelt, sieht, wie es gewissermaßen herausragt, wie es nach Anfang und Ende sich nicht eingliedert in die Vorgänge der äußeren Sinneswelt.

Gewiß, bis zu diesen Beobachtungen dringt man ja vor, und in bezug auf diese Beobachtungen sind ja durchaus schöne Resultate zu verzeichnen. Aber was man nicht bemerkt, das ist, daß erstens, wenn der Mensch sich ein wenig, ich möchte sagen, einem Anflug der Versenkung überläßt, ein wenig sich gehen läßt und die Gedanken frei laufen läßt, er dann wahrnehmen kann, wie in diesen gewöhnlichen Gedankenablauf, der sich anschließt an den äußeren Verlauf der Ereignisse, sich etwas doch hineinmischt, was dem Träumen nicht unähnlich ist, auch dann, wenn wir im wachen Zustande sind. Man kann schon sagen: Vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen verläuft gewissermaßen — während wir uns anstrengen, unser Gedankenleben den äußeren Verhältnissen, in die wir hineinverwoben sind, anzupassen — ein unbestimmtes Träumen. Gewissermaßen wie zwei Ströme, die da sind, kann es uns vorkommen: die obere Strömung, die wir beherrschen mit unserer Willkür, und eine untere Strömung, die eigentlich wirklich so verläuft, wie die Träume selbst in ihrer Bilderaufeinanderfolge verlaufen. Gewiß, man muß sich ein bißchen dem inneren Leben hingeben, wenn man das bemerken will, wovon ich eben jetzt spreche. Aber es ist immer vorhanden. Man wird immer bemerken: eine Unterströmung ist da. Da wirbeln die Gedanken durchaus so bildhaft ineinander, wie sie in den Träumen durcheinanderwirbeln, da reiht sich das Bunteste aneinander. Da kommen Reminiszenzen aus allem möglichen, die ebenso wie der Traum nach dem bloßen Wortgleichklang andere Gedanken an sich heranrufen, sich mit ihnen verbinden. Und Menschen, welche sich innerlich gehen lassen, Menschen, welche zu bequem sind, um sich den äußeren Verhältnissen mit ihrem Gedankenablauf anzupassen, die können bemerken, wie ein inneres Streben besteht, sich hinzugeben solchen wachen Träumen.

Dieses wache Träumen unterscheidet sich von dem gewöhnlichen Träumen nur dadurch, daß die Bilder verblaßter sind, daß die Bilder mehr vorstellungsähnlich sind. Aber in bezug auf das gegenseitige Verhältnis dieser Bilder unterscheidet sich dieses Wachträumen gar nicht besonders von dem sogenannten wirklichen Träumen. Es gibt ja alle Grade von Menschen, von jenen an, die überhaupt gar nicht bemerken, daß ein solches waches Träumen in den Unterströmungen ihres Bewußtseins vorhanden ist, die also ganz am Leitfaden der äußeren Ereignisse ihre Gedanken ablaufen lassen, bis zu denen, die sich dem wachen Träumen hingeben und in ihrem Bewußtsein ablaufen lassen, wie, ich möchte sagen, die Gedanken daselbst sich ineinander verweben und verstrudeln wollen. Von solchen träumerischen Naturen, wie man sie auch nennt, bis zu denen, die ganz trockene Naturen sind, die nichts gelten lassen als das, was genau übereinstimmt mit irgendeinem Tatsachenverlauf, gibt es ja alle Grade von menschlichen Naturen. Und wir müssen sagen, ein größerer Teil dessen, was die Menschen künstlerisch, dichterisch und so weiter befruchtet, entstammt dieser Unterströmung des wachen Träumens während des Tages.

Das ist die eine Seite der Sache. Man sollte sie durchaus berücksichtigen. Man würde dann wissen, daß eigentlich in uns fortwährend ein wogendes Träumen stattfindet, das wir nur bändigen durch unseren Verkehr mit der Außenwelt. Und man würde dann auch wissen, daß es im wesentlichen der Wille ist, der sich an die Außenwelt anpaßt, und der in die sonst regellos verlaufende innereGedankenmasse System, Zusammenhang, Logik hineinbringt. Der Wille ist es, der in unser Denken Logik hineinbringt. Aber wie gesagt, das ist nur die eine Seite.

Die andere Seite der Sache ist diese: Auch da kann man wiederum bemerken, beobachten - kaum daß man nur etwas hineinkommt in diejenigen Regionen, die ich in meinem Buche »Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» beschrieben habe -, wie man, wenn man aufwacht, etwas mitnimmt aus dem Zustande heraus, in dem wir vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen waren. Und wenn man nur einiges hinzufügt zu dem, was man da wahrnehmen kann, dann wird man sehr deutlich bemerken können, wie man gleichsam aus einem Meere von Gedanken aufwacht, wenn man eben aufwacht. Man wacht durchaus nicht aus dem Unbestimmten, aus der Finsternis gewissermaßen auf, sondern man wacht eigentlich aus einem Meere von Gedanken auf, von Gedanken, die allerdings den Eindruck machen: sie waren sehr, sehr bestimmt, während man geschlafen hat, aber man kann sie nicht festhalten, wenn man in den Wachzustand übergeht.

Und wenn man solche Beobachtungen fortsetzt, wird man bemerken können, daß diese Gedanken, die man gewissermaßen mitbringt aus dem Schlafzustand, sehr ähnlich sind den Einfällen, den Erfindungen, die wir haben in bezug auf irgend etwas, das wir in der äußeren Welt verrichten sollen, daß sogar diese Gedanken, die wir so mitbringen beim Aufwachen, sehr ähnlich sind den sittlichen Intuitionen, wie ich sie in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» genannt habe.

Während wir bei der ersteren Art von Gedankenweben, das ja gewissermaßen als Unterströmung unseres klaren Bewußtseins verläuft, immer das Gefühl haben, wir stehen mit unserem wachen Träumen uns selbst gegenüber, da brodelt und sprudelt etwas in uns, können wir das bei dem Letztcharakterisierten nicht sagen. Bei dem Letztcharakterisierten müssen wir uns vielmehr sagen: Wenn wir beim Aufwachen wiederum in unseren Leib und zum Gebrauche unseres Leibes zurückkehren, dann sind wir nicht imstande, dasjenige festzuhalten, in dem wir denkend gelebt haben vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen.

Wer diese beiden Seiten des menschlichen Lebens sich so recht zum Bewußtsein bringt, der wird aufhören, Gedanken nur als etwas zu betrachten, das gewissermaßen im menschlichen Organismus gemacht wird. Denn namentlich dasjenige, was ich zuletzt charakterisiert habe, aus dem wir uns herausheben beim Aufwachen, das können wir gar nicht als irgendein Produkt des menschlichen Organismus als solchem unmittelbar ansehen, sondern das können wir nur ansehen als etwas, was wir erleben zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, wenn wir aus unserem Leibe herausgerissen sind mit unserem Ich und mit unserem astralischen Leibe.

Wo sind wir denn dann? Diese Frage muß man sich zunächst aufwerfen. Wir sind mit unserem Ich und mit unserem astralischen Leib außerhalb unseres physischen und unseres Ätherleibes. Eine einfache Erwägung, der man gar nicht entkommen kann, wenn man sich nur unbefangen dem Leben hingibt, muß uns sagen: In demjenigen, was uns erscheint, wenn wir die Sinne auf die Außenwelt richten, als der Sinnesschleier der Welt, als alles das, was Sinnesqualitäten uns darbieten, in dem sind wir, wenn wir außerhalb unser sind. Nur erlischt dann eben für das gewöhnliche Leben das Bewußtsein. Und wir fühlen, warum da das Bewußtsein erlischt, wenn wir eben des Morgens aus diesem Zustande aufwachen. Wir fühlen uns in unserem Leibe dann schwach, zu schwach, um darinnen festzuhalten, was wir erlebt haben vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen. Es können unser Ich und unser astralischer Leib, indem sie in den physischen und in den Ätherleib untertauchen, nicht festhalten dasjenige, was sie da erlebt haben. Und indem sie dann teilnehmen an den Erlebnissen, die durch den Leib gemacht werden, löscht sich für sie aus, was vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen erlebt wird. Und wie gesagt, nur wenn wir Einfälle haben, die sich auf die äußere Welt beziehen, oder auch wenn wir sittliche Intuitionen haben, dann erleben wir so etwas wie das, was uns bei einer unmittelbaren Betrachtung erscheinen muß als dasjenige, worin wir leben zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen.

Wenn wir die Sache so ansehen, dann bekommen wir einen sehr deutlichen Gegensatz zwischen unserem Inneren und der äußeren Welt. Dann wirft uns das auch in gewissem Sinne ein Licht auf die Aussage, die wir oftmals machen, daß die äußere Welt, so wie sie sich uns vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen darbietet, eine Art Täuschung, eine Art Maja ist. Denn in dieser Welt, die da ihre Außenseite uns zeigt, stecken wir darinnen, wenn wir nicht in unserem Leibe, sondern wenn wir außerhalb unseres Leibes sind. Dann tauchen wir unter in die Welt, die wir sonst nur durch unsere Sinnesoffenbarung wahrnehmen. So daß wir uns sagen müssen: Diese Welt, die wir da durch unsere Sinnesoffenbarung wahrnehmen, die hat Untergründe, Untergründe, die eigentlich ihre Ursachen, ihre Wesenheiten enthalten. Und diese Ursachen und diese Wesenheiten unmittelbar wahrzunehmen, sind wir im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein zu schwach.

Dennoch ergibt schon ein unbefangenes Beobachten etwas, was weit hineinreicht in die Regionen, die beschrieben sind in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?»; ein unbefangenes Beobachten ergibt schon dasjenige, was ich schematisch etwa in der folgenden Weise darstellen kann. Wenn ich das gewöhnliche Gedankenleben darstellen will, so geschieht es dadurch, daß ich es umfassen lasse all das, was der Mensch innerlich-gedanklich durchlebt vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen in Anlehnung an die äußeren Wahrnehmungen oder auch in Anlehnung an seine physischen Schmerzen, physischen Lustgefühle und so weiter. Was also im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein da gedanklich erlebt wird, das möchte ich zunächst schematisch etwa so darstellen (siehe Zeichnung, weiß). Unter diesem also, wie ein wachendes Träumen, webt und lebt, nicht den Gesetzen der Logik unterworfen, dasjenige, was ich zuerst dargestellt habe (rot unten). Dagegen, wenn wir zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen in die Außenwelt übergehen, leben wir, wie wir in Reminiszenz nach dem Aufwachen wahrnehmen können, wiederum in einer Welt des Gedankens, aber der Gedanken, die uns aufnehmen, die nicht in uns sind, aus denen wir herauskommen beim Aufwachen (rot außen). So daß wir gewissermaßen durch unser gewöhnliches Denken zwei Gedankenwelten voneinander geschieden haben: eine innere Gedankenwelt und eine äußere Gedankenwelt, eine Gedankenwelt, die den Kosmos, der uns aufnimmt beim Einschlafen, erfüllt. Wir können die letztere Gedankenwelt eben die kosmische Gedankenwelt nennen. Die erstere ist irgendeine Gedankenwelt; wir wollen noch näher auf sie eingehen im Laufe dieser Tage.

So sehen wir uns gewissermaßen mit unserer gewöhnlichen Gedankenwelt hineingestellt in eine allgemeine Gedankenwelt, welche wie durch eine Grenze auseinandergehalten wird, und von der ein Teil in uns, ein Teil außer uns ist. Dasjenige, was in uns ist, es erscheint uns sehr deutlich eben als eine Art von Traum. Es ruht immer auf dem Grund unserer Seele ein chaotisches Gedankengewebe, wir können sagen, etwas, was nicht von Logik durchzogen ist. Aber diese äußere Gedankenwelt, ja, wahrnehmen kann sie ja allerdings das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein nicht. Also aus unmittelbarem Anschauen, aus unmittelbarem Erleben kann die Natur dieser äußeren Gedankenwelt nur enthüllen das wirkliche geistige Schauen, das dann schon tiefer in die Regionen eintritt, die in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» beschrieben werden. Aber dann stellt sich auch heraus: Diese Gedankenwelt, in die wir da eintauchen zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, das ist eine Gedankenwelt, die nicht nur so logisch ist, wie unsere gewöhnliche Gedankenwelt logisch ist, sondern die eine viel höhere Logik enthält. Wenn man den Ausdruck nicht mißverstehen will, so möchte ich diese Gedankenwelt eine überlogische Gedankenwelt nennen. Sie ist, ich möchte sagen, ebensoweit über der gewöhnlichen Logik gelegen, wie unsere träumerische Welt, unsere wachende träumerische Welt unter der Logik gelegen ist.

Wie gesagt, das kann man nur durch geistiges Schauen ergründen. Aber es gibt einen andern Weg, durch den Sie dieses geistige Schauen in diesem Punkte kontrollieren können. Es ist Ihnen doch klar, in gewisse Regionen des eigenen Organismus kann das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein nicht untertauchen. Ich habe davon in den letzten Vorträgen viel gesprochen. Ich habe gesagt: Dadurch, daß wir für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein unser Gedächtnis, unser Erinnerungsvermögen haben, ist uns gewissermaßen nach innen hin eine Haut gezogen gegenüber unseren inneren Organen. Wir können nicht unmittelbar durch innere Anschauung beobachten, was die inneren Organe sind, Lunge, Leber und so weiter. Aber ich sagte auch: Es ist eine falsche Mystik, eine nebulose Mystik, welche nur so nach dem Inneren hinein phantasiert und etwa so redet wie die Heilige Therese oder die Mechthild von Magdeburg, die allerlei schöne poetische Bilder finden - die Schönheit soll nicht bestritten werden -, die aber nichts weiter sind als organische Ausflüsse. Gibt man sich nicht dieser nebulosen Mystik hin, sondern der wirklichen Geisteserforschung, so kommt man gerade, wenn man nach dem Inneren des Menschen vordringt, zu der Erkenntnis der Organe. Man sieht geistig die Bedeutung von Lunge, Leber, Niere und so weiter, man durchstößt geistig das Erinnerungshäutchen und kommt zu einem inneren Durchschauen des Menschen. Aber das ist etwas, was man mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein eben nicht erreichen kann. Mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein ist es nur möglich, äußerlich durch die Anatomie zu beobachten, wie die Organe sich ausnehmen, wenn man sie als angehörig der gewöhnlichen physischen und mineralischen Welt betrachtet. Aber innerlich anzuschauen, was sie an Kräften durchdringt, was sie durchsetzt, was in ihnen tätig ist, was ich Ihnen ja in den letzten Tagen beschrieben habe, dazu gehört ein wirklich ausgebildetes geistiges Anschauen.

Also da ist etwas in dem Menschen drunten, das er nicht erreichen kann mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein. Warum kann er es mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht erreichen? Weil es eben nicht allein ihm angehört. Was mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein zu erreichen ist, das gehört allein dem Menschen an. Dasjenige, was da unten in den Organen pulsiert, das gehört nicht allein dem Menschen an, das gehört dem Menschen als einem Weltenwesen an, das gehört zugleich dem Menschen und zugleich der Welt an.

Vielleicht wird es uns durch die folgende Erörterung am allerdeutlichsten. Wenn wir den Menschen schematisch anschauen und haben irgendein Organ, Lunge oder Leber in ihm, so haben wir in einem solchen Organe Kräfte. Diese Kräfte sind nicht bloß innere menschliche Kräfte, diese Kräfte sind Weltenkräfte. Und wenn alles, was äußere physische Welt ist und uns als physische Welt vor das Anschauen tritt, wenn das alles einstmals mit dem Erdenuntergang verschwunden sein wird, so wird weiter wirken dasjenige, was jetzt als innere Kräfte unserer Organe existiert. Man möchte sagen, alles, was unsere Augen sehen, unsere Ohren hören können, alle äußere Welt ist eine Welt, die zunächst abklingt mit dem Erdenende. Was unsere Haut bedeckt, was wir im Inneren tragen, was umschlossen wird von unserer Organisation, das enthält geistig dasjenige, was fortbesteht, wenn die äußere Welt, die unsere Sinne sehen, einstmals nicht mehr da sein wird. Im Grunde genommen arbeitet innerhalb der menschlichen Haut etwas, was über die Erde hinauslebt; innerhalb der menschlichen Haut liegen die Zentren, die Kräfte dessen, was über das Erdendasein hinausarbeitet. Wir stehen als Mensch nicht bloß in der Welt, damit wir für uns unsere Organe umschließen, wir stehen in der Welt als Mensch, damit der Kosmos selber innerhalb unserer Haut sich gestaltet. In demjenigen, wohin unser gewöhnliches Bewußtsein nicht reicht, umschließen wir etwas, was nicht bloß uns, was der Welt angehört. Das, was da der Welt angehört, ist es auferbaut aus dem, was die chaotischen Vorgänge des wachen Träumens darstellen?

Wir brauchen ja nur zu betrachten diese chaotischen Vorgänge des wachen Träumens und Sie werden sich sagen: Die ganze Struktur, alles das, was Sie da gewissermaßen als Unterströmung Ihres Bewußtseins wahrnehmen, das ist ganz gewiß nicht der Erbauer Ihrer Organe, Ihres ganzen Organismus. Der Organismus würde schön ausschauen, wenn alles das, was in Ihrem Unterbewußtsein da chaotisch herumlebt, Ihre Organe, Ihren ganzen Organismus aufbauen würde! Sie würden schon sehen, was Sie für sonderbare Karikaturen wären, wenn Sie ein Abbild dessen wären, was da in Ihrem Unterbewußtsein pulsiert. Nein, geradeso wie die äußere Welt, die sich uns durch die Sinne offenbart, gewissermaßen offenbart an der Oberfläche, die sie uns zuneigt, wie diese Welt aus den Gedanken aufgebaut ist, die wir erleben zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen, so sind wir selbst in dem, was wir in uns nicht erreichen mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, auferbaut aus denselben äußeren Gedankenkräften. Wenn ich also vollständig das darstellen will, was der Mensch ist, so müßte ich schematisch so zeichnen. Ich müßte sagen: Da ist die umliegende Gedankenwelt (rot). Diese umliegende Gedankenwelt baut auch den menschlichen Organismus auf, und dieser menschliche Organismus erzeugt, gewissermaßen auf ihm flutend, die höhere Gedankenwelt (weiß), der sich zuneigt die sinnliche äußere Maja zwischen unseren Gedanken und der umliegenden Welt (blau).

Versuchen Sie sich einmal recht gegenwärtig zu machen, wie es eigentlich nur ein kleiner Teil von Ihnen selbst ist, was Sie da mit dem Bewußtsein umspannen, und wie ein großer Teil von Ihnen selbst aus derselben äußeren Welt aufgebaut ist, in die Sie untertauchen zwischen dem Einschlafen und dem Aufwachen. Aber das ist ja auch schließlich bei unbefangener Betrachtung des Menschen noch von einer andern Seite her zu bemerken, und ich habe auf diese Seite auch schon öfter hier hingedeuter.

Der Mensch umfaßt eigentlich mit seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nur seine Gedanken; seine Gefühle sind schon wie unter den Gedanken schwimmende Träume. Gefühle tauchen auf, fluten ab. Der Mensch durchschaut sie nicht in der Klarheit, in der er seine Gedanken, seine Vorstellungen durchschaut. Aber ganz gleich mit dem Erleben zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen ist das Erleben desjenigen, was in uns während des Tages willensmäßig ist. Und was weiß der Mensch - so sagte ich Ihnen oft - von dem, was vorgeht, wenn er durch den Willen seine Hand oder seinen Arm bewegt! Er kennt das alles vorstellungsgemäß, er weiß zuerst: Ich will meinen Arm bewegen. Das ist eine Vorstellung. Er weiß dann, wie das aussieht an seiner Gestalt, wenn er den Arm bewegt hat: wieder Vorstellung. Was er davon in seinem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein weiß, das ist ein Gewebe von Vorstellungen; unter diesem Gewebe von Vorstellungen fluten Gefühle. Aber was da als Wille in ihm wirkt, das schläft auch während des Wachens geradeso stark, wie unser ganzer Mensch schläft vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen.

Was schläft da? Das, was da unten schläft, was aus dem äußeren Kosmos in uns hineingebaut ist, das ist genauso etwas Schlafendes, wie draußen die Mineralien und Pflanzen schlafend sind für uns. Das heißt: Wir dringen nicht von außen in sie ein, sehen nicht hinunter in das, was für uns kosmisch ist. Wir weben und leben in diesem Kosmischen vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen. Und in demselben Maße, wie wir die äußere Welt durchschauen, leben wir uns in unsere eigene Organisation ein. In demselben Maße hören wir auf, bloß Erinnerungsreminiszenzen zu haben, wie wir sie aus den Ereignissen des Lebens schälen, sondern wir bekommen Vorstellungen von Kräften, die unsere Organe die Lunge, die Leber, den Magen und so weiter — konstituieren, auferbauen. In demselben Maße, wie wir lernen, die äußere Welt zu durchschauen, lernen wir unser Stück Kosmos zu durchschauen, das wir eingegliedert haben, in dem wir sind, das in unserer Haut ist, ohne daß wir im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein etwas davon wissen.

Was nehmen wir uns denn des Morgens beim Aufwachen aus diesem Kosmos mit? Dasjenige, was wir uns mitnehmen, das erlebt sich für den unbefangenen Beobachter sehr deutlich als Wille. Und im Grunde genommen unterscheidet sich das wache Denkleben von dem, was da unten träumend im Unterbewußtsein strömt, auch eben durch nichts anderes, als daß es vom Willen durchströmt wird. Der Wille ist es, der Logik hineinbringt, und die Logik ist im Grunde genommen nicht eigentlich eine Denklehre, sondern die Logik ist eine Lehre davon, wie der Wille die Gedankenbilder ordnet und bändigt und sie in eine gewisse äußere Ordnung bringt, die dann dem äußeren Weltenverlauf entspricht.

Wenn wir aufwachen mit einem Traum, da nehmen wir besonders stark dieses Gewoge da unten von chaotischen, unlogischen Bilderwirbeln wahr, und wir können es bemerken, wie wir einschlagen sehen in dieses chaotische Bilderwirbeln den Willen, der dann das, was da in uns lebt, so anordnet, daß es eben logisch geordnet ist. Aber wir nehmen nicht die Weltenlogik mit, was ich eben früher überlogisch genannt habe, wir nehmen nur den Willen mit.

Wie kommt es denn, daß dieser Wille nun doch in uns logisch wirkt? Sehen Sie, hier liegt ein wichtiges Menschengeheimnis, etwas außerordentlich Bedeutsames. Es ist dieses: Wenn wir untertauchen in unsere für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein nicht vorhandene kosmische Existenz, wenn wir untertauchen in unsere ganze Organisation, dann spüren wir in unserem Willen, der sich da ausbreitet, die kosmische Logik unserer Organe. Wir spüren die kosmische Logik unserer Organe.

Es ist außerordentlich wichtig, daß man sich das ganz klarmacht, daß, wenn wir des Morgens aufwachen, also eintauchen in unseren Leib, wir durch dieses Eintauchen gezwungen werden, den Willen in einer gewissen Weise zu formen. Wäre unser Leib nicht schon in einer gewissen Weise geformt, der Wille, der würde nach allen Seiten quallenhaft wirbeln beim Aufwachen; der Wille könnte beim Aufwachen quallenhaft nach allen Seiten chaotisch streben. Das tut er nicht, weil er in die bestehende Menschenform eintaucht. Da taucht er unter, nimmt alle diese Formen an; das gibt ihm die logische Gliederung. Das macht es, daß er aus dem Menschenleib heraus den sonst chaotisch durcheinanderwirbelnden Gedanken die Logik gibt. In der Nacht, wenn der Mensch schläft, ist der Mensch eingespannt in die Überlogik des Kosmos. Die kann er nicht festhalten. Aber wenn er nun in den Leib untertaucht, so nimmt der Wille die Form des Leibes an. Genau so, wie wenn Sie Wasser in ein Gefäß hineingießen und das Wasser die Form des Gefäßes annimmt, so nimmt der Wille die Form des Leibes an. Aber nicht nur, wie wenn Sie Wasser in ein Gefäß gießen und das Wasser nimmt die ganze Form des Gefäßes an, nicht nur so ist es beim Willen, daß er die Raumesformen annimmt, sondern er fließt in die kleinsten Aderchen überall hinein. Das kann sich ja nicht bewegen höchstens beim Professor Traub bewegen sich Tische und Stühle im Raume von selbst, das ist jedoch theologische Universitätslogik, sonst bewegt sich solch ein Gerät nicht —, da nimmt das Wasser die ruhende Form an und nur an den Außenwänden stößt es an. Aber beim Menschen gliedert sich dieser Wille ganz hinein in alle einzelnen Verzwei gungen und von da aus beherrscht er dann den sonstigen chaotischen Bilderablauf. Dasjenige, was man da also als Unterströmung wahrnimmt, das ist, möchte ich sagen, losgelassen vom Leib. Das ist auch wirklich losgelassen vom Leib, das ist etwas, was zwar mit dem Menschenleib verbunden ist, was aber eigentlich fortwährend sich frei zu machen strebt vom Menschenleib, was fortwährend heraus will aus den Formen dieses Menschenleibes. Dasjenige aber, was der Mensch beim Einschlafen herausträgt aus dem Leib, was er in den Kosmos hineinträgt, was dann untertaucht, das fügt sich dem Gesetz des Leibes an.

Nun ist es so, daß mit all der Organisation, die des Menschen Kopforganisation ist, der Mensch bloß zu Bildern käme. Es ist ein allgemeines physiologisches Vorurteil, daß wir zum Beispiel mit dem Kopf auch urteilen und schließen. Nein, wir stellen mit dem Kopf bloß vor. Wenn wir den Kopf bloß hätten und der übrige Leib wäre untätig für unser Vorstellungsleben, dann würden wir wachende Träumer sein. Der Kopf hat nämlich nur das Vermögen, wachend zu träumen. Und wenn wir auf dem Umwege über den Kopf am Morgen wieder zurückkehren in unseren Leib, indem wir den Kopf passieren, kommen uns die Träume ins Bewußtsein. Erst wenn wir tiefer in unseren Leib wieder eindringen, wenn sich der Wille nicht nur dem Kopf, sondern der übrigen Organisation wiederum anpaßt, erst dann ist dieser Wille wieder in der Lage, Logik in die sonst bildhaft ineinanderwurlenden Bilderkräfte hineinzubringen.

Das führt Sie dann zu etwas, was ich auch schon in den verflossenen Vorträgen vorgebracht habe. Man muß sich klar sein darüber, daß der Mensch vorstellt mit dem Haupte und daß er in Wirklichkeit urteilt, so sonderbar und paradox es klingt, mit den Beinen und auch mit den Händen, und dann auch wiederum schließt mit den Beinen und Händen. So entsteht, was wir einen Schluß, ein Urteil nennen. Wenn wir vorstellen, ist es nur das Bild, das in den Kopf zurückgestrahlt wird, urteilend und schließend sind wir als ganzer Mensch, nicht bloß als Kopfmensch. Dagegen kommt natürlich nicht auf, daß, wenn irgendein Mensch verstümmelt ist, er dann etwa nicht urteilen und schließen könne oder dürfe, denn es kommt darauf an, wie die Dinge veranlagt

sind bei solchen, denen gewissermaßen zufällig das eine oder andere Glied fehlt. Gelernt muß werden, das, was der Mensch geistig-seelisch ist, in Zusammenhang zu bringen mit dem ganzen Menschen, sich klarzuwerden darüber, daß wir Logik in unser Vorstellungsleben hineinbringen aus denselben Regionen heraus, die wir gar nicht mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein erreichen, die von dem Gefühlswesen und dem Willenswesen eingenommen werden. Unser Urteilen und unser Schließen geschieht aus denselben Schlafregionen unseres eigenen Inneren heraus, aus dem unser Fühlen und unser Wollen heraustönt.

Am meisten kosmisch ist in uns die mathematische Region. Die mathematische Region gehört uns nicht einmal bloß als ruhendem Menschen an, sondern als herumgehendem Menschen. Wir bewegen uns ja immer irgendwie in mathematischen Figuren. Wenn wir das äußerlich ansehen an einem herumgehenden Menschen, so sehen wir etwas Räumliches; wenn wir es innerlich erleben, erleben wir die uns innerliche Mathematik, die eine kosmische ist, nur daß das Kosmische uns auch aufbaut. Die Raumesrichtungen, die wir draußen haben, die bauen uns auch auf und in uns erleben wir sie. Und indem wir sie erleben, abstrahieren wir sie, nehmen die Bilder, die sich im Gehirn spiegeln und verweben sie mit dem, was sich äußerlich räumlich in der Welt uns zeigt.

Es ist schon notwendig, daß heute aufmerksam darauf gemacht wird, daß eigentlich dasjenige, was der Mensch mathematisierend in die Welt hineinlegt, dasselbe ist, was ihn aufbaut, was also kosmischer Natur ist. Denn durch den unsinnigen Kantianismus ist der Raum bloß zu einer subjektiven Form gemacht worden. Er ist nicht eine subjektive Form, er ist etwas, was wir gerade in derselben Region real erleben, wo wir das Willensmäßige erleben. Und da scheint es herauf. Da wird das Heraufscheinen zur Welt etwas, mit dem wir dann durchdringen dasjenige, was sich äußerlich darbietet.

Die heutige Welt ist noch weit entfernt davon, dieses innerliche Verwobensein des Menschen mit dem Kosmos studieren zu können, dieses Darinnenstehen des Menschen in dem Kosmos. Ich habe auf dieses Darinnenstehen eklatant aufmerksam gemacht in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit», wo Sie an bemerkenswerten Stellen finden werden, wie ich zeige, daß der Mensch unter dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein zusammenhängt mit dem ganzen Kosmos, daß er ein Glied ist des ganzen Kosmos, und daß dann gewissermaßen aufblüht aus diesem allgemein Kosmischen das Individuell-Menschliche, das dann mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein umfaßt wird. Gerade diese Stelle meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» ist von den wenigsten verstanden worden; die meisten haben nicht gewußt, um was es sich handelt. Es ist auch kein Wunder, daß in einem Zeitalter, in dem die Abstraktion bis zur Einsteinerei blüht, daß in einem Zeitalter, in dem diese allerdings in sich außerordentlich geistreiche, aber eben absolut abstrakte Anschauung als etwas Besonderes der Welt vorgeführt wird, dasjenige nicht verstanden wird, was in die Wirklichkeit, eben in die wahre Wirklichkeit einführen will.

Es muß immer wieder betont werden: Es genügt nicht, daß irgend etwas logisch ist. Logisch ist die Einsteinerei, wirklichkeitsgemäß ist sie nicht. Aller Relativismus ist als solcher nicht wirklichkeitsgemäß. Das wirklichkeitsgemäße Denken fängt erst da an, wo man nicht mehr die Realität verlassen kann, indem man denkt. Nicht wahr, es liest heute der Mensch, oder hört, möchte ich sagen, ganz gelassen zu, wenn der Einstein sagt als Beispiel: Wie würde es sein, wenn eine Uhr mit Lichtgeschwindigkeit in den Kosmos hinausflöge? — Ja, das hört sich heute ein Mensch ganz ruhig an. Eine Uhr, die mit Lichtgeschwindigkeit in den Kosmos hinausfliegt, das ist ungefähr für denjenigen, der wirklichkeitsgemäß in seinem Denken lebt, wirklichkeitsgemäß in seiner Seele lebt, ungefähr so, wie wenn einer sagt: Wie wird der Mensch, wenn ich ihm den Kopf abschneide, und dazu ihm die rechte Hand und die linke Hand oder den rechten Arm und so weiter abschneide? — Er hört eben auf, ein Mensch zu sein. So hört dasjenige, was man noch berechtigt ist vorzustellen, wenn man davon redet, daß eine Uhr mit Lichtgeschwindigkeit in den Kosmos hinausfliege, gleich auf, eine Uhr zu sein! Es ist nicht möglich, das vorzustellen. Das Wirklichkeitsgemäße muß festgehalten werden, wenn man zu einem gültigen Denken kommen will. Logisch, geistvoll kann etwas in ungeheurem Maße sein, aber es braucht noch nicht wirklichkeitsgemäß zu sein. Ein wirklichkeitsgemäßes Denken aber brauchen wir in diesem Zeitalter. Denn das abstrakte Denken führt uns endlich wirklich dazu, eben die Wirklichkeit vor lauter Abstraktionen nicht mehr zu sehen. Und heute bewundert die Menschheit die Abstraktionen, die ihr in dieser Weise dargeboten werden. Daß man diese Abstraktionen irgendwie logisch belegt oder dergleichen, darauf kommt es nicht an. Es kommt darauf an, daß der Mensch lernt, mit der Wirklichkeit zusammenzuwachsen, so daß er nicht mehr etwas anderes sagen kann als dasjenige, was eben auch aus der Wirklichkeit heraus gesprochen wird.

Aber solche Vorstellungen über den Menschen selbst, wie ich sie Ihnen heute wiederum vorgeführt habe, die geben eine Art Anleitung zu einem wirklichkeitsgemäßen Denken. Sie werden vielfach heute verspottet von denen, die dressiert sind durch unser abstraktes Denken. Durch drei bis vier Jahrhunderte ist ja die abendländische Menschheit dressiert durch bloße Abstraktion. Aber wir leben in dem Zeitalter, wo eine Umkehr nach dieser Richtung stattfinden muß, wo wir den Weg zurück zur Wirklichkeit finden müssen. Materialistisch sind die Menschen geworden, nicht weil sie die Logik verloren haben, sondern weil sie die Wirklichkeit verloren haben. Logisch ist der Materialismus, logisch ist der Spiritualismus, logisch ist der Monismus, logisch ist der Dualismus, logisch ist alles, wenn es nur nicht eben auf wirklichen Denkfehlern beruht. Aber dadurch, daß etwas logisch ist, entspricht es noch nicht der Wirklichkeit. Wirklichkeit kann nur gefunden werden, wenn wir unser Denken selber immer mehr und mehr hereinbringen in diejenige Region, von der ich gesagt habe: Im reinen Denken hat man das Weltgeschehen an einem Zipfel. - Das steht in meinen erkenntnistheoretischen Schriften, und das ist dasjenige, was als Grundlage eines Weltverständnisses gewonnen werden muß.

In dem Augenblicke, wo man das Denken noch hat, trotzdem man keine sinnliche Anschauung hat, in dem Augenblick hat man das Denken zugleich als Wille. Es ist kein Unterschied mehr zwischen Wollen und Denken. Denn das Denken ist ein Wollen und das Wollen ist dann ein Denken. Wenn das Denken ganz sinnlichkeitsfrei geworden ist, dann hat man das Weltgeschehen an einem Zipfel. Und das ist es, was man vor allen Dingen anstreben muß: den Begriff zu bekommen von diesem reinen Denken. Von diesem Punkte aus wollen wir dann morgen weiter reden.