Cosmosophy I

GA 207

30 September 1921, Dornach

Lecture III

Today we will go somewhat further into what we considered here last Friday and Saturday, and I would like to draw your attention particularly to the life of the soul and what we discover when this soul life is viewed from the viewpoint of Imaginative cognition. You are familiar with Imaginative cognition from my book, Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment. You know that we distinguish four stages of cognition, ascending from our ordinary consciousness, the stage of cognition that is adapted to our daily normal life, to ordinary modern science, and that constitutes the actual consciousness of the time. This stage of consciousness is called “objective cognition” in the sense of what is described in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds. Then one comes into the realm of the super-sensible through the stages of Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition. With ordinary objective cognition it is impossible to observe the soul element. What pertains to the soul must be experienced, and in experiencing it one develops objective cognition. Real cognition can be gained, however, only when one can place the thing to be known objectively before one. It is impossible to do this with the soul life in ordinary consciousness; to understand the life of the soul, one must draw back a stage, as it were,so that the life of the soul comes to stand outside one; then it can be observed. This is precisely what is brought about through Imaginative cognition, and today I would like simply to describe for you what is then brought into view.

You know that if we survey the human being, confining ourselves to what exists in the human being today, we distinguish the physical body, the etheric body or body of formative forces, which is really a sum of activities, the astral body, and the I or ego. If we now bring the soul experience not into cognition but into consciousness, we distinguish in its fluctuating life thinking, feeling, and willing. It is true that thinking, feeling, and willing play into one another in the ordinary life of the soul; you can picture no train of thought without picturing the role played in this train of thought by the will. How we combine one thought with another, how we separate a thought from another, is most definitely an act of will striving into the life of thought .Though the process may at first remain shrouded, as I have often explained, we nevertheless know that when we as human beings use our will, our thoughts play into our will as impulses. In the ordinary soul life, therefore, our will is not isolated in itself but is permeated by thought. Even more do thoughts, will impulses, and the actual feelings flow into feeling. Thus we have throughout the soul life a flowing together, yet by reason of things we cannot go into today we must distinguish, within this flowing life of soul,thinking, feeling, and willing. If you refer to my Philosophy of Freedom, you will see how one is obliged to loosen thinking purely from feeling and willing, because one comes to a vis ion of human freedom only by means of such a loosened thinking.

Inasmuch as we livingly grasp thinking, feeling, and willing we grasp at the same time the flowing, weaving life of soul. Then, when we compare what we grasp there in immediate vitality with what an anthroposophical spiritual science teaches us of the connection among the individual members of the human being—physical body, etheric body, astral body, and I—what presents itself to Imaginative cognition is the following.

We know that during waking life the physical, etheric,astral bodies, and the I are in a certain intimate connection. We know further that in the sleeping state we have a separation of the physical and etheric bodies on the one hand from the astral body and I on the other. Although it is only approximately correct to say that the I and astral body separate from the physical body and etheric body, one arrives there by at a valid mental image. The I with the astral body is outside the physical and etheric bodies from the time we fall asleep to the moment of awakening.

As soon as the human being advances to Imaginative cognition he becomes more and more able to apprehend exactly in inner vision, with the eye of the soul, what is experienced as transitory, in status nascendi. The transitory is there, and one must seize it quickly, but it can be seized. One has something before one that can be observed most clearly at the moments of awaking and falling asleep. These moments of falling asleep and awaking can be observed by Imaginative cognition. Among the preparations necessary to attain higher levels of cognition you will remember that mention was made in the books already referred to of the cultivation of a certain presence of mind [Geistesgegenwart]. One hears so little said in ordinary life of the observations that may be made of the spiritual world, because people lack this presence of mind. Were this presence of mind actively cultivated among human beings, all people would be able to talk of spiritual, super-sensible impressions, for such impressions actually crowd in upon us to the greatest extent as we fall asleep or awake, particularly as we awake. It is only because this presence of mind is cultivated so little that people do not notice these impressions. At the moment of awaking a whole world appears before the soul. As quickly as it arises, however, it fades again, and before people think to grasp it, it is gone. Hence they can speak little of this whole world that appears before the soul and that is indeed of particular significance in comprehending the inner being of man.

When one is actually able to grasp the moment of awaking with this presence of mind, what confronts the soul is a whole world of flowing thoughts. There need be nothing of fantasy; one can observe this world with the same calm and self-possession with which one observes in a chemical laboratory. Nevertheless, this flowing thought world is there and is quite distinct from mere dreams. The mere dream is filled with reminiscences of life, whereas what takes place at the moment of awaking is not concerned with reminiscences. These flowing thoughts are clearly to be distinguished from reminiscences. One can translate them into the language of ordinary consciousness, but fundamentally they are foreign thoughts, thoughts we cannot experience if we do not grasp them in the moment made possible for us by spiritual scientific training, or even in the moment of awaking.

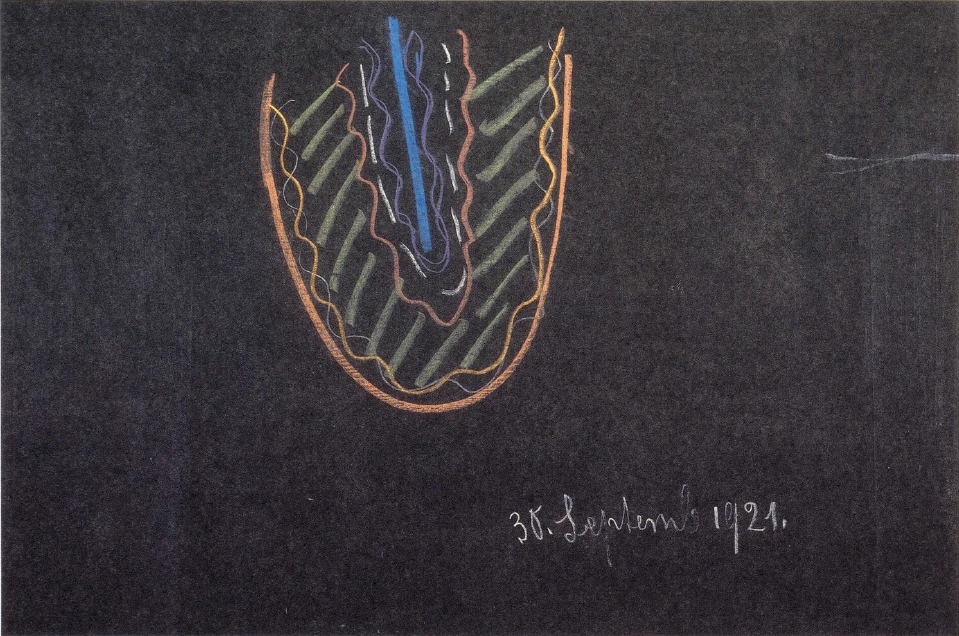

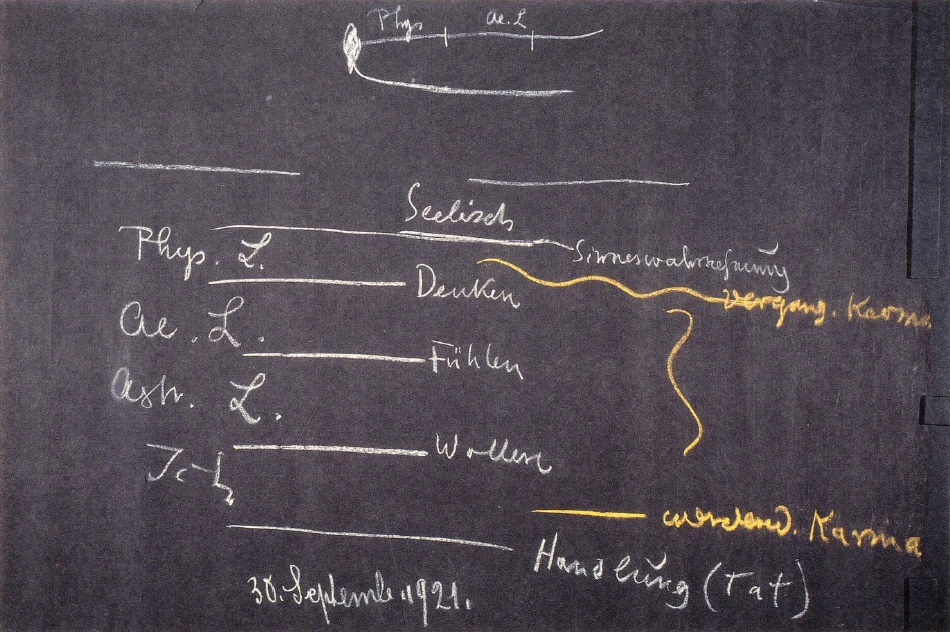

What is it that we actually grasp at such a moment? We have penetrated into the etheric body and physical body with our I and astral body. What is experienced in the etheric body is experienced, however, as dreamlike. One learns, in observing this subtly in presence of mind, to distinguish clearly between this passing through the etheric body, when life reminiscences appear dreamlike, and the state—before fully awaking, before the impressions that the senses have after awaking—of being placed in a world that is thoroughly a world of weaving thoughts. These thoughts are not experienced, however, as dream thoughts, such as one knows are in oneself subjectively. The thoughts that I mean now confront the penetrating I and astral body of man entirely objectively; one realizes distinctly that one must pass right through the etheric body, for as long as one is passing through the etheric body, everything remains dreamlike. One must also pass through the abyss, the intermediate space—to express myself figuratively and perhaps therefore more clearly—the space between etheric body and physical body. Then one slips fully into the etheric-physical on awaking and receives the outer physical impressions of the senses. As soon as one has slipped into the physical body, the outer physical sense impressions are simply there. What we experience as a thought-weaving of an objective nature takes place completely between the etheric body and the physical body. We must therefore see in it an interplay of the etheric and physical bodies. If we present this pictorially (see drawing), we can say that if this represents the physical body (orange) and this the etheric body (green), we have the living weaving of physical body and etheric body in the thoughts that we grasp there. Through this observation one comes to know that whether we are asleep or awake processes are always taking place between our physical body and etheric body, processes that actually consist of the weaving thought-existence between our physical and etheric bodies (yellow). We have now grasped objectively the first element of the life of the soul; we see in it a weaving between the etheric body and the physical body.

This weaving life of thought does not actually come into our consciousness as it is in the waking state. It must be grasped in the way I have described. When we awake we slip with our I and astral body into our physical body. I and astral body within our physical body, permeated by the etheric body, take part in the life of sense perception. By having within you the life of sense perception, you become permeated with the thoughts of the outer world, which can form in you from the sense perceptions and have then the strength to drown this objective thought-weaving. In the place where otherwise the objective thoughts are weaving, we form out of the substance of this thought-weaving, as it were, our everyday thoughts, which we develop in our association with the sense world. I can say that into this objective weaving of thought there plays the subjective thought-weaving (bright) that drowns the other and that also takes place between the etheric body and the physical body. In fact, when we weave thoughts with the soul itself we live in what I have called the space between the etheric and physical bodies—as I said, this expression is figurative, but to make this understandable I must designate it as the space between the etheric and physical bodies. We drown the objective thoughts, which are always present in the sleeping and waking states, with our subjective weaving of thought. Both, however, are present in the same region, as it were, of our human nature: the objective weaving of thought and the subjective thought-weaving.

What is the significance of the objective thought-weaving? When the objective thought-weaving is perceived, when the moment of awaking is actually grasped with the presence of mind I have described, it is grasped not merely as being of the nature of thought but as what lives in us as forces of growth, as forces of life in general. These life forces are united with the thought-weaving; they permeate the etheric or life body inwardly and shape the physical body outwardly. What we perceive as objective weaving of thought when we can seize the moment of awaking with presence of mind, we perceive as thought-weaving on the one hand and as activity of growth and nutrition on the other. What is within us in this way we perceive as an inner weaving, but one that is fully living. Thinking loses its picture-nature and abstractness, it loses all that had been sharp contours. It becomes a fluctuating thinking but is clearly recognizable as thinking nevertheless. Cosmic thinking weaves in us, and we experience how this cosmic thinking weaves in us and how we plunge into this cosmic thinking with our subjective thinking. We have thus grasped the soul element in a certain realm.

When we now go further in grasping the waking moment in presence of mind we find the following. When we are able to experience the dreamlike element in passing through the etheric body with the I and astral body, we can bring to mind pictorially the dreamlike element in us. These dream pictures must cease the moment we awake, however, for otherwise we would take the dream into the ordinary, conscious waking life and be daydreamers, thus losing our self-possession. Dreams as such must cease. The usual experience of the dream is an experience of reminiscing, is actually a later memory of the dream; the ordinary experiencing of the dream is actually first grasped as a reminiscence after the dream departs. It may be grasped while it exists, however, while it actually is, if one carries the presence of mind right back to the experience of the dream. If it is thus grasped directly, during the actual penetration of the etheric body, then the dream is revealed as something mobile, something that one experiences as substantial, within which one feels oneself. The picture-nature ceases to be merely pictorial; one has the experience that one is within the picture. Through this feeling that one is within the picture, one is in movement with the soul element; as in waking life one's body is in movement through various movements of the legs and hand, so actually does the dream become active. It is thus experienced in the same way as one experiences the movement of an arm, leg, or head; when one experiences the grasping of the dream as something substantial, then in the further progress toward awakening yet another experience is added. One feels that the activity experienced in the dream, when one stands as if within something real, dives down into our bodily nature. Just as in thinking we feel that we penetrate to the boundary of our physical body, where the sense organs are, and perceive the sense impressions with the thinking, so we now feel that we plunge into ourselves with what we experience in the dream as inner activity. What is experienced at the moment of awaking, or rather just before the moment of awaking, when one is within the dream, still completely outside the physical body but already within the etheric body, or passing through it—is submerged into our organization. And if one is so advanced that one has this submerging as an experience, then one knows, too, what becomes of what has been submerged—it radiates back into our waking consciousness, and it radiates back as a feeling, as feeling. The feelings are dreams that have been submerged into our organization.

When we perceive what is weaving in the outer world in this dreamlike state, it is in the form of dreams. When dreams dive down into our organization and become conscious from within outward, we experience them as feelings. We thus experience feeling through the fact that what is in our astral body dives down into our etheric body and then further into our physical organization, not as far as the senses and therefore not to the periphery, but only into the inner organization. Then, when one has grasped this, has beheld it first through Imaginative cognition, particularly clearly at the moment of awaking, one also receives the inner strength to behold it continuously. We do indeed dream continuously throughout waking life. It is only that we overpower the dream with the light of our thinking consciousness, our conceptual life [Vorstellungsleben]. One who can gaze beneath the surface of the conceptual life—and one trains oneself for this by grasping the moment of the dream itself with presence of mind—whoever has so trained himself that on awaking he can grasp what I have described, can then also, beneath the surface of the light-filled conceptual life, experience the dreaming that continues throughout the day. This is not experienced as dreams, however, for it immediately dives down into our organization and rays back as the world of feeling. What feeling is takes place between the astral body (bright in last drawing) and the etheric body. This naturally expresses itself in the physical body. The actual source of feeling, however, lies between the astral body and the etheric body (red). Just as for the thought life the physical and etheric bodies must cooperate in a living interplay, so must etheric body and astral body be in living interplay for the life of feeling. When we are awake we experience this living interplay of our mingled etheric and astral bodies as our feeling. When we are asleep we experience what takes place in the astral body, now living outside the etheric body, as the pictures of the dream. These dream pictures now are present throughout the period of sleep but are not perceptible to the ordinary consciousness; they are remembered in those fragments that form the ordinary life of dream.

You see from this that if we wish to grasp the life of the soul we must look between the members of the human organization. We think of the life of the soul as flowing thinking, feeling, and willing. We grasp it objectively, however, by looking into the spaces between these four members, between the physical body and the etheric body and between the etheric body and the astral body.

I have often explained here from other viewpoints how what is expressed in willing is withdrawn entirely from ordinary waking consciousness. This ordinary consciousness is aware of the mental images by which we direct our willing. It is also aware of the feelings that we develop in reference to the mental images as motives for our willing and of how what lies clear in our consciousness as the conceptual content of our willing plays downward when I move an arm in obedience to my will. What actually goes on to produce the movement does not come into ordinary consciousness. As soon as the spiritual investigator makes use of Imagination and discovers the nature of thinking and feeling he can also come to a consciousness of man's experiences between falling asleep and awaking. By the exercises leading to Imagination, the I and astral body are strengthened; they become stronger in themselves and learn to experience themselves. In ordinary consciousness one does not have the true I. What do we have as the I in our ordinary consciousness? This must be explained by a comparison I have made repeatedly. You see, when one looks back upon life in the memory, it appears as a continuous stream, but it is definitely not that. We look back over the day to the moment of awaking, then we have an empty space, then the memory of the events of the previous day links itself on, and so forth. What we observe in this reminiscence bears in itself also those states that we have not lived through consciously, that are therefore not within the present content of our consciousness. They are there, however, in another form. The reminiscing of a person who never slept at all—if I may cite such a hypothetical case—would be completely destroyed. The reminiscence would in a way blind him. All that he would bring to his consciousness in reminiscence would seem quite foreign to him, dazzling and blinding him. He would be overpowered by it and would have to eliminate himself entirely. He would not be able to feel himself within himself at all. Only because of the intervals of sleep is reminiscence dimmed so that we are able to endure it. Then it becomes possible to assert our own self in our remembering. We owe it solely to the intervals of sleep that we have our self-assertion in memory. What I am now saying could well be, confirmed through a comparative observation of the course of different human lives.

In the same way that we feel the inner activity in reminiscence, we actually feel our I from our entire organism. We feel it in the way we perceive the sleeping conditions as the darkest spaces in the progress of memory. We do not perceive the I directly in ordinary consciousness; we perceive it only as we perceive the sleeping condition. When we attain Imaginative cognition, however, this I really appears, and it is of the nature of will. We notice that what creates a feeling inclining us to feel sympathy or antipathy with the world, or whatever activates willing in us, then comes about in a process similar to that taking place between being awake and falling asleep. This again can be observed with presence of mind if one develops the same capacities for observation of the process of going to sleep as those I have described for awaking. Then one notices that on going to sleep one carries into the sleeping condition what streams as activity out of our feeling life, streaming into the outer world. One then learns to recognize how every time one actually brings one's will into action one dives into a state similar to the sleeping state. One dives into an inner sleep. What takes place once when one falls asleep, when the I and astral body draw themselves out of the physical body and the etheric body, goes on inwardly every time we use our will.

You must be clear, of course, that what I am now describing is far more difficult to grasp than what I described before, for the moment of going to sleep is generally still harder to grasp with presence of mind than that of awaking. After awaking we are awake and have at least the support of reminiscing. If we wish to observe the moment of falling asleep we must continue the waking state right into sleep. A person generally goes straight to sleep, however; he does not bring the activity of feeling into the sleeping state. If he can continue it, however—and this is actually possible through training—then in Imaginative cognition one notices that in willing there is in fact a diving into the same element into which we dive when we fall asleep. In willing we actually become free of our organization; we unite ourselves with real objectivity. In waking we enter our etheric and physical bodies and pass right up to the region of the senses, thus coming to the periphery of the body, taking possession of it, saturating it entirely. Similarly, in feeling we send our dreams back into the body, inasmuch as we immerse ourselves inwardly; the dreams, in fact, become feelings. If now we do not remain in the body but instead, without going to the periphery of the body, leave the body inwardly, spiritually, then we come to willing. Willing, therefore, is actually accomplished independently of the body. I know that much is implied in saying this, but I must present it, because it is a reality. In grasping it we come to see that—if we have the I here (see last drawing, blue)—willing takes place between the astral body and the I (lilac).

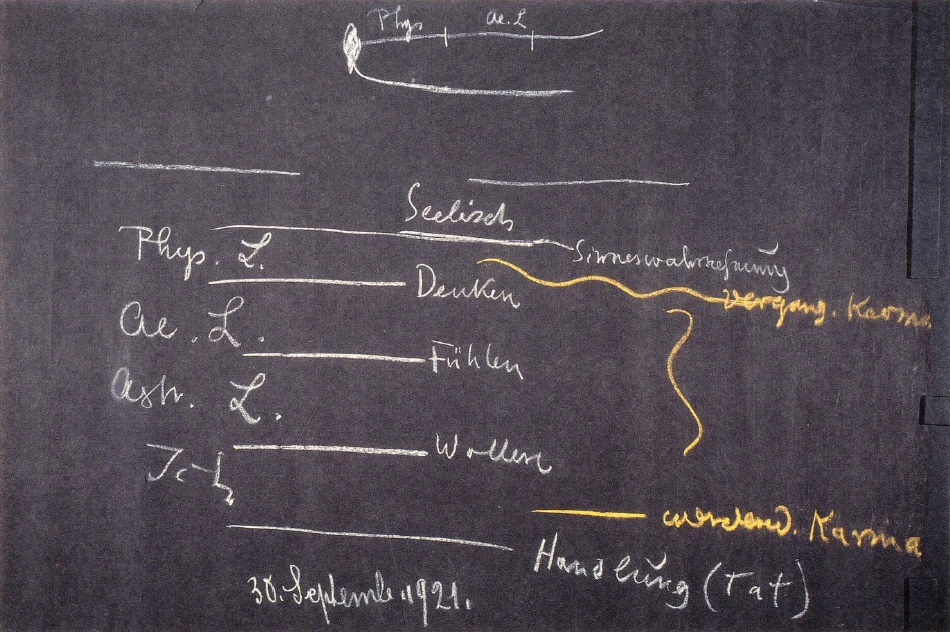

We can therefore say that we divide the human being into physical body, etheric body or body of formative forces, astral body, and I. Between the physical body and the etheric body thinking takes place in the soul element. Between the etheric body and the astral body feeling takes place in the soul element, and between the astral body and the I, willing takes place in the soul element. When we come to the periphery of the physical body we have sense perception. Inasmuch as by way of our I we emerge out of ourselves, placing our whole organization into the outer world, willing becomes action, the other pole of sense perception (see last drawing).

In this way one comes to an objective grasp of what is experienced subjectively in flowing thinking, feeling, and willing. Experience metamorphoses into cognition. Any psychology that tries to grasp the flowing thinking, feeling, and willing in another way remains formal, because it does not penetrate to reality. Only Imaginative cognition can penetrate to reality in the experience of the soul.

Let us now turn our gaze to a phenomenon that has accompanied us, as it were, in our whole study. We said that through observation with presence of mind at the moment of awaking, when one has slipped through the etheric body, one can see a weaving of thoughts that is objective. One at first perceives this objective thought-weaving. I said that it can be distinguished clearly from dreams and also from the everyday life of thought, from the subjective life of thought, for it is connected with growth, with becoming. It is actually a real organization. If one grasps what is weaving there, however, what, if one penetrates it, one perceives as thought-weaving; if one inwardly feels it, touches it, I would like to say, then one is aware of it as force of growth, as force of nutrition, as the human being in the process of becoming. It seems at first something foreign, but it is a world of thought. If one can study it more accurately it is seen to be the inner weaving of thoughts in ourselves. We grasp it at the periphery of our physical body; before we arrive at sense perception we grasp it. When we learn to understand it more exactly, when we have accustomed ourselves to its foreignness compared with our subjective thinking, then we recognize it. We recognize it as what we have brought with us through our birth from earlier experiences, from experiences lying before birth or conception. For us it becomes something of the spiritual, objectively present, that brings our whole organism together. Pre-existent thought gains objectivity, becomes objectively visible. We can say with an inner grasp that we are woven out of the world of spirit through thought. The subjective thoughts that we add stand in the sphere of our freedom. Those thoughts that we behold there form us, they build up our body from the weaving of thought. They are our past karma (see next diagram). Before we arrive at sense perceptions, therefore, we perceive our past karma.

When we go to sleep, one who lives in objective cognition sees something in this process of falling asleep that is akin to willing. When willing is brought to complete consciousness one notices quite clearly that one sleeps in one's own organism. Just as dreams sink down, so do the motives of the will pass into our organization. One sleeps into the organism. One learns to distinguish this sleeping into the organism, which first comes to life in our ordinary actions. These indeed are accomplished outwardly; we accomplish them between awaking and going to sleep, but not everything that lives within our life of feeling lives into these actions. We go through life also between falling asleep and awaking. What we would otherwise press into the actions, we press out of ourselves through the same process in going to sleep. We press a whole sum of will impulses out into the purely spiritual world in which we find ourselves between going to sleep and awaking. If through Imaginative cognition we learn to observe the will impulses that pass over into our spiritual being, which we shelter only between falling asleep and awaking, we perceive in them the tendency to action that exists beyond death, that passes over with us beyond death.

Willing is developed between the astral body and the I. Willing becomes deed when it goes far enough toward the outer world to come to the place to which otherwise the sense impressions come. In going to sleep, however, a large quantity goes out that would like to become deed but in fact does not become deed, remaining bound to the I and passing with it through death into the spiritual world.

You see, we experience, here on the other side (see diagram below) our future karma. Our future karma is experienced between willing and the deed. In Imaginative consciousness both are united, past and future karma, what weaves and lives within us, weaving on beneath the threshold above which lie the free deeds we can accomplish between birth and death. Between birth and death we live in freedom. Below this region of free willing, however, which actually has an existence only between birth and death, there weaves and lives karma. We perceive its effects out of the past if we can maintain our consciousness in our I and astral body in penetrating through the etheric body as far as to the physical body. On the other hand, we perceive our future karma if we can maintain ourselves in the region that lies between willing and the deed, if we can develop so much self-discipline through exercises that inwardly we can be as active in a feeling as, with the help of the body, we can be in a deed, if we can be active in spirit in feeling, if we therefore hold fast to the deed in the I.

Picture this vividly; one can be as enthusiastic, as inwardly enamored by something that springs from feeling as that which otherwise passes over into action; but one must withhold it: then it lights up in Imagination as future karma.

What I have described to you here is of course always present in the human being. Every morning on awaking man passes the region of his past karma; every evening on falling asleep he passes that of his future karma. Through a certain attentive awareness and without special training, the human being can grasp with presence of mind the past objectively, without, it is true, recognizing it as plainly as I have now described it. He can perceive it, however; it is there. There, too, is all that he bears within him as moral impulses of good and evil. Through this the human being actually learns to know himself better than when he becomes aware in the moment of awaking of the weaving of thought that forms him.

More difficult to grasp, however, is the perception of what lies between willing and the deed, of what one can withhold. There one learns to know oneself insofar as one has made oneself during his life. One learns to know the inner formation that one carries through death as future karma.

I wished to show you today how these things can be spoken about out of a living comprehension, how anthroposophy is not in the least exhausted in its images. Things can be described in a living way, and tomorrow I will go further in this study, going on to a still deeper grasp of the human being on the basis of what we have studied today.

Dritter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wir wollen in den Betrachtungen etwas fortfahren, die wir letzten Freitag und Sonnabend hier gepflogen haben, und ich möchte heute im besonderen Ihren Blick wenden auf eine Betrachtung des seelischen Lebens, wie sie sich ergibt, wenn man dieses seelische Leben ins Auge faßt von dem Gesichtspunkte der imaginativen Erkenntnis aus, den Sie ja kennen aus meiner Schrift «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?». Sie wissen, wir unterscheiden, aufsteigend von unserem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein aus, vier Erkenntnisstufen: diejenige Erkenntnisstufe, die uns eignet im heutigen gewöhnlichen Leben und in der heutigen gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft, jene Erkenntnisstufe, die das eigentliche Zeitbewußtsein ausmacht und die ja genannt wird im Sinne dieser Schrift «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» das gegenständliche Erkennen, und dann kommt man hinein in das Gebiet des Übersinnlichen durch die Erkenntnisstufen der Imagination, der Inspiration, der Intuition. Im gewöhnlichen gegenständlichen Erkennen ist es unmöglich, das Seelische zu betrachten. Das Seelische wird erlebt, und indem man es erlebt, entwickelt man die gegenständliche Erkenntnis. Aber eine eigentliche Erkenntnis kann ja nur gewonnen werden, wenn man das zu Erkennende objektiv vor sich hinstellen kann. Das kann man im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein mit dem seelischen Leben nicht. Man muß sich gewissermaßen um eine Stufe hinter das seelische Leben zurückziehen, damit es außerhalb von uns zu stehen kommt; dann kann man es betrachten. Das aber ergibt sich eben durch die imaginative Erkenntnis. Und zwar möchte ich Ihnen heute einfach schildern, was sich da für die Betrachtung herausstellt.

[ 2 ] Sie wissen, wir unterscheiden, indem wir den Menschen überblicken, den physischen Leib, den ätherischen oder Bildekräfteleib, der eigentlich eine Summe von Tätigkeiten ist, den astralischen Leib und das Ich zunächst, wenn wir bei dem stehenbleiben, was im gegenwärtigen Menschen west. Wenn wir nun das seelische Erleben heraufbringen nicht zur Erkenntnis, aber zum Bewußtsein, so unterscheiden wir es ja, indem wir es gewissermaßen im fluktuierenden Leben erfassen, in Denken, in Fühlen, in Wollen. Es ist das schon so, daß Denken, Fühlen und Wollen im gewöhnlichen Seelenleben ineinanderspielen. Sie können sich keinen Gedankenverlauf vorstellen, ohne daß Sie sich das Hineinspielen des Willens in den Gedankenverlauf mit vorstellen. Wie wir einen Gedanken zu dem anderen hinzufügen, wie wir einen Gedanken von dem anderen trennen, das ist durchaus eine in das Denkleben hineinstrebende Willenstätigkeit. Und wiederum, wenn auch zunächst, wie ich oftmals auseinandergesetzt habe, der Vorgang dunkel bleibt: wir wissen doch, daß, wenn wir als Menschen wollend sind, in unser Wollen als Impulse unsere Gedanken hineinspielen, so daß wir auch im gewöhnlichen Seelenleben durchaus nicht ein Wollen abgesondert für sich haben, sondern ein gedankendurchsetztes Wollen. Und erst recht fluten ineinander Gedanken, Willensimpulse und die eigentlichen Gefühle im Fühlen. Wir haben also durchaus das Seelenleben als ineinanderflutend, aber doch so, daß wir gedrängt sind durch Dinge, die wir heute immer außer acht lassen wollen, innerhalb dieses flutenden Seelenlebens zu unterscheiden Denken, Fühlen, Wollen. Wenn Sie meine «Philosophie der Freiheit» in die Hand nehmen, werden Sie sehen, wie man genötigt ist, das Denken reinlich loszulösen vom Fühlen und Wollen, aus dem Grunde, weil man nur durch eine Betrachtung des losgelösten Denkens zu einer Anschauung über die menschliche Freiheit kommt.

[ 3 ] Also indem wir einfach, ich möchte sagen, lebendig erfassen Denken, Fühlen, Wollen, erfassen wir zugleich das flutende, das webende Seelenleben. Und wenn wir das dann, was wir da in unmittelbarer Lebendigkeit erfassen, zusammenhalten mit demjenigen, was uns anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft erkennen lehrt über den Zusammenhang der einzelnen Glieder des Menschen, physischer Leib, Ätherleib, astralischer Leib und Ich, dann ergibt sich eben für ein imaginatives Erkennen das Folgende.

[ 4 ] Wir wissen ja, daß wir während des wachen Lebens, vom Aufwachen bis zum Einschlafen, in einem gewissen innigen Zusammenhange haben physischen Leib, Ätherleib, astralischen Leib und Ich. Wir wissen ferner, daß wir im schlafenden Zustande getrennt haben physischen Leib und Ätherleib auf der einen Seite, astralischen Leib und Ich auf der anderen Seite. Wenn auch die Ausdrucksweise durchaus nur approximativ richtig ist, daß man sagt: Ich und astralischer Leib trennen sich vom physischen Leibe und Ätherleibe - man kommt zunächst zu einer durchaus gültigen Vorstellung, wenn man eben diese Ausdrucksweise gebraucht. Das Ich mit dem astralischen Leibe ist vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen außer dem physischen Leibe und dem Ätherleibe.

[ 5 ] Sobald der Mensch nun zum imaginativen Erkennen vorrückt, wird er immer mehr und mehr in die Lage versetzt, genau ins Seelenauge, ins innere Anschauen zu fassen, was sich erleben läßt, ich möchte sagen, wie vorübergehend, im Status nascendi. Man hat es und muß es rasch erfassen, aber man kann es erfassen. Man hat vor sich, was in dem Momente des Aufwachens und Einschlafens besonders scharf beobachtet werden kann. Diese Momente des Einschlafens und Aufwachens können beobachtet werden für ein imaginatives Erkennen. Sie wissen ja, daß unter den Vorbereitungen, welche notwendig sind, um zu höheren Erkenntnissen zu kommen, von mir in dem vorhin angeführten Buche erwähnt worden ist die Heranerziehung einer gewissen Geistesgegenwart. Die Menschen reden ja im gewöhnlichen Leben so wenig von den Beobachtungen, die sich von der geistigen Welt her machen lassen, weil ihnen diese Geistesgegenwart fehlt. Würde diese Geistesgegenwart in ausgiebigerem Sinne bei den Menschen heranerzogen, so würden heute schon alle Menschen reden können von geistig-übersinnlichen Impressionen, denn sie drängen sich eigentlich im eminentesten Maße auf beim Einschlafen und Aufwachen, insbesondere beim Aufwachen. Nur weil so wenig heranerzogen wird, was Geistesgegenwart ist, deshalb bemerken die Menschen das nicht. Im Momente des Aufwachens tritt ja vor der Seele eine ganze Welt auf. Aber im Entstehen vergeht sie schon wiederum, und ehe sich die Menschen darauf besinnen, sie zu erfassen, ist sie fort. Daher können sie so wenig reden von dieser ganzen Welt, die da vor die Seele sich hinstellt und die wahrhaftig zum Begreifen des inneren Menschen von ganz besonderer Bedeutung ist.

[ 6 ] Was sich da vor die Seele hinstellt, wenn man wirklich dazu kommt, in Geistesgegenwart den Aufwachemoment zu ergreifen, das ist eine ganze Welt von flutenden Gedanken. Nichts Phantastisches braucht dabei zu sein. So wie man im chemischen Laboratorium beobachtet, mit derselben Seelenruhe und Besonnenheit kann man sie beobachten. Und dennoch ist diese flutende Gedankenwelt, die sehr genau zu unterscheiden ist vom bloßen Träumen, da. Das bloße Träumen spielt sich so ab, daß es erfüllt ist von Lebensreminiszenzen. Was sich da abspielt im Momente des Aufwachens, das sind nicht Lebensreminiszenzen. Sie sind sehr gut zu unterscheiden von Lebensreminiszenzen, diese flutenden Gedanken. Man kann sie sich in die Sprache des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins übersetzen, aber es sind im Grunde genommen fremdartige Gedanken, Gedanken, die wir sonst nicht erfahren können, wenn wir sie nicht in dem Momente, der entweder durch geisteswissenschaftliche Schulung in uns möglich gemacht ist, oder eben in diesem Momente des Aufwachens erfassen.

[ 7 ] Was erfassen wir da eigentlich? Nun, wir sind mit unserem Ich und unserem astralischen Leibe eingedrungen in den Ätherleib und in den physischen Leib. Was im Ätherleibe erlebt wird, wird allerdings so erlebt, daß es traumhaft ist. Und man lernt, indem. man dieses, wie ich es angedeutet habe, subtil in Geistesgegenwart beobachten lernt, man lernt wohl unterscheiden dieses Hindurchgehen durch den Ätherleib, in dem die Lebensreminiszenzen traumhaft auftreten, und dann, vor dem vollen Erwachen, vor den Eindrücken, die die Sinne nun haben nach dem Erwachen, das Hineingestelltsein in eine Welt, die durchaus eine Welt von webenden Gedanken ist, die aber nicht so erlebt wird wie die Traumgedanken, bei denen man genau weiß, man hat sie subjektivin sich. Die Gedanken, die ich jetzt meine, sie stellen sich wie ganz objektiv dar gegenüber dem eindringenden Ich und astralischen Menschen, und man merkt ganz genau: man muß passieren den Ätherleib; denn solange man den Ätherleib passiert, bleibt alles traumhaft. Man muß aber auch passieren den Abgrund, den Zwischenraum — möchte ich sagen, wenn ich mich recht uneigentlich, aber dadurch vielleicht deutlicher ausdrücke -, den Zwischenraum zwischen Ätherleib und physischem Leib, und schlüpft dann in das volle Ätherisch-Physische hinein, indem man aufwacht und die äußeren physischen Eindrücke der Sinne da sind. Sobald man in den physischen Leib hineingeschlüpft ist, sind eben die äußeren physischen Sinneseindrücke da. Was wir da an Gedankenweben objektiver Art erleben, spielt sich also durchaus zwischen dem Ätherleib und dem physischen Leib ab. Wir müssen in ihm also sehen eine Wechselwirkung des Ätherleibes und des physischen Leibes. So daß wir sagen können, wenn wir schematisch zeichnen: Wenn etwa das den physischen Leib darstellt (orange), das den Ätherleib (grün), so haben wir das lebendige Weben von physischem Leib und Ätherleib in den Gedanken, die wir da erfassen, und man kommt dann auf dem Wege einer solchen Beobachtung zu der Erkenntnis, daß sich zwischen unserem physischen und unserem Ätherleib, gleichgültig ob wir wachen, ob wir schlafen, immerzu Vorgänge abspielen, die eigentlich im webenden Gedankensein bestehen, die webendes Gedankensein zwischen unserem physischen Leib und unserem Ätherleib sind (gelb). So daß wir jetzt das erste Element des seelischen Lebens verobjektiviert erfaßt haben. Wir sehen in ihm ein Weben zwischen dem Ätherleib und dem physischen Leib.

[ 8 ] Dieses webende Gedankenleben kommt eigentlich so, wie es ist, im Wachzustande nicht zu unserem Bewußtsein. Es muß eben auf die Art, wie ich es geschildert habe, erfaßt werden. Wenn wir nämlich aufgewacht sind, schlüpfen wir mit unserem Ich und mit unserem astralischen Leib in unseren physischen Leib hinein. Ich und astralischer Leib in unserem mit dem Ätherleib durchdrungenen physischen Leib nehmen teil an dem Sinneswahrnehmungsleben. Sie werden, indem Sie das Sinneswahrnehmungsleben in sich haben, mit den äußeren Weltengedanken, die Sie sich bilden können an den Sinneswahrnehmungen, durchdrungen und haben dann die Stärke, dieses objektive Gedankenweben zu übertönen. An der Stelle, wo sonst die objektiven Gedanken weben, bilden wir also gewissermaßen aus der Substanz dieses Gedankenwebens heraus unsere alltäglichen Gedanken, die wir uns im Verkehre mit der Sinneswelt auf die eben angedeutete Weise ausbilden. Und ich kann sagen: In dieses objektive Gedankenweben hinein spielt dasjenige, was nun das subjektive Gedankenweben ist (hell), das das andere übertönt, das sich aber auch abspielt zwischen dem Ätherleib und dem physischen Leib. Wir leben in der Tat in diesem - wie ich schon sagte: uneigentlich, aber deshalb doch verständlich, muß ich es als Zwischenraum zwischen Ätherleib und physischem Leib bezeichnen —, wir leben in diesem Zwischenraum zwischen Ätherleib und physischem Leib, wenn wir mit der Seele selber Gedanken weben. Wir übertönen die objektiven Gedanken, die im schlafenden und wachenden Zustand immer vorhanden sind, mit unserem subjektiven Gedankenweben. Aber gewissermaßen in derselben Region unseres menschlichen Wesens ist beides vorhanden: das objektive Gedankenweben und das subjektive Gedankenweben.

[ 9 ] Was hat das objektive Gedankenweben für eine Bedeutung? Das objektive Gedankenweben, wenn es wahrgenommen wird, wenn wirklich eintritt, was ich geschildert habe als das geistesgegenwärtige Ergreifen des Momentes des Aufwachens, dieses objektive Gedankenweben wird nicht als bloßes Gedankliches erfaßt, sondern es wird erfaßt als dasjenige, was in uns lebt als die Kräfte des Wachstums, als die Kräfte des Lebens überhaupt. Diese Kräfte des Lebens sind verbunden mit dem Gedankenweben. Sie durchsetzen dann den Ather- oder Lebensleib nach innen; sie konfigurieren nach außen den physischen Leib. Wir nehmen das, was wir als objektives Gedankenweben da wahrnehmen im geistesgegenwärtigen Erfassen des Aufwachemomentes, durchaus wahr als Gedankenweben nach der einen Seite und als Wachstums-, als Ernährungstätigkeit auf der anderen Seite. Was in dieser Art in uns ist, wir nehmen es als ein innerliches Weben wahr, das aber durchaus ein Lebendiges darstellt. Das Denken verliert gewissermaßen seine Bildhaftigkeit und Abstraktheit. Es verliert auch alles das, was scharfe Konturen sind. Es wird fluktuierendes Denken, aber es ist deutlich als Denken zu erkennen. Das Weltendenken webt in uns, und wir erfahren, wie das Weltendenken in uns webt und wie wir mit unserem subjektiven Denken untertauchen in dieses Weltendenken. So haben wir das Seelische in einem gewissen Gebiete erfaßt.

[ 10 ] Gehen wir jetzt weiter im geistesgegenwärtigen Erfassen des Aufwachemomentes, so finden wir das Folgende. Wir können, wenn wir in der Lage sind, Traumhaftes zu erleben beim Passieren des Ätherleibes, wenn wir also mit dem Ich und dem astralischen Leibe den Ätherleib passieren, wir können dann bildhaft das Traumhafte uns vergegenwärtigen. Die Bilder des Traumes müssen aufhören in dem Augenblicke, wo wir aufwachen, sonst würden wir den Traum in das gewöhnliche bewußte Wacherleben hineinnehmen und wachende Träumer sein, wodurch wir ja die Besonnenheit verlieren würden. Die Träume als solche müssen aufhören. Aber wer mit Bewußtsein die Träume erlebt, wer also jene Geistesgegenwart bis zurück zum Erleben der Träume hat — denn das gewöhnliche Erleben der Träume ist ein Reminiszenzerleben, ist eigentlich ein Nachher-Erinnern an die Träume; das ist ja das gewöhnliche Gewahrwerden des Traumes, daß man ihn eigentlich erst wie eine Reminiszenz erfaßt, wenn er abgelaufen ist —, also wenn der Traum erlebt wird beim Durchfluten des Ätherleibes, nicht erst nachher im Erinnern, wo er in Kürze erfaßt werden kann, wie er gewöhnlich erfaßt wird, wenn man ihn also erfaßt während er ist, also gerade beim Durchdringen durch den Ätherleib, dann erweist er sich wie etwas Regsames, wie etwas, das man so erlebt wie Wesenhaftes, in dem man sich fühlt. Das Bildhafte hört auf, bloß Bildhaftes zu sein. Man bekommt das Erlebnis, daß man im Bilde drinnen ist. Dadurch aber, daß man dieses Erlebnis bekommt, daß man im Bilde drinnen ist, daß man also mit dem Seelischen sich regt, wie man sonst im wachen Leben mit dem Körperlichen in der Beinbewegung, in der Handbewegung sich regt - so wird nämlich der Traum: er wird aktiv, er wird so, daß man ihn erlebt, wie man eben Arm- und Beinbewegungen oder Kopfbewegungen und dergleichen erlebt —, wenn man das erlebt, wenn man dieses Erfassen des Traumhaften wie etwas Wesenhaftes erlebt, dann schließt sich gerade beim weiteren Fortgang, beim Aufwachen, an dieses Erlebnis ein weiteres an: daß diese Regsamkeit, die man da im Traume erlebt, in der man nunmehr drinnensteht als in etwas Gegenwärtigem, daß diese untertaucht in unsere Leiblichkeit. Geradeso wie wir beim Denken fühlen: Wir dringen bis zu der Grenze unseres physischen Leibes, wo die Sinnesorgane sind, und nehmen die Sinneseindrücke auf mit dem Denken, so fühlen wir, wie wir in uns untertauchen mit demjenigen, was im Traume als innerliche Regsamkeit erlebt wird. Was man da erlebt im Momente des Aufwachens — oder eigentlich vor dem Momente des Aufwachens, wenn man im Traume drinnen ist, wenn man durchaus noch außer seinem physischen Leibe, aber schon im Ätherleib ist, beziehungsweise gerade hineingeht in seinen Ätherleib -, das taucht unter in unsere Organisation. Und ist man so weit, daß man dieses Untertauchen als Erlebnis vor sich hat, dann weiß man auch, was nun wird mit dem Untergetauchten: das Untergetauchte strahlt wieder zurück in unser waches Bewußtsein, und zwar strahlt es zurück als Gefühl, als Fühlen. Die Gefühle sind in unsere Organisation untergetauchte Träume.

[ 11 ] Wenn wir das, was webend ist in der Außenwelt, in diesem traumwebhaften Zustande wahrnehmen, sind es Träume. Wenn die Träume untertauchen in unsere Organisation und von innen heraus bewußt werden, erleben wir sie als Gefühle. Wir erleben also die Gefühle dadurch, daß dasjenige in uns, was in unserem astralischen Leib ist, untertaucht in unseren Ätherleib und dann weiter in unsere physische Organisation, nicht bis zu den Sinnen hin, nicht also bis zu der PeriPherie der Organisation, sondern nur in die innere Organisation hinein. Dann, wenn man dies erfaßt hat, zunächst durch imaginative Erkenntnis besonders deutlich erschaut hat im Momente des Aufwachens, dann bekommt man auch die innere Kraft, es fortwährend zu schauen. Wir träumen nämlich während des wachen Lebens fortwährend. Wir überleuchten nur das Träumen mit unserem denkenden Bewußtsein, mit dem Vorstellungsleben. Wer unter die Oberfläche des Vorstellungslebens blicken kann — und man schult sich zu diesem Blicken dadurch, daß man eben geistesgegenwärtig erfaßt den Moment des Träumens selber -, wer sich so geschult hat, daß er das beim Aufwachen erfassen kann, was ich bezeichnet habe, der kann dann auch unter der Oberfläche des lichtvollen Vorstellungslebens das den ganzen Tag hindurch dauernde Träumen erleben, das aber nicht als Träumen erlebt wird, sondern das immer sofort untertaucht in unsere Organisation und als Gefühlswelt zurückstrahlt. Und er weiß dann: Was das Fühlen ist, es spielt sich ab zwischen dem astralischen Leib, den ich hier schematisch so zeichne (Zeichnung S. 51, hell), und dem Ätherleib. Es drückt sich natürlich im physischen Leib aus (orange). So daß der eigentliche Ursprung des Fühlens zwischen dem astralischen Leib und dem Ätherleib liegt (rot). So wie der physische Leib und der Ätherleib in lebendiger Wechselwirkung ineinanderwirken müssen zum Gedankenleben, so müssen ätherischer Leib und astralischer Leib in lebendiger Wechselwirkung sein zum Gefühlsleben. Wenn wir wachend sind, erleben wir dieses lebendige Wechselspiel unseres ineinandergedrängten Ätherleibes und astralischen Leibes als unser Fühlen. Wenn wir schlafen, erleben wir, was der nunmehr außen lebende astralische Leib in der äußeren Ätherwelt erlebt, als die Bilder des Traumes, die nun während des ganzen Schlafens vorhanden sind, aber eben nicht wahrgenommen werden im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein, sondern nur eben reminiszenzenhaft in jenen Fragmenten, die das gewöhnliche Traumleben bilden.

[ 12 ] Sie sehen daraus, daß wir, wenn wir das Seelenleben erfassen wollen, noch zwischen die Glieder der menschlichen Organisation hineinblicken müssen. Wir denken uns das Seelenleben als flutendes Denken, Fühlen, Wollen. Von letzterem wollen wir gleich sprechen. Aber wir erfassen es objektiv, indem wir gewissermaßen in die Zwischenräume zwischen diese vier Glieder hineinschauen, zwischen den physischen Leib und Ätherleib, und Ätherleib und astralischen Leib.

[ 13 ] Was sich im Wollen ausdrückt, das entzieht sich ja, wie ich öfters von anderen Gesichtspunkten aus hier ausgeführt habe, durchaus der Betrachtung des gewöhnlichen Wachlebens, des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins. In diesem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein sind vorhanden die Vorstellungen, nach denen wir unser Wollen orientieren, die Gefühle, die wir entwickeln in Anlehnung an die Vorstellungen als Motive für unser Wollen; aber wie das, was da als der Vorstellungsinhalt unseres Wollens klar in unserem Bewußtsein liegt, hinunterspielt, wenn ich nur die Arme bewege zum Wollen, was da eigentlich vorgeht, das wird uns im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht gegeben. In dem Augenblicke, wo der Geistesforscher die Imagination in sich heranzieht und dazu kommt, die Natur des Denkens, des Fühlens so anzusehen, wie ich gesagt habe, dann kann er auch dahin gelangen, als etwas in das Bewußtsein Hereinfallendes die menschlichen Erlebnisse zu haben, die zwischen dem Einschlafen und dem Aufwachen sich abspielen. Denn in den Übungen zur Imagination werden Ich und astralischer Leib erkraftet. Sie werden in sich stärker, sie lernen sich erleben. Im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein hat man eben nicht das wirkliche Ich. Wie hat man das Ich im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein? Sehen Sie, immer wiederum muß ich diesen Vergleich machen: Wenn man das Leben in der Erinnerung zurück anschaut, so stellt es sich scheinbar als eine geschlossene Strömung dar. Die ist es aber doch nicht, sondern wir müßten eigentlich, indem wir jetzt leben, den heutigen Tag überblicken bis zum Aufwachen, haben dann eine leere Stelle, daran schließt sich der Bewußtseinsinhalt des gestrigen Tages und so weiter fort. Was wir da in der Rückerinnerung beobachten, das trägt allerdings in sich auch diejenigen Zustände, die wir nicht bewußt durchlebt haben, die also in dem präsenten Inhalt des Bewußtseins nicht drinnen sind. Aber sie sind auf andere Art drinnen. Ein Mensch, der gar nicht schlafen würde - wenn ich das hypothetisch anführen darf -, der würde eine ganz zerstörte Rückerinnerung haben. Die Rückerinnerung würde ihn gewissermaßen blenden. Er würde alles das, was er in der Rückerinnerung vor sein Bewußtsein hinstellt, als etwas ihm ganz Fremdes, blendend Glänzendes erleben. Er würde überwältigt sein davon, und er würde sich vollständig ausschalten müssen. Er käme gar nicht dazu, sich selber in sich zu erfühlen. Nur dadurch, daß sich die Schlafzustände hineinstellen in die Rückerinnerung, wird die Rückerinnerung abgeblendet. Wir sind in der Lage, sie auszuhalten. Denn dadurch wird es möglich, daß wir uns selbst behaupten gegenüber unserer Erinnerung. Lediglich dem Umstande, daß wir schlafen, haben wir unsere Selbstbehauptung in der Erinnerung zu verdanken. Was ich jetzt sage, könnte schon durch empirische Beobachtung der menschlichen Lebensläufe in vergleichender Weise gut konstatiert werden.

[ 14 ] Aber geradeso wie wir da die innere Aktivität erfühlen in der Rückerinnerung, so erfühlen wir ja eigentlich unser Ich aus unserem gesamten Organismus heraus. Wir erfühlen es so, wie wir die Schlafzustände als, ich möchte sagen, die finsteren Räume im Erinnerungsfortgang wahrnehmen. Wir nehmen das Ich nicht direkt wahr für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein, sondern wir nehmen es nur wahr, wie wir die Schlafzustände wahrnehmen. Aber indem wir das imaginative Bewußtsein erwerben, tritt dieses Ich wirklich auf, und es ist willensartiger Natur. Und wir merken: Was in uns ein Gefühl, das in sich schließt, mit der Welt sympathisch oder antipathisch zu fühlen, was das in uns aktiviert zum Wollen, das spielt sich in einem ähnlichen Prozesse ab, wie er sich abspielt zwischen dem Wachen und dem Hineinkommen in das Schlafen. Man kann das wiederum geistesgegenwärtig beobachten, wenn man ebenso wie für das Aufwachen für das Einschlafen dieselben Eigenschaften entwickelt, von denen ich gesprochen habe. Da merkt man beim Einschlafen, daß man hineinträgt in den Schlafzustand, was ausstrahlt, als Aktivität ausstrahlt aus unserem Gefühlsleben, und was hineinstrahlt in die Außenwelt, und man lernt dann erkennen, wie man jedesmal, wenn man sich wirklich willensmäßig entwickelt, untertaucht jetzt in einen ähnlichen Zustand, wie man untertaucht in den Schlafzustand. In ein inneres Schlafen taucht man ein. Was einmal vorgeht beim Einschlafen, wo dann das Ich mit dem astralischen Leib herausrückt aus physischem Leib und Ätherleib, das tritt jedesmal innerlich ein beim Wollen.

[ 15 ] Natürlich müssen Sie sich darüber klar sein, daß das, was ich Ihnen da schildere, viel schwieriger zu ergreifen ist als das, was ich vorhin geschildert habe, denn der Moment des Einschlafens ist eben geistesgegenwärtig meistens noch schwieriger zu erfassen als der des Aufwachens. Nach dem Aufwachen sind wir wach; da haben wir wenigstens die Anlehnung an die Reminiszenzen. Beim Einschlafen müssen wir den Wachzustand noch in das Schlafen hinein fortsetzen, wenn wir zu einer Beobachtung kommen wollen. Aber der Mensch schläft eben meistens ein; er sendet nicht hinein in das Einschlafen die Aktivität des Fühlens. Kann er sie aber da hinein fortsetzen, was eben durch Schulung in imaginativer Erkenntnis geschieht, dann merkt er, daß tatsächlich im Wollen ein Untertauchen in dasselbe Element ist, in das wir untertauchen, wenn wir einschlafen. Wir werden tatsächlich im Wollen von unserer Organisation frei. Wir verbinden uns mit der realen Objektivität. So wie wir beim Aufwachen durch unseren Ätherleib einziehen, durch unseren physischen Leib und bis in die Sinnesregion, also bis an die Peripherie des Leibes kommen, gewissermaßen von dem ganzen Leib Besitz ergreifen, den ganzen Leib durchtränken, so senden wir wiederum im Fühlen in den Leib zurück, indem wir innerlich untertauchen, unsere Träume; sie werden eben Gefühle. Aber wenn wir jetzt nicht im Leibe bleiben, sondern, ohne daß wir an die Peripherie des Leibes gehen, innerlich geistig aus dem Leibe herausgehen, dann kommen wir zum Wollen. So daß sich das Wollen tatsächlich eigentlich unabhängig vom Leibe vollzieht. Ich weiß, daß damit viel gesagt wird, aber ich muß das auch darstellen, weil es eine Realität ist. Und in dem Erfassen dessen kommen wir dazu, nun einzusehen, daß — wenn wir nun hier das Ich haben (siehe Zeichnung Seite 51, blau) — das Wollen sich abspielt zwischen dem astralischen Leib und dem Ich (lila).

[ 16 ] Wir können also sagen: Wir gliedern den Menschen in physischen Leib, in Ätherleib oder Bildekräfteleib, in astralischen Leib und in Ich. Zwischen dem physischen Leib und dem Ätherleib spielt sich seelisch das Denken ab. Zwischen dem Ätherleib und dem astralischen Leib spielt sich seelisch das Fühlen ab. Zwischen dem astralischen Leib und dem Ich spielt sich seelisch das Wollen ab. Indem wir an die Peripherie des physischen Leibes kommen, haben wir die Sinneswahrnehmung. Indem wir auf dem Wege durch unser Ich herauskommen aus uns, unsere ganze Organisation in die Außenwelt hineinstellen, wird das Wollen zur Handlung, dem anderen Pol der Sinneswahrnehmung (siehe Schema Seite 62).

[ 17 ] Auf diese Weise gelangt man zu einem objektiven Erfassen dessen, was subjektiv im flutenden Denken, Fühlen und Wollen erlebt wird. So verwandelt sich das Erleben in das Erkennen. Alle Psychologie, welche das flutende Denken, Fühlen und Wollen sonst auf eine andere Weise erfassen will, bleibt formal, weil sie nicht an die Realität herandringt. An die Realität kann für das seelische Erleben nur die imaginative Erkenntnis herandringen.

[ 18 ] Fassen wir jetzt einmal ins Auge, was sich uns gewissermaßen wie eine Begleiterscheinung unserer ganzen Betrachtungen ergeben hat. Wir sagten: Man kann durch geistesgegenwärtige Betrachtung im Moment des Aufwachens, wenn man durchgeschlüpft ist durch den Ätherleib, Gedankenweben, das objektiver Art ist, sehen. Man nimmt dieses objektive Gedankenweben zunächst wahr. Ich sagte, man kann es von den Träumen und auch vom alltäglichen Gedankenleben, vom subjektiven Gedankenleben ganz gut unterscheiden, denn es ist verbunden mit dem Wachstum, mit dem Werden. Es ist eigentlich eine reale Organisation. Faßt man es aber auf, was da webt, was man, wenn man es durchschaut, als Gedankenweben wahrnimmt, wenn man es, ich möchte sagen, anfühlt, innerlich antastet, so nimmt man es als Wachstumskraft, als Ernährungskraft und so weiter, als den werdenden Menschen wahr. Es ist etwas, was zunächst fremd ist, aber Gedankenwelt ist. Wenn man es nun genauer studieren kann, so ist es ja das innerliche Weben von Gedanken an uns selbst. Wir erfassen es an der Peripherie unseres physischen Leibes; bevor wir an das Sinneswahrnehmen herankommen, erfassen wir es. Wenn wir es genauer verstehen lernen, wenn wir uns in seine Fremdheit gegenüber unserem subjektiven Denken einleben, dann erkennen wir es, dann erkennen wir es als das, was wir mitgebracht haben durch unsere Geburt aus früheren Erlebnissen, aus vorgeburtlichen respektive vor der Konzeption liegenden Erlebnissen. Und es wird für uns etwas objektiv Gegenständliches das Geistige, das unseren ganzen Organismus zusammenbringt. Der Präexistenzgedanke gewinnt Objektivität, wird zum objektiven Anschauen. Wir können mit innerem Erfassen sagen: Wir sind aus der Welt des Geistes heraus durch Gedanken gewoben. Die subjektiven Gedanken, die wir dazufügen, sie stehen im Bereiche unserer Freiheit. Diejenigen Gedanken, die wir da erblicken, sie bilden uns, sie bauen unseren Leib aus dem Gedankenweben heraus auf. Sie sind unser vergangenes Karma (siehe Tafel 6 Schema Seite 62). Also: Ehe wir an die Sinneswahrnehmungen herankommen, nehmen wir unser vergangenes Karma wahr.

[ 19 ] Und wenn wir einschlafen, so hat dieses Einschlafen für denjenigen, der in objektiver Erkenntnis lebt, etwas Ähnliches mit dem Wollen. Wenn das Wollen zur vollständigen Bewußtheit gebracht wird, merkt man ganz deutlich: Man schläft in den eigenen Organismus hinein. So wie sonst die Träume hinuntergehen, gehen in unsere Organisation die Wollensmotive hinein. Man schläft in den Organismus hinein. Man lernt unterscheiden dieses Hineinschlafen in den Organismus, das sich zunächst auslebt in unseren gewöhnlichen Handlungen - die sind eben äußerlich sich vollziehend, wir vollziehen sie zwischen dem Aufwachen und Einschlafen -; aber nicht alles das, was in unserem Gefühlsleben drinnen lebt, lebt sich in diese Handlungen hinein. Wir vollbringen ja auch das Leben zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen. Und was wir sonst in die Handlungen hineindrängen würden, drängen wir ja aus uns durch denselben Vorgang im Einschlafen hinaus. Eine ganze Summe von Willensimpulsen drängen wir hinaus in die rein geistige Welt, in der wir uns befinden zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen. Willensimpulse, die in unser geistiges Sein übergehen, die wir nur hegen zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen: lernen wir sie durch imaginative Erkenntnis beobachten, so nehmen wir in ihnen wahr, was an Handlungsorientierung vorhanden bleibt über den Tod hinaus, was mit uns geht über den Tod hinaus.

[ 20 ] Zwischen dem astralischen Leib und dem Ich entwickelt sich das Wollen. Das Wollen wird Handlung, indem es so weit nach der Außenwelt geht, bis es an den Ort kommt, woher sonst die Sinneseindrücke kommen. Aber im Einschlafen geht ja eine ganze Menge hinaus, was wie Handlung werden will, aber eben nicht Handlung wird, sondern mit dem Ich verbunden bleibt, indem das Ich durch den Tod in die geistige Welt übergeht.

[ 21 ] Sie sehen, wir erleben hier auf der anderen Seite unser werdendes Karma (siehe Schema Seite 62). Zwischen dem Wollen und der Handlung erleben wir unser werdendes Karma. Beide schließen sich dann im imaginativen Bewußtsein zusammen: das vergangene und das werdende Karma, das, was in uns webt und lebt und so sich gibt, daß es weiterwebt unter der Schwelle, über welcher unsere freien Handlungen liegen, die wir ausleben können zwischen Geburt und Tod. Zwischen Geburt und Tod leben wir in der Freiheit. Aber es webt und lebt unter dieser Region des freien Willens, Wollens, die eigentlich nur ein Dasein hat zwischen Geburt und Tod, das Karma, dessen aus der Vergangenheit kommende Wirkungen wir wahrnehmen, wenn wir uns aufhalten können mit unserem Ich und unserem astralischen Leibe im Ätherleib gerade beim Durchbrechen bis zum physischen Leibe hin. Und wiederum auf der anderen Seite nehmen wir unser werdendes Karma wahr, wenn wir uns aufhalten können in der Region, die gerade liegt zwischen dem Wollen und dem Handeln, und wenn wir soviel Selbstzucht durch Übung entwickeln können, daß wir innerlich uns ebenso aktivieren können in einem Gefühl, wie wir uns, ich möchte sagen, indem wir den Leib zu Hilfe nehmen, aktivieren in der Handlung; wenn wir uns im Geiste aktivieren können im Gefühl, wenn wir also eine Handlung festhalten im Ich.

[ 22 ] Stellen Sie sich das lebhaft vor: Man kann so enthusiasmiert sein, so innerlich eingenommen sein für irgend etwas, was aus dem Gefühle sprießt, wie das, was sonst in die Handlung übergeht; aber man muß es zurückhalten: dann leuchtet es auf in der Imagination als das werdende Karma.

[ 23 ] Was ich Ihnen hier geschildert habe, ist natürlich im Menschen immer vorhanden. Der Mensch passiert mit jedem Aufwachen, jeden Morgen beim Aufwachen die Region seines vergangenen Karmas; er passiert jeden Abend beim Einschlafen die Region seines werdenden Karmas. Der Mensch kann durch eine gewisse Aufmerksamkeit auch ohne besondere Schulung in Geistesgegenwärtigkeit erfassen das vergangene Objektive, ohne daß er es freilich so deutlich erkennt, wie ich es jetzt geschildert habe. Er kann es aber wahrnehmen; es ist da. Und es ist dann da alles das, was er in seinen sittlichen Impulsen in sich trägt im Guten und im Schlechten. Durch dieses lernt sich eigentlich der Mensch besser kennen, als wenn er im Momente des Aufwachens dieses Gedankenweben, das ihn selbst bildet, gewahr wird.

[ 24 ] Aber schon schreckhafter ist das Wahrnehmen dessen, was zwischen dem Wollen und der Handlung liegt, was man zurückhalten kann. Da lernt man sich kennen insoweit, als man sich selber gemacht hat während dieses Lebens. Da lernt man kennen, was man als innere Artung durch den Tod hinausträgt als werdendes Karma.

[ 25 ] Ich wollte Ihnen heute zeigen, wie man über diese Dinge in lebendiger Erfassung reden kann, wie durchaus Anthroposophie sich nicht erschöpft in einer Schematik, sondern wie die Dinge lebendig geschildert werden können, und werde morgen dann in dieser Betrachtung weiter fortfahren, indem ich übergehen werde zu einer noch tieferen Erfassung der menschlichen Wesenheit auf Grundlage des heute Ausgeführten.

Third Lecture

[ 1 ] We would like to continue with the reflections we began here last Friday and Saturday, and today I would like to draw your attention in particular to a consideration of the soul life as it appears when viewed from the perspective of imaginative knowledge, which you are familiar with from my book How Does One Gain Knowledge of the Higher Worlds? You know that, ascending from our ordinary consciousness, we distinguish four stages of knowledge: the stage of knowledge that is proper to our ordinary life today and to ordinary science today, the stage of knowledge that constitutes actual time consciousness and is called, in the sense of this book, “How to Know Higher Worlds,” objective knowledge, and then one enters the realm of the supersensible through the stages of knowledge of imagination, inspiration, and intuition. In ordinary objective knowledge, it is impossible to contemplate the soul. The soul is experienced, and in experiencing it, one develops objective knowledge. But true knowledge can only be gained if one can objectively place what is to be known before oneself. This is not possible in ordinary consciousness with the soul life. One must, as it were, withdraw one step behind the soul life so that it stands outside of us; then one can observe it. But this is precisely what imaginative cognition brings about. And today I would simply like to describe to you what emerges for observation.

[ 2 ] You know that when we look at human beings, we distinguish between the physical body, the etheric or formative body, which is actually a sum of activities, the astral body, and the I, if we remain with what is present in the human being today. If we now bring soul experience up not to knowledge but to consciousness, we distinguish it by grasping it, as it were, in the fluctuating life, in thinking, feeling, and willing. It is already the case that thinking, feeling, and willing interact in ordinary soul life. You cannot imagine a train of thought without imagining the interplay of the will in the train of thought. How we add one thought to another, how we separate one thought from another, is entirely an activity of the will striving into the life of thinking. And again, even if the process remains obscure at first, as I have often explained, we know that when we are willing as human beings, our thoughts play into our will as impulses, so that even in ordinary soul life we do not have a will that is separate from ourselves, but rather a will that is permeated by thought. And even more so, thoughts, impulses of the will, and the actual feelings flood into one another in feeling. So we have soul life as something that floods into one another, but in such a way that we are compelled by things that we always want to ignore today to distinguish between thinking, feeling, and willing within this flooding soul life. If you pick up my Philosophy of Freedom, you will see how one is compelled to separate thinking cleanly from feeling and willing, for the reason that only by considering detached thinking can one arrive at a view of human freedom.

[ 3 ] So by simply, I would say, vividly grasping thinking, feeling, and willing, we simultaneously grasp the flowing, weaving soul life. And when we then hold together what we grasp in immediate liveliness with what anthroposophical spiritual science teaches us about the connection between the individual members of the human being, the physical body, the etheric body, the astral body, and the I, then the following emerges for imaginative cognition.

[ 4 ] We know that during our waking life, from the moment we wake up to the moment we fall asleep, our physical body, etheric body, astral body, and I are in a certain intimate relationship. We also know that in the sleeping state, our physical body and etheric body are separated on the one hand, and our astral body and I on the other. Even if the expression is only approximately correct when we say that I and the astral body separate from the physical body and etheric body, we arrive at a perfectly valid idea when we use this expression. From the moment we fall asleep until we wake up, the I with the astral body is outside the physical body and etheric body.

[ 5 ] As soon as the human being advances to imaginative cognition, he becomes more and more able to grasp precisely in the soul's eye, in inner contemplation, what can be experienced, I would say, as temporary, in the status nascendi. One has it and must grasp it quickly, but one can grasp it. One has before oneself what can be observed particularly clearly in the moments of waking and falling asleep. These moments of falling asleep and waking up can be observed for imaginative cognition. You know that among the preparations necessary for attaining higher knowledge, I mentioned in the book I mentioned earlier the cultivation of a certain presence of mind. In ordinary life, people talk so little about the observations that can be made of the spiritual world because they lack this presence of mind. If this presence of mind were cultivated more extensively in people, then all people would already be able to talk about spiritual, supersensible impressions, because they actually impose themselves to the highest degree when falling asleep and waking up, especially when waking up. It is only because so little is cultivated in terms of presence of mind that people do not notice this. At the moment of waking up, a whole world appears before the soul. But as it emerges, it already passes away, and before people can think about grasping it, it is gone. That is why they can say so little about this whole world that stands before the soul and is truly of special importance for understanding the inner human being.

[ 6 ] What appears before the soul when one really manages to seize the moment of awakening with presence of mind is a whole world of flooding thoughts. There is nothing fantastical about it. It can be observed with the same calmness and prudence as one would observe in a chemical laboratory. And yet this flood of thoughts, which is very different from mere dreaming, is there. Mere dreaming is filled with reminiscences of life. What happens in the moment of awakening is not a reminiscence of life. These flood of thoughts can be clearly distinguished from reminiscences of life. They can be translated into the language of ordinary consciousness, but they are basically strange thoughts, thoughts that we cannot otherwise experience unless we grasp them in the moment made possible either by spiritual scientific training or in this moment of awakening.

[ 7 ] What are we actually perceiving? Well, we have entered the etheric body and the physical body with our ego and our astral body. However, what is experienced in the etheric body is experienced in a dreamlike way. And one learns by observing this, as I have indicated, in a subtle way with presence of mind. One learns to distinguish between this passing through the etheric body, in which the reminiscences of life appear in a dreamlike form, and then, before full awakening, before the impressions that the senses now have after awakening, being placed in a world that is indeed a world of weaving thoughts, but which is not experienced like dream thoughts, where one knows exactly that one has them subjectively within oneself. The thoughts I mean now appear completely objective in relation to the penetrating I and the astral human being, and one realizes very clearly: one must pass through the etheric body; for as long as one passes through the etheric body, everything remains dreamlike. But one must also pass through the abyss, the space in between — if I may express myself somewhat inaccurately, but perhaps more clearly — the space between the etheric body and the physical body, and then slip into the full etheric-physical realm by waking up and experiencing the external physical impressions of the senses. As soon as one slips into the physical body, the external physical impressions of the senses are there. What we experience there as objective thought patterns therefore takes place entirely between the etheric body and the physical body. We must therefore see in it an interaction between the etheric body and the physical body. So that we can say, if we draw a diagram: if this represents the physical body (orange) and this the etheric body (green), then we have the living weaving of the physical body and the etheric body in the thoughts we perceive there, And through such observation we come to the realization that between our physical body and our etheric body, whether we are awake or asleep, there are always processes taking place that actually consist of weaving thoughts, that are weaving thoughts between our physical body and our etheric body (yellow). So now we have objectively grasped the first element of soul life. We see in it a weaving between the etheric body and the physical body.

[ 8 ] This weaving thought life does not actually come to our consciousness in the waking state as it is. It must be grasped in the way I have described. For when we wake up, we slip into our physical body with our ego and our astral body. I and my astral body, in our physical body permeated by the etheric body, participate in sensory perception. By having sensory perception within us, we become permeated with the external world thoughts that we can form from our sensory perceptions, and then have the strength to drown out this objective web of thoughts. At the point where objective thoughts would otherwise weave, we form, as it were, our everyday thoughts out of the substance of this web of thoughts, which we develop in our interactions with the sensory world in the manner just described. And I can say: into this objective web of thoughts plays that which is now the subjective web of thoughts (light), which drowns out the other, but which also takes place between the etheric body and the physical body. We live in this—as I have already said, improperly, but nevertheless understandably, I must call it the space between the etheric body and the physical body—we live in this space between the etheric body and the physical body when we weave thoughts with the soul itself. We drown out the objective thoughts that are always present in the sleeping and waking states with our subjective weaving of thoughts. But in a sense, both are present in the same region of our human being: the objective weaving of thoughts and the subjective weaving of thoughts.

[ 9 ] What is the significance of the objective weaving of thoughts? When the objective web of thoughts is perceived, when what I have described as the mental grasping of the moment of awakening actually occurs, this objective web of thoughts is not perceived as mere thought, but as that which lives within us as the forces of growth, as the forces of life itself. These forces of life are connected with thought-weaving. They then permeate the etheric or life body inwardly; they configure the physical body outwardly. We perceive what we perceive as objective thought-weaving in the moment of awakening as thought-weaving on the one hand and as growth and nourishment on the other. What is within us in this way, we perceive as an inner weaving, but one that is definitely alive. Thinking loses its pictorial and abstract nature, so to speak. It also loses everything that has sharp contours. It becomes fluctuating thinking, but it is clearly recognizable as thinking. World thinking weaves within us, and we experience how world thinking weaves within us and how we submerge into this world thinking with our subjective thinking. In this way, we have grasped the soul in a certain area.

[ 10 ] If we now continue with our mindful perception of the moment of awakening, we find the following. If we are able to experience dream images as we pass through the etheric body, that is, when we pass through the etheric body with our ego and astral body, we can then visualize the dream images. The images of the dream must cease at the moment we wake up, otherwise we would carry the dream into our ordinary conscious waking life and be waking dreamers, which would cause us to lose our composure. Dreams as such must cease. But those who experience dreams consciously, who have that presence of mind back to the experience of dreams — for the ordinary experience of dreams is a reminiscence, is actually a subsequent recollection of dreams; that is the ordinary awareness of the dream, that one actually only grasps it as a reminiscence when it has passed — that is, when the dream is experienced as it flows through the etheric body, not only afterwards in memory, where it can be grasped briefly, as it is usually grasped, but when it is grasped while it is happening, that is, precisely as it passes through the etheric body, then it appears as something lively, something that is experienced as something essential, in which one feels oneself. The pictorial ceases to be merely pictorial. One has the experience of being inside the picture. But through having this experience of being inside the picture, of moving with the soul as one otherwise moves with the body in waking life in the movement of the legs or hands, the dream becomes active, it becomes such that one experiences it as one experiences the movements of the arms and legs or the movements of the head and the like — when one experiences this, when one experiences this grasping of the dreamlike as something active, it becomes active, it becomes such that one experiences it as one experiences the movements of the arms and legs or the movements of the head and the like — when one experiences this, when one experiences this grasping of the dreamlike as something active, it becomes active, it becomes such that one experiences it as one experiences the movements of the arms and legs or the movements of the head and the like — it becomes active, it becomes such that one experiences it as one experiences arm and leg movements or head movements and the like—when one experiences this, when one experiences this grasping of the dreamlike as something essential, then, as one continues, as one awakens, another experience follows this one: that this liveliness that one experiences in the dream, in which one now stands as if in something present, that this submerges into our physicality. Just as we feel when we think: we penetrate to the boundary of our physical body, where the sense organs are, and take in sensory impressions with our thinking, so we feel ourselves sinking into ourselves with what is experienced in the dream as inner activity. What we experience in the moment of awakening—or actually before the moment of awakening, when we are still in the dream, when we are still outside our physical body but already in our etheric body, or rather just entering our etheric body—submerges into our organization. And when you have reached the point where you experience this submerging, then you also know what happens to what has been submerged: it radiates back into your waking consciousness, and it radiates back as a feeling, as emotion. Emotions are dreams that have been submerged into our organization.