Cosmosophy I

GA 207

2 October 1921, Dornach

Lecture V

I would like, in order to be aware of the connections, to recapitulate briefly what we have been studying during recent days in relation to cognition of the soul-spiritual life of the human being. In particular I would like to refer to the most important things in what has been said as a sort of prelude to what has still to be added as a temporary conclusion to these studies. Today I shall speak more of the results; I have already explained the process of observation in the past few days.

We have seen that in the space between the etheric body and the physical body there exists a sort of web of living thoughts. What exactly is this web of living thoughts? It is what we bring through birth into the earthly world from the soul spiritual world. It is necessary for one to imagine that what we possess within our thinking activity merely in pictures, what therefore only reflects something within our thinking activity, has an independent life of its own. What we feel in having thoughts, however, is not within this, but the web of thought is permeated by objective being, that is to say, it is a working, weaving, active web of thought. Indeed, it works on the human being during his whole life between birth and death, helping to shape him.

I beg you to keep what I just said fully in mind. One cannot say, for instance, that the human being is formed entirely by this web of thought, that man is thus woven entirely out of what one can call world thoughts. That is not the case, at least not regarding this web of thought to be found between the etheric and physical bodies. Man is definitely constituted by something else as well, which approaches him out of the universal cosmos, and what I have described as this web of thought is only weaving with it. We find it, as it were, in the place where our subjective thinking also lies, for we weave the subjective thoughts into this web of thought. The objective thoughts do not appear to the ordinary consciousness at all, but because the subjective thoughts, which are kindled through the outer world, have their life in this web, that which is the content of our thoughts comes to our consciousness.

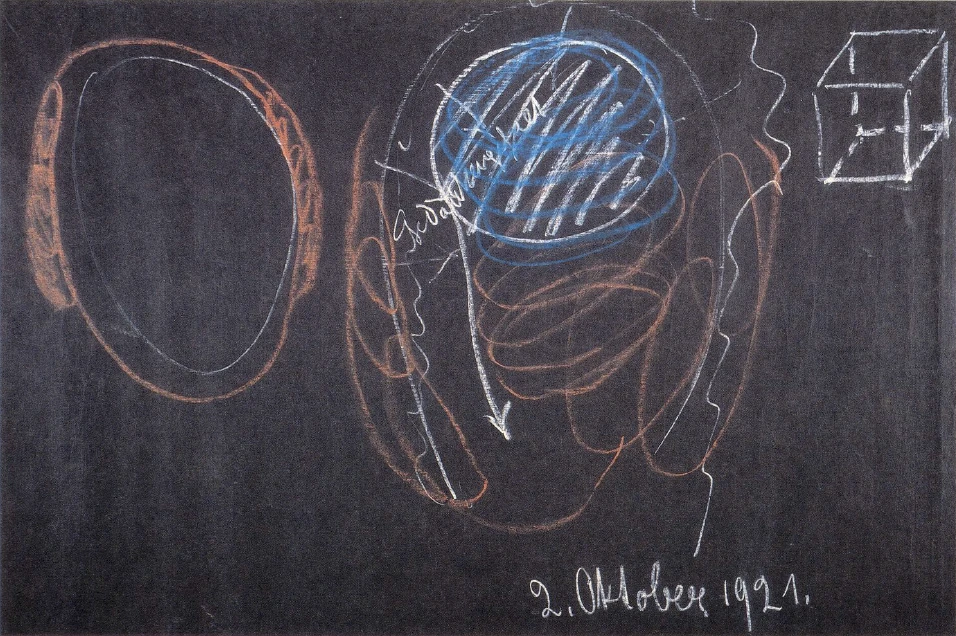

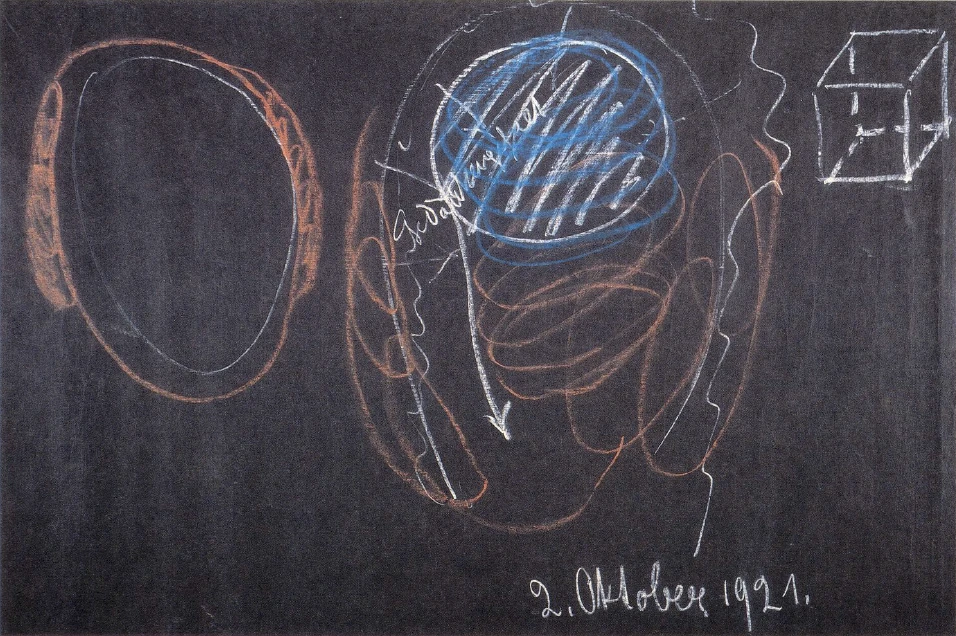

This, then, is the human being from the one side. It is the human being from the side of the skin, insofar as the sum of the senses is basically embodied in the skin. As soon as we approach the sense world itself today, however, the fact is that we do not come right to the senses, in looking upon them as being what was incorporated into man when he entered existence through birth. We would have to draw it like this. If this is the web of thought between the etheric body and the physical body (see drawing, bright), it is surrounded from outside by the sense life incorporated in the skin (red). This sense life is thus formed out of the cosmos, as it were, and incorporated into the human being. It is what man has received as a gift, as it were, from the cosmos when coming in through birth he brings what at first is in his web of thoughts. Actually, when one speaks of the human being as evolving through the Saturn, Sun, Moon, and Earth evolutions, as I have described in my Outline of Occult Science, one at first finds this outer evolution, begun on Saturn, expressed mainly in the configuration of the sense organs. This is continued through processes from within into the glandular system, nervous system, and so on; what the human being receives as his organization out of the cosmos, however, proceeds from the senses.

What I have drawn here as a web of thought is something that belongs fully to the individual human being. It is incorporated from the etheric world when the human being enters existence through birth, yet it definitely belongs to the individual human being, that is, it has to do with the individual earthly evolution of the human being. One can thus say that this objective thought organization works upon us during our embryonic life and during our whole life from birth to death, but it is in no way all that produces the entire being of man.

On the other hand we have found what is of the nature of will, and we could say that this will nature develops between the astral body and the I. The I as possessed by the human being is entirely of a will nature. During the life between birth and death the I develops, as I have indicated, in such a way that the impulses of willing pass over into deeds of the human being, though not completely; certain things remain behind. What remains behind of a will nature passes over into future karma. When we therefore consider the human begin from the point of view of his physical body, we come in the web of thought to his past karma. Looking at man from the viewpoint of the I, we must be fully conscious that it is the I that actually lives fully in his deeds, actually only first awakes in the deeds of man. What the I withholds in itself is then carried through the portal of death and passes over into future karma, the karma that is coming into existence.

Viewed objectively, therefore, we find what is otherwise in us subjectively as soul life. We find it objectified. We find that we are able to consider it objectively. We find, however, when we look toward the relationship with the subjective, that on the one side we have the thought structure and on the other we have the will structure. In the middle, for subjective experience, stands feeling.

One can arrive at the actual essence of feeling only when one is clear that actually every separate feeling that man can shelter is woven into the whole life of feeling of the human being. The feeling life of man can really be studied only when we understand it in such a way that we say: in any moment of life we are permeated by the totality of our life of feeling. We could also say that we are in a certain mood of feeling [Gefahlstimmung]; in every moment of our life we are in a certain mood of feeling. We should try sometime—each one, of course, can only do it individually—to bring this mood to consciousness. Let us try to bring to consciousness how in some moment of his earthly life man is in a certain mood, a certain state of feeling. You know, of course, how mood has infinite variations. It is such that it can degenerate in one case into a sort of excess gaity; one person may be gay to excess, another suffers from depression, and a third is more equable. If we merely wish to examine this mood in some moment of life, there is no need to go into its ultimate cause; we need only look at the particular shading, the particular nuance of this mood, how in one person it can approach the deepest depression, in another it can be equanimity, in a third it can reach extreme gaiety, and how thousands of intermediate stages can lie between. This mood of feeling is actually different in every human being. Now, if one explores this mood in oneself through a kind of self-knowledge, one actually finds in this mood nothing other than subjective experience, shaded in all sorts of ways by outer events, but nevertheless subjective experience.

If one remains in this subjective experience, that is, in the actual inner weaving of soul, and does not advance to beholding these things objectively, one cannot clarify to oneself the nature, let us say, of this emotional mood of soul at some given moment. One can arrive already in ordinary life, however, at what this mood is, this mood living utterly and entirely in feeling. To do so one must have above all the ability to make psychological observations. One must have the possibility of investigating particularly outstanding personalities regarding the content of their feeling. Then one can have the following experience. Outer observation, it is true, will give only an approximation of the actual truth, but even this approximation is extraordinarily valuable.

We can, for instance, set ourselves the task of studying Goethe, whom one can follow very well from his diaries, his letters, and that which has flowed into his most characteristic works. Following his biography sometimes from day to day, sometimes from morning to afternoon, we can see in his case just what were the moods of his soul [Gemütsstimmung]. One can, for example, set oneself the task of studying in delicate psychological ways the mood of soul that Goethe had at some particular time, let us say in 1790. One will first try to describe it as precisely as possible. One can do this, one can describe this mood as precisely as possible, but then one is pointed in two different directions—it is extraordinarily important to bear this in mind—one is pointed in two directions: to Goethe's life before 1790 and to what he lived through after 1790. When from a psychological viewpoint one compares all that impressed Goethe's soul before 1790 with what then worked upon his soul up to his death—that is, when one brings into the present the preceding and the following part of life—then the wonderful fact emerges that every momentary mood in man represents a cooperation between what has gone before, what he knows and already has consciously encountered in life, and what is yet to come and is not yet given to his conscious experience. What is still unknown to him lives already, however, in the general mood of feeling. One thus can arrive biographically, I would like to say, at this secret of the mood of soul at any moment. Here one touches the borders of those realms of human observation that are gladly neglected by people who spend their lives without much thought. What the future brings to the human being, he still does not know—or so he imagines. In his life of feeling, however, he knows it.

One can go further and make more investigations, investigating for instance, the mood of soul of some person whom one has known very well and who died, let us say, a few years after one had grasped this mood of soul. Then one can see clearly how the approaching death and all connected with it had already thrown its light back on the mood of soul. If one goes into these things, therefore, one can really see the person's past from the life between birth and death and his future up to death playing into what lives in his soul by way of feeling. Hence man's life of soul [Gemütsleben] is so inexplicable to himself; it appears as something elemental since as feeling it is already colored by what is still to be experienced.

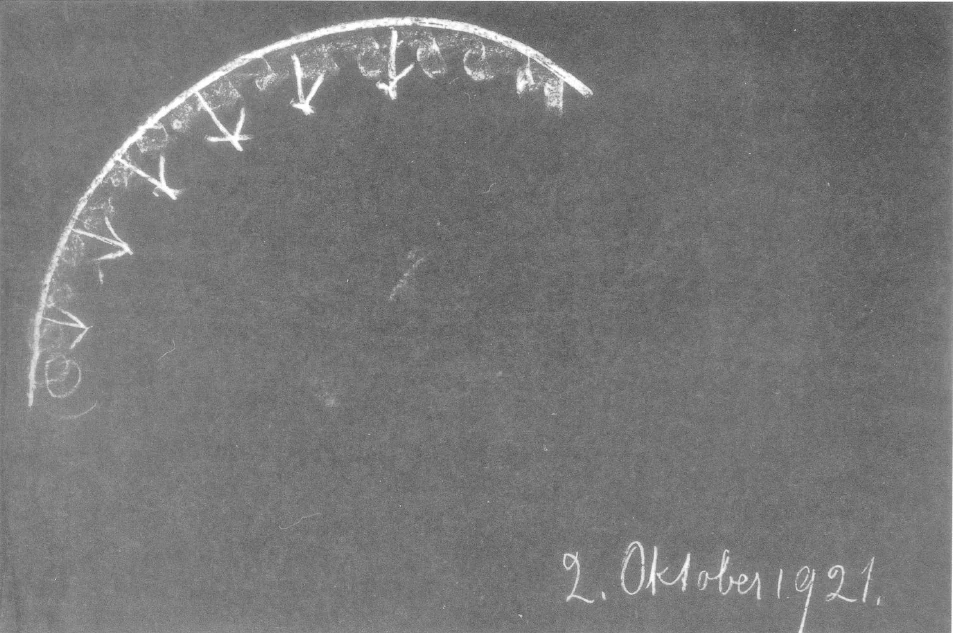

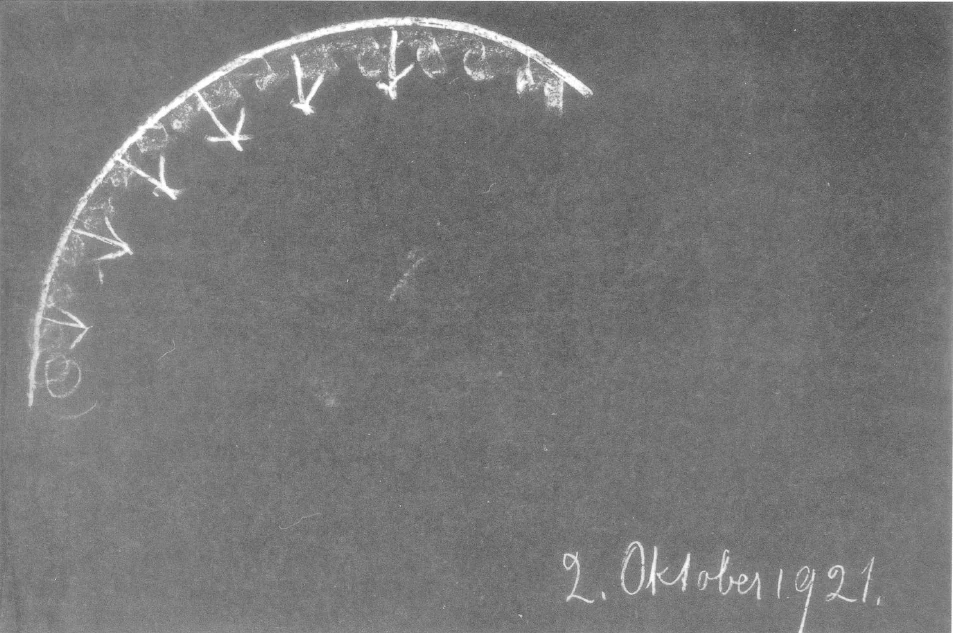

All this had to be taken into consideration at the time when I wrote my Philosophy of Freedom. Why did I have to stress that the free deed can proceed only from pure thought? Simply because if the deed is based on the feeling, the future is already playing into it, and therefore a really free deed could never arise out of feeling. It can arise only from an impulse truly based on pure thought. If you remember what I have presented in the last two days, you will be able to see the matter still more clearly. I have said that what actually takes place in us, what goes on in our human nature, is reflected up into our consciousness in feeling. If I make a sketch, I can say that in feeling there streams upward into our consciousness just what the experience of the feeling is, but downward there streams what can be experienced by Imaginative consciousness as dream pictures (see drawing), that is, what comes into play entirely in Imaginations. For the entire human being, therefore, the life of feeling runs its course in such a way that what we are conscious of as feeling streams upward (blue), and downward there streams into the organization what is actually picture, what is really seen when it is seen through Imaginative consciousness as picture (red, inside). For the ordinary consciousness this streams down into the whole human being as something quite unknown. Not indeed in the individual events, for they must first come about—I beg you to realize this—but in the general mood of life there lives in man as a sort of basic tone the outcome of his future experiences. It is not as if the pictures of what takes place lived there; the impressions of it live in the pictures.

You must not imagine these pictures that stream downward to be like a movie reeling off the future; you must rather picture them as the result of the impressions. Only in the case of certain people who have an atavistic clairvoyance can pictures arise that may be interpreted as pictures of definite facts, and then there can be a certain vision into the immediate future. Today, however, we shall mainly interest ourselves in the fact that what constitutes man's world of feeling descends into him in a pictorial way.

Now, as we pass over from feeling to willing, what enters man here, as I presented to you, presses outward and becomes his karma that is becoming, his future karma (red, outside). What arises in man through his feelings, therefore, has to do with his karma up to his death, while what arises out of the willing is concerned with his karma beyond death.

It is therefore fully possible to follow these things and study them in detail. As the development of anthroposophical spiritual science progresses, one never talks in an abstract way of mere concepts; one speaks rather of the concrete reality that lives in man, which, when he brings it to consciousness, can give him an explanation for the first time of what he actually is. You must receive a strong feeling, however, of how the will, depending as it does on the life of feeling, actually works into the future beyond death, how the will is the creator of future karma.

If we turn once more to the other side, to the web of thought that we found and that lives in man really between the etheric body and the physical body, we must be clear about the following. In experiencing something of the world through sense impressions and thus forming a sensory world conception, in working over these sense impressions thoughtfully, we actually weave with our subjectivity within this web of thought. What we experience in our soul as a result of the sense impressions we unite on the one hand with what is incorporated into us through birth as a web of thought. The objective web of thought, however, remains unconscious, and only that which we interweave, which we press in, as it were, out of our own inner activity of thought, enters our consciousness. It is actually as if the web of thought were there; the subjective thoughts strike against it, beat their way into this web of thought, and this web of thought then reflects our subjective thoughts in a helter-skelter way so that our subjective thoughts come into consciousness (drawing). Note that I say, in a helter-skelter way.

Let us say that you perceive some outer object, a cube, for example, a crystal cube: I will describe the exact process. First of all we see it. We do not stop short at seeing. We think about it, but the thought continues up to the web of thought, and the web of thought, which is incorporated into us through birth and which we have attached to ourselves when we were in the cosmos, which in fact we received through the cosmos—this web of thought is constituted in such a way that we now begin from certain hypotheses to form crystalline ideas that we build up out of our inner being. In forming thoughts, for example, of the isometric system, the tetragonal, the rhombic, the monoclinic, the triclinic, the hexagonal systems, that is to say, in thinking out crystal systems in a mathematical, geometrical way, we find that we can think out the crystal systems. This cube fits into the isometric system that we have cultivated in our inner being. In incorporating something such as, for example, the thought of the cube, into what are, as it were, a priori thoughts that we draw out of our inner being, we are, in this moment when subjective thoughts arise in us, led to the region of objective thoughts. What we cultivate as the geometric element, as purely geometrical-mechanical physics and so on, we draw out of this web of thoughts that is incorporated into us with our birth; the separate, individual elements that we incorporate into these thoughts that we develop about outer sense perceptions and impressions are those that become clear to us in letting them be reflected back to us. They must be permeated, however, by the web of thought living and forming in us eternally—the process at all events is eternal, if not in its individual forms, for these alter from incarnation to incarnation.

We live, therefore, in that we think and incorporate the thought element into our inner life of thought in such a way that we understand it; we live in such a way that we draw forth what is within this web of thought also for our subjective thinking.

Now, what I have just said is something that takes place in the human being continuously, that plays into man's life continuously. At the same time, however, you will see that if on the one hand we begin with feeling we observe what enters from feeling into the organism, what passes over into the will. What stops short in the will, as it were, remaining in the I, becomes future karma. All this brings us in the direction of man's future. If we look to the opposite side, to the web of thought toward which our subjective thoughts also flow, this brings us completely into the stream of the human past. Hence our past on this path, our completed karma, is also to be sought. In feeling, in the most essential sense, past and future meet each other in the human being. The human being is thus born, as it were, out of thoughts. He lives through feeling and weaves in his will what goes with him through the portal of death.

With these words we point to what we actually have subjectively in our life of soul between birth and death. We can go still further, however; we can turn our attention to the following. We can ask ourselves: what actually happens when the subjective thoughts, which we tie to the outer impressions, unite with what is certainly only the past, as I have just described? You see, the subjective thought becomes conscious to us first as thought. As thought it has a certain conceptual content [Vorstellungsinhalt]. We think a content when we think about the cube. You must be quite clear, however, about what I suggested two days ago, that in the life of soul we cannot simply separate thinking, feeling, and willing.

In willing all the motives of our moral thoughts are living. Also in thinking, however, in subjective thinking, we are conscious that not only do we have a thought content, but we link one thought to another, and we are conscious of the activity that links one thought to another. What, then, is at work in thinking? In a delicate way, the will lives in thinking, particularly in subjective thinking. We must be clear, therefore, that in thinking there lives on the one hand the content of thought and on the other hand the will's activity in thinking. Now, if the thoughts strike against us here (see drawing, page 82), they are reflected back to us, of course, as thoughts, but in the thoughts, in these subjective thoughts that we project inward, thrust inward toward the web of thought, the will in fact is also living. We cannot actually use this will in our ordinary consciousness; just think how it would be if this activity that I have pointed out to you here came quite clearly to expression in memory—in memory, the will must already have disappeared! It must still be active, but when the memory is complete, when the remembered thought is there, the memory certainly would not be pure, it would not clearly reflect what it should reflect as a past experience, if it were permeated by will! When you remember what you ate yesterday, you naturally can no longer alter the soup, for the will is already outside, is it not? The pure content of thought must arise. In reflecting, therefore, the will must be laid aside. Where does it go then?

Now, if I make the same drawing and have the web of thought here, and there the reflecting, then the content of thought simply enters the consciousness. The will content of the thought goes below and unites itself with the other content of will and feeling and passes into future karma, becoming thus a constituent of future karma (light shading; dark shaded arrows from above).

On the other hand, our will impulses are like a sleeping portion even during our waking life. We do not see down below into the regions where the will actually lives. We first have the thought of the will impulse. This then passes in an unconscious way, as it were, into willing, and only when willing is manifested outwardly do we observe again what happens through us, what we experience in ordinary consciousness through willing. With deeds we actually experience everything in the conceptual life; we dream of it in the life of feeling, but we sleep over it in the actual life of will.

It is thoughts, however, that we direct into this life of will. Yes, but when? Only when we do not surrender ourselves to our instincts, our desires, to the so-called lower human nature—for this is indeed down below—which urges us then to willing and to deeds. We receive our will, however, into that which constitutes our subjective experience when we control it with our pure thoughts, which are directed toward willing, that is to say, when we control it with our intuitively grasped moral ideals. We can give these intuitively grasped moral ideas to the thought-will on the path down below toward the region of the will. In this way our will becomes permeated by our morality, and hence in the inner being of man the struggle takes place continuously between what man sends down into the will region out of his moral intuitions and what rages and boils down below in his instinctive, dreamlike life. This is all going on in the human being, but what goes on in the human being down below is at the same time that in which his human future beyond death is being prepared. This future thrusts up into the region of feeling. This future actually lives in willing. It thrusts upward into the region of feeling, and more is woven into feeling than what I have already described as the mood of feeling that has a significance for the life between birth and death. In the general state of feeling that I have described as ranging from an extreme depression to complete wildness and excess of gaiety, there can take place everything in which the human past and the human future play into one another in the life between birth and death. Also what goes beyond death, however, penetrates into what comes up from below. And what is living there? Something lives there that we sense as something objective, because it emerges out of the regions where consciousness no longer participates. It is also something objective, because it has to do with the laws by which we bear ourselves as moral beings through death. What is reflected there is the conscience. Grasped psychologically, this is the actual source of conscience. If psychology really wished to approach these things, it would have to investigate the details of the soul life along these lines, and everywhere it would find confirmation of the guiding principles given by anthroposophical spiritual science, right into the most minute details of the life of soul.

We see, therefore, that our feelings stream toward our thoughts. They stream first toward our subjective thoughts and give them life, but they also strike against the objective web of thoughts, and in this we experience ourselves as given, as beings who have come into earthly existence through birth. On the other hand, we can experience ourselves as beings who go through death. One need only study the inner being of man and one finds proclaimed in that inner being something that points beyond man, that is, beyond birth and death; it points therefore into that world which is not encompassed within the sensory, for this world that is not encompassed within the sensory indeed gives us what actually exists in our inner being. It would be of especially great importance if there were research in a real psychology (what is considered psychology today is nothing but a sum of formalisms) into the mood of soul of the human being in a moment where past and future flow into one another. Much that is enigmatic in human life would be discovered in this way, and people would be convinced that a protest very easily made has, in fact, no basis. The protest that is often made is this: well, what would a man become if he were continually examining himself and gazing into his inner being in order to see from his subjective mood of soul what perhaps lay in his future? This protest is easily made, but it is only fanciful. It is imagined that the way in which the future appears is just the same as it is when actually beheld and experienced. The future is not reflected, however, as it is later experienced! It is experienced in intercourse with the outer world, in encounter with things in the outer world. What goes on inwardly in man manifests itself as a raying out and is something that can never mislead him on his life's path, however precisely he knows the human being. Generally, the protests against a knowledge of the human being arise out of fear based utterly on illusions, which one creates because one judges simply by the life of ordinary consciousness, because people will not rise to the view that as soon as consciousness ascends into higher regions it experiences something entirely new.

Yesterday I showed you how, when man comes through the portal of death, he develops himself with two longings that proceed on the one hand from the life of thought and on the other from the life of will. We saw how the thought life longs for cosmic existence and how the will life after death longs for human existence. This lasts until what I called the Midnight Hour of Existence, when a rhythmic reversal then takes place. The thought element then begins to long for the human state, and the will element begins to long to pour itself out into the cosmos. The will element thus lives in the inherited characteristics, while the element of thought lives in the individual, in what is incorporated into the new earthly life.

The will element surrounds us, as it were, in what we receive from our ancestors, seen outwardly in the inherited characteristics and inherited substances. The thought element is that which is incorporated into us, and during life we again unite this thought life with all that we draw up from the depths of the life of feeling and will. This thought life at first is incorporated into us not as something warm and living like our inner life generally. Were we to remain with the thought life as it was when we were born, we would become thought automatons, as it were, full of inner coldness. At the moment of birth, however, the individual inner being begins to stir out of the will and out of the feeling and to permeate with warmth and life that which had first become cold on the way from death to birth. Hence as human beings we have the possibility of permeating with individual warmth that which must constitute cold in us out of the wide universe.

Man thus incorporates himself into the spatial and into the course of world becoming. He thus stands within it. These things are completely hidden from present-day natural scientific thinking. Present-day natural scientific thinking does not wish to approach a true knowledge of the human being. Man thus experiences himself today—and will do so always more and more—in such a way that he cannot recognize in himself his actual being, though he may recognize much about the surrounding world. By reason of the present scientific education and education in general, man lives in such a way today that fundamentally he grasps nothing of his own being. This state will increase more and more. If it could be fully realized what comes to the human being directly through one-sided natural scientific knowledge, he would be entirely estranged from himself. His inner individual element would want to live upward and to melt, through its warmth, the ice masses that we have carried into earthly existence through birth. The human being would go to pieces in his soul in this process that inwardly overpowers him; it indeed goes on without his knowledge, but he can endure it for a long period only if he recognizes it. All the signs of the times point to the fact that the human being must really come to the self-knowledge characterized. It is simply the task of the present life of spirit in its progress toward the immediate future truly to embody these things in cultural evolution.

Education, however, has employed up to now great quantities of fear, great quantities of antipathy, to prevent the vindication of what is so necessary to humanity if it does not wish to sink into decline but to come to a new ascent.

Fünfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich möchte noch einmal, damit der Zusammenhang gewahrt wird, kurz rekapitulieren, was in den letzten Tagen vor unsere Seele getreten ist in bezug auf die Erkenntnis des seelischen und geistigen Lebens des Menschen. Insbesondere demjenigen, was für einen gewissen vorläufigen Abschluß dieser Betrachtungen noch nachzutragen sein wird, möchte ich das Nötige vom Vorangegangenen vorausschicken. Ich will heute mehr von den Resultaten sprechen; den Gang der Beobachtung habe ich ja in den letzten Tagen auseinandergesetzt.

[ 2 ] Wir haben gesehen, daß vorhanden ist gewissermaßen in dem Zwischenraum zwischen dem ätherischen Leib und dem physischen Leib, sagen wir, ein Gewebe von lebendigen Gedanken. Dieses Gewebe von lebendigen Gedanken, was ist es denn eigentlich? Es ist dasjenige, was wir durch die Geburt aus der geistig-seelischen Welt hereintragen in die irdische Welt. Es ist notwendig, daß man sich vorstelle, daß das, was wir innerhalb unserer Denktätigkeit nur im Bilde haben, was also innerhalb unserer Denktätigkeit nur etwas abbildet, daß das ein selbständiges Leben für sich habe, aber dann eben nicht darinnen ist, was wir erfühlen, indem wir Gedanken haben, sondern daß das Gedankengewebe durchzogen ist von objektiver Wesenheit, also ein wirkendes, webendes, tätiges Gedankengewebe ist. Das ist beim Menschen ja so, daß es mitwirkt bei seiner Gestaltung, daß es mitwirkt durch das ganze Leben zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode.

[ 3 ] Was ich da zuletzt sagte, bitte ich voll ins Auge zu fassen. Man kann nicht etwa sagen, daß beim Menschen dieses Gedankengewebe ihn ganz bilde, daß also der Mensch ganz herausgewoben wäre aus demjenigen, was man nennen kann Weltgedanken. Das ist nicht der Fall, wenigstens nicht in bezug auf dieses zwischen dem ätherischen und dem physischen Leibe befindliche Gedankengewebe. Der Mensch wird durchaus auch aus anderem konstituiert, das aus dem allgemeinen Kosmos heraus an ihn herankommt, und nur mitwebend ist dasjenige, was ich da als Gedankengewebe beschrieben habe. Aber wir finden es gewissermaßen an derjenigen Stelle, wo unser subjektives Denken auch liegt, denn die subjektiven Gedanken weben wir in dieses Gedankengewebe hinein. Die objektiven erscheinen ja dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein gar nicht, aber indem sich die subjektiven, an der Außenwelt entzündeten Gedanken in dieses Gewebe hineinleben, kommt das, was unser Gedankeninhalt ist, für unser Bewußtsein zustande.

[ 4 ] Das ist also gewissermaßen der Mensch nach der einen Seite hin. Es ist der Mensch nach der Seite seiner Haut hin, insofern in die Haut ja im Grunde genommen die Summe der Sinne eingestaltet ist. Sobald wir aber heute an die Sinneswelt selber herangehen, so ist die Sache so, daß wir gewissermaßen nicht bis zu den Sinnen kommen, indem wir so dasjenige betrachten, was der Mensch eingegliedert bekommen hat, indem er durch die Geburt ins Dasein getreten ist. Wir müssen die Sache schematisch so zeichnen, daß wir sagen: Wenn dieses das Gedankengewebe zwischen dem Ätherleib und dem physischen Leibe ist (siehe Zeichnung, hell), so schlingt sich um dieses Gedankengewebe nach außen alles das, was (rot) in die Haut eingegliedertes Sinnesleben ist. Das ist also gewissermaßen aus dem Kosmos herausgebildet und ist dem Menschen angegliedert. Das ist es also, was der Mensch vom Kosmos gewissermaßen geschenkt erhält, wenn er, durch die Geburt ankommend, das hereinträgt, was zunächst in seinem Gedankengewebe ist. Und eigentlich, wenn man von dem Menschen spricht als sich hindurchentwickelnd durch Saturnentwickelung, Sonnenentwickelung, Mondenentwickelung, Erdenentwickelung, wie ich es beschrieben habe in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß», so finden wir zunächst hauptsächlich diese äußere Entwickelung, vom Saturn angefangen, gerade in der Konfiguration der Sinnesorgane ausgedrückt. Das setzt sich dann allerdings durch Prozesse nach innen ins Drüsensystem, Nervensystem und so weiter fort, aber von den Sinnen geht dasjenige aus, was der Mensch als seine Organisation aus dem Kosmos hereinbekommt. Das aber, was ich hier gezeichnet habe als Gedankengewebe, ist eben durchaus etwas, was dem individuellen Menschen angehört, was allerdings herausgegliedert wird aus der Ätherwelt, indem der Mensch durch die Geburt ins Dasein tritt, was aber durchaus doch dem individuellen Menschen angehört, das heißt, mit der individuell irdischen Entwickelung des Menschen zu tun hat. So daß man sagen kann: Diese objektive Gedankenorganisation, sie arbeitet während unseres Embryonallebens und während unseres ganzen späteren Lebens zwischen Geburt und Tod an uns, aber sie ist nicht etwa alles, was die ganze Wesenheit des Menschen aus sich heraussetzt.

[ 5 ] Auf der anderen Seite haben wir gefunden, was willensartiger Natur ist. Und wir können sagen: Was willensartiger Natur ist, entwickelt sich zwischen dem Astralleib und dem Ich. Das Ich ist eigentlich so wie es der Mensch als Mensch hat, ganz und gar willensartiger Natur. Es entwickelt sich aber so, daß, wie ich angedeutet habe, zunächst während des Lebens zwischen Geburt und Tod die Impulse des Wollens in die Handlungen des Menschen übergehen, aber nicht vollständig; es bleiben Dinge zurück. Und was da zurückbleibt von Willensartigem, das geht in das werdende Karma über. So daß wir also, wenn wir den Menschen nach seinem physischen Leibe hin betrachten, in dem Gedankengewebe nach dem vergangenen Karma kommen, und indem wir den Menschen betrachten nach seinem Ich - das Ich ist es ja, das eigentlich in seinen Handlungen lebt; dessen muß man sich nur vollständig bewußt sein, daß das Ich eigentlich völlig erst in den Handlungen lebt, eigentlich erst erwacht an dem Handeln des Menschen -, wird das, was das Ich gewissermaßen da zurückbehält in sich, dann durch die Pforte des Todes getragen und geht in das Zukunftskarma, in das werdende Karma über.

[ 6 ] Da finden wir also, gewissermaßen objektiv betrachtend, was sonst subjektiv als Seelenleben in uns ist. Wir finden es objektiviert. Wir finden es so, daß wir es objektiv betrachten können. Aber wir finden, wenn wir nach der Verwandtschaft hinschauen mit dem Subjektiven, daß wir nach der einen Seite Gedankengebilde haben, nach der anderen Seite ein Willensgebilde haben. In der Mitte drinnen steht für das subjektive Erleben das Fühlen.

[ 7 ] Dieses Fühlen, man kommt auf seine eigentliche Wesenheit nur, wenn man sich klar darüber ist, daß eigentlich jedes Gefühl, das der Mensch als einzelnes hegen kann, verwoben ist in das ganze Gefühlsleben des Menschen. Und das Gefühlsleben des Menschen läßt sich eigentlich wiederum nur betrachten, wenn wir es so auffassen, daß wir sagen: In einem Lebensaugenblicke sind wir durchströmt, durchsetzt von der Gesamtheit unseres Gefühlslebens. Wir könnten auch sagen: Wir sind in einer gewissen Gefühlsstimmung; in jedem Augenblicke unseres Lebens sind wir in einer gewissen Gefühlsstimmung. Diese Gefühlsstimmung, versuchen wir es einmal - jeder kann es ja eigentlich zunächst nur individuell tun —, diese Gefühlsstimmung uns zum Bewußtsein zu bringen. Versuchen wir uns zum Bewußtsein zu bringen, wieder Mensch in irgendeinem Augenblickeseines Erdenlebens in einer gewissen Gefühlsstimmung ist. Sie wissen ja: diese Gefühlsstimmung ist eine unendlich mannigfaltige. Sie ist so, daß sie bei dem einen ausarten kann in eine, ich möchte sagen, Überfröhlichkeit, daß also der eine im Übermaße fröhlich gestimmt ist, der andere unter Depressionen leidet, der dritte wieder mehr im Gleichmaße gestimmt ist. Wir brauchen, wenn wir bloß auf diese Gefühlsstimmung in irgendeinem Lebensaugenblicke unseren Blick hinrichten wollen, dabei gar nicht auf die Ursachen dieser Gefühlsstimmungen einzugehen, sondern brauchen nur die besondere Schattierung, die besondere Nuance dieser Gefühlsstimmung ins Auge zu fassen: wie sie bei dem einen bis zur tiefsten Depression kommen kann, bei dem anderen im Gleichmaß sein kann, bei dem dritten wieder bis zum Frohsinn, bis zur äußersten Fröhlichkeit gehen kann; wie tausenderlei Zwischenstufen vorliegen können. Bei jedem Menschen ist eigentlich diese Gefühlsstimmung eine andere. Und nun, wenn man sich durch eine Art von Selbsterkenntnis nach dieser Gefühlsstimmung erkundigt, so findet man ja eigentlich zunächst nichts anderes als subjektives Erleben in dieser Gefühlsstimmung, subjektives Erleben, das in allerlei Weise nuanciert ist eben durch die äußeren Erfahrungen, durch die äußeren Erlebnisse; aber eben subjektives Erleben findet man.

[ 8 ] Man kann, wenn man in diesem subjektiven Erleben, also im eigentlichen inneren Seelenweben bleibt, ohne auf das Anschauen einzugehen, also darauf einzugehen, daß einem diese Dinge objektiv werden, man kann sich da nicht über das Wesen, sagen wir, dieser gefühlsmäßigen Seelenstimmung in irgendeinem Augenblicke aufklären. Aber man kann doch schon im gewöhnlichen Leben darauf kommen, was diese Stimmung, diese ganz und gar in Gefühlen lebende Stimmung eigentlich ist. Dazu muß man allerdings die Fähigkeit des psychologischen Betrachtens haben. Man muß die Möglichkeit haben, besonders prägnante Persönlichkeiten vielleicht einmal auf ihren Gefühlsgehalt zu prüfen. Und da können Sie die folgende Erfahrung machen. Allerdings, es wird die äußere Beobachtung nur ein Annäherndes an die eigentliche Wahrheit geben können, aber eben dieses Annähernde ist schon außerordentlich viel wert.

[ 9 ] Wir können uns zum Beispiel die Aufgabe Stellen, Goethe zu studieren, den man ja gut verfolgen kann nach seinen Tagebüchern, Briefen, nach demjenigen, was gerade in seine bezeichnendsten Werke geflossen ist, wo wir immer, da wir ihn biographisch manchmal von Tag zu Tag, manchmal vom Vormittag zum Nachmittag verfolgen können, gerade bei ihm gut sehen können, wie die Gemütsstimmungen sind. Man kann sich zum Beispiel die Aufgabe vorsetzen, in feiner psychologischer Weise die Gemütsstimmung, die Goethe zu irgendeiner Zeit, sagen wir, 1790 hatte, zu studieren. Man wird zunächst versuchen, sie möglichst genau zu beschreiben. Man kann das, man kann diese Gemütsstimmung möglichst genau beschreiben. Und indem man das tut, wird man aber allerdings nach zwei Richtungen hingewiesen - und das ist außerordentlich wichtig, sich einmal vor die Seele zu stellen -, man wird nach zwei Richtungen hingewiesen: man wird auf Goethes Leben vor 1790 gewiesen und auf das, was nach 1790 von Goethe durchlebt worden ist. Und wenn man dann mit einem psychologischen Blicke gleichsam zusammenschaut alles das, was auf Goethes Seele eingedrungen ist vor 1790, mit demjenigen, was dann bis zu seinem Tode auf seine Seele gewirkt hat - wenn man sich also vergegenwärtigt das vorhergehende und nachfolgende Leben -, da stellt sich das Wunderbare heraus, daß jeder Gemütsstimmungsaugenblick im Menschen ein Zusammenwirken darstellt zwischen dem, was vorangegangen ist, das der Mensch kennt, das schon in seinem Leben bewußt vorhanden ist, und dem, was erst kommt, demjenigen also, was noch nicht seiner zunächst bewußten Erfahrung gegeben ist. Das dem eigenen Bewußtsein zunächst noch Unbekannte lebt aber schon in der allgemeinen Gefühlsstimmung. Man kann es schon so biographisch, möchte ich sagen, herausbekommen, dieses Geheimnis der Gemütsstimmung eines Augenblickes. Und man grenzt mit dem schon durchaus an diejenigen Gebiete der menschlichen Betrachtung, die gern von den Menschen, die gedankenlos dahinleben, außer acht gelassen werden. Was geht den Menschen die Zukunft an, er weiß sie ja noch nicht — so meint er. In seinem Gefühlsleben weiß er sie.

[ 10 ] Und wenn man dann weitergeht und weiter prüft, prüft zum Beispiel die Gemütsstimmung irgendeines Menschen, den man genau gekannt hat und von dem man erfahren hat, daß er, sagen wir, ein paar Jahre, nachdem man diese Gemütsstimmung aufgefaßt hat, gestorben ist, so kann man ganz genau sehen, wie der nahende Tod mit alledem, was mit ihm zusammenhängt, durchaus schon sein Licht zurückgeworfen hat auf die Gemütsstimmung. So daß man also wirklich, wenn man auf diese Dinge eingeht, sehen kann zunächst des Menschen Vergangenheit aus dem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, und die Zukunft bis zum Tode hineinspielen in demjenigen, was im Gemüte gefühlsmäßig zusammen lebt. Daher hat das Gemütsleben etwas für den Menschen selbst so Unerklärliches. Daher stellt es sich herein in das Leben wie etwas Elementares, weil es durchaus als Gefühl schon tingiert ist von demjenigen, was wir erst erleben werden.

[ 11 ] Diese Sache mußte ja durchaus schon berücksichtigt werden in der Zeit, in der ich meine «Philosophie der Freiheit» abfaßte. Warum mußte ich denn darauf dringen, daß die freie Handlung nur hervorgehen darf aus dem reinen Denken? Nun, weil, wenn die Handlung auf das Gefühl gebaut ist, ja die Zukunft schon hineinspielt, also aus dem Gefühl heraus niemals eine wirklich freie Handlung kommen könnte! Die kann nur aus dem wirklich im reinen Denken erfaßten Impuls heraus kommen. Und wenn Sie sich erinnern an das, was ich an den zwei verflossenen Tagen dargestellt habe, so werden Sie die Sache noch mehr an Ihre Seele heranbringen können. Ich habe gesagt: So wie uns das Gefühl erscheint, so ist es ja zunächst so, daß das, was in uns eigentlich geschieht, was in unserer Menschenwesenheit vorgeht, im Gefühl zurück-, heraufstrahlt in unser Bewußtsein. Wenn ich schematisch zeichne, so kann ich sagen: Im Gefühl strömt nach oben in das Bewußtsein herein, was eben das Erlebnis des Gefühles ist; nach unten aber strömt, was von dem imaginativen Bewußtsein den Traumbildern gleich erlebt werden kann (siehe Zeichnung Seite 89), was also durchaus in Imaginationen sich abspielt. So daß das Gefühlsleben eigentlich für den Gesamtmenschen so verläuft, daß nach oben strömt, was uns als Gefühl bewußt wird (blau), daß aber in die menschliche Organisation hinunter- und hineinströmt, was eigentlich Bild ist, was wirklich dann, wenn es durch das imaginative Bewußtsein geschaut wird, eben als Bild geschaut wird (rot, innen). Das strömt für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein als ein Unbewußtes hinunter in die ganze menschliche Wesenheit. Zwar nicht in den einzelnen Ereignissen, denn die müssen eigentlich erst herankommen - ich bitte, das wohl aufzufassen -, aber in der Gesamtstimmung des Lebens lebt in dem Menschen durchaus auch wie, ich möchte sagen, in einem Grundton das Ergebnis seiner zukünftigen Erlebnisse. Nicht als ob da die Bilder lebten von dem, was geschieht; aber die Eindrücke davon, die leben in den Bildern.

[ 12 ] Also diese Bilder, die da hinunterströmen, müssen Sie sich nicht vorstellen als so etwas, wie wenn kinematographisch die Zukunft abliefe, sondern Sie müssen sie sich vorstellen als das Ergebnis der Eindrücke. Nur bei gewissen Leuten, die atavistisch hellseherisch sind, bei denen können die Bilder, die sich dann übersetzen in die Bilder von gewissen Tatsachen, zum Vorschein kommen, und dann kann ein gewisses Schauen in die nächste Zukunft ja stattfinden. Uns soll aber heute vorzugsweise das interessieren, daß zunächst in den Menschen hinuntergeschickt wird in bildhafter Weise, was sich als seine Gefühlswelt auslebt.

[ 13 ] Indem wir nun vom Gefühl zum Willen übergehen, dringt das, was so, wie ich es Ihnen dargestellt habe, nun hier in den Menschen hineingeht, nach außen und wird zu seinem werdenden Karma, zu seinem Zukunftskarma (rot, außen). So daß, was im Menschen entsteht durch seine Gefühle, gewissermaßen etwas zu tun hat mit seinem Karma bis zu seinem Tode hin; das aber, was aus dem Willen entsteht, hat zu tun mit seinem Karma über den Tod hinaus.

[ 14 ] Es ist also durchaus möglich, diese Dinge alle in den Einzelheiten zu verfolgen und zu studieren. Man redet, indem man immer weiterrückt in bezug auf die Ausgestaltung anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft, durchaus nicht in schematischer Weise von bloßen Begriffen, sondern man redet von dem Konkreten, das im Menschen lebt und das, indem es der Mensch zu seinem Bewußtsein bringt, ihm erst die Aufklärung gibt über das, was er eigentlich ist. Aber Sie müssen ein starkes Gefühl davon bekommen, wie der Wille, der sich anlehnt an das Gefühlsleben, eigentlich in die Zukunft, über den Tod hinaus wirkt, wie der Wille der Erzeuger des werdenden Karma ist.

[ 15 ] Wenn wir uns noch einmal nach der anderen Seite wenden, nach jenem Gedankengewebe, das wir gefunden haben und das wirklich zwischen dem Ätherleib und dem physischen Leibe im Menschen lebt, dann müssen wir uns ja klar sein, daß, indem wir durch die Sinneseindrücke etwas von der Welt erfahren, uns also eine sinnliche Weltanschauung bilden, wir dann diese Sinneseindrücke gedanklich verarbeiten, und indem wir sie gedanklich verarbeiten, weben wir eigentlich mit unserer Subjektivität in diesem Gedankengewebe darinnen. Wir verbinden, was wir infolge der Sinneseindrücke in unserer Seele erleben, einerseits mit dem, was uns als ein Gedankengewebe durch die Geburt hindurch eingegliedert wird; aber das eine, das objektive Gedankengewebe bleibt unbewußt, und nur das, was wir hineinweben, was wir gewissermaßen hineindrängen aus unserer inneren Gedankentätigkeit heraus, das kommt uns zum Bewußtsein. Es ist tatsächlich so, als ob das Gedankengewebe da wäre, die subjektiven Gedanken anschlagen, da hineinschlagen in dieses Gedankengewebe und dieses Gedankengewebe dann zurückspiegelt unsere subjektiven Gedanken, indem es ihnen allerdings allerlei Richtungen gibt und uns dadurch unsere subjektiven Gedanken zum Bewußtsein kommen (siehe Zeichnung Seite 93). Ich sage, indem es ihnen allerlei Richtungen gibt.

[ 16 ] Sehen Sie, wenn wir, sagen wir, irgendeinen äußeren Gegenstand wahrnehmen - ich will Ihnen den Vorgang ganz genau schildern -, zum Beispiel also einen Würfel, einen Kristallwürfel: wir sehen ihn zunächst. Wir bleiben beim Sehen nicht stehen. Wir denken über ihn. Aber dieser Gedanke leitet sich bis zu dem Gedankengewebe fort, und das Gedankengewebe, das uns eingegliedert ist durch die Geburt, mit dem wir uns also behaftet haben, als wir im Kosmos waren, das wir ja durch den Kosmos auch bekommen haben, dieses Gedankengewebe ist so beschaffen, daß wir nun anfangen, aus gewissen Voraussetzungen heraus uns kristallographische Ideen zu bilden, die wir uns aus dem Inneren heraus bilden. Indem wir uns zum Beispiel bilden die Gedanken des tesseralen Systems, des tetragonalen Systems, des rhombischen Systems, des monoklinen Systems, des triklinen Systems, des hexagonalen Systems, also indem wir ausdenken in einer mathematisch-geometrischen Art Kristallsysteme, dann finden wir, wir können die Kristallsysteme ausdenken. In das tesserale System, das wir da in unserem Inneren ausgebildet haben, da paßt dieser Würfel hinein. Indem wir so etwas wie zum Beispiel den Gedanken des Würfels eingliedern in das, was gewissermaßen Apriori-Gedanken sind, die wir aus unserem Inneren herausnehmen, sind wir in diesem Augenblicke, wo uns subjektive Gedanken aufstoßen, auf das objektive Gedankengebiet hingelenkt. Denn was wir als Geometrisches, als rein geometrischmechanische Physik und so weiter ausbilden, das holen wir aus diesem Gedankengewebe, das uns mit der Geburt eingegliedert ist, heraus, und das einzelne Individuelle, das wir eingliedern diesen Gedanken, die wir über die äußeren sinnlichen Anschauungen und Eindrücke entwickeln, die sind diejenigen, über die wir uns aufklären, indem wir sie uns zurückreflektieren lassen, aber durchsetzen lassen mit dem gewissermaßen ewig in uns lebenden gestaltenden Gedankengewebe, dem Prozesse nach wenigstens ewig, wenn auch nicht in den einzelnen Formen, denn die ändern sich von Inkarnation zu Inkarnation.

[ 17 ] Wir leben also, indem wir denken und indem wir das Gedankliche so eingliedern in unser inneres Gedankenleben, daß wir es verstehen, wir leben so, daß wir auch für unser subjektives Denken heraufholen, was in diesem Gedankengewebe darinnen ist.

[ 18 ] Nun, das, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, das ist ja etwas, was im Menschen fortwährend vorgeht, was sich fortwährend im Menschen abspielt. Aber zu gleicher Zeit werden Sie sehen: Auf der einen Seite, indem wir beim Gefühl beginnen, fassen wir ins Auge, was vom Gefühl aus in den Organismus hineingeht, zum Willen übergeht. Das, was vom Willen gewissermaßen im Ich still stehen bleibendes, werdendes Karma wird, das alles bringt uns in die Richtung der Menschenzukunft. Wenn wir zur entgegengesetzten Seite, nach dem Gedankengewebe hin sehen, nach welcher auch unsere subjektiven Gedanken laufen, das bringt uns durchaus in die Strömung nach der menschlichen Vergangenheit hin. Daher ist auf diesem Wege auch unser vergangenes, unser vollendetes Karma zu suchen. Im Gefühle begegnen sich wirklich im eminentesten Sinne Vergangenheit und Zukunft im Menschen. Der Mensch wird also gewissermaßen aus den Gedanken heraus geboren. Er lebt sich durchs Gefühl hindurch und webt in seinen Willen, was mit ihm durch die Pforte des Todes geht.

[ 19 ] Indem wir diese Worte aussprechen, deuten wir eigentlich hin auf das, was wir subjektiv im Seelenleben haben in der Zeit zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Aber wir können noch weitergehen. Wir können das Folgende ins Auge fassen. Wir können uns fragen: Wie ist es denn nun eigentlich, wenn sich diese subjektiven Gedanken, die wir an die äußeren Eindrücke anknüpfen, mit demjenigen, was ganz gewiß nur Vergangenes ist, zusammenfügen, so wie ich das eben beschrieben habe? Sehen Sie, der subjektive Gedanke, er wird uns zunächst bewußt als Gedanke. Als Gedanke hat er einen gewissen Vorstellungsinhalt. Wir denken einen Inhalt, wenn wir über den Würfel denken. Aber Sie werden sich durchaus über das klar werden, was ich schon vorgestern angedeutet habe: Wir können im Seelenleben nicht ohne weiteres Denken, Fühlen und Wollen trennen.

[ 20 ] Im Wollen leben alle Motive unserer moralischen Gedanken. Aber auch im Denken, im subjektiven Denken sind wir uns bewußt, daß wir nicht nur einen Gedankeninhalt haben. Wir reihen einen Gedanken an den anderen an, und wir sind uns der Tätigkeit bewußt, die einen Gedanken an den anderen anreiht. Was lebt denn da im Denken? Nun, es lebt auf eine feine Weise im Denken, namentlich im subjektiven Denken, schon der Wille. Wir müssen uns also klar sein: Indem wir denken, lebt auf der einen Seite der Gedankeninhalt, auf der anderen Seite die Willenstätigkeit im Denken. Wenn nun die Gedanken hier anstoßen (siehe Zeichnung) — sie werden uns allerdings als Gedanken zurückreflektiert, aber in den Gedanken, in diesen subjektiven Gedanken, die wir gewissermaßen hineinprojizieren, hineinstoßen nach dem Gedankengewebe, lebt ja auch Wille. Diesen Willen können wir eigentlich im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht brauchen. Fühlen Sie nur, wenn diese Tätigkeit, die ich Ihnen hier angedeutet habe, ganz klar zum Ausdruck käme in der Erinnerung: in der Erinnerung muß der Wille schon geschwunden sein! Er muß noch tätig sein; aber wenn die Erinnerung fertig ist, wenn der erinnerte Gedanke da ist — die Erinnerung würde ja nicht rein sein, sie würde nicht klar abbilden, was sie abbilden soll als ein vergangenes Erlebnis, wenn sie vom Willen durchwert

[ 21 ] strömt wäre! Man kann ja natürlich, wenn Sie sich an das erinnern, was Sie gestern gegessen haben, nicht mehr die Suppe ändern; da ist der Wille schon heraußen, nicht wahr. Es soll der reine Gedankeninhalt zutage treten. Der Wille muß also im Reflektieren abgestreift werden. Wo kommt er denn hin?

[ 22 ] Nun, wenn ich dieselbe Zeichnung (S. 89) mache, wenn ich hier das Gedankengewebe habe und da reflektiert wird, so geht einfach der Gedankengehalt ins Bewußtsein. Der Willensgehalt der Gedanken, er geht hinunter und vereinigt sich mit dem anderen Willens- und Gemütsgehalt und geht ein in das werdende Karma, wird also ein Bestandteil des werdenden Karma (siehe Zeichnung Seite 94, hellschraffiert; dunkelschraffierter Pfeil nach unten).

[ 23 ] Auf der anderen Seite: Unsere Willensimpulse, sie sind ja wie der schlafende Teil auch während unseres Wachlebens. Wir sehen nicht hinunter bis in diejenigen Regionen, wo der Wille eigentlich lebt. Wir haben zuerst den Gedanken des Willensimpulses. Der geht dann gewissermaßen in unbewußter Weise über in das Wollen, und erst, wenn das Wollen sich nach außen äußert, so betrachten wir wiederum das, was durch uns geschieht, das, was wir im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein erleben beim Wollen. Beim Handeln erleben wir eigentlich alles im Vorstellungsleben, träumen davon im Gefühlsleben, schlafen aber darüber in bezug auf das eigentliche Willensleben.

[ 24 ] Aber es sind eben Gedanken, die wir hineinleiten in dieses Willensleben. Wann aber nur? Nur dann, wenn wir uns nicht unseren Instinkten, unseren Trieben, wenn wir uns also nicht bloß der sogenannten niederen Menschennatur hingeben, denn die ist schon da unten, die treibt uns dann zum Wollen und zum Handeln. Dann aber bekommen wir unseren Willen herein in dasjenige, was unser subjektives Erleben ausmacht, wenn wir ihn beherrschen mit unseren reinen Gedanken, die nach dem Wollen sich hinrichten, das heißt, wenn wir ihn beherrschen mit unseren intuitiv erfaßten moralischen Idealen. Diese intuitiv erfaßten moralischen Ideale können wir dem Gedankenwillen mit auf den Weg geben hinunter nach der Willensregion. Dadurch wird unser Wille durchsetzt von unserer Moralität, und im Inneren des Menschen findet daher fortwährend dieser Kampf statt zwischen demjenigen, was der Mensch hinunterschickt aus seinen moralischen Intuitionen in die Willensregion, und demjenigen, was da unten wühlt und brodelt in seinem instinktiv-traumhaften Leben. Das ist alles das, was im Menschen vorgeht. Aber das, was da unten im Menschen vorgeht, ist zu gleicher Zeit dasjenige, in dem sich vorbereitet seine Menschenzukunft über den Tod hinaus. Es schlägt herauf in die Gefühlsregion. Es lebt eigentlich im Willen diese Zukunft. Sie schlägt herauf in die Gefühlsregion, und mehr webt sich noch in das Fühlen hinein als nur dasjenige, was ich vorhin als die Gefühlsstimmung, die eine Bedeutung hat für das Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod, geschildert habe. In der gewöhnlichen Gefühlsverfassung, die ich geschildert habe als sich ausdehnend von der äußersten Depression zu der völligen Ausgelassenheit, zu der Überfröhlichkeit, da kann sich abspielen all das, worinnen zusammenspielt Menschenzukunft und Menschenvergangenheit in dem Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod. Aber auch das, was über den Tod hinausgeht, dringt ein in dasjenige, was da von unten heraufkommt. Und was lebt da? Da lebt nun etwas — weil es aus den Regionen heraufkommt, wo das Bewußtsein nicht mehr mitmacht, empfinden wir es als etwas Objektives. Es ist auch etwas Objektives, denn es hat mit den Gesetzmäßigkeiten zu tun, durch die wir uns als moralische Menschenwesen durch den Tod tragen. Was da zurückstrahlt, das ist dann das Gewissen. Und psychologisch erfaßt, ist dies der eigentliche Ursprung des Gewissens. Wollte sich die psychologische Wissenschaft wirklich an diese Dinge heranmachen, dann müßte sie nun die Einzelheiten des Seelenlebens nach diesen Richtlinien hin prüfen, und sie würde bis in die minuziösesten Einzelheiten des Seelenlebens überall die Bestätigung dessen finden, was von anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft als solche Richtlinien gegeben wird.

[ 25 ] Wir sehen also: Unsere Gefühle strömen unseren Gedanken entgegen. Sie strömen zunächst entgegen und beleben unsere subjektiven Gedanken; aber sie schlagen gewissermaßen auch nach dem objektiven Gedankennetz hin, und in diesem erleben wir uns selbst als gegeben, als ein Wesen, welches sich durch die Geburt ins irdische Dasein hereingelebt hat. Nach der anderen Seite können wir uns erleben als das Wesen, das durch den Tod geht. Man braucht nur das menschliche Innere wirklich zu studieren, und man kommt durchaus auf das, was im menschlichen Inneren sich schon als solches ankündigt, daß es über den Menschen, das heißt über Geburt und Tod hinausweist, daß es also hinausweist in diejenige Welt, die nicht innerhalb des Sinnlichen beschlossen ist. Denn diese Welt, die nicht innerhalb des Sinnlichen beschlossen ist, gibt uns ja zunächst das, was in unserem Inneren eigentlich vorhanden ist. Insbesondere das wäre von einer großen Wichtigkeit, daß man wirklich in einer realen Psychologie - denn das, was heute als Psychologie gilt, ist ja nur eine Summe von Formalismen eben untersuchte die Gemütsstimmung des Menschen in einem Augenblick, wo Vergangenheit und Zukunft ineinanderfließen. Man würde dadurch vieles Rätselhafte im Menschenleben finden, und man würde sich überzeugen, daß ein Einwand, der außerordentlich naheliegt, eben nicht gilt. Der Einwand, der außerordentlich naheliegt, ist der: Ja, was würde denn eigentlich aus dem Menschen, wenn er sich so durchschauen würde, wenn er also gewissermaßen fortwährend in sein Inneres hineinblicken würde, um seine subjektive Gemütsstimmung auf das hin zu prüfen, was gewissermaßen in seiner Zukunft liegt? - Dieser Einwand liegt nahe, aber es ist nur der Einwand, den die Einbildung macht. Man stellt sich vor, daß eben die Art, wie die Zukunft erscheint, so ist, wie sie dann in der Anschauung, in der Erfahrung erlebt wird. So wird ja nicht die Zukunft abgebildet, wie sie dann erlebt wird! Erlebt wird sie im Verkehre mit der Außenwelt, im Zusammenstoßen mit der Außenwelt. Was da innerlich vor sich geht, das ist dasjenige, was im Menscheninneren sich als das Ausstrahlende kundgibt, und das ist etwas, was, wenn es der Mensch noch so genau kennt, ihn durchaus nicht in seinem Lebenswege beirren kann. Wie überhaupt die Einwände gegen Menschenkenntnis aus der Furcht entstehen, die ganz und gar wurzelt in Illusionen, die man sich macht, weil man eben bloß nach dem Leben des gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins urteilt, weil man sich nicht aufschwingen will zu der Anschauung, daß, sobald das Bewußtsein hinaufsteigt in höhere Regionen, es eben völlig Neues erlebt. Nun aber habe ich Ihnen ja gestern gezeigt, wie, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes kommt, er sich entwickelt mit zwei Sehnsuchten, die auf der einen Seite vom Gedankenleben, auf der anderen Seite vom Willensleben ausgehen: wie das Gedankenleben sich sehnt nach Weltensein, das Willensleben, indem es durch den Tod geht, sich sehnt nach Menschensein; wie das dauert bis zu dem, was ich genannt habe die Mitternachtsstunde des Daseins; wie dann eine rhythmische Umkehr stattfindet: wie das Gedankliche sich anfängt zu sehnen nach dem Menschlichen, und das Willentliche sich anfängt zu sehnen nach dem Ausgießen in den Kosmos, so daß das Willensmäßige dann in den vererbten Eigenschaften lebt. Das Gedankliche aber lebt in dem Individuellen, das sich eingliedert in das neue Erdenleben. Das Willensmäßige umgibt uns gewissermaßen in dem, was wir von den Vorfahren — äußerlich angeschaut: in den vererbten Eigenschaften und vererbten Substanzen — haben. Das Gedankliche ist das, was sich in uns eingliedert, und während des Lebens verbinden wir wieder mit diesem Gedankenleben alles das, was wir aus den Tiefen des Gemüts- und Willenslebens heraufholen. Zunächst wird uns das Gedankenleben eingegliedert als etwas, was zunächst nicht warm und lebendig ist wie unser Innenleben überhaupt. Würden wir so bleiben mit dem Gedankenleben, wie wir geboren werden, wir würden gewissermaßen Gedankenautomaten werden voller innerer Kälte. Aber im Momente der Geburt beginnt das individuelle Innere aus dem Willen und aus dem Gemüte heraus sich zu regen, mit Wärme und Leben zu durchsetzen das, was zunächst kalt geworden ist auf dem Wege von dem Tode bis zur Geburt; und dadurch haben wir eben als Mensch die Möglichkeit, mit dem individuell Warmen zu durchsetzen, was uns aus dem weiten Weltenall in Kälte konstituieren muß.

[ 26 ] So gliedert sich der Mensch ein in das Räumliche und in den Werdegang der Welt. So steht er darinnen. Diese Dinge werden von dem heutigen naturwissenschaftlichen Denken ganz zugedeckt. Das heutige naturwissenschaftliche Denken will nicht heran an eine wirkliche Menschenerkenntnis. Daher erlebt sich der Mensch heute — und er wird sich immer mehr und mehr so erleben -, indem er vieles in der Umwelt erkennt, so, daß er sich in seiner eigentlichen Wesenheit nicht erkennen kann. Der Mensch lebt sich heute gerade durch die gegenwärtige Wissens- und sonstige Bildung so herein, daß er von seiner eigenen Wesenheit im Grunde genommen nichts ergreift. Und immer mehr und mehr wird dieses zunehmen. Und wenn vollständig erfüllt werden könnte, was gewissermaßen dem Menschen direkt wird durch die einseitige naturwissenschaftliche Erkenntnis, so würde der Mensch seiner selbst völlig entfremdet werden. Sein inneres Individuelles würde sich heraufleben wollen, würde schmelzen wollen durch seine Wärme die Eismassen, die wir durch die Geburt ins irdische Dasein hereingetragen haben. Der Mensch würde seelisch zugrunde gehen an diesem Prozesse, der ihn innerlich überwältigt, der ja auch geschieht, wenn er ihn nicht erkennt, den er aber im Grunde genommen auf die Dauer nur ertragen kann, indem er ihn erkennt. Alle Zeichen der Zeit sprechen dafür, daß der Mensch zu solcher hier charakterisierter Selbsterkenntnis wirklich kommen muß. Und es ist einfach die Aufgabe des gegenwärtigen Geisteslebens in seinem Hinleben gegen die nächste Zukunft, diese Dinge der Kulturentwickelung wirklich einzuverleiben. Aber die bisherige Bildung hat große Massen von Furcht, große Massen von Antipathie aufgewendet gegen die Geltendmachung dessen, was der Menschheit so notwendig ist, wenn sie nicht im Untergang versinken will, sondern zu einem neuen Aufgang kommen will.

Fifth Lecture

[ 1 ] In order to maintain the context, I would like to briefly recapitulate what has come to our minds in recent days with regard to the understanding of the soul and spiritual life of human beings. In particular, I would like to preface what is necessary from the preceding discussion with regard to what still needs to be added for a certain preliminary conclusion of these considerations. Today I want to speak more about the results; I have already discussed the course of observation in the last few days.

[ 2 ] We have seen that there exists, as it were, in the space between the etheric body and the physical body, a fabric of living thoughts. What is this fabric of living thoughts? It is that which we bring with us from the spiritual-soul world into the earthly world through birth. It is necessary to imagine that what we have only in images within our thinking activity, what therefore only represents something within our thinking activity, has an independent life of its own, but is not contained in what we feel when we have thoughts, but that the web of thoughts is permeated by objective reality, that it is an active, weaving, working web of thoughts. This is true of human beings, that it participates in their formation, that it participates throughout their entire life between birth and death.

[ 3 ] Please take what I said last very seriously. One cannot say that in human beings this web of thoughts forms them entirely, that human beings are thus woven entirely out of what can be called world thoughts. That is not the case, at least not in relation to this web of thoughts that exists between the etheric and physical bodies. Human beings are also constituted by other things that come to them from the general cosmos, and what I have described as the web of thoughts is only interwoven with this. But we find it, so to speak, in the place where our subjective thinking also lies, for we weave our subjective thoughts into this web of thought. The objective thoughts do not appear at all to ordinary consciousness, but as the subjective thoughts, kindled by the external world, live their way into this web, what is the content of our thoughts comes into being for our consciousness.

[ 4 ] This, then, is man on one side, so to speak. It is man on the side of his skin, inasmuch as the skin is basically the sum of the senses. But as soon as we approach the sensory world itself today, the situation is such that we do not, so to speak, reach the senses by considering what human beings have been incorporated into by coming into existence through birth. We must draw the situation schematically in such a way that we say: If this is the thought web between the etheric body and the physical body (see drawing, light), then everything that is sensory life incorporated into the skin (red) wraps itself around this thought web. This is thus formed out of the cosmos, so to speak, and is attached to the human being. This is what human beings receive as a gift from the cosmos, so to speak, when they arrive at birth and bring with them what is initially in their thought fabric. And actually, when we speak of human beings as developing through Saturn, Sun, Moon, and Earth, as I have described in my “Outline of Esoteric Science,” we find at first mainly this outer development, beginning with Saturn, expressed precisely in the configuration of the sense organs. This then continues inward through processes in the glandular system, the nervous system, and so on, but what emanates from the senses is what human beings receive from the cosmos as their organization. But what I have drawn here as a web of thoughts is something that belongs to the individual human being, something that is separated from the etheric world when the human being enters into existence through birth, but which nevertheless belongs to the individual human being, that is, has to do with the individual earthly development of the human being. So we can say that this objective organization of thoughts works on us during our embryonic life and throughout our entire later life between birth and death, but it is not everything that constitutes the whole being of the human being.

[ 5 ] On the other hand, we have found what is of a volitional nature. And we can say: What is of a volitional nature develops between the astral body and the I. The I is actually, as it is in the human being, entirely of a volitional nature. But it develops in such a way that, as I have indicated, during the life between birth and death, the impulses of the will pass into the actions of the human being, but not completely; things remain behind. And what remains of the will passes into the karma that is becoming. So that when we look at the human being in terms of his physical body, we come to the web of thoughts according to past karma, and when we look at the human being in terms of his I — for it is the I that actually lives in his actions — one must be fully aware that the I actually lives completely only in actions, actually awakens only in human actions — then what the I retains within itself, so to speak, is carried through the gate of death and passes into future karma, into karma in the making.

[ 6 ] So, looking at it objectively, we find what is otherwise subjectively the soul life within us. We find it objectified. We find it in such a way that we can look at it objectively. But when we look at its relationship to the subjective, we find that on the one hand we have thought formations and on the other hand we have will formations. In the middle stands feeling, which represents subjective experience.

[ 7 ] This feeling can only be understood in its true essence when one realizes that every feeling that a person can experience individually is interwoven with the whole of human emotional life. And human emotional life can only be understood if we understand it in such a way that we say: in every moment of life, we are permeated, imbued with the totality of our emotional life. We could also say: we are in a certain emotional mood; in every moment of our lives we are in a certain emotional mood. Let us try to bring this emotional mood to consciousness — everyone can only do this individually at first. Let us try to bring to consciousness that we are human beings in a certain emotional mood at any moment of our earthly life. You know, this emotional state is infinitely varied. It is such that in one person it can degenerate into, I would say, excessive cheerfulness, so that one person is excessively cheerful, another suffers from depression, and a third is more evenly disposed. If we want to focus our attention solely on this emotional mood at any given moment in life, we do not need to go into the causes of these emotional moods, but only need to consider the particular shade, the particular nuance of this emotional mood: how it can lead to the deepest depression in one person, be balanced in another, and lead to cheerfulness, even extreme happiness, in a third; how there can be a thousand different stages in between. This emotional mood is actually different for every person. And now, when one inquires into this emotional mood through a kind of self-knowledge, one finds at first nothing other than subjective experience in this emotional mood, subjective experience that is nuanced in all kinds of ways precisely by external experiences, by external events; but one finds precisely subjective experience.

[ 8 ] If one remains in this subjective experience, that is, in the actual inner workings of the soul, without going into observation, that is, without going into the fact that these things become objective, one cannot at any moment enlighten oneself about the nature of, let us say, this emotional mood of the soul. But in ordinary life, one can already come to understand what this mood, this mood that lives entirely in feelings, actually is. To do this, however, one must have the ability to observe psychologically. One must have the opportunity to examine particularly striking personalities, perhaps once, for their emotional content. And there you can have the following experience. Of course, external observation can only give an approximation of the actual truth, but this approximation is already extremely valuable.

[ 9 ] We can, for example, set ourselves the task of studying Goethe, whom we can follow well through his diaries, letters, and what has flowed into his most significant works, where we can always see his moods clearly, since we can follow him biographically, sometimes from day to day, sometimes from morning to afternoon. One could, for example, set oneself the task of studying, in a subtle psychological manner, the mood that Goethe had at a certain point in time, say in 1790. One would first try to describe it as accurately as possible. One can do this; one can describe this mood as accurately as possible. And in doing so, however, one is pointed in two directions—and it is extremely important to bear this in mind—one is pointed in two directions: one is pointed to Goethe's life before 1790 and to what Goethe experienced after 1790. And when you then take a psychological look, as it were, at everything that penetrated Goethe's soul before 1790, together with what then affected his soul until his death – when you bring to mind his previous and subsequent life – then the wonderful thing emerges that every moment of mood in human beings represents an interaction between what has gone before, what the person knows, what is already consciously present in their life, and what is yet to come, that is, what is not yet part of their immediate conscious experience. However, what is initially unknown to one's own consciousness already lives in the general mood. One can, I would say, discover this secret of the mood of a moment in a biographical way. And with this one already borders on those areas of human observation that are readily disregarded by people who live thoughtlessly. What does the future matter to people? They do not know it yet — or so they think. In their emotional life, however, they do know it.

[ 10 ] And if you go further and examine, for example, the mood of someone you knew well and who, say, died a few years after you perceived this mood, died, you can see very clearly how the approaching death, with everything connected with it, has already cast its light back onto the mood. So that when one really goes into these things, one can see first of all the person's past life between birth and death, and then the future up to death playing into what lives together emotionally in the mood. That is why the mood life has something so inexplicable for the person themselves. That is why it enters into life as something elementary, because it is already tinged with feeling from what we are yet to experience.

[ 11 ] This matter had to be taken into account when I was writing my Philosophy of Freedom. Why did I have to insist that free action can only arise from pure thinking? Well, because if action is based on feeling, then the future already plays a role, and therefore no truly free action can ever arise from feeling! It can only arise from an impulse that is truly grasped in pure thinking. And if you remember what I have explained over the past two days, you will be able to grasp this even more deeply. I said: Just as feeling appears to us, it is initially the case that what actually happens within us, what goes on in our human nature, shines back into our consciousness in the form of feeling. If I draw a diagram, I can say that what flows upward into consciousness is the experience of feeling; but what flows downward is what can be experienced by the imaginative consciousness like dream images (see drawing on page 89), that is, what takes place entirely in the imagination. Thus, the life of feeling actually proceeds for the whole human being in such a way that what becomes conscious to us as feeling flows upward (blue), but what actually is image flows downward and inward into the human organization, which is then really seen as image when it is viewed through imaginative consciousness (red, inside). For ordinary consciousness, this flows down into the whole human being as something unconscious. Not in individual events, because these must first come to the fore—I ask you to understand this correctly—but in the overall mood of life, the result of a person's future experiences lives in them, as I might say, in a fundamental tone. Not as if the images of what happens live there, but the impressions of them live in the images.

[ 12 ] So you must not imagine these images flowing down as something like the future unfolding cinematographically, but rather as the result of impressions. Only in certain people who are atavistically clairvoyant can the images, which are then translated into images of certain facts, come to the fore, and then a certain glimpse into the near future can take place. But today we are primarily interested in the fact that what is sent down into people in a pictorial way is what is lived out in their emotional world.

[ 13 ] As we now move from feeling to will, what I have described to you as entering into the human being now penetrates outward and becomes his becoming karma, his future karma (red, outside). So that what arises in the human being through his feelings has, in a sense, something to do with his karma until his death; but what arises from the will has to do with his karma beyond death.

[ 14 ] It is therefore entirely possible to follow and study all these things in detail. As we move further and further in the development of anthroposophical spiritual science, we do not speak in a schematic way about mere concepts, but about concrete things that live in human beings and which, when brought to consciousness, give them insight into what they actually are. But you must have a strong sense of how the will, which is based on the life of feeling, actually works into the future, beyond death, how the will is the creator of the karma that is becoming.

[ 15 ] If we turn once more to the other side, to that web of thoughts that we have found and that really lives between the etheric body and the physical body in the human being, then we must be clear that when we experience something of the world through our sense impressions, thus forming a sensual worldview, we then process these sensory impressions mentally, and in processing them mentally, we actually weave ourselves into this web of thoughts with our subjectivity. We connect what we experience in our soul as a result of sensory impressions with what is integrated into us as a web of thoughts through birth; but the objective web of thoughts remains unconscious, and only what we weave into it, what we push into it, so to speak, from our inner thought activity, comes to our consciousness. It is actually as if the web of thoughts were there, the subjective thoughts strike it, strike into this web of thoughts, and this web of thoughts then reflects back our subjective thoughts, giving them all kinds of directions and thereby bringing our subjective thoughts to consciousness (see drawing on page 93). I say, giving them all kinds of directions.

[ 16 ] You see, when we perceive, say, some external object — I will describe the process to you in detail — for example, a cube, a crystal cube: we see it first. We do not stop at seeing. We think about it. But this thought continues on to the web of thoughts, and the web of thoughts that is integrated into us through birth, that we have thus acquired while we were in the cosmos, that we have also received through the cosmos, this web of thoughts is such that we now begin, based on certain premises, to form crystallographic ideas that we form from within ourselves. For example, when we form the ideas of the tesseral system, the tetragonal system, the rhombic system, the monoclinic system, the triclinic system, the hexagonal system, that is, when we conceive crystal systems in a mathematical-geometric way, we find that we can conceive crystal systems. This cube fits into the tesseral system that we have formed within ourselves. By incorporating something like the idea of the cube into what are, in a sense, a priori ideas that we take from within ourselves, we are directed toward the objective realm of thought at the moment when subjective thoughts arise. For what we develop as geometry, as purely geometric-mechanical physics and so on, we draw from this web of thoughts that is integrated into us at birth, and the individual, which we integrate into these thoughts, which we develop through external sensory perceptions and impressions, are those which we enlighten ourselves about by reflecting them back to ourselves, but allowing them to prevail with the formative web of thoughts that lives eternally within us, at least in terms of processes, if not in individual forms, for these change from incarnation to incarnation.