Cosmosophy I

GA 207

15 October 1921, Dornach

Lecture X

I want to look back once more at our recent observations. We have tried to get some picture of how the human life of spirit, the human soul life, and the human life of the body are to be comprehended. When we visualize the human soul life, that is, what the human being feels occurring within himself as thinking, feeling, and willing, then of course we find that the thinking component, or what we experience directly as the content of our thoughts, occurs between the physical body and the etheric body, that feeling occurs between the etheric body and the astral body, and willing between the astral body and the I. We thus see that our thoughts, insofar as we are fully conscious of them, represent only what glimmers up to us from the depths of our own being and really can give the waves of the soul life only their form. Something like shadows is cast upward from the depths of the human being, filling our consciousness and constituting the content of our thoughts.

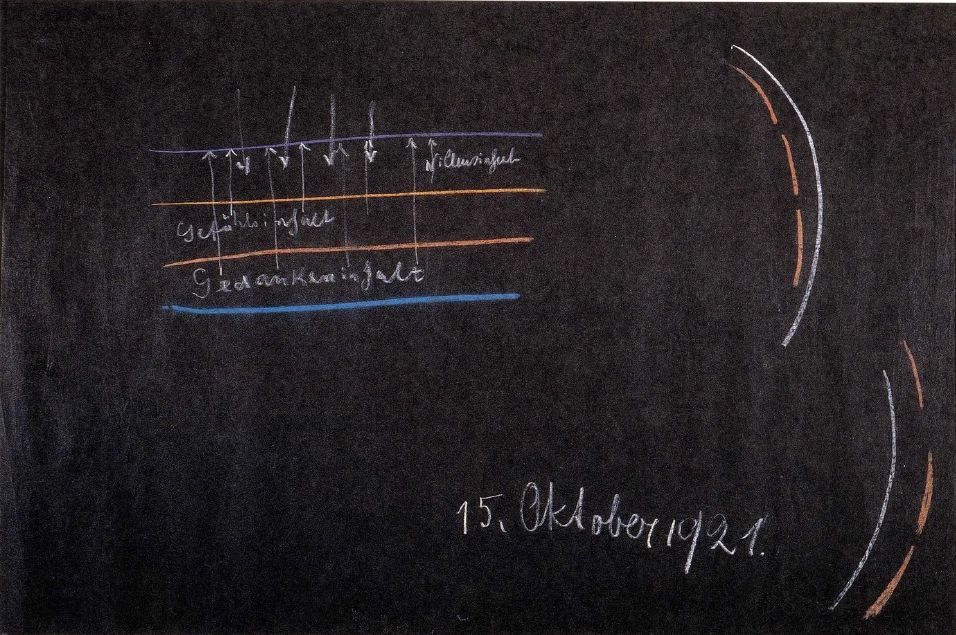

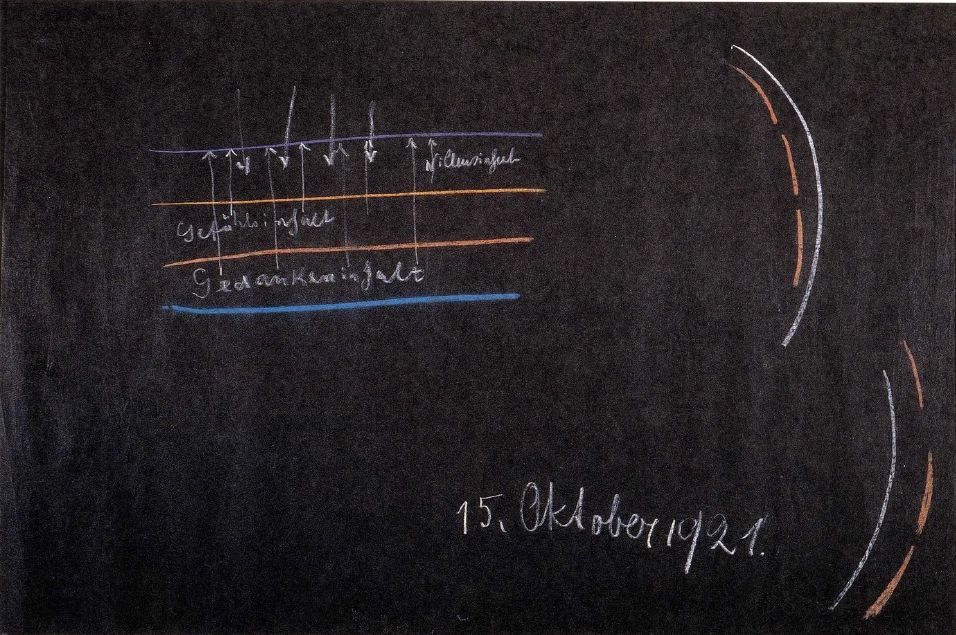

Were we to depict the matter schematically, we could render it in this way: physical body (see diagram, blue), etheric body (orange), astral body (red), and I (violet). Then we would have the thought content between the physical body and the etheric body. From my descriptions in the last lectures, however, you have realized that this thought content in its true nature is something much more real than what we experience in consciousness. What we experience in consciousness is, as I have said, only something that generates waves from the depths of our being up to the I. They rise up to the I. The feeling content lies between the etheric body and the astral body and in turn also rises up to the I; and the will content is located between the astral body and the I. It lies the closest to the I. We can say that the I has its most immediate experience of itself in the will, while feeling content and thought content rest in the depths of our being and only send their waves lapping upward into the I.

Now we also know, however, that the content of our willing, as experienced by us, is experienced dully. Of the will, as it manifests itself in an arm movement, in a leg movement, we know as little as we do of what happens between going to sleep and awaking. The will lives in us dully, and yet it lives really within the I as the I's most immediate neighbor. If we perceive the will consciously or, let us say, in an awake manner, we do so only through the projected thought shadows that come up from the depths of our being. The mental images that we experience consciously are the shadow pictures of a deep weaving of the soul but they are still only shadow pictures, while we experience the will in a most immediate way, though dully. We can have a waking, conscious perception of the will, however, only through the shadowy thought pictures.

This is how the matter appears to us when we study our human nature while focusing in particular on the inner depths. We see, I would like to say, how little of ourselves we contain in our consciousness, how little rises upward from our inner being to our consciousness. We understand, as it were, only little of what we are like on the inside in terms of our I, and we really perceive only the hue that our thought content casts upward into this dull, will-oriented I.

With our ordinary consciousness, we can actually see as an immediate reality little more of this thought-filled, dull I than what we feel of it shortly before awakening or shortly after dropping off to sleep. It is precisely into this dull I, however, that the world of sense perceptions breaks upon awakening. Just try to become aware once of how dull your life is between going to sleep and awakening, so that you experience this dullness almost as a void. Only upon awakening, when you open your senses to the outside world, will you be in a position—thanks to your sense impressions—really to experience yourself as an I. Now the appearance [Schein] of the sense perceptions penetrates the I. Now the appearance of the sense perceptions fills that dull being that I have just described, so really the I lives as a fully conscious entity in the earthly human being only when we are in a state of interaction with the outside world through our sensory pictures and through all that has penetrated our senses; and coming from within as the most illuminating response we can muster is the shadowed content of our thoughts.

One can say, then, that the sense perceptions penetrate in from without. The content of our willing is perceived only dully. The feeling content rises upward and unites with the sense impressions. We see red, and it fills us with a particular feeling; we see blue, we hear the notes C-sharp or C and have an accompanying feeling. Then, however, we also reflect on what these sense impressions are. The thought content, which comes from within interweaves itself with the sense impressions. Something from within unites with something from without. That we live in the fully awake I, however—this we actually 'owe to the appearance of the senses (Sinneschein), and to this our I contributes just so much by way of response from within as I have been able to describe here.

Let us note well this appearance of the senses. Let us look upon it and realize clearly that it is entirely dependent on our physical existence. It can fill us only as we, in waking condition, put forward our physical body to meet the outer world. This appearance of the senses ceases at the moment we lay down our physical body upon passage through the portal of death, as we have already discussed in the previous studies.

Our I, then, is awakened, as it were, between birth and death through the appearance of the senses. Of our actual nature as awake, earthly human beings, we can possess only so much as is enlivened by the appearance of the senses. Imagine vividly how the being that is the human I grasps this appearance of the senses—which is, after all, only an appearance—and interweaves it with our actual human being. Now consider how there an outer becomes an inner—you can see it, for example, when you dream; consider how a delicate tissue is spun inside of us, as it were, into which the sense impressions weave. The I appropriates what comes in through the sense impressions. The outer becomes inner. Only what does become inner, however, can carry the human being through the portal of death.

It thus is only a delicate tissue to begin with that the human being carries through the portal of death. His physical body he lays down. It had mediated the sense impressions for him. Therefore the sense impressions are only appearance, for the physical body is laid aside. Only so much of the appearance as the I has taken up into itself is borne through the portal of death. The etheric body is also laid aside a short time after death. When that happens, however, our being also lays aside what is between the physical body and the etheric body. This at first dissolves, as we have seen, in the cosmos at large, constituting only the seed for further worlds, but it does not really continue to live together with our human essence after death. Only what has crested upward like waves and has combined itself with the appearance of the senses continues to live. When this is pondered, one can acquire an approximate mental image of what the human being carries through the portal of death.

Because this is so, one must answer the question, “How can someone build a connecting bridge to a departed person?” in the following way: this connecting bridge cannot be built at all if we send abstract thoughts, non-pictorial mental images over to the departed human being. If we think of the departed one with abstract mental images—what is that like? Abstract mental images retain almost nothing of the appearance of the senses; they are faded, but also there lives in them nothing of an inner reality but only what is cast up to them from the inner reality. Only a tinge of the human essence resides in mental images. Therefore, what we grasp with our intellect is in truth much less real than what fills our I in the appearance of the senses. What fills our I in the appearance of the senses makes our I awake, but this wakeful content is only interspersed with the waves that crest upward from our inner being. If we therefore direct abstract, faded thoughts to a departed person, he cannot have community with us; he can do so very well, however, if we picture to ourselves quite intimately and concretely how we stood with him on such-and-such a spot, how we talked with him, how he asked us for this or that in his particular way. The thought content, the pallid thought content, will not yield much, but it will be much more effective if we develop a fine sensitivity for the sound of his speech, for the special kind of emotion or temperament with which he held conversation with us, if we feel the living, warm togetherness along with his wishes—in short, if we picture these concrete things but in such a way that our mental images are pictures: if we see ourselves, as we stood or sat together, as we experienced the world with him. One might easily believe that it is precisely the pallid thoughts that arc across death's gap. This is not the case. The vivid pictures arc across. In pictures from the appearance of the senses, in pictures that we have only owing to the fact of our eyes and ears, our sense of touch, and so on—in such pictures there stirs something that the dead person can perceive. For at death he has laid aside everything that is only abstract, pallid, intellectual thinking. Our pictorial mental images, insofar as we have made them our own, we do take with us through death. Our science, our intellectual thinking, all of that we do not take along through death. A person may be a great mathematician, may have myriad geometrical conceptions—all this he lays aside just as he does his physical body. The person may know a great deal about the starry skies and the surface of the earth. Insofar as he has absorbed this knowledge in pallid thoughts it is laid aside at death. If, as a learned botanist, a person crosses a meadow and entertains his theoretical thoughts about the flowers of the meadow, then this is a thought content that fulfills him only here on earth. Only what strikes his eye and is colored by his love for the flowers, what is given human warmth by the union of the pallid thought with the I experience, is carried through death's portal.

It is important that one know what can be acquired here on earth as real, human property in such a way that one can carry it through the portal of death. It is important that one know how the whole of intellectualism, which has comprised the centerpiece of human civilization since the middle of the fifteenth century, is something that has significance only in earthly life and that cannot be borne through the portal of death. One thus can say: the human race has lived throughout the past ages of which we have spoken—beginning with the Atlantean catastrophe, throughout the long ages of the ancient Indian civilization, the ancient Persian civilization, through the Egyptian-Chaldean times, and then through our era up to our time—the human race has not lived in all this time, that is to say up to the first third or so of the fifteenth century, such an outspokenly intellectual life as the one we hold so dear today as our civilized life. Before the fifteenth century, however, human beings experienced much more of everything that could be borne through the portal of death. Precisely what they have become proud of since the fifteenth century, precisely what makes life worth living for the cultured, the so-called cultured, world today, is something that is obliterated upon death. One could really ask, what is the characteristic feature of modern civilization? The most characteristic feature of all, which is so praised as having been brought about through Copernicanism, through Galileanism, is something that must be laid aside at death, something that the human being really can acquire only through earthly life, but also something that can be only an earthly possession for him. By developing himself up to modern civilization, man has attained precisely this goal of experiencing here between birth and death all those things that have significance only for the earth. It is very important for modern man to understand thoroughly that the content of what is regarded most highly, and especially in our schools, has an actual significance only for earthly life. In our ordinary schools, we instruct our children in everything that is modern civilization, not for their immortal soul but only for their earthly existence.

Intellectualism can be grasped correctly in the following manner. When the human being awakens in the morning, the sensory pictures come streaming in to him. He notices only that the thoughts interweave these sensory pictures like a delicate net, and he is actually living in pictures. These pictures vanish immediately when he falls asleep in the evening. His thought life vanishes too, but the appearance of these sensory pictures is nevertheless essential, for he takes with him through death as much of this as his I has made its own. What comes from within—the thought content—remains, as you know, for a few days after death in the form of a brief recollection, so long as the human being still bears the etheric body. Then the etheric body dissolves itself into the far reaches of the cosmos. There is a brief experience for the human being immediately after death regarding his pictures that contain the senses' appearance, insofar as his I has made it his own: he feels these pictures interwoven then by strong lines with what he has made his own through his knowledge. He lays this brief experience aside, however, along with his etheric body, a few days after death. Then he lives into the cosmos with his pictures, and these pictures become interwoven into the cosmos in the same way in which they were interwoven into his own being before death. Before death, the pictures in the sense perceptions are formed from within. They are grasped by the human being, I might say, insofar as it is delimited by his skin. After death, after passage of the few days when one still experiences the thought life—because one still has the etheric body, before the etheric body's dissolution—after these days the pictures become in a certain way larger. They expand in such a way that they now are absorbed from without, as it were, while during earthly life they were absorbed from within. Schematically one could draw the entire process, as shown below.

If this is the bodily boundary of the human being (see drawing, bright) and he has his impressions in the waking state, then his inner experiences are formed by the sense impressions within his being. After death, the human being experiences his boundary as an encompassing feeling; but his impressions wander out of him, as it were. He senses them to be in his surroundings (red). Thus a person who during earthly life could say, “My soul experiences are inside of me,” now says to himself, after death, “My soul experiences are in front of me,” or, said better, “They are all around me.” They merge with the surroundings. Because of this they also become inwardly different. Let us say, for example, that this person, because he loves flowers, has strongly impressed upon himself in ever-repeated sense impressions a rose, a red rose; then, when after death he experiences this wandering out, he will see the rose larger, visibly larger, but it will appear to him greenish in color. The inner content of the picture also changes. Everything that the person has perceived of nature's green, insofar as he really has experienced this green nature with human participation, not merely with abstract thoughts, now becomes for him after death a gentle reddish environment of his whole being. The inner, however, wanders out: what the person calls his inner being he will have after death in his environment outside.

These realizations, then, which concern the human being, insofar as he in turn is connected to the world itself, we can acquire through spiritual science. Only by acquiring these insights do we receive a picture of what we ourselves actually are. We cannot get a picture of what we ourselves really are if we know ourselves only as we are between birth and death, with our inwardly woven thoughts. For these are the things that as such fall away at death. Of the senses' appearance there remains only what I have just depicted to you, and it remains in the way I have described.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, when the materialistic outlook and world conception of civilized humanity had reached a culmination, as I have often emphasized, there was much talk of how the human being, when he founds a religion or when he speaks of something divine-spiritual in the outer world, really only projects his inner being to the outside. You need only read such a thoroughly materialistic writer as Feuerbach,15Ludwig Feuerbach, 1804–1872. who had a strong influence on Richard Wagner, in order to recognize how this materialistic thinking sees nature as being all there is out there. That is to say, this materialistic attitude sees only the appearance of nature in the form in which it presents itself to us between birth and death and then believes that all thinking about the divine-spiritual is only the inner being of man projected outward. The result is that man feels comfortable only with the concept of the divine-spiritual as a projection of his inner being. This seeming insight received the name anthropomorphism. It was said that the human being is anthropomorphic; he pictures the world according to what lies within him. Then, of course, in the middle of the nineteenth century, the more representative among these materialistic thinkers coined a slogan that was meant to illustrate how splendidly advanced the world of human beings had now become in our modern age. They said: “The ancients believed that God created the world. We moderns, however, know that man created God; that is, God is a projection of man's inner being.” They said and believed this precisely because all they knew of our inner side was what has significance between birth and death. I reality it was not just an erroneous opinion that they formed; rather, they had formed a world view that was in fact anthropomorphic, for they had no other notions of the divine-spiritual than those that the human being had managed at last to cast, to project, out of himself.

Compare with that everything that I have described, for example, in my book, An Outline of Occult Science. There you will not see the world described like our human mental images from within. What I describe there as Saturn, Sun, Moon, and Earth evolutions the human being does not carry within him. One must first treat what the human being experiences after death, that is, what he can place in front of himself. There is nothing anthropomorphic here. This Occult Science is presented cosmomorphically; that is, the impressions are such that they are actually experienced as existing outside of the human being. These things therefore cannot be understood by those people who can experience in their conceptions only what lies within the human being, as has come to be the case especially in the intellectual age since the middle of the fifteenth century. This age perceives only what resides in the inner being of man and projects it outward. Never will one be able to describe an outer world as I do in that chapter of my Occult Science where the Saturn evolution is treated—not even in the simplest, most elementary phenomenon—if one only projects outside what exists in the inner being of man.

You see, the human being lives, for example, in warmth. Just as he perceives the world in color through his sense of sight, so he also perceives the world in warmth through his sense of warmth. He experiences the warmth in his human inner being, I might call it, insofar as it is delimited by his skin. Already, however, he is abstracting in his perception. Warmth perceived in the life of the world really cannot be pictured otherwise than by grasping it in its totality. There is always something adhering to warmth, however, which in terms of human experience can be expressed only by referring to the sense of smell. Warmth, perceived objectively outside ourselves, always has something of scent associated with it too.

Now read the chapter in my Occult Science about that process of our earth that lives chiefly in warmth: where these things are described you will find simultaneous mention of scent impressions. You see from this that warmth is not described in the same way in which man experiences it in intellectualism. It is placed outside the human being, and what he experiences here between birth and death as warmth comes back after death as a scent impression.

Light is something that the human being experiences really quite abstractly here on earth. He experiences this light by surrendering to a continuous deception. I'd like to point to it here too: I have written—let me see, it must be thirty-eight years ago now—a treatise, very young and green, in which I attempted to describe how people speak of light. But where is the light anyway? Man perceives colors; those are his sense impressions. Wherever he looks: colors, he perceives some shadings of colors even when he knows it is a shade. But light—he lives in light, and yet he doesn't perceive the light; through the light he perceives colors, but the light itself he does not perceive. You may gauge the degree of the illusions in which we live in this regard in the age of intellectualism when you consider that our physics offers a “theory of light”; then we attempt to give it some substance by considering it “a theory of light.” It has no substance. Only a theory of color has substance, not a theory of light.

Only the entirely healthy nature-appreciation of Goethe could suffice to create not a science of optics but a theory of color. We open our physics books nowadays and there we see light being created from scratch, as it were. Rays are constructed and reflected, and they perform all kinds of tricks. But it isn't real! One sees color. One can speak of a theory of color but not of a theory of light. One lives in light. Through the light and in the light we perceive color, but nothing of the light. No one can see the light. Imagine being in a space with light streaming through it, but there is not a single object in this space. You might as well be in the dark. In a space that is completely dark you would perceive no more than in the naked light, nor would you be able to differentiate between the two. You could differentiate only through an inner experience. As soon as a human being has gone through the portal of death, however, then, just as he perceived the scent that accompanied warmth he now perceives something about the light for which we in our present-day intellectual language do not even have an appropriate word. We would have to say: smoke [Rauch]; a flooding forth—he really perceives it. Hebrew still had something like that: Ruach. This flooding forth is perceived. That which alone could justifiably be called air is perceived there.

If we now consider what appears everywhere in our earthly circumstances as chemical reactions, we perceive them in their appearances, these chemical workings, these chemical etheric workings. Spiritually seen, without the physical body—again, therefore, after death—they provide what is the content of water.

And life itself: it is what comprises the content of the earth, of the solidity. Our entire earth is perceived from the viewpoint of the dead person as a large, living being. When we walk about here on earth, we perceive its separate entities, insofar as they are earthly entities, as being dead. On what do we base our perception of dead things at all, however? The entire earth lives, and it reveals itself immediately to us in its life if we glimpse it from the other side of death. If that is our earth, we only see a very small portion of it at any one time and are oriented to seeing just this small portion—only when we hover about it in spirit and moreover have outwardly an ability to perceive from without, so that the impressions are enlarged, do we perceive it as a whole being. Then, however, it is a living being.

With this, I have directed your attention to something that is extraordinarily important to call to mind

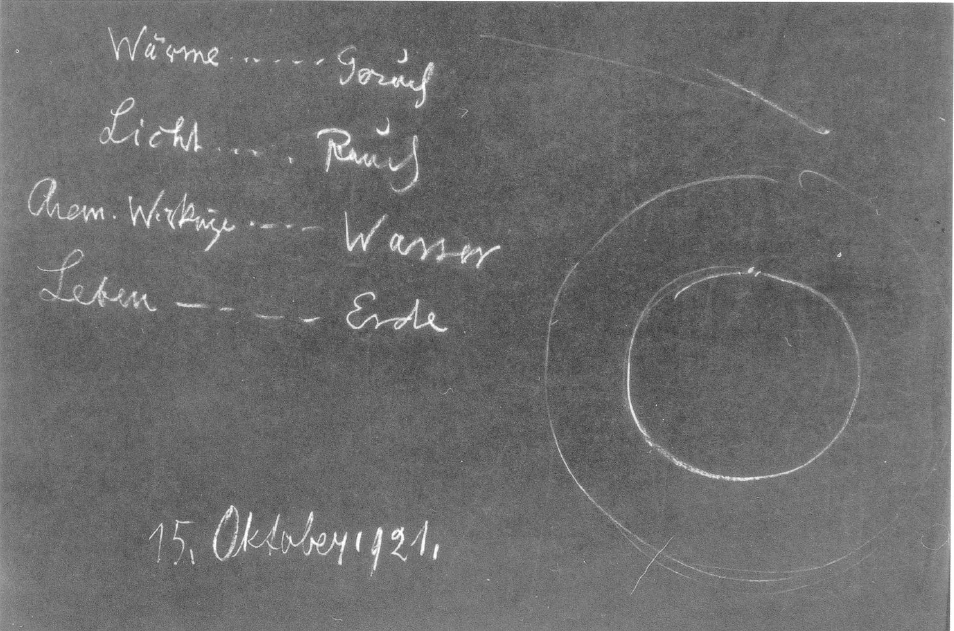

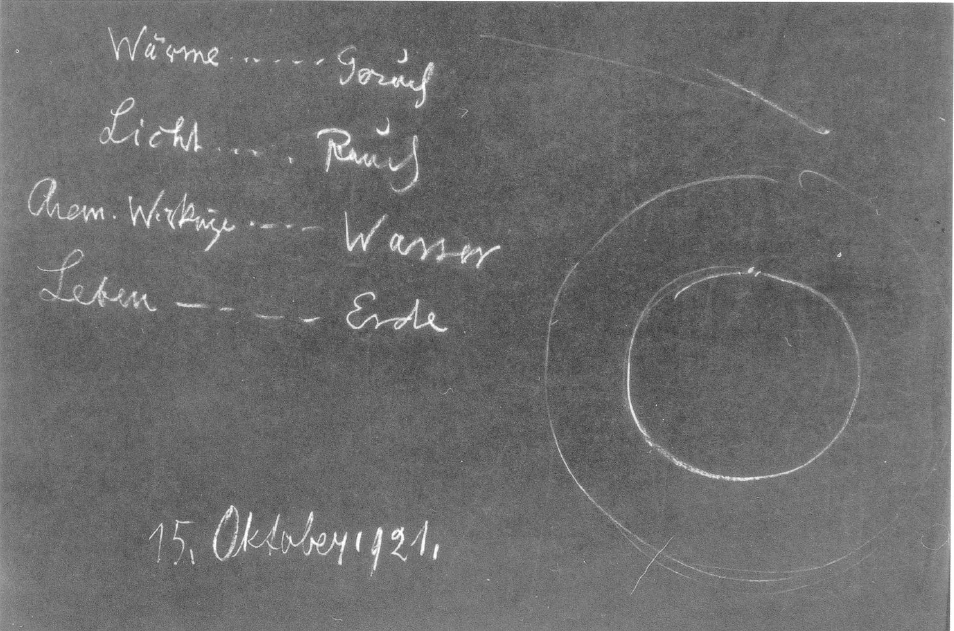

Warmth: | Scent |

Light: | Smoke, Air |

Chemical workings: | Water |

Life: | Earth |

You see, I had a conversation once with a gentleman who said that we now know, finally, thanks to the theory of relativity, that we could just as well imagine the human being to be twice as large as he really is; it's all relative, everything just depends on the human viewpoint.

This is a completely unrealistic way of looking at the matter. For let us say—the picture doesn't quite fit, but let us say—if a ladybug is crawling about on a person, it has then a particular size in relation to that person. The ladybug doesn't perceive the entire human being but, in keeping with its own size, just a small portion of the person. And so for the ladybug the person on which it is crawling about is not living but rather is just as dead to the ladybug as the earth is to the human being. You must also be able to think this thought the other way around. You must be able to say to yourself: in order to be able to experience the earth as being dead, the human being must be of a particular size upon the earth. The size of the human being is not a coincidence in relation to the earth but is completely appropriate to man's entire life upon the earth. Therefore you cannot think of man—for example, in keeping with the relativity theory—as being big or little. Only if you think and imagine quite abstractly, quite intellectually, that man is big or little; only then can you say, “If we were organized a bit differently, man might appear twice as big,” and the like.

This stops when we take up a conception that goes beyond the subjective and that can keep in mind man's size in relation to the earth. After death the whole human being expands out into the universe and after a time following death man becomes much larger than the earth itself. Then he experiences it as a living being. Then he experiences chemical workings in everything that is water. In the airiness he experiences light, not light and air separately from one another but light in the air, and so on. The human being experiences, then, different pictures from those of our waking life between birth and death.

I said that we can take with us through death nothing of all that our soul has acquired in an intellectual way. Before the fifteenth century, however, man still possessed a kind of legacy from ancient times. You know, of course, that in ancient times this legacy was so great that the human being still had an atavistic clairvoyance, which then paled and dulled, withered away, and which has passed over into complete abstraction since the middle of the fifteenth century. What the human being took with him through death of this divine legacy, however, is what actually gave man his being. Just as the human being here assimilates physical matter when he enters earthly existence via birth, or rather conception, so also was it the divine essence that he brought with him and carried again through death that gave him—the expression, if I may use it at all, is unusual, but will help make this clear to you—gave him a certain spiritual weight (a polar opposite, naturally, of any physical weight). The divine essence which he brought along and took with him through death gave him a certain spiritual weight.

The way people are being incarnated now, if they are really members of civilization, they no longer have this legacy with them. At most you can still detect it here and there: those people who are not really of our civilization (and they are becoming ever fewer) still have it in them. And it is a serious matter indeed for the evolution of humanity that the human being essentially loses his being through what he acquires through intellectual civilization. He is heading toward this danger, that after death he will, to be sure, grow outward so as to have the aforementioned impressions, but he can lose his actual being, his ‘I’, as I have already described yesterday from a different viewpoint. There is really only one avenue of rescue for this being, for modern and future man, and it may be recognized in the following: if we wish, here in the sense world, to take hold of a reality that makes thinking so powerful that it is not merely a pale image but has inner vitality, then we can recognize such a reality issuing from within the human being only in the kind of pure thinking that I have described in my Philosophy of Freedom as forming the basis for action. Otherwise we have in all human consciousness only the senses' appearance. If we act freely out of pure thinking, however, such as I have described in my Philosophy of Freedom, if we really have in pure thinking the impulses for our actions, then we give to this otherwise “appearance” thinking, to this intellectual thinking—in that it forms the basis of our actions—a reality. And that is the one reality that we can weave purely from within out into the senses' appearance and can carry with us through death.

What, then, are we really taking with us through death? What we have experienced here between birth and death in true freedom. Those actions that correspond to the description of freedom in my Philosophy of Freedom form the basis for what man can carry through death in addition to the senses' appearance, transformed in the way that I have described. Thereby he regains his being. By freeing himself from being determined in the world of the senses, he regains a being after death; he is thereby a real being. If we acquire this being, it is freedom that saves us as human souls from soul-spiritual death, saves us especially for the future.

Those people who abandon themselves only to their natural forces, that is, to their instincts and drives—I have described this from a purely philosophical standpoint in my Philosophy of Freedom—live in something that falls away with death. They then live into the spiritual world. To be sure, their pictures are there. They would gradually have to be taken by other spiritual beings, however, if the human being did not develop himself fully along the lines of freedom so that he might again acquire a being such as he had when he still possessed his divine-spiritual legacy.

The intellectual age thus is inwardly connected with freedom. That is why I could always say: the human being had to become intellectual so that he might become free. The human being loses his spiritual being in intellectualism, for he can carry nothing of intellectualism through the portal of death. He attains freedom here through intellectualism, however, and what he thus acquires in freedom—this he can take through the portal of death.

Man may think as much as he wants in a merely intellectual way—nothing of it goes through death's portal. Only when the human being uses his thinking in order to apply it in free deeds does that amount of it that he has acquired from his experiences of freedom go with him through death's portal as soul-spiritual substance, which makes him a being and not a mere knowing. In thinking, through intellectualism, our human essence is taken from us, in order to let us work through to freedom. What we experience in freedom is in turn given back to us as human essence. Intellectualism kills us, but it also gives us life. It lets us arise once again with our being totally transformed, making us into free human beings.

Today I have presented this as it appears in terms of the human being himself. What I have thus characterized today in terms of the human being alone I shall connect tomorrow with the Mystery of Golgotha, with the Christ experience, in order to show how in death and resurrection the Christ experience can now pour into the human being as inner experience. More of this tomorrow.

Zehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Ich will noch einmal zurückblicken auf die letzten Betrachtungen. Wir haben versucht, uns Vorstellungen zu machen darüber, wie das menschliche Geistesleben, das menschliche Seelenleben und das menschliche Leibesleben zu begreifen sind. Wenn wir uns das menschliche Seelenleben vor Augen stellen, also das, was der Mensch als Inneres in sich ablaufen fühlt als Denken, Fühlen und Wollen, so finden wir ja, daß das Denkerische, also das, was unmittelbar erlebt wird als Gedankeninhalt, sich abspielt zwischen dem physischen Leibe und dem Ätherleibe, daß sich dann abspielt das Fühlen zwischen dem Ätherleibe und dem astralischen Leibe, das Wollen zwischen dem astralischen Leibe und dem Ich. Wir sehen daraus, daß die Gedanken, insofern wir uns ihrer voll bewußt sind, nur darstellen, was wie aus den Tiefen des eigenen Wesens heraufblickt und den Wellen des Seelenlebens eigentlich nur die Form geben kann. So etwas wie Schatten schlagen aus den Tiefen des menschlichen Wesens herauf, erfüllen unser Bewußtsein und sind dann der Gedankeninhalt.

[ 2 ] Wenn wir uns die Sache schematisch darstellen wollten, so könnten wir uns sagen: Physischer Leib (siehe Zeichnung, blau), Ätherleib (orange), astralischer Leib (gelb) und Ich (violett). Dann würden wir zwischen dem physischen Leib und dem Ätherleib den Gedankeninhalt haben. — Aber Sie haben aus meinen Schilderungen der letzten Vorträge ersehen, daß dieser Gedankeninhalt in seiner Wahrheit etwas viel Realeres ist als das, was wir im Bewußtsein erleben. Was wir im Bewußtsein erleben, das ist ja nur etwas, was eben, wie ich sagte, aus der Tiefe unseres Wesens die Wellen heraufschlägt bis zum Ich. Da schlägt es herauf. Der Gefühlsinhalt liegt zwischen Ätherleib und astralischem Leib und schlägt wiederum bis zum Ich herauf, und der Willensinhalt, der ist dann zwischen dem astralischen Leib und dem Ich. Der liegt also dem Ich am nächsten. Wir können sagen: In dem Willen erlebt sich das Ich in seiner unmittelbarsten Art, während Gefühlsinhalt und Gedankeninhalt in den Tiefen unseres Wesens ruhen und nur eben die Wellen heraufschlagen in unser Ich.

[ 3 ] Nun aber wissen wir ja auch, daß das Wollen, daß der Willensinhalt, wie er von uns erlebt wird, dumpf erlebt wird. Von dem Willen, wie er, sagen wir, in einer Armbewegung, in einer Beinbewegung lebt, wissen wir nicht mehr als wir von dem wissen, was sich abspielt zwischen dem Einschlafen und Aufwachen. Der Wille lebt dumpf in uns. Dennoch ist er das, was in unserem eigentlichen Ich als das ihm Nächste lebt. Bewußt, oder sagen wir wachend, nehmen wir den Willen nur wiederum durch die Gedankenabschattungen wahr, die aus den Tiefen des Wesens heraufkommen. Die Vorstellungen, die wir bewußt erleben, sind Schattenbilder eines tiefen seelischen Webens; aber sie sind eben nur Schattenbilder, während wir allerdings den Willen unmittelbar, aber dumpf erleben. Ein waches Bewußtsein vom Willen können wir aber doch nur haben durch die schattenhaften Gedankenbilder.

[ 4 ] So erscheint uns die Sache, wenn wir unsere menschliche Wesenheit betrachten und dabei auf die Tiefe des Inneren sehen. Wir sehen, wie, ich möchte sagen, wenig wir von uns selbst in unserem Bewußtsein enthalten, wie wenig da heraufschlägt von dem Inneren unseres Wesens in unser Bewußtsein. Wir verstehen gewissermaßen nur wenig, was wir dem Ich nach im Inneren sind, und nehmen eigentlich nur wahr die Tingierung, welche der Gedankeninhalt heraufwirft in dieses dumpfe, willenshafte Ich.

[ 5 ] Man kann eigentlich mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein von diesem gedankenerfüllten dumpfen Ich kaum mehr als ein unmittelbar Wirkliches sehen, als dasjenige ist, was wir etwa kurz vor dem Aufwachen oder kurz nach dem Einschlafen als unser dumpfes Ich empfinden. Aber in dieses dumpfe Ich schlägt ja eben mit dem Aufwachen die Welt der Sinneswahrnehmungen ein. Werden Sie sich nur einmal bewußt, wie Ihr Leben zwischen dem Einschlafen und dem Aufwachen dumpf ist, so daß Sie die Dumpfheit fast als leer empfinden. Und erst mit dem Aufwachen, wenn Sie die Sinne nach außen öffnen, die Sinneseindrücke kommen, sind Sie an der Hand der Sinneseindrücke in der Lage, sich als Ich wirklich zu empfinden. Da schlägt der Schein der Sinneswahrnehmungen in das Ich herein. Da erfüllt jenes dumpfe Wesen, von dem ich eben gesprochen habe, der Schein der Sinneswahrnehmungen. So daß das Ich als vollbewußtes im Erdenmenschen eigentlich nur lebt in demjenigen Zustande, in dem er durch die Sinnesbilder, durch alles das, was in seine Sinne hereindringt, in Verkehr mit der Außenwelt gekommen ist, und es tritt dann von innen entgegen noch als das Hellste, noch als das, was am meisten aufhellt, der abgeschattete Gedankeninhalt.

[ 6 ] Man kann also sagen: DieSinneswahrnehmungen dringen von außen herein. Der Willensinhalt wird nur dumpf wahrgenommen. Der Gefühlsinhalt schlägt herauf, verbindet sich mit den Sinneseindrücken. Wir sehen Rot, es erfüllt uns mit einem gewissen Gefühl; wir sehen Blau, wir hören Cis oder C und fühlen etwas dabei. Dann machen wir uns aber auch Vorstellungen über das, was die Sinneseindrücke sind. Der Gedankeninhalt, der von innen kommt, verwebt sich mit den Sinneseindrücken. Inneres verbindet sich mit Außerem. Aber daß wir im vollen wachen Ich leben, das verdanken wir eigentlich dem Sinnenschein, und unser Ich steuert dazu so viel bei, als eben jetzt beschrieben werden konnte von dem, was da entgegenschlägt dem Außeren.

[ 7 ] Beachten wir wohl diesen Sinnenschein. Sehen wir auf ihn hin und seien wir uns klar darüber: er hängt ganz und gar an unserem physischen Dasein. Er kann uns nur erfüllen, indem wir unseren physischen Leib der Außenwelt im wachenden Zustande entgegenstellen. Dieser Sinnenschein, er hört auf in dem Augenblicke, wo wir, durch den Tod gehend, unseren physischen Leib ablegen in dem Sinne, wie wir das in den vorangehenden Betrachtungen besprochen haben.

[ 8 ] Zwischen Geburt und Tod wird also gewissermaßen unser Ich erweckt durch den Sinnenschein. Wir können von unserem eigentlichen Wesen als wache Erdenmenschen nur soviel haben, als sich an diesem Sinnenschein eben belebt. Stellen Sie sich jetzt lebhaft vor, wie das menschliche Ich-Wesen den Sinnenschein, der ja eben nur ein Schein ist, auffängt und ihn mit dem eigenen menschlichen Wesen verwebt. Nun bedenken Sie, wie da ein Äußeres ein Inneres wird, wie — Sie können es ja am Traum sehen -, ich möchte sagen, ein ganz feines Gewebe innerlich gesponnen wird, in das sich die Sinneseindrücke einweben. Das Ich bemächtigt sich dessen, was da durch die Sinneseindrücke kommt. Das Äußere wird Innerliches. Aber nur das, was innerlich wird, kann der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes tragen.

[ 9 ] Es ist also ein feines Gewebe zunächst, das der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes trägt. Seinen physischen Leib legt er ab. Der vermittelte ihm die Sinneseindrücke. Daher sind die Sinneseindrücke ja nur Schein, denn der physische Leib wird abgelegt. Nur so viel, als das Ich von dem Schein in sich aufgenommen hat, wird durch die Pforte des Todes getragen. Der ätherische Leib wird auch abgelegt kurze Zeit nach dem Tode. Damit aber wird das, was zwischen dem physischen Leib und dem ätherischen Leib ist, von dem eigenen Wesen abgelegt. Das löst sich, wie wir gesehen haben, im allgemeinen Kosmos zunächst auf, bildet nur den Keim für weitere Welten, lebt aber eigentlich mit unserem Menschenwesen nach dem Tode nicht weiter zusammen, sondern nur das lebt weiter, was an Wellen heraufgeschlagen und sich mit dem Sinnenschein verbunden hat. Wenn man das erwägt, so kann man ungefähr eine Vorstellung bekommen von dem, was der Mensch durch des Todes Pforte trägt.

[ 10 ] Aus diesem Grunde, weil das so ist, muß man ja, wenn man gefragt wird: Wie kann jemand eine Verbindungsbrücke bauen zu einem hingegangenen Menschen? — folgendes sagen: Diese Verbindungsbrücke, man kann sie nicht bauen, wenn man abstrakte Gedanken, unanschauliche Vorstellungen zu dem verstorbenen Menschen hinschickt. Wenn man an den verstorbenen Menschen mit abstrakten Vorstellungen denkt — wie ist es denn da? Abstrakte Vorstellungen haben vom Sinnenschein fast nichts mehr, sie sind abgeblaßt, aber es lebt in ihnen auch nichts innerlich Wirkliches, sondern nur dasjenige, was heraufschlägt aus dem innerlich Wirklichen. Nur eine Tingierung mit dem menschlichen Wesen lebt in abstrakten Vorstellungen. Was wir also durch unseren Intellekt auffassen, das ist ja viel weniger wirklich als das, was im Sinnenschein unser Ich erfüllt. Was im Sinnenschein unser Ich erfüllt, macht unser Ich wach. Aber nur durchsetzt wird dieser wache Inhalt mit den Wogen, die aus dem eigenen Inneren heraufschlagen. Wenn wir also abstrakte, verblaßte Gedanken an einen Toten richten, kann er mit uns nicht Gemeinschaft haben; wohl aber, wenn wir uns recht innerlich konkret vorstellen, wie wir mit ihm da oder dort zusammengestanden haben, wie wir mit ihm gesprochen haben, wie er das oder jenes durch sein eigenes Sprechen von uns gewollt hat. Der Gedankeninhalt, der blasse Gedankeninhalt wird nicht viel fruchten, wohl aber, wenn wir eine feine Empfindung entwickeln für den Klang seiner Sprache, für die besondere Art von Emotion oder Temperament, mit dem er sich mit uns unterhalten hat, wenn wir das lebendig warme Zusammensein mit seinen Wünschen fühlen, kurz, wenn wir uns dieses Konkrete vorstellen, aber so, daß unsere Vorstellungen Bilder sind: wenn wir uns selber sehen, wie wir mit ihm zusammengestanden oder zusammengesessen haben, wie wir die Welt mit ihm erlebt haben. Leicht könnte man glauben, daß über den Tod hinüber gerade die blassen Gedanken spielen. Das ist nicht der Fall. Die anschaulichen Bilder spielen über den Tod hinüber. Und in Bildern des Sinnenscheins, in Bildern, die wir nur dadurch haben, daß wir Augen und Ohren, eine Tastempfindung und so weiter haben, in solchen Bildern bewegt sich das, was der Tote wahrnehmen kann. Denn er hat mit dem Tode alles abgelegt, was nur abstraktes, blasses, intellektualistisches Denken ist. Unsere bildhaften Vorstellungen, insofern wir sie uns angeeignet haben, die nehmen wir durch den Tod mit. Unsere Wissenschaft, unser intellektualistisches Denken, das nehmen wir alles nicht durch den Tod mit. Der Mensch kann ein großer Mathematiker sein, viel geometrische Vorstellungen haben - das alles legt er ebenso ab wie seinen physischen Leib. Der Mensch kann viel wissen über Sternenwelten und die Erdenoberfläche - insofern er dieses Wissen aufgenommen hat in blassen Gedanken, legt er es mit dem Tode ab. Wenn der Mensch als ein gelehrter Botaniker über eine Wiese geht und seine theuretischen Gedanken über die Blumen der Wiese sich durch den Kopf gehen läßt, so ist das ein Gedankeninhalt, der ihn nur hier auf der Erde erfüllt. Allein das, was in seine Augen hereinschlägt und was tingiert wird dadurch, daß er die Blumen liebt, was also dadurch menschlich warm gemacht wird, daß der blasse Gedanke mit dem IchErlebnis zusammengebracht wird, das wird durch des Todes Pforte getragen.

[ 11 ] Es ist wichtig, daß man weiß, was man eigentlich als wirkliches menschliches Besitztum hier auf der Erde so erwirbt, daß man es durch die Pforte des Todes tragen kann. Es ist wichtig, daß man weiß, wie der ganze Intellektualismus, der die Hauptsache der menschlichen Zivilisation seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts ausmacht, etwas ist, was nur im Erdenleben Bedeutung hat, was nicht durch des Todes Pforte getragen wird. So daß man sagen kann: Das Menschengeschlecht lebte die vergangenen Zeiten, die wir besprochen haben, wenn wir nur anfangen bei der atlantischen Katastrophe, die langen Zeiten hindurch durch das alte Indertum, das alte Persertum, durch die ägyptisch-chaldäische Zeit und dann durch unser Zeitalter herauf bis zu uns, die Menschen lebten in dieser ganzen Zeit, also bis zum ersten Drittel oder bis zur Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts noch kein so ausgesprochenes intellektualistisches Leben, wie dasjenige ist, das wir heute als unser Zivilisationsleben so schätzen. — Aber von alldem, was durch die Pforte des Todes mitgetragen wird, erlebten die Menschen vor dem 15. Jahrhundert eben viel mehr. Denn gerade das, auf das sie stolz geworden sind seit dem 15. Jahrhundert, was den ganzen Wert des Erdenlebens eigentlich für die heutige gebildete, sogenannte gebildete Welt ausmacht, das ist etwas, was mit dem Tode ausgelöscht ist. Man könnte geradezu sagen: Was ist das Charakteristische der neueren Zivilisation? Das Charakteristische all dessen, was so gepriesen wird als gebracht durch den Kopernikanismus, durch den Galileismus, es ist etwas, was mit dem Tode abgelegt werden muß, was der Mensch sich eigentlich nur durch das Erdenleben erwerben kann, was aber für ihn auch nur ein Erdenbesitz werden kann. Und indem der Mensch sich heraufentwickelt hat zu der modernen Zivilisation, hat er eigentlich gerade dieses Ziel erreicht, hier zwischen Geburt und Tod zu erleben, was nur für die Erde Bedeutung hat. Es ist sehr wichtig für den modernen Menschen, daß er gründlich wisse, daß der Inhalt dessen, was heute auch gerade im Schulmäßigen als das höchste angesehen wird, nur für das Erdenleben eine eigentliche Bedeutung hat. In unseren gewöhnlichen Schulen unterrichten wir unsere Kinder mit alldem, was moderne Zivilisation ist, zunächst nicht für ihr unsterbliches Seelenteil, sondern wir unterrichten sie nur für ihr irdisches Dasein.

[ 12 ] Der Intellektualismus, er kann auch in folgender Weise von der Seele richtig erfaßt werden. Wenn der Mensch des Morgens aufwacht, da dringen die Sinnesbilder auf ihn ein. Er merkt nur, daß wie ein feines Netz die Gedanken diese Sinnesbilder durchspinnen, und er lebt ja eigentlich in Bildern. Diese Bilder verschwinden sofort, wenn er des Abends einschläft. Auch sein Gedankenleben verschwindet da. Aber der Schein dieser Sinnesbilder, er ist doch wesentlich, denn was sich von ihm das Ich aneignet, das geht mit durch den Tod. Was von innen kommt, der Gedankeninhalt, der bleibt noch in Form einer kurzen Erinnerung, wie Sie wissen, wenige Tage nach dem Tode bestehen, solange der Mensch seinen Ätherleib trägt. Dann löst sich der Ätherleib in den Weiten des Kosmos auf. Das ist ein kurzes Erlebnis für den Menschen unmittelbar nach dem Tode, daß er seine Bilder, die den Sinnenschein enthalten, insofern ihn das Ich sich angeeignet hat, ich möchte sagen, mit starken Linien durchwebt fühlt von dem, was er sich nun durch sein Wissen angeeignet hat. Aber das legt er mit seinem Ätherleib wenige Tage nach seinem Tode ab. Dann lebt er sich mit seinen Bildern in den Kosmos hinein, und dann werden diese Bilder einverwoben in den Kosmos so, wie sie dem eigenen Wesen vor dem Tode einverwoben werden. Vor dem Tode gestalteten sich die Bilder in den Sinneswahrnehmungen nach innen. Sie werden von dem menschlichen Wesen, ich möchte sagen, insofern es durch seine Haut begrenzt ist, ergriffen. Nach dem Tode, nachdem die paar Tage vergangen sind, wo das Gedankenleben noch erlebt wird, weil man den Ätherleib hat, bevor sich dieser auflöst, nach diesen Tagen werden die Bilder in einer gewissen Weise größer. Sie vergrößern sich so, daß sie gewissermaßen nach außen nun so aufgenommen werden, wie sie während des Erdenlebens nach innen aufgenommen wurden. Man könnte schematisch den ganzen Vorgang so zeichnen: Wenn das des Menschen Leibesgrenze ist (siehe Zeichnung, hell) und er im Wachzustande seine Eindrücke hat, dann bilden sich seine Innenerlebnisse von den Sinneseindrücken innerhalb seines Wesens. Nach dem Tode erlebt der Mensch seine Grenze wie ein umfassendes Gefühl; aber die Eindrücke, die wandern gewissermaßen aus ihm heraus. Er empfindet sie in seiner Umgebung (rot). So daß sich der Mensch, während er im Erdenleben sagt: Meine Seelenerlebnisse sind in mir -, sich nach dem Tode sagt: Meine Seelenerlebnisse sind vor mir, oder besser gesagt, um mich. - Sie verschmelzen mit der Umwelt. Sie werden dadurch auch innerlich anders. Sagen wir zum Beispiel, der Mensch habe sich, weil er ein Blumenliebhaber ist, besonders stark eingeprägt in immer wiederholten Sinneseindrücken eine Rose, eine rote Rose; dann wird er, wenn er nun nach dem Tode erlebt dieses Hinauswandern, die Rose größer sehen, bildhaft größer, aber sie wird ihm grünlich erscheinen. Also auch innerlich ändert sich das Bild. Alles das, was der Mensch in der grünen Natur wahrgenommen hat, insofern er wirklich mit menschlichem Anteil diese grüne Natur erlebt, nicht bloß mit abstrakten Gedanken, wird nun nach dem Tode für ihn zu einer rötlich sanften Umgebung seines ganzen Wesens. Aber es wandert das Innere nach außen: Der Mensch hat sozusagen das, was er sein Innen nennt, nach dem Tode in seiner Umgebung, außen.

[ 13 ] Diese Erkenntnisse, die also dem menschlichen Wesen angehören, insofern dieses wiederum der Welt selbst angehört, diese Erkenntnisse, wir können sie uns durch Geisteswissenschaft aneignen. Denn nur dadurch, daß wir uns diese Erkenntnisse aneignen, bekommen wir eine Vorstellung von dem, was wir eigentlich selber sind. Wir können nicht eine Vorstellung von dem bekommen, was wir eigentlich selber sind, wenn wir uns nur in dem Sinne kennen, wie der Mensch ist zwischen Geburt und Tod und in seiner Gedankenwebung von innen. Denn das sind die Dinge, die als solche nach dem Tode abfallen. Von dem Sinnenschein bleibt nur das, was ich Ihnen eben geschildert habe, und es bleibt so, wie ich es Ihnen geschildert habe.

[ 14 ] Es ist in der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts, wo die materialistische Empfindungsweise und Weltanschauung der zivilisierten Menschheit, wie ich öfter betont habe, eine Kulmination erlangt hatte, einen Höhepunkt, es ist da viel davon die Rede gewesen, wie der Mensch, wenn er sich eine Religion begründet, wenn er von irgend etwas GöttlichGeistigem in der äußeren Welt spricht, eigentlich nur sein Inneres nach außen projiziere. Sie brauchen nur einen solchen grundmaterialistischen Schriftsteller wie den Feuerbach zu lesen, der auch auf Richard Wagner einen großen Einfluß gehabt hat, so werden Sie sehen, wie dieses materialistische Denken eigentlich draußen nur die Natur sieht, das heißt aber nur den Schein, in derjenigen Gestalt, wie er sich darstellt zwischen Geburt und Tod, und wie dann diese materialistische Gesinnung glaubt, alles Denken über das Göttlich-Geistige sei doch nur das Innere des Menschen, hinausgeworfen, hinausprojiziert, so daß der Mensch das Göttlich-Geistige nur dadurch glaubt annehmen zu dürfen, weil er sein eigenes Inneres nach außen projiziert. Man nannte diese scheinbare Erkenntnis den Anthropomorphismus. Man sagte: Der Mensch ist anthropomorphistisch; er stellt sich die Welt nach dem vor, was in seinem eigenen Inneren liegt. Und es wurde ja um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts bei den eigentlich charakteristischen Materialisten ein Satz geprägt, welcher darstellen sollte, wie so herrlich weit die Welt der Menschen es gebracht hätte, gerade in der neueren Zeit. Man sagte: Die Alten glaubten, Gott habe die Welt geschaffen; wir Neueren aber wissen: Der Mensch hat Gott geschaffen, das heißt, er strahlt ihn von seinem eigenen Wesen nach außen hinaus. — Das war aus dem Grunde, weil man eben nur von dem Inneren wußte, das zwischen Geburt und Tod eine Bedeutung hat. Und es war in Wirklichkeit nicht bloß eine falsche Ansicht, die man sich da gebildet hat, sondern man hatte sich eine Weltanschauung gebildet, die in der Tat anthropomorphistisch war: Man hatte von dem Göttlich-Geistigen keine anderen Vorstellungen als diejenigen, die der Mensch schließlich aus sich hinausgeworfen, hinausprojiziert hatte.

[ 15 ] Aber vergleichen Sie damit alles das, was zum Beispiel von mir in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» dargestellt worden ist; da werden Sie sehen, daß die Welt nicht so dargestellt wird, wie die menschlichen Vorstellungen im Inneren sind. Was ich da darstelle als Saturn-, Sonne-, Mond-, Erdenentwickelung — der Mensch trägt es nicht in sich. Man muß erst vorausnehmen, was der Mensch nach dem Tode erlebt, was er also vor sich hinstellen kann. Da ist nichts Anthropomorphisches. Diese «Geheimwissenschaft» ist dargestellt kosmomorphistisch, das heißt, es sind die Eindrücke so, daß sie tatsächlich erlebt werden als außerhalb des Menschen stehend. Daher verstehen diese Dinge diejenigen Menschen nicht, die vorstellungsgemäß nur erleben können, was innerhalb des Menschen liegt, wie das ja so geworden ist gerade im intellektualistischen Zeitalter seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts. Dieses Zeitalter, das nimmt ja nur wahr, was eben im Inneren des Menschen lebt, und projiziert es nach außen. Niemals wird man eine Außenwelt so schildern können, wie ich sie in dem Kapitel meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» schildere, wo von der Saturnentwickelung die Rede ist, auch nur in der allereinfachsten elementarsten Erscheinung, wenn man nur das, was im menschlichen Inneren lebt, nach außen projiziert.

[ 16 ] Sehen Sie, der Mensch lebt zum Beispiel in Wärme. Wie er durch seinen Gesichtssinn die Welt in Farben wahrnimmt, so nimmt er die Welt in Wärme wahr durch seinen Wärmesinn. Er erlebt die Wärme in seinem, ich möchte sagen, Innenmenschenwesen, insofern es durch die Haut begrenzt ist. Aber er abstrahiert dabei schon in der Wahrnehmung. Wärme im Weltenleben wahrgenommen, kann eigentlich nicht anders dargestellt werden, als indem man sie in ihrer Totalität erfaßt. Dann ist aber bei Wärme immer etwas dabei, was in der menschlichen Erfahrung nur ausgedrückt werden kann, indem man auf den Geruchssinn hinweist. Wärme, objektiv draußen wahrgenommen, hat immer auch etwas von Geruch an sich.

[ 17 ] Und jetzt lesen Sie das Kapitel in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» über denjenigen Vorgang unserer Erde, der hauptsächlich in Wärme lebt: wie da zugleich von den Geruchsempfindungen die Rede ist, indem man diese Dinge schildert. Sie sehen daraus, es ist die Wärme nicht so geschildert, wie der Mensch sie im Intellektualismus erlebt. Es ist herausgestellt aus dem Menschen. Und das, was der Mensch hier zwischen Geburt und Tod als Wärme erlebt, das ist eben sogleich nach dem Tode wie eine Geruchsempfindung da.

[ 18 ] Licht erlebt der Mensch hier auf der Erde eigentlich sehr abstrakt. Er erlebt dieses Licht, indem er sich einer fortwährenden Täuschung hingibt. Ich möchte darauf auch hier hinweisen: Ich habe - es ist jetzt, ich darf wohl sagen, achtunddreißig Jahre her - eine Abhandlung geschrieben, sehr grün, jugendlich, in der ich darzustellen versuchte, wie die Leute vom Lichte reden. Aber wo ist denn das Licht? Der Mensch nimmt Farben wahr; die sind seine Sinneseindrücke. Wo er immer hinschaut: Farben, irgendeine Tingierung nimmt er wahr, auch wenn er weiß, es ist eine Tingierung. Aber Licht — er lebt im Licht, aber er nimmt das Licht doch nicht wahr; er nimmt durch das Licht Farben wahr, aber das Licht selbst nimmt er doch nicht wahr. In welchen Illusionen der Mensch in dieser Beziehung im intellektualistischen Zeitalter lebt, das geht daraus hervor, daß es eine «Lichtlehre» in unserer Physik gibt; daß man so redet, als wenn das irgend etwas wäre, was Hand und Fuß hat, wenn man es als Lichtlehre betrachtet. Es hat nicht Hand und Fuß. Nur eine Farbenlehre hat Hand und Fuß, aber nicht eine Lichtlehre.

[ 19 ] Es brauchte schon des ganz gesunden Natursinns Goethes, damit nicht eine Optik zustande kam, sondern eine Farbenlehre. Wir schlagen heute unsere Physikbücher auf — da wird das Licht geradezu konstruiert: Strahlen werden da gezogen; die reflektieren sich und tun alles mögliche. Aber es ist ja alles keine Realität! Farben sieht man. Von einer Farbenlehre kann man sprechen, aber nicht von einer Lichtlehre. Man lebt im Lichte. Durch das Licht und am Licht nimmt man Farben wahr, aber nichts vom Lichte. Das Licht kann niemand sehen. Denken Sie sich, Sie wären in einem Raume, der ganz durchleuchtet wäre, aber kein einziger Gegenstand wäre drinnen. Sie könnten ebensogut im Dunkeln sein. Sie würden in einem Raum, wenn er ganz dunkel ist, nicht mehr für sich wahrnehmen als im bloßen Lichte; Sie könnten ihn nicht einmal unterscheiden von einem ganz dunklen Raum. Sie könnten ihn nur durch ein inneres Erlebnis unterscheiden. Aber sobald der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes geschritten ist, nimmt er geradeso, wie er an der Wärme den Geruch wahrnimmt, an dem Lichte etwas wahr, wofür wir heute in unserer intellektualistischen Sprache nicht einmal ein passendes Wort haben — wir müßten sagen: Rauch. Ein Hinfluten, das nimmt er wirklich wahr. Das Hebräische hatte noch so etwas: Ruach. Das Hinflutende wird wahrgenommen. Dasjenige, was wir eigentlich allein berechtigt sind, Luft zu nennen, das wird da wahrgenommen.

[ 20 ] Und wenn wir nun auf dasjenige sehen, was überall in unseren Erdenverhältnissen wirkt als chemische Wirkungen: Wir nehmen sie wahr in ihren Erscheinungen, diese chemischen Wirkungen, die chemischen Ätherwirkungen. Geistig gesehen, ohne den physischen Leib, also auch nach dem Tode, liefern sie das, was der Inhalt des Wassers ist.

[ 21 ] Und das Leben selber, es ist das, was der Inhalt der Erde ist, des Festen. Unsere gesamte Erde wird von dem Gesichtspunkte des toten Menschen aus als ein großes Lebewesen wahrgenommen. Wenn wir hier auf der Erde herumwandeln, nehmen wir ihre einzelnen Wesenheiten, insofern sie Erdenwesenheiten sind, auch als Totes wahr. Aber worauf beruht denn das, daß wir Totes wahrnehmen? Die ganze Erde lebt, und sie enthüllt sich uns auch in ihrem Leben sofort, wenn wir sie von jenseits des Todes aus erblicken. Wenn das unsere Erde ist (es wird gezeichnet), so sehen wir von ihr ja immer nur ein ganz kleines Stück und sind angepaßt an das Sehen dieses kleinen Stückes, nur wenn wir sie im Geiste umschweben und außerdem ein Wahrnehmungsvermögen von außen haben, die Eindrücke also vergrößert werden, dann nehmen wir sie als ganzes Wesen wahr. Dann aber ist sie ein Lebewesen. - Damit habe ich auf etwas hingedeutet, was außerordentlich wichtig ist, einmal ins Auge zu fassen. (Es wird an die Tafel geschrieben.)

Wärme Geruch

Licht Rauch, Luft

Chemische Wirkungen Wasser

Leben Erde

[ 22 ] Sehen Sie, ich hatte einmal mit einem Herrn ein Gespräch, der sagte, man wisse jetzt endlich durch die Relativitätstheorie, daß man sich den Menschen auch doppelt so groß vorstellen könne als er ist; das alles sei relativ, das alles hänge ja nur vom menschlichen Anschauen ab.

[ 23 ] Das ist eine ganz unwirklichkeitsgemäße Anschauung. Denn sehen Sie, wenn - es ist schon sogar ein nicht ganz eigentliches Bild, aber sagen wir — ein Sonnenkäferchen auf dem Menschen herumkriecht, so ist es im Verhältnis zum Menschen in einer gewissen Größe. Es nimmt nicht die ganze menschliche Wesenheit wahr, sondern seiner Größe gemäß immer nur wenig vom Menschen. Und deshalb ist für das Sonnenkäferchen der Mensch kein Lebendes, sondern der Mensch, auf dem es herumkriecht, ist für das Sonnenkäferchen geradeso tot, wie für den Menschen die Erde tot ist. Sie müssen den Gedanken aber auch umgekehrt denken können. Sie müssen sich sagen können: Damit der Mensch die Erde als tot erleben kann, muß er eine bestimmte Größe haben auf der Erde. Die Größe des Menschen ist nicht eine zufällige im Verhältnis zur Erde, sondern sie ist völlig angemessen dem ganzen Leben des Menschen auf der Erde. Daher kann man sich den Menschen nicht — etwa im Sinne der Relativitätstheorie — groß oder klein denken. Nur wenn man ganz abstrakt, wenn man ganz intellektualistisch denkt und vorstellt, dann kann man ihn groß und klein denken; nur dann kann man sagen: Wäre man etwas anders organisiert, so würde der Mensch vielleicht doppelt so groß erscheinen, und dergleichen.

[ 24 ] Das hört auf, wenn man eine Vorstellung in sich aufnimmt, die absieht von dem Subjektiven, und die des Menschen Größe im Verhältnis zur Erde ins Auge fassen kann. Es ist eben auch so, daß das ganze menschliche Wesen nach dem Tode ins Weltenall hinaus sich erweitert, daß der Mensch eine Zeitlang nach dem Tode viel größer wird als die Erde selbst. Dann empfindet er sie als ein lebendes Wesen. Und dann empfindet er in alledem, was Wasser ist, chemische Wirkungen. Er empfindet in dem Luftartigen das Licht, nicht abgesondert Luft und Licht, sondern in dem Luftartigen das Licht und so weiter. Bilder erlebt der Mensch, veränderte Bilder gegenüber den Bildern seines Wachlebens zwischen Geburt und Tod.

[ 25 ] Ich sagte: Nichts können wir durch den Tod mit uns nehmen von dem, was auf intellektualistische Art von unserer Seele erworben ist, nichts davon. Aber vor dem 15. Jahrhundert, da hatte der Mensch noch eine Art Erbschaft aus Urzeiten. Sie wissen ja, diese Erbschaft war so groß in Urzeiten, daß der Mensch ein atavistisches Hellsehen hatte, das dann abgestumpft und abgeblaßt, abgelähmt wurde, das vollends in die Abstraktion überging seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts. Aber das, was der Mensch von dieser göttlichen Erbschaft mit durch den Tod nahm, das gab ihm eigentlich sein Wesen. So wie der Mensch hier physische Materie aufnimmt, wenn er durch die Geburt respektive durch die Empfängnis ins irdische Dasein tritt, so war es das göttliche Wesen, das er mitbrachte und durch den Tod trug, das ihm überhaupt, wenn ich sosagen darf, der Ausdruck ist grotesk, aber er wird es Ihnen verständlich machen, eine geistige Schwere - es ist natürlich polarisch entgegengesetzt der physischen Schwere -, das ihm eine geistige Schwere gab.

[ 26 ] So wie die Menschen jetzt inkarniert werden, haben sie dieses Erbe eigentlich, wenn sie richtige Zivilisationsmenschen sind, nicht mehr an sich. Höchstens da und dort kann man es noch bemerken: die nichtrichtigen Zivilisationsmenschen, die immer seltener werden, haben das noch in sich. Und es ist durchaus eine ernste Angelegenheit der Menschheitsentwickelung, daß der Mensch durch das, was er durch die intellektualistische Zivilisation erhält, sein Wesen im Grunde verliert. Und er geht der Gefahr entgegen, daß er nach dem Tode zwar so hinauswächst, daß er diese Eindrücke hat, aber daß er sein eigentliches Wesen, das Ich, verliert, wie ich das schon gestern von einem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus dargestellt habe. Und es gibt für dieses Wesen, für den neueren und zukünftigen Menschen nur eine Rettung, und die ist durch das Folgende zu erkennen: Wir können, wenn wir hier in der Sinneswelt eine Realität erfassen wollen, die das Denken so stark macht, daß es nicht bloß blasses Bild ist, sondern daß es innere Lebendigkeit hat - wir können am Menschen eine solche von innen heraus kommende Realität nur in jenem reinen Denken erkennen, das ich in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» als dem Handeln zugrunde liegend geschildert habe. Sonst haben wir in allem menschlichen Bewußtsein nur Sinnenschein. Wenn wir aber aus reinem Denken heraus, das heißt, wie ich es in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» dargestellt habe, frei handeln, wenn wir also wirklich die Impulse unseres Handelns im reinen Denken haben, so geben wir diesem sonst Scheindenken, diesem intellektualistischen Denken dadurch, daß es zugrunde liegt unseren Handlungen, eine Realität. Und das ist die einzige Realität, die wir rein von innen heraus in den Sinnenschein hereinverweben können und mit durch den Tod nehmen können.

[ 27 ] Was also nehmen wir da eigentlich mit durch den Tod? Das, was wir in wirklicher Freiheit hier zwischen Geburt und Tod erlebt haben. Diejenigen Handlungen, die entsprechen der Schilderung der Freiheit in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit», begründen, was der Mensch außer dem Sinnenschein, der sich in der Weise, wie ich es geschildert habe, umwandelt, durch den Tod hindurchtragen kann. Dadurch bekommt er wieder ein Wesen. Dadurch, daß sich der Mensch frei macht von der Determination in der sinnlichen Welt, dadurch bekommt er nach dem Tode wieder ein Wesen, dadurch ist er ein reales Wesen. Die Freiheit ist es, was, wenn wir dieses Wesen erwerben, uns gerade für die Zukunft als Menschenseelen bewahrt vor dem seelisch-geistigen Tode.

[ 28 ] Diejenigen Menschen, die sich nur ihren Naturgewalten, das heißt, den Instinkten und Trieben - ich habe das vom rein philosophischen Standpunkt in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» geschildert — überlassen, die leben in etwas, was mit dem Tode verfällt. Sie leben sich dann in die geistige Welt hinein. Selbstverständlich, ihre Bilder sind da. Aber sie würden allmählich in Anspruch genommen werden müssen von anderen geistigen Wesenheiten, wenn der Mensch sich nicht im vollen Sinne der Freiheit entwickelte, damit er wiederum ein Wesen bekomme, wie er es gehabt hat, als er sein göttlich-geistiges Erbe noch hatte.

[ 29 ] So innerlich hängt das intellektualistische Zeitalter mit der Freiheit zusammen. Deshalb konnte von mir immer gesagt werden: Der Mensch mußte intellektualistisch werden, damit er frei werden könne. Der Mensch verliert im Intellektualismus sein geistiges Wesen, denn er kann vom Intellektualismus nichts durch des Todes Pforte tragen. Aber er erwirbt hier die Freiheit durch den Intellektualismus, und was er so in Freiheit erwirbt, das kann er dann durch des Todes Pforte tragen.

[ 30 ] Der Mensch mag also denken so viel er will auf bloße intellektualistische Art — nichts davon geht durch des Todes Pforte. Allein wenn der Mensch das Denken verwendet, um es in freien Handlungen auszuleben, so geht so viel gewissermaßen als die geistig-seelische Substanz, die ihn zum Wesen macht und nicht zum bloßen Wissen, mit ihm aus seinen Freiheitserlebnissen durch des Todes Pforte. Im Denken wird uns durch den Intellektualismus unser Menschenwesen genommen, um uns zur Freiheit gelangen zu lassen. Was wir in Freiheit erleben, das wird uns dann wiederum gegeben als menschliches Wesen. Der Intellektualismus tötet uns, aber er belebt uns auch. Er läßt uns wieder auferstehen mit völlig verwandelter Wesenheit, indem er uns zu freien Menschen macht.

[ 31 ] Ich habe das heute zunächst so dargestellt, wie es sich aus dem Menschenwesen selbst ergibt. Morgen will ich dann, was ich heute nur aus dem Menschenwesen dargestellt habe, in Zusammenhang bringen mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha, mit dem Christus-Erlebnis, um zu zeigen, wie sich in Tod und Auferstehung nun das Christus-Erlebnis als innerliches Erlebnis beim Menschen hineinergießen kann. Davon also morgen weiter.

Tenth Lecture

[ 1 ] I would like to look back once more at our last considerations. We have tried to form ideas about how human mental life, human soul life, and human physical life can be understood. When we consider human soul life, that is, what human beings feel as going on within themselves as thinking, feeling, and willing, we find that thinking, that is, what is directly experienced as the content of thoughts, takes place between the physical body and the etheric body, that feeling then takes place between the etheric body and the astral body, and willing between the astral body and the I. We see from this that thoughts, insofar as we are fully conscious of them, only represent what looks up from the depths of our own being and can actually only give form to the waves of soul life. Something like shadows rise up from the depths of the human being, fill our consciousness, and then become the content of our thoughts.

[ 2 ] If we wanted to represent this schematically, we could say: physical body (see drawing, blue), etheric body (orange), astral body (yellow) and I (purple). Then we would have the content of our thoughts between the physical body and the etheric body. — But you have seen from my descriptions in the last lectures that this content of thoughts is, in its truth, something much more real than what we experience in our consciousness. What we experience in consciousness is only something that, as I said, rises up from the depths of our being in waves to the I. There it rises up. The content of feeling lies between the etheric body and the astral body and rises up again to the I, and the content of the will lies between the astral body and the I. It is therefore closest to the I. We can say that in the will, the I experiences itself in its most immediate form, while the content of feelings and thoughts rests in the depths of our being and only the waves surge up into our I.

[ 3 ] But we also know that the will, the content of the will as we experience it, is experienced in a dull way. We know no more about the will as it lives, say, in a movement of the arm or a movement of the leg, than we know about what happens between falling asleep and waking up. The will lives dully within us. Nevertheless, it is what lives in our actual self as the closest thing to it. Consciously, or let us say, while awake, we perceive the will only through the shadows of thoughts that rise from the depths of our being. The ideas that we consciously experience are shadow images of a deep spiritual weaving; but they are only shadow images, while we experience the will directly, but dimly. However, we can only have an alert awareness of the will through the shadowy thought images.

[ 4 ] This is how things appear to us when we consider our human nature and look into the depths of our inner being. We see, I would say, how little of ourselves we contain in our consciousness, how little rises up from the inner depths of our being into our consciousness. We understand, in a sense, very little of what we are inwardly as the I, and actually perceive only the tinge that the content of our thoughts casts upon this dull, volitional I.

[ 5 ] With ordinary consciousness, we can hardly see anything more than what is immediately real, than what we perceive as our dull ego shortly before waking up or shortly after falling asleep. But when you wake up, the world of sensory perceptions bursts into this dull ego. Just become aware of how dull your life is between falling asleep and waking up, so that you almost perceive the dullness as emptiness. And only when you wake up, when you open your senses to the outside world and sensory impressions come in, are you able, guided by these sensory impressions, to truly perceive yourself as an I. Then the appearance of sensory perceptions strikes the I. Then that dull being of which I have just spoken is filled with the appearance of sensory perceptions. So that the I, as fully conscious in the earthly human being, actually lives only in that state in which, through the sense images, through everything that enters his senses, and then it emerges from within as the brightest thing, as that which illuminates the most, the shadowed content of thought.

[ 6 ] One can therefore say: Sensory perceptions penetrate from outside. The content of the will is only dimly perceived. The content of the feelings rises up and connects with the sensory impressions. We see red, it fills us with a certain feeling; we see blue, we hear C sharp or C and feel something. But then we also form ideas about what the sensory impressions are. The content of our thoughts, which comes from within, interweaves with the sensory impressions. The inner connects with the outer. But the fact that we live in a fully awake ego is actually due to sensory appearances, and our ego contributes to this as much as has just been described in terms of what encounters the outer world.

[ 7 ] Let us pay close attention to this sense appearance. Let us look at it and be clear about it: it is entirely dependent on our physical existence. It can only fulfill us if we confront the external world with our physical body in the waking state. This sense appearance ceases at the moment when, passing through death, we lay down our physical body in the sense we have discussed in the preceding considerations.

[ 8 ] Between birth and death, our I is thus awakened, as it were, by the sense appearance. We can only have as much of our actual being as awake earthly human beings as is enlivened by this sense light. Now vividly imagine how the human I-being catches the sense light, which is only an illusion, and weaves it into its own human being. Now consider how something external becomes internal, how — as you can see in dreams — I would say a very fine fabric is spun internally, into which the sensory impressions are woven. The ego takes possession of what comes through the sensory impressions. The external becomes internal. But only what becomes internal can the human being carry through the gate of death.

[ 9 ] So it is a fine fabric that the human being carries through the gate of death. He lays down his physical body. It conveyed sensory impressions to him. Therefore, sensory impressions are only illusions, because the physical body is discarded. Only as much as the I has absorbed from the illusion is carried through the gate of death. The etheric body is also discarded shortly after death. But with that, what is between the physical body and the etheric body is discarded from one's own being. As we have seen, this dissolves into the general cosmos, forming only the seed for further worlds, but does not actually continue to live with our human being after death. Only that which has risen up in waves and connected itself with the sensory appearance continues to live. If one considers this, one can get a rough idea of what the human being carries through the gate of death.

[ 10 ] For this reason, when asked, “How can someone build a bridge to a departed human being?”, one must say the following: This bridge cannot be built by sending abstract thoughts or vague ideas to the deceased. If you think of the deceased with abstract ideas, what happens? Abstract ideas have almost nothing left of their sensory appearance; they have faded, but there is nothing truly alive in them, only that which rises up from the inner reality. Only a tinge of human nature lives in abstract ideas. So what we perceive through our intellect is much less real than what fills our ego in the sense appearance. What fills our ego in the sense appearance makes our ego awake. But this awake content is only permeated by the waves that surge up from our own inner being. So when we direct abstract, faded thoughts to a dead person, they cannot have communion with us; but they can when we imagine ourselves quite concretely, as if we were standing there with them, talking to them, hearing what they wanted from us through their own words. The content of our thoughts, the pale content of our thoughts, will not bear much fruit, but it will if we develop a subtle sensitivity to the sound of his voice, to the particular emotion or temperament with which he conversed with us, if we feel the warm, living togetherness with his wishes, in short, if we imagine this concrete reality, but in such a way that our imaginations are pictures: when we see ourselves standing or sitting together with him, how we experienced the world with him. It would be easy to believe that it is just pale thoughts that play across death. That is not the case. Vivid images play across death. And in images of sensory appearance, in images that we have only because we have eyes and ears, a sense of touch, and so on, in such images moves what the dead can perceive. For with death, he has laid down everything that is merely abstract, pale, intellectual thinking. Our pictorial ideas, insofar as we have acquired them, we take with us through death. Our science, our intellectual thinking, we do not take any of that with us through death. A person can be a great mathematician, have many geometric ideas—he lays all that down just as he lays down his physical body. A person can know a great deal about the worlds of the stars and the surface of the earth—insofar as they have absorbed this knowledge in pale thoughts, they lay it down with death. When a learned botanist walks across a meadow and lets his theoretical thoughts about the flowers in the meadow pass through his mind, this is a thought content that fills him only here on earth. Only that which strikes his eyes and is colored by his love for the flowers, that which is made humanly warm by the pale thought being brought together with the I-experience, is carried through the gate of death.

[ 11 ] It is important to know what it is that we actually acquire here on earth as real human possessions, which we can carry through the gate of death. It is important to know that all the intellectualism that has been the mainstay of human civilization since the middle of the 15th century is something that has meaning only in earthly life and cannot be carried through the gate of death. So that we can say: The human race lived through the past ages we have discussed, if we begin with the Atlantean catastrophe, through the long ages of ancient India, ancient Persia, through the Egyptian-Chaldean period, and then through our own age up to the present, human beings lived during this entire period, that is, until the first third or until the middle of the 15th century, did not have such a pronounced intellectual life as the one we value so highly today as our civilized life. But of all that is carried through the gate of death, people before the 15th century experienced much more. For precisely that which they have become proud of since the 15th century, which actually constitutes the whole value of earthly life for today's educated, so-called educated world, is something that has been wiped out with death. One could even say: What is the characteristic feature of the newer civilization? The characteristic feature of everything that is so highly praised as having been brought about by Copernicanism and Galileanism is something that must be discarded with death, something that human beings can only acquire through earthly life, but which can only become an earthly possession for them. And in developing himself up to modern civilization, man has actually achieved precisely this goal, to experience here between birth and death what has meaning only for the earth. It is very important for modern man to know thoroughly that the content of what is regarded today, especially in schools, as the highest has real meaning only for earthly life. In our ordinary schools, we teach our children everything that modern civilization is, not primarily for their immortal soul, but only for their earthly existence.