Cosmosophy I

GA 207

16 October 1921, Dornach

Lecture XI

Our last explorations have shown us the fundamental difference between man's whole view here, between birth and death, and in the spiritual world, between death and a new birth. We explained yesterday that in our present era, since the middle of the fifteenth century, man may gain freedom between birth and death; everything on earth that he fulfills out of the impulse of freedom gives his being in the life between death and a new birth weight, as it were, reality, existence. When we emancipate ourselves from the necessities of earthly existence, when we ascend to the point where our will is guided by free motives—that is, when our will is not founded on anything in earthly life—then we create the possibility of being an independent being also between death and a new birth. In our age this capacity to preserve our own independent existence after death is connected with something we may call the relationship to the Mystery of Golgotha. This Mystery of Golgotha may be studied from the most varied viewpoints. In the course of the past years, we have already studied a great number of these viewpoints; today we shall view the Mystery of Golgotha from the standpoint arising out of the study of the value of freedom for the human being.

Here on earth, between birth and death, the human being really does not have any view of himself in his ordinary consciousness. He cannot look into himself. It is an illusion, of course, to believe, as outer science does, that it is possible to obtain an inner knowledge of the human organization by studying what is dead in the human being, indeed sometimes by studying only the corpse. This is altogether an illusion, a deception. Here, between birth and death, the human being has only a view of the outer world. What kind of view is this, however? It is one that we have frequently called the view of “appearance” (Schein) and yesterday I again emphasized this strongly.

When our senses are directed toward our surroundings between birth and death, the world appears to us as appearance, as semblance. We can take this appearance into our I—being. We can, for example, preserve it in our memory, making it therefore in a certain sense our own. Insofar as it stands in front of us when we look out into the world, however, it is an appearance that manifests itself particularly—as I already explained to you yesterday—by disappearing with death and reappearing in another form; that is, it is no longer experienced in us but is experienced in front of or around us.

If, however, in the present age the human being between birth and death were not to perceive the world as appearance, if he could not perceive the appearance, he could not be free. The development of freedom is possible only in the world of appearance. I have mentioned this in my book, The Riddle of Man (vom Menschenratsel), pointing out that in reality the world that we experience may be compared with the images that look out at us from a mirror. These pictures that look out at us from a mirror cannot force us to do anything, for they are only pictures, they are appearance. Similarly man's world of perception is also appearance. The human being is not completely woven into the appearance of the world. He is woven into a world of appearance only with his perceiving, which fills his waking consciousness. If man views his impulses, instincts, passions, and temperament, and everything that surges up from the human being, without being able to bring them into clear mental images, at least into waking mental images, then all this is not appearance; it is reality, but a reality that does not rise up in man's present consciousness.

Between birth and death, the human being lives in a true world that he does not know, one that cannot ever really give him freedom. It may implant in him instincts that make him unfree; it may call forth inner necessities, but it can never enable the human being to experience freedom. Freedom can be experienced only within a world of pictures, of appearance. When we awaken we must enter a perceptive life of appearance, so that freedom can develop.

This life of appearance, which constitutes our waking life of perception, did not always exist in this way within humanity's historical evolution. If we go back into ancient times, to which we have so often looked back in our lectures, to times when there still existed a certain instinctive vision, or remnants of this instinctive vision (which lasted until the middle of the fifteenth century), we cannot say in the same sense that the human being in his waking condition was surrounded only by a world of appearance. Everything that the human being saw in his own way as the world's spiritual background spoke through the appearance. He also saw this appearance, but in a different way. For him this appearance was an expression, a manifestation, of a spiritual world. This spiritual world then vanished behind the appearance, and only the appearance remained. The essential thing in the progressive development of humanity is that in more ancient times the appearance was experienced as the manifestation of a divine-spiritual world, but the divine-spiritual vanished from this appearance, so that before man's eyes lies only appearance, in order that he might discover his freedom within this world of appearance. The human being therefore must find his freedom in a world of appearance; he does not find freedom in the true world, which completely withdrew to the dull experiences of his inner being; there, he can find only a necessity. We may therefore say that man's world of perception between birth and death—everything that I say applies only to our age—is a world of appearance. Man perceives the world, but he perceives it as appearance.

How, then, do matters stand between death and a new birth? In our last studies we suggested that after death the human being does not perceive this outer world that he sees here, between birth and death, but between death and a new birth man essentially perceives the human being himself, the inner being of man. The human being is then the world for man. What is concealed here on earth becomes manifest in the spiritual world. Between death and a new birth, man gains insight into the entire connection between the soul life and the organic life of the human being, between the activity of the single organs, and in short, everything that, symbolically speaking, lies enclosed within the human skin.

We find, however, that in the present age it is again the case that the human being cannot live in appearance after death. The life in appearance is actually valid for him only between birth and death. The human being has come to the point today that between death and a new birth he cannot live in appearance. When he passes through death, he is imprisoned, as it were, by necessity. The human being feels that he is free in his perceiving here on earth, where he may turn his eyes where he wishes; he may combine what he perceives into concepts so as to experience his freedom of action in these concepts; between death and a new birth, however, he feels unfree regarding the world of perceptions. He is overpowered, as it were, by the world. It is just as if the human being perceived in the same way as he would perceive here on earth if he were to be hypnotized by every single sense perception, if he were to be overpowered by every single sense perception so that he would be unable to liberate himself from them out of free will.

This has been the course of man's development since the middle of the fifteenth century. The divine-spiritual worlds vanished from the appearance of the earth, but between death and a new birth, these divine spiritual worlds imprison him, so that he cannot maintain his independence. I said that only if the human being really develops freedom on earth, that is, if he takes an interest with his entire being in the appearance in life, is it possible for him to carry his own being through the portal of death.

We can see what is necessary in order to develop freedom also by looking into yet another difference between the way of viewing things today and more ancient human views.

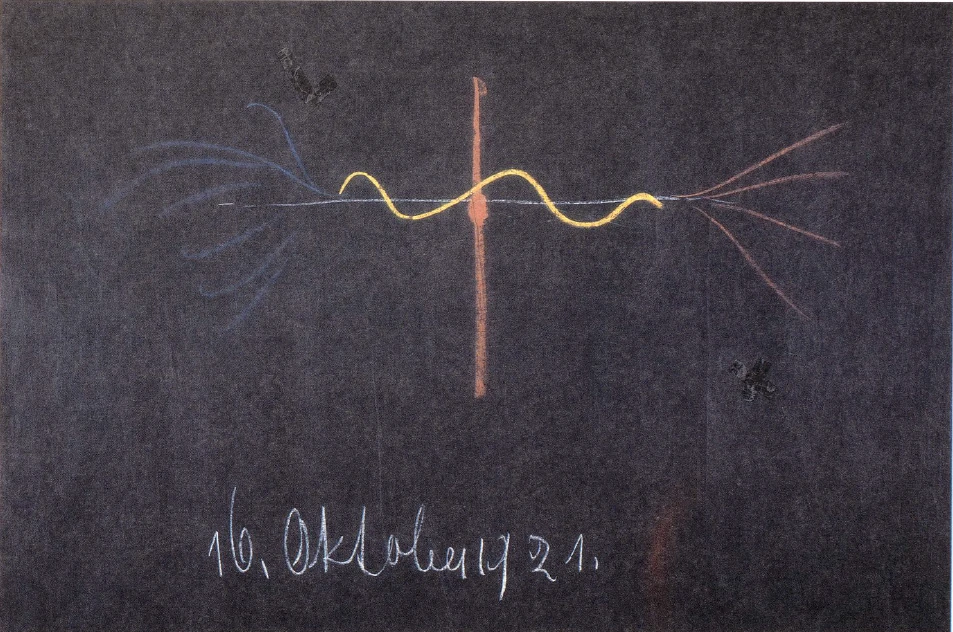

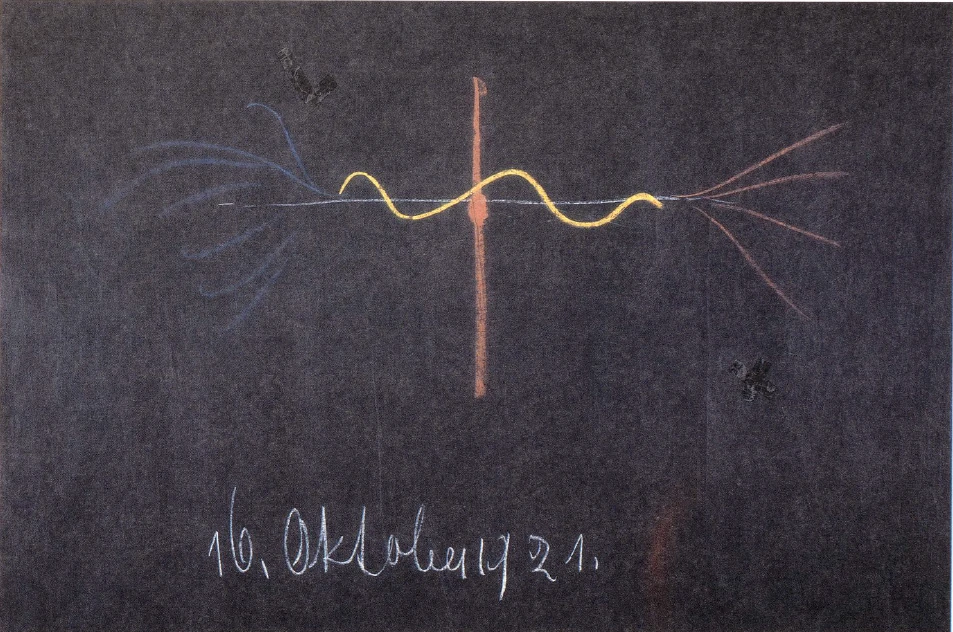

Whether we consider humanity in general or the initiates and the mysteries in ancient times, we find that the whole view of the world had another orientation from that of today. If the human being remains standing by what he has acquired since the middle of the fifteenth century, through the kind of cognition that has arisen since that time, one finds that the human being had mental images of the evolution of the earth, of the evolution of the human race; he lost track, however, of the mental images that might have given him satisfactory indications concerning the beginning and end of the earth. We might say that the human being was able to survey a certain line of evolution; he looked back historically, he looked back geologically. When he went back still further, however, he began to construct hypotheses. He imagined that the beginning of the world was a primordial mist, which appeared to be a physical formation. Out of it evolved—that is to say, not really, but people imagined that this was so—the higher beings of the realms of nature, plants, animals, and so on. In accordance with conceptions of modern physics, people thought that earthly existence disintegrates in the end (see drawing below) by heat—again a hypothesis. Man thus saw only a segment, as it were, between the beginning and end of the earth. Beginning and end became a hazy, unsatisfactory picture to present-day human beings.

This was not the case in more ancient times. In ancient times people had very precise notions of the beginning and end of the earth, because they still saw the self-revelation of the divine-spiritual in the appearance. We can call to mind the Old Testament, for example, or other religious teachings of the past. In the Old Testament we find conceptions that are connected with the beginning of the world, and they are described in a form accessible to the human being, enabling him to grasp his own existence upon the earth. The Kant-Laplace nebula or primordial mist does not enable anyone to grasp human life on earth.

If you take the wonderful cosmogonies of the various pagan peoples, you will again find something that enabled man to grasp his earthly existence. The human being thus directed his gaze toward the beginning of the earth and came to conceptions that encompassed man. Conceptions of the end of the earth remained for a longer time in human consciousness. In Michelangelo's “Last Judgment,” for example, and other “Last Judgments,” we come across conceptions about the end of the earth, which were handed down as far as our own era and which encompass the human being; and although the ideas of sin and atonement are difficult, these conceptions do not do away with the human being.

Take the modern hypothetical conception of the end of the earth, that everything will end in a uniform heat. The entire human essence dissolves. There is no place for man in the world. In addition to the disappearance of divine-spiritual existence from the appearance of perception, the human being therefore lost, in the course of time, his conceptions of the world's beginning and end. Within these ideas he could still find his own value and see himself within the cosmos as a being connected with the beginning and end of the earth.

How did the people of past eras view history? No matter in what form they saw it, history was something that moved from the beginning to the end of the earth, receiving its meaning through the conceptions of the beginning and end of the earth. Take any of the pagan cosmologies, and they will enable you to conceive of humanity's historical development. They reach back to ages in which earthly life arises in a divine-spiritual weaving. History has a meaning. If we turn to the beginning and also the end of the earth, history has a meaning. Whereas the conception of the end of the earth, as a pictorial view contained in religious feeling, continued to exist even in more recent eras, the conception of the end of the earth lived on in historical considerations, as a kind of straggler, even in more recent times. In enlightened historical works, such as Rotteck's history of the world,16Karl Wenzeslaus Rodecker von Rotteck, historian, 1775–1840, General History, 1813–1818, 6 volumes. you may still find the influence of this conception of the earth's beginning, which gives a meaning to history. Even if only a shadow remains of this conception of the beginning of the earth in Rotteck's history, which was written at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it still gives historical development a meaning. The significant, peculiar fact is that at the same time in which the human being entered a world of perception of appearance, perceiving outer nature, therefore, as appearance, history began to lose its meaning and became inaccessible to direct human knowledge, because he no longer had any notion of the earth's beginning and end.

You must take this matter quite seriously. Take the primordial mist at the beginning of the earth's evolution, from which indefinite forms first condensed themselves, and then all the beings, ascending as far as man; and consider the death by heat at the end of the earth's evolution, in which everything perishes. In between lies what we tell about Moses, abut the great individuals of ancient China, about the great individuals of ancient India, Persia, Egypt—and further on, of Greece and Rome, as far as our present time. In thought we may add all that is still to come. All this takes place on the earth, however, like an episode, with no beginning and no end. History thus appears to have no meaning. This must be realized.

Nature may be surveyed, even if we cannot survey its inner being. It rises up before the human being as appearance in that man experiences nature between birth and death. History becomes meaningless. Man simply lacks courage enough in our time to admit that history has no meaning; it is meaningless, because man has lost track of the beginning and end of the earth. Man should really sense that humanity's historical development is the greatest of riddles. He should say to himself that this historical development has no meaning.

Individuals have had inklings of this. Read what Schopenhauer wrote on the absence of meaning in history that emerges out of occidental beliefs. You will see, then, that Schopenhauer really sensed this absence of meaning in history. We should be filled with the longing to rediscover the meaning of history in another way. Out of the world of appearance we can develop a satisfactory knowledge of nature, particularly in Goethe's sense, if we give up hypotheses and remain in the phenomenology, that is, in the teachings of appearance, of semblance. Natural science can be satisfying if we eliminate all the disturbing hypotheses about the beginning and end of the earth. We are then as it were imprisoned, however, in our earthly cave, and we do not look out of it. The Kant-Laplace theory and the end of the world by heat block our view into the distant past and the distant future.

This is basically the situation of present-day humanity from the standpoint of general consciousness; consequently humanity is threatened by a certain danger. It cannot quite enter into the mere world of phenomena, into the world of appearance. Above all it is unable to enter with the inner life into this world of appearance. Humanity wishes to submit to the necessity, the inner necessity of the instincts, drives, and passions. Today we do not see much of everything that may be realized on the basis of free impulses born out of pure thinking. Just as much, however, as the human being lacks freedom here in his life between birth and death, so he is overcome, with the hypnotizing compulsion between death and a new birth, by lack of freedom, by the necessity in perception. Man is therefore threatened by the danger of passing through the portal of death without taking with him his own being and without entering into something free regarding the world of perception, but rather into something that submerges him into a state of compulsion, which makes him grow rigid, as it were, in the outer world.

The impulse that in the future must break into the life of humanity is the appearance of the divine-spiritual to the human being in a way different from the way in which it appeared to him in ancient times. In past ages the human being could imagine a spiritual element within the physical at the beginning and end of the earth, with which he knew he was united and that did not exclude him. The human being must take up this permeation with the spiritual more and more from the center, instead of from the beginning and end. Even as in the Old Testament the beginning of the earth was looked upon as a genesis of the human being, within which his existence was ensured, even as the pagan cosmogonies spoke of humanity's evolution out of divine-spiritual existence, even as the contemplation of the end of the earth, which—as was stated—was still contained in the views of the decline of the world, which do not deprive man of his own self, so modern times must find in a right view of the Mystery of Golgotha, at the center of the earth's evolution, that which again enables the human being to find divine life and earthly life interwoven.

Man must understand in the right way how God passed through the human being with the Mystery of Golgotha. This will replace what we lost regarding the beginning and end of the earth. There is an essential difference, however, between the way in which we should now look upon the Mystery of Golgotha and the earlier way of looking at the beginning and end of the earth.

Try to penetrate into the way in which a pagan cosmogony arose. Today we often come across conceptions stating that these pagan cosmogonies were fabrications of the people. This conception holds that just as today man freely joins thought to thought and disconnects them again, so at one time people devised their cosmogonies. This, however, is an erroneous university view, which has no reasonable foundation. We find instead that in the past the human being gave himself up entirely to the contemplation of the world; he could see the beginning of the world only in the way in which it appeared to him in the cosmogony, in the myths. There was no freedom in this; it was altogether something that yielded itself to man by necessity. The human being had to look into the beginning of the earth; he could not refrain from doing so, he could do nothing else. Today we no longer picture in the right way how in the past man's soul pictured the beginning of the earth and, in a certain respect, also the end of the earth, through an instinctive knowledge.

Today it is impossible for the human soul to picture the Mystery of Golgotha in this way. This constitutes the great difference between Christianity and the ancient teachings of the gods. If the human being wishes to find Christ, he must find Him in freedom. He must freely acknowledge the Mystery of Golgotha. The content of the ancient cosmogonies was forced upon man, whereas the Mystery of Golgotha does not force itself upon him. He must approach the Mystery of Golgotha in a certain resurrection of his being, in freedom.

The human being is led to such freedom by an activity that I have recently designated in anthroposophical spiritual science as the activity of knowing. If a theologian believes that he may gain knowledge of the Akashic Chronicle in a special illustrated edition, that is to say, without needing to exert any inner activity to grasp what must appear before his soul in concepts and must become images—such a theologian would simply show that he is predisposed to grasp the world only in a pagan way, not in a Christian way; for the human being must come to Christ in inner freedom. Particularly the way in which the human being must face the Mystery of Golgotha constitutes his most intimate means of an education toward freedom.

The human being is in a certain sense torn away from the world by the Mystery of Golgotha if it is experienced rightly. What arises in that case? In the first place, the human being now can live in a world of perception, of appearance, and in this world surges up something that leads him to the spiritual existence that is guaranteed in the Mystery of Golgotha. This is one thing. The other thing, however, is that history has ceased to have meaning, because beginning and end were lost; it receives meaning again because it is given this meaning from the center. We learn to recognize how everything before the Mystery of Golgotha leads toward the Mystery of Golgotha and how everything after the Mystery of Golgotha sets out from this mystery.

History thus once more acquires meaning, whereas otherwise it is an illusory episode without beginning and without end. The outer world of perception faces the human being as appearance for the sake of his freedom, changing history into something it should not be—an episode of appearance without any center of gravity. It dissolves into fog and mist which basically we already find theoretically in Schopenhauer's writings.

Through the inclination toward the Mystery of Golgotha, all that was once otherwise historical appearance receives inner life, historical soul, connected with everything that modern man requires through the fact that he must develop freedom in life. When he passes through the portal of death, he will have developed here the great teaching of freedom. Avowal of the Mystery of Golgotha cast into life the light that must fall on everything that is free in the human being. The human being has the possibility of saving himself from the danger that he has here by virtue of the predisposition for freedom that he has in appearance but does not develop, because he surrenders himself to instincts and drives and therefore falls prey to necessity after death. By accepting as his own a religious faith that is totally different from more ancient religious faith, in filling his entire soul only with a religious faith living in freedom, he transforms himself for the experience of freedom.

In today's civilization, basically only a small number of people have really grasped that only a knowledge gained in freedom, an active knowledge, is able to lead us to Christ, to the Mystery of Golgotha. The Bible gave man a historical account so that he might have a message of the Mystery of Golgotha for the time when he could not yet take in spiritual science.

To be sure, the Gospel will never lose its value. It will acquire an ever-greater value, but to the Gospel must be added the direct knowledge of the essence of the Mystery of Golgotha. Christ must be able to be sensed, felt, known through one's own human force, not only through the forces working out of the Gospel. This is what spiritual science strives for regarding Christianity Spiritual science seeks to explain the Gospels, but it is not based upon the Gospels. It is able to appreciate the Gospels so fully just because it discovered afterward, as it were, all that lies concealed in them, all that has already been lost in the course of humanity's outer evolution.

The whole modern evolution of humanity is thus connected on the one hand with freedom, the appearance of perception, and on the other with the Mystery of Golgotha and the meaning of historical development. This sequence of many episodes which constitutes history as it is generally described and accepted today acquires its true significance only if the Mystery of Golgotha can be inserted into historical evolution.

Many people experienced this in the right way and they used the right images for it. They said to themselves: once upon a time, man looked out into the heavenly expanses; he saw the sun, but not the sun as we see it today. Today there are physicists who believe that out there in the universe there floats a large sphere of gaseous matter. I have frequently said that physicists would be astonished if they could build a cosmic balloon and reach the sun, for where they suppose the existence of a gaseous sphere, they would find negative space, which would transport them in a moment not only into nothingness but beyond nothingness, far beyond the sphere of nothingness. The modern materialistic cosmologies developed today are pure fantasy. In more ancient times, people did not picture the sun as a gaseous sphere floating in heavenly space; .the sun in their view, was a spiritual being. Even today the sun is a spiritual being to those who contemplate the world in a real way; it is a spiritual being manifesting itself only outwardly in the way in which the eye is able to perceive the sun. This central spiritual being was experienced by a more ancient humanity as one with the Christ. When speaking of Christ, the ancients pointed to the sun. More recent humanity must now not point away from the earth but rather toward the earth when it speaks of the Christ. It must search for the sun in the Man of Golgotha.

By recognizing the sun as a spiritual being, it was possible to connect a conception worthy of the human being with the beginning and end of the earth. The conception of Jesus, in whom Christ dwelt, renders possible a conception worthy of the human being regarding the middle of the earth's evolution; from there will ray out toward beginning and end that which will once more make the whole cosmos appear in a light that gives man his place in the universe. We should therefore live toward a time in which hypotheses concerning the world's beginning and end will not be constructed on the basis of materialistic, natural scientific conceptions, but which will proceed from the knowledge of the Mystery of Golgotha. This will also enable us to survey all of cosmic evolution. In the outwardly luminous sun, the ancient human being sensed the Christ of the outer world. The true knowledge of the Mystery of Golgotha enables man to see in the historical evolution of the earth the sun of this earthly evolution through Christ. The sun shines outside in the world and also in history—it shines physically outside and spiritually in history; sun here and sun there.

This indicates the path to the Mystery of Golgotha from the viewpoint of freedom. Modern humanity must find it, if it wishes to transcend the forces of decline and enter the forces of ascent. This should be realized deeply and thoroughly. This knowledge will not be abstract, not merely theoretical, but one that fills the whole human being. It will be a knowledge that must be felt, must be experienced in feeling. The Christianity about which anthroposophy must speak will not be a looking to Christ but a being filled with Christ.

People would always like to know the difference between anthroposophy and what lived as the older theosophy. Is this difference not evident? The older theosophy has warmed up the pagan cosmologies. In the theosophical literature you will discover everywhere warmed-up pagan cosmologies, which are no longer suited to modern human beings; although theosophy speaks of the earth's beginning and end, this no longer means what it meant in the past. What is missing in these writings? The center is missing, the Mystery of Golgotha is missing throughout. It is missing to an even greater extent than in outer natural science.

Anthroposophy has a continuing cosmology that does not extinguish the Mystery of Golgotha but accepts it, so that this Mystery is contained within it. The whole evolution, reaching back as far as Saturn and forward as far as Vulcan, is seen in such a way that this light enabling us to see will ray out from the knowledge of the Mystery of Golgotha. If we but recognize this principal contrast, we shall no longer have any doubt as to the difference between the older theosophy and anthroposophy.

Particularly when so-called Christian theologians again and again lump together anthroposophy and theosophy, this is due to the fact that they do not really understand much about Christianity. It is deeply significant that Nietzsche's friend, Overbeck,17Franz Overbeck, Protestant theologian, 1837–1905. the truly significant theologian of Basel, wrote a book on the Christianity of modern theology, in which he tried to prove that modern theology—including Christian theology—is no longer Christian. One may therefore say that even here outer science has already drawn attention to the fact that modern Christian theology does not understand or know anything about Christianity.

One should thoroughly understand everything that is unchristian. Modern theology, in any case, is not truly Christian; it is unchristian. Yet people prefer to ignore these things due to their love of ease. They should not be ignored, however, for to the extent to which they are ignored, man will lose the possibility of inwardly experiencing Christianity. This must be experienced, for it is the opposite pole to the experience of freedom, which must emerge. Freedom must be experienced, but the experience of freedom alone would lead human beings into the abyss. Only the Mystery of Golgotha can lead humanity across this abyss.

We shall speak of this more next time.

Elfter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Im Laufe der letzten Betrachtungen zeigte es sich uns, wie grundverschieden des Menschen ganze Anschauung ist, je nachdem er hier zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode oder aber in der geistigen Welt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt lebt. Und wir haben gestern gesagt, daß der Mensch in unserem gegenwärtigen Zeitalter, seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, hier zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode sich erwerben kann die Freiheit, daß dann alles, was er vollbringt aus dem Impuls der Freiheit heraus, seinem Wesen in dem Leben zwischen dem Tod und neuer Geburt gewissermaßen Schwere, Realität, Sein gibt. Gerade wenn wir loskommen hier von den Notwendigkeiten des irdischen Daseins, wenn wir uns erheben zu Motiven für unser Wollen, die frei sind, wenn wir also für unser Wollen nichts aus dem Irdischen heraus nehmen, dann zimmern wir uns dadurch die Möglichkeit, zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt auch ein selbständiges Wesen zu sein. Nur gehört zu diesem gewissermaßen Sein-Selbst-Bewahren nach dem Tode in unserem Zeitalter dazu, was man nennen kann die Beziehung zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha; und man kann ja dieses Mysterium von Golgatha von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus betrachten. Wir haben schon eine große Anzahl von Gesichtspunkten im Laufe der Jahre eingenommen; wir wollen es heute einmal von dem Gesichtspunkte, der sich ergibt durch die Betrachtung des Wertes der Freiheit für den Menschen, anschauen.

[ 2 ] Wenn der Mensch hier auf der Erde zwischen Geburt und Tod lebt, dann hat er ja eigentlich im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein keine Selbstanschauung. Der Mensch kann nicht in sich hineinschauen. Es ist natürlich nur eine Täuschung, wenn eine äußere Wissenschaft durch die Betrachtung dessen, was am Menschen tot ist, zuweilen ja wirklich nur durch die Betrachtung des Leichnams, glaubt, eine Innenerkenntnis der menschlichen Organisation zu gewinnen. Das ist ja durchaus ein Trug, eine Illusion. Der Mensch hat hier zwischen Geburt und Tod nur eine Anschauung der äußeren Welt. Aber was für eine Anschauung der äußeren Welt hat er hier? Er hat diejenige Anschauung, die wir oftmals genannt haben die Anschauung des Scheines, und auch gestern habe ich dies wiederum stark hervorgehoben.

[ 3 ] Wenn wir unsere Sinne hinausrichten in unsere Weltumgebung zwischen Geburt und Tod, dann stellt sich uns die Welt als Erscheinung, als Schein dar. Wir können diesen Schein in unser Ich-Wesen hereinnehmen. Wir können ihn zum Beispiel in der Erinnerung behalten, haben ihn also dann in gewissem Sinne zu unserem Eigentum gemacht. Aber insofern er beim Hinausschauen in die Welt vor uns steht, ist er eben Schein, ein Schein, der sich als solcher noch ganz besonders dadurch zu erkennen gibt, daß er ja, wie ich Ihnen gestern gezeigt habe, im Tode verschwindet und in anderer Form wiederum auftritt, indem er nun nicht mehr in uns erlebt wird, sondern vor uns oder um uns erlebt wird.

[ 4 ] Wenn aber der Mensch zwischen Geburt und Tod im heutigen Zeitalter die Welt nicht als Schein wahrnehmen würde, wenn er den Schein nicht erleben könnte, so könnte er ja nicht frei sein. Die Entwickelung der Freiheit ist nur möglich in der Welt des Scheines. Ich habe das angedeutet in meinem Buche «Vom Menschenrätsel», indem ich darauf hingewiesen habe, daß eigentlich die Welt, die wir erleben, verglichen werden kann mit den Bildern, die uns aus einem Spiegel heraus anschauen. Diese Bilder, die uns aus einem Spiegel heraus anschauen, die können uns nichts aufzwingen; sie sind eben nur Bilder, sie sind Schein. Und so ist das, was der Mensch als Wahrnehmungswelt hat, auch Schein.

[ 5 ] Der Mensch ist ja durchaus nicht etwa ganz nur in den Schein der Welt eingesponnen. Er ist nur mit seinem Wahrnehmen, das sein waches Bewußtsein ausfüllt, eingesponnen in eine Scheinwelt. Aber wenn der Mensch hinblickt auf seine Triebe, auf seine Instinkte, auf seine Leidenschaften, auf seine Temperamente, auf all das, was heraufwogt aus dem menschlichen Wesen, ohne daß er es zu klaren Vorstellungen bringen kann, wenigstens zu wachen Vorstellungen, so ist ja das alles nicht Schein. Es ist schon Wirklichkeit, aber eine Wirklichkeit, die dem Menschen nicht vor das gegenwärtige Bewußtsein tritt. Der Mensch lebt zwischen Geburt und Tod in einer wahren Welt, die er nicht kennt, die aber niemals dazu angetan ist, ihm wirklich die Freiheit zu geben. Instinkte, die ihn unfrei machen, kann sie ihm einpflanzen, innere Notwendigkeiten kann sie hervorbringen, aber nie und nimmer kann sie den Menschen die Freiheit erleben lassen. Die Freiheit kann nur erlebt werden innerhalb einer Welt von Bildern, von Schein. Und wir müssen eben, indem wir aufwachen, in ein Scheinwahrnehmungsleben eintreten, damit sich da die Freiheit entwickeln kann.

[ 6 ] Dieses Scheinleben, das wir als unser waches Wahrnehmungsleben haben, es war nicht immer so innerhalb der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit. Wenn wir zurückgehen in alte Zeiten, in die wir ja schon öfter den Blick zurückgeworfen haben, wo ein gewisses instinktives Schauen vorhanden war oder das, was Nachzügler ist dieses instinktiven Schauens, was ja als Nachzügler gewissermaßen noch fortgedauert hat bis in die Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts, wenn wir da zurückblicken, so können wir nicht im gleichen Sinne sagen, daß der Mensch in seinem wachen Zustande nur eine Scheinwelt um sich hatte. Durch den Schein hindurch sprach ja für den Menschen alles das, was er in seiner Art als den geistigen Hintergrund der Welt sah. Er sah allerdings auch diesen Schein, aber in anderer Weise. Es war dieser Schein für ihn Ausdruck, Offenbarung einer geistigen Welt. Diese geistige Welt ist hinter dem Scheine verschwunden. Der Schein ist geblieben. Das ist das Wesentliche in der Fortentwickelung der Menschheit, daß ältere Zeiten den Schein als die Offenbarung einer göttlich-geistigen Welt empfunden haben, daß aber aus diesem Schein die göttlich-geistige Welt verschwunden ist und der Schein heute dem Menschen vor Augen liegt, damit er innerhalb dieser Scheinwelt seine Freiheit finden kann, daß also der Mensch seine Freiheit in einer Scheinwelt finden muß, daß er in der wahren Welt, die ganz zurückgetreten ist in die dumpfen Erlebnisse des Inneren, keine Freiheit, sondern nur eine Notwendigkeit findet. Man kann also sagen: Lebt der Mensch zwischen Geburt und Tod - alles das, was ich sage, gilt nur für unser Zeitalter -, so ist seine Wahrnehmungswelt eine Scheinwelt. Er nimmt die Welt wahr, aber er nimmt die Welt als Schein wahr.

[ 7 ] Wie ist es nun zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt? Wir haben ja in den letzten Betrachtungen darauf hingewiesen, daß da der Mensch nicht diese äußere Welt wahrnimmt, die er hier gewahr wird zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, sondern daß in der Zeit zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt der Mensch wesentlich den Menschen selbst, das Innere des Menschen sieht. Der Mensch ist dann für den Menschen die Welt. Das, was gerade hier auf der Erde verborgen ist, das ist in der geistigen Welt offenbar. Der ganze Zusammenhang zwischen dem Seelischen und dem Organischen des Menschen, zwischen der Wirksamkeit der einzelnen Organe, kurz, alles, was gewissermaßen, symbolisch gesprochen, innerhalb der menschlichen Haut ist, das durchschaut der Mensch zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt.

[ 8 ] Aber nun ist es wieder für unser Zeitalter so, daß da der Mensch eben nicht dazu kommt, im Scheine zu leben. Das Leben im Scheine ist ihm eigentlich nur gewährt zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Der Mensch kommt heute nicht dazu, zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt im Scheine zu leben. Er wird gewissermaßen gefangengenommen von der Notwendigkeit, wenn er durch den Tod tritt. So frei sich der Mensch fühlt in seinem Wahrnehmen hier auf der Erde, wo er seine Augen hinwenden kann, wohin er will, sich in Begriffen zusammenfassen kann, was er wahrnimmt, in der Weise, daß er sein freies Tun in diesen Begriffen empfindet, so unfrei fühlt sich der Mensch in dieser Beziehung auf die Wahrnehmungswelt zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt. Er wird gewissermaßen hingerissen von der Welt. Es ist geradeso, als ob in dieser Zeit der Mensch so wahrnehmen würde, wie er hier wäre, wenn er gewissermaßen hypnotisiert würde von jeder einzelnen Sinneswahrnehmung, wenn er hingerissen würde von jeder einzelnen Sinneswahrnehmung, so daß er nicht freiwillig von ihr loskommen könnte.

[ 9 ] Das ist die Entwickelung, in die der Mensch eingetreten ist mit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts. Aus dem Schein der Erde sind ihm verschwunden die göttlich-geistigen Welten. In der Zeit zwischen dem 'Tod und einer neuen Geburt nehmen ihn aber diese göttlich-geistigen Welten so gefangen, daß er seine Selbständigkeit ihnen gegenüber nicht bewahren kann. Nur, sagte ich, wenn der Mensch hier wirklich Freiheit entwickelt, das heißt, wenn er seinen ganzen Menschen engagiert für das Scheinleben, dann ist es ihm möglich, auch sein Eigenwesen durch die Todespforte zu tragen. Was aber dazu noch notwendig ist, es kann uns vor Augen treten, wenn wir noch auf einen anderen Unterschied unseres Anschauens von heute mit älteren menschlichen Anschauungen hinblicken.

[ 10 ] Ob wir mehr die allgemeine Menschheit betrachten oder die Eingeweihten und die Mysterien in älteren Zeiten, die ganze Weltanschauung war anders orientiert, als sie heute orientiert ist. Wenn der Mensch bei demjenigen stehenbleibt, was er seit der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts durch die seither aufgekommene Wissensart eben erkennen kann, wenn man auf das hindeutet, so findet man, daß der Mensch sich da Vorstellungen macht über die Erdenentwickelung, Vorstellungen macht über die Entwickelung seiner eigenen Menschengattung; aber es entschwinden ihm solche Vorstellungen, die in irgendeiner befriedigenden Weise auf Erdenanfang und Erdenende hinweisen können. Man möchte sagen, eine gewisse Entwickelungslinie überblickt der Mensch. Er sieht geschichtlich zurück, er sieht geologisch zurück. Aber wenn er weiter zurückgeht, macht er sich Hypothesen. Er stellt an den Anfang den Urnebel (Zeichnung $. 179, waagrechter Strich hell), der ein physisches Gebilde zu sein scheint. Daraus entwickeln sich dann — das heißt, es entwickelt sich nicht, sondern der Mensch bildet sich ein, daß es sich entwickelt - die höheren Wesen der Naturreiche, Pflanzen, Tiere und so weiter. Dann wiederum stellt sich der Mensch vor nach heutigen physikalischen Vorstellungen: Am Ende verfällt das irdische Sein in den Wärmetod (Zeichnung rote Striche rechts) — wiederum eine Hypothese. Der Mensch sieht also gewissermaßen ein Stück zwischen Anfang und Ende. Anfang und Ende verschwimmen als unbefriedigende Gebilde vor dem heutigen Blick des Menschen.

[ 11 ] Das war für ältere Zeiten nicht so. Für ältere Zeiten hatten die Menschen vermöge jenes Sich-Offenbarens des Göttlich-Geistigen im Scheine gerade über Erdenanfang und Erdenende ganz präzise Vorstellungen. Wir können auf das Alte Testament blicken, wir können in andere Religionslehren der Alten blicken: Wir finden im Alten Testamente gerade über den Weltenanfang in der Art, wie es eben damals gegeben werden konnte, Vorstellungen ausgebildet, so daß der Mensch aus diesen Vorstellungen sein eigenes Dasein auf der Erde begreifen konnte. Aus dem Kant-Laplaceschen Urnebel heraus kann niemand das menschliche Dasein jetzt auf der Erde begreifen.

[ 12 ] Wenn Sie die wunderbaren Kosmogonien der verschiedenen heidnischen Völker nehmen, so haben Sie wiederum etwas, woraus der Mensch sein irdisches Dasein begreifen kann. Der Mensch also richtete den Blick auf den Erdenanfang und konnte zu Vorstellungen kommen, die ihn einschlossen. Was dann als Vorstellungen über das Erdenende da war, das hielt sich sogar länger im Bewußtsein der Menschen aufrecht. Wir sehen noch, sagen wir, in Michelangelos «Jüngstem Gericht», in anderen «Jüngsten Gerichten» bis in die neuesten Zeiten hinein Vorstellungen über das Erdenende, die durchaus den Menschen einschließen, die, mögen nun die Vorstellungen über Schuld und Sühne noch so schwierig sein, den Menschen nicht vernichten.

[ 13 ] Nehmen wir die heutige hypothetische Vorstellung über das Erdenende: da ist ja alles in eine gleichmäßige Wärme aufgegangen. Das ganze menschliche Wesen ist abgeschmolzen. Der Mensch hat da keinen Platz. Neben dem also, daß das göttlich-geistige Sein verschwunden ist aus dem Wahrnehmungsschein, sind dem Menschen verlorengegangen im Laufe der Zeit solche Vorstellungen über Erdenanfang und Erdenende, innerhalb welcher er Geltung haben kann, innerhalb welcher er mit dem Erdenanfang und Erdenende sich selber im Kosmos sehen kann.

[ 14 ] Was war denn für diese Menschen, in welcher Gestalt immer sie sie mögen erkannt haben, die Geschichte? Die Geschichte war das, was sich zwischen Erdenanfang und Erdenende bewegte, was einen Sinn bekam durch die Vorstellungen vom Erdenanfang und Erdenende. Nehmen Sie irgendeine heidnische Kosmologie und Sie können sich das geschichtliche Werden der Menschheit vorstellen. Sie gelangen zurück bis in Zeiten, in denen das Irdische aufgeht in einem göttlich-geistigen Weben. Die Geschichte hat einen Sinn. Auch nach vorne hin, nach dem Erdenende, hat die Geschichte einen Sinn. Blieb bis in die neueren Zeiten herein für das bildhafte Anschauen, für das religiöse Empfinden mehr erhalten die Vorstellung von dem Erdenende, so blieb für die geschichtliche Betrachtung der Erdenanfang noch in einer gewissen Weise bis in die neuesten Zeiten wie ein Nachzügler durchaus vorhanden. Bis in solch aufgeklärte Geschichtswerke wie die Rottecksche Weltgeschichte finden Sie noch das Nachwirken dieser Vorstellung vom Erdenanfang, die der Geschichte einen Sinn gibt. Wenn das auch nur noch ein Schatten ist über den Erdenanfang in Rottecks Weltgeschichte, die ja im Anfange des 19. Jahrhunderts geschrieben worden ist, es gibt das dem geschichtlichen Werden noch einen Sinn. Das ist das Bedeutsame, das Eigentümliche, daß in derselben Zeit, in der der Mensch eintritt in eine Wahrnehmungswelt des Scheines, indem ihm also die äußere Natur als Schein vor sein Wahrnehmen tritt, daß in dieser Zeit für das unmittelbare menschliche Wissen die Geschichte wegen des Fehlens von Erdenanfang und Erdenende ihren Sinn verliert.

[ 15 ] Nehmen Sie nur diese Sache völlig ernst. Nehmen Sie am Ausgangspunkte der Erdenentwickelung einen Urnebel, aus dem sich herausballen zuerst unbestimmte Gestalten, dann alle Wesen, die dann heraufkommen bis zum Menschen, und nehmen Sie am Erdenende den Wärmetod, in dem alles erstirbt, und dazwischen dasjenige, was wir erzählen meinetwillen von Moses, von den alten chinesischen Größen, von den alten indischen, persischen, ägyptischen Größen bis über Griechenland, bis über Rom hinaus, bis in unsere Zeiten, zu dem wir hinzufügen in Gedanken, was etwa noch kommen möchte - es spielt sich auf der Erde ab wie eine Episode ohne Anfang und ohne Ende. Sinnlos erscheint die Geschichte.

[ 16 ] Man muß sich das nur einmal klarmachen. Die Natur ist zu überschauen, wenn auch nicht in ihrem Inneren. Als Schein tritt sie vor den Menschen, indem er sie erlebt zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode. Die Geschichte wird sinnlos. Und der Mensch ist nur nicht mutig genug in unserer Zeit, sich zu gestehen, daß die Geschichte sinnlos ist, sinnlos aus dem Grunde, weil ihm entfallen ist Erdenanfang und Erdenende. Der Mensch müßte eigentlich heute das größte Rätsel empfinden gegenüber dem geschichtlichen Werden der Menschheit. Er müßte sich sagen: Sinnlos ist dieses geschichtliche Werden.

[ 17 ] Einzelne haben das geahnt. Lesen Sie bei Schopenhauer nach, was er über die Sinnlosigkeit der Geschichte aus dem abendländischen Glauben heraus vorgebracht hat, dann werden Sie eben sehen, daß Schopenhauer diese Sinnlosigkeit durchaus empfunden hat. Es muß auftreten das Verlangen, in einer anderen Weise den Sinn der Geschichte wiederum zu finden. Aus der Welt, die wir genügend finden können für die Naturerkenntnis, aus der Welt des Scheines, aus ihr heraus können wir uns gerade im Goetheschen Sinne eine befriedigende Naturerkenntnis bilden, wenn wir auf Hypothesen verzichten und in der Phänomenologie, das heißt in der Scheinlehre, in der Erscheinungslehre stehenbleiben. In der Naturlehre kann Befriedigung sein, wenn wir uns nur enthalten der störenden Hypothesen über Erdenanfang und Erdenende. Aber wir sind dann gewissermaßen in unserer Erdenhöhle eingeschlossen; wir sehen nicht heraus. Die Kant-Laplacesche Theorie und der Wärmetod verbauen uns den Ausblick in die zeitlichen Weltenweiten.

[ 18 ] Im Grunde genommen ist das die Lage, in der nach dem allgemeinen Bewußtsein doch die gegenwärtige Menschheit lebt. Daher droht ihr eine gewisse Gefahr. Sie kann sich nicht recht einleben in die bloße Welt der Phänomene, in die Welt des Scheines. Vor allen Dingen mit dem inneren Leben kann sie sich nicht in diese Welt des Scheines einleben. Sie will sich der Notwendigkeit, der inneren Notwendigkeit übergeben, den Instinkten, Trieben, Leidenschaften. Wir sehen ja heute wenig von dem verwirklicht, was aus der freien Impulsivität des reinen Denkens hervorgeht. Aber ebensoviel als dem Menschen hier im Leben zwischen Geburt und Tod mangelt an Freiheit, ebensoviel kommt mit dem hypnotisierenden Zwange zwischen Tod und neuer Geburt von Unfreiheit, von Notwendigkeit in der Wahrnehmung über ihn. So daß dem Menschen die Gefahr droht, daß er durch die Todespforte schreitet, sein eigenes Wesen nicht mitnehmen kann, aber für die Wahrnehmungswelt sich nicht einlebt in etwas Freies, sondern in etwas, was ihn untertauchen läßt in Zwangsverhältnisse, was ihn wie erstarren macht in der äußeren Welt.

[ 19 ] Was da einschlagen muß in das Leben der Menschheit gegen die Zukunft hin, das ist, daß dem Menschen in anderer Weise das Göttlich-Geistige erscheint, als es ihm erschienen ist in alten Zeiten. In alten Zeiten konnte sich der Mensch an Erdenanfang und Erdenende innerhalb des Physischen ein Geistiges denken, mit dem er sich eins wissen konnte, das ihn nicht ausschloß. Immer mehr und mehr aber muß der Mensch von der Mitte dieses Durchgeistigten aufnehmen, statt von Anfang und Ende (siehe Zeichnung, senkrechter Strich Mitte). Und wie man im Alten Testamente am Erdenanfang sah eine Genesis des Menschen, innerhalb welcher sein Sein gesichert war, wie man hatte in heidnischen Kosmogonien ein Sich-Herausentwickeln der Menschheit, aus göttlich-geistigem Dasein, wie man hat ein Hinblicken auf das Erdenende, das sich noch erhalten hat, wie gesagt, in den Anschauungen vom Weltenuntergang, die dem Menschen auch nicht sein Sein vor sich selber nehmen, so muß sich in der neueren Zeit in einer richtigen Anschauung vom Mysterium von Golgatha für die Mitte der Erdenentwickelung dasjenige finden, wo man wiederum Göttliches und Irdisches ineinanderschaut. Recht verstehen muß der Mensch, wie der Gott durch den Menschen gegangen ist mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Dann ist ihm das dafür gegeben, was ihm entfallen ist für Erdenanfang und Erdenende. Aber es ist ein wesentlicher Unterschied zwischen diesem Hinblicken auf das Mysterium von Golgatha und dem früheren Hinblicken auf Erdenanfang und Erdenende.

[ 20 ] Versetzen Sie sich nur recht in das Entstehen einer heidnischen Kosmogonie. Es gibt ja allerdings heute vielfach die Vorstellung, daß diese heidnischen Kosmogonien Erdichtungen der Völker sind. Man hat die Vorstellung: So wie heute der Mensch seine Gedanken in Freiheit aneinanderkuppelt und wieder auseinanderreißt, so haben einstmals die Menschen ihre Kosmogonien ausgesponnen. Aber das ist ja nur eine verirrte Universitätsansicht und geht die Vernunft nichts an. Worum es sich handelt, das ist, daß der Mensch ganz so drinnenstand im Weltenanschauen, daß er nicht anders konnte als in dieser Weise hinschauen auf den Weltenanfang, wie es sich ihm in der Kosmogonie, in den Mythen darstellte. Es war darin keine Freiheit, es war durchaus etwas, was sich dem Menschen mit Notwendigkeit ergab. Er mußte hineinschauen in den Erdenanfang; er konnte gar nicht anders, er konnte das nicht unterlassen. Das stellt man sich heute gar nicht mehr richtig vor, wie da der Mensch durch einen instinktiven Erkenntnisgehalt sich den Erdenanfang, in gewisser Beziehung auch das Erdenende, vor die Seele stellte.

[ 21 ] So kann sich der Mensch heute das Mysterium von Golgatha nicht vor die Seele stellen. Das ist der große Unterschied beim Christentum gegenüber den alten Götterlehren. Wenn der Mensch den Christus finden will, dann muß er ihn in Freiheit finden. Er muß sich frei zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha bekennen. Der Inhalt der Kosmogonien drängte sich dem Menschen auf. Das Mysterium von Golgatha drängt sich dem Menschen nicht auf. Er muß in einer gewissen Auferstehung seines Wesens in Freiheit an das Mysterium von Golgatha herankommen.

[ 22 ] Zu einer solchen Freiheit wird der Mensch geführt durch das, was ich in diesen Tagen als die Aktivität des Erkennens bei anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft bezeichnet habe. Wenn ein Pastor meint, er könne die «Akasha-Chronik» in einer «illustrierten Prachtausgabe» empfangen, also, er könne sie so empfangen, daß er sich nicht in innerer Aktivität anzustrengen brauchte um das, was zwar in Begriffen vor seine Seele treten muß, was aber zu Bildern werden muß, so zeigt er, daß er nur veranlagt ist, dieser Pastor, für eine heidnische Erfassung der Welt, nicht für eine christliche Erfassung; denn zu dem Christus muß der Mensch in innerlicher Freiheit kommen. Gerade wie sich der Mensch zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha stellen muß, gehört zu seinen intimsten Erziehungsmitteln zur Freiheit.

[ 23 ] Der Mensch wird gewissermaßen schon durch das Mysterium von Golgatha, wenn er es richtig erlebt, losgerissen von der Welt. Was tritt denn da ein? Erstens: Der Mensch kann jetzt in einer Scheinwahrnehmungswelt leben, denn in dieser Scheinwahrnehmungswelt wogt etwas auf, was ihn zu einem geistigen Sein führt, zu dem geistigen Sein, das garantiert ist in dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Das ist das eine. Das andere aber ist: Die Geschichte hat aufgehört, Sinn zu haben, weil Anfang und Ende weggefallen sind; sie bekommt wiederum einen Sinn, weil ihr dieser Sinn von der Mitte aus gegeben wird. Man lernt erkennen, wie alles das, was vor dem Mysterium von Golgatha liegt, hintendiert, hinzielt zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha, wie alles, was nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha liegt, ausgeht von diesem Mysterium von Golgatha. Die Geschichte bekommt wiederum einen Sinn, während sie sonst eine Scheinepisode ist ohne Anfang und ohne Ende. Indem dem Menschen die äußere Wahrnehmungswelt als Scheinwelt gegenübertritt wegen seiner Freiheit, wird ihm die Geschichte, die das nicht darf, zu einer Scheinepisode; sie steht ohne Schwerpunkt da. Sie löst sich auf in Dunst und Nebel, was sie im Grunde genommen schon bei Schopenhauer theoretisch tat. Durch dieHinneigung zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha bekommt das, was sonst geschichtlicher Schein ist, innerliches Leben, geschichtliche Seele, und zwar eine solche, die verbunden ist mit alldem, was der Mensch im modernen Zeitalter braucht, was er braucht, weil er angewiesen ist darauf, daß sein Leben sich in Freiheit entwickelt. Wenn er durchgeht durch die Pforte des Todes, hat er sich hier die große Lehre der Freiheit entwickelt, Freiheitsentfaltung angeeignet. Das Bekenntnis zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha, das wirft hinein in das Leben das Licht, das sich ausgießen muß über alldem, was frei ist im Menschen. Und der Mensch hat die Möglichkeit, sich vor der Gefahr zu retten, daß er hier im Scheine die Veranlagung für die Freiheit hat, diese Freiheit aber nicht entwickelt, weil er den Instinkten, den Trieben sich hingibt, nach dem Tode daher der Notwendigkeit verfällt. Indem er nun ein religiöses Bekenntnis, das ganz anderer Art ist als die älteren religiösen Bekenntnisse, zu dem seinigen macht, indem er ein nur in der Freiheit lebendes religiöses Bekenntnis seine ganze Seele ausfüllen läßt, artet er sich zum Erleben der Freiheit um.

[ 24 ] Das ist es nämlich, was im Grunde genommen nur wenigen Menschen der heutigen Zivilisation aufgegangen ist: daß erst die Erkenntnis in Freiheit, die Erkenntnis in Aktivität zu dem Christus, zu dem Mysterium von Golgatha führen kann. Den Menschen war die historische Nachricht der Bibel gegeben, damit sie für diejenige Zeit, in welcher sie noch nicht Hinneigung haben konnten für Geisteswissenschaft, eine Kunde von dem Mysterium von Golgatha erhalten haben.

[ 25 ] Gewiß, das Evangelium wird niemals seinen Wert verlieren. Es wird einen immer größeren Wert bekommen, aber zu dem Evangelium muß hinzutreten die unmittelbare Erkenntnis des Wesens des Mysteriums von Golgatha. Der Christus muß auch durch die menschliche Kraft allein, nicht bloß durch die aus den Evangelien wirkende Kraft, erkannt, gefühlt, empfunden werden können. Das ist es ja, was für das Christentum durch die Geisteswissenschaft angestrebt wird. Die Geisteswissenschaft versucht, die Evangelien zu erklären. Sie fußt aber nicht auf den Evangelien. Sie schließt nicht aus den Evangelien. Sie kommt gerade dadurch zu ihrer hohen Bewertung der Evangelien, weil sie gewissermaßen hinterher entdeckt, was alles in den Evangelien steckt und was ja im Grunde genommen für die äußere Menschheitsentwickelung schon verlorengegangen ist.

[ 26 ] So hängen mit der ganzen neueren Menschheitsentwickelung auf der einen Seite die Freiheit, der Wahrnehmungsschein und auf der anderen Seite das Mysterium von Golgatha und der Sinn des geschichtlichen Werdens zusammen. Dieser Ablauf von allerlei Episoden, wie man ihn heute kennenlernt in der landläufigen geschichtlichen Darstellung, er bekommt eben erst Gewichtigkeit, wenn man das Mysterium von Golgatha in die geschichtliche Entwickelung hineinstellen kann.

[ 27 ] Das wurde von vielen Leuten doch in der richtigen Weise empfunden, und sie haben das richtige Bild dafür gebraucht. Sie haben sich gesagt: Man hat einstmals hinausgeschaut in die Himmelsweiten, man hat die Sonne erblickt, aber die Sonne nicht so erblickt, wie sie heute erblickt wird, so daß es Physiker gibt, die da glauben, da draußen schwimme im Weltenall ein großer Gasball. Ich habe es oft gesagt: Die Physiker würden sehr erstaunt sein, wenn sie einen Weltballon bauen könnten — und da, wo sie einen großen Gasball vermuten, würden sie negativen Raum finden, der sie im Nu überhaupt nicht nur in das Nichts, sondern jenseits des Nichts hinüber, weit hinüber über die Sphäre des Nichts befördern würde. Das, was man da an materialistischen Kosmologien heute entwickelt, das ist ja pure Phantasterei. So hat man sich nicht vorgestellt in älteren Zeiten: die Sonne - ein Gasball, der da draußen schwimmt, sondern die Sonne war ein Geistwesen. Das ist sie auch für den wirklichen Weltanschauer heute noch: ein Geistwesen, das sich nur äußerlich in der Weise repräsentiert, wie das Auge eben die Sonne wahrnehmen kann. Und dieses zentrale Geistwesen empfand die ältere Menschheit als eins mit dem Christus. Die ältere Menschheit wies auf die Sonne, wenn sie von dem Christus sprach.

[ 28 ] Die neuere Menschheit muß nun nicht von der Erde hinausweisen, sondern auf die Erde weisen, wenn sie von dem Christus spricht, muß die Sonne in dem Menschen von Golgatha suchen. Mit der Anerkenntnis der Sonne als eines Geistwesens war eben verbunden eine menschenmögliche Vorstellung von Erdenanfang und Erdenende. Mit der Vorstellung von dem Jesus, in dem der Christus gewohnt hat, ist eine menschenmögliche und menschenwürdige Vorstellung der Erdenmitte möglich, und von da wird ausstrahlen nach Anfang und Ende hin, was wiederum den ganzen Kosmos so erscheinen läßt, daß der Mensch in ihm Platz hat. Man muß also einer Zeit entgegenleben, in der nicht aus den materialistischen naturwissenschaftlichen Vorstellungen Hypothesen gebaut werden über Erdenanfang und Erdenende, sondern in der ausgegangen wird von der Erkenntnis des Mysteriums von Golgatha, und davon ausgehend das kosmische Werden auch überschaut wird. Mit der äußerlich leuchtenden Sonne empfand der alte Mensch den außerweltlichen Christus. Mit der richtigen Erkenntnis des Mysteriums von Golgatha erschaut der Mensch innerhalb des geschichtlichen Erdenwerdens die Sonne dieses Erdenwerdens durch den Christus. Es glänzt so draußen in der Welt, es glänzt so in der Geschichte - draußen physisch, in der Geschichte geistig: Sonne dort, Sonne da.

[ 29 ] Das gibt vom Gesichtspunkte der Freiheit aus den Weg zum Mysterium von Golgatha. Ihn muß die neuere Menschheit finden, wenn sie über die Niedergangskräfte hinaus in Aufgangskräfte hineinkommen will.

[ 30 ] Das muß eben ganz tief und gründlich erkannt werden. Und diese Erkenntnis wird keine abstrakte, keine theoretische bloß sein, diese Erkenntnis wird eine solche sein, die den ganzen Menschen ausfüllt, eine zu erfühlende und im Gefühl zu erlebende Erkenntnis. Nicht bloß ein Hinschauen zu Christus, ein Erfülltsein mit Christus wird das Christentum sein, von dem Anthroposophie wird sprechen müssen.

[ 31 ] Man möchte immer den Unterschied wissen zwischen dem, was als ältere Theosophie gelebt hat, und Anthroposophie. Liegt dieser Unterschied nicht auf der Hand? Die ältere Theosophie hat wieder aufgewärmt die heidnische Kosmologie. Überall finden Sie in der Literatur der Theosophie die heidnische Kosmologie aufgewärmt, die für den modernen Menschen nicht paßt; sie redet ihm allerdings von Erdenanfang und Erdenende, aber das ist für ihn nicht mehr so. Und was fehlt diesen Schriften? Gerade diesen Schriften der älteren Theosophie fehlt die Mitte, fehlt überall das Mysterium von Golgatha. Und es fehlt ihnen gründlicher als selbst der äußeren Naturwissenschaft.

[ 32 ] Anthroposophie hat eine fortlaufende Kosmologie, die nicht auslöscht das Mysterium von Golgatha, sondern es aufnimmt, so daß es darinnen ist. Und alle Entwickelung bis in die Saturnzeit zurück, bis zur Vulkanzeit vorwärts wird so gesehen, daß das Licht für dieses Sehen ausstrahlt von der Erkenntnis des Mysteriums von Golgatha. Man muß nur den guten Willen haben, solch einen prinzipiellen Gegensatz anzuerkennen, dann wird man über den Unterschied zwischen älterer ’Theosophie und der Anthroposophie gar keinen Zweifel haben können.

[ 33 ] Und wenn insbesondere auch sogenannte christliche Theologen immer wieder und wieder zusammenstellen Anthroposophie und Theosophie, so rührt das lediglich davon her, daß diese christlichen Theologen eben vom Christentum nicht viel verstehen. Es ist ja doch tief bedeutsam, daß Nietzsches Freund, der wirklich bedeutende Basler Theologe Overbeck, sein Buch geschrieben hat über die Christlichkeit der modernen Theologie, indem er den Nachweis zu erbringen suchte, daß die moderne Theologie, auch die christliche Theologie, eben nicht mehr christlich ist. So daß man sagen kann: Hier wurde auch schon von äußerer Wissenschaft darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß die moderne christliche Theologie vom Christentum nichts versteht, nichts weiß.

[ 34 ] Man sollte nur einmal gründlich erkennen, was alles zum Unchristlichen gehört. Die moderne Theologie gehört jedenfalls nicht zum Christlichen, sondern zum Unchristlichen. Aber diese Dinge möchten sich die Menschen aus Bequemlichkeit aus ihrer Erkenntnis auch hinwegwischen. Sie dürfen aber nicht hinweggewischt werden, denn so viel wie weggewischt wird, so viel verliert der Mensch an Möglichkeit, das Christentum wirklich innerlich zu erleben. Das muß erlebt werden, muß erlebt werden, weil es der andere Pol ist zu dem Freiheitserleben, das heraufkommen muß. Freiheit allein aber erlebt - erlebt werden muß sie -, würde den Menschen in den Abgrund hineinführen. Der Führer über diesen Abgrund kann ihm eben nur das Mysterium von Golgatha sein.

[ 35 ] Davon dann das nächste Mal weiter.

Eleventh Lecture

[ 1 ] In the course of our last reflections, it became clear to us how fundamentally different the whole view of human beings is, depending on whether they live here between birth and death or in the spiritual world between death and a new birth. And yesterday we said that in our present age, since the middle of the 15th century, human beings can acquire freedom here between birth and death, so that everything they accomplish out of the impulse of freedom gives their being in the life between death and new birth a kind of weight, reality, and existence. Precisely when we detach ourselves from the necessities of earthly existence, when we rise to motives for our will that are free, when we take nothing from the earthly realm for our will, then we build for ourselves the possibility of also being an independent being between death and a new birth. However, in our age, what belongs to this preservation of self after death is what can be called the relationship to the mystery of Golgotha; and this mystery of Golgotha can be viewed from many different perspectives. We have already taken a large number of viewpoints over the years; today we want to look at it from the viewpoint that arises from considering the value of freedom for human beings.

[ 2 ] When human beings live here on earth between birth and death, they do not actually have any self-perception in their ordinary consciousness. Human beings cannot look inside themselves. It is, of course, only an illusion when an external science, by observing what is dead in human beings, sometimes believes it can gain inner knowledge of the human organization, really only by observing the corpse. This is completely false, an illusion. Between birth and death, human beings have only a perception of the external world. But what kind of perception of the external world do they have here? They have the perception that we have often called the perception of appearances, and I emphasized this again strongly yesterday.

[ 3 ] When we direct our senses out into our worldly environment between birth and death, the world presents itself to us as appearance, as appearance. We can take this appearance into our ego-being. We can, for example, keep it in our memory, thus making it our property in a certain sense. But insofar as it stands before us when we look out into the world, it is precisely an appearance, an appearance that reveals itself as such in a very special way, namely in that, as I showed you yesterday, it disappears in death and reappears in another form, in that it is no longer experienced within us but is experienced before us or around us.

[ 4 ] But if, between birth and death in the present age, human beings did not perceive the world as appearance, if they could not experience appearance, they could not be free. The development of freedom is only possible in the world of appearance. I hinted at this in my book The Riddle of Man, pointing out that the world we experience can actually be compared to the images that look back at us from a mirror. These images that look back at us from a mirror cannot impose anything on us; they are just images, they are appearance. And so what man has as his world of perception is also appearance.

[ 5 ] Man is by no means entirely entangled in the appearance of the world. He is only entangled in a world of appearances through his perception, which fills his conscious mind. But when humans look at their drives, their instincts, their passions, their temperaments, at everything that wells up from the human being without them being able to form clear ideas, at least conscious ideas, then all of that is not appearance. It is already reality, but a reality that does not appear to humans in their present consciousness. Between birth and death, humans live in a real world that they do not know, but which is never capable of giving them true freedom. It can implant instincts that make them unfree, it can produce inner necessities, but it can never, ever allow humans to experience freedom. Freedom can only be experienced within a world of images, of appearances. And we must, by waking up, enter into a life of apparent perception so that freedom can develop there.

[ 6 ] This apparent life, which we have as our waking life of perception, has not always been so in the historical development of humanity. If we go back to ancient times, to which we have often looked back, when a certain instinctive way of seeing existed, or what remained of this instinctive way of seeing, which continued to exist in a residual form until the middle of the 15th century, if we look back to that time, we cannot say in the same sense that human beings in their waking state had only an illusory world around them. Through the illusion, everything that human beings saw in their own way as the spiritual background of the world spoke to them. They did see this illusion, but in a different way. For them, this illusion was the expression, the revelation of a spiritual world. This spiritual world has disappeared behind the illusion. The appearance has remained. This is the essence of the further development of humanity, that in earlier times people perceived the appearance as the revelation of a divine-spiritual world, but that the divine-spiritual world has disappeared from this appearance and that the appearance is now before the eyes of human beings so that they can find their freedom within this world of appearances.-spiritual world, but that the divine-spiritual world has disappeared from this appearance and that appearance now lies before human beings so that they can find their freedom within this world of appearance, so that human beings must find their freedom in a world of appearance, so that in the true world, which has completely receded into the dull experiences of the inner life, they find no freedom, but only necessity. One can therefore say: If man lives between birth and death—and everything I say applies only to our age—then his world of perception is an illusory world. He perceives the world, but he perceives the world as an illusion.

[ 7 ] What is it like between death and a new birth? In our last reflections, we pointed out that human beings do not perceive the external world that they become aware of between birth and death, but that in the time between death and a new birth, human beings essentially see human beings themselves, the inner being of human beings. Human beings are then the world for human beings. What is hidden here on earth is revealed in the spiritual world. The entire connection between the soul and the organic nature of the human being, between the activity of the individual organs, in short, everything that is, so to speak, symbolically speaking, within the human skin, is seen by the human being between death and a new birth.

[ 8 ] But now, in our age, it is again the case that human beings do not get to live in the light. Life in the light is actually only granted to them between birth and death. Today, human beings do not get to live in the light between death and a new birth. They are, so to speak, captured by necessity when they pass through death. As free as man feels in his perception here on earth, where he can turn his eyes wherever he wants, can summarize what he perceives in concepts in such a way that he feels his free action in these concepts, so unfree does man feel in this relationship to the world of perception between death and a new birth. He is, as it were, carried away from the world. It is just as if during this time man perceived as he would here if he were, so to speak, hypnotized by every single sense perception, if he were carried away by every single sense perception so that he could not voluntarily detach himself from it.

[ 9 ] This is the development that human beings entered into in the middle of the 15th century. The divine-spiritual worlds have disappeared from the appearance of the earth. In the time between death and a new birth, however, these divine-spiritual worlds captivate him so much that he cannot maintain his independence from them. Only, I said, if man truly develops freedom here, that is, if he commits his whole being to the apparent life, then it is possible for him to carry his own being through the gate of death. But what else is necessary for this can become clear to us if we look at another difference between our view today and the view of earlier times.

[ 10 ] Whether we consider humanity in general or the initiates and mysteries of earlier times, the whole worldview was oriented differently than it is today. If we consider what human beings have been able to recognize since the middle of the fifteenth century through the kind of knowledge that has arisen since then, we find that human beings form ideas about the development of the earth and about the development of their own human species. but such ideas that can point in any satisfactory way to the beginning and end of the earth disappear. One might say that human beings have an overview of a certain line of development. They look back historically, they look back geologically. But when he goes further back, he forms hypotheses. He places the primordial nebula (drawing $. 179, horizontal line in light color) at the beginning, which appears to be a physical structure. From this then develop—that is, it does not develop, but human beings imagine that it develops—the higher beings of the natural kingdoms, plants, animals, and so on. Then, again, man imagines according to today's physical ideas: in the end, earthly existence falls into heat death (drawing with red lines on the right) — again a hypothesis. Man thus sees, as it were, a piece between the beginning and the end. The beginning and the end blur as unsatisfactory structures before the eyes of today's man.

[ 11 ] This was not the case in earlier times. In earlier times, human beings had very precise ideas about the beginning and end of the earth, thanks to the revelation of the divine spirit in the light shining above the earth. We can look to the Old Testament, we can look to other religious teachings of the ancients: In the Old Testament, we find ideas about the beginning of the world that were formed in the way that was possible at that time, so that people could understand their own existence on Earth from these ideas. No one can understand human existence on Earth today from Kant and Laplace's primordial nebula.

[ 12 ] If you take the wonderful cosmogonies of the various pagan peoples, you again have something from which human beings can understand their earthly existence. Humans therefore turned their gaze to the beginning of the Earth and were able to arrive at ideas that encompassed them. What then existed as ideas about the end of the Earth remained in human consciousness for even longer. We still see, for example, in Michelangelo's “Last Judgment” and in other “Last Judgments” up to the present day, ideas about the end of the earth that completely encompass human beings and, however difficult the ideas about guilt and atonement may be, do not destroy them.

[ 13 ] Let us take today's hypothetical idea about the end of the earth: everything has melted into a uniform warmth. The entire human being has melted away. Human beings have no place there. So, in addition to the fact that divine-spiritual being has disappeared from the realm of perception, human beings have lost, in the course of time, those ideas about the beginning and end of the earth within which they can have validity, within which they can see themselves in the cosmos with the beginning and end of the earth.

[ 14 ] What then was history for these people, in whatever form they may have recognized it? History was what moved between the beginning and the end of the earth, what acquired meaning through the ideas of the beginning and the end of the earth. Take any pagan cosmology and you can imagine the historical development of humanity. You go back to times when the earthly emerged from a divine-spiritual web. History has meaning. Even looking forward, after the end of the earth, history has meaning. If the idea of the end of the earth remained more intact in more recent times for pictorial viewing and religious feeling, then the beginning of the earth remained in a certain way for historical consideration, like a straggler, until the most recent times. Even in such enlightened historical works as Rotteck's World History, you can still find the aftereffects of this idea of the beginning of the earth, which gives history a meaning. Even if it is only a shadow over the beginning of the earth in Rotteck's World History, which was written at the beginning of the 19th century, it still gives historical development a meaning. What is significant and peculiar is that at the same time as humans enter a world of appearances, in which external nature appears to them as appearances, history loses its meaning for immediate human knowledge due to the absence of a beginning and an end of the Earth.

[ 15 ] Take this matter completely seriously. Take as your starting point the development of the earth from a primordial nebula, out of which first emerge indeterminate forms, then all beings, which then rise up to the level of human beings, and take as your end point the heat death of the earth, in which everything dies, and in between, what we tell ourselves about Moses, about the ancient Chinese, Indian, Persian, and Egyptian greats, through Greece and Rome, up to our own time, to which we add in our minds what might still come—it all takes place on Earth like an episode without beginning or end. History seems meaningless.

[ 16 ] One only has to realize this once. Nature can be understood, even if not in its innermost depths. It appears to humans as an illusion, as they experience it between birth and death. History becomes meaningless. And people in our time are simply not brave enough to admit that history is meaningless, meaningless because they have forgotten the beginning and end of the earth. People today should actually feel that the historical development of humanity is the greatest mystery of all. They should say to themselves: this historical development is meaningless.

[ 17 ] Some individuals have sensed this. Read what Schopenhauer had to say about the meaninglessness of history from the perspective of Western belief, and you will see that Schopenhauer certainly felt this meaninglessness. The desire must arise to find the meaning of history in another way. From the world that we find sufficient for the knowledge of nature, from the world of appearances, we can form a satisfactory knowledge of nature in the Goethean sense if we renounce hypotheses and remain in phenomenology, that is, in the doctrine of appearances. In natural science, satisfaction can be found if we simply refrain from disturbing hypotheses about the beginning and end of the earth. But then we are, in a sense, enclosed in our earthly cave; we cannot see out. The Kant-Laplace theory and the heat death of the universe block our view of the temporal expanses of the world.

[ 18 ] Basically, this is the situation in which, according to general consciousness, humanity currently lives. Therefore, it faces a certain danger. It cannot really settle into the mere world of phenomena, into the world of appearances. Above all, it cannot settle into this world of appearances with its inner life. It wants to surrender to necessity, to inner necessity, to instincts, drives, and passions. Today, we see little of what arises from the free impulsiveness of pure thinking. But just as much as human beings lack freedom here in life between birth and death, just as much comes upon them with the hypnotic compulsion between death and new birth, with bondage, with necessity in perception. Thus, humans are in danger of passing through the gates of death without being able to take their own essence with them, but instead settling into the world of perception not in something free, but in something that submerges them in coercive relationships, which makes them freeze in the outer world.

[ 19 ] What must strike into the life of humanity toward the future is that the divine-spiritual must appear to human beings in a different way than it appeared to them in ancient times. In ancient times, at the beginning and end of the earth, human beings could conceive of a spiritual within the physical with which they could know themselves to be one, which did not exclude them. But more and more, human beings must take in from the middle of this spiritualized world instead of from the beginning and the end (see drawing, vertical line in the middle). And just as in the Old Testament, at the beginning of the earth, one saw a genesis of human beings within which their existence was secured, just as in pagan cosmogonies one had a development of humanity out of a divine-spiritual existence, so now one has a view of the end of the earth, which has still been preserved, as mentioned, in the ideas about the end of the world, which do not reveal to human beings their own being before themselves.spiritual existence, as one has a view of the end of the earth, which has still been preserved, as I said, in the ideas of the end of the world, which do not take away man's being from himself, so in the newer times, in a correct view of the Mystery of Golgotha, one must find for the middle of the earth's development that in which one again sees the divine and the earthly in each other. Human beings must understand correctly how God passed through human beings with the mystery of Golgotha. Then they will be given what they have lost regarding the beginning and end of the earth. But there is an essential difference between this view of the mystery of Golgotha and the earlier view of the beginning and end of the earth.