Cosmosophy II

GA 208

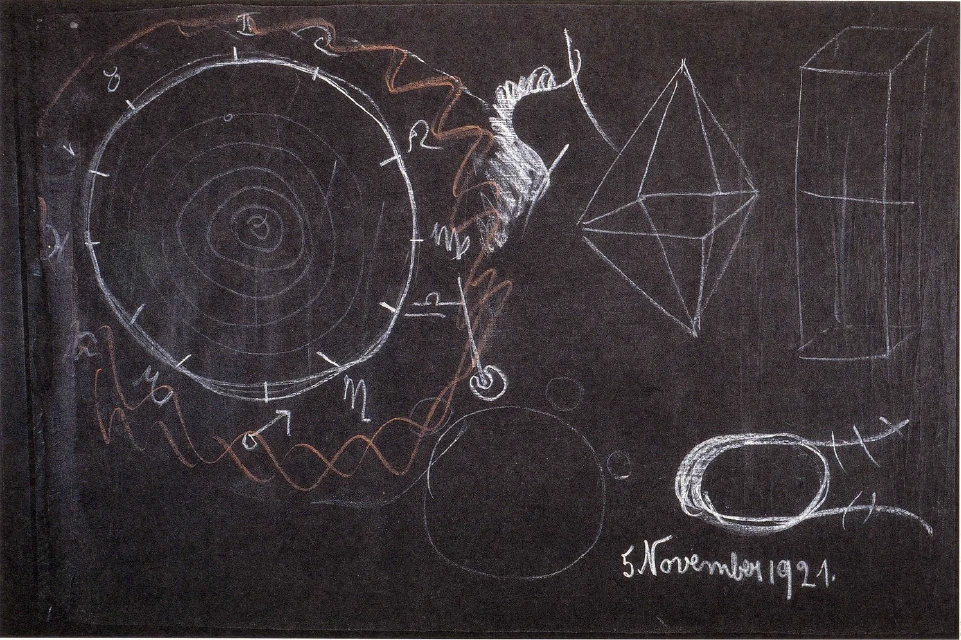

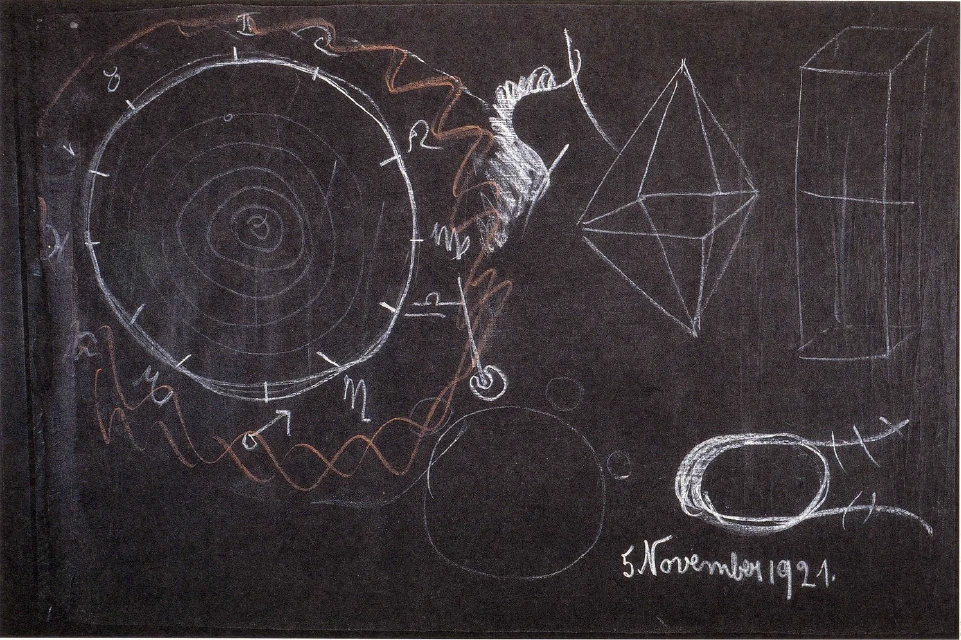

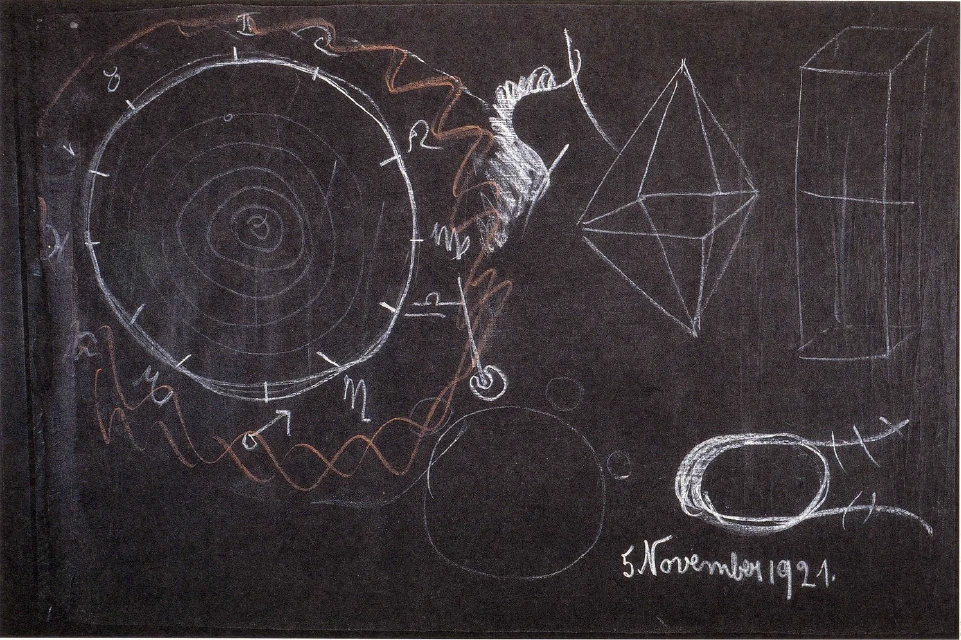

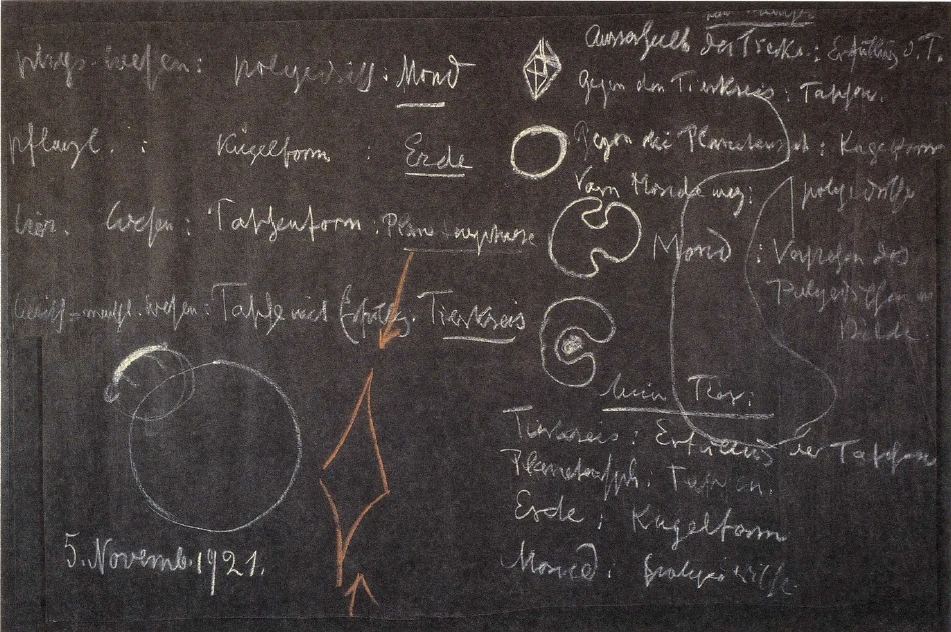

5 November 1921, Dornach

Lecture VIII

We have been considering the human being in relation to the cosmos. To people who do not know anything beyond the present-day way of looking at things it must seem rather absurd to hear of a link being made between the essential nature of the human being and the essential nature of the cosmos, and I am certain that the majority of people will consider this to be quite unscientific. Yet when we think of the spiritual streams of today there is an urgent need to draw attention to exactly the kind of thing we have been considering and to do so quite energetically. For these things may fairly be said to be entirely in line with modern thinking. The problem is, modern thinkers are rejecting them with great vehemence, which is doing untold harm to the life of mind and spirit.

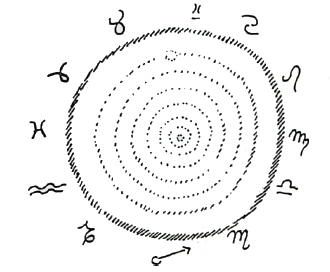

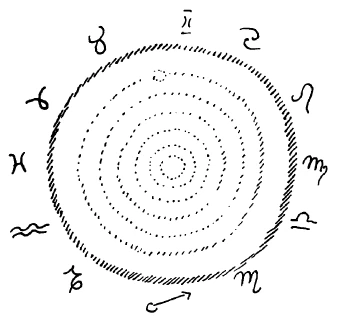

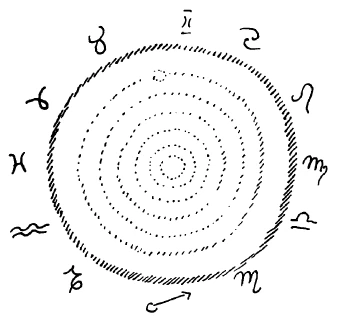

To begin with, we’ll sum up what I have been presenting in recent lectures. We have been considering the human form as the outcome of something the causes of which must be looked for among the fixed stars, and particularly the constellations of the zodiac as their representatives. We found that to understand the human form we must first of all look to the zodiac; its twelve constellations make it possible for us to understand the human form in every detail.

To understand the levels of human life we must look to the planetary system for the elements which will enable us to do so.

We then moved on from understanding the levels of life to understanding the soul principle. There we had to go to the human being himself, to the form he has been given and to that which lives in him. We also looked at the thinking, feeling and will aspects of the inner life in relation to the human form and the levels of life. Yesterday we attempted to look for the element of mind and spirit in the inner life. With the soul principle we move from the cosmic periphery to life on earth as such—that is, if we consider the soul principle during life between birth and death. We are able to approach it by considering its true relationship to the human form and to human life.

Yesterday we found that the spirit, which human beings only experience in images, has to be looked for in the sphere of the soul. If I may put it like this, we are coming down to earth from heaven. To consider the human form we have to go as far as the fixed stars; to consider human life, we need to go to the sphere of the planets; to consider the human soul in its relationships between birth and death, we must first of all descend to earth. Thus the human being becomes a whole for us in his relationship to the cosmos.

Now if we really appreciate all this, we shall be able on the basis of it to draw the borderline between animal and human nature. The way it may be done is as follows. If we consider the principle which can be understood in relation to the zodiac and how it is in humans and in animals, a difference emerges. But to see the whole of it we need to consider how the zodiac, the planetary sphere and the earth, with everything presented in yesterday’s lecture, act on human beings and on animals. Outside the human being the physical world does not take the form it does in the human body. We find it in the forms of the mineral world, a world very different from the human physical body. This is because in the human being the physical principle is clothed in an etheric and an astral principle and in I nature, all of which change the physical principle, adapting it to suit their needs. In the physical world outside the human being we see the physical principle as it presents itself when not imbued with etheric, astral and I nature.

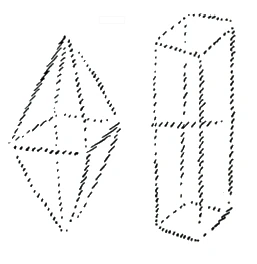

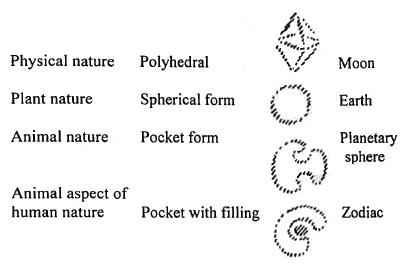

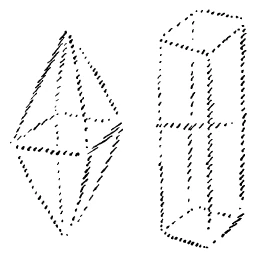

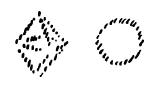

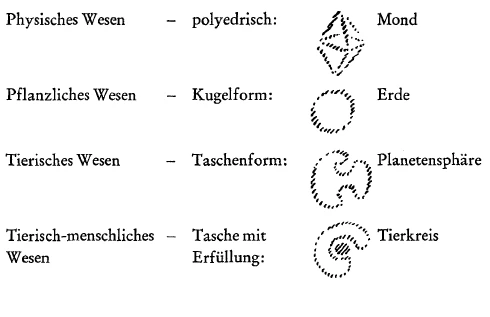

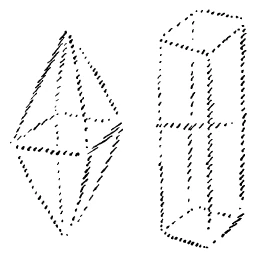

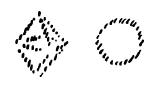

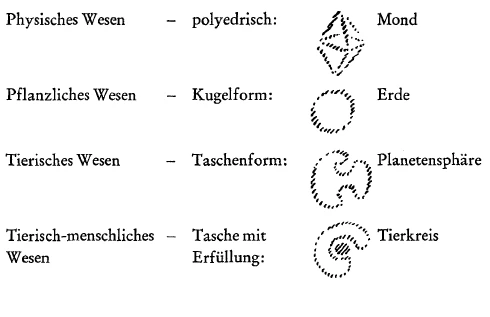

The inherent form principle of the mineral is the crystal, a polyhedral form.

To grasp this form we must first of all consider the physical matter which has developed out of the forces which are active in the mineral sphere. We have to visualize that in an elongated mineral specific forces act in this direction to elongate the mineral (see crystal on the right). The forces acting in this direction (horizontal line in the centre) are perhaps less powerful, or we may say they act to make the mineral more slender in this direction, and so on. In short, in order to talk about minerals at all, we have to visualize these forces being at specific angles to each other, acting in specific directions, irrespective of whether they come from inside or outside. And above all we have to visualize these forces as existing in the universe, at least to the point where they take effect in the sphere of the earth.

Being effective, they must also have an effect on the human physical body, which means it, too, must have the inherent tendency to become polyhedral. It does not actually become polyhedral because it still has its ether body and astral body which do not allow the human being to turn into a cube, octahedron, tetrahedron, icosahedron, and so on. The tendency is there, however, and it would be fair to say: In so far as human beings are physical beings, they tend towards becoming polyhedral. So if you are glad that you do not have to walk around as a cube, a tetrahedron or octahedron, the reason is that the powers of the astral and ether bodies act against the forces—octahedral, cubic, or whatever—inside you.

Now we are not only a physical body but also have an ether body. Through it we are in essence at one with the plant world. Through the physical body we represent the mineral, or physical, world around us, through the ether body the plant world around us.

Plants are also part of the physical world and therefore have the tendency to be polyhedral, but they add to it a tendency to be spherical. Circumstances may occasionally cause minerals to occur in spherical form, but this is not their true form. There has to be scree, or something of that kind, if a mineral is to be spherical.

In plants, every single cell seeks to achieve spherical form; in humans only the head goes a little in that direction. We owe this spherical form essentially to plant nature. The fact that not all plants are spherical is in the first place due to their having to fight against polyhedral form, which has its own outcome, and secondly to the plant form having also to fight against a cosmic, astral principle. You will remember from earlier lectures that a cosmic, astral principle presses down on the plant from above. All this modifies the spherical form. You also get spheres imposed on spheres. But the essential plant form is a sphere.

Seeking to achieve spherical form the plant assumes the form of the earth itself. As you know, the earth is a sphere in the cosmos, and so is every drop of water. Only the mineral parts of the earth are polyhedral. As a whole, the earth is spherical. The plant, or the life principle, therefore seeks to attain to the spherical form and in doing so is really trying to recreate the form of the earth.

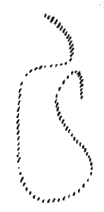

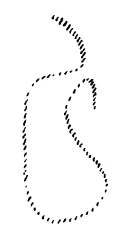

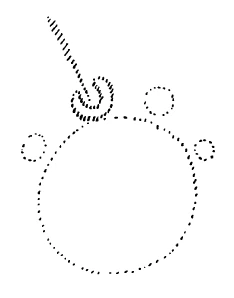

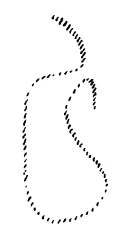

Let us now go higher and consider what the human being is because of the astral body. Here the human being is something representing the animal nature found in the animal world. In the physical, mineral nature of man we look for the polyhedral form, in human plant nature for the spherical form which reflects the planet earth (Fig. 28). Animal nature can be understood if we do not stop at the spherical form but add something to this form. We have to add pockets, or sacs, to the spherical form, like this:

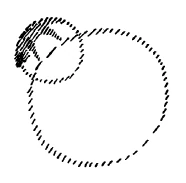

It is in the nature of the animal form that a pocket element breaks up the sphere, with pocket-like inroads made everywhere. Consider your eye sockets—two pockets coming in from the outside. Consider your nostrils—two pockets. And finally consider the whole of your digestive tract from mouth to stomach. It is possible to arrive at this if you let a pocket develop, starting at the mouth, which goes all the way down.

You always get the pocket form added to the spherical form when the transition has to be made from plant to animal form.

We can come to understand the pocket form if we lift our eyes from the earth to the planetary system. You will find it easy to see that the earth seeks to give its own form to everything that lives on it. But a planet acting from outside counteracts the earth forces and makes pockets in the spherical form given by the earth. The different creatures of the animal kingdom are provided with such sacs, or pockets, in a wide variety of ways. Consider the planets and the different ways in which they act. Saturn makes a different kind of inroad than Jupiter or Mars. The lion is equipped with a different kind of inner sac-nature for the simple reason that the planetary influences on it are different from those on the camel, for instance. So in this case we have sacs being formed.

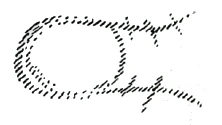

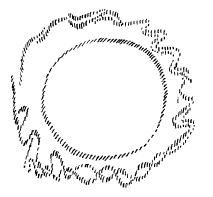

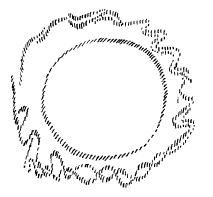

But in animals—and this means above all in higher animals, for the situation is different with the lower animals—and also in human beings something arises which does not merely come from the planetary realm, so that we are able to say: The essence of both animal and human nature is to have more than just the pocket form. This would be the case if there were only the planets and if the firmament of fixed stars had no influence. Something is added to the pocket form. In many situations people are satisfied when they have not just a pocket but something in it. And it is indeed the case that it is the essence of the animal aspect of human nature to have a pocket with something to fill it. So we have a spherical form with a pocket and the pocket is filled.

You only need to look at the sense organs, the eye. You have first of all a pocket, which is the eye socket, and then something to fill it. And this fulfilment,25Steiner is using a slightly unusual term here, which usually translated as “fulfilment”. For the translation I have largely used terms like “filling”, “that which fills them” or “which are filled”, but I felt the note should be sounded just once in this passage. which occurs particularly in the sense organs, relates to the zodiac just as the pocket form relates to the planetary sphere. Human beings have the most complete animal organization in this respect, which is also why they have twelve pockets with their fillings, though this is disguised in all kinds of ways. This is why I had to list twelve sense organs in my Anthroposophy.26Steiner R. Anthroposophy (A Fragment) (GA 45). Tr. C. E. Creeger. New York: Anthroposophic Press 1996.

We can now go back and ask: Which cosmic principle relates to the polyhedral quality? You see, if we consider the earth, it has the life form if seen as a whole, and if it consisted entirely of water it would only show this form. But all kinds of disruptions enter into the water. You can observe these disruptions in the tides, for instance. There the water is given configuration. Next, let us look back to earlier stages of configuration for the liquid earth, when it first began to develop solid elements. It is still possible to see today that the tides are connected with the moon, and everything polyhedral which becomes part of the configuration of the earth relates to the moon.

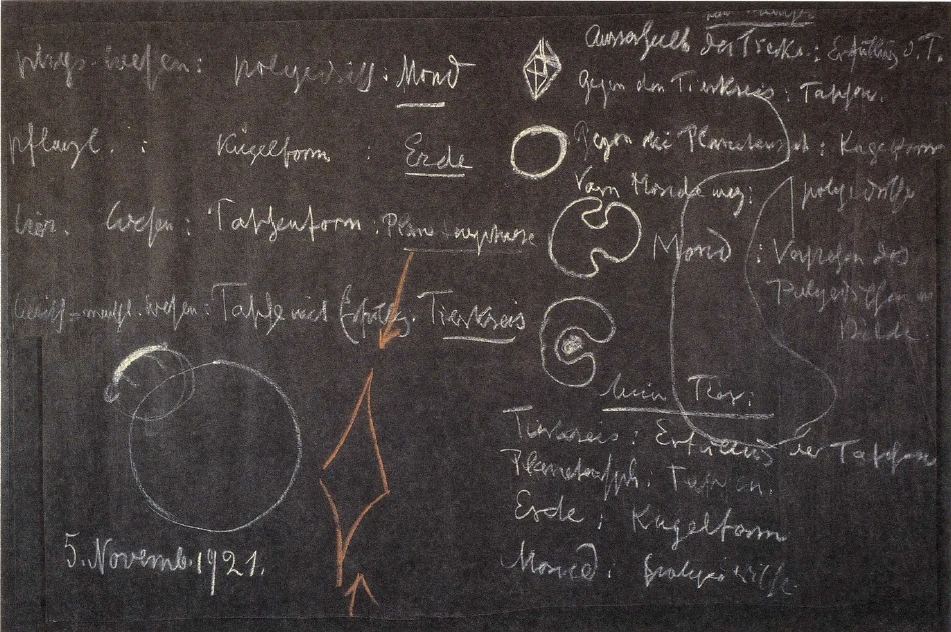

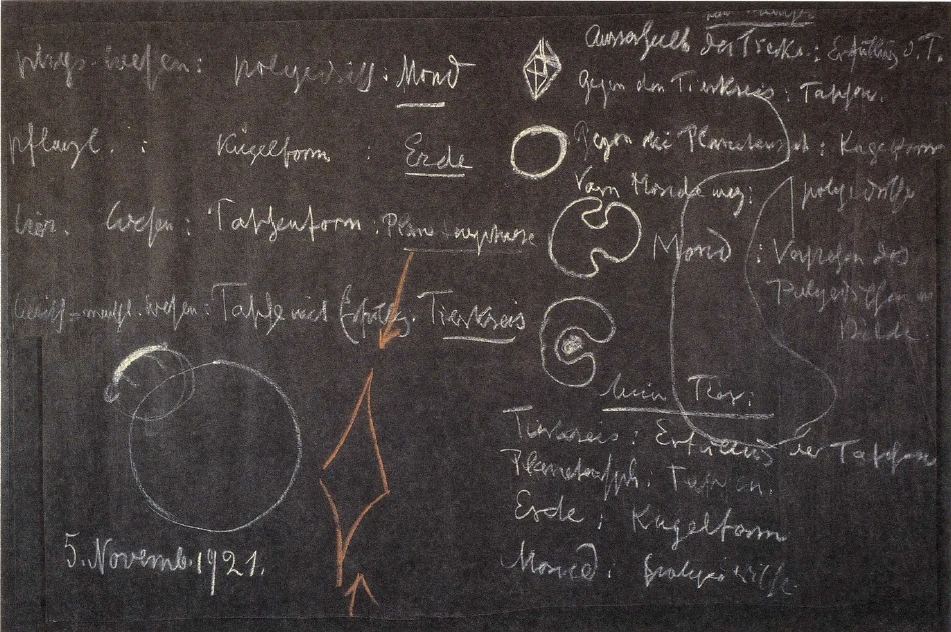

Thus we are able to say: The polyhedral or physical nature of human beings is connected with the moon, their vegetable or etheric nature with the earth, their astral nature, which would produce the pocket form, with the planetary sphere, and the filling of the pocket with the zodiac.

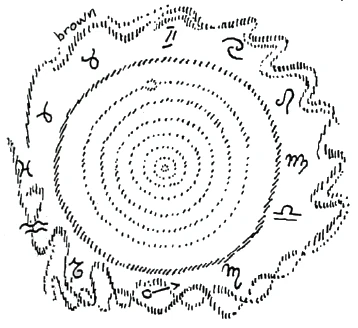

What I have written on the board applies in a different way to humans than it does to animals. You see, with animals it is truly the case that the heavens only have significance as far as the sphere of the zodiac, meaning everything which lies within it. Anything which lies outside it holds no significance for the animal. Ancient wisdom was therefore quite right in calling it the “zodiac”,27From the Greek “ho ton [long “o”] zodion [long “o”s] kyklos” = the circle of the sculptured figures of animals. for it was also able to say: Everything outside the zodiac in the universe might just as well not exist, for the animals on earth would still be exactly as they are. Only what lies below the zodiac, together with the earth and the moon, has significance for animals. What lies beyond the zodiac has, however, significance for human beings, for it influences the filling of the pockets.

For the animal we have to say: Everything which lies inside the zodiac influences the filling of the pockets. We therefore have to go into the zodiac itself and then we are able to explain how the filling of the pockets presents itself. With humans, we have to go beyond the zodiac (Fig. 34, brown) if we want to explain what goes on in the sphere of the senses, for example. In this respect, human beings go beyond the zodiac, animals do not.

It is also the case that in animals, the planetary sphere as such has a direct influence on the pockets. As the pockets continue inwards, to form the organs, animal organs are perfect reflections of the principles relating to the planetary sphere. Human beings again go a little further and we are able to say that in human beings, the region closer to the zodiac influences the pockets.

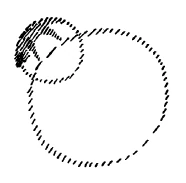

In animals, the earth has a direct effect on everything tending to assume spherical form. This is not possible in human beings, who otherwise would be animals, with a tendency to be spherical. In a sense, animals tend towards the spherical form. Here (Fig. 35) we have the backbone, then the legs. Animals are however prevented from becoming a complete sphere.

The back bone forms part of the sphere. Human beings tend to move away from the earth principle, just as they have moved away from the zodiac, and from the planetary sphere, towards the zodiac. We are able to say that the human spherical form is created by moving towards the planetary sphere. Human beings walk upright, however, and seek to go beyond mere adaptation to earthly principles.

With reference to the polyhedral element we have to say that the moon gives it directly to the animal. Human beings also seek to move out of the influences of the moon, “away from the moon”, as we might say, to receive their polyhedral element from a region between earth and moon. This means, however, that the moon still has an influence. In the fifth place, therefore, we must look to see what the moon, which in animals brings about the polyhedral element, is doing in human beings. It brings about a polyhedral element in humans, but as an image. Animals have the polyhedral element in their configuration; humans lift it out of the organism. Mathematical and geometrical ideas become image, taken out of the living physical body. Today, people primarily visualize and want to understand things in mathematical terms because they are able, under the moon’s influence, to lift their own polyhedral element out of the body, so that it enters into the conscious mind. We are thus able to say that thanks to the moon, we are able to understand the polyhedral element in images.

| Beyond the zodiac | Filling of pockets |

| Towards the zodiac | Pockets |

| Towards the planetary sphere | Spherical form |

| Away from the moon | Polyhedral |

| Moon | Understanding the polyhedral in images |

| Zodiac | Filling of pockets |

| Planetary sphere | Pockets |

| Earth | Spherical form |

| Moon | Polyhedral |

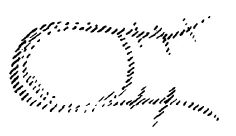

So you see how by considering the human being’s relationship to the cosmos we not only arrive at the outer form we have been considering in recent years but also understand how human beings gain inner form and structure. We see how they create their nasal cavities, or the stomach, as sacs or pockets. If we were to take this further we would understand the organs altogether and how they take internal form out of the whole cosmos. If we want to understand the human being we must always draw on the cosmos. We have to do so when we ask why we have an organ such as the lung, for instance. Essentially the lung can only be understood if we grasp that initially, in the embryo, a kind of sac forms, going inwards, with physical matter forming a lining. The sac-like form then tears itself free on the outside, and the organ closes itself off as an internal organ. We come to see why there is a lung, or any other organ, inside the human being if we perceive this organ to have originated from a sac, with the inner end of the sac thickening and due to other circumstances taking on a particular configuration. An organ such as the stomach can be seen as a sac extending inwards. An organ such as the lung, the heart or the kidney also starts as a sac, but it thickens here (Fig. 36), tears off here, and you have a closed-off internal organ.

Yet even with these closed-off organs—if we ask ourselves why they are in a particular place in the human organism, or why they have a particular shape or internal structure, we always have to consider the human being in relationship to the whole universe.

If a modern scientist were to hear of anthroposophists wanting to explain the lung, heart, liver, and so on out of the cosmos, he'd say we were quite mad. Members of the medical profession in particular would call this madness. They should not do so, however. It is up to them to realize that anthroposophy is actually trying to meet them half-way as they pursue their course clinging firmly to their accustomed blinkers. Let me give you a small example to prove this.

I have here before me a booklet written by the physician, medical scientist and biologist Moriz Benedikt in 1894.28Benedikt, Moriz (1835–1920), Hypnotismus und Suggestion, Leipzig & Wien 1894. I tend to quote this gentleman quite often, though I actually do not much like doing so, for apart from anything else, he shows himself to be terribly conceited, practically on every page he writes. He is also quite inflexible as a Kantian. There is, of course, the mitigating circumstance that he has made up his own Kantian ideas to suit himself, presenting them with some inflexibility. The man is extraordinarily gifted, however. He is not interested in anthroposophical ideas or anything of the kind, but it is fair to say that simply by being involved in medicine and science he has arrived at a reasonably unbiased view as to the value of his scientific outlook. He cannot get out of it; yet in a strange way he peers out. The others are also caught up in their science as if in a prison, but they do not even look at anything outside. He keeps looking at the outside world, and this allows him to arrive at extraordinarily interesting conclusions. His vanity has made him a great many enemies, and he will therefore sometimes say things about enemies who show themselves with their masks off—generally these people are “friends”, maintaining closed ranks. His colleagues have tended to put him down, and he therefore says things about them that are highly typical. He knows nothing about anthroposophy, of course, but still, if we consider anthroposophy in terms of its qualities it would be fair to say that, qualitatively speaking, he is an anti-anthroposophist. However, in the booklet I have before me he says:

The self-righteous ignore or deny anything that does not fit in with their point of view, persecuting not only the teaching, but even more bitterly the teachers. Self-righteousness is a peculiar kettle of fish. It smells sweet to the self-righteous but gives off a sharp, biting odour for others. Self-righteousness is by its very nature closely bound up with the scholars’ trade, so much so that although I hate the self-righteous I often ask myself: How often and in how many instances have you yourself been self-righteous? I’d be most grateful to anyone who would give me an exact answer to the question.

For my part, I am convinced that far from being grateful he would complain like anything if we were to make him aware of his own self-righteousness. Yet in his own peculiar way he has a particularly good eye for self-righteousness in others.

He goes on to speak of his own history, wanting to show that he has become a different kind of medical man from his colleagues. He writes:

Two severe strokes of destiny spelled disaster for my own development and also for the scientific position relative to the subject under discussion.

You’ll immediately be aware of a nice touch of vanity in what follows:

In the first place, I studied mathematics and mechanics before joining the medical profession. In those days we had an eminent mathematician at Vienna University, Professor von Ettingshausen,29Ettingshausen, Andreas, Freiherr von (1796–1857), mathematician and physicist. who presented the most difficult problems in the mathematics of physics and caught our interest. I heard him develop the theories of Cauchy30Cauchy, August Louis (1789–1857), French mathematician. and Poisson.31Poisson, Siméon Denis (1781–1840), French mathematician and physicist. Petzval32Petzval, Joseph (1807–1891), Austrian mathematician and physicist. taught us to express the problems of mechanics in mathematical formulas. It will be easy to show, however, how disastrous mathematical thinking is for a member of the medical profession, and above all a clinician.

Well, we shall see why it is disastrous, especially if such a person knows something about medicine. Professor Benedikt goes on with his story. You would have thought it to be a good stroke of destiny to be a mathematician, but he calls it a bad one, because it taught him to think. Other clinicians were apparently unable to think, and they hated him for having studied mathematics, for it meant he knew more than they did.

The second stroke of destiny to come in the days of my youth was that I became a student of Skoda.33Skoda, Joseph (1805–1881), physician; together with Rokitansky established the high reputation of the Viennese School in its heyday. I am still attached to his teachings today. He was the Kant of medical philosophy, and his mind rose to sublime heights not in books but in the discussion of diagnoses, indications for treatment, and particularly in postmortem reviews. Skoda had been a mathematician when young

—clearly another stroke of destiny!—

and had brought the most important and fundamental scientific thinking to medicine, though unfortunately only in isolated instances; the important insight I received from Skoda, having already been firmly convinced of it through my mathematical studies, is that in establishing scientific proof, we must be aware not only of what we know but also of what we do not know.

Benedikt had thus also studied under Skoda. The idea was that when using modern scientific methods—for this was the subject under discussion—we should be aware not only of what we know but also of what we do not yet know. Benedikt really did represent this principle with some degree of fanaticism in numerous treatises. He goes on to say:

This basic rule of medicine is not known to the majority of biologists, and indeed is incomprehensible to them. Some years ago, for example, I sent a manuscript in a foreign language to an anatomist, asking him to correct the language. When it came to the above statement, he wrote in the margin that he did not understand the meaning of it.

Benedikt says here that we should also consider what we do not know, and he wanted the other individual to translate the statement into proper French. The anatomist had written, however, to say he did not understand it.

When I showed the comment written in the margin to a professor at the technical university he smiled. The statement is perfectly clear to anyone involved in the exact sciences.

The man smiled because he understood mathematical thinking; it amused him that members of the medical profession thought they could ignore the things they did not know. An engineer must know what he does not know, for he has studied mathematics.

When I told a famous medical expert in Vienna of the odd reaction from my medical colleague, he said rather naively: Well, how are we to know the unknown?—This historical anecdote casts a sharp light on the method of thinking still prevalent in modern medicine and on the colossal errors made day by day and hour by hour in the medical literature.

These are the words of a medical man! But we now come to a most important point. Moriz Benedikt tells us what happens in medical science, where no account is taken of the unknown:

The problems generally arise with reference to the biology of an organ, its function, for instance. The conditions on which the function is based are partly unknown and still have to be found.

He goes on to give an example:

The liver, for instance, secretes bile. The reason for this secretory process lies mainly in the specific biochemical properties of the cells.

Let us ignore the fact that he is referring to the biochemical properties of cells, which does not really make sense. We are taking the point of view he takes in speaking of the liver.

The reason must be found as to how these differentiated properties evolve;...

He wants to find the reason why the liver is different from other organs; he intends to consider the unknown. It is known that the liver secretes bile. But now we come to the unknown, and mark you well, he produces a considerable list:

The reason must be found as to how these differential properties evolve; how the organ develops from its elements; how it comes to be in its particular place; why it relates to surrounding organs in a specific way; how with the aid of specific haemodynamic forces and haemostatic conditions it maintains the specificity of its cells; how with the aid of the central and centrifugal nervous system it is stimulated to function at the right time and with the necessary intensity; what the conditions are for nutrition in general, to maintain function and timing; which conditions impair function, causing short-term or permanent disorders, etc.

All this is not known and has to be considered. Moriz Benedikt then continues:

In science, these questions come up one after the other over long periods of time.

Just the questions come up, therefore!

The literature, on the other hand, considers only what is known at any time, without enquiring into the unknown, and behaves as if the basic problem had already been fully solved.

That is, makes no mention of the unknown. People like Moriz Benedikt are at least able to list all these unknown elements.

This is why only a small part of the theories which prevail at any given time is true, and they contain a colossal percentage of new and inherited errors which will continue on through generations as original sin.

What is this medical man really saying? He says: We have a medical literature but it only deals with the known. Yet the unknown keeps coming up after long intervals of time. What does Benedikt want? He wants people to be aware of what they do not know. What would happen in the case of the liver, for instance? A member of the medical profession taking the opposite view of Benedikt who gave a description of the liver would try to discover the biochemical properties of liver cells and present the fact that the liver secretes bile. He would be satisfied with this, for he does not talk about anything that is not known. Benedikt would say: Alright, the liver secretes bile; this is due to the biochemical constitution of the liver cells. But as a conscientious scientist I must also say everything I do not know about the liver and the bile. He would therefore write in his book:

This we know, but we do not know how the liver comes to be in that particular place; how the statics and dynamics of the blood, or rather the circulation, affect the liver; how the nervous system relates to the liver, both the system as a whole and the individual nerves; and how the liver contributes to nutrition. Benedikt’s books would therefore be different from those of other authors. As a scientist he would in this respect be extremely modest.

But he says this question as to the unknown comes up in the course of centuries; yet because of the way the questions are put, if we go down to fundamentals, then even taking Benedikt’s point of view, we could go on till Judgement Day, always putting down what is known and then what is unknown and the many questions that arise. Benedikt’s books would only differ from those of other authors in that they also list what is not known. Yet he would never accept that something we do not know has to be taken out into the cosmos, that it will continue to be unknown until we explain it out of the cosmos.

You see, a rational medical practitioner here says, speaking in the terms of his discipline, that we cannot explain the human being with the means at our disposal; all we can do is to list the things we do not know. Unfortunately he persists in his refusal to consider something which does provide answers to these questions, questions he says concern the unknown, and of course the answers can only be provided slowly and gradually.

Thus the questions are there in ordinary science. Anthroposophy offers the answers to these questions. This is the truth. It is something we should stress over and over again, quite emphatically.

Moriz Benedikt believes that the bad habits to be found in his particular science are due to the fact that people know nothing of the unknown, offering to humanity what they know on the basis of facts established in the sense-perceptible world only. He gets quite sarcastic as he goes on to say: This scientific ineptitude flourishes today ... not his ineptitude, but that of his colleagues! as much as it did a thousand years ago; indeed it is worse than ever, since production has become so much faster.

He means to say that in earlier times it was not possible to publish one’s misdemeanours so quickly.

Every short-lived notion or undertaking is published so quickly nowadays that medical journalism only needs a “Hot Wire column”, and perhaps we may see the day when telephone booths are set up just to make sure that scientific “ideas" do not lie fallow even for nine minutes.

Publication took more years in the past than it takes hours today.

Oh, and Moriz Benedikt also knows what he thinks of the public, who listen to the medical profession and swear by them! He puts it simply in the following rhyme:

Miller, Brown, Smith and Read join in every heinous deed.

He then starts to reproach his colleagues again—the heinous deeds are theirs, of course—saying:

These unsatisfactory conditions in biology will not improve until a major reform in education starts with the teachers. Anyone unable to show that he has made a serious study of mathematics and mechanics is not fit to be a thinker or a scientist, let alone a teacher. Individual genius has always achieved much; it limps, however, and will go on limping until it has learned to walk first in the school of mathematics.

Not everyone who wants to listen to something sensible will need mathematics, of course. But to work with genuine science one does need to be trained in mathematical thinking. This is why Plato—Moriz Benedikt is very rude about him, by the way—wrote on the doors to his academy: Admittance only for those trained in mathematics. This does not prevent present-day philosophers, who have not been trained in mathematics, to write about Plato, of course. And we may truly say: Most of the people who write about Plato today would not have gained admittance to his academy if it still existed. You will see, from what I have read to you from Moriz Benedikt’s booklet, how modern scientific minds view something they themselves really ought to desire, and how someone who, whilst not an anthroposophist but a rather vain individual who has got into some conflict with his colleagues, has nevertheless had some faint notion of the harm that is done—how such a person judges the situation. Let us be very clear about this: The situation we have today is exactly as an unbiased observer with insight gained in anthroposophy is compelled to describe it. The proofs are to be found everywhere in the world of modern exoteric science, you must merely want to look for them.

What we must do, however, is to learn how to consider the human being in a way which physicists would consider perfectly sensible. I have already given you the analogy: If you study a compass needle and insist on saying it assumes a particular direction out of its own inherent powers, you will never understand why there are north-and south-pointing forces in the compass needle. We must understand that the whole earth has two forces, that the poles of the two forces are determined from outside. In the same way it is utterly wrong to put a human being on the dissecting table and decide to explain the whole of the human being’s nature on the basis of what lies inside the skin. We need the whole world to understand the outer and inner aspects of the human being.

Neunzehnter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Wir haben in der letzten Zeit Betrachtungen angestellt über den Menschen und seinen Zusammenhang mit dem Kosmos. Es erscheint denjenigen, die nur in der heutigen Weltauffassung drinnenstehen, gegenwärtig noch als etwas, man möchte sagen, ziemlich Absurdes, wenn in einer solchen Art das Wesen des Menschen angeknüpft wird an das Wesen des Kosmos, und man wird wohl in weitesten Kreisen heute ein solches Anknüpfen nicht für wissenschaftlich halten. Dennoch, es ist gegenüber den Geistesströmungen der Gegenwart heute schon dringend notwendig, gerade auf solche Dinge, wie wir sie jetzt in diesen Betrachtungen vor uns gehabt haben, mit aller Energie hinzuweisen. Denn man kann sagen: Diese Dinge liegen durchaus auf dem Wege des heutigen Denkens. Nur werden sie von diesem heutigen Denken zu gleicher Zeit mit aller Heftigkeit zurückgewiesen. Dadurch aber wird dem Geistesleben der Menschheit unsäglicher Schaden zugefügt.

[ 2 ] Wir wollen uns zunächst einmal eine Art Zusammenfassung bilden von demjenigen, was ich in der letzten Zeit hier vorgebracht habe. Wir haben ja die Form des Menschen angesehen als ein Ergebnis dessen, wofür die Ursachen gesucht werden müssen im Fixsternhimmel, namentlich in seinem Repräsentanten, in dem Tierkreis. Wir haben also gesehen: Nach dem Tierkreis als dem Repräsentanten des Fixsternhimmels müssen wir zunächst blicken, wenn wir des Menschen Form, For Tafeli3 mung, Gestaltung verstehen wollen. Da haben wir also den zwölfgliedrigen Tierkreis und finden, indem wir diesen zwölfgliedrigen Tier menschliche Form bis in ihre Einzelheiten hinein zu verstehen.

[ 3 ] Wenn wir dann die Lebensstufen des Menschen verstehen wollen, dann müssen wir zu dem Planetensystem sehen und finden in dem Planetensystem die Elemente zum Verständnis der menschlichen Lebensstufen.

[ 4 ] Wir haben dann unseren Weg genommen von dem Verständnis der Lebensstufen zu dem Verständnis des Seelischen. Da mußten wir aber schon an den Menschen selbst herantreten, an das, was in ihm gestaltet ist, an das, was in ihm lebt. Und wir haben dann versucht, das Seelische nach dem Vorstellen, Fühlen und Wollen zu finden in der Gestalt des Menschen und in den Lebensstufen. Und gestern haben wir ja auch versucht, das Geistige des Menschen wiederum im Seelischen zu finden.

[ 5 ] Nun kommen wir also mit dem Seelischen, das wir betrachten, ich möchte sagen, von dem Umkreis der Welt herein ins eigentliche irdische Leben, wenn wir nämlich das Seelische betrachten in dem Leben des Menschen zwischen Geburt und Tod. Wir können es ja betrachten, wenn wir es in seinem wahren Verhältnis zu der menschlichen Gestalt und zu dem menschlichen Leben ins Auge fassen.

[ 6 ] Wiederum den Geist, von dem wir gestern gesehen haben, daß ihn der Mensch ja eigentlich nur bildhaft erlebt, wir müssen ihn im Seelischen suchen. Wir kommen da, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, aus den Himmeln auf die Erde herunter. Wenn wir die Form des Menschen betrachten, müssen wir bis an die Fixsterne gehen; wenn wir das Leben des Menschen betrachten, müssen wir bis an die Planetensphäre gehen; wenn wir die Seele des Menschen in ihren Verhältnissen zwischen Geburt und Tod betrachten, müssen wir zum Irdischen zunächst heruntersteigen. Es wird für uns in dieser Betrachtung ein Ganzes aus dem Menschen in seinem Zusammenhang mit dem Kosmos.

[ 7 ] Nun, wenn wir diesen Tatbestand gehörig würdigen, dann sind wir auch imstande, aus ihm heraus die Grenzlinie zu ziehen zwischen dem Tierischen und dem Menschlichen. Und das kann nämlich in der folgenden Weise geschehen. Betrachten wir zunächst das, wofür wir uns Verständnis durch den Tierkreis erringen können, betrachten wir das beim Menschen und beim Tiere, so stellt es sich uns eigentlich in einer verschiedenartigen Weise dar. Aber wir müssen, damit wir diesen ganzen Zusammenhang erfassen können, ausgehen davon, wie diese verschiedenen Elemente: Tierkreis, Planetensphäre, die Erde mit alldem, was wir auch gestern betrachteten, auf den Menschen und auf das Tier wirken.

[ 8 ] Wir haben ja im Menschen zunächst seinen physischen Leib. Dieser physische Leib des Menschen, er tritt uns ja nicht in derjenigen Gestalt entgegen, die wir sonst außerhalb des Menschen als die physische kennen. Das Physische tritt uns außerhalb des Menschen im Mineralreich und seinen Gestaltungen entgegen. Was uns im Mineralreich und seinen Gestaltungen entgegentritt, ist ja allerdings sehr unähnlich dem physischen Leib des Menschen. Aber es ist nur deshalb unähnlich dem physischen Leib des Menschen, weil beim Menschen das Physische eingekleidet ist in Ätherisches, Astralisches und das Ich-Wesen, die alle das Physische verändern, die alle das Physische sich anpassen, während im äußeren Physischen uns dieses Physische ohne die Durchdringung mit Ätherischem, mit Astralischem, mit dem Ich-Wesen im Mineralreiche entgegentritt.

[ 9 ] Wenn wir die ureigene Gestalt des Mineralischen ins Auge fassen, so ist sie die Kristallgestalt, die polyedrische Gestalt (siehe Zeichnung); oben halbrechts irgendwie polyedrisch tritt uns das Mineral entgegen. Diese polyedrische Gestalt, die uns bei dem einen Mineral in der einen Form, bei dem anderen Mineral in einer anderen Form entgegentritt, die können wir nicht anders begreifen, als wenn wir zunächst auf das Materielle sehen, das sich aus den Kräften heraus gebildet hat, die eben innerhalb des Raumes des Minerals tätig sind. Wir müssen uns vorstellen: Wenn wir irgendein langgestrecktes Mineral haben, dann sind die Kräfte, welche in dieser Richtung wirken (Zeichnung rechts), eben dazu ge- Tafel 13 eignet, das Mineral nach der Länge zu ziehen. Die Kräfte, welche nach °P "ht dieser Richtung wirken (rechts, horizontaler Strich in der Mitte), entfalten dann vielleicht eine geringere Stärke — oder wie wir das dann ausdrücken wollen -, die das Mineral nach dieser Richtung hin schmäler machen und so fort. Kurz, wir müssen uns, damit wir überhaupt von den Mineralien sprechen können, gleichgültig ob diese Kräfte von außen hereinwirken oder von innen heraus, wir müssen uns vorstellen, daß diese Kräfte in Winkeln zueinander stehen, in gewissen Richtungen wirken, und wir müssen uns vor allen Dingen vorstellen, daß diese Kräfte eben da sind im Weltenall, wenigstens daß sie wirksam sind innerhalb des Erdenbereiches.

[ 10 ] Dann aber, wenn sie wirksam sind, dann müssen sie auch auf den physischen Leib des Menschen wirken, und der physische Leib des Menschen muß in sich die Tendenz haben, polyedrisch zu werden. Er wird nur nicht in Wirklichkeit polyedrisch, weil er noch seinen Ätherleib, seinen astralischen Leib hat, die den Menschen nicht dazu kommen lassen, ein Würfel oder ein Oktaeder oder ein Tetraeder oder Ikosaeder zu werden und so weiter. Aber die Tendenz ist im Menschen, so etwas zu werden, so daß wir schon sagen können: Insofern der Mensch ein physisches Wesen ist, strebt er darnach, polyedrisch zu werden. Wenn Sie froh sind, daß Sie nicht als Würfel herumwandern oder als Tetraeder oder als Oktaeder, so rührt das eben davon her, daß gegen die oktaedrischen oder die Würfelkräfte, die in Ihnen sind, die anderen Kräfte, die des Ätherleibs, Astralleibs wirken.

[ 11 ] Nun ist aber der Mensch eben nicht bloß ein physischer Leib, sondern er trägt in sich seinen Ätherleib. Was er durch seinen Ätherleib ist, das macht ihn wiederum als ein Wesen eins mit der Pflanzenwelt. So wie er durch seinen physischen Leib gewissermaßen die Umwelt repräsentiert, insofern diese mineralisch-physisch ist, so repräsentiert er durch das, was er durch seinen Ätherleib ist, die Umwelt, insofern diese pflanzlich ist.

[ 12 ] Die Pflanze hat natürlich deshalb, weil sie auch ins Physische eingeschaltet ist, schon die Tendenz, polyedrisch zu sein, aber sie bringt zu dieser Tendenz, polyedrisch zu sein, noch eine andere dazu, nämlich diese: kugelig zu sein. Das Mineral kann ja durch allerlei Vorgänge auch einmal in Kugelform auftreten, aber die Kugelform ist ihm nicht eigentlich eigen. Es muß schon irgendein Gerölle oder so etwas sein, wenn es kugelförmig auftreten soll. Seine ureigene Gestalt ist die polyedrische. Aber bei der Pflanze haben wir die Kugelform, und jede einzelne Zelle der Pflanze will sich eigentlich kugelig gestalten. Dieses Streben nach der Kugelform — der Mensch macht es ein wenig erst in seinem Haupte mit - ist also dem Pflanzlichen eigen. Also demjenigen, was das pflanzliche Wesen ist, dem verdankt auch der Mensch die Kugelform. Daß die Pflanzen nicht alle Kugeln sind, das verdanken sie dem Umstande, daß erstens in ihnen die Kugelform kämpft gegen die polyedrische Form, und dadurch ein Resultierendes herauskommt, aber es kämpft auch die Pflanzenform gegen ein Kosmisch-Astralisches. Sie wissen ja aus früheren Vorträgen, daß oben ein KosmischAstralisches auf die Pflanze drückt. Dadurch wird die Kugelform modifiziert. Es lagern sich auch Kugeln übereinander. Aber die Urgestalt des Pflanzlichen, die ist eigentlich das Kugelige.

[ 13 ] Damit aber nimmt die Pflanze, indem sie nach der Kugelform strebt, die Form der Erde selber an. Die Form der Erde nimmt die Pflanze an. Die Erde, sie ist ja, wie Sie wissen, im Kosmos kugelförmig gestaltet. Kugelförmig ist auch jeder Wassertropfen gestaltet. Nur die Teile der Erde, ihre mineralischen Teile, sind polyedrisch gestaltet. Die ganze Erde ist im Kosmos kugelig gestaltet. So daß wir sagen können: Die Kugelform hat die Pflanze gemeinschaftlich mit der Erde selbst. So daß die Pflanze oder das Lebendige nach der Kugelform strebt und eigentlich nachzubilden sucht in der Kugelform dasjenige, was die Erde als Form hat.

[ 14 ] Gehen wir jetzt aber zu dem herauf, was der Mensch durch seinen astralischen Leib ist. Da ist er etwas, wodurch er repräsentiert, was in der tierischen Welt vorhanden ist, das tierische Wesen. Wenn wir also die polyedrische Form suchen beim physischen Wesen, beim mineralischen Wesen, so finden wir beim pflanzlichen die der Erde nachgebildete Kugelform (siehe Zeichnung).

[ 15 ] Nun, das tierische Wesen wird uns verständlich, wenn wir nicht bei der Kugelform stehenbleiben, sondern wenn wir zu etwas anderem vorschreiten, wenn wir also in der Gestaltung zu der kugeligen Form nun etwas hinzufügen. Was ist das, was wir zu der kugeligen Form dazufügen müssen? Das ist die Taschenform, ich könnte auch sagen: Sack-form, die Tasche. Nämlich das Tierische zeigt die Eigentümlichkeit, daß es die Kugelform überall durchbricht durch das Taschige. Es bilden sich überall in der Kugel taschenförmige Einbuchtungen. Das ist das Wesen der tierischen Bildung, daß sich von außen nach innen Taschen einsacken. Betrachten Sie ihre Augenhöhlen — zwei Taschen, die von außen nach innen gehen. Betrachten Sie ihre Nasenhöhlen: zwei Taschen. Betrachten Sie schließlich den ganzen Verdauungsapparat, vom Mund angefangen bis in den Magen hinein: Sie können ihn bekommen, wenn Sie vom Munde ausgehen lassen eine Tasche, die bis hinuntergeht, Überall ist es die Taschenform, die zu der Kugelform dazutritt, wenn es sich darum handelt, den Übergang zu bilden vom Pflanzlichen zum Tierischen. Es ist die Taschenform.

[ 16 ] Diese Taschenform, die wird uns verständlich, wenn wir von der Erde aufblicken zu dem Planetensystem. Sie können sich ja leicht vorstellen: Die Erde hat das Bestreben, allem auf ihr Lebendigen ihre eigene Form zu geben. Wenn aber der Planet von außen einwirkt, so wirkt er den Erdenkräften entgegen und sackt ein, was von der Erde als die Kugelform gegeben wird, und die verschiedenen tierischen Wesen sind in der verschiedensten Weise mit solchen Säcken, Taschen, gestaltet. Schauen wir die Planeten an in ihren verschiedenen Wirkungen. Der Saturn sackt in anderer Weise ein als der Jupiter oder Mars. Der Löwe ist einfach mit einer anderen Art von innerer Sackartigkeit ausgestattet, weil auf ihn nicht dieselben planetarischen Wirkungen geübt werden, wie zum Beispiel auf das Kamel und so weiter. Wir haben also da die Einsackungen.

[ 17 ] Nun tritt aber beim Tiere und auch beim Menschen — nämlich vor allem beim höheren Tiere, bei den niederen Tieren wird es etwas anders -, aber bei den höheren Tieren, da tritt etwas auf, was nun nicht bloß vom Planetarischen kommt, sondern wir können sagen: Beim tierisch-menschlichen Wesen — weil die höheren Tiere etwas Ähnliches zeigen — tritt nun nicht bloß die Taschenform auf. Die würde auftreten, wenn es nur Planeten gäbe, wenn der Fixsternhimmel nicht wirken würde. Aber zu der Taschenform kommt noch etwas dazu. Unter gewissen Verhältnissen ist der Mensch ganz zufrieden, wenn er nicht bloß eine Tasche hat, sondern auch noch etwas drinnen, und das tritt in der Tat beim tierisch-menschlichen Wesen auf, indem die Tasche mit der Füllung auftritt. Das heißt: Kugelformtasche, und die Tasche ist erfüllt.

[ 18 ] Sie brauchen nur die Sinnesorgane zu betrachten, das Auge, da haben Sie eine Tasche zunächst: die Augenhöhlen; dann die Erfüllung. Und diese Erfüllung, die namentlich bei den Sinnesorganen eintritt, die hängt nun, ebenso wie die Taschenform mit der Planetensphäre zusammenhängt, mit dem Tierkreis zusammen. Der Mensch, der in dieser Beziehung die vollkommenste tierische Organisation hat, hat deshalb auch, wenn sie auch in der verschiedensten Weise maskiert sind, zwölf Taschen mit Erfüllung. Daher habe ich in meiner «Anthroposophie» die zwölf Sinnesorgane aufzählen müssen.

[ 19 ] Nun können wir zurückfragen: Mit welchem Kosmischen hängt denn das Polyedrische zusammen? Sehen Sie, indem die Erde uns entgegentritt, hat sie als Ganzes eigentlich die Lebeform, und sie würde nur diese Form zeigen, wenn sie nur Wasser wäre. Aber in das Wasser kommt in der mannigfaltigsten Weise Störung hinein. Sie können die Störungen beobachten zum Beispiel bei Ebbe und Flut. Da wird das Wasser gestaltet.

[ 20 ] Und jetzt blicken wir zurück auf frühere Zeiten der Gestaltung der flüssigen Erde, wo sie die festen Einschläge bekommt. Heute noch kann man ja wissen, wie Ebbe und Flut zusammenhängt mit dem Monde. Ebenso hängt alles Polyedrische, alles das, was sich als Polyedrisches in die Erde hineingestaltet, mit dem Monde zusammen. So daß wir sagen können: Das polyedrische oder physische Wesen des Menschen hängt mit dem Monde zusammen, sein pflanzliches oder ätherisches Wesen mit der Erde, sein astralisches Wesen, das die Taschenform hervorbringen würde, mit der Planetensphäre, und die Erfüllung der Tasche mit dem Tierkreis.

[ 21 ] Nun aber ist dieses, was ich hier aufgeschrieben habe, für den Menschen in anderer Weise zutreffend als für die Tiere. Sehen Sie, beim Tier ist es wirklich so, daß der Himmel nur bis zum Tierkreis, nämlich das, was da drinnen liegt, nur bis zum Tierkreis eine Bedeutung hat. Was außerhalb des Tierkreises liegt, hat für das Tier keine Bedeutung. Die alte Weisheit hat daher sehr richtig das den Tierkreis genannt, denn sie hat hinzufügen können: Alles, was da draußen im Weltenall ist außer dem Tierkreis, das könnte auch nicht da sein, und die Tiere auf der Erde würden ebenso sein, wie sie sind. Nur was unter dem Tierkreis ist mit der Erde zusammen, dem Mond, hat für das Tier eine Bedeutung. Für den Menschen hat aber das, was außerhalb des Tierkreises ist, eine Bedeutung. Und zwar hat das, was außerhalb des Tierkreises liegt, für den Menschen Bedeutung, insofern es auf die Erfüllungen der Taschen wirkt. Also auf das, was unsere Taschen erfüllt, auf das wirkt auch noch, was außerhalb des Tierkreises ist. Beim Tier ist das nicht der Fall. Das ist nur so beim Menschen: Was außerhalb des Tierkreises vorhanden ist, wirkt auf die Erfüllung der Taschen.

[ 22 ] Beim Tier müssen wir sagen: Alles, was im Tierkreis liegt, wirkt auf die Erfüllung der Taschen. So daß wir also beim Tier in den Tierkreis selber hineingehen müssen; dann können wir erklären, wie die Erfüllungen seiner Taschen sich ausnehmen. Beim Menschen müssen wir über den Tierkreis hinausgehen, wenn wir uns erklären wollen, was zum Beispiel in seinen Sinnen vor sich geht. Dadurch rückt der Mensch mit seinem Verhältnis zum Kosmos über den Tierkreis hinaus. Das Tier nicht. Beim Tier ist es weiter so, daß die Planetensphäre als solche unmittelbar wirkt auf die Taschen. Also wir können sagen: Auf die Taschen wirkt sie. Dadurch, daß die Planetensphäre unmittelbar auf die Taschen beim Tiere wirkt - und die Taschen, die erstrecken sich nach innen und bilden nach innen die Organe -, dadurch bekommt das Tier seine inneren Organe ganz vollkommen, adäquat nachgebildet dem, was der Planetensphäre entspricht. Der Mensch rückt wiederum um ein Stückchen hinaus. Und wir können sagen: Beim Menschen ist es schon die Gegend gegen den Tierkreis zu, die auf seine Taschen wirkt.

[ 23 ] Beim Tiere wirkt die Erde unmittelbar auf alles das, was in ihm kugelig sein will, unmittelbar auf seine Kugelform. Beim Menschen geht das nicht. Der Mensch würde sonst auch ein Tier sein und sein Kugelstreben würde so sein wie beim Tiere. Das Tier will ja in einem gewissen Sinne eigentlich kugelig werden. Hier (siehe Zeichnung) hat es sein Rückgrat, dann Beine. Es wird nur daran gehindert, eine vollständige Kugel zu bilden. Ein Stück von dieser Kugel ist das Rückgrat. Der Mensch aber strebt von dem Irdischen so weg, wie er schon weggestrebt hat vom Tierkreis, von der Planetensphäre gegen den Tierkreis hin. Wir können sagen: Gegen die Planetensphäre wird des Menschen Kugelform gebildet. Er wird ein aufrechtes Wesen. Er strebt von der bloßen Anpassung an das Irdische hinweg.

[ 24 ] Und wenn wir nach dem Polyedrischen sehen, so müssen wir beim Tiere sagen: Direkt der Mond ist es, der ihm das Polyedrische gibt. Der Mensch strebt auch aus den Einflüssen des Mondes heraus, wir können sagen, vom Monde weg, und bekommt dort das, was ihm das Polyedrische gibt, zwischen der Erde und dem Monde. Man muß also gewissermaßen zwischen der Erde und dem Monde suchen, was dem Menschen das Polyedrische gibt. Dadurch ist aber der Mond noch immer wirksam auf den Menschen. Als Mond bleibt er trotzdem wirksam. Wir müssen also beim fünften suchen den Mond selber, der ja beim Tiere das Polyedrische bewirkt. Was tut er denn beim Menschen? Er bewirkt auch das Polyedrische, aber im Bilde, und während das Tier das Polyedrische in seiner Konfiguration hat, kommt der Mensch dazu, es herauszuheben aus seinem Organismus. Und dieses mathematisch-geometrische Vorstellen, es wird zum Bilde, es rückt heraus aus dem Leibe, und der Mensch stellt vorzugsweise heute mathematisch vor und möchte alles mathematisch begreifen, weil er durch den Mondeneinfluß sein eigenes Polyedrisches herausheben kann, und dadurch rückt es ins Bewußtsein herein. So daß wir sagen können: Vom Mond kommt das Verstehen des Polyedrischen im Bilde.

| Für den Menschen: | Außerhalb des Tierkreises Gegen den Tierkreis Gegen die Planetensphäre Vom Monde weg Mond |

Erfüllung der Taschen Taschen Kugelform Polyedrisch Verstehen des Polyedrischen im Bilde |

| Beim Tier: | Tierkreis Planetensphäre Erde Mond |

Erfüllung der Taschen Taschen Kugelform Polyedrisch |

[ 26 ] Sie sehen, indem wir den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit dem Kosmos verfolgen, kommen wir nicht nur zu dieser Art von Gestaltung, die wir schon studiert haben in den letzten Jahren, sondern wir begreifen auch, wie er sich nach innen hinein zum Beispiel gestaltet, wie er seine Nasenhöhle als einen Sack, als eine Tasche bildet, wie er seinen Magen als eine Tasche bildet. Würden wir noch weiter gehen, so würden wir die Organe überhaupt begreifen, wie sie sich da hineinbilden aus dem ganzen Kosmos heraus. Aber überall müssen wir den Kosmos zu Hilfe nehmen, wenn wir den Menschen verstehen wollen. Überall müssen wir sozusagen den Kosmos zu Hilfe nehmen, wenn wir fragen: Warum hat denn der Mensch dieses oder jenes Organ, seine Lunge zum Beispiel, die im Grunde genommen auch nur verstanden werden kann, wenn man sie zunächst, solange der Mensch noch Embryo ist, als eine sackartige Einstülpung begreift, an die sich hier Materielles anlegt; und dann reißt nach außen die sackartige Einstülpung, und das Organ schließt sich als ein solches im Inneren ab. Wir lernen, warum die Lunge oder überhaupt irgendein Organ im Inneren des Menschen ist, wenn wir dieses Organ auffassen als hervorgehend aus einem Sack, und das innere Ende des Sackes, wo der Sack also blind ausläuft, sich verdickend, durch andere Umstände sich besonders konfigurierend. Wenn wir ein solches Organ haben wie den Magen, da geht der Sack nach innen. Wenn wir ein solches Organ haben wie die Lunge, das Herz oder die Niere, und sehen, wie es sich bildet: das ist zunächst auch sackartig gebildet, dann aber verdickt sich der Sack, reißt sich ab mit seinem äußeren Ende — der Sack verdickt sich hier (siehe Zeichnung), reißt sich hier ab und das Organ ist da als innerlich abgeschlossenes Organ.

[ 27 ] Aber auch diese geschlossenen Organe, wenn wir uns fragen: Warum liegen sie an einem bestimmten Orte des Menschen, warum haben sie diese oder jene Form? — überall müssen wir dazu kommen, den Menschen im Zusammenhang mit dem ganzen Weltenall zu betrachten. Und verstehen können wir den inneren Aufbau des Menschen auch nur, wenn wir ihn im Zusammenhang mit dem Weltenall betrachten. Nun wird der heutige Naturwissenschafter sagen, wenn er hört, daß die Anthroposophie Lunge, Herz, Leber und so weiter aus dem Kosmos heraus erklären will: Total verrückt! — Total verrückt -, sagt der heutige Naturforscher. Insbesondere der Mediziner wird das sagen: Total verrückt! — Aber er sollte das eigentlich nicht, denn er sollte einsehen, wie ihm auf seinen Wegen, die er nur mit gewissen Scheuledern behaftet gehen will, eigentlich entgegenkommt, was Anthroposophie ist. Und dafür möchte ich Ihnen eine Art kleinen Beweises liefern.

[ 28 ] Da liegt vor mir eine Broschüre, welche der schon öfters vor Ihnen hier erwähnte Arzt, Mediziner und Biologe, Kriminalanthropologe Moriz Benedikt 1894 geschrieben hat. Ich zitiere öfters Moriz Benedikt, obwohl ich es eigentlich gar nicht gern tue, denn erstens ist der Mann wirklich, man möchte sagen, auf jeder Seite, die er schreibt, eitel. Er ist ein außerordentlich eitler Mann, der sich sehr selbst gefällt. Zweitens ist er ein verbohrter Kantianer. Allerdings kommt als mildernder Umstand in Betracht, daß er sich nach seinem eigenen Kopf einen Kantianismus zurechtformte und den dann vertritt mit einer gewissen Starrheit. Aber der Mann ist doch außerordentlich begabt. Obwohl er von alldem, was an Anthroposophisches und Ähnliches herankommt, nicht das geringste wissen will, kann man doch sagen, daß der Mann einfach durch sein Drinnenstehen in der Medizin und in der Naturwissenschaft zu einem gewissen unbefangenen Urteil über den Wert seiner Wissenschaftlichkeit kommt. Er kann nicht heraus; aber in einer merkwürdigen Weise lugt er heraus. Die anderen sitzen auch in ihrer Wissenschaft wie in einem Gefängnis, aber sie gucken nicht einmal heraus. Der guckt aber immerfort heraus, und da kommt er doch zu außerordentlich interessanten Dingen. Und da ihm seine Eitelkeit sehr viele Feinde gemacht hat, so sagt er manches über andere, die sich ihm als Feinde ohne Maske zeigen; sonst ist man ja immer «gut Freund» untereinander. Da sagt er etwas über seine Kollegen, unter denen er ja deshalb auch niemals so recht hat aufkommen können, da sagt er etwas, was aber außerordentlich charakteristisch ist. Natürlich weiß er ja gar nichts von Anthroposophie, aber dennoch, Anthroposophie kann man ja auch in bezug auf ihre Qualitäten nehmen und kann sagen, er ist jedenfalls antianthroposophisch gesinnt. Aber dieser Antianthroposoph, der sagt doch zum Beispiel in einer Broschüre, die da vor mir liegt: «Das Pharisäertum ignoriert oder verleugnet alle Lehren und Tatsachen, die in seine Anschauungsweise nicht hineinpassen, und es verfolgt nicht nur die Lehre, sondern mit noch größerer Erbitterung die Lehrer. Der Pharisäismus ist ein ganz eigentümlicher Braten. Er duftet für die Nasen der Pharisäer und verbreitet einen scharfen, reizenden Geruch für andere. Das Pharisäertum ist so naturgemäß mit dem Gelehrtenhandwerk verflochten, daß ich mich trotz meines Pharisäerhasses oft frage: Wie oft warst du schon und in wie vielen Fällen bist du Pharisäer? Ich wäre jedem sehr dankbar, der mir diese Frage exakt beantworten würde.»

[ 29 ] Ich bin allerdings meinerseits überzeugt, daß er nicht dankbar wäre, sondern ordentlich schimpfen würde, wenn man ihn auf seinen eigenen Pharisäismus aufmerksam machen würde, wenn man ihn also selber daran fassen würde. Aber in seiner eigentümlichen Art erblickt er das Pharisäertum bei den anderen ausgezeichnet gut.

[ 30 ] Nun aber kommt er zu sprechen auf seine eigene Entwickelungsgeschichte, durch die er begreiflich machen will, daß er eben ein anderer Mediziner geworden ist als die Herren Kollegen. Da sagt er: «Für meine Entwickelungsgeschichte und auch für die wissenschaftliche Stellung in dieser Frage, die uns hier beschäftigt, waren zwei schwere Schicksalsschläge verhängnisvoll.»

[ 31 ] Sie werden natürlich auch gleich ein bißchen ein starkes Stückchen Eitelkeit aus der Darstellung verspüren: «Der erste ist, daß ich, bevor ich Mediziner wurde, Mathematik und Mechanik studierte. Wir hatten damals an der Wiener Universität einen hochbedeutenden Mathematiker, Professor von Ettingshausen, der uns die schwierigsten Probleme der mathematischen Physik vortrug und uns dafür einnahm. Von ihm hörte ich die Lehren von Cauchy und Poisson entwickeln, und von Petzval lernten wir, mechanische Probleme in mathematische Formeln zu gießen. Es wird nun aber leicht zu zeigen sein, wie verhängnisvoll mathematisches Denken für einen Mediziner, besonders aber für einen Kliniker ist.»

[ 32 ] Das wollen wir abwarten. Wir werden es auch schon sehen, warum das verhängnisvoll ist, besonders wenn er etwas von der Medizin versteht! Nun erzählt Professor Benedikt weiter. Man sollte ja glauben, daß das für ihn ein guter Schicksalsschlag war, wenn er Mathematiker war, aber er nennt es einen schlechten Schicksalsschlag, aus dem Grunde, weil er nun dadurch denken gelernt hat. Das konnten andere Kliniker nicht. Darum haßten sie ihn. Daher haßten sie ihn, weil er das studiert hatte, denn sonst hätte er auch nichts anderes verstanden, als was die anderen Kliniker von der Medizin verstanden hatten. «Der zweite Schicksalsschlag, der mich in jungen Jahren traf, war, daß ich ein Schüler Skodas war und noch heute an seinen Lehren hänge. Er war der Kant der medizinischen Erkenntnislehre, und er entwickelte den Höhepunkt seines Geistes nicht in Büchern, sondern in der Besprechung von Diagnosen, von therapeutischen Indikationen und besonders in den Epikrisen nach vorgenommenen Sektionen. Skoda war in seiner Jugend Mathematiker gewesen» — was also auch ein Schicksalsschlag war! — «und hatte aus derselben die wichtigste, die fundamentalste Lehre der medizinischen Denkmethodik in die Medizin hineingetragen, aber leider nur für einzelne Fragen dauernd; diese wichtige Lehre, die ich von Skoda empfing und schon von meinen mathematischen Studien her mir eingeprägt hatte, ist: daß man sich bei jedem wissenschaftlichen Beweisverfahren nicht nur dessen bewußt sein muß, was man weiß, sondern auch dessen, was noch unbekannt ist.» Also Benedikt war auch mit Skoda zusammen. Man soll sich bei dem gegenwärtigen naturwissenschaftlichen Verfahren — denn von dem redeten sie — ja nur bewußt sein nicht nur dessen, was man weiß, sondern auch dessen, was noch unbekannt ist. Diesen Grundsatz hat nun tatsächlich Benedikt in zahlreichen Abhandlungen mit einem gewissen Fanatismus vertreten; daß man nicht nur Rücksicht nehmen muß auf das, was man weiß, sondern auch auf das, was man nicht weiß. Er sagt darüber weiter: «Aber diese Grundregel in der Medizin ist der großen Mehrzahl der Biologen unbekannt, ja, selbst unverständlich. Als ich zum Beispiel vor einigen Jahren einem berühmten auswärtigen Anatomen ein Manuskript in fremder Sprache mit der Bitte zusandte, er möge es sprachlich korrigieren, schrieb er, als ich obigen Satz anführte, an den Rand, er verstehe den Sinn desselben nicht.» Also der Benedikt hat geschrieben, man solle auch ins Auge fassen das, was man nicht weiß, und er wollte, daß der andere ihm den Sinn des Satzes richtig ins Französische übersetze. Da hat dieser geschrieben, das verstehe er nicht.

[ 33 ] «Als ich die Randbemerkung einem Professor an der Technik zeigte, lächelte er. Für jeden Mann der exakten Wissenschaft ist doch der Satz selbstverständlich.»

[ 34 ] Der lächelte, denn der versteht mathematische Denkmethode; er lächelte, weil er innerlich sich lustig machte über die Mediziner, die da glauben, sie brauchten das, was sie nicht wissen, nicht zu berücksichtigen. Der Techniker muß das wissen, denn er hat ja mathematische Vorbildung.

[ 35 ] «Als ich aber einem berühmten medizinischen Gelehrten in Wien die Bemerkung des auswärtigen Kollegen als Kuriosum mitteilte, sagte er naiv: Ja, wie sollte man denn das Unbekannte kennen? — Diese historische Anekdote wirft ein grelles Licht auf die noch heute allgemein herrschende medizinische Denkmethodik und auf die kolossalen Irrtümer, die täglich und stündlich in der medizinischen Literatur begangen werden.»

[ 36 ] Ich lese Ihnen die Sätze eines Mediziners vor! Nun aber kommt etwas außerordentlich Wichtiges. Nämlich Moriz Benedikt schreibt, wie es in der medizinischen Wissenschaft hergeht deshalb, weil man nie auf das Unbekannte Rücksicht nimmt: «Die Probleme sind in der Biologie zumeist gegeben, zum Beispiel die Funktion eines Organs. Die Bedingungen dieser Funktion sind zum Teile unbekannt und noch zu suchen.»

[ 37 ] Nun führt er ein Beispiel an: «Die Leber zum Beispiel sondert Galle ab. Der Grund dieser Absonderung sind vor allem die spezifisch-biochemischen Eigenschaften der Zellen.»

[ 38 ] Wir wollen davon absehen, daß er hier von den biochemischen Eigenschaften der Zellen spricht, was keinen rechten Sinn hat. Aber da stehen wir eben auf demselben Standpunkt, von dem aus er über die Leber spricht.

[ 39 ] «Es ist der Grund zu suchen, wie diese differentiellen Eigenschaften entstehen» — das heißt, er will den Grund suchen, wodurch sich die Leber abdifferenziert von anderen Organen; also er will das Unbekannte jetzt ins Auge fassen. Das Bekannte ist, daß die Leber Galle absondert. Aber jetzt kommt das Unbekannte, und da zählt er, geben Sie acht, recht viel auf.

[ 40 ] «Es ist der Grund zu suchen, wie diese differentiellen Eigenschaften entstehen, wie sich aus den Elementen das Organ aufbaut, wie es auf seinen Platz gelangt, warum es gerade in der bestehenden Verbindung mit den umgebenden Organen ist, wie es mit Hilfe spezifischer, hämodynamischer Kräfte und hämostatischer Verhältnisse die Spezifität seiner Zellen aufrecht erhält, wie es mit Hilfe des reflektorischen, zentralen und zentrifugalen Nervensystems zur rechten Zeit und in rechter Intensität zur Funktion angeregt wird, welches die Bedingungen der Gesamternährung seien, um die Funktion und ihre Rechtzeitigkeit zu erhalten, welche Bedingungen schädlich auf dieselbe wirken, so daß momentane oder bleibende Störungen der Funktionen eintreten, et cetera.»

[ 41 ] Das alles ist unbekannt. Dieses Unbekannte muß man sich vorhalten. Dann aber sagt Moriz Benedikt weiter: «Der Wissenschaft stoßen diese Fragen im Laufe großer Zeiträume nacheinander auf.» — Also es stoßen nur die Fragen auf! - «Die Literatur jeder Zeit aber rechnet mit dem Bekannten ohne Frage nach dem Unbekannten und stellt sich, als ob das Grundproblem bereits völlig gelöst wäre.» — Das heißt, redet nicht vom Unbekannten. Solche Leute wie Moriz Benedikt kommen wenigstens dazu, diese Unbekannten alle aufzuzählen. «Darum sind die zeitgenössischen herrschenden Lehren in jeder Epoche nur zum kleinen Teile wahr, und sie enthalten einen kolossalen Prozentsatz zeitgenössischer und überkommener Irrtümer, die sich lange als Erbsünde auch auf die kommenden Geschlechter fortpflanzen.»

[ 42 ] Was sagt denn eigentlich dieser Mediziner? Er sagt: Wir haben eine medizinische Literatur, aber sie berücksichtigt eigentlich nur das, was bekannt ist, Aber das Unbekannte, das taucht nach langen Zeiträumen immer wieder auf. Was will denn der Benedikt? Er will, daß man sich immer bewußt sei des Unbekannten. Was würde also zum Beispiele-mit der Leber geschehen? Wer nun als richtiger Mediziner von der Gegenseite des Benedikt die Leber beschriebe, der würde versuchen, die biochemischen Eigenschaften der Leberzellen zu suchen, wird versuchen, die Tatsache hinzustellen, daß die Leber Galle absondert. Dann ist er zufrieden, denn er redet von dem Unbekannten nicht. Der Benedikt würde sagen: Gut, die Leber sondert Galle ab; das rührt von der biochemischen Beschaffenheit der Leberzellen her. Aber ich bin ein gewissenhafter Forscher, daher muß ich alles das, was ich nicht weiß von der Leber und Galle, auch sagen. Er wird also in sein Buch hineinschreiben: Das weiß man; aber man weiß nicht, wie die Leber an ihren Platz kommt, wie die Blutstatik, das heißt, die Kreislaufstatik und -dynamik auf die Leber wirken, was das Nervensystem mit der Leber zu tun hat, das Gesamtnervensystem und die einzelnen Nerven, und wie der Beitrag der Leber zu der Ernährung zustande kommt. Davon würde überall stehen: Das weiß man nicht. Dadurch würden sich die Benediktschen Bücher von den anderen unterscheiden. Wissenschaftlich würde er also sehr bescheiden sein.

[ 43 ] Aber diese Frage, sagt er, diese Frage nach dem Unbekannten, die taucht im Laufe der Jahrhunderte auf; aber so, wie sie hier gestellt werden, die Fragen, wenn man sie auf ihre wirklichen Grundlagen zurückführt, da könnte man, wenn die Gesinnung auch von Benedikt vorhanden bleibt, bis zum jüngsten Tag warten, und man würde immer das Bekannte registrieren und dann das Unbekannte mit den vielen Fragen. Die Benediktschen Bücher würden sich von den anderen immer nur dadurch unterscheiden, daß da immer das Unbekannte steht, denn der Benedikt würde nie darauf eingehen, daß ein Unbekanntes in den Kosmos hinausgeführt werden muß; daß es so lange ein Unbekanntes sein wird, bis man es aus dem Kosmos heraus erklärt.

[ 44 ] Sie sehen, ein vernünftiger Mediziner sagt aus seiner Medizin heraus: Mit dem, was uns zur Verfügung steht, können wir den Menschen nicht erklären, wir können nur Unbekanntes registrieren. Nur versteift er sich darauf, sich nicht einzulassen auf das, was nun, allerdings auch natürlich langsam und allmählich, Antwort gibt auf diese Fragen, die er als Unbekanntes hinstellen muß.

[ 15 ] Die Fragen sind also da in der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft. Anthroposophie kommt den Fragen der gewöhnlichen Wissenschaft entgegen. So ist es. Das sollte mit aller Energie immer wieder und wiederum betont werden. Moriz Benedikt findet, daß gerade alle die Unarten, die namentlich in seiner Wissenschaft vorhanden sind, davon herrühren, daß die Leute vom Unbekannten nichts wissen, und mit dem, was sie konstatieren aus dem rein Sinnenfällig-Tatsächlichen heraus, nun an die Menschheit herangehen. Da wird er wiederum eben ganz sarkastisch, wo er das weiter charakterisiert: «Diese wissenschaftliche Mißwirtschaft ist heute noch ebenso in Flor... .» — es ist nicht seine, es ist eine von den Herren Kollegen! -, «diese wissenschaftliche Mißwirtschaft ist heute noch ebenso in Flor als vor tausend Jahren, ja sie ist ärger als je, da die Produktion an Schnelligkeit zugenommen hat.»

[ 46 ] Früher, meint der Benedikt, konnte man nicht so schnell seine Unarten in die Öffentlichkeit hinausbringen.

[ 47 ] «Jeder flüchtige Einfall, jede flüchtige Unternehmung wird heute so rasch publiziert, daß nur noch «Telegraphische Mitteilungen> in der medizinischen Journalistik fehlen, und daß wir es vielleicht noch erleben, daß telephonische Sprechzellen errichtet werden, nur damit wissenschaftliche «Ideen» nicht neun Minuten brach liegen. In früheren Zeiten gingen einer Publikation mehr Jahre voraus als jetzt Stunden.»

[ 48 ] Nun, auch schließlich auf das Publikum, das den Medizinern zuhört und auf sie schwört, ist ja Moriz Benedikt durchaus in einer richtigen Weise zu sprechen! Er charakterisiert einfach durch einen Spruch dieses Publikum, indem er sagt: «Meier, Müller, Schulze, Schmidt, machen jede Schandtat mit.»

[ 49 ] Dann aber kommt er wiederum — die Schandtaten sind nämlich die seiner Kollegen — auf das, was er nun dieser Kollegenschaft vorzuwerfen hat, zu sprechen, und da kommt er dazu, folgendes zu sagen: «Diese Übelstände in der Biologie werden sich nicht bessern, bis die große Reform der medizinischen Erziehung bei den Lehrern beginnen wird. Wer nicht den Beweis liefert, daß er ernste mathematische und mechanische Studien gemacht hat, ist zum Denker und Forscher nicht reif und also noch weniger zum Lehrer geeignet. Das persönliche Genie hat viel geleistet; es hinkt aber und wird immer hinken, so lange es nicht in der mathematischen Gehschule war.»

[ 50 ] Es gehört natürlich nicht Mathematik dazu für jeden, der auf vernünftige Dinge hinhorchen will. Aber zur Behandlung, zur wirklichen Behandlung einer wirklichen Wissenschaft gehört durchaus mathematisch geschulte Denkmethode. Daher hat auch schon Plato — den übrigens Moriz Benedikt weidlich beschimpft - an die Türe, an die Pforte geschrieben: Nur für mathematisch Gebildete ist hier Einlaß -, nämlich in der Platonischen Akademie, was aber natürlich die nicht mathematisch geschulten Philosophen der Neuzeit nicht hindert, über Plato zu schreiben. So daß man wirklich sagen kann: Über Plato schreiben heute meistens Leute, die, wenn der Plato mit seiner Schule noch da wäre, nur vor dem Tor draußen sitzen dürften.

[ 51 ] Aber aus dem, was ich Ihnen aus der Broschüre von Moriz Benedikt mitgeteilt habe, werden Sie sehen, wie das Verhältnis der heutigen Wissenschaftlichkeit zu demjenigen ist, was sie selber wünschen müßte, und wie einer, der zwar nicht Anthroposoph ist, dem aber, nur gerade, weil er etwas eitel ist und mit seinen Kollegen durch seine Eitelkeit etwas in Konflikt gekommen ist, dann doch ein Loch im Hirnkästchen aufgegangen ist für die Schäden — wie ein solcher urteilt. Seien wir uns also durchaus klar: Die Lage ist heute schon so, wie sie unbefangene anthroposophische Erkenntnis schildern muß, und die Beweise können überall geholt werden in dem äußeren Wissenschaftsbetrieb selber, wenn man nur will.

[ 52 ] Was man aber holen muß, das ist das, daß man wirklich den Menschen betrachten lernt so, wie man es in der Physik ganz vernünftig findet. Ich habe Ihnen den Vergleich auch schon in diesen Tagen gesagt: Wenn man die Magnetnadel studiert und wollte sie nur so studieren, daß man sagt, sie richtet sich durch ihre inneren Kräfte, so würde man niemals die nord-südlichen Kräfte der Magnetnadel verstehen. Man muß sich klar sein darüber, daß die ganze Erde zwei Kräfte hat, daß von außen die Pole der zwei Kräfte bestimmt werden. So ist es auch ein Unding, den Menschen auf den Seziertisch hinzulegen und sein ganzes Wesen aus dem, was innerhalb seiner Haut ist, erklären zu wollen. Man braucht die ganze Welt, um das, was im Menschen und am Menschen ist, wirklich verstehen zu können.

Nineteenth Lecture

[ 1 ] We have recently been considering the human being and his relationship to the cosmos. To those who are confined to the present-day world view, it still seems, one might say, quite absurd to link the nature of the human being in this way to the nature of the cosmos, and in the widest circles today, such a connection would probably not be considered scientific. Nevertheless, in view of the intellectual currents of the present day, it is already urgently necessary to point out with all our energy precisely those things that we have considered here. For it can be said that these things are entirely in line with today's thinking. Only they are rejected with all vehemence by present-day thinking. But this causes unspeakable damage to the spiritual life of humanity.

[ 2 ] Let us first of all form a kind of summary of what I have presented here recently. We have looked at the form of the human being as a result of causes that must be sought in the fixed stars, namely in their representative, the zodiac. We have seen that we must first look to the zodiac as the representative of the fixed stars if we want to understand the form, shape, and structure of the human being. So we have the twelve-membered zodiac and, by studying this twelve-membered animal, we find that we can understand human form down to its smallest details.

[ 3 ] If we then want to understand the stages of human life, we must look to the planetary system and find in it the elements for understanding the stages of human life.

[ 4 ] We then made our way from understanding the stages of life to understanding the soul. But to do this, we had to approach the human being itself, that which is formed within it, that which lives within it. And we then tried to find the soul in the form of the human being and in the stages of life through imagination, feeling, and willing. And yesterday we also tried to find the spiritual in the human being in the soul.p>

[ 5 ] Now we come with the soul that we are considering, I would say, from the periphery of the world into actual earthly life, when we consider the soul in the life of the human being between birth and death. We can consider it when we look at it in its true relationship to the human form and to human life.

[ 6 ] Again, the spirit, which we saw yesterday that human beings actually experience only in images, we must seek in the soul. We come, if I may express it thus, down from the heavens to the earth. When we consider the form of the human being, we must go as far as the fixed stars; when we consider the life of the human being, we must go as far as the planetary sphere; when we consider the soul of the human being in its relationship between birth and death, we must first descend to the earthly realm. In this consideration, the human being in its connection with the cosmos becomes a whole for us.

[ 7 ] Now, if we properly appreciate this fact, we are also able to draw the boundary line between the animal and the human being. And this can be done in the following way. Let us first consider what we can understand through the zodiac, let us consider this in humans and animals, and we see that it actually presents itself to us in different ways. But in order to grasp this whole connection, we must start from how these different elements—the zodiac, the planetary sphere, the earth with everything we considered yesterday—act upon humans and animals.

[ 8 ] In humans, we first have the physical body. This physical body does not appear to us in the form we know outside of humans as the physical world. The physical appears to us outside of human beings in the mineral kingdom and its forms. What we encounter in the mineral kingdom and its forms is, of course, very dissimilar to the physical body of human beings. But it is only dissimilar to the physical body of the human being because in the human being the physical is clothed in the etheric, the astral, and the ego, all of which transform the physical, all of which adapt the physical, whereas in the outer physical realm this physical appears to us without being permeated by the etheric, the astral, or the ego.

[ 9 ] When we consider the original form of minerals, we see the crystal form, the polyhedral form (see drawing); at the top right, the mineral appears to us as somewhat polyhedral. We cannot understand this polyhedral form, which we encounter in one mineral in one form and in another mineral in another form, unless we first look at the material that has been formed from the forces that are active within the space of the mineral. We must imagine that if we have any elongated mineral, then the forces acting in this direction (drawing on the right) are suited to pulling the mineral along its length. The forces acting in the direction of °P (right, horizontal line in the middle) may then develop a lesser strength — or how we want to express it — which makes the mineral narrower in this direction, and so on. In short, in order to be able to speak of minerals at all, regardless of whether these forces act from outside or from within, we must imagine that these forces are at angles to each other, act in certain directions, and above all, we must imagine that these forces are present in the universe, or at least that they are effective within the Earth's sphere.

[ 10 ] But then, if they are effective, they must also act on the physical body of the human being, and the physical body of the human being must have within itself the tendency to become polyhedral. It does not actually become polyhedral because it still has its etheric body, its astral body, which prevents human beings from becoming a cube or an octahedron or a tetrahedron or an icosahedron, and so on. But the tendency to become something like this is within the human being, so that we can already say: insofar as the human being is a physical being, he strives to become polyhedral. If you are glad that you do not wander around as a cube or a tetrahedron or an octahedron, this is precisely because the other forces, those of the etheric body and the astral body, counteract the octahedral or cubic forces within you.

[ 11 ] But human beings are not merely physical bodies; they also carry their etheric bodies within them. What he is through his etheric body makes him, in turn, one with the plant world as a being. Just as he represents the environment through his physical body, insofar as it is mineral and physical, so he represents the environment through what he is through his etheric body, insofar as it is plant-like.