Old and New Methods of Initiation

GA 210

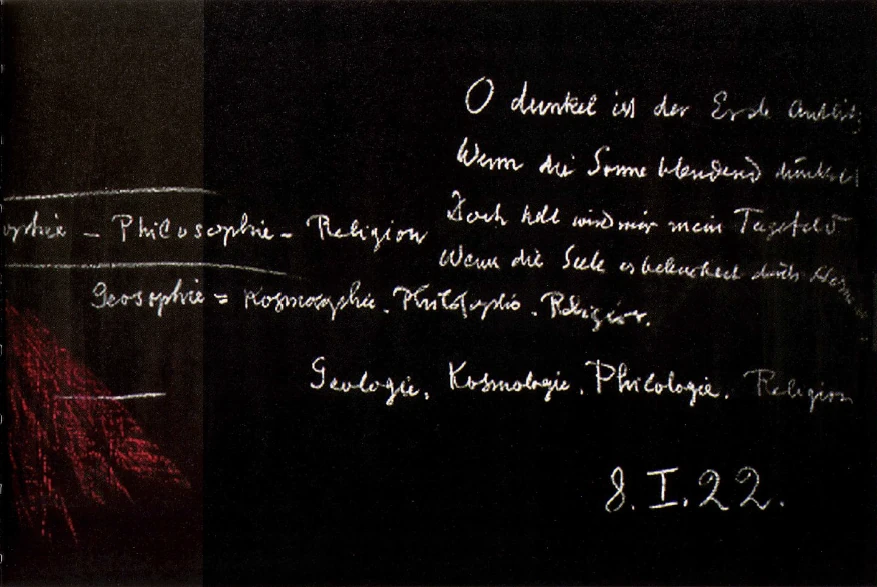

8 January 1922, Dornach

Lecture III

Today we shall consider the differentiations in mankind from another viewpoint, namely that of history. With the express aim of promoting an understanding for the present time we shall look at human evolution starting at a point immediately following the catastrophe of Atlantis. If human evolution can be considered to encompass any evolution of civilization, then we shall find the first decisive period of development to be the culture epoch of ancient India. In my book Occult Science1 Rudolf Steiner, Occult Science—An Outline. For the post-Atlantean cultural periods see the chapter ‘Man and the Evolution of the World’. you will find this culture of ancient India described from a particular viewpoint. Though the Vedas and Indian philosophy are rightly admired, they are actually only echoes of that ancient culture, of which there exist no written records. In the words of today we have to describe the culture of ancient India as a religious culture in the highest sense. To understand this properly we shall have to discuss it more thoroughly.

The religious element of ancient Indian culture included what we today would call science and art. The total spiritual life of the whole human being was encompassed by this culture for which the most pertinent description is that it was a religious culture. This religious culture generates the feeling in human beings that in the depths of their being they are linked with a divine, spiritual world. This feeling was developed so intensely that the whole of life was illumined by it. Their clearer states of consciousness, which were preparations for today's waking state, and also their dream consciousness, which became lost in our chaotic dream and sleep life as evolution progressed, were both states of consciousness filled with an instinctive awareness of the links between the human realm and the divine, spiritual realm.

But our idea of religion today is of something rather general. The concept of religion makes us think too strongly of something general, something abstract and rather detached from everyday life. For the people about whom we are speaking, however, religion and the content they associated with it gave them a knowledge expressed in pictures, a knowledge of the being of man and an extensive picture knowledge of the structure of the universe.

We have to imagine, though, that what lived in these people's view of the world, by way of a picture knowledge of the structure of the universe, in no way resembled our modern knowledge of astronomy or astrophysics. Our astronomy and astrophysics show us the mechanics of the universe. The ancient Indian people had a universe of picture images populated with divine, spiritual beings. There was as yet no question, in the present sense, of any external, merely mechanical rules governing the relationships between heavenly bodies or their relative movements. When those people looked up to the starry heavens they saw in the external constellations and movements of the stars only something perfectly familiar to them in their picture consciousness. It was something which may be described as follows.

Suppose we were to see a vivid, lively scene with bustling crowds and people going about all kinds of business, perhaps a public festival with much going on. Then we go home, and next morning the newspaper carries a report about the festival we ourselves attended. Our eyes fall on the dead letters of the printed page. We know what they mean and when we read the words they give us a weak, pale idea of all the lively bustle we experienced the day before. This can be compared with what the ancient Indian people saw in their instinctive vision and in relation to this what they saw in the constellations and movements of the stars. The constellations and movements of the stars were no more than written characters, indeed pale written characters. If they had copied down these characters on paper, they would have felt them to be no more than a written description of reality.

What these people saw behind the written characters was something which they not only came to know with their understanding but also to love with their feelings. They were unable merely to take into their ideas all that they grasped in pictures about the universe; they also developed lively feelings for these things. At the same time they developed a permanent feeling that whatever they did, even the most complicated actions, was an expression of the cosmos filled with divine spiritual weaving. They felt their limbs to be filled with this divine, spiritual cosmic weaving. They felt their understanding to be filled with this divine spiritual weaving, and likewise their courage and their will. Thus, speaking of their own deeds, they were able to say: Divine, spiritual beings are doing this. And since in those ancient times people knew very well that Lucifer and Ahriman are also to be found among those divine, spiritual beings, so were they aware that because divine, spiritual beings worked in them, they were therefore capable of committing evil as well as good deeds.

With this description I want to call up in you an idea of what this religion was like. It filled the whole human being, it brought the whole human being into a relationship with the abundance of the cosmos. It was cosmic wisdom and at the same time it was a wisdom which revealed man. But then progress in human evolution first caused the most intense religious feelings to pale. Of course, religion remained, in all later ages, but the intensity of religious life as it was in this first Indian age paled. First of all what paled was the feeling of standing within the realm of divine, spiritual beings with one's deeds and will impulses. In the ancient Persian age, the second post-Atlantean cultural epoch, people still had this feeling to some extent, but it had paled. In the first post-Atlantean epoch this feeling was a matter of course. In the second cultural blossoming, the ancient Persian time, the profoundest, most intense religious feelings paled, so human beings had to start developing something out of themselves in order to maintain their link with the cosmic, divine spiritual realm in a more active manner than had at first been the case. So we might say: The first post-Atlantean period was the most intensely religious of all. And in the second period religion faded somewhat, but human beings had to develop something by inner activity , something which would unite them once more with the cosmic beings of spirit and soul.

Of all the words we know, there is one we could use to describe this, although it was coined in a later age. It comes from an age which still possessed an awareness of what had once been a part of human evolution in ancient times. When an ancient Indian looked up to the heavens, he sensed the presence of individual beings everywhere, one divine spiritual being next to another—a whole population of divine spiritual beings. But this faded, so that what had been individualized, what had been individual, divine, spiritual beings faded into a general, homogeneous spiritual cosmos. Think of the following picture: Imagine a swarm of birds close by. You see each individual bird, but as the swarm flies further and further away it becomes a black blur, a homogeneous shape. In the same way the divine spiritual cosmos became a blurred image when human beings moved spiritually away from it.

The ancient Greeks still had an inkling of the fact that once, in the distant past, something like this had been at the foundation of what human beings saw in the spiritual world. Therefore they took into their language the word ‘sophia’. A divine, spiritual cosmos had once, as a matter of course, poured itself into human beings and had taken human beings into itself. But now man had to approach what he saw from a spiritual distance—a homogeneous cosmos—by his own inner activity. This the Greeks, who still had a feeling for these things, called by the expression: ‘I love’; that is: ‘philo’. So we can say that in the second post-Atlantean period, that of ancient Persia, the initiates had a twofold religion where earlier on religion had been onefold. Now they had philosophy and religion. Philosophy had been achieved. Religion had come down from the more ancient past, but it had paled.

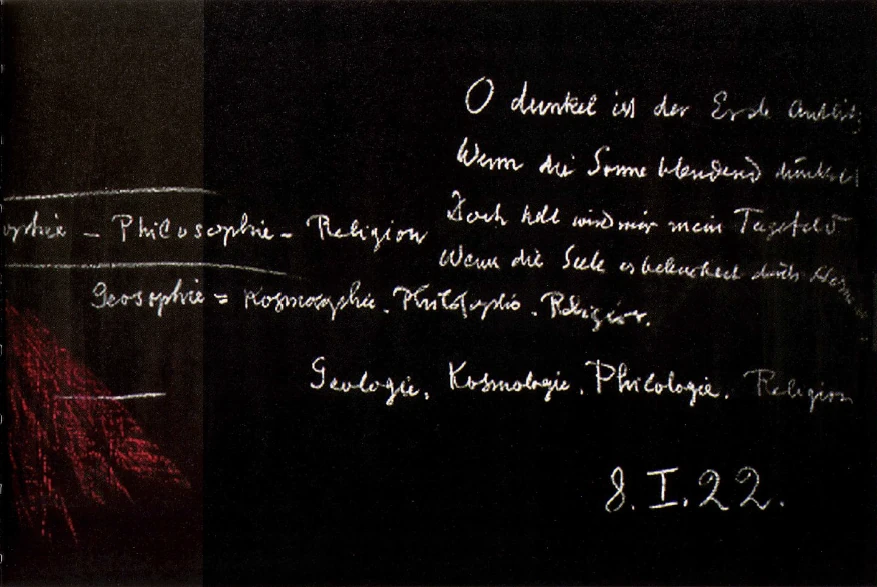

Passing now to the third post-Atlantean period, we reach a further paling of religion. But we also come to a paling of philosophy. The actual, concrete process that took place must be imagined as follows. In ancient Persian times there existed this homogeneous shape made up of cosmic beings and this was felt to be the light that flooded through the universe, the primeval light, the primeval aura, Ahura Mazda. But now people retreated even further from this vision and began in a certain way to pay more attention to the movements of the stars and of the starry constellations. They now sensed less in regard to the divine, spiritual beings who existed in the background and more in regard to the written characters. From this arose something which we find in two different forms in the Chaldean wisdom and the Egyptian wisdom, something which comprised knowledge about the constellations and the movements of the stars. At the same time, the inner activity of human beings had become even more important. They not only had to unite their love with this divine Sophia who shone through the universe as the primeval light, but they had to unite their own destiny, their own position in the world, with what they saw within the universe in a cosmic script provided by the starry constellations and the starry movements. Their new achievement was thus a Cosmo-Sophia. This cosmosophy still contained an indication of the divine, spiritual beings, but what was seen tended to be merely a cosmic script expressing the deeds of these beings. Beside this there still existed philosophy and religion, which had both faded.

In order to understand this we must realize that what we today call philosophy is naturally only an extremely weak, pale shadow image of what was still felt to be more alive in the Mysteries of the third post-Atlantean period and what in an even paler form the Greeks later called philosophy. In the culture of the third post-Atlantean period we see everywhere expressions of these three aspects of the human spirit: a cosmosophy, a philosophy and a religion.2 See also Rudolf Steiner, Philosophy, Cosmology and Religion, Anthroposophic Press, New York 1984, and Rudolf Steiner's own reports of these lectures in Cosmology, Religion and Philosophy, Anthroposophic Press, New York 1984. And we only gain proper pictures of these when we know we have to remind ourselves that right up to this time human beings lived in their soul life more outside the earthly realm than within it. Looking for instance at the Egyptian culture from this point of view—and it was even more pronounced in the Chaldean—we see it rightly only if we remind ourselves that those who had any part in this culture indeed took the most intimate interest in the constellations of the stars as evening approached. For example they awaited certain manifestations from Sirius, they observed the planetary constellations and applied what they saw there to the way the Nile gave them what they needed for their earthly life. But they did not speak in the first instance of the earthly realm. This earthly realm was one field of their work, but when they spoke of the field they were tilling they did so in a way which related it to the extraterrestrial realm. And they named the varying appearances of the patch of earth they inhabited in accordance with whatever the stars revealed as the seasons followed one upon another. They judged the earth in accordance with the heavens. From the soul point of view, daytime brought them darkness. Light came into this darkness when they could interpret what the day brought in terms of what the starry heavens of the night showed them.

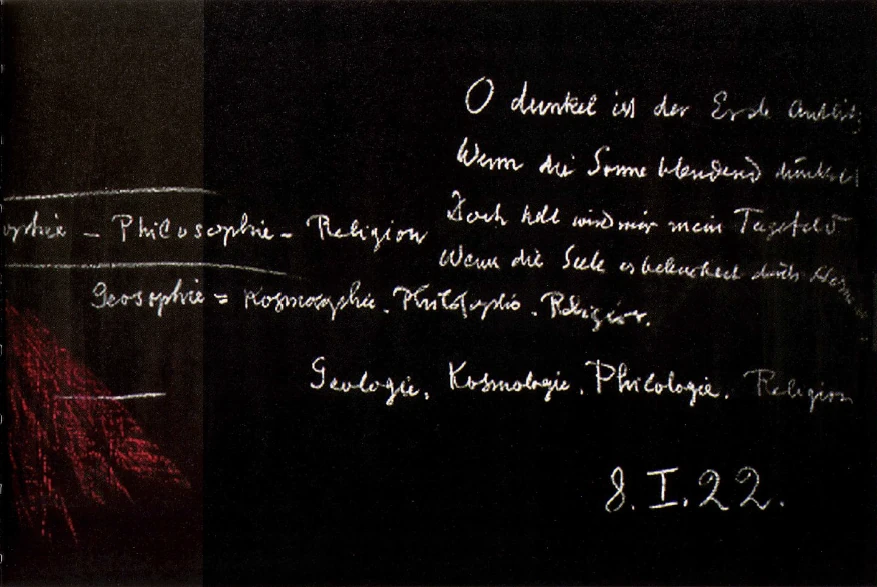

What people in those times saw might be expressed thus: The face of the earth is dark when the sun obscures my vision with dazzling brightness; but light falls on the field of my daily work when my soul shines upon it through starry wisdom.

Writing down a sentence like this gives us a sense for what the realm of feeling in this third post-Atlantean period was like. From this in turn we sense how those who still stood in the after-echoes of such a realm of feeling could say to the Greeks, to those who belonged to the fourth post-Atlantean cultural period: Your view of the world, indeed your whole life, is childlike, for you have knowledge only of the earth. Your ancestors in ancient times knew how to illumine the earth with the light of the heavens, but you live in the darkness of earth.

The ancient Greeks experienced this darkness of earth as something light. Their inclination was gradually to overcome and transform the older cosmosophy. So, as everything that looked down from the broad heavens became paler still, they transformed the older cosmosophy into a geosophy. Cosmosophy was nothing more than a tradition for them, something they could learn about when they looked back to those who had passed it down to them from earlier times.

Pythagoras, for instance, stood at the threshold of the fourth post-Atlantean period when he journeyed to the Egyptians, to the Chaldean and even further into Asia in order to gather whatever those who lived there could give him of the wisdom of their forefathers in the Mysteries, whatever they could give him of what had been their cosmosophy, their philosophy and their religion. And what was still comprehensible for him was then just that: cosmosophy, philosophy, religion.

However, there is something we today take far too little into consideration: This geosophy of the ancient Greeks was a knowledge, a wisdom which, in relation to the earthly world, gave human beings a feeling of being truly connected with the earth, and this connection with the earth was something which had a quality of soul. The connection with the earth of a cultured Greek had a quality of soul. It was characteristic for the Greeks to populate springs with nymphs, to populate Olympus with gods. All this points, not to a geology, which envelops the earth in nothing but concepts, but to a geosophy in which spiritual beings are livingly recognized and knowingly experienced. This is something which mankind today knows only in the abstract. Yet right into the fourth century AD it was still something that was filled with life.

Right into the fourth century AD a geosophy of this kind still existed. And something of this geosophy, too, came to be preserved in tradition. For instance we can only understand what we find in the work of Scotus Erigena,3 Johannes Scotus Erigena c.810-877. Irish philosopher and theologian, one of the most notable thinkers of the Carolingian Middle Ages. His principal work De divisione naturae was burnt by Pope Honorius in Paris in 1225. who brought over from the island of Ireland what he later expressed in his De divisione naturae, if we take it as a tradition arising out of a geosophical view. For in the fifth post-Atlantean period, which was in preparation then and which began in the fifteenth century, geosophy, too, paled. There then began the era in which human beings lost their inner connection with, and experience of, the universe. Geosophy is transformed, we might say, into geology. This is meant in the widest possible sense and comprises not only what today's academic philosophy means by the term. Cosmosophy was transformed into cosmology. Philosophy was retained but given an abstract nature—which in reality ought to be called philology, had this term not already been taken to denote something even more atrocious than anything one might like to include in philosophy.

There remains religion, which is now totally removed from any real knowledge and basically assumed by people to be nothing more than tradition. People of a nature capable of being creatively religious are no longer a feature of civilized life in general in this fifth post Atlantean period. Look at those who have come and gone. None have been creatively religious in the true sense of the word. And this is only right and proper. In the preceding epochs, in the first, second third and fourth post-Atlantean periods, there were always those who were creatively religious, personalities who were creative in the realm of religion, for it was always possible to bring down something from the cosmos, or at least to bring something up out of the realm of the earth. So in the Greek Mysteries—those called the Chthonian Mysteries in contrast to the heavenly Mysteries—which brought up their inspiration out of the depths of the earth in various ways—in these Mysteries geosophy was chiefly brought into being.

By entering into the fifth post-Atlantean period and standing full within it, human beings were thrown back upon themselves. The now made manifest what came out of themselves, ‘-logy ‘, the lore the knowledge out of themselves. Thus knowledge of the universe becomes a world of abstractions, of logical concepts, of abstract ideas. Human beings have lived in this world of abstract ideas since the fifteenth century. And with this world of abstract ideas, which they summarize in the laws of nature, they now seek to grasp out of themselves what was revealed to human beings of earlier times. It is quite justified that this age no longer brings forth any religiously creative natures, for the Mystery of Golgotha falls in the fourth post-Atlantean period, and this Mystery of Golgotha is the final synthesis of religious life. It leads to a religion that ought to be the conclusion of earthly religious streams and strivings. With regard to religion, all subsequent ages can really only point back to this Mystery of Golgotha.

So the statement, that since the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean period it is no longer possible for religiously productive individuals to appear, is not a criticism or a reprimand aimed at historical development. It is a statement of something positive because it can be justified by the occurrence of the Mystery of Golgotha.

In this way we conjure up before our eyes the course of human evolution with regard to spiritual streams and spiritual endeavours. In this way we can see how it has come about that we stand today in the midst of something that is, basically, no longer connected with the world about us but has come out of the human being, something in which the human being is productive and must become ever more productive. By further developing all these abstract things human beings will ascend once more through Imaginations to a kind of geosophy and cosmosophy. Through Inspiration they will deepen cosmosophy and ascend to a true philosophy, and through Intuition they will deepen philosophy until they can move towards a truly religious view of the world which will once more be able to unite with knowledge.

It is necessary to say that today we are only in the very first, most elementary beginnings of this progress. Since the final third of the nineteenth century there has shone into the earthly world from the spiritual world something which we can take to be a giving-back of spiritual revelations. But even with this we stand at the very beginning, a beginning which gives us a picture with which to characterize the attitude brought by external, abstract culture towards the first concrete statements that come from the spiritual world. When the representatives of current recognized knowledge hear what we have to say about the spiritual world, the understanding they bring to bear on what we say is of a kind that it can only be called a non-understanding. For it can be compared with the following: Suppose I were to write a sentence on this piece of paper, and suppose someone were to try to understand what I had written down by analysing the ink in which it is written. When our contemporaries write about Anthroposophy it is like somebody analysing the ink of a letter he has received. Again and again we have this impression. It is a picture very close to us, considering that we took our departure from a description of how, for human beings, in early post-Atlantean times even the starry constellations and starry movements were no more than a written expression for what they experienced as the spiritual population of the universe.

Such things are said today to a certain number of people in order to give them the feeling that Anthroposophy is not drawn from some sort of fantastic underworld but from real sources of knowledge, and that it is therefore capable of understanding the human beings of the earth to the very roots of their nature. Anthroposophy is capable of throwing light on today's differentiation of human beings into those of the West, of the middle realm and of the East, in the way mentioned yesterday. It is also capable of throwing light on differentiations which have existed in human evolution during the course of time. Only by connecting everything we can know about the differentiations according to regions of the earth with what we can know about how all this has come about can we gain an understanding of what kind of human beings inhabit our globe today.

Traditions of bygone ages have always been preserved, in some regions more, in others less. And according to those traditions the peoples of this globe are distinguished from one another. Looking eastwards we find that in later ages something was written down which during the first post-Atlantean period had existed unwritten, something which shines towards us out of the Vedas and their philosophy, something which touches us with its intimacy in the genuine philosophy of yoga. Letting all this work on us in our present-day consciousness, we begin to sense: If we immerse ourselves ever more deeply in these things, then we feel that even in the written works something lives of what existed in primeval times. But we have to add: Because the eastern world still echoes of its primeval times it is unsuited to receiving new impulses.

The western world has fewer traditions. At most, certain traditions stemming from the third post-Atlantean period, the age of cosmosophy, are contained in the writings of some secret orders. But they are traditions which are, no longer understood and are only brought before human beings in the form of incomprehensible symbols. But at the same time there is in the west an elemental strength capable of unfolding new impulses for development.

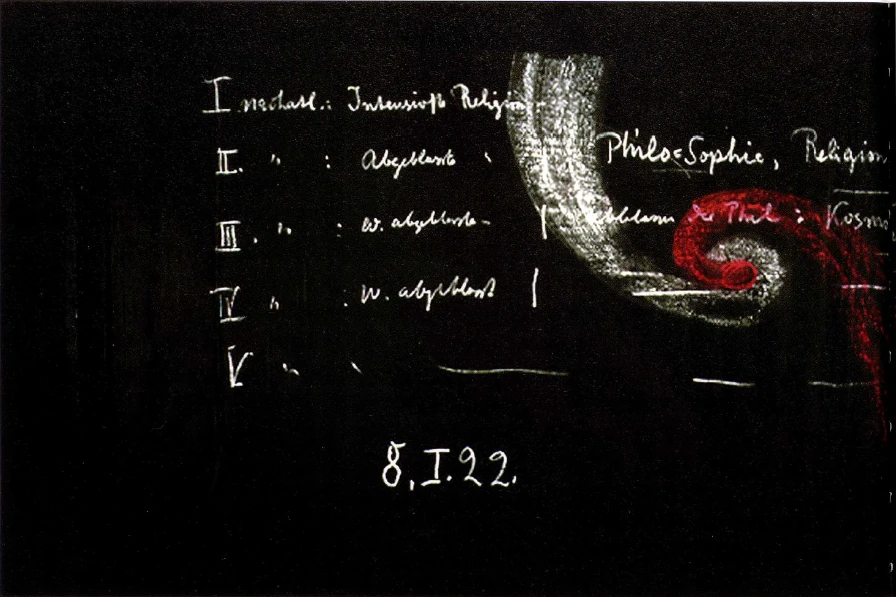

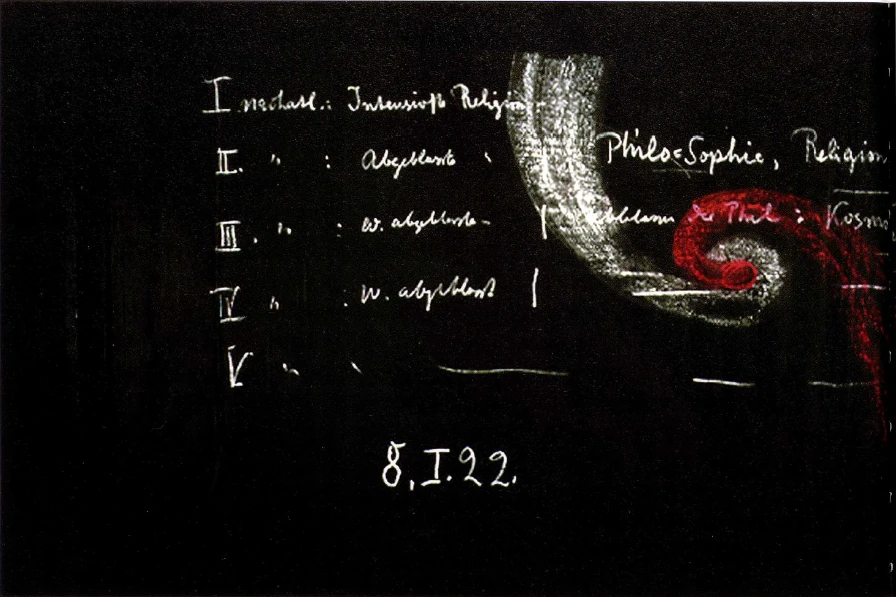

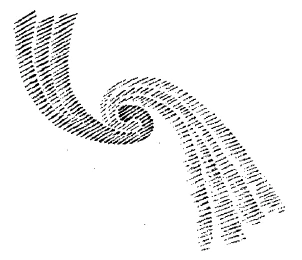

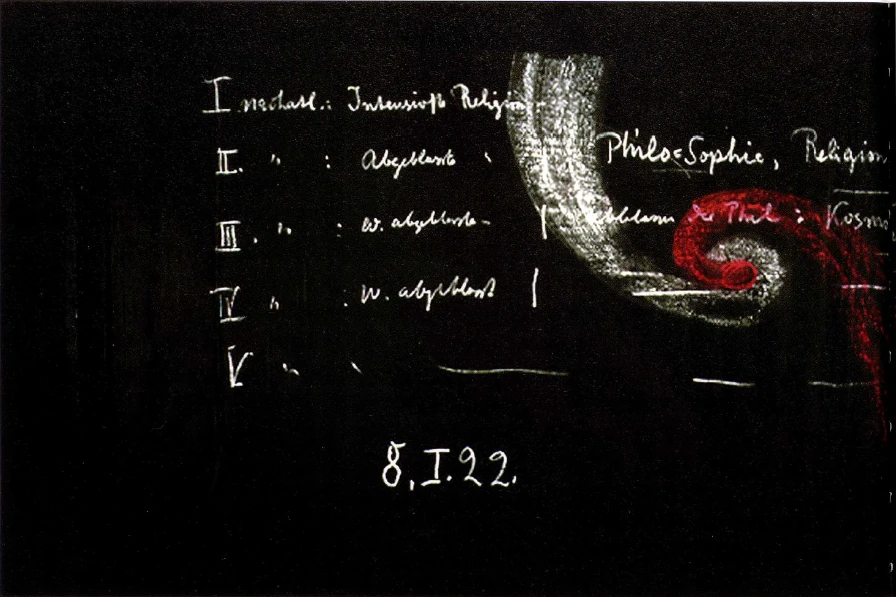

We might say that originally the primeval impulses existed. They developed by becoming ever weaker and weaker until, by about the fourth post-Atlantean period, they so to speak lost themselves in themselves, in what became Greek culture as such. Out of that, pointing towards the new, developed the abstract, prosaic sober culture of the Romans. (The lecturer draws on the blackboard). But this in turn must take spirituality into itself; it must, by becoming ever stronger and stronger, be filled with inner spirituality. Here, then, we have the symbol of the spiralling movement of humanity's impulses throughout the ages.

This symbol has always stood for important matters in the universe. If we have to speak of an atomistic world, we should not imagine it in the abstract way common today. We should imagine it in the image of this spiral, and this has often indeed been done. But on the greatest scale, too, we have to see this spiralling movement. Today I consider that we have arrived at it in a perfectly elementary manner by way of a concrete consideration of the course of human spiritual evolution.

Die Entwicklung des religiösen Lebens in den nachatlantischen Kulturen

[ 1 ] Wir wollen heute von einem andern Gesichtspunkte aus, als das gestern geschah, die Differenzierung innerhalb der Menschheit betrachten, und zwar heute von einem historischen Gesichtspunkte aus. Wir wollen einmal mit dem ausgesprochenen Ziel, das Verständnis für die Gegenwart zu fördern, die menschliche Entwickelung von dem Zeitpunkte an betrachten, unmittelbar nachdem die atlantische Katastrophe vorüber war. Wenn wir innerhalb der menschlichen Evolution überhaupt von Zivilisationsentwickelung sprechen, haben wir dann die erste maßgebliche Entwickelungsperiode dieser Art zu suchen in der alten indischen Kulturepoche. Und da finden Sie in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» von einem gewissen Gesichtspunkte aus eine Charakteristik dieser besonderen Kulturart, welche die des uralten Indiens war, jener Kulturart, von der in den mit Recht bewunderten Veden und in der mit Recht bewunderten altindischen Philosophie nur noch Nachklänge vorhanden sind, denn es gibt keine geschriebenen Urkunden aus dem, was in dieser Beziehung als indische Kultur genannt wird. Wenn wir unsere heutigen Worte gebrauchen, so müssen wir diese uralt indische Kultur bezeichnen als eine im eminentesten Sinne religiöse Kultur. Aber wir werden dann trotzdem mit dieser Bezeichnung nur das Richtige treffen, wenn wir uns über das, was eigentlich gemeint ist, mehr aussprechen.

[ 2 ] Das religiöse Element dieser uralt indischen Kultur war ein solches, daß es zu gleicher Zeit alles umfaßt hat, was wir von unserem heutigen Gesichtspunkte aus in Wissenschaft und Kunst anerkennen. Das gesamte Geistesleben des vollen Menschen wurde umfaßt von dieser Kultur, die wir, weil es trotzdem die treffendste Bezeichnung ist, als eine religiöse Kultur bezeichnen müssen. Diese religiöse Kultur erzeugt in den Menschen das Gefühl, daß sie in den Tiefen ihres Wesens verbunden sind mit einer göttlich-geistigen Welt. Und dieses Gefühl wurde in einer so intensiven Weise ausgebildet, daß das ganze Leben eigentlich durchleuchtet war von ihm, daß die helleren Bewußtseinszustände des Menschen, die unsere Wachzustände vorbereiteten, und auch seine traumhaften Zustände, die sich dann in unser chaotisches Traum- oder Schlafleben in der weiteren Evolution verloren haben, daß diese beiderlei Zustände durchzogen waren von diesem intensiven Bewußtsein der Verbindung des Menschlichen mit einem Göttlich-Geistigen.

[ 3 ] Aber wir dürfen nur diese allgemeine Charakteristik des Religiösen von unseren Begriffen hernehmen. Denn unsere Begriffe verführen uns zu stark dazu, das Religiöse als etwas Allgemeines, als etwas von dem übrigen Leben in einer gewissen Weise abstrakt Ferneliegendes zu betrachten. Bei denjenigen Menschen, von denen wir hier sprechen, war das Religiöse so, daß sie in den Inhalten, die sie mit dem Religiösen verbanden, zu gleicher Zeit ganz bestimmte Bilder, also ein bildhaftes Wissen hatten von dem Wesen des Menschen, und daß sie ein ausgebreitetes bildhaftes Wissen hatten von dem Bau des Weltenalls.

[ 4 ] Wir müssen uns allerdings vorstellen, daß dasjenige, was in der Weltanschauung dieser Menschen an bildhaftem Wissen von dem Bau des Weltenalls lebte, sich in keiner Weise vergleichen läßt mit dem, was wir etwa heute in unseren astronomischen oder astrophysischen Kenntnissen haben. In diesen astronomischen und astrophysischen Kenntnissen haben wir eine Art Mechanismus des Weltenalls. Die alte indische Bevölkerung hatte ein Weltenall, das in den bildhaften Vorstellungen dieser Menschen bewohnt war von göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten. Von irgendwelchen in äußerlichen, bloß mechanischen Formeln auszusprechenden Beziehungen von Gestirnen und von Bewegungen von Gestirnen in unserem Sinne konnte eigentlich noch nicht die Rede sein. Wenn diese Menschen aufblickten zum gestirnten Himmel, dann war es ja für sie so, daß sie in den äußeren Sternkonstellationen und Sternbewegungen nur etwas sahen, was ihnen in ihrem bildhaften Bewußtsein gut bekannt war, was sie schauten. Es war etwa so, daß man die Sache in der folgenden Art charakterisieren kann:

[ 5 ] Nehmen wir an, wir haben irgendwo eine reichbelebte Szene gesehen, in der Menschen sich getummelt haben, in der Menschen allerlei verrichtet haben. Wir waren etwa Teilnehmer irgendeines Festes, bei dem man mancherlei vollbracht hat. Wir gehen nach Hause. Am nächsten Tag bekommen wir eine Zeitung mit einem Bericht über dieses Fest, das wir selbst gesehen haben. Wir lassen unseren Blick fallen auf die toten Buchstaben, deren Bedeutung wir allerdings kennen, und die, wenn wir sie lesend verbinden, uns einen schwachen, abgeblaßten Begriff geben von dem, was wir in aller Lebendigkeit am vorhergehenden Tage erlebt haben. So etwa war das, was in dieser uralten indischen Zeit von den Menschen in ihrem instiktiven Schauen erfaßt worden war, und im Verhältnis dazu dasjenige, was sie in den Sternkonstellationen und Sternbewegungen sahen. Diese Sternkonstellationen und Sternbewegungen waren eben nur Schriftzeichen, man könnte sagen blasse Schriftzeichen. Und wenn sie diese Schriftzeichen etwa, sagen wir nur abgemalt hätten und auf Papier gehabt hätten, so würden sie das durchaus als eine bloße Schrift über die Wirklichkeit empfunden haben.

[ 6 ] Was für das Schauen dieser Menschen hinter diesen Schriftzeichen war, für das entwickelten sie nicht nur eine vorstellungsgemäße Erkenntnis, sondern zu gleicher Zeit ein liebendes Gefühl. Sie konnten das, was sie da in Bildern über das Weltenall erfaßten, nicht etwa bloß mit gleichgültigen Vorstellungen aufnehmen, sondern sie entwickelten dafür ein lebendiges Gefühl. Und zu gleicher Zeit entwickelten sie dafür etwas, was man nennen könnte ein ständiges Empfinden, daß alles, was sie taten, auch die kompliziertesten Handlungen, ein Ausdruck des vom göttlich-geistigen Wesen erfüllten Kosmos waren. Der Mensch fühlte seine Glieder durchdrungen von diesem göttlich-geistigen kosmischen Wesen. Er fühlte seinen Verstand durchdrungen von diesem göttlich-geistigen Wesen, seinen Mut und seinen Willen. So daß der Mensch eben auch sagen konnte, wenn er von seinen eigenen Handlungen sprach: Göttlich-geistige Wesen tun das. - Und da in jenen alten Zeiten die Menschen sehr wohl wußten, daß unter diesen göttlich-geistigen Wesen auch Luzifer und Ahriman sind, so waren sie sich eben auch bewußt, daß, indem Göttlich-Geistiges in ihnen waltete, sie auch das Böse neben dem Guten tun konnten. [Während der folgenden Seiten wird an die Tafel geschrieben. Siehe dazu das Schema am Ende des Vortrages.]

[ 7 ] Ich möchte mit dieser Auseinandersetzung eine Vorstellung davon hervorrufen, wie den ganzen Menschen erfüllend und den ganzen Menschen in Zusammenhang bringend mit der Fülle des Kosmos diese kosmische Religion beschaffen war, die eine kosmische Weisheit, aber auch zu gleicher Zeit eine den Menschen offenbarende Weisheit war. Und gerade darin besteht der Fortschritt in der Entwickelung der Menschheit, daß nun vor allen Dingen zunächst das allerintensivste religiöse Gefühl abblaßte. Gewiß, Religion blieb für alle späteren Zeiten, aber die Intensität des religiösen Lebens, wie es in diesen ersten indischen Zeiten vorhanden war, die blaßte ab. Vor allen Dingen blaßte zuerst die Empfindung ab für das Darinnenstehen mit seinen Handlungen, mit seinen Willensimpulsen, im Bereich der göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten. Nicht etwa, als ob der Mensch in der urpersischen Zeit, also in der zweiten nachatlantischen Kulturperiode, dieses Gefühl des Darinnenstehens gar nicht mehr gehabt hätte. Er hat es gehabt, nur abgeblaßt war es. In der ersten Zeit der nachatlantischen Kulturentwickelung war dieses Gefühl etwas Selbstverständliches. In der zweiten nachatlantischen Kulturblüte, in der urpersischen Zeit, blaßte eben das tiefste, das intensivste Religiöse ab, und der Mensch mußte schon beginnen, aus sich heraus etwas zu entwickeln, um in einer mehr aktiven Weise, als das zunächst der Fall war, seine Verbindung mit dem kosmisch Göttlich-Geistigen zu erfassen. So daß man sagen könnte: In der ersten nachatlantischen Zeit hatte man die intensivste Religion, und man hatte in der zweiten nachatlantischen Zeit eine abgeblaßte Religion, aber der Mensch mußte innerlich aktiv etwas entwickeln, was ihn wieder verbindet mit den kosmisch-geistig-seelischen Wesenheiten.

[ 8 ] Wenn wir heute ein Wort dafür anwenden wollen, so können wir aus dem Bereich der Worte, die uns bekannt sind, ein Wort wählen, das allerdings erst später geprägt worden ist. Aber wir nehmen es eben doch aus einer Zeit, in der man noch ein Bewußtsein von dem hatte, was eigentlich einmal in Urzeiten in der Menschheitsentwickelung vorhanden war. Wenn der Urinder hinaufschaute zum Himmel, dann empfand er überall einzelne Wesenheiten, diese oder jene göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten nebeneinander, sozusagen eine Bevölkerung von göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten. Das war abgeblaßt und, man möchte sagen was individualisiert war, was als einzelne göttlichgeistige Wesenheiten da war, das blaßte so ab, daß es im allgemeinen wie ein geistiger Kosmos war. Man könnte es sich auch unter dem folgenden Bilde vorstellen: Denken Sie sich einmal, Sie sehen meinetwillen einen Vogelschwarm ganz in der Nähe. Sie sehen einzelne Vögel. Diese entfernen sich immer weiter und weiter, und es wird eine schwarze Masse, es wird ein einheitliches Gebilde. So wurde der göttlich-geistige Kosmos, indem sich die Menschen von ihm geistig entfernten, ein einheitliches, in sich verschwommenes Gebilde.

[ 9 ] Noch die Griechen hatten gewissermaßen ein Nachgefühl davon, daß so etwas eben doch der menschlichen Betrachtung einmal zugrunde gelegen hatte. Daher nahmen sie in ihre Sprache herein das Wort «Sophia». Was als ein göttlich-geistiger Kosmos vorhanden war, das ergoß sich einst in den Menschen selbstverständlich, nahm der Mensch selbstverständlich hin. Dem, was jetzt, man möchte sagen, unter geistiger Entfernung in dieser Vereinheitlichung gesehen wurde, dem mußte man etwas von innen entgegenbringen. Und das bezeichneten dann die Griechen, die noch ein Gefühl davon hatten, mit dem: Ich liebe = philo.- So daß man sagen kann, in dieser zweiten nachatlantischen Periode, in der urpersischen Periode, war bei den Eingeweihten an der Stelle des alten ungeteilten Religiösen eine Zweiheit vorhanden: Philosophie, Religion. Die Philosophie hatte man sich errungen. Die Religion war das Überlieferte, aber das in der Überlieferung abgeblaßt Gewordene.

[ 10 ] Wenn wir weiter vorrücken zu der dritten nachatlantischen Periode, so kommen wir zu einem weiteren Abblassen des Religiösen. Wir kommen aber auch zu einem Abblassen der Philosophie, und wir müssen uns den konkret-realen Vorgang in der folgenden Weise vorstellen: Während in der urpersischen Zeit durchaus dieses Einheitsgebilde der kosmischen Wesenheiten vorhanden war und empfunden wurde als das den Weltenraum durchziehende Licht, das Urlicht, die Ur-Aura, Ahura Mazdao, kamen jetzt die Menschen, indem sie sich noch weiter entfernten von dieser Anschauung, dazu, schon in einer gewissen Weise den Gang der Sterne, die Konstellation der Sterne mehr in Betracht zu ziehen, nicht mehr in erster Linie zu empfinden das wesenhafte Göttlich-Geistige dahinter, sondern mehr zu empfinden die Schrift. Und daraus entstand dann etwas, was wir in der chaldäischen Weisheit, in der ägyptischen Weisheit, in zwei verschiedenen Formen haben. Es entstand dasjenige, was in sich schloß eine Erkenntnis über die Sternkonstellation, über die Sternbewegungen. Aber die innere Aktivität des Menschen war noch bedeutsamer geworden. Der Mensch mußte jetzt seine Liebe nicht nur verbinden mit dieser göttlichen Sophia, die als das Urlicht die Welt durchglänzte, sondern der Mensch mußte verbinden sein eigenes Schicksal, seine eigene Stellung in der Welt mit dem, was da in einer Weltenschrift durch die Sternkonstellation und durch die Sternbewegungen zu schauen war innerhalb des Kosmos. Und dasjenige, was jetzt neu errungen wurde, war daher eine Kosmo-Sophia. Diese Kosmosophie enthielt zwar noch durchaus den Hinweis auf die göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten, aber man sah schon mehr das, was nur der kosmische Schriftausdruck für die Taten dieser Wesenheit ist. Und daneben blieb eben wiederum abgeblaßt das, was Philosophie und was Religion war.

[ 11 ] Wenn wir dies verstehen wollen, dann müssen wir uns eben klar sein darüber, daß das, was wir heute noch Philosophie nennen, natürlich nur ein ganz schwaches, abgeblaßtes Schattenbild ist von dem, was etwa in den Mysterien der dritten nachatlantischen Epoche noch als etwas Lebendigeres empfunden wurde, was dann die Griechen in einer weiteren Abblassung Philosophie genannt haben. Wenn wir aber die dritte nachatlantische Epoche betrachten, so sehen wir überall in deren Kultur diese drei Glieder des menschlichen Geisteswesens ausgesprochen: eine Kosmosophie, eine Philosophie, eine Religion. Und wir bekommen nur die rechten Vorstellungen davon, wenn wir uns zu sagen wissen, daß bis in diesen Zeitpunkt hinein die Menschen so lebten, daß sie eigentlich mit ihrer Seele mehr außer dem Irdischen als im Irdischen lebten. Wenn wir von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus zum Beispiel die ägyptische Kultur betrachten - bei der chaldäischen war es noch ausgesprochener -, so sehen wir sie nur in richtiger Weise, wenn wir uns sagen: Ja, diejenigen Menschen, die überhaupt Anteil hatten an dieser Kultur, die verfolgten mit innigem Anteil, wenn der Abend herankam, die Konstellation der Gestirne. Sie erwarteten zum Beispiel gewisse Erscheinungen des Sirius, sie sahen sich die Planetenkonstellationen an, und sie bezogen das, was sie da anschauen konnten, darauf, wie ihnen der Nil dasjenige gab, was sie zu ihrem irdischen Leben brauchten. Aber sie sprachen eigentlich nicht in erster Linie von dem Irdischen. Dieses Irdische war ihnen ein Feld ihrer Arbeit. Aber wenn sie über das Feld sprachen, das sie bearbeiteten, so sprachen sie eigentlich so darüber, daß sie es anschauten als in Beziehung stehend zu dem Außerirdischen. Und sie bezeichneten die verschiedenen Gestaltungen, welche der von ihnen bewohnte Erdenfleck im Laufe der Jahreszeiten annahm, nach dem, wie die Gestirne sich in diesen aufeinanderfolgenden Jahreszeiten offenbarten. Sie beurteilten die Erde nach dem Himmel. Der Tag war ihnen etwas, das ihnen vom seelischen Standpunkte aus eigentlich Dunkelheit entgegenbrachte. Und Helligkeit kam in diese Dunkelheit hinein, wenn sie das, was der Tag brachte, deuten konnten aus dem, was sie erschauen konnten in der Nacht am gestirnten Himmel.

[ 12 ] Was die Leute in der damaligen Zeit empfanden, würde man etwa so aussprechen:

O dunkel ist der Erde Antlitz

Wenn die Sonne blendend dunkel:

Doch hell wird mir mein Tagefeld

Wenn die Seele es beleuchtet durch Sternenweisheit

[ 13 ] Wenn man einen solchen Satz aufschreibt, so kann man in ihm empfinden, wie eigentlich die Gefühlswelt dieser dritten nachatlantischen Periode war. Und man bekommt vielleicht gerade von einer solchen Betrachtung aus ein Gefühl davon, wie diejenigen Menschen, die noch darinnenstanden in den Nachklängen eines solchen Empfindens, zu den späteren Griechen, zu den Angehörigen der vierten nachatlantischen Kulturperiode sagen konnten: Eure Anschauung der Welt, euer ganzes Leben ist kindlich, denn ihr wißt eigentlich nur noch etwas von der Erde. Eure Vorfahren in alten Zeiten haben gewußt, die Erde mit dem Licht des Himmels zu beleuchten, ihr aber lebt im Dunkel der Erde.

[ 14 ] Allerdings empfanden die Griechen schon dieses Dunkel der Erde als hell. Die Griechen hatten schon durchaus die Tendenz, die Kosmosophie allmählich zu überwinden und sie zu verwandeln. Und indem alles das, was von den Himmelsweiten hereinschaute, noch weiter abgeblaßt wurde, hatten sie schon die Kosmosophie in eine Geosophie verwandelt. Und die Kosmosophie war für sie eigentlich nur eine Tradition. Sie war für sie etwas, was sie lernen konnten, wenn sie zurückblickten zu denen, die ihnen das Entsprechende überlassen hatten.

[ 15 ] So etwa stand Pythagoras, man möchte sagen an der Schwelle des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitalters, indem er herumzog bei den Ägyptern, Chaldäern und weiter hinein nach Asien, um da aufzunehmen, was diese Menschen noch ihm überliefern konnten von der Weisheit, die ihre Urväter in den Mysterien als ihre Kosmosophie, als ihre Philosophie, als ihre Religion gehabt hatten. Und dasjenige, was dann noch verstanden werden konnte, war dann eben Kosmosophie, Philosophie, Religion.

[ 16 ] Nur war diese Geosophie der Griechen - das beachtet man heute viel zu wenig — doch noch in bezug auf das Irdische ein solches Wissen, eine solche Weisheit, daß der Mensch wirklich sich verbunden fühlte mit der Erde, und daß dieses Verbundensein mit der Erde einen durchaus seelischen Charakter hatte. Bei dem gebildeten Griechen hatte das Verbundensein mit der Erde einen seelischen Charakter. Die besondere Art, welche die Griechen hatten, Quellen zu beleben mit Nymphen, den Olymp zu beleben mit den Göttern - kurz, alles das als eine Lebensanschauung auszubilden, was nicht auf eine Geologie hinweist, wo man nur mit Begriffen die Erde umspannt, sondern auf eine Geosophie, wo eben Wesenhaftes in der Erde erlebend erkannt und erkennend erlebt wird - das war etwas, was die heutige Menschheit nur noch in der Abstraktion kennt, was aber noch durchaus lebendig war bis in das vierte nachchristliche Jahrhundert herein.

[ 17 ] Bis in das vierte nachchristliche Jahrhundert herein hatte man noch etwas von einer solchen Geosophie. Und auch von dieser Geosophie blieb noch einiges in der Tradition erhalten. Was wir bei Scotus Eriugena finden zum Beispiel, der von der irischen Insel und deren Mysterien das mitgebracht hatte, was er dann in seiner Schrift «Über die Teilung der Natur» zum Ausdrucke gebracht hat, das kann nur verstanden werden, wenn man das, was sich als das Ergebnis einer solchen Tradition ergibt, aus einer Geosophie heraus auffaßt. Denn in der fünften nachatlantischen Periode, die sich dann vorbereitete und die mit dem 15. Jahrhundert heraufkam, blaßte auch diese Geosophie ab, und was jetzt kam, das war, daß der Mensch eigentlich verloren hatte das innerliche Miterleben mit dem Weltenall. Geosophie verwandelte sich, möchte man sagen, in Geologie. Das ist im weitesten Sinne zu fassen, nicht nur wie die heutige Schulphilosophie das meint. Kosmosophie verwandelte sich in Kosmologie; Philosophie behielt man bei, machte aber ein abstraktes Wesen daraus, das eigentlich in Wahrheit Philologie genannt werden müßte, wenn nicht der Name schon in Anspruch genommen wäre von etwas noch viel Greulicherem, als man in der Philosophie haben möchte.

[ 18 ] Es blieb dasjenige übrig, was Religion ist, was schon ganz abseits steht von der eigentlichen Erkenntnis, was im Grunde genommen von dem Menschen nur noch aus den Traditionen angenommen wird. Denn religionsschöpferische Naturen treten in dieser fünften nachatlantischen Periode nicht mehr im allgemeinen Zivilisationsleben auf. Betrachten Sie alles, was da kam: religionsschöpferische Naturen im eigentlichen Sinne des Wortes waren nicht mehr da. Aber das hat ja auch seine Berechtigung. In den Zeiträumen vorher, in der ersten, zweiten, dritten, vierten nachatlantischen Periode gab es immer religiös schöpferische Naturen, religionsschöpferische Persönlichkeiten, denn es konnte noch immer etwas hereingeholt werden aus dem Kosmos, oder wenigstens konnte noch etwas heraufgeholt werden aus der Erde. Und in den griechischen Mysterien, in denjenigen Mysterien, die man im Gegensatze zu den Himmelsmysterien die chthonischen Mysterien nennt, die aus den Tiefen der Erde heraufholten ihre Inspiration auf die verschiedenste Weise, in diesen Mysterien kam vorzugsweise die Geosophie zustande.

[ 19 ] Mit dem Hineingehen in die fünfte nachatlantische Periode und dann mit dem Darinnenstehen in diesem Zeitabschnitt wurde der Mensch auf sich selbst zurückgewiesen. Er brachte die «Logie», er brachte dasjenige, was nun aus ihm selbst herauskommt, zum Vorschein, zur Offenbarung. Und so wird die Welterkenntnis eine Welt der abstrakten, der logischen Begriffe, eine Welt der abstrakten Ideen. In dieser Welt der abstrakten Ideen lebt der Mensch seit dem 15. Jahrhundert. Mit dieser Welt der abstrakten Ideen, die er dann zusammenrechnet in die Naturgesetze, sucht er jetzt von sich aus dasjenige zu erfassen, was dem früheren Menschen sich geoffenbart hat. Daß es in dieser Periode nicht mehr religionsschöpferische Naturen gibt, hat eine gewisse Berechtigung, denn es fällt in den vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum das Mysterium von Golgatha, und dieses Mysterium von Golgatha gibt die letzte Synthesis des religiösen Lebens. Das gibt diejenige Religion, die der Abschluß der irdischen Religionsströmungen und -strebungen sein sollte. Und in religiöser Beziehung können eigentlich alle folgenden Zeiten nur auf dieses Mysterium von Golgatha zurück weisen.

[ 20 ] Indem also gesagt wird, daß seit der fünften nachatlantischen Kulturzeit nicht eigentlich mehr religiös produktive Naturen auftreten können, wird damit nicht etwas Tadelndes, etwas Kritisches gegenüber der Geschichtsentwickelung gesagt, sondern es wird etwas gesagt, was gerade etwas Positives ist, weil es sich durch das Auftreten des Mysteriums von Golgatha rechtfertigen läßt.

[ 21 ] So können wir uns den Gang der Menschheitsentwickelung in Bezug auf die geistigen Strömungen und die geistigen Bestrebungen vor Augen stellen. So können wir sehen, wie es dazu gekommen ist, daß wir heute drinnenstehen in dem, was im Grunde genommen nicht mehr einen Zusammenhang mit der Umwelt hat, sondern was etwas aus dem Menschen Herausgesponnenes ist, aber etwas, in dem der Mensch doch produktiv ist und immer mehr produktiv werden muß. Denn indem er dieses Abstrakte weiter ausbildet, wird er eben durch Imagination wiederum zu einer Art Geosophie und Kosmosophie aufrücken. Er wird durch die Inspiration die Kosmosophie vertiefen und zu einer wahren Philosophie aufrücken, und er wird dann durch Intuition die Philosophie vertiefen und zu einer wirklich religiösen Weltauffassung, die nun auch mit der Erkenntnis wiederum eins sein kann, vorrücken können.

[ 22 ] Man möchte sagen, daß wir eigentlich heute erst im Allerelementarsten dieses Fortschrittes stecken. Selbst mit dem, was wir nun heute schon fassen können als eine Wiedergabe von geistigen Offenbarungen, die ja seit dem letzten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts aus der geistigen Welt in die irdische hereinleuchten und in dieser Idee aufgefaßt und empfangen werden konnten, selbst damit stehen wir eigentlich im Anfange, in einem Anfange, der einem ein Bild aufdrängt, welches charakteristisch sein kann für die Auffassung, die heute von der äußeren, ganz abstrakten Kultur den ersten konkreten Äußerungen und Mitteilungen aus der geistigen Welt entgegengebracht wird. Wenn man heute über die geistige Welt spricht, und die anerkannte Erkenntnis hört das in ihren Vertretern, dann wird diesen Auseinandersetzungen über die geistige Welt eine solche Art des Verständnisses entgegengebracht, die man natürlich ein Unverständnis nennen muß. Denn was da entgegengebracht wird, läßt sich vergleichen mit dem Folgenden:

[ 23 ] Nehmen wir an, ich würde einen Satz hier aufschreiben, und derjenige, der dann das Stückchen Papier bekommt, würde, um zu einem Verständnis dessen zukommen, was ihm da gegeben worden ist, die Tinte analysieren. So etwa ist es, wenn unsere Zeitgenossen über Anthroposophie schreiben, wie wenn jemand, der einen Brief bekommt, die Tinte analysiert. Diesen Eindruck hat man immer. Dieses Bild kann einem eben naheliegen, wenn man ausgegangen ist von einer Betrachtung, daß ja selbst die Sternkonstellation und die Sternbewegung für die erste Menschheitsentwickelung in der nachatlantischen Periode nur etwas wie ein Schriftausdruck waren für das, was sie als die geistige Bevölkerung, möchte ich sagen, des Kosmos erlebte.

[ 24 ] Man stellt heute solche Dinge vor eine gewisse Zahl von Menschen hin, um doch ein Gefühl dafür hervorzurufen, daß dasjenige, was als Anthroposophie auftritt, nicht aus irgendwelchen phantastischen Untergründen geschöpft ist, sondern daß es geschöpft ist aus wirklichen Erkenntnisquellen, und daher sich als tauglich erweist, die Menschheit der Erde nach ihrer Wesenheit zu erkennen. Anthroposophie ist tauglich, Licht zu verbreiten über die Menschheitsdifferenzierung in unserer Gegenwart vom Westen durch die Mitte zum Osten hin, wie wir das gestern versucht haben. Sie ist aber auch tauglich, über diejenigen Differenzierungen Licht zu verbreiten, die im Laufe der Zeiten in der Menschheitsevolution aufgetreten sind. Und eigentlich erst dadurch, daß man alles das, was man über die Differenzierung der Erdengebiete in der Gegenwart wissen kann, mit dem verbindet, was man darüber wissen kann, wie das alles geworden ist, erst dadurch gewinnt man ein Verständnis dessen, was an Menschen heute lebt hier auf dem Erdenrund.

[ 25 ] Traditionen des Alten haben sich immer erhalten, auf dem einen Erdengebiete mehr, auf dem andern weniger. Auch nach diesen Traditionen unterscheiden sich die Völker des Erdballs. Wenn wir nach dem Osten hinüberblicken, finden wir ja, wie in der späteren Zeit - aufgezeichnet worden ist dasjenige, was unaufgezeichnet vorhanden war in der ersten nachatlantischen Kulturepoche, wie es uns entgegenglänzt in den Veden, in der Vedantaphilosophie, wie uns seine Innigkeit berührt in der echten Jogaphilosophie. Und wenn wir das alles auf uns wirken lassen vom Bewußtsein der Gegenwart aus, dann bekommen wir ein Gefühl: In diese Dinge muß man sich vertiefen, immer mehr und mehr vertiefen, dann fühlt man selbst in den Schriftwerken noch etwas leben von dem, was in den Urzeiten vorhanden war. Aber man möchte sagen: daß die morgenländische Welt noch innerhalb dieses lebendigen Nachklanges seiner Urweltweisheit lebt, das macht diese morgenländische Welt auch ungeeignet, neue Ansätze zu empfangen.

[ 26 ] Die westliche Welt hat weniger Traditionen. Höchstens in den Aufzeichnungen gewisser Geheimorden hat sie Traditionen aus der dritten nachatlantischen Kulturepoche, aus der Zeit der Kosmosophie, aber Traditionen, die nicht mehr verstanden werden, sondern in unverstandenen Symbolen vor die Menschheit hingebracht werden. Aber in diesem Westen ist zu gleicher Zeit vorhanden eine elementarische Kraft, neue Entwickelungsimpulse zur Entfaltung zu bringen.

[ 27 ] So daß man sagen könnte: Es waren einstmals die Urimpulse da. Sie entwickelten sich, indem sie immer schwächer und schwächer wurden, bis gegen den vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum hin, wo sie sich gewissermaßen in sich selbst verloren in dem eigentümlichen griechischen Kulturleben. Und heraus entwickelte sich dann, mit der Hinweisung auf ein Neues, die abstrakte, die prosaische Nüchternheit des Römertums (es wird gezeichnet). Das aber muß wiederum aufnehmen Geistigkeit und muß wiederum, indem es mächtiger und mächtiger wird, von innerlicher Geistigkeit durchdrungen werden. Und wir bekommen auf diese Weise dann, ich möchte sagen, symbolisch das, was wir als die wirbelnde Bewegung der Menschheitsimpulse durch die Zeitenfolge hindurch bezeichnen können.

[ 28 ] Solch eine Figur war ja immer eine Art Symbolum für Wichtigstes im Weltenall; und das ist sie auch. Wenn man schon von einer atomistischen Welt spricht, so muß man auch diese nicht so abstrakt vorstellen, wie das heute vielfach der Fall ist, sondern unter dem Bilde dieses Wirbels, was auch oftmals getan worden ist. Aber auch im Größten muß man diese Wirbelbewegung sehen. Und wir haben sie heute, wie ich glaube, in einer ganz selbstverständlich elementaren Weise aus einer konkreten Betrachtung des Ganges der menschheitlichen Geistesentwickelung heraus gewonnen.

[ 29 ] Das ist dasjenige, was ich Ihnen heute vorbringen wollte.

[ 30 ] Da ich wiederum vor einer Reise stehe, werden längere Zeit jetzt hier keine Vorträge sein. Die nächsten Vorträge werde ich Ihnen, meine lieben Freunde, wiederum ankündigen lassen.

The development of religious life in post-Atlantean cultures

[ 1 ] Today we want to look at the differentiation within humanity from a different perspective than we did yesterday, namely from a historical perspective. With the express aim of promoting understanding of the present, we want to look at human development from the point immediately after the Atlantic catastrophe. When we speak of the development of civilization within human evolution, we must look for the first decisive period of this kind in the ancient Indian cultural epoch. And there, in my “Outline of Secret Science,” you will find, from a certain point of view, a characterization of this special type of culture that was that of ancient India, that type of culture of which only echoes remain in the rightly admired Vedas and in the rightly admired ancient Indian philosophy, for there are no written records of what is called Indian culture in this connection. If we use our present-day words, we must describe this ancient Indian culture as a culture that was religious in the most eminent sense. But we will only be correct in using this description if we say more about what is actually meant.

[ 2 ] The religious element of this ancient Indian culture was such that it encompassed everything that we recognize today in science and art. The entire spiritual life of the whole human being was encompassed by this culture, which we must describe as a religious culture because it is still the most accurate term. This religious culture creates in human beings the feeling that they are connected in the depths of their being with a divine-spiritual world. And this feeling was developed in such an intense way that the whole of life was actually illuminated by it, that the brighter states of consciousness of human beings, which prepared our waking states, and also his dream states, which were then lost in our chaotic dream or sleep life in the further evolution, that both of these states were permeated by this intense consciousness of the connection between the human and the divine-spiritual.

[ 3 ] But we must only take this general characteristic of religion from our concepts. For our concepts tempt us too strongly to regard religion as something general, as something abstractly remote from the rest of life in a certain way. For the people we are talking about here, religion was such that in the content they associated with religion, they had at the same time very specific images, that is, a pictorial knowledge of the nature of human beings, and that they had an extensive pictorial knowledge of the structure of the universe.

[ 4 ] We must imagine, however, that what lived in the worldview of these people as pictorial knowledge of the structure of the universe cannot be compared in any way with what we have today in our astronomical or astrophysical knowledge. In this astronomical and astrophysical knowledge, we have a kind of mechanism of the universe. The ancient Indian population had a universe that was inhabited in the pictorial imagination of these people by divine-spiritual beings. There could not really be any talk of any relationships between stars and movements of stars in our sense, expressed in external, merely mechanical formulas. When these people looked up at the starry sky, they saw in the outer constellations and movements of the stars only something that was well known to them in their pictorial consciousness, something they were looking at. It was something like this, which can be characterized in the following way:

[ 5 ] Let us suppose that we have seen a lively scene somewhere, in which people were bustling about, doing all sorts of things. We were perhaps taking part in some kind of festival, where all kinds of things were happening. We go home. The next day we get a newspaper with a report about the festival we saw ourselves. We let our gaze fall on the dead letters, whose meaning we know, however, and which, when we connect them by reading, give us a faint, faded idea of what we experienced in all its liveliness the previous day. This was roughly what people in those ancient Indian times perceived in their instinctive vision, and in relation to this, what they saw in the constellations and movements of the stars. These constellations and movements of the stars were just written characters, one might say pale written characters. And if they had simply copied these characters and had them on paper, they would have perceived them as mere writing about reality.

[ 6 ] What lay behind these characters for these people, they developed not only a conceptual understanding, but at the same time a loving feeling. They could not simply accept what they perceived in images of the universe with indifference, but developed a living feeling for it. At the same time, they developed what could be called a constant awareness that everything they did, even the most complicated actions, was an expression of the cosmos filled with divine spirit. Human beings felt their limbs permeated by this divine-spiritual cosmic being. They felt their intellect permeated by this divine-spiritual being, their courage and their will. So that human beings could also say, when speaking of their own actions: Divine-spiritual beings do that. And since in those ancient times people knew very well that Lucifer and Ahriman were also among these divine-spiritual beings, they were also aware that, because the divine-spiritual reigned within them, they could also do evil alongside good. [During the following pages, something is written on the board. See the diagram at the end of the lecture.]

[ 7 ] With this discussion, I would like to give an idea of how this cosmic religion, which was a cosmic wisdom but at the same time a wisdom revealed to human beings, was capable of fulfilling the whole human being and bringing the whole human being into relationship with the fullness of the cosmos. And it is precisely in this that the progress in the development of humanity consists, that now, first of all, the most intense religious feeling has faded away. Certainly, religion remained for all later times, but the intensity of religious life as it existed in these early Indian times faded away. Above all, the feeling of being within the realm of divine-spiritual beings, with one's actions and impulses of will, faded first. It was not as if human beings in the original Persian period, that is, in the second post-Atlantean cultural period, no longer had this feeling of being within. They did have it, but it had faded. In the first period of post-Atlantean cultural development, this feeling was something taken for granted. In the second post-Atlantean cultural flowering, in the ancient Persian period, the deepest, most intense religious feeling faded, and human beings had to begin to develop something from within themselves in order to grasp their connection with the cosmic divine-spiritual in a more active way than had previously been the case. So one could say that in the first post-Atlantean period, people had the most intense religion, and in the second post-Atlantean period, religion faded, but human beings had to actively develop something within themselves that would reconnect them with the cosmic, spiritual, and soul entities.

[ 8 ] If we want to use a word for this today, we can choose one from the realm of words that are familiar to us, although it was coined later. But we take it from a time when people still had an awareness of what actually existed in the early stages of human development. When the primordial human being looked up at the sky, he perceived individual beings everywhere, this or that divine-spiritual being side by side, a population of divine-spiritual beings, so to speak. This faded away, and what had been individualized, what had been individual divine-spiritual beings, faded away so that in general it was like a spiritual cosmos. You could also imagine it in the following way: Imagine, for my sake, that you see a flock of birds very close by. You see individual birds. They move further and further away, and they become a black mass, a uniform structure. In this way, as human beings distanced themselves spiritually from the divine-spiritual cosmos, it became a unified, blurred structure.

[ 9 ] The Greeks still had a certain sense that something like this had once been the basis of human perception. That is why they adopted the word “Sophia” into their language. What existed as a divine-spiritual cosmos once poured forth into human beings as a matter of course, and human beings accepted it as a matter of course. What was now seen, one might say, as spiritual separation in this unification had to be countered with something from within. And the Greeks, who still had a sense of this, expressed it with: I love = philo. So that one can say that in this second post-Atlantean period, in the ancient Persian period, there was a duality among the initiated in place of the old undivided religion: philosophy and religion. Philosophy had been achieved. Religion was what had been handed down, but it had faded in the tradition.

[ 10 ] If we move on to the third post-Atlantean period, we come to a further fading of religion. But we also come to a fading of philosophy, and we must imagine the concrete, real process in the following way: While in the ancient Persian period this unified structure of cosmic beings definitely existed and was perceived as the light permeating the universe, the primordial light, the primordial aura, Ahura Mazdao, now, as people distanced themselves further from this view, they began to consider the course of the stars, the constellations, in a certain way, no longer perceiving primarily the essential divine-spiritual behind them, but rather perceiving the writing. And from this arose something that we have in two different forms in Chaldean wisdom and Egyptian wisdom. What arose was something that contained within itself a knowledge of the constellations and the movements of the stars. But the inner activity of human beings had become even more significant. Human beings now had to connect their love not only with this divine Sophia, who shone through the world as the primordial light, but they also had to connect their own destiny, their own position in the world, with what could be seen in a world script through the constellations and the movements of the stars within the cosmos. And what was now newly attained was therefore a cosmo-Sophia. This cosmosophy still contained references to divine-spiritual beings, but people were already seeing more of what is merely the cosmic expression of the deeds of these beings. And alongside this, what was philosophy and religion remained faded away.

[ 11 ] If we want to understand this, we must be clear that what we still call philosophy today is, of course, only a very weak, faded shadow of what was still perceived as something more alive in the mysteries of the third post-Atlantean epoch, which the Greeks then called philosophy in a further fading. But when we look at the third post-Atlantean epoch, we see these three elements of the human spirit expressed everywhere in its culture: a cosmosophy, a philosophy, and a religion. And we can only gain a correct understanding of them if we realize that, up until that point in time, human beings lived in such a way that their souls actually lived more outside the earthly realm than within it. If we look at Egyptian culture from this point of view, for example—it was even more pronounced in Chaldean culture—we can only see it correctly if we say to ourselves: Yes, those people who had any part in this culture watched the constellations of the stars with deep interest when evening came. They expected certain phenomena of Sirius, for example, they looked at the planetary constellations, and they related what they could see there to how the Nile gave them what they needed for their earthly life. But they did not actually speak primarily about the earthly. The earthly was a field of work for them. But when they spoke about the field they were working on, they actually spoke about it in such a way that they saw it as related to the extraterrestrial. And they described the various forms that the piece of earth they inhabited took on in the course of the seasons according to how the stars revealed themselves in these successive seasons. They judged the earth by the sky. The day was something that, from a spiritual point of view, actually brought darkness to them. And light came into this darkness when they could interpret what the day brought from what they could see in the night sky.

[ 12 ] What people felt at that time could be expressed something like this:

O dark is the face of the earth

When the sun is blindingly dark:

But my day becomes bright

When the soul illuminates it with the wisdom of the stars

[ 13 ] When one writes down such a sentence, one can sense what the emotional world of this third post-Atlantean period was actually like. And perhaps it is precisely from such a consideration that one gets a feeling of how those people who still stood in the aftermath of such a feeling could say to the later Greeks, to the members of the fourth post-Atlantean cultural period: Your view of the world, your whole life is childish, for you really know only something of the earth. Your ancestors in ancient times knew how to illuminate the earth with the light of heaven, but you live in the darkness of the earth.

[ 14 ] However, the Greeks already perceived this darkness of the earth as light. The Greeks already had a definite tendency to gradually overcome cosmosophy and transform it. And by further diminishing everything that shone in from the vastness of the heavens, they had already transformed cosmosophy into geosophy. And cosmosophy was really only a tradition for them. It was something they could learn by looking back to those who had left them the corresponding knowledge.

This was the position of Pythagoras, one might say, on the threshold of the fourth post-Atlantean age, as he traveled among the Egyptians, Chaldeans, and further into Asia to absorb what these people could still pass on to him of the wisdom that their forefathers had possessed in the mysteries as their cosmosophy, their philosophy, their religion. And what could then still be understood was precisely cosmosophy, philosophy, religion.[ 16 ] However, this geosophy of the Greeks — which is far too little appreciated today — was still such knowledge, such wisdom in relation to the earthly realm that human beings really felt connected to the earth, and that this connection with the earth had a thoroughly soul character. For educated Greeks, this connection with the earth had a spiritual character. The special way in which the Greeks animated springs with nymphs, animated Olympus with gods — in short, to develop into a worldview everything that does not point to a geology where one only encompasses the earth with concepts, but rather to a geosophy where the essential nature of the earth is experienced and recognized through experience—this was something that modern humanity knows only in abstraction, but which was still very much alive until well into the fourth century AD.

[ 17 ] Until well into the fourth century AD, something of this geosophy still remained. And some of this geosophy was preserved in tradition. What we find, for example, in Scotus Eriugena, who brought back from the island of Ireland and its mysteries what he then expressed in his writing “On the Division of Nature,” can only be understood if one understands what emerges as the result of such a tradition from a geosophical perspective. For in the fifth post-Atlantean period, which was then preparing and came to a head in the 15th century, this geosophy also faded away, and what came next was that human beings had actually lost their inner experience of the universe. Geosophy was transformed, one might say, into geology. This is to be understood in the broadest sense, not just as today's academic philosophy understands it. Cosmosophy was transformed into cosmology; philosophy was retained, but it was turned into an abstract entity that should really be called philology, if the name had not already been taken by something even more gruesome than one would like to have in philosophy.

[ 18 ] What remained was religion, which stands completely apart from actual knowledge and is basically only accepted by humans out of tradition. For religiously creative natures no longer appear in general civilized life in this fifth post-Atlantean period. Consider everything that came: religiously creative natures in the true sense of the word were no longer there. But that also has its justification. In the previous periods, in the first, second, third, and fourth post-Atlantean periods, there were always religiously creative natures, religiously creative personalities, because something could still be brought in from the cosmos, or at least something could still be brought up from the earth. And in the Greek mysteries, in those mysteries which, in contrast to the heavenly mysteries, are called the chthonic mysteries, which drew their inspiration from the depths of the earth in various ways, it was primarily geosophy that came into being.

[ 19 ] With the entry into the fifth post-Atlantean period and then with standing within this period, human beings were thrown back upon themselves. They brought forth “logia,” they brought forth what now comes out of themselves, into manifestation, into revelation. And so world knowledge becomes a world of abstract, logical concepts, a world of abstract ideas. Human beings have been living in this world of abstract ideas since the 15th century. With this world of abstract ideas, which they then calculate into the laws of nature, they now seek on their own to grasp what was revealed to earlier human beings. The fact that there are no longer any religion-creating natures in this period is justified to a certain extent, for the mystery of Golgotha falls into the fourth post-Atlantean period, and this mystery of Golgotha provides the final synthesis of religious life. This gives rise to the religion that was to be the conclusion of earthly religious currents and aspirations.

And in a religious sense, all subsequent periods can really only point back to this mystery of Golgotha.[ 20 ] So when we say that since the fifth post-Atlantean cultural epoch, religiously productive natures can no longer really appear, we are not saying anything critical or reproachful about the development of history. Rather, we are saying something that is actually positive, because it can be justified by the appearance of the Mystery of Golgotha.

[ 21 ] In this way we can visualize the course of human evolution in relation to spiritual currents and spiritual aspirations. In this way, we can see how it has come about that we now find ourselves in a situation that basically no longer has any connection with the environment, but is something that has been spun out of human beings, yet something in which human beings are productive and must become increasingly productive. For by further developing this abstract, they will, through imagination, advance to a kind of geosophy and cosmosophy. Through inspiration, he will deepen cosmosophy and advance to a true philosophy, and then, through intuition, he will deepen philosophy and advance to a truly religious worldview, which can now once again be one with knowledge.

[ 22 ] One might say that we are actually only at the very beginning of this progress today. Even with what we can already grasp today as a reproduction of spiritual revelations, which have been shining from the spiritual world into the earthly world since the last third of the 19th century and could be understood and received in this idea, even with that we are actually at the beginning, at a beginning that imposes on us an image that may be characteristic of the view that the external, entirely abstract culture today takes of the first concrete expressions and communications from the spiritual world. When one speaks today about the spiritual world, and hears the recognized knowledge expressed by its representatives, then these discussions about the spiritual world are met with a kind of understanding that must naturally be called incomprehension. For what is offered in response can be compared to the following:

[ 23 ] Let us suppose that I write down a sentence here, and the person who then receives this piece of paper, in order to understand what has been given to him, analyzes the ink. This is roughly what happens when our contemporaries write about anthroposophy, as if someone who receives a letter analyzes the ink. This is always the impression one gets. This image may seem obvious if one starts from the observation that even the constellations and movements of the stars were, for the first stage of human evolution in the post-Atlantean period, merely a written expression of what they experienced as the spiritual population, so to speak, of the cosmos.

[ 24 ] Today, such things are presented to a certain number of people in order to give them a feeling that what appears as anthroposophy is not drawn from some fantastical background, but is drawn from real sources of knowledge and therefore proves suitable for recognizing the essence of humanity on earth. Anthroposophy is suitable for shedding light on the differentiation of humanity in our present time from the West through the Middle to the East, as we attempted to do yesterday. But it is also suitable for shedding light on the differentiations that have occurred in the course of human evolution. And it is only by connecting everything we can know about the differentiation of the regions of the earth in the present with what we can know about how all this came about that we gain an understanding of what lives in human beings here on earth today.

[ 25 ] Traditions of the old have always been preserved, more in some regions of the earth than in others. The peoples of the globe also differ according to these traditions. When we look to the East, we find that what was unrecorded in the first post-Atlantean cultural epoch has been recorded in later times, shining out at us in the Vedas, in Vedanta philosophy, touching us with its depth in genuine yoga philosophy. And when we allow all this to sink in from the consciousness of the present, we get a feeling: one must delve deeper and deeper into these things, then one feels even in the written works something still alive of what existed in primeval times. But one would like to say that the fact that the Eastern world still lives within this living echo of its primordial world wisdom also makes this Eastern world unsuitable for receiving new approaches.

[ 26 ] The Western world has fewer traditions. At most, in the records of certain secret orders, it has traditions from the third post-Atlantean cultural epoch, from the time of cosmosophy, but these are traditions that are no longer understood and are presented to humanity in incomprehensible symbols. But at the same time, there is an elemental force in the West that can bring new impulses for development to fruition.

[ 27 ] So one could say: Once upon a time, the primordial impulses were there. They developed by becoming weaker and weaker until, towards the fourth post-Atlantean period, they lost themselves, so to speak, in the peculiar Greek cultural life. And then, with the indication of something new, the abstract, prosaic sobriety of Romanism developed (this is illustrated). But this must in turn take up spirituality and, becoming more and more powerful, must be permeated by inner spirituality. And in this way we then obtain, symbolically, what we can call the whirling movement of the impulses of humanity through the succession of ages.

[ 28 ] Such a figure has always been a kind of symbol for the most important thing in the universe; and that is what it is. When one speaks of an atomistic world, one must not imagine it as abstractly as is often the case today, but rather under the image of this whirl, as has often been done. But even in the largest scale, one must see this vortex movement. And today, I believe, we have gained it in a completely natural and elementary way from a concrete observation of the course of human spiritual development.

[ 29 ] That is what I wanted to present to you today.

[ 30 ] As I am about to go on a journey, there will be no lectures here for some time. I will let you know when the next lectures will take place, my dear friends.