Old and New Methods of Initiation

GA 210

17 February 1922, Dornach

Lecture VIII

Today we shall consider the passage of the human spirit and soul through the sense-perceptible physical organism. We shall look first at how this element of spirit and soul prepares for physical incarnation by descending from the spiritual worlds, and then at how it departs from physical incarnation through the portal of death and returns to the spiritual world. We shall take particular account of what happens in the soul during this process, for we must understand that on entering the physical organism, right at the moment of conception, a tremendous transformation takes place, and that another tremendous transformation takes place when the human being departs from physical incarnation through the portal of death.

We have described these things from numerous standpoints already. But today we shall be concerned with the inner experience of the soul itself. What are the last experiences of the soul before it descends to physical life on earth?

Between birth and death our soul is filled with an intricate fabric of thoughts, feelings and impulses of will. All these work together and intermingle to form the total structure of the soul. Our language has words for all the different forms of thought, of feeling, and of will impulses, so that we can describe all these things that are experienced during physical earthly life. And by considering our more subconscious feelings and our soul experiences as a whole, we can throw at least some light on what lives in the soul before it enters earthly life.

First of all we must be clear that the thought element leads a shadowy existence in the soul during physical earthly life. Thoughts are quite rightly described as pale and abstract. At best, the thoughts and mental pictures of the human being during earthly life are no more than mirror images of the external world. Human beings make thoughts about what they have perceived with their senses in the external world. As you know, if you subtract from your thought life everything you have perceived through your senses and everything you have experienced with the help of your senses during the course of earthly life, there is very little left. This is different, of course, if a study of spiritual science has led to the acquisition of other kinds of thought content than those drawn from the sense-perceptible world. Our thought world is shadowy because it has lost its inner vitality as a result of our descent into the physical sense-perceptible world. You could say that as a solid earthly object is to its shadow on the wall, so is the real content of thoughts to what lives in our thinking during earthly existence. If we seek to make the transition from the earthly thoughts of our life between birth and death to the true stature of our thought life, we find that this really only exists in our purely spiritual life before conception has taken place. It is like going from a shadow picture to whatever is casting the shadow. Before birth, or rather before conception, there is a vivid, fully alive existence which later becomes shadowy thoughts. The thought world existing as an inner weaving of soul before conception might well be described as our actual spiritual existence, our actual spiritual being. This inner weaving life before conception is, of course, something that fills the whole of the universe known to us. Before conception we live throughout the totality of the universe which otherwise surrounds us. The thoughts that then live in us during our life on earth are the shadows, confined within our human physical organism, of something that has life on a cosmic scale prior to conception.

This is a description of one element of our soul before birth, or before conception. Before the human being descends to the physical world we find, as one part of the content of his soul, something that is like thoughts when he is on earth but which is actually a spiritual element of his being when he is in the super-sensible world. The other part of the content of his soul cannot be described as anything other than fear, to use a concept taken from earthly life. In the period prior to physical life something lives in the soul which, as fear, fills it entirely. You must understand, however, that fear as an experience outside the physical body is something quite different from fear within the human physical body.

Before descending to earth man is a being of spirit and soul filled with an element of feeling which can only be compared with what is experienced in earthly life as fear. This fear is well justified for that period of human life about which I am now speaking. In the life between death and a new birth the human being has undergone manifold experiences of the kind which are possible while he is united with the cosmos. By the end of the life between death and a new birth he has, in a way, grown tired of this cosmic life, just as he grows tired of earthly life when, towards the end, his bodily organization shrivels up and becomes infirm. This tiring of life beyond the earth is expressed not so much in actual tiredness as in fear of the cosmos. The human being takes flight from the cosmos. He senses that the fundamental aspect of the cosmos is something that has now become foreign to him; it no longer has anything to offer him. He feels a kind of timidity, comparable with fear, towards the element in which he finds himself. He longs to withdraw from this cosmic feeling and contract into a human physical body.

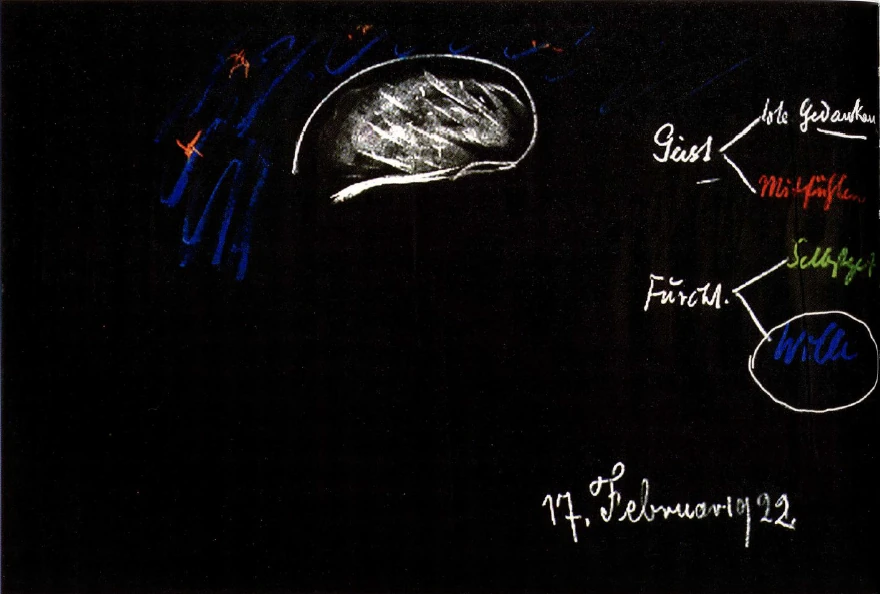

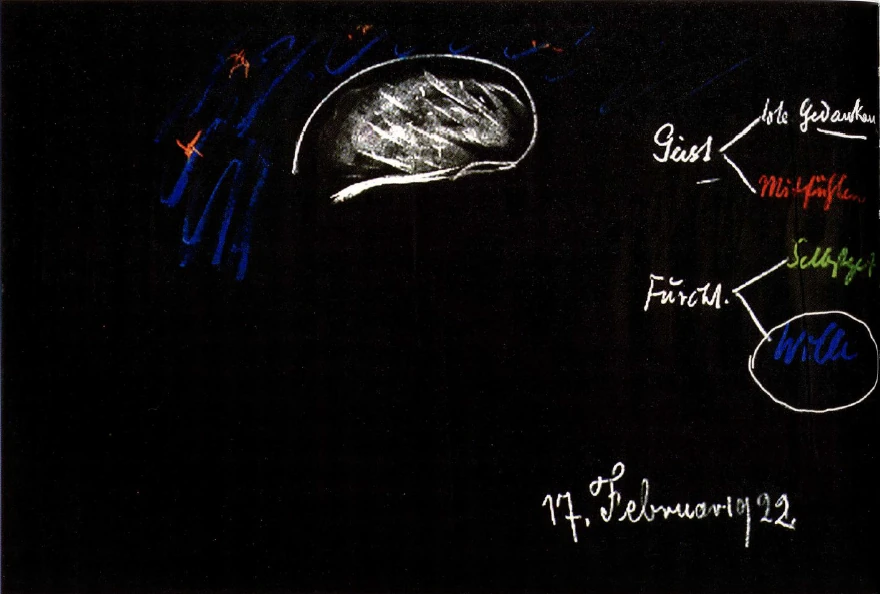

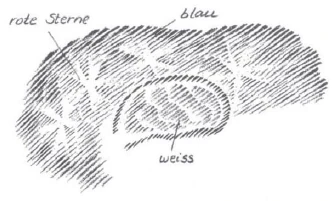

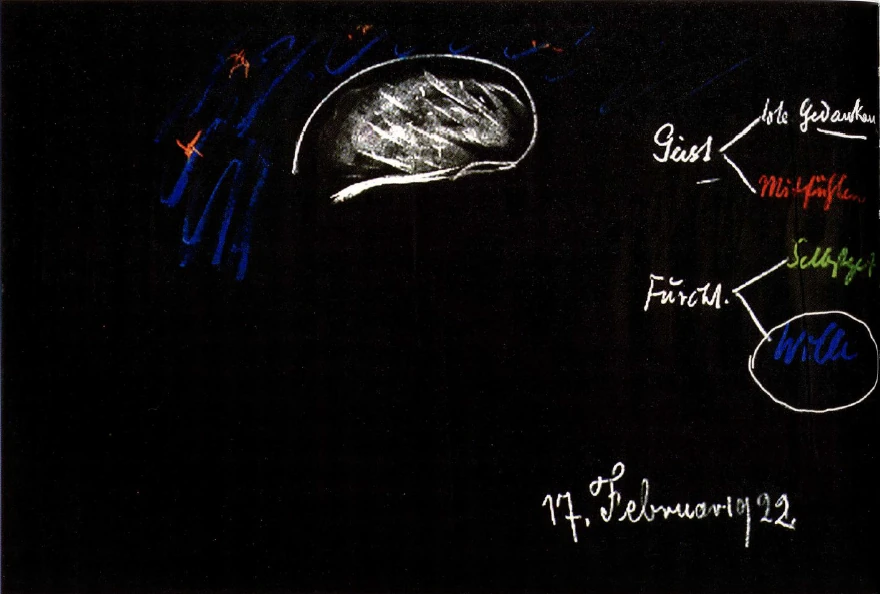

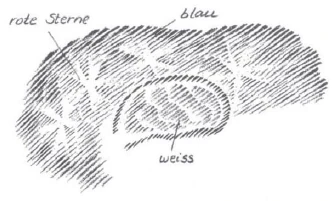

From the earth a certain force of attraction comes to meet this state of fear in the human being. In a diagram it would look like this. Think of the cranium, and the brain within. Here is the base of the cranium. As I have frequently suggested, the human brain with its remarkable convolutions is a kind of copy of the starry heavens, of the universe. This brain structure made up of cells is indeed a copy of the starry heavens (see diagram). While living before birth in the cosmos the

human being encompasses with his spirituality the whole of the starry world. But now he fears it. He withdraws into an earthly image of the starry heavens, an image in the human brain.

Now we come to the choice made by man's spirit and soul. For now the soul chooses whichever brain—in the process of being formed—most closely resembles the starry constellation in which it stood before descending into the earthly realm. Naturally, the brain of one embryo depicts the starry heavens differently from that of another embryo. And the soul feels attracted towards the brain which has the most similarity with the starry constellation in which it existed before descending to earth.

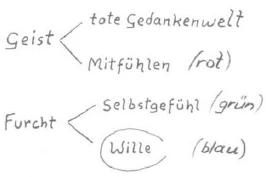

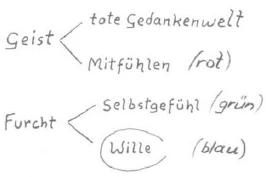

So it is, in the main, a feeling of timidity which leads the soul down to the confines of a human being—a feeling of fearfulness with regard to infinity, you might say. This feeling of fear pertains more to the soul. And the thought world which unfolds more and more from childhood into adulthood pertains more to the spirit. Both—the feeling of fear and also the spiritual element which is transformed into shadowy thoughts—undergo a substantial metamorphosis which I should now like to describe to you. I can only use expressions which will seem unusual as far as ordinary thinking goes, but ordinary thinking lacks points of reference which might serve to describe these things. Ordinary thinking lies far from all aspects of this theme, so we cannot avoid using unusual expressions if we want to give an adequate description of them.

Let us start with the spiritual element which lives in the cosmos and then makes its way to the confined dwelling place of the human body, unfolding chiefly through the nervous system and the brain and undergoing metamorphosis as it does so. There are two aspects of this. First of all it is definitely true to say that the being who is man in the world of spirit and soul prior to conception dies during the transition into the physical body. Birth in the physical body is a dying for the spirit and soul life of man. And when a death takes place there is always a corpse. Just as a corpse remains when man dies on earth, so a corpse also remains when the element of spirit and soul goes down to the earth through conception and dies in the heavenly region. For the whole of our earthly life we then live, as far as our thoughts are concerned, on what remains as a corpse. The corpse is our world of thoughts. Something that is dead is the world of shadowy thoughts. So we can say that as the spiritual aspect of man descends to life on earth through conception, it dies for the world of spirit and soul and leaves this corpse behind.

Just as the corpse of the physical human being dissolves into the elements of earth, so the element of spirit and soul dissolves in the spiritual world and becomes the force which is unfolded in physical thoughts. Just as the earth goes to work on the corpse when we bury it, or as fire does when we cremate it, so throughout life we go to work on the corpse of our spirit and soul element in our world of physical thoughts. The world of physical thoughts is the continuing in death of what exists as real spiritual life before man descends into physical earthly life.

The other living element which enters into man from his pre-earthly life comes into play in the physical human being, not through the world of thoughts, but in the widest possible sense in everything which we can call feelings—feelings to do with man as well as feelings to do with nature. Everything by which you spread into your environment in a feeling way (see chart) is an element which represents a living echo of pre-earthly life.

You do not experience your pre-earthly life in a living way in your thoughts but only in your feelings for other creatures. If we love a flower or a person, this is a force which has been given to us out of our pre-earthly life, but in a living way. So if we love a person we can say that we love him or her not only out of our experiences in this earthly life, but also out of karma, out of being connected in earlier earthly lives. Something living is carried over from pre-earthly life in so far as the sympathetic sphere of the human being is concerned. On the other hand, what is a living spiritual element between death and a new birth dies into our thought world during earthly life.

That is why our thought world is so pale and shadowy and dead during earthly life, because it actually represents a part of our pre-earthly experience which has died.

Now let us turn to the second element—timidity, fear—which is also metamorphosed in such a way that it falls into two parts. What we experience prior to our descent into the earthly world as a fear which fills our whole soul and makes us want to flee from the spiritual world, becomes, on entering the body, on the one hand something that I should like to describe as a feeling of self. This feeling of self is metamorphosed fear. Transformed fear from pre-earthly life is what makes you feel that you are a self, that you are self-contained.

The other part into which fear is transmuted is our will. All our will impulses, everything on which our activity in the world is based—all this exists as fear before we descend into earthly life.

You see once again what a good thing it is for earthly life that human beings do not step consciously past the Guardian of the Threshold. I have frequently said that human beings sleep through what the will represents, down there in the human organism. They have an intention, then they carry it out, and then they perceive the consequence. But what lies between the intention to do a deed and the accomplished deed, that in which the will actually consists—this is something in which human beings are as much asleep as they are between falling asleep and waking up again. If they were to look down and see what lay at the foundation of their will they would feel, strongly welling up out of their organism, the fear coming in from their pre-earthly life.

This is also something that has to be overcome in initiation. But if we look into ourselves, the first thing we see is the feeling of self. This is something which must not be caused to increase too much as a result of the training. Otherwise, when the human being finally steps into the spiritual world he might fall into megalomania. But at the foundation of all his will impulses he will find fear and he must therefore be strengthened to withstand this fear.

As you see, in all the exercises contained in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds the aim is to learn to bear the fear which we come to perceive in the way I have described. This fear is something that has to be there amongst the forces of development, otherwise human beings would never descend from the spiritual world into earthly existence. They would not flee from the spiritual world. They would not develop the urge to enter into the limitations of the physical body. The fact that they do develop this urge stems from this fear of the spiritual world, which quite naturally becomes a part of their soul configuration once they have lived for a time between death and a new birth.

So thoughts are attached to us like a corpse—or rather the power of the thoughts, not the thoughts themselves. We can describe this even more exactly. However, to consider this more exact description it will benecessary to develop certain very precise ideas. The spiritual force which dies in our thoughts and becomes a corpse when we descend into physical earthly existence is the same force which builds our organs out of the cosmos. Our lung, heart, stomach—all our specific organs—are formed out of the power of thought of the universe.

When we enter into earthly life this power of thought enters the narrow confines of our organism. What does the earth and its environment want of us? It wants us to create an image of it within ourselves. But if we were to create an image in ourselves, then during the course of our lifetime all our inner organs, such as our lungs—but, above all, the manifold convolutions of our brain—would be transformed into crystal-like formations. We should all become statues resembling not human beings but crystals in various contrasting groups. We should gradually come to be inorganic, lifeless shapes—statues after a fashion.

The human organism resists this. It stands by the shape of its inner organs. It will not have it that, for instance, its lungs might be formed to represent, let us say, a range of mountains. It will not allow its heart to be transformed into a cluster of crystals. It resists this. And this resistance brings it about that instead of forming images of our earthly environment in our organs we do so only in the shadow images of our thoughts. So our power of thought is actually always on the way to making us into an image of our physical earth, of the physical form of our earth. We constantly want to become a system of crystals. But our organism will not permit this. It has so much which has to be developed in the living realm, in the realm of sympathy, in the realm of feeling of self and in the realm of will impulses, that it does not permit it. It will not allow our lungs to be transformed into something that looks like crystals growing out of the earth. It resists this formation into earthly shapes, and so the images of earthly shapes only come about in geometry and in whatever other thoughts we form about our earthly environment. As I said, you must think with absolute exactitude if you want to reach the point where you can imagine all this.

But the tendency is always there of coming to resemble the system of our thoughts. We have to fight constantly in order not to take onthis resemblance. We are constantly striving to become a kind of work of art—though given the kind of thoughts human beings have on the whole, it would not be a very beautiful work of art to look at. But we strive to attain an external appearance that resembles what exists in our thoughts as no more than images and shadows. We do not achieve this resemblance, but we mirror back what we are aiming for, so that it turns into our thoughts instead. It is a process that can truly be likened to the creation of mirror images.

If you have a mirror with an object in front of it, then you get a mirror image of the object. The object is not inside the mirror. Everything we see before our eyes constantly wants to bring about an actual structure within us. But we resist this. We keep our brain as it is. Because of this, the object is mirrored back and becomes the mental image. A table wants to make your very brain into a table but you do not allow this to happen. In consequence an image of the table arises in you. This act of rejection is the mirroring process. That is why, in our thought life, our thoughts are only shadow images of the external world. When it comes to our feelings, however, the situation is different. Try once to imagine absolutely accurately what is involved in feeling something. A round table feels different from one with corners. You feel the corners. The thought of this angular table does not affect you very much, whereas getting the feel of the corners is more painful than gently following the curve of a round table. When we feel, therefore, external forms come more to life within us than when we think.

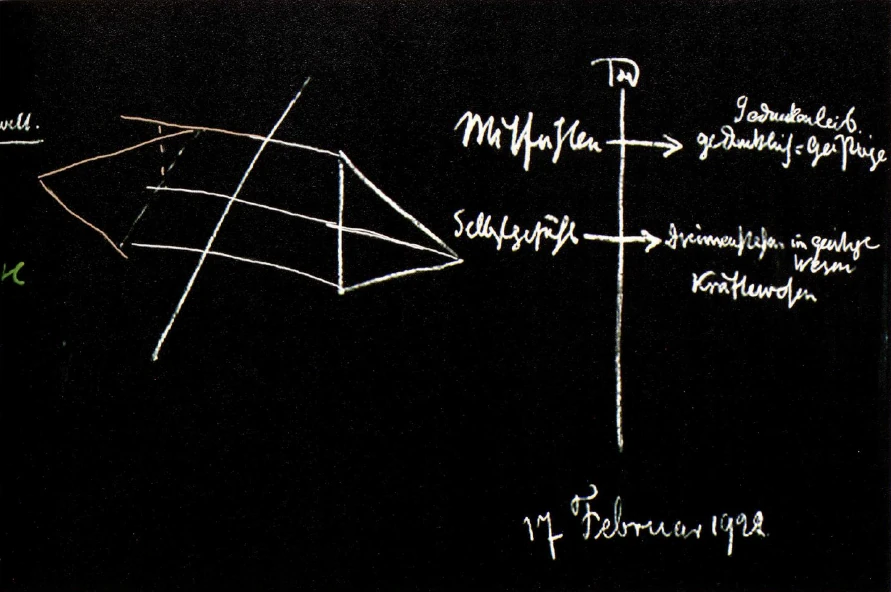

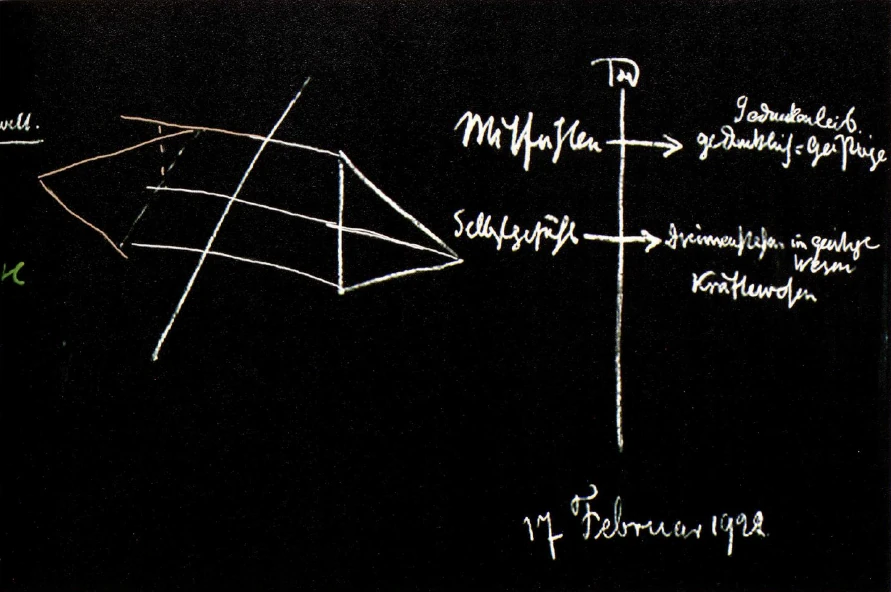

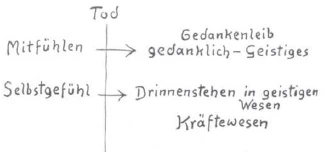

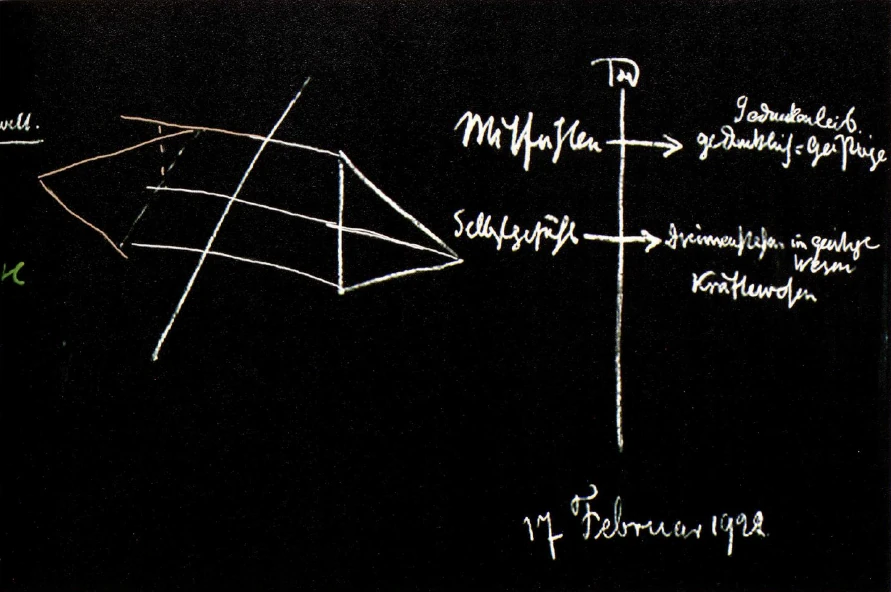

This is an indication of the metamorphosis undergone by our element of soul and spirit when it comes into earthly existence from pre-earthly existence. But now what occurs when we go through the portal of death? Our world of thought is, so far as its strength is concerned, only the corpse of pre-earthly existence. It is of little significance. It disappears when we go through the portal of death, just as our mirror image disappears if we suddenly take away the mirror. So, in speaking of immortality, there is absolutely no point in reflecting on the earthly power of thought for it certainly does not accompany us through the portal of death. What does go through the portal of death with us is everything we have developed in the way of sympathy, of feeling and sensing towards earthly things. Our feeling of sympathy goes through the portal of death. Inasmuch as we have sympathy towards our environment, we develop the strength (see table) in the spiritual world to stand among the spiritual beings in the spiritual element of thought. Our sympathy, which our body keeps separate from our earthly environment, streams out now, after death, into our spiritual environment and unites with the spiritual thought element of the world into which we step on going through the portal of death.

Because we flow with our sympathy into the spiritual element of thought, we develop once again a kind of thought body, a living thought body which is ours for the time between death and our next birth. And the feeling of self we have on earth becomes a kind of ‘standing within’ other beings. Whilst we are on earth, our feeling of self only lets us know that we are within our body, but once we have passed through the portal of death we learn to know that we are in other beings, the beings of the higher hierarchies. And because we stand within spiritual beings we receive from them forces which lead us onwards on our course through life between death and a new birth. In this way our own being of forces develops. This is the metamorphosis of the element of spirit and soul which takes place when we pass through the portal of death.

Unlike our world of thought, our will does not disappear at death. It is the source of the content of our feelings of self. Imagine that you want something which satisfies you. This wanting in itself gives you something that satisfies you, it gives your feeling of self a particular nuance. If you have done something that does not satisfy you, this too gives your feeling of self a particular nuance. Our will is not only something that acts outwards. It also rays forcefully back into our inner being. We know what we are from what we can do. And this nuance of our feeling of self, this raying back into us of our will element, is something which we take into the spiritual world with us, together with our feeling of self. So we take our will—or rather the raying back of our will into our feeling of self—with us when we submerge ourselves in the beings of the higher hierarchies. And because we take with us this element, which has either strengthened or weakened our feeling of self, we find the force of our karma, our destiny.

Gaining an understanding of these things helps us to see what the human being really is. And we also learn to recognize certain symptoms which accompany earthly life. In earthly life fear certainly puts in an appearance here and there. But it must never be allowed to fill our soul entirely. It would be sad if this were to happen. But before we come down to earthly life our soul is indeed entirely filled with fear, and in that situation fear is what we need so that we really do descend into physical earthly life.

Our feeling of self, though, is something that must not be allowed to exceed more than a certain degree; indeed it really ought not to be felt independently at all in earthly life. Someone who develops his feeling of self with too much independence turns into a person who knows only himself. Our feeling of self is actually only with us during earthly life, so that we keep a hold on our body until we die, returning to it every morning after sleep. If we lacked this feeling of self during earthly life we would fail to return. But after death we need it when we become submerged in the world of spiritual beings, because without it we would all the time lose ourselves.

We do indeed submerge ourselves there in real spiritual beings. The earth, on the other hand, makes no such demands on us. If you go for a walk in the woods, you stay on the path, and the trees are to the left and right of you, and in front and behind. You see the trees but the trees do not expect you to enter into them—they do not expect you to become tree nymphs and submerge yourselves in them. But the spiritual beings of the higher hierarchies, whose world we enter after death—they do expect us to submerge ourselves in them. We have to become all of them. So if, on passing through the portal of death, we were to enter this spiritual world without our feeling of self, we would lose ourselves. We need our feeling of self there simply in order to maintain ourselves. And moral deeds we have done during earthly life, deeds which have justifiably enhanced our feeling of self—these protect us from losing ourselves after death.

These are thoughts and ideas which, from now on, ought to enter once again into human consciousness for the near future of earthly evolution. These thoughts and ideas simply flowed into mankind in earliest times, when understanding was still instinctively clairvoyant. Human beings used to have a strong feeling of what they had been before they descended into earthly life. This was strongly developed in primeval times. But hope of a life after death was less strongly developed in primeval times. This was something that was taken for granted. Today we are chiefly interested in what we might experience after we die. In primeval times, thousands of years ago, people were more concerned about their life prior to descending to the earth.

A time then came when clairvoyance, which had originally been instinctive, waned, and the intense connection of the soul with life before birth also waned. Then two spiritual streams sprang up which prepared what had now to develop in human civilization. We now have two clearly distinct streams which we have described from varying standpoints. Today we shall approach them from a particular standpoint which will also be a help to us in our considerations tomorrow and the next day.

Take earthly evolution prior to the Mystery of Golgotha. You find, spread over the earth, the heathen culture, and in a certain way separated from this, a culture which one could say was that of the Old Testament. What was particularly characteristic of this heathen culture? It contained a definite awareness of the fact that everything physical surrounding man contained a spiritual element. The heathen culture had a strong awareness of the nature of living thoughts which become transformed into dead thoughts. In the beings of the different kingdoms of nature, this culture saw everywhere the living element of which human thoughts were the dead counterpart. Heathen culture perceived the living thoughts of the cosmos and regarded man as belonging to these living thoughts of the cosmos.

One part of this heathen world that was particularly filled with life was that of the peoples of ancient Greece. You know that the idea of destiny was particularly strong in the world of these ancient Greek peoples. And—think of certain Greek dramas—this idea of destiny permeated human life with laws in the way the natural laws permeate nature. The ancient Greeks felt that they stood in life permeated with destiny, just as natural things stand permeated with the laws of nature. Destiny descended on human beings within this Greek outlook like a force of nature. This feeling was characteristic of all heathen cultures, but it was particularly marked among the Greeks. The heathen world saw spirit in all of nature. There was no specific knowledge of nature in the sense of the natural science we have today, but there was an all-embracing knowledge of nature. Where people saw nature, they spoke of the spirit. This was a science of nature which was, at the same time, a science of the spirit. The heathen peoples were less interested in the inner being of man. They looked on man from the outside as a being of nature. They could do this because they saw all the other natural things as being filled with a soul element too. They did not think of trees, plants, or clouds as soulless objects. So they could look at human beings from outside in a similar way and yet not think of them as being soulless. Filling all nature with soul in this way, the ancient heathen was able to regard human beings as natural creatures. Thus the ancient heathen world was something which contained from the start a spiritual element which inclined towards the world of spirit.

The creed which then ran its course in the Old Testament was the polar opposite of this. The Old Testament knew nature neither in the way we know it—I mean in the way we come to know it as we turn towards spiritual science—nor in the way the ancient heathen knew it. The Old Testament knew only a moral world order, and Jahve is the ruler of this moral world order; only what Jahve wills takes place. So in the world of the Old Testament the view arose as a matter of course that one must not make images of the soul and spirit element. The heathen world could never have come to such a view, for it saw images of the spirit in every tree and every plant. In the world of the Old Testament no images were seen, for everywhere the invisible, imageless spirit ruled.

We ought to see in the New Testament a coming together of these two spiritual streams. People have always given prominence to either one view or the other. Thus, for instance, the heathen element was always predominant where religion was more a matter of seeing the objects of religion. Pictures were made of spiritual beings, pictures copied from nature. In contrast, the Old Testament element developed wherever the newer scientific attitude arose with its tendency towards a lack of images. In many ways modern materialistic science contains an echo of the Old Testament, of the imageless Old Testament. Materialistic science strives for a clear distinction between the material element in which no trace of spirit is left, and the spiritual element which is supposed to live in the moral sphere only, and of which no image may be made, or which we may not be allowed to see in the earthly realm.

This particular characteristic which is prevalent in today's materialistic form of science is, actually, an Old Testament impulse which has come over to our time. Science has not yet become Christian. The science of materialism is fundamentally an Old Testament science. One of the main tasks as civilization progresses will be to overcome both streams and resolve them in a higher synthesis. We must understand that both the heathen stream and the Jewish stream are one-sided and that, in the way they still exercise an influence today, they need to be overcome.

Science will have to raise itself up to the spirit. Art, which contains much that is heathen, has made various attempts to become Christian but most of these attempts have fallen into luciferic and heathen ways. Art will have to lead to a Christian element. What we have today is but an echo of the heathen and the Old Testament elements. Our consciousness is not yet fully Christian. This is what we must particularly feel when we consider factually, as described by spiritual science, the way in which human beings pass through birth and death.

Über den Durchgang der menschlichen Geist-Seelenwesenheit durch die physisch-sinnliche Organisation

[ 1 ] Wir wollen heute einmal den Durchgang der menschlichen Geist-Seelenwesenheit durch die physisch-sinnliche Organisation betrachten, und zwar so, wie sich dieses Geistig-Seelische zunächst anschickt für die physische Inkarnation, indem es herunterkommt von den geistigen Welten, und dann, wie es wiederum hinausgeht durch die Pforte des Todes aus der physisch-sinnlichen Inkarnation in die geistige Welt. Und insbesondere wollen wir heute Rücksicht nehmen auf die seelischen Eigentümlichkeiten dieses Vorganges. Wir müssen uns klar darüber sein, daß beim Eintreten in die physische Organisation, und zwar schon bei der Konzeption, eine gewaltige Veränderung vor sich geht und daß wiederum eine gewaltige Veränderung eintritt, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes die physische Inkarnation verläßt.

[ 2 ] Nun haben wir das ja schon von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus charakterisiert; heute aber wollen wir gewissermaßen auf das innere Erlebnis der Seele als solche unseren Blick lenken. Wir wollen uns fragen: Welches sind die letzten Erlebnisse des Seelischen, bevor es heruntersteigt in das physische Erdenleben?

[ 3 ] Wenn wir das Seelische beobachten zwischen der Geburt und dem Tode, so finden wir es in der mannigfaltigsten Weise durchwebt von Gedanken, von Gefühlen, von Willensimpulsen. All das wirkt ineinander zu einem seelischen Gesamtbilde. Und wir haben ja auch für die einzelnen Gedankenformen, für die Formen des Gefühls, für die Formen der Willensimpulse besondere Sprachbezeichnungen und wissen aus dem, was im physischen Erdenleben seelisch erlebt wird, gewisse Arten von Gefühlen zu charakterisieren. Wir können, indem wir von mehr unterbewußten Gefühlserlebnissen und von Seelenerlebnissen überhaupt ausgehen, wenigstens einigermaßen ein Licht werfen auf das, was in der Seele lebt, bevor sie ins irdische Leben eintritt.

[ 4 ] Zunächst muß uns ja klar sein, daß das gedankliche Element als solches während des physischen Erdendaseins in der Seele wie ein Schattenhaftes lebt. Die Gedanken werden mit Recht blaß, abstrakt genannt. Das meiste, was der Mensch während des Erdenlebens an Gedanken, an Vorstellungen aufbringt, ist schließlich nichts weiter als Spiegelbild der Außenwelt. Der Mensch stellt sich vor, was er in der Außenwelt durch seine Sinne wahrgenommen hat, und Sie werden ja wissen, daß im Grunde genommen sehr wenig übrigbleibt, sobald Sie alles, was durch die Sinne wahrgenommen worden ist oder was im Laufe des physischen Erdenlebens sonst im Beisein der Sinne erlebt worden ist, von dem Gedankenleben abziehen, wenn nicht gerade ein Studium der Geisteswissenschaft dazu geführt hat, andern Gedankeninhalt zu bekommen als den, der aus der Sinneswelt herausgezogen ist. Aber diese schattenhafte Gedankenwelt ist eben aus dem Grunde schattenhaft, weil sie ihre innere Lebendigkeit verloren hat beim Herabsteigen in die physisch-sinnliche Welt. Gerade dasjenige, was in uns das gedankenhafte Erleben ist, das ist ein reges, in sich bewegtes, in sich volles Leben vor dem Hinuntersteigen in die physische Welt. Man kann sagen, wie sich irgendeine volle irdische Gestalt zu dem Schatten verhält, den sie an die Wand wirft, so verhält sich das, was in den Gedanken eigentlich lebt, zu dem, was als Gedanken während unseres Erdendaseins auftritt. Und wenn wir von den irdischen Gedanken, wie wir sie zwischen Geburt und Tod haben, zu der wahren Gestalt des Gedankenlebens gehen, so sind sie [diese Gedanken] doch eigentlich nur im rein geistigen Leben vor der Konzeption vorhanden. Es ist gerade so, wenn wir von einem Wandschattenbild zu demjenigen gehen, was es darstellt. Es ist ein reges inneres, voll lebendiges Dasein gerade in dem, was später abgeschattete Gedanken sind, vor der Geburt oder vor der Konzeption vorhanden. Wir können durchaus als das eigentliche geistige Dasein, als die eigentliche geistige Wesenhaftigkeit bezeichnen, was von der Gedankenwelt vor der Konzeption als inneres seelisches Weben und Leben vorhanden ist. Dieses innerlich-seelische Weben und Leben ist natürlich vor der Konzeption etwas, was das ganze uns bekannte Weltenall durchdringt. Wir leben eigentlich vor der Konzeption im Ganzen der Welt, die uns sonst umgibt, und was als Gedanke im Menschen dann während des Erdenlebens vorhanden ist, das ist das Schattenbild im kleinen Raum, im menschlichen physischen Organismus, von dem, was eigentlich kosmisches Leben hat vor der Konzeption.

[ 5 ] Damit bezeichnen wir das eine Element des Seelischen vor der Geburt oder vor der Konzeption. Was im Irdischen also Gedankenhaftes, im Außerirdischen bei der menschlichen Wesenheit eigentlich Geistiges ist, das finden wir, bevor der Mensch heruntersteigt in die physische Welt, als Inhalt der Seele. Das andere, was Inhalt der Seele ist, das ist nicht anders zu bezeichnen, wenn wir die Begriffe von dem irdischen Leben hernehmen wollen, als indem wir sagen: Es ist Furcht. In der Seele lebt in der Zeit, die dem physischen Erdenleben vorangeht, etwas, was sie ganz durchdringt als Furcht. Nur natürlich, wenn so etwas gesagt wird, müssen Sie sich klar darüber sein, daß Furcht als Erlebnis außerhalb des physischen Leibes etwas ganz anderes ist als im physischen Menschenleibe.

[ 6 ] Der Mensch ist also, bevor er zur Erde heruntersteigt, ein GeistigSeelisches, durchzogen von einem Gefühlselemente, das man nur mit etwas, was der Mensch im Erdenleben als Furcht erfährt, vergleichen kann. Diese Furcht hat ihre gute Berechtigung für die Zeit des Menschenlebens, von der ich eben spreche. Der Mensch hat in dem Leben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt alle möglichen Erfahrungen gemacht, die sich eben in diesem kosmischen Verbundensein mit dem All machen lassen. Der Mensch ist gewissermaßen müde geworden dieses kosmischen Lebens am Ende seines Daseins zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, wie der Mensch durch das Vertrocknen, durch das Abgelähmtwerden seiner Leibesorganisation am Ende seines Erdenlebens für das irdische Leben müde ist. Der Mensch ist gewissermaßen müde geworden des außerirdischen Lebens. Und dieses Müdewerden drückt sich eben nicht als Müdewerden aus, sondern es drückt sich aus als Furcht vor dem All. Der Mensch flieht gewissermaßen das All. Er empfindet das, was die Grundeigenschaft des Alls ist, als etwas ihm nunmehr Fremdgewordenes, das ihm nichts mehr gibt; er empfindet eine Art von Scheu, die mit Furcht zu vergleichen ist, vor dem Elemente, in dem der Mensch darinnen ist. Er will sich herausziehen aus diesem Allgefühl, und er will sich zusammenziehen in das, was menschliche Leiblichkeit ist.

[ 7 ] Nun ist ja das, was sich von der Erde aus dem Menschen entgegenbietet, etwas, was in gewissem Sinne eine Art Anziehungskraft ausübt diesem Furchtzustande gegenüber, in dem der Mensch sich befindet, wenn er sich wiederum dem Erdendasein nähert. Wenn ich schematisch die Sache zeichnen soll, so müßte ich das in der folgenden Weise tun: Denken Sie sich die Schädeldecke mit dem Gehirn darinnen. Das ist der Boden der Schädeldecke. Nun, dasjenige, was da in den Formen des Gehirnes sich ausbildet, was so merkwürdige Windungen darstellt, das ist beim menschlichen Organismus, wie ich verschiedentlich schon angedeutet habe, eine Art Nachbildung des Sternenhimmels, des Weltenalls. Da drinnen in diesem zelligen Gebilde des Gehirns ist wirklich der Sternenhimmel nachgebildet (siehe Zeichnung). Und indem der Mensch vor dem Herunterkommen ins Irdische in dem All draußen, in der Sternenwelt gelebt hat, hat er ja in seiner Geistigkeit dieses Sternenall umfaßt. Aber jetzt fürchtet er sich vor demselben. Er zieht sich zusammen nach dem, was wie ein irdisches Abbild dieses Sternenraumes im menschlichen Gehirn ist.

[ 8 ] Und da kommen wir zu dem, was man bezeichnen könnte als die Wahl, die das Geistig-Seelische trifft. Es geht die Seele eben zu demjenigen in Bildung begriffenen Gehirn hin, welches die meiste Ähnlichkeit hat mit der Sternkonstellation, in der die Seele vor dem Herabsteigen in das Irdische drinnengestanden hat. Es ist ja natürlich, daß das Gehirn des einen Embryos in anderer Weise als das eines andern Embryos ein Abbild des Sternenhimmels ist. Nach demjenigen Gehirn hin aber fühlt sich das Seelische angezogen, das am meisten Ähnlichkeit mit der Sternkonstellation hat, in der die Seele war, bevor sie auf die Erde heruntergestiegen ist.

[ 9 ] Es ist also im wesentlichen eine Art Furchtgefühl, was die Seele in den engen menschlichen Raum herunterführt, ein Furchtgefühl vor dem Unendlichen, könnte man sagen. Dieses Furchtgefühl ist das mehr Seelische. Die Gedankenwelt, die dann nach und nach von der Kindheit bis zur Erwachsenheit entfaltet wird, ist das Geistige. Dabei gehen dann sowohl dieses Furchtgefühl wie auch das Geistige, das dann zu den Gedankenschatten wird, eine wesentliche Metamorphose durch. Diese Metamorphose möchte ich Ihnen charakterisieren. Man kann sich da nur der Ausdrücke bedienen, welche für das gewöhnliche Vorstellen ungewohnt sind; allein das heutige gewöhnliche Vorstellen hat ja auch durchaus keine Anhaltspunkte, um diese Dinge zu bezeichnen. Es liegt ab von alledem, was in diese Region hineingehört, und daher müssen wir uns schon ungewohnter Ausdrücke bedienen, wenn wir diese den heutigen Vorstellungen abliegenden Dinge adäquat bezeichnen wollen.

[ 10 ] Wir haben also zunächst das geistige Element, das da lebt im All, das sich gewissermaßen hineinbegibt in die enge Wohnung des menschlichen Leibes, sich namentlich durch das Nervensystem, durch das Gehirn entfaltet und sich dabei metamorphosieren muß. Dabei gliedert es sich in zwei Regionen. Man kann wirklich davon sprechen, daß das, was der Mensch vor der Konzeption in der geistig-seelischen Welt ist, beim Übergehen in die physische Leiblichkeit stirbt. Die Geburt in der physischen Leiblichkeit ist ein Absterben für das geistig-seelische Leben des Menschen. Beim Absterben bleibt immer ein Leichnam übrig. Wie, wenn der Mensch für die Erde stirbt, der Leichnam übrigbleibt, so bleibt auch ein Leichnam übrig, wenn das Geistig-Seelische, indem es durch die Konzeption zur Erde hingeht - wenn ich mich des Ausdrucks bedienen darf -, für das Himmlische abstirbt. Von dem, was nun da als ein Leichnam übrigbleibt, von dem leben wir eigentlich gedanklich unser ganzes Erdenleben hindurch. Der Leichnam ist nämlich die Gedankenwelt; das Tote, das ist diese Schattenwelt. So daß wir sagen können: Indem das Geistige des Menschen durch die Konzeption ins Erdenleben heruntersteigt, stirbt es für die geistig-seelische Welt ab und läßt diesen Leichnam zurück.

[ 11 ] Geradeso wie der Leichnam des physischen Menschen in die irdischen Elemente sich auflöst, so löst sich für die geistige Welt das Geistig-Seelische auf und wird zu der Kraft, die in den physischen Gedanken entfaltet wird. Die Gedankenwelt ist der Leichnam unseres Geistig-Seelischen. So, wie die Erde den Leichnam verarbeitet, wenn wir ihn in die Erde legen, oder wie ihn das Feuer verarbeitet, wenn wir ihn verbrennen, so verarbeiten wir unser ganzes Leben hindurch den Leichnam unseres Geistig-Seelischen in unserer physischen Gedankenwelt. Also die physische Gedankenwelt ist im Grunde genommen das fortgehende Tote dessen, was als Wirkliches, als geistiges Leben vorhanden ist, bevor der Mensch in die physische Irdischheiit heruntersteigt.

[ 12 ] Das andere, was in den Menschen als Lebendes einkehrt von seinem vorirdischen Dasein, das kommt im physischen Menschen nicht durch die Gedankenwelt zur Geltung, sondern im weitesten Umfange durch alles dasjenige, was wir Gefühl nennen können, sowohl Mitfühlen mit den Menschen wie auch Mitfühlen mit der Natur. Also alles das, wodurch Sie sich fühlend, empfindend in die Außenwelt verbreiten, das ist ein Element, das die lebendige Nachwirkung des vorirdischen Daseins darstellt (siehe Schema S. 97).

[ 13 ] Nicht in Ihren Gedanken erleben Sie auf lebendige Art Ihr vorirdisches Dasein, sondern in dem Gefühle mit den andern Wesen. Wenn wir eine Blume liebhaben, wenn wir einen Menschen liebhaben, so ist das im wesentlichen eine Kraft, die uns aus dem vorirdischen Dasein gegeben ist, aber in einer lebendigen Weise. So daß wir auch sagen können: Wenn wir zum Beispiel einen Menschen liebhaben, so haben wir ihn nicht bloß aus Erfahrungen im Erdenleben lieb, sondern auch aus dem Karma heraus, aus der Verbundenheit in früheren Erdenleben. Es wird etwas Lebendiges hinübergetragen aus dem vorirdischen Dasein, wenn die mitfühlende Sphäre des Menschen in Betracht kommt. Dagegen stirbt das, was lebendiges Geistelement zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt ist, in die Gedankenwelt hinein. Deshalb hat die Gedankenwelt während des irdischen Daseins dieses Blasse, Schattenhafte, dieses Tote an sich, weil es eigentlich den abgestorbenen Teil der vorirdischen Erlebnisse des Menschen darstellt.

[ 14 ] Das zweite ist dann das, was man als Furcht bezeichnen muß, und auch das metamorphosiert sich so, daß es in zwei Elemente zerfällt. Das eine, also dasjenige, was wir vor dem Heruntersteigen in die irdische Welt als Furcht erleben, was die Seele ganz durchzieht und wobei sie die geistige Welt fliehen will, das wird etwas anderes, wenn es in den Leib einzieht, und das äußert sich zunächst im Inneren des Menschen als etwas, was ich bezeichnen möchte als das Selbstgefühl. Das Selbstgefühl ist wirklich die umgewandelte Furcht. Daß Sie sich als ein Selbst fühlen, daß Sie sich in sich selbst halten, das ist umgewandelte Furcht aus dem vorirdischen Leben.

[ 15 ] Und der andere Teil, in den sich die Furcht verwandelt, das ist der Wille. Alles, was als Willensimpulse auftritt, was unserer Betätigung in der Welt zugrunde liegt, all das ist vor dem Heruntersteigen ins irdische Leben als Furcht vorhanden.

[ 16 ] Sie sehen, hier ist wiederum dem Menschen ein Gutes für das irdische Leben erwiesen dadurch, daß er im gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein nicht an dem Hüter der Schwelle vorüberschreitet. Ich sagte ja oftmals: Das, was der Wille eigentlich da unten darstellt im menschlichen Organismus, das verschläft der Mensch. Der Mensch hat die Intention seines Wollens, dann führt er das Wollen aus; dann hat er wiederum die Vorstellung von den Ergebnissen. Was aber zwischen diesen beiden Vorstellungswelten liegt, zwischen der Absicht, eine Handlung auszuführen und der vollendeten Handlung, also das, was eigentlich im Willen lebt, das wird von dem Menschen zunächst so verschlafen, wie er die Zustände zwischen dem Einschlafen und dem Aufwachen verschläft. Wenn der Mensch hinunterschauen würde in das, was seinem Willen zugrunde liegt, er würde heraufkraften fühlen aus seinem Organismus die aus dem vorirdischen Leben hereinkommende Furcht.

[ 17 ] Das ist es auch, was bei der Einweihung überwunden werden muß. Wenn man in sich selbst hineinschaut, sieht man zuerst allerdings das Selbstgefühl. Das ist ja schon etwas, was durch die Erziehung nicht zu sehr gesteigert werden darf, damit der Mensch, wenn er in die geistige Welt eintritt, nicht eben in Größenwahn verfällt. Aber auf dem Grunde seiner Willensimpulse findet er überall die Furcht, und er muß gestärkt sein gegen diese Furcht.

[ 18 ] Im wesentlichen werden Sie daher sehen, daß überall in den Übungen, die angegeben sind in meinem Buche «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse höherer Welten?», darauf hingezielt ist, die Furcht, die man in der eben bezeichneten Weise gewahr wird, zu ertragen. Diese Furcht ist etwas, was unter den Entwickelungskräften da sein muß, sonst würde der Mensch gar nicht in das irdische Dasein herunterkommen aus der geistigen Welt. Er würde die geistige Welt nicht fliehen. Er würde nicht den Impuls entwickeln, in einen begrenzten physischen Menschenleib einzuziehen. Daß er es tut, hängt eben damit zusammen, daß er die Furcht vor der geistigen Welt als eine ganz natürliche Eigenschaft der Seele hat, wenn er eine Zeitlang zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt gelebt hat.

[ 19 ] Wir haben also die Gedanken als einen Leichnam an uns, das heißt, eigentlich ist es die Kraft der Gedanken, nicht die Gedanken selbst, die wir haben. Wir können das noch genauer beschreiben. Allerdings, wenn Sie auf diese genauere Beschreibung eingehen wollen, werden Sie sehr exakte Vorstellungen entwickeln müssen. Diese geistige Kraft, die da in den Gedanken erstirbt und zum Leichnam wird, wenn der Mensch ins physische Erdendasein heruntersteigt, diese Kraft ist dieselbe, die aus dem Kosmos heraus unsere Organe bildet. Was wir als Lunge, Herz, Magen, also als die geformten Organe in uns tragen, das wird aus dieser Gedankenkraft des Weltenalls heraus gebildet. Wenn wir nun ins irdische Leben eintreten, dann geht in unseren engbegrenzten Organismus diese Gedankenkraft ein. Was will nun die Erde mit ihrer Umgebung von uns? Ja, die Erde mit ihrer Umgebung will eigentlich von uns, daß wir sie in uns nachbilden.

[ 20 ] Wenn wir das Irdische nachbilden würden, dann würden allmählich im Verlaufe unseres Lebens unsere inneren Organe, wie Lunge und vor allen Dingen die verschiedensten Windungen des Gehirns und so weiter, in kristallartige Gestalten verwandelt werden. Wir würden alle Bildsäulen werden, die aber nicht dem Menschen ähnlich wären, sondern die so wie Kristalle, die gegeneinander gruppiert sind, aussehen würden. Wir würden aus unorganischen, aus leblosen Gestalten allmählich zusammengesetzt sein und eine Art von Bildsäule werden. Dagegen stemmt sich der menschliche Organismus. Er bleibt bei der Form seiner inneren Organe. Er läßt zum Beispiel seine Lunge nicht umbilden zu einer Art von, sagen wir, Gebirgszügen. Er läßt sein Herz nicht umbilden zu einer Art Kristallgruppe. Er stemmt sich dagegen. Und in diesem Sich-dagegen-Stemmen liegt der Anlaß dazu, daß wir, statt mit unseren Organen diese irdische Umgebung nachzuformen, sie bloß in Schattenbildern in unseren Gedanken nachbilden. Also die Gedankenkraft ist eigentlich immer auf dem Wege, von uns ein Abbild unserer physischen Erde, unserer physischen Erdenform zu machen. Wir möchten fortwährend zu einem System von Kristallen werden. Aber das läßt unsere Organisation nicht zu. So viel hat sie in dem Lebendigen, in dem Mitfühlen, in dem Selbstgefühle, in den Willensimpulsen zu entfalten, daß sie das nicht zuläßt. Sie läßt unsere Lunge nicht umbilden, so daß sie aussieht wie Kristalle, die aus der Erde herauswachsen. Sie stemmt sich gegen dieses irdische Gestaltetwerden, und da kommen nur die Tafel 9

[ 21 ] Bilder der irdischen Gestalten dann zustande in der Geometrie, und was wir sonst uns an Gedanken bilden von unserer Erdenumgebung. Wie gesagt, es muß sehr exakt gedacht werden, wenn man zu dieser Vorstellung vorschreiten will.

[ 22 ] Eigentlich ist aber immerfort die Tendenz vorhanden, daß wir unserem Gedankensystem ähnlich werden. Wir müssen fortwährend dagegen kämpfen, daß wir ihm nicht ähnlich werden. Wir streben eigentlich fortwährend dahin, so eine Art Kunstwerk zu werden, das allerdings bei der Art der Gedanken, wie sie die Menschen meistens haben, nicht gerade ein sehr schönes Kunstwerk zum Anschauen gäbe. Aber wir streben dahin, der äußeren Gestalt nach dasselbe zu wirken, was unsere Gedanken eben im bloßen Bilde, im bloßen Schatten sind. Wir werden es nicht, sondern wir lassen es gewissermaßen zurückspiegeln, und dadurch wird es unser Gedanke. Es ist ein Prozeß, der sich wirklich vergleichen läßt mit dem Entstehen von Spiegelbildern.

[ 23 ] Wenn Sie hier einen Spiegel haben, davor einen Gegenstand, so wird dieser Gegenstand eben abgespiegelt. Er ist nicht da drinnen [Hier wird gezeichnet]. Alles, was vor unserem Auge steht, will eigentlich in uns fortwährend ein wirkliches Gebilde veranlassen. Aber wir stemmen uns dagegen, wir behalten unser Gehirn. Dadurch wird es zurückgespiegelt und wird das Gedankenbild. Ein Tisch will in Ihnen Ihr Gehirn selber zum Tisch machen; Sie lassen das nicht zu. Dadurch entsteht das Bild des Tisches in Ihnen. Das ist das Spiegeln, dieses Zurückwerfen der Tätigkeit. Dadurch aber stehen wir eben im Denken so da, daß unsere Gedanken nur die Schattenbilder der Außenwelt sind. Aber in unserem Gefühl, da haben wir schon etwas anderes gegeben. Versuchen Sie nur einmal sich richtig vorzustellen, was Sie mit Ihrem Fühlen haben. Sie fühlen anders einen runden Tisch als einen eckigen. Sie fühlen die Ecken. Der Gedanke des eckigen Dinges macht Ihnen nichts Besonderes aus, aber das Erfühlen der Ecken, das tut schon mehr weh, als wenn man nur in aller Ruhe die Rundung eines Tisches verfolgt. Also mit dem Fühlen leben wir in unserem Inneren schon mehr die äußere Form nach als mit den Gedanken.

[ 24 ] Damit ist hingedeutet auf die Metamorphose, die das SeelischGeistige durchmacht, wenn es vom vorirdischen Dasein ins irdische Dasein kommt. Wie ist es nun, wenn wir durch die Pforte des Todes gehen? Die Gedankenwelt, die wir haben, ist ja ihrer Kraft nach bloß der Leichnam des vorirdischen Daseins. Die hat eigentlich keine Bedeutung. Geradeso wie, wenn wir uns in einem Spiegel sehen und dann den Spiegel wegnehmen, das Bild fort ist, so ist unser Gedankenleben fort, indem wir durch die Pforte des "Todes gehen. Also, "wenn der Mensch von Unsterblichkeit spricht, so soll er nur ja nicht auf diese irdische Gedankenkraft reflektieren. Die ist es nicht, die mit ihm durch die Pforte des Todes geht. Dagegen alles das, was er als Mitgefühl, als Nachgefühl, als Nachempfindung des Irdischen entwickelt hat, das geht durch die Pforte des Todes. Also Mitgefühl geht durch die Pforte des Todes hindurch (siehe Schema). Und dadurch, daß wir Mitgefühl haben mit der Umwelt, entwickeln wir die Kraft, jetzt in der geistigen Welt in den Wesenheiten darinnenzustehen, in dem Element, das Geistesgedankenelement ist. Das Mitfühlen, das durch unsere Körperlichkeit abgetrennt ist von der irdischen Umgebung, strömt jetzt nach dem Tode hinaus in die geistige Umgebung und verbindet sich mit dem Gedanklich-Geistigen der Welt, in die wir eintreten, wenn wir durch die Pforte des Todes gehen. Also mit dem Gedanklich-Geistigen verbindet sich dasjenige, was wir an Mitgefühl empfinden.

[ 25 ] Und dadurch, daß wir gewissermaßen hinüberfließen mit unserem Mitfühlen in das Gedanklich-Geistige, entwickeln wir selber wiederum eine Art Gedankenleib, einen lebendigen Gedankenleib, der uns dann eigen ist zwischen dem Tode und der nächsten Geburt. Denn das, was im Leben Selbstgefühl ist, das entwickelt sich zum Drinnenstehen in andern Wesenheiten. Während wir durch unser Selbstgefühl im irdischen Leben uns nur innerhalb unserer Leiblichkeit wissen, lernen wir uns wissen in andern Wesen, in den Wesen der höheren Hierarchien, wenn wir durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen sind. Und indem wir in geistigen Wesen drinnenstehen, empfangen wir von diesen auch die Kräfte, die uns dann wiederum weiterleiten auf unserer Lebensbahn zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. So daß wir sagen können, das eigene Kräftewesen entwickelt sich auf diese Weise. Das ist die Metamorphose des Geistig-Seelischen, indem wir durch die Pforte des Todes hindurchgehen.

[ 26 ] Der Wille als solcher ist nicht etwa so - wie die Gedankenwelt -, daß er mit dem Tode verschwände, sondern er ist ja der Quell für den Inhalt unserer Selbstgefühle. Denken Sie einmal, Sie wollen etwas, das Sie befriedigt, dann gibt dieses Wollen schon etwas, das Sie befriedigt, gibt Ihrem Selbstgefühl eine bestimmte Nuance. Wenn Sie etwas getan haben, was Sie nicht befriedigt, gibt das auch Ihrem Selbstgefühl eine bestimmte Nuance. Der Wille ist nicht nur etwas, das nach außen die Tätigkeit vollzieht, sondern er strebt auch kraftvoll in unser Inneres zurück. Wir wissen, was wir sind, aus dem heraus, was wir können. Und diese Nuance des Selbstgefühles, dieses in uns selbst wiederum Zurückstrahlen des Willenselementes, das nehmen wir mit dem Selbstgefühl eben mit in die geistige Welt. Also der Wille, das heißt eigentlich die Zurückstrahlung des Willens in unser Selbstgefühl ist es, was wir hineintragen, indem wir untertauchen in die Wesenheiten der höheren Hierarchien. Und dadurch, daß wir das mitnehmen, was unser Selbstgefühl erhöht oder geschwächt hat, bildet sich die Kraft unseres Karma, unseres Schicksals. Wenn man diese Dinge überblickt, kann man hineinschauen in das, was der Mensch eigentlich ist. Und man lernt auch auf diese Art insbesondere gewisse Begleiterscheinungen des irdischen Lebens kennen. Im irdischen Leben tritt die Furcht gewiß da oder dort auf; aber niemals darf sie die ganze Seele ausfüllen, und es wäre traurig, wenn es so wäre. Bevor wir dagegen ins irdische Leben heruntersteigen, ist die ganze Seele von Furcht ausgefüllt, und diese Furcht ist die Kraft, die wir in diesem Zustande haben müssen, damit wir ins physische irdische Leben wirklich heruntersteigen.

[ 27 ] Das Selbstgefühl wiederum ist etwas, das im irdischen Leben nicht über eine gewisse Höhe hinaus gesteigert werden darf, was überhaupt eigentlich im irdischen Leben gar nicht selbständig empfunden werden sollte. Ein Mensch, der mit zu starker Selbständigkeit das Selbstgefühl entwickelt, der kennt eben nur sich. Das Selbstgefühl ist im irdischen Leben eigentlich nur dazu da, damit wir an unserer Leiblichkeit bis zum Tode festhalten, damit wir an jedem Morgen, wenn wir geschlafen haben, wiederum zurückkehren in unsere Leiblichkeit. Denn würden wir dieses Selbstgefühl nicht haben während unseres irdischen Lebens, so würden wir nicht wieder zurückkehren. Aber nach dem Tode brauchen wir es, wenn wir in die Welt der geistigen Wesenheiten untertauchen, denn wir würden uns sonst jederzeit verlieren. Wir müssen ja dort in reale geistige Wesenheiten untertauchen.

[ 28 ] Die Erde macht nicht diesen Anspruch an uns. Wenn Sie durch einen Wald gehen, dann bleiben Sie eben auf Ihrem Wege, und die Bäume sind links und rechts und vorne und hinten. Sie sehen die Bäume, aber die Bäume machen nicht den Anspruch, daß Sie in sie hineingehen, daß Sie fortwährend zur Baumnymphe werden und in die Bäume untertauchen. Aber die geistigen Wesenheiten der höheren Hierarchien, deren Welt Sie nach dem Tode betreten, die machen den Anspruch, daß wir in sie untertauchen. Wir müssen sie alle werden, diese Wesenheiten der geistigen Welt. Würden wir da nicht mit dem Selbstgefühl in diese geistige Welt hineingehen, wenn wir durch die Pforte des Todes treten, dann würden wir uns verlieren. Da brauchen wir das Selbstgefühl, einfach um uns zu erhalten. Und gerade auch die moralischen Dinge, die wir im Erdenleben verrichtet haben, die unser Selbstgefühl in berechtigter Weise erhöhen, die schützen uns davor, uns nach dem Tode als unser Selbst zu verlieren.

[ 29 ] Das sind Vorstellungen, die eigentlich wiederum eintreten müßten in das menschliche Bewußtsein von der Gegenwart ab nach der nächsten Zukunft der Erdenentwickelung hin. Diese Vorstellungen sind gewissermaßen der Menschheit in ältesten Zeiten während des instinktiven hellseherischen Erfassens schon zugeflossen. Die Menschen hatten einmal ein starkes Gefühl von dem, was sie waren, bevor sie zum irdischen Leben heruntergestiegen waren. Das war besonders stark entwickelt in den irdischen Urzeiten. Weniger entwickelt war in irdischen Urzeiten die Hoffnung auf ein Leben nach dem Tode. Das war etwas, das wie selbstverständlich hingenommen wurde. Geradeso aber, wie jetzt die Menschen sich hauptsächlich für ihr Erleben nach dem Tode interessieren, so interessierten sich die Menschen der irdischen Urzeit, die Menschen vor Jahrtausenden, für ihr Leben, bevor sie heruntergestiegen waren auf die Erde.

[ 30 ] Dann kam die Zeit, mit der sich dieses ursprünglich instinktive Hellsehen verlor, in der sich auch verlor das intensive Zusammenhängen der Seele mit ihrem vorirdischen Dasein. Und dann entsprangen die zwei Geistesströmungen, welche das vorbereitet haben, was eigentlich sich jetzt in der Menschheitszivilisation entwickeln mußte. Wir haben zwei deutlich voneinander verschiedene Strömungen, die wir von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus charakterisiert haben, und auf die wir heute von einem bestimmten Gesichtspunkte aus, der uns morgen und übermorgen bei unseren Betrachtungen wird dienen können, wiederum eingehen wollen.

[ 31 ] Nehmen Sie die irdische Entwickelung, bevor das Mysterium von Golgatha über die Erde hinging, dann haben Sie gewissermaßen ausgebreitet über die Erde die heidnische Kultur, und in einer gewissen Absonderung diejenige Kultur, die man die alttestamentliche nennen könnte. Was war denn dieser heidnischen Kultur besonders eigentümlich? Sie hatte durchaus noch ein Bewußtsein davon, daß in allem, was physisch den Menschen umgibt, auch Geistiges enthalten ist. Die heidnische Kultur hatte ein starkes Bewußtsein von dem, was lebendige Gedanken sind, die dann in uns zu toten Gedanken werden. Sie sah überall in den Wesen der verschiedenen Naturreiche das lebendige Element für das, wofür die menschlichen Gedanken das tote Element sind. Die heidnische Welt nahm also die lebendigen Gedanken der Welt wahr, sie betrachtete den Menschen auch als angehörig diesen lebendigen Gedanken der Welt.

[ 32 ] Nun war ein besonders lebensvoll entwickelter Teil dieser heidnischen Welt die des alten Griechenvolkes. Sie wissen ja, daß die Welt des alten Griechenvolkes stark durchdrungen war von dem Schicksalsgedanken. Und - erinnern Sie sich an gewisse griechische Dramen - dieser Schicksalsgedanke durchstrahlt das menschliche Leben mit einer Gesetzmäßigkeit, ich möchte sagen wie die Naturgesetze die Natur. Der Grieche fühlte sich in der Natur durchaus so drinnenstehend, daß in ihn herein das Schicksal spielte, wie in die Naturtatsachen die Naturgesetze spielen. Das Schicksal trifft den Menschen innerhalb der griechischen Anschauung mit Naturgewalt. Das war aber die Eigentümlichkeit jeder heidnischen Vorstellung, sie kam nur bei den Griechen in ganz bedeutsamer Weise zum Ausdruck. Die heidnische Welt sah den Geist in allem Naturdasein. Sie hatte keine besondere Naturwissenschaft, die so gewesen wäre wie die unsrige, aber sie hatte eine ausgebreitete Naturwissenschaft. Sie redete überall, wo sie die Natur erblickte, von Geistigem. Das war die Naturwissenschaft, die zu gleicher Zeit eine Geisteswissenschaft war. Der Heide sah weniger auf das menschliche Innere. Er sah den Menschen auch wie ein Naturwesen von außen an, aber er konnte das, weil er auch die übrigen Naturwesen nicht seelenlos dachte. Er dachte den Baum, die Pflanzen, die Wolken nicht seelenlos. So brauchte er auch den Menschen nur von außen anzuschauen und ihn doch nicht seelenlos zu denken. Der alte Heide konnte also, indem er die Natur beseelte, auch den Menschen als Naturwesen betrachten, und so war das alte Heidentum ein Element, das von vorneherein ein Spirituelles in sich hatte, das zum Geiste hinneigte. Dem stand schroff entgegen als der andere Pol das Bekenntnis, das dann im Alten Testament sich ausgelebt hat.

[ 33 ] Das Alte Testament kannte die Natur eigentlich weder in dem Sinne, wie wir die Natur kennen - ich meine, indem wir wiederum zur Geisteswissenschaft zurückkehren -, noch in dem Sinne, wie das Heidentum die Natur gekannt hat. Das Alte Testament kannte eigentlich nur eine moralische Weltordnung, und Jahve ist der Herrscher über diese moralische Weltordnung, und es geschieht das, was Jahve will. So daß innerhalb dieser Welt des Alten ’Testamentes eigentlich in ganz selbstverständlicher Weise die Anschauung entstand, man soll sich gar kein Bild machen von dem, was seelisch-geistig ist; eine Anschauung, die das Heidentum nie hätte haben können, denn das Heidentum hat in jedem Baume, in jeder Pflanze Bilder gesehen von dem Geistigen. Der Bekenner des Alten Testamentes hat nirgends Bilder gesehen, dagegen überall das Walten des unsichtbaren, bildlosen Geistigen.

[ 34 ] Im Neuen Testamente sollte man eigentlich einen Zusammenschluß dieser beiden Geistesströmungen erkennen. Es ist immer so gewesen, daß in den Anschauungen der Menschen das eine oder das andere Element vorwiegend war. So ist zum Beispiel das heidnische Element immer vorwiegend gewesen da, wo mehr anschauliche religiöse Bekenntnisse gepflogen worden sind. Da machte man sich Bilder von geistigen Wesenheiten, die Naturbildungen nachgeahmt waren. Dagegen bildete sich das alttestamentliche Element überall da aus, wo die neuere Wissenschaftlichkeit heraufkam, wo man auf das Bildlose hinstrebte. Und in der neueren materialistischen Wissenschaft lebt in vieler Beziehung ein Nachklang gerade des Alten Testamentes, des unbildhaften Alten 'Testamentes. Man möchte sagen, der Materialismus der Wissenschaft, der will streng sondern das Materielle, dem er nun gar keinen Geist mehr läßt, und das Geistige, das nur im Moralischen leben soll, von dem man sich gar kein Bild machen darf, das also auch nicht gesehen werden darf in dem Irdischen.

[ 35 ] Diese besondere Charakteristik des Wissenschaftlichen, der wir heute in der materialistischen Form der Wissenschaft begegnen, ist eigentlich noch ein in unsere Zeit hereinragender Impuls des Alten Testamentes. Die Wissenschaft ist noch gar nicht christlich geworden. Die Wissenschaft als Materialismus ist im Grunde genommen heute noch alttestamentlich. Und das wird eine der Hauptaufgaben der fortschreitenden Zivilisation sein, beides zu überwinden, aber auch beides synthetisch in eine höhere Einheit auflösen zu können. Wir müssen uns schon klar darüber sein, daß sowohl das Heidentum wie das Judentum Einseitigkeiten darstellen und daß sie, indem sie vielfach hereinragen in die neuere Zeit, ein zu Überwindendes darstellen.

[ 36 ] Die Wissenschaft wird zum Geiste kommen müssen. Die Kunst, die vielfach etwas Heidnisches hat, die verschiedene Ansätze gemacht hat zum Christlichwerden, Ansätze, die aber meistens ins Luziferisch-Heidnische ausgeschlagen sind, die Kunst wird einlaufen müssen in ein christliches Element. Wir haben heute eigentlich noch immer die Nachwirkungen des heidnischen und des alttestamentlichen Elementes und haben noch nicht ein voll ausgebildetes christliches Bewußtsein. Das ist es, was wir insbesondere fühlen müssen, wenn wir uns auf diese konkreten Durchgänge des Menschen durch Geburt und Tod besinnen, so wie sie uns von der Geisteswissenschaft gegeben werden.

[ 37 ] Auf der Grundlage dessen, was ich nun heute vor Ihnen entwickelt habe, werde ich morgen einiges Historisches im geisteswissenschaftlichen Sinne zur Darstellung zu bringen versuchen.

On the passage of the human spirit-soul being through the physical-sensory organization

[ 1 ] Today we want to consider the passage of the human spirit-soul being through the physical-sensory organization, namely how this spirit-soul first prepares itself for physical incarnation by descending from the spiritual worlds, and then how it passes out again through the gate of death from physical-sensory incarnation into the spiritual world. And today we want to pay particular attention to the soul characteristics of this process. We must be clear that when entering the physical organization, and indeed already at conception, a tremendous change takes place, and that another tremendous change occurs when the human being leaves physical incarnation through the gate of death.

[ 2 ] We have already characterized this from various points of view, but today we want to turn our attention to the inner experience of the soul as such. We want to ask ourselves: What are the last experiences of the soul before it descends into physical life on earth?

[ 3 ] When we observe the soul between birth and death, we find it interwoven in the most diverse ways with thoughts, feelings, and impulses of the will. All of this interacts to form an overall soul picture. And we also have special terms for the individual thought forms, for the forms of feeling, for the forms of will impulses, and we know from what is experienced soulfully in physical earthly life how to characterize certain types of feelings. By starting from more subconscious emotional experiences and soul experiences in general, we can at least shed some light on what lives in the soul before it enters earthly life.

[ 4 ] First of all, we must realize that the thought element as such lives in the soul during physical earthly existence like a shadow. Thoughts are rightly called pale and abstract. Most of what human beings produce in the way of thoughts and ideas during earthly life is ultimately nothing more than a reflection of the external world. Human beings imagine what they have perceived in the external world through their senses, and you know that very little remains when you subtract from your thought life everything that has been perceived through the senses or otherwise experienced in the presence of the senses during physical life on earth, unless a study of spiritual science has led you to to obtain thought content other than that which has been drawn from the sensory world. But this shadowy world of thoughts is shadowy precisely because it has lost its inner vitality in descending into the physical-sensory world. Precisely that which is the thought experience within us is a lively, self-moving, self-contained life before its descent into the physical world. One can say that what actually lives in the thoughts is to what appears as thoughts during our earthly existence as the full earthly form is to the shadow it casts on the wall. And when we move from the earthly thoughts we have between birth and death to the true form of thought life, these thoughts are actually only present in purely spiritual life before conception. It is just as when we go from a shadow on the wall to what it represents. There is a lively inner, fully living existence precisely in what later become shadowed thoughts, existing before birth or before conception. We can certainly describe what exists in the world of thoughts before conception as inner soul weaving and life as the actual spiritual existence, as the actual spiritual essence. This inner soul weaving and life is, of course, something that permeates the entire universe known to us before conception. Before conception, we actually live in the whole world that otherwise surrounds us, and what then exists as thought in human beings during earthly life is the shadow image in the small space, in the human physical organism, of what actually has cosmic life before conception.

[ 5 ] This is how we describe the one element of the soul before birth or before conception. What is thought in the earthly realm and what is actually spiritual in the extraterrestrial realm of the human being, we find before the human being descends into the physical world as the content of the soul. The other element of the soul's content cannot be described in any other way, if we want to use concepts from earthly life, than by saying: it is fear. In the soul, in the time that precedes physical life on earth, there lives something that permeates it completely as fear. Of course, when something like this is said, you must be clear that fear as an experience outside the physical body is something completely different from fear in the physical human body.

[ 6 ] Before descending to earth, the human being is therefore a spiritual-soul being, permeated by an emotional element that can only be compared to something that humans experience as fear in earthly life. This fear is well justified for the period of human life I am talking about. In the life between death and a new birth, the human being has had all kinds of experiences that are possible in this cosmic connection with the universe. The human being has, so to speak, grown tired of this cosmic life at the end of its existence between death and a new birth, just as the human being is tired of earthly life through the withering and paralysis of its physical organization at the end of its earthly life. Human beings have, in a sense, grown tired of extraterrestrial life. And this weariness does not express itself as weariness, but as fear of the universe. Human beings flee, in a sense, from the universe. They perceive what is the fundamental nature of the universe as something that has now become alien to them, that no longer gives them anything; they feel a kind of shyness, comparable to fear, toward the element in which they exist. They want to pull themselves out of this feeling of being in the universe and withdraw into what constitutes human physicality.

[ 7 ] Now, what presents itself to man from the earth is something that, in a certain sense, exerts a kind of attraction toward this state of fear in which man finds himself when he approaches earthly existence again. If I were to draw a schematic diagram of this, I would have to do so in the following way: Imagine the skull with the brain inside it. That is the base of the skull. Now, what forms itself in the shapes of the brain, what appears as such strange convolutions, is, as I have already indicated in various ways, a kind of reproduction of the starry sky, of the universe, in the human organism. Inside this cellular structure of the brain, the starry sky is truly reproduced (see drawing). And since human beings lived in the universe outside, in the world of the stars, before coming down to earth, they embraced this starry universe in their spirituality. But now they fear it. They withdraw into what is like an earthly image of this starry space in the human brain.

[ 8 ] And this brings us to what could be called the choice made by the spiritual-soul. The soul goes to the brain that is in the process of formation and which most closely resembles the constellation of stars in which the soul stood before descending into the earthly realm. It is natural that the brain of one embryo is a different image of the starry sky than that of another embryo. However, the soul is attracted to the brain that most closely resembles the constellation of stars in which the soul was before it descended to earth.

[ 9 ] It is therefore essentially a kind of fear that leads the soul down into the narrow human space, a fear of the infinite, one might say. This fear is the more soulful part. The world of thoughts, which then gradually unfolds from childhood to adulthood, is the spiritual. In the process, both this feeling of fear and the spiritual, which then becomes the shadows of thoughts, undergo a significant metamorphosis. I would like to characterize this metamorphosis for you. One can only use expressions that are unfamiliar to ordinary imagination; but then, today's ordinary imagination has no points of reference for describing these things. They lie beyond everything that belongs to this realm, and so we must use unfamiliar expressions if we want to adequately describe things that are so far removed from today's ideas.

[ 10 ] So we first have the spiritual element that lives in the universe, which enters, as it were, into the narrow dwelling of the human body, unfolds itself through the nervous system and the brain, and in the process must undergo a metamorphosis. In doing so, it divides into two regions. One can truly say that what the human being is in the spiritual-soul world before conception dies when it passes into physical corporeality. Birth into physical corporeality is a dying for the spiritual-soul life of the human being. When something dies, a corpse always remains. Just as when a human being dies for the earth, the corpse remains, so too does a corpse remain when the spiritual-soul life, in passing through conception to the earth — if I may use the expression — dies for the heavenly. It is from what now remains as a corpse that we actually live through our entire earthly life in thought. The corpse is, in fact, the world of thoughts; the dead is this shadow world. So we can say: when the spiritual part of the human being descends into earthly life through conception, it dies for the spiritual-soul world and leaves this corpse behind.

[ 11 ] Just as the physical corpse dissolves into earthly elements, so the spiritual-soul life dissolves into the spiritual world and becomes the force that unfolds in physical thoughts. The world of thoughts is the corpse of our spiritual soul. Just as the earth processes the corpse when we place it in the earth, or as fire processes it when we burn it, so we process the corpse of our spiritual soul throughout our entire life in our physical world of thoughts. So the physical world of thoughts is basically the continuing death of what exists as reality, as spiritual life, before human beings descend into physical earthly existence.

[ 12 ] The other thing that enters into human beings as living from their pre-earthly existence does not come to expression in the physical human being through the world of thoughts, but in the widest sense through everything we can call feeling, both feeling for other human beings and feeling for nature. So everything through which you spread yourself into the outer world by feeling and sensing is an element that represents the living after-effect of pre-earthly existence (see diagram on p. 97).

[ 13 ] It is not in your thoughts that you experience your pre-earthly existence in a living way, but in your feelings toward other beings. When we love a flower, when we love a human being, this is essentially a force given to us from our pre-earthly existence, but in a living way. So we can also say that when we love a person, for example, we do not love them merely from experiences in earthly life, but also from karma, from connections in previous earthly lives. Something living is carried over from pre-earthly existence when the compassionate sphere of the human being comes into play. On the other hand, what is the living spirit element between death and a new birth dies into the world of thoughts. That is why the world of thoughts has this pale, shadowy, dead quality during earthly existence, because it actually represents the dead part of man's pre-earthly experiences.

[ 14 ] The second is what must be called fear, and this also undergoes a metamorphosis, dividing into two elements. The one, that is, what we experience as fear before descending into the earthly world, which pervades the soul and causes it to want to flee the spiritual world, becomes something else when it enters the body, and this initially manifests itself within the human being as something I would like to call self-awareness. Self-awareness is really transformed fear. The fact that you feel yourself as a self, that you hold yourself within yourself, is transformed fear from pre-earthly life.

[ 15 ] And the other part into which fear is transformed is the will. Everything that appears as impulses of the will, everything that underlies our activity in the world, all of that exists as fear before we descend into earthly life.

[ 16 ] You see, here again, a good thing is done for human beings in earthly life by the fact that in ordinary consciousness they do not pass beyond the guardian of the threshold. I have often said that what the will actually represents down there in the human organism is something that human beings sleep through. Human beings have the intention of their will, then they carry out their will; then he has the idea of the results. But what lies between these two worlds of ideas, between the intention to carry out an action and the completed action, that is, what actually lives in the will, is initially overslept by man, just as he oversleeps the states between falling asleep and waking up. If a person were to look down into what lies at the basis of their will, they would feel fear rising up from their organism, coming in from their pre-earthly life.

[ 17 ] This is also what must be overcome during initiation. When you look inside yourself, the first thing you see is your sense of self. This is something that should not be overly encouraged through education, lest you fall into megalomania when you enter the spiritual world. But at the root of your impulses of will, you will find fear everywhere, and you must be strengthened against this fear.

[ 18 ] Essentially, you will therefore see that everywhere in the exercises given in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds” the aim is to endure the fear that is perceived in the manner just described. This fear is something that must exist among the forces of development, otherwise human beings would never descend from the spiritual world into earthly existence. He would not flee from the spiritual world. He would not develop the impulse to enter into a limited physical human body. The fact that he does so is precisely because he has a fear of the spiritual world as a completely natural characteristic of the soul when he has lived for a time between death and a new birth.

[ 19 ] So we have thoughts as a corpse within us, that is, it is actually the power of thoughts, not the thoughts themselves, that we have. We can describe this in more detail. However, if you want to go into this more detailed description, you will have to develop very precise ideas. This spiritual force, which dies in the thoughts and becomes a corpse when the human being descends into physical earthly existence, is the same force that forms our organs out of the cosmos. What we carry within us as lungs, heart, stomach, that is, as formed organs, is formed out of this thought force of the universe. When we enter earthly life, this thought force enters our narrowly limited organism. What does the earth with its environment want from us? Yes, the earth with its environment actually wants us to reproduce it within ourselves.