Old and New Methods of Initiation

GA 210

18 February 1922, Dornach

Lecture IX

Let us recall the main points we considered yesterday. Through conception and birth into the physical, sense-perceptible world, the human being brings down on the one hand something which inwardly still possesses the living spiritual world, but which then becomes shaded and toned down to the thought world he bears within him. On the other hand he brings down something which fills his element of soul and spirit, something which I have described as being essentially a state of fear. I then went on to point out that the living spirit is metamorphosed into a thought element, but that it also sends into earth existence a living remnant of pre-earthly life that lives in human sympathy. So in human sympathy we have something that maintains in our soul the living quality of pre-earthly existence. The feeling of fear that fills our soul before we descend to the physical world is metamorphosed here on earth on the one hand into the feeling of self and on the other into the will.

What lives in the human soul by way of thoughts is dead as far as spirit and soul are concerned, compared with the living world of the spirit. In our thoughts, or at least in the force which fills our thoughts, we experience, in a sense, the corpse of our spirit and soul existence between death and a new birth. But our present experience during physical earthly life, of a soul that has—in a way—been slain, was not always as strong as it is today. The further we go back in human evolution the greater is the role played here in earthly life by what I yesterday described as sympathy—sympathy not only with human beings but also for instance with the whole of nature. The abstract knowledge we strive for today—quite rightly, to a certain extent—has not always been present in human evolution. This abstract inner consciousness came into being in its most extreme form in the fifteenth century, that is, at the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean period. What human beings now experience in their thoughts was, in earlier times, filled with living feelings. In older knowledge—for instance, that of the Greek world—abstract concepts as we know them today simply did not exist. Concepts then were filled with living feelings. Human beings felt the world as well as thinking it. Only at the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean period did people begin to merely think the world, reserving their feelings of sympathy for what is really only the social realm.

In ancient India human beings felt strong sympathy for the whole of nature, for all the creatures of nature. Such strong sympathy in earthly life means that there is a strong experience of all that takes place around the human being between death and a new birth. In thinking, this life has died. But our sympathy with the world around us certainly contains echoes of our perceptions between death and a new birth. This sympathy was very important in the human life of earlier times. It meant that every cloud, every tree, every plant, was seen to be filled with spirit. But if we live only in thoughts, then the spirit departs from nature, because thoughts are the corpse of our spirit and soul element. Nature is seen as nothing more than a dead structure, because it can only be mirrored in dead thoughts. That is why, as times moved nearer to our own, all elemental beings disappeared from what human beings saw in nature.

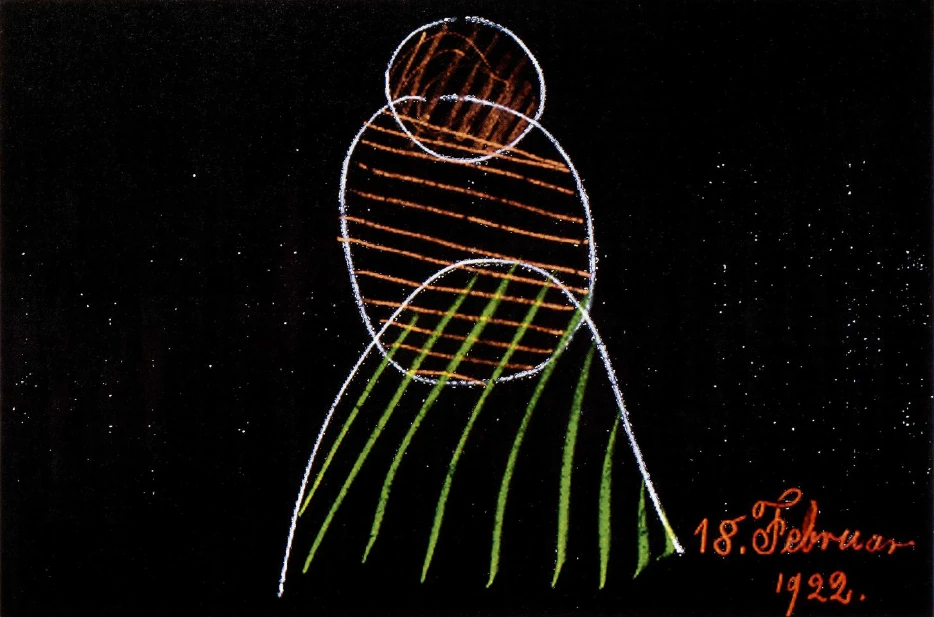

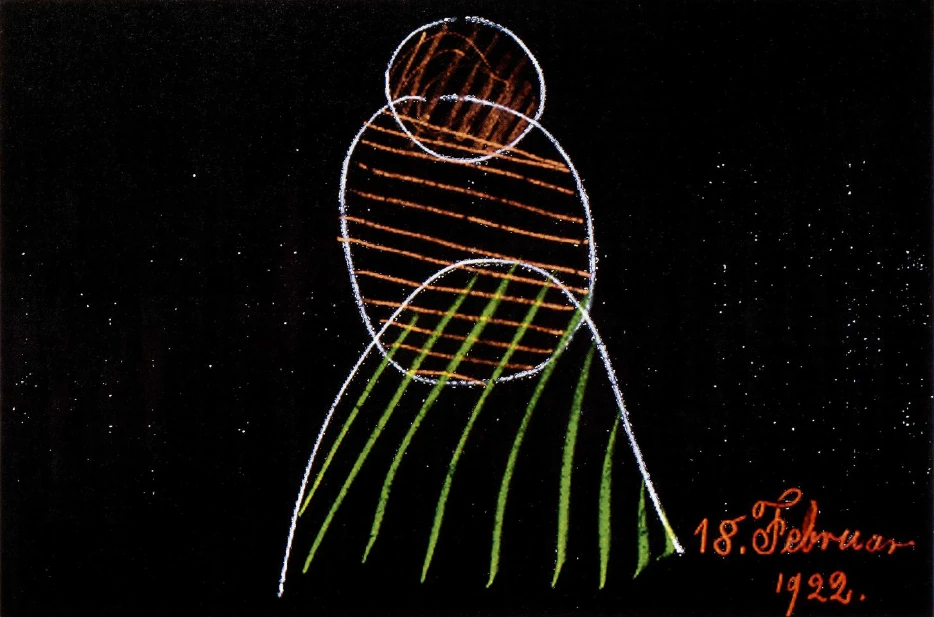

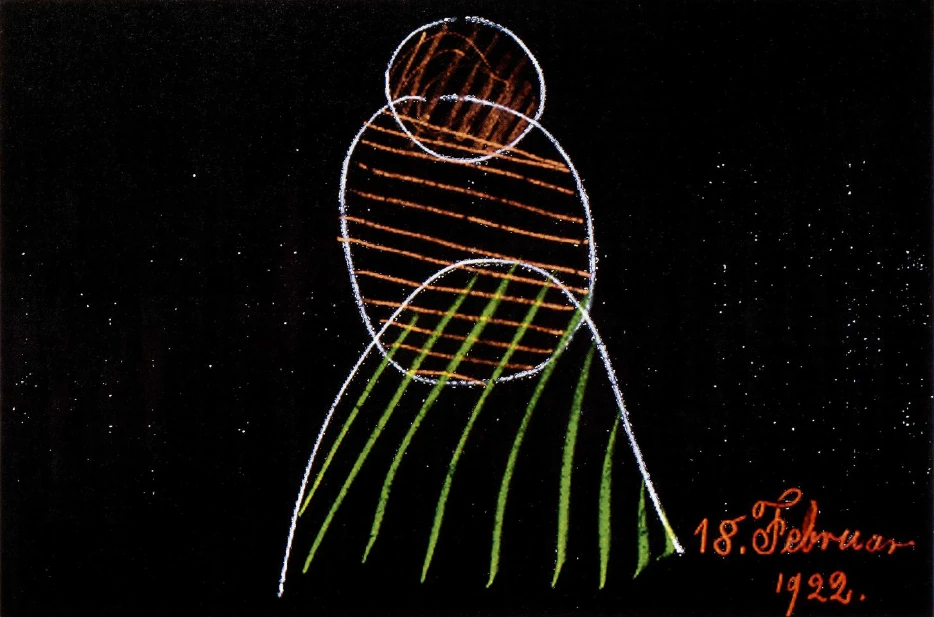

So what is this kind of spirituality that human beings still feel within themselves—this living spirituality—when, in reality, they ought to experience nothing but dead spirituality? To answer this question we shall have to consider what I have said with regard to the physical organization of the human being as a threefold organism. Here (see diagram) is the organism of nerves and senses, located mainly in the head. The rhythmical organism is located mainly in the upper chest organs. But of course both systems appear in the total organism too. And here is the organism of the limbs and the metabolism, which is located mainly in the limbs and the lower parts of the trunk.

Let us look first at the head organization which is chiefly, though not exclusively, the bearer of our life of nerves and senses. We can only understand it if we look at it pictorially. We have to imagine that our head is for the most part a metamorphosis—not in its physical substance, but in its form—of the rest of the body, of the organism of limbs and metabolism we had in our previous incarnation on the earth.

The organism of limbs and metabolism of our previous earthly life—not its physical substance, of course, but its shape—becomes our head organization in this life. Here in our head we have a house which has been formed out of a transformation of the organism of limbs and metabolism from our former incarnation, and in this head live mainly the abstract thoughts (see next diagram, red) which are the corpse of our pre-earthly life of soul and spirit.

In our head we bear the living memory of our former earthly life. And this is what makes us feel ourselves to be an ego, a living ego, for this living ego does not exist within us. Within us are only dead thoughts. But these dead thoughts live in a house which can only be understood pictorially; it is an image arising out of the metamorphosis of our organism of limbs and metabolism from our former earthly life.

The more living element that comes over from the life of spirit and soul, when we descend into a new earthly life, takes up its dwelling from the start not in our head, but in our rhythmical organism. Everything that surrounded us between death and this new birth and now plays into life—all this dwells in our rhythmical organism. In our head all we have is an image out of our former earthly life, filled with dead thoughts. In our rhythmical, breast organism lives something much more alive. Here there is an echo of everything our soul experienced while it was moving about freely in the world of spirit and soul between death and this new birth. In our breathing and in our blood circulation something vibrates—forces that belong to the time between death and birth. And lastly, our being of spirit and soul belonging to our present earthly incarnation lives—strange though this may seem—not in our head, and not in our breast, but in our organism of limbs and metabolism. Our present earthly ego lives in our organism of limbs and metabolism (green).

Imagine the dead thoughts to be still alive. These dead thoughts live—speaking pictorially—in the convolutions of the brain. And the brain in turn lives in a metamorphosis of our organism from our former incarnation. The initiate perceives the way the dead thoughts dwell in his head, he perceives them as a memory of the reality of his former incarnation. This memory of your former incarnation is just as though you were to find yourself in a darkened room with all your clothes hanging on a rail. Feeling your way along, you come, say, to your velvet jacket, and this reminds you of the occasion when you bought it. This is just what it is like when you bump into dead thoughts at every turn. To feel your way about in whatever is in your head organization is to remember your former life on earth.

What you experience in your breast organism is the memory of your life between death and a new birth. And what you experience in your limbs and metabolism—this belongs to your present life on earth. You only experience your ego in your thoughts because your organism of limbs and metabolism works up into your thoughts. But it is a deceptive experience. For your ego is not, in fact, contained in your thoughts. It is as little in your thoughts as you are actually behind the mirror when you see yourself reflected in it. Your ego is not in your thought life at all. Because your thought life shapes itself in accordance with your head, the memory of your former earthly life is in your thought life. In your head you have the human being you were in your former life. In your breast you have the human being who lived between death and this new birth. And in your organism of limbs and metabolism, especially in the tips of your fingers and toes, you have the human being now living on the earth. Only because you also experience your fingers and toes in your brain do your thoughts give you an awareness of this ego in your earthly life. This is how grotesque these things are, in reality, in comparison with what people today usually imagine.

Thinking with the head about what happens in the present time is something that only became prevalent at the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean period, in the fifteenth century. But in an ahrimanic way things are forestalled. Things that take place later than they should in the course of evolution are luciferic. Things that come too soon are ahrimanic. Let us look at something which came about in history very much too soon and should not have happened until the fifteenth century. It did happen in the fifteenth century, but it was foreshadowed at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha. I want to show you how the ideas of the Old Testament, which I partly described yesterday, were transformed into nothing more than allegories by a contemporary of Christ Jesus, Philo of Alexandria.1 Philo of Alexandria, c.20 B.C. – c.40 A.D. Jewish philosopher and theologian.

Philo of Alexandria interprets the whole of the Old Testament as an allegory. This means that he wants to make the whole Old Testament, which is told in the form of direct experiences, into a series of thought images. This is very clever, especially as it is the first time in human evolution that such a thing has been done. Today it is not all that clever when the theosophists, for instance, interpret Hamlet by saying that one of the characters is Manas, another Buddhi, and so on, distorting everything to fit an allegory. This sort of thing is, of course, nonsense. But Philo of Alexandria transformed the whole of the Old Testament into thought images, allegories. These allegories are nothing other than an inner revelation of dead soul life, soul life that has died and now lies as a corpse in the power of thinking. The real spiritual vision, which led to the Old Testament, looked back into life before birth, or before conception, and out of what was seen there the Old Testament was created.

But when it was no longer possible to look back—and Philo of Alexandria was incapable of looking back—it all turned into dead thought images. So in the history of human evolution two important events stand side by side: The period of the Old Testament culminated in Philo of Alexandria at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha. He makes allegories of straw out of the Old Testament. And at the same time the Mystery of Golgotha reveals that it is not the experience of dead things that can lead the human being to super-sensible knowledge, but the whole human being who passes through the Mystery of Golgotha bearing the divine being within him.

These are the two great polar opposites: the world of abstraction foreshadowed in an ahrimanic way by Philo, and the world which is to enter into human evolution with Christianity. The abstract thinker—and Philo of Alexandria is perhaps the abstract thinker of the greatest genius, since he foreshadowed in an ahrimanic way the abstractness of later ages—the abstract thinker wants to fathom the mysteries of the world by means of some abstract thought or other which is supposed to provide the answer to the riddle of the universe. The Mystery of Golgotha is the all-embracing living protest against this. Thoughts can never solve the riddle of the universe because the solution of this riddle is something living. The human being in all his wholeness is the solution to the riddle of the universe. Sun, stars, clouds, rivers, mountains, and all the creatures of the different kingdoms of nature, are external manifestations which pose an immense question. There stands the human being and, in the wholeness of his being, he is the answer.

This is another point of view from which to contemplate the Mystery of Golgotha. Instead of confronting the riddle of the universe with thoughts in all their deadness, confront the whole of what man can experience with the whole of what man is.

Only slowly and gradually has mankind been able to find the way towards understanding this. Even today it has not yet been found. Anthroposophy wants to open the gate. But because abstraction has become so firmly established, even the awareness that the way must be sought has disappeared. Until abstraction took hold, human beings did wrestle with the quest for the way, and this is seen most clearly at the turn of the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period. As Christianity spreads externally, the best spirits wrestle to understand it inwardly.

Both streams had come down from the far past. On the one side there was the heathen stream which was fundamentally a nature wisdom. All natural creatures were seen to be inhabited by elemental spirits, demonic spirits, those very demonic spirits who, in the Gospels, are said to have rebelled when Christ came amongst mankind, because they knew that their rule was at an end. Human beings failed to recognize Christ, but the demons recognized him. They knew that he would now take possession of human hearts and human souls and that they would have to withdraw. But for a long time they continued to play a role in the minds and hearts of human beings as well as in their search for knowledge. Heathen consciousness, which sought the demonic, elemental spirits in all creatures in the old way, continued to play a role for a long time. It wrestled with that other form of knowledge which now sought in all earthly things the substance of Christ that had united with the earth through the Mystery of Golgotha.

This heathen stream—a nature wisdom, a nature Sophia—saw the spirit everywhere in nature and could therefore also look at man as a natural creature who was filled with spirit, just as all nature was filled with spirit. In its purest, most beautiful form we find it in ancient Greece, especially in Greek art, which shows us how the spirit weaves through human life in the form of destiny, just as the natural laws weave through nature. We may sometimes recoil from what we find in Greek tragedies. But on the other hand we can have the feeling that the Greeks sensed not only the abstract laws of nature, as we do today, but also the working of divine, spiritual beings in all plants, all stones, all animals, and therefore also in man. The rigid necessity of natural laws was shaped into destiny in the way we find it depicted, for instance, in the drama of Oedipus. Here is an intimate relationship between the spiritual existence of nature and the spiritual existence of man. That is why freedom and also human conscience as yet play no part in these dramas. Inner necessity, destiny, rules within man, just as the laws of nature rule the natural world.

This is the one stream as it appears in more recent times. The other is the Jewish stream of the Old Testament. This stream possesses no nature wisdom. As regards nature, it merely looks at what is physically visible through the senses. It turns its attention upwards to the primal source of moral values which lies in the world between death and a new birth, taking no account of the side of man which belongs to nature. For the Old Testament there is no nature, but only obedience to divine commandments. In the Old Testament view, not natural law, but Jahve's will governs events. What resounds from the Old Testament is imageless. In a way it is abstract. But setting aside Philo of Alexandria, who makes everything allegorical, we discern behind this abstract aspect, Jahve, the ruler who fills this abstraction with a supersensibly focused, idealized, generalized human nature. Like a human ruler, Jahve himself is in all the commandments which he sends down to earth. This Old Testament stream directs its vision exclusively to the world of moral values; it absolutely shies away from looking at the externally sense-perceptible aspect of the world. While the heathen view saw divine spiritual beings everywhere, the god of the Jews is the One God. The Old Testament Jew is a monotheist His god, Jahve, is the One God, because he can only take account of man as a unity: You must believe in the One God, and you shall not depict this One God in any earthly manner, not in an idol, not even in a word. The name of God may only be spoken by initiates on certain solemn occasions. You must not take the name of your God in vain.

Everything points to what cannot be seen, to what cannot come to expression in nature, to what can only be thought. But behind the thought in the Old Testament there is still the living nature of Jahve. This disappears in the allegories of Philo of Alexandria.

Then came the early Christian struggles—right on into the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth centuries—to reach a harmony between what can be seen as the spirit in external nature and what can be experienced as the divine when we look at our own moral world, our own human soul. In theory the matter seems simple. But in fact the quest for harmony, between seeing the spirit in external nature and guiding the soul upwards to the spiritual world out of which Christ Jesus had descended, was an immense struggle. Christianity came over from Asia and took hold of the Greek and Roman world. In the later centuries of the Middle Ages we see the struggle taking place most strongly in those parts of Europe, which had retained much of their primeval vitality. In ancient Greece the old heathen element was so strong that although Christianity passed through Greek culture and assimilated many Greek expressions on the way, it could not take root there. Only Gnosis, the spiritual view of Christianity, was able to take root in Greece.

Next, Christianity had to pass through the most prosaic element of world evolution: Roman culture. Being abstract, Roman culture could only comprehend the abstract, as it were foreshadowing in an ahrimanic way what is later alive in Christianity. A truly living struggle then took place in Spain. Here, a question was asked which was not theoretical but vital, intensely alive: How can man, without losing sight of the spirit in natural creatures and processes, find the whole human being revealed to him by Christ Jesus. How can man be filled with Christ? This question lived most strongly in Spain, and we see in Calderón2 Pedro Calderön de la Barca, 1600-1681. Greatest Spanish dramatist. The drama about Cyprianus, El mägico prodigioso (The Miracle-working Magician) was written in 1637. The story was taken from a late version of an old tale in the Golden Legend. It is set in Antioch at the time of the Roman Emperor Decius. a poet who knew how to depict this struggle with great intensity. The struggle to fill the human being with Christ lived—if I may put it like this—dramatically in Calderón.

Calderón's most characteristic drama in this respect is about Cyprianus, a kind of miracle-working magician; in other words he is, in the first instance, a person who lives in natural things and natural processes because he seeks the spirit in them. A later metamorphosis of this character is Faust, but Faust is not as filled with life as is Calderón's Cyprianus. Calderón's portrayal of how Cyprianus stands in the spirit of nature is still filled with life. His attitude is taken absolutely for granted, whereas in the case of Faust everything is shrouded in doubt. From the start, Faust does not really believe that it is possible to find the spirit in nature. But Calderón's Cyprianus is, in this respect, a character who belongs fully to the Middle Ages. A modern physicist or chemist is surrounded in his laboratory by scientific equipment—the physicist by Geissler tubes and other things, the chemist by test tubes, Bunsen burners and the like. Cyprianus, on the other hand, stands with his soul surrounded by the spirit, everywhere flashing out and spilling over from natural processes and natural creatures.

Characteristically, a certain Justina enters into the life of Cyprianus. The drama depicts her quite simply as a woman, but to see her solely as a female human being is not to see the whole of her. These medieval poets are misunderstood by modern interpretations which state that everything simply depicts the material world. They tell us, for instance, that Dante's Beatrice is no more than a gentle female creature. Some interpretations, on the other hand, miss the actual situation by going in the opposite direction, lifting everything up allegorically into a spiritual sphere. But at that time the spiritual pictures and the physical creatures of the earth were not as widely separated as they are in the minds of modern critics today. So when Justina makes her debut in Calderón's drama, we may permit ourselves to think of the element of justice which pervades the whole world. This was not then as abstract as it is now, for now it is found between the covers of tomes which the lawyers can take down from their shelves. Jurisprudence was then felt to be something living.

So Justina comes to Cyprianus. And the hymn about Justina which Cyprianus sings presents another difficulty for modern scientific critics. Modern lawyers do not sing hymns about their jurisprudence, but Cyprianus sensed that the justice which pervades the world was something to which he could sing hymns. We cannot help repeating that spiritual life has changed. Now Cyprianus is at the same time a magician who has dealings with the spirits of nature, that world of demons among whose number the medieval being of Satan can be counted. Cyprianus feels incapable of making a full approach to Justina, so he turns to Satan, the leader of the nature demons, and asks him to win her for him.

Here we have the deep tragedy of the Christian conflict. What approaches Cyprianus in Justina is the justice which is appropriate for Christian development. This justice is to be brought to Cyprianus, who is still a semi-heathen nature scholar. The tragedy is that out of the necessities of nature, which are rigid, he cannot find Christian justice. He can only turn instead to Satan, the leader of the demons, and ask him to win Justina for him.

Satan sets about this task. Human beings find it difficult to understand why Satan—who is, of course, an exceedingly clever being—is ever and again prepared to tackle tasks at which he has repeatedly failed. This is a fact. But however clever we might consider ourselves to be, this is not the way in which to criticize a being as clever as Satan. We should rather ask ourselves what it could be that again and again persuades a being as clever as Satan to try his luck at bringing ruin on human beings. For of course ruin for human beings would have been the result if Satan had succeeded in—let me say—winning over Christian justice in order to bring her to Cyprianus. Well—so Satan sets about his task, but he fails. It is Justina's disposition to feel nothing but revulsion for Satan. She flees from him and he retains only a phantom, a shadow image of her.

You see how various motifs which recur in Faust are to be found in Calderón's drama, but here they are bathed in this early Christian struggle. Satan brings the shadow image to Cyprianus. But Cyprianus does not know what to do with a phantom, a shadow image. It has no life. It bears within it only a shadow image of justice. This drama expresses in a most wonderful way what ancient nature wisdom has become now that it masquerades in the guise of modern science, and how, when it approaches social life—that is, when it approaches Justina—it brings no life with it, but only phantom thoughts. Now, with the fifth post-Atlantean period, mankind has entered upon the age of dead thoughts which gives us only phantoms, phantoms of justice, phantoms of love, phantoms of everything—well, not absolutely everything in life, but certainly in theory.

As a result of all this, Cyprianus goes mad. The real Justina is thrown into prison together with her father. She is condemned to death. Cyprianus hears this in the midst of his madness and demands his own death as well. They meet on the scaffold. Above the scene of their death the serpent appears and, riding on the serpent, the demon who had endeavoured to lead Justina to Cyprianus, declaring that they are saved. They can rise up into the heavenly worlds: ‘This noble member of the spirit world is rescued from evil!’

The whole of the Christian struggle of the Middle Ages is contained in this drama. The human being is placed midway between what he is able to experience before birth in the world of spirit and soul, and what he ought to experience after passing through the portal of death. Christ came down to earth because human beings could no longer see what in earlier times they had seen in their middle, rhythmic system which was trained by the breathing exercises of yoga. The middle system was trained, not the head system. These days human beings cannot find the Christ, but they strive to find him. Christ came down. Because they no longer have him in their memory of the time between death and a new birth, human beings must find him here on earth.

Dramas such as the Cyprianus drama of Calderóndescribe the struggle to find Christ. They describe the difficulties human beings face now that they are supposed to return to the spiritual world and experience themselves in harmony with the spiritual world. Cyprianusis still caught in the demonic echoes of the ancient heathen world. He has also not sufficiently overcome the ancient Hebrew element and brought it down to earth. Jahve is still enthroned in the super-sensible worlds, has not descended through the death on the cross, and has not yet become united with the earth. Cyprianus and Justina experience their coming together with the spiritual world as they step through the portal of death—so terrible is the struggle to bring Christ into human nature in the time between birth and death. And there is an awareness that the Middle Ages are not yet mature enough to bring Christ in in this way.

The Spanish drama of Cyprianus shows us the whole vital struggle to bring in the Christ far more vividly than does the theology of the Middle Ages, which strove to remain in abstract concepts and capture the Mystery of Golgotha in abstract terms. In the dramatic and tragic vitality of Calderón there lives the medieval struggle for Christ, that is, the struggle to fill the nature of the human being with the Christ. When we compare Calderón's Cyprianus drama with the later drama about Faust—this is quite characteristic—we find first in Lessing3 Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, 1729-1781. German dramatist, critic and writer on aesthetics; one of the great seminal minds in German literature. the awareness: Human beings must find the Christ during their earthly life because Christ endured the Mystery of Golgotha and united himself with earthly mankind. Not that this lived in any very clear ideas in Lessing, but he did have a definite sense for it. The fragment of his Faust which Lessing succeeded in getting down on paper concludes when the demons—those who were still able to prevent Cyprianus from finding the Christ during earthly life—receive the call: ‘You shall not conquer!’

This set the theme for the later Faust of Goethe. And even in Goethe the manner in which the human being finds Christianity is rather external. Think of Goethe's Faust: In Part One we have the struggle. Then we come to Part Two. In the Classical Walpurgis-Night and in the drama of Helena we are shown first how Christianity is taken up with reference to the Grecian world. Goethe knows that human beings must forge their links with Christ while they are here on the earth. So he must lead his hero to Christianity. But how? I have to say that this is still only a theoretical kind of knowledge—Goethe was too great a poet for us not to notice that this was only a theoretical kind of knowledge. For actually we find that the ascent in the Christian sense only comes in the final act, where it is tacked on to the end of the whole drama. It is certainly all very wonderful, but it does not come out of the inner nature of Faust. Goethe simply took the Catholic dogma. He used the Catholic cultus and simply tacked the fifth act on to the others. He knew that the human being must come to be filled with Christ. Basically the whole mood that lives in the second part of Faust contains this being filled with the Christ. But still Goethe could not find pictures with which to show what should happen. It is really only after Faust's death that the ascent into Christianity is unfolded.

I wanted to mention all this in order to show you how presumptuous it is to speak in a light-hearted way about achieving a consciousness of the Mystery of Golgotha, a consciousness of Christianity. For to achieve a consciousness of Christianity is a task which entails severe struggles of the kind I have mentioned. It behoves mankind today to seek these spiritual forces within the historical evolution of the Middle Ages and modern times. And after the terrible catastrophe we have all been through, human beings really ought to realize how important it is to turn the eye of their souls to these spiritual impulses.

Der menschliche Organismus in seiner Dreigliedrigkeit und die wiederholten Erdenleben

[ 1 ] Wenn wir uns erinnern an das gestern Gesagte, so tritt vor unsere Seele als das Wesentliche hin, daß aus geistig-seelischen Gebieten durch Konzeption und Geburt gewissermaßen heruntersteigt in die physisch-sinnliche Welt einerseits das, was innerlich noch lebendige Geistwelt hat, die sich dann abschattet, abdämpft zu der Gedankenwelt, die der Mensch dann in sich trägt; und andererseits das, was das Seelisch-Geistige durchzieht, und was ich im wesentlichen als einen Furchtzustand charakterisiert habe. Ich habe dann auseinandergesetzt, wie das noch in sich lebendige Geistige sich eben zu Gedankenhaftem metamorphosiert, aber gewissermaßen wie einen lebendigen Rest des vorgeburtlichen Lebens etwas in dieses Erdenleben hereinschickt, was im menschlichen Mitgefühl lebt, so daß wir im menschlichen Mitgefühl tatsächlich etwas haben, das die Lebendigkeit des Vorgeburtlichen in unserer Seele in sich enthält.

[ 2 ] Was dann diese Seele als Furchtgefühl durchzieht vor dem Herabsteigen in die physische Welt, das metamorphosiert sich auf der einen Seite als Selbstgefühl hier im irdischen Leben und dann als Wille. Was also in der menschlichen Seele gedankenhaft lebt, ist gegenüber dem Lebendigen in der Geistwelt vor der Geburt im Grunde genommen ein geistig-seelisch Totes. Wir erleben tatsächlich in unseren Gedanken oder wenigstens in der Kraft, die unser Denken durchzieht, gewissermaßen den Leichnam unseres geistig-seelischen Daseins, wie wir es zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt haben. Aber dieses heutige Erleben der gewissermaßen getöteten Seele während des physischen Erdenlebens war nicht immer in demselben Maße vorhanden. Je weiter wir zurückgehen in der Menschheitsentwickelung, desto mehr spielt das, was ich gestern als Mitgefühl bezeichnet habe Mitgefühl nicht nur mit den Menschen, sondern zum Beispiel auch mit der gesamten Natur -, noch eine gewisse Rolle hier im irdischen Leben. Solche abstrakte Erkenntnis, wie sie heute angestrebt wird, und mit Recht, wenigstens mit einem gewissen relativen Recht, war in der Menschheitsentwickelung nicht immer vorhanden. Eine solche abstrakte innerliche Bewußtheit kam im Grunde genommen im vollsten extremsten Sinne erst im 15. Jahrhundert, also mit dem Beginn des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes herauf. Was da der Mensch erlebt in seinen Gedanken, das ist früher durchzogen gewesen von lebendigem Fühlen. In den alten Erkenntnissen, zum Beispiel der griechischen Welt, gab es diese abstrakten Begriffe, die wir heute haben, überhaupt nicht. Da waren alle Begriffe durchzogen von lebendigem Fühlen. Da empfand der Mensch die Welt, er dachte sie nicht bloß. Dieses Denken der Welt und die Beschränkung des Mitgefühls auf das, was im eigentlichen Sinne schließlich nur soziales Dasein ist, das kam eben erst mit dem Beginn des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes herauf.

[ 3 ] Nun, wenn sich das Mitgefühl im irdischen Leben noch betätigen soll, wie es zum Beispiel im alten Indien so stark vorhanden war für die ganze Natur, wie es angestrebt wurde für alle Wesen der Natur, dann hat der Mensch eben noch ein starkes Erleben in sich von dem, was sich um ihn herum abspielt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. In dem Denken ist dieses Leben erstorben. Im Mitfühlen mit der uns umgebenden Welt ist durchaus ein Nacherleben unserer Wahrnehmungen während der Zeit zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt vorhanden. Es spielte in dem Leben der Menschen in älteren Zeiten, wenn sie in die Natur hinaussahen, dieses Mitgefühl eine große Rolle, und dadurch sahen diese Menschen alles, was in der Natur war, jede Wolke, jeden Baum, jede Pflanze durchgeistigt. Wenn man bloß in Gedanken lebt, dann entgeistigt sich die Natur, weil eben der Gedanke der Leichnam des Geistig-Seelischen ist. Da sieht man die Natur eben als ein totes Gebilde, weil sie sich nur in toten Gedanken spiegeln kann. Daher das Verschwinden aller elementarischen Wesenheiten aus der Anschauung der Natur, als die neuere Zeit heraufrückte.

[ 4 ] Was ist es denn also, was der Mensch trotzdem in sich als eine gewisse Geistigkeit noch fühlt, als eine lebendige Geistigkeit, während er eigentlich in dem Denken doch nur ein totes Geistiges erleben sollte? Wenn man diese Frage beantworten will, dann muß man Rücksicht nehmen auf das, was ich mit Bezug auf die physische Menschheitsorganisation als den dreigliedrigen menschlichen Organismus angegeben habe. Da haben wir den Nerven-Sinnesorganismus, der im wesentlichen im Haupte lokalisiert ist. Wir wollen schematisch uns das einmal vor die Seele rücken [hier beginnt die Zeichnung zu Tafel 10]. Wir haben den rhythmischen Organismus im wesentlichen in den oberen Brustorganen lokalisiert, aber natürlich füllen beide Organismenglieder wiederum den ganzen Organismus aus. Und wir haben den Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus, der im wesentlichen in den Gliedmaßen und in den unteren Teilen des Rumpfes lokalisiert ist.

[ 5 ] Wenn wir auf diese physische Organisation des Menschen Rücksicht nehmen, dann können wir zuerst den Blick lenken auf die Hauptesorganisation, die also hauptsächlich, aber nicht einzig, der Träger des Nerven-Sinneslebens ist. Diese Hauptesorganisation ist im wesentlichen nur zu verstehen, wenn man sie bildhaft erfaßt, und zwar so, daß man weiß, daß sie im wesentlichen die metamorphosische Umbildung ist - nicht dem Stoff, aber der Form nach - des übrigen Menschen, namentlich des Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus, von der vorigen Inkarnation, vom vorigen Erdenleben.

[ 6 ] Der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus vom vorigen Erdenleben, natürlich nicht in seinem Stoff, sondern in seiner Form, wird Kopforganisation in diesem, also dem folgenden Erdenleben. So daß man sagen kann: Hier im Haupte haben wir gewissermaßen ein Gehäuse zu sehen, das in seinem Bau sich herangebildet hat durch eine Umgestaltung des Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus von der vorigen Inkarnation, und in diesem Haupte wohnen hauptsächlich die abstrakten Gedanken, also diejenigen Gedanken, die der Leichnam des seelisch-geistigen Lebens vor der Geburt sind (siehe Zeichnung, rot).

[ 7 ] Wir tragen also in unserem Haupte gewissermaßen die lebendigen Erinnerungen an unser voriges Erdenleben in uns und das macht, daß wir uns in diesem Erdenleben als ein Ich fühlen, als ein lebendiges Ich, denn dieses lebendige Ich ist gar nicht innerlich vorhanden. Innerlich sind die toten Gedanken da. Aber diese toten Gedanken wohnen in einem Gehäuse, das nur seiner Bildhaftigkeit nach zu verstehen ist, und in seiner Bildhaftigkeit die metamorphosische Umbildung des Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus vom vorigen Erdenleben ist.

[ 8 ] Dasjenige, was nun schon belebter herüberkommt aus dem geistig-seelischen Leben, wenn die Seele heruntersteigt ins physische Erdenleben, das schlägt sogleich seinen Wohnsitz nicht im Kopfe, sondern im rhythmischen Organismus auf (rot). In diesem rhythmischen Organismus haben wir alles das in uns, was hereinspielt aus unserer Umgebung, die wir um uns gehabt haben zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt. Und während in seinem Kopfe der Mensch etwas hat, das nur ein Bild seines vorigen Erdenlebens ist mit dem toten Gedankenorganismus, hat er in seiner rhythmischen, in seiner oberen Brustorganisation etwas viel Lebendigeres. Da spielt der Nachklang alles dessen hinein, was die Seele erlebt hat, als sie sich frei im GeistigSeelischen zwischen dem Tode und der Geburt bewegte. Indem wir atmen, indem wir unsere Blutzirkulation haben, vibriert in dieses Atmen, in diese Blutzirkulation dasjenige hinein, was Kräfte waren zwischen dem Tode und der Geburt. Und was wir als unsere geistig-seelische Wesenheit für diese irdische Inkarnation haben, das haben wir weder im Kopfe noch haben wir es in der Brust, sondern das haben wir, so sonderbar das für den heutigen Menschen klingt, in der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganisation. Unser gegenwärtiges ErdenIch haben wir in der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganisation (grün).

[ 10 ] Die toten Gedanken, die müssen Sie sich ja doch lebend denken; diese toten Gedanken leben — wenn ich mich jetzt bildlich ausdrücke, ist es natürlich nur approximativ gemeint - in den Windungen des Gehirns drinnen, und das Gehirn wiederum ist eine Umbildung des Organismus der vorigen Inkarnation. Dieses Leben, dieses Hausen der toten Gedanken im Kopfe, das nimmt dann der Eingeweihte wahr als eine Wirklichkeitserinnerung an die vorige Inkarnation. Es ist wirklich gerade so mit dieser Erinnerung an die vorige Inkarnation, wie wenn Sie in einem finsteren Zimmer sind und haben auf Ihrem Kleiderrechen Ihre verschiedenen Kleider aufgehängt, und Sie können durch das Befühlen wählen, wo Sie, sagen wir zum Beispiel Ihren Samtrock haben, und dabei geht Ihnen nun auf, wann Sie diesen Samtrock gekauft haben. So ist es, wenn da die toten Gedanken überall anstoßen. Erfühlen dasjenige, was in der Hauptesorganisation ist, das ist alles Erinnerung an das vorige Erdenleben.

[ 11 ] Was im Brustorganismus erlebt wird, das ist Erinnerung an das Leben zwischen dem Tode und neuer Geburt, und dasjenige, was im Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechsel erlebt wird, das ist jetziges Erdenleben. Nur dadurch, daß der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus heraufwirkt in die Gedanken hinein, hat der Mensch in seinen Gedanken das Erlebnis des Ich. Aber das ist ein trügerisches Erlebnis. In den Gedanken selbst ist das Ich gar nicht enthalten. Es ist ebensowenig in den Gedanken enthalten, wie Sie hinter dem Spiegel stehen, wenn Sie sich in ihm spiegeln. Das Ich ist gar nicht drinnen in dem Gedankenleben. Da ist dadurch, daß sich das Gedankenleben nach dem Kopfe formt, die Erinnerung an das vorige Erdenleben enthalten. Also im Kopfe haben Sie eigentlich Ihren Menschen aus dem vorigen Erdenleben. In Ihrer Brust haben Sie den Menschen, wie er lebte zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, und in Ihrem Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus und namentlich in Ihren Finger- und Zehenspitzen haben Sie im Grunde genommen den Menschen, wie er hier auf der Erde ist. Und nur weil Sie im Gehirn miterleben Ihre Finger- und Zehenspitzen haben Sie auch durch Gedanken ein Bewußtsein von diesem Ich in Ihrem Erdenleben. So grotesk sind die Dinge in der Wirklichkeit gegenüber manchem, was sich der Mensch gewöhnlich heute vorstellt.

[ 12 ] So mit dem Kopfe vorzustellen, wie das heute geschieht, das trat eigentlich regulär erst ein mit dem Beginn des fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraumes, mit dem 15. Jahrhundert. Aber alle Dinge gehen in gewissem Sinne ahrimanisch voran, sie werden vorausgenommen. Das Luziferische ist das, was später eintritt, als es in der Entwickelung berechtigt ist; das Ahrimanische tritt früher ein. Und so haben wir die Möglichkeit, auf eine Erscheinung in der Geschichte hinzuweisen, wo in ganz entschiedener Weise etwas zu früh eintritt, was eigentlich regulär erst im 15. Jahrhundert hätte eintreten sollen. Da ist es dann auch eingetreten, aber es wurde eben schon vorausgenommen zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha. Und da können wir darauf hinweisen, wie die alttestamentlichen Vorstellungen, die ich Ihnen gestern etwas charakterisiert habe, durch den Zeitgenossen des Christus-Jesus, durch Philo von Alexandrien, ganz zu Allegorien gemacht worden sind.

[ 13 ] Philo von Alexandrien faßt das ganze Alte Testament allegorisch auf, das heißt, er will das ganze Alte Testament, das in Form von Erlebnissen dargestellt wird, zu Gedankenbildern machen. Das ist sehr geistreich, und indem es zum erstenmal in der Menschheitsentwickelung auftritt, kann man auch von dieser Geistreichigkeit sprechen. Heute ist es weniger geistreich, wenn zum Beispiel Theosophen den «Hamlet» so erklären, daß die eine Figur Manas, die andere Buddhi ist und so weiter, wenn also die Sache ganz ins Allegorische gezerrt wird. Das ist natürlich ein Unsinn. Aber Philo von Alexandrien verwandelte gewissermaßen das ganze Testament in Gedankenbilder, in Allegorien. Diese Allegorien sind eben nichts anderes als die innere Offenbarung des ertöteten Seelenlebens, des gestorbenen und in der Gedankenkraft als Leichnam vorliegenden Seelenlebens. Die alttestamentliche Anschauung sah in ihrer Art noch zurück zu dem Leben vor der Geburt oder vor der Empfängnis, und aus dieser Anschauung stellte sie das Alte Testament her.

[ 14 ] Als man nicht mehr zurückschauen konnte, und Philo von Alexandrien konnte nicht zurückschauen, da wurde das alles zu den toten Gedankenbildern. Und so haben wir in der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit diese zwei bedeutsamen Erscheinungen nebeneinander: die alttestamentliche Entwickelung gipfelte in Philo von Alexandrien zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha. Das ganze Alte Testament macht Philo von Alexandrien zu einer Welt von strohernen Allegorien. Und gleichzeitig damit erscheint in dem Mysterium von Golgatha die Offenbarung, daß nicht das tote Erlebnis im Menschen zum Übersinnlichen hinführen kann, sondern der ganze Mensch, der durch das Mysterium von Golgatha geht, mit dem göttlichen Wesen in sich.

[ 15 ] Es sind das die zwei großen polarischen Gegensätze: Die abstrakte Welt, die in ahrimanischer Art vorausgenommen ist in Philo, und die Welt, die mit dem Christentum in die Menschheitsentwickelung einziehen soll. Man möchte sagen, von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus wird die ganze Welt zu einer Frage. Der Abstraktling - und Philo von Alexandrien ist vielleicht der genialste Abstraktling gewesen, weil er die spätere Abstraktheit ahrimaniisch vorausgenommen hat -, er will die Antwort für das Weltengeheimnis finden, indem er irgendwelche Gedanken faßt, die das Weltenrätsel lösen sollen. Dagegen ist das Mysterium von Golgatha der umfassende lebendige Protest. Niemals lösen Gedanken das Weltenrätsel, sondern diese Lösung bleibt lebendig. Der Mensch selber in seiner Totalität ist die Lösung des Weltenrätsels. Da erscheinen die Sonnen, die Sterne, die Wolken, die Flüsse, die Berge, die einzelnen Wesenheiten der verschiedenen Naturreiche, indem sie von außen sich offenbaren, als eine große Frage. Und der Mensch steht da, und in seiner ganzen Wesenheit ist er die Antwort.

[ 16 ] Das ist auch ein Gesichtspunkt, von dem aus das Mysterium von Golgatha betrachtet werden kann. Man sucht nicht Gedanken in ihrer Totheit dem Weltenrätsel entgegenzustellen; man stellt dem ganzen Menschen entgegen das, was aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus erlebt werden kann.

[ 17 ] Nur ganz langsam und allmählich konnte die Menschheit den Weg finden, um das zu verstehen. Und heute ist er ja noch nicht gefunden. Anthroposophie will diesen Weg eröffnen. Aber seitdem die Abstraktheit Platz gegriffen hat, hat man gewissermaßen sogar das Bewußtsein verloren, daß dieser Weg gesucht werden müsse. Bis dahin war ein Ringen darnach vorhanden, und das Ringen zeigt sich gerade am deutlichsten noch an dieser Wende vom vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum hinein. Indem sich das Christentum als eine äußere Erscheinung ausbreitet, ringen gerade die besten Geister darnach, dieses Christentum innerlich zu verstehen. Es ist im Grunde ein fortwährendes Ringen um den Sinn des Christentums, das bei den besten Geistern sich abspielt. Man wollte gewissermaßen lebendig das Weltenrätsel vor den Menschen hinstellen, das heißt den Menschen als solchen wirklich verstehen. Man hatte eben die beiden Strömungen von alten Zeiten her übernommen: Auf der einen Seite die heidnische Strömung, die im Grunde genommen eine Naturweisheit war, die in allen Naturwesen geistig-elementarische Wesenheiten, dämonische Wesenheiten sah, eben jene dämonischen Wesenheiten, von denen das Evangelium erzählt, indem es darauf hinweist, daß die Dämonen sich aufbäumten, als der Christus unter die Menschen trat, weil sie jetzt wußten, ihre Herrschaft ist dahin. Die Menschen haben den Christus nicht erkannt. Die Dämonen haben ihn erkannt. Sie wußten, jetzt wird er Besitz ergreifen von den Herzen, von den Seelen der Menschen; sie müssen sich zurückziehen. Aber sie spielten noch lange eine Rolle in den Gemütern und im Erkenntnisstreben der Menschen. Das heidnische Bewußtsein, das die dämonisch-elementarisch-geistige Natur in allen Naturwesen auf alte Art suchte, das spielte noch lange eine Rolle. Es war eben ein Ringen um jene Erkenntnisart, die überall in dem Irdischen nun auch dasjenige suchen sollte, was durch das Mysterium von Golgatha sich mit dem Erdenleben als die Substanz des Christus selber vereinigt hatte.

[ 18 ] Das war die eine Strömung, die heidnische Strömung, die eine Natur-Sophia war, die überall in der Natur das Geistige sah und daher auch auf den Menschen zurücksehen konnte, den sie zwar als ein Naturwesen ansah, aber dennoch als ein Geistiges, weil sie eben in allen Naturwesen auch ein Geistiges sah. Am reinsten, schönsten kommt das heraus in Griechenland und insbesondere wiederum in der griechischen Kunst, wo wir sehen, wie das Geistige als Schicksal das Menschenleben durchwebt, so wie die Naturgesetze die Naturerscheinungen durchweben. Und wenn wir auch manchmal schaudernd stehen vor dem, was sich in der griechischen Tragödie darbietet, so haben wir auf der andern Seite doch das Gefühl: Der Grieche empfand noch nicht bloß die abstrakten Naturgesetze, wie wir heute, sondern er empfand auch das Wirken von göttlich-geistiger Wesenheit in allen Pflanzen, in allen Steinen, in allen Tieren, und daher auch in dem Menschen selber, in dem sich die starre Notwendigkeit des Naturgesetzes zu dem Schicksal formte, wie es zum Beispiel im Ödipus-Drama zu finden ist. Wir haben da die innige Verwandtschaft des natürlich-geistigen Daseins mit dem menschlich-geistigen Dasein. Daher waltet in diesen Dramen noch nicht die Freiheit und auch noch nicht das menschliche Gewissen. Es waltet eine innere Notwendigkeit, ein Schicksalsmäßiges in dem Menschen, in ähnlicher Art, wie draußen die Naturgesetzmäßigkeit in der Natur waltet.

[ 19 ] Das ist die eine Strömung, die heraufkommt in die neuere Zeit. Die andere ist die alttestamentlich-jüdische Strömung. Sie hat keine Naturweisheit. Sie hat in bezug auf die Natur nur das Anschauen des sinnlich-physischen Daseins. Dafür ist aber diese alttestamentliche Anschauung hinaufgerichtet zu den Urquellen des Moralischen, die zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt liegen, zu jenen Urquellen, die aber jetzt nicht hinschauen auf das Naturhafte im Menschen. Für das Alte Testament gibt es keine Naturwissenschaft, sondern nur das Einhalten göttlicher Gebote. Die Dinge geschehen, im Sinne des Alten Testaments, nicht nach Naturgesetzen. Die Dinge geschehen, weil Jahve es will. Und so sehen wir, daß es aus dem Alten Testament heraus bildlos ertönt, in einem gewissen Sinne abstrakt, aber hinter diesen Abstraktionen steht bis auf Philo von Alexandrien, der nun alles zu Allegorien macht, der Herrscher Jahve, der diese Abstraktionen mit einer ins Übersinnliche hinauf idealisierten, allgemeinen Menschennatur durchdringt, der wie ein menschlicher Herrscher alles das durchdringt, was als Gebote von ihm herabklingt auf die Erde. Es ist in dieser alttestamentlichen Anschauung ein bloßes Hinschauen auf die moralische Welt, geradezu ein Sich-Scheuen davor, die Welt in ihrer äußeren Sinnlichkeit anzuschauen. Während die Heiden darauf bedacht waren, überall die göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten zu sehen, ist der Judengott bloß der Eine. Der Jude ist Monotheist. Sein Gott, sein Jahve, ist der Eine, weil er sich nur auf das beziehen kann, was im Menschen als Einheitliches ist: Du sollst allein an einen Gott glauben; und diesen Gott sollst du nicht ausdrücken durch etwas Irdisches, nicht durch ein plastisches Bild, nicht einmal durch das Wort, das nur der Eingeweihte bei besonders festlichen Gelegenheiten aussprechen darf: Du sollst den Namen deines Gottes nicht unheilig aussprechen.

[ 20 ] Und so ist überall der Hinweis auf das Unanschauliche, auf das, was nicht durch die Natur zum Ausdrucke kommen kann, was nur gedacht werden kann. Aber im Alten Testament denkt man hinter diesen Gedanken noch die lebendige Jahve-Natur. Diese verschwindet in den Allegorien des Philo von Alexandrien.

[ 21 ] Nun handelt es sich darum, in dem christlichen Ringen der ersten Jahrhunderte und bis ins 15., 16., 17. Jahrhundert herein den Zusammenklang zu finden zwischen dem, was man sehen kann als das Geistige in der äußeren Natur und dem, was als das Göttliche erlebt wird, wenn wir auf die eigene Moralität, auf das Seelische im Menschen schauen. Wenn man diese Sache theoretisch nimmt, so sieht sie einfach aus. In Wirklichkeit war das Suchen nach dem Zusammenklang zwischen dem Anschauen des Geistigen in der äußeren Natur und dem Hinauflenken der Seele zu dem Geistigen, aus dem der Christus Jesus heruntergestiegen ist, ein ungeheures Ringen. Und indem das Christentum von Asien herüberzieht und die griechische, die römische Welt ergreift, sehen wir in den späteren Jahrhunderten des Mittelalters dieses Ringen noch am stärksten auf jenem Boden Europas, der sich noch viel Ursprünglichkeit erhalten hatte. In Griechenland selbst war noch das alte heidnische Element, die Anschauung des Geistigen in allen Naturdingen so groß, daß das Christentum zwar durch das Griechentum durchgegangen ist, sogar viele Sprachformen durch das Griechische erhalten hat, aber nicht innerhalb des Griechischen Wurzel fassen konnte. Nur die Gnosis, die geistige Anschauung vom Christentum, hat in Griechenland noch Wurzel fassen können.

[ 22 ] Dann hatte das Christentum das prosaischste Element in der Weltentwickelung zu passieren: das Römertum, das ja in seiner Abstraktheit wiederum auch nur Abstraktes fassen konnte, gleichfalls das Spätere ahrimanisch vorausnehmend, das, was im Christentum lebendig ist. Aber ein wirklich lebendiges Ringen finden wir dann in Spanien, wo tatsächlich die Frage, aber nicht theoretisch, sondern als intensive Lebensfrage auftritt: Wie kann der Mensch, ohne daß er die Anschauung des Geistigen in den Naturdingen und Naturvorgängen verliert, den ganzen Menschen finden, der ihm durch den Christus Jesus vor die Augen der Seele gestellt ist? Wie kann der Mensch sich durchchristen? - Am lebendigsten tauchte sie gerade in Spanien auf, und wir sehen in Calderón einen Dichter, der dieses Ringen ganz besonders intensiv darzustellen wußte. In Calderón lebt, wenn ich so sagen darf, dramatisch dieses Ringen nach dem Durchchristerwerden des Menschen.

[ 23 ] Da sehen wir auf das charakteristischste Drama des Calderón hin, auf den «Cyprianus», der eine Art wundertätiger Magier ist, also ein Mensch zunächst, der in den Naturdingen und Naturvorgängen lebt, indem er jene Geistigkeit durchforschen will. Wenn Sie das Bild eines solchen Menschen nach seiner späteren Metamorphose, nach der Faust-Metamorphose nehmen, so haben Sie nicht die volle Lebendigkeit, mit der etwa bei Calderón Cyprianus auftritt. Denn dieses Drinnenstehen in dem Geiste der Natur bei Cyprianus hat noch volles Leben. Da ist noch eine volle Selbstverständlichkeit, während bei Faust alles schon in Zweifel gehüllt ist. Während Faust von Anfang an nicht mehr recht an das Finden des Geistigen in der Natur glaubt, ist der Cyprianus des Calderón durchaus noch eine mittelalterliche Figur. So, wie der heutige Physiker oder Chemiker in seinem Laboratorium von seinen Apparaten umgeben ist, der Physiker von den Geißlerschen Röhren und andern Apparaten, der Chemiker von seinen Retorten und von seinen Wärmeöfen und dergleichen, so ist Cyprianus für seine Seelenverfassung überall von dem umgeben, was als das Geistige aufleuchtet und aufquillt aus den Naturvorgängen und Naturwesenheiten.

[ 24 ] Da tritt- und das ist charakteristisch - in das Leben dieses Cyprianus Justina ein. Hier haben wir den Hinweis auf etwas, was im Drama ganz menschlich dargestellt wird als ein weibliches Wesen, was wir aber doch, wenn wir es bloß als ein weibliches Wesen auffassen, eben nicht voll erfassen. Denn diese mittelalterlichen Dichter werden nicht richtig verstanden, wenn man so, wie das ihre neueren Erklärer tun, immer sagt: Da muß nur das ganz derb materiell Konkrete aufgefaßt werden; wir dürfen zum Beispiel bei der Beatrice des Dante an nichts anderes denken als an ein weiches, weibliches Wesen. - Oder aber die Erklärer gehen an dem Richtigen auch vorbei, indem sie wiederum alles allegorisieren, in eine geistige Sphäre hinaufheben. So weit voneinander, wie für die Köpfe der modernen Erklärer, waren eben damals die geistigen Bilder und die wirklichen Erdenwesen noch nicht. Und so dürfen wir, indem da in dem Calderón-Drarma Justina auftritt, wiederum an die die Welt durchziehende Gerechtigkeit denken, die eben nicht so etwas Abstraktes war wie das, was heute auch die Juristen nicht mehr haben, sondern was in ihrer Bibliothek steht und was sie herausnehmen in Form von einzelnen Bänden. Es wurde eben die Jurisprudenz auch als etwas Lebendiges empfunden.

[ 25 ] So tritt Justina an Cyprianus heran. Und nun wird es natürlich wiederum schwierig für den modernen wissenschaftlichen Interpreten, der jetzt die Hymne verstehen soll, die Cyprianus auf Justina singt. Ja, die modernen Advokaten tun das nicht auf ihre Jurisprudenz, aber so jemand wie der Cyprianus empfand eben auch die Gerechtigkeit, die die Welt durchwebt und durchlebt als etwas, dem er Hymnen singen konnte. Es ist eben das geistige Leben anders geworden, das muß immer wieder betont werden. Aber Cyprianus ist zu gleicher Zeit auch Magier, der es mit den Geistwesen der Natur zu tun hat, jener Welt der Dämonen, unter der auch das mittelalterliche Wesen Satanas ist. Nun fühlt sich Cyprianus nicht fähig, wirklich an Justina heranzukommen. Da wendet er sich an den Satan, den Anführer dieser Naturdämonen. Der soll ihm Justina verschaffen.

[ 26 ] Da haben Sie die ganze tiefe Tragik des christlichen Konfliktes; nämlich das, was an Cyprianus herantritt in Justina, das ist die Gerechtigkeit, die der christlichen Entwickelung angemessen ist. Sie soll an Cyprianus, den noch halb heidnischen Naturgelehrten, herangebracht werden. Das ist die Tragik: Er kann aus der Naturnotwendigkeit, die etwas Starres hat, nicht die christliche Gerechtigkeit finden. Aber er kann sich auch nur an den Anführer der Dämonen, an den Satanas wenden, daß der ihm Justina verschaffe.

[ 27 ] Satanas macht sich heran an die Aufgabe. Die Menschen können schwer begreifen, weil natürlich Satanas ein sehr gescheites Wesen ist, daß er immer wieder an Aufgaben geht, an denen er schon so und so oft gescheitert ist. Aber das ist eben eine Tatsache. Wir mögen uns noch so gescheit dünken, wir können in dieser Weise nicht ein so gescheites Wesen wie Satanas kritisieren. Man müßte sich sagen, es muß doch etwas geben, was ein so gescheites Wesen immer wieder dazu bringt, das Glück aufs Neue zu versuchen, um die Menschen auf diese Weise zu verderben. Denn natürlich würde Verderbnis der Menschen eingetreten sein, wenn es Satan gelungen wäre, die christliche Gerechtigkeit — wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf - herumzukriegen, um sie an Cyprianus heranzubringen. Also Satan macht sich daran, aber es gelingt ihm nicht. Die ganze Gesinnung Justinas widerstrebt dem Satanas; und sie entflieht dem Satan, und er behält ein Phantom von ihr zurück, ein Schattenbild.

[ 28 ] Sie sehen, wie bei Calderón manches Motiv, das Sie dann im «Faust» wiederfinden, auftaucht, aber alles eben gewissermaßen in dieses urchristliche Ringen getaucht. Der Satan behält ein Schattenbild zurück, das bringt er dem Cyprianus. Cyprianus kann natürlich mit dem Phantom, mit dem Schattenbild nichts Rechtes anfangen. Es hat nicht Leben. Es hat nur ein Schattenbild der Gerechtigkeit in sich. Oh, es ist wunderbar ausgedrückt, wie das, was aus der alten Naturweisheit geworden ist und als neuere Naturwissenschaft auftritt, wenn es an so etwas herankommen will wie an das soziale Leben, an die Justina, wie es nicht das wirkliche Lebendige liefert, sondern nur Gedankenphantome. Wie es jetzt, weil die Menschheit mit dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum zu der toten Gedankenwelt vorgedrungen ist, eben nur Phantome liefert, die Phantome der Gerechtigkeit, die Phantome der Liebe, die Phantome von allem - ich will nicht sagen im Leben, aber in der Theorie.

[ 29 ] Und über alledem wird Cyprianus verrückt. Justina, die wirkliche Justina, kommt mit ihrem Vater in die Gefangenschaft. Sie wird zum Tode verurteilt. Cyprianus hört das in seinem Wahnsinne und fordert für sich auch den Tod. Und eben auf dem Schafott finden sie sich. Über ihrem Sterben erscheint die Schlange und auf ihr reitend der Dämon, der Justina dem Cyprianus zuführen wollte, und erklärt, sie seien erlöst. Sie können aufsteigen in die himmlischen Welten: «Gerettet ist das edle Glied der Geisterwelt vom Bösen!»

[ 30 ] Das ganze christliche Ringen des Mittelalters liegt darinnen. Der Mensch ist eingeschaltet zwischen dem, was er erleben kann vor der Geburt in der geistig-seelischen Welt und was er erleben soll, nachdem er durch die Pforte des Todes gegangen ist. Der Christus ist heruntergestiegen auf die Erde, weil nicht mehr gesehen werden konnte, was in früheren Zeiten noch im mittleren Menschen, im rhythmischen Menschen, gesehen worden ist, wovon ein Nachklang gesehen worden ist, als gerade dieser mittlere Mensch durch die Atmungsübungen des Jogasystems ausgebildet wurde, die also nicht eine Kopfausbildung waren, sondern eine Ausbildung des rhythmischen Menschen. Der Mensch kann den Christus in dieser Zeit nicht finden. Er strebt danach, ihn zu finden. Der Christus ist heruntergestiegen. Der Mensch soll, weil er ihn nicht mehr in der Erinnerung hat aus der Zeit, die er zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt durchlebt hat, er soll ihn hier finden.

[ 31 ] Solche Dramen wie das Cyprianus-Drama des Calderón stellen das Ringen nach diesem Finden dar, und es stellt eben die Schwierigkeiten dar, die der Mensch hat, der nun wirklich in die geistige Welt wiederum zurückkommen soll, der den Zusammenklang mit der geistigen Welt erleben soll. Cyprianus ist noch befangen von dem, was an Dämonenhaftem aus der alten heidnischen Welt nachklingt. Er hat aber auch das Jüdisch-Althebräische noch nicht so weit überwunden, daß es ihm ein Gegenwärtig-Irdisches geworden ist. Jahve thront für ihn noch in überirdischen Welten, ist nicht durch den Kreuzestod herabgestiegen und hat sich noch nicht mit der Erde vereinigt. Cyprianus und Justina erleben ihr Zusammengehen mit der geistigen Welt, indem sie sterben und durch die Pforte des Todes gehen. So furchtbar ist dieses Ringen, um den Christus hereinzubekommen in die menschliche Natur in der Zeit zwischen Geburt und Tod. Und ein Bewußtsein davon ist vorhanden, daß das Mittelalter eben noch nicht reif ist, um ihn in dieser Weise hereinzubekommen.

[ 32 ] In dem spanischen Cyprianus-Drama tritt uns das ganze Lebendige dieses Christus-Ringens viel deutlicher entgegen als in der Theologie dieses Mittelalters, die sich ja an abstrakte Begriffe halten wollte, und die in ihre abstrakten Begriffe das Mysterium von Golgatha einfangen wollte. In der dramatisch-tragischen Lebendigkeit des Calderón lebt dieses mittelalterliche Ringen nach dem Christus, das heißt, nach dem Durchchristetwerden der menschlichen Natur. Und wenn man dieses Calderón-Drama von dem Cyprianus mit dem späteren Faust-Drama vergleicht - es ist das charakteristisch genug -, dann sieht man, da tritt zuerst bei Lessing das Bewußtsein auf: Der Mensch muß im irdischen Leben den Christus finden können, denn der Christus ist durch das Mysterium von Golgatha gegangen und hat sich mit der irdischen Menschheit vereinigt. Nicht, daß das in klaren Ideen bei Lessing gelebt hat, aber ein deutliches Gefühl davon hat in Lessing gelebt. Und als er seinen «Faust» schreiben wollte - er hat ja nur ein kurzes Stückchen davon zu Papier bringen können -, endete er damit, daß den Dämonen, also denen, die noch den Cyprianus abhalten konnten, während des irdischen Lebens den Christus zu finden, zugerufen wird: «Ihr sollt nicht siegen!».

[ 33 ] Damit war zu gleicher Zeit das Thema für den späteren Goetheschen «Faust» gegeben; und im Grunde genommen ist es auch noch beim Goetheschen Faust äußerlich, wie der Mensch sich zum Christentum findet. Nehmen Sie den ganzen Goetheschen «Faust», nehmen Sie den ersten Teil: Da ist das Ringen. Nehmen Sie den zweiten Teil: Da soll zunächst durch die klassische Walpurgisnacht, durch das Helena-Drama, das Aufnehmen des Christentums erfahren werden an der griechischen Welt. Dann aber weiß Goethe: Der Mensch muß hier im Erdenleben den Anschluß finden an Christus. Er muß daher seinen dramatischen Helden hinführen zu dem Christentum. Allein, wie führt er ihn hin? Es ist ja nur ein theoretisches Bewußtsein, möchte ich sagen. Goethe war ein zu großer Dichter, als daß man das nicht bemerkt, daß es nur ein theoretisches Bewußtsein war. Denn zuletzt ist schließlich doch nur im letzten Akt das Aufsteigen im christlichen Sinne an das ganze Faust-Drama angeleimt. Es ist gewiß alles großartig, aber es ist nicht aus der inneren Natur des Faust herausgeholt, sondern Goethe hat das katholische Dogma genommen. Goethe hat den katholischen Kultus genommen und hat den fünften Akt an die andern angeleimt. Er wußte, es muß der Mensch zu der Durchchristetheit geführt werden. Im Grunde genommen ist es nur die ganze Gesinnung, die im zweiten Teile des «Faust» lebt, die dieses Durchdringen mit dem Christus darstellt. Denn bildhaft konnte es auch Goethe noch nicht geben, und eigentlich ist es auch erst nach dem Tode des Faust, wo der ganze christliche Aufstieg entfaltet wird.

[ 34 ] Ich wollte das alles nur anführen, um Ihnen zu zeigen, wie vermessen es eigentlich ist, wenn man leichten Herzens von der Erringung des Bewußtseins vom Mysterium von Golgatha, des christlichen Bewußtseins, spricht. Denn diese Erringung des christlichen Bewußtseins stellt eben durchaus eine Aufgabe dar, um die so schwer gekämpft worden ist, wie wir es an solchen Beispielen sehen können, wie ich sie angeführt habe. Es ist heute an der Menschheit, diese geistigen Kräfte innerhalb der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der mittleren und der neueren Zeit zu suchen. Und nach der großen Katastrophe, die wir durchgemacht haben, sollte schon die Menschheit ein Bewußtsein davon bekommen, daß es darauf ankommt, diese geistigen Impulse wirklich ins Seelenauge zu fassen.

[ 35 ] Nun, davon wollen wir dann morgen weiterreden. Wir wollen uns wiederum um 8 Uhr hier zu der Fortsetzung dieser Betrachtung einfinden.

The human organism in its threefold nature and repeated earthly lives

[ 1 ] If we recall what was said yesterday, what emerges before our soul as the essential fact is that, on the one hand, that which is still alive in the spiritual world descends, through conception and birth, into the physical-sensory world, where it is then shadowed and dampened to form the world of thoughts that human beings then carry within themselves; and on the other hand, that which pervades the soul-spiritual, and which I have essentially characterized as a state of fear. I then discussed how the spiritual, which is still alive within us, metamorphoses into thought, but in a sense sends something into this earthly life as a living remnant of pre-birth life, something that lives in human compassion, so that in human compassion we actually have something that contains the liveliness of the pre-birth in our soul.

[ 2 ] What then pervades this soul as a feeling of fear before descending into the physical world is transformed, on the one hand, into a sense of self here in earthly life and then into will. What lives as thought in the human soul is, in relation to the living in the spiritual world before birth, basically spiritually and soul-wise dead. In our thoughts, or at least in the power that pervades our thinking, we actually experience, in a sense, the corpse of our spiritual-soul existence as we have it between death and a new birth. But this present-day experience of the soul being, in a sense, killed during physical life on earth has not always been present to the same degree. The further back we go in human evolution, the more what I yesterday called compassion—compassion not only for human beings but also, for example, for the whole of nature—plays a certain role here in earthly life. Such abstract knowledge, as is sought today, and rightly so, at least with a certain relative right, was not always present in human evolution. Such abstract inner awareness only emerged in the fullest, most extreme sense in the 15th century, that is, with the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. What human beings experience in their thoughts was previously permeated by living feeling. In the ancient knowledge, for example in the Greek world, the abstract concepts we have today did not exist at all. All concepts were permeated by living feeling. Man perceived the world; he did not merely think it. This thinking about the world and the restriction of compassion to what is, in the strict sense, only social existence, only came about with the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch.

[ 3 ] Now, if compassion is still to be active in earthly life, as it was so strongly present in ancient India, for example, for the whole of nature, as it was strived for for all beings in nature, then human beings still have a strong experience within themselves of what is happening around them between death and a new birth. In thinking, this life has died. In our empathy with the world around us, there is definitely a reliving of our perceptions during the time between death and a new birth. In the lives of people in earlier times, when they looked out into nature, this compassion played a major role, and as a result, these people saw everything in nature, every cloud, every tree, every plant, as imbued with spirit. When one lives only in thoughts, nature becomes devoid of spirit, because thought is the corpse of the spiritual-soul. One sees nature as a dead structure, because it can only be reflected in dead thoughts. Hence the disappearance of all elemental beings from the view of nature as the newer times approached.

[ 4 ] What is it, then, that humans still feel within themselves as a certain spirituality, as a living spirituality, when in their thinking they should actually only experience a dead spirituality? If we want to answer this question, we must take into account what I have stated with reference to the physical organization of the human being as the threefold human organism. There we have the nerve-sense organism, which is essentially located in the head. Let us schematically bring this before our mind [here the drawing for Plate 10 begins]. We have the rhythmic organism located mainly in the upper chest organs, but of course both parts of the organism fill the entire organism. And we have the limb metabolism organism, which is located mainly in the limbs and in the lower parts of the trunk.

[ 5 ] If we take this physical organization of the human being into account, we can first direct our attention to the head organization, which is mainly, but not solely, the carrier of the nervous and sensory life. This head organization can essentially only be understood if it is grasped pictorially, in such a way that one knows that it is essentially the metamorphic transformation—not in substance, but in form—of the rest of the human being, namely the limb-metabolism organism, from the previous incarnation, from the previous earthly life.

[ 6 ] The limb-metabolism organism from the previous earthly life, naturally not in its substance but in its form, becomes the head organization in this, i.e., the following earthly life. So that one can say: Here in the head we have, as it were, a casing that has been formed in its structure through a transformation of the limb-metabolism organism from the previous incarnation, and in this head dwell mainly the abstract thoughts, that is, those thoughts that are the corpse of the soul-spiritual life before birth (see drawing, red).

[ 7 ] We therefore carry within our head, as it were, the living memories of our previous earthly life, and this is what makes us feel ourselves to be an I in this earthly life, a living I, for this living I is not present within us at all. Within us are the dead thoughts. But these dead thoughts dwell in a shell that can only be understood in terms of its imagery, and in its imagery is the metamorphic transformation of the limb-metabolism organism from the previous earthly life.

[ 8 ] That which now comes across as more animated from spiritual-soul life, when the soul descends into physical earthly life, does not immediately take up residence in the head, but in the rhythmic organism (red). In this rhythmic organism, we have everything within us that has come in from our surroundings, which we had around us between death and a new birth. And while the human being has something in their head that is only an image of their previous earthly life with the dead thought organism, they have something much more alive in their rhythmic, upper chest organization. There, the echo of everything the soul experienced when it moved freely in the spiritual-soul realm between death and birth plays into it. As we breathe, as we have our blood circulation, what were forces between death and birth vibrate into this breathing, into this blood circulation. And what we have as our spiritual-soul being for this earthly incarnation, we have neither in our head nor in our chest, but, strange as it may sound to people today, in the metabolism of our limbs. We have our present earthly I in the metabolism of our limbs (green).

[ 10 ] You must think of dead thoughts as living; these dead thoughts live—if I express myself figuratively, of course, it is only meant approximately—in the convolutions of the brain, and the brain in turn is a transformation of the organism of the previous incarnation. This life, this dwelling of dead thoughts in the head, is then perceived by the initiate as a memory of reality from the previous incarnation. It is really just like this memory of the previous incarnation, as when you are in a dark room and have hung your various clothes on your clothes rack, and you can choose by touch where, say, your velvet coat is, and then you remember when you bought this velvet coat. So it is when the dead thoughts bump into each other everywhere. Feel what is in the head organization; that is all memory of the previous earthly life.

[ 11 ] What is experienced in the chest organism is memory of life between death and rebirth, and what is experienced in the limb metabolism is the present earthly life. Only through the limb metabolism organism working up into the thoughts does the human being have the experience of the I in his thoughts. But this is a deceptive experience. The I is not contained in the thoughts themselves. It is just as little contained in the thoughts as you are standing behind the mirror when you see your reflection in it. The I is not at all contained in the life of the thoughts. Because the life of the thoughts is formed according to the head, it contains the memory of the previous earthly life. So in the head you actually have your human being from the previous earthly life. In your chest you have the human being as he lived between death and a new birth, and in your limb-metabolism organism, and especially in your fingertips and toes, you have, in essence, the human being as he is here on earth. And only because you experience your fingertips and toes in your brain do you also have, through thoughts, an awareness of this I in your earthly life. How grotesque things are in reality compared to what people usually imagine today.

[ 12 ] To imagine this with the head, as happens today, actually only began regularly with the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, with the 15th century. But all things proceed in a certain sense in an Ahrimanic way; they are anticipated. The Luciferic is that which comes later than is justified in evolution; the Ahrimanic comes earlier. And so we have the opportunity to point to a phenomenon in history where something that should have occurred in the 15th century occurred much earlier. It did occur then, but it had already been anticipated at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha. And here we can point out how the Old Testament ideas, which I characterized somewhat yesterday, were turned into allegories by the contemporary of Christ Jesus, Philo of Alexandria.

[ 13 ] Philo of Alexandria interprets the entire Old Testament allegorically, that is, he wants to turn the entire Old Testament, which is presented in the form of experiences, into thought images. This is very ingenious, and since it appears for the first time in human evolution, one can also speak of this ingenuity. Today, it is less ingenious when, for example, theosophists explain “Hamlet” by saying that one character is Manas, another is Buddhi, and so on, when the whole thing is dragged into allegory. That is nonsense, of course. But Philo of Alexandria transformed the entire Testament into thought images, into allegories. These allegories are nothing more than the inner revelation of the dead soul life, the soul life that has died and lies as a corpse in the power of thought. The Old Testament view looked back in its own way to life before birth or before conception, and from this view it created the Old Testament.

[ 14 ] When it was no longer possible to look back, and Philo of Alexandria could not look back, all this became dead thought images. And so, in the historical development of humanity, we have these two significant phenomena side by side: the Old Testament development culminated in Philo of Alexandria at the time of the Mystery of Golgotha. Philo of Alexandria turns the entire Old Testament into a world of straw allegories. And at the same time, the Mystery of Golgotha reveals that it is not dead experience in human beings that can lead to the supersensible, but the whole human being who passes through the Mystery of Golgotha with the divine being within them.

[ 15 ] These are the two great polar opposites: the abstract world, which is anticipated in an Ahrimanic way in Philo, and the world that is to enter human evolution with Christianity. One might say that from this point of view, the whole world becomes a question. The abstract thinker—and Philo of Alexandria was perhaps the most brilliant abstract thinker, because he anticipated the later abstract thinking of Ahriman—wants to find the answer to the mystery of the world by forming thoughts that are supposed to solve the riddle of the world. In contrast, the mystery of Golgotha is the comprehensive, living protest. Thoughts never solve the riddle of the world; rather, this solution remains alive. Human beings themselves, in their totality, are the solution to the riddle of the world. The suns, the stars, the clouds, the rivers, the mountains, the individual beings of the various natural kingdoms appear as a great question when they reveal themselves from outside. And human beings stand there, and in their entire being they are the answer.

[ 16 ] This is also a point of view from which the mystery of Golgotha can be considered. One does not seek to counter the mystery of the world with thoughts in their deadness; one counters the whole human being with what can be experienced from the whole human being.

[ 17 ] Only very slowly and gradually has humanity been able to find the way to understand this. And today it has not yet been found. Anthroposophy wants to open up this path. But since abstraction has gained ground, we have, in a sense, even lost the awareness that this path must be sought. Until then, there was a struggle for it, and this struggle is most clearly evident at this turning point from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean epoch. As Christianity spreads as an outer phenomenon, the best minds are struggling to understand it inwardly. It is basically a continuous struggle for the meaning of Christianity that takes place among the best minds. They wanted, in a sense, to present the mystery of the world to human beings in a living way, that is, to truly understand human beings as such. They had simply taken over the two currents from ancient times: on the one hand, the pagan current, which was basically a natural wisdom that saw spiritual-elemental beings, demonic beings, precisely those demonic beings of which the Gospel tells us, pointing out that the demons rebelled when Christ came among men because they now knew that their dominion was at an end. People did not recognize Christ. The demons recognized him. They knew that he would now take possession of the hearts and souls of human beings; they had to withdraw. But they continued to play a role in the minds and in the striving for knowledge of human beings for a long time. The pagan consciousness, which sought the demonic-elemental-spiritual nature in all natural beings in the old way, continued to play a role for a long time. It was a struggle for that kind of knowledge which was now to seek everywhere in the earthly realm that which, through the Mystery of Golgotha, had united itself with earthly life as the substance of Christ Himself.