Old and New Methods of Initiation

GA 210

19 February 1922, Dornach

Lecture X

We have once more pointed out in these lectures that in the most recent cultural period of human evolution, the fifth post-Atlantean period, the main force governing human soul life is the force of the intellect, the force of ideas living in thoughts. To this we had to add the statement that the force of thoughts is actually the corpse of our life of spirit and soul as it was before birth. More and more strongly in recent times this force of thought has emancipated itself from the other forces of the human being, and this was clearly felt by those spirits who wanted to attain a full understanding of the Christian impulse.

Yesterday I endeavoured to describe this, using the example of Calderón's Cyprianus. That drama depicts, on the one hand, the struggles which arise out of the old ideas of a nature filled with soul and, on the other, the strong sense of helplessness encountered by the human being who distances himself from this old view and is forced to seek shelter in mere thoughts. We saw how Cyprianus had to seek the assistance of Satan in order to win Justina—whose significance I endeavoured to explain. But in consequence of the new soul principle, which is now dominant, all he could receive from Satan was a phantom of Justina.

All these things show forcefully how human beings, striving for the spirit, felt in this new age, how they felt the deadness of mere thought life and how, at the same time, they felt that it would be impossible to enter with these mere thoughts into the living realm of the Christ concept. I then went on yesterday to show that the phase depicted in Calderon's Cyprianus drama is followed by another, which we find in Goethe's Faust. Goethe is a personality who stands fully in the cultural life of the eighteenth century, which was actually far more international than were later times, and which also had a really strong feeling for the intellectual realm, the realm of thoughts. We can certainly say that in his young days Goethe explored all the different sciences much as did the Faust he depicts in his drama. For in what the intellectual realm had to offer, Goethe did not seek what most people habitually seek; he was searching for a genuine connection with the world to which the eternal nature of man belongs. We can certainly say that Goethe sought true knowledge. But he could not find it through the various sciences at his disposal. Perhaps Goethe approached the figure of Faust in an external way to start with. But because of his own special inclinations he sensed in this Faust figure the struggling human being about whom we spoke yesterday. And in a certain sense he identified with this struggling human being.

Goethe worked on Faust in three stages. The first stage leads us back to his early youth when he felt utterly dissatisfied with his university studies and longed to escape from it all and find a true union of soul with the whole of cultural life. Faust was depicted as the struggling human being, the human being striving to escape from mere intellect into a full comprehension of the cosmic origins of man. So this early figure of Faust takes his place beside the other characters simply as the striving human being. Then Goethe underwent those stages of his development during which he submerged himself in the art of the South which he saw as giving form on a higher plane to the essence of nature. He increasingly sought the spirit in nature, for he could not find it in the cultural life that at first presented itself to him. A deep longing led him to the art of the South, which he regarded as the last remnant of Greek art. There, in the way the secrets of nature were depicted artistically out of the Greek world view, he believed he would discover the spirituality of nature.

And then everything he had experienced in Italy underwent a transformation within his soul. We see this transformation given living expression in the intimate form of his fairy-tale1 Floris Books, Edinburgh 1979. See, for instance, Rudolf Steiner, The Portal of Initiation & The Character of Goethe's Spirit as Shown in the Fairy Story (incl. a translation of the Fairy Story by Thomas Carlyle), Rudolf Steiner Press, New Jersey 1961. about the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily, in which, out of certain traditional concepts of beauty, wisdom, virtue and strength, he created the temple with the four Kings.

Then, at the end of the eighteenth century, we see how, encouraged by Schiller, he returns to Faust, enriched with this world of ideas. This second stage of his work on Faust is marked particularly by the appearance of the ‘Prologue in Heaven’, that wonderful poem which begins with the words: ‘The sun makes music as of old, Amid the rival spheres of heaven.’2 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust, Part One, ‘Prologue in Heaven’. The English versions of the quotations from Faust are taken from the translation by Bayard Taylor, with the exception of these lines from the ‘Prologue in Heaven’, which are translated by Shelley. (Tr.) In the drama as Goethe now conceives it, Faust no longer stands there as a solitary figure concerned solely with himself. Now we have the cosmos with all the forces of the universe ascending and descending, and within this cosmos the human being whom the powers of good and evil do battle to possess. Faust takes his place within the cosmos as a whole. Goethe has expanded the material from a question of man alone to a question encompassing the whole of the universe.

The third stage begins in the twenties of the nineteenth century, when Goethe sets about completing the drama. Once again quite new thoughts live in his soul, very different from those with which he was concerned at the end of the eighteenth century when he composed the ‘Prologue in Heaven’, using ancient ideas about nature, ideas of the spirit in nature, in order to raise the question of Faust to the level of a question of the cosmos. In the twenties, working to bring the second part of the drama to a conclusion, Goethe has returned once more to the human soul out of which he now wants to draw everything, expanding the soul-being once more into a cosmic being.

Of course he has to make use of external representations, but we see how he depicts dramatically the inner journeyings of the soul. Consider the ‘Classical Walpurgis-Night’ or the reappearance of the Helena scene, which had been there earlier, though merely in the form of an episode. And consider how, in the great final tableau, he endeavours to bring to a concluding climax the soul's inner experience, which is at the same time a cosmic experience when it becomes spiritual. Finally the drama flows over into a Christian element. But, as I said yesterday, this Christian element is not developed out of Faust's experiences of soul but is merely tacked on to the end. Goethe made a study of the Catholic cultus and then tacked this Christianizing element on to the end of Faust. There is only an external connection between Faust's inner struggles and the way in which the drama finally leads into this Christian tableau of the universe. This is not intended to belittle the Faust drama. But it has to be said that Goethe, who wrestled in the deepest sense of the word to depict how the spiritual world should be found in earthly life, did not, in fact, succeed in discovering a way of depicting this finding of spirituality in earthly life. To do so, he would have had to come to a full comprehension of the meaning of the Mystery of Golgotha. He would have had to understand how the Christ-being came from the expanses of the cosmos and descended into the human being, Jesus of Nazareth, and how he united himself with the earth, so that ever since then, when seeking the spirit which ebbs and flows in the stormy deeds of man, one ought to find the Christ-impulse in earthly life.

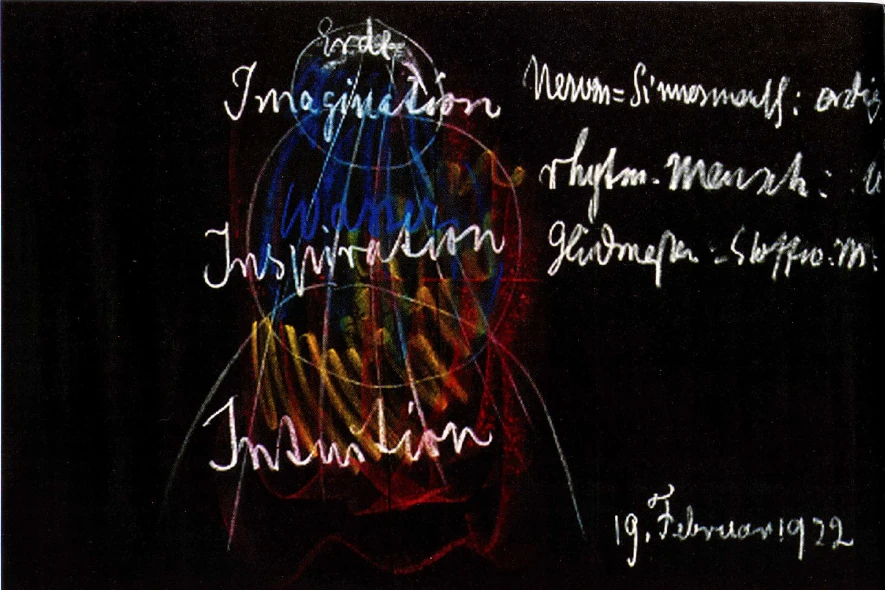

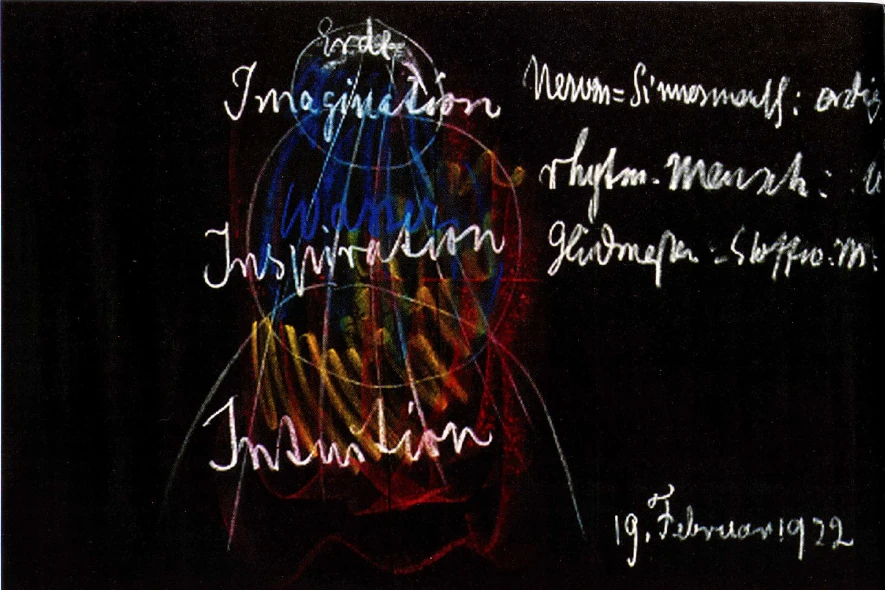

Goethe was never able to make the link between the spirit of the earth, ebbing and flowing in stormy deeds, in the weaving of time, and the Christ-impulse. In a way this may be felt to be a tragedy. But it came about of necessity, because the period of human evolution in which Goethe stood did not yet provide the ground on which the full significance of the Mystery of Golgotha could be comprehended. Indeed, this Mystery of Golgotha can only be fully comprehended if human beings learn to give new life to the dead thoughts which are a part of them in this fifth post-Atlantean period. Today there is a tremendous amount of prejudice, in thought, in feeling and in will, against the re-enlivening of the world of thought. But mankind must solve this problem. Mankind must learn to give new life to this world of thought which enters human nature at birth and conception as the corpse of spirit and soul; this corpse of thoughts and ideas must be made to live again. But this can only happen when thoughts are transformed—first into Imaginations, and then the Imaginations transformed into Inspirations and Intuitions. What is needed is a full understanding of the human being. Not until this becomes a reality, will what I told you yesterday be fully understood: That the world around us must come to be seen as a tremendous question to which the human being himself provides the answer. This is what was to have been given to mankind with the Mystery of Golgotha. It will not be understood until the human being is understood.

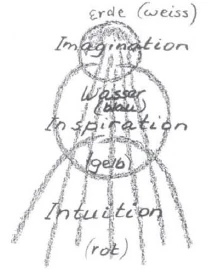

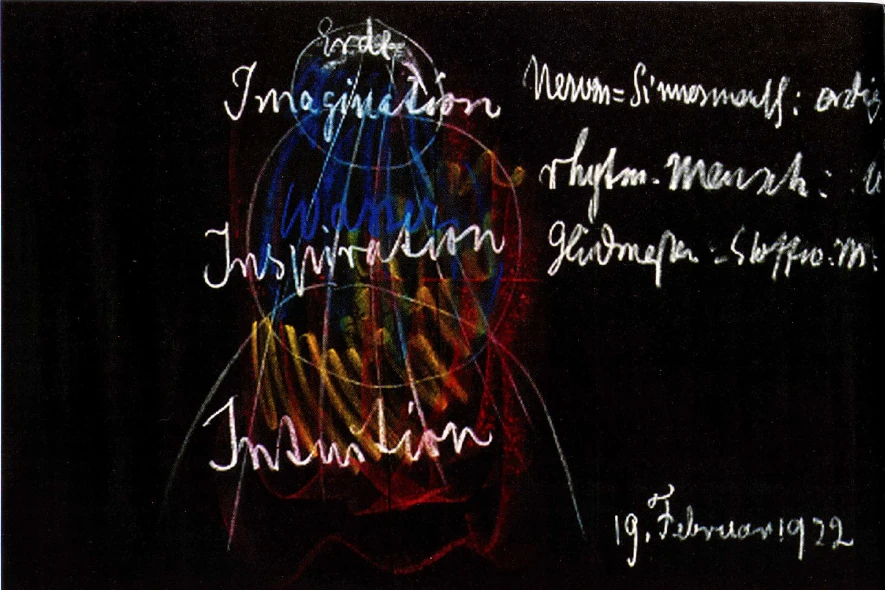

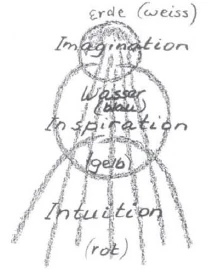

Let us look at a diagram of threefold man once more: the human being of the head or of the nerves and senses as discussed yesterday;

Earth

the human being of the rhythmic system or of the chest; and the human being of the metabolism and limbs.

Looking at the human being today, we accept him as the external form in which he appears to us. Someone dissecting a body on the dissecting table has no special feeling that the human head, for instance, is in any way very different from, say, a finger. A finger muscle is considered in the same way as is a muscle in the head. But it ought to be known that the head is, in the main, a metamorphosis of the system of limbs and metabolism from the preceding incarnation; in other words, the head occupies a place in evolution which is quite different from that of the system of limbs that goes with it.

Having at last struggled through to a view of the inner aspect of threefold man, we shall then be in a position to come to a view of what is linked from the cosmos with this threefold human being. As far as our external being is concerned, we are in fact only incarnated in the solid, earthly realm through our head organization. We should never be approachable as a creature of the solid earth if we did not possess our head organization, which is, however, an echo of the limb organization of our previous incarnation. The fact that we have solid parts also in our hands and feet is the result of what rays down from the head. But it is our head which makes us solid. Everything solid and earthly in us derives from our head, as far as the forces in it are concerned.

In our head the solid earth is in us. And whatever is solid anywhere else in our body rays down through us from our head. The origin of our solid bones lies in our head. But there is also in our head a transition to the watery element. All the solid parts of our brain are embedded in the cerebral fluid. In our head there is a constant inter-mingling vibration of the solid parts of our brain with the cerebral fluid which is linked to the rest of the body by way of the spinal fluid. So, looking at the human being of nerves and senses, we can say that here is the transition from the earthly element (blue) to the watery element. We can say that the human being of nerves and senses lives in the earthy-watery element. And in accordance with this, our brain consists of an intercorrespondence between the earthy and watery elements.

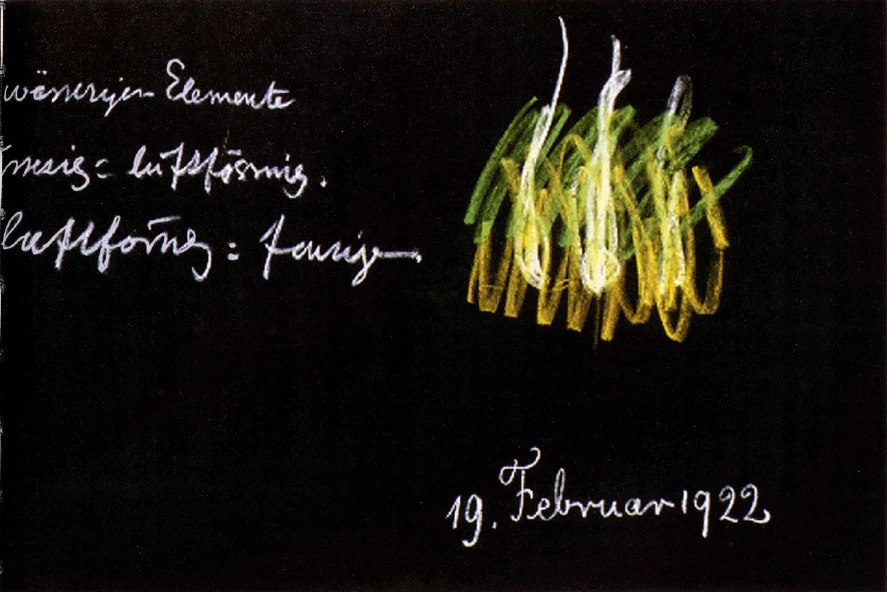

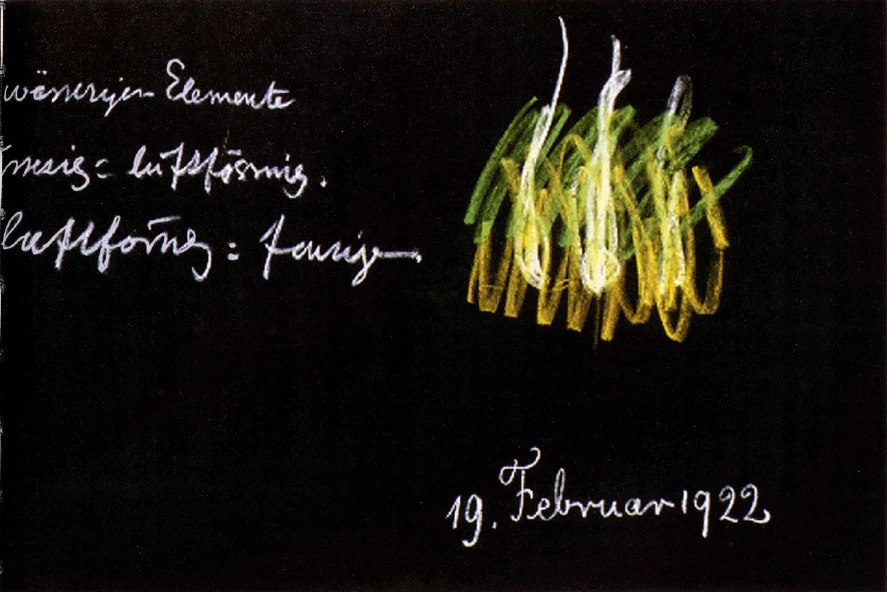

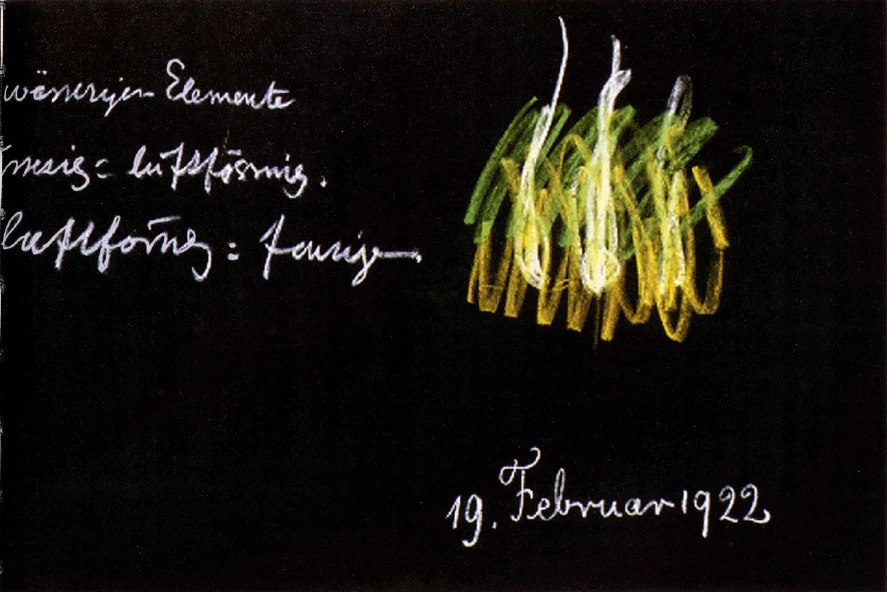

Now let us turn to the chest organism, the rhythmic organism. This rhythmic organism lives in the interrelationship between the watery and the airy element (yellow). In the lungs you can see the watery element making contact with the airy element. The rhythmic life is anintermingling of the watery with the airy element, of water with air. So I could say: The rhythmical human being lives in the watery-airy element.

And the human being of metabolism and limbs then lives in the transition from the airy element to the warmth element, in the fiery element (red, next diagram). It is a constant dissolving of the airy element in the warmth, the fiery element, which then seeps through the whole human being as his body heat. What happens in our metabolism and in our movements is a reorganization of the airy, gaseous element up into the warm, fiery element. As we move about, we constantly burn up those elements of the food we have eaten which have become airy. Even when we do not move about, the foods we eat are transformed airy elements which we constantly burn up in the warmth element. So the human being of limbs and metabolism lives in the airy-fiery element.

Human being of nerves and senses: earthy-watery element

Rhythmical human being: watery-airy element

Human being of limbs and metabolism: airy-fiery element

From here we go up even further into the etheric parts, into the light element, into the etheric body of the human being. When the organism of metabolism and limbs has transferred everything into warmth, it then goes up into the etheric body. Here the human being joins up with the etheric realm which fills the whole world; here he makes the link with the cosmos.

Ideas like this, which I have shown you only as diagrams, can be transformed into artistic and poetic form by someone who has an inner sense for sculpture and music. In a work of poetry such as the drama of Faust such things can certainly be expressed in artistic form, in the way certain cosmic secrets are expressed, for instance, in the seventh scene of my first Mystery Drama.3 The Portal of Initiation. A Rosicrucian Mystery through Rudolf Steiner, transl. Ruth and Hans Pusch, Steiner Book Centre, Toronto, 1973. This leads to the possibility of seeing the human being linked once more with the cosmos. But for this we cannot apply to the human being what our intellect teaches us about external nature. You must understand that if you study external nature, and then study your head in the same way as you would external nature, you are then studying something which simply does not belong to external nature as it now is, but something that comes from your former incarnation. You are studying something as though it had arisen at the present moment; but it is not something that has arisen out of the present moment, nor could it ever arise out of the present moment. For a human head could not possibly arise out of the forces of nature which exist. So the human head must not be studied in the same way as objects are studied with the intellect. It must be studied with the knowledge given by Imagination. The human head will not be understood until it is studied with the knowledge given by Imagination.

In the rhythmical human being everything comes into movement. Here we have to do with the watery and the airy elements. Everything

is in surging movement. The external, solid parts of our breast organization are only what our head sends down into this surging motion. To study the rhythmical human being we have to say that in this rhythmical surging the watery element and the airy element mingle together (see diagram, green, yellow). Into this, the head sends the possibility for the solid parts, such as those in the lungs, to be present (white). This surging, which is the real rhythmical human being, can only be studied with the knowledge given by Inspiration. So the rhythmical human being can only be studied with the knowledge given by Inspiration.

And the human being of limbs and metabolism—this is the continuous burning of the air in us. You stand within it, in your warmth you feel yourself to be a human being, but this is a very obscure idea. It can only be studied properly with the knowledge given by Intuition, in which the soul stands within the object. Only the knowledge given by Intuition can lead to the human being of metabolism and limbs.

The human being will remain forever unknown if he is not studied with the knowledge given by Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition. He will forever remain the external shell which is all that is recognized today, both in general and in science. This situation must not be allowed to remain. The human being must come once more to be recognized for what he is. If you study only the solid parts of the human being, the parts which are shown in the illustrations in anatomy textbooks, then, right from the start, you are studying wrongly. Your study ought to be in the realm of Imagination, because all these illustrations of the solid parts of the human organism ought to be taken as images brought over from the previous incarnation. This is the first thing. Then come the even more delicate parts which live in the physical constituents. These can only be studied with the knowledge given by Inspiration. And the airy-watery element can only be studied with the knowledge given by Intuition. These things must be taken into European consciousness, indeed into the whole of modern civilization. If we fail to place them in the mainstream of culture, our civilization will only go downhill instead of upwards.

When you understand what Goethe intended with his Faust, you sense that he was endeavouring to pass through a certain gateway. Everywhere he is struggling with the question: What is it that we need to know about this human being? As a very young man he began to study the human form. Read his discourse on the intermaxillary bone and also what I wrote about it in my edition of his scientific writings.4 Rudolf Steiner Goethes Naturwissenschaftliche Schriften, mit Einleitungen, Fussnoten und Erlauterungen im Text (Goethe's Natural Scientific Writings) in Kürschners Deutsche National-Litteratur. On the intermaxillary bone see Volume 1. He is endeavouring so hard to come to an understanding of man. First he tried by way of anatomy and physiology. Then in the nineties he explored the aspect of moral ideas which we find in the fairy tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily. Then, in Faust, he wants to depict the human being as he stands in the world. He is trying to pass through a gateway in order to discover how the human being does, in fact, stand in the world. But he lacks the necessary prerequisites; he cannot do it.

When Calderón wrote his drama about Cyprianus, the struggle was still taking place at a previous level. We see how Justina tears herself free of Satan's clutches, how Cyprianus goes mad, how they find one another in death, and how their salvation comes as they meet their end on the scaffold. Above them the serpent appears—on it rides the demon who is forced to announce their salvation.

We see that at the time when Calderon was writing his Cyprianus drama the message to be clearly stated was: You cannot find the divine, spiritual realm here on earth. First you must die and go through the portal of death; then you will discover the divine spiritual world, that salvation which you can find through Christ. They were still far from understanding the Mystery of Golgotha through which Christ had descended to earth, where it now ought to be possible to find him. Calderon still has too many heathen and Jewish elements in his ideas for him to have a fully developed sense for Christianity.

After that, a good deal of time passed before Goethe started to work on his Faust. He sensed that it was necessary for Faust to find his salvation here on earth. The question he should therefore have asked was: How can Faust discover the truth of Paul's words: ‘Not I, but Christ in me’?5 Galatians 2, 20 Goethe should have let his Faust say not only, to ‘Stand on free soil among a people free’,6 Part Two, Act 5, Great Outer Court of the Palace. but also: to ‘stand on free soil with Christ in one's soul leading the human being in earthly life to the spirit’. Goethe should have let Faust say something like this. But Goethe is honest; he does not say it because he has not yet fully understood it. But he is striving to understand it. He is striving for something which can only be achieved when it is possible to say: Learn to know man through Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition. That he is striving in this way gives us the feeling that there is much more in his struggle and in his endeavour than he ever managed to express or than has filtered through into today's culture. Perhaps he can only be fully recognized by doing what I did in my early writings when I endeavoured to express the ‘world view which lived almost unconsciously in him. However, on the whole, his search has met with little understanding amongst the people of today.

When I look at this whole situation in connection with modern civilization, I am constantly reminded of my old teacher and friend, Karl Julius Schröer.7Karl Julius Schröer, 1825-1900. On his booklet Goethe und die Liebe (Goethe and Love) see Rudolf Steiner's collected essays 1921-1925 in Der Goetheanumgedanke inmitten der Kulturkrisis der Gegenwart, p.111. GA 36. I think particularly of how, in the eighties of the last century, Schröer was working on Faust and on Goethe's other plays, writing commentaries, introductions and so on. He was not in the least concerned to speak about Goethe in clearly defined concepts but merely gave general indications. Yet he was at pains to make people understand that what lived most profoundly in Goethe must enter into mainstream modern culture. On the fiftieth anniversary of Goethe's death, in 1882, Schröer gave an address: ‘How the future will see Goethe’. He lived with the dream that the time had already come for a kind of resurrection of Goethe. Then we wrote a short essay in Die Neue Freie Presse which was reprinted in the booklet ‘Goethe and Love’. This and other of his writings have now been acquired by our publisher, Der Kommende Tag, so remaindered copies can be acquired there, and there will also be new editions eventually. This essay ‘Goethe after 50 Years’ is a brief extract from that lecture, at which I was present. It contains a good deal of what Schröer felt at that time regarding the need for Goethe to be assimilated into modern culture. And then in this booklet ‘Goethe and Love’ he endeavoured to show in the notes how Goethe could be made to come alive, for to bring Goethe to life is, in a sense, to bring the world of abstract thoughts to life. In the recent number of Das Goetheanum I referred to a beautiful passage about this in the booklet ‘Goethe and Love’. Schröer says: ‘Schiller recognized him. When an intuitive genius searches for the character of necessity in the empirical realm, he will always produce individuals even though these may have a generic aspect. With his intuitive method of seeing the eternal idea, the primeval type, in the mortal individual, Goethe is perhaps not as alone as one might assume.’

While Schröer was writing this booklet in 1882 I visited him a number of times. He was filled to the brim with an impression he had had. He had heard somewhere how Oppolzer, a physician in Vienna, used a rather vague intuitive faculty when making his diagnoses. Instead of examining the patient in the usual way, he allowed the type of the patient to make an impression on him, and from the type of the patient he deduced something of the type of the illness. This made a strong impression on Schröer, and he used this phenomenon to enlarge on what he was trying to explain: ‘In medicine we extol the ability of great diagnosticians to fathom the disease by intuitively discerning the individual patient's type, his habitude. They are not helped by chemical or anatomical knowledge but by an intuitive sense for the living creature as a whole being. They are creative spirits who see the sun because their eyeis sunlike. Others do not see the sun. What these diagnosticians are doing unconsciously is to follow the intuitive method which Goethe consciously applied as a means of scientific study. The results he achieved are no longer disputed, though the method is not yet generally recognized.’

Out of a conspectus which included Oppolzer's intuitive bedside method, Schröer even then was pointing out that the different sciences, for example, medicine, needed fructifying by a method which worked together with the spirit.

It is rather tragic to look back and see in Schröer one of the last of those who still sensed what was most profound in Goethe. At the beginning of the eighties of the last century Schroer believed that there would have to be a Goethe revival, but soon after that Goethe was truly nailed into his coffin and buried with sweeping finality. His grave, we could say, was in Central Europe, in the Goethe-Gesellschaft, whose English branch was called the Goethe Society. This is where the living Goethe was buried. But now it is necessary to bring this living element, which was in Goethe, back into our culture. Karl Julius Schroer's instinct was good. In his day he was unable to fulfil it because his contemporaries continued to worship the dead Goethe. ‘He who would study organic existence, first drives out the soul with rigid persistence.’8 Faust Part One. The Study.

This became the motto, and in some very wide circles this motto has intensified into a hatred against any talk of spiritual things—as you can see in the way Anthroposophy is received by many people.

Today's culture, which all of you have as your background, urgently needs this element of revival. It is quite extraordinary how much talk there is today of Goethe's Faust, which after all simply represents a new stage in the struggle for the spirit which we saw in Calderón's Cyprianus drama. So much is said about Faust, yet there is no understanding for the task of the present time, which is to bring fully to life what Goethe brought to life in his Faust, especially in the second part. Goethe brought it to life in a vague, intuitive sensing, though not with full spiritual insight. We ought to turn our full attention to this, for indeed it is not only a matter of a world view. It is a matter of our whole culture and civilization. There are many symptoms, if only we can see them in the right light.

Here is an essay by Ruedorffer9 J.J. Ruedorffer, Die drei Krisen. Eine Untersuchung fiber den gegenwartigen politischen Weltzustand (The Three Crises. A consideration of the present state of world politics.) Stuttgart/Berlin 1920. entitled ‘The Three Crises’. Every page gives us a painful knock. The writer played important roles in the diplomatic and political life of Europe before the war and on into the war. Now, with his intimate knowledge of the highways and byways of European-life, and because he was able to observe things from vantage points not open to most, he is seeking an explanation of what is actually going on. I need only read you a few passages. He wants to be a realist, not an idealist. During the course of his diplomatic career he has developed a sober view of life. And despite the fact that he has written such things as the passages I am going to read to you he remains that much appreciated character, a bourgeois philistine.

He deals with three things in his essay. Firstly he says that the countries and nations of Europe no longer have any relationship with one another. Then he says that the governing circles, the leaders of the different nations, have no relationship with the population. And thirdly he says that those people in particular who want to work out and found a new age by radical means most certainly have no relationship with reality.

So a person who played his part in bringing about the situation that now exists writes: ‘This sickness of the state organism snatches leadership away from good sense and hands responsibility for decisions of state to all sorts of minor influences and secondary considerations. It inhibits freedom of movement, fragments the national will and usually also leads to a dangerous instability of governments. The period of unruly nationalism that preceded the war, the war itself, and the situation in Europe since the war, have made monstrous demands on the good sense of all the states, and on their peace and their freedom to manoevre. The loss of wealth brought about by necessary measures has completed the catastrophe. The crisis of the state and the crisis in world-wide organization have mutually exacerbated the situation, each magnifying the destructive effect of the other.’ These are not the words of an idealist, or of some artistic spirit who watched from the sidelines, but of someone who shared in creating the situation. He says, for instance: ‘If democracy is to endure, it must be honest and courageous enough to call a spade a spade, even if it means bearing witness against itself. Europe faces ruin.’

So it is not only pessimistic idealists who say that Europe is faced with ruin. The same is said especially by those who stood in the midst of practical life. One of these very people says:

‘Europe faces ruin. There is no time to waste by covering up mistakes for party political reasons, instead of setting about putting them to rights. It is for this reason alone, and not to set myself up as laudator temporis acti, that I have to stress that democracy must, and will, destroy itself if it cannot free the state from this snare of minor influences and secondary considerations. Pre-war Europe collapsed because all the countries of the continent—the monarchies as well as the democracies and, above all, autocratic Russia—succumbed to demagogy, partly voluntarily, partly unconsciously, partly with reluctance because their hand was forced. In the confusion of mind, for which they had only themselves to thank, they were incapable of recognizing good sense, and even if they had recognized it they would have been incapable of acting on it freely and decisively. The higher social strata of the old states of Europe—who, in the last century, were certainly the bearers of European culture and rich in personalities of statesmanlike quality and much world experience—would not have been so easily thrown from the saddle, rotten and expended, if they had grown with the problems and tasks of new times, if they had not lost their statesmanlike spirit, and if they had preserved any more worthwhile tradition than that of the most trivial diplomatic routine. If monarchs claim the ability to select statesmen more proficiently and expertly than governments, then they and their courts must be the centre and epitome of culture, insight and understanding. Long before the war this ceased to be the case. But indictment of the monarchs’ failures does not exonerate the democracies from recognizing the causes of their own inadequacies or from doing everything possible to eliminate them. Before Europe can recover, before any attempt can be made to replace its hopeless disorganization with a durable political structure, the individual countries will have to tidy up their internal affairs to an extent which will free their governments for long-term serious work. Otherwise, the best will in the world and the greatest capability will be paralysed, tied down by the web of the disaster which is the same wherever we look.’

I would not bother to read all this to you if it had been written by an idealist, instead of by someone who considers his feet to be firmly on the ground of reality because he played a part in bringing the current situation about.

‘The drama is deeply tragic. Every attempt at improvement, every word of change, becomes entangled in this web, throttled by a thousand threads, until it falls to the ground without effect. The citizens of Europe—thoughtlessly clutching the contemporary erroneous belief in the constant progress of mankind, or, with loud lamentations trotting along in the same old rut—fail to see, and do not want to see, that they are living off the stored-up labour of earlier years; they are barely capable of recognizing the present broken-down state of the world order, and are certainly incapable of bringing a new one to birth. On the other hand, the workers, treading a radical path in almost every country and convinced of the untenability of the present situation, believe themselves to be the bringers of salvation through a new order of things; but in reality this belief has made them into nothing more than an unconscious tool of destruction and decline, their own included. The new parasites of economic disorganization, the complaining rich of yester-year, the petit bourgeois descending to the level of the proletariat, the gullible worker believing himself to be the founder of a new world—all of them seem to be engulfed by the same disaster, all of them are blind men digging their own grave.’

Remember, this is not written by an idealist, but by one who shared in bringing about this situation!

‘But every political factor today—the recent peace treaties of the Entente, the Polish invasion of the Ukraine, the blindness or helplessness of the Entente with regard to developments in Germany and Austria—proves to the politician who depends on reality that although idealistic demands for a pan-European, constructive revision of the Paris peace treaties can be made, although the most urgent warnings can be shockingly justified, nevertheless, both demands and warnings can but die away unnoticed while everything rolls on unchanged towards the inevitable end—the abyss.’

The whole book is written in order to prove that Europe has come to the brink of the abyss and that we are currently employed in digging the grave of European civilization. But all this is only an introduction to what I now find it necessary to say to you. What I have to say is something different. Here we have a man who was himself an occupant of crucial seats of office, a man who realizes that Europe is on the brink of the abyss. And yet—as we can see in the whole of his book—all he has to say is: If all that happens is only a continuation of older impulses, then civilization will perish; it will definitely perish. Something new must come.

So now let me search for this new thing to which he wants to point. Yes, here it is, on page 67; here it is, in three lines: ‘Only a change of heart in the world, a change of will by the major powers, can lead to the creation of a supreme council of European good sense.’

Yes, this is the decision that faces these people. They point out that only if a change of heart comes about, if something entirely new is brought into being, can the situation be saved. This whole book is written to show that without this there can be no salvation. There is a good deal of truth in this. For, in truth, salvation for our collapsing civilization can only come from a spiritual life drawn from the real sources of the spirit. There is no other salvation. Without it, modern civilization, in so far as it is founded in Europe and reaches across to America, is drawing towards its close. Decay is the most important phenomenon of our time. There is no help in reaching compromises with decay. Help can only come from turning to something that can flourish above the grave, because it is more powerful than death. And that is spiritual life. But people like the writer of this book have only the most abstract notion of what this entails. They say an international change of heart must take place. If anything is said about a real, new blossoming of spiritual life, this is branded as ‘useless mysticism’. All people can say is: Look at them, bringing up all kinds of occult and mystical things; we must have nothing to do with them.

Those who are digging the grave of modern civilization most busily are those who actually have the insight to see that the digging is going on. But the only real way of taking up a stance with regard to these things is to look at them squarely, with great earnestness—to meditate earnestly on the fact that a new spiritual life is what is needed and that it is necessary to search for this spiritual life, so that at last a way may be found of finding Christ within earthly life, and of finding Him as He has become since the Mystery of Golgotha. For He descended in order to unite with the conditions of the earth.

The strongest battle against real Christian truth is being fought today by a certain kind of theology which raises its hands in horror at any mention of the cosmic Christ. It is necessary to be reminded again and again that even in the days when Schröer was pointing to Goethe as a source for a regeneration of civilization, a book appeared by a professor in Basel—a friend of Nietzsche—about modern Christian theology. Overbeck10Franz Overbeck, 1837-1905. considered at that time that theology was the most un-Christian thing, and as a historian of theology he sought to prove this. So there was at that time in Basel a professor of theological history who set out to prove that theology is un-Christian!

Mankind has drifted inevitably towards catastrophe because it failed to hear the isolated calls, which did exist but which were, it must be said, still very unclear. Today there is no longer any time to lose.

Today mankind must know that descriptions such as that given by Ruedorffer are most definitely true and that it is most definitely necessary to realize how everything is collapsing because of the continuation of the old impulses. There is only one course to follow: We must turn towards what can grow out of the grave, out of the living spirit.

This is what must be pointed out ever and again, especially in connection with the things with which we are concerned.

Die Angliederung des Menschen an den Kosmos

[ 1 ] Wir haben in diesen Betrachtungen noch einmal darauf hingewiesen, wie in dem letzten Kulturzeitraum, den wir in der Menschheitsentwickelung zu verzeichnen haben - in dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum — die hauptsächlichste Kraft, von der das menschliche Seelenleben beherrscht ist, die intellektuelle Kraft ist, die Verstandeskraft, die in Gedanken lebt. Und wir haben nun hinzufügen müssen, daß die Kraft der Gedanken eigentlich darstellt den Leichnam des geistig-seelischen Lebens, wie es vor der Geburt war. Immer stärker und stärker emanzipierte sich in gewissem Sinne diese Gedankenkraft von den andern Kräften der Menschenwesenheit in der neueren Zeit, und das wurde stark gefühlt von denjenigen Geistern, welche zu einem vollen Verständnisse des christlichen Impulses kommen wollten.

[ 2 ] Das habe ich gestern versucht darzustellen an dem Beispiel des Calderónschen Cyprianus. Wir haben da das Ringen auf der einen Seite aus den alten Vorstellungen einer durchseelten Natur heraus, aber zu gleicher Zeit ein starkes Gefühl von der Ohnmacht, in die der Mensch eigentlich hineinkommt, wenn er sich von der alten Anschauung entfernt und nun gezwungen ist, bei bloßen Gedanken seine Zuflucht zu suchen. Gerade bei Cyprianus sehen wir, wie er, um sich Justinas zu bemächtigen - deren Bedeutung ich gestern versuchte darzulegen -, bei dem Satan seine Zuflucht sucht, wie er aber gerade infolge des hauptsächlichsten neueren Seelenprinzips von diesem Satan nur das Phantom der Justina bekommen kann.

[ 3 ] Alle diese Dinge weisen eben stark darauf hin, wie das Gefühl der nach dem Geistigen strebenden Menschen in diesem neuesten Zeitraum der Menschheitsentwickelung war, wie sie das Tote des bloßen Gedankenlebens fühlten, und wie sie zu gleicher Zeit fühlten, daß in die Lebendigkeit der Christus-Auffassung nicht hineinzukommen sei mit diesem bloßen Gedankenleben. Nun habe ich schon gestern darauf hingedeutet, daß gewissermaßen eine weitere Phase desselben Problems, das uns bei dem Calderónschen Cyprianus entgegentritt, dann im Goetheschen «Faust» vor uns steht. In Goethe hat man ja eine menschliche Persönlichkeit zu sehen, welche hineingestellt ist in das Zivilisationsleben des 18. Jahrhunderts — das im Grunde genommen viel internationaler war als alles spätere Zivilisationsleben — und welche stark, wirklich recht stark das Intellektualistische, das Verstandesmäßige empfindet. Man kann schon sagen: Goethe hat sich in seiner Jugend in den verschiedensten Wissenschaften so herumgerrieben, wie er das an seinem Faust darstellt. Denn Goethe suchte eben nicht das in dem Leben, das sich ihm als Intellektualistisches darbot, was aus einer gewissen menschlichen Gewohnheit heraus die meisten suchen, sondern er suchte eine wirkliche Verbindung mit derjenigen Welt, welcher der Mensch mit seiner ewigen Natur angehört. Man kann sagen, Goethe suchte wirkliche Erkenntnis. Diese konnte er durch die einzelnen Wissenschaften, die sich ihm darboten, eben nicht finden. Goethe kam vielleicht zunächst auf eine äußerliche Weise an die Faust-Gestalt heran. Aber jedenfalls hat er durch seine besondere Veranlagung in dieser Faust-Gestalt dasjenige gefühlt, was diesen ringenden Menschen darstellt, von dem wir gestern gesprochen haben. Und er identifizierte sich in einem gewissen Sinne mit diesem ringenden Menschen.

[ 4 ] Goethes Arbeit am «Faust» erscheint einem in drei Etappen. Die erste Etappe führt zurück in eine frühe Jugendzeit Goethes, in der er eben ganz empfunden hat das Unbefriedigende seiner Universitätsstudien, aus denen er heraus wollte zu einer wirklichen Verbindung der Seele mit dem vollen geistigen Leben. Da stellte er die FaustGestalt, die ihm entgegengetreten war aus dem «Puppenspiel», aus dem heraus man noch sehr wohl den ringenden Menschen erkennen kann, eben als den strebenden Menschen dar, der heraus will aus dem bloßen Verstandesmäßigen zu einem vollmenschlichen Erfassen des kosmischen Ursprungs des Menschen. Und so steht denn in der ersten Gestalt, die Goethe seinem «Faust» gegeben hat, Faust neben den andern einzelnen Figuren einfach als der strebende Mensch da. Dann ging Goethe durch diejenigen Entwickelungsstadien seines Lebens hindurch, die er zunächst durchgemacht hat, indem er sich in die noch im Süden vorhandene Kunst vertiefte, in der er gewissermaßen eine höhere Ausgestaltung des Wesens der Natur sah. Goethe suchte fortschreitend den Geist innerhalb der Natur. Er konnte ihn in dem Geistesleben nicht finden, das sich ihm zunächst dargeboten hatte. Eine tiefe Sehnsucht führte ihn zu dem, was er als die Reste der griechischen Kunst im Süden ansah. Da glaubte er in der Art und Weise, wie aus der griechischen Weltanschauung heraus die Naturgeheimnisse in den künstlerischen Gestaltungen verfolgt worden sind, die Geistigkeit der Natur zu erkennen.

[ 5 ] Dann, möchte ich sagen, machte das Ganze, was er da in Italien absolviert hatte, in seiner eigenen Seele eine Verwandlung durch. Wir sehen diese Verwandlung sich ausleben in der intimen Gestaltung, die er dem «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie» gegeben hat, wo er aus gewissen traditionellen Begriffen über Schönheit, über Weisheit, über Tugend und Kraft seinen Tempel formte mit den vier Königen.

[ 6 ] Wir sehen, wie dann aus dieser Vorstellungswelt heraus, angeeifert durch Schiller, Goethe am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts zurückkehrt zu seinem «Faust». Und dieses zweite Stadium seiner «Faust»-Arbeit drückt sich ja insbesondere dadurch aus, daß er den «Prolog im Himmel» hingestellt hat, jene wunderschöne Dichtung, die mit den Worten beginnt: «Die Sonne tönt nach alter Weise in Brudersphären Wettgesang.» Da steht dann, so wie Goethe jetzt die Faust-Dichtung umfassen will, Faust nicht mehr als eine einzelne Person da, die es nur mit sich selber zu tun hat; da steht gewissermaßen der Kosmos mit den auf- und absteigenden Weltenkräften, und hineingestellt in diesen Kosmos der Mensch, um den die guten und die bösen Mächte ringen. Da ist Faust in den ganzen Kosmos hineingestellt. Goethe hat gewissermaßen das Problem, das für ihn zunächst bloß ein Menschheitsproblem war, zum Weltenproblem ausgedehnt.

[ 7 ] Und eine dritte Phase tritt dann ein, als Goethe in den zwanziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts daran geht, den «Faust» zu vollenden. Da sind wieder ganz andere Gedankenformen in seiner Seele vorhanden als am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts, da er den «Prolog im Himmel» dichtete und alte Naturvorstellungen, vergeistigte Naturvorstellungen damals zu Hilfe genommen hatte, um das Faust-Problem zu einem kosmischen Problem zu machen. In den zwanziger Jahren, als er am zweiten Teile «Faust» zu Ende arbeitet, da will Goethe dann wiederum aus der menschlichen Seele heraus alles gewinnen, gewissermaßen wiederum das Seelenwesen zum Allwesen erweitern.

[ 8 ] Wir sehen, wie er dramatisch - selbstverständlich kann er das nur in äußeren Gestaltungen machen -, wie er aber innere Wege der Seele darstellt in der klassischen Walpurgisnacht, in dem Wieder-Auflebenlassen der Helena-Szene, die allerdings schon früher, aber nur als Episode, entstanden war, und wie er dann das innere Erleben, das zu gleicher Zeit ein kosmisches Erleben in der Seele ist, wenn dieses Erleben geistig wird, wie er das in dem großen Schlußtableau des «Faust» zu Ende zu führen versucht. Da mündet «Faust» allerdings ein in das christliche Element. Allein, ich habe schon gestern gesagt, dieses christliche Element entwickelt sich ja nicht aus der Seele des Faust heraus, sondern es ist gewissermaßen angeleimt. Goethe hat sich in die Form des katholischen Kultus vertieft und leimt dieses christianisierende Element an den «Faust» an, so daß zwischen dem Ringen des Faust und diesem Einmünden in das durchchristete Weltentableau doch nur ein äußerer Zusammenhang ist. Selbstverständlich setzt das den «Faust» nicht herunter, aber es ist doch so, daß man sagen muß: Goethe, der im tiefsten Sinne des Wortes gerungen hat, darzustellen, wie im irdischen Leben selber die Geistigkeit gefunden werden sollte, ihm ist es eigentlich nicht gelungen, dieses Finden der Geistigkeit im irdischen Leben irgendwie darzustellen. Er hätte dazu kommen müssen, das Mysterium von Golgatha in seinem Vollsinne zu begreifen, zu begreifen, wie wirklich aus kosmischen Weiten heruntergestiegen ist die Christus-Wesenheit in den Jesus von Nazareth, sich verbunden hat mit der Erde, so daß, wenn man seither den Erdgeist sucht, der im Tatensturm auf und ab wallt, eigentlich der Christus-Impuls im Erdenweben gefunden werden müßte.

[ 9 ] Man möchte sagen, daß Goethe niemals den Erdengeist, der im Tatensturm, im Zeitenweben auf und ab wallt, in Zusammenhang bringen konnte mit dem Christus-Impuls. Das ist in gewissem Sinne etwas, was wir als eine Art Iragik empfinden, die aber selbstverständlich dadurch gegeben ist, daß in jener Zeit menschlicher Entwickelung, in der Goethe stand, eben durchaus noch nicht die Bedingungen da waren, um das Mysterium von Golgatha in seinem Vollsinne zu empfinden. Und dieses Mysterium von Golgatha kann eigentlich in seinem Vollsinne nur empfunden werden, wenn die Menschen das, was sie im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum als die toten Gedanken haben, wiederum zu beleben verstehen. Heute spricht noch sehr viel Vorurteil und Vorempfindung und auch Vorwille gegen das Lebendigmachen der Gedankenwelt. Aber die Menschheit muß dieses Problem lösen: Die Gedankenwelt, die, wenn der Mensch konzipiert beziehungsweise geboren wird, als der Leichnam des Geistig-Seelischen in die menschliche Natur eintritt, diese Gedankenwelt wiederum zu beleben, diesen Leichnam der Gedanken, der Vorstellungen, zu einem Lebendigen zu machen. Das kann aber nur geschehen, wenn die Gedanken umgewandelt werden zunächst in Imaginationen, und wenn dann die Imaginationen zu Inspirationen und Intuitionen erhöht werden. Denn was gebraucht wird, ist volle Menschenerkenntnis. Nicht eher wird das, was ich gestern vor Sie hinstellte, in seinem Vollsinne begriffen werden: daß die Welt, wie sie um uns herum ist, eine große Frage, und der Mensch selbst die Antwort ist, was im tiefsten Sinne eben mit dem Mysterium von Golgatha hat gegeben werden sollen. Nicht eher wird das begriffen werden, als bis der Mensch wiederum begriffen werden kann.

[ 10 ] Setzen wir noch einmal rein schematisch diesen dreigliedrigen Menschen vor uns hin: Den Kopfmenschen oder Nerven-Sinnesmenschen in dem gestern wiederum besprochenen Sinne; den rhythmischen Menschen, den Brustmenschen und den Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenmenschen.

[ 11 ] Indem man heute den Menschen betrachtet, nimmt man ihn so, wie er einem als äußerliche Gestaltung entgegentritt. Wer heute im Seziersaal den Menschen auf den Seziertisch legt, der hat nicht ein tiefes Gefühl davon, indem er zum Beispiel den Kopf des Menschen untersucht, daß er etwas ganz anderes vor sich hat als wenn er, sagen wir einen Finger untersucht. Der Muskel des Fingers wird in derselben Weise beurteilt wie der Muskel des Kopfes. Aber man muß wissen, daß der Kopf des Menschen im wesentlichen eine metamorphosische Umgestaltung des Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselorganismus von der vorigen Inkarnation ist, daß der Kopf also in bezug auf seine Entwickelung etwas ganz anderes ist als der heutige Gliedmaßenmensch.

[ 12 ] Nun, wenn man sich einmal durchgerungen hat zu einer inneren Anschauung des dreigliedrigen Menschen, dann wird man auch wiederum zu einer Anschauung kommen können über das, was aus dem Kosmos heraus mit diesem dreigliedrigen Menschen zusammenhängt. Wir sind eigentlich als äußere menschliche Wesenheit nur durch unsere Kopforganisation dem Festen oder Irdischen einverleibt. Wir wären niemals ein Wesen, das als Festes, als Irdisches anzusprechen wäre, wenn wir nicht unsere Kopforganisation hätten, die aber ein Nachklang ist der Gliedmaßenorganisation von der vorigen Inkarnation. Daß wir auch feste Bestandteile in den Gliedmaßen, in den Händen, in den Füßen haben, das ist eine Ausstrahlung des Kopfes. Der Kopf ist dasjenige, was uns zum Festen macht. Alles, was fest in uns ist, was irdisch ist, das geht in seinem Kraftverhältnis vom Kopfe aus.

[ 13 ] Wir können sagen: Im Kopfe liegt das Feste, die Erde, in uns (siehe Zeichnung $. 130). Und alles das, was sonst fest in uns ist, das strahlt über den Menschen vom Kopfe hin. Im Kopfe liegt vorzugsweise der Ursprung der Knochen, der festen Knochenbildung. Aber in diesem Kopfe sehen wir auch schon.den Übergang zum Flüssigen. Alles das, was feste Bestandteile des Gehirnes sind, ist eingebettet im Gehirnwasser, und im Kopfe findet ein fortwährendes Durcheinandervibrieren der festen Gehirnbestandteile mit dem Gehirnwasser statt, das dann durch den Rückenmarkskanal mit dem übrigen Körper zusammenhängt. So daß wir sagen können: Wenn wir den Nerven-Sinnesmenschen in Betracht ziehen, ist da der Übergang von dem Irdischen (blau) zu dem Wässerigen, zu dem Flüssigen. Wir dürfen also sagen, der Nerven-Sinnesmensch lebt in dem erdig-wässerigen Elemente. Und eigentlich besteht unser Gehirn also, dem Organismus nach, in diesem Korrespondieren des Festen mit dem Flüssigen.

[ 14 ] Gehen wir dann über zu dem Brustorganismus, zu dem rhythmischen Organismus, so lebt dieser rhythmische Organismus in einem Tafel 11

[ 15 ] Wechselverhältnis zwischen dem Flüssigen und dem Luftförmigen (gelb). Sie sehen daher das Flüssige mit dem Luftförmigen in Berührung treten durch die Lunge. Sie sehen das rhythmische Leben als ein Durcheinanderweben des Flüssigen mit dem Luftförmigen, des Wassers mit der Luft. So daß ich sagen kann: Der rhythmische Mensch lebt im wässerig-luftförmigen Elemente.

[ 16 ] Und der Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenmensch, der lebt dann auf dem Übergang von dem luftförmigen Element in das Wärmeelement, in das feurige Element (rot). Er ist ein fortwährendes Auflösen des Luftförmigen in das Wärmeelement, in das feurige Element, das dann den ganzen Menschen durchsetzt als seine Körperwärme. In Wahrheit ist das, was im Stoffwechsel geschieht und was durch unsere Bewegungen geschieht, ein Herauforganisieren des luftförmigen Elementes, des gasförmigen Elementes in das Wärmeelement, in das feurige Element. Indem wir herumgehen, verbrennen wir fortwährend die luftförmig gewordenen Elemente unserer Nahrungsstoffe, und auch wenn wir nicht herumgehen im gewöhnlichen Leben des Menschen, geschieht es fortwährend, daß, indem die Nahrungsmittel bis zum Luftförmigen getrieben sind, sie verbrennen und in das Wärmeelement übergehen. So daß ich sagen kann, der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselmensch lebt im luftförmig-feurigen Elemente.

Nerven-Sinnesmensch: erdig-wässeriges Element

Rhythmischer Mensch: wässerig-luftförmig

Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselmensch: luftförmig-feurig.

[ 17 ] Dann geht es hinauf ins Ätherische, ins Lichtförmige, in die Ätherbestandteile des Menschen, in den ätherischen Leib. Wenn der Mensch durch seinen Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenorganismus alles in die Wärme übergeführt hat, dann geht es in den Ätherleib hinauf. Da schließt sich der Mensch zusammen mit dem Äther, der die ganze Welt ausfüllt, da gliedert er sich an den Kosmos an.

[ 18 ] Solche Vorstellungen, wie ich sie Ihnen hier schematisch entwickle, sie lassen sich durchaus, wenn der Mensch innerlich plastisch-musikalischen Sinn hat, ins Künstlerische, ins Poetische umgestalten. Und man könnte bei einer solchen Dichtung wie der Faust-Dichtung durchaus das, was man weiß, auch im künstlerischen Gestalten zum Ausdrucke bringen, wie gewisse kosmische Geheimnisse, sagen wir im siebenten Bilde meines ersten Mysteriums zur Darstellung gekommen sind. Da kommt man zu der Möglichkeit, den Menschen wiederum im Anschlusse an den Kosmos zu schauen. Aber dann darf man eben nicht das, was einem der Verstand über die äußere Natur gibt, auf den Menschen anwenden. Dann muß man sich klar sein: Studierst du die äußere Natur und dann den menschlichen Kopf geradeso wie die äußere Natur, dann studierst du etwas, was gar nicht herein gehört in diese äußere jetzige Natur, sondern was von der vorigen Inkarnation kommt. Das studierst du so, wie wenn es aus dem jetzigen Momente heraus entstanden wäre, aber es ist nicht aus dem jetzigen Momente heraus entstanden. Es könnte auch niemals aus einem jetzigen Momente heraus entstehen, denn aus den Naturkräften, die da sind, könnte niemals ein menschliches Haupt entstehen. Daher darf das menschliche Haupt nicht studiert werden nach gegenständlicher Erkenntnis, wie sie der Verstand gibt, sondern nach imaginativer Erkenntnis. Also, das menschliche Haupt wird man nicht früher erkennen, als bis man es nach imaginativer Erkenntnis studiert.

[ 19 ] Beim rhythmischen Menschen, da geht schon alles hinein ins Bewegte. Da haben Sie es mit dem flüssigen und dem luftförmigen Elemente zu tun. Der rhythmische Mensch ist ein Anfang zwischen dem wässerigen und dem luftförmigen Elemente. Da wogt alles. Und die äußeren festen Bestandteile in unserer Brust sind nur das, was der Kopf hineinstrahlt in dieses Wogen. Wollen wir also den rhythmischen Menschen studieren, so müssen wir sagen, in diesem rhythmischen Menschen wogen ineinander wässeriges Element und luftförmiges Element (siehe Zeichnung, grün, gelb). Und da hinein sendet dann das Haupt, der Kopf die Möglichkeit, daß feste Bestandteile, wie sie in der Lunge und so weiter sind, da drinnen vorhanden sein können (weiß). Dieses Wogen, das die wirkliche Gestaltung des rhythmischen Menschen ist, das läßt sich nur durch Inspiration studieren. So daß der rhythmische Mensch nur durch Inspiration studiert werden kann.

[ 20 ] Und der Gliedmaßen-Stoffwechselmensch — das ist das fortwährende Brennen der Luft in uns. Sie stehen darinnen, Sie fühlen sich in Ihrer Wärme als Mensch, aber das ist eine sehr dunkle Vorstellung. Im Ernste kann man das nur studieren durch Intuition, wo die Seele im Objekte darinnen steht. Nur Intuition kann zum Stoffwechsel-Gliedmaßenmenschen führen.

[ 21 ] Der Mensch wird immer ein Unbekanntes bleiben, wenn er nicht mit Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition studiert wird. Er wird immer dastehen vor dem Menschen als diese äußerliche Gestalt, die er für das heutige populäre und auch für das heutige wissenschaftliche Vorstellen ist. Dabei darf es nicht bleiben. Der Mensch muß wieder erkannt werden. Wenn Sie den Menschen nur in seinen festen Bestandteilen studieren, wenn Sie nur die Zeichnungen nehmen, die heute in den Anatomiebüchern stehen, dann studieren Sie es schon ohnedies nicht richtig, weil Sie es imaginativ studieren sollten, weil alle diese Zeichnungen, die man von den festen Bestandteilen des menschlichen Organismus macht, als Bilder vom vorigen Erdenleben genommen werden sollten. Schon das ist das erste. Aber was dann im feineren Menschen in den flüssigen Bestandteilen lebt, das kann erst durch Inspiration, und das andere, das Luft- und Wärmeförmige, erst durch Intuition studiert werden. Das sind die Dinge, die ins europäische Bewußtsein hineinkommen müssen, die in die ganze moderne Zivilisation hineinkommen müssen. Ohne daß wir dieses in die ganze moderne Zivilisation hineinbringen, kommen wir eben durchaus mit dieser Zivilisation nicht zu einem Aufbau, sondern nur zu einem Abbau.

[ 22 ] Wer Goethe versteht, wer versteht, was er in seinem «Faust» wollte, der fühlt schon, daß er eigentlich, ich möchte sagen durch ein gewisses Tor durch wollte. Überall ringt er mit der Frage: Wie steht es eigentlich mit diesem Menschen? - Als ganz junger Mensch hat Goethe angefangen, die menschliche Gestalt zu studieren. Lesen Sie seine Abhandlung vom Zwischenknochen und auch das, was ich darüber in meinen Ausgaben von den Naturwissenschaftlichen Schriften Goethes geschrieben habe; überall will er an den Menschen heran. Er versucht es zuerst auf anatomisch-physiologische Weise; dann versucht er es in den neunziger Jahren auf mehr moralische Weise durch Vorstellungen, die wir dann in dem «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie» finden. Und dann will er den Menschen, wie er in der Welt drinnensteht, schildern im «Faust». Er möchte durch ein Tor hindurch, um einzusehen, wie dieser Mensch in der Welt drinnensteht. Aber er hat nicht die Elemente dazu, er kann es nicht.

[ 23 ] Als Calderón seinen «Cyprianus» schrieb, da war das Ringen noch auf einer vorhergehenden Stufe. Da sehen wir, wie Justina sich dem Satan entreißt, wie dann Cyprianus wahnsinnig wird, wie sie sich im Tode finden, wie in dem Momente, als sie auf dem Schafott endigen, ihre Erlösung geschieht: Oben erscheint die Schlange mit dem darauf reitenden Dämon, der selber verkündigen muß, sie seien erlöst.

[ 24 ] Da sehen wir, wie in der Zeit, in der Calderón seinen «Cyprianus» geschrieben hat, deutlich gesagt werden soll: Hier im Erdenleben findet ihr das Göttlich-Geistige nicht. Ihr müßt erst sterben, ihr müßt erst durch den Tod gehen, dann findet ihr das Göttlich-Geistige, jene Erlösung, die ihr durch den Christus finden könnt. Da ist man noch weit davon entfernt, das Mysterium von Golgatha zu verstehen, durch das doch der Christus auf die Erde niedergestiegen ist; dort müßte er also auch zu finden sein. Es ist noch zuviel Heidnisches, zuviel Jüdisches in den Vorstellungen des Calderón, um das christliche Empfinden schon voll zu haben.

[ 25 ] Dann ist natürlich wiederum einige Zeit vergangen, bis Goethe an seinem «Faust» arbeitete. Goethe fühlt schon die Notwendigkeit: Faust muß hier auf der Erde seine Erlösung finden können. Goethe hätte die Frage so stellen müssen: Wie findet Faust die Bewahrheitung der Paulinischen Worte: «Nicht ich, sondern der Christus in mir»? Goethe hätte dazu kommen müssen, seinen Faust nicht nur sagen zu lassen: «Auf freiem Grund mit freiem Volk zu stehen», sondern: Auf freiem Grund, mit dem Christus in der Seele, den Menschen im Erdenleben zum Geiste führend. — So etwa müßte Goethe seinen Faust sagen lassen. Goethe ist natürlich ehrlich; er sagt es nicht, weil er es noch nicht voll erfaßt hat. Aber Goethe strebt nach diesem Erfassen. Goethe strebt nach etwas, was eigentlich erst erfüllt werden kann, wenn man sagt: Erkenne den Menschen durch Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition. — Daß das so ist, gibt demjenigen, der sich Goethe naht, das Gefühl, daß in Goethes Ringen, in Goethes Streben eigentlich viel mehr ist, als sich dann irgendwie ausgelebt hat, als dann in die moderne Zivilisation übergegangen ist. Man kann vielleicht Goethe nur erkennen, wenn man es so macht, wie ich es in meinen Jugendschriften gemacht habe, wo ich versuchte, dasjenige darzustellen, was gewissermaßen unbewußt als eine Weltanschauung in Goethe lebte. Aber es ist ja im Grunde genommen so gewesen, daß in der Gegenwart doch die Menschheit diesem Suchen wenig Verständnis entgegenbringt.

[ 26 ] Wenn ich auf dieses ganze Verhältnis hinschaue innerhalb der modernen Zivilisation, dann muß ich mich immer wieder erinnern an meinen alten Lehrer und Freund Karl Julius Schröer. Und namentlich daran, wie Schröer selber, als er in den achtziger Jahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts am «Faust» und an den andern Goetheschen Dramen arbeitete, Kommentare, Einleitungen gab, wie er eigentlich gar nicht darauf bedacht war, in streng umrissenen Begriffen über Goethe zu reden, sondern mehr in allgemeinen Vorstellungen, wie er aber versuchte, begreiflich zu machen, daß dasjenige, was als Tiefstes in Goethe lebte, doch hinein muß in die moderne Kultur. Schröer hat, als der fünfzigste Todestag Goethes war, 1882, eine Rede gehalten: «Die kommende Anschauung über Goethe.» Schröer lebte in dem Traum, daß dazumal schon die Zeit gekommen wäre, die Goethe zu einer Art von Auferstehung verhelfen würde. Und dann schrieb er einen kurzen Aufsatz in der «Neuen freien Presse», der wiederum abgedruckt ist in dem Büchelchen «Goethe und die Liebe», das jetzt unter andern Schröerschen Schriften von unserem Kommenden-Tag-Verlag erworben worden ist, so daß die Restexemplare dort zu haben sind und nach einiger Zeit wohl auch Neuauflagen werden besorgt werden können. Dieser Aufsatz «Goethe nach 50 Jahren» ist ein kurzer Auszug aus jenem Vortrag, den ich dazumal gehört habe. Er enthält manches von dem, was dazumal in Schröers Gefühlen lebte: Daß Goethe in die Zeitzivilisation hinein müsse. Und dann, als Schröer das Büchelchen schrieb «Goethe und die Liebe», da hatte er in den Anmerkungen zu zeigen versucht, wie man Goethe lebendig machen solle, denn Goethe lebendig machen, heißt ja in gewissem Sinne, die abstrakte Gedankenwelt selber lebendig machen. Ich habe in der letzten Nummer des «Goetheanum» hingewiesen auf eine solche Stelle, die wunderschön ist und die in dem Büchelchen «Goethe und die Liebe» steht. Da sagt Schröer: «Schiller erkannte ihn [Goethe nämlich]: Ist der intuitive Geist genialisch und sucht in dem Empirischen den Charakter der Notwendigkeit auf, so wird er zwar immer nur Individuen, aber mit dem Charakter der Gattung erzeugen. Goethe steht mit seiner intuitiven Methode, mit der er im vergänglichen Individuum die unvergängliche Idee, den Urtypus sieht, nicht so vereinzelt da, als man vielleicht annehmen möchte.»

[ 27 ] Gerade als Schröer dazumal, 1882, diese Stelle schrieb, war ich bei ihm; das heißt, während er an dem Büchelchen schrieb, kam ich öfter zu ihm, und er war dazumal ganz voll von einem Eindruck, den er bekommen hatte. Dieser Eindruck rührte davon her, daß er irgendwo wahrgenommen hatte, wie einer jener damals noch vorhandenen älteren Ärzte-Oppolzer war es nämlich, der Wiener Kliniker Oppolzer eine gewisse unbestimmte Intuition hatte bei der Diagnose. Wenn Oppolzer ans Krankenbett trat, dann machte er nicht die Differentialuntersuchungen, wie man sie sonst macht, sondern der Typus des Kranken machte auf ihn einen gewissen Eindruck, und aus dem Typus des Kranken heraus empfand er nun auch etwas von dem Typus der Krankheit. Das machte auf Schröer einen starken Eindruck, und aus diesem Eindruck heraus schrieb er dann die Stelle, die dieses Phänomen bei Oppolzer nur zur Erläuterung benützte. Er schrieb: «In der Heilkunst preist man an großen Diagnostikern am Krankenbette den Tiefblick, mit dem sie den Habitus, den individuellen Typus des Kranken und daraus dann die Krankheit erkennen. Nicht ihr chemikalisches oder anatomisches Wissen steht ihnen dabei zur Seite, sondern die Intuition in das Lebewesen als Ganzes. Sie sind schöpferische Geister, die die Sonne sehen, weil ihr Auge sonnenhaft ist. Andere sehen sie eben nicht. Folgt ein solcher Diagnostiker der intuitiven Methode Goethes unbewußt, Goethe hat sie mit Bewußtsein in die Wissenschaft eingeführt. Sie führte ihn zu Ergebnissen, die nicht mehr bestritten werden, nur die Methode ist noch nicht allseitig erkannt.»

[ 28 ] Das schrieb Schröer aus diesem Aperçu mit der Oppolzerschen Intuition am Krankenbett heraus, schon damals hindeutend darauf, daß also die einzelnen Wissenschaften, zum Beispiel die Heilkunde, von der Methode, die wiederum mit dem Geiste arbeitet, befruchtet werden müssen.

[ 29 ] Es hat etwas Tragisches, wenn ich zurückschaue, wie in Schröer einer der letzten von denjenigen Menschen vorhanden war, die noch etwas empfanden von dem Tiefsten in Goethe. Denn während Schröer dazumal, im Beginn der achtziger Jahre des vorigen Jahrhunderts, geglaubt hat, daß ein Wiederaufleben Goethes stattfinden müsse, hat man ja Goethe nachher erst recht eingesargt, erst richtig begraben. Man könnte auch sagen: Das richtige Grab Goethes, das ist für Mitrteleuropa gewesen die Goethe-Gesellschaft, und auf englisch heißt sie Goethe-Society, denn sie wurde dort auch als ein Ableger begründet. Das war die Grabstätte des lebenden Goethe. Aber die Notwendigkeit besteht doch, dieses lebendige Element, das in Goethe lebte, wiederum in unsere Zivilisation hineinzubringen. Karl Julius Schröers Trieb war ein guter; er konnte sich nur dazumal nicht erfüllen, weil die Zeit weiterging in der Anbetung des Toten. «Wer will was Lebendigs erkennen und beschreiben, sucht erst den Geist herauszutreiben.»

[ 30 ] Das ist, was eben die Devise wurde, und heute ist in manchen sehr weiten Kreisen diese Devise bis zum Haß gegen alles Vernehmen vom Geistigen gegeben - wie Sie ja aus der Aufnahme der Anthroposophie bei vielen Menschen ersehen können.

[ 31 ] Die Zivilisation, aus der Sie selber alle noch herausgewachsen sind, braucht durchaus dieses Element einer Wiederbelebung. Und es ist nur merkwürdig, wie heute vieles geredet wird zum Beispiel über den Goetheschen «Faust» — der ja nur ein neues Moment in jenem Ringen nach dem Geist darstellt, das wir im Calderónschen «Cyprianus» gestern gesehen haben -, wie aber nicht gesehen wird, daß es Aufgabe der Gegenwart ist, zur vollen Lebendigkeit dasjenige herauszustellen, was Goethe eigentlich hat leben lassen, unbestimmt andeutend, gefühls- und empfindungsmäßig, aber nicht in geistiger Anschauung, in seinem «Faust», insbesondere im zweiten Teil. Wir müßten auf diese Erscheinungen in ganz intensiver Weise unsere Aufmerksamkeit richten, denn wir haben es da wirklich nicht bloß mit einer Weltanschauungsangelegenheit zu tun, wir haben es schon mit einer allgemeinen Zivilisationsangelegenheit zu tun. Dafür gibt es viele Symptome der Gegenwart. Diese Symptome müssen nur im richtigen Lichte gesehen werden.

[ 32 ] Da ist eine Schrift erschienen, welche «Die drei Krisen» heißt, von Ruedorffer, eine Schrift, die einen, wenn man sie liest, ich möchte sagen auf jeder Seite sticht. Denn der, der sie geschrieben hat, ist eine Persönlichkeit, die selber im diplomatisch-politischen Leben Europas in ganz wichtigen Stellungen mitgewirkt hat, vor dem Kriege und in den Krieg hinein. Der Mann sucht sich jetzt, nachdem er alle möglichen Wege dieses europäischen Lebens kennengelernt hat - eben von Auslugen aus, von denen aus man es genauer kennenlernen kann als die meisten Menschen -, er sucht sich jetzt klarzuwerden darüber, was eigentlich ist. Ich brauche Ihnen nur ein paar Stellen vorzulesen aus der Schrift eines Menschen, der durchaus ein Realist, nicht ein Idealist sein will, der sich einen gewissen trockenen Blick angeeignet hat innerhalb seiner diplomatischen Laufbahn und bei dem es, trotzdem er solche Stellen niedergeschrieben hat, wie ich sie Ihnen vorlesen werde, doch so ist, daß man sagen kann: Der Zopf, der hängt ihm hinten. Er ist trotzdem geblieben, was man heute insbesondere liebt, der bürgerliche Philister.

[ 33 ] Er spricht von drei Dingen in dieser seiner Schrift. Er spricht erstens davon, wie die Staaten und Völker Europas kein Verhältnis mehr zueinander haben. Dann spricht er davon, wie die einzelnen regierenden Kreise, die Führer innerhalb der einzelnen Völkerschaften, wiederum zum Volke selbst kein Verhältnis haben. Und drittens spricht er davon, wie namentlich diejenigen Menschen, die heute in radikaler Art eine neue Zeit herausarbeiten und begründen wollen, erst recht kein Verhältnis zur Realität haben.

[ 34 ] Also ein Mensch, der mitgearbeitet hat, wie gesagt, an den Zuständen, die heute geworden sind, der schreibt etwa so: «Diese Erkrankung des staatlichen Organismus entreißt der Vernunft die Führung, überantwortet die Entschließungen des Staats mannigfachen unsachlichen Nebeneinflüssen und Nebenrücksichten. Sie beschränkt die Bewegungsfreiheit, zersplittert den staatlichen Willen und hat überdies zumeist noch eine gefährliche Labilität der Regierungen im Gefolge. Die Zeit des ungebärdigen Nationalismus vor dem Kriege, der Krieg selbst, der europäische Zustand nach dem Kriege haben ungeheure Anforderungen an die Vernunft der Staaten, ihre Ruhe und Bewegungsfreiheit gestellt. Daß mit den Aufgaben das Vermögen nicht wuchs, sondern abnahm, hat die Katastrophe vollendet. Die Krise des Staates und die Krise der Weltorganisation haben in steter Wechselwirkung einander befördert und eine jede die destruktiven Wirkungen der anderen vermehrt.» So spricht nicht irgendein Idealist, nicht irgendein künstlerischer Mensch, der bloß zugeschaut hat, sondern einer, der mitgetan hat. Er sagt zum Beispiel: «Wenn die Demokratie bestehen soll, muß sie ehrlich und mutig genug sein, zu sagen, was ist, auch wenn sie gegen sich selbst zu zeugen scheint. Europa steht vor dem Untergang.»

[ 35 ] Daß wir vor dem Untergange Europas stehen, das sagen heute nicht bloß die pessimistisch angehauchten Idealisten, sondern das sagen insbesondere diejenigen, die in der Praxis drinnengestanden haben. Jemand, der, wie gesagt, darinnengestanden hat und mitgetan hat, schreibt heute eben den Satz hin: «Europa steht vor dem Untergang. Da ist keine Zeit, daß ein jeder aus parteitaktischen Gründen seine Fehler verbirgt, statt sie zu bessern. Nur zu diesem Behufe, nicht als laudator temporis acti unterstreiche ich, daß die Demokratie sich selbst zerstören muß und wird, wenn sie nicht den Staat aus dieser Verstrickung von Nebeneinflüssen und Nebenrücksichten befreien kann. Das vorkriegerische Europa ist zusammengebrochen, weil alle kontinentalen Staaten, und zwar die Monarchien ebenso wie die Demokratien und am meisten das autokratische Rußland, teils freiwillig und unbewußst, teils unwillig und gezwungen sich der Demagogie unterworfen haben, unfähig, in der selbstgeschaffenen Verirrung der Geister das Vernünftige zu erkennen und das etwa doch Erkannte frei und entschieden zu tun. Die Oberschichten der alten Staatsordnung Europas, im vergangenen Jahrhundert freilich Träger der europäischen Bildung und reich an Persönlichkeiten von staatsmännischem Geist und Welterfahrung, wären nicht so leicht aus dem Sattel und als morsch und verbraucht beiseite geworfen worden, wenn sie, mit den Problemen und Aufgaben der verwandelten Zeit mitgewachsen, nicht des staatsmännischen Geistes verlustig gegangen wären und eine andere Tradition als die der äußerlichsten diplomatischen Routine bewahrt hätten. Wenn die Monarchen den Anspruch erheben, Staatsmänner besser und sachlicher auszuwählen als Parlamente, dann müssen sie und ihre Höfe Mittelpunkt und Höhepunkt der Bildung, Einsicht und Kenntnis sein. Das aber war lange vor dem Kriege vorbei. Aber die Anklage gegen die Fehler der Monarchie entbindet die Demokratie nicht, die Ursachen ihrer eigenen Unzulänglichkeit zu erkennen und alles zu tun, um sie zu beheben. Ehe Europa gesunden, ehe versucht werden kann, seine heillose Desorganisation durch einen haltbareren politischen Bau zu ersetzen, müssen die einzelnen Länder ihre inneren Dinge dergestalt ordnen, daß ihre Regierungen zu sachlich freier Arbeit auf lange Sicht befähigt werden. Sonst erlahmt der beste Wille und die größte Begabung, tausendfach umstrickt, in dem allerorten gleichen Verhängnis.» Ich würde Ihnen das alles nicht vorlesen, wenn es von einem Idealisten herrührte, wenn es nicht von jemandem herrührte, der da glauben muß, ganz im Realen drinnenzustehen, weil er eben mitgetan hat.

[ 36 ] «Es ist ein Schauspiel von tiefer TIragik, wie jeder Versuch einer bessernden Handlung, jedes Wort der Umkehr sich in den Netzen dieses Verhängnisses fängt und, hundertfach umstrickt, schließlich wirkungslos zu Boden fällt; wie das europäische Bürgertum, gedankenlos an dem Zeitirrtum des steten Fortschritts der Menschheit hangend oder die gewohnte Bahn jammernd weitertrottend, nicht sieht und sehen will, daß es von der aufgespeicherten Arbeit früherer Jahre zehrt und kaum fähig ist, die Schäden der jetzigen Weltordnung zu erkennen, geschweige denn, aus sich heraus eine neue zu gebären; wie auf der anderen Seite die Arbeiterschaft, sich in nahezu allen Ländern radikalisierend, von der Unhaltbarkeit des gegenwärtigen Zustandes überzeugt, sich Heilbringer einer neuen Ordnung glaubt, in Wirklichkeit aber in diesem Glauben nur unbewußtes Werkzeug der Zerstörung und des Untergangs, auch des eigenen, ist. Die neuen Parasiten der wirtschaftlichen Desorganisation, der klagende Reichtum von gestern, der zum Proletarier herabsinkende Kleinbürger, der gläubige Arbeiter, der eine neue Welt zu begründen wähnt, sie alle scheint dasselbe Verhängnis zu umschlingen, sie alle scheinen Erblindete, die ihre eigenen Gräber schaufeln.» Das steht nicht in dem Buch eines Idealisten, das steht eben heute in dem Buch eines [Menschen], der mitgearbeitet hat! «Aber der ganze Aspekt des heutigen politischen Wesens, die neueren Friedensschlüsse der Entente, der polnische Vormarsch in die Ukraine, die Blindheit oder Hilflosigkeit der Entente gegenüber der deutsch-österreichischen Entwicklung, zeigt dem nun einmal auf Realitäten angewiesenen Politiker, daß die ideale Forderung einer paneuropäischen, konstruktiven Revision der Pariser Friedensschlüsse zwar gestellt, die dringendste Warnung erschütternd begründet, Forderung und Warnung aber nur unbeachtet verhallen können und die Dinge im alten Sinne zwangsläufig weiterrollen dem Abgrund zu.»

[ 37 ] Das ganze Buch ist geschrieben, um zu beweisen, daß Europa vor dem Abgrunde steht, daß wir daran sind, das Grab der europäischen Zivilisation zu schaufeln. Aber das alles möchte ich Ihnen nur als eine Introduktion sagen zu dem, was ich nun eigentlich für notwendig halte zu sagen. Das ist nämlich etwas anderes. Wir haben da einen Menschen vor uns, der in den entscheidenden Büros selber gesessen hat, der da sieht, daß Europa am Abgrunde steht, und der einfach sagt — das geht aus dieser ganzen Schrift hervor: Wenn nichts anderes geschieht, als was die Fortsetzung der alten Impulse ist, dann geht die Zivilisation unter; unbedingt geht sie unter. Es muß etwas Neues kommen.

[ 38 ] Nun, ich suche nun, wo in einer solchen Schrift auf das Neue hingedeutet worden ist. Ja, ich finde es auf Seite 67, da stehen drei Zeilen: «Nur eine Sinnesänderung der Welt, eine Willensänderung der beteiligten Hauptmächte kann einen obersten Rat der europäischen Vernunft entstehen lassen.»

[ 39 ] Ja, Sie sehen, vor dieser Entscheidung stehen die Menschen. Sie weisen darauf hin, nur wenn überall eine Sinnesänderung entsteht, wenn etwas ganz Neues kommt, dann gibt es noch eine Rettung. Das ganze Buch ist geschrieben zu dem Zwecke, um zu zeigen, daß es sonst keine Rettung gibt. Es ist viel Richtiges daran. Die Wahrheit ist nämlich, daß es für die zusammenbrechende Zivilisation aus nichts weiter heraus eine Rettung gibt als aus dem Geistesleben, das aus den wirklichen geistigen Quellen geschöpft wird. Es gibt keine andere Rettung, sonst geht eben die moderne Zivilisation, insofern sie von Europa aus bis nach Amerika begründet worden ist, ihrem Untergange entgegen. In dem, was verfault, muß gesehen werden die wichtigste Zeiterscheinung der Gegenwart. Und es hilft nichts, Kompromisse zu schließen mit dem Verfaulenden, sondern es hilft allein, auf dasjenige zu sehen, was auch über dem Grabe gedeihen kann, weil es eben stärker ist als der Tod. Das ist das Geistesleben. Aber für das, was da notwendig ist, haben solche Leute zunächst nur die ganz abstrakte Hindeutung: Es muß eben eine allgemeine internationale Sinnesänderung entstehen. — Hören sie irgendwo etwas von wirklichem Aufblühen von geistigem Leben, dann ist es «unbrauchbare Mystik». Dann kommen sie und sagen: Ja, in solchen sinkenden Zeiten des Unterganges, da machen sich alle möglichen Okkultismen und Mystiken geltend, und da muß man sich hüten davor.

[ 40 ] Und so schaufeln an dem Grabe der heutigen Zivilisation am meisten diejenigen, die sogar einsehen, daß dieses Schaufeln geschieht. Es ist nicht anders möglich, zu diesen Dingen Stellung zu nehmen, als indem man sie mit vollem Ernst einsieht, indem man sich mit vollem Ernst wirklich versenkt in die Wahrheit, daß ein neues Geistesleben notwendig ist und daß dieses neue Geistesleben wirklich gesucht werden muß, so daß endlich die Möglichkeit gefunden werde, innerhalb des irdischen Lebens den Christus zu finden, ihn so zu finden, wie er ist seit dem Mysterium von Golgatha. Denn er ist heruntergestiegen, um sich mit den Erdenverhältnissen zu verbinden.

[ 41 ] Den stärksten Kampf gegen diese eigentlich christliche Wahrheit führt heute zum Beispiel eine gewisse Sorte von Theologie, die gerade dann sich aufbäumt, wenn man von dem kosmischen Christus spricht. So daß immer wieder und wieder darauf aufmerksam gemacht werden muß, daß auch schon in den Zeiten, in denen zum Beispiel Schröer auf Goethe hingewiesen hat zur Wiederbelebung der Zivilisation, schon dazumal das Buch von dem Basler Professor, dem Freunde Nietzsches, erschienen ist über die Christlichkeit der neueren Theologie - er meinte die christliche Theologie. Und Overbeck meinte dazumal, daß gerade die Theologie das Unchristlichste ist und suchte das als Historiker der Theologie zu beweisen. Damals war also in Basel die historisch-theologische Lehrkanzel mit einem Professor besetzt, der den Beweis führte: Die Theologie ist unchristlich!

[ 42 ] Die Menschheit hat in die Katastrophe hineintreiben müssen, weil sie die einzelnen Rufe, die da waren, die allerdings noch sehr an Unklarheit litten, nicht aufgenommen hat. Heute hat die Menschheit keine Zeit mehr, zu warten. Heute muß die Menschheit wissen, daß solche Darstellungen wie die von Ruedorffer durchaus wahr sind, daß es durchaus notwendig ist, einzusehen, wie durch die Fortsetzung der alten Impulse alles zusammensinkt. Dann gibt es nur eines: Sich an dasjenige zu wenden, was auch aus Gräbern wachsen kann, nämlich das Geistig-Lebendige.

[ 43 ] Und das ist es, worauf immer wieder und wiederum aufmerksam gemacht werden muß, gerade in unserem Zusammenhange, meine lieben Freunde. Davon werden wir dann am nächsten Freitag um 8 Uhr weiterreden.

The Connection between Humans and the Cosmos