Old and New Methods of Initiation

GA 210

24 February 1922, Dornach

Lecture XI

The turning-point, between the fourth and fifth post-Atlantean periods,1 Lecture Three, Note 1 which falls in the fifteenth century, is very much more significant for human evolution than is recognized by external history, even today. There is no awareness of the tremendous change which took place at that time in the condition of human souls. We can say that profound traces of what took place at that time for mankind as a whole became deeply embedded in the consciousness of the best spirits. These traces remained for a long time and are indeed still there today. That something so important can take place without at first being much noticed externally is shown by another example—that of Christianity itself.

During the course of almost two thousand years, Christianity has wrought tremendous transformation on the civilized world. Yet, a century after the Mystery of Golgotha, it meant little, even to the greatest spirits of the leading culture of the time—that of Rome. It was still seen as a minor event of little significance that had taken place out there in Asia, on the periphery of the Empire. Similarly, what took place in the civilized world around the first third of the fifteenth century has been little noted in external, recorded history. Yet it has left deep traces in human striving and endeavour.

We spoke about some aspects recently. For instance, we saw that Calderón's2 Lecture Nine, Note 2 drama about the magician Cyprianus shows how this spiritual change was experienced in Spain. Now it is becoming obvious—though it is not expressed in the way Anthroposophy has to express it—that in all sorts of places at this point in human evolution there is a more vital sense for the need to gain greater clarity of soul about this change. I have also pointed out that Goethe's Faust is one of the endeavours, one of the human struggles, to gain clarity about it. More light can perhaps be thrown on this Faust of Goethe when it is seen in a wider cultural context. But first let us look at Faust himself as an isolated individual.

First of all in his youthful endeavours, stimulated of course by the cultural situation in Europe at that time, Goethe came to depict in dramatic form the striving of human beings in the newly dawning age of the intellect. From the way in which he came across the medieval Faust figure in a popular play or something similar, he came to see him as a representative of all those seeking personalities who lived at that time. Faust belongs to the sixteenth, not the fifteenth century,3 The first mention of Faust appeared in 1506. In 1587 the first Faustbuch, a popular chapbook, was published in Frankfurt-am-Main. but of course the spiritual change did not take place in the space of only a year or even a century. It came about gradually over centuries. So the Faust figure came towards Goethe like a personality living in the midst of this seeking and striving that had come from earlier times and would go on into later centuries. We can see that the special nature of this seeking and striving, as it changed from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period, is perfectly clear to Goethe. First he presents Faust as the scholar who is familiar with all four academic faculties. All four faculties have worked on his soul, so that he has taken into his soul the impulses which derive from intellectualism, from intellectualistic science. At the same time he senses how unsatisfying it is for human beings to remain stuck in one-sided intellectualism. As you know, Faust turns away from this intellectualism and, in his own way, towards the practice of magic. Let us be clear about what is meant in this case. What he has gone through by way of ‘Philosophy and Jurisprudence, Medicine and even, alas, Theology,’4 Faust Part One. The Study. is what anyone can go through by studying the intellectualized sciences. It leaves a feeling of dissatisfaction. It leaves behind this feeling of dissatisfaction because anything abstract—and abstraction is the language of these sciences—makes demands only on a part of the human being, the head part, while all the rest is left out of account.

Compare this with what it was like in earlier times. The fact that things were different in earlier times is habitually overlooked. In those earlier times the people who wanted to push forward to a knowledge of life and the world did not turn to intellectual concepts. All their efforts were concentrated on seeing spiritual realities, spiritual beings, behind the sense-perceptible objects of their environment. This is what people find so difficult to understand. In the tenth, eleventh, twelfth centuries those who strove for knowledge did not only seek intellectual concepts, they sought spiritual beings and realities, in accordance with what can be perceived behind sense-perceptible phenomena and not in accordance with what can be merely thought about sense-perceptible phenomena.

This is what constitutes that great spiritual change. What people sought in earlier times was banished to the realm of superstition, and the inclination to seek for real spiritual beings was lost. Instead, intellectual concepts came to be the only acceptable thing, the only really scientific knowledge. But no matter how logically people told themselves that the only concepts and ideas free of any superstition are those which the intellect forms on the basis of sense-perceptible reality, nevertheless these concepts and ideas failed, in the long run, to satisfy the human being as a whole, and especially the human heart and soul. In this way Goethe's Faust finds himself to be so dissatisfied with the intellectual knowledge he possesses that he turns back to what he remembers of the realm of magic.

This was a true and genuine mood of soul in Goethe. He, too, had explored the sciences at the University of Leipzig. Turning away from the intellectualism he met in Leipzig, he started to explore what in Faust he later called ‘magic’, for instance, together with Susanne von Klettenberg and also by studying the relevant books. Not until he met Herder5 Johann Gottfried Herder, 1744-1803. Called Kant's system ‘a kingdom of never-ending whims, blind alleys, fancies, chimeras and vacant expressions.’ in Strasbourg did he discover a real deepening of vision. In him he found a spirit who was equally averse to intellectualism. Herder was certainly not an intellectual; hence his anti-Kant attitude. He led Goethe beyond what—in a genuinely Faustian mood—he had been endeavouring to discover in connection with ancient magic.

Thus Goethe looked at this Faust of the sixteenth century, or rather at that scholar of the fifteenth century who was growing beyond magic, even though he was still half-immersed in it. Goethe wanted to depict his own deepest inner search, a search which was in him because the traces of the spiritual change from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period were still working in him.

It is one of the most interesting phenomena of recent cultural evolution that Goethe, who wanted to give expression to his own youthful striving, should turn to that professor from the fifteenth and sixteenth century. In the figure of this professor he depicted his own inner soul life and experience. Du Bois-Reymond,6 Emil Du Bois-Reymond, 1818-1896: In ‘Goethe und kein Ende’ (No end to Goethe), address of 15 October 1882 in Reden (Speeches), Leipzig 1886. of course, totally misunderstood both what lived in Goethe and what lived in the great change that took place in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when he said: Goethe made a big mistake in depicting Faust as he did; he should have done it quite differently. It is right that Faust should be dissatisfied with what tradition had to offer him; but if Goethe had depicted him properly he would have shown, after the early scenes, how he first made an honest woman of Gretchen by marrying her, and then became a well-known professor who went on to invent the electro-static machine and the air pump. This is what Du Bois-Reymond thought should have become of Faust.

Well, Goethe did not let this happen to Faust, and I am not sure whether it would have been any more interesting if he had done what Du Bois-Reymond thought he should have done. But as it is, Goethe's Faust is one of the most interesting phenomena of recent cultural history because Goethe felt the urge to let this professor from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries stand as the representative of what still vibrated in his own being as an echo of that spiritual change which came about during the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period.

The sixteenth century Faust—that is the legendary Faust, not the one who ought to have become the inventor of the electro-static machine and the air pump—takes up magic and perishes, goes to the devil. We know that this sixteenth century Faust could not be seen by either Lessing or Goethe as the Faust of the eighteenth century. Now it was necessary to endeavour to show that once again there was a striving for the spirit and that man ought to find his way to salvation, if I may use this expression.

Here, to begin with, is Faust, the professor in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Goethe has depicted him strikingly well, for this is just what such personalities were like at the universities of that time. Of course, the Faust of legend would not have been suitable, for he would have been more like a roaming vagabond gipsy. Goethe is describing not the legendary Faust but the figure of a professor. Of course, at the profoundest soul level he is an individual, a unique personality. But Goethe does also depict him as a type, as a typical professor of philosophy, or perhaps of medicine, of the fourteenth or fifteenth century. On the one hand he stands in the midst of the culture of his day, occupying himself with the intellectual sciences, but on the other he is not unfamiliar with occult things, which in Goethe's own day were considered nothing more than superstition.

Let us now look at Goethe's Faust in a wider world context. We do make the acquaintance of his famulus and Goethe shows us the relationship between the two. We also meet a student—though judging by his later development he does not seem to have been much influenced by his professor. But apart from this, Goethe does not show us much of the real influence exercised by Faust, in his deeper soul aspects, as he might have taught as a professor in, say, Wittenberg. However, there does exist a pupil of Faust who can lead us more profoundly into this wider world context. There is a pupil of Faust who occupies a place in the cultural history of mankind which is almost equal to that of Professor Faust himself—I am speaking only of Faust as Goethe portrayed him. And this pupil is none other than Hamlet.

Hamlet can indeed be seen as a genuine pupil of Faust. It is not a question of the historical aspect of Faust as depicted by Goethe. The whole action of the drama shows that although the cultural attitudes are those of the eighteenth century, nevertheless Goethe's endeavour was to place Faust in an earlier age. But from a certain point of view it is definitely possible to say: Hamlet, who has studied at Wittenberg and has brought home with him a certain mood of spirit—Hamlet as depicted by Shakespeare,7 William Shakespeare, 1564-1616. Hamlet is one of his later plays. can be seen in the context of world spiritual history as a pupil of Faust. It may even be true to say that Hamlet is a far more genuine pupil of Faust than are the students depicted in Goethe's drama.

Consider the whole character of Hamlet and combine this with the fact that he studied in Wittenberg where he could easily have heard a professor such as Faust. Consider the manner in which he is given his task. His father's ghost appears to him. He is in contact with the real spiritual world. He is really within it. But he has studied in Wittenberg where he was such a good student that he has come to regard the human brain as a book. You remember the scene when Hamlet speaks of the ‘book and volume’ of his brain.8 Hamlet, Act One, Scene 5. He has studied human sciences so thoroughly that he speaks of writing what he wants to remember on the table of his memory, almost as though he had known the phrase which Goethe would use later when composing his Faust drama: ‘For what one has, in black and white, one carries home and then goes through it.’9 ‘what one has in black and white’: Faust Part One, The Study. Hamlet is on the one hand an excellent student of the intellectualism taught him at Wittenberg, but on the other hand he is immersed in a spiritual reality. Both impulses work in his soul. The whole of the Hamlet drama stands under the influence of these two impulses. Hamlet—both the drama and the character—stands under the influence of these impulses because, when it comes down to it, the writer of Hamlet does not really know how to combine the spiritual world with the intellectual mood of soul. Poetic works which contain characteristics that are so deeply rooted in life provide rich opportunities for discussion. That is why so many books are written about such works, books which do not really make much sense because there is no need for them to make sense. The commentators are constantly concerned with what they consider to be a most important question: Is the ghost in Hamlet merely a picture, or does it have objective significance? What can be concluded from the fact that only Hamlet, and not the others characters present on the stage, can see the ghost? Think of all the learned and interesting things that have been written about this! But of course none of it is connected with what concerned the poet who wrote Hamlet. He belonged to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. And writing out of the life of that time he could do no other than approach these things in a way which cannot be fixed in abstract concepts. That is why I say that it is not necessary to make any sense of all the various commentaries. We are talking about a time of transition. Earlier, it was quite clear that spiritual beings were as real as tables and chairs, or as a dog or a cat. Although Calderon lived even later than Shakespeare, he still held to this older view. It would not have occurred to him even to hint that the spiritual beings in his works might be merely subjective in character. Because his whole soul was still open to spiritual insight, he portrayed anything spiritual as something just as concrete as dogs and cats.

Shakespeare, whose mood of soul belonged fully to the time of transition, did not feel the need to handle the matter in any other way than that which stated: It might be like this or it might be like that. There is no longer a clear distinction between whether the spiritual beings are subjective or objective. This is a question which is just as irrelevant for a higher world view as it would be to ask in real life—not in astronomy, of course—where to draw the line between day and night. The question as to whether one is subjective and the other objective becomes irrelevant as soon as we recognize the objectivity of the inner world of man and the subjectivity of the external world. In Hamlet and also, say, in Macbeth, Shakespeare maintains a living suspension between the two. So we see that Shakespeare's dramas are drawn from the transition between the fourth and fifth post-Atlantean periods.

The expression of this is clearest in Hamlet. It may not be historical but it is none the less true to suggest that perhaps Hamlet was at Wittenberg just at the time when Faust was lecturing not so much about the occult as about the intellectual sciences—from what we said earlier you now know what I mean. Perhaps he was at Wittenberg before Faust admitted to himself that, ‘straight or crosswise, wrong or right’, he had been leading his scholars by the nose these ten years long. Perhaps Hamlet had been at Wittenberg during those very ten years, among those whom Faust had been leading by the nose. We can be sure that during those ten years Faust was not sure of where he stood. So having taken all this in from a soul that was itself uncertain, Hamlet returns and is faced on the one hand with what remains from an earlier age and what he himself can still perceive, and on the other with a human attitude which simply drives the spirits away. Just as ghosts flee before the light, so does the perception of spiritual beings flee before intellectualism. Spiritual vision cannot tolerate intellectualism because the outcome of it is a mood of soul in which the human being is inwardly torn right away from any connection with the spirit. The pallor of thoughts makes him ill in his inner being, and the consequence of this is the soul mood characteristic of the time from the eleventh to the fifteenth centuries and on into even later times. Goethe, who was sensitive to all these things, also had a mood of soul that reached back into this period. We ought to be clear about this.

Take Greek drama. It is unthinkable without the spiritual beings who stand behind it. It is they who determine human destinies. Human beings are woven into the fabric of destiny by the spiritual forces. This fabric brings into ordinary life what human beings would otherwise only experience if they were able consciously to go into the state of sleep. The will impulses which human beings sleep through in their daytime consciousness are brought into ordinary life. Greek destiny is an insight into what man otherwise sleeps through. When the ancient Greek brings his will to bear, when he acts, he is aware that this is not only the working of his daytime consciousness with its insipid thoughts. Because his whole being is at work, he knows that what pulses through him when he sleeps is also at work. And out of this awareness he gains a certain definite attitude to the question of death, the question of immortality.

Now we come to the period I have been describing, in which human beings no longer had any awareness that something spiritual played in—also in their will—while they slept. We come to the period in which human beings thought their sleep was their own, though at the same time they knew from tradition that they have some connection with the spiritual world. Abstract concepts such as ‘Philosophy, Jurisprudence, Medicine, and even, alas! Theology’ begin to take on a shadowy outline of what they will become in modern times. They begin to appear, but at the same time the earlier vision still plays in. This brings about a twilight consciousness. People really did live in this twilight consciousness. Such figures as Faust are, indeed, born out of a twilight consciousness, out of a glance into the spiritual world which resembles a looking over one's shoulder in a dream. Think of the mood behind such words as ‘sleep’, or ‘dream’, in Hamlet. We can well say that when Hamlet speaks his monologues he is simply speaking about what he senses to be the riddle of his age; he is speaking not theoretically but out of what he actually senses.

So, spanning the centuries and yet connected in spirit, we see that Shakespeare depicts the student and Goethe the professor. Goethe depicted the professor simply because a few more centuries had passed and it was therefore necessary in his time to go further back to the source of what it was all about. Something lived in the consciousness of human beings, something that made the outstanding spirits say: I must bring to expression this state of transition that exists in human evolution.

It is extremely interesting to expand on this world situation still further, because out of it there arise a multitude of all-embracing questions and riddles about life and the world. It is interesting to note, for instance, that amongst the works of Shakespeare Hamlet is the one which depicts in its purest form a personality belonging to the whole twilight condition of the transition—especially in the monologues. The way Hamlet was understood in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries could have led to the question: Where was the stimulus for what exists in Hamlet's soul? The answer points to Wittenberg, the Faust source. Similar questions arise in connection with Macbeth. But in King Lear we move into the human realm. The question of the spiritual world is not so much concerned with the earth as with the human being—it enters into the human being and becomes a subjective state of mind which leads to madness.

Then Shakespeare's other dramas could also be considered. We could say: What the poet learnt by taking these human characters and leading them to the spiritual realm lives on in the historical dramas about the kings. He does not follow this specific theme in the historical dramas, but the indeterminate forces work on. Taking Shakespeare's dramas all together, one gains the impression that they all culminate in the age of Queen Elizabeth. Shakespeare wanted to depict something that leads from the subconscious, bubbling forces of his people to the intellectual clarity that has especially shone forth from that corner of the civilized world since the age of Elizabeth. From this point of view the whole world of Shakespeare's dramas appears—not perhaps quite like a play with a satisfactory ending, but at least like a drama which does lead to a fairly satisfying conclusion. That is, it leads to a world which then continues to evolve. After the transition had been going on for some time, the dramas lead toShakespeare's immediate present, which is a world with which it is possible to come to terms. This is the remarkable thing: The world of Shakespeare's dramas culminates in the age in which Shakespeare lived; this is an age with which it is possible to come to terms, because from then on history takes a satisfactory course and runs on into intellectualism. Intellectualism came from the part of the earth out of which Shakespeare wrote; and he depicted this by ending up at this point.

The questions with which I am concerned find their answers when we follow the lines which lead from the pupil Hamlet to the professor Faust, and then ask how it was with Goethe at the time when, out of his inner struggles, he came to the figure of Faust. You see, he also wrote Götz von Berlichingen. In Götz von Berlichingen, again taken from folk myth, there is a similar confrontation. On the one side you have the old forces of the pre-intellectual age, the old German empire, which cannot be compared with what became the later German empire. You have the knights and the peasants belonging to the pre-intellectual age when the pallor of thoughts did not make human beings ill; when indeed very little was guided from the head, but when the hands were used to such an extent that even an iron hand was needed. Goethe refers back to something that once lived in more recent civilization but which, by its very nature, had its roots in the fourth post-Atlantean period. Over against all this you have in the figure of Weislingen the new element which is developing, the age of intellectualism, which is intimately linked to the way the German princes and their principalities evolved, a development which led eventually to the later situation in Central Europe right up to the present catastrophe.

We see that in Götz von Berlichingen Goethe is attacking this system of princes and looking back to times which preceded the age of intellectualism. He takes the side of the old and rebels against what has taken its place, especially in Central Europe. It is as though Goethe were saying in Götz von Berlichingen that intellectualism has seized hold of Central Europe too. But here it appears as something that is out of place. It would not have occurred to Goethe to negate Shakespeare. We know how positive was Goethe's attitude to Shakespeare. It would not have occurred to him to find fault with Shakespeare, because his work led to a satisfying culmination which could be allowed to stand. On the contrary, he found this extraordinarily satisfying.

But the way in which intellectualism developed in his own environment made Goethe depict its existence as something unjustified, whereas he spiritually embraced the political element of what was expressed in the French Revolution. In Götz von Berlichingen Goethe is the spiritual revolutionary who denies the spirit in the same way as the French Revolution denies the political element. Goethe turns back in a certain way to something that has once been, though he certainly cannot wish that it should return in its old form. He wants it to develop in a different direction. It is most interesting to observe this mood in Goethe, this mood of revolt against what has come to replace the world of Götz.

So it is extremely interesting to find that Shakespeare has been so deeply grasped by Lessing and by Goethe and that they really followed on from Shakespeare in seeking what they wanted to find through their mood of spiritual revolt. Yet where intellectualism has become particularly deeply entrenched, for instance in Voltaire,10Francois-Marie Arouet Voltaire, 1694-1778. One of the greatest French authors. it mounts a most virulent attack on Shakespeare. We know that Voltaire called Shakespeare a wild drunkard. All these things have to be taken into account.

Now add something else to the great question which is so important for an understanding of the spiritual revolution which took place in the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period. Add to all this the extraordinary part which Schiller played in this spiritual revolution which in Goethe is expressed in a Goethean way in Götz von Berlichingen. In the circle closest of all to Schiller he first met what he had to revolt against. It came out of the most one-sided, unhealthy intellectualism. There was of course as yet no Waldorf school11Lecture Four, Note 3 to do battle against one-sided intellectualism. So Schiller could not be sent to the Waldorf school in Wurttemberg but had to go to the Karlsschule instead. All the protest which Schiller built up during his youth grew out of his protest against the education he received at the Karlsschule. This kind of education—Schiller wrote his drama Die Räuber (The Robbers) against it—is now universally accepted, and no positive, really productive opposition to it has ever been mounted until the recent foundation of the Waldorf school.

So what is the position of Schiller—who later stood beside Goethe in all this? He writes Die Räuber (The Robbers). It is perfectly obvious to those who can judge such things that in Spiegelberg and the other characters he has portrayed his fellow pupils. Franz Moor himself could not so easily be derived from his schoolmates, but in Franz Moor he has shown in an ahrimanic form12Lecture One, Note 3 everything that his genius can grasp of what lives in his time. If you know how to look at these things, you can see how Schiller does not depict spiritual beings externally, in the way they appear in Hamlet or Macbeth, but that he allows the ahrimanic principle to work in Franz Moor. And opposite this is the luciferic principle in Karl Moor. In Franz Moor we see a representative of all that Schiller is rebelling against. It is the same world against which Goethe is rebelling in Götz von Berlichingen, only Schiller sets about it in a different way. We see this too in the later drama Kabale and Liebe (Love and Intrigue).

So you see that here in Central Europe these spirits, Goethe and Schiller, do not depict something in the way Shakespeare does. They do not allow events to lead to something with which one can come to terms. They depict something which is there but which in their opinion ought to have developed quite differently. What they really want does not exist, and what is there on the physical plane is something which they oppose in a spiritual revolution. So we have a strange interplay between what exists on the physical plane and what lives in these spirits.

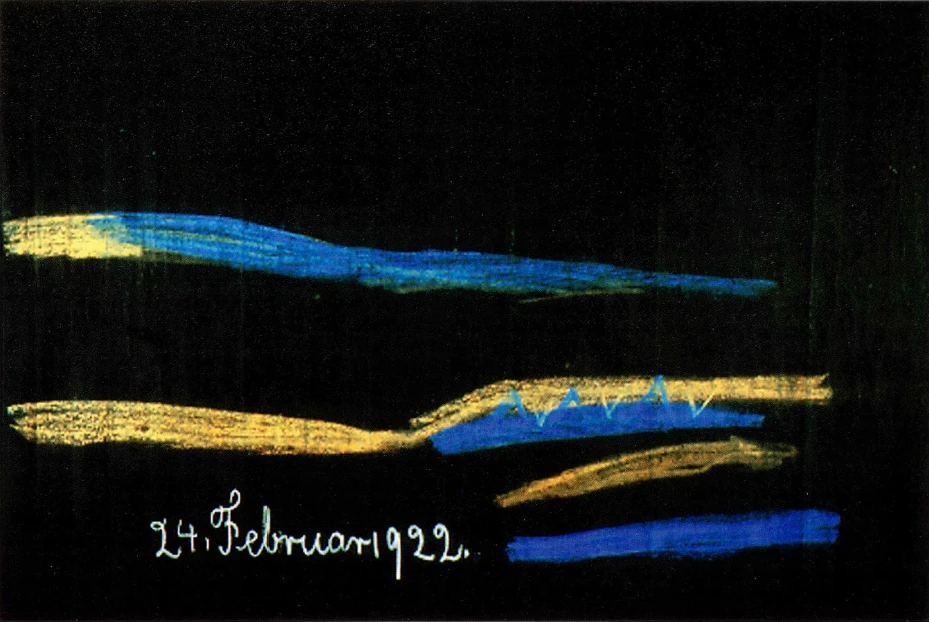

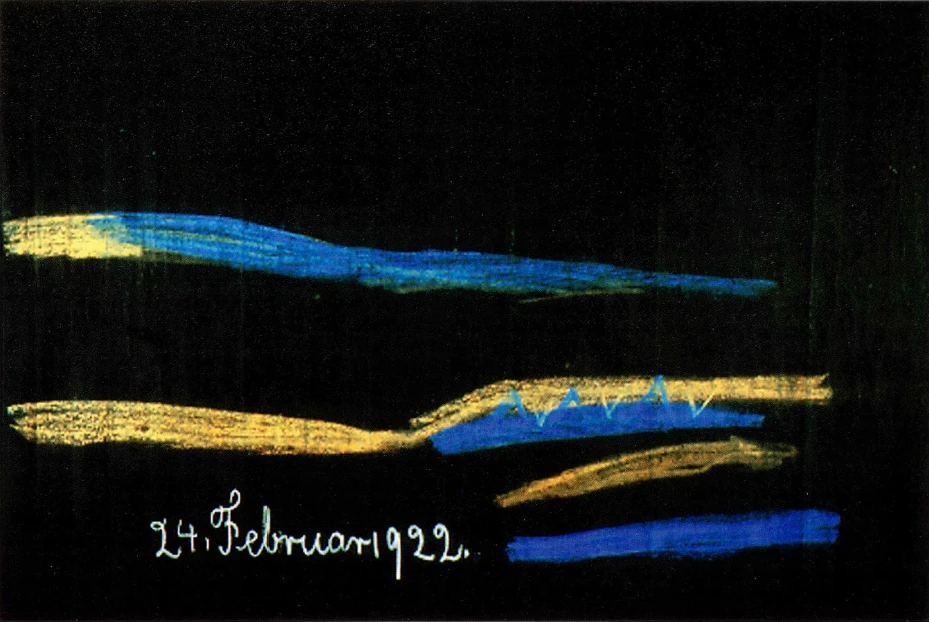

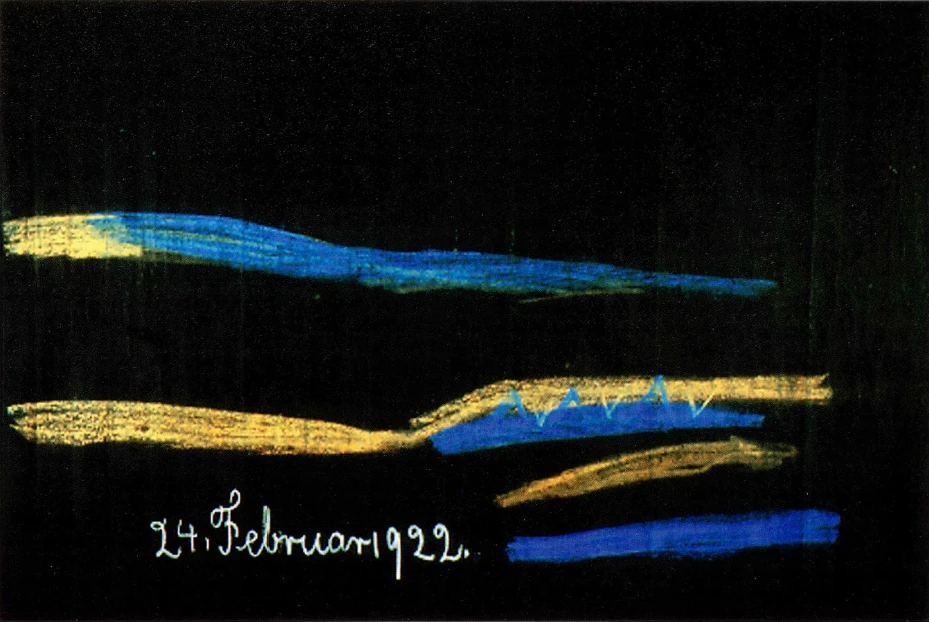

In a rather bold way I could draw it like this: In Shakespeare the events he depicts carry on in keeping with the way things are on earth

(blue). What he takes in from earlier times, in which the spirit still worked, goes over (red) into a present time which then becomes a factual world evolution.

Then we see in Goethe and Schiller that they had inklings of an earlier time (red) when the spiritual world was still powerful, in the fourth post-Atlantean period, and that they bring this only as far as their spiritual intentions, whereas they see what is taking place on earth (blue) as being in conflict with it. One thing plays into the other in the human struggle for the spirit. This is why here in Central Europe the question became a purely human one. In the time of Goethe and Schiller a tremendous revolution occurred in the concept of man as a being who stands within a social context. I shall be able to expand on this in the coming lectures.

Let us now look towards the eastern part of Europe. But we cannot look in that direction in the same way. Those who only describe external facts and have no understanding for what lives in the souls of Goethe and Schiller—and also of course many others—may describe these facts very well, but they will fail to include what plays in from a spiritual world—which is certainly also there, although it may be present only in the heads of human beings. In France the battle takes place on the physical earth, in a political revolution. In Germany the battle does not come down as far as the physical plane. It comes down as far as human souls and trembles and vibrates there. But we cannot continue this consideration in the same way with regard to the East, for things are different there. If we want to pursue the matter with regard to the East we need to call on the assistance of Anthroposophy. For what takes place in the souls of Goethe and Schiller, which are, after all, here on the earth—what, in them, blows through earthly souls is, in the East, still in the spiritual world and finds no expression whatsoever down on the earth.

If you want to describe what took place between Goethe's and Schiller's spirits in the physical world—if you want to describe this with regard to the East, then you will have to employ a different view, such as that used in the days of Attila when battles were fought by spirits in the air above the heads of human beings.

What you find being carried out in Europe by Goethe and Schiller—Schiller by writing Die Räuber (The Robbers) and Goethe by writing Götz von Berlichingen—you will find in the East to be taking place as a spiritual fact in the spiritual world above the physical plane. If you want to seek deeds which parallel the writing of Die Räuber (The Robbers) and the writing of Götz, you will have to seek them among the spiritual beings of the super-sensible world. There is no point in searching for them on the physical plane. In a diagram depicting what happens in the East you would have to draw the element in question like a cloud floating above the physical plane, while down below, untouched by it, would be what shows externally on the physical plane.

Now we know that, because we have Hamlet, we can tell how a western human being who had been a pupil of Faust would have behaved, and could have behaved. But there can be no such thing as a Russian Hamlet. Or can there? We could see a Russian Hamlet with our spiritual eyes if we were to imagine the following: Faust lectures at Wittenberg—I mean not the historical Faust but Goethe's Faust who is actually more true than historical fact. Faust lectures at Wittenberg—and Hamlet listens, writing everything down, just as he does even what the ghost says to him about the villains who live in Denmark. He writes everything down in the book and volume of his brain—Shakespeare created a true pupil of Faust out of what he found in the work of Saxo Grammaticus,13Saxo Grammaticus, d.1204. Danish historian who wrote the Gesta Danorum. which depicts things quite differently. Now imagine that an angel being also listened to Faust as he lectured—Hamlet sat on the university bench, Faust stood on the platform, and at the back of the lecture hall an angel listened. And this angel then flew to the East and there brought about what could have taken place as a parallel to the deeds of Hamlet in the West.

I do not believe that it is possible to reach a truly penetrating comprehension of these things by solely taking account of external facts. One cannot ignore the very profound impression made, by these external facts, particularly on the greatest personalities of the time, when what is taking place is something as incisive as the spiritual revolution which took place between the fourth and fifth post-Atlantean periods.

Shakespeare, Goethe und Schiller im Hinblick auf den geistigen Umschwung im 15. Jahrhundert

[ 1 ] Der Einschnitt zwischen dem vierten und fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, der in das 15. Jahrhundert hineinfällt und den ich als solchen oft bezeichnet habe, hat wirklich viel mehr in der Entwickelung der Menschheit zu bedeuten, als die äußere Geschichte auch heute noch gewöhnlich verzeichnet. Man ist sich nicht bewußt, welch ein gewaltiger Umschwung sich in aller Seelenverfassung der Menschen damals abgespielt hat. Man kann sagen, in das Bewußtsein gerade der besten Geister sind die Spuren dessen, was sich dazumal für die Menschheit vollzogen hat, tief eingegraben. Sie sind es noch lange gewesen und sind es noch heute. Daß sich so etwas Bedeutsames vollziehen kann, ohne daß es zunächst äußerlich stark bemerkt wird, davon liefert ja die Entstehung des Christentums selbst ein Beispiel.

[ 2 ] Bedenken Sie nur, daß dieses Christentum, das im Laufe von fast zwei Jahrtausenden so umgestaltend auf die zivilisierte Welt gewirkt hat, auch für die bedeutendsten Geister der damals maßgebenden römischen Kultur, nach einem Jahrhundert nach dem Mysterium von Golgatha eigentlich noch nicht berücksichtigt war. Wurde es doch damals angesehen wie ein kleines, unbedeutendes Ereignis drüben, an den Grenzen des Reiches, in Asien. Und man darf sagen, ebensowenig ist das, was um das erste Drittel des 15. Jahrhunderts herum sich abgespielt hat für die zivilisierte Welt, bemerkt worden innerhalb dessen, was man äußerlich-dokumentarisch geschichtlich verzeichnet hat. Aber es hat eben durchaus seine Spuren eingegraben in menschliches Streben, in menschliches Ringen.

[ 3 ] Wir haben bereits einiges davon auch in der letzten Zeit wiederum verzeichnet, zum Beispiel die Art, wie es sich in der Dichtung Calderóns in dem «Magus Cyprianus» abgespielt, wie gerade in Spanien dieser geistige Umschwung in der Menschheit aufgefaßt worden ist. Nun aber können wir sehen, wie an den verschiedensten Stellen der Menschheitsentwickelung, wenn auch die Sache nicht so gesagt wird, wie man sie heute aus der Anthroposophie heraus sagen muß, doch ein energischeres Empfinden dafür vorhanden ist, daß man gewissermaßen innerlich-seelisch sich klarwerden muß über diesen Umschwung, der sich da vollzogen hat. Und auch darauf habe ich schon hingedeutet, wie einer der Versuche, aus menschlichem Ringen heraus sich klarzuwerden über diesen Umschwung, der Goethesche «Faust» ist. Aber über diesen Goetheschen «Faust» wird vielleicht noch mehr Licht verbreitet werden, wenn man ihn in einen größeren Weltenzusammenhang hineinstellt. So wie Faust in der Goetheschen Dichtung als geistige Erscheinung zunächst isoliert vor uns dasteht, können wir ihn etwa in der folgenden Art charakterisieren:

[ 4 ] Goethe kommt zunächst in seinem jugendlichen Streben, das natürlich angeregt ist durch den Geisteszustand Europas, dazu, das menschliche Ringen innerhalb des auftauchenden Intellektualismus dramatisch darzustellen. Aus der Art von Bekanntschaft, die er mit der mittelalterlichen Faust-Gestalt, aus dem Volksschauspiel oder dergleichen gemacht hat, stellt sich ihm eben die Persönlichkeit des Faust als ein Repräsentant jener ringenden Persönlichkeiten vor die Seele, die in jenem Zeitalter lebten. Faust gehört allerdings dem 16. Jahrhundert an, nicht dem 15., aber man kann ja sagen, dieser Umschwung vollzog sich nicht in einem Jahre, auch nicht in einem Jahrhundert, sondern ist über die Jahrhunderte hin verteilt. Also Goethe trat die Faust-Gestalt entgegen wie eine Persönlichkeit, die in diesem ganzen Ringen drinnenlebt, aus einer früheren Zeit heraus in eine spätere Zeit hinein. Und man sieht eigentlich, wie Goethe die besondere Art dieses Ringens vom vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum hinüber ganz klar ist. Wir sehen, wie er seinen Faust zunächst als den Gelehrten auftreten läßt, der alle vier Fakultäten kennt, sie hat auf sich wirken lassen, der also in seine Seele die Impulse aufgenommen hat, die aus dem Intellektualismus, aus der intellektualistischen Wissenschaftlichkeit herauskommen, und der auch das menschlich Unbefriedigende des Stehenbleibens im einseitigen Intellektualismus empfindet. Faust wendet sich von diesem Intellektualismus ab, wie Sie wissen, und wendet sich in seiner Art der Magie zu. Man muß sich nur klarwerden, was das eigentlich heißt in diesem Falle. Was da Faust durchgemacht hat «an Philosophie, Juristerei, Medizin und leider auch Theologie», ist das, was man durchmachen kann an der intellektualisierten Wissenschaftlichkeit. Das läßt einen zunächst unbefriedigt. Es läßt einen unbefriedigt aus dem Grunde, weil jene Form der Abstraktheit, durch die diese Wissenschaftlichkeit spricht, eben nur einen Teil des Menschen, den Kopfteil, in Anspruch nimmt, wenn wir uns des Ausdruckes bedienen wollen, und den ganzen übrigen Menschen eigentlich unberücksichtigt läßt.

[ 5 ] Man braucht nur zu vergleichen, wie anders es war in einer vorhergehenden Zeit. Das wird eben gewöhnlich übersehen, daß es durchaus anders war in einer vorhergehenden Zeit. Da haben sich diejenigen Menschen, die zu der Erkenntnis des Lebens und der Welt vordringen wollten, nicht an die verstandesmäßigen Begriffe gewendet, sondern sie gingen alle darauf aus, hinter den sinnlichen Erscheinungen der Umwelt geistige Wirklichkeiten, geistige Wesenhaftigkeiten zu schauen. Das ist es, was eben so schwer verstanden wird, daß nach Erkenntnis ringende Persönlichkeiten etwa des 10., 11., 12. Jahrhunderts durchaus nicht nach bloßen begrifflichen Zusammenhängen gesucht haben, sondern daß sie nach geistiger, wesenhafter Realität gesucht haben, nach dem, was man schauen konnte hinter den sinnlichen Erscheinungen, nicht nach dem, was man bloß denken kann in den sinnlichen Erscheinungen.

[ 6 ] Aber darauf beruht eben dieser Übergang, daß gewissermaßen das, was man früher gesucht hatte, in die Sphäre des Aberglaubens gerückt wurde, daß man die Neigung verlor, nach solchen wirklichen geistigen Wesenheiten zu suchen und daß man für das einzig Mögliche, das wirklich Wissenschaftliche, die intellektualistischen Zusammenhänge hielt. Aber so sehr man auf der einen Seite sich logisch sagte: Nicht abergläubisch sind einzig und allein solche Begriffe, solche Ideen, die der Verstand an der sinnlichen Wirklichkeit ausprägt -, so wenig konnte sich der ganze Mensch, vor allem das menschliche Gemüt, befriedigen in dem, was es dann zuletzt an diesen Begriffen, an diesen Ideen hatte. Und so findet sich denn der Goethesche Faust in der Lage, eben unbefriedigt zu sein an dem Intellektualistischen und sich zurückzuwenden zu dem, was er noch von der Magie weiß.

[ 7 ] Diese Seelenstimmung war schon eine solche, die durchaus bei Goethe echt und ehrlich war. Auch Goethe hatte sich in den verschiedensten. Wissenschaften umgetan an der Universität in Leipzig. Und ehe er eine gewisse schauende Vertiefung dann in Straßburg bei Herder fand, versuchte er - eigentlich auch in der. Abkehr von dem Intellektualismus, der ihm in Leipzig entgegengetreten war - sich, zum Beispiel im Vereine mit Susanne von Klettenberg und durch das Studium von entsprechenden Werken, umzutun in demjenigen Gebiete, das er dann im «Faust» die Magie nennt. Es war durchaus der Goethesche Weg selber. Erst als Goethe dann bei seinem weiteren Studium in Straßburg Herder fand, stand eben ein Geist vor ihm, der selber dem Intellektualismus abgeneigt war. Herder war durchaus kein intellektueller Mensch - daher sein Anti-Kantianismus -, der dann Goethe in gewisser Weise, ohne die Magie, über dasjenige hinwegführte, was er aus einer wirklich faustischen Stimmung heraus vorher in Anlehnung an die alte Magie sich zu erringen versucht hatte.

[ 8 ] So hat Goethe eigentlich hingesehen auf diesen Faust des 16. Jahrhunderts —- man könnte ebensogut sagen: auf den Gelehrten des 15. Jahrhunderts, der aus der Magie herauswächst, aber halb noch darinnensteht — indem er, Goethe, selbst sein tiefstes inneres Ringen darstellen wollte, wie es sich ihm ergab, weil die Spuren des Umschwunges von dem vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum durchaus in ihm noch nachwirkten.

[ 9 ] Es gehört wohl zu dem interessantesten Punkte der neueren Geistesentwickelung, daß Goethe, indem er sein eigenes Jugendringen zum Ausdruck bringen wollte, sich an den Professor des 15., des 16. Jahrhunderts wandte, um in dieser Gestalt sein eigenes inneres Seelenleben und Seelenerfahren dramatisch zu charakterisieren. Man mißversteht natürlich vollständig sowohl das, was in Goethe lebte, wie auch das, was im 15., 16. Jahrhundert als der große Umschwung vorhanden war, wenn man mit Du Bois-Reymond sagt, Goethe habe einen großen Fehler begangen, indem er seinen «Faust» so dargestellt hat, wie er ihn dargestellt hat; er hätte ihn ganz anders machen sollen. Faust hätte allerdings vielleicht unbefriedigt sein müssen von dem, was ihm das Traditionelle hätte geben können. Allein, wenn Goethe imstande gewesen wäre, den Faust ordentlich darzustellen, so würde Faust, nachdem er die ersten Szenen durchgemacht hat, nachher Gretchen ehrlich gemacht, geheiratet haben und ein wohlbestallter Professor geworden sein, der die Elektrisiermaschine und die Luftpumpe erfunden hätte. - Das ist die Anschauung, die Du BoisReymond hat, wie der Faust eigentlich hätte werden sollen.

[ 10 ] Nun, Goethe hat eben den Faust nicht so gemacht, und ich weiß nicht, ob er viel interessanter geworden wäre, wenn er so ausgestaltet zur Welt gekommen wäre, wie Du Bois-Reymond es gewollt hat. Aber jedenfalls, so wie der Goethesche Faust dasteht, ist er eine der interessantesten Erscheinungen der neueren Geistesgeschichte dadurch, daß eben Goethe sich gedrungen fühlte, den Professor des 15. und 16. Jahrhunderts als den Repräsentanten dessen hinzustellen, was in ihm, in Goethe selber, nachzitterte von jenem Umschwung von dem vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum hinüber.

[ 11 ] Wir wissen ja, daß der Faust des 16. Jahrhunderts — der also auch sagenhaft, nicht als der Mann, der die Elektrisiermaschine und die Luftpumpe erfindet, ausgestaltet war —, daß der sich auch der Magie zuwendet, aber’ wirklich zugrunde geht, dem Teufel verfällt, daß dieser Faust des 16. Jahrhunderts, schon von Lessing und auch von Goethe, nicht als der Faust des 18. Jahrhunderts anerkannt werden konnte. Vielmehr mußte gestrebt werden zu zeigen, wie nun, trotzdem wiederum zum Geistigen hingestrebt wird, der Mensch dennoch seinen Weg, wenn man das Wort gebrauchen darf, zur Erlösung hin finden soll. |

[ 12 ] So steht zunächst der Faust da als der Professor des 15., des 16. Jahrhunderts, den Goethe eigentlich wirklich gut zeichnet, denn so sind sie durchaus gewesen an den Universitäten dazumal, solche Persönlichkeiten. Natürlich, der Faust der Sage kommt da gar nicht in Betracht, der Faust der Sage war natürlich niemals dieser Professor, sondern mehr ein herumvagabundierender Zigeuner; aber Goethe zeichnet ja auch nicht diesen Faust der Sage, sondern er charakterisiert eben eine Professorengestalt. Und es ist durchaus so, daß wir sagen können: So wie Goethe seinen Faust charakterisiert hat - in der Tiefe der Seelenempfindungen ist er natürlich eine einzelne Gestalt, eine Ausnahme -, so wie er ihn hineingestellt hat in den geistigen Betrieb, wenn ich mich des Ausdrucks bedienen darf: auf der einen Seite sich mit den intellektualistischen Wissenschaften befassend, aber doch nicht unbekannt mit einem gewissen Hinneigen zu Geistigkeiten, die schon zu Goethes Zeiten natürlich durchaus als Aberglaube bezeichnet wurden -, so ist dieser Faust durchaus der Typus eines, sagen wir Philosophieprofessors oder vielleicht auch eines Medizinprofessors des 14., 15. Jahrhunderts.

[ 13 ] Nun können wir aber auch diesen Goetheschen «Faust» mehr in einen größeren Weltenzusammenhang hineinstellen. Goethe selbst führt uns zwar den Famulus Faustens vor, und wir sehen da, welches Verhältnis besteht zwischen dem Professor und seinem Famulus. Wir sehen auch einen Schüler, können aber nicht eigentlich glauben, daß der Schüler nun ganz besonders tiefen Einfluß von seinem Professor Faust erhalten habe, das geht schon aus der Art hervor, wie er sich später entwickelt. Also im Goetheschen «Faust» selber sehen wir eigentlich wenig von der Wirkung des Faust, das heißt des seelenvertieften Professors des 14. und 15. Jahrhunderts, wie er etwa in Wittenberg gelehrt haben könnte. Aber man könnte doch sagen, es gibt einen Schüler dieses Faust, der uns tiefer hineinführen kann in diesen “ ganzen Weltenzusammenhang. Es gibt einen Schüler des Faust, der nun fast mit derselben Bedeutung in der Geistesgeschichte der Menschheit drinnensteht wie der Professor Faust selber — ich meine natürlich immer den Goetheschen Faust. Und dieser Schüler, das ist kein anderer als Hamlet.

[ 14 ] Hamlet kann tatsächlich angesehen werden als ein richtiger Schüler des Faust. Das Historische kommt dabei nicht in Betracht, ich meine immer das, was Goethe hingestellt hat als den Faust. Schon der ganze Fortgang des Faust bezeugt es ja, daß wir es zwar zu tun haben mit der Menschheitsauffassung des 18. Jahrhunderts, daß Goethe aber doch das Bestreben hat, seinen Faust zurückzudatieren. In einer gewissen Beziehung können wir eben durchaus sagen: Hamlet, der in Wittenberg studiert hat, und der sich eine gewisse Geistesverfassung aus diesem Studium mit nach Hause bringt, Hamlet, wie ihn Shakespeare hingestellt hat, ist in einer gewissen Weise anzusehen, allerdings weltgeistesgeschichtlich, als ein Schüler des Faust. In ihm haben wir vielleicht sogar etwas, was wir in viel treuerem Sinne eine Schülerschaft des Faust nennen können als das, was uns in der Goetheschen Dichtung selber als eine solche Schülerschaft des Faust entgegentritt.

[ 15 ] Bedenken Sie einmal den ganzen Charakter des Hamlet und stellen Sie es mit der Tatsache zusammen, daß er in Wittenberg studiert hat, wo er durchaus eine solche Gestalt wie den Faust als Professor gehört haben könnte, und nehmen Sie dann die Art und Weise, wie Hamlet zu seiner Aufgabe kommt: Der Geist seines Vaters erscheint ihm. Also er hat etwas zu tun mit der wirklichen geistigen Welt. Er ist zunächst hineingestellt in die wirkliche geistige Welt. Aber er hat in Wittenberg studiert, er hat in Wittenberg so gut studiert, daß er das menschliche Gehirn für ein Buch ansieht. Erinnern Sie sich an die Phrase des Hamlet, wo von dem Buch des Gehirns die Rede ist. Er hat so gut menschliche Wissenschaft studiert, daß er von dem Buch des Gehirns spricht, daß er sich sogar auf seine Schreibtafel aufschreibt, was er im Gedächtnis behalten will, fast wie wenn er den Spruch der späteren Faust-Dichtung im Auge hätte: «Was man schwarz auf weiß besitzt, kann man getrost nach Hause tragen.» Also Hamlet ist auf der einen Seite ein ganz trefflicher Schüler des Intellektualismus, wie er ihm in Wittenberg beigebracht worden ist, aber er steht auf der andern Seite in einem geistigen Zusammenhange darinnen, und beide Impulse wirken in seiner Seele. Und das ganze Hamlet-Drama steht eigentlich unter dem Einflusse dieser beiden Impulse. Hamlet, als Dichtung sowohl wie als Gestalt, steht unter dem Einfluß dieser Impulse, denn im Grunde genommen weiß der Dichter des «Hamlet» auch nicht recht, wie er die geistige Welt und die intellektualistische Seelenverfassung zusammenbringen soll. Dichtungen, die solche ‘wirklich im Leben tief wurzelnden Eigentümlichkeiten haben, die geben dann den Kommentatoren reichlich Gelegenheit zum Streiten. Daher werden über solche Dichtungen viele Bücher geschrieben, aus denen man allerdings nicht recht klug wird, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil es auch gar nicht nötig ist, darüber klug zu werden. Man kann nämlich immerfort sehen, wie die Kommentatoren als wichtige Probleme behandeln: Sind die Geister im «Hamlet» bloß ein Bild oder haben sie eine objektive Bedeutung? Wie hat man das zu bewerten, daß nur Hamlet den Geist sieht, die andern Personen nicht, die gleichzeitig auf der Bühne sind?

[ 16 ] Denken Sie sich nur, was da alles außerordentlich Geistvolles und Interessantes darüber geschrieben worden ist! Nur trifft man damit selbstverständlich gar nicht das, was für den Dichter des «Hamlet» in Betracht kommt, denn für den kommt gerade in Betracht, daß er, der dem 16. und 17. Jahrhundert angehörte, über dieses Problem notwendigerweise, weil er lebensvoll schreiben mußte, so schreiben mußte, daß man die Art, wie er die Sache auffaßt, gar nicht in abstrakte Begriffe einfassen kann. Man sollte es in solchen Formen, wie es die Kommentatoren machen, lieber bleiben lassen; deshalb bezeichne ich es als unnötig. Denn da handelte es sich gerade um jenen Übergang, der herüberführte von der Zeit her, wo man sich noch klar war: Die geistigen Wesenheiten sind Realitäten wie ein Tisch oder Stuhl oder wie ein Hund oder eine Katze; denn das war so. Und dem Calderón, der noch auf dem alten Standpunkte stand, obwohl er sogar einer etwas späteren Epoche angehört als Shakespeare, Calderón wäre es gar nicht eingefallen, irgendwie auch nur anzudeuten, daß, was er als geistige Wesenheiten vorführt, irgendwie nur einen subjektiven Charakter haben könnte. Der stellt, weil er mit seiner ganzen Seele in der Anschauung drinnensteht, alles Geistige ebenso handfest hin wie Hunde und Katzen.

[ 17 ] Natürlich, bei Shakespeare kommt eben schon in Betracht, daß er mit seiner Seelenverfassung ganz in der Übergangszeit drinnensteht und daher sich gar nicht gedrungen fühlen kann, diese Frage als Dichter anders zu behandeln, als: Es kann so sein, und es kann so sein. — Die Grenze ist gar nicht so ganz sicher zwischen dem, ob nun die Geister subjektiv oder objektiv sind. Das ist ja ohnedies eine Frage, die für eine höhere Weltanschauung ebenso aufhört wie die deutlichen, für das Leben - nicht für die Astronomie - zu bestimmenden Grenzen zwischen Tag und Nacht. Diese Frage, ob das eine subjektiv, das andere objektiv ist, die hört dann auf, wenn man die Objektivität der menschlichen Innenwelt erkennt und die Subjektivität der Außenwelt. Aber gerade in diesem lebensvollen Verschweben hält Shakespeare das, was er im «Hamlet» und auch, sagen wir zum Beispiel in «Macbeth» darstellt. Wir sehen, daß also die Dichtungen - Shakespeares durchaus herausgeholt sind aus dem Übergang von dem vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum.

[ 18 ] Im «Hamlet» kommt das allerdings am bedeutendsten zum Ausdrucke. Hamlet hat vielleicht gerade in Wittenberg, wenn ich mich jetzt etwas, sagen wir unhistorisch, aber deshalb vielleicht nicht weniger wahr ausdrücken darf, diejenigen Semester studiert, wo Faust-Sie wissen jetzt, nach den Voraussetzungen, was ich damit meine - weniger über Magie und mehr über intellektualistische Wissenschaften gelesen hat. Also er ist vielleicht in Wittenberg gewesen, bevor Faust selber zu dem Geständnisse gekommen ist, daß er zehn Jahre kreuz und quer und grad und krumm seine Schüler an der Nase herumgeführt hat. Hamlet gehört vielleicht gerade zu denjenigen, die an der Nase herumgeführt worden sind; also sein Studium fällt vielleicht gerade in diese zehn Jahre hinein. Und nun, als er wiederum zurückkommt und das Ganze aufgenommen hat aus einer Seele heraus, die selber unsicher war- denn man kann sich natürlich ganz klar sein darüber, daß Faust unsicher war in den zehn Jahren, wo er seine Schüler kreuz und quer und grad und krumm an der Nase herumgeführt hat -, nun steht er auf der einen Seite der Erfahrung der geistigen Welt gegenüber, demjenigen also, was geblieben ist aus der früheren Zeit und was für ihn noch vorhanden ist, und auf der andern Seite steht er jener menschlichen Anschauung gegenüber, die einfach das Geistige vertreibt. Denn gerade so, wie die Geister vor dem Lichte fliehen, so flieht die Anschauung der Geister vor dem Intellektualismus. Die geistige Anschauung kann den Intellektualismus nicht vertragen, und dann kommt die Seelenstimmung heraus, von der man etwa sagen kann: Der Mensch wird innerlich ganz herausgerissen aus dem geistigen Zusammenhang. Er wird von des Gedankens Blässe innerlich angekränkelt. Dann kommt eben eine solche Stimmung zustande, wie sie eigentlich als Seelenstimmung den ganzen Zeitraum charakterisiert vom 11. bis zum 15. Jahrhundert und in die folgenden Jahrhunderte noch hinein. Und Goethe, weil er für alles empfänglich war, ragte in diesen Zeitraum auch mit seiner Seelenverfassung noch hinein. Darüber muß man sich nur klar sein.

[ 19 ] Man nehme einmal das griechische Drama. Dieses griechische Drama ist ja gar nicht denkbar ohne die dahinterstehenden geistigen Mächte. Die bestimmen die Menschenschicksale. Der Mensch ist eingesponnen in das, was als Schicksale die geistigen Mächte flechten. Da wird das, was der Mensch eigentlich nur erleben könnte, wenn er die Schlafzustände bewußt erlebte, in das gewöhnliche Leben hereingetragen. Da wird hereingetragen in das gewöhnliche Leben, wie in den Willen das hereinkommt, was im Willen auch beim Tagwachen verschlafen wird. Das griechische Schicksal ist ein Hinblicken auf das, was sonst verschlafen wird. Der Grieche ist sich bewußt, daß, wenn er seinen Willen entfaltet, wenn er übergeht in die Handlung, daß dann nicht nur das Tagwachen wirkt mit den blassen Gedanken, sondern daß da, weil der ganze Mensch wirkt, auch das wirkt, was im Menschen pulsiert, wenn der Mensch schläft. Aus einer solchen Empfindung geht dann auch eine ganz bestimmte Stellung zu der Frage des Todes, zu der Frage der Unsterblichkeit hervor.

[ 20 ] Nun kommt der Zeitraum, der von mir eben bezeichnet worden ist, in dem der Mensch kein Bewußtsein mehr davon hat, daß in ihn während des Schlafes ein Geistiges hereinwirkt, das auch in den Willen hereinspielt. Es kommt der Zeitraum, wo der Mensch den Schlaf als das Seine, könnte man sagen, hinnimmt, wo er aber doch durch alte Tradition ein Bewußtsein davon hat: man hängt mit der geistigen Welt zusammen. Schon dämmern herauf die ganz abstrakten Begriffe: «Philosophie, Juristerei, Medizin und leider auch Theologie» in der modernen Gestalt. Das dämmert herauf, aber es spielt noch das frühere Anschauen herein. Das bewirkt einen Dämmerzustand. In diesem Dämmerzustand hat man allerdings gelebt, und im Grunde genommen sind solche Gestalten wie der Faust herausgeboren aus einem Dämmerzustande, aus einem Hineinblicken in die geistige Welt, das wie ein Um-sich-Blicken im Traume ist. Und man bedenke die Stimmung, die da steht hinter solchen Worten wie «Schlaf», «Traum» im «Hamlet». Man möchte sagen, indem Hamlet seine Monologe spricht, spricht er einfach auf empfindungsgemäße, natürlich nicht auf theoretische, sondern auf empfindungsgemäße Weise die Rätsel seines Zeitalters aus.

[ 21 ] Und so sehen wir, wie über die Jahrhunderte hinweg, aber im Zusammenhang der Geister, Shakespeare den Schüler darstellt, Goethe den Professor, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil natürlich einige Jahrhunderte verflossen waren und man in der Goethe-Zeit mehr nach dem Quell zurückgehen mußte dessen, um was es sich da handelte. Aber wir werden da in einen Zusammenhang hineingeführt, der uns wirklich zeigt, wie im Bewußtsein der Menschen etwas lebt von der Art etwa, daß sich solche hervorragende Geister sagen: Ich muß zum Ausdrucke bringen, was da eigentlich als ein Übergangszustand in der Menschheitsentwickelung vorhanden ist.

[ 22 ] Nun ist das außerordentlich Interessante, diese Weltstellung, möchte ich sagen, weiter auszudehnen, weil ja eine Unsumme von ganz umfassenden Fragen und Lebens- und Weltenrätseln auftauchen. Es ist interessant, zum Beispiel zu sehen, wie man unter den Shakespeareschen Werken «Hamlet» als die reinste Darstellung einer Persönlichkeit hat, die den ganzen Dämmerzustand des Übergangs, namentlich in den Monologen, zum Ausdruck bringt. Man möchte sagen, wenn man den Hamlet verstanden hat vom 17. bis zum 18. Jahrhundert, dann hätte man fragen können: Ja, wo ist denn in der Seele des Hamlet das angeregt worden? — Man ist hingewiesen nach Wittenberg. Man ist hingewiesen nach der Faust-Quelle. Zu ganz ähnlichen Fragen kommt man dann, wenn man «Macbeth» betrachtet; aber schon ist es hereingezogen in das Menschliche, wenn man «Lear» betrachtet. Da wird die Frage nicht mehr so nahe herangerückt an das Erdgebiet nach dem Geistigen hin, darückt sie in den Menschen hinein, wird zum subjektiven Zustand, aber auch dafür zum Wahnsinn.

[ 23 ] Und dann könnte man die andern Shakespeareschen Dramen in Betracht ziehen und könnte sagen: Was der Dichter dieser Dramen hat lernen können an den Gestalten, wo er das Menschliche bis an das Geistige heranführt, das lebt dann fort in den Königsdramen, ohne daß er da noch dasselbe Thema in derselben Weise weiterverfolgt; aber die unbestimmten Kräfte wirken weiter. Nur daß man, wenn man nun die Shakespeareschen Dramen als Ganzes weiterverfolgt, eigentlich immer das Gefühl hat: sie gipfeln in dem Zeitalter der Königin Elisabeth. Shakespeare hat darstellen wollen, was aus unterbewußten, brodelnden Völkerkräften heraus zu der intellektualistischen Klarheit führt, die, seit dem Zeitalter der Elisabeth, von diesem Winkel der zivilisierten Welt ganz besonders ausgeht. Von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus erscheint die ganze Shakespearesche Dramenwelt wie eine Art, ich will nicht sagen Lustspiel, das befriedigend ausgeht, aber wenigstens wie ein Drama, das einen gewissen befriedigenden Schluß hat. Das heißt, er führt zu einer Welt, die sich dann weiterentwickelt, die dann, nachdem der Umschwung eine Zeitlang da war — Shakespeare führt ja seine Dramenwelt bis in seine eigene Gegenwart -, die Anschauung der unmittelbaren Gegenwart zurückläßt, die eben weiter geht als eine Welt, mit der man sich abfindet. Das ist ja das Merkwürdige, daß die Shakespearesche Dramenwelt bis zu der Shakespeareschen Gegenwart führt, mit der man sich dann abfindet, weil von da aus die Geschichte mit einem befriedigenden Verlauf, in den Intellektualismus verlaufend, eben weitergeht. Der Intellektualismus geht von jenem Winkel aus, von dem Shakespeare gedichtet hat, was er dargestellt hat, indem er es zu diesem Ende geführt hat.

[ 24 ] Die Fragen, die ich meine, die gehen einem dann auf, wenn man die Linien verfolgt herüber von dem Schüler Hamlet bis zu dem Professor Faust und nun fragt, wie es denn mit Goethe gestanden hat in der Zeit, in der er aus seinem Ringen heraus zu der Faust-Gestalt gekommen ist. Ja, sehen Sie, da hat Goethe auch den «Götz von Berlichingen» gedichtet. Im «Götz von Berlichingen», wiederum aus Volkstümlichem heraus, stehen einander gegenüber einerseits durchaus alte Mächte aus der vorintellektualistischen Zeit, das alte deutsche Kaisertum, das ja durchaus nicht verglichen werden darf mit dem, was später deutsches Kaisertum geworden ist, die Ritter, die Bauern, dasjenige also, was aus einer vorintellektualistischen Zeit durchaus nicht von des Gedankens Blässe angekränkelt ist — was sich nicht nur so wenig auf den Kopf beschränkt, daß es auch die Hände braucht, sondern sogar eine eiserne Hand gebraucht. Es wird zurückgegangen zu etwas, was einmal gelebt hat in der neueren Zivilisation, was aber gewissermaßen seinem ganzen Wesen nach noch im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum wurzelt. Und dem steht andererseits gegenüber, etwa in der Gestalt Weislingens, nun das andere, was dann heraufkommt: Die intellektualistische Zeit, die innig zusammenhängt mit dem deutschen Fürstentum, das dann die späteren Zustände in Mitteleuropa bis zu der heutigen Katastrophe herbeigeführt hart.

[ 25 ] Man sieht, wie Goethe im «Götz von Berlichingen» eigentlich anstürmt gegen dieses Fürstentum, wie er zurückschaut auf die Zeiten, in denen der Intellektualismus noch nicht da war, wie er Partei nimmt für das Alte, wie er sich auflehnt gegen das, was gerade in Mitteleuropa an die Stelle dieses Alten getreten ist. Man möchte sagen: Es ist so, wie wenn Goethe im «Götz von Berlichingen» sagen wollte, der Intellektualismus hat auch Mitteleuropa ergriffen. Aber hier erscheint er nicht als etwas, was nichts Berechtigtes hat. Goethe wäre es gar nicht eingefallen, Shakespeare zu negieren. Wir wissen, wie Goethe sich zu Shakespeare im positiven Sinne verhalten hat. Ihm wäre es nicht eingefallen, etwa Shakespeare deshalb zu tadeln, weil er zuletzt zu einem Ende geführt hat, das bleiben konnte. Im Gegenteil, das war Goethe außerordentlich sympathisch.

[ 26 ] Aber wiederum: Die Art und Weise, wie dann der Intellektualismus sich gerade in Goethes Umgebung ausgebildet hat, veranlaßt Goethe dazu, daß er dieses Bestehende, Daseiende eigentlich als etwas Unberechtigtes hinstellt, daß er da seinerseits das, was in der Französischen Revolution als das Politische zum Ausdrucke gekommen ist, geistig anfaßte. Goethe ist in «Götz von Berlichingen» der geistige Revolutionär, der das Geistige negiert, so wie die Französische Revolution das Politische negiert hat. Aber nun wendet sich Goethe in einem gewissen Sinne zurück zu dem, was da war, das er ja gewiß nicht in der alten Gestalt wiederum erneuert wünschen kann. Aber er will, daß es eine andere Entwickelung nehme. Es ist außerordentlich interessant, diese Stimmung in Goethe zu beachten, wie er wirklich sich auflehnt gegen das, was sich an die Stelle der «Götz»-Welt gesetzt hat.

[ 27 ] So ist es außerordentlich interessant, daß Shakespeare so tief erfaßt worden ist von Lessing, von Goethe, daß sie geradezu in Anlehnung an Shakespeare gesucht haben, was sie aus ihrer geistig-revolutionären Stimmung heraus finden wollten, während da, wo sich der Intellektualismus ganz besonders tief eingegraben hat aus den Vorbedingungen heraus, zum Beispiel bei Voltaire, dieser Intellektualismus auf Shakespeare in der wüstesten Weise losschlägt. Voltaire hat bekanntlich Shakespeare einen besoffenen Wilden genannt, Diese Dinge müssen alle durchaus berücksichtigt werden.

[ 28 ] Nun, stellen Sie, um die große Frage zu verstehen, die da auftaucht und die insbesondere zur Charakteristik vom Umschwung des vierten zum fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraume von so großer Bedeutung ist, stellen Sie zu dem etwas anderes hinzu. Stellen Sie hinzu, wie eigentümlich nun Schiller eingegriffen hat in diese geistige Revolution, die bei Goethe auf Goethesche Art im «Götz von Berlichingen» zum Ausdrucke kommt. Schiller hat zunächst im engst umrissenen Kreise das kennengelernt, wogegen er sich aufzulehnen hatte, als aus dem einseitigsten, krankhaftesten Intellektualismus herauskommend. Da es dazumal noch keine Waldorfschule gab, die sich auch gegen den einseitigen Intellektualismus auflehnt und Schiller nicht in Württemberg auf die Waldorfschule geschickt werden konnte, wurde er auf die Karlsschule geschickt. Und alles, was Schiller nun in seiner Jugend als Protest entwickelt, ist im Grunde genommen aus dem Protest gegen die Pädagogik der Karlsschule geboren. Es hat im Grunde genommen ein wirkliches produktives Arbeiten gegen diese Pädagogik, die heute die Weltpädagogik ist - trotzdem Schiller seine «Räuber» dagegen geschrieben hat -, es hat ein wirkliches positives Arbeiten dagegen nicht gegeben, bis zu der Begründung der Waldorfschule.

[ 29 ] Nun, wie stellt sich Schiller, der ja später an die Seite Goethes gestellt war, in diese ganze Umgebung hinein? Er dichtet seine «Räuber». In Spiegelberg und in den andern Gestalten erkennen wir ganz deutlich, wenn wir nur solche Dinge zu beurteilen wissen, daß er seine Mitschüler gezeichnet hat. Karl Moor konnte er natürlich nicht gerade aus seinen Mitschülern heraus gewinnen, aber er schilderte in . Karl Moor den Mitschüler so, daß er eigentlich all das, was nun aus der genialen Erfassung der neueren Zeit herauskommt, in ahrimanischer Gestalt in Karl Moor hinstellte*. Und wer diese Dinge zu beurteilen vermag, der sieht überall, wie Schiller zwar nun nicht mehr geistige Wesenheiten äußerlich darstellt, wie sie noch im «Hamlet», in «Macbeth» auftreten, sondern wie Schiller das ahrimanische Prinzip in Karl Moor wirksam sein läßt. Und dem steht gegenüber das luziferische Prinzip in Franz Moor. Und in Franz Moor sehen wir einfach einen Repräsentanten dessen, wogegen Schiller sich nun auflehnte. Wiederum ist es dieselbe Welt, gegen die Goethe sich im «Götz von Berlichingen» auflehnt, nur tut Schiller es auf eine andere Weise. Das lehrt ja später «Kabale und Liebe».

[ 30 ] So sehen wir, daß hier, in Mitteleuropa, diese Geister, Goethe und Schiller, nicht so zeichnen wie Shakespeare. Sie lassen die Geschehnisse nicht einlaufen in etwas, was dann bleiben kann, sondern sie stellen etwas dar, was da war, aber nach ihrer Ansicht eine ganz andere Entwickelung hätte nehmen sollen. Also das, was sie eigentlich wollen, ist nicht da, und das, was auf dem physischen Plane da ist, gegen das lehnen sie sich zunächst in einer geistigen Revolution auf. So daß wir hier ein merkwürdiges Ineinanderspielen haben von dem, was auf dem physischen Plane da ist, und dem, was in diesen Geistern lebt.

[ 31 ] Wenn ich das in einem etwas gewagten Bilde graphisch darstellen sollte, was da eigentlich ist, so möchte ich es so zeichnen: Wir haben bei Shakespeare das Bild so, daß die Geschehnisse durchaus erdenmäßig weiterlaufen (siehe Zeichnung, blau), daß das, was er aus der früheren Zeit, in der noch das Geistige gewirkt hat, heraufnimmt, [daß das] weiterwirkt (rot), und daß es überläuft in eine Gegenwart, die dann eben die Tatsache des weltgeschichtlichen Verlaufs bildet.

[ 31 ] Wir gewahren dann, wenn wir bei Goethe und bei Schiller nehmen, was sie an Ahnungen einer alten Zeit haben [siehe Zeichnung S. 162] (rot), einer Zeit, wo noch die geistige Welt mächtig war, im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, daß sie das heraufführen bloß in ihren Intentionen, in ihre Geistigkeit, während sie das, was sich auf der Erde abspielt (blau), im Kampfe damit auffassen. Ich möchte sagen, da haben wir das eine in das andere hineinspielend auf dem Umwege durch den menschlichen Geisteskampf. Und das ist durchaus der Grund, warum hier dann in Mitteleuropa der Übergang gefunden wurde zu dem reinen Menschheitsproblem. So daß — und das werde ich noch weiter ausführen können in den folgenden Betrachtungen tatsächlich in der besonderen Auffassung des Menschen als eines Wesens, das im sozialen Zusammenhange drinnensteht, durch die Goethe-Schiller-Zeit ein mächtiger Umschwung geschieht.

[ 32 ] Sehen wir jetzt nach dem Osten hinüber, nach dem Osten Europas. Ja, in derselben Weise können Sie überhaupt nicht nach dem Osten hinüberschauen. Wer bloß die äußeren Tatsachen schildert und kein Verständnis hat für das, was in den Seelen Goethes, Schillers und natürlich vieler anderer lebte, der wird zwar die äußeren Tatsachen schildern, aber nicht das, was da hineinspielt aus einer geistigen Welt, die immerhin vorhanden ist, die aber nur in den Köpfen der Menschen vorhanden ist. In Frankreich wird revolutionär auf dem politischen Boden, auf dem physischen Plane der Kampf vollzogen. In Deutschland geht er nicht bis zu dem physischen Plane herunter, aber durch die Menschenseelen geht er noch hindurch, in den Menschenseelen zittert er. Aber diese ganze Betrachtung läßt sich nicht ausdehnen nach dem Osten, denn im Osten ist die Sache anders. Da kommt man nämlich, wenn man das nun weiterverfolgen will, erst mit der Anthroposophie der Sache nahe, denn da ist, was in den Seelen Goethes und Schillers, also immerhin schon auf der Erde, wenn auch durch Erdenseelen wirbelt, das ist noch erst in der höheren Welt vorhanden, und es kommt überhaupt nicht unten auf der Erde zum Ausdrucke.

[ 33 ] Wenn Sie das, was sich zwischen Goethes und Schillers Geist in der physischen Welt abspielt, nach Rußland hinüber verfolgen wollen, dann müssen Sie schon etwa so schildern, wie man die Schlachten schilderte in der Attila-Zeit, wo sich etwas über den Köpfen der Menschen in den Lufträumen oben abspielte, wo die Geister miteinander ihre Schlachten ausführten.

[ 34 ] Was Sie in Mitteleuropa ausgeführt finden durch Goethe und Schiller — bei Schiller, indem er die «Räuber», bei Goethe, indem er den «Götz von Berlichingen» schreibt -, das finden Sie im Osten noch als geistige Tatsache, über dem physischen Plan in der geistigen Welt sich abspielend. Wollen Sie da die Paralleltaten für das Schreiben der «Räuber», des «Götz» suchen, dann müssen Sie es bei den Geistern in der übersinnlichen Welt suchen; Sie können sie nicht auf dem physischen Plane suchen. So daß man für diesen Osten es dann so darstellen könnte: Wie Wolken, über dem physischen Plane sich abspielend, haben wir das, was die Sache erst verständlich macht, und unten, ganz unberührt davon das, was verzeichnet werden kann äußerlich auf dem physischen Plane.

[ 35 ] Und man kann sagen: Man weiß also, wie sich ein westlicher Mensch, der ein Schüler des Faust geworden war, verhalten hat, verhalten konnte, denn man hat den Hamlet. Den russischen Faust könnte man nicht haben. Oder doch - ? Ja, vor dem geistigen Blick könnte man ihn haben, wenn man sich vorstellen würde: Während Faust in Wittenberg lehrt und Hamlet ihm zuhört, der sich ja alles aufschreibt — selbst das, was ihm der Geist sagt und daß es Schurken gibt in Dänemark und so weiter, also alles das, was das Buch des Gehirns braucht -, da würde auch eine Engelwesenheit ihm zuhören. — Ich meine immer den Goetheschen Faust, keine historischen Tatsachen, aber das, was wahrer als die Geschichtsdarstellung ist. Man bedenke, was Shakespeare aus der Gestalt gemacht hat, die er dem Saxo Grammatikus entnommen hat, wo die Sache ganz anders ist, wo auch kein Anhaltspunkt dafür ist, wie Shakespeare wirklich den Schüler des Faust gestaltet hat. - Also: Während Hamlet auf der Schulbank gesessen hat, Faust auf dem Katheder gestanden hat, hätte hinten ein Engel zugehört und wäre dann nach Osten geflogen. Dort hätte dieser Engel dann seinerseits dasjenige entwickelt, was sich parallel den Taten des Hamlet im Westen hätte abspielen können. Ich glaube nicht, daß man zu einem wirklich eindringenden Verständnis kommt, wenn man bloß die äußeren Tatsachen beachtet und nicht die tiefgehenden Eindrücke, die diese äußeren Tatsachen gerade auf die bedeutendsten Persönlichkeiten der Zeit gemacht haben, namentlich wenn es sich um etwas so Einschneidendes handelt wie den Umschwung vom vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Morgen wollen wir dann davon reden.

Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller in light of the intellectual revolution of the 15th century

[ 1 ] The turning point between the fourth and fifth post-Atlantean epochs, which falls in the 15th century and which I have often referred to as such, really has much more significance for the development of humanity than is usually recognized even today in external history. People are not aware of the tremendous change that took place in the entire state of mind of human beings at that time. One can say that the traces of what happened to humanity at that time are deeply engraved in the consciousness of the best minds. They have been so for a long time and still are today. The emergence of Christianity itself provides an example of how something so significant can take place without initially being strongly noticed externally.

[ 2 ] Just consider that Christianity, which has had such a transformative effect on the civilized world over the course of almost two millennia, was not really taken into account even by the most eminent minds of the then dominant Roman culture, a century after the Mystery of Golgotha. At that time, it was regarded as a minor, insignificant event over there, on the borders of the empire, in Asia. And it is fair to say that what took place around the first third of the 15th century was just as little noticed by the civilized world as far as external documentary historical records are concerned. But it has certainly left its mark on human striving and human struggle.

[ 3 ] We have already noted some of this again recently, for example, the way it played out in Calderón's poetry in “Magus Cyprianus,” how this spiritual upheaval in humanity was perceived in Spain in particular. Now, however, we can see how, at various points in human development, even if things are not expressed in the way they must be expressed today from an anthroposophical perspective, there is nevertheless a more energetic sense that we must, in a sense, become clear within ourselves about this shift that has taken place. I have already pointed out that Goethe's Faust is one of the attempts to gain clarity about this shift through human struggle. But perhaps more light will be shed on Goethe's Faust when it is placed in a larger world context. Just as Faust stands before us in Goethe's poetry as a spiritual phenomenon, initially isolated, we can characterize him in the following way:

[ 4 ] Goethe, in his youthful aspirations, which were naturally inspired by the intellectual climate of Europe, first came to dramatize the human struggle within the emerging intellectualism. From his acquaintance with the medieval Faust figure, from folk plays and the like, the personality of Faust presents itself to his soul as a representative of those struggling personalities who lived in that age. Faust belongs to the 16th century, not the 15th, but one could say that this change did not take place in a single year, nor even in a single century, but rather spread out over the centuries. So Goethe encountered the figure of Faust as a personality who lives within this whole struggle, from an earlier time into a later time. And one can actually see how clear Goethe is about the special nature of this struggle from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period. We see how he initially presents Faust as a scholar who knows all four faculties, who has let them work on him, who has thus absorbed into his soul the impulses that come from intellectualism, from intellectualistic scholarship, and who also feels the human dissatisfaction of remaining stuck in one-sided intellectualism. Faust turns away from this intellectualism, as you know, and turns to magic in his own way. One must only realize what that actually means in this case. What Faust went through “in philosophy, law, medicine, and unfortunately also theology” is what one can go through in intellectualized scholarship. This leaves one unsatisfied at first. It leaves one unsatisfied because the form of abstraction through which this scientific approach speaks appeals only to one part of the human being, the head, if we want to use that expression, and actually disregards the rest of the human being.

[ 5 ] One need only compare how different it was in a previous era. It is usually overlooked that things were quite different in a previous era. Those people who wanted to advance in their knowledge of life and the world did not turn to intellectual concepts, but sought to see spiritual realities, spiritual essences behind the sensory phenomena of the environment. This is what is so difficult to understand: that personalities striving for knowledge in the 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries did not seek mere conceptual connections, but rather spiritual, essential reality, that which could be seen behind the sensory phenomena, not that which can merely be thought in the sensory phenomena.

[ 6 ] But this transition is based precisely on the fact that what had previously been sought was, in a sense, relegated to the realm of superstition, that the inclination to search for such real spiritual entities was lost, and that intellectual connections were considered the only possible, truly scientific explanation. But as much as one might logically say on the one hand that only those concepts and ideas that the intellect derives from sensory reality are not superstitious, the whole human being, especially the human mind, could not be satisfied with what it ultimately found in these concepts and ideas. And so Goethe's Faust finds himself in a position of dissatisfaction with intellectualism and turns back to what he still knows of magic.

[ 7 ] This mood was one that was entirely genuine and honest in Goethe. Goethe, too, had studied a wide variety of sciences at the University of Leipzig. And before he found a certain contemplative depth in Strasbourg with Herder, he tried—actually also in a departure from the intellectualism he had encountered in Leipzig—to turn, for example, in association with Susanne von Klettenberg and through the study of relevant works, to the field that he then called magic in Faust. This was very much Goethe's own path. It was only when Goethe found Herder during his further studies in Strasbourg that he encountered a mind that was itself averse to intellectualism. Herder was by no means an intellectual man – hence his anti-Kantianism – who then, in a certain way, without the magic, led Goethe beyond what he had previously attempted to achieve out of a truly Faustian mood, drawing on the old magic.

[ 8 ] This is how Goethe actually viewed this Faust of the 16th century — one might just as well say: the scholar of the 15th century who grows out of magic but is still half in it — in that he wanted to portray Goethe wanted to portray his own deepest inner struggle as it presented itself to him, because the traces of the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period were still very much at work within him.

[ 9 ] It is probably one of the most interesting points of recent intellectual development that Goethe, in wanting to express his own youthful struggles, turned to the professor of the 15th and 16th centuries in order to dramatically characterize his own inner soul life and soul experience in this form. Of course, one completely misunderstands both what lived in Goethe and what was present in the 15th and 16th centuries as the great upheaval when one says with Du Bois-Reymond that Goethe made a great mistake in portraying his Faust as he did; he should have made him completely different. Faust might indeed have had to be dissatisfied with what tradition could offer him. But if Goethe had been able to portray Faust properly, then after going through the first scenes, Faust would have made Gretchen honest, married her, and become a well-established professor who invented the electric machine and the air pump. That is Du Bois-Reymond's view of how Faust should actually have turned out.