Old and New Methods of Initiation

GA 210

26 February 1922, Dornach

Lecture XIII

The two previous lectures were devoted to considerations intended to show how that tremendous change, which entered into the whole soul constitution of civilized mankind with the fifteenth century—that is, with the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period—continued to have an effect on outstanding personalities. Let me introduce today's lecture with a brief summary of these preceding considerations. I showed how intensely a personality such as Goethe sensed the continuing vibrations of the great change, how he sensed that it was a concrete experience to find intellectual reasoning entering into the human soul. He sensed that it was necessary to come to terms with the intellectual element of the soul and he also had an inkling of the direct intercourse between human beings and the spiritual world which had preceded this intellectual stage. Even though it was no longer as it had been in the days of ancient atavistic clairvoyance, there was nevertheless a kind of looking back to the time when human beings knew that it was only possible for them to find real knowledge if they stepped outside the world of the senses in order to see in some way the spiritual beings who existed behind the sense-perceptible world.

Goethe invested the figure of his Faust with all these things sensed in his soul. We saw how dissatisfied Faust is by stark intellectualism as presented to him in the four academic faculties:

I've studied now Philosophy

And Jurisprudence, Medicine,

And even, alas! Theology,

From end to end ...

He is saying in different words: I have loaded my soul with the whole complexity of intellectual science and here I now stand filled with the utmost doubt; that is why I have devoted myself to magic.

Because of dissatisfaction with the intellectual sciences, Goethe invests the Faust figure with a desire to return to intercourse with the spiritual world. This was quite clear in his soul when he was young, and he wanted to express it in the figure of Faust. He chose the Faust figure to represent his own soul struggles. I said that although this is not the case with the historical Faust of the legend, we could nevertheless find in Goethe's depiction of Faust that professor who might have taught at Wittenberg in the sixteenth or even in the seventeenth century, and who had, ‘Straight or crosswise, wrong or right’, led his scholars by the nose ‘these ten years long’. This hypothesis allows us to see how in this educational process there was a mixture of the new intellectualism with something pointing back to ancient days when intercourse with the spiritual world and with the spiritual powers of creation was still possible for human beings.

I then asked whether—apart from what is given us in the Faust drama—we might also, in the wider environment, come up against the effects of what someone like Faust could have taught in the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth centuries. And here we hit upon Hamlet, about whom it could be said: The character which Shakespeare created out of Hamlet—who in his turn he had taken from Danish mythology and transformed—could have been a pupil of Faust, one of those very students whom Faust had led by the nose ‘these ten years long’. We see Hamlet interacting with the spiritual world. His task is given to him by the spiritual world, but he is constantly prevented from fulfilling it by the qualities he has acquired as a result of his intellectual education. In Hamlet, too, we see the whole transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period.

Further, I said that in the whole mood and artistic form of Shakespeare's plays, that is, in the historical plays, we could find in the creativity of the writer of Shakespeare's plays the twilit mood of that time of transition. Then I drew your attention to the way in which Goethe and Schiller in Central Europe had stood in their whole life of soul within the dying vibrations of the transition, yet had lacked, in a certain sense, the will to accept what the intellectual view of the world had since then brought about in the life of human beings. This led them back to Shakespeare, for in his work—Hamlet, Macbeth and so on—they discovered the capacity to approach the spiritual world; from his vantage point, they could see into the world of spiritual powers which was now hidden from the intellectual viewpoint.

Goethe did this in his Götz von Berlichingen by taking the side of the dying echoes of the old time of the fourth post-Atlantean period and by rejecting what had come into being through intellectualism. Schiller, in the dramas of his youth, especially in Die Räuber (The Robbers), goes back to that time—not by pointing to the super-sensible world, but by endeavouring to be entirely realistic, yet putting into the very words characterizing Karl Moor something which echoes the luciferic element that is also at work in Milton's Paradise Lost.1 John Milton, 1608-1674. English poet and puritan politician. His epic poem Paradise Lost was finished by 1665. In short, despite his realism, we detect a kind of return to a conception of reality which allows the spiritual forces and powers to shine through.

I indicated further that, in the West, Shakespeare was in a position—if I may put it like this—to work artistically in full harmony with his social environment. Hamlet is the play most characteristic of Shakespeare. Here the action is everywhere quite close to the spiritual world, as it is also in Macbeth. In King Lear, for instance, we see how he brings the super-sensible world more into the human personality, into an abnormal form of the human personality, the element of madness. Then, in the historical dramas about the kings, he goes over more into realism but, at the same time, we see in these plays a unique depiction of a long drawn-out dramatic evolution influenced everywhere by the forces of destiny, but culminating and coming to an end in the age of Queen Elizabeth.

The thing that is at work in Shakespeare's plays is a retrospective view of older ages leading up to the time in which he lives, a time which is seen to be accepted by him. Everything belonging to older times is depicted artistically in a way which leads to an understanding of the time in which he lives. You could say that Shakespeare portrays the past. But he portrays it in such a way that he places himself in his contemporary western social environment, which he shows to be a time in which things can take the course which they are prone to take. We see a certain satisfaction with regard to what has come about in the external world. The intellectualism of the social order is accepted by the person belonging to the external, physical earthly world, by the social human being, whereas the artistic human being in Shakespeare goes back to earlier times and portrays that aspect of the super-sensible world which has created pure intellectualism.

Then we see that in Central Europe this becomes an impossibility. Goethe and Schiller, and before them Lessing, cannot place themselves within the social order in a way which enables them to accept it. They all look back to Shakespeare, but to that Shakespeare who himself went back into the past. They want the past to lead to something different from the present time in which they find themselves. Shakespeare is in a way satisfied with his environment; but they are dissatisfied with theirs.

Out of this mood of spiritual revolution Goethe creates the drama of Götz von Berlichingen, and Schiller the dramas of his youth. We see how the external reality of the world is criticized, and how in the artistic realm there is an ebbing and flowing of something that can only be achieved in ideas, something that can only be achieved in the spirit. Therefore we can say: In Goethe and Schiller there is no acceptance of the present time. They have to comfort themselves, so far as external sense-perceptible reality is concerned, with what works down out of the spiritual world. Shakespeare in a way brings the super-sensible world down into the sense-perceptible world. Goethe and Schiller can only accept the sense-perceptible world by constantly turning their attention to the spiritual world. In the dramas of Goethe and Schiller we have a working together of the spiritual with the physical—basically, an unresolved disharmony. I then said that if we were to go further eastwards we would find that there is nothing on the earth that is spiritual. The East of Europe has not created anything into which the spirit plays. The East flees from the external working of the world and seeks salvation in the spirit above.

I was able to clothe all this in an Imagination by saying to you: Let us imagine Faust as Hamlet's teacher, a professor in Wittenberg. Hamlet sits at his feet and listens to him, after which he returns to the West and accustoms himself once again to the western way of life. But if we were to seek a being who could have gone to the East, we should have had to look for an angel who had listened to Faust from the spiritual world before going eastwards. Whatever he then did there would not have resembled the deeds and actions of Hamlet on the physical plane but would have taken place above human beings, in the spiritual world.

Yesterday, I then described how, out of this mood, at the time when he was making the acquaintance of Schiller, Goethe felt impelled to bring the being of man closer to the spiritual world. He could not do this theoretically, in the way Schiller, the philosopher, was able to do in his aesthetic letters, but instead he was urged to enter the realm of Imagination and write the fairy-tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily. Then Schiller felt the urge to bring the external reality of human life closer to the spirit—I might say experimentally—in Wallenstein (Wallenstein's Camp), by letting a belief in the stars hold sway like a force of destiny over the personality of Wallenstein, and in Die Braut von Messina (Bride of Messina) by letting a destiny run its course virtually entwined with a belief in the stars. These personalities were impelled ever and again to turn back to the time when human beings still had direct intercourse with the spiritual world.

Further, I said that Goethe and Schiller lived at a time when it was not yet possible to find a new entry into the spiritual world from out of a modern soul constitution. Schiller in particular, with his philosophical bent, had he lived longer and finished the drama about the Knights of Malta, would have come to an understanding of how, in an order like this, or like that of the Templars, the spiritual worlds worked together with the deeds of human beings. But it was not granted to Schiller to give the world the finished drama about the Knights of Malta, for he died too soon. Goethe, on the other hand, was unable to advance to a real grasp of the spiritual world, so he turned back. We have to say that Goethe went back to Catholic symbolism, the Catholic cultus, the cultus of the image, though he did so in an essentially metamorphosed form. We cannot help but be reminded of the good nun Hrosvitha's legend of Theophilus2 Lecture Twelve, Note 7 from the ninth century, when Goethe in his turn allows Faust to be redeemed in the midst of a Christianizing tableau. Although his genius lets him present it in a magnificently grand and artistic manner, we cannot but be reminded, in ‘The Eternal Feminine bears us aloft’, of the Virgin Mary elevating the ninth-century Theophilus.

An understanding of these things gives us deep insight into the struggle within intellectualism, the struggle in intellectualism which causes human beings to experience inwardly the thought-corpse of what man is before descending through birth—or, rather, through conception—into his physical life on earth. The thoughts which live in us are nothing but corpses of the spirit unless we make them fruitful through the knowledge given by spiritual science. Whatever we are, spiritually, up to the moment when earthly life begins, dies as it enters our body, and we bear its corpse within us. It is our earthly power of thought, the power of thought of our ordinary consciousness.

How can something that is dead in the spiritual sense be brought back to life? This was the great question which lived in the souls of Goethe and Schiller. They do not bring it to expression philosophically but they sense it within their feeling life. And they compose their works accordingly. They have the feeling: Something is dead if we remain within the realm of the intellect alone; we must bring it to life. It is this feeling which makes them struggle to return to a belief in the stars and to all sorts of other things, in order to bring a spiritual element into what they are trying to depict. It is necessary for us to be aware of how the course of world evolution is made manifest in such outstanding personalities, how it streams into their souls and becomes the stuff of their struggles. We cannot comprehend our present time unless we see that what this present time must strive for—a new achievement of the spiritual world—is the very problem which was of such concern for Goethe and Schiller.

What happened as a result of the great transition which took place in the fifteenth century was something of which absolutely no account is taken in ordinary history. It was, that the human being acquired an entirely different attitude towards himself. But we must not endeavour to capture this in theoretical concepts. We must endeavour to trace it in what human beings sensed; we must find out how it went through a preparation and how it later ran its course after the great change had been fulfilled in its essential spiritual force.

There are pointers to these things at crucial points in cultural evolution. See how this comes towards us in Wolfram von Eschenbach's Parzival.3 Wolfram von Eschenbach, c.1170-1220. One of the greatest medieval German poets. Parzival was probably written between 1200 and 1210. You all know the story. You know how crucial it was for the whole of Parzival's development that he first of all received instruction from a kind of teacher as to how he was to go through the world without asking too many questions. As a representative of that older world order which still saw human beings as having direct intercourse with the spiritual world, Gurnemanz says to Parzival: Do not ask questions, for questioning comes from the intellect, and the spiritual world flees from the intellect; if you want to approach the spiritual world you must not ask questions.

But times have changed and the transition begins to take place. It is announced in advance: Even though Parzival goes back several more centuries, into the seventh or eighth century, all this was nevertheless experienced in advance in the Grail temple. Here, in a way, the institutions of the future are already installed, and one of them is that questions must be asked. The essential point is that with the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period the situation of the human being changes. Previously it was inappropriate to ask questions because conditions held sway about which Goethe speaks so paradoxically:

The lofty might

Of Science, still

From all men deeply hidden!

Who takes no thought,

To him 'tis brought,

'Tis given unsought, unbidden!

In those times it was right not to ask questions, for that would have driven away the spirits! But in the age of the intellect the spiritual world has to be rediscovered through the intellect and not by damping down the processes of thought. The opposite must now come into play; questions must be asked. As early as Parzival we find a portrayal of the great change which brings it about in the fifth post-Atlantean period that the longing for the spiritual world now has to be born out of the human being in the form of questions to be formulated.

But there is also something else, something very remarkable, which comes to meet us in Parzival. I should like to describe it as follows. The languages which exist today are far removed from their origins, for they have developed as time has gone on. When we speak today—as I have so often shown—the various combinations of sounds no longer remind us of whatever these combinations of sounds denote. We now have to acquire a more delicate sense for language in order to experience in it all the things that it signifies. This was not the case where the original languages of the human race were concerned. In those days it was known that the combination of sounds itself contained whatever was experienced in connection with the thing depicted by those sounds. Nowadays poets seek to imitate this. Think, for instance, of ‘Und es wallet und siedet und brauset und zischt’.4 #8216;And it bubbles and seethes, and it hisses and roars’, Der Taucher by Friedrich von Schiller, translated by E. Bulwer Lytton in The Poems and Ballads of Schiller, Leipzig 1844. Poetic language has here imitated something of what the poet wants us to see externally. But this is mere derived imitation. In olden times every single sound in language was felt to have the most intimate connection with what was happening all around. Today only some local dialects can lay claim to giving us some sense for the connection between external reality and the words spoken in dialect. However, language is still very close to our soul—it is a special element in our soul.

It is another consequence of the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period that this has become deposited as something very deeply sensed within the human soul, again a fact which is left out of account by both philology and history. The fact that in the fourth post-Atlantean period human beings lived more within their language and that in the fifth post-Atlantean period this is no longer the case, brings about a different attitude by human beings towards the world. You can understand that human beings with their ego are linked quite differently to what is going on around them if, in using language, they go along with all the rushing of waves, the thundering and lightning, and whatever else is happening out there. This becomes ever more detached as the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period progresses. The ego becomes more inward, and language together with the ego also becomes more inward, but at the same time less meaningful as regards external matters. Such things are most certainly not perceived by the knowledge of today, which has become so intellectual. There is hardly any concern to describe such things. But if what is taking place in mankind is to be correctly understood, they will have to be described.

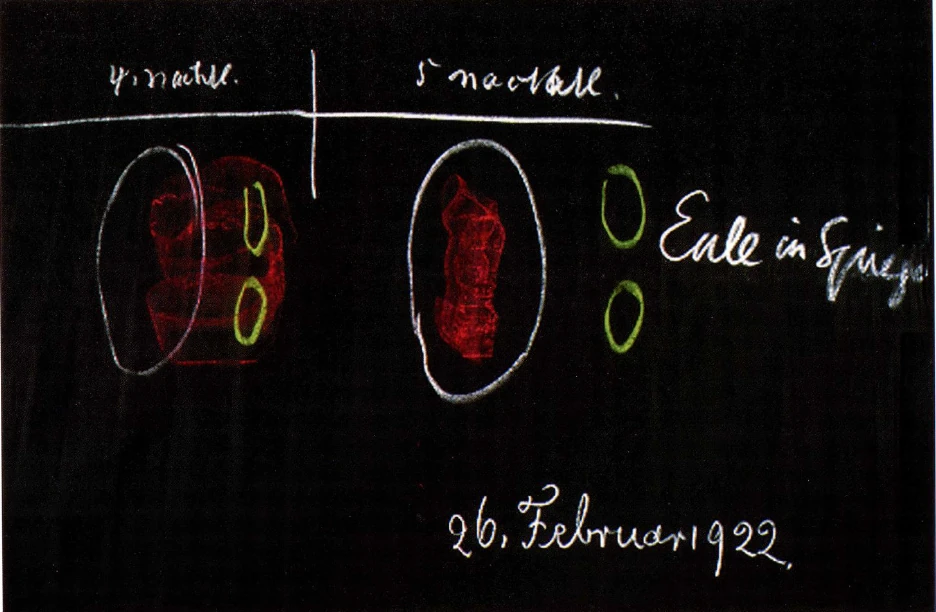

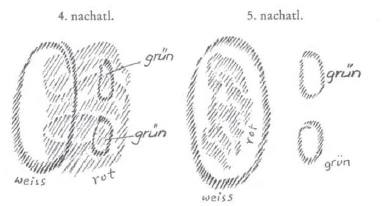

Imagine what can come into being. Imagine vividly to yourselves, here the fourth post-Atlantean period, and here the fifth. The transition is of course gradual, but for the sake of explanation I shall have to talk in extremes. In the fourth post-Atlantean period you have here the things of the world (green). The human being with his words, depicted within him, here in red, is still connected with the things. You could say he 'lives over' into the things through the medium of his words. In the fifth post-Atlantean period the human being possesses his words within his soul, separated off from the world.

Imagine this clearly, even almost in grotesque detail. Looking at the human being here in the fourth post-Atlantean period, you might say of him that he still lives with the things. The things he does in the outside world will proceed to take place in accordance with his words. If you see one of these human beings performing a deed, and if at the same time you hear how he describes the deed, there is a harmony between the two. Just as his words are in harmony with external things, so are his deeds in harmony with the words he speaks. But if a human being in the fifth post-Atlantean period speaks, you can no longer detect that his words resound in what he does. What connection with the deed can you find today in the words: I have chopped wood! In what is taking place out there in the activity of chopping we can no longer sense in any way a connection with the movement of the chopper. As a result, the connection with the sounds of the words gradually disappears; they cease to be in harmony with what is going on outside. We no longer find any connection between the two. So then, if someone listens pedantically to the words and actually does

what lies in the words, the situation is quite different. Someone might say: I bake mice. But if someone were actually to bake mice, this would seem grotesque and would not be understood.

This was sensed, and so it was said: People ought to consider what they actually have in their soul in conjunction with what they do externally; the relationship between the two would be like an owl looking in a mirror! If someone were to do exactly what the words say, it would be like holding up a mirror to an owl. Out of this, in the second half of the fourteenth century, Till Eulenspiegel arose.5 Till Eulenspiegel, a popular German peasant jester, was supposed to have died in Winn in 1350. The first extant text of the chapbook in High German chronicling his escapades was published in 1515. The name ‘Eulenspieger means, literally, ‘owl's mirror’. (Tr.) The owl's mirror is held up in front of mankind. It is not Till Eulenspiegel who has to look in the mirror. But because Till Eulenspiegel takes literally what people say with their dry, abstract words, they suddenly see themselves, whereas normally they do not see themselves at all. It is a mirror for the owls because they can really see themselves in it.

Night has fallen. In past times, human beings could see into the spiritual world. And the activity of their words was in harmony with the world. Human beings were eagles. But now they have become owls. The world of the soul has become a bird of the night. In the strange world depicted by Till Eulenspiegel, a mirror is held up before the owl.

This is quite a feasible way of regarding what appears in the spiritual world. Things do have their hidden reasons. If we fail to take note of the spiritual background, we also fail to understand history, and with it the chief factor in humanity today. It is especially important to depart from the usual external characterization of everything. Look in any dictionary and see what absurd explanations are given for Eulenspiegel! He cannot be understood without entering into the whole process of cultural and spiritual life. The important thing in spiritual science is to actually discover the spirit in things, not in a way that entails a conceptual knowledge of a few spiritual beings who exist outside the sense-perceptible world, but in a way which leads us to an ability to see reality with spiritual eyes.

The change which took place, between the time when human beings felt themselves to be close to the spiritual world and the later time when they felt as though they had been expelled from that world, can be seen in other areas too. Try to develop a sense for the profound impulse which runs through something like the Parzival epic. See how Parzival's mother dresses him in a simpleton's clothes because she does not want him to grow up into the world which represents the new world. She wants him to remain in the old world. But then he grows up from the sense-perceptible world into the world of the spirit.

The seventeenth century also possesses a kind of Parzival, a comical Parzival, in which everything is steeped in comedy. In the intellectualistic age, if one is honest, one cannot immediately muster the serious attitude of soul which prevails in Parzival. But the seventeenth century too, after the great change had taken place, had its own depiction of a character who has to set out into the world, lose himself in it, finally ending-up in solitude and finding the salvation of his soul. This is Christoffel von Grimmelshausen's Simplicissimus.6 Christoffel von Grimmelshausen, d.1676. German writer. Simplicissimus, published in 1669, is said to be the greatest German novel of the seventeenth century. Look at the whole process of the story. Of course you must take the whole tone into account, on the one hand the pure, perhaps holy mood of Parzival, and on the other the picaresque, comical mood. Consider Simplicissimus, the son of well-to-do peasants in the Spessart region. In the Thirty Years’ War their house is burnt down. The son has to flee, and finds his way to a hermit in the forest who teaches him all kinds of things, but who then dies. So here he is, abandoned in the world and having to set off on his travels. He becomes immersed in all the events and blows of fate offered by the Thirty Years’ War. He arrives at the court of the governor of Hanau. Externally he has learnt nothing, externally he is a pure simpleton; yet he is an inwardly mature person for all that. But because externally he is a pure simpleton the governor of Hanau says to himself: This is a simpleton, he knows nothing; he is Simplicissimus, as naive as can be. What shall I train him to be? I shall train him to be my court fool.

But now the external and the internal human being are drawn apart. The ego has become independent in respect of the external human being. It is just this that is shown in Simplicissimus. The external human being in the external world, trained to be the court fool, is the one who is considered by all and sundry to be a fool. But in his inner being Simplicissimus in his turn considers all those who take him for a fool to be fools themselves. For although he has not learnt a thing, he is nevertheless far cleverer than all those who have made him into a fool. He brings out of himself the other intellectuality, the intellectuality that comes from the spirit, whereas what comes to meet him from outside is the intellectuality that comes from reasoning alone. So the intellectualists take him for a fool, and the fool brings his intellectualism from the spiritual world and holds those who take him for a fool to be fools themselves. Then he is taken prisoner by some Croats, after which he roams about the world undergoing many adventures, until finally he ends up once more at the hermitage where he settles down to live for the salvation of his soul.

The similarity between Simplicissimus and Parzival has been recognized, but the crucial thing is the difference in mood. What in Parzival's case was still steeped in the mind-soul has now risen up into the consciousness soul. Now caustic wit is at work, for the comical can only have its origin in caustic wit. If you have a feel for this change of mood, you will be able to discover—especially in works which have a broader base than that of a single individuality—what was going on in human evolution. And Christoffel von Grimmelshausen did indeed secrete in Simplicissimus the whole mood, the whole habit of thought of his time. Similarly you can in a way find the people as a whole composing stories, and gathering together all the things which the soul, in the guise of an owl, can see in the mirror, and which become all the tall tales found in Till Eulenspiegel.

It would be a good thing, once in a while, to go in more detail into all these things, not only in order to characterize the various interconnections. I can only give you isolated examples. To say everything that could be said I should have to speak for years. But this is not really what matters. What is crucial is to come closer to a more spiritual conception of these things. We have to learn to know how things which are presented to us purely externally are also connected with the spirit. So we may say: That tremendous change which took place in the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period can be seen everywhere, vibrating through the cultural and spiritual evolution of mankind. As soon as you step back a bit from this turning- point of time, you come to see how all the different phenomena point to the magnititude of the change.

Only by taking the interconnections into account is it possible to understand what lies hidden in the figures brought by spiritual and cultural life out of the past and into the present. Take Lohengrin, the son of Parzival. What does it mean that Elsa is forbidden to ask after his name and origin? People simply accept this. Not enough deep thought is given to the question as to why she is forbidden to ask, for usually there are two sides to everything. Certainly this could also be described differently, but one important aspect may be stated as follows: Lohengrin is an ambassador of the Grail; he is Parzival's son. Now what actually is the Grail community? Those who knew the mystery of the Grail did not look on the Grail temple as a place solely for the chosen knights of the Grail. They saw that all those who were pure in heart and Christian in the true sense went to the Grail while they slept—while they were between sleeping and waking. The Grail was seen as the place where all truly Christian souls gathered while they slept at night. There was a desire to be apart from the earth. So those who were the rulers of the Grail also had to be apart from earthly life. Lohengrin, the son of Parzival, was one of these. Those who desired to work in accordance with the Grail impulse had to feel themselves entirely within the spiritual world. They had to feel that they belonged entirely to the spiritual world and certainly not at all to the earthly world. In a certain sense you could say that they had to drink the draught of forgetfulness.

Lohengrin is sent down from the Grail castle. He unites with Elsa of Brabant, that is with the people of Brabant. In the train of Heinrich I he sets out to fight the Hungarians. In other words, at the instigation of the Grail he carries out important impulses of world history. The strength he has from the Grail temple enables him to do this. When we go back to the fourth post-Atlantean period we find that all these things are different. In those days spiritual impulses played their part together with external impulses that could be comprehended by the intellect. This is hardly noticeable in the way history is told today.

We speak quite rightly today of meditative formulae, simple sentences which work in the human being's consciousness through their very simplicity. How many people today understand what is meant when history tells us that those required to take part in the Crusades—they took place in the fourth post-Atlantean period—were provided with the meditative formula ‘God wills it’ and that this formula worked on them with spiritual force. ‘God wills it’ was a kind of social meditation. Keep a look out for such things in history; you will find many! You will find the origins of the old mottos. You will discover how the ancient titled families set out on conquering expeditions under such mottos, thus working with spiritual means, with spiritual weapons. The most significant spiritual weapons of all were used by knights of the Grail, such as Lohengrin. But he was only able to use them if he was not met with recollections of his external origins, his external name, his external family. He had to transport himself into a realm in which he could be entirely devoted to the spiritual world and in which his intercourse with the external world was limited to what he perceived with his senses, devoid of any memories. He had to accomplish his deeds under the influence of the draught of forgetfulness. He was not allowed to be reminded. His soul was not permitted to remember: This is my name and I am a scion of this or that family. So this is why Elsa of Brabant is not allowed to question him. When she does, he is forced to remember. The effect on his deeds is the same as if his sword had been smashed.

If we go back beyond the time when everything became intellectual, so that people also clothed what had gone before in intellectual concepts, imagining that everything had always been as they knew it—if we go back beyond what belongs to the age of the intellect, we find the spiritual realm working everywhere in the social realm. People took the spiritual element into account, for instance, in that they took moral matters just as much into account as physical medicines.

In the age of the intellect, in which all people belong only to the intellect, whatever would they think if they found that moral elements, too, were available at the chemist's! Yet we need only go back a few centuries prior to the great change. Read Der arme Heinrich by Hartmann von Aue,7 Hartmann von Aue, c.1170-1213. Middle High German poet. Der arme Heinrich (Poor Henry). who was a contemporary of Wolfram von Eschenbach. Before you stands a knight, a rich knight, who has turned away from God, who in his soul has lost his links with the spiritual world, and who thus experiences this moment of atheism which has come over him as a physical illness, a kind of leprosy. Everyone avoids him. No physician can cure him. Then he meets a clever doctor in Salerno who tells him that no physical medicine can do him any good. His only hope of a cure lies in finding a pure virgin who is prepared to be slain for his sake. The blood of a pure virgin can cure him of his illness. He sells all his possessions and lives alone on a smallholding cared for by the tenant farmer. The farmer has a daughter. She falls in love with the leprous knight, discovers what it is that alone can cure him, and decides to die for him. He goes with her to the doctor in Salerno. But then he starts to pity her, preferring to keep his illness rather than accept her sacrifice. But even her willingness to make the sacrifice is enough. Gradually he is healed.

We see how the spirit works into cultural life, we see how moral impulses heal and were regarded as healing influences. Today the only interpretation is: Ah, well, perhaps it was a coincidence, or maybe it is just a tale. Whatever we think of individual incidents, we cannot but point out that, during the time which preceded the fifteenth century, soul could work on soul much more strongly than was the case later; what a soul thought and felt and willed worked on other souls. The social separation between one human being and another is a phenomenon of intellectualism. The more intellectualism flourishes and the less an effort is made to find what can work against it—namely the spiritual element—the more will this intellectualism divide one individuality from another.

This had to come about; individualism is necessary. But social life must be found out of individualism. Otherwise, in the ‘social age’ all people will do is be unsociable and cry out for Socialism. The main reason for the cry for Socialism is that people are unsocial in the depths of their soul. We must take note of the social element as it comes towards us in works such as Hartmann von Aue's Der arme Heinrich. It makes its appearance in cultural works in which it can be sensed quite clearly through the mood. See how different is the mood in Der arme Heinrich. You cannot call it sentimental, for sentimentality only arose later when people found an unnatural escape from intellectualism. The mood is in a way pious; it is a mood of spirituality. To be honest about the same matters in a later age you have to fall back on the element of comedy. You have to tell your story as Christoffel von Grimmelshausen did in Simplicissimus, or as the people as a whole did in Till Eulenspiegel.

This sense of having been thrown out of the world is found everywhere, not only in poetic works arising out of the folk element. Wherever it appears, you find that what is being depicted is a new attitude of the human being towards himself. From an entirely new standpoint he asks: What am I, if I am a human being? This vibrates through everything. So from the new intellectual standpoint the question is asked over and over again: What is the human being? In earlier times people turned to the spiritual world. They truly sought what Faust later seeks in vain. They turned to the spiritual world when they wanted to know: What actually is the human being? They knew that outside this physical life on earth the human being is a spirit. So if he wants to discover his true being, which lives in him also in physical, earthly life, then he will have to turn to the spiritual world. Yet more and more human beings are failing to do this very thing.

In Faust Goethe still hints: If I want to know the spirit, I must turn to the spiritual world. But it does not work. The Earth Spirit appears, but Faust cannot recognize it with his ordinary knowledge. The Earth Spirit says to him: ‘Thou'rt like the Spirit which thou comprehendest, not me!’8 ‘Thou'rt like the spirit’: Faust Part One. The Study. Faust has to turn away and speak to Wagner. In Wagner he then sees the spirit which he comprehends. Faust, ‘image of the Godhead’, cannot comprehend the Earth Spirit. So Goethe still lived in an age which strove to find the being of man out of the spiritual world. You see what came once Goethe had died. Once again people wanted to know what the human being is, this time on the basis of intellectualism. Follow the thread: People cannot turn to the spiritual world in order to discover what the human being is. In themselves, equally, they fail to find the answer, for language has meanwhile become an owl in the soul. So they turned to those who depicted olden times at least in an external fashion. What do we find in the nineteenth century?9 Jerennas Gotthelf (A. Bitzius), 1797-1854; Karl Immermann, 1796-1840; George Sand (A.A.L. Dupin-Dudevant), 1804-1876; D.W. Grigorovich, 1818-1883; I.S. Turgeniev, 1818-1883. In 1836 Jeremias Gotthelf: Bauernspiegel; in 1839 Immermann: Oberhof, Die drei Mahlen, Schwarzwalder Bauern geschichten; George Sand: La Petite Fadette; in 1847 Grigorovich: Unhappy Anthony; in 1847-51 Turgeniev: Sportsman's Sketches.

We have here the longing to find in simple people the answer to the question: What is the human being? In olden times you turned to the spiritual world. Now you turned to the peasant. During the course of two decades the whole world develops a longing to write village stories in order to study the human being. Because people cannot recognize themselves, at best looking in the mirror as if they are owls, they turn to simple folk instead. What they can prove in every detail, from Jeremias Gotthelf to Turgeniev, is that everything is striving to get to know the human being. In all these village stories, in all these simple tales, the unconscious endeavour is to achieve a knowledge of man. From this kind of viewpoint spiritual and cultural life can become comprehensible.

This is what I wanted to show you in these three lectures, in order to illustrate the transition from the fourth to the fifth post-Atlantean period. It is not enough to describe this transition with a few abstract concepts—which is what was naturally done at first. Our task is to illumine the whole of reality with the light of the spirit through Anthroposophy. These lectures have been an example of this.

Das Suchen des Zugangs zur geistigen Welt aus der modernen Seelenverfassung heraus

[ 1 ] Die beiden vorangehenden Vorträge waren Betrachtungen gewidmet, die darauf hinweisen sollten, wie jener gewaltige Umschwung, der in der ganzen Seelenverfassung der zivilisierten Menschheit mit dem 15. Jahrhundert eingetreten ist, also mit dem Übergange von dem vierten nach dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum, nachgewirkt hat in bedeutenden Persönlichkeiten. Und ich darf vielleicht das, was ich in diesen beiden Betrachtungen ausgeführt habe, mit wenigen Worten einleitend heute noch einmal skizzieren. Ich habe darauf hingewiesen, wie intensiv eine Persönlichkeit wie Goethe das Nachzittern jenes Umschwunges fühlte, wie er fühlte, als sicheres Erlebnis zieht jetzt in die menschliche Seele das Verstandesmäßige, das Intellektualistische ein; wie er fühlte, man muß zurechtkommen in der Seele mit diesem Intellektualistischen, und wie er noch gewisse Ahnungen davon hatte, daß diesem Intellektualistischen vorangegangen ist ein unmittelbarer Verkehr des Menschen mit der geistigen Welt. Wenn es auch nicht so war wie in den Zeiten des alten atavistischen Hellsehens, war immerhin vorhanden eine Art Rückblick auf die Zeit, in welcher die Menschen noch, wenn sie von Erkenntnis sprachen, sich bewußt waren, daß eine solche Erkenntnis nur möglich ist, wenn man gewissermaßen aus der Welt der Sinne wegtritt, um die hinter der Sinneswelt befindlichen geistigen Wesenheiten irgendwie zu schauen.

[ 2 ] Goethe hat diese ganze Empfindungswelt seiner Seele in seine Faust-Figur gelegt. Wir sehen, wie Faust unbefriedigt ist von dem bloßen Intellektualismus, der ihm entgegengetreten ist in den vier Fakultäten:

Habe nun, ach! Philosophie,

Juristerei und Medizin,

Und, leider, auch Theologie!

Durchaus studiert ...

[ 3 ] Das heißt: Habe den ganzen Komplex des intellektualistischen Wissens auf meine Seele geladen und stehe nun mit dem vollständigsten Zweifel da; drum hab’ ich mich der Magie ergeben.

[ 4 ] Also Goethe legt in diese Faust-Gestalt das Zurückgehen zu dem Verkehr mit der geistigen: Welt hinein wegen der Unbefriedigtheit in den intellektualistischen Wissenschaften. Das stand dem jungen Goethe ganz deutlich vor der Seele, das wollte er in seiner Faust-Figur zum Ausdrucke bringen. Und indem er dieses, sein eigenes Seelenringen, darstellen wollte, griff er dazu, als Repräsentanten dafür eben die Faust-Gestalt zu nehmen. Und ich sagte, wenn das auch bei dem historischen, mythologischen Faust nicht der Fall ist, in bezug auf das, was Goethe geschildert hat, können wir uns den Faust vorstellen als den Professor, der etwa im 16. oder auch im 17. Jahrhundert in Wittenberg gelehrt haben könnte, und der ja «an die zehen Jahr» seine Schüler kreuz und quer und grad und krumm an der Nase herumgeführt hat. Und man kann schon hinschauen, wenn man einmal diese Hypothese aufstellt, wie es da in diesem Bildungsgange ausgesehen hat, wie da vermischt war das neue Intellektualistische mit dem, was noch hinwies in die alten Zeiten, wo noch der Verkehr mit der geistigen Welt und mit den geistigen schöpferkräften für den Menschen möglich war.

[ 5 ] Nun fragte ich, ob wir außer dem, was uns in der Faust-Dichtung vorgeführt wird, etwa im weiteren Umkreis auf Wirkungen stoßen können von dem, was so jemand wie Faust gelehrt haben könnte im 15., 16., 17. Jahrhundert. Und da stießen wir denn auf Hamlet und konnten sagen: Die Gestalt, die Shakespeare aus dem Hamlet gemacht hat - den er seinerseits wiederum aus den dänischen Sagen genommen, aber umgestaltet hat —, diese Gestalt des Hamlet erscheint uns als der Schüler des Faust, als einer derjenigen, die gerade eben von solchen Persönlichkeiten, wie der Faust war, die zehn Jahre an der Nase herumgezogen worden waren. Wir sehen dann diesen Hamlet, wie er selber hineingestellt ist in den Verkehr mit der geistigen Welt, wie ihm sein Auftrag wird aus der geistigen Welt heraus, wie er fortwährend aber gestört wird durch das, was er sich durch die intellektualistische Bildung angeeignet hat. Kurz, wir sehen gewissermaßen den ganzen Übergang vom vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum auch an dieser Figur des Hamlet.

[ 6 ] Und ich konnte weiter sagen: Wenn man nun eingeht auf die ganze Stimmung, auf die künstlerische Gestaltung in den Shakespeareschen Dramen, in den Shakespeareschen Königsdramen, findet man da, daß in dem künstlerischen Schaffen des Dichters der Shakespeareschen Dramen selber diese Dämmerstimmung des Übergangs liegt. Ich machte dann darauf aufmerksam, wie in einer gewissen Weise gerade in Mitteleuropa Goethe und Schiller mit ihrem ganzen Seelenleben drinnengestanden haben in dem Nachzittern dieses Überganges, wie sie aber in einem gewissen Sinne nicht akzeptieren wollten, was die intellektualistische Weltanschauung seither im Leben der Menschen gestiftet hatte. Dadurch wurden sie zurückgeführt zu Shakespeare, weil sie ja bei Shakespeare die Kunst fanden, im «Hamlet», in «Macbeth» und so weiter, heranzurücken an die geistige Welt; weil sie, von da ausgehend, den Blick auf die nun schon für die intellektualistische Anschauung verborgenen geistigen Mächte werfen konnten.

[ 7 ] Goethe hat das in seinem «Götz von Berlichingen» getan, indem er gewissermaßen Partei nimmt noch für die alte Zeit des vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraumes in ihrem Nachklingen, ablehnend, was durch den Intellektualismus heraufgekommen ist. Und Schiller stellt sich geradezu mit seinen Jugenddramen, namentlich mit dem «Räuber»Drama, so hinein, daß er zwar nicht auf das Übersinnliche da hinweist, daß er ganz realistisch sein will, daß wir aber fast bis auf die Worte hin in der Charakteristik des Karl Moor durchaus das Ahrimanische finden, während wir in der Charakteristik des Franz Moor etwas nachklingen haben von dem luziferischen Element, wie es waltet in Miltons «Verlorenem Paradies». Kurz, wir sehen, trotz dem Realismus, eine Art des Zurückstrebens nach einer solchen Auffassung der Wirklichkeit, daß man in dieser Auffassung durchschimmern sieht die geistigen Mächte und die geistigen Kräfte.

[ 8 ] Ich deutete weiter an, wie im Westen Shakespeare in der Lage war, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, in vollem Einklang mit seiner sozialen Umgebung künstlerisch zu schaffen. Zunächst, wenn wir das für Shakespeare charakteristischste Hamlet-Drama nehmen, sehen wir, wie er die Handlung überall ganz nahe heranrückt an die übersinnliche Welt; und ebenso in «Macbeth». Wir sehen, wie er im «König Lear» zum Beispiel diese übersinnliche Welt mehr in die menschliche Persönlichkeit hereinzieht, aber in die abnorme menschliche Persönlichkeit, in das Element des Wahnsinns. Wir sehen, wie er dann in Königsdramen zwar zur Realistik übergeht, wie aber doch eigentlich in ihnen eine einzigartige lange dramatische Entwickelungsdarstellung waltet, wie er überall das Walten von Schicksalsmächten darinnen hat, aber so, daß das alles zuletzt ausläuft in das Zeitalter der Königin Elisabeth.

[ 9 ] Man möchte sagen: Was in Shakespeares Dramen waltet, das ist ein Rückblick auf die alte Zeit, die seine Gegenwart herbeigeführt hat, aber so, daß diese Gegenwart akzeptiert wird; daß alles, was künstlerisch aus den alten Zeiten dargestellt wird, eine Art von Begreiflichmachen der Gegenwart darstellt..Man kann sagen, Shakespeare schildert die Vergangenheit, aber er schildert sie so, daß er sich in seine soziale Gegenwart des Westens so hineinstellt, daß nunmehr ein gewisser Zeitraum erreicht ist, in dem die Dinge laufen können, wie sie eben ablaufen. Wir sehen, daß eine gewisse Befriedigung eintritt gegenüber dem, was nun gekommen ist in bezug auf die äußere Welt. Der Intellektualismus in der sozialen Ordnung wird akzeptiert vom Menschen der äußeren physischen Erdenwelt, vom sozialen Menschen, während der künstlerische Mensch in Shakespeare zurückgeht und eigentlich das darstellt, was aus dem Übersinnlichen heraus das bloße Intellektualistische geschaffen hat.

[ 10 ] Wir sehen, wie das in Mitteleuropa dann eine Unmöglichkeit wird. Da können sich Goethe und Schiller, und vorher schon Lessing, nicht so in die soziale Ordnung hineinstellen, daß sie sie akzeptieren. Sie gehen alle auf Shakespeare zurück, aber auf den Shakespeare, der selber zurückgegangen ist zum Vergangenen. Sie möchten, daß das Vergangene eine andere Fortsetzung finde als die ihrer Umgebung. Shakespeare ist gewissermaßen zufrieden mit seiner Umgebung; sie sind unzufrieden mit ihrer Umgebung.

[ 11 ] Goethe schafft aus dieser geistigen Revolutionsstimmung heraus das Götz-Drama, Schiller schafft seine Jugenddramen. Wir sehen, wie hier die äußere Erdenwirklichkeit kritisiert wird und wie im Künstlerischen ein Auf- und Abwogen desjenigen wirkt, was nur in der Idee erreicht werden kann, was nur im Geiste erreicht werden kann. So daß man sagen kann: In Goethe und Schiller ist nichts vorhanden von einem Akzeptieren der Gegenwart, sondern nur, daß man sich über das, was in der äußeren sinnlichen Wirklichkeit ist, trösten muß mit dem, was aus der geistigen Welt herunterwirkt. Shakespeare leitet gewissermaßen das Übersinnliche in das Sinnliche herein. Goethe und Schiller können das Sinnliche nur akzeptieren, indem sie immer das Geistige ins Auge fassen. Man hat also in Goethes und Schillers Dramen ein Zusammenwirken des Geistigen mit dem Physischen, im Grunde genommen eine unaufgelöste Disharmonie. Und ich sagte dann: Ginge man weiter nach Osten hinüber, so würde man finden, daß das, was geistig ist, überhaupt gar nicht mehr auf der Erde ist. Der Osten von Europa hat nicht so etwas geschaffen, in das hereinspielt das Geistige, sondern der Osten sieht hinauf zu dem Geistigen; er flieht die äußeren Wirkungen und sieht hinauf zu dem Geistigen als dem Erlösenden.

[ 12 ] So konnte ich Ihnen sagen, indem ich das Ganze dann in ein Bild, in eine Imagination kleidete: Wenn wir uns Faust in Wittenberg vorstellen als Lehrer des Hamlet, dann sehen wir unten auf der Schulbank den Hamlet, zuhörend, dann zurückgehend nach dem Westen und sich in die westliche Zivilisation wieder einlebend. Wenn wir aber diejenige Wesenheit aufsuchen wollten, welche nach dem Osten hätte gehen können, nachdem sie im Auditorium des Faust zugehört hätte, so müßten wir einen Engel suchen, der von der geistigen Welt aus dem Faust zugehört hätte und dann nach dem Osten gegangen wäre. So daß alles das, was er nun vermittelt hätte, sich nicht so abgespielt hätte, wie Hamlets Taten und Handlungen sich auf dem physischen Plane abspielen, sondern das würde sich über den Menschen, in der geistigen Welt, abgespielt haben.

[ 13 ] Und ich führte dann gestern aus, wie aus dieser Stimmung heraus, gerade in der Zeit der Bekanntschaft mit Schiller, Goethe dazu gedrängt worden ist, das Wesen des Menschen wiederum heranzurükken an die geistige Welt; wie er - denn er konnte es nicht so theoretisch ausführen wie Schiller als Philosoph in seinen Ästhetischen Briefen — genötigt war, es ins Imaginative hineinzutreiben in dem «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie». Wie dann weiter Schiller dazu genötigt worden ist, das äußere Wirkliche .des Menschenlebens auch wiederum an das Geistige heranzurücken, und zwar, ich möchte sagen experimentierend, indem er im «Wallenstein» den Gestirnglauben des Wallenstein walten läßt, der wie ein Schicksal über der Persönlichkeit Wallensteins wirkt, indem er in der «Braut von Messina» ein Schicksal geradezu in Verwobenheit mit dem Sternenglauben wirken läßt. So daß also diese Persönlichkeiten genötigt waren, immer wieder und wiederum sich zurückzuwenden zu jener Zeit, in der die Menschen noch einen unmittelbaren Verkehr mit der geistigen Welt hatten.

[ 14 ] Ich habe dann gesagt, daß Goethe und Schiller doch eben in einer Zeit lebten, in der es noch nicht möglich war, aus der modernen Seelenverfassung heraus wiederum den Zugang zur geistigen Welt zu finden. Daher fand sich Goethe gedrängt, während. wahrscheinlich Schiller bei seinem philosophischen Streben, wenn er länger gelebt hätte — man sieht es aus dem «Malteserfragment» -, zweifellos, wenn er dieses Drama zu Ende geführt hätte, sich einen Blick verschafft hätte in die Art und Weise, wie gerade innerhalb eines solchen Ordens wie im Johanniter- oder Malteserorden oder im Templerorden, wie da die geistigen Welten mitgewirkt haben in den Taten der Menschen. Aber es war eben Schiller nicht gegönnt, seine «Malteser» als fertiges Drama vor die Welt hinzustellen; er ist zu früh gestorben. Goethe hingegen konnte nicht bis zu einem wirklichen Ergreifen der geistigen Welt vorrücken, daher wandte er sich zurück. Und wir können sagen: Allerdings in wesentlich metamorphosierter Umgestaltung ist Goethe doch zurückgegangen zu dem katholischen Symbolismus, zu dem katholischen Kultus, zu dem Bildkultus. So daß wir förmlich an die Theophiluslegende der guten Nonne Hrosvitha aus dem 9. Jahrhundert erinnert werden, wenn auch Goethe Faust zuletzt in einem christianisierenden Tableau erlöst sein läßt. Man möchte sagen, man spürt noch - wenn auch allerdings mit Goetheschem grandios-künstlerischem Sinn ausgestaltet - in dem: «Das Ewig-Weibliche zieht uns hinan!» das Hinaufziehen des Theophilus aus dem 9. Jahrhundert durch die Jungfrau Maria.

[ 15 ] Wenn man diese Dinge überblickt, dann sieht man tief hinein, wie unter dem Intellektualismus gerungen wird, unter jenem Intellektualismus, der den Menschen innerlich den Gedankenleichnam erleben läßt dessen, was der Mensch ist, bevor er durch die Geburt beziehungsweise durch die Konzeption heruntersteigt in sein physisches Erdenleben. Was als Gedanke in uns lebt, wenn wir es nicht befruchten durch die Erkenntnisse der Geisteswissenschaft, ist ja bloß ein Geistesleichnam. Was wir geistig eigentlich sind bis zum Erdenleben hin, das stirbt, indem es in den Leib einzieht, und den Leichnam davon tragen wir in uns. Es ist unsere irdische Gedankenkraft, die Gedankenkraft unseres gewöhnlichen Bewußtseins.

[ 16 ] Wie kommt das wieder zum Leben, was eigentlich tot ist in geistiger Beziehung? Das ist die große Seelenfrage, die in Goethe und Schiller lebt. Sie drücken das nicht philosophisch aus, sie haben es aber in der Empfindung. Sie richten ihre Dichtungen danach ein. Aber sie haben diese Empfindung: Da ist etwas Totes, wenn wir bloß bei dem Intellektualistischen bleiben. Wir müssen es zum Leben erwecken. Aus dieser Empfindung streben sie zurück zum Sternenglauben, zu allem Möglichen, um Geist hereinzubekommen in das, was sie darstellen wollen. Es ist schon notwendig, daß man darauf sieht, wie in solchen hervorragenden Persönlichkeiten sich eben der Weltenlauf darstellt, der hereinströmt in ihre Seelen und ihr eigenes Ringen bedeutet. Man begreift die Gegenwart nicht, wenn man nicht sieht, wie das, wonach in der Gegenwart gestrebt werden muß - ein neuerliches Erreichen der geistigen Welt -, wie das gerade das große Problem bei Goethe und bei Schiller bildete.

[ 17 ] Es ist schon so, daß mit diesem großen Umschwung im 15. Jahrhundert, der in den gewöhnlichen landläufigen Geschichtsdarstellungen einfach ganz und gar unberücksichtigt bleibt, der Mensch eine ganz andere Stellung zu sich selbst gewann. Und man muß nicht versuchen, das mit theoretischen Begriffen einzufangen. Man muß versuchen, es in den Empfindungen der Menschen zu verfolgen, wie es sich vorbereitete und wie es später dann auslief, nachdem der Umschwung sich bereits, seiner wesentlichen geistigen Kraft nach, vollzogen hat.

[ 18 ] An den entscheidenden Stellen der Geistesentwickelung wird auch maßgebend auf diese Dinge hingewiesen. Sehen Sie sich einmal an, wie uns dieses entgegentritt bei Wolfram von Eschenbach in seinem «Parzival». Sie kennen ja alle die Vorgänge des Parzival. Sie wissen, daß das Entscheidende bei Parzival in seiner ganzen Entwickelung darinnen liegt, daß er zuerst von einer Art Unterweiser die Anweisung bekommt, durch die Welt zu gehen, ohne viel zu fragen. In Gurnemanz zeigt sich uns eben ein Vertreter jener alten Weltrichtung, die durchaus den Menschen noch im Verkehr mit der geistigen Welt sieht, indem er Parzival sagt: Frage nicht; denn die Fragen kommen ja im Grunde genommen aus dem Intellekt, und vor dem Intellekt fliehen die Geister. Willst du also nahekommen der geistigen Welt, so darfst du nicht fragen.

[ 19 ] Aber die Zeit hat sich geändert, der Umschwung tritt ein. Er wird vorherverkündet: Wenn auch Parzival noch viele Jahrhunderte zurückversetzt werden muß, etwa ins 7. oder 8. Jahrhundert, ist es so, daß alles schon vorgelebt wurde im Gralstempel. Da sind gewissermaßen schon die Einrichtungen der Zukunft; da muß man fragen. Denn das ist das Wesentliche, daß die Stellung des Menschen sich jetzt mit diesem Umschwung vom vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum ändert, und daß man vorher nicht zu fragen brauchte, daß vorher gewissermaßen das galt, was Goethe in paradoxen Worten sagt:

Die hohe Kraft

Der Wissenschaft

Der ganzen Welt verborgen!

Und wer nicht denkt,

Dem wird sie geschenkt,

Er hat sie ohne Sorgen.

[ 20 ] Nicht fragen, denn das Denken vertreibt die Geister! Das war vorher die richtige Ordnung, im intellektualistischen Zeitalter aber muß man durch den Intellekt, nicht durch das Herabdämpfen des Denkens, die geistige Welt wiederfinden. Da muß also gerade das Entgegengesetzte eintreten, damuß man fragen! Dieser ganze Umschwung, daß im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum aus dem Menschen die Sehnsucht nach dem Geiste herausgeboren werden muß in Form der Fragestellung, dieser ganze Umschwung tritt uns schon bei Parzival entgegen. Aber es tritt uns bei Parzival noch etwas anderes, sehr Merkwürdiges entgegen. Das möchte ich in der folgenden Weise charakterisieren:

[ 21 ] Die Sprachen, wie wir sie heute haben, sind ja weit weg von ihrem Ursprunge. Sie haben sich eben weiterentwickelt. Wenn wir heute sprechen, so erinnern ja, ich habe das oftmals ausgeführt, die einzelnen Lautzusammenhänge nicht mehr an das, was mit diesen Lautzusammenhängen bezeichnet wird. Man muß sich erst wiederum ein feineres Sprachgefühl aneignen, um in der Sprache das zu erleben, was die Sprache bedeutet. In den Ursprachen der Menschheit war das nicht so. Da hat man gewußt, wenn man irgendeinen Lautzusammenhang hatte, wie in diesem selber dasjenige darinnen liegt, was man erlebt in dem, was er bedeutet. Heute versucht es der Dichter nachzuahmen, zum Beispiel «Und es wallet und siedet und brauset und zischt». Da haben wir in der Dichtersprache etwas von dem nachgeahmt, was draußen gesehen werden soll. Aber das ist eben alles schon abgeleitet; in jedem einzelnen Laute empfand man einstmals den innigsten Zusammenhang mit dem, was sich draußen abspielte. Heute können höchstens noch die Dialekte einen gewissen Anspruch darauf machen, daß man in den Worten der Dialekte diesen Zusammenhang mit der äußeren Wirklichkeit fühlt. Aber unserer Seele steht die Sprache doch nahe. In unserer Seele bildet die Sprache ein besonderes Element.

[ 22 ] Daß sich das als eine tiefe Empfindung in der Seele des Menschen abgeladen hat, ist wieder eine Folge des Umschwunges vom vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum herein, wiederum etwas, was weder Philologie noch Geschichte berücksichtigen. Daß die Menschen noch mehr in ihrer Sprache im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum gelebt haben, im fünften gar nicht mehr, das bedingt eine andere Stellung des Menschen zur Welt. Denken Sie einmal, wenn der Mensch noch in der Sprache, indem er redet, mitgeht mit dem Rauschen der Wellen, mit dem Donnern und mit dem Blitz und mit alledem, was da draußen ist, wenn der Mensch, indem er seine eigenen Stimmorgane in Bewegung setzt, fühlt, wie in diesen Stimmorganen nachzittert, was draußen geschieht, wie da der Mensch mit seinem Ich ganz anders verknüpft ist mit dem, was draußen in der Welt vorgeht! Und das ist es gerade, was sich immer mehr und mehr losreißt mit dem Umschwung von dem vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum. Das Ich wird innerlich, und die Sprache wird mit dem Ich innerlich, daher aber auch weniger signifikant, weniger das Äußere bezeichnend. Solche Dinge werden von der intellektualistisch gewordenen Erkenntnis erst recht nicht geschaut. Man denkt kaum daran, diese Dinge zu charakterisieren; aber um das, was in der Menschheit vorgeht, wiederum richtig zu verstehen, wird man sie charakterisieren müssen.

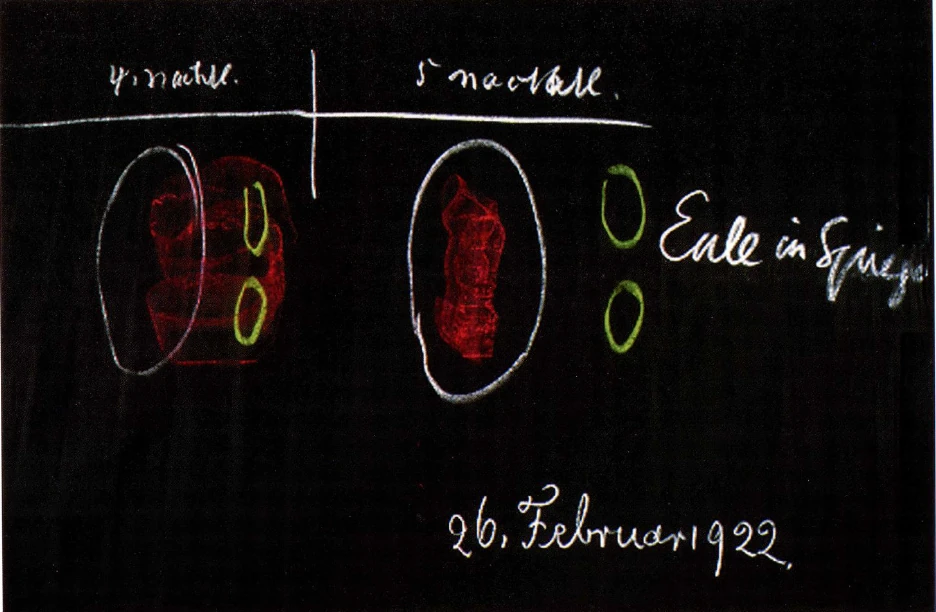

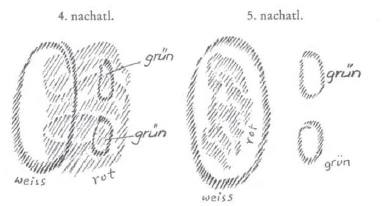

[ 23 ] Nun denken Sie sich einmal, was da entstehen kann. Stellen Sie sich recht lebhaft vor: Vierter nachatlantischer Zeitraum, fünfter nachatlantischer Zeitraum — natürlich werde ich jetzt alles in Extremen zu schildern haben -, der Übergang ist kein schroffer, aber um darzustellen, muß man gewissermaßen schroff sein. Nehmen wir an, das ist der Mensch im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, das im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum (siehe Zeichnung). Im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, wenn da die Dinge der Welt (grün) sind, dann ist der Mensch mit seinen Worten, die ich jetzt als bei ihm seiend mit diesem Rot bezeichnen will, durch die Worte noch mit den Sachen zusammenhängend. Er lebt gewissermaßen sich in die Sache hinüber durch seine Worte. Im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum geschieht es immer mehr und mehr, daß der Mensch die Worte als etwas seelisch gewissermaßen Innerlich-Abgesondertes hat.

[ 24 ] Führen wir uns das, was da vorliegt, einmal etwas deutlich, ich möchte sagen grotesk-deutlich vor die Seele. Wenn wir den Menschen da —- im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum — anschauen, können wir sagen: Der lebt noch mit den Dingen; die Dinge draußen in der Welt, die er selber tut, die werden daher nach seinen Worten vor sich gehen. Wenn man so einen Menschen handeln sieht und zugleich hört, wie er seine Handlungen bezeichnet, dann stimmt das zusammen. So wie seine Worte mit den äußeren Dingen zusammenstimmen, so stimmt auch das, was er tut, mit den Worten zusammen. Wenn der da - im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum — redet, da merkt man nicht mehr, daß seine Worte weiterklingen in dem, was er tut. Was für einen Zusammenhang mit der Tätigkeit empfinden Sie, wenn Sie heute sagen: «Ich habe Holz gehackt»? — Mit dem, was da draußen geschieht, in dem Hacken, empfindet einer ja längst nicht mehr die Bewegung der Hacke. Dadurch entfernen sich aber allmählich die Lautzusammenhänge, sie stimmen dann wirklich nicht mehr mit dem Äußeren überein. Man findet dann keinen Zusammenhang. Und wenn dann einer auf die Worte pedantisch hinhört und doch das tut, was in den Worten liegt, dann wird es ganz was anderes. Da sagt einer: «Ich backe Mäuse.» - Wenn einer nun tatsächlich Mäuse backen würde, so würde das grotesk ausschauen, so würde man das nicht verstehen.

[ 25 ] Das hat man gefühlt und hat gesagt: Der Mensch sollte einmal das, was er eigentlich in der Seele drinnen hat, im Verhältnis zu dem betrachten, was er draußen tut; das verhält sich ja gerade so, wie wenn die Eule in den Spiegel schaut! Wie wenn man der Eule den Spiegel vorhält, so würde sich das verhalten, was einer tut, der sich ganz genau nach den Worten richtet. Und aus dieser Empfindung entstand in der zweiten Hälfte des 14. Jahrhunderts der Till Eulenspiegel. Der Eulenspiegel ist das, was der Menschheit vorgehalten wird. Nicht als ob man das auf den Till Eulenspiegel selber beziehen sollte; sondern indem Till Eulenspiegel wörtlich nimmt, was die Menschen in den trockenen, abstrakten Worten haben, sehen sich die Menschen, während sie sich sonst nicht sehen. Er ist der Eulen-Spiegel, in dem sich die Eulen wirklich sehen können. [An die Tafel wird geschrieben: «Eule in Spiegel».]

[ 26 ] Es ist Nacht geworden. Früher haben die Menschen in die geistige Welt hineingesehen. Ihre Worte haben sie auch so getätigt, daß sie mit der Welt stimmten. Damals waren die Menschen Adler. Jetzt sind sie Eulen geworden. Die Seelenwelt ist ein Nachtvogel geworden. Und in der abenteuerlichen Welt, die der Till Eulenspiegel darstellt, wird eben der Eule der Spiegel vorgehalten.

[ 27 ] So kann man schon das, was in der geistigen Welt auftritt, betrachten. Die Dinge:haben schon ihre Hintergründe. Man lernt einfach Geschichte, und damit auch die Hauptsache in der gegenwärtigen Menschheit, nicht kennen, wenn man nicht auf die geistigen Vorgänge hinblicken kann. Insbesondere ist es wichtig, daß man all das äußerliche Charakterisieren verläßt. Ich bitte Sie, schauen Sie in irgendeinem Wörterbuch nach, was alles an Erklärungen für den Eulenspiegel gegeben wird! Man begreift das nicht, wenn man nicht in den ganzen Vorgang des Geisteslebens hineinsieht. Es kommt schon darauf an bei der Geisteswissenschaft, daß man den Geist in den Dingen wirklich entdeckt; nicht so, daß man einige außerhalb der Sinneswelt befindliche geistige Wesenheiten begrifflich weiß oder nicht, sondern es kommt darauf an, daß man sich hineinfindet in das geistige Betrachten der Wirklichkeit.

[ 28 ] Den Umschwung, der da eingetreten ist, indem die Menschen früher sich der geistigen Welt nahe gefühlt haben und nachher sich wie herausgestoßen fühlten, diesen Umschwung kann man auch sonst durchaus sehen. Ich bitte Sie, fühlen Sie einmal die ganze Tiefe des Impulses, der durch so etwas wie die Parzival-Dichtung hindurchgeht. Nehmen Sie den Parzival, wie ihm von seiner Mutter Herzeleide Narrenkleider angezogen werden, daß er nicht hineinwachsen soll in die Welt, welche die neue Welt darstellt. Er soll bei der alten Welt verbleiben. Er wächst aber doch hinein. Er wächst in die Gralswelt hinein. Er wächst also aus der sinnlichen Wirklichkeit heraus in die geistige Welt hinein. Das 17. Jahrhundert hat auch so eine Art Parzival, aber einen komischen: da ist alles ins Komische getaucht. Im intellektualistischen Zeitalter kann man, wenn man ehrlich ist, zunächst nicht den Seelenduktus aufbringen, der im Parzival waltet. Aber einen solchen Menschen, der ausziehen muß, in die Welt hinaus sich verlieren muß, und der zuletzt doch in der Einsamkeit landet, sein Seelenheil findet, den zeichnet man auch im 17. Jahrhundert, nach dem Umschwung: das ist der «Simplicissimus» des Christoffel von Grimmelshausen. Nehmen Sie nur einmal den ganzen Vorgang des «Simplicissimus». Sie müssen natürlich dabei auf die Stimmung achten - dort die reine, ich möchte sagen heilige Parzival-Stimmung, hier die humoristische, komische Stimmung. Aber nehmen Sie nun den «Simplicissimus»: der Sohn eines Bauern aus dem Spessart. Im Dreißigjährigen Kriege wird das Haus abgebrannt. Der Sohn muß fliehen, kommt zu einem Waldeinsiedler, der ihn in allerlei unterrichtet. Aber der stirbt. Da ist er nun in die Welt hinausgeworfen; er muß wandern. Er wächst hinein in all die Ereignisse, Schicksalsschläge, die eben durch den Dreißigjährigen Krieg geboten werden. Er kommt an den Hof des Gouverneurs von Hanau. Äußerlich hat er nichts gelernt, äußerlich ist er der reine Tor, aber er ist ein innerlicher Mensch bei alledem. Und weil er nun so äußerlich der reine Tor ist, sagt sich der Gouverneur von Hanau: Das ist ein Narr, der weiß nichts, das ist der Simplicissimus, das ist der allereinfältigste Mensch. Wozu soll ich ihn erziehen? Zum Hofnarren. Nun erzieht er ihn zum Hofnarren.

[ 29 ] Aber jetzt ist der äußere Mensch und der innere Mensch auseinandergezogen. Das Ich ist selbständig geworden gegenüber dem äußeren Menschen. Und das wird gerade in dem «Simplicissimus» gezeigt. Jetzt ist der äußere Mensch in der äußeren Welt der zum Hofnarren erzogene Narr, den alle für einen Narren nehmen; und der innere Mensch beim Simplicissimus, der hält alle diese, die ihn zum Narren nehmen, selbst zum Narren, denn er ist, trotzdem er gar nichts gelernt hat, viel gescheiter als die andern, die ihn zum Narren gemacht haben, denn er bringt die andere Intellektualität, die aus dem Geistigen kommt, aus sich heraus, und die Intellektualität, die bloß aus dem Verstande kommt, die tritt ihm in dem Äußerlichen entgegen. Und nun nehmen ihn die Intellektualisten als Narren, und er, der Narr, bringt den Intellektualismus aus der geistigen Welt und hält die andern nun zum Narren, die ihn zum Narren machen wollen. Dann wird er von Kroaten gefangengenommen, abenteuert in der Welt herum, und zuletzt mündet er wiederum in der Einsiedelei ein, um seinem Seelenheile zu leben.

[ 30 ] Ja, schon Wilhelm Scherer hat die Ähnlichkeit des Simplicissimus mit dem Parzival erkannt, aber es kommt auf den Stimmungsunterschied an. Es kommt darauf an, daß das, was noch ganz in die Gemütsseele getaucht war im Parzival, heraufgekommen ist in die Bewußtseinsseele, daß der kaustische Verstand wirkt, daß das Komische, das ja nur im kaustischen Verstand seinen Ursprung haben kann, da wirkt. Wenn man aber ein Gefühl hat für diesen Stimmungsumschwung, dann wird man gerade in solchen Produktionen, die wirklich nicht bloß aus Einzelnen hervorgehen, sehen, was eigentlich in der Menschheitsentwickelung geschehen ist. Und Christoffel von Grimmelshausen hat eben einfach die ganze Stimmung, die Denkweise seiner Zeit hineingeheimnißt in diesen «Simplicissimus» gerade so, wie, man möchte sagen, man das ganze Volk dichtend findet, um alles das zusammenzutragen, was die Seele als Eule im Spiegel sehen kann, und dadurch alle möglichen Geschichten zusammengetragen werden im Till Eulenspiegel.

[ 31 ] Es wäre schon durchaus notwendig, daß man auf alle diese Zusammenhänge einmal genauer einginge, nicht bloß, um im einzelnen diese Zusammenhänge zu charakterisieren. Ich kann Ihnen ja selbst nur einzelne Beispiele geben. Würde man das, was eigentlich gesagt werden kann, sagen, dann müßte man jahrelang über die Dinge reden. Aber darum allein handelt es sich nicht, sondern es handelt sich darum, daß man wirklich einer vergeistigten Auffassung der Dinge näherkommt, wenn man solche Dinge, die nur rein äußerlich hingestellt werden, auch in ihren geistigen Zusammenhängen kennenlernt. Und so darf man sagen: Man sieht überall, wie durch die Geistesentwickelung der Menschheit durchzittert jener gewaltige Umschwung, der da geschehen ist vom vierten in den fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum hinein. Es ist so, daß man, wenn man nur etwas zurückgeht von der Zeitenwende, gleich dasjenige hat, was uns in allen Erscheinungen hinweist darauf, wie stark dieser Umschwung war.

[ 32 ] Man kann ja eigentlich auch nur in einem solchen Zusammenhange ganz verstehen, was in den Gestalten liegt, die das Geistesleben aus der Vergangenheit in die Gegenwart heraufgetragen hat. Nehmen Sie Lohengrin, den Sohn des Parzival. Fragen Sie sich einmal ehrlich: Ist es so ohne weiteres verständlich, daß Elsa nicht nach Namen und Geschlecht des Lohengrin fragen darf? Die Menschen nehmen das so hin; aber warum sie eigentlich nicht fragen soll, das ist etwas, worüber doch nicht intensiv genug nachgedacht wird, weil gewöhnlich die Dinge ihre zwei Seiten haben. Gewiß, man kann die Sache auch anders darstellen, aber ein Wichtiges ist in dem Folgenden enthalten:

[ 33 ] Lohengrin ist der Abgesandte des Grals, der Sohn des Parzival. Womit hat man es denn da innerhalb der Gralsgemeinschaft zu tun? Diejenigen, die um das Geheimnis des Grals wußten, die dachten über dieses Geheimnis des Grals so, daß im Gralstempel nicht bloß die auserlesenen Gralsritter sind, sondern ein jeglicher, der reinen Herzens ist und im richtigen Sinne Christ ist, zieht, so sagte man, während des Schlafens, vom Einschlafen bis zum Aufwachen, nach dem Gral hin. Geradezu als den Versammlungsort der wahrhaft christlichen Seelen während des Nachtschlafens dachte man sich den Gral. Man wollte entrückt sein dem Erdenleben. Daher mußten dem Erdenleben auch diejenigen entrückt sein, die die Gralsherrschaft leiteten. Zu ihnen gehörte Lohengrin, der Sohn des Parzival. Wer daher wirken wollte im Sinne der Gralsimpulse, der mußte sich ganz in der geistigen Welt fühlen, der mußte sich ganz fühlen als ein Angehöriger der geistigen Welt, der durfte vor allen Dingen sich nicht als ein Angehöriger der äußeren Erdenwelt fühlen. Er mußte in einem gewissen Sinne, sagen wir den Vergessenheitstrank haben.

[ 34 ] Lohengrin wird von der Gralsburg abgeschickt. Er verbindet sich mit Elsa von Brabant, also mit dem ganzen Brabantervolk. Er zieht im Gefolge Heinrichs I. gegen die Ungarn. Also er führt im Auftrage des Grals wichtige weltgeschichtliche Impulse aus. Daß er das kann, das rührt von der Kraft her, die er aus dem Gralstempel hat. Ja, wenn wir zurückgehen in den vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum, da werden ja auch diese Dinge anders; da wirkten nicht bloß die äußerlichen, mit dem Verstande zu erfassenden Impulse, da wirkten eben geistige Impulse überall mit. Die geschichtliche Darstellung ist ja so, daß man das kaum merkt.

[ 35 ] Wir reden heute ganz richtig wiederum von Meditationsformeln, einfachen Sätzen, die durch ihre Einfachheit im Bewußtsein wirken. Ich weiß nicht, wieviel Leute heute mit dem richtigen Verständnis darauf hinschauen, wenn ihnen die Geschichte erzählt, daß diejenigen, die aufgefordert wurden, sich den Kreuzfahrern anzuschließen - und das war im vierten nachatlantischen Zeitraum -, daß die versehen wurden mit der Meditationsformel «Gott will es», und daß diese Formel eben mit einer spirituellen Gewalt wirkte. Das war gewissermaßen eine soziale Meditation, die mit dem «Gott will es» gegeben wurde. Achten Sie einmal auf solche Dinge in der Geschichte, Sie werden da schon mehr solche Dinge finden! Sie werden den Ursprung der alten Devisen finden. Sie werden finden, wie gewisse Burgengeschlechter unter solchen Devisen gerade ihre Eroberungszüge begonnen haben, wie sie mit geistigen Mitteln, mit geistigen Waffen gewirkt haben. Mit den bedeutendsten geistigen Waffen wirkten die Gralsritter, wirkte so jemand wie Lohengrin. Er konnte das nur, wenn ihm die Erinnerungen an seine äußere Abstammung, an seinen äußeren Namen, an sein äußeres Geschlecht nicht entgegentraten. Er mußte sich geradezu in eine Sphäre versetzen, wo er dem Geistigen hingegeben sein konnte und sich der Verkehr mit der Außenwelt bloß auf die sinnliche Anschauung beschränkte, nicht auf irgendwelche Erinnerungen. Er mußte unter der Wirkung des Vergessenheitstrankes seine Taten vollführen. Er durfte nichterinnert werden, in seiner Seele durfte nicht aufsteigen: Ich heiße so, ich bin aus diesem Geschlechte. - Daher darf ihn Elsa von Brabant nicht fragen. Für ihn ist das notwendig. In dem Augenblicke, wo er gefragt wird, muß er sich erinnern. Es ist genau dieselbe Wirkung auf seine Taten, wie wenn man ihm sein Schwert bräche.

[ 36 ] Wenn wir eben hinter den Zeitraum gehen, wo alles intellektualistisch geworden ist und wo nun auch die Menschen das, was vorangegangen ist, in iintellektualistische Begriffe kleiden und alles so vorstellen, als ob es gewesen wäre wie nachher, wenn wir hinter das zurückgehen, was dem intellektualistischen Zeitraume angehört, da finden wir auch im sozialen Wirken überall das Spirituelle. Und die Menschen rechneten mit dem Spirituellen, rechneten daher zum Beispiel mit Moralischem als mit Arzneimitteln.

[ 37 ] Ich möchte sehen, wie im intellektualistischen Zeitalter, wenn man nur dem Intellektualismus angehört, die Menschen das auffassen würden, wenn man in seiner Apotheke auch Moral als Arzneimittel hätte! Aber man braucht wiederum nur um ein paar Jahrhunderte hinter den Umschwung zurückzugehen. Lesen Sie den «Armen Heinrich» von Hartmann von Aue, der demselben Zeitalter angehört wie Wolfram von Eschenbach. Da steht vor Ihnen der Ritter, der reiche Ritter, der aber von Gott abgefallen ist, der in seiner Seele den Zusammenhang mit der geistigen Welt verloren hat, der daher dieses atheistische Moment, das über ihn gekommen ist, auch als physische Krankheit erlebt, als die Miselsucht, eine Art Aussatz. Die Leute meiden ihn. Kein Arzt kann ihn heilen. Er kommt zu einem gescheiten Arzt in Salerno. Der sagt ihm, physische Heilmittel gibt es für ihn nicht; das einzige Heilmittel ist, wenn sich eine reine Jungfrau für ihn töten läßt. Das Blut einer reinen Jungfrau kann ihn davon befreien. Er verkauft alle seine Güter, lebt einsam auf seinem Meierhof, wird betreut von einem Meier. Dieser Meier hat eine Tochter. Die gewinnt den aussätzigen Ritter, den Ritter mit der Miselsucht, lieb. Sie hört von dem, was allein sein Heilmittel sein könnte. Sie beschließt, für ihn zu sterben. Er begibt sich mit ihr zum Arzt von Salerno; da wird es ihm leid. Er will lieber weiter den Aussatz haben als dieses Opfer. Aber schon, daß ihr Wille zum Opfer vorhanden war, das wirkt. Er wird nach und nach geheilt. - Wir sehen das Herüberwirken des Spirituellen im geistigen Leben, wir sehen, wie moralische Impulse heilen, als heilende Wirkungen aufgefaßt wurden. Heute sagt man: Nun ja, entweder war es ein Zufall, oder es war überhaupt nicht, man erzählt so etwas nur. - Mag man über den einzelnen Fall denken, wie man will - es muß doch darauf aufmerksam gemacht werden, daß in dem Zeitalter, das dem 15. Jahrhundert vorangegangen ist, im wesentlichen noch viel stärker von Seele auf Seele gewirkt wurde als später, auch von dem, was die Seelen dachten und empfanden und wollten. Denn jene soziale Trennung zwischen Mensch und Mensch, die dann später eingetreten ist, die ist eben durchaus eine Begleiterscheinung des Intellektualismus. Und je weiter der Intellektualismus gedeiht, je weniger man sucht nach dem, was ihm entgegenwirken muß - nach dem Spirituellen — desto mehr wird der Intellektualismus die einzelnen Individualitäten auseinanderspalten.

[ 38 ] Das mußte zwar kommen; Individualismus muß sein. Aber aus dem Individualismus heraus muß das Soziale gefunden werden. Sonst besteht das «soziale Zeitalter» darin, daß die Menschen unsozial sind und deshalb nach Sozialismus schreien. Sie schreien ja am meisten nach Sozialismus, weil sie im Inneren der Seele unsozial sind. Aber dieses soziale Element, das einem in solch einer Dichtung wie «Der arme Heinrich» des Hartmann von Aue entgegentritt, das müssen wir beachten. Das tritt dann auch in geistigen Schöpfungen zutage, und in den geistigen Schöpfungen findet man es sehr deutlich in der Stimmung. Es ist in diesem «Armen Heinrich» eben eine ganz andere Stimmung vorhanden. Wir können natürlich nicht sagen, sentimental; denn sentimental ist man erst später in dem unnatürlichen Herausgehen aus dem Intellektualismus geworden. Aber es ist eine Art frommer Stimmung, eben eine Art spiritueller Stimmung darinnen. Will man später ehrlich sein in denselben Sachen, dann muß man komisch werden, dann muß man so darstellen, wie Christoffel von Grimmelshausen im «Simplicissimus» dargestellt hat, oder wie das Volk selber im «Till Eulenspiegel» dargestellt hart.

[ 39 ] Dieses Sich-herausgeworfen-Fühlen aus der Welt, das tritt uns nicht bloß in den Dichtungen eines Volkes, das tritt uns im Grunde genommen überall entgegen. Und nun sehen Sie, wie in alldem eine andere Stellung des Menschen zu sich selber liegt. Der Mensch muß wieder von einem ganz neuen Standpunkte aus die Frage aufwerfen: Ja, was bin ich denn eigentlich als Mensch? — Das zittert immer nach. Daher wird vom neuen intellektualistischen Standpunkte aus diese Frage immer wieder neu gestellt: Was ist denn das eigentlich, der Mensch? — Früher hat man sich an die geistige Welt gewendet. Da haben die Leute das ja wirklich gesucht, was der Faust vergeblich wiederum sucht. Man wendete sich an die geistige Welt, wenn man wissen wollte: Was ist eigentlich der Mensch? Weil man wußte: Außerhalb dieses physischen Erdenlebens ist ja der Mensch ein Geist. Will er also sein wahres Wesen, das er auch im physischen Erdenleben lebt, kennenlernen, dann muß er sich an die geistige Welt wenden. Aber immer mehr kommt er davon ab, sich an die geistige Welt zu wenden.