Old and New Methods of Initiation

GA 210

19 March 1922, Dornach

Lecture XIV

Many reasons have led us to consider how the age of intellectualism—which we have often also called the age of the fifth post-Atlantean culture—begins in the transition from the thirteenth to the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. In this age, human beings come to regard the intellect as the dominant factor in all their endeavours. We have often spoken of the way in which this intellectualism has come to develop in the various realms of inner life. Everything that is characteristic for human evolution has its more inward aspect through which it live:, more expressly in people's feelings, in their views, in their dominant will impulses, and so on. At the same time it also has an outward aspect which manifests in the conditions and circumstances which arise historically in human evolution. In this connection it has to be said that the most significant expression of the intellectualistic age so far has been the French Revolution, that great world-wide movement of the end of the eighteenth century.

For long ages before it took place, much in the life of mankind pointed to ways of striving for the very kind of social community which then came to be expressed so tumultuously in this French Revolution. And since then much has remained of the French Revolution, flickering into life here or there in one form or another in the external social conditions of mankind. Only consider that the French Revolution, in the way it manifested at the end of the eighteenth century, could not have been possible previously. For prior to those days human beings did not seek full satisfaction on this earth with regard to everything they were striving for.

You must understand that before the time of the French Revolution there was never a period in the history of mankind when people expected everything human beings can strive for, in thought, feeling and will, to find an external expression in earthly life. In the times which preceded the French Revolution, people knew that the earth can never provide for every single requirement of man's spirit, soul and body. Human beings always felt that they had links with the spiritual world and they expected this spiritual world to satisfy whatever requirements cannot be satisfied by the earthly world.

However, long before the French Revolution expressed itself in such a tumultuous fashion there were endeavours in many realms of the civilized world to introduce a social order which would allow as many human needs as possible to be satisfied here on earth. The fundamental character of the French Revolution itself was the endeavour to found a social environment which would be an expression here on earth of human thinking, feeling and willing. This is essentially what intellectualism seeks, too.

The realm of intellectualism is earthly existence. Intellectualism wants to satisfy everything that is present in the sense-perceptible physical world. So it wants to organize the social situation here on earth to be an expression of the intellectual element. The endeavour to create in social conditions something which man can strive for here on earth, even goes to the extent of the worship of the goddess of reason—which means, of course, the goddess of the intellect. So we can say: In very ancient times human beings ordered their lives according to the impulses which came to them from initiates and mystery pupils; through them they took into their social order the divine spiritual world itself. Then social conditions moved on to those of, let us say, Egypt, when the social order took in what the kings learnt from the priests about the will of human evolution as it was expressed, for instance, in the stars. Later still, in older Roman times, the times of the Roman kings, the endeavour was made to bring about social conditions based on research into the spiritual world. The meeting of Numa Pompilius with the nymph Egeria is an expression of this.1 Numa Pompilius, 715-672 BC. Roman King. By tradition, the nymph Egeria was his wife and adviser. More and more out of this interweaving of the spiritual with the earthly, social realm came the requirement: Everything on earth is to be arranged in such a way as to be a direct expression of the intellect.

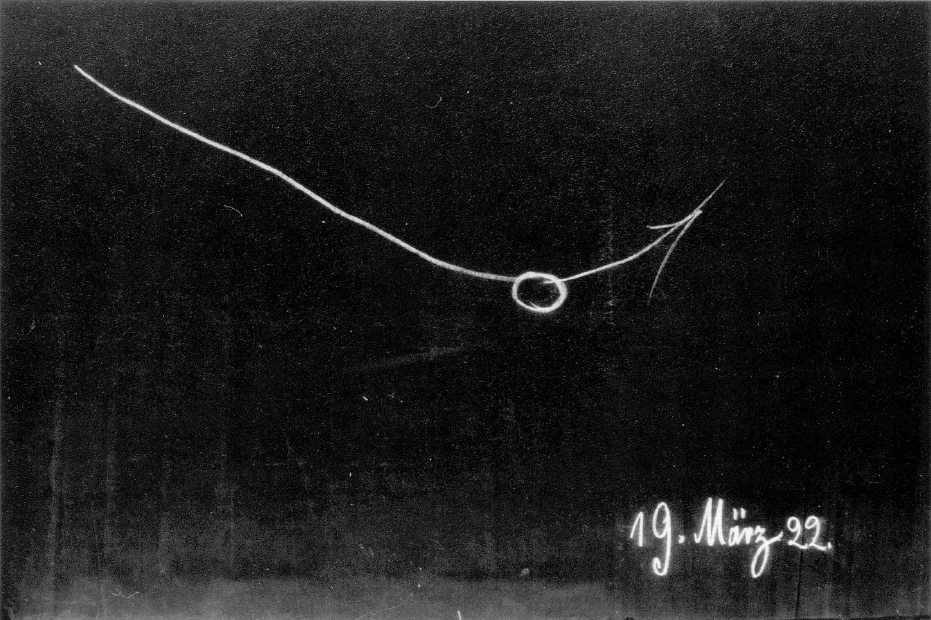

To express this in a diagram you would have to draw a downward curve. The French Revolution comes at the lowest point (see sketch), and from here onwards things had to start moving upwards once more. This upward movement was indeed immediately attempted as a reaction to the French Revolution. Read Schiller's Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (Aesthetical Essays). There we can see quite clearly, for instance, how he was stimulated by what was expressed in the French Revolution in an external way to seek a new connection to the spiritual world within man's inner being. For Schiller the question arose: If it is impossible to create a perfect social order here on earth, how can human beings achieve satisfaction with regard to their thinking, feeling and will? How can they achieve freedom here on this earth?

And Schiller answered this question by saying: If human beings live logically, in accordance with the dictates of reason, they are servants of the dictates of reason and not free beings. If they follow their physical urges and instincts alone, then in turn they are following the dictates of nature and are unfree. He then came to say: The human being is actually only free when he is working artistically or when he is enjoying something artistic. The achievement of freedom in the world can only come about when the human being works artistically or enjoys art. Artistic activity balances what is otherwise either a dictate of reason or a dictate of nature, as Schiller puts it. Living in the artistic realm, the human being feels the compulsion of thoughts less with regard to an artistic object than he does in the case of logical research. Similarly, what comes to him from the object of art through his senses is not a sensual urge. The sensual urge is ennobled by the spiritual seeing of something artistic. So inasmuch as a human being is capable of working artistically he is also capable of unfolding freedom within earthly existence.

Schiller seeks to answer the question: How can man as a social being achieve freedom? And the conclusion he reaches is that the human being can only achieve freedom if he is a being who is receptive to art. He cannot achieve freedom by being devoted to the dictates of reason or the dictates of nature.

At the time when Schiller was writing his Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (Aesthetical Essays) this came to expression in a wonderful way in the interaction between Goethe and Schiller. This is shown in the way Schiller perceived how Goethe was rewriting his Wilhelm Meister at that time. Schiller was full of enthusiasm for this way of writing and for this depiction of inner freedom, because Goethe as an artist was a creative spirit—not in his intellect but in the freedom of his thoughts—yet one who, on the other hand, still remained within a sensual experience of art. Schiller sensed this. He felt that Goethe in his artistic activity was as free as is a child at play. We see how Schiller is enthused by a free human artistic activity which is reminiscent of a child at play. His enthusiasm led him to say in one of his letters to Goethe: The artist is the true human being; in comparison even the best philosopher is a mere caricature.2 Letter to Goethe of 7 January 1795. But his enthusiasm also led him to say: The human being is only truly human when he is at play, and he only plays when he is truly human.3 Schiller, On the Aesthetic Education of Man, Letter 15. Frivolous or merely entertaining play is not meant, but artistic activity and artistic enjoyment. The human being dwells within artistic experience, which means that the human being becomes truly free: This is what Schiller is saying.

At the point where the line starts to curve upwards from what had been—with regard to a social order—the goal of the French Revolution, towards something for which human beings have to wrestle inwardly and which cannot be given to them by institutions of the state; at this point, what price was the human being willing to pay for this social freedom? He was prepared to pay the price that it could not be given to him through logical thinking and that it could not be given to him through ordinary physical life, but that he could receive it only in the exclusive activity of artistic experience.

These feelings were indeed engraved within the best spirits of that age, in Schiller in a theoretical form, and in Goethe too, who actually practised this life in freedom. Let us look at the characters Goethe created out of life itself in order to reveal genuine humanity, the true human being. Look at Wilhelm Meister. Wilhelm Meister is a personality through whom Goethe wanted to depict the true human being. Yet seen from an overall view of life he is actually a layabout. He is not a person who is seriously searching for a world view which includes the human soul. Neither is he someone who can manage to hold down a job in external life. He loiters his way through life. This is because the ideal of freedom striven for in the work of Goethe and Schiller could only be achieved by people who had removed themselves from a thoughtful and hard-working way of life. It is almost as if Schiller and Goethe had wanted to point to the illusion of the French Revolution, to the illusory belief that something external, like the state, might make human beings free. They wanted to point out that human beings can only wrestle for this freedom within themselves.

Herein lies the great contrast between Central Europe and Latin western Europe. Latin western Europe believed in an absolute sense in the power of the state, and it still believes in it today. In Central Europe, on the other hand, came the reaction that the human ideal can only be found within. But the price for this would have to be the inability to stand squarely in life. Someone like Wilhelm Meister had to disentangle himself from life.

So we see that at the first attempt it proved impossible to find full humanity within a true human being. Naturally, if everybody is to become an artist so that, as Schiller put it, society can become entirely aesthetic, this may be all very well, but such an aesthetic society would not be very good at coping with life. I cannot imagine, for instance—let me be really down to earth for a moment—how in such an aesthetic society the sewers will be kept clear. Neither can I imagine how in this aesthetic society certain things will be achieved which ought to be achieved in accordance with strictly logical concepts. The ideal of freedom shone before mankind, but human beings were unable to strive for this ideal of freedom when they stood fully within life. It became necessary to search once more for an impetus upwards to the super-sensible world, but now this had to be done consciously, just as in former times there had been an atavistic downward impetus. A new upward impetus into the spiritual world had to be sought. It was necessary to hold on to the ideal of freedom but, at the same time, the upward impetus had to be sought. First it had to be made possible to secure freedom for human activity, for active involvement in life. It seemed to me that the only possible way was that described in my Philosophy of Freedom.4 Rudolf Steiner, Philosophy of Freedom, Rudolf Steiner Press, London 1988.

If human beings can achieve the impetus to rise up to an inner constitution of soul which enables them to find moral impulses in pure thoughts, in the way I have just described, then they will be free beings even though they remain squarely within full, everyday life. This is why I had to introduce into my Philosophy of Freedom the concept of moral tact, which is otherwise not found in moralizing sermons, the concept of acting as a matter of course out of moral tact, by means of which moral impulses can flow over into habitual deeds.

Consider the role played by tact, by moral good taste, in my Philosophy of Freedom. There you see that in an aesthetic society true human freedom is only applied to the feelings, whereas it actually ought to be brought also into the will, that is, into every aspect of the human being. A human being who has achieved a soul constitution in which pure thoughts can live in his will as moral impulses, can enter fully into life, however burdensome it may be, and he will be able to stand in this life as a free being in so far as this life calls for actions, deeds.

Furthermore, with regard to the dictates of reasoning, that is, the grasping of the world in thoughts, a way also had to be sought of finding what it is that guarantees freedom for the human being, independence from external compulsions. This could only come about through anthroposophical spiritual science. Learning to find their way into what can be experienced in spirit with regard to cosmic mysteries and cosmic secrets, human beings live in thoughts with their humanness into a closeness with the inner spirit of the world. Through freedom they achieve knowledge of the spirit.

What is going on here is best demonstrated by the way in which people, with regard to this, are still strenuously resisting becoming free. This is a point of view from which opposition to Anthroposophy can very well be understood. Human beings do not want freedom in the spiritual realm. They want to be compelled, led, guided by something. And since every individual is free either to recognize or deny the spirit, most deny it and choose instead something which they are not free either to recognize or deny.

No free decision is required to recognize or deny thunder and lightning, or the combination of oxygen or hydrogen in some laboratory process. But human beings are free to recognize that angeloi and archangeloi exist. Or they can deny their existence. But those who truly possess an impulse for freedom come through this very impulse for freedom to the recognition of the spiritual in thinking. In Schiller's Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man (Aesthetical Essays), in the whole of Goethe's creative work, the achievement of human freedom through inner effort and struggle was first attempted. But this can only be achieved if we recognize that to our freedom in the realm of artistic experience must be added a free experience in the realm of thinking and a free experience in the realm of the will. These are things which must be properly developed.

Schiller simply took what the age of the intellect had to offer. In Schiller's time art still arose out of this intellectualism. Within this, Schiller still discovered human freedom. But what intellectualism has to offer in the realm of thinking is something unfree, something which is subject to the dictates of logic. And Schiller failed to recognize the possibility that freedom might also hold sway here, just as little as it might hold sway in deeds, in ordinary, hard life. What we have had to achieve through the introduction of anthroposophical spiritual science is the recognition that freedom can also be recognized in the realm of thinking and in the realm of the will. Schiller and Goethe recognized freedom solely in the realm of feeling.

But the path to a full recognition of human freedom can only be trodden if human beings are able to achieve an inner vision of the connection between the spiritual realm they can experience in their soul, and the realm of nature. So long as two abstract concepts, nature and spirit, are seen by human beings as being mutually exclusive, it will not be possible for them to progress to a proper conception of the freedom I have been describing. But even those who do not work their way towards life in the spiritual world, by means of meditation, concentration exercises and so on, can certainly experience something, if they are willing to recognize, simply with their healthy commonsense, what has been found through Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition. Simply by reading in books or hearing in lectures what is brought to the fore in the world through Imagination—and provided they remain alert—people will soon need to approach these revelations from the spiritual world in a way that differs from their approach, say, to a book on physics or chemistry, or on botany or zoology, even though this different approach can just as much take a course which follows ordinary healthy common sense.

Without developing any great inner activity it is possible to absorb everything written today in a book about botany or zoology. But it is not possible to absorb what I have described, for instance, in my book Occult Science, without inner energy and activity such as that needed also for ordinary healthy common sense. Everything in this book can be understood, and those who maintain that it is incomprehensible are simply unwilling to think actively; they want to absorb it as passively as they absorb a film in the cinema. In the cinema there is certainly no need to think very much, and it is in this manner that people today want to absorb everything. What they find in the laboratory can also be absorbed in this way. But what is said in my book Occult Science cannot by absorbed in this way. Occasionally some professorial souls do attempt to absorb it in this way. In consequence, they then make the suggestion that those who perceive such things ought to be examined in psychological laboratories, as they are called today. This suggestion is just as clever as requiring someone who solves mathematical problems to be examined in order to ascertain whether he is capable of solving mathematical problems. To such a person it is said: If you want to find out whether these mathematical problems have been solved correctly, you will have to learn how to solve them, and then you will be able to check. Only if he were stupid would he retort: No, I don't want to learn how to check on the solutions; I shall go to a psychological laboratory in order to find out whether they are correct! These are the kinds of demands made today by some professorial souls, and their words are taken up by all sorts of ‘generals’5 This is a reference to speeches given by General von Gleich. and repeated parrot-fashion with evil intent. Such demands are foolish and stupid, but this does not prevent them from being made with the greatest aplomb.

But those who enter with inner activity into what comes from Imagination will certainly find that something bears fruit in their soul. It is not insignificant for the soul when an effort is made to understand something that has been discovered through Imagination. For instance, it is extremely difficult today to make medicines effective for the treatment of illnesses. But someone who has made the effort to understand something given through Imagination will have reactivated his vital forces to such an extent that medicines will once more be effective for him—provided they are the right ones—because his organism will no longer reject them.

It is stupidly suggested nowadays that anthroposophical medicines are supposed to heal people spiritually through hypnosis and the power of suggestion. You can read this in all manner of magazines which refer to remarks I have made on my lecture tours in recent months. But this is, in the first instance, not the point. The point is that today's medical knowledge needs to be advanced positively through spiritual knowledge. Of course it is not possible to heal somebody by inoculating him with an idea. Yet spiritual life, taken quite concretely, does have significance for the effectiveness of medicines. If a person endeavours to understand something given through Imagination, he makes his organism more receptive to medicines—provided they are the ones needed for his illness—than is the organism of a person who remains in the thought structure of today's external intellectualism, that is, of today's materialism.

Mankind needs to take in what can be given by Imagination, if only for the reason that the human physical body will otherwise succumb more and more to a condition in which it cannot be healed if it falls ill. Healing always requires assistance from the element of spirit and soul. All the processes of nature find expression not only in what takes place on the sense-perceptible plane. These processes on the physical plane are everywhere steeped in the element of spirit and soul. To make a sense-perceptible substance effective in the human organism you need the element of soul and spirit. The whole process of human evolution requires that the soul make-up of human beings should once more be filled with what can be grasped by soul and spirit.

It is true to say that amongst human beings there is certainly much longing for soul and spirit. But for the most part this longing remains within the unconscious or the subconscious realm. Meanwhile, what remains within human consciousness is no more than a mere remnant of intellectualism, and this rejects—indeed resists—anything spiritual. The manner in which spiritual things are resisted is sometimes quite grotesque. Before a performance of eurythmy I usually explain that eurythmy is based on an actual, visible language. Just as the language of sounds develops out of the way the physical organism is arranged, so it is with the visible language that is eurythmy. Just as—sound for sound—all vowels, all consonants struggle to be born out of the experience of the human organism, so in eurythmy is sound for sound gathered together, resulting in genuine language. You would think that on being introduced to eurythmy people might endeavour to find their way into the fundamental impulse which tells us that eurythmy is a language, is speech.

Of course it is perhaps not immediately obvious as to what is meant. But with serious intent it is not too difficult to find one's way quite quickly into what is meant. The other day someone read something really funny in a review of a eurythmy performance. The critic pointed out that the impossible nature of this eurythmy performance was revealed in the fact that the performers first gave a rendering of some earnest, serious items, and that they followed these with some humorous pieces. The extraordinary thing, said this witty critic, was that the humorous items were depicted with the same gestures as the serious ones. That is the extent to which he understood the matter. He thought that humorous things ought to be shown with sound gestures that are different from those used to depict serious matters. Now if you take seriously the fact that eurythmy is a visible language, then what this critic says would amount to saying that any language ought to have one set of sounds for serious things and another for humorous things! In other words, somebody reciting something in German or French would use sounds such as I or U, or whatever, but that on coming to a humorous item they would use other sounds. I don't know how many people noticed what utter nonsense this critic was writing in one of Germany's foremost newspapers; but this is what he was saying in reality. This shows that in such heads every capacity for thinking clearly has ceased; they are entirely unable to think any more.

This is the final consequence of intellectualism, which is gaining ground today in all realms of life. People begin by allowing their thoughts to become the dead inner content of their soul. How rigid, how dead are most thoughts which are produced these days; how little inner mobility they have, how much are they parroted from models created earlier on! There are extraordinarily few original thoughts in our present age. But something that has died—and thoughts today are mostly thoughts that have died—does not remain constantly in the same state. Look at a corpse after three days, after five years or after forty years. It goes on dying, it goes on decomposing. If somebody states that a eurythmy performance is impossible because it uses the same gestures for humorous and for serious items, this is a thought that is decomposing. And if this is not noticed it is simply because people are incapable of schooling their common sense by means of inspired truths such as those arising out of Anthroposophy. If people school their common sense by means of inspired truths, even if they do not undertake any spiritual development, then they acquire a delicate sense for the living truth, and for what is healthy and unhealthy in human thinking and in human endeavour. And then—if you will pardon my saying so—statements such as the one I have just quoted begin to stink. People acquire the capacity to smell the stench of such decomposing thoughts. This capacity, this sense of smell, is for the most part lacking amongst our contemporaries. Most of them do not notice these things, they read them without taking them in.

It is certainly necessary to look very thoroughly into what mankind needs. For human beings definitely need that freedom of thinking in their soul constitution which can only become possible if they raise themselves to a position in which they can take in spiritual truths. Without this we come to that decline of culture which is clearly to be seen all around us today. Healthy judgment, the right immediate impression—these are things which mankind has for the most part already lost. They must not be allowed to get lost, but only if human beings can press through to an acceptance of spiritual things will they not be lost.

We must pay attention to the fact that human beings can find in Anthroposophy a meaningful content for their lives if they turn with their healthy common sense to what can be won through Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition. By opening themselves to what can be discovered, for example, through Imagination, they can recapture that inner vitality which will make them receptive to medicines. Or, it may be that they will also become free personalities who are not prone to succumb to all sorts of public suggestions.

By entering in a living way into the truths revealed by Inspiration, they can gain a sure sense for what is true or false. And they can become skilful in putting this sure sense into practice in the social sphere. For instance, how few people today are able to listen properly! They are incapable of listening, for they react immediately with their own opinion. This capacity to listen to other human beings can be developed most beautifully by entering in a living way into the truths given by Inspiration.

And by entering in a living way into the truths given by Intuition, human beings can develop to a high degree something else which they need in their lives: a certain capacity to let go of their own selves, a kind of selflessness. Entering in a living way into the truths given by Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition, this gives human beings a meaningful content for their lives.

Of course, it is easier to say that people can gain a content for their lives out of what Ralph Waldo Trine6 Ralph Waldo Trine, 1866-1958. In Tune with the Infinite, London 1915. promises. It is easier to say they need only read the content of something in order to gain a content for their lives, whereas it is more difficult to obtain a content for life in an anthroposophical way. For along this path you have to work; you have to work in order to enter in a living way into what research reveals through Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition. But then it becomes a content for life which unites intensely with the personality and with the whole human being. This secure life content is what is given by what wishes to enter the world as Anthroposophy.

Das Freiheitsideal bei Schiller und Goethe

[ 1 ] Verschiedene Anlässe haben uns dazu geführt, zu betrachten, wie im Übergange vom 13. ins 14. und 15. Jahrhundert das Zeitalter des Intellektualismus beginnt, das Zeitalter, das wir auch oft bezeichnet haben als das der fünften nachatlantischen Kultur. Es ist gerade dadurch charakterisiert, daß in diesem Zeitalter der Mensch dazu kommt, als das Tonangebende in allem seinem Streben das Intellektuelle zu betrachten. Wie sich dieser Intellektualismus auf den verschiedenen Gebieten des inneren Lebens ausgebildet hat, davon haben wir ja oft gesprochen. Alles, was charakteristisch ist für die Menschheitsentwickelung, hat eine innere Seite, durch die es sich mehr auslebt in den Empfindungen, in den Anschauungen der Menschen, in den herrschenden Willensimpulsen und dergleichen. Zugleich hat es aber auch eine äußere Seite, durch die es sich darlebt in den Zuständen, die sich geschichtlich in der Menschheitsentwickelung ergeben, und da muß man sagen, daß vorläufig der am meisten bezeichnende Ausdruck für das intellektualistische Zeitalter geschichtlich die Französische Revolution ist, diese große Weltbewegung vom Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts.

[ 2 ] Allerdings, vieles hat im Menschheitsleben durch lange Zeiten hindurch darauf hingewiesen, wie eine solche Art des sozialen Zusammenseins angestrebt werden soll, wie sie dann in der Französischen Revolution tumultuarisch zum Ausdrucke gekommen ist. Und vieles ist wiederum von der Französischen Revolution geblieben, das in der einen oder in der andern Form da oder dort auflebt, und zwar auflebt in den äußeren sozialen Zuständen der Menschheit. Man braucht sich ja nur zu überlegen, wie die Französische Revolution etwas darstellt, was in der Art, wie sie sich am Ende des 18. Jahrhunderts dargelebt hat, vorher nicht möglich gewesen wäre, und zwar aus dem Grunde, weil für alles, was der Mensch hier auf der Erde anstrebte, er eigentlich nicht die volle Befriedigung auch auf dieser Erde gesucht hat.

[ 3 ] Seien Sie sich doch klar darüber, es hat vor dem Zeitalter der Französischen Revolution in der geschichtlichen Entwickelung der Menschheit niemals eine Epoche gegeben, in der sich die Menschen gesagt hätten: Alles, was der Mensch durch sein Denken, Fühlen, Wollen anstreben kann, das muß auch einen äußeren entsprechenden Ausdruck im irdischen Dasein selber finden. - In jenem Zeitalter, das der Französischen Revolution vorangegangen ist, war man sich klar darüber, daß die Erde nicht alles hergeben kann, was der Mensch an Bedürfnissen seines Geistes, seiner Seele und seines Leibes haben kann. Der Mensch hat sich immer mit einer übersinnlichen Welt verbunden gefühlt und hat es dieser übersinnlichen Welt zugeschrieben, daß sie befriedigen müsse, was auf der Erde nicht befriedigt werden kann.

[ 4 ] Allerdings, lange bevor die Französische Revolution ihren tumultuarischen Ausdruck fand, strebte man auf den verschiedensten Gebieten der zivilisierten Welt dahin, eine soziale Ordnung herbeizuführen, durch die auf der Erde möglichst viel von den menschlichen Bedürfnissen befriedigt werden kann. Die Französische Revolution aber hat ihren Grundcharakter darin, daß einfach ein sozialer Zustand hervorgerufen werden sollte, der ein entsprechender Ausdruck für menschliches Denken, Fühlen und Wollen schon hier auf der Erde ist. Das ist im wesentlichen das Streben des Intellektualismus.

[ 5 ] Der Intellektualismus hat als sein Gebiet das irdische Dasein. Alles, was in der sinnlich-physischen Welt vorliegt, das will der Intellektualismus befriedigen. Er will also auch innerhalb der physischen Erdenordnung solche soziale Zustände herbeiführen, welche ein Ausdruck für das Intellektuelle sind. Bis zur Anbetung der Göttin der Vernunft, womit aber eigentlich gemeint war die Göttin des Intellekts, geht ja dieses Streben, in den sozialen Zuständen das hervorzurufen, was der Mensch anstreben kann. Man kann also sagen: Von sehr alten Zuständen, in denen die Menschen sich richteten nach den Impulsen, die ihnen von den Eingeweihten und Mysterienschülern kamen, durch welche sie das Göttlich-Geistige selbst in ihre soziale Ordnung aufnahmen, von jenen alten Zuständen her bewegte sich das soziale Streben der Menschheit etwa zu den ägyptischen Zuständen, wo in die soziale Ordnung aufgenommen wurde dasjenige, was die Könige von den Priestern erfuhren über den Willen der Menschheitsentwickelung, wie er sich etwa in den Sternen ausspricht. Später dann, im älteren Rom, noch im königlichen Rom, versuchte man - es wird das angedeutet durch die Unterredung des Numa Pompilius mit der Nymphe Egeria -, durch die Erforschung der geistigen Welt das hervorzurufen, was soziale Zustände sein sollten. Immer mehr und mehr entwickelte sich dann aus diesem Ineinanderweben des Geistigen mit dem Sinnlich-Sozialen die Forderung: Alles soll auf der Erde so gestalter werden, daß es ein unmittelbarer Ausdruck des Intellekts sei.

[ 6 ] Will man schematisch solch einen Gang darstellen, so muß man ihn in der Form einer absteigenden Kurve darstellen. Im Tiefpunkt steht dann die Französische Revolution (siehe Zeichnung), von hier aus mußte es dann wieder aufwärtsgehen. Dieses Aufwärtsgehen wurde auch sogleich wiederum als eine Reaktion auf die Französische Revolution versucht, und wir sehen ja genau, wie zum Beispiel Schiller wir können es in den Briefen «Über die ästhetische Erziehung» selber lesen — angeregt worden ist, durch das, was durchaus in der Französischen Revolution auf äußerliche Weise zum Ausdruck kam, nun im Inneren des Menschen wiederum einen Anschluß an die geistige Welt zu suchen. Für Schiller entstand die Frage: Wenn es unmöglich ist, hier auf der Erde eine vollkommene soziale Ordnung hervorzurufen, wie kann der Mensch zu dem kommen, was ihn in bezug auf sein Denken, Fühlen und Wollen befriedigen kann; wie kann der Mensch auf dieser Erde zur Freiheit kommen?

[ 7 ] Und Schiller beantwortete diese Frage dahin, daß er sagte: Wenn der Mensch logisch, der Vernunftnotwendigkeit nachlebt, so ist er eben ein Diener der Vernunftnotwendigkeit, er ist kein freies Wesen. Wenn der Mensch seinen sinnlichen Trieben folgt, seinen bloßen Instinkten, dann gehorcht er wiederum der Naturnotwendigkeit, er ist kein freies Wesen. - Und Schiller kam dazu, sich zu sagen: Eigentlich ist der Mensch ein freies Wesen nur dann, wenn er entweder künstlerisch schafft oder genießt. Eine Verwirklichung der Freiheit in der Welt kann es einzig und allein nur dadurch geben, daß der Mensch künstlerisch arbeitend oder künstlerisch genießend ist. Da wird im künstlerischen Anschauen ausgeglichen, was sonst Zwang der Vernunftnotwendigkeit ist oder Zwang der Naturnotdurft, wie Schiller sich ausdrückt. Indem der Mensch im Künstlerischen lebt, ist es Ja so, daß er in dem Kunstobjekte nicht einen solchen Zwang des Gedankens empfindet wie beim logischen Forschen. Auch in dem, was ihm entgegentritt durch die Sinne, empfindet er nicht den sinnlichen Reiz, sondern dersinnlicheReiz wird geadelt durch das geistige Anschauen im Künstlerischen. Der Mensch ist also, insofern er ein der Kunst fähiges Wesen ist, auch fähig, die Freiheit innerhalb des irdischen Daseins zu entfalten.

[ 8 ] Schiller sucht also die Frage zu beantworten: Wie kann der Mensch als soziales Wesen zur Freiheit kommen? - Und er kommt zu der Antwort, daß der Mensch nur als ein für Kunst empfängliches Wesen zur Freiheit kommen kann, daß er nicht frei sein könne in der Hingabe an die Vernunftnotwendigkeit, und ebensowenig i in der Hingabe an die Naturnotwendigkeit.

[ 9 ] Es kam in der Zeit, in der Schiller seine Briefe «Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen» schrieb, dies gerade im wechselseitigen Verkehr Goethes und Schillers in einer großartigen Weise zum Ausdrucke. Dies zeigt sich darin, wie Schiller aufgenommen hat dasjenige, was Goethe dazumal umarbeitete an seinem «Wilhelm Meister», wie er hingerissen war von dieser Art der Darstellung, von dieser innerlichen Freiheitsdarstellung, weil Goethe als Künstler gar nicht ein intellektualistischer, sondern ein im freien Gedanken schaffender Geist war, der aber auf der andern Seite durchaus innerhalb des sinnlichen Erlebens in der Kunst stehenblieb. Das empfand Schiller. Er empfand Goethes künstlerische Betätigung so frei, wie das Spiel des Kindes frei ist. Und wir sehen, wie Schiller enthusiasmiert ist von dieser an das Spiel des Kindes erinnernden freien künstlerischen Betätigung des Menschen. Das begeisterte ihn ja zu dem Ausspruche: Der Künstler ist der einzige wahre Mensch, und der beste Philosoph ist gegen ihn nur eine Karikatur — wie es in einem Brief an Goethe heißt. Das begeisterte ihn aber auch zu dem Ausspruch: Der Mensch ist nur dann ganz Mensch, wenn er spielt, und er spielt eigentlich nur, wenn er ganz Mensch ist. —- Damit ist nicht ein frivoles oder ein unterhaltsames Spiel gemeint, sondern es ist das künstlerische Tun und das künstlerische Genießen gemeint. Es ist das Verweilen des Menschen im künstlerischen Erleben gemeint, und es ist damit gemeint das wirkliche Freiwerden des Menschen.

[ 10 ] Nun, um welchen Preis wollte man sich denn da, wo man von dem, was in der Französischen Revolution als soziale Ordnung angestrebt worden war, wieder hinaufstrebte zu etwas, was der Mensch sich innerlich erringen muß, was ihm nicht durch äußere staatliche Einrichtungen gegeben werden kann — um welchen Preis wollte sich denn da der Mensch diese soziale Freiheit erkaufen? Er wollte sie sich erkaufen um den Preis, daß sie ihm nicht gegeben werden könne beim logischen Nachdenken, nicht gegeben werden könne äußerlich im gewöhnlichen physischen Leben, sondern nur in der ausschließlichen Betätigung im künstlerischen Erleben.

[ 11 ] Man möchte sagen, man findet einen Abdruck dieser Empfindungen gerade bei den besten Geistern dieses Zeitalters, bei Schiller in theoretischer Form, bei Goethe, der ja praktisch dies Leben in der Freiheit geübt hat. Sehen wir uns einmal die Gestalten Goethes an, die er aus dem Leben heraus schuf und an denen er darstellen wollte das echt Menschliche, das wahrhaft Menschliche. Sehen wir uns den «Wilhelm Meister» an. Wilhelm Meister ist eine Persönlichkeit, an der Goethe das echte, wahre Menschentum darstellen wollte. Aber für das Gesamtauffassen des Lebens ist ja Wilhelm Meister im Grunde genommen ein Bummler. Er ist kein Mensch, der im höchsten Sinne des Wortes nach einer die Seele tragenden Weltanschauung sucht. Er ist auch kein Mensch, der im äußeren Leben einen Beruf, eine Arbeit ergreifen kann. Er bummelt so durch das Leben. Dem liegt zugrunde, daß eigentlich jenes Freiheitsideal, das bei Goethe und Schiller angestrebt wurde, nur erreicht werden konnte von Menschen, die sich aus dem denkerischen und arbeitsamen Leben herausreißen. Man möchte sagen, Schiller und Goethe wollten hinweisen auf die Illusion der Französischen Revolution, auf den illusionären Glauben, als ob irgend etwas Äußeres, ein Staat, dem Menschen die Freiheit geben könne. Sie wollten darauf hinweisen, wie der Mensch sich diese Freiheit nur im Inneren erringen könne.

[ 12 ] Damit ist allerdings jener große Gegensatz zwischen Mitteleuropa und dem romanischen Westeuropa gegeben. Das romanische Westeuropa glaubte in einem absoluten Sinne an die Macht des Staates, glaubt ja bis heute daran. Und in Mitteleuropa entstand dagegen die Reaktion, daß das Menschenideal eigentlich nur innerlich gefunden werden könne. Aber es geschah eben auf Kosten des sich voll Hineinstellens in das Leben. Heraus aus dem Leben mußte solch ein Mensch wie Wilhelm Meister streben.

[ 13 ] Man sieht, im ersten Anhub konnte nicht das volle Menschentum in dem wirklichen Menschen gefunden werden. Natürlich, wenn alle Menschen Künstler werden sollten, um, wie Schiller sagte, die «ästhetische Gesellschaft» zu begründen, dann würden wir vielleicht eine ästhetische Gesellschaft haben, aber sehr lebensfähig würde diese ästhetische Gesellschaft nicht sein. Ich kann mir zum Beispiel, um gleich etwas Radikales zu sagen, nicht recht vorstellen, wie in dieser ästhetischen Gesellschaft die Kloaken geräumt würden. Ich kann mir auch nicht vorstellen, wie in dieser ästhetischen Gesellschaft mancherlei von dem geleistet werden sollte, was nun einmal nach strengen logischen Begriffen zu leisten ist. Das Ideal der Freiheit stand leuchtend vor den Menschen, aber der Mensch konnte nicht aus einem vollen Darinnenstehen im Leben nach einer Verwirklichung dieses Ideals der Freiheit streben. Es mußte jener Hinaufschwung nach dem Übersinnlichen wiederum gesucht werden, und zwar jetzt in bewußter Form, wie früher ein Herunterschwung atavistisch stattgefunden hatte; es mußte ein Wiederhinaufschwung in die geistige Welt gesucht werden. Das Ideal der Freiheit mußte festgehalten werden, aber der Aufschwung mußte gesucht werden. Man mußte zunächst die Möglichkeit gewinnen, für das Handeln des Menschen, für das Darinnenstehen im handelnden Leben die Freiheit zu sichern. Das konnte man nur, wie mir schien, auf dem Wege, der in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» vorgezeichnet ist.

[ 14 ] Wenn der Mensch sich zu jener inneren Seelenverfassung aufschwingt, durch die er überhaupt fähig wird, im reinen Gedanken, wie ich jetzt dargestellt habe, sittliche Impulse zu finden, dann wird er ein freier Mensch trotz dem völligsten Sich-Hineinstellen ins Leben. Daher mußte ich in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» einen Begriff einführen, den man sonst in Moralbeschreibungen, in Moralpredigten nicht findet: den Begriff des sittlichen Taktes, des selbstverständlichen Handelns aus sittlichem Takt, des Übergehens sittlicher Impulse in gewohnheitsmäßiges Handeln.

[ 15 ] Nehmen Sie die Rolle, die der Takt, der moralische Takt in meiner «Philosophie der Freiheit» spielt, so werden Sie sehen, wie da nicht bloß, wie in der ästhetischen Gesellschaft, in das Fühlen, sondern wie da auch in das Wollen die wirkliche menschliche Freiheit, das heißt das gesamte Menschtum eingeführt werden sollte. Derjenige Mensch, der dann überhaupt dazu gekommen ist, eine solche Seelenverfassung zu haben, daß in seinem Wollen reine Gedanken als sittliche Impulse leben können, der darf sich dann in das Leben, und wenn es sonst noch so lastend ist, hineinstellen - er wird die Möglichkeit haben, als ein freier Mensch in diesem Leben drinnenzustehen, insofern das Leben Handlung, Tat von uns verlangt.

[ 16 ] Und dazu mußte dann die Möglichkeit gesucht werden, auch für das, was Vernunftnotwendigkeit ist, was gedankliche Erfassung der Welt ist, das zu finden, was dem Menschen die Freiheit sichert, die Unabhängigkeit von dem äußeren Zwange. Das wiederum konnte nur geschehen durch anthroposophische Geisteswissenschaft. Dadurch, daß der Mensch die Möglichkeit verstehen lernt, sich in das hineinzufinden, was im Geiste von den Weltengeheimnissen und Weltenrätseln erlebt wird, lebt er sich in Gedanken mit seinem Menschtum zusammen mit dem inneren Geiste der Welt. Und er gelangt durch Freiheit in die Wissenschaft vom Geiste hinein.

[ 17 ] Was da vorliegt kann man am besten daran sehen, wie die Menschen auf diesem Gebiete eigentlich heute noch sich furchtbar sträuben, frei zu werden. Das ist wiederum ein Gesichtspunkt, von dem aus man die Gegnerschaft gegen die Anthroposophie verstehen kann. Die Menschen wollen nicht frei sein auf geistigem Gebiete. Sie wollen durch irgend etwas gezwungen, geführt, gelenkt werden. Und weil es jedem freisteht, das Geistige anzuerkennen oder abzulehnen, so lehnen die Menschen es eben ab und wählen dasjenige, demgegenüber es dem Menschen nicht freisteht, es anzuerkennen oder abzulehnen.

[ 18 ] Ob es blitzt und donnert, ob im Laboratorium durch einen gewissen Vorgang sich Sauerstoff und Wasserstoff vereinigen, darüber gibt es keinen Entschluß, es anzuerkennen, oder nicht anzuerkennen. Ob es Angeloi und Archangeloi gibt, das anzuerkennen steht dem Menschen frei. Er kann es auch leugnen. Der Mensch aber, der nun einen wirklichen Freiheitsimpuls hat, der kommt schon durch diesen Freiheitsimpuls zur Anerkennung des Geistigen im Denken. Es kann dasjenige, was als erster Anhub in Schillers Briefen «Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen», in Goethes ganzem künstlerischem Wirken enthalten war — die Verwirklichung der menschlichen Freiheit durch inneres Ringen, durch inneres Streben -, es kann das eben nur dann erreicht werden, wenn man anerkennt, daß der Mensch zu dem, was er im künstlerischen Erleben als freies Wesen hat, auch hinzufügen kann ein freies Erleben in dem Reiche des Denkens, ein freies Erleben im Reiche des Wollens, das nur in der richtigen Weise ausgebildet werden muß.

[ 19 ] Schiller nahm eben einfach das, was das intellektuelle Zeitalter dargeboten hat. Die Kunst strebte im Zeitalter Schillers noch aus diesem Intellektualismus heraus. Darin fand Schiller noch die menschliche Freiheit. Was aber der Intellektualismus dem Gedanken darbietet, ist unfrei, unterliegt dem logischen Zwang. Da erkannte Schiller nicht die Möglichkeit an, daß Freiheit walte, ebensowenig im Handeln, im gewöhnlichen harten Leben. Das mußten wir uns erst erringen durch die Einführung anthroposophischer Geisteswissenschaft, daß die Freiheit auch anerkannt werden konnte auf dem Gebiete des Denkens und auf dem Gebiete des Wollens. Denn Schiller und Goethe erkannten sie nur an auf dem Gebiete des Fühlens.

[ 20 ] Aber ein solcher Weg zur vollen Anerkennung der menschlichen Freiheit ist ja nur möglich, wenn der Mensch auch zu einer inneren Anschauung von dem Zusammenhang dessen, was ihm in der Seele als Geistiges erlebbar ist, mit dem Natürlichen kommt. Solange wie zwei abstrakte Begriffe, Natur und Geist, nebeneinander stehen für die menschliche Anschauung, so lange kann der Mensch nicht in einem solchen Sinne zu einer wirklichen Auffassung der Freiheit fortschreiten, wie ich es angeführt habe. Derjenige, der, ohne daß er sich selber durch Meditation, Konzentration und so weiter in die geistige Welt hineinlebt, der nur durch seinen gesunden Menschenverstand das anerkennt, was durch Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition gefunden ist, der erlebt aber bei diesem Anerkennen durchaus etwas. So zum Beispiel wird jemand, der einfach in den Büchern liest oder in Vorträgen hört - ohne daß er dabei schläft - was durch Imagination aus der Welt hervorgeholt wird, der wird schon nötig haben, sich anders an diese Offenbarungen der geistigen Welt heranzumachen als an das, was in einem heutigen Physik- oder Chemiebuche oder in einer Botanik oder in einer Zoologie geschrieben ist, obwohl alles durch den gesunden Menschenverstand geschehen kann.

[ 21 ] Man kann, ohne innerlich viel zur Aktivität überzugehen, alles das aufnehmen, was in einer heutigen Botanik oder Zoologie geschrieben ist. Man kann aber nicht, ohne sich innerlich in Tätigkeit, in Aktivität zu versetzen — wie es aber durchaus im gesunden Menschenverstand möglich ist -, das aufnehmen, was zum Beispiel in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft im Umriß» dargestellt ist. Alles kann begriffen werden, und wer da sagt, es sei unbegreiflich, der will einfach nicht innerlich aktiv mit seinem Denken vorgehen, sondern er will es so passiv nehmen, wie man die Vorstellungen eines Kinos passiv hinnimmt. Da braucht man allerdings sein Denken nicht viel in Bewegung zu setzen, und so möchten die Menschen heute alles hinnehmen. Sie können auch das, was im Laboratorium dargeboten ist, so hinnehmen. Dasjenige, was in meiner «Geheimwissenschaft» gesagt wird, das kann so nicht hingenommen werden. Höchstens stellt es sich manchmal heraus, daß gewisse Professorengemüter das so hinnehmen möchten. Dann machen sie wohl den Vorschlag, daß diejenigen, die so etwas schauen, in psychologischen Laboratorien, wie man das heute nennt, sich untersuchen lassen. Es ist das ebenso gescheit, wie wenn jemand verlangen würde, daß der, welcher mathematische Probleme löst, sich untersuchen ließe, ob er fähig ist, mathematische Probleme zu lösen. Jenem wird man sagen: Wenn du einsehen willst, ob die mathematischen Probleme richtig gelöst sind, dann mußt du eben lernen, sie lösen zu können, dann kannst du es nachprüfen. — Und töricht wäre es, zu antworten: Nein, das will ich nicht, ich will nicht lernen sie nachzuprüfen, sondern ich werde dann in einem psychologischen Laboratorium untersuchen, ob es richtig gelöst ist! - Ja, so ungefähr sind die Anforderungen, die zuweilen heute von Professorengemütern gestellt werden, denen dann allerlei «Generäle» in einer böswilligen Absicht die Sache nachplappern. Sie sind töricht, sie sind dumm, diese Forderungen, aber es ist das kein Hindernis, daß diese Dinge heute mit großem Aplomb behauptet werden können.

[ 22 ] Wer sich mit innerlicher Aktivität in das hineinversetzt, was aus der Imagination stammt, der hat davon allerdings eine gewisse Frucht für seine Seele. Es bleibt ja nicht unbedeutend für die Seele, wenn jemand sich bemüht, das imaginativ Erkannte zu verstehen. Es gibt gewisse Heilmittel, die auf diese oder jene Krankheitszustände des Menschen wirken. Heute ist es schon außerordentlich schwierig, bei den Menschen Heilmittel überhaupt zur Wirksamkeit zu bringen. Wer aber sich bemüht hat, das Imaginative durch den gesunden Menschenverstand zu verstehen, der macht von seiner Lebenskraft wiederum so viel aktiv, daß Heilmittel, wenn sie die richtigen sind, bei ihm auch wiederum wirksamer werden, daß der Organismus sie nicht zurückwirft.

[ 23 ] Die Torheit redet heute davon, daß anthroposophische Medizin die Menschen durch Hypnose und Suggestion und so weiter, wie man es nennt, auf geistigem Wege heilen wolle. Sie können das in allen möglichen Blättern lesen in Anknüpfung an die Bemerkungen, die ich gerade über Medizin auf meinen Vortragsreisen in den letzten Monaten gemacht habe. Aber darum handelt es sich zunächst nicht. Es handelt sich darum, die heutige Medizin wirklich weiterzuführen durch geistige Erkenntnisse. Man kann natürlich nicht durch Einimpfen eines Gedankens heilen, doch hat trotzdem das geistige Leben, ganz konkret gefaßt, soweit eine Bedeutung für die Wirksamkeit der Heilmittel, daß derjenige, der sich bemüht, Imaginatives zu verstehen, dadurch seinen physischen Organismus geeigneter macht, für richtige Heilmittel empfänglich zu sein, wenn er sie durch seine Krankheitszustände braucht, als ein anderer, der in dem bloßen äußerlichen Intellektualismus, das heißt in dem heutigen Materialismus mit seinem Gedankensystem verharrt. |

[ 24 ] Die Menschheit wird ein Aufnehmen dessen, was imaginativ erfaßt werden kann, schon aus dem Grunde brauchen, weil sonst der physische Leib der Menschen immer mehr und mehr in solche Zustände verfallen würde, daß er gar nicht mehr geheilt werden kann, wenn er erkrankt. Denn dazu muß immer das Geistig-Seelische nachhelfen. Alles dasjenige, was an Prozessen in der Natur vorhanden ist, spricht sich ja nicht bloß aus in dem, was sichtlich vor sich geht, sondern es spricht sich so aus, daß dieses sichtlich Vor-sich-Gehende überall durchsetzt ist von Geistig-Seelischem. Will man daher eine sinnliche Substanz in dem menschlichen Organismus zur Wirksamkeit bringen, so muß man in einem gewissen Sinne das Seelisch-Geistige haben, das diese sinnliche Substanz zur Wirksamkeit bringt. Der ganze Menschheitsprozeß fordert, daß die menschliche Seelenverfassung wiederum durchsetzt werde von dem, was in seelisch-geistigem Sinne zu ergreifen ist.

[ 25 ] Man kann nun allerdings sagen: Sehnsucht ist heute viel vorhanden innerhalb der Menschheit nach diesem Seelisch-Geistigen. Aber diese Sehnsucht bleibt vielfach im Unbewußten und Unterbewußten stekken. Und das, was die Menschen im Bewußtsein haben, was ja ganz und gar ein bloßer Rest des Intellektualismus ist, das lehnt sich auf, das wehrt sich gegen das Spirituelle, und es ist zuweilen grotesk, wie man sich wehrt gegen dieses Spirituelle. Es wird zumeist vor Eurythmievorstellungen von mir auseinandergesetzt, wie das Eurythmische auf einer wirklichen sichtbaren Sprache beruht; ebenso wie die Lautsprache aus Einrichtungen des Organismus heraus sich entwickelt, so auch die sichtbare Sprache der Eurythmie. So wie Laut um Laut, Selbstlaut, Mitlaut, alle Vokale und Konsonanten sich herausringen in Anlehnung an das Erleben des Menschen aus dem menschlichen Organismus, so wird in der Eurythmie sichtbarlich Laut für Laut herausgeholt, und es wird da nun wirklich gesprochen. Man müßte glauben, daß nun die Menschen, denen solches Eurythmisches vorgeführt wird, versuchen würden, sich vor allen Dingen hineinzufinden in den Grundimpuls, daß Eurythmie eben eine Sprache ist.

[ 26 ] Gewiß, vielleicht wird man nicht gleich darauf kommen, wie das gemeint ist. Man kann aber unschwer bald sich hineinfinden in das, was da gemeint ist, wenn man ernstlich dazu den Willen hat. Aber da habe man neulich - in Berlin nennt man es Ulkiges - etwas ungemein Ulkiges gelesen als Kritik einer Eurythmievorstellung. Da sagte jemand: Ja, das Unmögliche dieser Eurythmievorstellungen zeigte sich darin, daß die Leute zuerst Ernstes, Seriöses darstellten und nachher Humoristisches, und sonderbarerweise - so fand der geistvolle Kritiker heraus -— wurde das Humoristische mit denselben Bewegungen dargestellt wie das Ernste, Seriöse. Sehen Sie, er hat soviel von der Sache verstanden, daß er glaubt, es müßte das Humoristische mit andern Lautzeichen dargestellt werden als das Ernste, Seriöse! Wenn man ernst zu verstehen vermag, daß Eurythmie eine wirklich sichtbare Sprache ist, dem entspräche, daß eine jede Sprache für das Ernste eigene Laute braucht und für das Komische wieder andere Laute! Also wenn jemand in der deutschen oder französischen Sprache zu deklamieren begänne, dann würde er sich vielleicht des «I», des «U» und so weiter bedienen, aber er müßte, wenn er dann Humoristisches deklamierte, andere Laute haben. Ich weiß nicht, wie viele Leute darauf gekommen sind, wie dieser Kritiker einer der ersten deutschen Zeitungen Blitzdummes zutage gefördert hat; aber so stellt es sich dar, wenn man es in Wirklichkeit sieht. Es ist also etwas, was bedeutet, daß in diesen Köpfen bereits jede Möglichkeit des Denkens aufgehört hat; sie können gar nicht mehr denken. Denn das ist das Ergebnis, das Fazit des Intellektualismus, wie er sich auf allen Gebieten des Lebens heute breitmacht, daß die Menschen zuerst ihre Gedanken zu toten inneren Seeleninhalten werden lassen. Wie steif, wie tot sind die meisten Gedanken, die heute produziert werden, wie wenig innerliche Beweglichkeit haben sie, wie sehr sind sie nachgeäfft dem, was da oder dort vorgeschaffen ist! Wir haben in unserem Zeitalter im Grunde genommen außerordentlich wenig originelle Gedanken. Aber das, was gestorben ist - und die Gedanken unseres Zeitalters sind ja meistens gestorben -, das bleibt nicht in demselben Zustande. Sehen Sie sich einen Leichnam nach drei Tagen an, sehen Sie ihn nach fünf Jahren an, oder gar nach vierzig Jahren: das stirbt ja weiter, das verwest weiter. Und daß so etwas nicht gemerkt wird, wie die Gedanken da schon in einen Verwesungszustand gekommen sind, wenn jemand sagt: Das Unmögliche der Eurythmie zeigt sich darin, daß es für die humoristischen Sachen dieselben Bewegungen sind, wie für die ernsten —, das beruht lediglich darauf, daß die Menschen nicht in der Lage sind, ihren gesunden Menschenverstand heranzuschulen zum Beispiel an inspirierten Wahrheiten, wie sie sich in der Anthroposophie ergeben. Schult man den gesunden Menschenverstand, ohne daß man selber eine okkulte Entwickelung durchmacht, an inspirierten Wahrheiten, dann bekommt man ein feines Gefühl für die lebendige Wahrheit, für das Gesunde und Ungesunde im menschlichen Denken, im menschlichen Forschen. Und dann, verzeihen Sie den Ausdruck, dann beginnen solche Behauptungen wie die, welche ich Ihnen eben gesagt habe, zu «stinken». Dann erwirbt man sich die Möglichkeit, den Verwesungsgeruch dieser Gedanken zu riechen. Diese Fähigkeit des Riechens, die fehlt unseren Zeitgenossen eben in hohem Grade. Aber das merkt ein großer Teil unserer Zeitgenossenschaft nicht, sondern liest über diese Dinge hinweg.

[ 27 ] Es ist schon notwendig, daß man ganz gründlich hineinsieht in das, wessen da die Menschheit bedarf. Die Menschheit bedarf wirklich auch jener Freiheit in der Seelenverfassung dem Gedanken gegenüber, die nur möglich ist dadurch, daß der Mensch sich dazu aufschwingt, spirituelle Wahrheiten in sich aufzunehmen. Sonst kommen wir natürlich zu jenem Untergange der Kultur, der heute auf allen Gebieten sehr deutlich wahrzunehmen ist. Die Gesundheit des Urteils, das Unmittelbare des Eindruckes, das sind Dinge, die den Menschen wirklich schon zum großen Teile verlorengegangen sind und die nicht verlorengehen dürfen, die aber nur dann nicht verlorengehen werden, wenn der Mensch sich hindurchfindet zu dem Erfassen des Spirituellen.

[ 28 ] Es ist eben durchaus ins Auge zu fassen, daß der Mensch an der Anthroposophie einen Lebensinhalt hat, wenn er mit seinem gesunden Menschenverstand sich heranmacht an das, was durch Imagination, Inspiration und Intuition gewonnen werden kann. In der Hingabe an das imaginativ Erforschte findet der Mensch zum Beispiel jene innerliche Lebendigkeit, die ihn für Heilmittel empfänglich macht, neben anderem, neben dem zum Beispiel, daß es ihn überhaupt zu einer freien Persönlichkeit macht, die nicht für alle möglichen öffentlichen Suggestionen zugänglich ist.

[ 29 ] Durch das Hineinleben in inspirierte Wahrheiten gelangt der Mensch dazu, ein sicheres Empfinden zu haben von dem Wahren und dem Falschen. Er gelangt auch dazu, dieses sichere Empfinden im Sozialen auszuleben. Wie wenige Menschen zum Beispiel können denn heute noch zuhören! Sie können ja nicht zuhören, sie reagieren immer gleich mit ihrer eigenen Meinung. Gerade dieses Hinhören auch auf den andern Menschen, das wird in einer schönen Weise dadurch entwickelt, daß der Mensch sich mit seinem gesunden Menschenverstand in inspirierte Wahrheiten einlebt. Und das, was der Mensch für das Leben braucht: ein gewisses Loskommen von seinem eigenen Selbst, eine gewisse Selbstlosigkeit, das wird in hohem Grade entwickelt durch das Einleben in intuitive Wahrheiten. Und dieses Einleben in imaginative, inspirierte, intuitive Wahrheiten, das ist ein Lebensinhalt.

[ 30 ] Es ist natürlich bequemer, wenn gesagt wird, die Leute können einen solchen Lebensinhalt aus dem bekommen, was Waldo Trine verspricht: daß man die Dinge nur ihrem Inhalte nach durchzulesen braucht und damit einen Lebensinhalt bekommt - während es schwerer ist, sich den Lebensinhalt auf anthroposophische Weise zu verschaffen. Der kann nur arbeitend erworben werden, arbeitend in dem Hineinleben ins Imaginative oder in das imaginativ Erforschte, ins inspiriert Erforschte und ins intuitiv Erforschte. Aber dann ist das auch ein Lebensinhalt, der sich intensiv mit der menschlichen Persönlichkeit, mit dem ganzen Wesen des Menschen verbindet. Und einen solch sicheren Lebensinhalt gibt gerade dasjenige, was als Anthroposophie in die Welt treten will.

[ 31 ] Wir werden davon dann am nächsten Freitag weitersprechen, meine lieben Freunde. Für nächsten Sonntag will ich ankündigen, daß um 5 Uhr eine öffentlichen Eurythmie-Vorstellung stattfindet.

The ideal of freedom in Schiller and Goethe

[ 1 ] Various occasions have led us to consider how, in the transition from the 13th to the 14th and 15th centuries, the age of intellectualism began, the age we have often referred to as the fifth post-Atlantean culture. It is characterized precisely by the fact that in this age, human beings come to regard the intellectual as the guiding principle in all their endeavors. We have often spoken about how this intellectualism developed in the various areas of inner life. Everything that is characteristic of human development has an inner side through which it is more fully expressed in people's feelings, in their views, in their prevailing impulses of will, and so on. At the same time, however, it also has an outer side through which it lives out in the conditions that arise historically in human development, and here it must be said that, for the time being, the most significant expression of the intellectual age in history is the French Revolution, that great world movement at the end of the 18th century.

[ 2 ] Admittedly, much in human life over long periods of time has pointed to how such a type of social coexistence should be strived for, as it then found tumultuous expression in the French Revolution. And much has remained from the French Revolution, which lives on in one form or another here and there, namely in the external social conditions of humanity. One need only consider how the French Revolution represents something that would not have been possible in the way it manifested itself at the end of the 18th century, for the reason that human beings did not actually seek full satisfaction here on earth for everything they aspired to.

[ 3 ] Be clear about this: before the age of the French Revolution, there had never been an epoch in the historical development of humanity in which people had said to themselves: Everything that human beings can strive for through their thinking, feeling, and willing must also find a corresponding external expression in earthly existence itself. In the era that preceded the French Revolution, it was clear that the earth cannot provide everything that humans need for their spirit, soul, and body. Humans have always felt connected to a supernatural world and have attributed to this supernatural world the task of satisfying what cannot be satisfied on earth.

[ 4 ] However, long before the French Revolution found its tumultuous expression, people in various fields of civilized life were striving to bring about a social order that would satisfy as many human needs as possible on earth. The French Revolution, however, has its fundamental character in the fact that it simply sought to bring about a social condition that is a corresponding expression of human thinking, feeling, and willing here on earth. This is essentially the striving of intellectualism.

[ 5 ] Intellectualism has earthly existence as its domain. Intellectualism wants to satisfy everything that exists in the sensory-physical world. It therefore also wants to bring about social conditions within the physical order of the earth that are an expression of the intellectual. This striving to bring about in social conditions what human beings can strive for goes as far as the worship of the goddess of reason, which actually meant the goddess of the intellect. One can therefore say that from very ancient conditions, in which people were guided by the impulses they received from the initiates and mystery students, through which they incorporated the divine-spiritual into their social order, from those ancient conditions the social striving of humanity moved, for example, to the Egyptian conditions, where what the kings learned from the priests about the will of human evolution, as expressed in the stars, for example, was incorporated into the social order. Later, in ancient Rome, still in royal Rome, attempts were made—as indicated by the conversation between Numa Pompilius and the nymph Egeria — to bring about what social conditions should be through the exploration of the spiritual world. More and more, the interweaving of the spiritual with the sensual-social gave rise to the demand that everything on earth should be shaped in such a way that it was a direct expression of the intellect.

[ 6 ] If one wants to represent such a process schematically, one must represent it in the form of a descending curve. The French Revolution stands at the lowest point (see drawing), from where things had to start moving upward again. This upward movement was immediately attempted as a reaction to the French Revolution, and we can see clearly how, for example, Schiller — we can read it in his letters “On Aesthetic Education” — was inspired by what was expressed outwardly in the French Revolution to seek a connection to the spiritual world within human beings. For Schiller, the question arose: If it is impossible to bring about a perfect social order here on earth, how can human beings attain what can satisfy them in terms of their thinking, feeling, and willing; how can human beings attain freedom on this earth?

[ 7 ] And Schiller answered this question by saying: If man lives logically, according to the necessity of reason, then he is merely a servant of the necessity of reason; he is not a free being. If man follows his sensual drives, his mere instincts, then he obeys the necessity of nature; he is not a free being. And Schiller came to say to himself: In fact, man is a free being only when he either creates artistically or enjoys art. Freedom can only be realized in the world through man's artistic work or artistic enjoyment. In artistic contemplation, what is otherwise the compulsion of rational necessity or the compulsion of natural necessity, as Schiller puts it, is balanced out. By living in the artistic realm, humans do not feel the same compulsion of thought in art objects as they do in logical research. Even in what confronts them through the senses, they do not perceive sensual stimuli, but rather the sensual stimulus is ennobled by intellectual contemplation in the artistic realm. Insofar as he is a being capable of art, man is therefore also capable of developing freedom within earthly existence.

[ 8 ] Schiller thus seeks to answer the question: How can man, as a social being, attain freedom? And he comes to the answer that man can only attain freedom as a being receptive to art, that he cannot be free in devotion to rational necessity, nor in devotion to natural necessity.

[ 9 ] This came to expression in a magnificent way at the time when Schiller was writing his letters “On the Aesthetic Education of Man,” precisely in the mutual exchange between Goethe and Schiller. This is evident in how Schiller received what Goethe was reworking at the time in his “Wilhelm Meister,” how he was enthralled by this mode of representation, by this inner representation of freedom, because Goethe, as an artist, was not at all an intellectualist, but rather a spirit creating in free thought, who, on the other hand, remained entirely within the realm of sensual experience in art. Schiller sensed this. He perceived Goethe's artistic activity as free as the play of a child. And we see how enthusiastic Schiller is about this free artistic activity of human beings, which is reminiscent of the play of a child. This inspired him to say: “The artist is the only true human being, and the best philosopher is only a caricature of him” — as he wrote in a letter to Goethe. But it also inspired him to say: “Man is only completely human when he plays, and he only plays when he is completely human.” This does not mean frivolous or entertaining play, but rather artistic activity and artistic enjoyment. It means lingering in artistic experience, and it means the true liberation of man.

[ 10 ] Now, at what price did people want to buy this social freedom, where they were striving to rise again from what had been sought as social order in the French Revolution to something that human beings must achieve within themselves, something that cannot be given to them by external state institutions? They wanted to buy it at the price that it could not be given to them through logical thinking, could not be given to them externally in ordinary physical life, but only through exclusive activity in artistic experience.

[ 11 ] One might say that one finds an imprint of these feelings precisely in the best minds of this age, in Schiller in theoretical form, in Goethe, who indeed practiced this life in freedom. Let us take a look at the characters Goethe created from life, in whom he wanted to portray what is genuinely human, what is truly human. Let us look at “Wilhelm Meister.” Wilhelm Meister is a character through whom Goethe wanted to portray genuine, true humanity. But in terms of his overall view of life, Wilhelm Meister is basically a loafer. He is not a person who, in the highest sense of the word, is searching for a worldview that will sustain his soul. Nor is he a person who can take up a profession or a job in his outer life. He drifts through life. Underlying this is the idea that the ideal of freedom to which Goethe and Schiller aspired could only be achieved by people who broke away from a life of thought and work. One might say that Schiller and Goethe wanted to point out the illusion of the French Revolution, the illusory belief that something external, a state, could give people freedom. They wanted to point out that people can only achieve this freedom within themselves.

[ 12 ] This, however, gives rise to the great contrast between Central Europe and Romanic Western Europe. Romanic Western Europe believed in the power of the state in an absolute sense, and continues to believe in it to this day. In Central Europe, on the other hand, the reaction arose that the ideal of man could only be found within. But this came at the expense of fully engaging with life. A person like Wilhelm Meister had to strive to escape from life.

[ 13 ] It is clear that, in the first phase, it was not possible to find full humanity in real human beings. Of course, if all people were to become artists in order to establish, as Schiller said, an “aesthetic society,” then we might have an aesthetic society, but this aesthetic society would not be very viable. To say something radical, for example, I cannot really imagine how the sewers would be cleaned in this aesthetic society. Nor can I imagine how, in this aesthetic society, many of the things that must be accomplished according to strict logical concepts could be accomplished. The ideal of freedom stood shining before humanity, but humanity, fully immersed in life, could not strive for the realization of this ideal of freedom. That upward swing toward the supersensible had to be sought again, this time in a conscious form, just as a downward swing had previously taken place atavistically; an upward swing back into the spiritual world had to be sought. The ideal of freedom had to be held fast, but the upward swing had to be sought. First, it was necessary to gain the possibility of securing freedom for human action, for standing within the active life. This could only be achieved, it seemed to me, by following the path outlined in my Philosophy of Freedom.

[ 14 ] When human beings rise to that inner state of mind which enables them to find moral impulses in pure thought, as I have now described, they become free human beings despite their complete immersion in life. That is why I had to introduce a concept in my Philosophy of Freedom that is not usually found in moral descriptions or moral sermons: the concept of moral tact, of acting naturally out of moral tact, of transforming moral impulses into habitual actions.

[ 15 ] If you consider the role that tact, moral tact, plays in my Philosophy of Freedom, you will see how real human freedom, that is, the whole of humanity, should be introduced not only into feeling, as in aesthetic society, but also into willing. The person who has attained such a state of mind that pure thoughts can live as moral impulses in his will can then enter into life, however burdensome it may be, and will have the opportunity to stand within this life as a free person, insofar as life demands action and deeds from us.

[ 16 ] And to this end, it was necessary to seek the possibility of finding, even for what is a necessity of reason, what is the intellectual grasp of the world, that which secures man's freedom, his independence from external compulsion. This, in turn, could only happen through anthroposophical spiritual science. By learning to understand the possibility of finding their way into what is experienced in the spirit of the world's secrets and mysteries, human beings live in thought with their humanity together with the inner spirit of the world. And through freedom they enter into the science of the spirit.

[ 17 ] What is at stake here can best be seen in how people in this field still resist becoming free. This is another point of view from which the opposition to anthroposophy can be understood. People do not want to be free in the spiritual realm. They want to be compelled, guided, and directed by something. And because everyone is free to accept or reject the spiritual, people reject it and choose that which they are not free to accept or reject.

[ 18 ] Whether there is lightning and thunder, whether oxygen and hydrogen combine in a laboratory through a certain process, there is no decision to acknowledge or not to acknowledge this. Whether angeloi and archangeloi exist is up to the individual to acknowledge. They can also deny it. But the human being who now has a real impulse toward freedom comes, through this very impulse of freedom, to recognize the spiritual in thinking. What was contained in Schiller's letters “On the Aesthetic Education of Man” and in Goethe's entire artistic work — the realization of human freedom through inner struggle, through inner striving — can only be achieved if one recognizes that human beings can add to what they have as free beings in artistic experience a free experience in the realm of thought, a free experience in the realm of will, which only needs to be developed in the right way.

[ 19 ] Schiller simply took what the intellectual age had to offer. In Schiller's age, art still strove out of this intellectualism. In this, Schiller still found human freedom. But what intellectualism offers to thought is unfree, subject to logical compulsion. Schiller did not recognize the possibility that freedom could prevail, either in action or in ordinary, hard life. We first had to achieve this through the introduction of anthroposophical spiritual science, which recognized that freedom could also be recognized in the realm of thought and in the realm of will. For Schiller and Goethe recognized it only in the realm of feeling.

[ 20 ] But such a path to the full recognition of human freedom is only possible if human beings also come to an inner perception of the connection between what they experience in their souls as spiritual and what is natural. As long as two abstract concepts, nature and spirit, stand side by side in human perception, man cannot progress toward a real understanding of freedom in the sense I have described. Those who, without immersing themselves in the spiritual world through meditation, concentration, and so on, who recognize only through their common sense what has been found through imagination, inspiration, and intuition, nevertheless experience something in this recognition. For example, someone who simply reads books or listens to lectures—without falling asleep in the process what is brought forth from the world through imagination, will find it necessary to approach these revelations of the spiritual world differently than what is written in a modern physics or chemistry book or in a botany or zoology book, even though everything can be understood through common sense.

[ 21 ] One can, without much inner activity, take in everything that is written in a modern botany or zoology book. But one cannot, without setting oneself in motion, in activity — as is entirely possible with common sense — take in what is presented, for example, in my “Outline of Secret Science.” Everything can be understood, and anyone who says it is incomprehensible simply does not want to engage their thinking actively, but wants to take it passively, as one passively accepts the images in a movie theater. Of course, this does not require much thought, and so people today want to accept everything. They can also accept what is presented in the laboratory. What is said in my “Secret Science” cannot be accepted in this way. At most, it sometimes turns out that certain professors would like to accept it. Then they suggest that those who see such things should have themselves examined in psychological laboratories, as they are called today. This is just as sensible as if someone were to demand that those who solve mathematical problems should be examined to see whether they are capable of solving mathematical problems. One would say to them: If you want to see whether the mathematical problems have been solved correctly, then you must learn to solve them, and then you can check. And it would be foolish to reply: No, I don't want to do that, I don't want to learn how to check them, but I will go to a psychological laboratory to have them examined to see if they are solved correctly! Yes, that is roughly the kind of demands that are sometimes made today by professors, who are then parroted by all kinds of “generals” with malicious intent. These demands are foolish and stupid, but that is no obstacle to their being asserted today with great aplomb.

[ 22 ] Those who engage with inner activity in what comes from the imagination will certainly reap some benefit for their soul. It is not insignificant for the soul when someone makes an effort to understand what they have recognized through imagination. There are certain remedies that are effective for this or that human condition. Today, it is already extremely difficult to make remedies effective in people at all. But those who have made an effort to understand the imaginative through common sense activate so much of their life force that remedies, if they are the right ones, become more effective in them, so that the organism does not reject them.

[ 23 ] Foolishness today speaks of anthroposophic medicine wanting to heal people through hypnosis and suggestion and so on, as it is called, by spiritual means. You can read this in all kinds of newspapers in connection with the remarks I have just made about medicine on my lecture tours in recent months. But that is not what this is about. It is about truly advancing modern medicine through spiritual insights. Of course, one cannot heal by implanting a thought, but nevertheless, spiritual life, in a very concrete sense, has such significance for the effectiveness of remedies that those who strive to understand the imaginative thereby making their physical organism more receptive to the right remedies when they need them for their illnesses, than someone who remains stuck in mere external intellectualism, that is, in today's materialism with its system of thought.

[ 24 ] Humanity will need to take in what can be grasped imaginatively for the simple reason that otherwise the physical body of human beings would increasingly fall into such a state that it could no longer be healed when it became ill. For this, the spiritual-soul element must always help. Everything that exists in the processes of nature does not express itself merely in what is visibly going on, but in such a way that what is visibly going on is permeated everywhere by the spiritual-soul element. Therefore, if one wants to bring a sensory substance in the human organism to bear, one must in a certain sense have the spiritual-soul element that brings this sensory substance to bear. The entire human process demands that the human soul constitution be permeated by what can be grasped in a spiritual-soul sense.