The Occult Movement in the Nineteenth Century

GA 254

16 October 1915, Dornach

Lecture III

Because other matters have still to be discussed, I will add only a brief episode today to the subjects of which we have been hearing during the last few days. Still more specific details will have to be given tomorrow in connection with the Occult Movement in the nineteenth century and its relation to civilisation and culture. I must, however, insert into the course of our studies a subject that is very important. You will remember certain things I have said in connection with von Wrangell's brochure, Science and Theosophy, and when I repeat them you will realise that from the point of view of Spiritual Science great significance must be attached to the advent of materialism and the materialistic world-conception in the nineteenth century; simply to adopt an attitude of criticism would be quite wrong.

A critical attitude is always the easiest when something confronts one. It is therefore essential to realise that the current in the evolution of humanity which may be called the materialistic view of the world arose in the nineteenth century quite inevitably. It has already been amply characterised, but two aspects may be described which will make its whole significance doubly clear to us.

In the form in which it appeared in the nineteenth century, as an actual view of the world, materialism had never hitherto existed. True, there had been individual materialistic philosophers such as Democritus and others—you can read about them in my book Riddles of Philosophy—who were, so to speak, the forerunners of theoretical materialism. But if we compare the view of the world they actually held with what comes to expression in the materialism of the nineteenth century, it will be quite evident that materialism had never previously existed in that form. Least of all could it have existed, let us say, in the Middle Ages, or in the centuries immediately preceding the dawn of modern thought, because in those days the souls of men were still too closely connected with the impulses of the spiritual world. To conceive that the whole universe is nothing more than a sum-total of self-moving atoms in space and that these atoms, conglomerating into molecules, give rise to all the phenomena of life and of the spirit—such a conception was reserved for the nineteenth century.

Now it can be said that there is, and always will be, something that can be detected like a scarlet thread, even in the most baleful conceptions of the world. And if we follow this scarlet thread which runs through the evolution of humanity, we shall be bound to recognise at very least the inconsistency of the materialistic view of the world. This scarlet thread consists in the simple fact that human beings think. Without thinking, man could not possibly arrive even at a materialistic view of the world. After all, he has thought out such a view, only he has forgotten to practise this one particle of self-knowledge: You yourself think, and the atoms cannot think! If only this one particle of self-knowledge is practised, there is something to hold to; and by holding to it one will always find that it is not compatible with materialism.

But to discover the truth of this, materialism must be recognised as what it really is. As long as man had, as it were, a counterfeit idea of materialism, an idea in which spiritual impulses were still included, he could hold fast to the fragment of spirit he still sought to find in the phenomena of nature, and so forth. Not until he had cast out all spirit through the spirit—for thinking is possible only for the spirit—not until through the spirit he had cast out spirit from the structure of the universe could the materialistic view of the world confront him in all its barrenness. It was necessary that at some time man should be faced with the whole barrenness of materialism. But what is also essential here is to reflect about thinking. That is absolutely indispensable. As soon as we do so, we shall realise that the barren vista presented by materialism had necessarily to appear at some point in evolution in order that men might become aware of what actually confronts them there.

That is one aspect of the matter, but it cannot be rightly understood unless its other aspect is presented. Materialistic picture of the world—space—in space atoms, which are in movement—and this is the All. Fundamentally, it is an outer consequence, a mirage of one side of space and the atoms moving within it, that is to say, those minute particles of which, as we have shown in earlier lectures, genuine thinking will not admit the existence. But ever and again men come to these atoms. How are they found? How does man come to assume their existence?

Nobody can ever have seen atoms, for they are conjectures, inventions of the mind. Apart from the reality, therefore, there must be some instigation which prompts man to think out an atomistic world. Something must instigate the proclivity in him to think out an atomistic world—nature herself most assuredly does not lead him to form an atomistic picture of her! With a trained physicist—and I am not speaking hypothetically here for I have actually discussed such matters with physicists—with a trained physicist one can speak about these things because he has knowledge of external physics. He could never have hit upon atomism! He would have to say—as indeed was the conclusion reached by shrewder physicists in the eighties of last century: Atomism is an assumption, a working hypothesis which affords a basis for calculation; but let us be quite clear that we are not dealing with any reality.—Thoughtful physicists would prefer to keep to what they perceive with the senses, but again and again, like a cat falling on its feet, they come back to atomism.

Mention has often been made of these things since I gave the lectures on the Theosophy of the Rosicrucian in Munich,1In 1907. and if you have studied what has been elaborated through the years, you will know that the rudiments of the physical body were imparted to man on Old Saturn, that he then passed through the Old Sun and Old Moon evolutions, and then, during the Old Moon period received into his organism, into what existed of his physical organism at that time, his nerve-system.

It would, however, be quite erroneous to imagine that during the Old Moon epoch the nerve-system was similar to what presents itself today to an anatomist or physiologist. In the Old Moon epoch the nerve-system was present as archetype only, as Imagination. It did not become physical, or better said, mineral in the chemical sense, until the Earth-period. The whole ramified nerve-system we now have in our body, is a product of the Earth. During the Earth's development, mineral matter was incorporated into the imaginative archetypes of our nerve-system, as well as into the other archetypes. That is how our present nerve-system came into being.

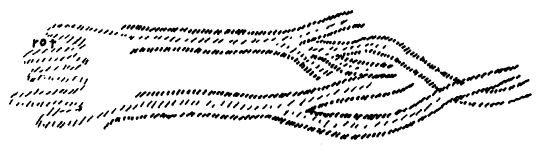

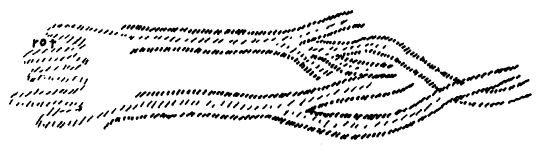

The materialist says: With this nerve-system I think, or I perceive. We know that this is nonsense. To get a correct idea of the process, let us picture the course of some nerve in the organism (see diagram). But now let us follow different nerves which run through the organism and send out ramifications, like branches. A nerve has, as it were, a stem from which branches spread out; these branches come into the neighbourhood of others and then still another filament continues on its way. (The diagram is, of course, only a very rough sketch.)

Now how does man's life of soul take its course within this nerve-system? That is the question of primary importance. We can form no true conception here if we consider the day-waking consciousness only; but if a man thinks of the moment when, together with his ego and astral body, he slips out of the body and therefore also out of the nerve-system, and especially of the moment when he slips into the body again on waking, he will have a peculiar experience. During sleep, in his ego and astral body he has been outside his nerves; he slips into the nerves again and is actually within them during his waking life; in the act of waking he feels himself streaming, as it were, from outside into the nerves.

The process of waking is much more complicated than can be conveyed in a diagram.—Through the day, together with his soul, man is within his body, filling it to the uttermost limits of the nerves. It is not as though the physical body were filled with a kind of undifferentiated mist; the organs and various organic structures are pervaded individually. As he passes into the different organs, man also slips into the sensory nerve-filaments, right to the very outermost ramifications of the nerves.

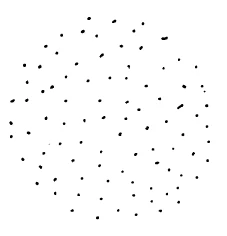

Let us try to picture it vividly.—Again I will make a sketch but can draw it only as a kind of mirrored reflection. I can draw it only from the outside, whereas in reality it ought to be drawn from within. Suppose here (diagram, p. 56) is the astral body and here the sensory “antennae” extending from it.—What I am drawing is all astral body.—It sketches certain antennae into the nerve fibres.

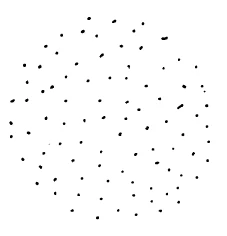

Now suppose the sleeves of my coat were sewn up and I were to slip my arm into the coat—suppose I had a hundred arms and were to slip them in this way into what would amount to sacks. With these hundred arms I should come up against the places where the sleeves are sewn up. In the same way I slip into the physical body, right to the ends of the nerve-fibres. As long as I am in the act of slipping in, I feel nothing; it is only when I reach the point where the sleeves are sewn up that I feel anything. It is the same with the nerves; we feel the nerve only at the point where it ends. Throughout the day we are within the nerve-substance, touching our nerve-ends all the time. Man does not realise this consciously but it expresses itself in his consciousness willy nilly. Now man thinks with his ego and astral body and we may therefore say: Thinking is an activity that is carried over by the ego and astral body to the etheric body. Something from the etheric body also plays a part—its movement at any rate. The cause of consciousness is that in acts of thinking I continually come to a point where an impact occurs. I make an impact at an infinite number of points but I am not conscious of this. It comes into consciousness only in the case of one who consciously experiences the process of waking; when he passes consciously into the mantle of his nerves he feels as if he were being pricked all over.

I once knew an interesting man who had become conscious of this in an abnormal way. He was a distinguished mathematician, conversant with the whole range of higher mathematics at that time. He was also, of course, much occupied with the differential and integral calculus. The “differential” in mathematics is the atomic, the very smallest unit that can be conceived—I cannot say more about it today. Although it was not a fully conscious experience, this man had the sensation of being pricked all over when he was engrossed in the study of the differential calculus. Now if this experience is not lifted into consciousness in the proper way, by such exercises as are given in the book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds. How is it achieved?—very strange things may occur. This man believed that he was feeling the differentials all over him. “I am crammed full of differentials”, he said. “I have nothing integral in me.” And moreover he demonstrated in a very ingenious way that he was full of differentials!

Now try to envisage these “pricks” vividly. What does a man do with them if they do not reach his consciousness?

He projects them into space, fills space with them—and they are then the atoms. That, in truth, is the origin of atomism. If there is a mirror in front of you and you have no idea that it is a mirror, you will certainly believe that there, outside, is another collection of people. In the same way man conceives that the whole of space is filled with what he himself projects into it. This entire nerve-process is reflected back into man owing to the fact that he comes up against it (as a kind of barrier). But he is not conscious of this and so he conceives of the whole of surrounding space as being filled with atoms: the atoms are ostensibly the pricks made by his nerve-endings. Nature herself nowhere obliges us to assume the existence of atoms, but the human constitution does. At the moment of waking man dives down into his own being and becomes inwardly aware of an infinite number of spatial points within him. At this moment he is in exactly the same position as when he walks up to a mirror, knocks up against it—and realises then that he cannot get behind it. Similarly, at the moment of waking a man comes up against his nerve-endings and knows that he cannot get beyond them. The whole atomic picture is like a reflecting-screen. The moment a man realises that he cannot get behind it, he knows how things are.

And now think of a saying of Saint-Martin which I have quoted on previous occasions. What does a natural scientist say? He says: Analyse the phenomena of nature and you find the atomic world! We, however, know that the atomic world is simply not there; the truth is that our nerve-ends alone are there. What then, is there where the atomic world is conjectured to be? Nothing is there! We must remain at the mirror, at the nerve-ends. Man is there; and man is a reflecting apparatus. When this is not recognised, all kinds of things are conjectured to lie behind him. The materialistic view of the world arises, whereas in reality, it is man who must be discovered. But this cannot happen as long as it is said: Analyse the phenomena of nature—for this results in atomism. It should rather be said: Try to get beyond what is mere semblance, try to see through semblance! And then it will not be said: ... and you find the atomic world, but rather, and you find man! And now call to mind what Saint-Martin said as a kind of prophecy without fully understanding it himself: “Dissipez vos ténèbres materiels et vous trouverez l'homme.” This is exactly the same thing, but it can only be understood with the help of what we have here been considering.

Through the way in which we are bringing Spiritual Science into connection both with Natural Science and also with its errors, we are fulfilling a longing that has existed ever since there were men who had some inkling of the fallaciousness of the modern materialistic view of the world.—When we think of the intrinsic character of our own conception of the world, the fact of untold significance that strikes us is this: Spiritual Science is there because it has been longed for by those who have had a feeling for the True, for the Truth which alone can bring that of which modern humanity stands in need.

In the lecture tomorrow I shall show you why error was bound to arise when the attempt with Spiritualism was made in the nineteenth century. I have indicated to you in many ways that it was a matter of suggestions exercised by living men, whereas it was believed that influences were coming from the dead. The dead can be reached only by withdrawing into those members of man's psychic being which can be lifted out of the physical body. The life of the human being between death and a new birth can be known only through what can be experienced outside the physical body; therefore mediums—using the word in its real meaning—cannot be used for this purpose. More about this tomorrow, when what is said will also be connected with the subject of the life after death.

Dritter Vortrag

Ich will heute -— weil noch andere Dinge zur Besprechung vorliegen — nur eine kurze Episode zu den Betrachtungen einfügen, die wir in den vorangehenden Tagen gepflogen haben. Morgen werden wir dann noch einiges Genaueres zu sagen haben über die okkulte Bewegung im 19. Jahrhundert und ihre Beziehung zur Weltkultur. Ich muß aber eben einfügen dem ganzen Gang der Betrachtung eine Sache, die sehr wichtig ist. Wenn Sie sich erinnern an die verschiedenen Auseinandersetzungen, die wir gepflogen haben, namentlich an einzelne Bemerkungen, die ich habe machen können im Anschluß an die Broschüre des Herrn von Wrangell: «Wissenschaft und Theosophie» — ich muß das noch einmal sagen, obzwar ich es schon betont habe -, so werden Sie sehen, daß man genötigt war, gerade von dem Gesichtspunkte unserer Geisteswissenschaft aus, dem Heraufkommen des Materialismus, der materialistischen Weltanschauung im 19. Jahrhundert eine große Bedeutung beizumessen, sich zu diesem Heraufkommen des Materialismus nicht bloß so zu stellen, daß man eben einfach sich kritisierend verhält.

Kritisierend sich zu verhalten, ist immer das Allerleichteste, wenn man einer Sache gegenübersteht. Es ist also nötig, so sich zu verhalten, daß man begreift, daß gerade im 19. Jahrhundert jene Strömung heraufziehen mußte in der Menschheitsentwickelung, die man eben materialistische Weltanschauung nennen kann. Charakterisiert haben wir sie ja genügend. Wir können zunächst zwei Gesichtspunkte anführen, durch welche uns die ganze Bedeutung der materialistischen Weltanschauung klarwerden kann.

In der Form, in welcher der Materialismus im 19. Jahrhundert als Weltanschauung heraufgezogen ist, war er eigentlich vorher nicht vorhanden. Gewiß, es hat einzelne materialistische Philosophen wie Demokrit und andere gegeben — Sie können darüber nachlesen in den «Rätseln der Philosophie» -, die gewissermaßen die Vorläufer dieses Materialismus als Theorie sind. Aber wenn wir ihre Weltanschauung, so wie sie wirklich ist, vergleichen mit dem, was sich in dem Materialismus des 19. Jahrhunderts ausspricht, so müssen wir sagen: In der Form, in der der Materialismus im 19. Jahrhundert Weltanschauung geworden ist, war er früher nicht da. Insbesondere konnte er so nicht vorhanden sein, sagen wir im Mittelalter oder in den Jahrhunderten, die eben der Morgenröte des neuzeitlichen Geisteslebens vorangingen. Er konnte nicht vorhanden sein, denn die Menschen hatten in ihrer Seele viel zu viel Zusammenhang noch mit den Impulsen der geistigen Welt. Sich vorzustellen, daß die ganze Welt eigentlich nichts ist als eine Summe von sich bewegenden Atomen im Raum, die sich zu Molekülen ballen, durch welches Ballen dann alle Erscheinungen des Lebens und des Geistes zustande kommen, das war erst dem 19. Jahrhundert vorbehalten.

Nun kann man sagen: eines ist da, das immerzu wie eine Art roter Faden, dem man nachgehen kann, da sein wird, selbst in den allerschlimmsten Weltanschauungen. Und wenn man diesem roten Faden nachgeht, der sich so durch die Menschheitsentwickelung hindurchschlingt, dann wird man durch diesen roten Faden zum mindesten das Unmögliche der materialistischen Weltanschauung einsehen müssen. Und dieser rote Faden ist einfach in der Tatsache bestehend, daß die Menschen denken müssen. Ohne Denken ist es nämlich unmöglich, daß der Mensch auch nur zur materialistischen Weltanschauung kommt. Er hat sie ja ausgedacht, diese materialistische Weltanschauung! Nur daß man in der materialistischen Weltanschauung vergißt, Selbsterkenntnis zu üben, nämlich das bißchen Selbsterkenntnis: Du denkst ja, und die Atome können nicht denken. - Wenn man nur dieses bißchen Selbsterkenntnis übt, so hat man etwas, woran man sich halten kann. Und hält man sich daran, dann wird man immer finden, daß es mit dem Materialismus nicht geht.

Aber um so recht zu finden, daß es mit dem Materialismus nicht geht, mußte er erst in seiner eigentlichen Gestalt ausgearbeitet sein. Bedenken Sie doch nur: solange man gewissermaßen ein verfälschtes Bild des Materialismus hatte, ein Bild, in dem immer noch geistige Impulse mitgedacht waren, da konnte man sich an das bißchen Geist, das man noch in den Naturerscheinungen und so weiter suchte, halten. Erst dann, als man allen Geist herausgeworfen hatte - durch den Geist, denn das Denken ist nur dem Geiste möglich -, erst als man durch den Geist den Geist im Weltenbilde herausgeworfen hatte, konnte einem die ganze Ode der materialistischen Weltanschauung entgegentreten. Es mußte überhaupt den Menschen einmal entgegentreten diese ganze Ode des materialistischen Weltbildes. Aber Sie sehen, notwendig ist nun dazu die Selbstbesinnung auf das Denken. Ohne das geht es nicht. Aber sobald wir nur ein wenig hinschauen auf die Selbstbesinnung des Denkens, dann müssen wir uns sagen: Es mußte einmal in der Entwickelung das ganze öde Bild des Materialismus heraufkommen, damit die Menschen gewahr werden, was sie darin haben.

So wäre der eine Punkt gekennzeichnet. Aber man versteht ihn doch nicht recht, wenn man ihn nicht auch von seiner anderen Seite aus noch kennzeichnet. Von der anderen Seite gekennzeichnet, sehen Sie: materialistisches Weltbild - Raum - im Raum Atome, die in Bewegung sind — dieses das All. Es wäre im Grunde genommen alles nur eine äußere Folgeerscheinung, ein Blendwerk der einseitigen Wirklichkeit des Raumes und der sich in ihm bewegenden Atome, also jener kleinsten Teile, von denen wir schon in den vorigen Vorträgen gezeigt haben, daß das Denken es nicht leidet, daß sie eigentlich sind. Aber man kommt immer wieder auf diese Atome zurück. Wie findet man sie eigentlich? Wie kommt der Mensch eigentlich zu der Annahme von Atomen?

Gesehen kann sie keiner haben, denn sie sind erdacht, sie sind richtig erdacht. Es muß also der Mensch eine Veranlassung haben, abgesehen von der Wirklichkeit, sich eine atomistische Welt auszudenken. Er muß durch irgend etwas veranlaßt, geneigt sein, sich eine atomistische Welt auszudenken. Die Natur selbst führt den Menschen wahrhaftig nicht dazu, sie sich atomistisch vorzustellen. Man kann gerade mit dem Physiker — ich rede hier nicht hypothetisch von etwas Ausgedachtem, sondern ich habe wirklich mit Physikern solche Gespräche geführt -, man kann gerade mit dem Physiker sich darüber unterhalten, weil er die äußere Physik kennt. Er könnte eigentlich gar nicht auf den Atomismus verfallen! Und man müßte sagen, wie auch tatsächlich schon in den achtziger Jahren die gescheiteren Physiker darauf gekommen sind: der Atomismus ist eine Annahme, eine Arbeitshypothese, damit man darin eine Abbreviatur, eine Rechenmünze habe, aber man muß sich klar sein, daß man es mit keiner Wirklichkeit zu tun hat. Denkende Physiker möchten am liebsten bei dem bleiben, was sie mit den Sinnen wahrnehmen. Aber sie fallen doch immer wieder, wie die Katze auf die Pfoten, auf den Atomismus.

Wenn Sie verfolgen, was wir im Laufe der Jahre uns erarbeitet haben - es ist schon sehr oft über diese Dinge gesprochen worden, seit ich in München die Vorträge über die «Theosophie des Rosenkreuzers» gehalten habe —, wenn Sie das verfolgen, werden Sie sehen, daß der Mensch die Anlage zu dem physischen Körper auf dem alten Saturn erhalten hat, daß er dann nach und nach durch die Sonnen- und Mondenentwickelung hindurchgegangen ist und dann in der alten Mondenzeit eingegliedert bekommen hat in seinen Organismus, in das, was da_ zumal von seinem physischen Organismus vorhanden war, sein Nervensystem.

Nun stellt man sich aber die Sache ganz falsch vor, wenn man meinen würde, das Nervensystem wäre während der alten Mondenzeit so gewesen, wie es sich heute einem Anatomen oder Physiologen darstellt. Das Nervensystem war in der Mondenzeit eigentlich nur als Urbild, als Imagination vorhanden. Physisch, oder besser mineralisch, so wie es physisch-chemisch ist, ist es erst während der Erdenzeit geworden. Und die ganze Gliederung, wie sie jetzt in unserem Körper sitzt, ist ein Ergebnis der Erdenorganisation. Während der Erdenorganisation wurde das Mineralische, die Materie, in die imaginativen Urbilder unseres Nervensystems wie auch in die anderen Urbilder hineingegliedert. Und dadurch entstand unser jetziges Nervensystem.

Nun, der Materialist sagt sich: Mit diesem Nervensystem denke ich oder nehme ich wahr. - Wir wissen, daß das ein Unsinn ist. Denn wenn wir uns den Vorgang wirklich vorstellen wollen, so können wir uns irgendeinen Nerven vorstellen, der im Organismus verläuft. Stellen wir uns nun aber verschiedene Nerven vor, die im Organismus verlaufen. Diese verlaufen dann so, daß sie Verzweigungen wie Äste aussenden. Ein Nerv verläuft gewissermaßen so, daß er einen Stamm hat und dann Äste aussendet; es ist sogar so, daß Äste in die Nähe von anderen Ästen kommen und daß dann da ein anderer Strang weitergeht. Das ist ja nur schematisch und ungenau gezeichnet.

Wie verläuft denn eigentlich nun das menschliche Seelenleben innerhalb dieses Nervensystems? Das ist die Frage, die wir vor allen Dingen aufstellen müssen. Man gelangt zu keiner Vorstellung davon, wie das Seelenleben im Nervensystem verläuft, wenn man nur das tagwache Bewußtsein ins Auge faßt. Sobald der Mensch aber den Moment ins Auge faßt, wo er mit seinem Ich und mit seinem astralischen Leibe aus dem Nervensystem herausschlüpft -— herausschlüpft aus dem ganzen Leibe und damit also auch aus dem Nervensystem -, und insbesondere den Moment, wo er beim Aufwachen wiederum hineinschlüpft, dann merkt er die eigentümliche Erscheinung: man ist eigentlich während des Schlafes außerhalb seiner Nerven gewesen, das heißt mit seinem astralischen Leibe und seinem Ich. Man schlüpft wieder in seine Nerven hinein, man steckt dann wirklich darinnen. Erst fühlt man sich außerhalb gestellt und dann wie in die Nerven hineinfließend. Also besonders beim Aufwachen schlüpft man so in seine Nerven hinein.

Der Prozeß des Aufwachens ist viel komplizierter, als man zunächst ihn schematisch darstellen kann. Und so ist man eigentlich den Tag über mit seiner Seele so in seinem Leibe darinnen, daß man außerdem, wie man sonst mit seinem astralischen Leibe ausfüllt seinen physischen Leib, die Nerven ausfüllt. Dieses Ausfüllen ist nicht so, daß man wie mit einer Art Nebel den physischen Leib ausfüllt, sondern man füllt ihn organisierend aus. Indem man sich in die verschiedenen Organe hineinbegibt, schlüpft man auch wie mit Fühlfäden bis in die äußersten Verzweigungen der Nerven hinein.

Stellen Sie sich das bitte ganz lebhaft vor. Ich will es noch einmal schematisch zeichnen, ich kann es aber nur so zeichnen, daß es gewissermaßen verkehrt, wie eine Art Spiegelbild ist. Ich muß von außen zeichnen, müßte aber von innen zeichnen. Nehmen wir an, das wäre der astralische Leib und das wären die Fühlfäden, die er ausstreckt (rot). Das ist alles astralischer Leib, was ich jetzt zeichne. Hier streckt er gewisse Fühlfäden in die Nervenstränge hinein. Das zeichne ich so.

Also wirklich, hier schlüpft er in die Nervenstränge hinein. Denken Sie sich, mein Rockärmel wäre da vorne zugenäht und ich würde mit meinem Arm wie in einen Sack hineinschlüpfen. Denken Sie sich, ich würde hundert Arme haben und würde sie so in Säcke hineinstecken, dann würde ich mit den hundert Armen da so anstoßen, wo die Ärmel zugenäht sind. So schlüpfen wir also hinein bis dahin, wo der Nervenstrang endet. Das kann man im physischen Leibe verfolgen, wo der Nervenstrang endigt, und bis dahin schlüpft man hinein. Solange ich da hineinschlüpfe, fühle ich nichts. Ich fühle nur, wenn ich dahin komme, wo der Ärmel zugenäht ist. Ebenso ist es mit den Nerven: wir fühlen den Nerv nur da, wo er endet. Wir stecken den ganzen Tag in der Nervenmaterie und berühren immer die Enden unserer Nerven. Das bringt sich der Mensch zwar nicht zum Bewußtsein, aber es kommt in seinem Bewußtsein zum Ausdrucke, ohne daß er es will. Wenn er nun denkt - und er denkt ja mit seinem Ich und astralischen Leibe -, so können wir sagen: das Denken ist eine Tätigkeit, die da ausgeübt wird und sich vom Ich und astralischen Leib auf den Ätherleib überträgt. Vom Ätherleib schlüpft auch noch etwas da hinein, wenigstens seine Bewegung. Das, was die Ursache des Bewußtseins ist, das ist, daß ich immer mit dem Denken an einen Punkt komme, wo ich anstoße. An unendlich viele Punkte stoße ich an, wenn ich da hineinschlüpfe, nur kommt es mir nicht zum Bewußtsein. Zum Bewußtsein kommt es nur dem, der den Prozeß des Aufwachens bewußt erlebt: Wenn er bewußt hineintaucht in den Nervenmantel, dann spürt er, daß es ihm überall entgegensticht.

Ich habe sogar einmal einen interessanten Menschen kennengelernt, der in abnormer Weise dies in sein Bewußtsein bekommen hat, was ich in der folgenden Weise darstellen möchte. Der Mensch war ein ausgezeichneter Mathematiker und bewandert in dem ganzen damaligen Stande der höheren Mathematik. Er hatte sich natürlich auch viel beschäftigt mit Differential- und Integralrechnung. Differential ist in der Mathematik das Atomistische, das Kleinste, das, was noch als Kleinstes vorgestellt werden kann. Mehr kann ich heute darüber nicht sagen. Da kam nun, ohne daß es so eigentlich über die Schwelle des Bewußtseins herauftauchte, dem Manne das zum Bewußtsein, daß er da überall gestochen wird, wenn er so hineinfährt. Wenn es nicht regelrecht zum Bewußtsein kommt, wie es durch die Übungen in «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?» zum Bewußtsein gebracht werden kann, so können dabei ungewöhnliche Dinge auftreten. So glaubte er überall bei sich zu empfinden die Differentiale, er war voll von Differentialen, überall fühlte er die Differentiale. Ich bin voller Differentiale — sagte er -—, ich bin überhaupt nicht integral. — Das bewies er auch auf eine sehr scharfsinnige Weise, daß er überall von Differentialen strotze.

Stellen Sie sich lebendig diese Stiche vor. Was tut der Mensch damit, wenn sie nicht in sein Bewußtsein heraufkommen? Er projiziert sie in den Raum und füllt den Raum damit aus, und das sind dann die Atome. Das ist in Wahrheit der Ursprung des Atomismus. Gerade so macht es der Mensch, wie Sie es machen würden, wenn da vor uns ein Spiegel wäre und Sie keine Ahnung hätten, daß da ein Spiegel ist. Sie würden sicherlich glauben, da draußen wäre noch eine Versammlung von Menschen. Deshalb stellt der Mensch sich den ganzen Raum erfüllt vor von dem, was er da hineinprojiziert. Dieser ganze Nervenprozeß spiegelt sich in den Menschen zurück wegen des Umstandes, daß er da anstößt. Aber das ist dem Menschen nicht bewußt, daß er da anstößt, und der ganze Raum ist ihm daher ringsumher scheinbar erfüllt mit Atomen. Die Atome sind die Stiche, die seine Nervenendigungen ausüben. Die Natur nötigt uns nirgends, Atome anzunehmen, aber die Menschennatur nötigt uns dazu. In dem Augenblicke, wo man im Erwachen zu sich selbst kommt, taucht man in sich unter und man wird in sich gewahr eine unzählige Anzahl von Raumpunkten. In diesem Augenblicke ist man gerade in derselben Lage, in der man sich befindet, wenn man einem Spiegel entgegengeht, man stößt daran an und weiß dann, daß man nicht dahinter kann. Ähnlich ist es beim Aufwachen. In demselben Momente, wo man aufwacht, stößt man an seine Nerven an, und man weiß: da kannst du nicht hinüber, darüber kannst du nicht hinauskommen. — Es ist also das ganze Atombild so, als ob es eine Spiegelwand wäre: in dem Augenblick, wo man merkt, daß man nicht darüber hinauskommt, weiß man die Sache.

Und jetzt nehmen Sie einen Ausspruch, den ich Ihnen schon angeführt habe als von Saint-Martin herrührend. Was sagt der Naturforscher? Der Naturforscher sagt: Analysiere die Naturerscheinungen und du findest die atomistische Welt. - Wir wissen, die atomistische Welt ist nicht da. In Wahrheit sind nur unsere Nervenendigungen da. Was ist denn da, wo die atomistische Welt vermutet wird? Da ist nichts! Wir müssen stehenbleiben bei dem Spiegel, bei den Nervenendigungen. Der Mensch ist da, und der Mensch ist ein Spiegelapparat. Wenn man nicht erkennt, daß er ein Spiegelapparat ist, so vermutet man hinter ihm allerlei Zeug: nämlich die materialistische Weltanschauung, in Wahrheit muß man aber den Menschen finden. Das kann man aber nicht, wenn man sagt: Analysiere die Naturerscheinungen -, denn die geben einem ja den Atomismus. Da muß man schon sagen: Versuche, über den bloßen Schein hinwegzukommen! — Man muß also sagen: Versuche den Schein zu durchschauen! - Dann kann man aber nicht sagen: Und du findest die atomistische Welt -, sondern man muß sagen: Du findest den Menschen! - Und jetzt erinnern Sie sich an das, was wie aus einer Prophetie heraus, die er selber noch nicht völlig verstanden hat, Saint-Martin gesagt hat mit dem Satze, den ich Ihnen aufgeschrieben habe: «Dissipez vos ténèbres matérielles et vous trouverez l’homme.» Es ist derselbe Satz, es ist ganz dasselbe, nur kann es mit Hilfe der Betrachtung, die wir angestellt haben, erst verstanden werden.

Sie sehen, wir erfüllen durch die Art und Weise, wie wir zusammenbringen unsere Geisteswissenschaft mit der Naturwissenschaft und mit den Irrtümern der Naturwissenschaft, ein Programm, das in der menschlichen Sehnsucht lebt, seit es Menschen gibt, die etwas ahnten von der Unmöglichkeit der modernen materialistischen Weltanschauung. Das ist eben das unendlich Bedeutsame, das einen überkommt in seinen Wirkungen, wenn man die ganze Eigenart unserer Weltanschauung ins Auge faßt: Geisteswissenschaft ist da, weil sie ersehnt worden ist von denjenigen, die ein Gefühl hatten für das Wahre, für das, was kommen muß als die Wahrheit, die einzig und allein der Menschheit bringen kann, was die Menschheit in der neueren Zeit braucht.

Morgen werde ich Ihnen zu zeigen haben, warum gerade der Irrtum entstehen mußte, als die Probe gemacht wurde mit dem Spiritismus im 19. Jahrhundert. Wie ich Ihnen so vielfach gezeigt habe, hatte man es mit Suggestionen von lebenden Menschen zu tun, während man glaubte, daß man es zu tun habe mit Einflüssen von seiten der Toten. Diese sind nur dann zu erlangen, wenn man sich auf denjenigen Teil des psychischen Menschen zurückzieht, welcher herausgehoben werden kann aus dem physischen Leibe. Alles das, was der Mensch durchlebt zwischen dem Tode und einer neuen Geburt, kann nur erkundet werden durch das, was der Mensch außerhalb des physischen Leibes erleben kann; so daß man dazu nicht eigentlich Medien, im richtigen Sinne des Wortes, gebrauchen kann. Doch davon morgen weiter. Und das wird auch zusammenhängen mit dem Kapitel über das Leben zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt, worüber ich schon bei einer der letzten Besprechungen eine Andeutung gemacht habe, daß darüber noch einiges kommen soll.

Third Lecture

Today, because there are other things to discuss, I will only add a brief episode to the reflections we have been engaged in over the past few days. Tomorrow we will have more to say about the occult movement in the 19th century and its relationship to world culture. But I must insert one very important point into the whole course of our considerations. If you remember the various discussions we have had, particularly the individual remarks I made in response to Mr. von Wrangell's brochure, “Science and Theosophy,” — I must say this again, although I have already emphasized it — you will see that, precisely from the point of view of our spiritual science, we were compelled to attach great importance to the rise of materialism, the materialistic worldview in the 19th century, and not to respond to this rise of materialism merely by simply taking a critical stance.

It is always easiest to take a critical stance when faced with a particular issue. It is therefore necessary to understand that it was precisely in the 19th century that this trend, which can be called a materialistic worldview, had to emerge in human development. We have characterized it sufficiently. We can begin by citing two points of view that can help us understand the full significance of the materialistic worldview.

In the form in which materialism emerged as a worldview in the 19th century, it did not actually exist before. Certainly, there were individual materialistic philosophers such as Democritus and others — you can read about them in “The Riddles of Philosophy” — who were, in a sense, the precursors of this materialism as a theory. But when we compare their worldview, as it really is, with what is expressed in 19th-century materialism, we must say: In the form in which materialism became a worldview in the 19th century, it did not exist before. In particular, it could not have existed in this form in, say, the Middle Ages or in the centuries that preceded the dawn of modern intellectual life. It could not have existed because people's souls were still too closely connected to the impulses of the spiritual world. To imagine that the whole world is actually nothing more than a sum of moving atoms in space, which clump together to form molecules, through which clumping all phenomena of life and spirit come about, was something reserved for the 19th century.

Now one can say: there is one thing that will always be there, like a kind of red thread that one can follow, even in the very worst worldviews. And if one follows this red thread, which winds its way through human development, then one will at least have to recognize the impossibility of the materialistic worldview. And this common thread simply consists in the fact that human beings must think. Without thinking, it is impossible for human beings to arrive at even a materialistic worldview. They have thought it up, this materialistic worldview! Except that in the materialistic worldview, one forgets to practice self-knowledge, namely that little bit of self-knowledge: You think, and atoms cannot think. If you practice just this little bit of self-knowledge, you have something to hold on to. And if you hold on to it, you will always find that materialism does not work.

But in order to truly realize that materialism does not work, it first had to be worked out in its actual form. Just consider: as long as one had, so to speak, a distorted picture of materialism, a picture in which spiritual impulses were still included, one could hold on to the little bit of spirit that one still sought in natural phenomena and so on. Only when all spirit had been thrown out — through the spirit, for thinking is only possible through the spirit — only when the spirit had been thrown out of the world picture through the spirit, could the whole ode of the materialistic worldview confront us. This whole ode of the materialistic worldview had to confront human beings at some point. But you see, what is necessary for this is self-reflection on thinking. Without that, it is not possible. But as soon as we look a little at the self-reflection of thinking, we must say to ourselves: the whole bleak picture of materialism had to arise at some point in development so that people would become aware of what they have in it.

So that would be one point. But you don't really understand it unless you also look at it from the other side. Look at it from the other side: the materialistic worldview — space — atoms in motion within space — this is the universe. Basically, it would all be just an external consequence, an illusion of the one-sided reality of space and the atoms moving in it, i.e., those smallest particles which, as we have already shown in previous lectures, thinking cannot tolerate as actually existing. But we always come back to these atoms. How do we actually find them? How does man actually come to the assumption of atoms?

No one can see them, because they are imagined, they are correctly imagined. So man must have a reason, apart from reality, to imagine an atomistic world. He must be prompted by something, inclined to imagine an atomistic world. Nature itself does not really lead people to imagine it atomistically. One can talk about this with physicists in particular — I am not speaking hypothetically about something imagined, but have actually had such conversations with physicists — because they know external physics. They could not possibly fall for atomism! And one would have to say, as the more intelligent physicists already realized in the 1980s: atomism is an assumption, a working hypothesis, so that one has an abbreviation, a coin of exchange, but one must be clear that one is not dealing with reality. Thinking physicists would prefer to stick to what they perceive with their senses. But they always fall back, like a cat on its feet, on atomism.

If you follow what we have worked out over the years – these things have been discussed very often since I gave the lectures on the “Theosophy of the Rosicrucians” in Munich – if you follow this, you will see that human beings received the predisposition for the physical body on ancient Saturn, that they then gradually passed through the solar and lunar developments, and then, in the ancient lunar period, had their nervous system integrated into their organism, into what was already present there, especially in their physical organism.

However, it would be completely wrong to imagine that the nervous system during the old lunar period was as it appears today to an anatomist or physiologist. During the lunar period, the nervous system actually existed only as an archetype, as an imagination. It only became physical, or rather mineral, as it is physical-chemical, during the earth period. And the entire structure, as it now exists in our body, is a result of the Earth organisation. During the Earth organisation, the mineral, the matter, was integrated into the imaginative archetypes of our nervous system as well as into the other archetypes. And this is how our current nervous system came into being.

Now, the materialist says to himself: With this nervous system, I think or perceive. We know that this is nonsense. For if we really want to imagine the process, we can imagine any nerve running through the organism. But let us now imagine different nerves running through the organism. These then run in such a way that they send out branches like tree branches. A nerve runs, so to speak, in such a way that it has a trunk and then sends out branches; it is even the case that branches come close to other branches and that another strand then continues. This is only a schematic and imprecise drawing.

How does the human soul life actually function within this nervous system? That is the question we must ask ourselves above all else. It is impossible to form any idea of how the soul life functions in the nervous system if we only consider waking consciousness. But as soon as a person considers the moment when they slip out of the nervous system with their ego and their astral body — slip out of their entire body and thus also out of the nervous system — and especially the moment when they slip back in again upon waking up, they notice the peculiar phenomenon: during sleep, one has actually been outside one's nerves, that is, with one's astral body and one's ego. One slips back into one's nerves, and then one is really inside them. First one feels oneself to be outside, and then as if flowing into the nerves. So, especially when waking up, one slips into one's nerves in this way.

The process of waking up is much more complicated than can be schematically represented at first glance. And so, throughout the day, one is actually inside one's body with one's soul in such a way that, in addition to filling one's physical body with one's astral body, one also fills one's nerves. This filling is not like filling the physical body with a kind of mist, but rather filling it in an organizing way. By entering the various organs, one also slips into the outermost branches of the nerves as if with sensory threads.

Please imagine this very vividly. I will draw it schematically once more, but I can only draw it in such a way that it is, in a sense, reversed, like a kind of mirror image. I have to draw from the outside, but I should be drawing from the inside. Let's assume that this is the astral body and these are the feelers it extends (red). Everything I am now drawing is the astral body. Here it extends certain feelers into the nerve strands. I draw it like this.

So really, here it slips into the nerve strands. Imagine that my skirt sleeve was sewn up at the front and I was slipping my arm into it as if into a sack. Imagine I had a hundred arms and I put them into sacks like that, then I would bump into the place where the sleeves are sewn shut with my hundred arms. So we slip in until we reach the end of the nerve strand. You can follow this in the physical body, where the nerve strand ends, and you slip in until you reach that point. As long as I slip in there, I feel nothing. I only feel when I get to where the sleeve is sewn shut. It is the same with the nerves: we only feel the nerve where it ends. We are stuck in the nerve matter all day long and always touch the ends of our nerves. People are not conscious of this, but it is expressed in their consciousness without them wanting it to be. When they think — and they think with their ego and astral body — we can say that thinking is an activity that is carried out there and transferred from the ego and astral body to the etheric body. Something else slips in from the etheric body, at least its movement. The cause of consciousness is that I always come to a point with my thinking where I encounter resistance. I encounter an infinite number of points when I slip in there, but I am not conscious of them. Only those who consciously experience the process of awakening become aware of this: when they consciously dive into the nerve sheath, they feel that it pricks them everywhere.

I once even met an interesting person who became aware of this in an abnormal way, which I would like to describe in the following manner. This person was an excellent mathematician and well versed in the entire state of higher mathematics at that time. Of course, he had also dealt extensively with differential and integral calculus. In mathematics, the differential is the atomistic, the smallest, that which can still be imagined as the smallest. I cannot say more about this today. Then, without it actually crossing the threshold of consciousness, the man became aware that he would be pricked everywhere if he went in like that. If it does not come to consciousness in the proper way, as it can be brought to consciousness through the exercises in “How to Attain Knowledge of Higher Worlds,” unusual things can occur. So he believed he could feel the differentials everywhere, he was full of differentials, he felt the differentials everywhere. I am full of differentials, he said, I am not integral at all. He also proved in a very astute way that he was brimming with differentials everywhere.

Imagine these pricks vividly. What does a person do with them if they do not come up into his consciousness? He projects them into space and fills the space with them, and these are then the atoms. This is in truth the origin of atomism. This is exactly what people do, just as you would do if there were a mirror in front of us and you had no idea that there was a mirror there. You would certainly believe that there was still a gathering of people out there. That is why people imagine the whole space filled with what they project into it. This whole nervous process is reflected back in people because of the fact that they bump into it. But humans are not aware that they encounter it, and therefore the entire space around them appears to be filled with atoms. The atoms are the pricks that their nerve endings exert. Nature does not compel us to accept atoms anywhere, but human nature compels us to do so. The moment one awakens to oneself, one sinks into oneself and becomes aware of an innumerable number of points in space. At that moment, one is in exactly the same situation as when one approaches a mirror, one encounters it and then knows that one cannot go behind it. It is similar when one wakes up. At the very moment when you wake up, you bump into your nerves, and you know: you cannot go beyond that, you cannot get past it. — So the whole atomic image is like a mirror wall: the moment you realize that you cannot get past it, you know the truth.

And now take a saying that I have already quoted to you as coming from Saint-Martin. What does the natural scientist say? The natural scientist says: Analyze the phenomena of nature and you will find the atomistic world. — We know that the atomistic world is not there. In truth, only our nerve endings are there. What is there where the atomistic world is supposed to be? There is nothing! We must stop at the mirror, at the nerve endings. Man is there, and man is a mirror apparatus. If one does not recognize that he is a mirror apparatus, one suspects all kinds of things behind him: namely, the materialistic worldview. But in truth, one must find the human being. However, one cannot do this if one says: Analyze the phenomena of nature — for they give one atomism. One must say: Try to get beyond mere appearances! — One must say: Try to see through appearances! — But then one cannot say: And you will find the atomistic world — instead, one must say: You will find the human being! And now remember what Saint-Martin said, as if from a prophecy that he himself did not yet fully understand, with the sentence I wrote down for you: “Dissipez vos ténèbres matérielles et vous trouverez l'homme.” It is the same sentence, it is exactly the same, only it can be understood with the help of the consideration we have made.

You see, by bringing together our spiritual science with natural science and with the errors of natural science, we are fulfilling a program that has lived in human longing since there have been people who sensed something of the impossibility of the modern materialistic worldview. This is precisely the infinitely significant thing that overwhelms one in its effects when one considers the whole peculiarity of our worldview: spiritual science exists because it was longed for by those who had a feeling for the true, for what must come as the truth that alone can bring humanity what humanity needs in modern times.

Tomorrow I will show you why this error was bound to arise when spiritualism was tried out in the 19th century. As I have shown you many times, people were dealing with suggestions from living human beings, while believing that they were dealing with influences from the dead. These can only be attained by withdrawing to that part of the psychic human being which can be lifted out of the physical body. Everything that a human being experiences between death and a new birth can only be explored through what a human being can experience outside the physical body; so that one cannot really use mediums, in the true sense of the word, for this purpose. But more on that tomorrow. And this will also be related to the chapter on life between death and a new birth, about which I already hinted in one of the last discussions that there is still more to come.