The Arts and Their Mission

GA 276

20 May 1923, Kristiana

Lecture VIII

The day before yesterday I tried to show that the anthroposophical knowledge which accompanies an inner life of the soul does not estrange one from artistic awareness and creation. On the contrary, whoever takes hold of Anthroposophy with full vitality opens up within himself the very source of such activity. And I indicated how the meaning of any art is best read through its own particular medium.

After discussing architecture, the art of costuming, and sculpture, I went on to explain the experience of color in painting, and took pains to show that color is not merely something which covers the surface of things and beings, but radiates out from them, revealing their inner nature.

For instance, I pointed out that green is the image of life, revealing the life of the plant world. Though it has its origin in the plant's dead mineral components, it is yet the means whereby the living shows forth in a dead image. It is fascinating that life can thus reveal itself. In that connection, consider how the living human figure appears in the dead image of sculpture; how life can be expressed through dead, rigid forms. In green we have a similar case in that it appears as the dead image of life without laying claim to life itself.

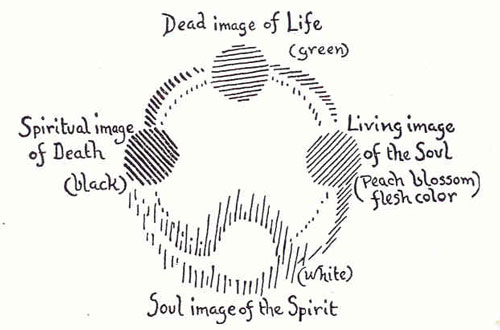

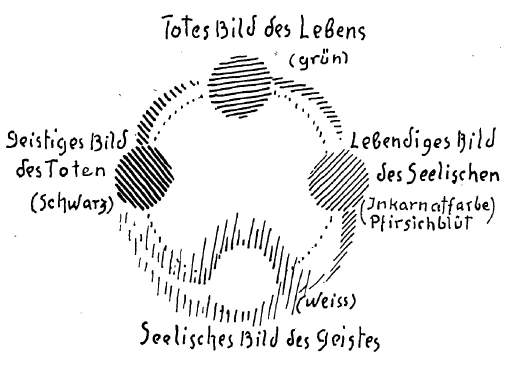

I shall repeat still other details from the last lecture in order to show how the course of the world moves on, then returns into itself; and shall do this by presenting the colors which make up its various elements: life, soul, spirit. I said I would draw this complete circle of the cosmic in the world of color. As I told you before, green appears as the dead image of life; in green life lies, as it were, concealed.

If we take the flesh color of Caucasian man, which resembles spring's fresh peach-blossom color, we have the living image of the soul. If we contemplate white in an artistic way, we have the soul image of the spirit. (The spirit as such conceals itself.) And if, as artists, we take hold of black, we have the spiritual image of death. And the circle is closed.

I have apprehended green, flesh color, white and black in their aesthetic manifestation; they represent the self-contained life of the cosmos within the world of color. If, artistically, we focus attention upon this closed circle of colors, our feeling will tell us of the need to use each of them as a self-contained image.

Naturally, in dealing with the arts I must concern myself not with abstract intellect, but aesthetic feeling. The arts must be recognized artistically. For that reason I cannot furnish conceptual proof that green, peach-blossom, white and black should be treated as self-contained images. But it is as if each wants to have a contour within which to express itself. Thus they have, in a sense, shadow natures. White, as dimmed light, is the gentlest shadow; black the heaviest. Green and peach-blossom are images in the sense of saturated surfaces; which makes them, also, shadowlike. Thus these four colors are image or shadow colors, and we must try to experience them as such.

The matter is quite different with red, yellow and blue. Considering these colors with unbiased artistic feeling, we feel no urge to see them with well-defined contours on the plane, only to let them radiate. Red shines toward us, the dimness of blue has a tranquil effect, the brilliance of yellow sparkles outward. Thus we may call flesh color, green, black and white the image or shadow colors, whereas blue, yellow and red are radiance or lustre colors. To put it another way: In the radiance, lustre and activity of red we behold the element of the vital, the living; we may call it the lustre of life. If the spirit does not wish merely to reveal itself in abstract uniformity as white, but to speak to us with such inward intensity that our soul can receive it, then it sparkles in yellow; yellow is the radiance or lustre of the spirit. If the soul wishes to experience itself inwardly and deeply, withdrawing from external phenomena and resting within itself, this may be expressed artistically in the mild shining of blue, the lustre of the soul. To repeat: red is the lustre of life, blue the lustre of the soul, yellow the lustre of the spirit.

Colors form a world in themselves and we understand them with our feelings if we experience the lustre colors red, yellow, blue, as bestowing a gleam of revelation upon the image colors, peach-blossom, green, black and white. Indeed, we become painters through a soul experience of the world of color, through learning to live with the colors, feeling what each individual color tries to convey. When we paint with blue we feel satisfied only if we paint it darker at the edge and lighter toward the center. If we let yellow speak its own language, we make it strong in the center and gradually fading and lightening toward the periphery. By demanding this treatment, each reveals its character. Thus forms arise out of the colors themselves; and it is out of their world that we learn to paint sensitively.

If we wish to represent a spiritually radiant figure, we cannot do otherwise than paint it a yellow which decreases in strength toward its edge. If we wish to depict the feeling soul, we can express this reality with a blue garment—a blue which becomes gradually lighter toward its center. From this point of view one can appreciate the painters of the Renaissance, Raphael, Michelangelo even Leonardo, for they still had this color experience.

In the paintings of earlier periods one finds the inner or color-perspective of which the Renaissance still had an echo. Whoever feels the radiance of red sees how it leaps forward, how it brings its reality close, whereas blue retreats into the distance. When we employ red and blue we paint in color-perspective; red brings subjects near, blue makes them retreat. Such color-perspective lives in the realm of soul and spirit.

During the age of materialism there arose spatial perspective, which takes into account sizes in space. Now distant things were painted not blue but small; close things not red but large. This perspective belongs to the materialistic age which, living in space and matter, prefers to paint in those elements.

Today we live in an age when we must find our way back to the true nature of painting. The plane surface is a vital part of the painter's media. Above everything else, an artist, any artist, must develop a feeling for his media. It must he so strong that—for instance—a sculptor working in wood knows that human eyes must be dug out of it; he focuses on what is concave; hollows out the wood. On the other hand, a sculptor working in marble or some other hard substance does not hollow out; he focuses his attention on, say, the brow jutting forward above the eye; takes into consideration what is convex. Already in his preparatory work in plasticine or clay he immerses himself in his material. The sculptor in marble lays on; the woodcarver takes away, hollows out. They must live with their material; must listen and understand its vital language.

The same is true of color. The painter feels the plane surface only if the third spatial dimension has been extinguished; and it is extinguished if he feels the qualitative character of color as contributing another kind of third dimension, blue retreating, red approaching. Then matter is abolished instead of—as in spatial perspective—imitated. Certainly I do not speak against the latter. In the age which started with the fifteenth century it was natural and self-evident, and added an important element to the ancient art of painting. But today it is essential to realize that, having passed through materialism, it is time for painting to return to a more spiritual conception, to return to color-perspective.

In discussing any art we must not theorize but (I repeat) abide, feelingly, within its own particular medium. In speaking about mathematics, mechanics, physics, we must kill our feeling and use only intellect. In art, however, real perception does not come by way of intellect, art historians of the nineteenth century notwithstanding. Once a Munich artist told me how he and his friends, in their youth, went to a lecture of a famous art historian to find out whether or not they could learn something from him. They did not go a second time, but coined an ironical derogatory phrase for all his theorizing. What can be expressed through the vital weaving of colors can also be expressed through the living weaving of tones. But the world of tones has to do with man's inner life (whereas the sculptor in three-dimensional space and the painter on a two-dimensional plane express what manifests etherically in space). With the musical element we enter man's inner world, and it is extremely important to focus attention upon its meaning within the evolution of mankind.

Those of my listeners who have frequently attended my lectures or are acquainted with anthroposophical literature know that we can go back in the evolution of mankind to what we call the Atlantean epoch when the human race, here on earth, was very different from today, being endowed with an instinctive clairvoyance which made it possible to behold, in waking dreams, the spiritual behind the physical. Parallel to this clairvoyance man had a special experience of music. In those ancient days music gave him a feeling of being lifted out of the body. Though it may seem paradoxical, the people of those primeval ages particularly enjoyed the chords of the seventh. They played music and sang in the interval of the seventh which is not today considered highly musical. It transported them from the human into the divine world.

During the transition from the experience of the seventh to that of the pentatonic scales, this sense of the divine gradually diminished. Even so, in perceiving and emphasizing the fifth, a feeling of liberating the divine from the physical lingered on. But whereas with the seventh man felt himself completely removed into the spiritual world, with the fifth he reached up to the very limits of his physical body; felt his spiritual nature at the boundary of his skin, so to speak, a sensation foreign to modern ordinary consciousness.

The age which followed the one just described—you know this from the history of music—was that of the third, the major and minor third. Whereas formerly music had been experienced outside man in a kind of ecstasy, now it was brought completely within him. The major and minor third, and with them the major and minor scales, took music right into man. As the age of the fifth passed over into that of the third man began to experience music inwardly, within his bounding skin.

We see a parallel transition: on the one hand, in painting the spatial perspective which penetrates into space; on the other, in music, the scales of the third which penetrate into man's etheric-physical body; which is to say, in both directions a tendency toward naturalistic conception. In spatial perspective we have external naturalism, in the musical experience of the third “internal” naturalism.

To grasp the essential nature of things is to understand man's position in the cosmos. The future development of music will be toward spiritualization, and involve a recognition of the special character of the individual tone. Today we relate the individual tone to harmony or melody in order that, together with other tones, it may reveal the mystery of music. In the future we will no longer recognize the individual tone solely in relation to other tones, which is to say according to its planal dimension, but apprehend it in depth; penetrate into it and discover therein its affinity for hidden neighboring tones. And we will learn to feel the following: If we immerse ourselves in the tone it reveals three, five or more tones; the single tone expands into a melody and harmony leading straight into the world of spirit. Some modern musicians have made beginnings in this experience of the individual tone in its dimension of depth; in modern musicianship there is a longing for comprehension of the tone in its spiritual profundity, and a wish—in this as in the other arts—to pass from the naturalistic to the spiritual element.

Man's special relationship to the world as expressed through the arts becomes clear if we advance from those of the outer world, that is architecture, art of costuming, sculpture and painting, to those of the inner world, that is to music and poetry. I deeply regret the impossibility of carrying out my original intention of having Frau Dr. Steiner illustrate, with declamation and recitation, my discussion of the poetic art. Unfortunately she has not yet recovered from a severe cold. During this Norwegian lecture course my own cold forces me to a rather inartistic croaking, and we did not want to add Frau Dr. Steiner's.

Rising to poetry, we feel ourselves confronted by a great enigma. Poetry originates in phantasy, a thing usually taken as synonymous with the unreal, the non-existent, with which men fool themselves. But what power expresses itself through phantasy?

To understand that power, let us look at childhood. The age of childhood does not yet show the characteristics of phantasy. At best it has dreams. Free creative phantasy does not yet live and manifest in the child. It is not, however, something which, at a certain age in manhood, suddenly appears out of nothingness. Phantasy lies hidden in the child; he is actually full of it. What does it do in him? Whoever can observe the development of man with the unbiased eye of the spirit sees how at a tender age the brain, and indeed the whole of his organism, is still, as compared with man's later shape, quite unformed. In the shaping of his own organism the child is inwardly the most significant sculptor. No mature sculptor is able to create such marvelous cosmic forms as does the child when, between birth and the change of teeth, it plastically elaborates his organism. The child is a superb sculptor whose plastic power works as an inner formative force of growth. The child is also a musical artist, for he tunes his nerve strands in a distinctly musical fashion. To repeat: power of phantasy is power to grow and harmonize the organism.

When the child has reached the time of the change of teeth, around his seventh year, then advances to puberty, he no longer needs such a great amount of plastic-musical power of growth and formation as, once, for the care of the body. Something remains over. The soul is able to withdraw a certain energy for other purposes, and this is the power of phantasy: the natural power of growth metamorphosed into a soul force. If you wish to understand phantasy, study the living force in plant forms, and in the marvelous inner configuratons of the organism as created by the ego; study everything creative in the wide universe, everything molding and fashioning and growing in the subsconscious regions of the cosmos; then you will have a conception of what remains over when man has advanced to a point in the elaborating of his own organism when he no longer needs the full quota of his power of growth and formative force. Part of it now rises up into the soul to become the power of phantasy. The final left-over (I cannot call it sediment, because sediment lies below while this rises upward)—the ultimate left-over is power of intellect. Intellect is the finely sifted-out power of phantasy, the last upward-rising remainder.

People ignore this fact. They see intellect as of greater reality. But phantasy is the first child of the natural formative and growth forces; and because it cannot emerge as long as there is active growing, does not express direct reality. Only when reality has been taken care of does phantasy make its appearance in the soul. In quality and essential nature it is the same as the power of growth. In other words, what promotes growth of an arm in childhood is the same force which works in us later, in soul transformation, as poetic, artistic phantasy. This fact cannot be grasped theoretically; we must grasp it with feeling and will. Only then will we be able to experience the appropriate reverence for phantasy, and under certain circumstances the appropriate humor; in brief, to feel phantasy as a divine, active power in the world.

Coming to expression through man, it was a primary experience for those human beings of ancient times of whom I spoke in the last lecture, when art and knowledge were a unity, when knowledge was acquired through artistic rites rather than the abstractions of laboratory and clinic; when physicians gained their knowledge of man not from the dissecting room but from the Mysteries where the secrets of health and disease, the secrets of the nature of man, were divulged in high ceremonies.

It was sensed that the god who lives and weaves in the plastic and musical formative forces of the growing child continues to live in phantasy. At that time, when people felt the deep inner relationship between religion, art and science, they realized that they had to find their way to the divine, and take it into themselves for poetic creation; otherwise phantasy would be desecrated.

Thus ancient poetic drama never presented common man, for the reason that mankind's ancient dramatic phantasy would have considered it absurd to let ordinary human beings converse and carry out all kinds of gestures on the stage. Such a fact may sound paradoxical today, but the anthroposophical researcher—knowing all the objections of his opponents—must nevertheless state the truth. The Greeks prior to Sophocles and Aeschylus would have asked: Why present something on the stage which exists, anyhow, in life? We need only to walk on the street or enter a room to see human beings conversing and gesturing. This we see everywhere. Why present it on a stage? To do so would have seemed foolish.

Actors were to represent the god in man, and above all the god who, rising out of terrestrial depths, gave man his will power. With a certain justification our predecessors, the ancient Greeks, experienced this will-endowment as rising up out of the earth. The gods of the depths who, entering man, endow him with will, these Dionysiac gods were to be given stage presentation. Man was, so to speak, the vessel of the Dionysiac godhead. Actors in the Mysteries were human beings who received into themselves a god. It was he who filled them with enthusiasm.

On the other hand, man who rose to the goddess of the heights (male gods were recognized as below, female gods in the heights), man who rose in order that the divine could sink into him became an epic poet who wished not to speak himself but to let the godhead speak through him. He offered himself as bearer to the goddess of the heights that she, through him, might look upon earth events, upon the deeds of Achilles, Agamemnon, Odysseus and Ajax. Ancient epic poets did not care to express the opinions of such heroes; opinions to be heard every day in the market place. It was what the goddess had to say about the earthly-human element when people surrendered to her influence that was worth expression in epic poetry. “Sing, oh goddess, the wrath of Achilles, son of Peleus”: thus did Homer begin the Iliad. “Sing, oh goddess, of that ingenious hero,” begins the Odyssey. This is no phrase; it is a deeply inward confusion of a true epic poet who lets the goddess speak through him instead of speaking himself, who receives the divine into his phantasy, that child of the cosmic forces of growth, so that the divine may speak about world events.

After the times had become more and more materialistic, Klopstock, who still had real artistic feeling, wrote his Messiade. Inasmuch as man no longer looked up to the gods, he did not dare to say: Sing, oh goddess, the redemption of sinful man as fulfilled here on earth by the Messiah. He no longer dared to do this in the eighteenth century, but cried instead: “Sing, oh immortal soul, of sinful man's redemption.” In other words, he still possessed something which was lifted above the human level. His words reveal a certain bashfulness about what was fully valid in ancient times: “Sing, oh goddess, the wrath of Achilles, son of Peleus.”

Thus the dramatist felt as if the god of the depths had risen, and that he himself was to be that god's vessel; the epic poet as if the Muse, the goddess, had descended into him in order to judge earthly conditions. The ancient Greek actor avoided presentation of the individual human element. That is why he wore high thick-soled shoes, cothurni, and used a simple musical instrument through which his voice resounded. He desired to lift the dramatic action above the individual-personal.

I do not speak against naturalism. For a certain age it was right and inevitable. For when Shakespeare conceived his dramatic characters in their supreme perfection, man had arrived at presenting, humanly, the human element. Quite a different urge and artistic feeling held sway at that period. But the time has come when, in poetic art also, we must find our way back to the spiritual, to presenting dramatic figures in whom man himself, as a spiritual as well as bodily being, can move within the all-permeating spiritual events of the world.

I have made a first weak attempt in my Mystery dramas. There human beings converse not as people do in the market place or on the street, but as they do when higher spiritual impulses play between them, and their instincts, desires and passion are crossed by paths of destiny, of karma, active through millennia in repeated lives.

It is imperative to turn to the spiritual in all spheres. We must make good use of what naturalism has brought us; must not lose what we have acquired by having for centuries now held up, as an ideal of art, the imitation of nature. Those who deride materialism are bad artists, bad scientists. Materialism had to happen. We must not look down mockingly on earthly man and the material world. We must have the will to penetrate into this material world spiritually; nor despise the gifts of scientific materialism and naturalistic art; must—though not by developing dry symbolism or allegory—find our way back to the spiritual. Symbolism and allegory are inartistic. The starting point for a new life of art can come only by direct stimulation from the source whence spring all anthroposophical ideas. We must become artists, not symbolists or allegorists, by rising, through spiritual knowledge, more and more into the spiritual world.

It can be attained quite specially if, in the art of recitation and declamation, we transcend naturalism. In this connection we should remember how genuine artists like Schiller and Goethe formed their poems. In Schiller's soul there lived an indefinite melody, and in Goethe's an indefinite picture, a form, before ever they put down the words of their poems. Often, today, the chief emphasis in recitation and declamation is placed on prose content. But that is only a makeshift. The prose content of a poem, what lies in the words as such, is of little importance; what is important is the way the poet shapes and forms it. Ninety-nine percent of those who write verse are not artists. In a poem everything depends on the way the poet uses the musical element, rhythm, melody, the theme, the imaginative element, the evocation of sounds. Single words give the prose content. The crux is how we treat that prose content; whether, for instance, we choose a fast or slow rhythm. We express joyful anticipation by a fast rhythm. If we say: The hero was full of joyful anticipation, we have prose even if it occurs in a poem. It is essential, in such an instance, to choose a rapidly moving rhythm. When I say: The woman was deeply sad, I have prose, even in a poem. But when I choose a rhythm which flows in soft slow waves, I express sorrow. To repeat, everything depends on form, on rhythm. When I say, The hero struck a heavy blow, it is prose. But if the poet speaks in fuller, not ordinary tones, if he offers a fuller u-tone, a fuller o-tone, instead of a's and e's, he expresses his intention in the very formation of speech.

In declamation and recitation one has to learn to shape language, to foster the elements of melody, rhythm, beat, not prose content. One has also to gauge the effect of a dull sound upon a preceding light sound, and a light sound upon the following dark one, thus expressing a soul experience in the treatment of the speech sounds. Words are the medium of recitation and declamation: a little-understood art which we have striven to develop. Frau Dr. Steiner has given years to it. When we return to artistic feeling on a higher level we return to speech formation as contrasted with the modern emphasis on prose content. Nothing derogatory shall be said against prose content. Having achieved it through the naturalism which made us human, we must keep it. At the same time we must again become imbued with soul and spirit. Word-content can never express soul and spirit. The poet is justified in saying: “If the soul speaks, alas, it is no longer the soul that speaks.” For prose is not the soul's language. It expresses itself in beat, rhythm, melodious theme, image, and the formation of speech sounds. The soul is present as long as the poem expresses rising and falling inner movements.

I make a distinction between declamation and recitation: two separate arts. Declamation has its home in the north; and is effective primarily through the weight of its syllables: chief stress, secondary stress. In contrast, the reciting artist has always lived in the south. In recitation man takes into account not the weight but the measure of the syllables: long syllable, short syllable. Greek reciters, presenting their texts concisely, experienced the hexameter and pentameter as mirrors of the relationship between breathing and blood circulation. There are approximately eighteen breaths and seventy-two pulse-beats per minute. Breath and pulse-beat chime together. The hexameter has three long syllables, the fourth is the caesura. One breath measures four pulse beats. This one-to-four relation appearing in the measure and scanning of the hexameter brings to expression the innermost nature of man, the secret of the relation of breath and blood circulation.

This reality cannot be perceived with our intellect; it is an instinctive, intuitive-artistic experience. And beautifully illustrated by the two versions of Goethe's Iphigenie when spoken one after the other. We have done that often and would have done so today if Frau Dr. Steiner were not indisposed. Before he went to Italy, Goethe wrote his Iphigenie as Nordic artist (to use Schiller's later word for him), in a form which can be presented only through the art of declamation, chief stress, secondary stress, when the life of the blood preponderates. In Italy he rewrote this work. It is not always noticed, but a fine artistic feeling can clearly distinguish the German from the Roman Iphigenie. Because Goethe introduced the recitative element into his Northern declamatory Iphigenie, this Italian, this Roman Iphigenie asks for an altered reading. If one reads both versions, one after the other, the marvelous difference between declamation and recitation becomes strikingly clear. Recitation was at home in Greece where breath measured the faster blood circulation. Declamation was at home in the North where man lived in his inmost nature. Blood is a quite special fluid because it contains the inmost human element. In it lives the human character. That is why the Northern poetic artist became a declamatory artist.

As long as Goethe knew only the North he was a declamatory artist and wrote the declamatory German Iphigenie; but transformed it when he had been softened to meter and measure through seeing the Italian Renaissance art which he felt to be Greek. I do not wish to spin theories, I wish to describe feelings which anthroposophists can kindle for the world of art. Only so shall we develop a true artistic feeling for everything.

One more point. How do we behave on a stage today? Standing in the background we ponder how we would walk down a street or through a drawing-room, then behave that way on the stage. It is all right if we introduce this personal element, but it does lead us away from real style in stage direction, which always means taking hold of the spirit. On the stage, with the audience sitting in front, we cannot behave naturalistically. Art appreciation is largely immersed in the unconsciousness of the instincts. It is one thing if with my left eye I see somebody walk by, passing, from his point of view, from right to left, while, from mine, from left to right. It is quite another thing if this happens in the opposite direction. Each time I have a different sensation; something different is imparted. We must relearn the spiritual significance of directions, what it means when an actor walks from left to right, or from right to left, from back to front, or vice versa; must feel the impossibility of standing in the foreground when about to start a long speech. The actor should say the first words far back, then gradually advance, making a gesture toward the audience in front and addressing both the left and right. Every movement can be spiritually apprehended out of the general picture, and not merely as a naturalistic imitation of actions on the street or in the drawing-room. Unfortunately people no longer wish to make an artistic study of all this; they have become lazy. Materialism permits indolence. I have wondered why people who demand full naturalism—there are such—do not adopt a stage with four walls. No room has three. But with a four-wall set how many tickets would be sold?

Through such paradoxes we can call attention to the great desideratum: true art in contrast to mere imitation. Now that naturalism has followed the grand road from naturalistic stage productions to the films (neither philistine nor pedant in this regard, I know how to value something for which I do not care too much) we must find the way back to presentation of the spiritual, the genuine, the real; must refind the divine-human element in art by refinding the divine-spiritual.

Anthroposophy would take the path to the spirit in the plastic arts also. That was our intention in building the Goetheanum at Dornach, this work of art wrested from us. And we must do it in the new art of eurythmy. And in recitation and declamation. Today people do breathing exercises and manipulate their speech organism. But the right method is to bring order into the speech organism by listening to one's own rhythmically spoken sentence, which is to say, through exercises in breathing-while-speaking. These things need reorientation. This cannot originate in theory, proclamations and propaganda; only in spiritual-practical insight into the facts of life, both material and spiritual.

Art, always a daughter of the divine, has become estranged from her parent. If it finds its way back to its origins and is again accepted by the divine, then it will become what it should within civilization, within world-wide culture: a boon for mankind.

I have given only sketchy indications of what Anthroposophy wishes to do for art, but they should make clear an immense desire to unfold the right element in every sphere. The need is not for theory—art is not theory. The need is for living, fully living, in the artistic quality while striving for understanding. Such an orientation leads beyond discussion to genuine appreciation and creation.

If art is to be fructified by a world-conception, this is the crux of the matter. Art has always taken its rise from a world-conception, from inner world-experience. If people say: Well, we couldn't understand the art forms of Dornach, we must reply: Can those who have never heard of Christianity understand Raphael's Sistine Madonna?

Anthroposophy would like to lead human culture over into honest spiritual world-experience.

Zweiter Vortrag

Vorgestern bemühte ich mich zu zeigen, wie anthroposophische Erkenntnis, die zu gleicher Zeit inneres Leben der Seele ist, nicht von der Kunst, dem künstlerischen Auffassen und dem künstlerischen Erschaffen wegführt, sondern wie derjenige, der in voller Lebendigkeit das anthroposophische Leben ergreift, in der Tat auch in sich den Quell des künstlerischen Auffassens und Schaffens eröffnet. Ich versuchte, für die verschiedenen Gebiete des Künstlerischen einiges anzudeuten, das darauf hinausging, das Leben in den verschiedenen Reichen der Kunst herauszulösen aus den Mitteln, deren sich die Kunst bedient.

Neben dem Architektonischen, dem - wenn ich wiederum das paradoxe Wort gebrauchen darf - Bekleidungskünstlerischen und dem Plastischen habe ich für das Malerische versucht, das wirkliche Erleben der Farbe zu zeigen, und ich habe mich bemüht zu zeigen, wie die Farbe tatsächlich nicht bloß etwas ist, was gewissermaßen an der Oberfläche der Dinge und Wesenheiten hinzieht, sondern was aus dem Inneren, aus dem wirklich Wesenhaften der Welt heraus leuchtet, dieses Wesen offenbart. Und da kam ich darauf zu zeigen, wie das Grün das wirkliche Bild des Lebens ist, so daß die Pflanzenwelt ihr eigenes Leben offenbart in dem Grün. Das Grün bezeichnete ich als herrührend von den mineralischen, also den toten Einschlüssen, den toten stofflichen Bestandteilen des Lebendigen. Das Lebendige zeigt sich uns in der Pflanze durch das Grün in einem toten Bilde. Das ist gerade das Reizvolle, daß sich das Lebendige in dem toten Bilde zeigt. Wir brauchen nur daran zu denken, wie uns die menschliche Gestalt in dem toten Bilde der Plastik erscheint, und wie das Reizvolle gerade darinnen besteht, daß im Plastischen ein totes Bild des Lebendigen erscheinen kann, daß in toten, starren Formen das Leben zum Ausdrucke gebracht werden kann. $o ist es auch im Farbigen mit dem Grün. Das Reizvolle des Naturgrüns besteht eben darinnen, daß das Grün, ohne selbst den Anspruch an das Leben zu machen, als totes Bild des Lebens erscheint.

Ich wiederhole das aus dem letzten Vortrage, um zu zeigen, wie sich in der Tat der Weltenlauf wiederholt und dann in sich selbst zurückkehrt, indem er farbig seine verschiedenen Elemente, das Lebendige, das Seelische, das Geistige zeigt. Und ich sagte schon das letzte Mal, ich wolle Ihnen heute diesen in sich selbst geschlossenen Kreis des Kosmischen in der Farbenwelt aufzeichnen. Wir können also sagen: Das Grün erscheint als das tote Bild des Lebens. Im Grün verbirgt sich das Leben. - Wenn wir dagegen dasjenige Farbige anschauen, welches die Inkarnatfarbe des Menschen ist, die am ähnlichsten der Farbe der frischen Pfirsichblüte im Frühling ist, so bekommen wir in diesem Farbigen das lebendige Bild des Seelischen. Ich kann mich natürlich nur der Farben bedienen - annähernd -, wie sie hier vorhanden sind. Wir bekommen also in der Farbe des Inkarnats das lebendige Bild des Seelischen. In dem Weiß, dem wir uns künstlerisch hingeben, haben wir, wie ich vorgestern sagte, das seelische Bild des Geistes, der sich als solcher verbirgt. Und in dem Schwarz, wenn ich es künstlerisch erfasse, habe ich dann das geistige Bild des Toten. Der Kreis ist in sich geschlossen.

Ich habe die vier Farben Grün, Inkarnatfarbe, Weiß und Schwarz in ihrem künstlerischen Sich-Offenbaren erfaßt, und es zeigt sich darin das in sich geschlossene Leben des Kosmos innerhalb der Welt des Farbigen. Wenn wir gerade diese Farben künstlerisch ins Auge fassen, die hier gewissermaßen zu einem geschlossenen Kreis sich formen, dann können wir aus unserer Empfindung gewahr werden, wie wir das Bedürfnis haben, diese Farben eigentlich immer im Bilde zu bekommen, im geschlossenen Bilde.

Natürlich muß ich auch immer, indem ich Künstlerisches behandle, nicht auf den abstrakten Verstand reflektieren, sondern auf die künstlerische Empfindung. Künstlerisches muß man künstlerisch erkennen. Daher kann ich nicht durch irgendeinen Begriffsbeweis Sie hier darauf aufmerksam machen, wie man bei Grün, Pfirsichblüt, Weiß und Schwarz das Bedürfnis hat, das geschlossene Bild zu haben. Man will eine Kontur haben und innerhalb der Kontur das geschlossene Bild. Es ist in diesen vier Farben immer etwas von Schatten enthalten. Das Weiß ist gewissermaßen der hellste Schatten, denn es ist das Weiß abgeschattetes Licht. Das Schwarz ist der dunkelste Schatten. Grün und Pfirsichblüt sind Bilder, das heißt in sich gesättigte Flächen, was der Fläche etwas Schattenhaftes gibt. So haben wir in diesen vier Farben Bildfarben oder Schattenfarben. Und wir wollen diese Farben als Bildfarben und Schattenfarben empfinden.

Ganz anders wird das, wenn wir zu anderen Farben mit unseren Empfindungen übergehen. Diese anderen Farben sind, wenn ich drei Nuancen von ihnen nehme, Rot, Gelb und Blau. Bei diesen Farben, Rot, Gelb, Blau, haben wir nicht das Bedürfnis, wenn wir auf unser unbefangenes künstlerisches Empfinden zurückgehen, sie in geschlossenen Konturen zu haben, sondern wir haben das Bedürfnis, daß uns die Fläche erglänzt in diesen Farben, daß uns der Glanz des Roten von der Fläche entgegenleuchtet, oder daß uns das Matte des Blaus von der Fläche aus beruhigend entgegenwirkt, oder daß uns das Leuchtende des Gelben von der Fläche entgegenglänzt. Und so kann man die vier Farben Inkarnat, Grün, Schwarz, Weiß die Bildfarben oder Schattenfarben nennen; dagegen Blau, Gelb, Rot die Glanzfarben, die aus dem Bilde des Schattenhaften erglänzen. Und wir kommen wiederum, wenn wir mit unserer Empfindung verfolgen, wie die Welt in den drei Farben Rot, Gelb, Blau glänzend wird, dazu, uns zu sagen: In dem Aufleuchten des Roten wollen wir vorzugsweise das Lebendige schauen. Das Lebendige will sich uns offenbaren, wenn es uns rot, aktiv rot entgegenkommt, so daß wir das Rot nennen können den Glanz des Lebendigen. Will der Geist nicht bloß in seiner abstrakten Gleichheit als Weißes sich uns offenbaren, sondern zu uns innerlich intensiv sprechen, so will er — das heißt unsere Seele will das empfangen - gelb glänzen. Gelb ist der Glanz des Geistes. Will die Seele so recht innerlich sein und will dies zur künstlerischen Offenbarung in der Farbe kommen, dann will die Seele sich hinwegheben von den äußerlichen Erscheinungen, will in sich beschlossen sein. Das gibt den milden Schein des Blaus. Und so ist der milde Schein des Blaus der Glanz des Seelischen. Wir kommen dazu, die drei Glanzfarben so zu empfinden, daß wir das Rot als den Glanz des Lebendigen, das Blau als den Glanz des Seelischen und das Gelb als den Glanz des Geistigen empfinden.

Sehen Sie, dann leben wir in der Farbe, dann verstehen wir mit unserer Empfindung, mit unserem Gefühl die Farbe, wenn wir überall die Empfindung haben, wie sich eine Welt aus den Bildfarben Pfirsichblüt, Grün, Schwarz, Weiß zusammensetzt und aus den Glanzfarben, die wiederum den Bildfarben den entsprechenden Schein der Offenbarung geben: Rot, Gelb, Blau. Man wird, wenn man sich in dieser Weise in den Glanz und in die Bildhaftigkeit der Welt des Farbigen hineinlebt, dadurch innerlich vom Seelischen aus zum Maler, denn man lernt leben mit der Farbe. Man lernt zum Beispiel empfinden, was die einzelne Farbe uns selber sagen will. Blau ist der Glanz des Seelischen. Wenn wir eine Fläche blau bestreichen, so fühlen wir eigentlich uns nur dann befriedigt, wenn wir das Blau so auftragen, daß wir es am Rande stark auftragen und nach der Mitte zu schwächer werden lassen.

Tragen wir dagegen das Gelb auf und wollen uns von der Farbe selber etwas sagen lassen, dann wollen wir in der Mitte das gesättigte Gelb und am Rande das ungesättigte helle Gelb haben. Das fordert die Farbe selber. Dadurch wird, was in Farben lebt, allmählich sprechend. Wir kommen dazu, aus den Farben heraus die Form zu gebären, das heißt aus der Farbenwelt heraus empfindend zu malen.

Es wird uns nicht einfallen, wenn wir in dieser Weise die Welt als Farbe erleben, wenn wir zum Beispiel eine Gestalt als leuchtende weiße Gestalt, also im Geist lebende Gestalt hingehen lassen wollen im Bilde, daß wir diese in einer anderen Farbe als in einer gelb und nach außen hellgelb verlaufenden Farbe zeigen. Es wird uns nicht einfallen, die empfindende Seele auf einem Bilde anders zu malen, wenn wir das auch vielleicht nur in der Gewandung ausdrücken können, als dadurch, daß wir das Blau verwenden, das nach innen zu sanft blau verläuft. Genießen Sie von diesem Gesichtspunkt aus noch die Maler der Renaissance, Raffael, Michelangelo, selbst noch Lionardo, so werden Sie überall finden, da lebte man noch in dieser Weise künstlerisch wirklich in der Farbe.

Vor allen Dingen war da eines noch vorhanden, vorhanden voll in der für unsere heutige Zeit fast ganz verglommenen Malerei, aber auch noch im Nachklang in der Renaissancemalerei: die innere Perspektive des Bildes, die in der Farbe lebt. Wer Rot zum Beispiel, den Glanz des Roten wirklich empfindet, der wird immer erleben, wie das Rot aus dem Bilde herauskommt, wie das Rot dasjenige, was es abbildet, im Bilde uns nahe bringt, während das Blau das, was es abbildet, in die Ferne trägt. Und wir malen auf der Fläche in Rot-Blau, indem wir zu gleicher Zeit perspektivisch malen: das Rote nahe, das Blaue ferne. Wir malen Farbenperspektive, innerliche Perspektive. Das ist diejenige Perspektive, die noch im Seelisch-Geistigen lebte.

Im materialistischen Zeitalter kam erst — das berücksichtigt man so wenig — die Raumperspektive auf, die Perspektive, die nun mit Raumgrößen rechnet, das Ferne nicht in Blau taucht, sondern klein macht, das Nahe nicht in Rot erglänzen läßt, sondern groß macht. Diese Perspektive ist erst eine Beigabe des materialistischen Zeitalters, das im Räumlich-Materiellen lebte und auch im RäumlichMateriellen malen wollte.

Wir sind heute wiederum in der Zeit, wo wir zurückfinden müssen zum Naturgemäßen des Malens, denn zum Material des Malers gehört auch die Fläche. Zuerst hat man die Fläche. Und daß man auf der Fläche arbeitet, das zählt man zum Material des Malers. Der Künstler muß aber vor allen Dingen sein Materialgefühl haben. Er muß zum Beispiel ein so starkes Materialgefühl haben, daß er weiß, will er ein Plastisches aus dem Holze heraus arbeiten, dann muß er zum Beispiel die Augen des Menschen ausgraben aus dem Holz. Er muß dasjenige, was konkav ist, vor allen Dingen ins künstlerische Auge fassen und aushöhlen. Der in Holz arbeitende Bildhauer höhlt das Holz aus. Der in Marmor oder in einem anderen Material, in einem harten Material, arbeitende Bildhauer berücksichtigt nicht, wie das Auge hineingeht. Er höhlt nicht aus, sondern er berücksichtigt, wie die Stirne herausgeht aus dem Auge. Er trägt auf. Er berücksichtigt das Konvexe. Der in Marmor Arbeitende, schon wenn er in Plastilin oder einem anderen Material, in Tonmaterial, sich vorarbeitet, muß sich in sein Material hineinversetzen. Der für den Marmor Arbeitende trägt auf. Der für das Holz Arbeitende höhlt aus. Man muß mit seinem Materiale leben können. Das Material muß für einen, wenn man Künstler ist, eine lebendige Sprache führen,

So muß es durchaus auch sein mit dem Farbigen. Und es muß vor allen Dingen so sein mit der Tatsache, daß man als Maler die Fläche zum Material hat. Man empfindet die Fläche nur, wenn man die dritte Raumdimension ausgelöscht hat. Man hat sie ausgelöscht, wenn man das Qualitative auf der Fläche als Ausdruck der dritten Dimension empfindet, wenn man das Blau als das Zurückgehende, das Rot als das Hervortretende empfindet, wenn also in die Farbe hinein sich lebt die dritte Dimension. Dann hebt man das Materielle wirklich auf, während man in der Raumperspektive das Materielle nur nachahmt. Ich rede selbstverständlich nicht gegen die Raumperspektive. Sie war dem Zeitalter, das etwa in der Mitte des 15. Jahrhunderts herauftauchte, selbstverständlich und natürlich und hat etwas Gewaltiges zu dem alten Künstlerischen im Malen hinzugebracht. Aber das Wesentliche ist doch, daß, nachdem wir eine Zeitlang künstlerisch durch den Materialismus durchgegangen sind, der sich auch in der Raumperspektive ausdrückt, wir wiederum zu einer mehr spirituellen Auffassung auch des Malerischen zurückzukehren vermögen, so daß wir wiederum zur Farbenperspektive zurückkommen.

Sehen Sie, man kann nicht theoretisieren, wenn man über Kunst spricht. Man muß immer im Mittel der Kunst bleiben. Und dasjenige, was einem zur Verfügung stehen kann, wenn man über Kunst spricht, muß die Empfindung sein. Wenn man über Mathematik spricht, oder über Mechanik oder Physik, kann man nicht aus der Empfindung heraus sprechen, sondern da muß man aus dem Verstande heraus sprechen, aber man kann gar nicht aus dem Verstande heraus irgendwie die Kunst betrachten. Zwar haben dies die Ästhetiker des 19. Jahrhunderts getan. Da hat mir einmal ein Künstler in München erzählt, er und seine Kollegen seien auch einmal, als sie jung waren, um es zu probieren, in das Kolleg eines Ästhetikers gegangen, sogar eines sehr berühmten Ästhetikers in der damaligen Zeit, um zu sehen, ob sie etwas von dem theoretisierenden Ästhetiker lernen können. Aber sie sind alle nicht ein zweites Mal hingegangen und haben nur den Ausdruck «ästhetischer Wonnegrunzer» dafür übrig behalten. Sie als Maler haben ihn den «ästhetischen Wonnegrunzer» genannt. Vielleicht versteht man doch das künstlerisch-ironisch Absprechende über die Theoretik in diesem Ausdruck.

Nun, dasselbe, was man so im lebendigen Leben und Weben der Farben darstellen kann, kann man auch aus dem Weben und Leben in Tönen darstellen. Nur kommt man gerade da, wie ich schon vorgestern andeutete, mit der Ionwelt, mit dem musikalischen Elemente in das Innere des Menschen. Indem der Mensch Plastiker wird, Maler wird, geht er hinaus in den Raum, auch wenn er als Maler den Raum zum zweidimensionalen aufhebt, stellt er in ihm doch dasjenige dar, was sich im Raume farbig ätherisch darlebt und offenbart. Mit dem Musikalischen kommen wir in das unmittelbar Innere des Menschen, und es ist außerordentlich bedeutsam, wenn wir gerade das Musikalische innerhalb des Entwickelungsganges der Menschheit ins Auge fassen.

Diejenigen der verehrten Anwesenden und Freunde, welche öfter meine Vorträge gehört haben oder die anthroposophische Literatur kennen, wissen, daß wir im Entwickelungsgang der Menschheit bis in diejenigen Zeiten zurückgehen, die wir die atlantische Epoche der Menschheitsentwickelung nennen, wo noch ein ganz anderes Menschengeschlecht auf Erden war, das mit einem ursprünglichen instinktiven Hellsehen begabt war, das im wachen Träumen das Geistige hinter dem Sinnlichen sah. In diesem Zeitalter, wo die Menschen noch ein instinktives Hellsehen hatten, instinktiv das Geistige hinter dem Sinnlichen sahen, ging parallel diesem Schauen auch ein andersartiges Empfinden des Musikalischen. Beim Erfassen des Musikalischen fühlte der Mensch instinktiv in uralten Zeiten sich heraus versetzt aus seinem Leibe. Daher gefielen diesen Leuten in uralten Zeitaltern vorzugsweise, so paradox das für den heutigen Menschen klingt, die Septimenakkorde. Sie musizierten und sangen in Septimen, etwas, was heute nicht mehr in vollem Maße als musikalisch empfunden wird. Aber die Leute fühlten sich auch im Genießen der Septimenakkorde ganz aus dem Menschlichen ins Göttliche herausversetzt.

Das schwächte sich dann im Laufe der Zeit ab, indem der Übergang gefunden wurde von dem Septimenerleben zu den Quintenskalen. Im Wahrnehmen der Quinte, im Betonen des Quintenhaften im Musikalischen war noch immer eine Empfindung davon, daß der Mensch eigentlich mit dem Musikalischen das Göttliche in ihm loslöst vom Physischen. Aber der Mensch kam, während er bei den Septimen herauskam, völlig sich entrückt fühlte zum Geistigen, mit seinem Empfinden in den Quinten gerade bis an die Grenze seines Physischen. Er empfand sein Geistiges an der Grenze seiner Haut, eine Empfindung, die der Mensch heute gar nicht mehr mit dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein verwirklichen kann.

Dann trat, wie Sie aus der Geschichte der Musik wissen werden, die Terzzeit ein, die Zeit der großen und kleinen Terzen. Diese Terzzeit bedeutet, daß das Musikalische von dem Erlebtwerden außer dem Menschen, als eine Art von menschlicher Entrücktheit, in den Menschen ganz hineingenommen wurde. Die Terz, sowohl die große Terz wie die kleine Terz, und die dadurch bedingte Dur- und Molltonart, nehmen das Musikalische in den Menschen herein. Daher tritt in der neueren Zeit, als die Quintenzeit in die Terzzeit übergeht, das Phänomen ein, daß der Mensch das Musikalische auch ganz innerlich erlebt, gewissermaßen innerhalb seiner Haut erlebt.

Wir sehen den parallelen Übergang, auf der einen Seite die Raumperspektive, welche hinausdringen will malerisch in den Raum, auf der anderen Seite die Terzentonart, die hineindringt in den ätherisch-physischen Leib des Menschen, also nach beiden Seiten hin zum naturalistischen Auffassen. Auf der einen Seite in der Raumperspektive äußerer Naturalismus, auf der anderen Seite im musikalischen Erfassen der Terz innerer menschlicher Naturalismus. Überall, wo wir das wirkliche Wesen der Dinge erfassen, dringen wir durchaus auch zu einer Erkenntnis der ganzen Stellung des Menschen zum Kosmos vor. Und die nächste Entwickelung wird auch im Musikalischen eine Vergeistigung, eine Verspiritualisierung sein. Sie wird darinnen bestehen, daß wir den einzelnen Ton in seiner besonderen Eigenart kennenlernen werden. Den einzelnen Ton, den wir heute in die Harmonie oder in die Melodie hineinfügen, damit er mit dem anderen Ton zusammen das Geheimnis des Musikalischen enthülle, werden wir nicht mehr bloß in seinem Verhältnis zu anderen Tönen erkennen, also gewissermaßen nach der Ebenendimension erfassen, sondern wir werden ihn in seiner Tiefendimension erfassen, wir werden in den einzelnen Ton eindringen, dann wird im einzelnen Ton immer ein Ansatz zu verborgenen Nachbartönen erscheinen. Man wird fühlen lernen: Vertieft man sich, versenkt man sich in den Ton, dann offenbart der Ton drei oder fünf oder noch mehr Töne, und man dringt mit dem Ton, in den man sich vertieft, indem der. Ton selbst zur Melodie und zur Harmonie sich ausweitet, ins Spirituelle ein. — Bei einzelnen Musikern der Gegenwart sind Ansätze gemacht zu diesem Eindringen in die Tiefendimensionen des Tones, allein es ist heute im musikalischen Empfinden der Menschen gerade erst, man möchte sagen die Sehnsucht vorhanden, den Ton in seiner geistigen Tiefe zu erfassen und dadurch auch auf diesem Gebiete immer mehr und mehr aus dem Naturalistischen in das Spirituelle der Kunst hineinzudringen.

Ganz besonders merkt man diese Tatsache, daß sich im Künstlerischen ein besonderes Verhältnis des Menschen zur Welt äußert, wenn man vordringt von den Künsten der Außenwelt, Architektur, Bekleidungskunst, Plastik, Malerei, durch die Künste des mehr Innerlichen, die musikalischen Künste, zu der dichterischen Kunst. Und da, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, muß ich leider bedauern, die ursprüngliche Absicht nicht ausführen zu können, daß dasjenige, was ich als Rest dieser künstlerischen Betrachtung über Dichterisches zu sagen habe, illustriert werden könnte durch die Deklamation und Rezitation von Frau Dr. Steiner. Sie ist leider noch immer nicht von einer wochenlang andauernden Erkältung so weit hergestellt, daß sie es heute wagen kann, rezitatorisch und deklamatorisch vor Ihnen aufzutreten. Es muß also diese Illustration desjenigen, was ich Ihnen zu sagen habe, zu meinem tiefen Leidwesen unterbleiben. Allein, wir wagten eben doch nicht, zu dem etwas unkünstlerischen Gekrächze, zu welchem ich während dieses norwegischen Kursus durch meine eigene Erkältung genötigt bin, auch die noch nicht ganz hergestellte Stimme von Frau Dr. Steiner hinzuzufügen, denn im Künstlerischen kann man eben weniger wagen, das Reden ins Krächzen zu verwandeln, als im gewöhnlichen Vortrage.

Wenn wir heraufdringen in das Dichterische, fühlen wir so recht uns vor eine große Frage gestellt. Das Dichterische entspringt aus der Phantasie. Die Phantasie stellt für die Menschen gewöhnlich nur das Unwirkliche vor, das, was man sich einbildet, was nicht da ist. Aber welche Kraft äußert sich denn eigentlich in der Phantasie?

Schauen wir, um die Kraft der Phantasie zu verstehen, dazu einmal das kindliche Alter an. Das kindliche Alter hat noch nicht Phantasie. Es hat höchstens Träume. Die frei schöpferische Phantasie lebt noch nicht im Kinde. Sie lebt nicht offenbar. Aber sie ist nicht etwas, was plötzlich aus den Menschen in einem bestimmten Lebensalter aus dem Nichts hervorkommt. Die Phantasie ist doch, nämlich verborgen da im Kinde, obwohl sie sich nicht offenbart, und das Kind ist eigentlich voll von Phantasie. Aber was tut denn beim Kinde die Phantasie? Ja, dem, der mit unbefangenem Geistesauge die Menschenentwickelung betrachten kann, zeigt sich, wie im zarten Kindesalter noch unplastisch im Verhältnis zu der späteren Gestalt namentlich das Gehirn, aber auch der übrige Organismus ausgebildet ist. Das Kind ist innerlich der unglaublichste, bedeutende Plastiker in der Ausgestaltung seines eigenen Organismus. Kein Plastiker ist imstande, so wunderbar aus dem Kosmos heraus Weltenformen zu schaffen, als das Kind sie schafft, wenn es in der Zeit zwischen der Geburt und dem Zahnwechsel plastisch das Gehirn ausgestaltet und den übrigen Organismus. Das Kind ist ein wunderbarer Plastiker, nur arbeitet die plastische Kraft in den Organen als innerliche Wachstums- und Bildekraft. Und das Kind ist auch ein musikalischer Künstler, denn es stimmt seine Nervenstränge in musikalischer Weise. Wiederum ist die Phantasiekraft Wachstumskraft, Kraft der Abstimmung des Organismus selber.

Sehen Sie, wenn wir nach und nach zu dem Zeitalter aufrücken, in dem der charakterisierte Zahnwechsel geschieht, um das siebente Jahr herum, und nachher aufrücken zu dem Zeitalter der Geschlechtsreife, da brauchen wir nicht mehr so viel plastisch-musikalische Kraft als Wachstumskraft, als Bildekraft in uns wie früher. Da bleibt etwas übrig. Da kann die Seele gewissermaßen etwas herausziehen aus der Wachstums- und Bildekraft. Was die Seele dann nach und nach, indem das Kind heranwächst, nicht mehr braucht, um den eigenen Körper als Wachstumskraft zu versorgen, das bleibt übrig als Phantasiekraft. Die Phantasiekraft ist nur die ins Seelische metamorphosierte natürliche Wachstumskraft. Wollen Sie kennenlernen, was die Phantasie ist, studieren Sie zunächst die lebendige Kraft im Formen der Pflanzengebilde, studieren Sie die lebendige Kraft im Formen der wunderbaren Innengebilde des Organismus, die das Ich zustande bringt, studieren Sie alles dasjenige, was im weiten Weltenall gestaltend ist, was in den unterbewußten Regionen des Kosmos gestaltend und bildend und wachsend wirkt, dann haben Sie auch einen Begriff von dem, was dann übrig bleibt, wenn der Mensch so weit in der Bildung seines eigenen Organismus vorgerückt ist, daß er nicht mehr das volle Maß seiner Wachstums- und Bildekraft braucht. Dann rückt ein Teil in die Seele herauf und wird Phantasiekraft. Und erst ganz zuletzt, das Letzte, was übrig bleibt, ich kann nicht sagen der Bodensatz, weil der Bodensatz unten ist, und das, was da übrig bleibt, geht nach oben, ist dann die Verstandeskraft. Das ist die ganz durchgesiebte Phantasiekraft, das Letzte, was übrig bleibt, ich kann nicht sagen der Bodensatz, sondern der Niveausatz, der oben herauskommt: der Verstand.

Der Verstand ist die durchgesiebte Phantasie. Das beachten die Leute nicht, deshalb halten sie den Verstand für ein so viel größeres Wirklichkeitselement, als die Phantasie es ist. Aber die Phantasie ist das erste Kind der natürlichen Wachstums- und Bildekräfte selbst. Daher drückt die Phantasie etwas unmittelbar Wirkliches nicht aus, denn solange die Wachstumskraft im Wirklichen arbeitet, kann sie nicht zur Phantasie werden. Es bleibt erst etwas übrig für die Seele als Phantasie, wenn das Wirkliche versorgt ist. Aber innerlich, der Qualität, der Wesenheit nach ist die Phantasie durchaus dasselbe wie die Wachstumskraft. Dasjenige, was unseren Arm von der Kleinheit größer werden läßt, ist dieselbe Kraft wie dasjenige, was in uns dichterisch in der Phantasie, überhaupt künstlerisch in der Phantasie tätig ist in der seelischen Umgestaltung. Das muß man wiederum nicht theoretisch verstehen, sondern man muß es innerlich gefühls- und willensmäßig verstehen. Dann bekommt man vor dem Walten der Phantasie auch die nötige Ehrfurcht, unter Umständen auch gegenüber diesem Walten der Phantasie den nötigen Humor. Kurz, es wird die Anregung für den Menschen geschaffen, in der Phantasie eine in der Welt waltende göttliche Kraft zu empfinden. Diese in der Welt waltende göttliche Kraft, die sich durch den Menschen ausdrückt, empfanden vor allen Dingen die Menschen in jenen alten Zeiten, auf die ich im vorhergehenden Vortrag hingedeutet habe, wo Kunst und Erkenntnis noch eins waren, wo in den alten Mysterien dasjenige, was man erkennen sollte, noch durch die schön, das heißt künstlerisch gefaßten Kultushandlungen vorgestellt wurde, nicht durch die Abstraktionen des Laboratoriums und der Klinik, wo der Arzt noch nicht in den Anatomiesaal ging, um den Menschen kennenzulernen, sondern wo er in die Mysterien ging und die Geheimnisse des gesunden und kranken menschlichen Lebens in dem Mysterienzeremoniell ihm enthüllt wurden und er auch dadurch innerlich den Einlaß in die menschliche Wesenheit erlangte.

In dieser Zeit fühlte man, der Gott, der in einem webte und lebte, als man vom kleinen Kinde plastisch und musikalisch sich formend und bildend aufwuchs, lebte auch noch in der Phantasie fort. Daher war man sich in alten Zeiten klar, in denen die tiefe innerliche Verwandtschaft zwischen Religion, Kunst und Wissenschaft empfunden worden ist, daß man eigentlich die Phantasie nur dann nicht entheiligt, nicht profaniert, wenn man sich bewußt bleibt, daß man sich zum Göttlichen in irgendeiner Weise hinfinden müsse oder dem Göttlichen Einlaß geben müsse in den Menschen, wenn man dichterisch sich offenbaren will. Wenn in den ältesten Zeiten in dramatischen Gestaltungen niemals der äußere Mensch dargestellt worden ist, so ist es daher — das klingt wiederum paradox für die Menschen der Gegenwart, der anthroposophische Forscher weiß das natürlich, er muß das sagen, trotzdem es paradox klingt, er weiß die Einwände, die gemacht werden können, ebenso wie die Gegner sie wissen, aber es muß doch dieses Paradoxe gesagt werden -, weil die älteste dramatische Phantasie der Menschheit es als absurd empfunden hätte, gewöhnliche Menschen auf die Bühne zu stellen, die allerlei sich sagen, allerlei Gesten gegeneinander machen. Warum soll man denn das tun? - So würde noch ein Grieche der vorsophokleischen [Zeit], namentlich der Zeit vor dem Äschylos sich gesagt haben. Warum denn? Das ist ja im Leben ohnedies vorhanden. Da brauchen wir nur in die Straßen und Zimmer zu gehen, da sehen wir, wie die Menschen miteinander reden, wie die Menschen Gebärden gegeneinander machen. Wozu das? Das haben wir immer vor uns. Warum sollen wir das noch extra auf die Bühne hinstellen? - Närrisch wäre das noch den ältesten Griechen vorgekommen, gewöhnliche Menschen, die man in ihren Handlungen alltäglich sieht, noch extra auf die Bühne hinzustellen. Dasjenige, was man wollte, war, den Gott im Menschen zu ergreifen. Wenn man den Menschen auf die Bühne stellte, da sollte der Mensch den Gott im Menschen darstellen, namentlich den aus den Erdentiefen heraufsteigenden Gott, der den Menschen den Willen gibt. Die Willensbegabung sahen mit einem gewissen Recht unsere alten Vorfahren, noch die alten Griechen, als von dem Irdischen heraufkommend in die menschliche Natur. Die Götter der Tiefe, die in den Menschen hineinsteigen, um ihm den Willen zu geben, die dionysischen Götter wollten die Menschen der alten Zeiten auf der Bühne sehen. Der Mensch war gewissermaßen nur die Umhüllung der dionysischen Gottheit. Es war durchaus der den Gott in sich aufnehmende, der vom Gotte sich begeistern lassende Mensch, der in den ältesten dramatischen Darstellungen des Mysterienwesens auftrat. Der Mensch, der den Gott aufnahm, war derjenige, der als dramatische Person auftrat.

Der Mensch, der sich zum Gott der Höhe erhob, besser gesagt zur Göttin der Höhe, weil man unten die männlichen Gottheiten in der alten Zeit erkannte, in den Höhen die weiblichen Gottheiten — derjenige, der sich zu den Höhen erhob, um das Göttliche zu erreichen, so daß es sich zu ihm herniedersenkte, wurde zum Epiker, der nicht selbst sprechen, sondern die Gottheit in sich spre‚chen lassen wollte. Der Mensch gab sich her, eine Hülle zu sein den Göttinnen der Höhe, damit sie durch ihn auf die Ereignisse der Welt schauen können, auf dasjenige, was Achill und Agamemnon und Odysseus und Ajax getan haben. Was Menschen darüber zu sagen haben, das wollten die alten Epiker nicht zum Ausdrucke bringen. Das hört man täglich auf dem Marktplatz, was Menschen über die Helden zu sagen haben. Was aber die Göttin zu sagen hat, wenn der Mensch sich ihr hingibt, über das Irdisch-Menschliche, das war epische Dichtkunst. «Singe, o Muse, vom Zorn mir des Peleiden Achilleus», so beginnt Homer die Ilias. «Singe, o Muse» — das heißt: o Göttin - «vom Manne, dem vielgereisten Odysseus», so beginnt Homer in der Odyssee. Das ist keine Phrase, das ist tief innerliches Bekenntnis des wahren Epikers, der die Göttin in sich sprechen läßt, der nicht selber sprechen will, der in seine Phantasie, die das Kind der kosmischen Wachstumskräfte ist, das Göttliche aufnimmt, damit das Göttliche in ihm spricht über die Ereignisse der Welt. Als dann.die Zeit immer naturalistischer und materialistischer wurde, aber, ich möchte sagen mit einem gewissen wirklichen künstlerischen Gefühl noch Klopstock seine «Messiade» dichtete, da getraute er sich nicht mehr, weil man nicht mehr so zu den Göttern hinsah wie in alten Zeiten, etwa zu sagen: Singe, o Muse, der sündigen Menschen Erlösung, die der Messias auf Erden in seiner Menschheit vollendet. — Das getraute sich Klopstock im 18. Jahrhundert nicht mehr zu sagen. Und so sagte er: «Sing, unsterbliche Seele, der sündigen Menschen Erlösung.» Er wollte aber auch noch im Anfange etwas über den Menschen Herausgehobenes haben. Das ist noch eine wenn auch schamhafte Empfindung für dasjenige, was in alten Zeiten vollgültig war: «Singe, o Muse, vom Zorn mir des Peleiden Achilleus.»

So fühlte sich der Dramatiker, wie wenn der Gott aus den Tiefen zu ihm heraufgestiegen wäre und er die Hülle des Gottes sein sollte. So fühlte sich der Epiker, wie wenn die Muse, die Göttin, zu ihm heruntergestiegen wäre und über die irdischen Verhältnisse urteilen würde. Daher wollte der Grieche in den alten Zeiten es auch vermeiden, als Schauspieler, als Verkörperer des Dramatischen, das individuell Menschliche unmittelbar hervortreten zu lassen. Er stand auf Erhöhungen seiner Beine, seiner Füße. Er hatte etwas wie eine Art leichten Musikinstrumentes, durch das sein 'Ion erklang. Denn er wollte dasjenige, was dramatisch dargestellt wurde, hinausheben über das individuell persönlich Menschliche. Ich spreche wiederum nicht etwa gegen den Naturalismus, der für ein gewisses Zeitalter selbstverständlich und natürlich war. Denn in der Zeit, als Shakespeare seine dramatischen Gestalten in ihrer übergroßen Vollkommenheit hinstellte, war man dazu gelangt, das Menschliche menschlich erfassen zu wollen, da war durchaus ein anderer Trieb, etwas anderes als künstlerische Empfindung da. Aber jetzt müssen wir wieder den Weg finden auch im Dichterischen zurück ins Spirituelle hinein, müssen wiederum den Weg finden, Gestalten darzustellen, in denen der Mensch selbst, der auch ein geistiges Wesen ist neben dem leiblichen, sich innerhalb der geistigen Ereignisse der Welt, die überall die Welt durchsetzen, zu bewegen vermag.

Ich habe das - ein erster, schwacher Versuch - in meinen Mysteriendramen versucht. Da treten Menschen auf, aber sie sagen sich nicht dasjenige, was gehört werden kann, wenn man auf den Marktplatz oder auf die Straße geht, sie sagen sich dasjenige, was zwischen Mensch und Mensch erlebt wird, wenn die höheren geistigen Impulse zwischen ihnen spielen, wenn das zwischen ihnen spielt, was nicht Instinkte, Triebe, Leidenschaften allein sind, sondern was in den 'Irieben und Leidenschaften als die Wege des Schicksals, die Wege des Karma, wie sie durch Jahrhunderte und Jahrtausende in den wiederholten Menschenleben spielen, hindurchgeht.

So handelt es sich darum, daß wir auf allen Gebieten wiederum zurückkommen zum Spirituellen. Wir müssen das, was uns der Naturalismus gebracht hat, gut verwerten können, wir müssen das, was wir uns angeeignet haben, dadurch daß wir in der Nachahmung des Natürlichen auch einmal durch Jahrhunderte ein Kunstideal gesucht haben, nicht verlieren. Das sind schlechte Künstler, geradeso wie schlechte Wissenschafter, die mit Spott und Hohn auf den Materialismus herabsehen. Der Materialismus mußte da sein. Es kommt nicht darauf an, daß wir die Mundwinkel verziehen über den niederen, bloß irdischen materiellen Menschen, die ganze materielle Welt. Es kommt darauf an, daß wir den Willen besitzen, in diese materielle Welt auch geistig wirklich einzudringen. Also wir müssen nicht dasjenige verachten, was uns wissenschaftlich der Materialismus, was uns künstlerisch der Naturalismus gebracht hat. Aber wir müssen den Weg wiederum zum Spirituellen zurückfinden, nicht indem wir einen trockenen Symbolismus ausbilden oder einen strohernen Allegorismus. Symbolismus wie Allegorismus sind unkünstlerisch. Einzig und allein die unmittelbare Anregung der künstlerischen Empfindung aus dem Quell heraus, aus dem die Ideen der Anthroposophie kommen, kann den Ausgangspunkt für ein neues Künstlerisches liefern. Künstler müssen wir werden, nicht Symboliker und Allegoriker, indem wir gerade durch eine geistige Erkenntnis immer mehr und mehr in die geistigen, in die spirituellen Welten auch aufsteigen. Das kann sich aber ganz besonders entwickeln, wenn wir auch in der Rezitations- und Deklamationskunst hinauskommen aus dem bloßen Naturalismus, wiederum zu einer Art von Geistigkeit kommen. Sehen Sie, da muß immer wieder und wiederum betont werden, daß solche echten Künstler wie zum Beispiel Schiller zuerst eine unbestimmte Melodie in der Seele hatten oder wie Goethe ein unbestimmtes Bild, ein plastisches, bevor sie das Wortwörtliche ausgestalteten. Heute legt man im Rezitieren und Deklamieren oftmals den Hauptwert auf die prosaische Pointierung. Aber daß wir uns der Prosa bedienen müssen, um das dichterische Wort auszudrücken, das ist nur ein Surrogat. Auf den Prosa-Inhalt kommt es bei der Dichtung gar nicht an. Es kommt nicht auf dasjenige an, was in der Dichtung in den Worten liegt, sondern es kommt in der Dichtung darauf an, wie es von dem wirklichen dichterischen Künstler gestaltet wird. Es ist nicht ein Prozent von denen, die dichten, wirklich Künstler, mehr als neunundneunzig Prozent sind gar keine Künstler von den Leuten, die dichten. Es kommt auf dasjenige an, was der Dichter durch das Musikalische erreicht, durch das Rhythmische, durch das Melodiöse, durch das Thematische, durch das Imaginative, durch das Lautgestaltende, nicht durch das Wortwörtliche. Durch das Wortwörtliche geben wir den Prosagehalt. Bei dem Prosagehalt handelt es sich erst darum, wie wir ihn behandeln, ob wir zum Beispiel einen Rhythmus, der schnell geht, wählen. Wenn wir einen schnellgehenden Rhythmus haben und etwas ausdrücken, so können wir freudige Erregung ausdrücken. Für die Dichtung ist es ganz gleichgültig, ob einer sagt: «Der Held war in freudiger Erregung.» — das ist Prosa, auch wenn es in der Dichtung auftritt. Aber das Wesentliche ist in der Dichtung, daß man dann den Rhythmus wählt, der schnell dahingleitet. Wenn ich sage: «Die Frau war tief in der Seele betrübt.» — es ist Prosa, auch wenn es in der Dichtung vorkommt. Wenn ich einen Rhythmus wähle, der in sanften, langsamen Wellen dahinfließt, drücke ich das Betrübtsein aus. Auf die Formgestaltung, auf den Rhythmus kommt es an. Oder wenn ich sage: «Der Held führte einen kräftigen Stoß.» — es ist Prosa. Wenn ich, während ich vorher die gewöhnliche Tonlage gehabt habe, dann den Ton voller nehme, hinaufgehe, wenn der Dichter das schon so veranlagt, daß er einen volleren u-Ion, einen volleren o-Ion nimmt, statt e-Tönen und i-Tönen, dann drückt er in der Sprachgestaltung, in der Sprachbehandlung dasjenige aus, was eigentlich ausgedrückt werden soll. Und auf diese Sprachgestaltung, auf diese Sprachbehandlung kommt es bei der wirklich dichterischen Kunst an.

Beim Deklamieren und Rezitieren kommt es auch darauf an, daß man lernt die Sprache zu gestalten, das Melodiöse, das Rhythmische, das Taktmäßige herauszugestalten, nicht die prosaischen Pointierungen, oder auch daß man lernt, imaginativ die Wirkung des dumpfen Lautes auf den vorhergehenden hellen zu ermessen, des hellen Lautes auf den nachfolgenden dunklen zu ermessen und dadurch das innere Erleben der Seele in der Lautbehandlung zum Ausdrucke zu bringen. Die Worte sind nur die Leiter, an denen das Rezitatorische und Deklamatorische sich eigentlich entwickeln soll. Das ist die Rezitations- und Deklamationskunst, die wir versucht haben auszubilden. Frau Dr. Steiner hat sich jahrelang bemüht, gerade diese Rezitationskunst auszubilden. Sie wird heute noch wenig verstanden. Aber wenn man wiederum zu einem künstlerischen Empfinden auf einer höheren Stufe zurückkehren wird, dann wird man auch auf diesem Gebiete gegenüber dem heutigen prosaischen Pointieren - auf das kein Stein geworfen werden soll, gegen das nichts gesagt ist, das müssen wir beibehalten, wir haben es uns durch den Naturalismus errungen, wir sind dadurch menschlich geworden, aber wir müssen wiederum seelisch und geistig werden, indem wir durch den Inhalt der Worte, wodurch wir niemals Seelisches und Geistiges zum Ausdrucke bringen können — wiederum zu der Sprachbehandlung zurückkommen. Mit Recht sagt der Dichter: Spricht die Seele, so spricht, ach, schon die Seele nicht mehr. - Er meint, wenn die Seelenwelt übergeht, die Worte der Prosa zu prägen, wenn die Seele in Prosa spricht, ist es nicht mehr die Seele. Die Seele ist da, solange sie in Takt, in Rhythmus, im melodiösen Thema, im Bilde, das in der Lautgestaltung liegt, sich ausdrückt, ihre inneren Bewegungen ausdrückt, ihr inneres Aufund Absteigen ausdrückt.

Ich sage immer Deklamieren und Rezitieren, weil das zwei verschiedene Künste sind. Der Deklamator ist immer mehr im Norden zuhause gewesen. Bei ihm handelt es sich darum, vorzugsweise durch das Gewicht der Silben zu wirken - Hochton, Tiefton - und darinnen die Sprachgestaltung zu suchen. Der rezitierende Künstler ist immer mehr im Süden zuhause gewesen. Er drückt in seiner Rezitation das Maß aus, nicht so sehr das Gewicht als das Maß der Silben, lange, kurze Silben. Die scharf sich ausdrückenden griechischen Rezitatoren erlebten den Hexameter, den Pentameter, indem sie genau wußten, sie stellen sich mit ihrem Rezitieren in das Verhältnis zwischen Atmung und Blutzirkulation. Die Atmung verläuft so: achtzehn Atemzüge in der Minute; zweiundsiebzig Pulsschläge durchschnittlich, approximativ in der Minute. Atem, Pulsschlag klingen ineinander, daher der Hexameter: drei lange Silben, als vierte die Zäsur, da mißt ein Atemzug vier Pulsschläge. Dieses Verhältnis eins zu vier, das messend-skandierend im Hexameter zutage tritt - das Innerste des Menschen wird an die Oberfläche gebracht im Skandieren, das Geheimnis, das besteht zwischen Atem und Blutzirkulation.

Das kann natürlich nicht verstandesmäßig theoretisch erlangt werden, das muß ganz instinktiv, intuitiv künstlerisch errungen werden. Aber man kann solche Sachen zum Beispiel schön anschaulich machen, wenn man — wie wir es öfter gemacht haben, wie es auch schon geschehen wäre, wenn Frau Dr. Steiner heute deklamieren und rezitieren könnte — die zwei Gestalten, in denen uns die Goethesche «Iphigenie» vorliegt, hintereinander künstlerisch spricht. Goethe hat, bevor er nach Italien gekommen ist, als nordischer Künstler, wie ihn Schiller später genannt hat, die «Iphigenie» hingeschrieben, so daß das Hingeschriebene nur durch Deklamationskunst wiedergegeben werden kann - Hochton, Tiefton - wo gewissermaßen überwiegt das Blutleben, denn das liegt im Hochton und Tiefton. So hat Goethe zuerst seine «Iphigenie» hingeschrieben. Als er nach Italien gekommen ist, hat er sie umgeschrieben. Man merkt es oftmals nicht, aber wenn man eine feinere künstlerische Empfindung hat, kann man genau die deutsche «Iphigenie» und die römische «Iphigenie » unterscheiden. Goethe suchte überall das Rezitative in seine nordische, deklamatorische «Iphigenie» hineinzubringen. Und da ist die italienische «Iphigenie», die römische «Iphigenie» so geworden, daß man sie nun rezitatorisch lesen muß. Wenn man das hintereinander macht, so findet man diesen wunderbaren Unterschied zwischen Deklamation und Rezitation. In Griechenland war die Rezitation zuhause, da maß der Atem die schnellere Blutzirkulation. Im Norden war mehr das Deklamatorische zuhause, da lebte der Mensch in seinem tiefsten Inneren. Blut ist ein ganz besonderer Saft, denn es ist der Saft, der das innerste Menschliche enthält. Da lebte der menschliche Charakter im Blute, in der Persönlichkeit. Da wurde der dichterische Künstler zum deklamatorischen Künstler.

Solange Goethe nur das Nordische kannte, war er deklamatorischer Künstler, schrieb die deklamatorische deutsche «Iphigenie». Er formte sie um, als er zum Maß besänftigt wurde im Anblicke der von ihm als griechisch empfundenen italienischen Renaissancekunst. Ich will nicht Theorien entwickeln, ich will Ihnen nur Empfindungen schildern, aber diejenigen Empfindungen, die für das Künstlerische eben angeregt werden, wenn man Anthroposoph wird. Und so kommen wir überhaupt wieder hinein in ein richtiges künstlerisches Empfinden von allem.

Ich will nur noch zum Schlusse eines erwähnen. Wie verhalten wir uns denn heute auf der Bühne? Wir denken darüber nach, wenn wir heute im Fond, im Hintergrunde, in den hinteren Partien der Bühne stehen, wie man’s machen würde, wenn man draußen auf der Straße gehen würde und dasselbe tun würde. Man benimmt sich auf der Bühne geradeso, wie man sich auf der Straße oder im Salon benehmen würde. Aber das ist etwas, was ganz gut ist, wenn man’s kann, wenn man dieses Persönliche wieder hineinbringen kann. Aber das führt von der wirklichen Stilkunst ab, die nur im Erfassen des Geistes auch der Bühnenform, der Regieform bestehen kann. Sie müssen bedenken, auf der Bühne können Sie nicht eigentlich naturalistisch sein, denn vor der Bühne sitzt der Zuschauer. Das künstlerische Genießen ist im wesentlichen in das Unbewußte der Instinkte hinuntergetaucht. Es ist etwas ganz anderes, ob ich anfange, mit dem linken Auge etwas ins Auge zu fassen und das an mir vorübergeht, so daß es selbst von rechts nach links, das heißt für mich von links nach rechts geht, oder ob es die entgegengesetzte Richtung hat. Ich empfinde das ganz anders. Das sagt mir etwas ganz anderes. Ich muß wiederum lernen, welche innere geistige Bedeutung es hat, ob sich eine Person auf der Bühne von links nach rechts, oder von rechts nach links, oder vom Fond nach vorne oder nach dem Fond der Bühne bewegt. Ich werde mir eine Empfindung aneignen über das schlechterdings Untunliche, wenn ich mich zu einer längeren Rede auf der Bühne rüste, von vornherein ganz vorne beim Souffleurkasten zu stehen. Wenn ich mich zu einer Rede rüste, so sage ich die ersten Worte möglichst weit zurück auf der Bühne, schreite auf der Bühne vor, mache die Geste des Auseinandergehens der Zuhörer, zu denen ich nach links und rechts spreche. Jede einzelne Bewegung kann geistig erfaßt werden aus dem Gesamtbilde heraus, nicht bloß als naturalistische Nachahmung desjenigen, was man auch im Salon oder auf der Straße tun würde. Aber das heißt, daß man wiederum künstlerisch wird studieren müssen, was es bedeutet, auf der Bühne von rückwärts nach vorne, von rechts nach links, von links nach rechts zu gehen, was überhaupt jede einzelne Bewegung des Schauspielers für das Gesamtbild geistig bedeutet. Das will man heute nicht studieren. Man ist heute bequem geworden. Der Materialismus gestattet Bequemlichkeit. Ich habe mich nur immer gewundert, daß die Leute nicht darauf gekommen sind, wenn sie den vollen Naturalismus verlangt haben — solche Künstler gab es auch -, daß sie auch die vierte Wand gemacht hätten, denn beim vollen Naturalismus müßte man die vierte Wand machen; drei Wände hat kein Zimmer, man müßte die vierte Wand machen. Ich weiß nicht, wie viele Theaterbillette verkauft würden, wenn man die Schauspieler in vier Wänden spielen ließe und dann den Zuschauerraum davor hätte. Aber jedenfalls, ganz naturalistisch werden würde heißen, überhaupt wegschaffen auch diese offene Seite der vierten Wand.

Nun, das klingt paradox, aber durch solche Paradoxa muß man auf dasjenige aufmerksam machen, was heute wieder als wahrhaft Künstlerisches gewonnen werden muß gegenüber den bloßen Imitationen, gegenüber dem bloßen Nachahmungsprinzip. Wir müssen schon, nachdem uns der Naturalismus — denn ich bin wahrhaftig kein Philister und nicht ein Pedant in dieser Beziehung, und kann auch dasjenige schätzen, was mir nicht gerade sympathisch ist, aber ich kann es schätzen — den grandiosen Weg gezeigt hat vom naturalistischen Bühnenbild zum Film, wiederum den Weg zurückfinden vom Film in die Darstellung des Geistigen, das im Grunde genommen die Darstellung des Echten, Wirklichen ist. Wir müssen in der Kunst das Göttlich-Menschliche wiederum finden. Das können wir aber nur finden, wenn wir auch erkenntnismäßig, das heißt anschaubar, wiederum den Weg zum Göttlich-Geistigen zurückfinden.

In dieser Beziehung möchte Anthroposophie - sie hat das durch das leider uns genommene Kunstwerk des Goetheanum in Dornach gewollt - auf dem Felde der bildenden Künste den Weg ins Geistige finden. Sie will ihn auch auf dem Wege der eurythmischen Kunst finden, wie ich schon vorgestern erwähnt habe. Sie möchte aber auch zum Beispiel auf dem Gebiete des Deklamatorischen und Rezitatorischen diesen Weg gehen. Heute geht man naturalistisch vor, man stellt den Atem, man hantiert am menschlichen Organismus herum. Das wirklich Richtige ist, am gesprochenen Satze, der rhythmisch wirklich verläuft, indem man sich selber sprechen hört, auch den eigenen Organismus einzustellen, das heißt am Sprechenlernen das Atmenlernen zu üben. Diese Dinge bedürfen einer Neugestaltung. Aber sie können nicht aus theoretischen, proklamatorischen, agitatorischen Untergründen kommen, sondern einzig und allein aus wirklicher spirituell praktischer Einsicht in die wahren Tatsachen des Lebens, und zu diesen gehören nicht nur die materiellen, gehören durchaus auch die geistigen.

Kunst ist immer eine Tochter des Göttlichen gewesen. Wenn sie wieder den Weg zurückfindet, nachdem sie sich einigermaßen entfremdet hat dem Göttlichen, daß sie wieder an Kindesstatt von dem Göttlichen angenommen werde, dann wird die Kunst wiederum für die ganze Menschheit dasjenige werden können, was sie in der Gesamtzivilisation und in der Gesamtkultur nicht nur sein soll, sondern sein muß.