The Arts and Their Mission

GA 276

1 June 1923, Dornach

Lecture II

One result of anthroposophical spiritual science—once it has been absorbed into civilization—will be a fructification of the arts. Precisely in our time the human inclination toward the artistic has diminished to a marked degree. Even in anthroposophical circles not everyone thoroughly comprehends the fact that Anthroposophy strives to foster, in every possible way, the artistic element.

This is of course connected with modern man's aforementioned aversion to the artistic. Today the positive way in which Goethe and many of his contemporaries sensed the unity of spiritual life and art is no longer experienced. Gradually the conception has arisen that art is something which does not necessarily belong to life, but is added to it as a kind of luxury. With such assumptions prevailing, the upshot is not to be wondered at.

In times when an ancient clairvoyance made for a living connection with the spiritual world, the artistic was considered absolutely vital to civilization. We may feel antipathy for the frequently pompous, stiff character of Oriental and African art forms; but that is not the point at issue. In this and further lectures we shall be concerned, not with our reaction to any particular art form, but rather with the way in which man's attitude places all the arts within the framework of civilization. The necessity is to see a certain connection between today's spiritual life and the attitude toward art previously alluded to.

If today, as is customary, one sees man as the highest product of nature, as a being brought forth at a certain point in earthly evolution (part of an evolutionary series fashioning a variety of beings), one falsifies the position of man in respect to the world; falsifies it because man has, in truth, no right to the self-satisfaction which would enter his soul, inevitably, as an elemental impulse of soul, if he were indeed only the terminal point of natural creation. If the animals had developed in the way currently assumed by natural science, then man, as the highest product of nature, would have to content himself with this status in the cosmos; he would have no call whatsoever to create something transcending nature.

For instance, if in art one wishes to create, as the Greeks did, an idealized human being, one has to be dissatisfied with what nature offers. For, if satisfied, one could never inject into nature something which surpasses her. Similarly, if satisfied with the nightingale's and lark's song, one could never compose sonatas and symphonies; such a combination of sounds would seem untrue; the true, the natural, being exhaustively expressed by the birds.

The naturalistic world-conception demands that those who wish to create something content themselves with imitations of the natural. For it is only when we envisage a world other than the natural one that we can see a transcending of nature as anything but dishonesty and sham.

We must grasp this fact. But present-day human beings do not draw the logical conclusion from naturalism as it affects the arts. What would happen if they did? They would have to demand that people imitate nature; nothing else. Well, but if a Greek prior to Aeschylus had been shown a mere imitation of nature, he would have said something like this: “Why all that? Why let actors speak as people do in everyday life? If you wish to hear such things, go into the street. Why present them on the stage? It is quite unnecessary. The street is a far better place to find out what people say to one another in ordinary life.” In other words, only a person who participates in spiritual life has an impulse for a creative activity transcending the merely natural. Otherwise, where would the impulse come from? In all ages the human souls in which the artistic element flourished have had a definite relation to the spiritual world. It was out of a spirit-attuned state that the artistic urge proceeded. And this relation to the spiritual world will be, forever, the prerequisite for genuine creativity. Any age strictly naturalistic must, to be true to itself, become inartistic, philistine. Unfortunately our own age has an immense talent for philistinism.

Take the individual arts. Pure naturalism can never create an artistic architecture, a high art of building. Today the “art” of building leads away from art. For if people do not have a longing to assemble in places where the spiritual is fostered, they will not construct houses suitable for spiritual impulses, but merely utilitarian buildings. And what would they say of the latter? “Well,” they would say, “we build in order to shelter our bodies, to protect the family; otherwise we would have to camp out in the open”—the idea of utility being primary. Though such an attitude is not, perhaps, because of embarrassment, generally admitted, it is admitted in particular cases. Today many people are offended if the architect of a residence sacrifices anything of expediency to the principle of the beautiful, the aesthetic; and one often hears the statement: “To build artistically is too expensive.” People did not always think like that; certainly not in those ages when human souls experienced a kinship with the spiritual world. Then the feeling about man and his relation to the universe found expression in words somewhat like these: “Here I stand in the world, but as I stand here with a human form in which dwell soul and spirit, I carry within me something which has no existence in purely natural surroundings. When soul and spirit leave this body, then the relation between it and my physical environment will become manifest; this environment will consume my corporeal part. Only on a corpse do the laws of nature take effect.” Which is to say that as long as the human being is not a corpse, as long as he lives here on earth, he can, through his spiritual heritage, through soul and spirit, preserve from the action of physicality the substances and forces which the corpse will eventually claim.

I have often remarked that eating is not the simple process ordinarily imagined. We eat, and the foods entering our organism are products of nature, natural substances and forces. Because they are foreign to us, our organism would not tolerate them if we could not transform them into something totally different. The energies and laws by means of which food is changed do not belong to the physical earthly environment. We bring them with us from another world. These facts and much else were recognized, understood, when people had a relationship with the spiritual world. Today, however, human beings think it is the laws of nature that are active in the roast beef when it rests on the plate, when it touches the tongue, when it has reached the stomach, intestines, blood; they see the laws of nature active everywhere. The fact that roast beef encounters spirit-soul laws which man himself has brought from another world into this one, and which transform it into something completely different—this fact has no place in the consciousness of a merely naturalistic civilization. Paradoxical as it may sound, materialists feel embarrassed to state bluntly the above. Yet they live with this attitude of mind.

It affects our whole artistic attitude. For, in the final analysis, why do we build houses for ourselves today? To be protected while eating roast beef! Well, this is only one detail. But all contemporary thinking tends in that direction.

By contrast, human beings of the past who had a living consciousness of their relationship to the spiritual universe erected their most valuable buildings to protect the human soul against inroads from their physical environment. Of course, when I use modern words in this connection they sound paradoxical. In ancient times people did not express themselves so abstractly. Things were felt, they were sensed subconsciously. But people's feelings, their unconscious sensations, were spiritual. Today we clothe these feelings in well-defined words which convey, not inadequately, what souls experienced in more ancient times. They were aware that, when a man has passed through an earth life, he lays aside his physical body; whereupon soul and spirit must find their way back into the spiritual universe. Consequently, these people were concerned as to how a soul fares after death: how it can find its way back into spiritual worlds.

Today people do not worry about such things, but there were times when this problem of means was a fundamental concern; when (for this is pertinent) people said to themselves: Outside, there are stones; outside, there are plants; outside, animals. When absorbed by man, substances derived from stones, plants, animals, are worked over by the physical body. Its spiritual forces can overcome some minerals—for example, salt. Similarly, it possesses the spirit-soul forces necessary for the overcoming of purely plant constituents, and can transform the animal element into the human element. All of which points up the fact that the physical body is a mediator between the human being who comes down from spiritual worlds and this so alien earth. Thanks to the physical body we can stand upon this earth; can exist among minerals, plants and animals.

But when the physical body has been laid aside, then the naked soul enters a state fitted only for the spiritual world; and having laid aside its body must ask: How can I pass through the impurity of the animals in order to escape from earthly regions? How pass through the plant element which absorbs, attracts and condenses light? How—accustomed to living amid earthly plant-condensed light—pass out into far reaches of quite another condition of light? How, when I can no longer dissolve them through body-juices, pass beyond the soul-impeding minerals massed on every side?

In ancient times, during mankind's evolution, these were religious-cultural anxieties. People pondered on what they had to do for souls, especially dear ones, to help them find the lines, planes, forms, by means of which they could reach the spiritual world. Thus was developed the art of erecting burial vaults, monuments, mausoleums, which embodied in their forms, their lines and planes, that which the discarnate soul requires if it is to be unimpeded by animals, plants and minerals when ready to find its way back to the spiritual world.

These edifices took their characteristic forms directly from the cult of the dead; and if we wish to comprehend how they arose, we must try to understand how the soul, deprived of its body, finds its way back to the spiritual world of its origin. The belief prevailed that, because the soul has a certain relation to the discarded body, it can find the path out into the world of spirit through the architectural forms vaulting above it.

This conviction was one of the fundamental impulses behind the development of ancient architectural forms. Insofar as these forms were artistic and not merely utilitarian, they took their rise from edifices for the dead. In other words, artistic construction was intimately connected with the cult of the dead; or, as in the case of Greece, with the fact that each temple was built for Athena, Apollo or some other god. For just as the human soul was thought to be incapable of unfolding amid minerals, plants and animals, so the divine-spiritual natures of Apollo, of Zeus, of Athena, were thought to be incapable of unfolding amid external nature unless the spirit of man created for them certain congenial forms. Only if we study the way the soul is related to the cosmos can we understand measurements and proportions in the complicated architectural forms of the ancient Orient; forms which are living proof of the fact that the human beings from whose imaginations they sprang said to themselves: “Man in his inner being does not belong to the earth; he is of another world, therefore needs forms which belong to him in his character as a native of that other world.”

No true historical art form can be understood from merely naturalistic principles. To understand we must ask: What lies behind and is inherent in it? For example, here is the human body, the indwelling human soul. The soul, through its inherent nature, desires to unfold in all directions; and the way it would unfold, disregarding the body, the way it desires to carry its being out into the cosmos, becomes an architectural form.

O soul, if you wish to leave the physical body in order to regain a relationship with the cosmos, what aspect will you take on?—this was the question. The forms of architecture were, so to speak, answers.

Within the evolution of mankind this impulse toward outer expression of inner needs continued to work for a long time. But of course today, during the age of abstractions, everything takes on a different appearance. Which does not mean that we should wish to retrieve the past; only to understand it.

Another custom of the past, though not a very ancient past, asking to be understood: churches surrounded by graves. Not every person could have an individual tomb; the church was the common mausoleum. Therefore it was the church which had to answer, through its form, the ancient question of the soul: How [to] unfold, how [to] escape in the right way, from the body connecting me with the physical world? Ecclesiastical architecture bodies forth, as it were, the desire of the soul for its right after-death form.

To repeat: past cultural elements can be understood only in connection with the feelings and intuitions which people had out of the spiritual world. To understand a cemetery-surrounded church we must develop a sense for the feelings which lived in the original builders when they asked: Dear souls leaving us in death, what forms do you wish us to erect so that, while still hovering near your body, you can take them on and be helped? The answer was ecclesiastical architecture, the artistic element in which was directed toward the end of earth life. Certainly, all this undergoes a metamorphosis. What proceeds from the cult of the dead can become the highest expression of life (as in what we attempted for the Goetheanum). But one must understand things; must understand that architecture unfolds out of the principle of the soul's escape from the body, out of the principle of the soul's growing beyond the body, after passing through the portal of death.

And if we look in the opposite direction, toward birth, toward man's passage from the spiritual into the physical world, then I must tell you something which may make you smile, a little, inwardly; or, perhaps, you won't smile; in which case I would say, Thank goodness! For what I am going to say is true. You see, when the soul arrives on earth in order to enter its body, it has come down from spirit-soul worlds in which there are no spatial forms. Thus the soul knows spatial forms only after its bodily experience, only while the after-effects of space still linger on.

But though the world from which the soul descends has no spatial forms or lines, it does have color intensities, color qualities. Which is to say that the world man inhabits between death and a new birth (and which I have frequently and recently described) is a soul-permeated, spirit-permeated world of light, of color, of tone; a world of qualities, not quantities; a world of intensities rather than extensions. Thus in certain primitive, almost-forgotten civilizations, they who descended and dipped into a physical body had the sensation that through it he entered into relation with a physical environment, grew into space. To him the physical body was completely attuned to space, and he said to himself: “This is foreign to me, it was not so in the spirit-soul world. Here I am under the joke of three dimensions [While the book says joke, a better translation of ‘hineingespannt’ might be yoke! – e.Ed.]—dimensions which had no meaning before my descent into the physical world. But color, tone harmonies, tone melodies, have very much meaning in the spiritual world.”

In those ancient epochs when such realities were sensed, man had a strong desire not to take into his being what was essentially foreign to him. At his most perceptive, he sensed that his head had been given him by the spiritual world. For, as I have often remarked, our trunk and limbs in one life become our head in the next; and so on, from life to life. Ancient man felt the adjustment of his lower body to gravity, to the forces circling the earth; felt its imprisonment in space; and felt that what entered his physical body from his environment did not befit him as a human being bearing, within, an impulse from spiritual worlds. He must do something to bring about a harmonization with his new home.

That was why he carried down from spiritual worlds the colors of his garments. Just as, in ancient times, architecture pointed to the end of earth life, to the death-pole, so in times when man had a sense for the artistic meaning of the colors and styles of dress, the art of costuming pointed to the beginning of human life, to the birth-pole.

Thus (I repeat) ancient garments reflected something brought down from pre-earthly existence, reflected a predilection for the colorful, for harmony; and we need not be astonished that at a time when insight into the pre-earthly has withered, the art of costuming has shriveled into dilettantism. For modern clothing hardly conveys the feeling that man wants to wear it because of the way he lived in pre-earthly existence. But if you study the characteristically vivid garments of flourishing primitive cultures you will see that clothing is or can be a fully justified and great art through which man carries something of his pre-earthly life into earth life; just as, through architecture, he would receive impressions relevant to space-free, post-earthly conditions.

Peoples who still wear national costumes express, through them, the pre-earthly relationships which led them into a certain folk community. Their garments remember, as it were, their appearance in heaven.

Often, to find meaningful costumes, you must go back to more ancient times. And you will see not only that there flourished, then, painters, sculptors, and so forth, but that people of other occupations, during the whole period, were highly artistic.

If you look at Raphael's paintings, you will see that Mary Magdalene and the Virgin Mary are clothed quite differently; also that in all his works Raphael gives Mary Magdalene—essentially—her characteristic garment, and the Virgin Mary hers. He did this because he still experienced in living tradition the fact that a soul-spirit being, brought down from heaven, expresses himself through his garments.

Here lies the meaning of costuming. Modern man may say that clothes derive significance through the fact that they provide warmth. Well, certainly, that is one of their materialistic meanings. But it creates no aesthetic forms. Artistry arises always and only through a relation to the spiritual.

This mode in which things stand to the spiritual must be found again if we would penetrate to the truly artistic. And since Anthroposophy takes hold of the spiritual in its immediacy, it can have a fructifying influence upon art. The great secrets of the world and of life which must be revealed out of anthroposophical research will prove to be artistic; will culminate in art.

In this connection we must perceive something anatomical, already referred to. That part of the human organism which was not head during one earth-life transforms itself, dynamically, into head in the subsequent life. Then (this is self-evident) it is filled out with earth-substance. I have often explained that we must not make the silly objection: The physical body having perished, how can a head arise from it? The other objections brought against Anthroposophy are not, as a rule, much more clever; and this one is really cheap. But we are not concerned, here, with the physical filling out; only with a force relationship which can pass through the spiritual world. The relationship of forces which today inheres in all parts of our physical organism below the head (whether those forces move vertically or horizontally, whether they are held together or expand) has a spherical tendency, becoming thereby the force relationship of our head in our next earth life. When the metamorphosis of legs, feet and so forth into head takes place, the higher hierarchies cooperate. For all heavenly spirits work together. Small wonder, then, that the top of the head appears as an image of the vast space arching spherically above us. And that the adjacent area is an image of the atmosphere circling round the earth; of atmospheric forces. One might say: In the upper part of the head we have a faithful image of the heavens; in the middle, an adaptation of the head to forces which triumph in the chest, to all that encircles the earth. For in our chest we need the earth-encircling air, need the light weaving round the earth, and so forth. The whole organism below the head has no form relationship to the head's spherical form—it has a relationship of substance, not of form; but our chest has a definite relationship to our nose, indeed to everything pertaining to the middle part of the head. And if we descend to the mouth, we find that it is related to the third member of the human threefoldness, namely, to the organism devoted to digestion, nutrition, and motion.

We see how what has passed through the heavens to become head on earth (out of the previous headless body-formation) is in its majestic spherical form adapted to the heavens; whereas the middle part comes from what man is through earth-encircling orbits; and the mouth's formation from what earthly man is through earthly substance and the power of gravity.

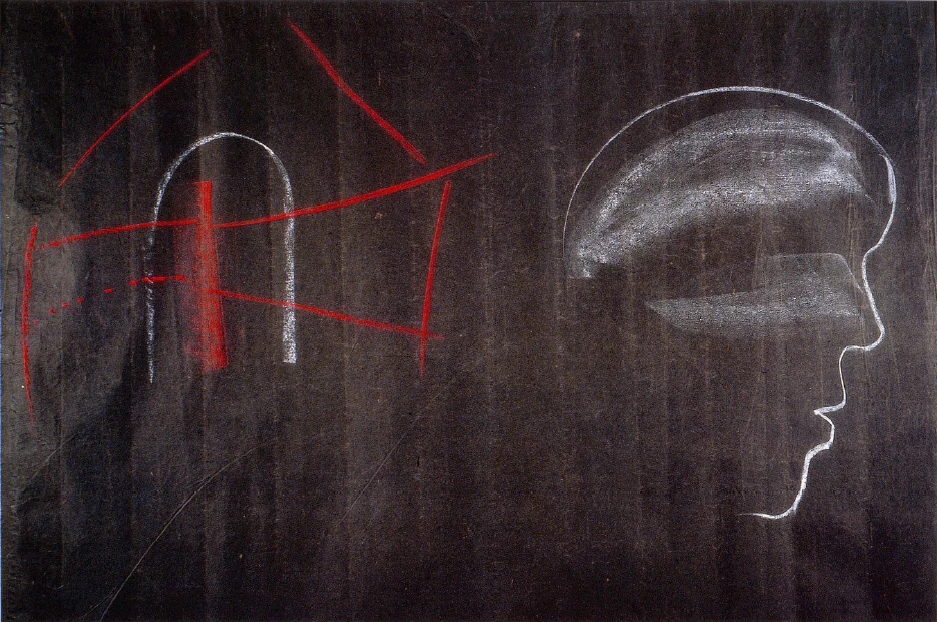

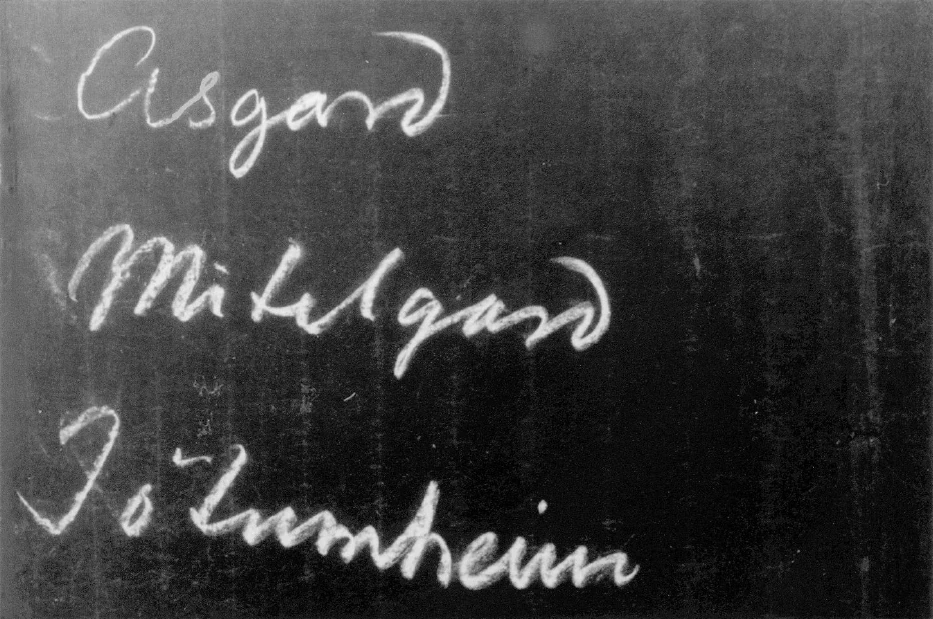

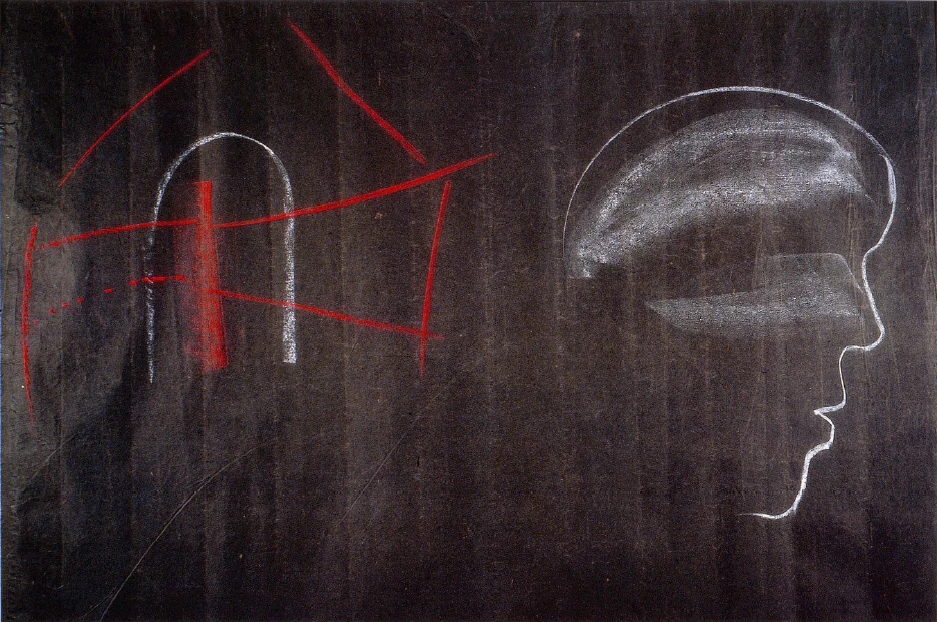

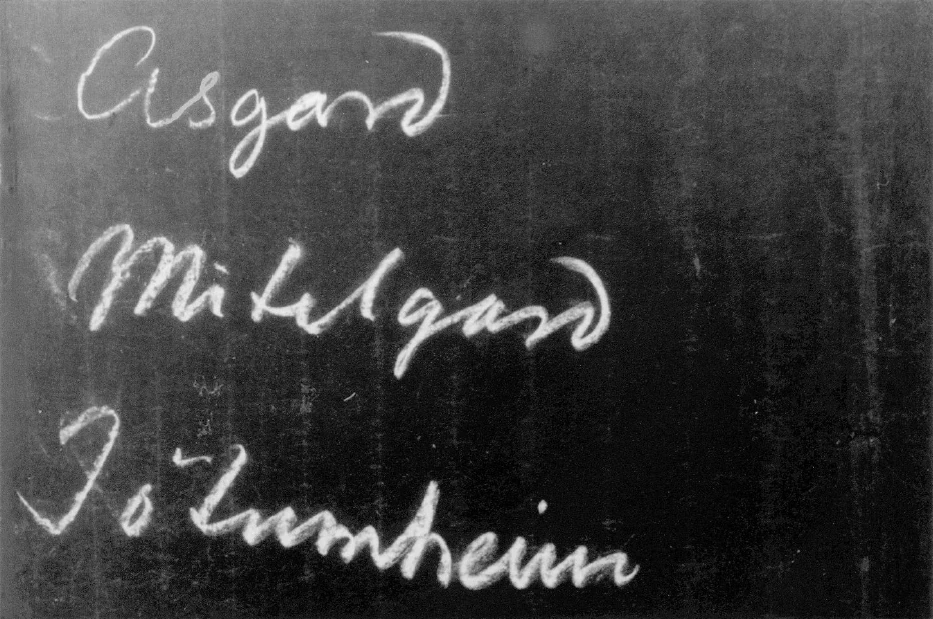

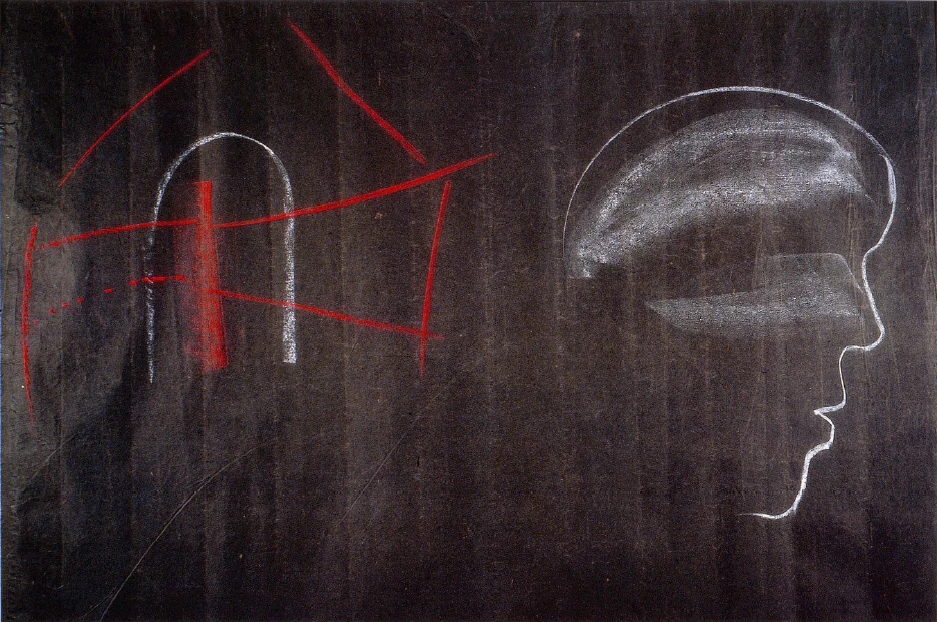

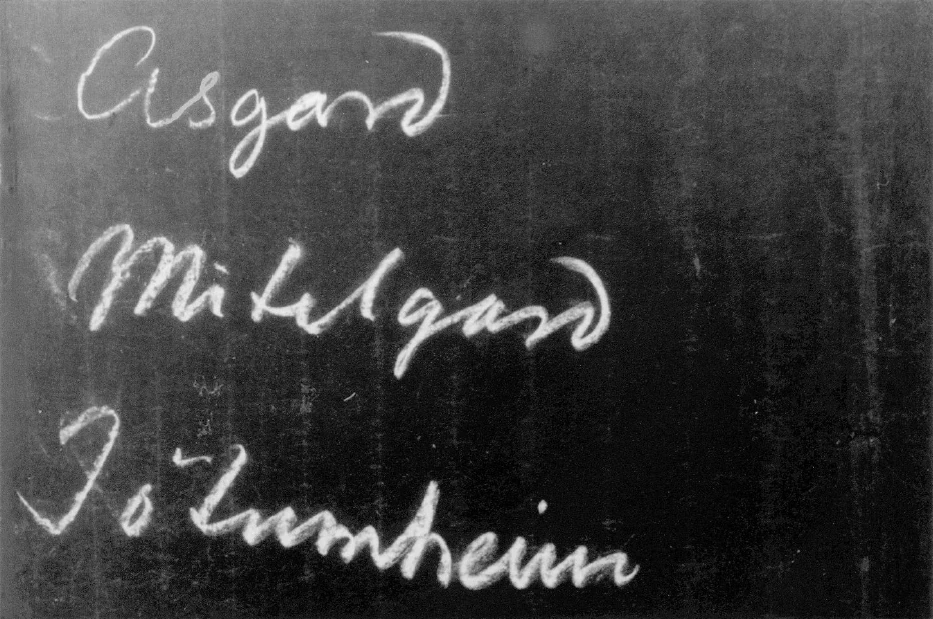

Thus, in terms of European mythology, the head of the human being contains, above, as it were, Asgard, the castle of the gods; in its middle part, Midgard, man's earthly home; and, below, what also belongs to the earth, Jotunheim, home of the giants.

These interrelationships do not become clear through abstract concepts; they become clear only if we perceive the human head artistically, in relation to its spiritual origin; only when we see in it heaven, earth and hell. Not hell as the abode of the devil; hell as the home of the giants, Jotunheim. There lives in the head the entire human being: a whole.

We look at a person in the right way if we see in the spherical form of the upper part of the head the purest memory of his previous incarnation; if we see in the middle part, in the lower portion of the eyes and in nose and ears, a memory dulled by the atmosphere of earth; and in the formation of the mouth, that part of his previous human formation conquered by earth, banished to earth. In the configuration of his forehead the human being brings with him, in a certain sense, what has been passed on to him karmically from his previous earth-life. In the formation of his chin he is conquered by the earthly life of the present age; he expresses gentleness or obstinacy in his chin formation. If his previous organization, minus head, had not transformed itself into his present head, he would not have a chin at all. But in the formation of mouth and chin all current earth impulses are so strong that they press and constrain the past into the present.

Therefore no artistic person will say: That human being is striking because of his prominent forehead. Rather, he will pay special attention to its spherical shape, to the formation of its planes. Its protrusion or recession is less important than its spherical shape.

In regard to the chin he will say: It is advancing, obstinate and pointed; or: It gently recedes. Here we begin to understand the form of man out of the whole universe; not merely out of the present universe—there we find little—but out of the temporal universe, then the extra-temporal.

Thus through anthroposophical considerations we are driven toward the artistic element, and see that philistinism is in no way compatible with a true and living apprehension of Anthroposophy. That is why inartistic people find it so difficult to come into harmony with the whole of this teaching. Though, abstractly, they might with pleasure recognize their present life as the fulfillment of previous earth lives, they are unable to enter intimately into the forms which reveal themselves in direct artistic fashion to spiritual perception, creating and transforming: a necessary activity for anyone desiring to unite with the essential living anthroposophical element.

This is the foundation I wished to lay down in order to show how the unspiritual character of our time manifests in the most varied spheres; among others, in a widespread unspiritual attitude toward art. If mankind desires to save itself from the unspiritual, one factor in its rescue will be a reversal of this position.

A true life in the artistic: to this desirable end Anthroposophy can show the way.

Zweiter Vortrag

Es wird eines der Ergebnisse einer richtig verstandenen und richtig in die Zeitzivilisation eingelebten anthroposophischen Geisteswissenschaft sein, daß sie auf alles Künstlerische befruchtend wirken wird. Es muß gerade in unserer heutigen Zeit stark betont werden, daß die menschlichen Neigungen für das Künstlerische in starkem Maße zurückgegangen sind. Ja, es darf vielleicht sogar gesagt werden, daß innerhalb der anthroposophischen Kreise nicht immer ein volles Verständnis dafür vorhanden ist, daß von uns gesucht wird, innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung Künstlerisches möglichst weitgehend einfließen zu lassen. Das hängt natürlich mit der erwähnten allgemeinen Abneigung der heutigen Menschheit gegen das Künstlerische zusammen.

Man darf sagen, daß in einer starken Art Goethe zuletzt das ganze Geistesleben und die Kunst innerhalb dieses Geisteslebens als eine Einheit empfand, und daß man dann immer mehr und mehr in der Kunst etwas gesehen hat, was eigentlich nicht notwendig in das Leben hineingehört, sondern gewissermaßen zum Leben, man möchte fast sagen wie eine Art Luxus hinzukommt. Kein Wunder, daß unter diesen Voraussetzungen dann auch das Künstlerische vielfach die Gestalt des Luxusmäßigen annimmt.

Nun war gerade älteren Zeiten, die in der Art, wie ich das oftmals dargestellt habe, durch die Reste des alten Hellsehens lebendigen Bezug zur geistigen Welt hatten, das eigen, in dem Künstlerischen etwas zu suchen, ohne das eine allgemeine Zivilisation nicht sein kann. Man mag vom heutigen Gesichtspunkte aus gegen das, sagen wir manchmal Steife orientalischer oder afrikanischer Kunstformen Antipathie haben, aber darum handelt es sich nicht. Es handelt sich uns in diesem Augenblicke nicht darum, wie wir uns zu den einzelnen Kunstformen verhalten, sondern es soll sich uns darum handeln, wie das Künstlerische durch die Gesinnung der Menschen in die allgemeine Zivilisation hineingestellt worden ist. Und darüber wollen wir heute einiges sprechen als Grundlage für Betrachtungen, die wir jetzt und in den folgenden Vorträgen anstellen wollen. Wir müssen einen gewissen Zusammenhang zwischen dem ganzen Charakter des heutigen Geisteslebens und der künstlerischen Gesinnung sehen, die ich gerade mit einigen Worten charakterisierte.

Wenn man das Bestreben hat, den Menschen, so wie man das heute macht, ganz und gar nur als das höchste Naturprodukt, als das höchste Naturwesen anzusehen, als dasjenige Wesen, das sich in der Entwickelungsreihe der anderen Wesen in einem gewissen Zeitpunkte der Erdenentwickelung ergeben hat, dann fälscht man die ganze Stellung des Menschen gegenüber der Welt, weil in Wahrheit der Mensch nicht jenes zufriedene Verhältnis zur Außenwelt haben kann, wenn er sich den elementaren Impulsen in seiner Seele hingibt, die er haben müßte, wenn das wahr wäre, daß er gewissermaßen nur der Schlußpunkt der Naturschöpfung wäre. Wenn sich die Tierreihe einfach so herauf entwickelt hätte, wie das heute von der Wissenschaft als schulwissenschaftlich angesehen wird, dann müßte eigentlich der Mensch, der nichts anderes sein könnte als eben dieses höchste Naturprodukt, restlos von seiner Lage im Weltenall, im Kosmos befriedigt sein. Er müßte nicht ein besonderes Streben haben, etwas über das Natürliche hinaus zu schaffen. Wenn man in der Kunst zum Beispiel etwas schaffen will, wie es die Griechen getan haben im idealisierten Menschen, dann muß man in einem gewissen Sinne unbefriedigt sein in dem, was die Natur gibt. Denn sonst, wäre man befriedigt, würde man nichts in die Natur hineinstellen, was über die Natur hinausgeht. Wäre man mit Nachtigall- und Lerchengesang musikalisch vollständig befriedigt, würde man nicht Sonaten und Symphonien komponieren, denn man würde das als etwas Unwahres, Verlogenes empfinden. Das Wahre, das Natürliche, würde sich erschöpfen müssen im Nachtigallengesang und Lerchengesang. Eigentlich fordert die gegenwärtige Weltenanschauung, daß man sich mit der Nachahmung des Natürlichen begnüge, wenn man überhaupt etwas schaffen will, denn im Augenblicke, wo man über das Natürliche hinaus schafft, muß man dieses Hinausschaffen als etwas Lügenhaftes empfinden, wenn man nicht eine andere Welt noch annimmt als diejenige, welche die natürliche ist. Das sollte man durchaus einsehen.

Nun ziehen natürlich die Menschen der Gegenwart die künstlerische Konsequenz des Naturalismus nicht. Denn was würde herauskommen, wenn man die künstlerische Konsequenz des Naturalismus zöge? Höchstens könnte man die Forderung aufstellen, man dürfe nur dasjenige, was in der Natur da ist, nachahmen. Ja, ein Grieche oder gar ein Angehöriger einer älteren Zivilisation, sagen wir ein Grieche der Zeit vor dem Äschylos, würde gesagt haben, wenn man ihm irgend etwas hätte darstellen wollen, was die Natur bloß nachahmt: Wozu denn das? Wozu Menschen sprechen lassen auf der Bühne, wie sie im Leben sprechen! Da braucht man ja nur auf die Straße zu gehen. Wozu braucht man es sich auf der Bühne vorstellen zu lassen? Es ist ganz unnötig. Auf der Straße hat man das, was einem die Menschen im gewöhnlichen Erdenleben sagen, viel besser. - Er würde das gar nicht verstanden haben, daß man die Natur einfach nachahmen soll. Denn man hat, wenn man an einem Geistesleben nicht teilnimmt, kaum irgendeinen Impuls für irgendeine Gestaltung, die über das Rein-Natürliche hinausgeht. Wo soll man es auch hernehmen, wenn man sich an einem Geistesleben nicht beteiligt? Dann muß man es einfach von dem hernehmen, was man einzig und allein zugibt, nämlich von der Natur. Alle die Zeiten, die für das Künstlerische wirklich ursprünglich schöpferisch waren, standen von der menschlichen Seele aus in einer ganz bestimmten Beziehung zur geistigen Welt. Und auch aus dieser geistgestimmten Beziehung zur geistigen Welt ist das Künstlerische hervorgegangen. Niemals eigentlich wird aus etwas anderem als aus der Beziehung der Menschen zur geistigen Welt das Künstlerische hervorgehen können. Diejenige Zeit, welche nur naturalistisch sein will, müßte, wenn sie innerlich wahr wäre, durchaus unkünstlerisch, das heißt philiströs werden. Und zum Philister hat unsere Zeit wirklich die allermannigfaltigste Anlage.

Nehmen wir einmal die einzelnen Künste selbst. Es wird vom reinen Naturalismus, vom rein Naturalistisch-Philiströsen eine künstlerische Baukunst, wenn ich mich des Pleonasmus bedienen darf - Baukunst führt heute oft sehr weit von der Kunst ab, wenn sie auch Kunst genannt wird -, überhaupt kaum geschaffen werden können, denn wenn die Menschen nicht das Bedürfnis haben, sich an Stätten zu vereinigen, wo Geistiges getrieben wird, und diesen Stätten Häuser bauen wollen, werden sie keine Häuser für geistige Impulse bauen. Sie werden also reine Nützlichkeitsbauten aufführen. Und was werden sie denn über die Nützlichkeitsbauten sagen? Nun, sie werden sagen: Man baut, um sich zu schützen, um den Menschen zu schützen, damit man nicht im Freien kampieren muß, der Familie oder den einzelnen Menschen eine Umhüllung. —- Man wird immer mehr den Schutzgedanken für das Körperlich-Natürliche in den Vordergrund stellen, wenn man von der Baukunst vom naturalistischen Standpunkt aus spricht. Wenn das im allgemeinen vielleicht nicht immer zugegeben wird, weil sich die Leute genieren, es zuzugeben, in den Einzelheiten wird es schon zugegeben. Es gibt heute unzählige Menschen, die nehmen es einem übel, wenn ein Haus, das zum Bewohnen da sein soll, nur irgend etwas, was man für zweckmäßig hält, einem Prinzip des Schönen, des Künstlerischen aufopfert. Man hört heute sogar oftmals die Redensart, künstlerisch bauen, das kommt zu teuer. So wurde nicht immer gedacht, so konnte vor allen Dingen in denjenigen Zeiten nicht gedacht werden, in denen die Menschen in ihrer Seele eine Beziehung zur geistigen Welt empfanden. Denn in diesen Zeiten empfand man über den Menschen und sein Verhältnis zur Welt etwa so: Ich stehe hier in der Welt, aber wie ich da stehe mit dieser menschlichen Gestalt, die von Seele und Geist bewohnt wird, trage ich etwas in mir, was in der rein natürlichen Umgebung nicht vorhanden ist. - Wenn dasjenige, was Geist und Seele ist, diese physische Leibesgestalt verläßt, dann kommt heraus, wie sich die physische Umgebung zu dieser physischen Leibesgestalt verhält. Dann zehrt die physische Umgebung diese Leibesgestalt als Leichnam auf. Da erst wirken die Naturgesetze, wenn man Leichnam ist. Solange man nicht Leichnam ist, auf der physischen Erde lebt, entzieht man durch das, was man aus der geistigen Welt herangebracht hat, durch Seele und Geist des Menschen, die Stoffe und Kräfte, die dann im Leichnam übrig bleiben, dem Wirken der physischen Welt.

Ich habe es öfter ausgesprochen, das Essen ist nicht etwas so Einfaches, wie man es sich gewöhnlich vorstellt. Wir essen, aber wenn die Speise in unseren Organismus kommt, dann ist sie Naturprodukt, Naturstoff und Naturkräfte. Die sind uns ganz fremd. Wir können sie nicht innerhalb unseres Organismus haben. Wir wandeln sie um in unserem Organismus. Wir machen sie zu etwas ganz anderem. Und diejenigen Kräfte und Gesetze, durch die wir die Speisen zu etwas ganz anderem machen, sind nicht die Gesetze der physischen Erdenumgebung, sind die Gesetze, die wir aus einer anderen Welt in die physische Erdenwelt hereintragen. So hat man gedacht in bezug auf dieses, so hat man gedacht in bezug auf vieles andere, als man ein Verhältnis zur geistigen Welt hatte. Heute denken die Menschen: Nun ja, die Naturgesetze, die wirken im Roastbeef, wenn es auf dem Teller liegt, sie wirken im Roastbeef, wenn es auf der Zunge ist, wenn es im Magen, wenn es in den Gedärmen ist, wenn es im Blute ist, immer Naturgesetze! -— Daß da dem Roastbeef geistig-seelische Gesetze entgegenkommen, die der Mensch aus einer anderen Welt in diese Welt hineingetragen hat und die es zu etwas ganz anderem machen, das liegt gar nicht im Bewußtsein einer bloß naturalistischen Zivilisation, so paradox es klingt, denn so in dieser Groteskheit es auszusprechen, genieren sich selbstverständlich die materialistisch gesinnten Menschen. Aber in Wirklichkeit leben sie so, daß sie diese Gesinnung haben. Das überträgt sich dann auch auf die künstlerische Gesinnung, denn letzten Endes — warum bauen wir uns heute Häuser? Damit man am besten geschützt ist für das Roastbeef-Essen! Nun ja - es ist nur eine Einzelheit herausgegriffen selbstverständlich, aber alles, was man so denkt, tendiert schon nach dieser Richtung hin.

Dem gegenüber stellten in denjenigen Zeiten, in welchen die Menschen ein lebendiges Bewußtsein von dem Verhältnis des Menschen zum geistigen Weltenall hatten, für ihre wertvollsten Bauten das Prinzip des Schutzes der menschlichen Seele auf der Erde vor der irdischen Umgebung auf. Natürlich, wenn ich das mit heutigen Worten ausspreche, dann klingt es paradox. Man hat nicht in älteren Zeiten in derselben Weise die Dinge ausgesprochen wie heute. Man war nicht in demselben Sinne abstrakt. Man hat die Dinge mehr gefühlt, unbewußt empfunden. Aber diese Gefühle, diese unbewußten Empfindungen waren spirituell. Wir kleiden sie heute in deutliche Worte. Aber deshalb sprechen sie doch ganz richtig dasjenige aus, was man in älteren Zeiten in den Seelen erlebt hat. Da hätte man gesagt: Wenn der Mensch durch sein Erdenleben durchgegangen ist, muß er seinen physischen Leib ablegen. Dann, wenn er diesen physischen Leib abgelegt hat, muß sein SeelischGeistiges von der Erde aus den Weg ins geistige Weltenall hinaus finden. — Sehen Sie, das war eine wichtige Empfindung, die man einstmals unter Menschen hatte: Wie findet die Seele, wenn sie nun nicht mehr durch den Leib in die Erdenumgebung hineingestellt ist, sich zurecht? - Sie ist da im Tode, sie muß den Weg finden von der Erde in geistige Welten zurück.

Heute sorgen sich natürlich die Menschen nicht um solche Dinge, aber es gab Zeiten, in denen dies eine wesentliche, eine Hauptsorge des Menschen war, wie die Seele den Weg in die geistigen Welten hinaus zurückfindet. Denn man sagte sich, da draußen sind Steine, da draußen sind Pflanzen, da draußen sind Tiere. Alles, was man von Steinen, von Pflanzen, von Tieren haben kann, wird, wenn der Mensch es aufnimmt, von seinem physischen Leibe verarbeitet. Sein physischer Leib hat die geistigen Kräfte, um das Mineralische zu überwinden, wenn er zum Beispiel Salzartiges aufnimmt. Er hat die geistig-seelischen Kräfte, um das Rein-Pflanzliche zu überwinden, wenn er Pflanzliches genießt. Er hat die geistig-seelischen Kräfte, um das Tierische ins Menschliche zu verwandeln, wenn er Tierisches ißt. Und der physische Leib ist der Vermittler zu dem, was dem eigentlichen Menschen, der aus geistigen Welten herunterkommt, von der Erde ganz fremd ist. Mit dem physischen Leib kann man auf der Erde stehen. Mit dem physischen Leib kann man unter irdischen Mineralien, Pflanzen und Tieren sein. Aber wenn der physische Leib abgelegt ist, dann ist die Seele wie nackt da, ist so da, wie sie nur in der geistigen Welt sein kann. Dann müßte die Seele, weil sie den physischen Leib abgelegt hat, sich sagen: Wie komme ich durch das Unreine der Tiere hindurch, um hinauszukommen aus der irdischen Region? Wie kann ich durch dasjenige, was in den Pflanzen das Licht verarbeitet, das Licht anzieht, das Licht verdichtet, wie kann ich aus diesem Pflanzlichen heraus, da ich doch zu den Weiten des Lichtes muß und ich gewöhnt worden bin, auf der Erde in dem verdichteten Lichte durch die Pflanzen zu leben? Wie komme ich über die Mineralien hinaus, die mich überall als Seele stoßen, wenn ich sie nicht durch meine leiblichen Säfte auflösen kann?

Das waren religiös-kulturelle Sorgen in alten Zeiten der Menschheitsentwickelung. Da haben die Menschen nachgesonnen, was sie für die Seelen, insbesondere für diejenigen Seelen, die ihnen wert waren, zu tun haben, damit diese die Linien, die Flächen, die Formen finden, durch die sie in die geistige Welt kommen können. Die Grabgewölbe, die Grabdenkmäler, die Grabbaukünste wurden entwickelt, die im Wesentlichen zunächst in ihren Formen darstellen sollten, was für die Seele da sein muß damit sie, wenn sie des physischen Leibes entblößt ist, nicht sich an Tieren, Pflanzen, Mineralien stößt, sondern längs der architektonischen Linien den Weg zurück in die geistige Welt findet. Deshalb sehen wir, wie in älteren Kulturen sich das unmittelbar aus dem Totenkult charakteristisch herausentwickelt. Wenn wir verstehen wollen, wie die älteren Architekturformen gebildet worden sind, müssen wir überall Rücksicht darauf nehmen zu verstehen, wie die Seele, wenn sie körperentblößt ist, ihren Weg in die geistige Welt zurückfindet. Durch die Mineralien, durch die Pflanzen, durch die Tiere kann sie ihn nicht finden. Durch die Formen, die sich über ihr architektonisch wölbten, glaubte man, da die Seele in einer gewissen Beziehung zum verlassenen Leib stünde, könne sie diesen Weg hinaus in die geistige Welt finden. In dieser Empfindung liegt einer der Grundimpulse für die Entstehung alter architektonischer Formen. Sie sind aus Totenbauten heraus entstanden, insofern die architektonischen Formen künstlerische waren, nicht bloße Nützlichkeitsformen. Das Künstlerische der Baukunst hängt innig mit dem Totenkultus zusammen oder auch damit, daß man wie in Griechenland der Athene, dem Apollo den Tempel baute. Denn gerade so, wie man der menschlichen Seele zuschrieb, daß sie nicht sich entfalten könne, wenn sie sich entfalten soll gegenüber der äußeren umgebenden Natur in Mineralien, Pflanzen, Tieren, so schrieb man auch dem Göttlich-Geistigen des Apollo, des Zeus, der Athene zu, daß sie sich nicht entfalten können, wenn sie umgeben sind von der bloßen Natur, wenn man ihnen nicht aus dem Geistigen des Menschen heraus die Formen schafft, durch welche sich das Seelische in den geistigen Kosmos hinaus entfalten kann. Wie die Seele zum Kosmos steht, das muß man studieren, dann wird man die Maße in den komplizierten Bauformen des alten Orients verstehen. Zugleich sind diese Bauformen des alten Orients ein lebendiger Beweis dafür, daß die Menschen, deren Phantasie diese Bauformen entsprungen sind, sich gesagt haben: Der Mensch ist in seinem Inneren nicht von der Welt, die ihn auf Erden umgibt. Er ist von einer anderen Welt. Daher braucht er Formen, die zu ihm gehören, insofern er aus einer anderen Welt ist. - Aus dem bloßen naturalistischen Prinzip heraus wird keine wahre historische Kunstform verstanden, so daß man sagen kann: Was liegt in den Bauformen? — Nun, hier meinetwillen ist schematisch der menschliche Körper, hier ist die menschliche Seele. Die menschliche Seele will sich allseits entfalten. Wie sie sich entfalten will, abgesehen vom Leibe, wie sie ihr Wesen hinaustragen will in den Kosmos, das wird architektonische Form.

Seele, wenn du verlassen willst deinen physischen Leib, um ein Verhältnis zum äußeren Kosmos zu bekommen, wie willst du dann ausschauen? — Das war die Frage. Die architektonischen Formen waren die leibhaften Antworten auf diese Frage.

Oh, man kann schon fühlen innerhalb der Menschheitsentwikkelung, wie diese Empfindung fortwirkte. In der Zeit der Abstraktionen gewinnt alles einen anderen Anstrich. Wir wollen aber nicht alte Zeiten wieder zurückwünschen, sondern sie verstehen. Wir wollen doch verstehen, wenn wir heute noch in Orte hinauskommen, in denen mancher gar nicht so alte Gebrauch sich noch erhalten hat, warum wir zum Beispiel da an die Kirche herantreten und ringsherum die Gräber sehen. Nicht jeder einzelne konnte ein Grabhaus haben, aber die Kirche war das gemeinsame Grabhaus für alle. Und die Kirche ist die Antwort auf die Frage, welche die Seele sich stellte: Wie möchte ich mich zunächst entfalten, um dem Körper, der mich allein mit der physischen Welt, der Erde verbindet, in der richtigen Weise entkommen zu können? - In der Kirchenform ist gewissermaßen die Begierde der Seele nach ihrer Form, wenn sie den Körper verlassen hat, ausgedrückt.

Kulturelemente, die noch aus älteren Zeiten stammen, können allein verstanden werden, wenn man sie im Zusammenhange mit den Empfindungen, mit den Gefühlen, mit den Intuitionen, die man von der geistigen Welt hatte, versteht. Man muß wirklich eine Empfindung dafür haben, wie sie einmal bei denen da war, welche ursprünglich die Kirche gebaut haben und den Friedhof ringsherum. Man muß eine Empfindung dafür haben, daß bei denen das Gefühl vorhanden war: Liebe Seelen, die ihr von uns wegsterbet, was wollt ihr, daß wir euch als Formen bauen, damit ihr, wenn ihr noch euren Körper umfliegt, wenn ihr noch nahe eurem Körper seid, die Formen schon habt, die ihr annehmen wollt nach dem Tode? - Und da war die Antwort, die man ein für allemal für die fragenden Seelen hinstellen wollte, die Form der Kirche, die Architektonik der Kirche. So werden wir an das eine Ende des Erdenlebens gewiesen, wenn wir zum Künstlerischen der Architektur kommen. Gewiß, das alles metamorphosiert sich. Dasjenige, was aus dem Totenkultus hervorgegangen ist, kann zur höchsten Ausbildung des Lebens werden, wie es auch geworden ist, wie es am Goetheanum versucht worden ist. Aber man muß die Dinge verstehen, muß verstehen, wie die Architektur überhaupt sich aus dem Prinzip des Verlassens des physischen Körpers durch die Seele entfaltet, aus dem Prinzip des Hinauswachsens der Seele über den Leib, wie es faktisch sich vollzieht im Erdenleben, wenn der Mensch durch die Pforte des Todes schreitet.

Blicken wir nach der anderen Seite des Lebens hin, nach der Geburt, nach dem Hereinkommen des Menschen in die physische Welt, da allerdings wird es notwendig sein, daß ich Ihnen etwas sage, worüber Sie vielleicht, oder wenigstens viele unter Ihnen vielleicht — vielleicht auch nicht, dann würde ich sagen: Gott sei Dank — innerlich ein wenig lächeln werden. Aber es ist dennoch eine Wahrheit. Sehen Sie, wenn die Seele auf Erden ankommt, um sich in ihren Körper, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, zu begeben, so kommt sie aus den geistig-seelischen Welten herunter. In diesen geistig-seelischen Welten sind zunächst nicht Raumesformen. Raumesformen kennt die Seele nur, wenn sie ihren Körper verläßt, wo das Räumliche noch nachwirkt. Wenn die Seele herunterkommt, um ihren Körper erst zu beziehen, kommt sie aus einer Welt, in der Raumesformen nicht bekannt sind, in der von unserer physischen Welt Farbenintensitäten, Farbenqualitäten, aber nicht Raumeslinien, nicht Raumesformen bekannt sind. In der Welt, die ich Ihnen in der letzten Zeit öfters beschrieben habe, die der Mensch zwischen dem Tod und einer neuen Geburt durchlebt, lebt er in einer durchseelten, durchgeistigten Licht- und Farben- und Toneswelt, in einer Welt der Qualitäten, der Intensitäten, nicht in einer Welt der Quantitäten, der Ausdehnungen. Und er kommt herunter, taucht in seinen physischen Leib ein, er empfindet - ich schildere jetzt die Empfindung, wie man sie in gewissen, von der Geschichte fast vergessenen, primitiven Zivilisationen hatte —, daß er in seinen physischen Leib untertaucht. Durch den physischen Leib bekommt er sogleich eine Beziehung zur Umgebung: Da wachse ich ja in den Raum hinein. - Dieser physische Leib ist schon ganz auf den Raum gestimmt — das ist mir fremd. Es war nicht so in der geistig-seelischen Welt. Hier werde ich gleich in drei Dimensionen hineingespannt. - Diese drei Dimensionen haben keinen Sinn, bevor man aus der geistig-seelischen Welt in die physische Welt heruntersteigt. Aber Farbiges, Farbenharmonisches, Tonharmonisches, Tonmelodisches, das hat seinen guten Sinn in der geistigen Welt. Da empfand dann der Mensch in jenen alten Zeiten, in denen man solche Dinge eben empfand, ein tiefes Bedürfnis, nicht das an sich zu tragen, was ihm eigentlich fremd ist. Er empfand höchstens sein Haupt als aus der geistigen Welt gegeben. Denn dasjenige, was sein übriger Leib - ich habe das öfter ausgeführt - in früheren Erdenleben war, ist zum Haupte geworden. Der übrige Leib wird erst in dem nächsten Erdenleben zu einem Haupte werden. Diesen übrigen Leib empfindet der Mensch jener alten Zeiten der Schwerkraft angepaßt, den Kräften, die um die Erde herumkreisen. Er empfindet das, wie gesagt, als hineingezwängt in den Raum. Und er empfindet: das, was da in seinen physischen Leib von der Umgebung hereinkommt — mit dem passe ich als Mensch, der etwas aus geistigen Welten herunterträgt, gar nicht zusammen. Ich muß etwas tun, um damit zusammenzupassen.

Sehen Sie, da trägt der Mensch aus den geistigen Welten in die physische Welt die Farbe seiner Bekleidung herein. Führt uns die Architektur an das Todesende des menschlichen Lebens, so führt uns die Bekleidungskunst im Sinne der alten Zeiten, wo man an dem Farbenfrischen, an dem Künstlerischen seiner Kleidung seine Freude, seine Froheit und dafür Verständnis hatte, an das Geburtsende. In den alten Bekleidungen hatte man dasjenige, was die Menschen aus dem vorirdischen Dasein an Vorliebe für Farbiges, für Zusammenstimmendes aus der geistigen Welt hereintrugen. Und es ist gar kein Wunder, daß in der Zeit, in welcher der Ausblick auf das vorirdische Leben abgeschafft wurde, die Bekleidungskünste in den Dilettantismus hineinwuchsen. Denn, nicht wahr, in den heutigen Bekleidungen spüren Sie kaum irgendwie, daß der Mensch das durch die Art und Weise, wie er im vorirdischen Dasein gelebt hat, an sich sehen möchte. Aber studieren Sie wirklich hochgekommene primitive Kulturen in ihrer Farbenfreudigkeit in den Bekleidungen, mit ihrem oftmals charakteristisch Farbigen in den Bekleidungen, dann werden Sie sehen, daß Sie in der Bekleidungskunst eigentlich eine berechtigte große Kunst haben, durch die der Mensch das vorirdische Dasein in das irdische Dasein hereintragen will, wie er durch die architektonische Kunst das nachirdische Dasein aufnehmen möchte, das Dasein, wo er sich dem Raum entringt, ihn noch hat, aber los will vom Raum und das in architektonischen Formen ausdrückt. Sie können heute noch, wenn Sie sich zu Völkerschaften wenden, die ihre Volkstrachten haben, an diesen Volkstrachten die Frage sich beantworten: Wie haben sich eine Anzahl von Seelen zusammengefunden, um das aus der Verwandtschaft, in der sie im vorirdischen Dasein waren und aus der sie sich in einer Volksgemeinschaft gefunden haben, in ihren Bekleidungen zum Ausdruck zu bringen? — Andenken an ihr Aussehen im Himmel wollten die Menschen in ihren Bekleidungen schaffen. Sie werden daher oftmals in ältere Zeiten zurückgehen müssen, wenn Sie sinnvolle Bekleidungen finden wollen.

Aber auf der anderen Seite können Sie wiederum sehen, wie in der Zeit, wo das ganze Menschliche vom Künstlerischen ergriffen war, ob man nun durch die besonderen Verhältnisse, aus denen heraus man kam oder im Hineinwachsen war, Maler wurde oder was anderes, es seinen tiefen Sinn hatte, wenn Sie da eine Magdalena zum Beispiel bei Raffael anschauen oder eine Maria. Die sind ganz anders bekleidet. Aber Sie werden sehen, die MagdalenenKleidung behält dann Raffael für alle seine Magdalenen bei, im wesentlichen auch die Marien-Kleidung wiederum für alle Marien, weil er noch ein Lebendiges, wenigstens eine lebendige Tradition hatte, daß man das Geistig-Seelische, das man vom Himmel auf die Erde herunterbringt, in der Bekleidung zum Ausdrucke bringt. Dadurch bekommt die Bekleidung Sinn. Der heutige Mensch wird sagen, sie bekäme auch Sinn dadurch, daß sie einen wärme. Nun ja, gewiß, das ist der materielle Sinn, aber dadurch entstehen nicht künstlerische Formen. Künstlerische Formen entstehen immer durch die Beziehung zum Geistigen hin. Diese Beziehung zum Geistigen muß man wieder finden, wenn man bis zum wirklich Künstlerischen wieder vordringen will.

Indem Anthroposophie das Geistige in seiner Unmittelbarkeit ergreifen will, kann sie zugleich befruchtend für die Kunst wirken. Denn diejenigen Dinge, die man genötigt ist, als die großen Weltund Lebens-Geheimnisse aus dem anthroposophischen Forschen heraus zu enthüllen, laufen zuletzt selber in Künstlerisches aus. Das muß man richtig erschauen. Was nicht Kopf im vorhergehenden Erdenleben war, das formt sich in seinen Kräfteverhältnissen um, wird Kopf, wird Haupt in dem nachfolgenden Erdenleben. Daß es dann mit physischer Erdenmaterie ausgefüllt wird, ist selbstverständlich. Das habe ich schon oftmals erklärt, daß man natürlich nicht den blödsinnigen Einwand machen darf, der physische Leib ist ganz zugrunde gegangen, wie kann daraus ein Kopf werden. Nun, viel gescheiter sind die andern Einwände in der Regel auch nicht, die gegen Anthroposophie gemacht werden. Natürlich ist der Einwand sehr billig. Aber es handelt sich nicht um die physische Ausfüllung, sondern um den Kräftezusammenhang, der durch die geistige Welt hindurchgeht.

Der Kräftezusammenhang, der heute in unserem ganzen physischen Organismus, Beinorganismus und so weiter ist, ob die Kräfte vertikal oder horizontal sind, zusammenhalten oder auseinanderstreben, rundet sich, wird Kräftezusammenhang für unser Haupt im nächsten Erdenleben. Da aber arbeiten alle höheren Hierarchien mit, wenn diese Umwandelung, die Metamorphose von Beinen, Füßen und so weiter in das Haupt des Menschen geschieht. Da arbeiten die ganzen Himmelsgeister mit. Kein Wunder, daß zunächst das Haupt diejenige Form trägt, durch die es als das Abbild des weiten Raumes erscheint, der sich rund über uns wölbt, daß dann das Nächste erscheint als das Abbild der um die Erde herumkreisenden Atmosphäre und atmosphärischen Kräfte. Man möchte sagen, im oberen Teil des Hauptes hat man das getreue Abbild des Himmels, im mittleren Teil des Hauptes hat man schon die Anpassung des Hauptes an die Brust, an dasjenige, was an all das angepaßt ist, was die Erde umkreist. In unserer Brust brauchen wir die die Erde umkreisende Luft, brauchen wir das die Erde umwebende Licht und so weiter. Wie aber unser ganzer Organismus in keinem Formzusammenhang steht — nur in einem Stoffzusammenhang mit der oberen Wölbung des Hauptes, so steht unsere Brust nun schon in einer Beziehung zur Nasenbildung, zu alledem, was der mittlere Teil des Hauptes ist.

Und kommen wir zum Mund herunter, so steht der Mund bereits zum dritten Gliede in der menschlichen Dreigliederung in Beziehung, zu dem Verdauungs-, zu dem Ernährungs-, zu dem Bewegungsorganismus. Wir sehen, wie sich dasjenige, was durch die Himmel durchgegangen ist, um auf der Erde aus der früheren hauptlosen Leibesbildung Haupt zu werden, in seiner majestätischen Wölbung oben noch an die Himmel anpaßt, wie es sich aber schon im mittleren Teil an dasjenige anpaßt, was der Mensch ist durch den Erdenumkreis, und wie es an das angepaßt ist, was der Mensch durchaus als Erdenmensch ist durch Schwerkraft, durch die irdischen Stoffe, in der Mundbildung.

So enthält das Haupt des Menschen, ich möchte sagen, wenn wir mit den alten Ausdrücken der europäischen Mythologie sprechen wollen: Asgard, die Burg der Götter, oben; Midgard, die mittlere Partie, die eigentliche Menschenheimat auf Erden; dasjenige, was zur Erde zugehört, Jotunheim, die Heimat der Riesen, der irdischen Geister.

Das alles wird einem aber nicht klar, wenn man es nur in abstrakten Begriffen überschaut, das alles wird einem klar, wenn man künstlerisch das menschliche Haupt in seiner Beziehung zu seinem geistigen Ursprung durchschaut, wenn man in diesem menschlichen Haupt Himmel, Erde und Hölle in gewissem Sinne sieht, wobei die Hölle natürlich nicht der reine Teufelsort ist, sondern nur das Jotunheim, das Riesenheim. Und wir haben dann durchaus in dem menschlichen Haupte wiederum den ganzen Menschen.

Man möchte sagen, man sieht recht dieses menschliche Haupt, wenn man in der Wölbung, die das Haupt oben trägt, die reinste Erinnerung sieht an die vorige Erdeninkarnation des Menschen, wenn man in der mittleren Partie, der unteren Augenpartie und in der Nasenpartie, Ohrenpartie, die schon durch die Atmosphäre der Erde getrübte Erinnerung sieht und in der Mundbildung die durch die Erde bezwungene frühere menschliche Bildung, die schon auf die Erde gebannte menschliche Bildung. In seiner Stirnbildung bringt sich der Mensch in einer gewissen Weise dasjenige mit, was ihm karmisch aus seinem früheren Erdenleben überliefert ist. In seiner Kinnbildung ist er schon von dem irdischen Leben der Gegenwart bezwungen, drückt schon Sanftmut oder Eigensinn dieses gegenwärtigen Lebens in seiner besonderen Kinnbildung aus. Er hätte kein Kinn, wenn sich nicht die frühere kopflose oder außerkopfliche Organisation in die gegenwärtige Hauptesorganisation hinein verwandelte. Aber es ist in bezug auf die Mund- und Kinnbildung die Summe der gegenwärtigen Erdenimpulse so stark, daß da schon das Frühere in das Gegenwärtige hereingepreßt, hereingespannt wird. Daher wird niemand sagen, der künstlerisch empfindet, der Mensch ist auffällig durch seine besonders hervorragende Stirne. Das wird man nicht sagen, wenn man künstlerisch empfindet. Man wird immer auf die Wölbung der Stirne, auf die Flächenbildung der Stirne sehen, wird auch in bezug auf das Hervortreten oder Nachhintengehen das Wölbende vorzugsweise ins Auge fassen. Beim Kinn wird man sagen, es ist eigensinnig spitz nach vorne gehend, oder es ist sanft nach rückwärts geformt. Da fängt man an, die Form am Menschen aus dem ganzen Weltenall heraus zu verstehen, und nicht nur aus dem gegenwärtigen Weltenall heraus — da findet man wenig -, sondern aus dem zeitlichen Weltenall heraus, zuletzt auch aus dem außerzeitlichen.

Man findet, wie man durch eine anthroposophische Betrachtung zum Künstlerischen einfach hingetrieben wird, wie wirklich das unkünstlerische Philistertum mit einer wahren, lebendigen Erfassung des Anthroposophischen eigentlich gar nicht mehr vereinbar ist. Deshalb ist es, ich möchte sagen eine solche Misere für unkünstlerische Naturen, sich mit dem Ganzen der Anthroposophie in Einklang zu bringen. Sie möchten abstrakt ganz gerne natürlich im gegenwärtigen Leben die Erfüllung früherer Erdenleben sehen, aber sie vermögen nicht, nun auch wirklich auf die Formen einzugehen, die da schaffend als umgestaltete Gestalten unmittelbar künstlerisch für das geistige Anschauen sich offenbaren. Dafür muß man auch einen Sinn bekommen, wenn man ins wirkliche lebendige Anthroposophische hineingeht.

Das ist, möchte ich sagen, das erste Kapitel, das ich habe geben wollen, um zu zeigen, wie sich auf allen möglichen Gebieten das Ungeistige unserer Zeit zeigt. Es zeigt sich unter anderem das Ungeistige in der ungeistigen Stellung, die man zur Kunst einnimmt. Und es wird, wenn die Menschheit sich überhaupt aus dem Ungeistigen heraus retten will, einer der Faktoren zu dieser Rettung auch die Hinneigung zum Künstlerischen sein. Wahres Leben wiederum im Künstlerischen — Anthroposophie kann dazu führen.

Second Lecture

One of the results of an anthroposophical spiritual science that is correctly understood and properly integrated into the civilization of our time will be that it will have a fruitful effect on everything artistic. It must be strongly emphasized, especially in our time, that human inclinations toward the artistic have declined to a great extent. Indeed, it may even be said that within anthroposophical circles there is not always a full understanding of the fact that we seek to incorporate art as much as possible into the anthroposophical movement. This is, of course, related to the general aversion of today's humanity to art.

It can be said that Goethe, in a powerful way, ultimately perceived the whole of spiritual life and art within this spiritual life as a unity, and that art has increasingly been seen as something that does not necessarily belong in life, but rather as something that is added to life, almost like a kind of luxury. No wonder that under these circumstances, art often takes on the form of luxury.

Now, it was precisely in earlier times, which, as I have often described, had a living connection to the spiritual world through the remnants of ancient clairvoyance, that it was characteristic to seek in art something without which a general civilization cannot exist. From today's perspective, one may feel antipathy toward the sometimes rigid Oriental or African art forms, but that is not the point. At this moment, we are not concerned with how we relate to individual art forms, but rather with how art has been incorporated into general civilization through the attitudes of human beings. And we want to talk about this today as a basis for the considerations we want to make now and in the following lectures. We must see a certain connection between the whole character of today's spiritual life and the artistic attitude that I have just characterized in a few words.

If one strives to view human beings, as is done today, solely as the highest product of nature, as the highest natural being, as the being that has emerged at a certain point in the development of other beings in the course of Earth's evolution, then one falsifies the whole position of the human being in relation to the world, because in truth the human being cannot have that contented relationship to the outside world if he surrenders to the elemental impulses in his soul, which he would have to have if it were true that he were, so to speak, only the final point of natural creation. If the animal series had simply developed as it is now regarded by science as academic, then human beings, who could be nothing other than this highest product of nature, would actually have to be completely satisfied with their position in the universe, in the cosmos. They would not have to have any particular aspiration to create anything beyond the natural. If, for example, one wants to create something in art, as the Greeks did with the idealized human being, then one must, in a certain sense, be dissatisfied with what nature provides. For otherwise, if one were satisfied, one would not add anything to nature that goes beyond nature. If one were completely satisfied with the song of nightingales and larks, one would not compose sonatas and symphonies, because one would perceive them as something untrue, false. The true, the natural, would have to be exhausted in the song of nightingales and larks. Actually, the current worldview demands that we be content with imitating nature if we want to create anything at all, because the moment we create something beyond nature, we must perceive this creation as something false if we do not accept a world other than the natural one. This should be clearly understood.

Now, of course, people today do not draw the artistic consequences of naturalism. For what would be the result if one drew the artistic consequences of naturalism? At most, one could demand that only what exists in nature should be imitated. Yes, a Greek or even a member of an older civilization, say a Greek from the time before Aeschylus, would have said, if someone had wanted to show him something that merely imitated nature: What's the point? Why let people speak on stage the way they speak in life? All you have to do is go out on the street. Why do you need to have it imagined on stage? It's completely unnecessary. On the street, you have what people say to you in ordinary earthly life, much better. He would not have understood at all that one should simply imitate nature. For if one does not participate in intellectual life, one has hardly any impulse for any form of creation that goes beyond the purely natural. Where else can you get it if you don't participate in spiritual life? Then you simply have to take it from the only thing you admit, namely nature. All the periods that were truly original and creative for the arts had a very specific relationship to the spiritual world from the perspective of the human soul. And it was also from this spiritually attuned relationship to the spiritual world that the arts emerged. Art can never really emerge from anything other than the relationship between human beings and the spiritual world. An era that wants to be purely naturalistic would, if it were true to itself, have to become completely unartistic, that is, philistine. And our era really has the most diverse predisposition to philistinism.

Let us take the individual arts themselves. Pure naturalism, pure naturalistic philistinism, becomes artistic architecture, if I may use the pleonasm — architecture today often leads very far away from art, even if it is called art — can hardly be created at all, because if people do not feel the need to gather in places where intellectual pursuits are carried out and want to build houses for these places, they will not build houses for intellectual impulses. They will therefore erect purely utilitarian buildings. And what will they say about these utilitarian buildings? Well, they will say: one builds to protect oneself, to protect people, so that one does not have to camp outdoors, to provide a shelter for the family or the individual. —- When speaking of architecture from a naturalistic point of view, the idea of protection for the physical and natural will increasingly come to the fore. While this may not always be acknowledged in general, because people are embarrassed to admit it, it is acknowledged in the details. Today, there are countless people who resent it when a house that is supposed to be for living in sacrifices something that is considered functional to a principle of beauty or artistry. Today, one often hears the saying that artistic building is too expensive. This was not always the case, especially in those times when people felt a connection to the spiritual world in their souls. For in those times, people felt about human beings and their relationship to the world something like this: I stand here in the world, but as I stand here with this human form, which is inhabited by soul and spirit, I carry within me something that is not present in the purely natural environment. When that which is spirit and soul leaves this physical body, then it becomes apparent how the physical environment relates to this physical body. Then the physical environment consumes this bodily form as a corpse. Only when one is a corpse do the laws of nature take effect. As long as one is not a corpse, living on the physical earth, one withdraws from the workings of the physical world through what one has brought from the spiritual world, through the soul and spirit of the human being, the substances and forces that then remain in the corpse.

I have often said that eating is not as simple as people usually imagine. We eat, but when food enters our organism, it is a natural product, a natural substance, and natural forces. These are completely foreign to us. We cannot have them within our organism. We transform them in our organism. We turn them into something completely different. And the forces and laws through which we turn food into something completely different are not the laws of the physical earthly environment, but the laws that we bring into the physical earthly world from another world. This is how people thought about this, and how they thought about many other things, when they had a relationship with the spiritual world. Today, people think: Well, the laws of nature that operate in roast beef when it is on the plate, they operate in roast beef when it is on the tongue, when it is in the stomach, when it is in the intestines, when it is in the blood, always the laws of nature! That the roast beef is subject to spiritual and soul laws that humans have brought into this world from another world and that make it something completely different is not even in the consciousness of a purely naturalistic civilization, as paradoxical as it may sound, because, of course, materialistically minded people are embarrassed to express it in such grotesque terms. But in reality, they live in such a way that they have this attitude. This then carries over into the artistic attitude, because ultimately — why do we build houses today? So that we are best protected for eating roast beef! Well, of course, this is just one detail picked out, but everything we think tends in this direction.

In contrast, in those times when people had a living awareness of the relationship between human beings and the spiritual universe, they applied the principle of protecting the human soul on earth from the earthly environment to their most valuable buildings. Of course, when I express this in today's words, it sounds paradoxical. In earlier times, things were not expressed in the same way as they are today. People were not abstract in the same sense. They felt things more, sensed them unconsciously. But these feelings, these unconscious sensations, were spiritual. Today we clothe them in clear words. But that is why they express quite correctly what people experienced in their souls in earlier times. People would have said: When a person has gone through their earthly life, they must shed their physical body. Then, when they have shed this physical body, their soul and spirit must find their way out of the earth into the spiritual universe. You see, this was an important feeling that people once had: How does the soul find its way when it is no longer placed in the earthly environment through the body? It is there in death, it must find its way back from the earth to the spiritual worlds.

Today, of course, people do not worry about such things, but there were times when this was an essential, a primary concern of human beings: how the soul finds its way back to the spiritual worlds. For people said to themselves, there are stones out there, there are plants out there, there are animals out there. Everything that can be obtained from stones, plants, and animals is processed by the physical body when a person takes it in. The physical body has the spiritual powers to overcome the mineral when, for example, it takes in something salty. It has the spiritual-soul powers to overcome the purely plant when it enjoys plant-based foods. It has the spiritual-soul forces to transform the animal into the human when it eats animal substances. And the physical body is the mediator to what is completely foreign to the actual human being, who comes down from spiritual worlds, from the earth. With the physical body, one can stand on the earth. With the physical body, one can be among earthly minerals, plants, and animals. But when the physical body is laid aside, the soul is there as if naked, as it can only be in the spiritual world. Then, because it has laid aside the physical body, the soul must say to itself: How can I pass through the impurity of the animals in order to leave the earthly region? How can I get through that which in plants processes the light, attracts the light, condenses the light? How can I get out of this plant world, since I must go to the vastness of the light and have become accustomed to living on earth in the condensed light through the plants? How can I get beyond the minerals that repel me everywhere as a soul, if I cannot dissolve them through my bodily juices?

These were religious and cultural concerns in the ancient times of human development. People pondered what they had to do for souls, especially for those souls that were dear to them, so that they could find the lines, the surfaces, the forms through which they could enter the spiritual world. Burial vaults, memorials, and the art of tomb building were developed, which were essentially intended to represent in their forms what must be there for the soul so that, when it is stripped of its physical body, it does not encounter animals, plants, or minerals, but finds its way back to the spiritual world along architectural lines. This is why we see how this developed directly from the cult of the dead in older cultures. If we want to understand how older forms of architecture were created, we must take into account how the soul, when freed from the body, finds its way back to the spiritual world. It cannot find this way through minerals, plants, or animals. Through the forms that arched architecturally above it, it was believed that since the soul was in a certain relationship to the abandoned body, it could find its way out into the spiritual world. This feeling is one of the basic impulses for the emergence of ancient architectural forms. They arose from funerary structures, insofar as the architectural forms were artistic, not merely utilitarian. The artistic nature of architecture is closely related to the cult of the dead, or to the fact that, as in Greece, temples were built to Athena and Apollo. For just as it was believed that the human soul could not develop if it was to unfold in relation to the external surrounding nature in minerals, plants, and animals, so too was it believed that the divine spirit of Apollo, Zeus, and Athena could not unfold if surrounded by mere nature, if forms were not created for them out of the human spirit through which the soul could unfold into the spiritual cosmos. One must study how the soul relates to the cosmos, then one will understand the dimensions in the complex architectural forms of the ancient Orient. At the same time, these architectural forms of the ancient Orient are living proof that the people whose imagination gave rise to them said to themselves: Man is not, in his inner being, of the world that surrounds him on earth. He is of another world. Therefore, he needs forms that belong to him, insofar as he is from another world. No true historical art form can be understood from the mere naturalistic principle, so that one can say: What lies in the architectural forms? — Well, here, for my sake, is the human body schematically, here is the human soul. The human soul wants to unfold in all directions. How it wants to unfold, apart from the body, how it wants to carry its essence out into the cosmos, that becomes architectural form.

Soul, if you want to leave your physical body in order to establish a relationship with the outer cosmos, what will you look like? — That was the question. The architectural forms were the embodied answers to this question.

Oh, one can already feel within the development of humanity how this feeling continued to have an effect. In the age of abstractions, everything takes on a different hue. But we do not want to wish for the old days to return; we want to understand them. We want to understand why, when we visit places today where some not-so-old customs are still preserved, we approach the church and see graves all around it. Not everyone could have a tomb, but the church was the common tomb for all. And the church is the answer to the question that the soul asked itself: How do I want to develop first in order to be able to escape in the right way from the body that connects me alone to the physical world, the earth? - In a sense, the shape of the church expresses the soul's desire for its form once it has left the body.

Cultural elements that date back to earlier times can only be understood when viewed in connection with the sensations, feelings, and intuitions that people had about the spiritual world. One must truly have a sense of how it once was for those who originally built the church and the cemetery around it. One must have a sense that they had the feeling: Dear souls who are dying away from us, what do you want us to build for you as forms, so that when you are still flying around your bodies, when you are still close to your bodies, you already have the forms that you want to take on after death? And there was the answer that they wanted to provide once and for all for the questioning souls: the form of the church, the architecture of the church. Thus, when we come to the artistic aspect of architecture, we are pointed to the one end of earthly life. Certainly, all this undergoes metamorphosis. That which has emerged from the cult of the dead can become the highest development of life, as it has indeed become, as has been attempted at the Goetheanum. But one must understand things, must understand how architecture unfolds from the principle of the soul leaving the physical body, from the principle of the soul growing out of the body, as it actually happens in earthly life when a person passes through the gate of death.

If we look at the other side of life, at birth, at the human being's entry into the physical world, then it will be necessary for me to tell you something that you, or at least many of you, may smile about inwardly — or perhaps not, in which case I would say: thank God. But it is nevertheless a truth. You see, when the soul arrives on earth to enter its body, if I may express it that way, it comes down from the spiritual-soul worlds. In these spiritual-soul worlds, there are initially no spatial forms. The soul only knows spatial forms when it leaves its body, where the spatial still has an effect. When the soul comes down to enter its body for the first time, it comes from a world in which spatial forms are unknown, in which the intensities and qualities of color from our physical world are known, but not spatial lines or spatial forms. In the world that I have often described to you recently, which human beings experience between death and a new birth, they live in a world of light, color, and sound that is imbued with soul and spirit, in a world of qualities and intensities, not in a world of quantities and expansions. And they come down, immerse themselves in their physical body, and feel — I am now describing the feeling as it was experienced in certain primitive civilizations that have been almost forgotten by history — that they are submerged in their physical body. Through the physical body, they immediately establish a relationship with their surroundings: I am growing into space. This physical body is already completely attuned to space — that is foreign to me. It was not like that in the spiritual-soul world. Here I am immediately stretched into three dimensions. These three dimensions have no meaning until one descends from the spiritual-soul world into the physical world. But color, color harmony, tone harmony, tone melody—these have their good meaning in the spiritual world. In those ancient times, when people felt such things, they felt a deep need not to carry within themselves what was actually foreign to them. At most, they felt that their head was given to them from the spiritual world. For what their rest of their body was in earlier earth lives — as I have often explained — has become the head. The rest of the body will only become a head in the next earth life. People in those ancient times felt that the rest of their body was adapted to gravity, to the forces that circle around the earth. As I said, they feel it as if it were forced into space. And they feel that what comes into their physical body from their surroundings does not fit at all with them as human beings who carry something down from the spiritual worlds. They must do something to fit in with it.