The Arts and Their Mission

GA 276

2 June 1923, Dornach

Lecture III

Yesterday I tried to show how the anthroposophical world-conception stresses, more intensively than is possible under the influence of materialism, the artistic element; and how Anthroposophy feels about architecture, about the art of costuming (though this may call forth smiles), and about sculpture as dealing artistically with the form of man himself, whose head, in a certain sense, points to the whole human being.

Let us review the most important aspects of this threefold artistic perception of the world. In architectural forms we see what the human soul expects when it leaves the physical body at death or otherwise. During earth life the soul is (so I said) accustomed to enter into spatial relations with its environment through the physical body, and to experience spatial forms. But these are only outer forms. When at death the human soul leaves the physical world, it tries, as it were, to impress its own form on space; looks for the lines, planes and forms which can enable it to grow out of space and into the spiritual world. These are the forms of architecture insofar as they are artistic. Thus, if we would understand architecture's artistic element we must consider the soul's space-needs after it has left the three-dimensional body and three-dimensional world.

The artistic element in costuming represents something else; and I have described the joy of primitive people in their garments, and their sense—on dipping down into the physical body—of finding in it a sheath which did not harmonize with what they had experienced during their sojourn in the spiritual world; and how out of this deprivation there arose an instinctive longing to create clothes which in color and pattern corresponded to their memory of pre-earthly existence. The costumes of primitive peoples represent what might be called an unskillful copying of the astral nature of man as it existed before he entered earthly life.

Thus a contrast. Whereas architecture shows the human soul's striving on its departure from the body, the art of costuming shows the human soul's striving after descent into the physical world.

Which brings us to a consideration of sculpture.

If we feel, intimately, the significance of the formation of man's head (my last point yesterday) as a metamorphosis of his entire body formation minus head, during his previous incarnation; if we see it as the work of the higher hierarchies on the force relationship of a previous life, then we understand the head, especially its upper part. If, on the other hand, we see correctly the middle of man's head, his nose and lower eyes, then we understand how this part is adapted to his chest formation, for the nose is connected with the chest's breathing. And if we see correctly the lower head, mouth and chin, then we understand that, even in the head, there is a part adapted to the purely earthly. In this way we can understand the whole human form. Furthermore, the super-sensible human being manifests himself directly in the arching of the upper skull, and the protrusion or recession of the lower skull, the facial parts. For an intimate connection exists between the vaulting of the head and the heavens; also an inner connection between the middle of the face and everything circling the earth as air and ether; also between mouth and chin and man's limb and metabolic system, the last an indication of how man is fettered to earth. In this way we can understand the whole human form as an imprint of the spiritual on the immediate present; which means seeing man artistically.

To sum up: in sculpture we behold, spiritually, the human being as he is placed into the present; in architecture we behold something connected with his departure from the body; and in the art of costuming something connected with his entrance into that body. Which means a sharp contrast: whereas architecture begins with the erection of tombs, sculpture shows how man, through his earthly form's direct participation in the spiritual, constantly overcomes the earthly-naturalistic element, how, in every detail of his form and in its entirety, he is an expression of the spiritual.

Thus we have considered those arts which are concerned with spatial forms and which illustrate the different ways in which the human soul is related to the world through the physical body.

If we approach a step nearer the spaceless, we pass from sculpture to painting, an art experienced in the right way only if we take into full account its special medium.

Today, in the fifth post-Atlantean age, painting has assumed a character leading to naturalism. Its prime manifestation is the loss of a deeper understanding for color. The intelligence employed in contemporary painting is a falsified sculptural one. Painters see even human beings this way. The cause is space-perspective, an aspect of painting developed only after the fifth post-Atlantean period. Painters express through lines the fact that something lies in the background, something in the foreground; their purpose being to conjure up on canvas an impression of spatially formed objects. But in doing so they deny the first and foremost attribute of their special medium. A true painter does not create in space, but on the plane, in color, and it is nonsense for him to strive for the spatial.

Please, do not believe me so fantastic as to object to a feeling for space; in the evolution of mankind the development of spatial perspective on the plane was a necessity; that fact is self-evident. But it must now be overcome. This does not mean that in the future painters should be blind to spatial perspective, only that, while understanding it, they should return to color-perspective, employ color-perspective.

To accomplish this we must go beyond theoretic comprehension; the artistic impulse does not spring from theory; it requires something more forceful, something elemental. Fortunately it can be provided. For that purpose I suggest that you look again at some words of mine about the world of color as reported excellently by Albert Steffen in the weekly Das Goetheanum.1Vol. II, 1922, No. 7-9: Vortraege Rudolf Steiner's ueber das Wesen der Farbe, (Rudolf Steiner's Lectures Concerning the Nature of Color.) (The report reads better than the original lectures.) This is the first aspect.

I shall now deal with the second problem.

In nature we see objects which can be counted, weighed and measured; in short, objects dealt with in physics. They appear in various colors. Color, however—this should have become perfectly clear to anthroposophists—color is something spiritual. Now we do see colors in certain natural entities which are not spiritual; that is, in minerals. Recent physicists have made matters easier for themselves by saying that colors cannot inhere in dead substances because colors are mental; they exist within the mind only; outside, material atoms vibrating in dead matter affect eye, nerve, and something else undetermined; as a result of which colors arise in the soul.

This explanation shows physicists at a loss in regard to the problem of color. To throw light on it, let us consider from a certain aspect the colorful dead mineral world.

As pointed out, we do see colors in purely physical things which can be counted, measured, weighed on scales. But what is perceived in physics does not give us colors. We may employ number, measure and weight to our heart's content: we will not arrive at color. That is why physicists say that colors exist only in the mind.

I would like to explain by way of an image. Picture to yourselves that I hold in my left hand a red sheet, in my right a green one, and that with these colored sheets I carry out certain movements. First I cover the red with the green, then the green with the red, making these motions alternately; and in order to give them more character do something additional: move the green upward, the red downard. Say I have today carried out this maneuvre. Now let three weeks pass, at which time I bring before you not a green and red sheet, but two white sheets, and repeat the movements. You immediately remember that, contrary to my present use of white sheets, three weeks ago I produced certain visual impressions with a red and a green sheet. For politeness' sake let us assume that all of you have such a vivid imagination that, in spite of my moving white sheets, you see before you, through recollecting phantasy, the colored phenomenon of three weeks ago, forget all about the white sheets and, because I carry out the same motions, see the same color harmonies called forth, three weeks ago, with the red and green. Because I carry out the same gestures, by association you see what you saw three weeks ago.

The case is similar when we see in nature, for instance, a green precious stone. Only, the jewel is not dependent on this moment's soul-phantasy; it appeals to a phantasy concentrated in our eye, for this human eye with its blood and nerve fibers is in truth constructed by phantasy; it is the result of an effective imagination. And inasmuch as our eye is an organ imbued with phantasy, we cannot perceive a green gem in any other way than that in which, in the immeasurably distant past, it was spiritually constructed out of the green color of the spiritual world. The moment we confront a green precious stone, we transport our eye back into ages long past, and green appears because at that time divine-spiritual beings created this substance through a purely spiritual green. The moment we see green, red, blue, yellow, or any other color in a precious stone, we look back into an infinitely distant past. For (to repeat for emphasis) in beholding colors, we do not merely perceive what is contemporary, we look back into distant time-perspectives. Thus it is quite impossible to see a colored jewel merely in the present, just as it is impossible, while standing at the foot of a mountain, to see in close proximity the ruin at its top; being removed from it, we have to see it in perspective.

In confronting a topaz, say, we look back into time-perspective; look back upon the primal foundation of earthly creation, before the Lemurian epoch of evolution, and see this precious stone created out of the spiritual; that is why it appears yellow. Physics (I have characterized a recent stand) does something absurd. It places behind the world swirling atoms which are supposed to produce colors within us, when all the time it is divine-spiritual beings, creative in the infinitely distant past, who call forth, through colored minerals, a living memory of primeval acts of creativity.

And we can press on to the plant world.

Every spring, when a green carpet of plants is spread over the earth, whoever is able to understand this emergence of greenness sees not merely the present, but also the ancient Sun existence when the plant world was created out of the spiritual, in greenness. We see both mineral and plant colors in the right way when they stimulate us to see in nature the gods' primeval creative activity.

This requires an artistic living with color, which involves experiencing the plane as such. If someone covers the plane with blue, we should sense a retreat, a drawing back; if with red or yellow, we should feel an approach, a pressing forward. In other words, we acquire color-perspective instead of linear perspective: a sense for the plane, for the withdrawal and surging forward of color. In painting, the linear perspective which tries to create an impression of something essentially sculptural upon the plane falsifies; what must be acquired is a sense for the movement of color: intensive rather than extensive. Thus, if a true painter wishes to depict something aggressive, something eager to jump forward, he uses yellow-red; if something quiet, something retreating into the distance, blue-violet. Intensive color-perspective! A study of the old masters reveals that some early Renaissance painters still had what belonged to all pre-Renaissance painters: a feeling for color-perspective. Only with the advent of the fifth post-Atlantean period did linear perspective displace color-perspective.

It is through color-perspective that painting gains a relationship to the spiritual. Strange that today painters chiefly ask themselves: Can we by rendering space more spatial transcend space? Then they try to depict, in a materialistic manner, a fourth dimension. But the fourth dimension can exist only through annihilation of the third, somewhat as debts annihilate wealth. For we do not, on leaving three-dimensional space, enter a four-dimensional space; or, better said, we enter a four-dimensional space which is two-dimensional, because the fourth dimension annihilates the third; only two remain as reality. If we rise from matter's three dimensions to the etheric element, we find everything oriented two-dimensionally, and can understand the etheric only if we conceive of it so. Now you may demur: Yes, but in the etheric I move from here to there, which is to say three-dimensionally. Very well, but the third dimension has no significance for the etheric, only the other two dimensions. The third dimension expresses itself through red, yellow, blue, violet, in the way explained; for in the etheric it is not the third dimension which changes, but color. Regardless of where the plane is placed, the colors change accordingly. Only then can we live with and in color; live two-dimensionally; rise from the spatial arts to those which, like painting, are two-dimensional. We overcome the merely spatial. Our feelings have no relation to the three space-dimensions; only our will. By their very nature, feelings are bound within two dimensions. That is why they are best represented by two-dimensional painting.

You see, we have to struggle free from three-dimensional matter if we would advance from architecture, costuming as an art, and sculpture. Painting is an art which man can experience inwardly. Whether he creates as a painter or just lives in and enjoys a painting, it is a soul event. He experiences inner by outer; experiences color-perspective. We cannot say, as in the case of architecture, that the soul is striving to create the forms it needs when it gazes back into the body; nor, as in the case of sculpture, that the soul is trying to depict man's shape in such a way that it is placed into space full of present meaning. None of this concerns painting. It makes no sense in painting to speak of anything as inside or outside; of the soul as inside or outside. In experiencing color the soul is within the spiritual. Really, what is experienced in painting—despite the imperfections of pigments—is the soul's free moving about in the cosmos.

With music it is different. Now we do not merge inner with outer, but enter directly into that which the soul experiences as the spiritual or psycho-spiritual; leave space entirely. Music is line-like, one-dimensional; is experienced one-dimensionally in the line of time. In music man experiences the world as his own. Now the soul does not assert something it needs upon descending into or leaving the physical; rather it experiences something which lives and vibrates here and now, on earth, in its own soul-spirit nature. Studying the secrets of music, we can discover what the Greeks, who knew a great deal about these matters, meant by the lyre of Apollo. What is experienced musically is really man's hidden adaptation to the inner harmonic-melodic relationships of cosmic existence out of which he was shaped. His nerve fibers, ramifications of the spinal cord, are marvelous musical strings with a metamorphosed activity. The spinal cord culminating in the brain, and distributing its nerve fibers throughout the body, is the lyre of Apollo. Upon these nerve fibers the soul-spirit man is “played” within the earthly sphere. Thus man himself is the world's most perfect instrument; and he can experience artistically the tones of an external musical instrument to the degree that he feels this connection between the sounding of strings of a new instrument, for example, and his own coursing blood and nerve fibers. In other words, man, as nerve man, is inwardly built up of music, and feels it artistically to the degree that he feels its harmonization with the mystery of his own musical structure.

Thus, in devoting himself to the musical, man appeals to his earth-dwelling soul-spirit nature. The discovery by anthroposophical vision of the mysteries of this nature will have a fructifying effect, not just on theory, but upon actual musical creation.

In discussing the various arts I have not been theorizing. It is not theorizing when I say: In beholding the lifeless material world in color we stir cosmic memory: and through anthroposophical vision learn to understand how in precious stones, in colored objects of all kinds, we call to mind the creative acts of the primordially active gods; and feel, therefore, the enthusiasm which only an experience of the spiritual kindles. This is no theorizing; this permeates the soul with inner force. Nor does any theory of art emerge therefrom. Only artistic creation and enjoyment are stimulated. For true art is an expression of man's search for a relationship with the spiritual, whether the spiritual longed for when his soul leaves the body, or the spiritual which he desires to remember when he dips down into a body, or the spiritual to which he feels more related than to his natural surroundings, or the spiritual as manifested in colors when outside and inside lose their separateness and the soul moves through the cosmos, freely, swimming and hovering, as it were, experiencing its own cosmic life, existing everywhere; or (our last consideration) the spiritual as expressed in earth life, in the relationship between man's soul-spirit and the cosmic, in music.

Which summary brings us to the world of poetry and drama.

Often in the past I have called attention to the way poetry was felt in ancient times when man still had a living relationship to the spirit-soul world, when poetry, including poetic dramas, by reason of that fact, was artistic through and through. Yesterday I pointed out that in artistic ages it would not have been considered sensible for playwrights to copy on the stage the way Smith and Jones move in the market place of Gotham or at home, inasmuch as their movements and conversation, there, are much richer than in any stage representation; that it would have seemed absurd, for instance, to the Greeks of the classical age; they never could have understood naturalism's strange attempt to imitate nature right down to “realistic” stage sets. Just as it would not be true painting if we tried to project color into three-dimensional space instead of honoring its own dynamics, so it is not stage art if we have no artistic feeling for its own particular medium. Actually a thorough-going naturalism would preclude a stage room with three walls and an audience in front of it. There are no such rooms; in winter we would freeze to death in them. To act entirely naturalistically one would have to close the stage with a fourth wall and play behind it. But how many people would buy tickets to a play enacted on a stage closed on four sides? Though speaking in extremes, I refer to a reality.

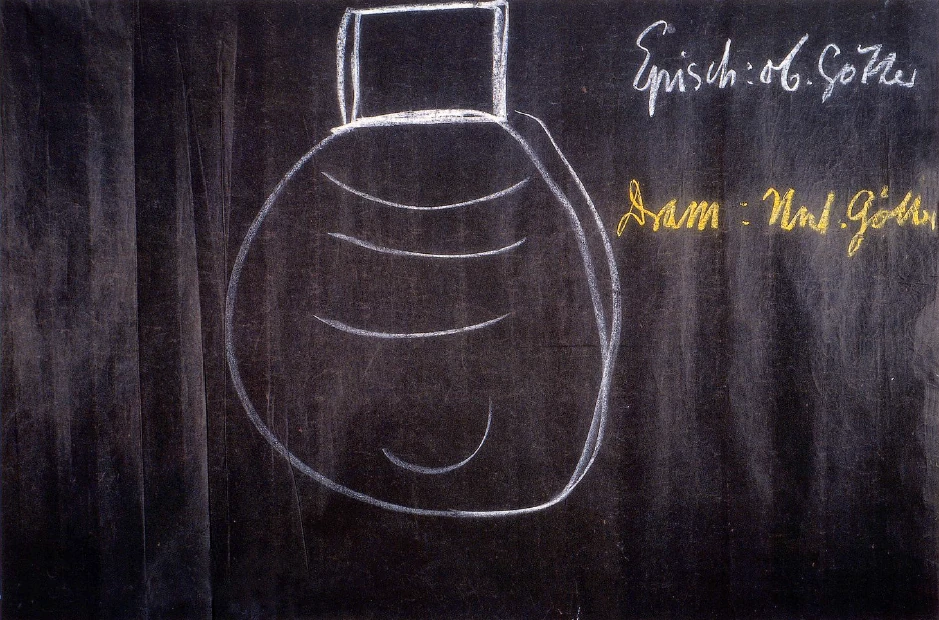

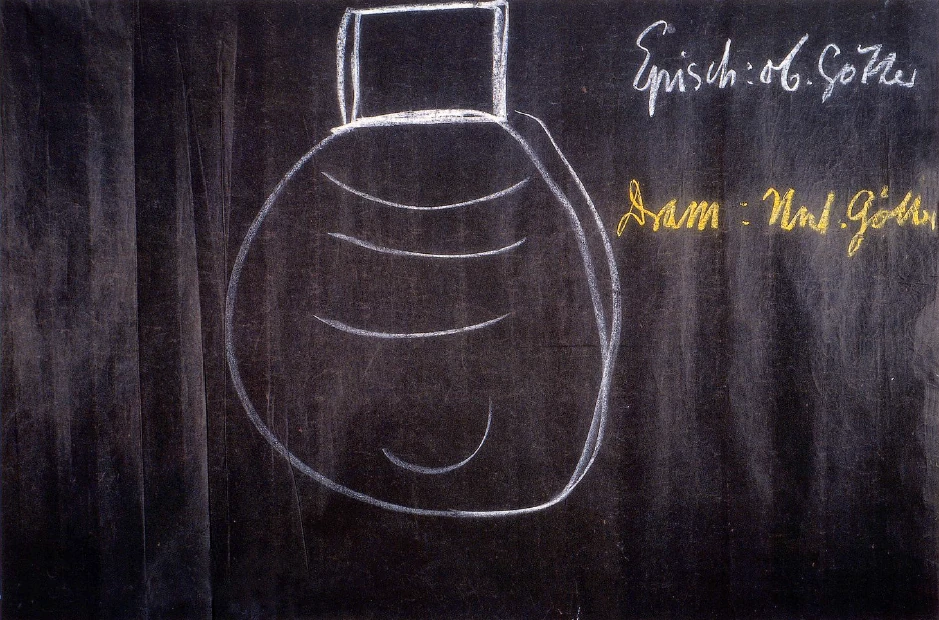

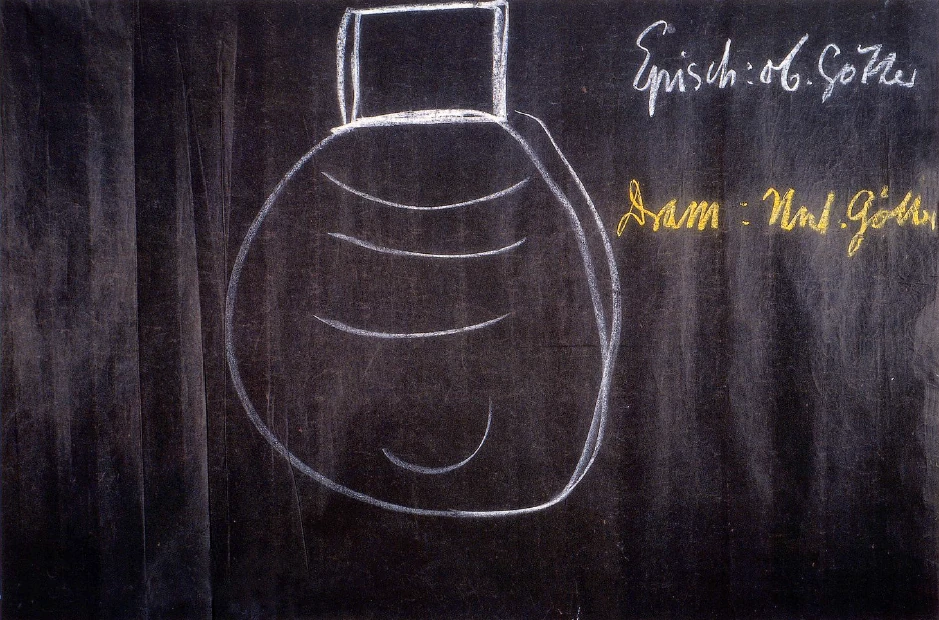

Now I must draw your attention again to the way Homer begins his Iliad: “Sing, oh Goddess, the wrath of Achilles, Son of Peleus.” This is no mere phrase. Homer experienced in a positive way the need to raise himself up to the level of a super-earthly divine-spiritual being who would make use of his body in artistic creation. Epic poetry points to the upper gods, those considered female because they transmitted fructifying forces: the Muses. Homer had to offer himself up to these upper gods in order to bring to expression, in the events of his great poem, the thought element of the cosmos. Epic poetry always means letting the upper gods speak; means putting one's person at their disposal. Homer begins his Odyssey this way: “Tell me, oh Muse, of that ingenious hero who wandered afar,” meaning Odysseus. Never would it have occurred to him to impose upon the people something which he himself had seen or thought out. Why do what everybody can do for himself? Homer put his organism at the disposal of the upper divine-spiritual beings that they might express through him how they perceived earthly human relationships. Out of such a collaboration arises epic poetry.

And the art of the drama? It originated—we need only to think of the period prior to Aeschylus—from a presentation of the god Dionysus working up out of the depths. At first it was Dionysus alone, then Dionysus and his helpers, a chorus grouped around him as a reflection of what is carried out, not by human beings, but by the subterranean gods, gods of will, making use of human beings to bring to manifestation not the human but divine will. Only gradually, in Greece, as man's connection with the spiritual fell into oblivion, did the divine action depicted on the stage turn into purely human action. The process took place between the time of Aeschylus, when divine impulses still penetrated human beings, and the time of Euripides, when men appeared on the stage as men, though still bearing super-earthly impulses. Real naturalism became possible only in modern times.

In poetry and drama man must find his way back to the spiritual.

Thus we may say in summary: Epic poetry turns to the upper gods, drama to the lower gods. True drama shows the divine world lying below the earth, the chthonic world, rising up onto the earth for the reason that man can make himself into an instrument for the action of this netherworld. In contrast, epic poetry sees the upper spiritual world sink down; the Muse descends and, making use of man through his head, proclaims man's earthly accomplishments or else those out in the universe. In drama the subterranean will of the gods rises up from the depths, making use of human bodies in order to give free reign to their wills.

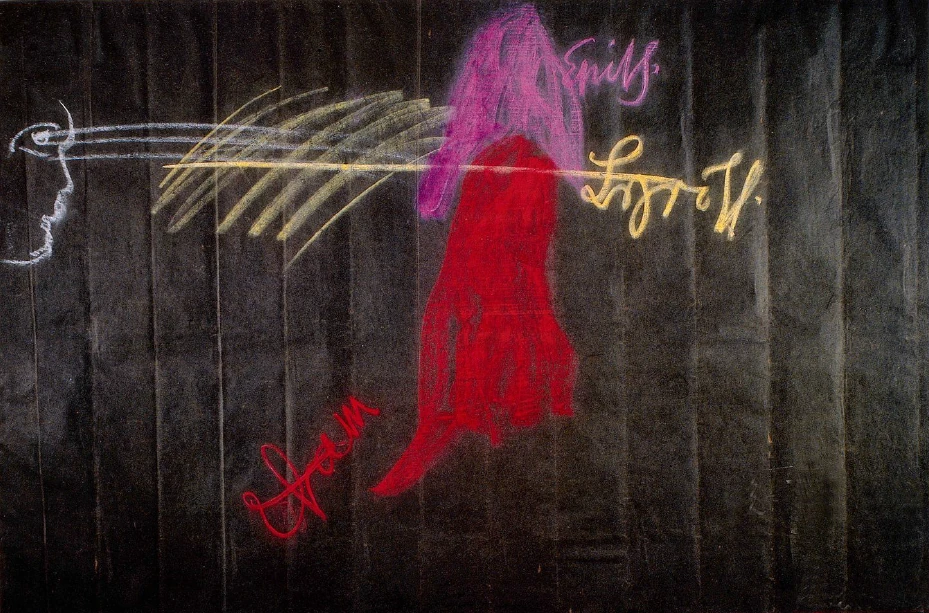

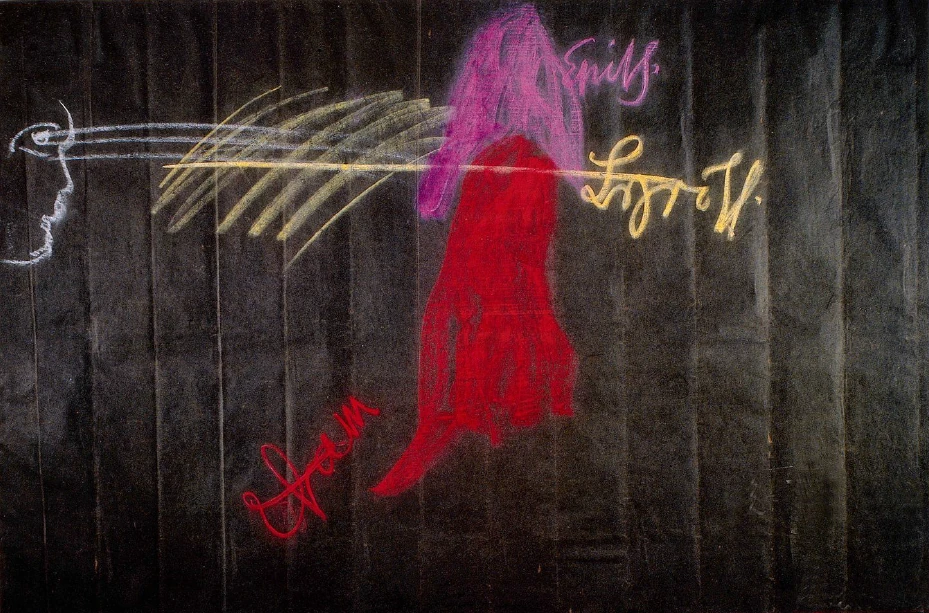

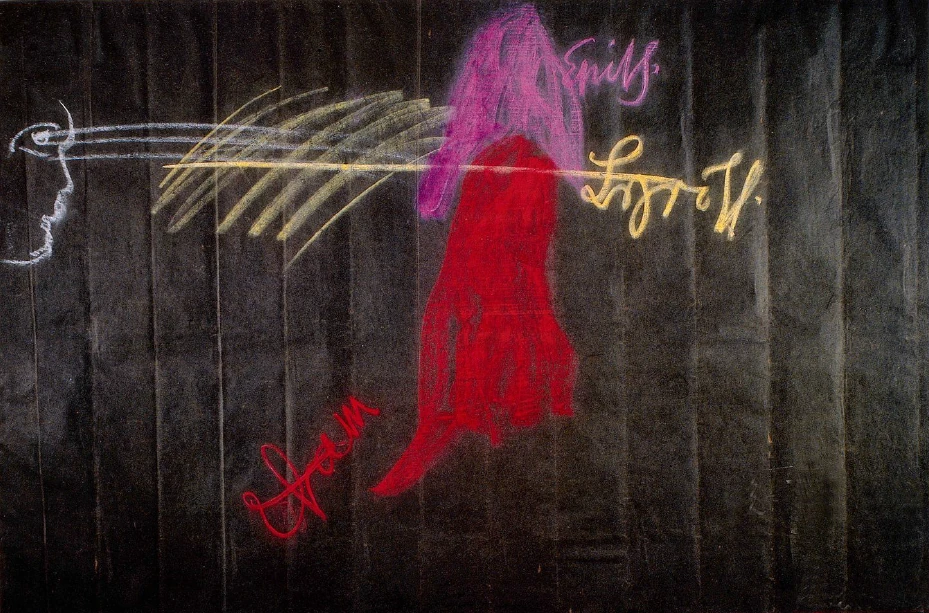

One might say: Here we have the fields of earthly existence: out of the clouds descends the divine Muse of epic art; out of earthly depths there rise, like vapor and smoke, the Dionysian, chthonic divine-spiritual powers, working their way upward through men's wills. We have to penetrate earth regions to see how the dramatic element rises like a volcano, and the epic element sinks down from above, like a blessing of rain. And it is right here on this same plane with ourselves that the cosmic element is enticed and made gay, joyous, full of laughter, through nymphs and fire spirits; right here that the messengers of the upper gods cooperate with the lower: right here in the middle region that man becomes lyrical. Now man does not feel the dramatic element rising up from below, nor the epic element sinking down from above; he experiences the lyrical element living on the same plane as himself: a delicate, sensitive, spiritual element, which does not rain down upon forests nor erupt like volcanoes, splitting trees, but, rather, rustles in leaves, expresses joy through blossoms, wafts gently in wind. In whatever on our own plane lets us divine the spiritual in matter, stretching hearts, pleasantly stimulating breath, merging our souls with outer nature, as symbol of the soul-spiritual world—in all this there lives and weaves a lyrical element which looks up, with happy countenance, to the upper gods, and down, with saddened countenance, to the gods of the underworld. The lyrical can tense up into the dramatic-lyrical or quiet itself down into the epic-lyrical. For the hallmark of the lyrical, whatever its form, is this: man experiences what lives and weaves in the far reaches of the earth with his middle nature, his feeling nature.

You see, if we really enter the spirituality of world phenomena, we gradually transform dead abstract concepts into a living, colorful, form-bearing weaving and being. Because what surrounds us lives in the artistic, mere intellectual activity can, almost unnoticed, be transformed into artistic activity. That is why we constantly feel a need to enliven impertinently abstract conceptual definitions—physical body, ether body, astral body, all such concepts, these impertinently rigid, philistine and horribly scientific formulations—into artistic color and form. This is an inner, not merely outer, need of Anthroposophy.

Therefore the hope may be expressed that all mankind will extricate itself from naturalism, drowned as it is in philistinism and pedantry through everything abstract, theoretical, merely scientific, practical without being really practical. Man needs a new impetus. Without this impulse, this swing, Anthroposophy cannot thrive. In an inartistic atmosphere it goes short of breath; only in an artistic element can it breathe freely. Rightly understood, it will lead over to the genuinely artistic without losing any of its cognitional character.

Dritter Vortrag

Gestern versuchte ich zu zeigen, wie anthroposophische Anschauung der Welt dazu führen muß, Künstlerisches wiederum in intensiverer Weise in die Zivilisation der Menschheit aufzunehmen, als dies unter dem Einflusse des Materialismus oder des Naturalismus, wie er sich im Künstlerischen zum Ausdrucke bringt, geschehen kann. Ich habe versucht zu zeigen, wie, wenn ich mich so ausdrükken darf, der anthroposophische Blick die Erzeugnisse der Architektur, die architektonische Form empfindet, und wie eine Kunst, die man heute eigentlich gar nicht als solche empfindet, bei der man lächelt, wenn man von ihr als Kunst spricht, wie die Bekleidungskunst empfunden wird. Dann habe ich noch aufmerksam darauf gemacht, wie der Mensch selbst in seiner Gestaltung künstlerisch erfaßt werden kann, indem ich darauf hingewiesen habe, wie das menschliche Haupt kosmisch bedingt ist und dadurch auf den ganzen Menschen in seiner Art hinweist.

Versuchen wir noch einmal, wichtige Momente dieser dreifach künstlerischen Anschauung der Welt vor uns hinzustellen. Wenn wir auf die architektonischen Formen sehen, so müssen wir in ihnen im Sinne der gestrigen Ausführungen etwas erblicken, was die Menschenseele gewissermaßen erwartet, wenn sie in irgendeiner Weise, insbesondere durch den Tod, den physischen Leib verläßt. Sie ist, so sagte ich, während des physischen Erdenlebens gewöhnt, durch den physischen Leib in räumliche Beziehung zur Umgebung zu treten. Sie erlebt die Raumesformen, aber diese Raumesformen sind eigentlich nur Formen der äußeren physischen Welt. Indem nun die Menschenseele zum Beispiel mit dem Tode die physische Welt verläßt, sucht sie gewissermaßen dem Raum ihre eigene Form aufzudrücken. Sie sucht jene Linien, jene Flächen, überhaupt alle jene Formen, durch die sie aus dem Raume herauswachsen und in die geistige Welt hineinwachsen kann. Und dies sind im wesentlichen die architektonischen Formen, insofern die architektonischen Formen als künstlerische in Betracht kommen, so daß wir eigentlich immer blicken müssen auf das Verlassen des menschlichen Leibes durch die Seele und ihre Bedürfnisse nach ihrem Verlassen in bezug auf den Raum, wenn wir das eigentlich Künstlerische der Architektur verstehen wollen.

Um das eigentlich Künstlerische der Bekleidung zu verstehen, habe ich auf die Bekleidungsireudigkeit primitiver Völker hingewiesen, die noch wenigstens eine allgemeine Empfindung davon haben, daß sie aus der geistigen in die physische Welt heruntergestiegen sind, in den physischen Leib untergetaucht sind, aber sich sagen als Seele: In diesem physischen Leibe finden wir etwas anderes als Umhüllung, als wir empfinden können gemäß unserem Aufenthalte in der geistigen Welt. - Da entsteht das instinktive, empfindungsgemäße Bedürfnis, in solchen Farben und in solchen, wenn ich mich so ausdrücken darf, Schnitten eine Umhüllung zu suchen, die der Erinnerung aus dem vorirdischen Dasein entspricht. Bei primitiven Völkern sehen wir also in der Bekleidung gewissermaßen die ungeschickte Formung, ungeschickte Gestaltung des astralischen Menschenwesens, das der Mensch an sich gehabt hat, bevor er ins irdische Dasein heruntergestiegen ist. So sehen wir gewissermaßen in der Architektur immer einen Bezug auf das, was die Menschenseele erstrebt, wenn sie den physischen Körper verläßt. Wir sehen in der Bekleidungskunst, soweit diese als Kunst empfunden wird, dasjenige, was die menschliche Seele erstrebt, nachdem sie aus der geistigen Welt in die physische untertaucht.

Wenn man dann so recht empfindet, was ich gestern zuletzt dargestellt habe, wie der Mensch in seiner Hauptesbildung ist, die eine Metamorphose seiner Leibesbildung - außer dem Haupte aus dem vorigen Erdenleben ist, wenn man empfindet, wie das eigentliche Ergebnis dessen, was sozusagen in der Himmelsheimat, in der geistigen Heimat durch die Wesen der höheren Hierarchien aus dem Kräftezusammenhang des vorigen Erdenlebens gemacht worden ist, dann hat man die mannigfaltigste Umwandelung des menschlichen Hauptes, den oberen Teil des menschlichen Hauptes sich zum Verständnis gebracht. Wenn man dagegen alles das, was dem Mittelhaupte angehört, Nasenbildung, untere Augenbildung, richtig versteht, so hat man dasjenige, was aus der geistigen Welt in der Formung des Hauptes herüberkommt, schon angepaßt der Brustbildung des Menschen. Die Form der Nase steht in Beziehung zur Atmung, also zu dem, was eigentlich dem Brustmenschen angehört. Und wenn wir den unteren Teil des Hauptes, Mundbildung, Kinnbildung richtig verstehen, so haben wir schon auch in dem Haupte einen Hinweis auf die Anpassung ans Irdische. So kann man aber den ganzen Menschen verstehen. Man kann in jeder Wölbung des Oberhauptes, im Vorspringen oder Zurücktreten der unteren Schädel-, das heißt der Gesichtspartien, in alledem fühlen, wie in der Formung das übersinnliche Menschenwesen sich unmittelbar für das Auge darlebt. Und man kann dann jenes intime Verhältnis fühlen, welches das menschliche Oberhaupt, die Wölbung überhaupt, zu den Himmeln hat, dasjenige, welches die mittlere Partie des Gesichtes zu dem Umkreis der Erde hat, gewissermaßen zu alledem, was die Erde als Luft und als Ätherbildung umkreist, und man kann empfinden, wie in der Mund- und Kinnbildung, die einen inneren Bezug zu dem ganzen Gliedmaßensystem des Menschen haben, zum Verdauungssystem, schon das an die Erde Gefesseltsein des Menschen sich ausdrückt. Man kann so rein künstlerisch den ganzen Menschen verstehen und stellt ihn als einen Abdruck des Geistigen in die unmittelbare Gegenwart hinein.

So kann man sagen: In der Plastik, in der Bildhauerkunst schaut man den Menschen geistig an, wie er in die Gegenwart hineingestellt ist, während die Architektur auf das Verlassen des Leibes durch die Seele hinweist und die Bekleidungskunst auf das Hineinziehen der Seele in den Leib. - Es weist gewissermaßen die Bekleidungskunst auf ein Vorzeitliches in bezug auf das Erdenleben, die Architektur auf ein Nachzeitliches in bezug auf das Erdenleben. Daher geht die Architektur, wie ich gestern ausgeführt habe, von Grabbauten aus. Dagegen die Plastik weist auf die Art und Weise, wie der Mensch in seiner Erdenform unmittelbar am Geistigen teilnimmt, wie er das Irdisch-Naturalistische fortwährend überwindet, wie er in jeder seiner einzelnen Formen und in seiner ganzen Gestaltung der Ausdruck des Geistigen ist. Damit sind aber diejenigen Künste angeschaut, welche etwas mit Raumesformen zu tun haben, welche also hinweisen müssen auf die Verteilung des Verhältnisses der menschlichen Seele zur Welt durch den physischen Raumesleib. Steigen wir noch um eine Stufe näher in das Raumlose herab, dann kommen wir von der Plastik, von der Bildhauerei in die Malerei hinein. Die Malerei wird nur richtig empfunden, wenn man mit dem Material der Malerei rechnen kann. Heute im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitalter hat die Malerei im gewissen Sinne gerade am klarsten, am stärksten den Charakter angenommen, der ins Naturalistische hineinführt. Das zeigt sich am allermeisten dadurch, daß ein tieferes Verständnis für das Farbige eigentlich in der Malerei verlorengegangen ist und das malerische Verständnis in der neueren Zeit so geworden ist, daß es, ich möchte sagen eigentlich ein verfälschtes plastisches Verständnis ist. Wir möchten heute den plastisch, den bildhauerisch empfundenen Menschen auf die Leinwand malen. Dazu ist auch die Raumesperspektive gekommen, die eigentlich erst im fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum heraufgekommen ist, die durch die perspektivische Linie ausdrückt, irgend etwas ist hinten, etwas anderes ist vorne, das heißt sie will auf die Leinwand das räumlich Gestaltete zaubern. Damit wird von vornherein das erste, was zum Material des Malers gehört, verleugnet, denn der Maler schafft nicht im Raume, der Maler schafft auf der Fläche, und es ist eigentlich ein Unsinn, räumlich empfinden zu wollen, wenn man als erstes in seinem Material die Fläche hat.

Nun glauben Sie durchaus nicht, daß ich in irgendeiner phantastischen Weise mich gegen das räumliche Empfinden wende, denn in Raumesperspektive [etwas] auf die Fläche hinzaubern, das war notwendig in der Entwickelung der Menschheit. Das ist selbstverständlich, daß das einmal heraufgekommen ist. Aber es muß auch wiederum überwunden werden. Nicht als ob wir in der Zukunft die Perspektive nicht verstehen sollten. Wir müssen sie verstehen, aber wir müssen auch wiederum zur Farbperspektive zurückkehren können, Farbperspektive wieder haben können. Dazu wird freilich nicht nur ein theoretisches Verständnis notwendig sein, denn aus keinerlei Art von theoretischem Verstehen kommt eigentlich der Impuls zum künstlerischen Schaffen, sondern da muß schon etwas Kräftigeres, etwas Elementareres wirken als nur ein theoretisches Verstehen. Das kann aber auch sein. Und dazu möchte ich Ihnen erstens nahelegen, wiederum einmal dasjenige anzuschauen, was ich über die Farbenwelt hier einmal gesagt habe, und was dann Albert Steffen in so wunderbarer Weise in seiner Art wiedergegeben hat, so daß die Wiedergabe viel besser zu lesen ist als das, was ursprünglich hier gegeben worden ist. Das kann im «Goetheanum» nachgelesen werden. Nun, das ist das erste. Das andere ist aber, daß ich einmal folgende Fragen vor Ihnen behandeln möchte. Wir sehen draußen in der Natur Farben. An den Dingen sehen wir Farben, an den Dingen, die wir zählen, die wir abwägen mit der Waage, die wir messen, kurz, die wir physikalisch behandeln, an denen sehen wir Farben. Aber die Farbe, das müßte den Anthroposophen nach und nach ganz klar geworden sein, ist eigentlich ein Geistiges. Nun sehen wir sogar an Mineralien, das heißt an denjenigen Wesen der Natur, die zunächst nicht geistig sind, so wie sie uns entgegentreten, Farben. Die Physik hat sich das in der neueren Zeit immer einfacher und einfacher gemacht. Sie sagt: Nun ja, die Farben, die können nicht an dem Tot-Stofflichen sein, denn die Farben sind etwas Geistiges. Also sind sie nur in der Seele darinnen, und draußen ist erst recht etwas Tot-Stoffliches, da vibrieren stoffliche Atome. Die Atome tun dann ihre Wirkungen auf das Auge, auf den Nerv oder auf noch etwas anderes, was man dann unbestimmt läßt, und dann leben in der Seele die Farben auf. — Das ist nur eine Verlegenheitserklärung.

Damit uns die Sache ganz klar wird, oder ich meine, damit sie an einem Punkt erscheint, wo sie wenigstens klar werden kann, betrachten wir einmal die farbige tote Welt, die farbige mineralische Welt. Wir sehen, wie gesagt, die Farben an dem rein Physikalischen, an dem rein Physischen, das wir zählen, das wir messen, das wir mit der Waage seinem Gewicht nach bestimmen können. Daran sehen wir die Farbe. Aber alles das, was wir mit der Physik an den Dingen wahrnehmen, das gibt keine Farbe. Sie können noch so viel herumrechnen, herumbestimmen mit Zahl, Maß und Gewicht, mit denen es der Physiker zu tun hat, Sie kommen nicht an die Farbe heran. Deshalb brauchte auch der Physiker das Auskunftsmittel: Farben sind nur in der Seele.

Nun möchte ich mich durch ein Bild erklären, das ich in der folgenden Weise gestalten möchte. Denken Sie sich einmal, ich habe in meiner linken Hand ein rotes Blatt, in meiner rechten Hand ein — sagen wir grünes Blatt, und ich mache vor Ihnen mit dem roten Blatte und mit dem grünen Blatte bestimmte Bewegungen. Ich decke einmal das Rot mit Grün, das andere Mal das Grün mit Rot zu. Ich mache solche Bewegungen abwechselnd hin und her. Und damit die Bewegung etwas charakteristischer ist, mache ich es so, ich bewege das Grün so herauf, das Rot so herab, so daß ich außerdem die Bewegung so mache. Sagen wir, das habe ich heute vor Ihnen ausgeführt. Jetzt lassen wir drei Wochen vergehen, und nach drei Wochen bringe ich nun nicht ein grünes und ein rotes Blatt hierher, sondern zwei weiße Blätter, und ich mache dieselben Bewegungen damit. Nun wird Ihnen einfallen, der hat, trotzdem er jetzt weiße Blätter hat, vor drei Wochen bestimmte Wahrnehmungseindrücke hervorgerufen, die mit einem roten und mit einem grünen Blatt hervorgerufen waren. Und nehmen wir jetzt an, ich will aus Höflichkeit sagen, daß alle von Ihnen eine so lebhafte Phantasie haben, daß, trotzdem ich nun die weißen Blätter bewege, Sie durch Ihre Phantasie, durch Ihre erinnernde Phantasie dasselbe Phänomen vor sich sehen, das Sie vor drei Wochen mit dem roten und dem grünen Blatt gesehen haben. Sie denken gar nicht daran, so lebhaft ist Ihre Phantasie, daß das nur weiße Blätter sind, sondern, weil ich dieselben Bewegungen mache, sehen Sie dieselben Farbenharmonisierungen, die ich vor drei Wochen mit dem roten und mit dem grünen Blatt hervorgerufen habe. Sie haben das vor sich, was vor drei Wochen vor Ihnen war, trotzdem ich nicht wiederum ein rotes und ein grünes Blatt habe. Ich habe gar keine Farben vor Ihnen zu entwickeln, aber ich führe dieselben Gesten, dieselben Bewegungen aus, die ich vor drei Wochen ausgeführt habe.

Sehen Sie, etwas Ähnliches liegt draußen in der Natur vor, wenn Sie, sagen wir einen grünen Edelstein sehen. Nur ist der grüne Edelstein nicht angewiesen auf Ihre seelische Phantasie, sondern er appelliert an die in Ihrem Auge konzentrierte Phantasie, denn dieses Auge, dieses menschliche Auge ist mit seinen Blut- und Nervensträngen aus Phantasie aufgebaut, es ist das Ergebnis wirksamer Phantasie. Und indem Sie den grünen Edelstein sehen, können Ste ihn, weil Ihr Auge ein phantasievolles Organ ist, gar nicht anders sehen als so, wie er vor unermeßlich langer Zeit geistig aus der grünen Farbe aus der geistigen Welt heraus aufgebaut ist. In demselben Momente, wo der grüne Edelstein Ihnen entgegentritt, versetzen Sie Ihr Auge zurück in weit zurückliegende Zeiten, und das Grüne erscheint Ihnen deshalb, weil damals göttlich-geistige Wesenheiten diese Substanz durch die Grün-Farbe im Geistigen aus der geistigen Welt heraus erschaffen haben. In dem Augenblick, wo Sie grün, rot, blau, gelb an Edelsteinen sehen, schauen Sie zurück in unendlich ferne Vergangenheiten. Wir sehen nämlich gar nicht, wenn wir Farben sehen, bloß das Gleichzeitige, wir sehen, wenn wir Farben sehen, in weite Zeitperspektiven zurück. Wir können nämlich einen gefärbten Edelstein gar nicht bloß gegenwärtig sehen, ebensowenig wie wir, wenn wir unten am Fuß eines Berges stehen, meinetwillen oben eine Ruine, die am Gipfel ist, in unserer unmittelbaren Nähe sehen können. Weil wir eben von dem ganzen Faktum entfernt sind, müssen wir sie perspektivisch sehen.

Wenn nun ein Topas uns entgegentritt, können wir ihn nicht bloß im gegenwärtigen Augenblicke sehen, wir müssen hineinschauen in eine Zeitperspektive. Und indem wir, veranlaßt durch den Edelstein, in die Zeitperspektive hineinsehen, sehen wir auf den Urgrund des Erdenschaffens vor der lemurischen Epoche unserer Erdenentwickelung hin und sehen aus dem Geistigen heraus den Edelstein erschaffen, sehen ihn dadurch farbig. Da tut unsere Physik etwas ungeheuerlich Absurdes. Sie setzt diese Welt vor uns hin und dahinter schwingende Atome, welche die Farben in uns bewirken sollen, während es die vor unendlich langen Zeiten schaffenden göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten sind, die in den Farben der Gesteine aufleben, die eine lebendige Erinnerung an ihr vorzeitliches Schaffen erregen. Wenn wir die leblose Natur farbig sehen, so verwirklichen wir im Verkehr mit der leblosen Natur eine Erinnerung an ungeheuer weit zurückliegende Zeiten. Und jedesmal, wenn im Frühling vor uns der grüne Pflanzenteppich der Erde auftaucht, so schaut derjenige, der dieses Auftauchen des Grünen in der Natur verstehen kann, nicht bloß Gegenwart, er schaut zurück in jene Zeit, da während eines alten Sonnendaseins aus dem Geistigen heraus die Pflanzenwelt geschaffen worden ist und dieses Herausschaffen aus dem Geistigen in Grünheit geschah. Sie sehen, richtig sehen wir das Farbige in der Natur, wenn uns das Farbige anregt, vorzeitliches Götterschaffen in dieser Natur zu schauen.

Dazu brauchen wir aber zunächst künstlerisch die Möglichkeit, mit der Farbe zu leben. Also zum Beispiel, wie ich öfter angedeutet habe und wie Sie es in den betreffenden Vorträgen im «Goetheanum» nachlesen können, braucht man die Möglichkeit, die Fläche als solche zu empfinden: wenn ich die Fläche mit Blau bestreiche, das Sich-Entfernen nach rückwärts, wenn ich sie mit Rot oder Gelb bestreiche, das Sich-Nähern nach vorwärts. Denn Farbenperspektive, nicht eine Linienperspektive ist dasjenige, was wir uns wieder erobern müssen: Empfindung der Fläche, des Fernen und des Nahen nicht bloß mit der Linienperspektive, die eigentlich immer durch eine Verfälschung das Plastische auf die Fläche zaubern will, sondern das Farbige auf der Fläche sich intensiv, nicht extensiv fernend und nahend, so daß ich in der Tat gelb-rot male, wenn ich andeuten will, etwas ist aggressiv, etwas ist auf der Fläche, was mir gewissermaßen entgegenspringen will. Ist etwas in sich ruhig, fernt es sich von mir, geht es nach rückwärts - ich male es blau-violett. Intensive Farbenperspektive! Studieren Sie die alten Maler, Sie werden überall finden, es war selbst bei den Malern der frühen Renaissancezeit noch durchaus ein Empfinden für diese Farbenperspektive vorhanden. Sie ist aber überall vorhanden in der VorRenaissancezeit, denn erst mit dem fünften nachatlantischen Zeitraum ist die Linienperspektive an die Stelle der Farbenperspektive, der intensiven Perspektive getreten.

Damit gewinnt die Malerei aber ihre Beziehung zum Geistigen. Es ist schon merkwürdig, sehen Sie, heute denken die Menschen hauptsächlich nach, wie können wir den Raum noch räumlicher machen, wenn wir über den Raum hinauskommen wollen? Und sie verwenden in dieser materialistischen Weise eine vierte Dimension. Aber so ist diese vierte Dimension gar nicht vorhanden, sondern sie ist so vorhanden, daß sie die dritte vernichtet, wie die Schulden das Vermögen vernichten. Sobald man aus dem dreidimensionalen Raum herauskommt, kommt man nicht in einen vierdimensionalen Raum, oder man kommt meinetwillen in einen vierten dimensionalen Raum, aber der ist zweidimensional, weil die vierte Dimension die dritte vernichtet und nur zwei übrig bleiben als reale, und alles ist, wenn wir uns von den drei Dimensionen des Physischen zum Ätherischen erheben, nach den zwei Dimensionen orientiert. Wir verstehen das Ätherische nur, wenn wir es nach zwei Dimensionen orientiert denken. Sie werden sagen, aber ich gehe doch auch im Ätherischen von hier bis hierher, das heißt nach drei Dimensionen. Nur hat die dritte Dimension für das Ätherische keine Bedeutung, sondern Bedeutung haben nur immer die zwei Dimensionen. Die dritte Dimension drückt sich immer durch das nuancierte Rot, Gelb, Blau, Violett aus, wie ich es auf die Fläche bringe, ganz gleichgültig, ob ich die Fläche hier habe oder hier, da ändert sich im Ätherischen nicht die dritte Dimension, sondern die Farbe ändert sich, und es ist gleichgültig, wo ich die Fläche aufstelle, ich muß nur die Farben entsprechend ändern. Da gewinnt man die Möglichkeit, mit der Farbe zu leben, mit der Farbe in zwei Dimensionen zu leben. Damit aber steigt man auf von den räumlichen Künsten zu den Künsten, die wie die Malerei nun zweidimensional sind, und überwindet das bloße Räumliche. Alles was in uns selber Gefühl ist, hat keine Beziehung zu den drei Raumdimensionen, nur der Wille hat zu ihnen Beziehung, das Gefühl nicht, das ist immer in zwei Dimensionen beschlossen. Daher finden wir, [daß] dasjenige, was gefühlsmäßig in uns ist, der Möglichkeit nach wiederzugeben ist in dem, was die Malerei in zwei Dimensionen darleben kann, wenn wir die zwei Dimensionen wirklich richtig verstehen.

Sie sehen, man muß sich aus dem dreidimensionalen Materiellen herauswinden, wenn man sich von der Architektur, der Bekleidungskunst und der Plastik zu dem Malerischen herauf entwickeln will. Damit hat man in der Malerei eine Kunst, von der man sagen kann, der Mensch kann das Malerische innerlich seelisch erleben, denn wenn er malerisch schafft oder malerisch genießt, so ist es zunächst innerlich seelisch erlebt. Aber er erlebt eigentlich das Äußerliche. Er erlebt es in Farbenperspektive. Es ist gar kein Unterschied mehr zwischen innen und außen. Man kann nicht sagen, wie man bei der Architektur sagen muß, die Seele möchte die Formen schaffen, die sie braucht, wenn sie in den Körper hineinschaut. In der Plastik möchte die Seele Formen gestalten in dem bildhauerisch gestalteten Menschen, wo der Mensch sich in einer ihm naturgemäßen Weise sinnvoll in den Raum hineinstellt in der Gegenwart. In der Malerei kommt das alles nicht in Betracht. In der Malerei hat es eigentlich gar keinen Sinn, davon zu sprechen, irgend etwas ist drinnen oder draußen, oder die Seele ist innen und außen. Die Seele ist immerfort im Geistigen, wenn sie in der Farbe lebt. Es ist sozusagen das freie Bewegen der Seele im Kosmos, was in der Malerei erlebt wird. Es kommt nicht in Betracht, ob wir das Bild innerlich erleben, ob wir es außen sehen, wenn wir es — abgesehen von der Unvollkommenheit der äußeren Farbmittel - farbig sehen.

Dagegen kommen wir völlig in dasjenige hinein, was die Seele als Geistiges, als Geistig-Seelisches erlebt, wenn wir ins Musikalische kommen. Da müssen wir aus dem Raum vollständig heraus. Das Musikalische ist linienhaft, eindimensional. Es wird auch eindimensional in der Zeitenlinie erlebt. Aber es wird so erlebt, daß der Mensch dabei zugleich die Welt als seine Welt erlebt. Die Seele will weder etwas geltend machen, was sie braucht, wenn sie untertaucht ins Physische oder wenn sie das Physische verläßt, die Seele will dasjenige erleben im Musikalischen, was in ihr jetzt auf Erden seelisch-geistig lebt und vibriert. Studiert man die Geheimnisse der Musik, so kommt man darauf, ich habe das schon einmal hier ausgesprochen, was eigentlich die Griechen, die sich auf solche Dinge wunderbar verstanden, mit der Leier des Apollo meinten. Dasjenige, was musikalisch erlebt wird, ist die verborgene, aber dem Menschen gerade eigene Anpassung an die inneren harmonisch-melodischen Verhältnisse des Weltendaseins, aus denen er herausgestaltet ist. Wunderbare Saiten im Grunde genommen, die nur eine metamorphosierte Wirksamkeit haben, sind seine Nervenstränge, die von dem Rückenmark auslaufen. Das ist die Leier des Apollo, dieses Rückenmark, oben im Gehirn endigend, die einzelnen Nervenstränge nach dem ganzen Körper ausdehnend. Auf diesen Nervensträngen wird der seelisch-geistige Mensch gespielt innerhalb der irdischen Welt. Das vollkommenste Instrument dieser Welt ist der Mensch selber, und ein Musikinstrument außen zaubert die Töne in dem Maße für den Menschen als künstlerische hervor, wie der Mensch in dem Erklingen der Saiten eines neuen Instrumentes zum Beispiel etwas fühlt, was mit seiner eigenen, durch Nervenstränge und Blutbahnen erfolgten Konstitution, seinem Aufbau, zusammenhängt. Der Mensch, insofern er ein Nervenmensch ist, ist innerlich aus Musik aufgebaut, und er empfindet die Musik künstlerisch, insofern irgend etwas, was musikalisch auftritt, mit dem Geheimnis seines eigenen musikalischen Aufbaues zusammenstimmt.

Da also appelliert der Mensch an sein auf der Erde lebendes Seelisch-Geistiges, wenn er sich dem Musikalischen hingibt. In demselben Maße, in dem anthroposophische Anschauung die Geheimnisse der inneren geistig-seelischen Menschennatur entdeckt, werden sie gerade auf das Musikalische befruchtend wirken können, nicht theoretisch, sondern auf das musikalische Schaffen. Denn bedenken Sie, daß es wirklich nicht ein Theoretisieren ist, wenn ich sage: Schauen wir hinaus auf die leblose stoffliche Welt. Indem wir sie farbig sehen, ist das Farbigsehen die kosmische Erinnerung an vorzeitlich wirkende Götter. Lernen wir verstehen durch richtiges anthroposophisches Anschauen, wie in den Edelsteinen, in den farbigen äußeren Gegenständen, überhaupt durch die Farben, sich die Götter in ihrem Urschaffen in Erinnerung rufen, werden wir gewahr, daß die Dinge deshalb farbig sind, weil Götter sich durch die Dinge aussprechen, dann ruft das jenen Enthusiasmus hervor, der aus dem Erleben in dem Geistigen hervorgeht. Das ist kein Theoretisieren, das ist etwas, was die Seele unmittelbar mit innerer Kraft durchziehen kann. Nicht ein Theoretisieren über die Kunst geht daraus hervor. Künstlerisches Schaffen und künstlerisches Genießen selber kann dadurch angeregt werden. So ist die wahre Kunst überall ein Beziehungsuchen des Menschen zum Geistigen, sei es zu dem Geistigen, das er erhofft, wenn er mit der Seele aus dem Leibe geht; sei es mit dem Geistigen, das er sich erinnernd bewahren möchte, wenn er in den Leib untertaucht; sei es zu dem Geistigen, mit dem er sich verwandt fühlt, da er sich nicht verwandt fühlt mit dem bloßen Natürlichen seiner Umgebung; sei es, daß er sich fühlt in dem Geistigen, ich möchte sagen mehr in der Welt im Farbigen, wo das Innen und Außen aufhören, wo die Seele gewissermaßen durch den Kosmos schwimmend, schwebend sich bewegt, im Farbigen ihr eigenes Leben im Kosmos fühlt, wo sie überall sein kann durch das Farbige. Oder es fühlt die Seele auch noch innerhalb des Irdischen ihre Verwandtschaft mit dem Kosmisch-SeelischGeistigen wie im Musikalischen.

Nun kommen wir herauf zum Dichterischen. Manches, was ich in bezug auf alte Zeiten dichterischer Empfindungen, wo das Dichterische noch ganz künstlerisch war, gesagt habe, kann uns darauf aufmerksam machen, wie dieses Dichterische empfunden worden ist, als man noch lebendige Beziehungen zu der geistig-seelischen Welt hatte. Ich habe schon gestern gesagt, darzustellen, wie Hinz und Kunz sich auf dem Marktplatze von Klein-Griebersdorf bewegen, wäre für wirklich künstlerische Zeiten nicht etwas Vernünftiges gewesen, denn da geht man nach dem Marktplatz von KleinGriebersdorf und schaut sich Hinz und Kunz an, und ihre Bewegungen, ihre Gespräche sind noch immer reicher als diejenigen, die man dann beschreiben kann. Bei den Griechen der eigentlichen griechischen Künstlerzeit wäre das ganz absurd erschienen, so die Leute vom Marktplatz und in ihren Häusern zu schildern. Man hat aus dem Naturalismus heraus ein merkwürdiges Streben gehabt, auf dem Theater ganz und gar, sogar in der Szenerie nur Tafel 3 %

Naturalistisches nachzubilden. Gerade so wenig, wie es eigentlich Malerei wäre, wenn man nicht auf der Fläche malte, sondern in den Raum hinein die Farbe in irgendeiner Weise gestalten wollte, so ist es auch nicht Bühnenkunst, wenn man nicht die Bühnenmittel, die ganz bestimmte, gegebene sind, wirklich künstlerisch versteht. Denken Sie, wenn man wirklich naturalistisch sein wollte, müßte man eigentlich nicht aus der Bühne ein solches Zimmer machen und da den Zuschauer haben. Ein solches Zimmer könnte man nicht machen, denn solche Zimmer gibt es nicht, man würde doch im Winter erfrieren darinnen. Man macht Zimmer, die von allen vier Seiten abgeschlossen sind. Wollte man ganz naturalistisch spielen, müßte man die Bühne auch zumachen und dahinter spielen. Ich weiß nicht, wie viele Leute dann Theaterbillets kaufen würden, aber das wäre mit Berücksichtigung von allem Naturalistisch-Realen die Bühnenkunst, wenn man auch die vierte Wand hätte. Das ist natürlich etwas extrem gesprochen, aber es ist durchaus richtig.

Nun brauche ich Sie nur auf eines hinzuweisen, auf das ich oftmals hingewiesen habe. Homer beginnt seine Iliade damit, daß er sagt: «Singe, o Muse, vom Zorn mir des Peleiden Achilleus.» - Das ist keine Phrase, das ist so, daß Homer tatsächlich das positive Erlebnis hatte, daß er sich zu überirdischer göttlich-geistiger Wesenheit zu erheben hat, die sich seines Leibes bedient, um Episches künstlerisch zu gestalten. Episches bedeutet die oberen Götter, die als weiblich empfunden wurden, weil sie die Befruchtenden waren, die eben als weiblich, als Musen empfunden wurden. Er hat die oberen Götter aufzusuchen, sich mit seiner Menschenwesenheit den oberen Göttern zur Verfügung zu stellen, um dadurch das Gedankliche des Kosmos in den Ereignissen zum Ausdruck bringen zu lassen. Sehen Sie, das ist das Epische, die oberen Götter sprechen lassen, indem man ihnen seinen eigenen Menschen zur Verfügung stellt. Homer beginnt: «Singe, o Muse, vom Manne, dem Vielgereisten.» — Er meint den Odysseus. Es würde ihm gar nicht einfallen, bloß den Leuten etwas vormachen zu wollen, was er selber ausgedacht hat oder selber gesehen hat. Denn warum sollte er denn das? Das kann sich jeder selber machen. Homer will durchaus diesen Homer-Organismus den oberen göttlich-geistigen Wesenheiten zur Verfügung stellen, daß sie ausdrücken, wie sie den Menschenzusammenhang auf der Erde sehen. Daraus entsteht die epische Dichtung.

Und die dramatische Dichtung? Nun, sie ging hervor — wir brauchen nur an die vor-äschyleische Periode zu denken - aus der Darstellung des aus den Tiefen heraufwirkenden Gottes Dionysos. Zuerst ist es die einzige Person des Dionysos, dann der Dionysos und seine Helfer, der Chor, der sich herumgruppiert, um gleichsam ein Reflex zu sein desjenigen, was nicht Menschen tun, sondern was eigentlich die unterirdischen Götter tun, die Willensgötter, die sich der menschlichen Gestalten bedienen, um auf der Bühne nicht Menschenwillen, sondern Götterwillen agieren zu lassen. Erst allmählich mit dem Vergessen des Zusammenhanges des Menschen mit der geistigen Welt wurde auf der Bühne aus dem Götterwirken durch die Menschen reines Menschenwirken. Dieser Prozeß hat sich noch in Griechenland vollzogen zwischen Äschylos, wo wir noch überall die göttlichen Impulse durch die Menschen durchdringen sehen, bis zu Euripides, wo schon die Menschen auftreten als Menschen, aber doch noch immer mit überirdischen Impulsen, möchte man sagen, denn das eigentlich Naturalistische war erst der neueren Zeit möglich.

Aber der Mensch muß den Weg zurück zum Geistigen auch in der Dichtung wiederum finden, so daß wir sagen können: Das Epische wendet sich an die oberen Götter. Das Dramatische wendet sich an die unteren Götter, das wirkliche Drama sieht die unter der Erde liegende Götterwelt auf die Erde heraufsteigen. Der Mensch kann sich zum Werkzeug für das Agieren dieser unteren Götterwelt machen. Da haben wir, wenn wir gewissermaßen als Mensch in die Welt hinausschauen, in der Kunst durchaus dasjenige, was, ich möchte sagen unmittelbar draußen naturalistisch ist.

Dagegen haben wir im Dramatischen aufsteigend die untere geistige Welt. Wir haben im Epischen sich herabsenkend eine obere geistige Welt. Die Muse, die heruntersteigt, um durch das Haupt des Menschen sich des Menschen zu bedienen und als Muse zu sagen, was die Menschen auf Erden vollbringen oder was überhaupt im Weltenall vollbracht wird, ist episch. Heraufsteigen aus den Tiefen der Welt, sich der menschlichen Leiber bedienen, um den Willen agieren zu lassen, der unterirdischer Götterwille ist, das ist Dramatik.

Man möchte sagen: Haben wir die Fluren des Erdendaseins, so haben wir wie aus den Wolken heruntersteigend die göttliche Muse der epischen Kunst; wie aus den Tiefen der Erde heraufsteigend, heraufqualmend, heraufrauchend, die dionysisch-unterirdischen göttlich-geistigen Mächte, die willensmäßig durch die Menschen nach oben wirken. Aber überall müssen wir durch die Erdenflur hindurchsehen, wie gewissermaßen vulkaniisch das Dramatische heraufsteigt, wie sich mit segnendem Regen von oben nach unten das Epische senkt. Und was auf gleichem Niveau mit uns sich vollzieht, wo wir gewissermaßen die äußersten Boten der oberen Götter empfindend zusammenwirken sehen mit den unteren Göttern auf gleichem Niveau mit uns, wo gewissermaßen Kosmisches — aber nicht theoretisch philiströs empfunden, sondern in aller Gestaltlichkeit empfunden — von unten sich reizen läßt, froh machen läßt, lachen machen läßt, jauchzen machen läßt durch nymphisches Geistig-Feuriges von oben, da in der Mitte wird der Mensch lyrisch. Er empfindet nicht das von unten nach oben steigende Dramatische, nicht das von oben nach unten sich senkende Epische, sondern das mit ihm in gleichem Niveau lebende Lyrische, das feinsinnig Geistige, das nicht zum Walde herabregnet, auch nicht von unten in dem Vulkan heraufbricht und die Bäume spaltet, sondern das, was in den Blättern säuselt, was in den Blüten erfreut, was im Winde hinweht. All das, was uns auf gleichem Niveau im Materiellen das Geistige ahnen läßt, so daß unser Herz schwellt, unser Atem freudig erregt wird, unsere ganze Seele aufgeht in dasjenige, wofür die äußeren Naturerscheinungen als Zeichen stehen eines Geistig-Seelischen, das mit uns auf gleichem Niveau ist — da west und webt das Lyrische, das, man möchte sagen mit einem frohen Antlitz hinaufblickt zu den oberen Göttern; das mit einem etwas getrübten Antlitz hinunterblickt zu den unteren Göttern; das sich ausbilden kann nach der einen Seite, indem es lyrisch ist, zum Dramatisch-Lyrischen; das auf der anderen Seite sich beruhigen kann zum Episch-Lyrischen, welches aber immer ein Lyrisches dadurch ist, daß der Mensch den Umkreis der Erde gewissermaßen mit seinem mittleren Menschen erlebt, seinem Gefühlswesen, in welchem er das mit ihm im Umkreise der Erde Wesende erlebt.

Sehen Sie, man kann eigentlich nicht anders, wenn man wirklich in das Geistige der Welterscheinungen hineinkommt, als allmählich die vertrackt-abstrakten Vorstellungen übergehen zu lassen in lebendiges, farbiges, gestaltiges Weben und Wesen. Ganz unversehens, möchte ich sagen, wird die ideenmäßige Darstellung zur künstlerischen Darstellung, weil dasjenige, was um uns herum ist, im Künstlerischen lebt. Es ist deshalb durchaus immer das Bedürfnis da, aufzuwecken diese impertinent abstrakten Begriffsbestimmungen — physischer Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib, all das, was da begrifflich ideell ist, dieses impertinent geradlinig, dieses impertinent philiströs Definierbare, dieses schauderhaft wissenschaftlich zu Bestimmende -, das abzustufen in die künstlerische Farbe und Form. Das ist ein inneres, nicht bloß ein äußeres Bedürfnis des Anthroposophischen.

Daher darf die Hoffnung ausgesprochen werden, daß die Menschheit wirklich aus dem Naturalismus heraus sich entphilistert, entpedantisiert, entbotokudisiert. Sie steckt im Philistertum, in der Pedanterie, in dem Botokudentum mit dem Abstrakten, mit dem Theoretischen, mit dem bloß Wissenschaftlichen, mit dem sogenannten Praktischen - denn wirklich praktisch ist das ja nicht — tief darinnen und braucht Schwung. Und ehe nicht dieser Schwung da ist, kann eigentlich Anthroposophie nicht recht gedeihen, denn in einem unkünstlerischen Elemente wird sie kurzatmig. Sie kann frei nur atmen in einem künstlerischen Elemente. Wird sie richtig verstanden, wird sie auch zum Künstlerischen führen, ohne daß sie vom Erkenntnismäßigen nur irgend etwas im Geringsten weggibt.

Third Lecture

Yesterday I attempted to show how an anthroposophical view of the world must lead to art being incorporated into human civilization in a more intensive way than is possible under the influence of materialism or naturalism as expressed in art. I tried to show how, if I may express myself thus, the anthroposophical view perceives the products of architecture, the architectural form, and how an art that is not really perceived as such today, that makes one smile when one speaks of it as art, is perceived as the art of clothing. Then I drew attention to how human beings themselves can be understood artistically in their form, by pointing out how the human head is cosmically conditioned and thus points to the whole human being in its nature.

Let us try once again to present the important aspects of this threefold artistic view of the world. When we look at architectural forms, we must see in them, in the sense of yesterday's remarks, something that the human soul expects, in a sense, when it leaves the physical body in some way, especially through death. During physical life on earth, I said, it is accustomed to entering into spatial relationship with its surroundings through the physical body. It experiences spatial forms, but these spatial forms are actually only forms of the outer physical world. When the human soul leaves the physical world, for example through death, it seeks, in a sense, to impose its own form on space. It seeks those lines, those surfaces, indeed all those forms through which it can grow out of space and into the spiritual world. And these are essentially the architectural forms, insofar as architectural forms can be considered artistic, so that we must always look at the soul's departure from the human body and its needs after its departure in relation to space if we want to understand the true artistic nature of architecture.

In order to understand the true artistic nature of clothing, I have pointed to the clothing habits of primitive peoples, who still have at least a general sense that they have descended from the spiritual world into the physical world, that they have immersed themselves in the physical body, but who say to themselves as souls: In this physical body we find something other than a covering, as we can feel according to our stay in the spiritual world. - This gives rise to the instinctive, intuitive need to seek a covering in such colors and, if I may express myself thus, in such cuts that correspond to the memory of pre-earthly existence. In primitive peoples, we see in clothing, as it were, the clumsy shaping, the clumsy design of the astral human being that man had in himself before he descended into earthly existence. Thus, in architecture, we always see, as it were, a reference to what the human soul strives for when it leaves the physical body. In the art of clothing, insofar as it is perceived as art, we see what the human soul strives for after it has descended from the spiritual world into the physical world.

If one then truly feels what I described yesterday, how human beings are in their head formation, which is a metamorphosis of their body formation — except for the head from the previous earthly life, when one feels how the actual result of what has been made, so to speak, in the heavenly home, in the spiritual home, by the beings of the higher hierarchies from the power connection of the previous earthly life, then one has brought to understanding the most manifold transformation of the human head, the upper part of the human head. If, on the other hand, one correctly understands everything that belongs to the middle head, the formation of the nose and the lower eyes, then one has already adapted what comes over from the spiritual world in the formation of the head to the formation of the human chest. The shape of the nose is related to breathing, that is, to what actually belongs to the chest. And if we correctly understand the lower part of the head, the formation of the mouth and chin, then we already have an indication in the head of its adaptation to the earthly. In this way, however, one can understand the whole human being. In every curve of the head, in the protrusion or receding of the lower skull, that is, the facial features, one can feel how the supersensible human being is immediately revealed to the eye in the formation. And then one can feel that intimate relationship which the human head, the curvature in general, has to the heavens, that which the middle part of the face has to the circumference of the earth, to everything that the earth encircles as air and ether formation, so to speak, and one can sense how the formation of the mouth and chin, which have an inner connection to the entire limb system of the human being, to the digestive system, already expresses the human being's bondage to the earth. One can thus understand the whole human being in a purely artistic way and place him as an imprint of the spiritual into the immediate present.

So one can say: in sculpture, in the art of sculpting, one looks at the human being spiritually, as he is placed in the present, while architecture points to the soul leaving the body and the art of clothing points to the soul entering the body. In a sense, the art of clothing points to a pre-earthly life, while architecture points to a post-earthly life. That is why architecture, as I explained yesterday, originates from tomb buildings. In contrast, sculpture points to the way in which human beings in their earthly form participate directly in the spiritual, how they continually overcome the earthly-naturalistic, how they are the expression of the spiritual in each of their individual forms and in their entire configuration. This, however, applies to those arts that have something to do with spatial forms, which must therefore point to the distribution of the relationship of the human soul to the world through the physical spatial body. If we descend one step further into the non-spatial, we move from sculpture to painting. Painting can only be properly appreciated if one can reckon with the material of painting. Today, in the fifth post-Atlantean epoch, painting has, in a certain sense, most clearly and strongly taken on the character that leads into naturalism. This is most evident in the fact that a deeper understanding of color has actually been lost in painting, and that the understanding of painting in recent times has become, I would say, a distorted understanding of sculpture. Today, we want to paint the plastic, sculpturally perceived human being on canvas. In addition to this, spatial perspective has also emerged, which actually only came about in the fifth post-Atlantic period, expressing through the perspective line that something is in the back and something else is in the front, that is, it wants to conjure up the spatially designed on the canvas. This denies from the outset the first thing that belongs to the painter's material, because the painter does not create in space, the painter creates on the surface, and it is actually nonsense to want to perceive spatially when the first thing you have in your material is the surface.

Now, don't think that I am in any way fantastically opposed to spatial perception, because conjuring [something] onto the surface in spatial perspective was necessary in the development of humanity. It is only natural that this should have come about. But it must also be overcome again. Not as if we should not understand perspective in the future. We must understand it, but we must also be able to return to color perspective, to have color perspective again. Of course, this will require more than just a theoretical understanding, because the impulse for artistic creation does not actually come from any kind of theoretical understanding, but something more powerful, something more elementary than just a theoretical understanding must be at work. But that can also be the case. And to this end, I would first like to suggest that you take another look at what I once said here about the world of colors, and what Albert Steffen then reproduced in such a wonderful way in his own style, so that the reproduction is much easier to read than what was originally given here. This can be read in the “Goetheanum.” Well, that is the first thing. The other thing is that I would like to address the following questions with you. We see colors outside in nature. We see colors on things, on things that we count, that we weigh with scales, that we measure, in short, that we treat physically, we see colors on them. But color, as should have become clear to anthroposophists little by little, is actually something spiritual. Now we even see colors in minerals, that is, in those beings of nature that are not spiritual at first glance, as they appear to us. In recent times, physics has made this easier and easier for itself. It says: Well, colors cannot be in dead matter, because colors are something spiritual. So they are only inside the soul, and outside there is only dead matter, where material atoms vibrate. The atoms then have their effect on the eye, on the nerve, or on something else that is left undefined, and then the colors come to life in the soul. — This is only an awkward explanation.

To make the matter completely clear to us, or rather, to bring it to a point where it can at least become clear, let us consider the colored dead world, the colored mineral world. As we have said, we see colors in purely physical things, in purely physical things that we can count, measure, and determine by weight with a scale. That is where we see color. But everything we perceive in things through physics does not give us color. No matter how much you calculate, determine with numbers, measurements, and weights, which physicists deal with, you cannot get to color. That is why physicists also needed a means of obtaining information: colors are only in the soul.

Now I would like to explain myself with an image that I would like to create in the following way. Imagine that I have a red sheet in my left hand and a green sheet in my right hand, and I make certain movements in front of you with the red sheet and the green sheet. I cover the red with green, then the green with red. I make these movements alternately back and forth. And to make the movement a little more characteristic, I move the green up and the red down, so that I also make the movement like this. Let's say I did that in front of you today. Now we let three weeks pass, and after three weeks I bring not a green and a red leaf here, but two white leaves, and I make the same movements with them. Now it will occur to you that, even though he now has white leaves, three weeks ago he evoked certain perceptual impressions that were evoked with a red and a green leaf. And let us now assume, out of politeness, that all of you have such a vivid imagination that, even though I am now moving the white sheets of paper, your imagination, your memory, allows you to see the same phenomenon that you saw three weeks ago with the red and green sheets of paper. Your imagination is so vivid that you do not even think about the fact that these are only white sheets; instead, because I am making the same movements, you see the same color harmonies that I produced three weeks ago with the red and green sheets. You see before you what was before you three weeks ago, even though I do not have a red and a green sheet again. I don't have any colors to develop in front of you, but I perform the same gestures, the same movements that I performed three weeks ago.

You see, something similar exists in nature when you see, say, a green gemstone. Only the green gemstone does not depend on your mental imagination, but appeals to the imagination concentrated in your eye, because this eye, this human eye, is made up of blood and nerve strands of imagination; it is the result of effective imagination. And when you see the green gemstone, because your eye is an imaginative organ, you cannot see it in any other way than how it was spiritually constructed from the green color of the spiritual world an immeasurably long time ago. At the very moment when the green gemstone appears before you, you transport your eye back to times long past, and the green appears to you because divine spiritual beings created this substance from the spiritual world through the green color in the spiritual realm. The moment you see green, red, blue, and yellow in gemstones, you are looking back into an infinitely distant past. When we see colors, we do not see only the present; when we see colors, we see far back into time. We cannot see a colored gemstone in the present, just as we cannot see a ruin at the top of a mountain when we are standing at the foot of that mountain. Because we are removed from the whole fact, we have to see it in perspective.

When we encounter a topaz, we cannot see it only in the present moment; we must look into a temporal perspective. And when we look into the perspective of time, prompted by the gemstone, we see the primordial ground of the creation of the earth before the Lemurian epoch of our earth's development, and we see the gemstone created out of the spiritual realm, and thus we see it in color. Here our physics does something tremendously absurd. It places this world before us and behind it vibrating atoms, which are supposed to cause the colors in us, while it is the divine-spiritual beings who created infinitely long ago who come to life in the colors of the stones, evoking a living memory of their primeval creation. When we see lifeless nature in color, we realize in our interaction with lifeless nature a memory of times far, far in the past. And every time the green carpet of plants appears before us in spring, those who can understand this emergence of green in nature see not only the present, but also look back to the time when, during an ancient solar existence, the plant world was created out of the spiritual, and this creation out of the spiritual took place in greenery. You see, we truly see the colors in nature when the colors inspire us to see the ancient creation of the gods in this nature.

To do this, however, we first need the artistic ability to live with color. For example, as I have often indicated and as you can read in the relevant lectures at the Goetheanum, we need the ability to perceive the surface as such: when I paint the surface blue, it recedes backward; when I paint it red or yellow, it approaches forward. For it is color perspective, not line perspective, that we must recapture: the perception of the surface, of distance and proximity, not merely with line perspective, which actually always seeks to conjure up plasticity on the surface through distortion, but rather with color on the surface, intensively, not extensively, receding and approaching, so that I actually paint in yellow-red when I want to suggest that something is aggressive, that something is on the surface that wants to jump out at me, so to speak. If something is calm in itself, if it distances itself from me, if it moves backwards, I paint it in blue-violet. Intense color perspective! Study the old painters, and you will find everywhere that even the painters of the early Renaissance still had a keen sense of this color perspective. But it is everywhere in the pre-Renaissance period, for it was only with the fifth post-Atlantean period that linear perspective replaced color perspective, the intense perspective.

This is how painting gains its relationship to the spiritual. It is strange, you see, that today people mainly think about how we can make space even more spatial if we want to go beyond space. And they use a fourth dimension in this materialistic way. But this fourth dimension does not exist in this way at all; rather, it exists in such a way that it destroys the third dimension, just as debts destroy wealth. As soon as you leave three-dimensional space, you do not enter a four-dimensional space, or you enter a fourth-dimensional space for my sake, but it is two-dimensional because the fourth dimension destroys the third and only two remain as real, and everything is oriented according to the two dimensions when we rise from the three dimensions of the physical to the etheric. We only understand the etheric when we think of it as oriented towards two dimensions. You will say, but I also go from here to there in the etheric, that is, in three dimensions. Only the third dimension has no meaning for the etheric, but only the two dimensions always have meaning. The third dimension is always expressed through the nuanced red, yellow, blue, violet, as I bring it onto the surface, regardless of whether I have the surface here or there, because in the etheric realm it is not the third dimension that changes, but the color, and it does not matter where I place the surface, I only have to change the colors accordingly. This gives us the opportunity to live with color, to live with color in two dimensions. But in doing so, we rise from the spatial arts to the arts that, like painting, are now two-dimensional, and overcome the merely spatial. Everything that is feeling within us has no relation to the three spatial dimensions; only the will has a relation to them, not feeling, which is always confined to two dimensions. Therefore, we find that what is emotional within us can potentially be reproduced in what painting can express in two dimensions, if we really understand the two dimensions correctly.

You see, one must extricate oneself from three-dimensional materiality if one wants to develop from architecture, clothing design, and sculpture to painting. In painting, one has an art form in which one can say that people can experience the painterly internally, spiritually, because when they create or enjoy painting, it is first experienced internally, spiritually. But they actually experience the external. They experience it in color perspective. There is no longer any difference between inside and outside. One cannot say, as one must in architecture, that the soul wants to create the forms it needs when it looks into the body. In sculpture, the soul wants to create forms in the sculpturally designed human being, where the human being places himself meaningfully in space in the present in a way that is natural to him. In painting, none of this comes into consideration. In painting, it actually makes no sense to talk about anything being inside or outside, or the soul being inside and outside. The soul is always in the spiritual realm when it lives in color. It is, so to speak, the free movement of the soul in the cosmos that is experienced in painting. It does not matter whether we experience the picture internally or see it externally when we see it in color, apart from the imperfection of the external colorants.