The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

31 January 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

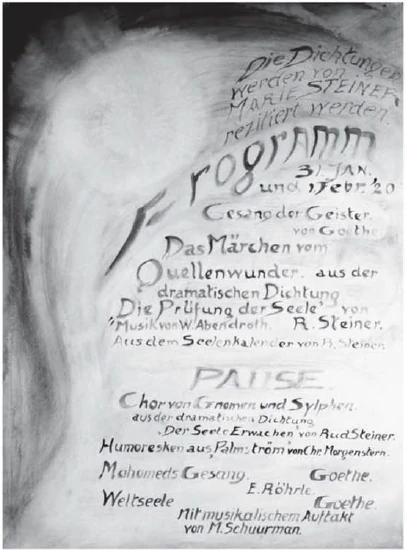

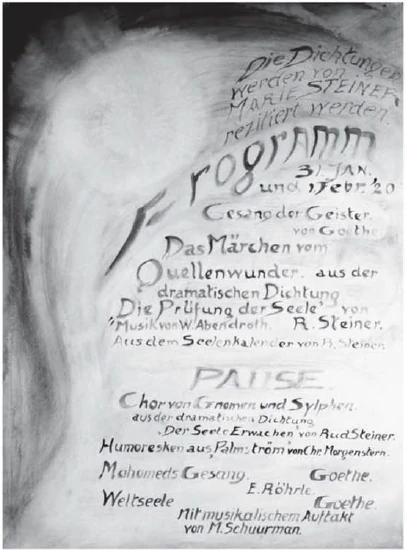

44. Eurythmy Performance

Allow me, dear assembled guests, as always before these performances, to say a few words about the nature of our eurythmy art. It is certainly not my intention to give some kind of explanation of the eurythmic art as such; that would be an unartistic endeavor, because everything artistic must not work through some kind of theoretical view, but through the immediate impression, through that which is directly revealed in art. But our eurythmic art can very easily be confused with all kinds of neighboring arts. It would be a real mistake to equate it with the art of dance, the art of gestures and the like, because what you will see presented here as eurythmy is drawn from very specific new artistic sources. And like everything that is done here, for which this building - the Goetheanum - is intended to be the representative, like everything is imbued with what one can call the Goethean world view, so too is our eurythmic art imbued with a Goethean artistic attitude and a Goethean artistic concept.

Of course, Goethe should not be taken as the Goethegelchrten take him: as the personality who died in 1832 and whose lifetime can be studied externally. Rather, Goethe must be taken as a continuing cultural factor for humanity, which is becoming different with each passing year. When we speak of Goethe, of Goetheanism, we are not speaking of the Goetheanism of 1832, but of the Goetheanism of the 20th century, of the year 1920. And here it is a matter of the fact that Goethe wanted to replace the dead orientation towards the world, which still dominates our present-day view, with a living one. This living view, namely of the workings of living beings themselves up to and including human beings, as found in Goethe, is still far from being sufficiently appreciated, far from being understood in any way. It will have to become a shot in the whole spiritual development of humanity. Those who today believe they already understand Goetheanism in its direction misunderstand precisely the most intimate, the most important.

What is presented here as eurythmy art is taken from Goethean sensual-supersensory vision, from the whole human being. Just as Goethe, in accordance with his living view of the world, sees a more intricately designed leaf in the whole plant, so too is the human being, not only in form but also in all the movements he can make, only a more complicated more complicated form of one of his organs, and in particular a more complicated form of the most outstanding, truly human organ - the larynx and its neighboring organs, when they serve as the tools for speech.

But now the question is, firstly, in order to bring forth eurythmy through sensory-supersensory observation, one must first place oneself in a position - which is a lengthy soul-spiritual task - to recognize which movements, but especially which movement systems, underlie the larynx, lungs, palate, tongue and so on when they produce speech sounds. A certain movement underlies this – we can see this from the fact that the entire air mass in the room in which I am speaking is in motion. We do not pay attention to this movement when we listen to the sound, when we listen to the speech sounds.

But this movement can be recognized separately, and then it can be transferred to the movements of the whole human being. And so you will see how the whole person in front of you here on stage becomes, so to speak, a larynx and how, through this, a mute language actually arises in eurythmy, a mute language that is not arbitrarily interpreted in some way, but that is brought forth from the human organism's organ systems just as lawfully as spoken language. But the fact that what otherwise remains invisible is made visible when speaking - partly through the moving human being, partly through the groups of people in their mutual movements and positions - means that the artistic aspect of revealing oneself through language can be particularly emphasized.

For in our language, even when poetic art expresses itself through it, there is in fact only as much real art as there is musicality in this language on the one hand, and plastic form on the other. The literal content, which is usually what unartistic observers of poetry place the greatest value on, is not actually part of the real art. The works of real art are much rarer than one might think. Before Schiller visualized the literal content of a poem in his mind, there was always a kind of wordless melodious element at the base, a rhythmic, metrical, melodious element, and only then did he string the literal words on to it. Goethe, who was more of a plastic poet, had something formative in his language. And this formative quality can be seen if one can feel real Goethean poetry.

Thus what actually underlies poetry is itself a hidden eurhythmy. It is studied and transferred to the movements of the whole human being. There is nothing arbitrary about these movements. There is something in these movements that proceeds in such a lawful sequence, as the melodious lawfulness or the lawfulness of harmony next to each other in music itself reveal themselves. But this means that in eurythmy, in particular, one can achieve something especially artistic, because in our spoken language, much that is conventional and utilitarian is interwoven. We have our language for human communication. What adheres to it from this side is precisely what is inartistic, so that the more the unconscious of language emerges, the more the artistic comes to the fore.

We must not forget that language is actually born out of the unconscious and the world of dreams in the individual human being as well. The child has not yet awakened to full consciousness of itself while it is learning to speak. Just as the images of the dream enter into human consciousness as a darkness of this consciousness, so the consciousness of the child is still dark when it learns phonetic language. On the one hand, this indicates that spoken language contains something that wells up from the unconscious of the human being. This unconscious must be taken into account in all linguistic matters. I would just ask you to consider one thing above all: grammar, that is to say, the internal logical structure of language, which then becomes artistic when language is treated artistically. This is not more complete or developed in the so-called civilized languages, but rather the more complicated grammar is usually found in uncivilized languages.

Thus, that which runs through language as its inherent law does not come from what stems from civilized consciousness. This law-abiding, subconscious element is what is drawn out of the human being. In this way, however, eurythmy becomes the opposite of dreaming. While dreaming means a lowering of consciousness, above all a lowering of the will, in eurythmy the will, as it arises in speech, is brought out; it is shaped into speech as an element; through a mute speech, a self-revelation of the human being is willed. But in this way we enter into the unconscious creative process of the human being in a conscious way, and we come to use the human being himself in his entire organic formation and range of motion as an artistic tool.

And if we consider that the human being is the most perfect being, we might say, that we know in this world, then something like an embodiment of the artistic expression that is otherwise possible must come out when one uses one's self as an artistic tool. Everything in this eurythmy is so completely derived from the laws of human nature that there is absolutely nothing arbitrary about it, no random gestures or the like. If two people or two groups of people in two completely different places were to perform the same thing in eurythmy, the performance would show no more differences than if the same sonata were performed according to a subjective interpretation. There is always a lawfulness in eurythmy, just as there is in music itself. Therefore, through this silent language of eurythmy, which has been brought forth from the same natural lawfulness as spoken language, a deep artistic experience can be achieved precisely because the mental aspect that otherwise works in language has been eliminated.

And so you will see how, on the one hand, poetry or even musical expressions are presented to you through the silent language of eurythmy. At the same time, in some cases you will see musical elements, which are only another form of expression of what eurythmy is. On the other hand, you will hear poetry recited in spoken language, and you will see that when you present the same poetry on stage in a plastic way through eurythmy , you will see that you are compelled to depart from the present-day inartistic nature of recitation, which is based on the particular emphasis of the content alone. Rather, the important thing here in recitation is to express what is already eurythmic in the poetry itself. What is the plastic form, rhythm, beat, musical element that underlies the actual poetry and what is the moving element in the poetry that lives in the beat, rhythm, what can be sensed in the form behind the words - this must be particularly developed in the recitation, which is especially intended to accompany this eurythmy. We must therefore go back to the form of the art of recitation that was practised when people still had a feeling for the art of recitation itself. Today this is very rarely the case; today one takes more the prose content, only the actually inartistic itself in the poetry and recites accordingly. So, of course, eurythmy itself will still be misunderstood today because it represents something completely new in the sources from which it has emerged, and the accompanying recitation will perhaps also be misunderstood. But that is not the point. Everything that presents itself as something original in the development of human civilization is usually viewed with suspicion. Nevertheless, I would ask you to bear in mind that we ourselves are our harshest critics and to see what we are not yet able to do today. We regard what we can already do today as nothing more than a beginning that is in great need of further development and refinement. You will see that poems which are themselves conceived as impressions, such as the 'Quellenwunder', which therefore already have eurythmy in them, can be translated into eurythmy particularly well, I would even say as a matter of course. But you will also see that where there is real inner mobility and plasticity in a poem, as in so many of Goethe's poems, eurythmy can indeed achieve a great deal.

In the humorous pieces that we will present to you today, you will see how one can follow them without resorting to pantomime and facial expressions, which are only random gestures, but how one follow these things through eurythmic-musical spatial forms, that is, through the musical element translated into space through eurythmy. This underlaying element is particularly emphasized.

I therefore ask you to take our performance with a grain of salt. Today we can only offer you the beginning, but we can still say that eurythmy – because it uses the human being, who is a real microcosm, as its instrument – perhaps allows the word with which Goethe wanted to characterize the truly artistic to be applied to it: When man is placed at the summit of nature, he regards himself as a complete nature, which must produce a summit within itself. To do so, he elevates himself by permeating himself with all perfection and virtue, invoking choice, order, harmony and meaning, and finally rising to the production of the work of art. Or the other beautiful word: “When man's healthy nature works as a whole, when he feels himself in the world as a great, beautiful, dignified and valuable whole, when harmonious comfort grants him a pure, free delight – then the universe, if it could feel itself, would exult as having attained its goal and would admire the summit of its own becoming and being.

In eurythmy, a language should be spoken by the human being not as in spoken language, where the individual human being speaks from their emotions, but rather it should be spoken as if the human being were included in the whole human being and spoke through and from it.

As I said, it is all still in its infancy, but we are also convinced that – precisely because we are our own harshest critics and although we ask for lenient judgment – we are convinced that this eurythmy will continue to be developed, by us or probably by others. And if it finds interest in the broadest circles, it will one day be able to stand alongside other, older, fully-fledged art forms as an art form in its own right.

[Before the break:]

After the break, we will be able to present you, dear attendees, with a scene of gnomes and sylphs. In this scene, we will attempt to reveal the mysterious forces of nature that can reveal themselves in the coexistence of humans and nature. This will be done through that aspect of the forces of nature that cannot be accessed by engaging with nature in purely abstract thought or in so-called natural phenomena. It will perhaps take a long time before it is admitted that there is a working and ruling, a weaving and living in nature that cannot be grasped through abstraction and natural laws, but that can only be grasped when our conception of nature is enlivened by real artistic forms. Nature tells us so much and so intensely that what it tells us must be told in more comprehensive and intense forms than can be done by abstract laws of nature.

Something like this has been attempted to be extracted from those laws of nature: What we experience when we really bring the human being into a pure, I would even say intimate picture with what flows and weaves through nature, something like this has been attempted in this gnome and sylph choir. And here too, Goethe's artistic philosophy is the basis. For Goethe has brought art and knowledge into a very close relationship, and he sees in art that which at the same time imparts a higher knowledge of the mystery of man and the world than mere knowledge of nature can. That is why Goethe says: “When nature begins to reveal her secrets to someone, they feel an irresistible longing for her most worthy interpreter, art.” And even if this is still regarded as something lay or dilettantish compared to so-called strict science, people will come to understand that the knowledge of what reigns as a secret in nature must be recognized in nature as a secret, namely, that one can recognize its secrets precisely by artistically responding to what nature reveals out of itself when one only engages with it.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Gestatten Sie, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass ich auch heute, wie immer vor diesen Vorstellungen, ein paar Worte über den Charakter unsrer eurythmischen Kunst vorausschicke. Es geschieht das gewiss nicht, um eine Art Erklärung abzugeben über die eurythmische Kunst als solche; das wäre ein unkünstlerisches Beginnen, denn alles Künstlerische muss ja wirken nicht durch irgendeine theoretische Anschauung, sondern durch den unmittelbaren Eindruck, [durch] dasjenige, was sich unmittelbar in der Kunst offenbart. Allein, es kann ja unsere eurythmische Kunst sehr leicht verwechselt werden mit allerlei Nachbarkünsten. Es wäre wirklich eine Verwechslung, wenn man sie gleichstellen würde mit Tanzkunst, Gebärdenkünsten und dergleichen, denn was Sie hier als Eurythmie vorgeführt bekommen werden, ist aus ganz bestimmten neuen Kunstquellen herausgeschöpft. Und wie alles, was hier getrieben wird, wofür dieser Bau —das Goetheanum - der Repräsentant sein soll, wie alles durchtränkt ist von dem, was man nennen kann Goethe’sche Weltanschauung, so ist auch unsere eurythmische Kunst durchtränkt von Goethe’scher Kunstgesinnung und Goethe’scher Kunstauffassung.

Natürlich muss dabei Goethe nicht so genommen werden, wie die Goethegelchrten ihn nehmen: Als diejenige Persönlichkeit, die 1832 gestorben ist und deren Lebenszeit man äußerlich studieren kann. Sondern Goethe muss so genommen werden: als ein fortwirkender Kulturfaktor der Menschheit, der auch jetzt noch mit jedem Jahre ein anderer wird. Wenn von Goethe gesprochen wird, von Goetheanismus, so wird nicht von dem Goetheanismus des Jahres 1832 gesprochen, sondern von dem Goetheanismus des 20. Jahrhunderts, vom Jahre 1920. Und da handelt es sich darum, dass ja Goethe an die Stelle der toten, auch unsere heutige Anschauung noch beherrschenden Orientierung über die Welt, eine lebendige setzen wollte. Diese lebendige Anschauung namentlich von dem Wirken der Lebewesen selbst bis herauf zum Menschen, wie sie sich bei Goethe findet, sie ist noch lange nicht genug gewürdigt, lange nicht irgendwie verstanden. Sie wird ein Einschuss der ganzen geistigen Entwicklung der Menschheit werden müssen. Diejenigen, die heute glauben schon etwas zu verstehen von Goetheanismus in seiner Richtung, die missverstehen gerade das Allerintimste, das Allergewichtigste.

Dasjenige, was hier als eurythmische Kunst dargeboten wird, es ist aus Goethe’schem sinnlich-übersinnlichem Schauen herausgeholt, aus dem ganzen Menschen. So, wie Goethe in der ganzen Pflanze nach seiner lebendigen Weltauffassung ein komplizierter ausgestaltetes Blatt sieht, so ist in der Tat nicht nur der Form nach, sondern allen Bewegungen nach, die er machen kann, der Mensch nur eine kompliziertere Ausgestaltung eines einzelnen seiner Organe, und insbesondere eine Ausgestaltung in komplizierterer Art des hervorragendsten, eigentlich menschlichsten Organes - des Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane, wenn sie die Werkzeuge abgeben für die Lautsprache.

Nun aber handelt es sich darum, dass man erstens, um Eurythmie hervorzubringen durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen, sich in die Lage versetzt - was eine langwierige seelisch-geistige Arbeit ist - zu erkennen, welche Bewegungen, namentlich aber Bewegungsanlagen zugrunde liegen dem Kehlkopf, der Lunge, dem Gaumen, der Zunge und so weiter, wenn sie hervorbringen die Lautsprache. Da liegt zugrunde - das kann schon abgenommen werden daraus, dass ja die ganze Luftmasse eines Raumes, in welchem ich spreche, in Bewegung ist -, da liegt zugrunde eine gewisse Bewegung. Auf diese Bewegung wenden wir die Aufmerksamkeit nicht, wenn wir dem Ton zuhören, wenn wir der Lautsprache zuhören.

Aber diese Bewegung kann eben abgesondert erkannt werden, und dann kann sie übertragen werden auf Bewegungen des ganzen Menschen. Und so werden Sie sehen, wie der ganze Mensch vor Ihnen hier auf der Bühne gewissermaßen zum Kehlkopfe wird und dadurch in der Eurythmie tatsächlich eine stumme Sprache entsteht, eine stumme Sprache, die nicht irgendwie willkürlich auszudeuten ist, sondern die ebenso gesetzmäßig aus den Organanlagen des menschlichen Organismus hervorgeholt ist wie die Lautsprache. Aber dadurch, dass so dasjenige, was sonst unsichtbar bleibt, beim Sprechen sichtbar gemacht wird - teils durch den bewegten Menschen, teils durch die Menschengruppen in ihren gegenseitigen Bewegungen und Stellungen -, dadurch kann man das Künstlerische des Sich-durch-die-Sprache-Offenbarens besonders herausheben.

Denn in unserer Sprache ist, auch wenn dichterische Kunst sich durch sie ausdrückt, in der Tat nur so viel wirkliche Kunst, als in dieser Sprache Musikalisches auf der einen Seite ist, und PlastischGestaltetes auf der anderen Seite ist. Dasjenige, was der wortwörtliche Inhalt ist, worauf man gewöhnlich, wenn man unkünstlerisch die Dichtungen betrachtet, den größten Wert legt, das gehört eigentlich gar nicht zum Wirklichen der Kunst. Die Werke der wirklichen Kunst sind viel seltener, als man denkt. Schiller hatte, bevor er den wortwörtlichen Inhalt eines Gedichtes in der Seele sich vergegenwärtigte, immer eine Art wortloses melodiöses Element zugrunde liegend, ein rhythmisches, taktmäßiges, melodiöses Element, und daran reihte er erst das Wortwörtliche auf. Goethe, der mehr ein plastischer Dichter war, er hatte etwas Gestaltendes in seiner Sprache. Und dieses Gestaltende, das kann man durchschauen, wenn man wirkliche Goethe’sche Dichtung empfinden kann.

So ist dasjenige, was eigentlich der Dichtung zugrunde liegt, selbst schon ein verborgenes Eurythmisches. Es wird studiert und auf die Bewegungen des ganzen Menschen übertragen. Dann ist nichts Willkürliches in diesen Bewegungen, dann ist in diesen Bewegungen etwas, was so gesetzmäßig nacheinander verläuft, wie die melodiöse Gesetzmäßigkeit oder die Gesetzmäßigkeit der Harmonie nebeneinander in der Musik selber sich offenbaren. Dadurch erreicht man es aber, dass man gerade in der Eurythmie etwas besonders Künstlerisches zustande bringen kann, denn in unserer Lautsprache ist viel Konventionelles, Nützlichkeitsgemäßes eingeschaltet. Wir haben ja unsere Sprache zur menschlichen Verständigung. Was ihr anhaftet von dieser Seite her, das ist gerade das Unkünstlerische, sodass das Künstlerische immer mehr zum Vorschein kommt, je mehr das Unbewusste der Sprache hervordringt.

Man darf nicht vergessen, dass die Sprache eigentlich auch im einzelnen Menschen aus dem Unbewussten, Traumhaften heraus geboren wird. Das Kind ist noch nicht zum vollen Bewusstsein seiner selbst erwacht, während es sprechen lernt. So, wie die Bilder des Traumes sich hineinstellen in das menschliche Bewusstsein als ein Dunkles dieses Bewusstseins, so ist noch das Bewusstsein des Kindes dunkel, wenn die Lautsprache von ihm gelernt wird. Das deutet auf der einen Seite darauf hin, wie die Lautsprache etwas enthält, was aus dem Unbewussten des Menschen heraufquillt. Auf dieses Unbewusste muss man bei allem Sprachlichen Rücksicht nehmen. Ich bitte Sie nur, vor allen Dingen zum Beispiel das eine zu bedenken: Grammatik, also der innerlich logische Aufbau der Sprache, der dann in Künstlerisches übergeht, wenn die Sprache eben künstlerisch behandelt wird, der ist nicht etwa bei den sogenannten zivilisierten Sprachen der vollkommnere oder das Ausgebaute, sondern gerade bei den unzivilisierten Sprachen ist gewöhnlich die kompliziertere [Lücke im Text] Grammatik vorhanden.

Also nicht aus dem, was aus dem zivilisierten Bewusstsein heraus stammt, kommt dasjenige, was die Sprache als ihre Gesetzmäßigkeit durchzieht. Dieses gesetzmäßige, unterbewusste Element, das ist es, was herausgeholt wird aus dem Menschen. Dadurch wird die Eurythmie allerdings das Gegenteil des Träumerischen. Während der Traum ein Herabstimmen des Bewusstseins bedeutet, vor allen Dingen ein Herabstimmen des Willens, wird in Eurythmie der Wille, wie er in der Sprache entsteht, [der] als ein Element [sich] hineingestaltet, herausgeholt; willensmäßig [wird] ein Sich-Offenbaren des Menschen durch eine stumme Sprache herbeigeführt. Dadurch aber gelangen wir geradezu bewusst in das unbewusste Schöpferische des Menschen hinein, und wir kommen dazu, den Menschen selber in seiner ganzen organischen Gestaltung und Bewegungsmöglichkeit als ein künstlerisches Werkzeug zu benützen.

Und wenn man bedenkt, dass der Mensch das vollkommenste Wesen ist, sagen wir, das wir in dieser Welt kennen, so muss auch, wenn man sich seiner bedient als eines künstlerischen Werkzeuges, etwas wie eine Verkörperung des künstlerischen Ausdruckes, der sonst möglich ist, überhaupt herauskommen. So sehr ist alles aus der Gesetzmäßigkeit der menschlichen Natur bei dieser Eurythmie herausgeholt, dass durchaus nichts Willkürliches - also nicht Zufallsgebärden oder dergleichen - drinnen sind. Wenn zwei Menschen oder zwei Menschengruppen an zwei ganz verschiedenen Orten ein und dieselbe Sache eurythmisch darstellen würden, so würde die Darstellung nicht mehr Unterschiede aufweisen, als wenn ein und dieselbe Sonate nach einer subjektiven Auffassung gegeben würde. Es ist immer eine Gesetzmäßigkeit im Eurythmischen da, so wie im Musikalischen selbst. Daher kann durch diese stumme Sprache der Eurythmie, die aus derselben Naturgesetzmäßigkeit hervorgeholt worden ist wie die Lautsprache, gerade ein tiefer Künstlerisches erreicht werden, indem das Gedankenmäfige, das sonst in der Sprache wirkt, zur Ausschaltung gekommen ist.

Und so werden Sie sehen, wie auf der einen Seite Ihnen Dichtungen oder auch selbst musikalisch Ausdrückbares durch die stumme Sprache der Eurythmie dargestellt werden. Parallel gehend werden Sie dann in einigen Fällen Musikalisches sehen, das ja nur eine andere Ausdrucksart gibt desjenigen, was eurythmische Darstellung ist. Auf der anderen Seite werden Sie Dichtungen durch die Lautsprache rezitiert hören, und dabei werden Sie sehen, dass man ja gerade gezwungen ist, wenn man dieselbe Dichtung, die auf der Bühne durch die Eurythmie plastizierend dargestellt wird, wenn man sie rezitierend begleitend darstellt, [dass] man gezwungen ist, abzugehen von dem heutigen Unkünstlerischen des Rezitierens, das auf der besonderen Hervorhebung des Inhaltes allein beruht. Dass es vielmehr hier darauf ankommt im Rezitieren, auszudrücken dasjenige, was in der Dichtung selbst schon eurythmisch ist. Was als plastische Gestaltung, Rhythmus, Takt, Musikalisches der eigentlichen Dichtung zugrunde liegt und wofür dasjenige, was als bewegtes Element in der Dichtung lebt taktmäßig, rhythmisch, dasjenige, was im Gestalteten geahnt werden kann hinter den Worten - das muss in der Rezitation, die besonders diese Eurythmie begleiten soll, ganz besonders ausgearbeitet werden. Daher wird wieder zurückgegangen werden hier auf diejenige Form der Rezitationskunst, die geübt wurde, als man noch ein Gefühl hatte von der eigentlichen Rezitationskunst. Heute ist das sehr selten vorhanden, heute nimmt man mehr den Prosainhalt, nur das eigentlich Unkünstlerische selbst in der Dichtung wahr und rezitiert danach. So wird heute natürlich noch missverstanden werden die Eurythmie selbst, weil sie etwas durchaus Neues in den Quellen darstellt, aus denen sie hervorgeholt ist, und missverstanden werden wird vielleicht auch die begleitende Rezitation. Allein, darauf kommt es nicht an. Alles dasjenige, was sich als ein Ursprüngliches hineinstellt in die menschliche Zivilisationsentwicklung, das wird ja zumeist mit scheelen Augen angesehen. Dennoch darf ich aber bitten, zu berücksichtigen, dass wir selbst die strengsten Kritiker sind und sehen, was wir heute noch nicht können. Wir betrachten das, was wir heute schon leisten können, als nichts anderes als einen Anfang, der gar sehr der weiteren Ausbildung, der weiteren Vervollkommnung bedarf. Sie werden zwar sehen, dass Dichtungen, die selbst schon als Impressionen gedacht sind wie das «Quellenwunder», die also schon Eurythmisches in sich haben, dass diese Dichtungen sich besonders, ich möchte sagen wie selbstverständlich in Eurythmie umsetzen lassen. Sie werden aber auch sehen, dass, wo wirkliche innere Beweglichkeit und Plastik in einem Gedichte ist wie in so vielen Goethe’schen Gedichten, dass da in der Tat die Eurythmie manches leisten kann.

Auch in den Humoresken, die wir Ihnen heute vorführen werden, werden Sie sehen, wie man nachkommen kann, ohne dass man Pantomime und Mimik, die nur Zufallsgebärden sind, zu Hilfe nimmt, wie man nachkommen kann durch eurythmisch-musikalische Raumformen diesen Dingen, also durch eurythmisch in den Raum umgesetztes Musikalisches nachkommen kann dem, was als Komisches, Groteskes in der Dichtung auftritt. Gerade dieses Unterliegende wird ja ganz besonders getroffen.

Ich bitte Sie also, unsere Vorstellung mit Nachsicht aufzunehmen. Wir können Ihnen heute nur den Anfang bieten, können aber dennoch sagen, dass die Eurythmie - weil sie sich bedient des Menschen, der ein wirklicher Mikrokosmos ist, als ihres Instrumentes, als ihres Werkzeuges - vielleicht auf sich anwenden lässt das Wort, mit dem Goethe das eigentlich Künstlerische charakterisieren wollte: Wenn der Mensch auf den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, so sieht er sich wieder als eine ganze Natur an, die in sich abermals einen Gipfel hervorzubringen hat. Dazu steigert er sich, indem er sich mit allen Vollkommenheiten und Tugenden durchdringt, Wahl, Ordnung, Harmonie und Bedeutung aufruft und sich endlich zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes erhebt. Oder das andere schöne Wort: «Wenn die gesunde Natur des Menschen als ein Ganzes wirkt, wenn er sich in der Welt als in einem großen, schönen, würdigen und werten Ganzen fühlt, wenn das harmonische Behagen ihm ein reines, freies Entzücken gewährt - dann würde das Weltall, wenn es sich selbst empfinden könnte, als an sein Ziel gelangt aufjauchzen und den Gipfel des eigenen Werdens und Wesens bewundern.»

Es soll durch den Menschen in der Eurythmie eine Sprache gesprochen werden nicht wie in der Lautsprache, wo der individuelle Mensch, der einzelne Mensch aus seinen Emotionen heraus spricht, sondern es soll so gesprochen worden, als wenn der Mensch in der ganzen Menschenwesenheit eingeschaltet wäre und durch sie, aus ihr heraus sprechen würde.

Das ist, wie gesagt, alles noch im Anfange, aber wir sind auch überzeugt, dass - eben weil wir selbst unsere strengsten Kritiker sind und obwohl wir um nachsichtige Beurteilung bitten -, wir sind überzeugt, dass diese Eurythmie immer weiter ausgebildet werden wird, durch uns oder wahrscheinlich durch andere. Und wenn sie Interesse findet in weitesten Kreisen, so wird sie sich einstmals als eine vollberechtigte Kunstform neben andere, ältere vollberechtigte Kunstformen hinstellen können.

[Vor der Pause:]

Wir werden Ihnen nach der Pause, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, eine Gnomen- und Sylphenszene vorführen können. In derselben ist versucht, die geheimnisvollen Kräfte der Natur, die sich im Zusammenleben des Menschen mit der Natur offenbaren können, zur Offenbarung zu bringen, und zwar dasjenige im Naturwalten, was nicht erreicht werden kann durch ein Eingehen auf die Natur in bloß abstraktem Denken oder auf das sogenannte Naturgeschehen. Es wird vielleicht noch lange nicht zugegeben werden, dass in der Natur ein Wirken und Walten, ein Weben und Leben ist, das eben durch Abstraktion und durch Naturgesetze nicht zu erreichen ist, sondern das nur dann erreicht werden kann, wenn sich unsere Naturauffassung durch wirkliche künstlerische Formen belebt. Die Natur sagt uns so viel und so Intensives, dass, was sie uns sagt, wohl in umfangreicheren und intensiveren Formen gesagt werden muss, als durch abstrakte Naturgesetze geschehen kann.

So etwas ist versucht worden, herauszuholen aus jenen Naturgesetzen: Was wir dann erleben, wenn wir das Menschenwesen so recht in ein reines, ich möchte sagen in ein intimes Bild mit dem bringen, was durch die Natur wallt und webt, so etwas ist also in diesem Gnomen- und Sylphenchor einmal versucht worden. Und auch da liegt Goethe’sche Kunstgesinnung zugrunde. Denn Goethe hat durchaus die Kunst mit dem Erkennen in ein sehr nahes Verhältnis gebracht, und er sieht in der Kunst dasjenige, was zu gleicher Zeit ein höheres Erkennen des Menschen- und Weltenrätsels vermittelt, als es das bloße Naturerkennen kann. Deshalb sagt auch Goethe: «Wem die Natur ihr offenbares Geheimnis zu enthüllen anfängt, der empfindet eine unwiderstehliche Sehnsucht nach ihrer würdigsten Auslegerin, der Kunst.» Und man wird schon einmal noch einsehen, wenn das auch heute noch als irgendetwas Laienhaftes oder Dilettantisches angesehen wird gegenüber der sogenannten strengen Wissenschaft, man wird schon auch einsehen, dass durch ganz andere Mittel, als diese strenge Wissenschaft bieten kann, dasjenige erkannt werden muss, was in der Natur als Geheimnis waltet, namentlich, dass man gerade durch ein künstlerisches Eingehen auf dasjenige, was die Natur aus sich heraus offenbart, wenn man nur sich auf sie einlässt, ihre Geheimnisse erkennen kann.