The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

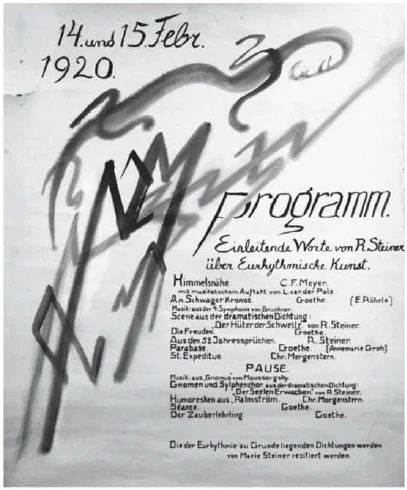

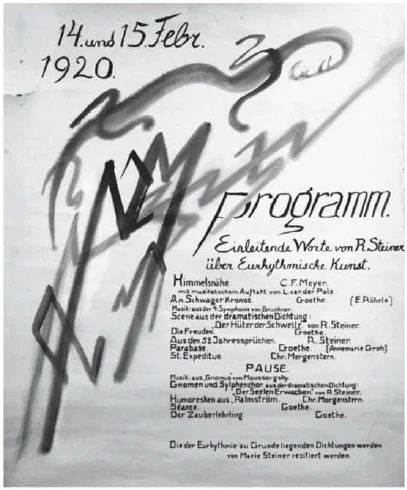

14 February 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

48. Eurythmy Performance

Dear attendees,

Anyone observing the development of art in our time will find that a whole series of young people aspiring to art are striving towards certain new goals for the development of art, and you are of course aware that these new artistic endeavors appear under the most diverse slogans. If you look for the reasons, the deeper reasons for these often extraordinarily questionable endeavors, you find that in fact in all areas of art, artistic natures themselves feel today: The means of expression that the arts have used in the most diverse epochs are actually exhausted, and a new source of artistic inspiration must be sought in various fields; in a sense, there must be a renewed appeal to the elementary, to the primitive artistic experience of man.

But when such an endeavor arises, then one must at least start from a very specific perception of the artistic. Now, as far as it can be seen in world development, everything artistic has two essential sources. One is external observation. This external observation can only provide art with something that it can process if it does not first pass through concepts, ideas, or images as an observation of nature. In more recent times, attempts have been made in various artistic fields to create something artistic from the immediate first impression that, let us say, a landscape can make. It was found that the old methods of painting had also been exhausted in this respect, that people had painted far too much from ideas, from impressions of nature that had already been processed, that they had, I might say, captured the moment before they had time to reflect, what was revealed to them in nature through light and air and so on. In short, the underlying aim is to present something artistically that is the result of external observation, but an observation that does not make it to the thinking grasp, because the thinking grasp is the opposite of everything artistic, is actually the death of everything artistic. Where there is a lot of symbolizing, a lot of spinning, a lot of concocting ideas, where one is supposed to arrange forms and colors and the like, art is killed. That is why people have tried to capture immediate impressions. They called these “impressions” and strove for an impressionistic art.

But for the time being, an important obstacle stands in the way of painting and sculpture. It is difficult for us to find in the present – here in this building it has been attempted – to capture form and color so directly, in sculpture and painting, to the exclusion of everything symbolic, everything conceptual, that one can let the artistic take effect with the exclusion of everything ideal, with the exclusion of everything conceptual. And once this building is finished, it will be seen that no complicated mystical ideas were sought to be embodied here through sculptural or pictorial forms, at least not in the main, that no symbols , but that the impression – both the architectural-sculptural and the sculptural-pictorial – should be sought directly in form and color, skipping the conceptual.

On the other hand, another source of the artistic is the inner experience of the human being, the artistic that rises to inner contemplation, and this source of the artistic has also been appealed to again from various sides in the [present-day] era, in the present. One tried to bring to expression that which one can only feel inwardly, experience inwardly. They tried it, for example, in the field of painting. But one can say: in the circles of younger artists who have endeavored in this direction, only questionable forms have been expressed up to now – for the simple reason that everything that is line, that is color, that is form, in a truly extraordinary way, if one wants to handle it technically, is opposed to that which is inner human experience.

Now there are two arts that seek to express inner human experience directly: music and poetry. But even in these arts, it is apparent that the source that the newer sense of art seeks to open up cannot yet be found in broader circles, wherever it is sought. The musical, that is in its form in the harmonic, in the melodic element, is not designed to directly express the full inner life as experienced by man, so that the musical is extremely reluctant to be expressionistic, to be visionary, and even something unhealthy enters into the musical when it wants to move towards the visionary.

On the other hand, poetry is terribly dependent on the development of human language. And here we have to say that our civilized languages have already come so far that they have an extraordinary amount of conventional thought elements. So that the poet today is obliged to express himself literally, actually at the expense of the original elementary artistic feeling, but in so doing enters into the element of thought, which from the outset is the death of all that is truly artistic. So that one can say that a large part of the poetry that is being created today does not actually promote art, but rather represses and kills it. And this can be seen particularly in what people like about poetry today. They often accept poetry as if it were prose, as if it were something that should have an effect through its literal content. But the truly poetic is only to be found in the musical and formal-plastic elements.

Now, if we really delve into the source of our spiritual movement, for which this Goetheanum building is the external representative, if we really delve into it, we come to the development of Goetheanism. In Goethe's entire artistic work, there is one striking thing, ladies and gentlemen. I believe I may say this, for I myself worked for seven years in the Goethe and Schiller Archives in Weimar, and took part in all that, which more or less remains unknown to a larger public, although it is the best of the present. One can say that what has been published from Weimar makes Goethe an extraordinarily effective writer today. Today, we learn a great deal about Goethe from what he did not do. I was most impressed by everything Goethe undertook in the course of his life, not by what he brought to such perfection as his [dramatic] works, such as “Iphigenia”, “Faust” and so on, but by what was left behind, what got stuck in the early beginnings. This also proves outwardly that in Goetheanism one does not have something that died with Goethe himself, but in Goetheanism, my dear audience, one can have something that is still effective in our time and can be made fruitful in our time. Goethe simply had such great artistic intentions that he himself, as a mortal human being, was no longer able to bring these things to anything other than fragments, so that the unfinished actually plays an enormously important role in Goethe's work. That is why today one always has the feeling that there is still a lot to be gained from Goetheanism. Well, this eurythmy, which uses the human being himself as a new artistic instrument and which wants to open up a special new source of art, is taken out of Goetheanism.

One can say that everything you will see performed on stage here, executed by movements of the human arms and other human limbs, performed by groups of people, is by no means arbitrary, these are not random gestures that are invented to accompany some invented for some poem or musical motif; it is something that is inwardly composed and built upon such laws, just as music itself is when it lives out in harmony or reveals itself in the sequence of time in melodious elements. Just as there is nothing arbitrary in music, but everything is inwardly lawful, so it is also with this visible but mute language of eurythmy, which particularly allows itself to be artistically revealed, to be revealed through the most perfect artistic instrument: through the human being himself.

So, you will see a silent language here on stage through the movements of the human limbs or the movements of groups of people. And this silent language has come about through what I call a Goethean expression: sensual-supersensory observation, through a supersensory observation of what actually happens when we reveal the spoken language that underlies ordinary poetry and use it as a means of human expression. Something very peculiar is at work here. This spoken language is a confluence of that which comes from the human thought and that which comes from the human will.

Now, the larynx and its neighboring organs are such that, when the impulses for movement are carried out, they do not come into contact with muscles, but are directly communicated to the outer element of air. The wonderful thing about our larynx is that its cartilaginous structure is directly adjacent to the external element of air. Only this makes it possible for the impulses of the thought element to flow through what the human will exerts on the larynx and its neighboring organs. But this means that something inartistic comes about, especially in poetry, which has to make use of language. The thought element comes in. But at the bottom of this thought element is the will element, coming from the whole human being. I would like to say: the thought, in speech, swims on the waves of the will.

Now in eurythmy, the thought element is completely suppressed. Only that which underlies poetic language as meter, as rhythm, as form, in short, as a plastic and musical element, is transferred into the movements. And this can be done by not speaking phonetically, but by having the whole person or groups of people perform those movements, which are otherwise only present in the larynx and its neighboring organs, as regularly as the larynx otherwise transmits them to the air, so that one then has the will element - opposing it, the muscular organization of the human being.

It is a different matter whether the movement patterns of the larynx and its neighboring organs are transmitted to the air when the mental element is received, and thus cause the movements of the air corresponding to the phonetic language, or whether the will of the person, coming from the whole person, directly impacts the muscle apparatus and sets the limbs in motion. This causes something quite different. The small vibrations that underlie speech, which are no longer perceived as movement, come about because the muscular element is not opposed by the larynx. But in the mute language of eurythmy, the will addresses the muscular element directly, the entire human element of movement, the muscular and skeletal system. And in the mute language of eurythmy, the whole human being, who becomes the larynx, brings forth what otherwise only spoken language brings forth.

In this way, eurythmy becomes an artistic element that always consists of rhythm and meter and arises particularly from the poetic and the musical, and presents a new artistic element to the present.

Therefore, the recitative element – which often alternates with the musical element, but mainly accompanies the silent speech – must be handled differently than recitation is often handled today. And if what is actually intended with the eurythmic element is already misunderstood, then it will be possible to misunderstand the accompaniment of the recitation in many cases today because it cannot go to the literal content – eury thmy would not be accompanied by recitation), but must go to the actual artistic element, which in our present, unartistic time is no longer felt in poetry: to the rhythmic, the metrical, which underlies the literal content. The art of recitation itself must return to the good old forms of recitation, which are still little understood today.

But you will see that when something has already been conceived as poetry in eurythmy, it can be expressed particularly well in the silent speech of eurythmy. Today, in addition to a few other things, we will present a scene from one of my mysteries in eurythmy, in which the laws of the world are expressed in such a way that thoughts alone are not enough to penetrate these laws of the world, but that other means of expression must be used to express what actually lives and weaves in nature. In this way, man is much closer to nature and the world in general than he is in the mere abstract comprehension of the so-called laws of nature, which actually only ever express an external aspect of nature.

But the artistic, too, if it wants to express the inner experience, cannot get by in the present, because when we use colors, when we use forms - no matter whether we use the stylus or the brush - these means of expression still resist the inner experience with the utmost brittleness. And that is why the expressionist pictures of today's younger painters look so strange, because the means to express what is experienced internally, but not yet driven to the inner element, where it becomes thought, because it [then] becomes inartistic.

But on the other hand, nature cannot be interpreted impressionistically; nature itself makes it necessary, so to speak, when we face it humanly, that we do not exclude thought; it cannot be interpreted impressionistically. The actual impression of nature cannot be artistically reproduced. But if you take the human being as a higher instrument, then you have the inner experience that does not come to spoken language, and thus does not come to the thought element, and you take the human being himself, by bringing his movements - that is, what can be observed - to the contemplation of the inner experience, excluding the element of thought. Expression in the immediate impression, that is something that can certainly become a possibility in eurythmy.

Now I am not saying that eurythmy is the only art that should replace other art forms, but I am saying that eurythmy can make it clear what the other means of expression should strive for those who, today, out of a good but still imperfect, I would say childlike, feeling, are looking for new sources of art. That on the one hand. On the other hand, we know full well – we are our own harshest critics – that our eurythmic art is still in its infancy. But we are absolutely convinced that this beginning is capable of perfection. I therefore ask you to accept what we can offer today in our eurythmic art with indulgence. For everything in its infancy is very easily misunderstood. On the other hand, however, we are well convinced that something is offered by this still very imperfect beginning, which, if it is further developed by us or by others, more likely the latter, and if it finds interest among our contemporaries, will be able to stand as a fully-fledged young art alongside the older fully-fledged arts and join them in the future.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Wer die Kunstentwicklung unserer Tage beobachtet, der wird finden, dass aus einer ganzen Reihe jüngerer kunststrebender Leute gewisse neue Ziele für die Kunstentwickelung angestrebt [werden], und Sie wissen ja, dass unter den verschiedensten Schlagworten diese neuen Kunstbestrebungen auftauchen. Wenn man nach den Gründen, nach den tieferen Gründen dieser oftmals außerordentlich bedenklichen Bestrebungen forscht, so findet man, dass eigentlich auf allen Kunstgebieten von künstlerischen Naturen selber heute empfunden wird: Die Ausdrucksmittel, deren sich die Künste in den verschiedensten Epochen bedient haben, sie seien eigentlich erschöpft, und es müsse ein neuer Quell des Künstlerischen auf verschiedenen Gebieten gesucht werden, es müsse gewissermaßen wiederum appelliert werden an das elementarische, an das primitive künstlerische Erleben des Menschen.

Dann aber, wenn solch ein Bestreben auftritt, dann muss man wenigstens ausgehen von einer ganz bestimmten Empfindung gegenüber dem Künstlerischen. Nun hat ja alles Künstlerische, soweit es überschaut werden kann in der Weltentwicklung, wesentlich zwei Quellen. Die eine ist die äußere Beobachtung. Diese äußere Beobachtung kann nur dann der Kunst etwas liefern, was sie verarbeiten kann, wenn sie als Naturbeobachtung nicht erst durch Begriffe, durch Ideen, durch Vorstellungen durchgeht. Man hat in der neueren Zeit auf dem Gebiete verschiedener Künste versucht, nach dem unmittelbaren ersten Eindruck - den, sagen wir zum Beispiel eine Landschaft machen kann - etwas Künstlerisches zu schaffen. Man fand, dass in dieser Beziehung auch die alten Mittel der Malerei erschöpft seien, dass man viel zu sehr gemalt hat nach Ideen, nach bereits verarbeiteten Natur-Eindrücken, dass man, ich möchte sagen im Augenblicke festhalten müsse, bevor man zum Nachdenken kommt, dasjenige, was einem in der Natur sich offenbart durch Licht und Luft und so weiter. Kurz: Das Bestreben liegt da zugrunde, einmal etwas künstlerisch hinzustellen, das das Ergebnis einer äußeren Beobachtung ist, aber einer Beobachtung, die es nicht bis zum denkenden Erfassen bringt, denn das denkende Erfassen ist das Gegenteil alles Künstlerischen, ist der Tod alles Künstlerischen eigentlich. Wo viel symbolisiert, wo viel spintisiert, wo viel in Ideen ausgeheckt wird, wo man Formen anordnen, Farben anordnen soll und dergleichen, da wird die Kunst getötet. Daher hat man versucht, unmittelbare Eindrücke festzuhalten. Man nannte diese «Impressionen» und strebte nach einer impressionistischen Kunst.

Aber es stellt sich vorläufig für Malerei, für Plastik ein gewichtiges Hindernis entgegen. Wir können in der Gegenwart nur schwer finden - hier in diesem Bau ist es versucht worden -, plastisch und malerisch mit Ausschluss alles Symbolistischen, alles Vorstellungsmäßigen, Form und Farbe nach dem unmittelbaren Eindrucke so festzuhalten, dass man das Künstlerische auf sich wirken lassen kann mit Ausschluss alles Ideellen, mit Ausschluss alles Gedanklichen. Und wenn einmal dieser Bau fertig sein wird, dann wird sich zeigen, dass hier nicht irgendwelche vertrackten mystischen Ideen durch plastische oder malerische Formen zu verkörpern gesucht worden sind, wenigstens in der Hauptsache nicht, dass hier keine Symbole verkörpert werden sollten, sondern dass unmittelbar in Form und in Farbe mit Überspringung des Vorstellungsmäßigen der Eindruck — sowohl der architektonisch-plastische wie der plastisch-malerische — gesucht worden [ist].

Auf der anderen Seite ist ein anderer Quell des Künstlerischen das innere Erlebnis des Menschen, das Künstlerische, das sich zum inneren Anschauen erhebt, und auch an diesen Quell des Künstlerischen hat man in der [heutigen] Zeit, in der Gegenwart, von verschiedenen Seiten wiederum appelliert. Man versuchte dasjenige, was man innerlich bloß empfinden, innerlich erleben kann, bis zur Expression zu bringen. Man versuchte es zum Beispiel auf dem Gebiete der Malerei. Aber man kann sagen: In den Kreisen jüngerer Künstlerschaft, welche sich in dieser Richtung bemüht haben, sind denn doch bis jetzt nur bedenkliche Formen zum Ausdrucke gekommen - aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil alles, was Linie ist, was Farbe ist, was Form ist, in einer wirklich außerordentlich starken Weise, wenn man es handhaben will technisch, widerstrebt demjenigen, was inneres menschliches Erlebnis ist.

Nun gibt es ja zwei Künste, die unmittelbar inneres menschliches Erlebnis ausdrücken wollen: Es sind die musikalische Kunst und die dichterische Kunst. Aber auch bei diesen Künsten zeigt sich, dass der Quell, den das neuere Kunstempfinden eröffnen möchte, im Grunde genommen in weiteren Kreisen, wo man ihn sucht, noch nicht gefunden werden kann. Das Musikalische, das ist in seiner Form im harmonischen, im melodischen Element zunächst nicht dazu geartet, unmittelbar das volle Innere, wie es der Mensch erlebt, auszusprechen, sodass das Musikalische dem Expressionistischen, dem Visionären außerordentlich stark widerstrebt, und sogar in das Musikalische etwas Ungesundes hineinkommt, wenn cs sich zum Visionären hinbegeben will.

Das Dichterische auf der andern Seite ist furchtbar stark abhängig von der Entwicklung der menschlichen Sprache. Und da muss man sagen, dass unsere zivilisierten Sprachen bereits so weit gekommen sind, dass sie außerordentlich viel von dem konventionellen Gedankenelement in sich haben. Sodass der Dichter heute genötigt ist, eigentlich auf Kosten des ursprünglichen elementarischen künstlerischen Empfindens sich wortwörtlich auszudrücken, damit aber in das Gedankenelement hineinkommt, das von vornherein eben der Tod alles wirklich Künstlerischen ist. Sodass man sagen kann, dass durch einen großen Teil des Dichterischen, welches heute entsteht, eigentlich die Kunst nicht einmal gefördert wird, sondern die Kunst sogar zurückgedrängt und ertötet wird. Und man sieht das ganz besonders an dem, was heute den Leuten an den Dichtungen gefällt. Sie nehmen die Dichtungen auch oftmals hin wie Prosaisches, wie dasjenige, das durch seinen wortwörtlichen Inhalt wirken soll. Das wirklich Dichterische aber ist nur in dem musikalischen und in dem formal-plastischen Elemente gelegen.

Nun, wenn man sich wirklich vertieft in dasjenige, wovon ausgehen will diese unsere Geistesströmung, für die hier dieser Goetheanum-Bau der äußere Repräsentant ist, wenn man sich wirklich in das vertieft, kommt man zur Ausgestaltung des Goetheanismus. Bei Goethe ist ja, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, in seinem ganzen künstlerischen Wirken eines das Auffällige. Ich glaube, ich darf das sagen, denn ich habe sieben Jahre in Weimar am Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv selbst gearbeitet, teilgenommen an all dem, was da mehr oder weniger wie das Beste der Gegenwart einem größeren Publikum unbekannt geblieben ist. Man kann sagen: Was da veröffentlicht worden ist von Weimar aus, das macht Goethe heute zu einem außerordentlich wirksamen Schriftsteller. Man lernt heute von Goethe manches kennen durch dasjenige, was er nicht gemacht hat. Auf mich hat den größten Eindruck alles dasjenige gemacht, was Goethe im Laufe seines Lebens unternommen hat, was er nicht zu einer solchen Vollkommenheit gebracht hat wie seine [dramatischen] Werke, wie «Iphigenie», wie «Faust» und so weiter, sondern was liegengeblieben ist, was in den ersten Anfängen steckengeblieben ist. Gerade das beweist auch äußerlich, dass man im Goetheanismus nicht etwas hat, was mit Goethe selbst gestorben ist, sondern im Goetheanismus, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, etwas haben kann, was noch in unserer Zeit wirkt und in unserer Zeit erst recht fruchtbar gemacht werden kann. Goethe hat einfach so große Kunstintentionen in sich getragen, dass er selbst als sterblicher Mensch nicht mehr fähig war, diese Dinge zu etwas anderem als zu Fragmenten zu bringen, sodass das Unvollendete in Goethes Schaffen eigentlich eine ungeheuer große Rolle spielt. Daher hat man heute immer das Gefühl, dass aus Goetheanismus noch viel, viel herauszuholen sei. Nun, herausgeholt aus dem Goetheanismus ist diese Eurythmie, die des Menschen selber sich bedient als eines neuen künstlerischen Instrumentes und die eine besondere neue Kunstquelle eröffnen will.

Man kann nämlich sagen: Alles dasjenige, was Sie hier sehen werden auf der Bühne ausgeführt von Bewegungen der menschlichen Arme, der anderen menschlichen Glieder, ausgeführt sehen von Menschengruppen, das ist durchaus nichts Willkürliches, das sind nicht Zufallsgebärden, die zu irgendeiner Dichtung oder einem musikalischen Motiv hinzu erfunden sind, das ist etwas innerlich in einer solchen Gesetzmäßigkeit Komponiertes und auf solche Gesetzmäßigkeit aufgebaut wie das Musikalische selber, wenn es sich auslebt im Harmonischen oder sich offenbart in der Zeitfolge im melodiösen Elemente. Wie in Musik nichts Willkürliches ist, sondern etwas innerlich Gesetzmäßiges, so ist es auch bei dieser sichtbaren, aber stummen Sprache der Eurythmie, die ganz besonders gestattet, künstlerisch sich zu offenbaren, sich zu offenbaren durch das vollkommenste künstlerische Instrument: durch den Menschen selber.

Es ist also eine stumme Sprache, die Sie hier von der Bühne aus durch Bewegungen der menschlichen Glieder oder durch Bewegungen von Menschengruppen sehen werden. Und diese stumme Sprache ist entstanden durch ein - ich gebrauche diesen Goethe’schen Ausdruck: sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen, durch eine übersinnliche Beobachtung desjenigen, was eigentlich vorgeht, wenn wir die gesprochene Sprache, die der gewöhnlichen Dichtung zugrunde liegt, zur Offenbarung bringen, als menschliches Ausdrucksmittel verwenden. Da liegt etwas sehr Eigentümliches vor. Diese gesprochene Sprache ist ein Zusammenfluss desjenigen, was aus dem Gedanken des Menschen kommt, und desjenigen, was aus dem Willen kommt.

Nun liegt beim Kehlkopf und seinen Nachbarorganen die Sache so, dass, indem da die Bewegungsantriebe ausgeführt werden, stoßen sie nicht an Muskeln, sondern sie teilen sich unmittelbar dem äußeren Elemente der Luft mit. Das ist ja die wunderbare Einrichtung unseres Kehlkopfes, dass er unmittelbar in seiner knorpeligen Konstitution angrenzt an das äußere Luftelement. Dadurch ist erst die Möglichkeit gegeben, dass dasjenige, was vom menschlichen Willen aus in den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane hineinwirkt, dass das durchströmt wird von den Impulsen des gedanklichen Elementes. Aber dadurch kommt gerade auch in der Dichtung, die sich der Sprache bedienen muss, etwas Unkünstlerisches zustande. Es kommt das Gedankenelement hinein. Aber auf dem Grunde dieses Gedankenelementes ist aus dem ganzen Menschen herauskommend das Willenselement. Ich möchte sagen: Der Gedanke, er schwimmt im Sprechen auf den Wellen des Willens.

Nun wird bei der eurythmischen stummen Sprache das Gedankenelement vollständig unterdrückt. Nur dasjenige, was der dichterischen Sprache als Takt, als Rhythmus, als Gestaltung, kurz als plastisches und musikalisches Element zugrunde liegt, das wird in die Bewegungen übertragen. Und das kann dadurch geschehen, dass, wenn man nicht lautlich sprechen lässt, sondern wenn man diejenigen Bewegungen, die sonst nur veranlagt sind im Kehlkopf und seinen Nachbarorganen, durch den ganzen Menschen oder durch Menschengruppen so regelmäßig ausführen lässt, wie sie sonst der Kehlkopf an die Luft überträgt, dass man dann das Willenselement hat - ihm widerstrebend die Muskelorganisation des Menschen.

Es ist etwas anderes, ob die Bewegungsanlagen des Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane mit Aufnahme des gedanklichen Elementes an die Luft übertragen werden und da die Bewegungen der Luft also der Lautsprache entsprechend hervorrufen oder ob der Wille des Menschen aus dem ganzen Menschen heraus unmittelbar an den Muskelapparat stößt und die Glieder in Bewegung bringt. Dadurch wird ein ganz anderes hervorgerufen. Die kleinen, nicht mehr als Bewegung wahrgenommenen Vibrationen, die der Sprache zugrunde liegen, die kommen dadurch zustande, dass dem Kehlkopf nicht das muskulöse Element entgegensteht. Aber bei der stummen Sprache der Eurythmie wendet sich der Wille unmittelbar an das Muskelelement, an das ganze Bewegungselement des Menschen, an Muskelsystem und Knochensystem - und es bringt der ganze Mensch, der zum Kehlkopf wird, in der stummen Sprache der Eurythmie das zum Vorschein, was sonst nur die Lautsprache zum Vorschein bringt.

Dadurch wird die Eurythmie für das künstlerische Element, das immer nur aus dem Rhythmischen, aus dem Taktmäßigen besteht, das ganz besonders aus dem Dichterischen und Musikalischen her[vor] geht, ein neues künstlerisches Element vor die Gegenwart hinstellen.

Daher muss auch das rezitatorische Element - das mit dem Musikalischen oftmals abwechselnd, aber als Hauptsächlichstes begleitend dasjenige, was als stumme Sprache auftritt -, dieses Rezitatorische muss in anderer Weise gehandhabt werden, als heute die Rezitation oftmals gehandhabt wird. Und wird man schon missverstehen dasjenige, was eigentlich gewollt wird mit dem eurythmischen Elemente, so wird man die Begleitung der Rezitation heute auch noch vielfach missverstehen können, weil sie nicht auf den wortwörtlichen Inhalt gehen kann - so würde sich die Eurythmie nicht rezitatorisch begleiten lassen -, sondern gehen muss auf das eigentlich Künstlerische, das in unserer heutigen, unkünstlerischen Zeit gar nicht mehr an der Dichtung empfunden wird: an das Rhythmische, Taktmäßige, das erst dem wortwörtlichen Inhalt zugrunde liegt. Die Rezitationskunst selbst muss wiederum zu guten alten Formen des Rezitierens zurückkehren, die heute noch wenig verstanden werden.

Aber Sie werden sehen: Gerade dann, wenn etwas schon als Dichtung eurythmisch gedacht ist, dann lässt sich das mit einer Sprachform der stummen Sprache der Eurythmie ganz besonders zum Ausdrucke bringen. Wir werden heute außer einigen anderem zur Darstellung bringen eurythmisch eine Szene aus einem meiner Mysterien, worinnen Weltengesetzmäßigkeiten so ausgedrückt werden, dass nicht Gedanken genügen, um zu diesen Weltgesetzmäßigkeiten vorzudringen, sondern dass man andere Ausdrucksmittel anwenden muss, um dasjenige, was eigentlich in der Natur webt und lebt, zum Ausdruck zu bringen. Da steht dann der Mensch der Natur und der Welt überhaupt schon ungemein viel näher, als er steht in dem bloßen abstrakten Begreifen der sogenannten Naturgesetze, die eigentlich immer nur ein Äußeres der Natur ausdrücken.

Nun kann aber auch das Künstlerische, wenn es das innere Erlebnis ausdrücken will, nicht in der Gegenwart zurechtkommen, weil, wenn wir Farben, wenn wir Formen verwenden - gleichgültig, ob wir den Griffel verwenden oder den Pinsel verwenden -, diese Ausdrucksmittel widerstreben noch mit äußerster Sprödigkeit dem inneren Erlebnis. Und deshalb nehmen sich die expressionistischen Bilder der heutigen jüngeren Maler so kurios aus, weil einfach die Mittel noch nicht gefunden sind, um dasjenige auszudrücken, was innerlich erlebt wird, aber noch nicht getrieben wird bis zum inneren Element, wo es Gedanke wird, weil es [dann] unkünstlerisch wird.

Aber auf der anderen Seite lässt sich die Natur nicht impressionistisch auslegen, die Natur macht es gewissermaßen selber notwendig, wenn wir uns ihr menschlich gegenüberstellen, dass wir den Gedanken nicht ausschließen; sie lässt sich nicht impressionistisch auslegen. Der eigentliche Eindruck von der Natur lässt sich nicht künstlerisch wiedergeben. Wenn man aber den Menschen als höheres Instrument nimmt, dann hat man das innere Erlebnis, das nicht bis zur gesprochenen Sprache kommt, also auch nicht bis zum gedanklichen Element, und man nimmt den Menschen selber, indem man [durch] seine Bewegungen - also das, was beobachtet werden kann - zur Anschauung bringt das innere Erleben mit Ausschluss des Gedankenelementes. Die Expression im unmittelbaren impressionistischen Eindruck, das ist dasjenige, was in der Eurythmie durchaus Möglichkeit werden kann.

Nun behaupte ich durchaus nicht, dass Eurythmie die einzige Kunst ist, die andere Kunstformen ersetzen soll, aber ich behaupte, dass die Eurythmie anschaulich machen kann, wohin mit den anderen Ausdrucksmitteln diejenigen streben sollen, die heute aus einem guten, aber noch unvollkommenen, ich möchte sagen kindlichen Empfinden nach neuen Kunstquellen suchen. Das auf der einen Seite. Auf der anderen Seite wissen wir gut - wir sind selbst unsere strengsten Kritiker —, dass unsere eurythmische Kunst noch im Anfange steht. Aber wir sind durchaus der Ansicht, dass dieser Anfang der Vervollkommnung fähig ist. Ich bitte Sie daher, dasjenige, was wir heute schon bieten können in unserer eurythmischen Kunst, mit Nachsicht aufzunehmen. Denn alles, was im Anfange ist, unterliegt zunächst dem Missverständnis sehr leicht. Aber wir sind auf der anderen Seite wohl davon überzeugt, dass mit diesem noch sehr unvollkommenen Anfang etwas gegeben ist, was, wenn es weiter ausgebildet werden wird durch uns oder durch andere, wahrscheinlicher das Letztere - und wenn cs Interesse findet bei den Zeitgenossen, sich als eine vollberechtigte junge Kunst den älteren vollberechtigten Künsten wird entgegenstellen können und mit ihnen in der Zukunft zusammengehen wird.