The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

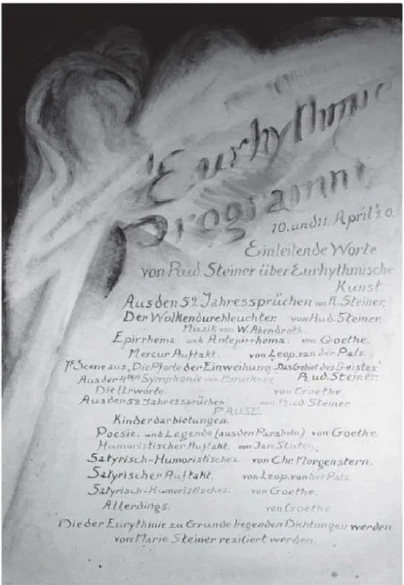

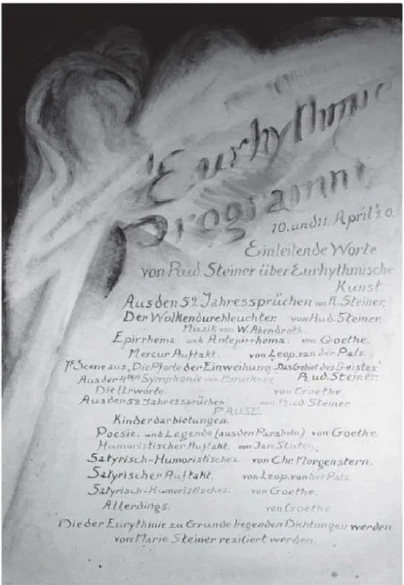

10 April 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

57. Eurythmy Performance

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen.

Allow me to begin today, as I always do before these eurythmy performances, with a few words about the significance of the eurythmic art. We have here an attempt at this eurythmic art, a beginning, one might say, of an attempt at a kind of silent language. You will see this silent language performed on stage in movements that are carried out by the human limbs - also through movements of the whole person in space - or through the alternating movements, through the alternating positions of personalities in groups and the like.

All of this could initially be seen as a mere art of gestures, where an attempt is made to express a poetic content, which is the underlying basis and is also recited during the performance, or to express a musical piece, which can also be the basis of the presentation and which is played or sung at the same time – it could look as if movement is used to add gestures or a certain facial expression to the poetic, literal or musical content that forms the leitmotif. It is not so, but with this eurythmic art, we are in fact trying to open up a new source of art and also to bring very special means of artistic expression. Here, the source is the human being itself. And the source opens up through a special training of what one can call in the sense of Goetheanism: the striving for the sensual-supernatural element in art.

We see, my dear attendees, today the most diverse efforts to get out of the old traditional art forms, to get out of the old artistic language, and to find something new as a means of artistic expression. We see this in the fields of sculpture, painting, and also in the field of poetry; in the field of music it has been noticeable for a long time and so on.

It is always the case, when a certain period of time has been fulfilled, that the forms for the art of this time become too intellectual. What is still intuitive and instinctive at the beginning of an artistic epoch, what arises from the most elementary emotions of the human being, is studied in the course of time, analyzed by the human intellect, and becomes artistic technique, but one that is imbued with intellect. And then it increasingly appears as imitation art, as something that a young generation will then use [reject].

Today, we see attempts to arrive at a new artistic formal language, particularly in Impressionism and Expressionism. However, despite the fact that nothing should be said against some extraordinarily significant beginnings in this direction, it must also be said that the most serious artists and connoisseurs in this field are somewhat dissatisfied. Take the field of painting, for example. It is not possible to merely conjure up certain elementary experiences - I would say half-servants of human nature, which are to be brought onto the canvas - and really express them properly in colors and lines. The special difficulty that exists in every art is that the intellectual element has a deadening, diluting effect on everything artistic to the extent that thoughts, ideas, and the intellectual in general enter into the artistic. The artistic is killed. This is why Goethe believed that the expression 'sensual-supersensory' is particularly appropriate for the artistic. There must be something immediate that can serve as a means of expression in the external world. But the moment any idea is impressed upon this means of expression, artistic enjoyment ceases. And I have the feeling that it is easiest to achieve something sensual and supersensual when one uses the human being himself as a tool for artistic expression.

But for this to happen, human speech must also be studied in a sensual and supersensible way. When a person makes himself audible, not only in poetry but also, for example, in song, through his vocal organs, through his speech organs, then the expression of these speech organs is always based on movements whose tendencies can be examined if one has the opportunity to rise above mere sensory observation through hearing and penetrate into that which is not directly heard but which underlies it as a movement, a movement of the larynx, a movement of the other organs involved in speaking or singing. The soul of human speech is based on the fact that the human being localizes his muscular system on the larynx and can use it to produce movements that then become speech simply through their peculiarity. These movements can be studied sensually and supersensibly. One must study the large course of what is organized by the larynx and the other speech organs into vibrations in the air, or, I should say, into the separation of many small vibrating movements. One must intuitively grasp the underlying tendencies of the movements.

Then what can be studied, what underlies speech in a completely lawful way, can be transferred to the whole human being, to the movement of all his limbs. So that in eurythmy, through such a transference, you can, as it were, make the whole human being function on the stage like a human larynx, I would say. One could say: if the movements that are performed for vowels, consonants, sentence contexts, for the inner character, for the structure of the sentence, to which these movements correspond, were not the whole human being, but if what one sees were to be placed directly into the larynx, then nothing else would be expressed in the larynx than what you hear as the accompanying recitation.

However, this does not make the art of eurythmy something arbitrary, but something as internally lawful as the melodic or harmonic element in music is internally lawful. If something is initially based on gestures or facial expressions, then it is something that has not yet been overcome, [because] something as lawful as in music itself lives in eurythmy. And in what is heard at the same time, there is something like a harmonic element in music. [But this is only possible if] one also goes back to what is actually poetic in poetry. Poetry is not an art through its literal content, in a sense through the prosaic that underlies it, but poetry is poetry through rhythm, through beat, through everything that is incorporated into the literal content as form.

This is what is expressed through eurythmy. But it must also be expressed in the recitation that accompanies the eurythmy. Therefore, in order to be able to accompany the eurythmy with recitation, we must go back to the good old forms of recitation, which are avoided today precisely where one believes one is reciting well: to the rhythmic, to the not on the emphasis of the prose content, on which so much emphasis is placed today in what, especially in our very unartistic time, is called good recitation. Here too, it must be borne in mind that this recourse to eurythmy for a new artistic element makes very special demands on the art of recitation. Through the fact that this eurythmy attempts to impress upon the human being himself that which is otherwise impressed upon him through hearing in speech, the human being himself becomes the means of sensory expression of art. And because the movements are not intellectually shaped into gestures, but because the movements unfold in such a way that they are natural to the human being, like the movements of the larynx itself, the mere abstract thought, the intellectual, is bypassed and one sees directly for the artistic impression on the stage in the silent language of eurythmy something sensual and supersensory: the soul-filled movements of the human being.

You will therefore see that this eurythmic art is particularly suitable for the experiment I have tried to carry out in my 'mystery dramas', where the spiritual itself is to be expressed in many places. What is actually meant here will, of course, be misunderstood for a long time yet, because people do not yet realize that nature and thus man, through his intellect, is being forced into abstract natural laws. We will just have to learn to understand nature in line with what Goethe means when he says: When man is placed at the summit of nature, he sees himself again as a whole nature, which in turn has to produce a summit. To do this, he rises to the challenge by permeating himself with all perfections and virtues, invoking number, order, harmony and meaning, and finally rising to the production of the work of art. Thus man creates within himself a new, significant summit and then rises to produce the work of art.

What must this work of art be like? We can only imagine it as an ideal. Perhaps we may say that when the human being regards himself with his whole organism as a tool, as the instrument for producing this work of art, it is indeed the case that, through the fact that this eurythmy appears in this particular form, something is present that perhaps – I am not saying that it is already this ideal art – but that it provides something from which one can see how one must create forms in order to arrive at the sensual-supersensible.

That is the essential thing: neither the sensual nor the supersensible alone, but the sensual-supersensible – the sensual-supersensible that appears to us as if the forms of the idea or of the ideational had already lived in us, and that appears to us with such vividness that we find the idea itself as something taking place in the sensory world. To bring the idea to the sensual, or to present the sensual world in the form of the idea: this is what can be brought about most vividly, precisely through this particular art form of eurythmy.

But I also ask you today to be lenient with what we can bring to you today, because, as I said, we are only just beginning. Those of you who have attended our performances more often may have noticed how we have been trying to make progress recently, but it must continue to happen more and more. Either we or others will be able to develop what is in its infancy today to a greater perfection. Be assured, my dear audience, that with eurythmy a beginning has been made to something that will surely one day be able to stand alongside other, older art forms as a complete art.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich auch heute wie sonst immer vor diesen eurythmischen Darbietungen einige Worte über die Bedeutung der eurythmischen Kunst vorausschicke. Ein Versuch dieser eurythmischen Kunst liegt vor, ein Anfang, könnte man sagen, eines Versuches zu einer Art stummen Sprache. Sie werden diese stumme Sprache ausgeführt sehen auf der Bühne in Bewegungen, die durch die menschlichen Glieder vollzogen werden - auch durch Bewegungen des ganzen Menschen im Raume - oder durch die Wechselbewegungen, durch die Wechselstellungen von Persönlichkeiten in Gruppen und dergleichen.

Alles das könnte man zunächst als eine bloße Gebärdenkunst ansehen, wo versucht wird, für einen dichterischen Inhalt, der da gerade zugrunde liegt und der auch dabei rezitiert wird, oder für etwas Musikalisches, das ebenso der Darbietung zugrunde liegen kann und das dabei gespielt wird, gesungen wird - es könnte so aussehen, als ob man durch Bewegungen Gebärden, eine gewisse Mimik hinzufüge zu dem, was als dichterischer Inhalt, wortwörtlicher Inhalt oder musikalischer Inhalt das Leitmotiv [bildet]. So ist es nicht, sondern mit dieser eurythmischen Kunst wird in der Tat versucht, eine neue Kunstquelle zu eröffnen und auch ganz besondere Kunstausdrucksmittel zu bringen. Das ist hier der Mensch selber. Und die Quelle, die eröffnet sich durch eine besondere Fortbildung desjenigen, was man im Sinne des Goetheanismus nennen kann: das Streben nach dem sinnlich-übersinnlichen Elemente in der Kunst.

Wir sehen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, heute die mannigfaltigsten Bestrebungen, aus den alten traditionellen Kunstformen herauszukommen, aus der alten Kunstsprache herauszukommen, und irgendetwas Neues als künstlerisches Ausdrucksmittel zu finden. Wir sehen das auf dem Gebiete der Plastik, der Malerei, auch auf dem Gebiete der Dichtung; auf dem Gebiete der Musik ist es seit lange bemerkbar und so weiter.

Es ist immer, wenn eine gewisse Zeit erfüllt ist, so, dass für die Kunst dieser Zeit die Formen zu stark intellektuell werden. Dasjenige, was im Anfange einer Kunstepoche noch intuitiv-instinktiv ist, was aus den elementarsten Emotionen des Menschen hervorgeht, das wird im Laufe der Zeit studiert, durch den menschlichen Verstand durchgehend, [wird] künstlerische Technik, die aber von dem Verstande durchdrungen ist. Und es nimmt sich dann das immer mehr als Epigonenkunst aus, als etwas, das wiederum eine junge Generation dann anwenden [ablehnen?] wird.

Heute sehen wir ganz besonders im Impressionismus und Expressionismus Versuche, zu einer neuen künstlerischen Formensprache zu kommen. Allein, trotzdem hier gar nichts gegen manche außerordentlich bedeutsame Anfänge in dieser Richtung eingewendet werden soll, muss doch auch gesagt werden, dass gerade die ernsthaftesten künstlerisch Schöpfenden und Genießenden auf diesem Gebiete eine gewisse Unbefriedigtheit haben. Zum Beispiel das Gebiet der Malerei genommen, wird es nicht möglich, gewisse elementare Erlebnisse bloß heraufzuholen - ich möchte sagen halb Diener der menschlichen Natur, die auf die Leinwand gebracht werden soll -, wirklich in Farben und in Linien sachgemäß auszudrücken. Dasjenige, was bei jeglicher Kunst als besondere Schwierigkeit vorliegt, ist ja, dass ertötend, erläihmend wirkt auf alles Künstlerische das intellektuelle Element in dem Maße, als Gedanken, als Vorstellungen, überhaupt Intellektuelles in das Künstlerische hereinkommt. Das Künstlerische wird ertötet. Deshalb meinte auch Goethe gerade für das Künstlerische besonders, dass der Ausdruck Sinnlich-Übersinnliches angemessen ist. Unmittelbar muss da sein irgendetwas, was in der AuRenwelt als Ausdrucksmittel dienen kann. Aber in dem Augenblicke, wo diesem Ausdrucksmittel eingeprägt wird irgendeine Idee, hört das künstlerische Genießen auf. Und ich habe das Gefühl, dass man am leichtesten dann etwas Sinnlich-Übersinnliches zustande bringen kann, wenn man den Menschen selbst als Werkzeug für den künstlerischen Ausdruck benützt.

Dazu aber muss die menschliche Lautsprache eben auch sinnlichübersinnlich studiert werden. Dann, wenn der Mensch sich hörbar macht auch künstlerisch, nicht nur dichterisch, sondern zum Beispiel auch im Gesange, durch seine Stimmorgane, durch seine Lautorgane, dann liegen ja immer dem Ausdrucke dieser Lautorgane Bewegungen zugrunde, deren Tendenzen man untersuchen kann, wenn man die Möglichkeit hat, sich über die bloße sinnliche Beobachtung des Hörens zu erheben und hineinzudringen in dasjenige, was nicht unmittelbar gehört wird, sondern was als eine Bewegung zugrunde liegt, eine Bewegung des Kehlkopfes, eine Bewegung der sonstigen Organe, die es mit dem Sprechen oder mit dem Singen zu tun haben. Das Beseelte der menschlichen Sprache beruht ja darin, dass der Mensch seinen Muskelapparat lokalisiert auf den Kehlkopf, ihn dazu benützen kann, um Bewegungen hervorzubringen, die einfach durch ihre Eigentümlichkeit dann die Lautsprache werden. Diese Bewegungen kann man sinnlich-übersinnlich studieren. Man muss nur dann dasjenige, was durch die Organisation des Kehlkopfes und der anderen Lautorgane in Vibrationen der Luft übergeht, also ich möchte sagen auseinandergelegt wird in lauter kleine, vibrierende Bewegungen, das muss man in [sein]em großen Verlaufe studieren. Man muss intuitiv erfassen, welche Bewegungstendenzen da zugrunde liegen.

Dann lässt sich dasjenige, was man da studieren kann, was ganz gesetzmäßig der Sprache zugrunde liegt, das lässt sich übertragen auf den ganzen Menschen, auf die Bewegung aller seiner Glieder. Sodass Sie in der Eurythmie durch eine solche Übertragung auf der Bühne gewissermaßen den ganzen Menschen wie einen menschlichen Kehlkopf, möchte ich sagen, funktionieren schen. Man könnte sagen: Würden nicht diejenigen Bewegungen, die da ausgeführt werden für Vokale, Konsonanten, Satzzusammenhänge, für das innere Gepräge, für die Struktur des Satzes, dem diese Bewegungen entsprechen, nicht durch den ganzen Menschen ausgedrückt, sondern würde man das, was man da sieht, unmittelbar in den Kehlkopf hineinlegen, so würde eben im Kehlkopf nichts anderes zum Ausdruck kommen, als was Sie als begleitende Rezitation hören.

Allerdings dadurch ist das, was eurythmische Kunst ist, durchaus nicht etwas Willkürliches, sondern etwas so innerlich Gesetzmäßiges, wie das melodische oder harmonische Element in der Musik innerlich gesetzmäßig ist. Wenn irgendetwas zunächst an Gebärde oder Mimik zugrunde liegt, so ist das noch etwas nicht Überwundenes, [denn] in der Eurythmie lebt etwas so Gesetzmäßiges wie in der Musik selber. Und in dem, was gleichzeitig gehört wird, liegt etwas wie ein harmonisches Element in der Musik. [Das ist aber nur dadurch möglich, dass] man auch in der Dichtung zurückgeht auf dasjenige, was eigentlich Dichterisches ist. Dichtung ist ja nicht eine Kunst durch ihren wortwörtlichen Inhalt, gewissermaßen durch das Prosaische, das ihr zugrunde liegt, sondern die Dichtung ist Dichtung durch den Rhythmus, durch den Takt, durch alles dasjenige, was in den wortwörtlichen Inhalt erst als Form einverleibt wird.

Das ist es, was durch Eurythmie zum Ausdrucke kommt. Das muss aber auch in der die Eurythmie begleitenden Rezitation zum Ausdrucke kommen. Daher muss auch, um die Eurythmie rezitierend begleiten zu können, zurückgegangen werden zu den guten alten Formen der Rezitation, die man heute gerade da, wo man glaubt gut zu rezitieren, vermeidet: auf das Rhythmische, auf das TaktmäRige des Rezitierens [muss zurückgegangen werden], nicht auf die Betonung des Prosainhaltes, auf die heute ein so großer Wert gelegt wird in dem, was man gerade in unserer sehr unkünstlerischen Zeit gute Rezitation nennt. Auch da muss eben berücksichtigt werden, dass dieses Zurückgehen der Eurythmie auf ein neues künstlerisches Element ganz besondere Anforderungen auch an die Rezitationskunst stellt. Dadurch, dass mit dieser Eurythmie versucht wird, dem Menschen selbst einzuprägen dasjenige, was ihm sonst für das Hören eingeprägt wird in der Sprache, dadurch wird der Mensch selbst zum sinnlichen Ausdrucksmittel der Kunst. Und dadurch, dass die Bewegungen nicht verstandesmäßig in Gebärden gestaltet werden, sondern dass die Bewegungen so verlaufen, dass sie dem Menschen natürlich sind wie die Bewegungen des Kehlkopfes selber, dadurch wird der bloße abstrakte Gedanke, das Intellektuelle umgangen und man sieht unmittelbar für den künstlerischen Eindruck auf der Bühne in der stummen Sprache der Eurythmie etwas Sinnlich-Übersinnliches: die beseelten Bewegungen des Menschen.

Daher werden Sie sehen, dass diese eurythmische Kunst auch besonders gut zu gebrauchen ist [für den] Versuch, den ich gemacht habe in meinen «Mysteriendramen», wo an vielen Stellen das Geistige selbst zum Ausdruck kommen soll. Was da eigentlich gemeint ist, das wird ja in der Gegenwart noch viel Missverständnis finden, [da] man noch nicht einsieht, dass die Natur und also der Mensch durch seinen Verstand in abstrakte Naturgesetze hineingezwängt wird. Man wird eben die Natur entsprechend dem verstehen lernen müssen, was Goethe meint, wenn er sagt: Wenn der Mensch an den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, sieht er sich wieder als eine ganze Natur an, die in sich abermals einen Gipfel hervorzubringen hat. Dazu steigert er sich, indem er sich mit allen Vollkommenheiten und Tugenden durchdringt, Zahl, Ordnung, Harmonie und Bedeutung aufruft und sich endlich zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes erhebt. - Also der Mensch schafft in sich selbst einen neuen, bedeutsamen Gipfel und erhebt sich dann zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes.

Wie muss dieses Kunstwerk sein? Man kann es sich nur als Ideal vorstellen. Vielleicht darf man sagen: Wenn der Mensch sich nun selber mit seinem ganzen Organismus als Werkzeug, als das Instrument zur Hervorbringung dieses Kunstwerkes betrachtet, so ist es doch so, dass tatsächlich dadurch, dass diese Eurythmie in dieser besonderen Form auftritt, etwas vorhanden ist, das vielleicht - ich will durchaus nicht sagen, dass sie schon diese Idealkunst ist -, dass sie etwas liefert, aus dem man ersehen kann, wie man Formen schaffen muss, um zu Sinnlich-Übersinnlichem zu kommen.

Das ist das Wesentliche: Weder allein das Sinnliche noch das Übersinnliche, sondern das Sinnlich-Übersinnliche - Sinnlich-Übersinnliches, das uns so erscheint, als hätten schon die Formen der Idee oder des Ideellen in uns gelebt, und das mit solcher Anschaulichkeit uns gegenüber auftritt, dass wir die Idee selber wie etwas in der Sinneswelt Sich-Abspielendes finden. Die Idee bis zum Sinnlichen gebracht, oder die sinnliche Welt in Form der Idee dargestellt: Das ist dasjenige, was wohl am anschaulichsten hervorgebracht werden kann gerade durch dieses besondere Kunstgebiet der Eurythmie.

Aber ich bitte Sie auch heute, Nachsicht zu üben gegenüber dem, was wir Ihnen heute schon bringen können, denn wir sind, wie gesagt, erst im Anfange. Diejenigen der verehrten Zuschauer, die öfter unsere Darbietungen besucht haben, werden vielleicht bemerken können, wie wir gesucht haben in der letzten Zeit, einen Fortschritt zu erzielen, der aber noch weiter und immer weiter sich ergeben muss. Es wird entweder durch uns oder durch andere dasjenige, was heute im Anfange ist - wahrscheinlich [durch] andere - zu größerer Vollkommenheit erhoben werden können. Seien Sie überzeugt, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass mit der Eurythmie aber ein Anfang gegeben ist zu etwas, was sicher einmal als vollkommene Kunst neben andere, ältere Kunstformen wird hintreten können.