The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

17 July 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

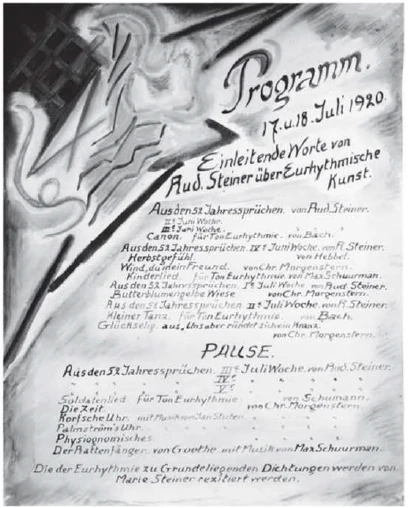

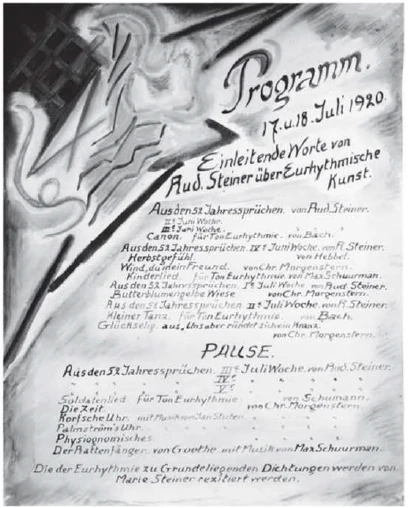

>72. Eurythmy Performance

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen.

Today, we will again take the liberty of presenting you with a few samples of the eurythmic art we have inaugurated. As usual before these performances, allow me to introduce them with a few words. I do this not because I intend to explain what you are about to see on stage, but because what you are about to see aspires to be real art. Real art, of course, needs no explanation, but must speak for itself, must immediately make the impression that is intended with it, must appear directly. But I must say a few words in advance about the sources and the whole way in which this art was found. For it is an art that is only just beginning, that will only come to the stage where the laws work as something self-evident - for example in music - through further development. We are under no illusion that what we can already try today is just the beginning.

If I am to express the essence of this art in a few words, I would say: it is a kind of language, but a language that does not come about in the usual way that a person speaks with his speech organs in the phonetic language , but rather it is a language that works through visible movement, which either one person performs on himself or groups of people perform together in space and the like, thus a kind of mute, visible language, performed by the whole person.

All this is fundamentally based on the development of a Goethean concept of art, like everything that is attempted here, or is attempted within the movement for which this Dornach building is intended to be the representative, the external representative. Like everything, this too is based on a further development of Goetheanism - whereby Goethe is not what he was when he died in 1832, but what he is in the living, spiritual movement to this day, in the artistic principles, in the cognitive and spiritual principles in general, which are in his sense.

It may look abstract, but I am being very specific and factual when I recall what Goethe actually meant by his theory of metamorphosis. This theory is still not sufficiently understood today. It will only be fully appreciated in its full scope and depth when our views on true science have changed from those of today, which are still rooted in materialism. It may sound simple when Goethe says: If I take a single plant leaf, then everything that makes up the whole plant is present in this single leaf, only various aspects — the ramification of the plant, the formation of the flowering part, the fruit part, and so on — are not visibly expressed in the leaf, but are, so to speak, within the leaf in thought. What is visible in the leaf is much less than what is present in the thought in each individual leaf, so that each individual plant leaf – simply formed – is the whole plant. And again, that the whole plant is nothing more than a complex leaf. As I said, once the full scope of what Goethe suggests for plant life, and what he has also developed in a certain sense for the animal kingdom, has been thought through and researched, it will make a significant impression on all spiritual life.

We are trying to implement here what Goethe merely applied to the form of organic growth, the growth of living beings; we are trying to apply it – albeit transformed into the artistic – in our eurythmic art by studying. All that is contained in the art of eurythmy is based on a deep spiritual study of the underlying movement tendencies of the larynx and all neighboring organs that come into play when speaking. Not the individual vibrations that then pass into the air and convey the sound that I am speaking to you now, for example, and that reaches your ear, but the large, comprehensive movements, which are clearly evident in the configuration of the vocal cords and the configuration of the other organs that come into play when speaking. All this had to be carefully studied. These movements, which one gets to know, if I may again make use of Goethe's expression, through sensual-supersensory observation, are then transferred to the whole person, so that the person expresses through his arm movements, through the movement of his whole body, what the larynx and its neighboring organs want to carry out.

Just as Goethe takes the whole plant, like a complicated designed leaf, so too is what a single person or groups of people present on the stage in front of you, it is a transformation of the larynx and other speech-organ movements. In the people and groups of people who appear before you, you see, I would say a moving larynx. The whole human being becomes a moving larynx. It is only natural that not everything is immediately comprehensible, since this art is in its infancy. But just think of when you hear a language you do not understand, it is also not immediately comprehensible to you. And if you are also to receive artistic and poetic elements in the language, it is not immediately comprehensible either. Eurythmy will only gradually develop into a self-evident impression. But those who have artistic feeling will already be able to see the movements that are performed as a kind of moving language or moving music. All it takes is a little artistic intuition.

However, as eurythmy is emerging, it must strive, I would say, in our truly art-poor time, in the time when there is so little real artistic sense, it must strive to deepen this artistic sense. If you listen to things today, it is really the case, ladies and gentlemen, that you have to say that ninety-nine percent of everything that is written today is written completely unnecessarily, and only one percent of it really arises from artistic inwardness. Because it is not the prosaic content, the literal content, that makes a poem artistic, but only the form, either the musical background or the plastic-pictorial background.

The times are actually over, but they must come again, when the romantics found it particularly satisfying to listen to poems in foreign languages, when they did not understand the content at all, but only the rhythm, only the musicality, in order to delve only into the musicality, into the formal of the artistic creation that underlies poetry. We must come back to this, to understanding correctly, in turn, what it actually means when one becomes aware that Schiller did not initially have the literal content of his most important poems at all – that was of no great importance to him at first. There was something vaguely melodious in his soul, and one poem or another could arise from it later. It was only later that the prose content was added – that is the unartistic aspect of the content. The actual artistic aspect, that is, the rhythmic, the metrical, the melodious, or even the plastic, is what is actually artistic about the poetry. So you will notice that when we perform poetic eurythmy, we do not strive for pantomime, for anything mimetic. If it still occurs today, it is only because we are just at the beginning of the eurythmic art and must strip away all physiognomic, mimetic and other aspects in eurythmy. That is another imperfection. Insofar as it occurs today, it will be discarded later.

What is important is that what the poet himself does artistically in the formation of the verses, in the rhythm and so on, is also grasped in the flowing out of the eurythmic. So that it is not a matter of asking: how does a eurythmic movement express this or that? but rather: how does the eurythmic movement properly follow the preceding movement, how does the third follow the other two and so on, so that one really has a musical art unfolding in space. Therefore, on the one hand, you will see that what is to be eurythmized is recited, and on the other hand, you will hear something musical. And on stage you will see only human movements, in which either the musical or the poetic is realized.

I would like to point out that in this way, the art of recitation must in turn be pushed out of the non-art in which it is actually included today. This art of recitation is, of course, regarded as particularly perfect today when the reciter pays particular attention to the literal content, to the prose, to that which is expressed through poetry. And one is particularly satisfied when the reciter, the declaimer, as one says, expresses the prose content quite inwardly. It cannot be expressed in the same way as it is striven for in today's inartistic culture. If you want to practise eurythmy after reciting, the reciter must also respond to the rhythmic, the musical or the plastic-picturesque aspects of the poetry. So that precisely what is neglected today must also come to the fore in recitation.

During the course of this evening, you will also see children perform. I would like to draw particular attention to the fact that these children's performances already play a major role in the curriculum of our Stuttgart Waldorf School – as a supplement to purely mechanical gymnastics through the art of eurythmy for children. I would like to say that what otherwise appears as art is inspired gymnastics. A later time, which thinks more impartially than today about spiritual progress, spiritual human needs and so on, will think quite differently about these things than we do today. Today, of course, children do gymnastics as the physiological, the purely mechanical laws require. But no consideration is given to the human being as a whole; only the human being as a physical being is taken into account. When our children perform movements that are also movements of the eurythmic art, the whole human being is set in motion in body, soul and spirit. And the effect of this is that - if it is introduced to children at the right age in a fully curriculum-based way, as we do in the Waldorf School in Stuttgart - then not only what gymnastics brings about is brought about, but much more. Today, this is not believed because the whole spirit of thinking is materialistic. Gymnastics certainly has many good things. But what eurythmy can bring out in children and what gymnastics cannot do is develop initiative of the will, independence of the soul life. This comes from the soulfulness of the movements, which is not present in mere gymnastics.

So what we do as eurythmy has, firstly, an essentially artistic significance, but secondly, it also has a pedagogical-didactic significance. And I could talk about a third significance, a hygienic one, but I do not want to today. Because what is done in eurythmy has something essentially healing about it, this hygienic aspect can provide essential practical support in cases of illness. Unfortunately, the time available to me here is not enough to go into more detail.

In any case, what might be called the following should come to light in eurythmy: The human being attempts to express through outward movement what lies within him in the way of movement possibilities. In this way we have something truly spiritualized and ensouled, something that can be directly perceived by the senses in its spiritualized and ensouled form. We have nature, for the whole human being stands before us as nature. But we have ensouled nature, for it is the human being who performs these natural movements. We have, in the most eminent sense, the human mystery expressed in the movements of the will, so that when the human being is the instrument in the art of eurythmy, Goethe's beautiful saying is truly fulfilled: When man is placed at the summit of nature, he brings forth a whole nature within himself, takes order, harmony, measure and meaning together and rises to the production of the work of art. And in eurythmy, he takes his own movement possibilities, his form, everything available to him, and brings order, harmony, measure and meaning together to express what is in his soul.

I believe that what Goethe longed for so much in art, namely that it is at the same time an unraveling of the great secrets of nature, comes to expression in a eurythmic performance, because Goethe says: “When nature begins to reveal its manifest secret to someone, that person feels a deep longing for its most worthy interpreter, art. Art is something that Goethe, like every true human being, thinks of in intimate connection with the secrets of the world.

But I ask you to bear with me on this, as far as we can demonstrate it in rehearsals today, for we ourselves know very well that everything is still in its infancy, and perhaps only the attempt at a beginning. But anyone who looks at the essence of this eurythmic art and is active in it must be convinced that what it is at the beginning is capable of being perfected, which will one day – perhaps through our own efforts, but more likely through those of others – enable this youngest of the arts to stand fully equal with the older, more established ones.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Wir werden heute uns wiederum erlauben, Ihnen einige Proben aus der von uns inaugurierten eurythmischen Kunst vorzuführen, und es sei mir gestattet - so wie sonst vor diesen Aufführungen -, mit einigen Worten sie einzuleiten. Nicht geschieht das, weil ich dasjenige, was Sie auf der Bühne sehen sollen, irgendwie zu erklären gedenke, denn dasjenige, was Sie sehen werden, will wirkliche Kunst sein. Wirkliche Kunst bedarf selbstverständlich keiner Erklärung, sondern muss durch sich selbst sprechen, muss unmittelbar den Eindruck machen, der mit [ihr] beabsichtigt ist, muss unmittelbar auftreten. Aber über die Quellen und über die ganze Art und Weise, wie diese Kunst gefunden worden ist, muss ich einiges vorausschicken. Denn es handelt sich ja um eine Kunst, die erst ganz im Anfange ist, die erst in weiterer Entwicklung gewissermaßen zu dem Stadium kommen wird, wo die Gesetze wie etwas Selbstverständliches - zum Beispiel bei der Musik - wirken. Wir geben uns keiner Täuschung darüber hin, dass wir mit dem, was wir heute schon versuchen können, eben durchaus einen Anfang erst haben.

Soll ich nun mit wenigen Worten das Wesentliche dieser Kunst zum Ausdrucke bringen, so möchte ich sagen: Es handelt sich um eine Art von Sprache, aber eine Sprache, die nur nicht auf die gewöhnliche Weise zustande kommt, wie der Mensch mit seinen Sprachorganen in der Lautsprache spricht, sondern es handelt sich um eine Sprache, die durch die sichtbare Bewegung wirkt, die entweder ein Mensch an sich ausführt oder die Menschengruppen zusammen im Raume ausführen und dergleichen, also um eine Art von stummer, sichtbarer Sprache, ausgeführt durch den ganzen Menschen.

Das alles beruht im Grunde auf einer Ausbildung eines Goethe’schen Kunstgedankens, wie alles dasjenige, was hier versucht wird, beziehungsweise innerhalb derjenigen Bewegung versucht wird, für welche dieser Dornacher Bau der Repräsentant, der äußere Repräsentant sein soll. Wie alles, so beruht auch das auf einer weiteren Ausgestaltung des Goetheanismus - wobei uns Goethe nicht dasjenige ist, als was er 1832 gestorben ist, sondern dasjenige, als was er in der lebendigen, geistigen Bewegung bis heute fortlebt, fortlebt in denjenigen Kunstprinzipien, in denjenigen Erkenntnis- und geistigen Prinzipien überhaupt, die in seinem Sinne gehalten sind.

Es sieht abstrakt aus, aber es ist sehr konkret und tatsächlich gemeint, wenn ich erinnere an dasjenige, was Goethe mit seiner Metamorphosenlehre eigentlich gemeint hat. Diese Metamorphosenlcehre, die ist ja heute noch immer nicht genügend verstanden. Sie wird einmal - wenn man über wahre Wissenschaft andere Anschauungen haben wird als die heutigen, noch immer aus dem Materialismus gewordenen sind - erst in ihrem vollen Umfange, in ihrer vollen Tiefe gewürdigt werden. Es sieht einfach aus, wenn Goethe sagt: Nehme ich ein einzelnes Pflanzenblatt, so ist in diesem einzelnen Blatt alles dasjenige gegeben, was die ganze Pflanze ist, nur kommt Verschiedenes - Verästelung, Verzweigung der Pflanze, die Bildung des Blütigen, des Fruchthaften und so weiter - nicht sichtbarlich im Blatte zum Ausdruck, sondern es ist gewissermaßen im Blatte dem Gedanken nach drinnen. Das Sichtbare im Blatte ist viel weniger, als dasjenige, was dem Gedanken nach in jedem einzelnen Blatte vorhanden ist, sodass jedes einzelne Pflanzenblatt - einfach gestaltet — die ganze Pflanze ist. Und wiederum, dass die ganze Pflanze nichts anderes als ein kompliziertes gestaltetes Blatt ist. - Wie gesagt, wenn das einmal in seinem ganzen Umfange durchdacht, durchforscht sein wird, was da Goethe andeutet für das Pflanzenleben, was er in gewissem Sinne auch für das Tierreich ausgeführt hat, so wird das auf das ganze geistige Leben einen bedeutsamen Eindruck machen.

Wir versuchen hier umzusetzen dasjenige, was Goethe bloß auf die Form des organischen Wachstums, des Wachstums der Lebewesen angewendet hat, wir versuchen es anzuwenden - allerdings ins Künstlerische umgewandelt - in unserer eurythmischen Kunst, indem wir studieren. All dasjenige, was eurythmische Kunst ist, beruht wirklich auf einem tiefen geistigen Studium, indem studiert worden ist, welches die Bewegungstendenzen sind, die zugrunde liegen dem Kehlkopf und allen Nachbarorganen des Kehlkopfes, die beim Lautsprechen in Betracht kommen. Nicht die einzelnen Vibrationen, die dann in die Luft übergehen und den Ton vermitteln, den ich zum Beispiel jetzt zu Ihnen spreche und der an Ihr Ohr dringt, sondern die großen, zusammenfassenden Bewegungen, die aber deutlich veranlagt sind in der Konfiguration der Stimmbänder, in der Konfiguration der anderen Organe, die beim Sprechen in Betracht kommen. Das alles musste sorgfältig studiert werden. Diese Bewegungen, die man da kennenlernt, wenn ich mich des Goethe’schen Ausdruckes wiederum bedienen darf, durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen, diese Bewegungen werden dann auf den ganzen Menschen übertragen, sodass der Mensch durch seine Armbewegungen, durch die Bewegung seines ganzen Leibes dasselbe im Grunde ausdrückt, was ausführen will der Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane.

Es ist also, so wie Goethe die ganze Pflanze wie ein kompliziertes veranlagtes Blatt nimmt, so ist dasjenige, was hier auf der Bühne ein einzelner Mensch oder Menschengruppen vor Ihnen darstellen, es ist Umgewandeltes vom Kehlkopf und sonstigen sprachorganischen Bewegungen. In dem Menschen und in den Menschengruppen, die vor Ihnen auftreten, sehen Sie, ich möchte sagen einen bewegten Kehlkopf. Der ganze Mensch wird zum bewegten Kehlkopf. Nur natürlich, da diese Kunst am Anfange ist, so ist nicht alles gleich verständlich. Aber bedenken Sie nur, wenn Sie eine Ihnen unbekannte Sprache hören, so ist sie Ihnen auch nicht gleich verständlich. Und wenn Sie dann auch noch Künstlerisches in der Sprache, Dichterisches in der Sprache empfangen sollen, so ist es auch nicht gleich verständlich. Eurythmie wird sich also erst allmählich zum selbstverständlichen Eindruck durchringen. Aber derjenige, der künstlerisches Empfinden hat, wird schon heute diejenigen Bewegungen, die ausgeführt werden, wirklich als eine Art bewegter Sprache oder bewegter Musik ansehen können. Man braucht dazu nur einige künstlerische Intuition.

Allerdings, indem die Eurythmie so auftritt, muss in ihr angestrebt werden, ich möchte sagen in unserer ja wirklich kunstarmen Zeit, in der Zeit, in der so wenig wirklich künstlerischer Sinn vorhanden ist, es muss gerade angestrebt werden, diesen künstlerischen Sinn zu vertiefen. Hört man heute die Dinge, es ist ja wirklich so, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass man sagen muss, neunundneunzig Prozent alles desjenigen, was heute gedichtet wird, ist vollständig unnötig gedichtet, und nur ein Prozent davon ist wirklich aus künstlerischer Innerlichkeit heraus entsprungen. Denn an einem Gedicht ist ja nicht dasjenige Kunst, was prosaischer Inhalt ist, wortwörtlicher Inhalt ist, sondern an einem Gedicht ist nur so viel Kunst, als darinnen Form ist, entweder musikalischer Untergrund oder plastisch-bildhafter Untergrund.

Die Zeiten sind eigentlich vorüber, aber sie müssen wieder kommen, wo die Romantiker es als eine besondere Befriedigung empfanden, Gedichte in fremden Sprachen anzuhören, wo sie gar nicht den Inhalt verstanden, sondern nur den Rhythmus, nur das Musikalische verstanden, um sich so nur in das Musikalische, in das Formale des künstlerischen Schaffens, das der Dichtung zugrunde liegt, hinein zu vertiefen. Dazu müssen wir wiederum kommen, richtig zu verstehen wiederum, was es eigentlich heißt, wenn man aufmerksam darauf wird, dass Schiller bei den bedeutendsten seiner Gedichte zunächst gar nicht den wortwörtlichen Inhalt hatte - der war ihm zunächst höchst gleichgültig. Er hatte so etwas unbestimmt Melodiöses in der Seele liegen, und da konnte das eine oder andere Gedicht später noch daraus werden. Das kam erst später dazu, was der Prosainhalt ist — das ist das Unkünstlerische am Inhalt. Das eigentlich Künstlerische, also das Rhythmische, Taktmäßige, Melodiöse oder auch das Plastische, das ist dasjenige, was auch an der Dichtung das eigentlich Künstlerische ist. Sodass Sie bemerken werden: Wenn wir dichterische Eurythmie darstellen, so streben wir keine Pantomime, nichts Mimisches an, sind weit entfernt davon. Wenn es heute noch auftritt, so ist das nur, weil wir eben im Anfang der eurythmischen Kunst stehen und eben abstreifen müssen im Eurythmischen Physiognomisches, Mimisches und so weiter. Das ist noch eine Unvollkommenheit. Soweit es heute auftritt, wird es schon später abgestreift werden.

Es handelt sich gerade darum, dass dasjenige, was der Dichter selber als Künstlerisches in der Formung der Verse, in dem Rhythmus und so weiter macht, dass das auch aufgefasst wird in dem Fortströmen des Eurythmischen. Sodass es nicht darauf ankommt zu sehen: Wie drückt eine eurythmische Bewegung dies oder jenes aus? - sondern: Wie fügt sich die eurythmische Bewegung anständig an die vorausgehende Bewegung, wie die dritte an die zwei anderen und so weiter, sodass man wirklich eine im Raume vor sich gehende musikalische Kunst hat. Daher werden Sie auf der einen Seite sehen, dass dasjenige, was eurythmisiert werden soll, rezitiert wird, und auf der anderen Seite werden Sie Musikalisches hören. Und auf der Bühne werden Sie eben nur in menschlichen Bewegungen, in die Bewegungskunst umgesetzt entweder das Musikalische oder das Dichterische sehen.

Ich darf darauf aufmerksam machen, dass dabei auch die Rezitationskunst wiederum herausgchoben werden muss aus jener Unkunst, in der sie heute eigentlich drinnen steckt. Diese Rezitationskunst wird ja heute als besonders vollkommen angesehen, wenn der Rezitierende auf den wortwörtlichen Inhalt, auf die Prosa, auf dasjenige, was ausgesprochen wird durch die Dichtung, besonders sieht. Und man ist dann ganz besonders zufrieden, wenn der Rezitator, der Deklamator so, wie man sagt, recht innerlich den Prosainhalt zum Ausdruck bringt. Den kann man gar nicht zum Ausdrucke bringen in derselben Form, wie er in der heutigen Unkunst angestrebt wird. Wenn man nach dem Deklamierten die eurythmische Kunst ausüben will, da muss der Rezitierende auch durchaus eingehen auf das Rhythmische, auf das Musikalische oder auf das Plastisch-Malerische der Dichtung sogar. Sodass also gerade dasjenige, was heute vernachlässigt wird, auch in der Rezitation zum Vorschein kommen muss.

Sie werden im Verlaufe unseres heutigen Abends auch Kinder darstellen sehen. Da darf ich wohl besonders darauf aufmerksam machen, dass ja diese Kinderdarstellungen schon eine große Rolle im Lehrplan unserer Stuttgarter Waldorfschule spielen - als Ergänzungen des rein äußerlich mechanischen Turnens durch die eurythmische Kunst bei den Kindern. Da ist, ich möchte sagen dasjenige, das sonst als Kunst auftritt, beseeltes Turnen. Über diese Dinge wird ja eine spätere Zeit, die unbefangener als die heutige denkt, denken wird über geistige Fortschritte, geistige Menschheitserfordernisse und so weiter, durchaus anders denken, als man heute denkt. Heute wird ja zunächst so geturnt von den Kindern, wie es die physiologischen, die rein mechanischen Gesetze erfordern. Aber da wird nicht Rücksicht genommen auf den Menschen als ganzes Wesen, da kommt nur der Mensch als physisches Wesen in Betracht. Wenn bei uns die Kinder Bewegungen ausführen, die zu gleicher Zeit die Bewegungen der eurythmischen Kunst sind, so kommt der ganze Mensch nach Leib, Seele und Geist in Bewegung. Und das wirkt so, dass - wenn es im richtigen Alter an die Kinder ganz lehrplanmäßig herangebracht wird, wie wir das in der Waldorfschule in Stuttgart tun -, dass dann nicht nur dasjenige, was das Turnen heranerzieht, heranerzogen wird, sondern dass viel mehr heranerzogen wird. Heute glaubt man es nicht, weil eben heute der ganze Geist des Denkens materialistisch ist. Das Turnen hat ja gewiss mancherlei Gutes. Was aber die Eurythmie bei den Kindern schon hervorbringen kann und was das Turnen nicht kann, das ist Willensinitiative, das ist Selbständigkeit des Seelenlebens. Das kommt von der Beseeltheit der Bewegungen, die nicht da ist beim bloßen Turnen.

So hat dasjenige, was wir als Eurythmie treiben, erstens im Wesentlichen eine künstlerische Bedeutung, zweitens aber auch eine pädagogisch-didaktische Bedeutung. Und ich könnte noch von einer dritten Bedeutung reden, von einer hygienischen, will es aber heute nicht. Weil dasjenige, was in der Eurythmie von dem Menschen ausgeführt wird, etwas wesentlich Gesundendes hat, so kann diese hygienische Seite eine wesentliche praktische Unterstützung in Krankheitsfällen bilden. Um das Genauere auszuführen, reicht ja die Zeit in den paar einleitenden Worten, die mir hier zur Verfügung steht, leider nicht aus.

Jedenfalls soll in der Eurythmie das zutage treten, was man nennen könnte: Der Mensch versucht dasjenige, was in ihm an Bewegungsmöglichkeiten liegt, zur äußeren Darbietung zu bringen. Dadurch haben wir wirklich etwas Durchgeistigtes, Durchseeltes, etwas, was als Durchgeistigtes und Durchseeltes unmittelbar sinnlich anschaulich ist. Wir haben Natur, denn der ganze Mensch steht als Natur vor uns. Aber wir haben durchseelte Natur, denn der Mensch ist es, der diese natürlichen Bewegungen ausführt. Wir haben im eminentesten Sinne dasjenige, dass uns das Menschengeheimnis ausgedrückt wird in den Bewegungen des Willens, sodass wirklich, wenn der Mensch selber das Instrument in der eurythmischen Kunst ist, erfüllt ist das schöne Goethewort: Wenn der Mensch an den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, bringt er in sich selber wiederum eine ganze Natur hervor, nimmt Ordnung, Harmonie, Maß und Bedeutung zusammen und erhebt sich zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes. - Und in der Eurythmie nimmt er aus seinen eigenen Bewegungsmöglichkeiten, aus seiner Gestalt, aus allem, was ihm zur Verfügung steht, Ordnung, Harmonie, Maß und Bedeutung zusammen, um auszudrücken, was sein Seelisch-Inneres ist.

Es kommt das, glaube ich, gerade bei einer eurythmischen Darbietung zum Ausdrucke, was Goethe von der Kunst so sehr ersehnte, dass sie zu gleicher Zeit eine Enträtselung ist der großen Naturgeheimnisse, denn Goethe sagt: Wem die Natur ihr offenbares Geheimnis zu enthüllen beginnt, der empfindet eine tiefe Sehnsucht nach ihrer würdigsten Auslegerin, der Kunst. Die Kunst ist etwas, was Goethe - wie jeder echte Mensch - in innigem Zusammenhange mit den Weltgeheimnissen denkt.

Das alles bitte ich aber, soweit wir das heute schon in Proben vorführen können, mit Nachsicht aufzunehmen; denn wir wissen selber sehr gut, dass alles noch im Anfange steht, vielleicht auch erst der Versuch eines Anfanges ist. Aber wer auf das Wesen dieser eurythmischen Kunst hinschaut und in ihr tätig ist, er muss die Überzeugung haben, dass dasjenige, was sie am Anfang jetzt erst ist, dass das einer Vervollkommnung fähig ist, die es einstmals - vielleicht noch durch uns selbst, aber wahrscheinlich durch andere - dahin bringen wird, dass diese eurythmische Kunst als die jüngste sich neben die älteren, eingebürgerten Künste voll ebenbürtig hinstellen kann.