The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

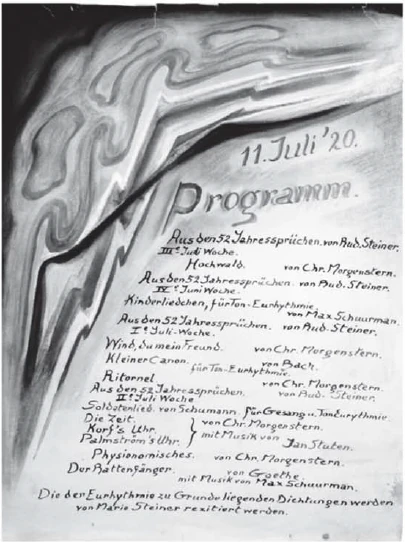

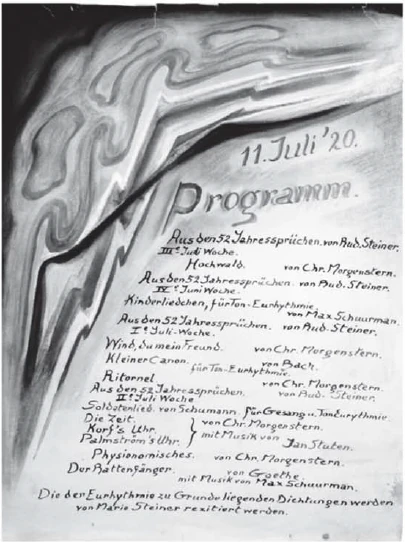

11 July 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

71. Eurythmy Performance

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen, The art of eurythmy, of which we would like to give you a small sample here today, attempts to penetrate to the very sources of human artistic creation in a certain way, unlike certain other arts that can easily be confused with it - dance or other mimic arts. It seeks to achieve this through very special artistic means. And because it is necessary to say a few words about this so that the essence of this artistic direction can be grasped, I will send these words ahead – not to explain the performance itself, which would of course be an inartistic undertaking. For art must speak for itself in the immediate impression it makes.

What you will see on the stage resembles a kind of gesture performed by the whole human being. But it is not, and one would judge eurythmy quite wrongly if one thought that the movements that come about either through the individual human being or through human groups are mere gestures that are supposed to express what is to be presented either on the one hand musically or on the other hand poetically or recitatively. Eurythmy wants to be a real visible language, it wants to reveal in plastic movement exactly the same as the human larynx and its neighboring organs can reveal through sound.

If one wants to understand the essence of eurythmy, one must look at its sources. It is the observation, both sensory and supersensible, of the movement tendencies expressed by the human larynx and all that is connected with the speech organs when speech sounds are uttered. This does not refer to the movements that pass into the outer air as direct tremulous movements, as vibrations, but to the movements that underlie these tremulous movements as movement tendencies. Movements that, organically, want to do more than they actually do. But the sensory-supersensory gaze – to use this Goethean expression – can observe these movements and then transfer them to the whole person according to the principle of metamorphosis. Just as Goethe, when he named the whole plant in its complexity a leaf multiplied in its individual subdivisions, actually saw only a leaf that had become more complicated, so what you see on the stage as a whole human being, like a larynx on the stage is, in fact, a transformation of what is naturally ignored when we simply listen to human speech, but which can be observed through sensory-supersensory observation as movements, as an inner eurhythmy of the speech organs. This is transferred to the whole human being. The individual movements that a person performs or that groups of people perform are therefore to be judged in exactly the same way as human speech itself according to the inner laws.

Now, if you look at what is being presented superficially, you would think that you were dealing with pantomime or facial expressions. On the other hand, it can be said that when we speak, we sometimes feel compelled to support our speech with gestures. When do we do that? We only do that when we feel that we are subjectively pursuing something that is more or less fully expressed in speech. But what is present in actual eurythmy is just as objective as what is expressed in language; all gesturing is excluded from it, all mere pantomime and mime is excluded from it. This can now be considered in the same way as it is considered for ordinary language.

On the one hand, we can say that eurythmy is so much an inner, visible language with its own laws that when two people or two groups of people perform the same poem in completely different places, the individual differences are no greater than when two pianists play the same sonata. That is one way of looking at it. But you could also say: you can distinguish between two pianists playing the same piece based on their individual nuances – and the same will be true for individual eurythmists or groups of eurythmists. In this way, what is subjectively incorporated into the gesture will be connected in a nuanced way with what is an objective law.

So in this visible language of eurythmy, we have something before us, not in the individual gesture, not the expression of something that lives literally in the soul, but we have in the individual eurythmic movement in which the whole human being feels as he feels in a single sound or word or word context, as he feels in spoken language. And what is effective is not that it expresses something in the soul as an individual element, but that one movement is linked to the next, creating a sequence of movements, just as a sequence of sounds is created in speech. Exactly the same way as it is in music, where we also have an inner, lawful movement in the succession of tones, in eurythmy such an inner movement comes to light, so to speak, as inner plastic music.

This enables us to extract from a poem – and in addition to the musical aspect, there will also be poems that are recited to accompany the eurythmy – the eurythmy merely expresses in silent, moving language what is expressed in the recitation in spoken language. We have the opportunity to express what concerns the whole human being, what is not expressed in the conventional or in mere thought expression - the inartistic in poetry. We have the opportunity to express the whole feeling and will, the whole personality of the human being as if in a large, moving larynx.

To do this, however, it is necessary, and this must be mentioned again and again, that one must return to the actual artistic element of poetry. Our time is essentially unartistic, and it is therefore very common today to perceive what is literally the content as the essential thing about the poetic art. In contrast to this, it must be said again and again that Schiller, for example, had an indeterminate melody alive in his soul, and from this indeterminate melody anything could become, whether it was “The Diver” or “The Fight with the Dragon” or anything else - that only emerged later. The essential thing for Schiller was not the literal content, [gap in the text] not the prose that is in the poem, but the important thing was the rhythm, the beat, the musicality, the plasticity, the imagery.

Today, people love an art of recitation that actually no longer has much to do with artistry, but sometimes with human sentimentality, with human goodwill to express this or that inwardly – although it always remains a phrase or sentimentality. But what real recitation is, can still be found in older times. Goethe rehearsed his Iphigenia with his actors with a baton, not so much going into the content as into the way the iambic went. This literal recitation could not be juxtaposed with eurythmy as an accompanying art, but one must also go into the eurythmic aspect of speaking itself. And so here one must recite as the good old artists of yore recited.

All this shows that with this eurythmy something is being striven for that wants to establish itself as a new element in our whole spiritual movement, a piece of Goetheanism. Goethe characterized so beautifully what eurythmy can achieve, even if only in a very limited area. Goethe spoke of how man, when he sees himself at the summit of nature, in turn feels himself to be a whole nature and takes in harmony, measure and meaning, and finally rises to the production of a work of art.

This production of the work of art comes to life, I would say, most fully when the human being, in the realm in which he sees eurythmy, makes himself an artistic tool for what he has to represent. Then this microcosm, this small world, as the human being presents it, as he brings it before us, is really not conceived of as a collection of arbitrary elements for the expression of the subjective, which comes to expression in the gesture, in the facial expression. Rather, what is inherent in him from his entire integration into the world, that is to be said with regard to the artistic aspect of eurythmy. And first and foremost, eurythmy should be something artistic.

But alongside this – and you will see a small sample of this in the children's eurythmy that we will present to you in the second part, along with some humor – there is also the didactic-pedagogical significance of this eurythmic art. It is certainly something significant when one introduces children to this eurythmy, because one can understand this eurythmy in a pedagogical-didactic sense as a kind of soul gymnastics. There will come times when people will think more objectively about these things than we do.

In more recent times, gymnastics have been seen as a particular benefit for young people, and rightly so. However, this is not to be criticized. An important authority told me some time ago that he does not consider gymnastics to be an educational tool, but rather a barbarism. I do not wish to go that far. But it is clearly appropriate in our time and demanded by life that this soul-based gymnastics of eurythmy is of educational and didactic significance for children. The strength of the soul, willpower, is what can be developed through this soulful gymnastics, while ordinary gymnastics - only because it looks at the human being from the point of view of physiology, only for the body that performs certain movements - can provide some help for skill.

For example, this spiritualized gymnastics, eurythmy, is being introduced at the Waldorf School in Stuttgart, which was founded by Emil Molt. This provides an essential didactic and pedagogical element. And in many other respects, it will be seen that this eurythmy can perhaps give the people of the present age what cannot come from any other source. What people thought of before this war broke out! They thought of staging the Olympic Games. It is just as if, at a certain age, people were given not what is good for them, but something that is good for a completely different age. Today, everything is seen only in the abstract and intellectually, in terms of current affairs, and not in terms of effect. The Olympic Games were a natural thing for what people needed in that age. Today we need something quite different from the Olympic Games. Today we need something that also places the human being in the whole world context in a soul-spiritual way. And so the Olympic Games and all the ideas that aim at something similar are nothing more than a certain dilettantism in relation to human cultural development.

What is attempted in eurythmy is, however, only a modest beginning, and I must keep pointing this out. But it is what is truly called for by the immediate present, by the demands of our time. And so it may be said that, on the one hand, the esteemed audience must be asked to regard what we are now able to present as really only an attempt at a beginning – all of it requires a great deal of refinement. Although those viewers who have been there before will see how we are currently striving to make progress from month to month in the development of the forms, the three-dimensionally moving forms of groups – we are also our own harshest critics and know exactly what perfection we still need.

It should also be noted that in the art of recitation, which has the particular artistic task of emphasizing the poetic, we do not achieve this by particularly emphasizing the prose content and , but that every effort must be made to apply a suitably artistic form of recitation to eurythmy, which is certainly still in its early days today, and that this will not be universally understood today. What is available as a beginning in the artistic field can, especially if our contemporaries are interested, perhaps be perfected by ourselves, but probably by others. And then something will develop out of this eurythmic art that will be able to stand as a fully-fledged sister art alongside the older fully-fledged sister arts of eurythmy.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden! Die eurythmische Kunst, von der wir Ihnen auch heute hier eine kleine Probe vorführen wollen, versucht anders als gewisse Nach Louise van Blommestein KSaG, M.4761 barkünste, die man leicht damit verwechseln kann - Tanzkünste oder sonstige mimische Künste -, anders als diese vorzudringen in einer gewissen Weise zu den Quellen des menschlichen künstlerischen Schaffens überhaupt. Sie sucht dies zu erreichen durch ganz besondere Kunstmittel. Und weil darüber notwendig ist, einige Worte zu sagen, damit das Wesen dieser künstlerischen Richtung ins Auge gefasst werden könne, sende ich diese Worte voraus - nicht etwa um die Vorstellung selbst zu erklären, was natürlich ein unkünstlerisches Unternehmen wäre. Denn Kunst muss durchaus durch sich selbst für den unmittelbaren Eindruck sprechen.

Dasjenige, was Sie auf der Bühne sehen werden, nimmt sich aus wie eine Art durch den ganzen Menschen vollzogener Gebärde. Das ist es aber nicht, und man würde die Eurythmie eben ganz falsch beurteilen, wenn man meinen würde, dass diejenige Bewegung, die entweder durch den einzelnen Menschen oder durch menschliche Gruppen zustande kommen, dass diese Bewegungen bloße Gebärden seien, die ausdrücken sollen dasjenige, was entweder auf der einen Seite musikalisch oder auf der anderen Seite dichterisch-rezitatorisch vorgetragen werden soll. Eurythmie will nämlich in Wirklichkeit sein eine richtige sichtbare Sprache, sie will in plastischer Bewegung genau dasselbe offenbaren, was offenbaren kann der menschliche Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane durch den Laut.

Will man Eurythmie in ihrem Wesen verstehen, so muss man darauf eingehen, welches ihre Quellen sind. Es ist die sinnlich-übersinnliche Beobachtung jener Bewegungstendenzen, die der menschliche Kehlkopf und alles das, was mit den Sprachorganen zusammenhängt, ausdrückt, wenn die Lautsprache ertönt. Nicht diejenigen Bewegungen sind gemeint, die als unmittelbare Zitterbewegungen, als Schwingungen übergehen in die äußere Luft, sondern diejenigen Bewegungen sind gemeint, die diesen Zitterbewegungen als Bewegungstendenzen zugrunde liegen. Bewegungen, die sprachorganisch mehr ausführen wollen, als dass sie wirklich ausführen. Aber das sinnlich-übersinnliche Schauen - um diesen Goethe’schen Ausdruck zu gebrauchen kann diese Bewegungen beobachten und sie dann nach dem Metamorphoseprinzip auf den ganzen Menschen übertragen. So wie Goethe namentlich die ganze Pflanze in ihrer Kompliziertheit eben als ein in der einzelnen Gliederung vermannigfaltigtes Blatt, eigentlich nur ein komplizierter gewordenes Blatt sieht, so ist dasjenige, was Sie wie einen Kehlkopf als ganzen Menschen vor sich auf der Bühne sehen, eben umgewandelt dasjenige, was beim gewöhnlichen Zuhören der menschlichen Sprache natürlich nicht beachtet wird, was aber doch durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen als Bewegungen, als eine innere Eurythmie der Sprachorgane beobachtet werden kann. Das ist übertragen auf den ganzen Menschen. Die einzelnen Bewegungen, die der Mensch ausführt oder die Menschengruppen ausführen, sind also genau so zu beurteilen, wie die menschliche Sprache selbst nach der inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit.

Nun müsste man ja, eben wenn man oberflächlich das anschaut, was dargestellt wird, glauben, man hätte es mit Pantomime oder Mimik zu tun. Dagegen ist zu sagen, dass ja, wenn wir sprechen, wir zuweilen auch uns veranlasst fühlen, durch Gebärden unsere Sprache zu unterstützen. Wann tun wir das? Wir tun das nur dann, wenn wir das Gefühl haben, etwas, was in der Sprache mehr oder weniger voll zum Ausdruck kommt, dem subjektiv nachzugehen. Aber das, was in der eigentlichen Eurythmie vorliegt, das ist eben geradeso objektiv wie dasjenige, was bei der Sprache zum Ausdrucke kommt; alle Gebärde ist davon ausgeschlossen, alles bloß Pantomimische und Mimische ist eben davon ausgeschlossen. Das kann nun so in Betracht kommen, wie es für die gewöhnliche Sprache in Betracht kommt.

Man wird gewiss auf der einen Seite zu sagen haben: Eurythmie ist so sehr eine innere gesetzmäßige sichtbare Sprache, dass, wenn zwei Menschen oder zwei Menschengruppen ein und dasselbe Gedicht an ganz verschiedenen Orten vortragen, so ist die individuelle Verschiedenheit nicht größer, als wenn zwei Klavierspieler eine und dieselbe Sonate spielen. Das ist auf der einen Seite so. Aber man kann auch sagen: Man unterscheidet ja, nicht wahr, zwei Klavierspielende in ein und demselben Stück, das sie spielen, ihrer individuellen Nuancierung nach - die wird sich auch beim einzelnen Eurythmisten oder der einzelnen Eurythmistengruppe finden. Da wird dann dasjenige, was subjektiv in die Gebärde übergeht, sich nuancierend verbinden mit demjenigen, was objektive Gesetzmäßigkeit ist.

Dann haben wir also in dieser sichtbaren Sprache der Eurythmie etwas vor uns, nicht in der einzelnen Gebärde, nicht den Ausdruck von irgendetwas, was als Wortwörtliches in der Seele lebt, sondern wir haben in der einzelnen eurythmischen Bewegungsform etwas vor uns, in dem sich der ganze Mensch drinnen so fühlt, wie er sich in einem einzelnen Lautbestande oder Worte oder Wortzusammenhängen fühlt, wie er sich in der gesprochenen Sprache fühlt. Und dasjenige, was wirkt, wirkt nicht dadurch, dass cs als Einzelnes etwas ausdrückt, was in der Seele vorgeht, sondern dass sich die eine Bewegung an die andere angliedert und so eine Bewegungsfolge entsteht, wie im Sprechen eine Lautfolge entsteht. Genau ebenso, wie es im Musikalischen ist, wo wir auch in der Aufeinanderfolge der Töne eine innere gesetzmäßige Bewegung haben, so kommt bei der Eurythmie eine solche innere Bewegung gewissermaßen als innere plastische Musik zum Vorschein.

Dadurch sind wir in der Lage, durch die Eurythmie herauszuholen aus einem Gedicht - Gedichte werden es ja neben dem Musikalischen vorzüglich sein, die rezitatorisch die Eurythmie zu begleiten haben -, die Eurythmie drückt nur eben in stummer, in bewegter Sprache dasjenige aus, was durch die Rezitation in der Lautsprache zum Ausdrucke gebracht wird. Wir haben aber Gelegenheit, dasjenige, was den ganzen Menschen angeht, dasjenige, was nicht im Konventionellen oder in bloßem Gedankenausdruck zum Ausdrucke kommt - das Unkünstlerische an der Dichtung -, sondern wir haben Gelegenheit, das ganze Fühlen und Wollen, die ganze Persönlichkeit des Menschen wie in einem großen, bewegten Kehlkopfe zum Ausdruck zu bringen.

Dazu ist allerdings notwendig, und das muss immer wieder erwähnt werden, dass überhaupt zu dem eigentlich künstlerischen Elemente der Dichtung wiederum zurückgekehrt werden muss. Unsere Zeit ist eine im Wesentlichen unkünstlerische, und man empfindet sehr häufig heute deshalb als das Wesentliche an der dichterischen Kunst, was wortwörtlicher Inhalt ist. Dagegen muss immer wieder und wiederum gesagt werden, dass Schiller zum Beispiel eine unbestimmte Melodie in seiner Seele lebendig hatte, und aus dieser unbestimmten Melodie konnte nun alles Mögliche noch werden, ob es «Der Taucher» wurde oder «Der Kampf mit dem Drachen» oder irgendetwas anderes - das stellte sich erst später ein. Das Wesentliche für Schiller war nicht der wortwörtliche Inhalt, [Lücke im Text] nicht also die Prosa, die in dem Gedichte ist, sondern das Wichtige war der Rhythmus, der Takt, das Musikalische, das Plastische, das Bildhafte.

Heute liebt man eine Rezitationskunst, die eigentlich mit Künstlerischem nicht mehr viel zu tun hat, sondern manchmal mit menschlicher Sentimentalität, mit menschlichem guten Willen, das oder jenes recht innerlich auszudrücken — wobei es ja immer doch eine Phrase bleibt oder eine Sentimentalität bleibt. Dasjenige aber, was wirkliche Rezitation ist, man kann es ja noch aufsuchen in älteren Zeiten. Goethe hat mit dem Taktstock seine «Iphigenie» mit seinen Schauspielern einstudiert, nicht so schr auf den Inhalt eingehend, sondern auf die Art und Weise, wie der Jambus seinen Schritt ging. Dieses Wortwörtliche als Rezitation könnte man gar nicht als Begleitungskunst der Eurythmie gegenüberstellen, sondern da muss man auch auf das Eurythmische im Sprechen selber eingehen. Und so muss hier so rezitiert werden, wie die guten alten Künstlerzeiten rezitiert haben.

Das alles zeigt, dass mit dieser Eurythmie etwas angestrebt wird, was durchaus sich als gewissermaßen Neues hineinstellen will in unsere ganze Geistesbewegung, ein Stück Goetheanismus. Goethe hat ja so schön gerade das charakterisiert, was die Eurythmie - wenn auch in sehr eingeschränktem Gebiete - verwirklichen kann. Goethe sprach davon, wie der Mensch, wenn er sich auf den Gipfel der Natur gestellt sieht, sich wiederum als eine ganze Natur empfindet und Harmonie, Maß und Bedeutung in sich hereinnimmt und sich endlich zur Produktion des Kunstwerkes erhebt.

Diese Produktion des Kunstwerkes lebt, ich möchte sagen am menschlichsten dann, wenn der Mensch auf dem Gebiet, in dem er die Eurythmie sieht, sich selber zum künstlerischen Werkzeug macht für dasjenige, was er darzustellen hat. Dann ist wirklich dieser Mikrokosmos, diese kleine Welt, wie der Mensch sie darstellt, wie er sie vor uns bringt, nicht aus einzelnem Willkürlichen zum Ausdruck des Subjektiven, das in der Gebärde, in der Mimik zum Ausdrucke kommt, [gedacht]. Sondern dasjenige, was in ihm veranlagt ist aus seinem ganzen Eingegliedert-Sein in die Welt, das ist im Wesentlichen mit Bezug auf das Künstlerische der Eurythmie zu sagen. Und in erster Linie soll ja die Eurythmie etwas Künstlerisches sein.

Aber daneben steht auch - und Sie werden eine kleine Probe in der Kindereurythmie sehen, die wir Ihnen im zweiten Teil neben einigem Humoristischen vorführen werden -, neben dem steht ja die didaktisch-pädagogische Bedeutung dieser eurythmischen Kunst. Es ist durchaus etwas Bedeutsames, wenn man schon an Kinder diese Eurythmie heranbringt, aus dem Grunde, weil man im pädagogischdidaktischen Sinne diese Eurythmie auffassen kann als eine Art des seelischen Turnens. Es werden Zeiten kommen, die objektiver über diese Dinge denken als die unsrige.

In der neueren Zeit hat man ja - und zwar mit einem gewissen Recht, dagegen soll nicht kritisiert werden, nichts Besonderes eingewendet werden, dass das Turnen als eine besondere Wohltat für die heranwachsende Jugend angesehen werde -, dagegen hat man sich gewendet. Eine bedeutende Autorität sagte mir vor einiger Zeit, dass er das Turnen nicht als Erziehungsmittel, sondern als eine Barbarei betrachte. Soweit möchte ich nicht gehen. Aber es ist ganz deutlich in unserem Zeitalter angemessen und vom Leben gefordert, dass dieses seelische Turnen der Eurythmie für die Kinder von pädagogischdidaktischer Bedeutung ist. Die Stärke des Seelischen, Willensinitiative, das ist dasjenige, was herangezogen werden kann durch dieses beseelte Turnen, während dem das gewöhnliche Turnen - nur aus dem Grunde, weil es aus der Physiologie den Menschen betrachtet, nur für den Körper, der gewisse Bewegungen ausführt - einiges an Hilfe für die Fertigkeit geben kann.

Es wird zum Beispiel gerade in der von Emil Molt begründeten Waldorfschule in Stuttgart dieses beseelte Turnen, die Eurythmie, eingeführt. Es wird dadurch ein wesentlich[es] didaktisch-pädagogisches Element gewonnen. Und noch in mancher anderen Beziehung wird man sehen, dass diese Eurythmie dasjenige vielleicht den Menschen des gegenwärtigen Zeitalters geben kann, was von anderer Seite her nicht kommen kann. An was dachte man alles, bevor dieser Krieg entbrannt ist - da dachten die Leute daran, olympische Spiele aufzuführen. Es ist geradeso, wie wenn man dem Menschen in einem gewissen Lebensalter nicht dasjenige geben wollte, was für ihn gut ist, sondern etwas, was für ein ganz anderes Lebensalter gut ist. Man sieht eben heute alles nur abstrakt und intellektuell, aktuell ein, und nicht aus der Wirkung heraus. Die olympischen Spiele waren das Natürliche für dasjenige, was der Mensch in jenem Zeitalter brauchte. Heute brauchen wir etwas ganz anderes als olympische Spiele. Heute brauchen wir etwas, was den Menschen auch seelischgeistig hineinstellt in den ganzen Weltzusammenhang. Und so sind die olympischen Spiele und alle die Gedanken, die auf Ähnliches hinzielen, nichts anderes als ein gewisser Dilettantismus gegenüber der menschlichen Kulturentwicklung.

Dasjenige, was in der Eurythmie versucht wird, ist allerdings heute nur erst ein bescheidener Anfang, worauf ich immer wieder hinweisen muss. Aber es ist dasjenige, was so recht aus den Forderungen der unmittelbaren Gegenwart, aus den Forderungen unserer Zeit herausgeholt ist. Und so darf man sagen: Auf der einen Seite müssen die verehrten Zuschauer gebeten werden, dasjenige, was wir jetzt darstellen können, wirklich nur als den Versuch eines Anfanges zu betrachten - es bedarf alles gar sehr der Vervollkommnung. Obwohl diejenigen Zuschauer, die schon früher da waren, sehen werden, wie wir uns bemühen gerade, von Monat zu Monat in der Ausbildung der Formen, der plastisch bewegten Formen von Gruppen weiter zu kommen - wie wir selbst auch unsere strengsten Kritiker sind und genau wissen, welche Vervollkommnung wir noch nötig haben.

Es ist noch zu bemerken, dass wir in der Kunst der Rezitation, die das besondere Künstlerische in dem Dichterischen hervorzuheben hat, dies nicht dadurch zustande bringen, dass wir den Prosagehalt besonders betonen und ihn zur Kunst zu erheben versuchen, sondern dass alles angestrebt werden muss, um nach der anderen Seite hin auch in der Eurythmie, die ja gewiss heute noch in ihrem Anfange vorliegt, eine entsprechend künstlerische Rezitationsform anzuwenden, die heute noch nicht überall verstanden werden wird. Was als ein Anfang vorliegt auf künstlerischem Gebiete, es kann, namentlich wenn cs das Interesse unserer Zeitgenossen zulässt - vielleicht noch durch uns selbst, wahrscheinlich aber von anderen - vervollkommnet werden. Und dann wird sich schon aus dieser eurythmischen Kunst etwas herausentwickeln, was als eine vollberechtigte Schwesterkunst neben die älteren vollberechtigten Schwesterkünste die Eurythmie wird hinstellen können.