The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

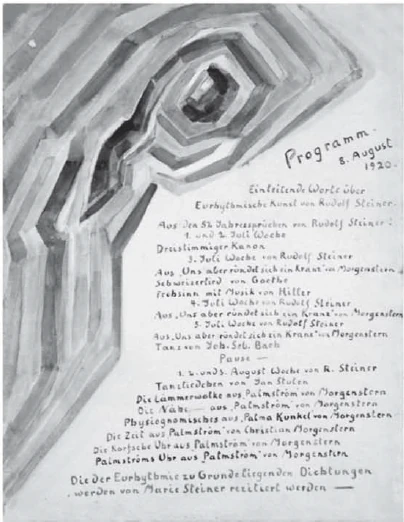

8 August 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

74. Eurythmy Performance

Dear Attendees:

As was usual before these eurythmic performances, I would also like to introduce the presentation with a few words today. Eurythmy art uses a form of expression that is essentially new. However, my intention is not to explain what can be seen on stage, which would be inartistic – and artistic work should not need explanation – but rather to say something about this particular means of expression. Therefore, I would like to take the liberty of saying a few words beforehand.

The point is that this means of expression, a kind of visible language, is a language that works either by the whole person moving his limbs in a way that is intended to appeal to the eye in the same way as audible language appeals to the ear, or by groups of people making such movements, which constitute a kind of visible language. But it is not the opinion that this visible language should be what could be called facial expressions or gesturing or the like, but rather the opinion that the direct connection between gestures and expressions and what is going on inwardly in the soul must be must be avoided here in the artistic, as it is avoided in ordinary language, which, although it has arisen from the direct expression of feeling and external observation, is not exhausted in what could be understood as a play of gestures. It is a careful, intuitive study of the development of spoken language that leads, as it were, to the formation of this visible language.

If one develops what Goethe calls sensory-supersensory vision, one can see which movements, but especially which movement tendencies, underlie the production of audible speech by the larynx and the other speech organs. It is well known that speech is based on a kind of movement. As I speak here, the movements that are carried out by my speech organs are transmitted to the air, and it is precisely the content of what is spoken that is conveyed to the ear through the air. But it is not about these immediate vibrational movements, but rather about what, as it were, lives in these vibrations as a tendency to move, which is now carefully studied for each sound, each sound formation, for sound contexts, but which is also studied by name for sentence structure, for the internal laws of language. And all that can be studied in this way and remains unnoticed as something that only underlies the spoken language, because one draws attention to what is heard and not to what underlies the movement, all that remains unnoticed in spoken language, is transferred to the whole person. In this way the whole human being appears before the spectator as a living larynx, executing those movements which are otherwise present in the larynx as a tendency, and through which this visible speech comes about.

It may be noted that in the present day, this eurythmic art, which is born out of our anthroposophically oriented worldview, which is a further development of Goethe's view of art and artistic attitude, that this eurythmic art meets certain aspirations that live as longings, as artistic longings in our time. Who would not know, if they have only delved a little into the artistic striving and working of the present, that the arts are wrestling with new means of expression, with a new formal language? And who would not know how different the paths are on which the struggle is waged? But how unsatisfactory it is to create something out of color, out of form, and also out of words, in order to gain a new means of expression.

If we want to describe what actually prevails in newer, in modern artistic striving, then at the same time we have what still makes it difficult for viewers to directly perceive the artistic representation of the eurythmic art. For what are today's modernizations of artistic striving based on? We see how, in the development of modern times, the human being has more or less lost the ability to develop forces from within, through which he can give himself to the outside world, through which he can completely merge with the outside world.

If we look back at earlier artistic epochs, which are no longer fully understood even by many today, we have to say: something like a Raphael or a Michelangelo work of art, they arise precisely from the artist's ability to inwardly experience what the being he is depicting experiences. This inner co-experience with nature, with the world in general, has been gradually lost by people in recent centuries and is increasingly being lost in the present to the external perception of life.

Art has always tried – one need only recall Goethe's definitions of art – to reflect what one could experience through inner involvement with the other, with other beings, with external nature. They tried to replace this, let us say, with the impression of fate, with the momentary impression as in Impressionism, in the consciously impressionistic state that art wants to become, because one could not grow together with the object, as one had to, so to speak, fall out of the object; therefore one surrendered to the momentary impression. This impressionistic devotion to the momentary impression cannot lead to a real, genuine means of artistic expression, for the simple reason that this momentary impression can no longer be understood once it has passed. To a certain extent, you have to believe that such a momentary impression, captured in the impressionistic work of art, was once there. Impressionism, which seeks to be naturalistic, removes you from the actual essence of things. Man cannot bring his inner self into the world. So, artistically, he becomes an impressionist.

But then, as a kind of opposition to Impressionism, the expressionist principle has arisen in recent times. It appeared, so to speak, provocatively. Man, having lost the ability to immerse his inner self in the outer, wanted to directly express this inner self as an expression of the soul through the usual artistic means of expression.

But this, in turn, brings with it, I would say, the other danger, that what is experienced quite subjectively, subjectively experienced in the deepest inner self, is presented as a single human experience, and this again sets a limit to understanding, in that the spectator would again have to respond tolerantly to what a single individual human being experiences as the deepest experience of the soul, which he cannot do at all, to express something about which one can only say – the philistine can say –: He wants to paint or draw something spiritual; I see water, a number of ship sails, which I might just as well think are laundry hanging out to dry, and so on. These are things that are produced in expressionism, that may project the human interior outward, but cannot be understood because they are not experienced, but are merely there, in that this individual human interior is depicted as being directly connected to the external world, in direct connection with the external world.

Nevertheless, a way to truly artistic means of expression will have to be found again, in which one, so to speak, meets impressionism with expressionism, and vice versa. But one can believe that something like eurythmy could accommodate the search that lies in this direction and that this is precisely why eurythmy is so much in demand today - which, after all, is also the case with everything else that emerges from anthroposophical culture and world view.

The fact that the whole human being becomes, as it were, a larynx, that the whole human being is a means of expression for a visible language, means that what the human being can experience inwardly, which is also is experienced in the recited poems or the music played, what is experienced after, what is experienced in the innermost being, in the human soul, comes to expression in the human being himself as an outer manifestation. But this means that it is not just a momentary impression – an expression that can be captured in an impressionistic way. For if something in nature is fixed by some momentary impression, we have something that we can and do express spiritually, that we delve into the soul of nature. We can develop this by looking at the expression that is presented in eurythmic performances by the human being himself. Here, spirit and soul are presented directly in the outer movements before our eyes. At the same time, there is impression. It should not be said that eurythmy is an all-encompassing art in this respect, but it can certainly be said that it points the way to how artistic means of expression can be found for what can be felt as a yearning in broad circles of artistic endeavor today.

That, in a few words, is the modern aspect of eurythmy in the best sense of the word, what our time demands of eurythmy as an art.

But then this eurythmy has a further, pedagogical-didactic side, in that it is a kind of soulful gymnastics for the child. In the age of our materialism, purely physiological gymnastics, that which is essentially based on the materialistic view of the human body, has been produced by these views, and takes precedence. Today, people are still one-sided in this respect, although some minds, which now want to do away with many of the prejudices of the present day - such as Spengler, for example - already recognize how one-sided this kind of gymnastics is. Of course, nothing should be said against the educational value of this kind of gymnastics, but it must be supplemented by something that not only trains the body, but above all, from the soul, pours initiative into the human being, which is so lacking in our time. This can be done by the child not just doing the gymnastic movements required by the physical organization, but by making soulful movements, so that soul lives in every movement. This affects the will. It becomes inwardly soulful and strengthens the human being in the will initiative, in the creation of the will initiative. And this is what our civilization needs if it wants to move forward.

Today I want to disregard the hygienic-therapeutic side that is still in our eurythmy. Everything that eurythmy can develop is still in its infancy today. And those of our esteemed viewers who have been here before will see how we are now trying to really follow through on the broader form, for example, in terms of gesture formation and form building, how we are trying more and more to , all the gestures of the moment, and to really bring forth a moving language and music, and how we are particularly concerned not to reproduce what the prose content of the poem is, but what the poetic artist has made of that content.

Despite our efforts to move forward, I have to say it here before every eurythmy performance attended by guests: despite our efforts to move forward, we are nevertheless quite clear about the fact that this eurythmic art is only just beginning, that this eurythmic art is a very first attempt – perhaps even an attempt with inadequate means even today. But we are also clear about the fact that if we continue to develop what has already been tried, or if others continue to develop it, then eurythmy art can become something that can stand as a legitimate art alongside other, older sister arts.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Wie es sonst üblich war vor diesen eurythmischen Aufführungen, so möchte ich auch heute die Darstellung mit ein paar Worten einleiten. Eurythmische Kunst bedient sich ja einer Ausdrucksweise, die als solche im Wesentlichen neu ist. Aber nicht darum handelt es sich, um etwa dasjenige, was auf der Bühne gesehen werden soll, zu erklären, was unkünstlerisch wäre - und Künstlerisches soll nicht eine Erklärung nötig haben -, sondern es handelt sich darum, einiges zu sagen über dieses besondere Ausdrucksmittel, und deshalb nur möchte ich mir erlauben, ein paar Worte vorauszuschicken.

Es handelt sich darum, dass dieses Ausdrucksmittel, eine Art sichtbare Sprache, eine Sprache ist, welche dadurch wirkt, dass entweder der ganze Mensch in seinen Gliedern Bewegungen ausführt, die ebenso für den Anblick wirken sollen wie die hörbare Sprache für das Ohr, oder auch dadurch, dass Menschengruppen solche Bewegungen ausführen, die eine Art eben sichtbarer Sprache darstellen. Aber es ist nicht die Meinung, dass diese sichtbare Sprache dasjenige sein soll, was man Mimik oder Gebärdenspiel oder dergleichen nennen könnte, sondern es ist die Meinung, dass das unmittelbare Zusammenhängen von Gebärden, von Ausdruck mit dem, was innerlich in der Seele vorgeht, ebenso vermieden werden muss hier im Künstlerischen, wie es ja vermieden ist in der gewöhnlichen Sprache, die ja zwar aus unmittelbarem Ausdrücken des Empfindens und des äußeren Anschauens hervorgegangen ist, aber doch nicht sich in dem erschöpft, was man etwa als Gebärdenspiel auffassen könnte. Es ist ein sorgfältiges, intuitives Studium des Zustandekommens der Lautsprache, das gewissermaßen zur Ausgestaltung dieser sichtbaren Sprache führt.

Man kann, wenn man das entwickelt, was Goethe sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen nennt, darauf kommen, welche Bewegungen, namentlich aber welche Bewegungstendenzen zugrunde liegen, wenn der Mensch durch den Kehlkopf und die anderen Sprachorgane die hörbare Sprache hervorbringt. Auf einer Art von Bewegung beruht das Sprechen, das ist hinlänglich bekannt. Indem ich hier spreche, übertragen sich jene Bewegungen, die von meinen Sprachorganen ausgeführt werden, auf die Luft, und durch die Luft wird eben der Inhalt des Gesprochenen dem Ohr vermittelt. Aber nicht um diese unmittelbaren Vibrationsbewegungen handelt es sich, sondern um dasjenige, was gewissermaßen als Bewegungstendenz in diesen Vibrationen eben darinnen lebt, das nun sorgfältig studiert wird für jeden Laut, jede Lautbildung, für die Lautzusammenhänge, das studiert wird aber namentlich auch für den Satzbau, für die inneren Gesetzmäßigkeiten der Sprache. Und das alles, was man so studieren kann und was unvermerkt bleibt als etwas der Lautsprache nur Zugrundeliegendes, weil man dabei die Aufmerksamkeit auf das zu Hörende lenkt und nicht auf das, was der Bewegung zugrunde liegt, alles das, was da unvermerkt bleibt bei der Lautsprache, das wird übertragen auf den ganzen Menschen. Sodass gewissermaßen der ganze Mensch vor dem Zuschauer wie ein lebendiger Kehlkopf erscheint, ausführt diejenigen Bewegungen, die sonst im Kehlkopf der Tendenz nach veranlagt sind, wodurch eben diese sichtbare Sprache zum Vorschein kommt.

Es darf schon bemerkt werden, dass in der Gegenwart diese eurythmische Kunst, die ja herausgeboren ist aus unserer anthroposophisch orientierten Weltanschauung, die ein weiterer Ausbau ist der Goethe’schen Kunstanschauung und Kunstgesinnung, dass diese eurythmische Kunst entgegenkommt gewissen Bestrebungen, die als Sehnsuchten, als künstlerische Sehnsuchten in unserer Zeit leben. Wer wüsste denn nicht, wenn er sich nur etwas vertieft hat in das künstlerische Streben und Wirken der Gegenwart, dass die Künste nach neuen Ausdrucksmitteln, nach einer neuen Formsprache hin ringen? Und wer wüsste nicht, wie verschieden die Wege sind, auf denen gerungen wird? Wie wenig befriedigend aber dasjenige ist, was man versucht, aus der Farbe, aus der Form heraus zu schaffen, auch aus dem Worte heraus zu schaffen, um ein neues Ausdrucksmittel zu gewinnen.

Wenn man bezeichnen will dasjenige, was da eigentlich waltet im neueren, im modernen künstlerischen Streben, so hat man zu gleicher Zeit dasjenige, was heute noch im unmittelbaren Anblick den Zuschauern es schwierig macht, die Darstellung der eurythmischen Kunst unmittelbar künstlerisch zu empfinden. Denn woraus gehen die heutigen Modernisierungen des künstlerischen Strebens denn hervor? Wir sehen, wie in der Entwicklung der neueren Zeit der Mensch mehr oder weniger die Fähigkeit verloren hat, aus seinem Inneren heraus Kräfte zu entwickeln, durch die er sich an die Außenwelt hingeben kann, durch die er ganz aufgehen kann in der Außenwelt.

Wenn wir die früheren Kunstepochen, die heute nicht einmal mehr von vielen ganz verstanden werden, zurückblicken, so müssen wir sagen: So etwas wie ein Raffael’sches, wie ein Michelangelo’sches Kunstwerk, sie gehen ja gerade hervor aus dem Vermögen des Künstlers, innerlich mitzuerleben dasjenige, was das Wesen, das er darstellt, erlebt. Dieses innerliche Miterleben mit der Natur, mit der Welt überhaupt, das ist ja in den letzten Jahrhunderten allmählich den Menschen verloren gegangen und geht in der Gegenwart immer mehr und mehr noch der äußeren Lebensempfindung verloren.

[Die Kunst versuchte ja gerade immer - man braucht sich nur an Goethe’sche Kunstdefinitionen zu erinnern -, dasjenige wiederzugeben, was man aus innerlichem Miterleben mit dem Andern, mit anderen Wesen, mit der äußerlichen Natur erfahren konnte. Man versuchte das zu ersetzen, sagen wir, durch den Schicksalseindruck, durch den Augenblickseindruck wie im Impressionismus, im impressionistisch bewussten Zustande die Kunst werden will, weil man nicht verwachsen konnte mit dem Objekt, wie man gewissermaßen herausfallen musste aus dem Objekte; deshalb gab man sich hin an den Augenblickseindruck.] Dieses impressionistische Hingeben dem Augenblickseindruck, es kann doch nicht zu einem wirklichen, echten künstlerischen Ausdrucksmittel führen, aus dem einfachen Grunde, weil dieser Augenblickseindruck ja nicht mehr verstanden werden kann, sobald er vorüber gegangen ist. Man muss gewissermaßen den Glauben haben, solch ein Augenblickseindruck, der im impressionistischen Kunstwerk festgehalten wird, der war einmal da. Es entfernt einen der Impressionismus, der gerade naturalistisch sein will, er entfernt einen von dem eigentlichen Wesen der Dinge. Der Mensch kann sein Inneres nicht heraustragen in die Welt. So wird er künstlerisch Impressionist.

Dann aber hat sich erhoben in der letzten Zeit wie eine Art Opposition gegen den Impressionismus das expressionistische Prinzip. Es trat gewissermaßen provozierend auf. Der Mensch wollte, weil er die Fähigkeit verloren hatte, sein Inneres in das Äußere zu vertiefen, unmittelbar dieses Innere als Expression, als Ausdruck des Seelischen hinstellen durch die gebräuchlichen künstlerischen Ausdrucksmittel.

Dadurch aber ist wiederum, ich möchte sagen die andere Gefahr sehr naheliegend, dass man dasjenige, was ganz subjektivistisch erlebt ist, im tiefsten Innern subjektiv erlebt, als einzelnes menschliches Erlebnis hinausstellt, und dadurch wieder eine Grenze für das Verständnis gegeben ist, dadurch, dass der Zuschauer ja wiederum tolerant eingehen müsste auf das, was ein einzelner Mensch als tiefstes Seelenerlebnis erlebt, [w]as er gar nicht kann, etwas zum Ausdruck bringen, über das man nur sagen kann - das kann der Philister sagen -: Der will irgendetwas Seelisches malen, zeichnen; Wasser, eine Anzahl Schiffssegel sehe ich, die ich ebenso gut für aufgehängte Wäsche halten kann und so weiter. Das sind Dinge, die im Expressionismus hervorgebracht werden, die das menschliche Innere zwar nach außen werfen, aber nicht verstanden werden, weil sie nicht erlebt sind, sondern bloß so sind, dass dieses einzelne menschliche Innere unmittelbar mit der Außenwelt, in einem unmittelbaren Zusammenhange mit der Außenwelt dargestellt ist.

Dennoch wird sich ja ein Weg zu wirklich künstlerischen Ausdrucksmitteln wiederum finden müssen, indem man gewissermaßen mit dem Expressionismus dem Impressionismus entgegenkommt, und umgekehrt. Aber man kann glauben, dass gerade so etwas, wie die Eurythmie dem Suchen, das in dieser Richtung liegt, entgegenkommen könne und dadurch gerade diese Eurythmie so recht wie von der Gegenwart gefordert wird - was ja bei allem Übrigen, was aus anthroposophischer Kultur und Weltanschauungsempfindung hervorgeht, auch der Fall ist.

Dadurch, dass der ganze Mensch gewissermaßen Kehlkopf wird, dass der ganze Mensch Ausdrucksmittel für eine sichtbare Sprache ist, dadurch kommt wirklich dasjenige, was der Mensch im Innerlichen erleben kann, was auch nacherlebt ist, in den rezitierten Gedichten oder der gespielten Musik, es kommt doch dasjenige, was seelisches Leben ist, Innerstes, Menschliches, unmittelbar als äußerer Sinnenschein am Menschen selbst zum Ausdruck. Dadurch aber ist es wiederum etwas, was nicht bloß Augenblickseindruck ist - eine Expression, die zu gleicher Zeit impressionistisch aufgenommen werden kann. Denn wenn durch irgendeinen Augenblickseindruck etwas in der Natur fixiert ist, so haben wir eben doch etwas, was wir seelisch ausdrücken wollen und können, dass wir uns in die Seele der Natur hineinvertiefen. Das können wir entwickeln, wenn wir jene Expression betrachten, die in eurythmischen Darstellungen durch den Menschen selbst sich darbietet. Da ist Geist und Seele unmittelbar in den äußeren Bewegungen vor die Augen hingestellt. Da ist zu gleicher Zeit Impression. Sodass durchaus - es soll [nicht etwa] behauptet werden, dass die eurythmische Kunst nun eine allumfassende Kunst nach dieser Richtung ist, aber es kann durchaus gesagt werden: Sie weist gewissermaßen den Weg, wie man künstlerische Ausdrucksmittel für dasjenige finden kann, was in breiten Kreisen künstlerischen Strebens als Sehnsucht heute zu merken ist.

Das als ein paar Worte über das im besten Sinne des Wortes Moderne in der Eurythmie, des von der Zeit Geforderten unserer Eurythmie als Kunst.

Dann aber hat diese Eurythmie eine weitere, eine pädagogischdidaktische Seite, indem sie für das Kind eine Art beseeltes Turnen ist. In der Zeit unseres Materialismus hat ja das rein physiologische Turnen, dasjenige, was im Wesentlichen gebaut ist auf die materialistische Betrachtung des menschlichen Körpers, das hervorgebracht wurde durch diese Anschauungen, den Vorrang. Man ist heute durchaus noch einseitig eingestellt in dieser Beziehung, obwohl schon einige Geister, die nun überhaupt aufräumen möchten mit manchem, was in der Gegenwart als Vorurteil ist - wie zum Beispiel Spengler -, schon einsehen, wie einseitig auch dieses Turnen ist. Gewiss soll nichts gesagt werden gegen den pädagogischen Wert dieses Turnens, aber es muss ergänzt werden durch dasjenige, was nun nicht bloß den Körper ausbildet, sondern was vor allen Dingen von der Seele aus Willensinitiative bewirkt, die ja unserer Zelt so sehr fehlt, Willensinitiative in den Menschen hinein gießt. Das kann dadurch geschehen, dass das Kind nun nicht bloß die von der körperlichen Organisation geforderten Turnbewegungen macht, sondern dass es beseelte Bewegungen macht, dass in jeder Bewegung Seele lebt. Das wirkt auf den Willen. Das wird innerlich seelisch und stärkt den Menschen in der Willensinitiative, im Hervorbringen der Willensinitiative. Und dies braucht unsere Zivilisation, wenn sie vorwärtskommen will.

Dice hygienisch-therapeutische Seite, die noch in unserer Eurythmie ist, will ich heute außer Acht lassen. Alles dasjenige, was Eurythmie entwickeln kann, ist ja heute noch ein Anfang. Und di; nigen der verehrten Zuschauer, die schon öfter da waren, werden sehen, wie wir uns bemühen, in der breiteren Form nun wirklich dem nachzukommen, was zum Beispiel Gebärdenbildung, Formbildung ist, wie wir immer mehr und mehr bemüht sind, alle mimischen, pantomimischen, alle Augenblicksgebärden herauszuwerfen und wirklich eine bewegte Sprache und Musik hervorzubringen und wie wir namentlich darauf bedacht sind, nicht dasjenige, was Prosainhalt des Gedichtes ist, wiederzugeben, sondern das, was der dichterische Künstler aus dem Inhalt gemacht hat.

Trotzdem wir uns bemühen, vorwärtszukommen, muss ich eben vor jeder eurythmischen Aufführung hier, die von Gästen besucht wird, es aussprechen, trotzdem wir uns bemühen, vorwärtszukommen, sind wir uns darüber doch ganz klar, dass diese eurythmische Kunst am Anfange erst steht, dass diese eurythmische Kunst ein allererster Versuch ist - vielleicht sogar ein Versuch mit unzulänglichen Mitteln ist heute noch. Aber wir sind uns auch klar darüber, dass, wenn dasjenige, was schon versucht worden ist, weiter auszubilden, durch uns oder wahrscheinlich durch andere immer mehr und mehr ausgebildet sein wird, dass die eurythmische Kunst einmal etwas werden kann, was als berechtigte Kunst neben andere, ältere Schwesterkünste sich wird hinstellen können.