The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1920–1922

GA 277c

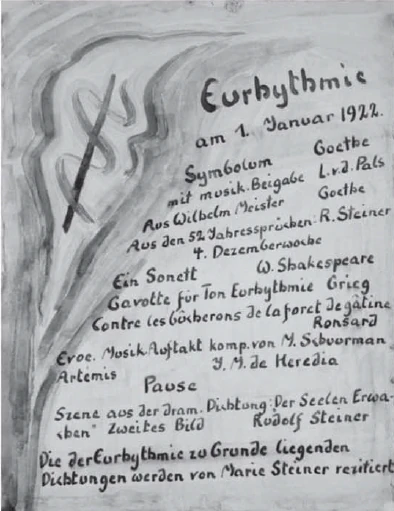

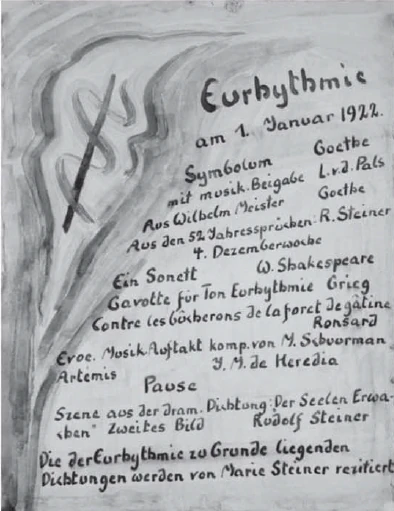

1 January 1922, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Address on Eurythmy

The performance took place in the dome room of the Goetheanum.

Ladies and gentlemen!

Today, I will again limit myself to saying just a few words about how a stylization that can be brought to life in a particularly effective way through eurythmy on stage will be presented today in a few pieces from the “Mystery Dramas” I have attempted. In the second part of today's performance, we will present a scene from “The Awakening of Souls,” a scene that actually preceded yesterday's performance.

This scene also reveals something of the soul life of Johannes Thomasius – and in such a way that this soul life is not meant in an allegorical or symbolic sense, but is to be portrayed as it presents itself through sensory-supersensory vision. First, a double choir will appear: a choir with gnome-like figures and a choir with sylph-like figures. The purpose of the gnome choir is to show how those soul forces that are more on the intellectual side are at work in the soul of Johannes Thomasius; the sylph choir shows how those forces that are more on the emotional and sentimental side are at work.

The reason why one is compelled to resort to such nature-spirit-like scenes when depicting the soul life of a human being is that, in reality, the connection between human beings and nature is such that it cannot be exhausted in an abstract lawfulness, as we are accustomed to in our present-day understanding. One can ponder at length how the relationship between humans and nature can be expressed in such laws alone in a scientifically justified manner. Since this is not the case, and since one must be guided by reality and not by human cognitive requirements, one must resort to that which expresses the relationship between humans and matter in a realistic way.

But when a person is engaged in genuine self-reflection—as is the case with Johannes Thomasius—then at certain moments in their life they also come particularly close to nature. They then feel, in a sense, particularly connected to nature. And this connection is to be represented by the chorus of gnomes, which reveals itself from nature as a reign of purely intellectual, cunning, and ironic powers, and by the chorus of sylphs, which reveals everything that can be imagined in nature in terms of soul forces and emotional forces when one remembers the soulfulness of nature from within. Then three figures appear, complemented by a fourth: Philia, Astrid, Luna, and the other Philia.

These figures appear because it is necessary to show – again, not in a symbolic way, but just as such things appear to the discerning, supersensible gaze – [because] it is necessary to show what Johannes Thomasius brings about, on the one hand, in self-contemplation. That which, I would say [gap in the text], is experienced by the human soul is expressed through that which works in the figure of Philia. The figure of Astrid expresses that which wisely glows through the soul. And the figure of Luna expresses everything that represents strength of character, that appeals to strength of character. The other Philia expresses precisely that which threatens to lead people out of their soul forces — I would say out of their own heads — into a mystical revelry. All these soul paths come into consideration when people face true self-contemplation.

Once again, as yesterday, we are confronted with the spirit of John's youth, that is, the youthful John himself, but for him it has become as objective as an external entity, so that for him, this youth, it has special destinies. [It enters] into a relationship with the Luciferic world, represented by Lucifer, and is even so objectified from John [that] John Thomasius can see it as another personality — Theodora, who appears in all four mystery plays, representing a kind of retarded clairvoyance, who thus in a certain way looks into the spiritual world, [can see] how these [figures] will behave in it — [how Theodora] will intervene in the fate of the spirit of Johannes' youth in a certain way.

Thus, the soul life of John — captured at a certain moment — is presented on stage, dramatically performed. Everywhere, the aim is to bring the characters to life, not to let them become straw allegories or abstractions. This can then be achieved in a particularly stylized way through those qualities of eurythmy that I have often described here.

For in fact, what is portrayed in these “mystery dramas” in the supersensible world is conceived in such a way that it already contains an inner eurythmy—also a thought eurythmy—so that, basically, the content of these “mystery dramas” can be translated into the visible language of eurythmy as a matter of course.

Today we will arrange the performance so that all kinds of poetic works are presented in the first part, and there will be an intermission after the performance of “Artemis.” After the intermission, the dramatic scene just discussed will be performed first, followed by Goethe's poems.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Die Aufführung fand im Kuppelraum des Goetheanum statt.

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Ich werde mich auch heute darauf beschränken, nur einige Worte zu sagen darüber, dass jetzt eine Stilisierung, die bei dem bühnenmäßig Dargestellten durch die Eurythmie ganz besonders zur Geltung zu bringen möglich ist, heute zur Darstellung kommen soll bei einigen Stücken aus den von mir versuchten «Mysteriendramen». Wir werden heute im zweiten Teil unserer heutigen Vorstellung eine Szene aus «Der Seelen Erwachen» aufführen, und zwar eine Szene, die im Stück sogar dem gestern Aufgeführten voranging.

Auch in dieser Szene kommt ja gerade etwas von dem Seelenleben des Johannes Thomasius - und zwar so, dass dieses Seelenleben wiederum nicht in allegorischer oder symbolischer Beziehung gemeint ist, sondern so, wie es sich darstellt durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen, soll es zur Darstellung gelangen. Es wird zuerst auftreten ein zweifacher Chor: ein Chor mit gnomenartigen Gestalten und ein Chor mit sylphenartigen Gestalten. Der Gnomenchor hat den Sinn, zu zeigen, wie in der Seele des Johannes Thomasius wirksam sind diejenigen Seelenkräfte, die mehr nach der Verstandesseite hin liegen; der Sylphenchor wie diejenigen Kräfte wirksam sind, die mehr nach der Gefühls- und Gemütsseite hin liegen.

Dass man genötigt ist, wenn man das Seelenleben eines Menschen darstellt, zu solchen naturgeistartigen Szenen zu greifen, das liegt ja daran, dass in Wirklichkeit der Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Natur so ist, dass er sich keineswegs in einer abstrakten Gesetzmäßigkeit, wie wir sie in unserer heutigen Erkenntnis gewohnt sind zu geben, erschöpfen lässt. Man kann lange darüber Betrachtungen anstellen, wie das Verhältnis des Menschen zur Natur in solchen Gesetzen allein wissenschaftlich gerechtfertigt sich ausdrücken lasse. Da es eben nicht so ist und da man sich nach der Wirklichkeit und nicht nach den menschlichen Erkenntnisanforderungen richten kann, so muss man zu demjenigen greifen, was eben in einer realen Weise das Verhältnis des Menschen zum Stoff zum Ausdrucke bringt.

Wenn aber der Mensch in einer wirklichen Selbstschau drinnen steht - wie das bei Johannes Thomasius der Fall ist -, dann kommt er auch in gewissen Momenten seines Lebens der Natur ganz besonders nahe. Er fühlt sich dann der Natur gewissermaßen ganz besonders verbunden. Und diese Verbundenheit soll dargestellt werden durch den Gnomenchor, der eben gerade aus der Natur heraus sich offenbart wie ein Walten von rein verstandesmäßig schlau-ironischen Mächten, und durch den Sylphenchor, der alles dasjenige offenbart, was an Seelenkräften, an Gemütskräften in die Natur hinein sich denken lässt, wenn man eben von innen der Natur sich erinnert Seelenhaftigkeit. Dann treten auf drei Gestalten, die durch eine vierte ergänzt werden: Philia, Astrid, Luna und die andere Philia.

Diese Gestalten treten aus dem Grunde auf, weil vor Augen geführt werden soll - wiederum nicht in symbolischer Weise, sondern eben so, wie sich so etwas vor dem erkennenden, übersinnlichen Schauen ausnimmt -, [weil] vor Augen geführt werden soll, was durch Johannes Thomasius wirkt, auf der einen Seite bei der Selbstschau. Dasjenige, was, ich möchte sagen [Lücke in der Textvorlage] Erlebtes für die MenschenSeele ist, drückt sich aus durch dasjenige, was in der Gestalt der Philia wirkt. In der Gestalt der Astrid drückt sich aus dasjenige, was weisheitsvoll die Seele durchglüht. Und in der Gestalt der Luna alles dasjenige, was Charakterfestigkeit darstellt, was an die Charakterfestigkeit appelliert. In der anderen Philia drückt sich schon eben dasjenige aus, was den Menschen aus seinen Seelenkräften heraus — ich möchte sagen über seinen eigenen Kopf [heraus] - in ein mystisches Schwelgen droht hineinzuführen. Alle diese Seelenwege kommen ja in Betracht, wenn der Mensch vor einer wahren Selbstschau steht.

Wiederum so wie gestern steht vor uns der Geist von Johannes’ Jugend, das heißt der jugendliche Johannes selber, aber für ihn so objektiv geworden wie eine äußere Wesenheit, sodass sie für ihn, diese Jugend, besondere Schicksale hat. [Sie kommt] in ein Verhältnis zu der luziferischen Welt, die durch Luzifer repräsentiert auftritt, und sogar so objektiviert aus Johannes [abgesondert ist], dass Johannes Thomasius sehen kann, wie eine andere Persönlichkeit — die Theodora, die durch alle vier Mysterienstücke geht, die eine Art von zurückgebliebenem Hellsehen darstellt, die also in einer gewissen Weise hineinschaut in die geistige Welt, [sehen kann,] wie diese [Gestalten] darin sich verhalten werden -, [wie Theodora] in das Schicksal des Geistes von Johannes’ Jugend in einer bestimmten Weise eingreifen [wird].

So wird das Seelenleben des Johannes - in einem bestimmten Momente festgehalten - bühnenmäßig dargestellt, dramatisch vorgeführt. Es wird überall angestrebt, die Gestalten lebendig zu machen, nicht zu strohernen Allegorien, abstrakt werden zu lassen. Das kann dann durch jene Eigenschaften der Eurythmie, die ich ja öfters schon von dieser Stelle aus dargelegt habe, auch besonders stilisiert auftreten.

Denn in der Tat ist dasjenige, was in diesen «Mysteriendramen» hinüberspielt in die übersinnliche Welt, überall so gedacht, dass es schon eine innere Eurythmie — auch eine Gedankeneurythmie - in sich hat, sodass im Grunde genommen wie selbstverständlich sich das, was Inhalt in diesen «Mysteriendramen» ist, in die sichtbare Sprache der Eurythmie umsetzen lässt.

Wir werden die Vorstellung heute so einrichten, dass allerlei Dichterisches im ersten Teil zur Darstellung kommt und eine Pause wird sein nach der Darstellung der «Artemis». Nach Verlauf dieser Pause wird zunächst die eben besprochene dramatische Szene zur Aufführung kommen und dann Goethe’sche Dichtungen.