The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1920–1922

GA 277c

23 August 1922, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Address on Eurythmy

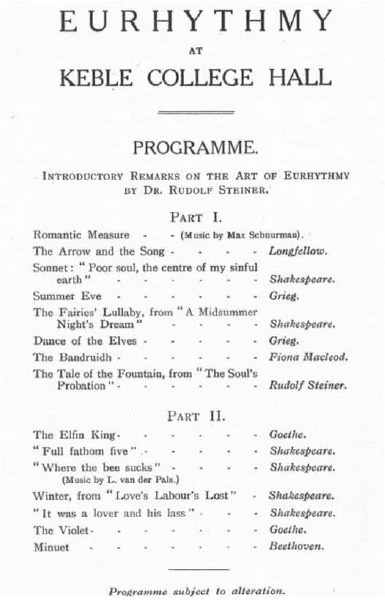

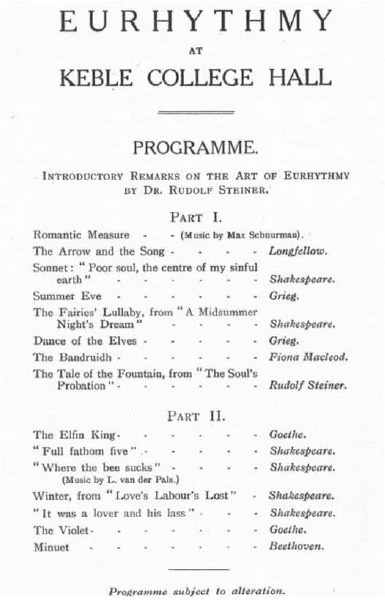

Program for the performance

Allow me to say a few words about the significance of eurythmy lessons and the education that children can gain from them. I would like to explain this using the figures that were made in the studio in Dornach, which represent in a certain artistic way what eurythmy is actually about. First of all, however, these figures are intended to provide a basis for the artistic perception of eurythmy. But I will also be able to use these figures to explain individual points relating to pedagogy and didactics. The point is that eurythmy is truly a visible language, not a mimetic expression, not a pantomimic expression, and not ordinary dance art either. Just as a person brings partial organs into activity when singing or speaking, so too can the whole person be brought into those movements that the larynx and its neighboring organs actually want to perform. But they do not get to do so; they suppress them immediately, and then the other movements take place in such a way that what actually wants to become, let us say, this movement in the larynx, so that the laryngeal wings open outwards: a, this is undermined at the moment of its emergence, in the status nascendi, and is transformed into a movement into which the thought content of language can be transferred, and into a movement that can then pass into the air and be heard. The underlying movement, the inner human movement, let's say of the a, you have it here [the figure is shown]. This is what the whole human being wants to do when he bursts out in a. And so every utterance of song and speech can be made visible in the movement that the whole human being actually wants to perform, but which is held back in the status nascendi. In this way, one can arrive at every such form of movement. Just as there are formations of the larynx and the other speech organs for a, i, I m, so there are the corresponding movements, forms of movement. These forms of movement are therefore the revelation of the will, for which the revelations of thought and will otherwise exist in speech and singing. The intellectual, the purely abstract intellectual, which is in language, is taken out here and everything that wants to be expressed is transferred into the movement itself, so that eurythmy is, in the broadest sense, an art of movement. Just as you can hear the a, you can see the a; just as you can hear the i, you can see the i.

Now, the aim in these figures is that the movement is captured above all in the plastic design of the wood. The basic color is there, which is actually supposed to express the form of movement everywhere, but just as feeling flows into our spoken language, so too can feeling flow down into movement. For we do not just speak a sound, we also give the sound a feeling coloration. We can do this in eurythmy as well. And here a strong subconscious element comes into play in eurythmy. If the actor, the performer, is able to artistically incorporate this feeling into their movement, then one will also feel this feeling when one sees the eurythmic movements. Here, it is also taken into consideration that the veil that is worn should follow these feelings. So that what is used here as a second color, preferably on the veil, represents the emotional nuance for the movement. So you have a first basic color that expresses the movement itself, and a second color superimposed on it, which is preferably expressed in the veil and expresses the emotional nuance. But the eurythmic actor must have the inner strength to put this feeling into the movement, just as it makes a difference whether I say to someone: Come to me! in a commanding tone, or: Come to me! in a friendly invitation. That is the emotional nuance. So what is expressed here in the second color and then continued in the veil represents the emotional nuance of eurythmic language. And the third brings in character, the strong element of will. This only comes into eurythmy because the eurythmic actor is able to empathize with his movements and express them within himself. The head of a eurythmic actor looks completely different depending on whether he tenses the muscles on the left side of his head and leaves the right side somewhat relaxed, as is indicated here, for example, by the third color. You can observe this: the third color always indicates the element of will. Here, for example, something is tensed on the left side, and here across the mouth; here the forehead is slightly tensed, the muscles of the forehead slightly tensed. This then gives the whole an inner character, radiating from this gentle tension, because what is gently tensed here radiates throughout the whole organism. And from this movement, which is expressed by the basic color, from the emotional nuance, which is expressed by the second color, and from this element of will — the whole element is an element of will, but the will is added to it in a special way — the actual art of eurythmy is composed.

If one therefore wants to capture anything eurythmically, one must extract from the human being that which is purely eurythmic. If there were figures here with beautifully painted noses and eyes and beautiful mouths, they could be beautiful paintings: but that is not what eurythmy is about; here, only what is eurythmic in the eurythmic person is painted and formed.

The person performing eurythmy is such that their specific face is not important. It does not matter. Of course, a healthy eurythmist does not automatically make a grumpy face when performing a joyful movement, but that is also the case when speaking. But a physiognomy of the face that is not eurythmic is not what is sought. For example: someone can make a “movement” by holding the axis of their eyes outward. That is eurythmic, that works. But it is not acceptable for anyone, as is the case in the art of mime, to make special little movements with their eyes – as we say in German – which look like grimaces, which are often required as a special facial expression. Everything about the eurythmist must be eurythmic.

Therefore, in a kind of expressive art, what is purely eurythmy was brought out of the human being, everything else was left out, and in this way one actually only obtains an artistic expression. For it is the case in all art that only with certain artistic means can one express what art can represent. You cannot make a statue speak: you must therefore express what you want to convey as a spiritual expression in the shaping of the mouth, of the whole face. So it is of no use to paint naturalistic people here, but rather to paint what immediately comes out as eurythmic. Now, of course, when I speak of the veil here, one cannot change the veil after every sound: but one gradually discovers that once one has put oneself into this emotional nuance, into this mood for a poem, then the whole poem has a "mood or a b-mood. Then you can arrange the whole poem in a certain veil color.

The same applies to the color scheme. Here, I have depicted the veil, shape, color combination, and so on for each individual sound. In a poem, you have to have a basic note, so to speak. The basic note then determines the color of the veil, the entire composition that you have to maintain throughout the poem, otherwise the ladies would have to constantly change their veils, constantly throw off veils, put on other veils, and things would become even more complicated than they already are, and people would say they understand them even less. But it is certainly the case that once you have the sound mood, you can maintain it throughout an entire poem, varying only the movement, the transition from one sound to another, from one syllable to another, from one mood to another, and so on. Now, since I have educational and didactic purposes today, I have arranged the eurythmy figures here so that you can see them in the order in which the child learns the sounds. From an early age, children learn sounds in such a way that the first sound is essentially the one that sounds like “a.” Progressing in this order, approximately of course—there are all kinds of variations among children—but in this order approximately: a, e, o, u, i are the vowels that are learned on average by small children. When children are allowed to practice this visible language of eurythmy in this way, it is like a resurrection of what they experienced when learning sounds as very young children, like a resurrection on another level. The child experiences once again what it experienced earlier in this eurythmic language. And it is a reinforcement of what lies in the word, through the means of the whole human being.

Then, with the consonants, the children learn m, b, p, d, t, l, n: there should also be an ng, as in “gingen” (went), for example, which is not yet formed; then f, h, g, s, r. r, this mysterious letter, which actually has three forms in human language, is only mastered by children at the very end. There is a lip r, a tongue r, and an r that is pronounced completely backwards.

So what the child learns in language in a partial organism, in the speech organism and in the singing organism, can be transferred to the whole person and developed into visible language.

If there is sufficient interest in this kind of expressionistic art, we will then be able to develop further aspects such as joy, sadness, antipathy, sympathy, and other emotions that can be expressed in eurythmy. Not only grammar but also rhetoric has its place in eurythmy. We will be able to train all of this. Then we will see how this spiritual-soul gymnastics, which not only has a physiological effect on the physical human being, but also forms the human being spiritually, soulfully, and physically, can indeed have its pedagogical-didactic value on the one hand and its artistic value on the other.

Now, allow me to add in parentheses that these figures can be used by eurythmy students to memorize after eurythmy lessons. For one should not believe that eurythmy is something so easy that it can be taught in a few hours. Eurythmy must be learned thoroughly, but such eurythmy figures can also serve as a means of repetition for those who seek eurythmic art, enabling them to delve deeper into it. One will see that there is a great deal to be found in the forms themselves, which are relatively simply carved and painted here.

That is what I wanted to say today about eurythmic art, namely insofar as it can be integrated into the pedagogical-didactic principle that we seek to cultivate in the Waldorf school.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Programm zur Aufführung

Gestatten Sie, dass ich noch ein paar Worte spreche über die Bedeutung des eurythmischen Unterrichts und der Erziehung, welche für das Kind gerade aus dem Eurythmie-Unterricht hervorgehen kann. Ich möchte das erläutern an den Figuren, die im Atelier in Dornach gemacht worden sind und die in einer gewissen künstlerischen Weise darstellen werden dasjenige, was eigentlich der Inhalt des Eurythmischen ist. Zunächst sind diese Figuren allerdings mehr bestimmt, eine Grundlage zu geben für die künstlerische Anschauung der Eurythmie. Ich werde aber auch in der Lage sein, in Bezug auf das PädagogischDidaktische gerade aus diesen Figuren heraus einzelnes vor ihnen klarzumachen. Es handelt sich darum, dass ja die Eurythmie wirklich eine sichtbare Sprache ist, keine mimische Äußerung, keine pantomimische Äußerung und auch keine gewöhnliche Tanzkunst. Geradeso wie der Mensch partielle Organe in Regsamkeit, in Tätigkeit bringt, wenn er singt oder wenn er spricht, so kann man auch den ganzen Menschen in diejenigen Bewegungen bringen, die eigentlich der Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane ausüben wollen. Aber sie kommen nicht dazu, sie unterdrücken sie gleich, und da werden die anderen Bewegungen, die dann so verlaufen, dass sich dasjenige, was eigentlich im Kehlkopf, sagen wir, diese Bewegung werden will, sodass sich die Kehlkopfflügel nach außen öffnen: a, das wird im Moment des Entstehens, im Status nascendi untergraben, wird in eine solche Bewegung verwandelt, in die der Gedankeninhalt der Sprache hineinversetzt werden kann, und in eine Bewegung, die dann in die Luft übergehen kann und gehört werden kann. Die zugrundeliegende Bewegung, die eigentlich innermenschliche Bewegung, sagen wir des a, Sie haben sic hier /die Figur wird gezeigt]. Das will der ganze Mensch machen, wenn er in a ausbricht. Und so kann man jede Äußerung des Gesanges und der Sprache in der Bewegung, die eigentlich der ganze Mensch ausführen will, aber im Status nascendi aufhält, sichtbar machen. So kann man zu jeder solchen Bewegungsform kommen. Geradeso wie es Formungen gibt des Kehlkopfes und der anderen Sprachorgane für a, i, I m, so gibt es die entsprechenden Bewegungen, Bewegungsformen. Diese Bewegungsformen, sie sind daher diejenige Offenbarung des Willens, für die sonst die Offenbarungen des Gedankens und des Willens, im Sprechen und Singen bestehen. Das Gedankliche, das rein abstrakte Gedankliche, das in der Sprache ist, wird hier herausgenommen und alles, was sich aussprechen will, in die Bewegung selbst hineinversetzt, sodass die Eurythmie im weitesten Sinne eine Bewegungskunst ist. Genau ebenso, wie Sie das a hören können, können Sie das a anschauen, wie Sie das i hören können, können Sie das i anschauen.

Nun ist in diesen Figuren das angestrebt, dass in der plastischen Gestaltung des Holzes die Bewegung vor allen Dingen festgehalten ist. Es ist die Grundfarbe da, die eigentlich überall die Bewegungsform zum Ausdruck bringen soll, aber wie in unsere Lautsprache das Gefühl hineinströmt, so kann das Gefühl auch hinunterströmen in die Bewegung. Denn wir sprechen ja nicht nur einen Laut, sondern wir geben dem Laute eine Gefühlsfärbung. Das können wir auch in der Eurythmie. Und da wirkt ein stark unterbewusstes Element in die Eurythmie hinein. Wenn der Akteur, der Darsteller imstande ist, dieses Gefühl künstlerisch in seine Bewegung hineinzulegen, dann wird man dieses Gefühl auch mitfühlen, wenn man die eurythmischen Bewegungen sieht. Hier ist noch das in Betracht gezogen, dass der Schleier, der getragen wird, diesen Gefühlen folgen soll. Sodass also dasjenige, was hier als zweite Farbe vorzugsweise auf den Schleier verwendet ist, darstellt die Gefühlsnuance für die Bewegung. Sie haben also eine erste Grundfarbe, die drückt die Bewegung selber aus, eine zweite daraufgesetzte Farbe, die vorzugsweise im Schleier zum Ausdrucke kommt, die drückt die Gefühlsnuance aus. Aber der eurythmische Akteur muss die innere Kraft haben, dieses Gefühl in die Bewegung hineinzulegen, so wie es einen Unterschied macht, ob ich zu jemandem sage: Komm zu mir! - befehlend - oder: Komm zu mir! - freundlich auffordernd. Das ist die Gefühlsnuance. So stellt dasjenige, was hier in der zweiten Farbe zum Ausdrucke kommt und was dann in den Schleier hinein fortgesetzt wird, die Gefühlsnuance der eurythmischen Sprache dar. Und das Dritte bringt Charakter, das starke Willenselement hinein. Das kommt nur dadurch in die Eurythmie hinein, dass der eurythmische Akteur in der Lage ist, mitzuempfinden seine Bewegungen und dass er sie in sich selbst ausdrückt. Der Kopf eines eurythmischen Akteurs sieht ganz anders aus, ob er die Muskeln im linken Haupte etwas spannt und im rechten etwas schlaff lässt. wie es zum Beispiel hier angedeutet ist durch die dritte Farbe. Sie können das beobachten, immer die dritte Farbe zeigt das Willensmäßige an. Hier zum Beispiel wird an der linken Seite etwas gespannt, und hier über den Mund hinüber; hier wird die Stirne etwas gespannt, die Muskeln der Stirne etwas gespannt. Das gibt dann — ausstrahlend von dieser leisen Spannung, denn das strahlt in den ganzen Organismus aus, was da leise gespannt wird -, das gibt dem Ganzen einen innerlichen Charakter. Und aus dieser Bewegung, die durch die Grundfarbe ausgedrückt ist, aus der Gefühlsnuance, die durch die zweite Farbe ausgedrückt wird, und aus diesem Willenselemente — das ganze Element ist Willenselement, aber da wird der Wille noch besonders draufgesetzt -, aus dem setzt sich die eigentliche eurythmische Kunst zusammen.

Will man daher irgendetwas eurythmisch festhalten, so muss man aus dem Menschen heraussondern dasjenige, was bloß eurythmisch ist. Würden hier Figuren stehen mit schön gemalten Nasen und Augen und schönem Mund, das könnten ja schöne Malereien sein: aber bei der Eurythmie handelt es sich nicht darum, hier ist nur das gemalt und gebildet, was das Eurythmische am eurythmisierenden Menschen ist.

Der eurythmisierende Mensch ist so, dass es bei ihm auf das spezielle Gesicht nicht ankommt. Es kommt nicht darauf an. Es ist natürlich so, dass von selbst bei einem gesunden Eurythmisierenden nicht zu einer freudigen Bewegung ein griesgrämiges Gesicht gemacht wird, aber das ist ja sonst auch, wenn man spricht, der Fall. Aber eine Physiognomie des Gesichtes, die nicht eurythmisch ist, die wird nicht angestrebt. Zum Beispiel: Es kann einer eine «-Bewegung dadurch machen, dass er die Augenachse nach außen hält. Das ist eurythmisch, das geht. Aber es geht nicht, dass irgendeiner, so wie es in der mimischen Kunst ist, besondere Kinkerlitzchen - so sagt man im Deutschen — mit den Augen macht und das sieht aus wie eine Grimasse, was man oftmals verlangt als einen besonderen mimischen Ausdruck des Gesichtes. Es muss am Eurythmisierenden alles eurythmisch sein.

Daher wurde hier einmal in einer Art Expressionskunst dasjenige aus dem Menschen herausgeholt, was nur Eurythmie ist, alles andere weggelassen, und man bekommt eigentlich auf diese Weise nur einen künstlerischen Ausdruck. Denn es ist ja in aller Kunst so, dass man nur mit gewissen Kunstmitteln dasjenige zum Ausdrucke bringt, was eben eine Kunst darstellen kann. Sie können eine Statue nicht sprechen lassen: Sie müssen also in der Formung des Mundes, des ganzen Gesichtes dasjenige ausdrücken, was Sie als seelischen Ausdruck haben wollen. So nützt es auch nichts, hier naturalistische Menschen zu malen, sondern das zu malen, was unmittelbar als Eurythmisches herauskommt. Nun ist es natürlich, dass, wenn ich hier vom Schleier spreche, man nicht nach jedem Laut den Schleier wechseln kann: aber man findet allmählich heraus, dass, wenn man einmal in diese Gefühlsnuance, in diese Stimmung sich hineinversetzt für ein Gedicht, dann hat ein ganzes Gedicht eine «-Stimmung oder eine b-Stimmung. Dann kann man für das ganze Gedicht in irgendeiner Schleierfarbe die Sache zurechtmachen.

Ebenso ist cs mit der Farbgestaltung. Hier habe ich für jeden einzelnen Laut Schleier, Form, Farbenzusammenstellung und so weiter dargestellt. Man muss bei einem Gedicht gewissermaßen die Grundnote haben. Die Grundnote gibt dann die Schleierfarbe, überhaupt die ganze Zusammenstellung, die man durch das Gedicht festhalten muss, sonst müssten sich die Damen die Schleier fortwährend wechseln, fortwährend Schleier abwerfen, andere Schleier anziehen, und die Sache würde noch komplizierter werden, als sie schon ist, und die Leute würden sagen, sie verstehen sie noch weniger. Aber cs ist durchaus so: Hat man einmal die Lautstimmung, kann man sie auch durch ein ganzes Gedicht festhaltend und nur durch die Bewegung variierend den Übergang von einem Laut zum anderen, einer Silbe zur anderen, von einer Stimmung zur anderen und so weiter machen. Nun, ich habe, da ich heute pädagogisch-didaktische Zwecke habe, hier die Eurythmiefiguren so aufgestellt, dass Sie sie in der Reihenfolge sehen, wie das Kind die Laute lernt. Das Kind lernt von klein auf die Laute so, dass der erste Laut im Wesentlichen derjenige ist, der als a tönt. In dieser Reihenfolge fortgeschritten, ungefähr natürlich — es gibt alle möglichen Abweichungen bei Kindern -, aber in dieser Reihenfolge ungefähr: a, e, o, u, i werden die Vokale durchschnittlich angeeignet vom kleinen Kinde. Wenn man in dieser Weise wiederum diese sichtbare Sprache der Eurythmie von dem Kinde ausüben lässt, dann ist es wie cine Auferstehung desjenigen, was das Kind erlebt hat beim Lautelernen als ganz kleines Kind, wie eine Resurrektion, wie eine Auferstehung auf einer anderen Stufe. Das Kind erlebt noch einmal das, was es früher erlebt hat, in dieser eurythmischen Sprache. Und es ist das eine Befestigung desjenigen, was in dem Worte liegt, durch die Mittel des ganzen Menschen.

Dann, bei den Konsonanten ist es so, dass die Kinder lernen m, b, p, d, t, l, n: da würde noch ein ng sein müssen, wie zum Beispiel in «gingen», das ist noch nicht gebildet; dann f, h, g, s, r. r, dieser geheimnisvolle Buchstabe, der eigentlich drei Formen in der menschlichen Sprache hat, wird in Vollkommenheit erst zuletzt von den Kindern ausgeführt. Es gibt ein Lippen-r, ein Zungen-r und ein r, das ganz rückwärts gesprochen wird.

So also kann man dasjenige, was das Kind in der Sprache in einem Partialorganismus, im Sprachorganismus und im Gesangsorganismus lernt, das kann man auf den ganzen Menschen übertragen, zur sichtbaren Sprache ausbilden.

Wir werden dann, wenn einiges Interesse vorhanden sein sollte für solch eine expressionistische Kunst, auch weiteres ausbilden können, wie zum Beispiel Freude, Traurigkeit, wie Antipathie, Sympathie und anderes, was ja alles in Eurythmie darzustellen ist. Nicht nur die Grammatik, sondern auch die Rhetorik kommt in der Eurythmie zurecht. Wir werden das alles ausbilden können. Dann wird man sehen, wie tatsächlich auch dieses geistig-seelische Turnen, das nicht nur in den physischen Menschen physiologisch hineinwirkt, sondern geistig-scelisch und leiblich-körperlich den Menschen bildet, in der Tat auf der einen Seite seinen pädagogischen-didaktischen Wert, auf der anderen Seite seinen künstlerischen Wert haben kann.

Nun, gestatten Sie, dass ich nur in Parenthese eben hinzufüge, dass diese Figuren von dem Eurythmielernenden nach dem Eurythmieunterricht zum Memorieren dienen können. Denn man soll nur ja nicht glauben, dass Eurythmie etwas so Leichtes ist, dass man es in ein paar Stunden sich beibringen kann. Eurythmie muss wirklich gründlich erlernt werden: aber zum Wiederholen können solche Eurythmiefiguren auch für diejenigen dienen, die eurythmische Kunst suchen, zum Weiter-sich-Hineinvertiefen. Man wird schon sehen, dass in den Formen selber, die hier verhältnismäßig einfach geschnitzt und bemalt sind, sehr viel liegt.

Das ist dasjenige, was ich heute sagen wollte über die eurythmische Kunst, namentlich insofern sie sich einfügen kann in das pädagogischdidaktische Prinzip, wie wir es in der Waldorfschule zu pflegen suchen.