The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1920–1922

GA 277c

31 December 1922, Berlin

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Address on Eurythmy

This performance, which took place at 5 p.m. in the dome room of the Goetheanum, was to be the last performance there, because on New Year's Eve the First Goetheanum burned down completely.

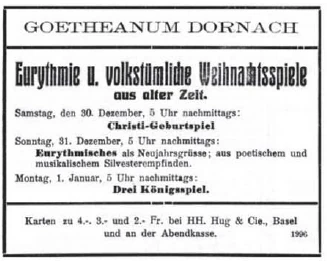

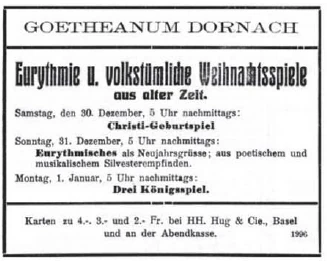

Draft announcement and newspaper advertisement for the performances, December 30, 1922, to January 1, 1923

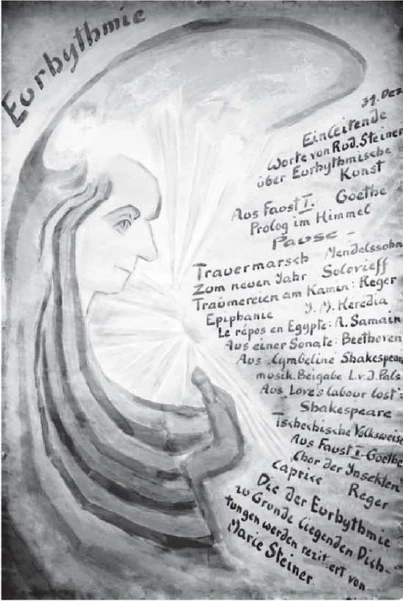

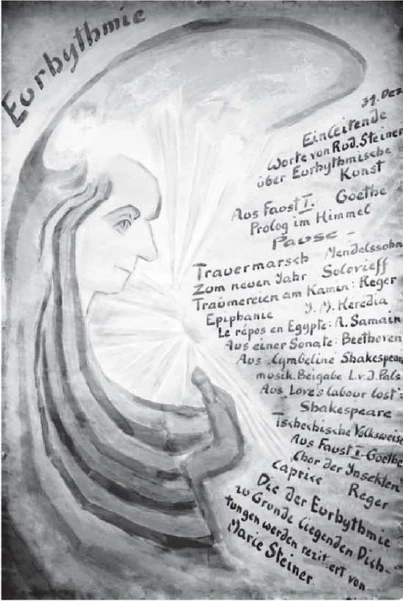

Poster for the performance

“Prologue in Heaven” from “Faust I” by J. W. v. Goethe

“Funeral March” by F. Mendelssohn Bartholdy

“To the New Year” by Vladimir Solovyov

“Träumerei” by Max Reger

“Epiphany” by Jose-Maria de Heredia

“Repos en Egypte” by Albert Samain

‘Allegro’ by L. v. Beethoven

“Amien's Song: It was a lover” from “As You Like It” by William Shakespeare

Cheerful overture with music by Leopold van der Pals

“Winter: When icicles hang” from “Love's Labour's Lost” by William Shakespeare

Czech folk song

“Chorus of Insects” from “Faust II,” Act 2 (Study) by J. W. v. Goethe

“Caprice” by Max Reger

Ladies and gentlemen!

Today, in the first part before the intermission, we will present the “Prologue in Heaven” and in the second part, poetic-musical works, poems, and musical pieces performed as eurythmy. I would like to take this opportunity, as usual, to say a few words about the nature of eurythmy. Eurythmy is derived from artistic sources that are still more or less unfamiliar today, and it also works in an artistic formal language that is equally unfamiliar. Eurythmy is a truly visible language.

Just as the human organism unconsciously develops the ability in early childhood to reveal itself spiritually through sound in song—which can then be trained—or through speech, so that the revelation is received by the sense of hearing, so too can that which is experienced spiritually reveal itself externally, not only in audible song or audible speech, but in visible song or visible speech, which lies in the movements [of the limbs] of the individual human being or in the movements or positions of groups of people. This has nothing to do with gestures that are merely mimetic, nor does it have anything to do with dance, but rather with the fact that, just as those movements of the human being that originate unconsciously or semi-consciously from the larynx and the other speech and vocal organs, unconsciously or semi-consciously want to come out of the human being in order to be transmitted through the air and thus be heard audibly, that in the same way, what underlies human soul life as emotional content can be expressed through the movement of human limbs, especially through the movement of the most expressive human limbs, the arms and hands.

If one studies correctly, through sensual-supersensual observation—to use Goethe's expression—how the whole system of the larynx and other internal movements is connected with the movements of the air, and if one then transfers this with the appropriate metamorphosis to the human arms and hands in particular, then one obtains a range of gestures to which the ordinary gestures – with which we accompany our speech in order to aid understanding – to which these simpler gestures, indeed the simpler facial expressions used by actors, relate like the babbling of a child to truly articulated, trained speech or to trained singing.

So the ordinary facial expressions, the ordinary gestures, would actually be the babbling, and what one discovers through a precise study, a sensual-supersensual study of the movement possibilities of the human organism, is then the visible, trained singing or the visible, trained speech. And everything that the soul can otherwise express through singing or speech can also be expressed through this visible language, through this visible singing.

However, it must be taken into account that, on the one hand, what eurythmy is — although this transition should not be too pronounced — merges into ordinary gestures; ordinary facial expressions must not be confused with eurythmy gestures. On the other hand, what eurythmy is – this becomes apparent the more a person performs dance-like movements, the more what they express in form, in rhythm, in the rhythm of the movements, corresponds to music. But the more a person sets their organism in motion with their soul, which flows into the articulation of the hands, into the articulation of the arms, the more they perform movements in this way, the more these movements become a visible linguistic expression. So that on the one hand, you will see in our presentation how music is accompanied by such movements. People sing visibly, whereas otherwise they sing audibly. Likewise, you will hear poetry recited and declaimed, accompanied by eurythmic movements of the whole person, of groups of people, and accompanied in particular by the movement of the arms and hands.

This movement of the arms and hands is now a perfect expression of what poetry is – just like spoken language itself. However, while the movements of the arms and hands, in the movements of the whole person during visible singing, actually express more of what accompanies the music as feelings from the soul, eurythmic speech, when used correctly, actually brings everything pictorial, melodious, rhythmic, and also the content of the language to a real revelation. This enables us to bring to visible expression what the poet puts into his work of art as, I might say, an inner eurythmy, as an expression of the whole human being. And this gives us the opportunity to express the dramatic and poetic in a higher style than through ordinary facial expressions.

This can be seen particularly clearly in a poem such as the one that was just performed eurythmically before the break, Goethe's “Prologue in Heaven.” A powerful, grandiose image of angelic figures appears before us, speaking to reveal the intentions of the worlds. It is accompanied by what Mephisto has to say. But everything that relates to the supersensible as experiences of the human soul can be expressed particularly well through this higher stylization of eurythmy. And once you are familiar with eurythmy, you immediately feel the need to move away from the usual naturalistic mimicry for those scenes that relate to the supersensible, and in this way also to achieve a more perfect stage representation of such scenes, as Goethe's “Prologue in Heaven” represents.

Of course, one could also express what Mephisto has to say in eurythmic form. However, insofar as human beings also live as soul-spiritual-supernatural beings, it is precisely this inner being that is expressed and revealed through eurythmic speech movements. And we can also apply this when we want to express angelic beings. However, we have not yet invented devil eurythmy, and so Mephisto still has to be portrayed today using entirely naturalistic facial expressions. Perhaps one day we will succeed in discovering the corresponding “devil language” – I mean in eurythmic form – and then this too can be portrayed eurythmically.

But we are really striving to shape the whole stage setting more and more according to eurythmy. And this reveals something that is particularly interesting. For some time now, we have been striving to support what is to be portrayed poetically or musically, and also eurythmically, with appropriate lighting on the stage, which must harmonize with the costumes of the individual characters performing eurythmically. And here something peculiar becomes apparent.

For example, when performing something purely musical – instrumental music, I mean – it is possible, under certain circumstances, to use lighting effects to create parallel phenomena, parallel light phenomena, which in their sequence produce an impression similar to that of the musical form or musical content. But it is quite different to do something like this in an opera performance, for example, than to do it in our eurythmic performance. In opera, one always has the feeling that the lighting effects are really just something like an accompaniment to the work of art, something that is added to the work of art from outside, whereas here the lighting effects are strictly internal, connected with the work of art, namely with the eurythmic work of art. So that one also gets the feeling: just as the mood when singing emanates from the human being, so to speak, emanates to all sides of the room, and just as one could represent this emanating mood as light effects, so the whole mood that the stage design must bring about through lighting effects in a eurythmic performance this mood is like something that does not radiate from the eurythmic figures, but rather has the effect of the eurythmic figures absorbing these bodies of light, these masses of light, as if they were moving toward them, as if they needed them.

In short, all kinds of peculiarities of this visible language, this eurythmy, will be discovered over time. Today, it is really only in its infancy. On the one hand, you will find that eurythmy is accompanied by music. There is singing, visible singing. You will find it accompanied by recitation and declamation. There is speech.

Now it has become increasingly apparent that it is actually something quite inorganic and inartistic when the person performing the eurythmic movements wants to speak the words at the same time. It has become apparent that the artistic aspect actually consists in the fact that the person who expresses their soul in movement becomes completely silent to the ear, and that what is presented to the ear is presented separately in recitation and declamation or in instrumental music. Even the singer, if they were to accompany something eurythmic, would have to sing separately, not sing eurythmically themselves. But in this way, one actually obtains within the art of eurythmy, I would say, an expanded orchestra, an orchestra composed of what goes on in the mere visible movement and what is presented musically or declamatorily or recitatively. And this whole interaction is subject to the same orchestral laws as a musical one. One could therefore quite rightly speak of instrumentation in this context.

These things will gradually be discovered from the essence of eurythmy. They have been inherent for a long time. We must bear in mind that eurythmy is still in its infancy and that it will continue to develop further and further. However, it is already apparent that the secrets of language only really reveal themselves when one begins to understand the essence of eurythmy. It is therefore also apparent that recitation and declamation themselves must be transferred from what they are today in a somewhat inartistic age—where the prosaic is actually emphasized or highlighted in poetry, and the essential is sought in the prosaic highlighting of the poetic— that this declamatory and recitative style must in turn be carried over to where Goethe had it, who rehearsed his iambic dramas with his actors according to rhythm and beat — which was much more important to him — as [he] rehearsed his iambs with a baton like a conductor; in other words, less the prosaic content and more the musical and imaginative aspects of speech formation.

In the pictorial shaping of the sound, recitation and declamation actually give rise to something imaginative. By taking into account the melodious, the rhythmic, the metrical, one obtains something musical in language. Simply by introducing these things into recitation and declamation, one can accompany what is offered eurythmically in the right way.

Taking all this into account, I would like to ask my esteemed audience for their indulgence, as always, for the presentation, since it must be emphasized that we are only at the beginning of the development of the art of eurythmy. However, it will certainly be perfected more and more by us or others. Today, however, it can already be said that it will be able to undergo this perfection in an immeasurable way, because it makes use of the most perfect instrument: the human being himself.

And the human being is a microcosm, containing all the secrets of the world, all the laws of the world, animation, spiritualization. If one brings out of him that which can truly be brought out in such an intimate way, by setting the whole human being in motion, then at the same time the secrets of the world express themselves through the human being. And it is indeed true that when Goethe says: When human beings are placed at the summit of nature, they bring together order, measure, harmony, and meaning and reveal these by elevating themselves to works of art — then one can say: Human beings will be able to elevate what lies in the world to a work of art in the most perfect way when they seek order and measure, harmony and meaning in their own organic movement and expression, thereby revealing precisely what lives in their soul and spirit.

Taking this into account, one can truly say that it is already possible today to sense how this eurythmic art, despite being only in the early stages of development, will one day be able to stand alongside the established older arts as a fully-fledged younger art form.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Diese Aufführung, die um 17 Uhr im Kuppelraum des Goetheanum stattfand, sollte die letzte Aufführung dort sein, denn in der Silvesternacht brannte das Erste Goetheanum vollständig nieder.

Ankündigungsentwurf und Zeitungsannonce für die Aufführungen, 30. Dezember 1922 bis 1. Jannar 1923

Plakat für die Aufführung

«Prolog im Himmel» aus «Faust I» von J. W. v. Goethe

«Trauermarsch» von F. Mendelssohn Bartholdy

«Zum neuen Jahr» von Wladimir Solowjow

«Träumerei» von Max Reger

«Epiphanie» von Jose-Maria de Heredia

«Repos en Egypte» von Albert Samain

«Allegro» von L. v. Beethoven

«Amien’s Song: It was a lover» aus «As you like it» von William Shakespeare

Heiterer Auftakt mit Musik von Leopold van der Pals

«Winter: When icicles hang» aus «Love’s Labour’s Lost» von William Shakespeare

Tschechisches Volkslied

«Chor der Insekten» aus «Faust II», 2. Akt (Studierzimmer) von J. W. v. Goethe

«Caprice» von Max Reger

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Wir werden uns erlauben, Ihnen vorzuführen heute im ersten Teil vor der Pause den «Prolog im Himmel» und im zweiten Teil dichterischmusikalische Werke, Dichtungen, musikalische Stücke eurythmisiert. Ich möchte auch bei dieser Gelegenheit - wie sonst - über das Wesen der Eurythmie einige Worte vorausschicken. Eurythmie ist ja entnommen aus künstlerischen Quellen, die bis heute mehr oder weniger ungewohnt sind, und arbeitet auch in einer künstlerischen Formensprache, die ebenso ungewohnt ist. Es handelt sich bei der Eurythmie um eine wirklich sichtbare Sprache.

Geradeso, wie unbewusst aus dem menschlichen Organismus im zarteren Kindesalter die Möglichkeit herauskommt, durch Ton gesanglich - was dann ausgebildet werden kann - oder durch Laute sprachlich sich seelisch zu offenbaren, sodass die Offenbarung vom Gehörsinn empfangen wird, so kann auch dasjenige, was seelisch erlebt wird, sich äußerlich offenbaren nicht nur in einem hörbaren Gesange oder in einer hörbaren Sprache, sondern in einem sichtbaren Gesange oder in einer sichtbaren Sprache, die in Bewegungen [der Glieder] des einzelnen Menschen liegen oder aber in Bewegungen oder Stellungen von Menschengruppen. Dabei hat man es weder zu tun mit Gesten, die ein bloß Mimisches darstellen, noch hat man es mit Tanz zu tun, sondern man hat es damit zu tun, dass ebenso, wie jene Bewegungen des Menschen, die aus dem Kehlkopf und den übrigen Sprach- und Gesangsorganen unbewusst oder halbbewusst aus dem Menschen herauswollen, um sich der Luft zu übertragen und dadurch sich hörbar vernehmen zu lassen, dass in derselben Weise dasjenige, was als Empfindungsgehalt zugrunde liegt dem menschlichen Seelenleben, dass sich das ausdrücken lässt durch die Bewegung der menschlichen Glieder, gerade am meisten durch die Bewegung der ausdrucksvollsten menschlichen Glieder, der Arme und Hände.

Wenn man nämlich durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen - um mich dieses Goethe’schen Ausdruckes zu bedienen - richtig studiert, wie zusammenhängt das ganze System der Kehlkopf- und sonstige[n] innere[n] Bewegungsansätze mit den Luftbewegungen, und wenn man das dann mit entsprechender Metamorphose überträgt auf namentlich also die menschlichen Arme und Hände, dann bekommt man eine Möglichkeit von Gesten, zu denen sich die gewöhnlichen Gesten - mit denen wir, um uns in Bezug auf das Verständnis zu helfen, unsere Sprache begleiten -, zu denen sich diese einfacheren Gesten, ja das einfachere Mienenspiel, dessen sich der Schauspieler bedient, verhalten wie das Lallen eines Kindes zur wirklich artikulierten ausgebildeten Sprache oder zum ausgebildeten Gesange.

Also das gewöhnliche Mienenspiel, die gewöhnliche Geste wären eigentlich das Lallen und dasjenige, was man durch ein genaues Studium, sinnlich-übersinnliches Studium der Bewegungsmöglichkeiten des menschlichen Organismus herausbekommt, das ist dann das sichtbare ausgebildete Singen oder die sichtbare ausgebildete Sprache. Und alles dasjenige, was die Seele durch Gesang oder Sprache sonst ausdrücken kann, lässt sich auch ausdrücken durch diese sichtbare Sprache, durch diesen sichtbaren Gesang.

Nur muss man dabei berücksichtigen, dass gewiss auf der einen Seite übergeht dasjenige, was Eurythmie ist - obwohl man diesen Übergang nicht allzu stark bewirken soll -, übergeht in gewöhnliches Gestenspiel; gewöhnliche Mimik darf nicht mit Eurythmiegesten verwechselt werden. Auf der anderen Seite geht über dasjenige, was Eurythmie ist — das zeigt sich, je mehr der Mensch tanzartige Bewegungen ausführt, desto mehr entspricht dasjenige, was er in Formen, in Takt, in der Rhythmik der Bewegungen ausdrückt, desto mehr entspricht es dem Musikalischen. Je mehr der Mensch aber mit seelischem In-Bewegung-Setzen seines Organismus, das ausläuft in die Artikulation der Hände, in die Artikulation der Arme, je mehr er auf diese Weise Bewegungen ausführt, desto mehr werden diese Bewegungen durchaus ein sichtbar sprachlicher Ausdruck. Sodass Sie auf der einen Seite sehen werden in unserer Darstellung, wie Musikalisches begleitet wird von solchen Bewegungen. Da singt man sichtbar, während man sonst hörbar singt. Ebenso werden Sie Dichtungen rezitiert, deklamiert hören, die begleitet werden von eurythmischen Bewegungen des ganzen Menschen, von Menschengruppen und namentlich auch begleitet werden von der Bewegung der Arme und Hände.

Dieses Bewegen der Arme und Hände ist nun ein vollkommener Ausdruck für dasjenige, was Dichtung ist - wie die Lautsprache selbst. Während man aber, wenn man übergeht zu Bewegungen von Armen und Händen, im Bewegen des ganzen Menschen beim sichtbaren Gesange eigentlich mehr zum Ausdrucke bringt dasjenige, was von der Seele aus als Empfindungen das Musikalische begleitet, bringt man in der eurythmischen Sprache tatsächlich, wenn sie richtig behandelt wird, alles Bildhafte, Melodiöse, Taktmäßige, Rhythmische und auch den Inhalt des Sprachlichen zu einer wirklichen Offenbarung. Dadurch ist man imstande, dasjenige, was der Dichter wie eine, ich möchte sagen innerliche Eurythmie in sein Kunstwerk hineinlegt, das nun auch wirklich als Ausdruck des ganzen Menschen zur sichtbaren Offenbarung zu bringen. Und man bekommt dadurch die Möglichkeit, auch Dramatisch-Dichterisches in einer höheren Stilisierung auszudrücken als durch die gewöhnliche Mimik.

Das kann sich besonders anschaulich zeigen bei einer solchen Dichtung wie derjenigen, die eben heute eurythmisch vor der Pause vorgeführt wird, bei Goethes «Prolog im Himmel». Ein mächtiges, grandioses Bild von Engelgestalten, welche - die Weltenabsichten zu offenbaren - sprechen, tritt vor uns hin. Begleitet ist es von demjenigen, was Mephisto dabei zu sagen hat. Alles dasjenige aber, was sich als Erlebnisse der menschlichen Seele in ein Verhältnis stellt zum Übersinnlichen, das kann ganz besonders gut durch diese höhere Stilisierung der Eurythmie zum Ausdrucke gebracht werden. Und kennt man einmal die Eurythmie, so bekommt man unmittelbar das Bedürfnis, aus der gewöhnlichen naturalistischen Mimik herauszugehen für jene Szenen, die sich auf das Übersinnliche beziehen, und auf diese Weise auch eine vollkommenere bühnenmäßige Darstellung solcher Szenen zu bekommen, wie Goethes «Prolog im Himmel» eine darstellt.

Natürlich könnte man auch dasjenige, was Mephisto zu sagen hat, in eurythmische Darstellung bringen. Allein, insofern der Mensch sich darlebt auch als ein seelisch-geistig-übersinnliches Wesen, kommt eben dieses innere Wesen durch die eurythmische Sprachbewegung zum Ausdruck, zur Offenbarung. Und wir können dann das auch anwenden, wenn wir Engelwesen sich ausdrücken lassen wollen. Nur eben die Teufelseurythmie haben wir noch nicht erfunden, und daher muss Mephisto noch in ganz naturalistischer Mimik heute dargestellt werden. Vielleicht gelingt es einmal, auch die entsprechende «Teufelssprache» - ich meine in eurythmischer Form - zu entdecken, dann kann auch das eurythmisch dargestellt werden.

Aber wir streben wirklich danach, das ganze Bühnenhafte immer mehr und mehr nach dem Eurythmischen auszugestalten. Und da zeigt sich eines, das ganz besonders interessant ist. Wir haben ja seit längerer Zeit schon begonnen, dasjenige, was dichterisch oder musikalisch auch eurythmisch dargestellt werden soll, das auch zu unterstützen durch die entsprechenden Beleuchtungen, die wir dem Bühnenraum geben und die harmonisch zusammenklingen müssen, farbig harmonisch zusammenklingen müssen mit den Bekleidungen der einzelnen Gestalten, die eurythmisierend auftreten. Und da zeigt sich etwas Eigentümliches.

Man kann ja auch zum Beispiel, wenn man irgendwie rein Musikalisches - Instrumental-Musikalisches will ich sagen - aufführt, man kann ja unter Umständen durch Beleuchtungseffekte Parallelerscheinungen, Lichtparallelerscheinungen hervorrufen, die ungefähr auch in ihrer Aufeinanderfolge einen ähnlichen Eindruck hervorrufen wie die musikalische Form oder der musikalische Inhalt. Aber es ist etwas ganz anderes, so etwas etwa, sagen wir in der Operndarstellung zu tun und es zu tun bei unserer eurythmischen Darstellung. Bei der Operndarstellung wird man immer das Gefühl haben, dass die Beleuchtungseffekte doch eigentlich nur etwas sind wie die Begleitung des Kunstwerkes, etwas, was von außen sich zum Kunstwerke hinzugesellt, während hier die Beleuchtungseffekte streng innerlich sich mit dem Kunstwerke, nämlich mit dem eurythmischen Kunstwerke verbinden. Sodass man auch die Empfindung bekommt: Wie die Stimmung beim Singen gewissermaßen vom Menschen ausströmt, nach allen Seiten des Raumes ausströmt, und wie man diese ausströmende Stimmung gewissermaßen als Lichtwirkungen darstellen könnte, so ist die ganze Stimmung, in die das Bühnenbild durch Beleuchtungseffekte bei einer eurythmischen Aufführung gebracht werden muss, diese Stimmung ist wie etwas, das nun nicht ausstrahlt von den eurythmisierenden Gestalten, sondern das so wirkt, wie wenn die eurythmisierenden Gestalten diese Lichtkörper, diese Lichtmassen einsaugen, einatmen würden, wie wenn sie sich zu ihnen hinbewegen würden, wie wenn sie ihrer bedürfen würden.

Kurz, man wird noch allerlei Eigentümlichkeiten dieser sichtbaren Sprache, dieser Eurythmie, im Laufe der Zeit entdecken. Heute ist ja wirklich davon im Grunde nur ein Anfang vorhanden. Sie werden also auf der einen Seite begleitet finden das Eurythmische vom Musikalischen. Da ist es ein Singen, ein sichtbares Singen. Sie werden es begleitet finden von Rezitation und Deklamation. Da ist es ein Sprechen.

Nun hat es sich immer mehr und mehr gezeigt, dass eigentlich es etwas ganz Unorganisches, Unkünstlerisches ist, wenn derjenige, der die eurythmischen Bewegungen ausführt, zu gleicher Zeit die Worte sprechen will. Es zeigt sich, dass das Künstlerische eigentlich doch darinnen besteht, dass derjenige, der seine Seele in der Bewegung auslebt, für das Ohr vollständig stumm wird und dass dasjenige, was für das Ohr auftritt, abgesondert in Rezitation und Deklamation oder in Instrumentalmusik auftritt. Selbst der Sänger, wenn er begleiten sollte etwas Eurythmisches, müsste abgesondert singen, nicht selber eurythmisierend singen. Dadurch aber bekommt man in der Tat innerhalb der eurythmischen Kunst, ich möchte sagen ein erweitertes Orchester, ein Orchester, das sich zusammensetzt aus dem, was in der bloßen sichtbaren Bewegung vor sich geht, und demjenigen, was musikalisch dargestellt wird oder deklamatorisch oder rezitatorisch. Und es unterliegt dieses ganze Zusammenwirken ebenso den orchestralen Gesetzen wie ein Musikalisches. Man könnte daher ganz gut von einer Instrumentierung dabei sprechen.

Diese Dinge werden aus dem Wesen der Eurythmie eben durchaus nach und nach gefunden werden. Veranlagt sind sie schon lange. Man muss sehr darauf achten, dass wir ja die Eurythmie bis jetzt nur in ihrem Anfange haben und dass sie immer weiter und weiter erst ihre entsprechende Ausbildung erfahren wird. Schon jetzt zeigt sich aber, dass geradezu Sprachgeheimnisse sich eigentlich erst ergeben, wenn man beginnt, das Wesen der Eurythmie zu verstehen. Daher zeigt sich auch, dass das Rezitieren und Deklamieren selber wiederum von dem, was es heute in einem etwas unkünstlerischen Zeitalter ist- wo man das Prosaische eigentlich der Dichtung betont oder pointiert und im prosaischen Pointieren des Dichterischen das Wesentliche sucht —, dass dieses Deklamatorische und Rezitatorische wiederum hinübergeführt werden muss etwa da, wo es Goethe hatte, der mit seinen Schauspielern selbst seine Jambendramen nach Rhythmus, Takt - was ihm viel wichtiger war —, als [er] seine Jamben mit dem Taktstock einstudierte wie ein Kapellmeister; also weniger der prosaische Inhalt, sondern das Musikalische und Imaginative der Sprachgestaltung.

In der bildhaften Gestaltung des Lautlichen bekommt man im Rezitieren und Deklamieren tatsächlich ein Imaginatives. In dem Berücksichtigen des Melodiösen, des Taktmäßigen, Rhythmischen bekommt man ein Musikalisches in der Sprache. Dadurch allein, dass man diese Dinge in das Rezitieren und Deklamieren einführt, kann man in richtiger Weise dasjenige, was eurythmisch geboten wird, begleiten.

Das alles berücksichtigend, möchte ich wie immer auch heute die verehrten Zuhörer um Nachsicht bitten für die Vorstellung, da ja betont werden muss, dass wir mit der eurythmischen Kunst erst im Anfange ihrer Entwicklung stehen. Sie wird aber ganz gewiss immer mehr vervollkommnet werden durch uns oder andere. Heute darf aber schon gesagt werden, dass sie in einer unermesslichen Weise diesem Vervollkommnen wird unterliegen können, denn sie bedient sich des vollkommensten Instrumentes: des Menschen selber.

Und der Mensch ist ein Mikrokosmos, enthält tatsächlich alle Weltengeheimnisse, alle Weltengesetzmäßigkeiten, Beseelung, Durchgeistigung. Holt man aus ihm dasjenige hervor, was wirklich in so intimer Weise hervorgeholt werden kann, indem man den ganzen Menschen in Bewegung bringt, so sprechen sich zu gleicher Zeit Weltengeheimnisse durch den Menschen aus. Und es ist schon so, dass, wenn Goethe sagt: Wenn der Mensch an den Gipfel der Natur gestellt ist, nimmt er Ordnung, Maß, Harmonie und Bedeutung zusammen und offenbart diese, indem er sich zum Kunstwerk erhebt, — so kann man sagen: In der vollkommensten Weise wird der Mensch das, was in der Welt liegt, zum Kunstwerk erheben können, wenn er Ordnung und Maß, Harmonie und Bedeutung in seiner eigenen organischen Bewegungs- und Ausdrucksmöglichkeit sucht und dadurch gerade dasjenige offenbart, was in seiner Seele und in seinem Geiste lebt.

Das berücksichtigend darf man wirklich sagen, dass wohl heute schon empfunden werden kann, wie diese eurythmische Kunst sich dereinst, trotzdem sie heute erst im Anfange der Entwicklung steht, als eine vollberechtigte jüngere Kunst neben die berechtigten älteren Künste wird hinstellen können.