The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1923–1925

GA 277d

14 January 1923, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Eurythmy Performance

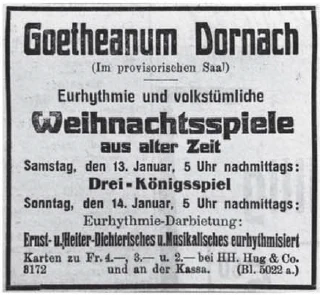

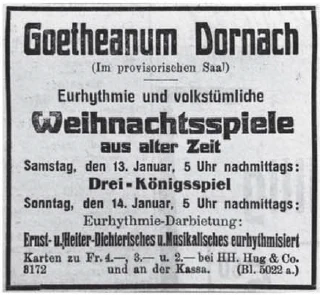

Newspaper announcement for the performance

Scene of the gray women from “Faust II,” Act 5 (midnight), with music by Jan Stuten

Ghost choir from “Faust I,” study, by J. W. v. Goethe “Funeral March” by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

“Christmas” by Vladimir Solovyov

Pastoral in G major from the Christmas Oratorio by J. S. Bach

“Epiphany” by Jose Maria de Heredia

“Repos en Egypte” by Albert Samain

Allegro in E-flat major, Op. 7, by L. van Beethoven

Humoresques by Christian Morgenstern: “Notturno in White”; ‘Rehearsal’; “The Priestess”; “The Two Bottles”; “The Finger”

Ladies and gentlemen!

Allow me, as usual before these eurythmic performances, to say a few words about the nature of the sources of eurythmic art. Eurythmy should not be confused with dance or mime. Without, of course, wishing to say anything derogatory about these related arts, it must be emphasized that eurythmy aims to be something fundamentally different. It seeks to make use of a truly visible language, which is expressed through the movements of individuals or groups of people, in the case of individuals preferably through the movement of the most expressive limbs, the arms and hands. Human soul experiences, as expressed in particular in poetry, can be revealed externally through spoken language, through singing, but now also through what we here call eurythmic language.

If we start from spoken language, we find in it an expression of the human organism, an expression of both what lives in the human being as will and what lives in the human being as imagination. It is the case that the whole human being is actually involved in what is expressed through spoken language. All unconscious or subconscious soul activity, everything that wants to come out of the human being in terms of organic activity, is essentially suppressed – except for what is revealed in the larynx and other speech organs.

If one now studies through sensory-supersensory observation — Goethe used this expression, and it may be used here in particular within the anthroposophical worldview — if one studies through sensory-supersensory observation how, in speech, I would say the expressions of the human head, the imaginative on the one hand and the volitional on the other, how this affects the human vocal organs, what comes from both sides; when one then studies how these original movements, which human beings actually make not only when speaking but also when listening, come to a standstill, how human beings calm down, so to speak, and everything that the soul wants to reveal flows into the speech organs, then transforms itself into the movements of air that convey hearing — when one studies this, then one can also transfer everything that is revealed here in the speech organs back to the whole human being. And then one obtains a real language that comes about solely through movements of the human limbs, mainly the arms and hands.

Modern physiology already recognizes the dependence of the speech nervous system on the limb system. It is known that in the average person today, the right arm and right hand are more strongly developed. Accordingly, the speech center is to be found in the left side of the head, because these forces always cross in the human organism. Thus, modern science already shows us a certain connection that can be expressed as follows: What a person initially wants to express in an indefinite way in their right arm, through mimicry, is transformed in the brain, becomes speech formation, and is then transferred to the speech system.

Now, what one uses in ordinary speech, what one even uses in the art of mimicry, is to what eurythmy aims to be as a child's babbling is to truly developed, articulated speech. For what is sought in the whole human being is that which is soul-related, and the human soul also lives in the whole human organism. And just as spiritual experiences can be heard through language, through spoken language, so too can spiritual experiences be revealed visibly through certain movements in individuals or groups of people. This is so regular that every sound corresponds to a specific form of movement, every turn of phrase. In short, everything linguistic also corresponds to a movement in the human being.

This does not mean that one must consciously think about the meaning of every movement that is performed. Art must have an immediate effect; it must be absorbed by the soul through feeling, without first receiving an intellectual explanation. This is also the case with eurythmy. What is offered eurythmically should first and foremost follow the lines of beauty, character, feeling, will, and so on. The general impression is what one must have first. Only those who, I would say, have to work out eurythmy technically must draw it out of the human organism in just the same way as speech is drawn out by nature in early childhood. In this way, eurythmy presents individual people or groups of people to the audience; the movements that occur in them are a language. It can be used to express poetry.

It is clear that when a person reveals themselves through one system, they cannot reveal themselves through another system at the same time, so that when a poem is expressed eurythmically through the movements of a person, that person cannot speak at the same time. This would be perceived as an overload of human activity. Therefore, we must see eurythmy here in such a way that poems are recited or declaimed and at the same time the poem is performed on stage in the visible language of eurythmy. This results in a special kind of, I would say, orchestral interaction between the art of recitation and declamation and eurythmy.

Similarly, one can bring something musically, and just as one can sing audibly, one can sing visibly. And it is particularly important in this area to distinguish between what eurythmy can achieve musically and what the art of dance can achieve. The art of dance leads via music into an element where the human being, in a sense, loses his soul in his limbs. In eurythmy, he retains his entire soul. The soul lives in the human being himself. Therefore, what is presented eurythmically to music is not dancing to music, but singing in movement. It is therefore actually visible singing, not dancing. Once you feel this, you will also feel the essence of eurythmy – which should be neither pantomime, mimicry nor dance – in the right way.

However, in the eurythmic representation of poetry, one will also see how recitation must be led back to its earlier, better forms through eurythmy. For in what the poet feels when he struggles linguistically to express something spiritual, there already lies a mysterious eurythmy. And therefore, recitation and declamation must also seek out this mystery of eurythmy in speech formation. Recitation and declamation must therefore, on the one hand, be musical, taking into account meter, rhythm, and even the melodious element in speech formation, and on the other hand, the pictorial-imaginative, the plastic element in sound formation. Not by emphasizing the prose content, as is customary today – we are, after all, in a somewhat inartistic age – but by focusing on what is truly artistic in a poem, the speech formation, we arrive at a true art of declamation and recitation, which we have endeavored to develop, especially in accompaniment with eurythmy, to which it is not as easy to declaim and recite as one might think, for it really involves an orchestral attunement to eurythmy.

What eurythmy can achieve in terms of a higher stylization of what appears on stage can be seen particularly when drama is performed eurythmically. Today you will see a rehearsal of a scene from Goethe's “Faust,” Part II: the scene with Sorrow and the other gray women—Poverty, Guilt, Misery—who approach Faust. You will see how Faust appears in a naturalistic manner, as is customary on stage, but how the figures who actually carry Faust's soul experiences over into the supersensible can be stylized in just the right way for the stage when they are presented recitatively and only the language of movement, the visible language of eurythmy, is allowed to take effect on stage. This is precisely what eurythmy can achieve in the dramatic field: where the human soul rises to the supersensible, this supersensible experience is given eurythmically, while everything that a person experiences with both feet firmly on the ground, as is the case with Faust, must of course be presented in a naturalistic stage style. And you will see how, on the one hand, Faust appears naturalistically on stage, and on the other hand, the four gray women appear in eurythmic stylization. Eurythmic stylization elevates a poem such as Faust to such heights that it should actually have a supersensible, ethereal effect.

Now, ladies and gentlemen, as I always do before such a performance, I would like to ask for your indulgence. Eurythmy is only in its infancy and will certainly need a great deal more before it can be considered a complete art form. But it uses human beings themselves as its instrument. And when Goethe uttered the beautiful words: “To whom nature begins to reveal her secrets, they long for her most worthy interpreter, art” — then we can also say: Those to whom nature begins to reveal the secrets of the human organism, which is a small world in itself, may feel a longing to see the secrets of the world brought forth from the human organism, from the whole human organism, as is the case with eurythmy. Therefore, we may believe that, however imperfect eurythmy still is today, it will, even if only after a long time — perhaps still through us, but more likely through others — because it has unlimited potential for development, it will be able to develop over time into a fully-fledged art alongside the older fully-fledged arts.

Zeitungsannounce für die Aufführung

Szene der grauen Weiber aus «Faust II», 5. Akt (Mitternacht), mit Musik von Jan Stuten

Geisterchor aus «Faust I», Studierzimmer, von J. W. v. Goethe «Trauermarsch» von Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy

«Weihnacht» von Wladimir Solowjow

Pastorale in G-Dur aus dem Weihnachtsoratorium von J. S. Bach

«Epiphanie» von Jose Maria de Heredia

«Repos en Egypte» von Albert Samain

Allegro Es-Dur op. 7 von L. v. Beethoven

Humoresken von Christian Morgenstern: «Notturno in Weiss»; «Probe»; «Die Priesterins; «Die beiden Flaschen»; «Die Fingur»

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich wie sonst vor diesen eurythmischen Aufführungen ein paar Worte vorausschicke über das Wesen der Quellen der eurythmischen Kunst. Eurythmie sollte ja nicht zusammengeworfen werden mit Tanzkunst oder mit mimischer Kunst. Ohne dass selbstverständlich im Geringsten etwas Abrrägliches gesagt werden soll über diese Nachbarkünste, muss doch hervorgehoben werden, dass Eurythmie etwas wesentlich anderes sein will. Sie will sich einer wirklich sichtbaren Sprache bedienen, die ausgeführt wird durch die Bewegungen des einzelnen Menschen oder von Menschengruppen, beim einzelnen Menschen vorzugsweise durch die Bewegung der ausdrucksvollsten Gliedmaßen, der Arme und der Hände. Menschliche Seelenerlebnisse, wie sie sich insbesondere in der Dichtung zum Ausdruck bringen, sie können sich ja äußerlich offenbaren durch die Lautsprache, durch den Gesang, aber nun auch durch dasjenige, was wir hier die eurythmische Sprache nennen.

Gehen wir von der Lautsprache aus, so finden wir in ihr eine Äußerung durch den menschlichen Organismus, eine Äußerung sowohl dessen, was im Menschen als Wille lebt, wie auch desjenigen, was im Menschen als Vorstellung lebt. Es ist so, dass der ganze Mensch eigentlich beteiligt ist an dem, was sich auch durch die Lautsprache äußert. Alle nicht bewusste, sondern unbewusste oder unterbewusste Seelentätigkeit, das, was an organischer Betätigung aus dem Menschen herauswill, wird dabei im Wesentlichen unterdrückt - außer dem, was im Kehlkopf und in den anderen Sprachorganen zur Offenbarung kommt.

Wenn man nun durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen - Goethe gebrauchte diesen Ausdruck, und er darf ja insbesondere hier innerhalb der anthroposophischen Weltanschauung gebraucht werden -, wenn man durch sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen studiert, wie im Sprechen zusammenfließen, ich möchte sagen die Kopfäußerungen des Menschen, das Vorstellungsgemäße auf der einen Seite und das Willensmäßige auf der anderen Seite, wie das die menschlichen Stimmorgane ergreift, was von beiden Seiten herkommt; wenn man dann studiert, wie diese ursprünglichen Bewegungen, die der Mensch eigentlich nicht bloß beim Sprechen, sondern schon beim Zuhören macht, wie die stillstehen, wie der Mensch sich gewissermaßen beruhigt und alles, was da die Seele zur Offenbarung bringen will, in den Sprachorganismus hineinfließt, sich dann umgestaltet zu den Luftbewegungen, die das Hören vermitteln - wenn man dieses studiert, so kann man auch wiederum zurückverlegen alles dasjenige, was hier in den Sprachorganen zur Offenbarung kommt, in den ganzen Menschen. Und man bekommt dann eine wirkliche Sprache, die eben nur durch Bewegungen der menschlichen Gliedmaßen, hauptsächlich der Arme und Hände, zustande kommt.

Schon die heutige Physiologie kennt ja die Abhängigkeit des Sprach-Nervensystems von dem Gliedmaßensystem. Man weiß, dass beim heutigen Durchschnittsmenschen der rechte Arm und die rechte Hand stärker ausgebildet sind. Demgemäß ist das Sprachzentrum im linken Haupte zu suchen, weil immer sich diese Kräfte im Organismus eines Menschen kreuzen. So zeigt uns schon die heutige Wissenschaft einen gewissen Zusammenhang, der sich etwa so aussprechen lässt: Dasjenige, was der Mensch zunächst in einer unbestimmten Weise in seinem rechten Arm zum Ausdruck bringen will, mimisch, das wandelt sich um im Gehirn, wird zur Sprachgestaltung und überträgt sich dann auf das Sprachsystem.

Nun, dasjenige, was man im gewöhnlichen Sprechen mimisch anwendet, was man sogar in der mimischen Kunst anwendet, das verhält sich aber zu dem, was Eurythmie sein will, wie das Lallen eines Kindes zu der wirklich ausgebildeten artikulierten Sprache. Denn es wird gesucht in dem ganzen Menschen das, was Seelisches ist, und im ganzen menschlichen Organismus lebt ja auch die menschliche Seele. Und so, wie hörbar die seelischen Erlebnisse herauskommen können durch die Sprache, durch die Lautsprache, so können sichtbar durch gewisse Bewegungen an Menschen oder Menschengruppen die seelischen Erlebnisse zur Offenbarung kommen. Das ist dann so regelmäßig, dass jedem Laute eine bestimmte Bewegungsform entspricht, jeder Satzwendung. Kurz: Allem Sprachlichen entspricht auch eine Bewegung am Menschen.

Es ist nicht etwa damit die Meinung begründet, als ob man nun ganz bewusst bei jeder Bewegung, die da vorgeführt wird, auch nachdenken müsste: Was bedeutet sie? Das Künstlerische muss ja im unmittelbaren Eindrucke wirken, muss, ohne erst eine verstandesmäßige Erklärung zu bekommen, von der Seele empfindungsgemäß aufgenommen werden. So ist es auch bei der Eurythmie. Was eurythmisch geboten wird, soll zunächst in den Linien der Schönheit, des Charakteristischen, des Gefühlsmäßigen, des Willensmäßigen und so weiter verlaufen. Der allgemeine Eindruck ist das, was man zunächst haben muss. Nur wer, ich möchte sagen technisch die Eurythmie auszuarbeiten hat, der muss sie aus dem menschlichen Organismus gerade so gesetzmäßig herausholen, wie durch die Natur im frühen Kindesalter die Lautsprache gesetzmäßig herausgeholt wird. So stellt die Eurythmie den einzelnen Menschen oder Menschengruppen vor den Menschen hin; die Bewegungen, die an ihnen auftreten, sind eine Sprache. Man kann damit Dichtungen zum Ausdruck bringen.

Es ist ja klar, dass, wenn sich der Mensch durch ein System offenbart, er sich nicht gleichzeitig durch ein anderes System offenbaren kann, dass, wenn man also ein Gedicht eurythmisch durch die Bewegungen des Menschen zum Ausdrucke bringt, der Mensch dazu nicht zugleich sprechen kann. Das würde man als eine Überladung der menschlichen Tätigkeit empfinden müssen. Daher müssen wir die Eurythmic hier so auftreten sehen, dass Dichtungen rezitiert oder deklamiert werden und gleichzeitig auf der Bühne in der sichtbaren Sprache der Eurythmie die Dichtung vorgeführt wird. Dabei bekommt man eine besondere Art, ich möchte sagen orchestralen Zusammenwirkens der Rezitations- und Deklamationskunst und der Eurythmie.

Ebenso kann man musikalisch irgendetwas bringen, und geradeso, wie man hörbar singen kann, kann man sichtbar singen. Und das ist ganz besonders wichtig, dass man auf diesem Gebiete unterscheidet, was die Eurythmie zum Musikalischen leisten kann und was die Tanzkunst leisten kann. Die Tanzkunst führt über das Musikalische in ein Element, wo der Mensch gewissermaßen sein Seelisches in seinen Gliedern verliert. Im Eurythmischen behält er dieses ganze Seelische. Die Seele lebt im Menschen selber. Daher ist das, was eurythmisch zum Musikalischen vorgeführt wird, nicht ein Tanzen zum Musikalischen, sondern ein Singen in der Bewegung. Es ist also eigentlich ein sichtbarer Gesang, nicht ein Tanz. Wenn man das einmal empfindet, so wird man auch das Wesen des Eurythmischen - das weder pantomimisch, mimisch noch tanzartig sein soll - in der richtigen Weise empfinden.

Man wird aber auch in der eurythmischen Darstellung der Dichtung sehen, wie die Rezitation geradezu an der Eurythmie wiederum zurückgeführt werden muss zu ihren früheren, besseren Formen. Denn in dem, was der Dichter empfindet, wenn er sprachlich ringt, ein Seelisches zum Ausdrucke zu bringen, liegt schon eine geheimnisvolle Eurythmie. Und daher muss die Rezitation und Deklamation auch dieses Geheimnis vom Eurythmischen in der Sprachgestaltung heraussuchen. Es muss daher die Rezitation und Deklamation auf der einen Seite musikalisch auftreten, Takt, Rhythmus, sogar das melodiöse Element in der Sprachgestaltung berücksichtigen, auf der andern Seite mehr das Bildhaft-Imaginative, das plastische Element in der Lautgestaltung. Nicht indem man, wie man heute gewöhnt ist, den Prosagehalt pointiert - wir sind ja in einem etwas unkünstlerischen Zeitalter -, sondern indem man auf das geht, was wirklich das Künstlerische an einem Gedichte ist, die Sprachgestaltung, bekommt man eine wirkliche Deklamations- und Rezitationskunst heraus, die wir uns bemüht haben auszugestalten gerade in Begleitung der Eurythmie, zu der nicht so leicht zu deklamieren und rezitieren ist, wie man eigentlich meint, denn es handelt sich wirklich um ein orchestrales Einstimmen auf die Eurythmie.

Was Eurythmie dadurch leisten kann in Bezug auf eine höhere Stilisierung dessen, was bühnenmäßig auftritt, das bemerkt man insbesondere dann, wenn man Dramatisches eurythmisch gibt. Sie werden heute eine Probe sehen in einer Szene von Goethes «Faust», zweiter Teil: die Szene mit der Sorge und den anderen grauen Weibern - Mangel, Schuld, Not -, die an Faust herantreten. Sie werden sehen, wie Faust allerdings in gewöhnlicher bühnenmäßiger Weise naturalistisch auftritt, wie aber die Gestalten, die eigentlich die faustischen Seelenerlebnisse ins Übersinnliche hinüberführen, gerade in der richtigen Weise bühnenmäßig stilisiert werden können, wenn man sie rezitatorisch vorbringt und auf der Bühne nur die Bewegungssprache, die sichtbare Sprache der Eurythmie wirken lässt. Gerade das kann die Eurythmie im dramatischen Felde leisten, dass da, wo die menschliche Seele sich zum Übersinnlichen erhebt, dieses übersinnliche Erlebnis eben eurythmisch gegeben wird, während alles, was der Mensch so erlebt, dass er gewissermaßen fest mit seinen zwei Beinen auf der Erde ist, wie es bei Faust ist, natürlich im naturalistischen Bühnenstil vorgeführt werden muss. Und Sie werden sehen, wie auf der einen Seite Faust naturalistisch bühnenmäßig auftritt, und auf der anderen Seite die vier grauen Weiber in eurythmischer Stilisierung. Die eurythmische Stilisierung hebt besonders eine Dichtung wie die «Faust»-Dichtung in eine solche Höhe hinauf, wo sie eigentlich berührt vom Übersinnlich-Ätherischen wirken sollte.

Nun, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, auch heute möchte ich, wie ich es immer tue vor einer solchen Aufführung, um Nachsicht bitten. Eurythmie ist erst im Anfange ihres Werdens und wird ganz gewiss noch vieles brauchen, bis sie einigermaßen als eine vollkommenere Kunst wird auftreten können. Allein, sie bedient sich ja des Menschen selber als ihres Instrumentes. Und wenn Goethe das wunderschöne Wort ausgesprochen hat: Wem die Natur ihre Geheimnisse zu enthüllen beginnt, der sehnt sich nach ihrer würdigsten Interpretin, der Kunst - dann wird man auch sagen können: Wem die Natur beginnt, die Geheimnisse des menschlichen Organismus, die eine kleine Welt für sich sind, zu enthüllen, der kann eine Sehnsucht empfinden, die Weltengeheimnisse gerade aus dem menschlichen Organismus, aus dem ganzen menschlichen Organismus hervorgeholt zu sehen, wie das bei der Eurythmie der Fall ist. Deshalb darf man glauben: So unvollkommen die Eurythmie heute noch ist, so wird sie sich, wenn auch nach längerer Zeit erst - vielleicht noch durch uns, wahrscheinlicher aber durch andere -, weil in ihr unbegrenzte Entwicklungsmöglichkeiten liegen, so wird sie sich im Laufe der Zeit zu einer vollberechtigten Kunst neben den älteren vollberechtigten Künsten entwickeln können.