The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1923–1925

GA 277d

4 February 1923, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

“The Goetheanum in its Ten Years IV” (from: “Das Goetheanum,” February 4, 1923)

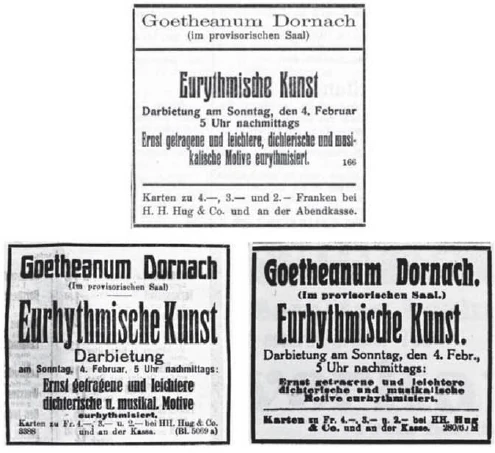

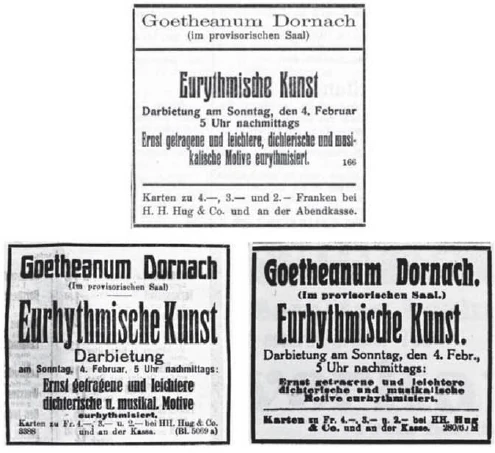

Draft announcement and newspaper advertisement for the performance

“Rêve” by Victor Hugo with music by Jan Stuten

“Christmas” by Vladimir Solovyov

Sarabande in B flat major by G. F. Handel

“The Nile Delta” by Vladimir Solovyov

“Prélude op. 28,15 (Raindrops)” by Frédéric Chopin

“Auf leichten Füßen” (On Light Feet) by Christian Morgenstern

Nocturne in E flat major, op. 9 by Frédéric Chopin

“Das Verhängnis” (The Doom) by Fercher von Steinwand

“Der Gnade Wesen” (The Nature of Grace) from “The Merchant of Venice” by William Shakespeare

“Feuerrotes Fohlen” (Fire-Red Foal) by Albert Steffen

“Waldszenen, Eintritt” (Forest Scenes, Entrance), Op. 82 by Robert Schumann

“Die Libelle” (The Dragonfly) by J. W. v. Goethe

“Sehnsucht” by Dschung Tsü with music by Jan Stuten

“Deine Tänze” by Albert Steffen

“Caprice” by Max Reger

Ladies and gentlemen!

Allow me to introduce today's performance with a few words. What we refer to as eurythmy should not be confused with related arts such as mime, dance, or the like. Without, of course, objecting to these arts in any way, it must nevertheless be emphasized that eurythmy is [something] fundamentally different.

Eurythmy is intended to be human speech brought before the eye. In order to develop this language—and what you will see in the performance is by no means a series of arbitrary gestures, but rather a trained, visible language—one must first become acquainted with the whole spirit of the speech organism. When we as human beings speak or sing, the whole human being is actually involved in an inner soul movement; and that which lives in the whole human being comes to expression in the isolated, separate organs of the larynx and what belongs to it.

The fact is that with every sound, with every tone, the human being gives of himself, and that this is based on intentions of movement which are actually held back by being converted by the larynx and its neighboring organs into movements of air, which then convey the tone or sound to the ear. So that one must first seek out what lies deeper within the human being if one wants to penetrate the full secrets of speaking and singing. What lies deeper within the human being is expressed in eurythmy through the movement of the individual limbs of the individual human being—namely, the most expressive limbs, the arms and hands—or also through the movements of groups of people.

You will see, dear audience, that not only such eurythmic things — namely eurythmic forms — are expressed in parallel with recitation or declamation, but also in parallel with music. We are now accustomed to understanding that which parallels music in the art of human movement as dance. Here, however, it is not meant as dance, but as visible singing, so that the whole human being appears before us in motion, while at the same time the musical motifs are heard, so that the whole human being sings in his movements — not dances, but sings — in a visible way to the music, just as he otherwise sings in an audible way through [the] larynx and so on.

This can then be directly applied to the eurythmic accompaniment of the vocal, linguistic element, i.e., the poetic, which basically already consists of a kind of inner eurythmy, a kind of invisible eurythmy. For the real poet, it is not simply a matter of communicating some inner content in a language of arbitrary design. Rather, it is important that poetic language formation be sought out of the possibilities of language itself, so that what is actually poetic in a poem is that which proceeds in the manner of music or in the manner of the imaginative.

The imaginative shaping of sound, the imaginative shaping of entire sentences, or even meter, rhythm, the melodious element: that is what is truly artistic. And it lives much more in the sense of poetic art, let's say, to express something that is to be expressed as passion in a poem through a fast rhythm than through the prosaic content of the words. Or let's say, not expressing superiority by describing it prosaically, but expressing it by letting things unfold in a slow rhythm of language.

Those who have an imaginative way of seeing things instinctively translate correct declamation and recitation into images anyway. For the true poet has this inner spiritual movement of the whole human being in mind when he composes his poetry. He does not have the prosaic content of the poem in mind. Therefore, the recitation that accompanies eurythmy must be completely different from the way recitation and declamation are often performed today in an unartistic age – in which we live. It is therefore very difficult to get used to the way recitation is done here in eurythmy, because it is a matter of reciting or declaiming according to the speech formation, not according to the prosodic accent.

Otherwise, it would not be possible to accompany the way in which the whole person approaches you here on stage in their movements with recitation. For this recitation and declamation to eurythmy consists in the fact that, certainly, the individual gesture expresses something, but that what matters above all is the sequence of gestures, what I would call the angular, the round, the angular-round, and so on, of the gesture. It is not important that one performs this gesture here, but that one allows it to work as a whole. For art should not be interpreted intellectually – that kills it – but should work in the immediate sensory impression. And that is precisely what eurythmy can do.

In eurythmy, it is also important to be clear that we are not dealing with arbitrary gestures of the moment, just as in the language of sound, in spoken language, we are not dealing with arbitrary sounds that we utter to express the content of our soul, but with something that emerges from the human organism. Just as humans instinctively and unconsciously move their vocal cords and other speech organs in a way that cannot be seen because it is transformed into sound, so too, according to the same inner laws of the organism, after having learned the whole essence of speaking and singing through supersensible perception, one brings the whole human being, so to speak, into those movements that truly express the same thing that spoken language or singing otherwise expresses. What people otherwise add to their verbal expression in the form of facial expressions is to eurythmy what a child's babbling is to the developed language of human beings. In eurythmy, one should not imagine that one can make this or that movement on the spur of the moment. One can do this just as little as one can express oneself linguistically on the spur of the moment if one has not learned the language. For every detail and the whole of eurythmy is drawn out of the whole of the human organism. Therefore, just as a person must adhere to the laws of language when they want to express the content of a civilized language – they do this instinctively – so too must those who perform eurythmy on stage they must adhere to very specific movements, which they do not perceive as being constrained by a movement pattern, but rather as individual movements that must be shaped in a very specific way. [Just] as when one speaks aloud, an “a” must be an “a” and cannot even be pronounced as an “ä” or an ‘ü’ instead of an “a.” So eurythmy is a truly visible language. It is based on the same inner laws of the human organism as spoken language itself, except that spoken language is acquired instinctively by humans. But eurythmy is acquired by humans just as naturally, albeit in a conscious way. If one therefore thinks that what is presented here as movements of individual humans or groups of humans is based on some kind of arbitrariness, then one has not yet arrived at an understanding of what eurythmy actually aims to achieve. The whole human being can reveal itself in its soul content in many different ways, and one of these revelations is precisely the language of eurythmy.

Now we know – and I must emphasize this today, as I always do at the beginning of such presentations – we know that we must ask our esteemed audience for their indulgence, because eurythmic art is only in its infancy today and still needs a great deal of refinement. But at the same time, anyone who has brought out piece by piece from the inner laws of human nature for this eurythmic art knows that it truly has immeasurable potential for perfection, which must come one day. Such a thing can only be worked out piece by piece.

Recently, for example, we have added a kind of eurythmic lighting art to the movement of people that can be seen on stage. So that the stage design not only has moving people and moving groups of people, but also, in harmony with this, a sequence of lighting effects, a kind of eurythmy through lighting. And you may notice something right away. Whereas in a conventional stage design, when something dramatic or mimetic is being portrayed on stage, the lighting is chosen in such a way that it is, so to speak, pointedly adapted to the situation at that moment – let's say, if a scene is being played out in the morning, morning lighting and the like is used – here, the lighting is not naturalistic, but rather the lighting sequences must be coordinated like the notes in a musical melody. It depends on the sequence of lighting effects. And this sequence of lighting effects must in turn be coordinated with what we see as movements.

This makes one aware that in eurythmic language, one avoids what must otherwise be present in poetry: the intellectual. Thought, in its dryness and abstractness, kills what is truly artistic, especially in civilized languages. In our language, an element of will and an element of thought flow together. The element of will is expressed primarily in eurythmic art. And again, it must be said that while in the art of dance, which also shows people in motion, people essentially lose themselves in the movements, in eurythmic movement people retain their full consciousness. There is also nothing dreamlike in eurythmic movement. But then again, there is nothing that could be interpreted in any abstract way; rather, one must feel the roundness or angularity, all the other peculiarities that can be expressed through the means of human movement.

In all this, however, eurythmy is only a beginning today. However, anyone who considers what instrument eurythmy actually needs must recognize its immeasurable potential for development: it needs the human being itself, not external instruments. And it does not need the human being in the imperfection in which the art of mime uses it as a moving human being, but uses it in such a way that every movement is drawn from the depths of the organic human being. Since the human being is truly a small world, a microcosm, containing all the laws and secrets of the universe, they must also reveal themselves as an instrument that can truly reveal the secrets of the world through the secrets of the human soul. In the eurythmically moving human being, one already has something like the language of the cosmos, but one that works through the human soul in the movement of the human limbs. Therefore, because eurythmy strives to develop the human being itself more and more as an artistic element in living movement, we can believe that it will one day be able to reveal itself to the world as an art form just as legitimate as its older sister arts have been for a long time.

«Das Goetheanum in seinen zehn Jahren IV.» (aus: «Das Goetheanum», 4. Februar 1923)

Ankündigungsentwurf und Zeitungsannonce für die Aufführung

«Rêve» von Victor Hugo mit Musik von Jan Stuten

«Weihnacht» von Wladimir Solowjow

Sarabande in B-Dur von G. F. Händel

«Das Nildelta» von Wladimir Solowjow

«Prélude op. 28,15 (Regentropfen)» von Frédéric Chopin

«Auf leichten Füßen» von Christian Morgenstern

Nocturne Es-Dur, op. 9 von Frédéric Chopin

«Das Verhängnis» von Fercher von Steinwand

«Der Gnade Wesen» aus «Der Kaufmann von Venedig» von William Shakespeare

«Feuerrotes Fohlen» von Albert Steffen

«Waldszenen, Eintritt, op. 82» von Robert Schumann

«Die Libelle» von J. W. v. Goethe

«Sehnsucht» von Dschung Tsü mit Musik von Jan Stuten

«Deine Tänze» Albert Steffen

«Caprice» von Max Reger

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie mir, unsere heutige Aufführung mit einigen Worten einzuleiten. Dasjenige, was wir als Eurythmie bezeichnen, soll nicht verwechselt werden mit Nachbarkünsten wie mimischer oder Tanzkunst oder dergleichen. Ohne dass selbstverständlich gegen diese Künste hier irgendetwas eingewendet wird, muss aber doch betont werden, dass es sich bei der Eurythmie um [etwas] wesentlich anderes handelt.

Eurythmie soll ja sein eine vor das Auge gebrachte menschliche Sprache. Man muss, um diese Sprache auszubilden - und es ist in demjenigen, was Ihnen vorgeführt wird, durchaus nicht eine Summe von Willkürgebärden zu suchen, sondern eben eine ausgebildete, sichtbare Sprache -, man muss, um diese Sprache auszubilden, zunächst den ganzen Geist des Sprachorganismus kennenlernen. Wenn wir als Menschen sprechen oder auch singen, so ist eigentlich in einer inneren seelischen Beweglichkeit der ganze Mensch; und dasjenige, was im ganzen Menschen lebt, kommt in den isolierten, abgesonderten Organen des Kehlkopfes und was zu ihm gehört zur Offenbarung.

Die Sache ist so, dass eigentlich bei jedem Laut, bei jedem Ton, der Mensch sich selbst gibt und dass Bewegungsabsichten zugrunde liegen, die eigentlich aufgehalten werden, indem sie umgesetzt werden durch den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane in die Luftbewegungen, die dann für das Ohr den Ton oder den Laut vermitteln. Sodass man dasjenige, was mehr zurückliegt im Menschen, erst aufsuchen muss, wenn man in die vollen Geheimnisse des Sprechens und Singens eindringen will. Das nun, was weiter zurückliegt im Menschen, das wird ausgedrückt in der Eurythmie durch die Bewegung der einzelnen Glieder des einzelnen Menschen - namentlich der ausdrucksvollsten Glieder, der Arme und Hände - oder auch durch die Bewegungen von Menschengruppen.

Sie werden sehen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, dass nicht nur solche eurythmischen Dinge - namentlich eurythmische Formen — ausgedrückt werden parallelgehend mit der Rezitation oder Deklamation, sondern auch parallelgehend mit Musikalischem. Man ist nun gewöhnt, dasjenige, was in menschlicher Bewegungskunst dem Musikalischen parallel geht, als Tanz. aufzufassen. Hier aber ist es nicht als Tanz gemeint, sondern hier ist es als sichtbarer Gesang gemeint, sodass der ganze Mensch bewegt vor uns auftritt, indem zu gleicher Zeit die musikalischen Motive ertönen, sodass der ganze Mensch in seinen Bewegungen so singt - nicht tanzt, sondern singt - in sichtbarer Weise zum Musikalischen, wie er sonst in hörbarer Weise durch [den] Kehlkopf und so weiter singt.

Das kann dann unmittelbar angewendet werden auf die eurythmische Begleitung des lautlichen, sprachlichen Elements, also des Dichterischen, das ja besteht im Grunde genommen schon in einer Art innerer Eurythmie, in einer Art unsichtbarer Eurythmie. Bei dem wirklichen Dichter kommt es nämlich nicht bloß darauf an, irgendwelche Seeleninhalte nur mitzuteilen in einer beliebig gestalteten Sprache. Sondern es kommt darauf an, dass aus den Sprachmöglichkeiten selbst heraus die dichterische Sprachgestaltung gesucht wird, sodass eigentlich dichterisch an einem Gedichte das ist, was in der Art des Musikalischen oder in der Art des Imaginativen verläuft.

Die imaginative Gestaltung des Lautes, die imaginative Gestaltung ganzer Sätze zu bringen eben oder auch Takt, Rhythmus, das melodiöse Element: Das ist das eigentlich Künstlerische. Und viel mehr lebt es im Sinne der dichterischen Kunst, sagen wir, durch einen schnellen Rhythmus irgendetwas, was als Leidenschaft im Gedichte zum Ausdruck kommen soll, auszudrücken, als durch den Prosagehalt der Worte. Oder sagen wir, eine Überlegenheit nicht auszudrücken dadurch, dass man prosaisch schildert die Überlegenheit, sondern sie dadurch zum Ausdruck zu bringen, dass man in einem langsamen Rhythmus Sprachgestaltung die Sache verlaufen lässt.

Wer imaginatives Anschauen hat, dem übersetzt sich ohnedies schon instinktiv eine richtige Deklamation und Rezitation ins Bild. Denn der wirkliche Dichter hat diese innere seelische Bewegung des ganzen Menschen in seinem Sinn, wenn er seine Dichtung gestaltet. Er hat nicht im Sinne den Prosagchalt des Gedichtes. Daher muss die Rezitation, die die Eurythmie begleitet, durchaus anders sein, als heute oftmals in einem unkünstlerischen Zeitalter - in dem wir ja leben - Rezitation und Deklamation gestaltet wird. Man gewöhnt sich daher sogar sehr schwer an die Art und Weise, wie hier zu der Eurythmie rezitiert wird, weil es sich darum handelt, nach der Sprachgestaltung, nicht nach der Pointierung des Prosagchaltes zu rezitieren oder zu deklamieren.

Anders würde man die Art, wie der ganze Mensch Ihnen hier auf der Bühne in seinen Bewegungen entgegenrritt, eben nicht durch die Rezitation begleiten können. Denn diese Rezitation und Deklamation zur Eurythmie besteht darinnen, dass nun ja gewiss die einzelne Gebärde etwas ausdrückt, aber dass es vorzugsweise ankommt auf die Aufeinanderfolgen der Gebärden, auf dasjenige, was ich nennen möchte das Eckige, das Runde, das Eckig-Runde und so weiter der Gebärde. Es kommt nicht darauf an, dass man diese Gebärde hier betätigt, sondern dass man sie als ein Ganzes wirken lässt. Denn die Kunst soll nicht gedanklich ausgedeutet werden - das tötet sie -, sondern sie soll im unmittelbaren sinnlichen Eindrucke wirken. Und das kann eben die Eurythmie.

Es handelt sich bei der Eurythmie ferner darum, dass man sich klar ist, dass man es nicht mit augenblicklichen Willkürgebärden zu tun hat, geradeso, wie man es in der Tonsprache, in der Lautsprache nicht zu tun hat mit beliebigen Lauten, die man hervorstößt für einen Seeleninhalt, sondern mit etwas, das aus der menschlichen Organisation gestaltet hervorkommt. Geradeso, wie instinktiv, unbewusst der Mensch seine Stimmbänder, seine übrigen Sprachorgane in eine Bewegung bringt, die ja nicht gesehen wird, weil sie sich umsetzt in das Tonliche, in das Lautliche, so bringt man nun nach denselben inneren Gesetzen des Organismus, nachdem man durch sinnlichübersinnliches Schauen das ganze Wesen des Sprechens und Singens kennengelernt hat, bringt man den ganzen Menschen gewissermaRen in diejenigen Bewegungen, welche wirklich ausdrücken dasselbe, was sonst Lautsprache oder der Gesang ausdrückt. Dasjenige, was der Mensch sonst als Mimik hinzufügt zu seinem Wortausdrucke, das verhält sich zur Eurythmie wie das Lallen eines Kindes zu der ausgebildeten Sprache des Menschen. Man sollte sich in der Eurythmie eben nicht gleich vorstellen, dass man aus dem Augenblick heraus diese oder jene Bewegungen machen kann. Man kann sie ebenso wenig machen, als man aus dem Augenblicke heraus, wenn man die Sprache nicht gelernt hat, sich sprachlich ausdrücken kann. Denn es ist schon aus dem Ganzen des menschlichen Organismus hervorgeholt jede Einzelheit und das Ganze der Eurythmie. Daher muss so wie der Mensch, wenn er den Inhalt einer Zivilisationssprache geben will, sich eben an die Gesetze der Sprache halten muss - er tut das instinktiv -, so muss sich derjenige, der hier auf der Bühne eurythmisch darstellt, er muss sich halten an ganz bestimmte Bewegungen, die er aber nicht so empfindet, als ob er in ein Bewegungsschema eingespannt wäre, sondern die er so empfindet, als ob eben die einzelne Bewegung in ganz bestimmter Weise gestaltet sein muss. [So] wie wenn man lautlich spricht, ein a eben ein a sein muss und nicht einmal ein ä oder ein “ hervorgestoRen werden kann statt eines a. Also die Eurythmie ist eine wirklich sichtbare Sprache. Sie beruht auf derselben inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit des menschlichen Organismus wie die Lautsprache selbst, nur dass die Lautsprache instinktiv vom Menschen angeeignet ist. Aber nicht weniger natürlich wird diese Eurythmie vom Menschen - wenn auch in bewusster Art - angeeignet. Wenn man daher meint, dass das, was hier als Bewegungen des einzelnen Menschen oder von Menschengruppen dargestellt wird, auf irgendwelcher Willkür beruht, so ist man eben noch nicht bei dem Verständnis desjenigen, was eigentlich Eurythmie will, angelangt. Es kann sich eben der ganze Mensch seinem seelischen Gehalte nach auf die verschiedenste Art offenbaren, und eine dieser Offenbarungen ist eben die eurythmische Sprache.

Nun wissen wir - und ich muss das auch heute betonen, wie ich das immer im Beginne solcher Vorstellungen tue -, wir wissen, dass wir die verehrten Zuschauer um Nachsicht zu bitten haben, weil eurythmische Kunst heute erst im Anfange ihres Werdens ist und noch gar sehr der Vervollkommnung bedarf. Aber zu gleicher Zeit weiß derjenige, der Stück für Stück hervorgeholt hat aus der inneren Gesetzmäßigkeit der Menschennatur für diese eurythmische Kunst, dass in ihr wahrhaftig unermessliche Vervollkommnungsmöglichkeit liegt, die einmal kommen muss. Man kann ja solch eine Sache nur stückweise sich erarbeiten.

In der letzten Zeit zum Beispiel haben wir hinzugefügt zu der Bewegung des Menschen, die auf der Bühne zu sehen ist, eine Art eurythmische Beleuchtungskunst. Sodass das Bühnenbild nicht nur den bewegten Menschen und die bewegten Menschengruppen hat, sondern im Zusammenklang damit die Aufeinanderfolge der Beleuchtungswirkungen, eine Art Eurythmie durch die Beleuchtung. Und dabei kann Ihnen gleich etwas auffallen. Während man beim gewöhnlichen Bühnenbild auf der Szene wenn Dramatisches, Mimisches dargestellt wird, die Beleuchtung so wählt, dass sie gewissermaßen sich pointiert anpasst an dasjenige, was nun gerade im Augenblicke die Situation ist - sagen wir nun, wenn eben irgendeine Szene am Morgen gespielt wird, nimmt man Morgenbeleuchtung und dergleichen -, handelt es sich hier darum, dass nichts Naturalistisches auch in der Beleuchtung liegt, sondern dass auch die Beleuchtungsaufeinanderfolgen so gestimmt sein müssen wie etwa die Töne in einer musikalischen Melodie. Es kommt auf das Aufeinanderfolgen der Beleuchtungswirkungen an. Und diese Aufeinanderfolge der Beleuchtungswirkung muss wiederum zusammenstimmen mit demjenigen, was man als Bewegungen sieht.

Dadurch wird man gewahr, dass man gerade in der eurythmischen Sprache vermeidet dasjenige, was sonst in der Dichtung noch drinnen sein muss: das Gedankliche. Der Gedanke in seiner Trockenheit und Abstraktheit ertötet ja insbesondere in den zivilisierten Sprachen das eigentlich Künstlerische. In unserer Sprache fließen zusammen ein Willenselement und ein Gedankenelement. Das Willenselement kommt vorzugsweise zum Ausdrucke in der eurythmischen Kunst. Und wiederum muss man sagen: Während bei der Tanzkunst, die ja auch den Menschen in Bewegung zeigt, im Grunde genommen der Mensch sich in die Bewegungen hineinverliert, erhält sich der Mensch mit seinem vollen Bewusstsein in der eurythmischen Bewegung. Es ist auch nichts Traumhaftes in der eurythmischen Bewegung. Aber es ist auch wiederum nichts, was irgendwie abstrakt ausgedeutet werden könnte, sondern man muss empfinden die Rundung oder die Eckigkeit, alle anderen Eigentümlichkeiten, die durch das Mittel der Bewegung des Menschen zum Ausdrucke kommen können.

Bei alledem ist aber heute Eurythmie nur ein Anfang. Eine unermessliche Entwicklungsmöglichkeit muss aber derjenige in ihr erkennen, der bedenkt, welches Instrument eigentlich diese Eurythmie braucht: Sie braucht den Menschen selber, nicht äußere Instrumente. Und sie braucht den Menschen nicht in jener Unvollkommenheit, in der ihn die mimische Kunst gebraucht als bewegten Menschen, sondern sie gebraucht ihn so, dass jede Bewegung aus den Tiefen des organischen Menschenwesens herausgeholt ist. Indem nun der Mensch wirklich eine kleine Welt, ein Mikrokosmos ist, alle Gesetzmäßigkeiten und Geheimnisse des Weltenalls in sich birgt, muss er sich auch als ein Instrument zeigen, das wirklich durch die menschlichen Seelengeheimnisse offenbaren kann die Weltengeheimnisse. Man hat schon etwas vor sich in dem eurythmisch bewegten Menschen wie die Sprache des Kosmos, die aber durch die menschliche Seele in der Bewegung der menschlichen Glieder wirkt. Deshalb darf man glauben, weil die Eurythmie danach strebt, den Menschen selber als ein künstlerisches Element in lebendiger Bewegung immer mehr und mehr auszubilden, dass sie sich einmal als eine ebenso berechtigte Kunst wird für die Welt ergeben können, wie die älteren berechtigten Schwesterkünste es seit längerer Zeit sind.