The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1923–1925

GA 277d

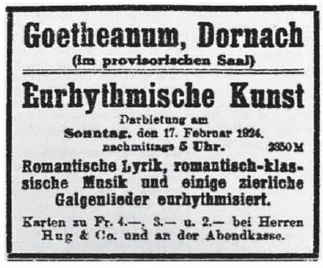

17 February 1924, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Eurythmy Performance

>Ballade in A flat major, Op. 47,3 by Frédéric Chopin

“Schön-Rohtraut” by Eduard Mörike

“Intermezzo in A-flat major” by Johannes Brahms

“At Midnight” by Eduard Mörike

“Forest Murmurs” by Franz Liszt

“From the Seven Nixen Chorus” by Eduard Mörike

Romance in F major, Op. 118,5 by Johannes Brahms

“An den Mistral” by Friedrich Nietzsche

Etude in E major by Frédéric Chopin

“Christine” by Charles Leconte de Lisle

‘Warum’ by Robert Schumann

“An den Mistral” by Friedrich Nietzsche

Prelude in B major by Frédéric Chopin

“Die Tafeln” by Christian Morgenstern

Gavotte by Giovanni Mossi

“Der Bahnvorstand” by Christian Morgenstern

Gavotte in D major by J. S. Bach

Ladies and gentlemen! I would like to say a few words before explaining the eurythmy performance. Explaining art is inartistic, and eurythmy should above all be a true art form. You are about to see an art form, ladies and gentlemen, which seeks to make an impact through artistic means that are still unfamiliar today, through an artistic language of form that is also still unfamiliar, and let me say a few words about these artistic means and this artistic language of form to help you understand.

You will see and hear three things: moving individuals and groups of people on stage, recitation and declamation on the one hand, and instrumental music on the other. Whatever can be expressed in words or musical tones should always be expressed through moving people—either individuals moving within themselves, in their limbs, or groups of people performing movements in space. At first glance, this looks as if the intention is to create an art form that is a mixture of mime and dance. Without wishing to detract in any way from these related art forms – which should of course be fully recognized – eurythmy does not seek to be either of these things: neither dance on the one hand, nor mime on the other, but rather a truly visible language.

In the same way that what is revealed in spoken language, in which the inner life of the human soul is revealed through the organs in a physical way, through the movement of air and, in a sense, with the help of an air gesture, produces the audible – in exactly the same way as the soul flows into this air gesture that appears in spoken language, so too should the soul and spirit that live in human beings flow into their movements in a completely natural way, namely into the most expressive movements, those of the arms and hands. And just as a certain sound and a very specific sequence of sounds in language corresponds to a spiritual content, so too in eurythmy a very specific movement of a human limb or a system of human limbs corresponds in a lawful manner to a spiritual content. Just as one cannot replace an o with an a in a word, one cannot, in eurythmy, replace a stretching movement of one arm with a half circle or a half circular movement with one or both arms. It is entirely possible that human beings express themselves through the movement of their limbs in the same way that they express themselves through spoken language. Indeed, there is a certain connection in the natural organization of the human being between the movement possibilities of the limbs of the organism and spoken language.

Today's knowledge actually knows very little about this, but one thing is decisive: Right-handed people have the language center of their brain on the left side. And because we can see that the few left-handed people we encounter have the language center on the right side of their brain, we can assume — and all the facts that have been carefully examined and oriented toward this insight confirm this — one can certainly assume that in the small child, that which wants to reveal itself from the soul wants to pour out into the arm and hand just as it pours out on the other side into the inner weaving and life that then emanates from the language center of the brain as stimulation to produce the sounds and sound connections of language.

Those who continue to investigate these connections in the anthroposophical manner cultivated here at the Goetheanum will find not only analogies but also completely lawful connections between all the possibilities of movement of the human organism and what is expressed in spoken language. So that one can truly say: a connoisseur of these relationships can actually guess, say, from the way someone walks—whether they walk more on their heels or more on the balls of their feet, whether they bend their knees more or less, and so on—the connoisseur can guess what particular stylization the person in question has in their speech. For it is not only the arm and the hand that express themselves in the actual organs of thought underlying language, but the whole person. For example, in the intonation of speech: whether one uses high or low tones is expressed in the movements of the feet and legs. In turn, the entire articulation of the face is expressed in the internal structure, the rhythmic, even grammatical structure that someone gives to their speech. And actually, the whole person is included in speech.

One can say that because this is the case, eurythmy can be contrasted with sculpture, which reveals the inner life of the human being through the calm human form. And anyone who has a feeling for this will sense in the sculptural work that depicts the human being what kind of temperament, what kind of character, even what kind of mood, inclination, or passion the soul of the human being being depicted has. But one always has the feeling that it is the calm, silent soul that comes to the fore through sculpture. But when the soul speaks, it does not want to reveal the resting human form, but the moving human being. So one can say: sculpture depicts the silent soul in its own nature; eurythmy depicts the soul speaking inwardly.

On the one hand, the soul speaks through poetry. And when it speaks as a soul—and ordinary language is more for external communication or for reproducing knowledge—but when the soul speaks, it speaks in rhythms, in time, in musical or vocal images, in the imagination. Or the soul speaks by revealing its innermost being through music. Just as just as one can recite and declaim what poetry brings forth, just as what can be expressed in the soul as emotional tensions, resolutions, and so on through music, and one can accompany the music in tonal singing, so too can one speak visibly in eurythmy through movements, and one can sing to instrumental music in visible song, also through movements. When you see in the following presentation which movements accompany the instrumental music in the musical pieces, you will feel and sense the difference between dance and what is presented here as eurythmy. Accompanied by music, this is not dance, it is visible singing. It is something different from dance.

Now, it must be said that a deeper understanding of the entire human organism is required in order to translate the spoken language, which has concentrated the movement potential of the whole human being in the larynx and its neighboring organs, back into movements, so that the movements speak just like the spoken language. But when viewed directly, eurythmy should by no means have an effect by always speculating on what this or that movement means, but rather the individual movement and the sequence of movements should have an effect through direct viewing and direct impression. And in this respect, what appears here as eurythmy has a thoroughly musical character.

And [because] musicality is expressed in the sequence and simultaneity of sounds in such a way that [it] corresponds to eurythmy in the sequence of movements and in simultaneity — as well as in beat, rhythm, and so on — this should actually be a joy to anyone who has a sense for the expansion of art in its means. — It is actually astonishing that anyone could say that art should not be expanded in the way that it is expanded through eurythmy.

I should also mention that when recitation and declamation occur in parallel with eurythmy, it becomes clear in the recitation how invisible eurythmy is already present in real poetic language. Today, in a somewhat unartistic age, people tend to prefer emphasizing the prose content when reciting and declaiming poetry. Goethe, with his baton in hand like a conductor with his actors, rehearsed his own iambic dramas because he placed much more value on the musical and artistic aspects of language than on the prose content in the external presentation. And the real poet, the one who is an artist as a poet, does not primarily have the prose content, the novella-like aspect, in mind, but rather the shaping of language, which takes place either in the imaginative sound design, the rhythmic design of the sentence, the rhyme design, and so on, or he also has the musical aspect in mind. So that recitation and declamation are also promoted in a way by eurythmy, in that the actual artistic nature of poetry, the musical and plastic-picturesque nature of language, are expressed, rather than the prosaic point.

That is why the recitation and declamation offered here, which has been developed by Dr. Steiner over many years, is still considered somewhat strange today — as is eurythmy as a whole. So it is fair to say that eurythmy is still in the early stages of its development, and we are well aware of this. And we are our own strictest critics, knowing that we can still achieve very little of what is possible in eurythmic expression. But on the other hand, eurythmy is the art that actually uses the most perfect, the most self-contained instrument, namely the human being, the living human being itself, not an external instrument, but the living human being itself. This living human being is a small world in itself. Everything that is contained in the greater world in the broadest sense of secrets and laws is carried within this human being. And when one seeks out the beautiful movements in the human form, then one can also bring out of these movements, I would say, everything artistic in the universe. And what emerges is truly a microcosmic artistic representation of the great macrocosmic work of art, brought about, one might say, by the human being.

Therefore, precisely because the human being itself is used as an instrument for this speaking sculpture, for this now moving sculptural art, one may believe that — as imperfect as it still is today in its infancy, this eurythmy — will one day reach its perfection, enabling it to stand alongside the older arts as a fully-fledged art form.

>Ballade in As-Dur, Op. 47,3 von Frédéric Chopin

«Schön-Rohtraut» von Eduard Mörike

«Intermezzo in As-Dur» von Johannes Brahms

«Um Mitternacht» von Eduard Mörike

«Waldesrauschen» von Franz Liszt

«Vom Sieben-Nixen-Chor» von Eduard Mörike

Romanze in F-Dur, Op 118,5 von Johannes Brahms

«An den Mistral» von Friedrich Nietzsche

Etude in E-Dur von Frédéric Chopin

«Christine» von Charles Leconte de Lisle

«Warum» von Robert Schumann

«An den Mistral» von Friedrich Nietzsche

Prelude in H-Dur von Frédéric Chopin

«Die Tafeln» von Christian Morgenstern

Gavotte von Giovanni Mossi

«Der Bahnvorstand» von Christian Morgenstern

Gavotte in D-Dur von J. S. Bach

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden! Nicht um die Eurythmie-Vorstellung etwa zu erklären, will ich einige Worte vorausschicken. Kunst erklären ist unkünstlerisch, und Eurythmie soll vor allen Dingen eine wirkliche Kunst darstellen. Sie werden eben eine Kunst sehen, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, welche wirken will durch heute noch ungewohnte Kunstmittel, durch eine auch noch ungewohnte künstlerische Formensprache, und über diese Kunstmittel und diese künstlerische Formensprache lassen Sie mich nur zur Verständigung einige Worte vorausschicken.

Sie werden dreierlei sehen und hören: den bewegten Menschen und bewegte Menschengruppen auf der Bühne, Rezitatorisches und Deklamatorisches auf der einen Seite und Instrumental-Musikalisches auf der anderen Seite. Immer soll dasjenige, was Wort sein kann oder was musikalisch Tongebilde sein kann, auch durch den bewegten Menschen zum Ausdrucke kommen - entweder den in sich, in seinen Gliedern bewegten Menschen oder auch durch Menschengruppen, die Bewegungen im Raume ausführen. Das sieht zunächst aus, als ob eine Kunst beabsichtigt wäre, die so eine Art Gemisch ist von Mimischem und Tanzartigem. Ohne dass gegen diese Nachbarkünste das Geringste eingewendet wird - sie sollen selbstverständlich voll anerkannt werden -, will aber Eurythmie beides nicht sein: weder Tanz auf der einen Seite, noch mimische Kunst auf der anderen Seite, sondern sie will eine wirklich sichtbare Sprache ausgestalten.

Dasselbe, was in der Lautsprache zur Offenbarung kommt, indem das Innere der menschlichen Seele sich durch die Organe offenbart in einer physischen Weise, durch die bewegte Luft und gewissermaßen mit Hilfe einer Luftgeste das Hörbare erzeugt wird - genau in derselben Weise wie in diese Luftgeste, die bei der Lautsprache zum Vorschein kommt, das Seelische hineinfließt, so soll in durchaus gesetzmäßiger Art das Seelisch-Geistige, das im Menschen lebt, hineinfließen in seine Bewegungen, namentlich in die ausdrucksvollsten Bewegungen, die der Arme und Hände. Und geradeso, wie ein bestimmter Laut und eine ganz bestimmte Lautfolge in der Sprache einem seelischen Inhalt entspricht, ebenso ist es bei dieser Eurythmie, dass eine ganz bestimmte Bewegung eines menschlichen Gliedes oder eines Systems von menschlichen Gliedern in gesetzmäßiger Weise einem seelischen Inhalte entspricht. Ebenso wenig wie man in einem Worte, in dem an irgendeiner Stelle ein o steht, ein a setzen kann, ebenso wenig kann man in dem Eurythmischen da, wo eine Streckbewegung des einen Armes ausgeführt wird, etwa einen halben Kreis oder eine halbe Kreisbewegung mit einem oder mit beiden Armen ausführen. Es ist eben durchaus möglich, dass der Mensch genauso, wie er sich ausdrückt in der Lautsprache, so sich auch zur Offenbarung bringt durch die Bewegung seiner Glieder. Ja, es besteht ein gewisser Zusammenhang schon in der natürlichen Organisation des Menschen zwischen der Bewegungsmöglichkeit der Glieder des Organismus und der Lautsprache.

Das heutige Wissen weiß eigentlich davon sehr wenig, aber etwas Auschlaggebendes: Diejenigen Menschen, die Rechtshänder sind, tragen das Sprachzentrum ihres Gehirns auf der linken Seite. Und dadurch, dass man auf der anderen Seite feststellen kann, wie die wenigen Linkshänder, die wir antreffen, das Sprachzentrum dafür auf der rechten Seite des Gehirnes haben, dadurch kann man annehmen - und alle Tatsachen, die man sorgfältig prüft und die man hin orientiert auf diese Erkenntnis, belegen das —-, man kann durchaus annehmen, dass im kleinen Kinde dasjenige, was sich aus der Seele heraus offenbaren will, ebenso in Arm und Hand sich ergießen will, wie es sich ergießt auf der anderen Seite in das innerliche Weben und Leben, das von dem Sprachzentrum des Gehirnes dann als Anregung ausgeht, um den Laut und die Lautzusammenhänge der Sprache hervorzubringen.

Derjenige, der nun in anthroposophischer Art, wie sie hier gepflegt wird am Goetheanum, diese Zusammenhänge weiter [unter-] sucht, der bekommt zwischen allen Bewegungsmöglichkeiten des menschlichen Organismus und zwischen demjenigen, was in der Lautsprache zum Ausdruck kommt, nicht etwa nur Analogien, sondern ganz gesetzmäßige Zusammenhänge. Sodass man wirklich sagen kann: Ein Kenner dieser Zusammenhänge errät eigentlich, sagen wir aus der Art und Weise, wie irgendjemand auftritt - ob mit den Fersen mehr oder mit den vorderen Füßen mehr, ob er die Knie mehr oder weniger beugt oder dergleichen -, der Kenner errät, welche besondere Stilisierung in der Sprache der betreffende Mensch hat. Denn nicht nur der Arm und die Hand drücken sich in den eigentlichen, der Sprache zugrundeliegenden Denkorganen aus, sondern der ganze Mensch. Und zwar zum Beispiel in der Betonung der Sprache: Ob man Hochton, Tiefton anwendet, drückt sich aus in Bewegungen der Füße, der Beine. Wiederum die ganze Artikulation des Gesichtes, sie kommt in der inneren Gliederung, rhythmischen, selbst grammatikalischen Gliederung, die jemand seiner Sprache angedeihen lässt, zum Ausdrucke. Und eigentlich ist in die Sprache der ganze Mensch hineingeschlossen.

Man kann schon sagen: Dadurch, dass das so ist, kann man entgegenstellen der Bildhauerkunst, die durch die ruhige menschliche Form das Innere des Menschen offenbart, diese Eurythmie. Und wer ein Gefühl dafür hat, wird in dem bildhauerischen Werke, das den Menschen zur Darstellung bringt, fühlen, welcher Art, welchen Temperamentes, welchen Charakters, ja selbst welcher Laune unter Umständen, Neigung, Leidenschaft die Seele des Menschen ist, die dargestellt wird. Aber man hat immer das Gefühl, es ist die ruhende, die schweigsame Seele, die durch die Bildhauerkunst zum Vorschein kommt. Redet aber die Seele, dann will sie nicht die ruhende Menschenform zur Offenbarung bringen, sondern den bewegten Menschen. So kann man sagen: Bildhauerkunst stellt dar die schweigende Seele in ihrer Eigenart; Eurythmie stellt dar die innerlich redende Seele.

Die Seele redet auf der einen Seite durch die Dichtung. Und wenn sie als Seele redet - und die gewöhnliche Sprache ist ja mehr zur Verständigung nach außen oder zur Wiedergabe der Erkenntnisse -, aber wenn die Seele redet, dann redet sie in Rhythmen, im Takt, im musikalischen oder im lautlichen Bilde, in der Imagination. Oder es redet die Seele, indem sie ihr Innerstes zum Vorschein bringt, durch das Musikalische. Geradeso, wie man dasjenige, was die Dichtung bringt, rezitieren und deklamieren kann, geradeso wie dasjenige, was als Gefühlsspannungen, Lösungen und so weiter in der Seele durch das Musikalische zum Ausdruck kommen kann und man das Musikalische im tonlichen Singen begleiten kann, ebenso kann man sichtbar sprechen in der Eurythmie durch Bewegungen und man kann singen zu dem Instrumental-Musikalischen im sichtbaren Gesange ebenso durch Bewegungen. Gerade, wenn Sie sich in der folgenden Darstellung anschen werden, welche Bewegungen das InstrumentalMusikalische in den musikalischen Stücken begleiten, so werden Sie fühlen, empfinden den Unterschied zwischen Tanz und dem, was hier als Eurythmie dargestellt wird. Das ist in Begleitung des Musikalischen nicht Tanz, das ist sichtbarer Gesang. Das ist etwas anderes als Tanz.

Nun muss man allerdings sagen: Es gehört zunächst eine tiefere Erkenntnis der ganzen menschlichen Organisation dazu, um gewissermaßen die Lautsprache, die aus der Bewegungsmöglichkeit des ganzen Menschen sich konzentriert hat auf Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane, um die wieder zurückzuführen in Bewegungen, sodass die Bewegungen geradeso sprechen wie die Lautsprache. Aber im unmittelbaren Anschauen soll Eurythmie durchaus nicht etwa dadurch wirken, dass man immer spintisiert, was das und was jenes als Bewegung bedeutet, sondern da soll wirklich die einzelne Bewegung und die Folge der Bewegungen in unmittelbarem Anschauen und in unmittelbarem Eindrucke wirken. Und in dieser Beziehung hat dasjenige, was hier als Eurythmie auftritt, durchaus einen musikalischen Charakter.

Und [dadurch,] dass Musikalisches in der Aufeinanderfolge und Gleichzeitigkeit der Töne zum Ausdrucke kommt so, dass [dem] eurythmisch in der Aufeinanderfolge der Bewegungen und in der Gleichzeitigkeit entsprechen - ebenso wie Takt, Rhythmus und so weiter —, dadurch sollte eigentlich jeder eine Freude haben, der einen Sinn dafür hat, dass die Kunst in ihren Mitteln erweitert werde. — Man ist eigentlich erstaunt darüber, dass davon gesprochen werden kann, dass die Kunst nicht so erweitert werden soll, wie sie durch Eurythmie eben erweitert wird.

Zu erwähnen habe ich noch, dass nun, wenn die Rezitation und Deklamation in Parallele auftritt mit der Eurythmie, dass dann gerade an der Rezitation anschaulich wird, wie eigentlich in der wirklichen dichterischen Sprache schon eine unsichtbare Eurythmie drinnen ist. Heute liebt man es zwar - als in einer etwas unkünstlerischen Zeit heute -, heute liebt man es zwar mehr, auch in einem Gedichte beim Rezitieren und Deklamieren den Prosainhalt zu pointieren. Goethe hat mit dem Taktstock in der Hand wie ein Kapellmeister mit seinen Schauspielern selbst seine Jambendramen einstudiert, weil er viel mehr Wert legte bei der äußeren Darstellung auf das Musikalisch-Künstlerische der Sprache als auf den Prosainhalt. Und der wirkliche Dichter, derjenige, der als Dichter Künstler ist, der hat im Grunde genommen nicht als Hauptsächlichstes den Prosainhalt, das Novellistische im Sinn, sondern er hat im Sinne die Gestaltung der Sprache, die da verläuft entweder im Imaginativen der Lautgestaltung, der rhythmischen Gestaltung des Satzes, der Reimesgestaltung und so weiter, oder er hat auch im Sinne das Musikalische. Sodass auch Rezitation und Deklamation gewissermaßen in der Art von der Eurythmie gefördert werden, dass das eigentlich Künstlerische der Dichtung, das Musikalische und Plastisch-Malerische der Sprache zum Ausdruck kommen, nicht die prosaische Pointierung.

Deshalb wird man auch die Rezitation und Deklamation, die hier geboten wird, die von Frau Doktor Steiner durch Jahre hindurch ausgebildet worden ist, heute auch noch als etwas Befremdliches fühlen — wie die ganze Eurythmie. Also man darf schon sagen: Eurythmie steht heute im Anfange ihrer Entwicklung, und das wissen wir ganz gut. Und wir sind selbst unsere strengsten Kritiker, wissen, dass wir noch wenig von dem wirklich leisten können, was an Möglichkeiten in der eurythmischen Darstellung liegt. Aber auf der anderen Seite ist Eurythmie die Kunst, die eigentlich das vollkommenste, das in sich geschlossenste Instrument, nämlich den Menschen, den lebenden Menschen selbst benützt, nicht ein äußeres Instrument benützt, sondern den lebenden Menschen selbst. Dieser lebende Mensch ist nun einmal eine kleine Welt, Alles dasjenige, was in der großen Welt in weitestem Umfange an Geheimnissen und Gesetzmäßigkeiten enthalten ist, trägt dieser Mensch in sich. Und wenn man an des Menschen Form die schönen Bewegungen heraussucht, dann kann man aus diesen Bewegungen heraus eben auch hervorholen, ich möchte sagen alles Künstlerische des Universums. Und es entsteht wirklich eine, man möchte sagen durch den Menschen bewirkte mikrokosmische künstlerische Darstellung des großen makrokosmischen Kunstwerkes.

Deshalb darf man glauben, gerade aus dem Grunde, weil der Mensch selbst als ein Instrument zu dieser redenden Plastik, zu dieser nun bewegten Bildhauerkunst verwendet wird, dass - so unvollkommen sie heute noch dasteht in ihrem Anfange, diese Eurythmie - sie einmal doch zu ihrer Vollkommenheit kommen werde, die sie an die Seite der älteren Künste als eine vollwertige Kunst hinzustellen in der Lage sein wird.