Eurythmy as Visible Speech

GA 279

XII. The Outpouring of the Human Soul into Form and Movement: The Curative Effect of this Upon the Moral and Psychic Nature and its Reaction upon the Whole Being of Man

9 July 1924, Dornach

My dear Friends,

We will now pass on to certain things that have arisen out of the fundamental nature of eurhythmy, things that are, up to a point at least, known to you already; and we will then establish a connecting link between what I have been speaking about and what you already know.

The first thing I wish to speak about is this: We have seen how what might be described as certain moral impulses, which we have brought before our souls in the numbers twelve and seven, find their expression in human gesture, in gesture which is either static or permeated with movement; and we have seen how thought, in the sense of eurhythmy, is altogether possible on the strength of experiences and judgments of the human soul, which shed themselves into the sounds of speech.

That which thus streams out from the human soul in gesture and movement can, however, also work back upon the human being as a whole. And this is the basis of the curative action of eurhythmy, which may be effective, not only in the sphere of the moral and psychic life, but also in the physiological, physical life.

The curative action of eurhythmy upon the meal and psychic life will be especially apparent when certain eurhythmic principles and facts are applied during the years of childhood.

Now starting from this standpoint—from the way in which on the one hand form and movement arise from a certain mood or attitude of soul and then react back once more—I should like to speak further of certain things which have already been dealt with, so that in these next days we may gain a somewhat wider outlook and make another step forward in the development of speech eurhythmy.

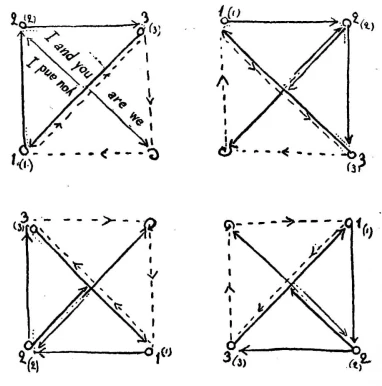

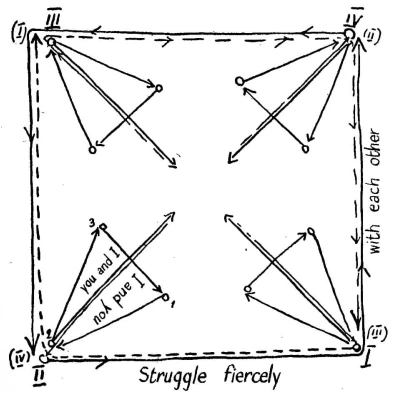

You will all know the exercise that is specially adapted to bring one person into contact with another; the so-called I and You exercise. You stand in a square; on account of the audience, however, the two at the back must be a little closer together. And now you can do this exercise in the following way: I and you, you and I, I and you, you and I—are we. Here you have a real ‘we’, the final joining together in the ‘we’ (circle). The two who face each other in a diagonal direction are intended as the ‘I’ and ‘you’. As you approach each other you must clearly express the fact that you wish to belong one to the other and that the others also wish to belong to the circle; the diagonal line expresses the transition from the ‘I’ to the ‘you’, you and I... then retrace the line (this can be done many times in succession)... then the whole is consciously brought together: are we. If the exercise is to be repeated one can return to the starting places with you and I, you and I.

Such an exercise can be worked out in the most varied ways, taking as one’s basis such aspects of the soul life as we have learned to know during the last few days.

Let us now suppose, Frl. V… that you are the Eagle, you Frl. St... Aquarius, you Frl. S... Taurus, and you Frl. H... Leo. Now make the gestures. You take these gestures as the starting point and return to them when the whole exercise is completed.

You must realize what you have thus expressed. You have, by means of this exercise, expressed the fact that the human being contains these four animals within himself in their aspect of moral qualities, and that when he becomes conscious of his true self, he understands that the whole human race is contained within his own being—thus, as man he really comprises the ‘we’. Begin with these gestures... follow with the exercise... then pass with a certain grace back to the first gestures. Here we have an example of how these things which we have just learned may be applied.

In this way the whole exercise is brought to a right conclusion. Preliminary gestures; I and you, you and I, I and you, you and I, are we; concluding gestures. You then have the right intro-duction and the right conclusion, and the whole thing stands, as it were, enclosed in a frame.

Now this exercise is most excellent in the teaching of eurhythmy from an educational point of view. Indeed, when one has observed in a child the tendency towards jealousy and ambition—qualities which one wishes to eliminate—one must persuade such a child to do this exercise with special warmth and ardour. In the art of education it is, of course, obvious that one must never apply anything having the least trace of what might be called magic; for anything of the nature of magic would work with a powerful suggestive element. It would react on the unconscious life of the child. Such means can only be used in the case of children of weak mentality, of deficient children; it is only permissible in such cases. When, however, abnormal characteristics are present in the soul life of the child it is absolutely necessary to work directly into the psychic life—though here, too, of course, one must avoid anything in the nature of actual suggestion or magic. Now what really happens when four children do this exercise? They hear the constant repetition: ‘I and you ’. This brings to their consciousness the element of belonging together, of comradeship, the element of relationship to other human beings, and this is further impressed upon them in the: ‘are we’. The gestures accompanying the exercise simply express the fact that the child is learning to pay attention to what is being done, to what is inwardly working upon him. Thus there is not the least trace of suggestion. It can really be said that this dance is a remedy against jealousy and false ambition. It can only be used in the case of healthy children when it is carried out with full consciousness, quite without anything in the nature of suggestion or magic.

But now you will ask: How does the case stand with pathological children? With pathological children one has to reckon with a consciousness that is already dimmed and clouded. Then, to a certain extent, suggestion does come into play. For this reason, the moment one enters the sphere of the pathological in children, one must clearly realize that although this exercise may be applied with excellent results to children whose consciousness is dulled, it should never be used with children whose minds are over active.

It is such things as these, which prove that everything in the domain of curative eurhythmy must only be applied in close co-operation with a doctor and when working under constant medical supervision; for as soon as we enter the domain of the pathological, only a doctor is qualified to form an opinion.

Let us pass to another exercise or dance, which has arisen out of a definite attitude of soul. In order to give this exercise a name, we have called it the Peace Dance. And this Peace Dance serves the purpose of teaching one individual in conjunction with others how certain nuances of the soul life may find their expression in eurhythmic forms.

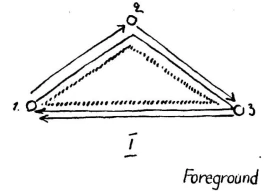

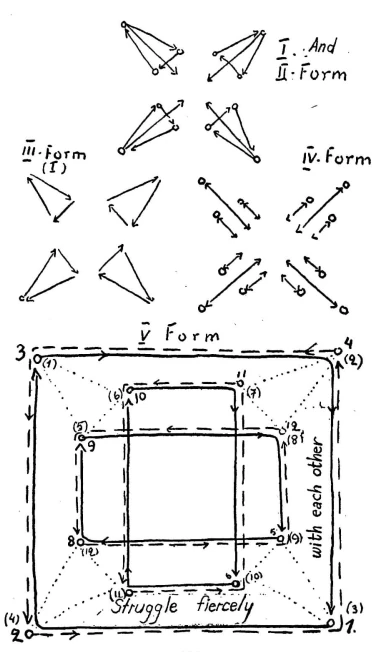

Let us suppose that you make some sort of a triangle. Make it so that the form looks something like this:

Now one person can walk the lines of the triangle in this direction (arrow); or we can have three people, of whom the first takes this line, the second this line and the third this line (see diagram).

When you look at this type of triangle and compare it with one of the following type:

you have a considerable difference. In the first case one line is conspicuous on account of its length in comparison to the two other lines, and in the other case it is conspicuous because it is comparatively so short. Even when the exercise is carried out in precisely the same way, we receive a quite different impression.

In the first case we have the impression of peace; in the second case, when we do the exercise according to diagram II, the form gives the impression of energy. So that we may say: In the first place we have a Peace Dance and in the second place an Energy Dance.

The essential thing in such a eurhythmic exercise is that we should carry it out rhythmically. And when we now ask ourselves: How should such an exercise be carried out? We must bear in mind that in a descending rhythm we have what might be described as something ordered and under control, while in an ascending rhythm we have an element of striving, of will.

Now when we enter either into the mood of peace or into the mood of energy we have something of the nature of striving, of working towards some goal—something quite different from what we should have to employ when it is a question, for instance, of expressing a military command. This expression may sound worse than I intend; a military command may, however, be employed simply to train the children, by means of certain movements, to be attentive. But nothing in the nature of a command or order can be expressed in this exercise, which demands a particular attitude of soul. It must have a feeling of ascent, of intensification; it needs the Anapaest rhythm.

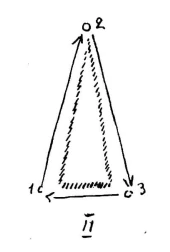

Now I will ask Frl. S... to show us the first triangle as I have described it; the lines of the triangle must be stepped in Anapaest rhythm while I say the following words:

Strebe mach Frieden, (Strive for Peace,)

Lebe in Frieden, (Live in Peace,)

Liebe den Frieden. (Love Peace.)

Do it in such a way that the long line faces the audience and that you show the intensification in the long line—thus you must take your start from this point (1); you only move backwards in order that you may be seen by the audience. Now when practising this you will find the fact that the sentences are not built up according to the Anapaest rhythm somewhat disagreeable to the ear. But this does not matter; you must feel the movement, even if this rhythm does not actually lie in the words. It is just in this way that the language of eurhythmy may express something which cannot be fully expressed by language itself—for there is no German word for peace which ends with an emphasized syllable. Let us try it once more:

Strebe nach Frieden,

Lebe in Frieden,

Liebe den Frieden.

(see previous diagram).

Show the Anapaest very distinctly. The words are in the Dactyl rhythm, but in spite of this they must be stepped to the Anapaest; the rhythm does not go with the words, nevertheless the dance, must be done in the Anapaest, without allowing oneself to be disturbed by the words. It would be better to use a text written in Anapaest rhythm, otherwise there must be a certain disharmony, which is naturally disturbing to the ear.

Will you now do the next exercise? Here one must move, in Anapaest rhythm, the triangle that has the short main line. Start once more from this point (1); try also to emphasize the form of the triangle by stepping the long side lines quickly, the, short main line with a quite slow Anapaest. This exercise may, be called the Energy Dance.

These two exercises may, however, be carried out by a group. Let us now choose three people, who will first do the Peace Dance, taking their places in a triangle and each one moving one line only. This can naturally be done to a suitable text, which must be in the rhythm of the Anapaest.

But this exercise can be done in yet another way. Triangles of similar shape, but small, may be formed in the four corners. Indeed this exercise may be carried out with any number of variations; but each variation must have some special note of its own. The best way perhaps, is for those standing at the point marked 1 to begin the form; they begin, and each one carries out a complete triangle—but simultaneously. Eurhythmy depends to a certain extent upon presence of mind. Each separate triangle must do a form similar to the triangle that previously took up the whole of the stage. Now all those standing at the back of the triangle, thus those whom I have placed in the corners, must do the I and you as the second part of the exercise: I and you, you and I, I and you, you and I: are we. Those who stand in the middle simply turn round. The triangle is thus built up in a different way. Those who now form the square must once more carry out the Peace Dance from their present places—the movement three times. When this is done smoothly and well it forms an exercise complete in itself.

From an educational point of view, as also from the point of view of curative education, this exercise, as we have just done it, is of special value. One can make the group smaller using two or three triangles, but one can still carry the exercise out in a similar way. It is especially good to practise this exercise when one has, for instance, a class containing children of choleric temperament, children who will not be kept in order.

Such children must be made to practise these exercises; and if this is done every day, or as often as there is a eurhythmy class, for a period of two or three weeks, one will find that they have become more manageable. Thus children who are always hitting each other and rampaging about should be made to practise this exercise, and you will see that it has a remarkable power of soothing and quieting them.

Now we can do the Energy Dance in a similar way. Here again we must form our four triangles, but pointed triangles this time. Let us move the form of the triangles three times. Four eurhythmists will now be standing in the corners (see diagram), and they must do the following exercise: Begin with the u, ‘You and I’; with the ‘I’ you are in the centre; now you have not the same gesture as you had for the ‘you’ but you have a gesture which looks, as you stand together, as if you were going to attack one another. Go back once more from the ‘I’ into the ‘you’, and do this three times. Now you have reached a position from which we must go further. In the first place we do, as it were, the I and you exercise reversed, thus a you and I exercise: You and I, I and you, you and I, I and you, you and I, I and you—now you are standing at the back, and to continue the exercise you must run past each other crossing on the way (the four at the outer points changing places). Thus we go towards the centre; You and I, I and you; you and I, I and you; you and I, I and you, struggle fiercely with each other, struggle fiercely with each other (streiten heftig miteinander)! And now again the original exercise in the triangle three times repeated.

Do the whole exercise once more: the triangle three times, then the separating movement, then the triangle again.

In order to show you how such exercises may be multiplied and varied, we will do it as follows: move the triangle for the first time, for the second time, for the third time; now you must regard all those standing in the triangle as involved in the struggle. Thus do the form: You and I, I and you, you and I, I and you, struggle fiercely with each other, (thus everybody who is taking part); then make the triangles once more, repeating the form of the triangle three times.

It is, of course, comparatively easy to find poems of three verses built up in such a way that they may be practised to this form.

I should like to point out once more that it is quite possible to apply what you have just seen to education and also to curative education. This exercise has an especially beneficial effect upon children who are phlegmatic and sleepy. They will be stimulated by it; it will give them more inner vitality. That is what I had to say in this connection.

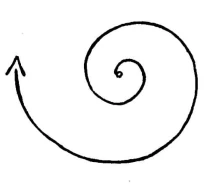

Today we will take still another exercise, which is based more directly on the actual form. Out of the form itself you will feel what is intended. Frau B... will you try to run a spiral form winding from within outwards.

The way you did this was perfectly right. You began with quite noticeable movement, that is to say, with the hands laid against the heart... and you ended with the arms held in a backward direction. When you observe the movement of this form you will find that it is well suited to express the going out of oneself, the gaining of interest in the outer world, and finally the yielding of oneself up to the world, which is expressed in the backwards movement of the arms. Do it once more, bearing in mind what I have said. You will feel that there is first a seeking in oneself, afterwards a becoming aware of the world outside, and then a yielding of oneself up to this world. Now run the reversed spiral; take the line from without inwards, in the first half of the form holding the hands more in a backward direction, and in the second half laid against the heart. You see this is just the reverse of the former line; it is a gathering together of one’s forces; it is a coming back from the outer world into one’s own being.

In curative education, this first spiral exercise is especially applicable to children who are the reverse of anaemic, and it can be applied to combat undue egoism; the second exercise may be applied where the ego-force is weak, and it is also an excellent remedy in the case of children who are anaemic.