Eurythmy as Visible Speech

GA 279

XV. In Eurythmy the Entire Body Must Become Soul

12 July 1924, Dornach

To-day we must bring this course of lectures to its conclusion. It has, naturally, only been possible to give certain guiding lines; much still remains unsaid and must be reserved for a future occasion. It seemed to me better to develop these guiding lines in a really fundamental way out of the nature of eurythrny itself, rather than to attempt a more encyclopedic survey of the whole domain of eurythmy.

It is of the greatest importance that each individual eurythmist should strengthen this power of creating the movements out of an inner activity, for it is in this way alone that a true understanding for eurythmy can be developed.

I shall deal first (my attention having been drawn to the matter) with the two sounds g and v (German w). Let us first take the g. In modern languages,—in modern European languages, at least,—this sound has not the same significance as it had in earlier times. For this reason we have not considered it until now. The sound g, when properly formed—gg—signifies an inner strengthening of the self, a strengthening of the soul-forces, a concentrating in itself of everything in the human being which naturally spreads outwards. It is therefore the sound of speech which, so to speak, holds our being together, in so far as the latter is a vessel for natural forces. This is the sound g.

Perhaps Frl. V. . . . will make the movement for g, in order that you may see how well the character of this gesture is adapted to show this inner strengthening and concentration. The warding off of everything external and the welding together of everything inward is expressed in the gesture for g.

Now we come to the remarkable sound v. We find this sound less frequently in the more ancient languages, in the Oriental languages that is to say. It expresses a special need of the human soul. It is as if the human soul were not used to the shelter of a firmly-built structure, but felt compelled to wander. Instead of the firmly-built house which may be experienced in the b-sound, instead of this solid house, the soul feels the need of a tent, or of the shelter of the woods. In the v-sound there lies the feeling of what may be described as a moving shelter.

This is why one always feels, with the sound v, that one is, as it were, carrying a shelter which is constantly being set up anew. Everything of a wandering nature, where the essential element is movement, must be experienced in this sound. It is the surging of the waves which is expressed by a strongly formed v; when delicately formed it expresses the sparkling of the waters. This will help you to realize what must be felt in the sound v. Now it is a remarkable fact that, when using the sound v (German w), one quite naturally finds oneself repeating it. One feels compelled to repeat it several times in succession. Something seems amiss if one simply says: ‘es wallet’; one wishes to say: ‘es wallet und woget, es weht und windet, es wirkt und webt,’ and so on. There is, in short, no sound which leads so naturally into the sphere of alliteration as this sound v. An alliteration can be made up with other sounds, but in no other way will it come about so naturally.

Perhaps Frl. S. . . . will demonstrate the sound v. You see how it demands a gesture filled with movement. V may thus be said to be that sound which permeates being with movement. Will you now show us, just going round in a circle without actually showing the structure of the alliteration,—we shall add this shortly, an alliteration built up on the sound v. In this example there are also other alliterated sounds; but observe how slight an impression they make when compared to one built up on the v-sound (German w). Thus we have

Wehe nun,

Waltender Gott,

Wehgeschick naht.

Ich wallete

der Sommer und Winter Sechsig ausser Landes,

Wo man mich immer scharte

(now comes the other alliteration)

In die Schar der Schntzen,

Doch vor keiner Burg Man den

Tod mir brachte.

Then we have a very marked alliteration, built up on m; you will feel this strongly, yet not so strongly as in the case of v:

Nun soll mein eigenes Kind

Mich mit dem Schwerte hauen,

Morden mich mit der Mordaxt!

Oder soll ich zum Morder werden?

One cannot help feeling that every alliteration based upon the v-sound appears to come about quite as a matter of course, whereas all other alliterations, no matter what sound is repeated, have the effect of being drawn out from the v.

Alliteration is an essential and fundamental element in poetry, especially where the sound v is experienced in a living way. In this connection we must develop a two-fold feeling. In the first place there lies in the nature of alliteration,—that is to say, when the first letter of certain words is repeated,—something which takes us back into earlier stages of European culture. Wilhelm Jordan has attempted to revive alliteration, and has indeed succeeded in introducing it into his work with a certain strength and conviction. In modern German this element of alliteration appears somewhat out of place. A feeling for it, however, can always be recaptured if one has the gift of going back in imagination to an earlier epoch. The short poem which I have read to you is taken from the Song of Hildebrand. Hildebrand was long absent from his native country, and on his return journey he met his son Hadubrand with whom he came into conflict. It is the battle between these two which is related in this alliterative form,—a form which was at that time an instinctive and completely natural means of expression.

An alliteration may be shown in the following way: Let a number of eurythmists form a circle, and now,—because the very essence of alliteration is consonantal, although not invariably based upon the v-sound,—they must emphasize the alliterated consonants by stepping round this circle. The vowel sounds do not form part of the alliteration; for this reason they may be shown by another group of eurythmists who stand inside the circle, making the movements for the vowels.

I will ask several of you to show the alliteration in the poem I have just read. Will you take your places in the circle; and now three others must stand in the centre and show the vowels.

The alliteration will be particularly strongly emphasized if, whenever a new alliterated sound occurs, it is shown by a different eurythmist, the preceding eurythmist at the same time repeating the previous sound. Only those vowels which follow directly after the alliterated consonant should be shown by those in the outer circle. The other vowel-sounds must be done more as an accompaniment by those standing in the centre. In order to make the whole thing quite clear let us take this example and do it quite slowly, those in the outer circle moving to the alliteration:

Wehe nun,

Waltender Gott,

Wehgeschick naht.

Ich wallete

Der Sommer und Winter

Sechsig ausser Landes,

Wo man mich scharte

In die Schar der Schützen,

Doch vor keiner Burg

Man den Tod mir brachte.

Nun soll mein eignes Kind

Mich mit dem Schwerte hauen,

Morden mich mit der Mordaxt!

Oder soll ich zum Mörder werden?

The alliterated consonant and the vowel sound immediately following it must be carried round the circle from one eurythmist to the next.

This will show you how in fact movement, and also restraint may be brought into such a poem sheerly by means of alliteration.

We will now pass on to something else, something which will help us to make of the human organism a fitting instrument for the service of eurythmy. In this connection it is very necessary to gain an understanding of the difference in eurythmy between walking and standing. Standing still always signifies that one is the image, the picture of some-thing. Walking, on the other hand, signifies that oneself will actually be something. When working out a poem in eurythmy you must be able to feel whether, at a certain point, it is a question of describing or indicating something or of representing the actual nature of something in a living way. It is according to this that one must decide whether to stand still (a lessening of the movement tends already in this direction), or whether to pass over into movement. We shall find that we have less occasion to stand still than to move, for there lies in the very nature of poetry the tendency to express something living, something which is, not merely that which signifies something. Here it is well that we should know how the human body is related to the whole cosmos. The feet of man correspond to the earth, for in their very structure they are suited to the earth, Where we have to do with gravity, with the weight of the earth,—and this feeling of the weight of the earth is present in nearly all forms of human suffering,—we must endeavour to express this in eurythmy by a graceful use of the feet and legs.

The hands and arms reveal the life of the soul. This soul-element is the most essential part of what may be brought to expression in eurythmy, and this is why in eurythmy the movements of the arms and hands play such an important part. Here already we pass over into the realm of the spiritual, for it is in the transition from one sound to the next that we find the best means of expressing that which is spiritual. In language the spiritual element finds expression in the mood of irony, for instance, or roguishness, in every-thing that is to say which emanates from the human spirit (aus dem menschlichen Spiritus), from man himself in that he is a spiritual being, gifted with intelligence in the best sense of the word. Such things must be indicated by means of the head, for the head is the instrument of the spirit.

We must become conscious of such things; then we shall be able to express them in the right way. It is specially important to be able to use the head in the most varied manner according to the possibilities of its organization.

Fri. S. . . . will you turn your head towards the right. The turning of the head towards the right may always be taken to signify: ` I will ' ; naturally I do not mean these two words merely, but everything which contains the feeling: ` I will.'

On the other hand, when you turn your head towards the left it signifies : I feel.' Thus, everything in a poem where the mood of `I feel' is dominant we must turn the head towards the left.

Now bend the head towards the right. This bending movement of the head (forwards towards the right) signifies: ` Iwill not.' Bend it in the same way towards the left and it signifies: ` I do not feel this, I do not understand it or realize it.'

And now bend the head forwards, straight forwards. You will see how natural this movement is if you do the following: Frau Sch. . . . will you stand facing Frl. S. . . . in profile, and do these movements. We must suppose that Frau Sch. . . . says: ` It is the gods who inspire the human heart with willing service.' Frl. S. . . . gives an eurythmic answer: ` You are too clever for me; I do not understand you.' She shows this by means of the aforesaid gesture, carried out clearly and definitely. You will find numberless opportunities of applying this movement. It signifies a sinking into oneself when faced with something which one is not able to understand.

Then, further, so that we may have at least one example, I must point out that the twelve gestures related to the Zodiac and the seven gestures related to the moving planetary circle may be made use of in a variety of ways. Quite apart, for instance, from what was said yesterday with regard to rhyming we must learn to understand such an exercise as the following:

Fri. S. . . . and Fri. V. . . . will you demonstrate what I am now going to describe. Fri. S. . . . will you make the gesture for Leo, and you, Frl. V. . . . the gesture for Aquarius; now, as I read this little poem, try to show it in eurythmy. In the case of the emphasized rhymes, the rhymes which fall on an accented beat, you, Fri. S.. . . must make the gesture for Leo. With the unemphasized rhymes, thus those which do not fall on the accented but on the unaccented beat, you, Frl. V. . . . must make the gesture of Aquarius. Make the movements standing still, choosing perhaps the vowel sounds, and only making the zodiacal gestures at the end of the lines so that we may really see their effect when they follow immediately after the rhyme.

Es rauschst das Bachlein -Ether Gestein... .

(You, Frl. V. . . . must hold the sound)

Ein Weidenbaum driiber gebogen,

Drauf sitzt des Miillers Büblein klein,

Im Schosse ein kleines Zitherlein,

Die Füsschen bespiilt von den Wogen.

Es kommt ein Mann des Wegs zu gehn,

Er bleibt so still, so schweigsam stehn

Sieht zu dem sinnigen Knaben;

Hatt' auch ein Büblein klein,

War auch so still und auch so fein.

Das liegt nun draussen begraben.

You see how the rhyme may be emphasized in this way by means of the zodiacal gestures. I am drawing your attention to such things so that you may be able to work out similar exercises for yourselves, thus gaining assurance and certainty in the development of eurythmic gestures.

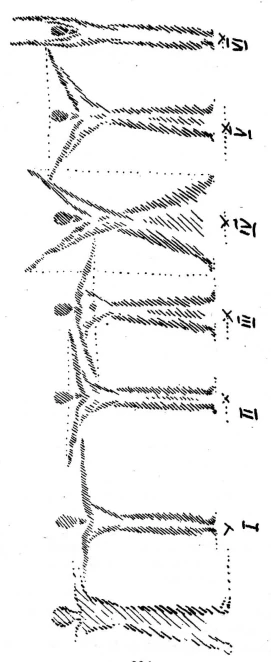

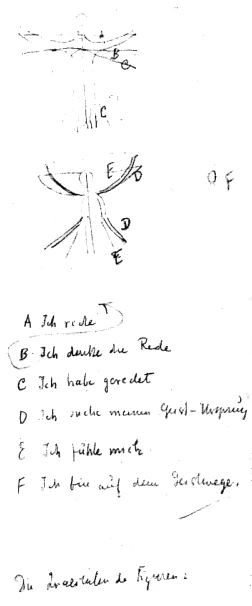

I will now ask a number of eurythmists to come forward and make various movements as I explain them: Number one must place the feet together, stretching the arms out so that they lie in a horizontal direction, on a level with the shoulders.

Number two must stand with the feet slightly apart, holding out the arms in such a way that the hands about correspond with the level of the larynx:

Now for number three: stand with your feet somewhat further apart, and hold the arms in such a way that, if a line were drawn from hand to hand, it would pass just below the heart.

Number four: stand with the feet still further apart, quite wide, holding the arms right up above the head. The hands must be held in such a way that they could be connected with the feet by means of a straight line.

Number five: stand with the feet in a similar position to number three, and now hold the arms in such a way that a line drawn from hand to hand would pass at the level of the top of the head.

Here (in the case of Number two) the line passes across the larynx; here (Number one) the line is quite horizontal; here (Number four) it is high up above the head; and here (Number five) it is just at head-level. Continue to hold all these gestures.

Number six: you must stand with the legs close together, with the arms held upwards in an absolutely vertical line: To these gestures we must add the following words:

Ich denke die Rede—I

Ich rede—II

Ich habe geredet—III

Ich suche mich im Geiste (meinen geistigen Ursprung)—IV

Ich fühle mich in mir—V

Ich bin auf dem geistigen Wege—VI

Ich bin auf dem Weg zum Geiste (zu mir).

I think speech I speak

I have spoken

I seek for myself in the Spirit

(my spiritual origin)

I feel myself within myself

I am on the spiritual path

I am on the way to the Spirit (to myself).

Approximately in this way. And now you must try to pass from one position to the next. Frl. V. . . . will you do this? Place yourself in front of each one in turn, and, as you take up each position, you must feel impelled to express the words that are said by means of the gesture being carried out by the eurythmist standing behind you. As Number one, you have to begin:

Ich denke die Rede

Passing on take up your place in front of Number two:

Ich rede

Ich habe geredet

Ich suche mich im Geiste

Ich fühle mich im mir

Ich bin auf dem Geistwege.

In this way we get the whole series of gestures.

Ich denke die Rede

Ich rede

Ich habe geredet

Ich suche mich im Geiste

Ich fühle mich in mir

Ich bin auf dem Wege zum Geiste (zur mir).

If, when teaching eurythmy to adults, a beginning is made with this very exercise, it will certainly help them to find their way into eurythmy easily and well.

These gestures, when carried out in this way one after the other, form an exercise which may be classed among those having a harmonizing and curative effect. Thus, when anyone is so much disturbed in his soul-life that this disturbance works itself out into his physical body, manifesting itself in all sorts of digestive troubles, then this exercise, taken in such a case as a curative exercise, may always be given with the greatest benefit.

And finally, my dear friends, I must once again impress upon your hearts the fact that really good eurythmy can only be achieved when there is the determination always to make a thorough and careful preparatory analysis, of anything which is to be interpreted by means of eurythmy. Every poem must be studied in the first place with a view to discovering which are the most fundamental sounds. If in a poem expressing the feeling of wonder, the wonder experienced by the poet, we find many a sounds, then we may be quite sure that this poem is well suited to eurythmy, for it is the sound a which expresses wonder. The poet himself has felt that a is specially related to the mood of wonder. And the eurythmist will be able to intensify the effect by laying stress on the movement corresponding to the sound a. In eurythmy it is even more important to concentrate on the sounds contained in a poem than on the actual sense-content of the words. For the sense-content is the prose element. The more a poem depends upon its sense-content, so much the less is it a poem; and the more the sound-content is brought out, the more a poem is dependent on sound, the nearer it approaches to true poetry.

As a eurythmist, then, one should not take one's start from the prose-content, but should enter so deeply into the nature of the sounds as to be able to say: When many a-sounds occur in a poem it is obvious that it is a poem based upon the mood of wonder and must be so expressed. This shows us the attitude we must have towards language as such. Further we must seek in poetry for those characteristics of language which we have already mentioned here,—what is concrete, for instance, what abstract, and other details of this kind. This means that one must first enter into the nature of a poem and study it according to the structure and formation of its language, only later trying to express it in eurythmy.

In eurythmy there is still another thing to bear in mind, and that is the way in which, in the eurythmy figures, I have tried to portray Movement, Feeling and Character.1See page 274. The Eurythmy Figures. This is another field of study for eurythmists. The movement must be felt as movement, and is depicted as such in the figures. As a eurythmist one lives in movement. We must, however,—more especially when a veil is floating around us, but also when we are not actually wearing one,—picture this veil as expressing the aura (see Eurythmy Figures). It is only when one bears this in mind that one can bring the necessary grace and beauty into the movements. Let us look at the eurythmy figure for I. The 1-sound itself lies in the movement; but that which can be added to the 1 as feeling, is shown by the fact that here, in the region of the arms, the aura is quite wide, becoming narrower as it hangs down. You must imagine that your arms reveal your feeling by means of the floating aura of the veil. The dress which here appears somewhat wider at the bottom must be studied in a similar way. This is how one must picture oneself. As a eurythmist, one should always feel oneself attired in dress and floating veil as I have indicated here in the figure.

Character also is of the greatest importance. When stretching out the arms one should actually feel that here (see figure) the muscles are stretched and taut. Everywhere where character is indicated by means of its corresponding colour there must be a tension of the muscles. This must also be shown by the eurythmist. And here again, for example, (see figure) you must use the legs in such a way that you really experience this muscular tension. The eurythmy figures are intended to show such things and have been designed accordingly.

When you have in this way made a study of each separate sound, your whole organism will be so sensitive to sound that you will feel: This whole poem is built up upon the mood of l, let us say, or upon the mood of b; and it will then be possible for you to create your interpretation of a poem out of the sounds themselves.

All these things must be very carefully borne in mind when it is a question of teaching eurythmy. In educational eurythmy it is naturally important to introduce such movements of the body as can work with moral benefit upon the soul-life, and serve to further the development of intellect and feeling.

In artistic eurythmy the essential thing is that the soul should gain the power of working through the medium of the body. Thus the movements of eurythmy, these gestures as they are shaped and formed, must be felt to be absolutely natural, indeed inevitable. One must feel that they could not be otherwise, that it is only by means of these very gestures that certain moods or artistic concepts can be expressed.

Yet another thing must be borne in mind, and that is the fact that the learning of eurythmy entails an actual trans-formation of the human organism. Any performance which reveals the slightest trace of struggle between body and soul must be looked upon as unfinished and imperfect. In a eurythmy performance the whole body must have become soul.

A programme is sometimes given—as you yourselves know—which has been prepared with unbelievable industry and is then shown for the first time. One can enjoy such a programme, where everything is fresh and spontaneous, where there is still a struggle with the form-running, and where on occasion the arms are not moved but thrown about, appearing so heavy as to be liable at any moment to fall to the ground. There is spontaneity in all this and it gives us a certain pleasure.

Then the time comes when the programme is taken on tour and given perhaps in some ‘two dozen' towns. (As a matter of fact, I believe this has never actually happened, but it might well happen.) The programme is, as I said, performed in about two dozen towns and the eurythmists return. Then,—because Frau Dr. Steiner has had no time to prepare a new programme,—this old programme, which we saw some six weeks ago in all its youthful spontaneity, is presented again. Now the pleasure is of a very different kind. Everything has become easy and fluent. One notices, too, that the eurythmists, because they have visited new towns and learned to know fresh conditions, are stimulated by the outer world and have gained a certain inner enthusiasm. All this has had its effect on the movements and they have become effortless and free. The performance is now sheer delight, and one can only exclaim: ‘Oh, if this programme could be performed fifty times more, how beautiful it would be then!'

We must have an understanding for these things. Every artist whose work is bound up with the stage knows the truth of what I have just said. A good actor would never think that he has mastered a role before he had played it some fifty times. With the fifty-first performance he might perhaps think that he could play the part, for then every-thing would have become second nature. We, too, must acquire this attitude of mind, my dear friends. We must develop such a love for anything which is to be shown in a performance that we simply cannot put it aside. Indeed no one but the onlooker may be permitted to find an often repeated item dull or tedious! It is in the sphere of art above all, that it is important to realize this; one must come back to a thing again and again. In a place where I once happened to be staying, I had the opportunity of seeing a play repeated fifty times. I went every evening to see this same play and allowed it to work upon me. By the fifth evening I did perhaps have a certain feeling of boredom, but by the fifty-first evening I was not in the least bored. Even though the performance, in a small provincial theatre, was very mediocre, so much could be learned from its very imperfection that this experience,—peculiar though it was,—could be of life-long benefit. As a matter of fact, I did not like the play in question; as a play it did not interest me at all. (It was Sudermann's Ehre.) I could not stand the play; nevertheless, I saw it performed fifty times by a some-what mediocre cast. My aim was to enter into all the details unconsciously, thus experiencing it purely with the astral body. I wished to take it right out of the realm of conscious perception and simply to live with it.

People must learn,—and now, when I am speaking about eurythmy, I will take the opportunity of mentioning it,—people must learn the value of rhythm, even in more complicated matters. We say the Lord's Prayer not fifty times only, but countless times, and we never find it tedious. Notice is seldom paid to the fact that such things are connected with experiences of the human organism, experiences which are apparently more or less immaterial and to which our Karma leads us at one time or another.

With this, my dear friends, we must bring this course of lectures to a close. From the way I have developed the subject, you will have realized that my first aim has been to show you that it is out of the feelings, out of the soul-life, that eurythmy must proceed. Eurythmic technique must be won out of a love for eurythmy, for in truth, everything must proceed out of love.

How much I myself love eurythmy, my dear friends, I have told you recently in the ‘News Sheet'.2S. page 260. I said then how earnestly I wish that the great devotion demanded of all those actively engaged in the work of eurythmy,—work which was begun by Frau Dr. Steiner, begun by our eurythmy artists here in Dornach and which has gradually won wider recognition and esteem,—how earnestly I wish that all this may be rightly appreciated; for it cannot be too highly prized in Anthroposophical circles. It is my hope that this course of lectures may have contributed something towards the furthernace of eurythmy in this respect, in that all of us who are gathered together here,—whether as eurythmists who already know the fundamentals of eurythmy, as beginners, or indeed as those merely interested in eurythmy, that all of us here will feel ourselves as the helpers and promoters of eurythmy, of this art which springs from no humble source, but has as its lofty origin, that cosmic knowledge which creates from out of the spirit. If we feel ourselves as the helpers of eurythmy, either in an active or in a more passive sense, then eurythmy will be able to fulfil the mission which it can and should fulfil in the general development of Anthroposophy.

When people will see in beauty the spirit working in human movement, then this will make some contribution to the whole attitude which humanity, through Anthroposophy, should take up towards the spirit.

Let us think of all the many things which have grown up out of anthroposophical soil, forming together one great whole; and then, inspired by the Anthroposophy in our hearts, let us build up and develop each separate activity as it should and will be developed if we prove ourselves worthy of the real aims of Anthroposophy. This course of eurythmy lectures may perhaps have done something towards this end.