Speech and Drama

GA 282

5 August 1924, Dornach

I. The Forming of Speech as Art

This course has a little history attached to it, and it is perhaps good that I should weave this little history into the introductory words that I propose to give today. For that is all we shall attempt in this first lecture—a general introduction to the whole subject. The proper work of the course will begin tomorrow and will be apportioned in the following way. I shall give the lectures; and then as far as demonstration is concerned, that will be taken by Frau Dr. Steiner. The course will thus be given by us both, working together.

The arrangement of the course will be, roughly speaking, as follows. Part I will be devoted to the Forming of Speech, and Part II to the Art of the Theatre—dramatic stagecraft, production and so on. Then, in Part III, we shall consider the art of the drama in relation to what it meets with in the world outside, whether in the way of simple enjoyment or of criticism and the like. We may call this third part: The Stage and the Rest of Mankind. We shall have to discuss together certain demands that our age makes upon the art of the drama, and see how we can enable it to take its right place in the life of man as it is lived today.

I said the course had a little history behind it. It began in the following way. A number of persons closely connected with the stage approached Frau Dr. Steiner and myself independently, in the conviction that anthroposophy, ready as one expects it to be to give new impulses today in every sphere of life—in religion, in art, in science—must also be able to furnish new impulses for the art of the drama. And that is most assuredly so. Several courses on speech have already been given here by Frau Dr. Steiner; and at one of them, where I also was contributing, I added some considerations that bore directly on the work of the stage. These had a stimulating effect on many of those who attended the course, some of whom have since been introducing new features into their work on the stage, that can be traced to suggestions or indications given by us. Groups of actors have made their appearance before the public as actors who acknowledge that, for them at least, the Goetheanum is a place where new impulses can be received.

And then there is also the fact that the art which has been among us since 1912, the art of eurhythmy, comes very near indeed to the art of the stage. This follows from the very conditions eurhythmy requires for its presentation. Dramatic art will, in fact, in future have to consider eurhythmy as something with which it is intimately connected.

This art of eurhythmy, when it was originally given by me, was at first thought of within quite narrow limits. I should perhaps not say ‘thought of’, for it was with eurhythmy as it is with everything within the Anthroposophical Movement that comes about in the right way: one responds to a demand of karma, and gives just so much as opportunity allows. No other way of working is possible in the Anthroposophical Movement. You will not find with us an inclination to plan ‘reforms’ or to put out some great ‘idea’ into the world. No, we take our guidance from karma. And at that time a need had arisen—it was in a quite small circle of people—to provide for some kind of vocation. It all came about in the most natural manner, but in a manner that was in absolute conformity with karma; and to begin with, what I gave went only so far as was necessary to meet this karma.

Then one could again see the working of karma in the fact that about two years later Frau Dr. Steiner, whose own domain was of course very closely affected, began to interest herself in the art of eurhythmy All that eurhythmy has since become is really due to her. Obviously therefore this present course as well, the impulse for which goes right back to the years 1913–14, must take its place in the Section for the Arts of Speech and Music, of which Frau Dr. Steiner is the leader.1The courses of study and training given at the Goetheanum were grouped by Dr. Steiner under various `Sections’, each with its Leader. For now, as a direct culmination of these events, the idea has arisen of doing something here for the development of the arts of speech and drama. Making a beginning, that is; for what we do would naturally only attain its full significance if the audience were limited to professional actors and those who, having the necessary qualifications, are hoping to become such. We should then probably have been a comparatively small circle; and we should have been able, working through the course in its three Parts (as I have explained is my intention), to carry our study far enough to allow of the participants forming themselves afterwards into a working group. They could then have gone out from Dornach as a touring company and proved the value, wherever they went, of the study we had carried through together here. For the deeper meaning of such things as I intend to put before you in this course will obviously only emerge when they are put into practice on the stage. This therefore would have been the normal outcome of a course of lectures on Speech and Drama.

That not all of you assembled here desire a course on this basis is perfectly evident. Nor would it be possible to carry it through with the present audience. Obviously, that is not feasible—although perhaps it would not, after all, be such a terrible disaster for the world if in some of our theatres the present actors could be replaced from here! But I see a few friends sitting in the audience of whom I know very well that they have no such ambition!

And so it turns out that there are two reasons why the course could not take on this orientation towards a practical end. For, in the first place, unfortunately neither those on whom it would have devolved to carry out the plan, nor we who were to give the impulse for it, have any money. Money is the very thing we are perpetually feeling the lack of. In itself the plan would have been perfectly possible, but there is no money for it; and unless it were properly financed, it could naturally not be put into effect. The only possibility would be that some of you who feel stimulated to do so should go ahead and undertake something at your own personal risk.

Secondly, such a keen interest was aroused in the course that one had to begin to consider who else might perhaps be allowed to attend. At first, we were rather strict; but the circle having been once broken into, all control goes to the winds—and that has most emphatically been our experience on this occasion.

Our course, then, will set out to present the art of the stage, with all that pertains to it, and we shall find that the art of the stage has to reach out, as it were, in many directions for whatever can contribute to its right development and orientation. Today, I want to speak in a general introductory way of what I have in mind as the essential content of our work together.

The first thing that calls for attention is that if speech is to come in any way into the service of art, it must itself be regarded as an art. This is not sufficiently realised today. In the matter of speech you will often find people adopting an attitude such as they adopt also, for example, to the writing of poetry. It would hardly occur to anyone who had not mastered the preliminaries of piano-playing to come into a company of people and sit down at the piano and play. There is, however, a tendency to imagine that anyone can write poetry, and that anyone can speak or recite. The fact is, the inadequacy and poverty of stage speaking as it is at present will never be rectified, nor will the general dissatisfaction that is felt on the matter among the performers themselves be dispelled, until we are ready to admit that there are necessary preliminaries to the art of speech just as much as there are to any performance in the sphere of music.

I was once present at an anthroposophical gathering which was arranged in connection with a course of lectures I had to give. It was a sort of ‘afternoon tea’ occasion, and something of an artistic programme was to be included. I do not want to enter here into a description of the whole affair, but there was one item on the programme of which I would like to tell you. (I myself had no share in the arrangements; these were made by a local committee.) The principal person concerned came up to me and I asked him about the programme. He said he was going to recite himself. I had then to call to my aid a technique that is often necessary in such circumstances, a technique that enables one to be absolutely horror-struck and not show it. It is a faculty that has to be learned, but I think on this occasion I succeeded pretty well, to begin with, in the exercise of this little artifice. I asked him then what he was going to recite. He said he would begin with a poem by the tutor of Frederick William IV, a poem about Kepler. I happened to know it—a beautiful poem, but terribly long, covering many pages. I said: ‘But won't it be rather long?’ He merely replied that he intended following it up with Goethe's Fairy Tale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily; and that if all went well, he would then go on to recite Goethe's poem Die Geheimnisse. I can assure you that with all the skill I could muster it was now far from easy to conceal my dismay.

Well, he began. The room was only of moderate size, but there were quite a number of people present. First one went out, then another, then another; and presently a group of people left the room together. Finally, one very kind-hearted lady was left sitting all alone in the middle of the room—his solitary listener! At this point the reciter said: ‘It will perhaps be rather too long.’ So ended the scene.

It is, as you see, not only outside the Anthroposophical Society but even within it that such a point of view in regard to speech may be met with. I have taken a grotesque example, but the same sort of thing is constantly occurring in milder form, and it is imperative that we make an end of it, if our performances in this domain are to find approval with those who understand art and are moved by genuine artistic feeling. There must be no doubt left in our minds that the forming of speech has to be an art, down to each single sound that is uttered, just as music has to be an art, down to each single note that is played.

Only when this is realised will any measure of satisfaction be possible; and, what is still more important, only then will the way open for style to come again into the arts of speech and drama. For the truth is, people have ceased troubling about style altogether in this domain; and no art is possible without style.

But now, if we are to speak together here of these things, the need inevitably arises that I should at the same time draw your attention to the way that speech and drama are related to the occult—the occult that is ever there behind. And that brings us to the question: Whence in man does speech really come? Where does it originate?

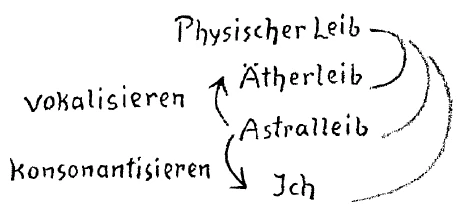

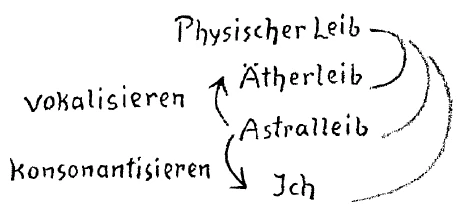

Speech proceeds, not directly from the I or ego of man, but from the astral organism. The animal has also its astral organism, but does not normally bring it to speech. How is this? The explanation lies in the fact that the members of the human being, and also of the animal, are not there merely on their own; each single member is interpenetrated by all the others, and its character modified accordingly.

It is never really quite correct to say: Man consists of physical body, etheric body, astral body and I; for the statement may easily give the impression that these members of the human being are quite distinct from one another, and that we are justified in forming a conception of man which places them side by side. Such a conception is, however, quite untrue. In waking consciousness, the several members interpenetrate. We ought rather to say: Man has not just a physical body as such (the physical body would look quite different if it simply followed its own laws), but a physical body that is modified by an etheric body and again by an astral body, and then again by an I or ego. In each single member, the three other members are present. And so, if we are considering the astral body, we must not forget that every other member of man's nature is also present in it. It is the same with the animal: in the astral body of the animal the physical body is present, and the etheric body too. But man has, in addition, the I, which also modifies the astral body; and it is from this astral body, modified by the I, that the impulse for speech proceeds. It is important to recognise this if we want to carry our study of the art of speech right into the single sounds. For, while in ordinary everyday speech the single sounds are formed in entire unconsciousness, the activity of forming them has to be lifted up into consciousness if speech is to be raised to the level of art.

How then did speech begin? Speech did not originate in the speaking we use in ordinary life, any more than writing originated in the writing of today. Compare with the latter the picture-writing of ancient Egypt; that will give you some idea of how writing first came about. And it is just as useless to look for the origin of speech in the ordinary talking of today, which contains all manner of acquired qualities—the conventional, the intellectual, and so on. No, speech has its source in the artistic life. And if we want in our study of speech to find our way through to what is truly artistic, we must at least have begun to perceive that speech originates in the artistic side of man's nature—not in the intellectual, not in man's life of knowledge, as knowledge is understood today.

Time was when men were simply incapable of speaking without rhythm, when they felt a need always, whenever they spoke, to speak in rhythm. And if a man were saying something to which he wanted to give point or emphasis, then he would attain this by the way he formed and shaped his language. Take a simple example. Suppose you wanted to say—speaking right out of the primeval impulses of speech—that someone keeps stumbling as he walks It would suffice to say: He stumbles over sticks. For there were certainly sticks of wood lying about in primeval times. There were also plenty of stones, and you could just as well say: He stumbles over stones. You would not, however, say either. You would say: He stumbles über Stock and Stein (over stick and stone). For, whether or no the words exactly describe what the speaker sees, we have in ‘stick and stone’ an inner artistic forming of speech. Or again, in order to make our statement more telling, we do not merely say that a ship is sinking together with the men in it. We add what is perhaps far from welcome on a ship; we add the mice. If we are really forming our speech out of what was the original impulse behind all speaking, we say: The ship is going down mit Mann and Maus (with man and mouse).2English parallels will readily occur to the reader, such as 'might and main', 'safe and sound', etc., and our use of 'stocks and stones' in another connection.

Today, the original impulse for speech is present in mankind only in the very smallest degree. There is ample reason for the fact. Unhappily, speech as an art has no place now in education.3The Waldorf School in Stuttgart, founded in 1919 by Emil Molt, was the first of the now numerous Rudolf Steiner Schools where the teaching and education are carried on in accordance with his indications. Dr. Steiner was a constant visitor to the school from the beginning, giving help and advice in every detail of management and method up to the time of his last illness in the winter of 1924-5. Our schools, and the schools of other nations too, have lost touch with art altogether; and that is why in our Waldorf School we have to make such a strong stand for the artistic in education.’ The schools of our time have been founded and established on science and learning—that is, on what counts as such in the present day, and it is inartistic. Yes, that is what has happened; this modern kind of science and learning has for a long time been steadily seeping down into the education given in our schools. Gradually, in the course of the last four or five centuries, these have been changing, until now, for anyone who enters one of them with artistic feeling, these schools of ours give the impression of something quite barbaric.

But if art is absent in our schools—and don't forget that the children have to speak in class; good speaking is part of the instruction given at school—if the artistic side of education is completely absent, it need not surprise us if art is lacking in grown men and women. There is, in fact, among mankind today a sad dearth of artistic feeling; one can therefore hardly expect to find recognition of the need to form speech artistically.

We do not often have it said to us: ‘You didn't say that beautifully’, but very often, ‘You are not speaking correctly’. The pedantic grammarian pulls us up, but it is seldom we are reproved for our speech on artistic grounds. It seems to be generally accepted as a matter of course that speech has no need of art.

Now, the astral body is mainly in the unconscious part of man's nature. But the artist in speech must learn to control what in ordinary speaking takes its course there unconsciously. In recent times people have begun to appreciate this. Hence the various methods that have been put forward—not only for singing, but also for recitation, declamation, etc. These methods, however, generally set to work in a very peculiar way.

Suppose you wanted to teach someone to plough, and never took any trouble to see what the plough was like, or the field, did not even stop to consider what the ploughing is for, but instead began enquiring: ‘If here is the person's arm, at what angle should he hold it at the elbow? What will be its natural position for ploughing?’ (How constantly one hears this word ‘natural’!) ‘And what movement should he be making with his leg while he holds his arm in this position?’ Suppose, that is, you were to take not the slightest interest in what has to be done to the field by the plough, but were merely to ask: ‘What method must I use to bring the pupil into a certain train of movements?’ It sounds absurd, but modern methods of speech training are of this very kind. No regard whatever is paid to the objective comprehension of what speech is.

If you want to teach a man to plough, the first thing will be to make sure that you yourself know how to handle a plough and can plough well and accurately; and then you will have to watch your pupil and see that he does not make mistakes. It is no different with speech. All these modern methods that are constructed in the most dilettante fashion (I mean these methods of breath technique, diaphragm technique, nasal resonance and the rest) omit to take into consideration what is, after all, the heart and core of the matter. They set out to instruct as though speech itself were not there at all! For they take their start, not from speech, but from anatomy.

What is important before all else is a thorough knowledge of the organism of speech, of the living structure of speech as such. This organism of speech has been produced, has come forth, out of man himself in the course of his evolution. Consequently, if rightly understood, it will not be found to contradict, in its inherent nature, the organisation of man as a whole. Where it seems to do so, we must look into the speech itself in detail to see where the fault lies; it will not be possible to put the matter right by means of methods that have as little to do with speech as gymnastics has to do with ploughing—unless a plough should ever be included among the gymnastic equipment, which up to now I have never known to be the case. Not that I should consider it stupid or ridiculous to include a plough in the apparatus of a gymnasium; it might perhaps be a very good idea. It has only, so far as I know, never yet been attempted.

The first thing to do then is to acquire a thorough knowledge of the speech organism, this speech organism of ours that has, in the course of mankind's evolution, broken loose, as it were, from the astral body, come straight forth from the ego-modified configuration of man's astral body. For that is where speech comes from.

We must, however, not omit to take into account that the astral body impinges downwards on the etheric body and upwards on the ego—that is, when man is awake; and in sleep we normally do not speak.

Consider first what happens through the fact that the astral body comes up against the etheric body. It meets there processes of which man knows very little in ordinary life. For what are the functions of the ether-body? The ether-body receives the nourishment which is taken in by the mouth, and gradually transforms it to suit the needs of the human organism—or rather, I should say, to meet its need of the force contained in the nourishment. Then again it is the etheric organism that looks after growth, from childhood upwards until man is full grown. And the ether-body has also a share in the activities of the soul; it takes care, for instance, of memory. Man has, however, very little conscious knowledge of the various functions discharged by the ether- body. He knows their results. He knows, for example, when he is hungry; but he can scarcely be said to know how this condition of hunger is brought about. The activity of the ether-body remains largely unconscious.

Now it is the production of the vowel element in speech that takes place between astral body and ether body. When the impulse of speech passes over from the astral body, where it originates, to the ether body, we have the vowel. The vowel is thus something which comes into operation -deep within the inner being of man; it is formed more unconsciously than is speech in general. In the vowel sounds we are dealing with intensely intimate aspects of speech; what comes to expression in them is something that belongs to the very essence of man's being. This is then the result when the speech impetus impinges on the ether-body: it gives rise to the vowel element in speech.

In the other direction, the astral body impinges on the I, the ego. The I, in the form in which we have it in Earthman, is something everyone knows and recognises. For it is by means of the I that we have our sense perceptions. We owe it also essentially to the I that we are able to think. All conscious activity belongs in the sphere of the I or ego. What goes on in speech, however, since there the astral body is also concerned, cannot be performed entirely consciously, like some fully conscious activity of will. A fragment of consciousness does, nevertheless, definitely enter into the consonantal element in ordinary speech; for the speaking of consonants takes place between astral body and ego.

We have thus traced back to their source the forming of consonants and the forming of vowels. But we can go further. We can ask: What is it in the totality of man's nature that speech brings to revelation? We shall be able to answer this question when we have first dealt with the further question: How was it with the primeval speech of man? What was speech like in its beginnings?

The speech of primitive man was verily a wonderful thing. Apart from the fact that man felt instinctively obliged from the first to speak in rhythm and in measure, even to speak in assonance and alliteration—apart from this, in those early times, man felt in speech and thought in speech.

Looking first into his life of feeling, we find it was not like ours today. In comparison with it, our feelings tend to remain in the abstract. Primeval man, in the very moment of feeling, were it even a feeling of the most intimate kind, would at once express it in speech. He would not have found it possible, for instance, to have a tender feeling for a little child without being prompted in his soul to bring that feeling to expression in the form of his speech. Merely to say: ‘I love him tenderly’, would have had no meaning for him; what would have had meaning would have been to say perhaps: ‘I love this little child so very ei-ei-ei!’[5] There was always the need to permeate one's whole feeling with artistically formed speech.

Neither in those olden times did men have abstract thoughts as we do today. Abstract thoughts without speech were unknown. As soon as man thought something, the thought immediately became in him word and sentence. He spoke it inwardly. It is therefore not surprising that at the beginning of the Gospel of St. John we do not find it said: ‘In the beginning was the Thought’, but : ‘In the beginning was the Word’—the verbum, the Word. today we think within, thinking our abstract thoughts; primeval man spoke within, talked within.

Such then was the character of primeval speech. It contained feeling within it, and thought. It was, so to say, the treasure-casket in man for feeling and thought. Thought has now shifted, it has slipped up more into the ego; speech has remained in the astral body; feeling has slid down into the ether body.

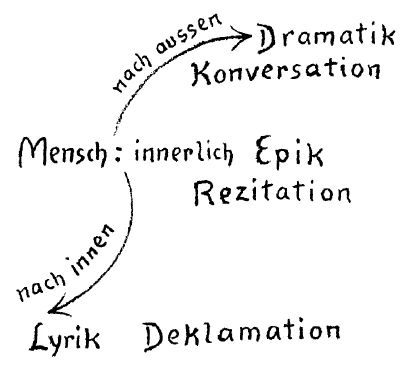

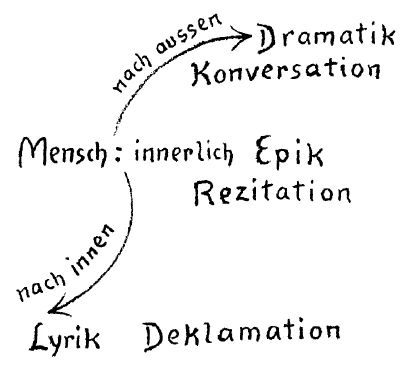

The poetry of primeval times was one, was single; it expressed in speech what man could feel and think about things The original poetry was one. When, later on, speech threw back feeling inwards, into man's inner nature, that gave rise to the lyric mood of speech. The kind of poetry that has remained most of all like the primeval, the kind of poetry that, more than any other, is inherent in speech itself is the epic. It is, in fact, impossible to speak epic poetry without first reviving something of the original primal feeling in regard to speech. Finally, drama drives speech outwards and stands, in so far as Earth-man is concerned, in relation with the external world.

The artist who is taking part in drama, unless of course he is speaking a monologue, confronts another person. And this fact, that he is face to face with another person, enters into his speaking just as surely as what he experiences in himself.

The artist who has to speak a lyric is not confronting another person. He faces himself alone. His speech must accordingly be so formed that it may become the pure expression of his inner being. The lyric of today can therefore not be spoken in any other way than by letting even the consonants lean over a little in the direction of vowels. (We shall go into this in more detail later.) To speak lyrical poetry aright, you need to know that every consonant carries in it a vowel nuance. L, for example, carries in it an i (ee), which you can see for yourselves from the fact that in many languages where at some time in their development an I occurs in a certain word, in other forms of that word we find an i.4For example, in German-speaking countries, a boy named Hans may be called ' for short ' either Hansi or Hansl. As a matter of fact, all consonants have within them something of the quality of a vowel. And for speaking lyrics it is of the first importance that we should learn to perceive the vowel in each single consonant.

The epic requires a different feeling. (All that I am saying in this connection has reference to recitation or declamation before an audience.) The speaker must feel: When I come to a vowel, I am coming near to man himself; but directly I come to a consonant, it is things I am catching at, things that are outside. If the artist once has this feeling, then it will be possible for the epic to be truly present in his speaking. Epic has to do, not with man's inner life alone, but with the inner life and an imagined outer object. For the theme of the epic is not there; it is only imagined. If we are relating something, it must belong to the past, or in any case cannot be there in front of us; otherwise, there would be no occasion to relate it. The speaker of epic is thus concerned with the human being and the object or theme that exists only in thought.

For the speaker of drama, the ‘object’ of his speaking is present in its full reality, the person he addresses is standing there in front of him.

There then you have the distinguishing characteristics of lyric, epic and drama. They need to be well and carefully noted. I have already in past years spoken of them here and there from different points of view, and have sought to evolve a suitable terminology for distinguishing the different ways of speaking them. What I have given on those earlier occasions—I mean it to be experienced, I mean it to be felt. You must have a clear and accurate feeling for what each kind of poetry demands. Thus, you should feel that to speak lyrical poetry means to speak right out of one's inner being.

The inner being of man is here revealing itself. When man's soul within him is so powerfully affected that it ‘must out’—and this is how it is with the lyric—then what was, to begin with, mere feeling, passes over into a calling aloud; and we have, from the point of view of speech, declamation. One domain, then, of the art of speech is declamation, and it is especially adapted for lyrical poetry. The lyrical element is present of course in every form of poetry; while we are speaking epic or drama, we can often find ourselves in the situation of having to make the transition here and there to the lyrical.

With the speaker of epic, the essential point is that he has before him an object that is not seen but thought, and by means of the magic that lies in his speech he is continually ‘citing’ this object. The artist of the epic is pre-eminently a ‘re-citer’. So here we have recitation. The speaker of the lyric expresses himself, reveals himself; he is a declaimer. The speaker who cites his object, making it present to his audience by the magic of his speech—he is a reciter.

And now in this course of lectures we have opportunity to go further and complete our classification. We come then to the speaker who has before him, not his imagined object that he cites, but present before him in bodily form the object to whom he speaks, with whom he is conversing. And so we reach the third form of speech: conversation.

It is through these three kinds of speech-formation that speaking becomes an art. The last is the one that is most misunderstood. Conversation, as we know all too well, has been dragged right away from the realm of art, and today you will find persons looked up to as past masters in conversation who are less at home in art than they are—shall I say—in diplomacy, or perhaps in the ‘afternoon-tea’ attitude to life. The feeling that conversation is a thing capable of highly artistic development has been completely lost.

Sometimes of course acting ceases to be conversation and becomes monologue. When this happens, drama reaches over into the other domains, into declamation and recitation.

To draw distinctions in this way between different forms of poetry may perhaps seem a little pedantic, but it will help to show that we do really have to create for the teaching of speech something similar to what we have, for example, in the teaching of music. When, for instance, a dialogue is to be put on the stage, it will be necessary to form that dialogue in a way that is right and appropriate to it as ‘conversation’.

I would like now to show you how within speech itself, if we see it truly for what it is, the need for artistic forming emerges. We use in our speaking some thirty-two sounds. Suppose you had learned the sounds, but were not yet able to put them together in words. If you were then to take up Goethe's Faust, the whole book would consist for you of just these thirty-two sounds. For it contains nothing more! And yet, in their combination, these thirty-two sounds make Goethe's Faust.

A great deal is implied in this statement. We have simply these thirty-two sounds; and through the forming and shaping of them, sound by sound, the whole measureless wealth of speech is called into being. But the forming is already there within the sounds themselves, within this whole system of sounds. Let us take an example.

We speak the sound a (ah). What is this sound? A is released from the soul, when the soul is overflowing with wonder. That is how it was to begin with. Wonder, astonishment, liberated from the soul the sound a. Every word that has the sound a has originated in a desire to express wonder; take any word you will, you will never be altogether out, nor need you ever be afraid of being dilettante, if you assume this Take, for instance, the word Band (a band or ribbon). In some way it happened that what the man of an earlier time called Band filled him with wonder, and that is why he brought the a sound into the word. (That the same thing has in another language quite a different name is of no consequence. It means only that the people who spoke that language felt differently related to the object.) Whenever man is particularly astonished, then if he has still some understanding of what it is to be thus filled with wonder (as was the case when language began to be formed), he will bring that wonder or astonishment to expression by means of the sound a. One has only to understand where wonder is in place. You can, for instance, marvel at someone's luxurious Haarwuchs (growth of hair) You can also marvel at the Kahlkopf (bald head) of someone who has lost his Haar. Or again, you can be astounded at the effect of a Haarwasser (hair lotion) which makes the hair grow again. In fact, everything connected with hair can evoke profound admiration and astonishment—so much so that we do not simply write Har, we write the a twice—Haar!

Wherever you meet the sound a, look for the starting- point of the word in an experience of wonder, and you will be carried back to the early days of evolution, when man was first shaping and forming his words. And this forming of words was an activity that worked with far greater power than present-day theories would lead us to suppose.

But now, what does this mean? It means that when a man is filled with wonder at some object or event, he gives himself up to that object or event, he lets himself go. For how is the sound a made? What does it consist in? A requires the whole organism of speech to be opened wide, beginning from the mouth. Man lets his astral body flow out. When he says a, he is really on the point of falling asleep. Only, he stops himself in time. But how often will the feeling of fatigue find expression at once in the sound a! Whenever we utter a, we are letting our astral body out, or beginning to do so. The act of opening out wide—that is what you have in a.

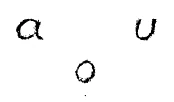

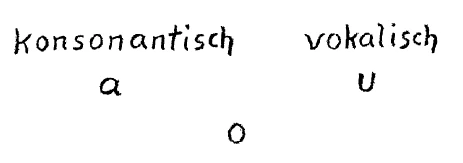

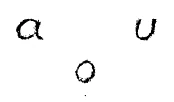

The absolute opposite of a is u (oo). When you say u, then beginning from the mouth you contract the speech organs, wherever possible, before you let the sound go through. The whole speech organism is more closed with u than with any other vowel sound. There then you have the two contrasting opposites: a u. Between a and u lies o. O actually includes within it, in rightly formed speech, the processes of a and the processes of u; o holds together in a kind of harmony the processes of opening out and the processes of closing up.

| a | o | |

| u |

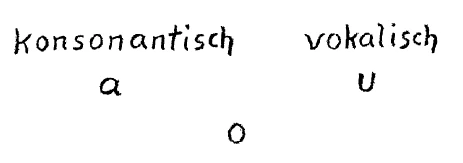

U signifies that we are in process of waking up, that we are becoming continually more awake than we were. When you say u, it shows that you are feeling moved to wake up in respect of some object that you perceive. When the owl makes himself heard at night, you instinctively exclaim: ‘Uhu!’5The commoner German word for owl is Eule, but Uhu, the specific name for the eagle-owl, is also used. You could not find stronger expression for the desire to wake up. The owl makes you want to wake up and be alive to the fact of its presence. And if someone were to fling a little sand at you—we don't of course have sand on our desks now, we use blotting paper—but suppose you were being pelted with sand, then, if you were to give way to your feelings without restraint, you would say ‘uff’. For it is the same whether something or other wakes you up, or you yourself are wanting to wake up. In either case u comes out. The astral is here uniting itself more closely with the etheric and physical bodies. The a is thus more consonantal and the u more vocalic

| Consonantal | Vocalic | |

| a | o | |

| u |

In some of the German dialects, one can often not discern whether people are saying a or r, for the r becomes with them vocalic and the a consonantal. In the Styrian dialect, for example, it is impossible to know whether someone is saying ‘Bur’ or ‘Bua’.

All the other vowels lie between a and u. Roughly speaking, the o is in the middle, but not quite; it occupies the same position between a and u as in music the fourth does in the octave.

Suppose now we want to express what is contained in O. In O we have the confluence of A and U; it is where waking up and falling asleep meet. O is thus the moment either of falling asleep or of awaking. When the Oriental teacher wanted his pupils to be neither asleep nor awake, but to make for that boundary between sleeping and waking where so much can be experienced, he would direct them to speak the syllable OM. In this way he led them to the life that is between waking and sleeping.

For, anyone who keeps repeating continually the syllable OM will experience what it means to be between the condition of being awake and the condition of being asleep. A teaching like this comes from a time when the speech organism was still understood.

And now let us see how it was when a teacher in the Mysteries wanted to take his pupils further. He would say to himself: The O arises through the U wanting to go to the A and the A at the same time wanting to go to the U. So, after I have taught the pupil how to stand between sleeping and waking in the OM, if I want now to lead him on a step further, then instead of getting him to speak the 0 straight out, I must let the 0 arise in him through his speaking AOUM. Instead of OM, he is now to say AOUM. In this way the pupil creates the OM, brings it to being. He has reached a higher stage. OM with the O separated into A and U gives the required stillness to the more advanced pupil. Whereas the less advanced pupil has to be taken straight to the boundary condition between sleep and waking, the more advanced has to pass from A (falling asleep) to U (waking up), building the transition for himself. Being then between the two, he has within him the moment of experience that holds both.

If we are able to feel how such modes of instruction came about, we can have some idea of what it means to say that in olden times it was by way of art that man came to an instinctive apprehension of the nature of speech. For down into the time of the ancient Greeks, men still had knowledge of how every activity and experience had its place in the world, where it intrinsically belonged.

Think of the Greek gymnastics,—those marvellous gymnastics that were really a complete language in themselves! What are they? How did they evolve? To begin with, there was the realisation that the will lives in the limbs. And the very first thing the will does is to bring man into connection with the earth, so that a relationship of force develops between man's limbs and the earth, and you have: Running In running, man is in connection with the earth. If he now goes a little way into himself, and to the dynamics into which running brings him and the mechanics that establishes a balance between him and the earth's gravitation, adds an inner dynamic, then he goes over into: Leaping. For in leaping we have to develop a mechanics in the legs themselves.

And now suppose to this mechanics that has been developed in the legs, man adds a mechanics that is brought about, not this time merely by letting the earth be active and establishing a balance with it, but by coming also to a state of balance in the horizontal,—the balance already established being in the vertical. Then you have: Wrestling.

Running

Leaping

Wrestling.

In Running, you have Man and Earth; in Leaping, Man and Earth, but with a variation in the part played by man; in Wrestling, Man and the other object.

If now you bring the object still more closely to man, if you give it into his hand, then you have: Throwing the Discus. Observe the progression in dynamics And if then to the dynamics of the heavy body (which is what you have in discus-throwing), you add also the dynamics of direction, you have: Throwing the Spear.

Running

Leaping

Wrestling

Discus-throwing

Spear-throwing.

Such then are these five main exercises of Greek gymnastics; and they are perfectly adapted to the conditions of the cosmos. That was the feeling the Greeks had about a gymnastics that revealed the human being in his entirety.

But men had the very same feeling in those earlier times about the revelation of the human being in speech. Mankind has changed since then; consequently, the use and handling of speech has inevitably also changed.

In the Seventh Scene of my first Mystery Play, where Maria appears with Philia, Astrid and Luna, I have made a first attempt to use language entirely and purely in the way that is right for our time and civilisation. Thought, which is generally lifted out of speech, abstracted from it, is there brought down again into speech.

We will accordingly take tomorrow part of this scene for demonstration, and so make a beginning with the practical side of our work. Frau Dr. Steiner will read from the scene; and then, following on today’s introductory remarks, we will proceed with the First Part of the course—the study of the Forming of Speech.

1. Die Sprachgestaltung als Kunst

Dieser Kursus hat eine kleine Geschichte, und es ist vielleicht notwendig, daß ich diese kleine Geschichte in die Einleitung, die ich zu sprechen gedenke, hineinverwebe, schon aus dem Grunde, weil heute nur eine allgemeine Einleitung von mir gegeben werden soll. Es wird dann mit der eigentlichen Gliederung des Kursus morgen begonnen werden. Diese Gliederung des Kursus wird so sein, daß die Auseinandersetzungen über Sprachgestaltung und dramatische Kunst von mir gegeben werden, und der Teil, der sich mit der eigentlichen Sprachgestaltung zu befassen hat, von Frau Dr. Steiner gegeben wird, so daß also der Kursus von uns beiden in Gemeinsamkeit zu halten sein wird.

Die Gliederung des Kursus soll ungefähr so sein, daß er in seinem ersten Teil die eigentliche Sprachgestaltung umfassen wird, in seinem zweiten Teil die Bühnenkunst, also das Dramatisch-Bühnenmäßige, Regiekunst und Bühnenkunst überhaupt. In seinem dritten Teil soll er auf das Thema kommen: Die Schauspielkunst und alles dasjenige, was vor der Schauspielkunst, sei es bloß genießend, sei es kritisierend und dergleichen, steht, ich möchte sagen: die Schauspielkunst und die übrige Menschheit. Das soll dann der dritte Teil sein.

Es wird sich dann besprechen lassen, wie unsere Zeit gewisse Forderungen enthält für die Schauspielkunst, und wie die Schauspielkunst hineingestellt werden soll in die Zeit gegenüber der Art und Weise, wie überhaupt heute die Menschheit lebt.

Ich sagte, der Kursus hat eine kleine Geschichte. Er ging davon aus, daß zu Frau Dr. Steiner und mir zunächst einzelne Persönlichkeiten kamen, welche das Bedürfnis hatten, aus ihrem Drinnenstehen im Bühnenmäßigen an die Anthroposophie heranzukommen in dem Glauben, daß, weil ja Anthroposophie heute dasjenige sein soll, das nach allen Seiten hin Anregungen gibt, nach der religiösen, der künstlerischen, wissenschaftlichen und so weiter - auch nach der künstlerisch-dramatischen Seite Anregungen gegeben werden sollen oder können.

Das kann ja durchaus der Fall sein, denn es gingen die verschiedenen Kurse voraus, die Frau Dr. Steiner für Sprachgestaltung gegeben hat. Es ging auch jetzt ein Kursus von Frau Dr. Steiner über Sprachgestaltung voraus, dem ich dazumal schon einiges hinzufügen durfte, was sich auf die Bühne selbst bezieht, der hier stattfand. Es ging voraus, daß von diesem Kursus dann allerlei Anregungen ausgegangen sind, und daß wiederum auf der anderen Seite Persönlichkeiten, die im Bühnenleben drinnenstanden, das oder jenes, was bisher als Anregung gegeben worden ist von unserer Seite her, schon vor die Öffentlichkeit hingestellt haben. Einzelne Gruppen von Persönlichkeiten traten ja in der Welt bühnenmäßig auf mit der Anerkennung zunächst für sie selbst, daß von hier aus gewisse Anregungen ausgehen können.

Dazu kommt, daß diejenige Kunst, die unter uns steht seit 1912, die eurythmische Kunst, nahe, möglichst nahe an das heutige Bühnenmäßige angrenzt. Und daß diese eurythmische Kunst in der Zukunft ganz mit dem Bühnenmäßigen eins werden muß, das geht schon aus der äußerlichen Art, wie sie vorgebracht werden muß, so hervor, daß einfach die Schauspielkunst das Eurythmische als etwas zu ihr Gehöriges in der Zukunft wird zu betrachten haben. Dieses Eurythmische war ja zunächst, als es von mir gegeben worden ist, im allerkleinsten Rahmen gedacht, vielleicht überhaupt nicht gedacht, könnte ich sagen, denn es lag die Sache 1912 so, wie immer die Dinge liegen, wenn in der richtigen Art innerhalb der anthroposophischen Bewegung gearbeitet wird: man nimmt dasjenige, was Karma fordert, auf, und gibt so viel, als gerade die Gelegenheit dazu da ist. Das ist in der anthroposophischen Bewegung nicht anders möglich. In der anthroposophischen Bewegung hat man nicht eine Tendenz, Reformgedanken zu haben, man hat nicht die Tendenz, eine Idee in die Welt zu setzen, sondern man hat das Karma vor sich. Und dazumal war es so, daß im allerengsten Kreise das Bedürfnis entstand, sozusagen eine Art Beruf zu bilden. Es war auf die naturgemäßeste, aber auch karmagemäßeste Weise. Und da tat ich zunächst so viel, als geradenotwendig war, um diesem Karma entgegenzukommen.

Dann wiederum war es ebenso karmisch, daß etwa zwei Jahre danach Frau Dr. Steiner, deren Domäne das selbstverständlich innig berührte, sich der eurythmischen Kunst annahm. Und alles, was dann daraus geworden ist, ist ja durch sie eigentlich erst geworden. So daß es also ganz selbstverständlich ist, daß auch dieser Kursus jetzt, der unmittelbar in diesen Anregungen auf das Jahr 1913, 1914 zurückgeht, sich hineinstellt in die Sektion für redende Künste, deren Leiter Frau Dr. Steiner ist.

Nun hat sich also aus all jenen Vorbedingungen heraus diese Idee gebildet, hier etwas zu tun für Sprachgestaltung und dramatische Kunst. Ich kann nur sagen, zunächst etwas zu tun, Ihren vollen Sinn hätte sie natürlich nur dann bekommen, wenn ausschließlich Berufsschauspieler oder solche, die aus genügenden Vorbedingungen heraus das werden wollen, hier zusammengekommen wären, wahrscheinlich in einem nicht sehr großen Kreise, und so weit gearbeitet worden wäre auch nach dieser dreifachen Gliederung, die ich ja für den Kursus beibehalten möchte, aber eben gearbeitet worden wäre so weit, daß dann die Teilnehmer eine Gruppe gebildet hätten, die nun als Schauspieler hinauszögen, eine Wandertruppe, und die an verschiedenen Orten dasjenige verwerteten, was hier gepflegt worden ist. Denn solche Dinge wie diejenigen, die vorgebracht werden sollen, haben eben ihren tieferen Sinn erst dann, wenn sie auch wirklich vor die Welt hingestellt werden. Also das war im Grunde genommen der dutch die Sache selbst gegebene Sinn.

Nun, daß Sie alle das nicht wollen, und daß es nicht möglich ist, mit diesem Auditorium das auszuführen, ist auch wohl wieder ohne weiteres klar. Ich glaube nicht, daß sich das tun ließe, obwohl es vielleicht nicht einmal so furchtbar schlimm wäre für die Welt, wenn die bestehenden Theaterpersonalien ersetzt würden in dieser Weise; aber einige wenige von denen, die ich hier sitzen sehe, von denen weiß ich, daß sie diese Absicht nicht haben!

Es ist aber so gekommen, daß aus zwei Gründen die Sache nicht diese ins Praktische gerichtete Orientierung annehmen konnte: erstens, weil weder diejenigen, die es tun sollten, noch wir, die eine Anregung dazu geben sollten, Geld hatten; das ist ja dasjenige, was bei uns am allermeisten immer fehlt. An sich wäre die Sache schon gegangen, aber es ist kein Geld dazu da, denn mit etwas, was nicht ordentlich fundiert ist, kann ja die Sache natürlich nicht gemacht werden; da kann es nur dann auf eigenes Risiko derjenigen gemacht werden, welche die Anregung bekommen.

Dann erhob sich auf der anderen Seite ein so lebhaftes Interesse gerade für diesen Kursus, daß man nun anfangen mußte, die Frage zu stellen: Wer kann nun außer den Berufsschauspielern oder auf die Schauspielkunst hin arbeitenden Persönlichkeiten noch dazu kommen? Da war man zunächst etwas rigoros; aber der Kreis war einmal durchbrochen, und dann hat es kein Ende mehr. Diese Erfahrung haben wir insbesondere diesmal gemacht.

So also wird der Kursus im wesentlichen dasjenige sein, was den Inhalt der Bühnenkunst darzustellen hat, insoferne diese Bühnenkunst wirklich allseitig nach ihren Hilfsmitteln und nach ihrer Orientierung ausschaut. Und so, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, möchte ich heute einleitungsweise im allgemeinen über dasjenige sprechen, was eigentlich Inhalt des Kursus werden soll.

Es handelt sich zunächst darum, daß Sprechen sehr häufig nicht so weit in bezug auf das Künstlerische durchschaut wird, wie es notwendig ist für denjenigen, der das Sprechen in irgendeiner Weise in den Dienst des Künstlerischen zu stellen hat. Man kann, wenn es sich um Sprechen handelt, fast dieselbe Erfahrung machen, die man in bezug auf das Dichten und noch einige andere Dinge macht. Es wird kaum leicht einem Menschen einfallen, ohne irgendwie die Vorbedingungen dazu überwunden zu haben, sich ans Klavier setzen zu wollen und zu spielen. Aber es besteht schon die allgemeine Tendenz, daß Dichten jeder kann, und daß auch Sprechen jeder kann. Dennoch werden die Unzulänglichkeiten, die auf diesem Gebiete herrschen, nicht eher behoben werden, und die allgemeine Unbefriedigtheit, die heute bei den Ausführenden besteht, wird ebensowenig behoben werden, wenn nicht die allgemeine Anschauung durchgreift, daß Vorbedingungen zum Sprechen ebenso notwendig sind wie Vorbedingungen zum musikalisch-künstlerischen Wirken.

Ich kam einmal zu einer anthroposophischen Versammlung, die gelegentlich eines Kursus veranstaltet wurde, einer Art Nachmittagstee; da sollten auch künstlerische Produktionen stattfinden. Ich will über die übrigen nicht sprechen, aber über eine doch. Ich hatte gar keinen Anteil am Programm; das hatte das Ortskomitee. Und da trat mir der hauptsächlichste Veranstalter eigentlich entgegen, und ich erkundigte mich nach dem Programm. Da sagte er, daß er nun selber rezitieren werde. Ich habe da die Technik anwenden müssen, die ja überhaupt in solchen Dingen manchmal notwendig ist, bis ins Innerste zu erschrecken und es nicht zu zeigen. Das muß man auch erst lernen, aber ich glaube, es ist mir dazumal zunächst gelungen, dieses Stückchen. Dann aber fragte ich, was er denn nun rezitieren wollte. Da sagte er mir, zuerst ein Gedicht, das herrührt von dem Erzieher Friedrich Wilhelms IV., das auf Kepler ist. Ich kannte das Gedicht zufällig, es ist ein wunderschönes Gedicht, aber furchtbar lang, mehrere Druckseiten lang. Ich sagte: Das wird aber etwas lang sein. Da sagte er, er wollte das nicht allein rezitieren, sondern er wollte gleich darauf folgen lassen noch das Goethesche «Märchen von der grünen Schlange und der schönen Lilie», und dann, wenn es noch geht, meinte er, Goethes «Geheimnisse». Und nun konnte ich tatsächlich den Schreck mit aller Technik nicht mehr so leicht zurückhalten!

Nun begann er zunächst mit dem Gedichte. Es war allerdings ein mäßig großer Raum, aber immerhin, es war eine Anzahl von Menschen darinnen. - Der erste ging heraus, der zweite ging heraus, der dritte wurde eine Gruppe, und zuletzt stand eine sehr gutmütige Dame mitten drinnen allein als Zuhörerin. Der Rezitator sagte nun: Es wird vielleicht etwas zu lang sein. — Damit endete die Szene.

Es bestehen solche Anschauungen nicht bloß außerhalb der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft, sondern auch zuweilen innerhalb der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft. Nun, diese Dinge, die man da charakterisieren kann, wenn man solche Grotesken erzählt, die aber in ihren leisen Gestaltungen doch vielfach vorliegen, müssen natürlich, wenn Befriedigung eintreten soll auf diesem Gebiete für denjenigen, der künstlerische Auffassung und künstlerischen Impetus hat, gründlich überwunden werden. Und vor allen Dingen muß gründlich verstanden werden, wie die Sprachgestaltung wirklich bis zu dem Laut hin Kunst sein muß für den Sprecher, geradeso wie das Musikalische bis zu dem Ton hin Kunst sein muß.

Erst wenn dieses wirklich durchschaut wird, dann wird einige Befriedigung, vor allen Dingen auch einiges von dem eintreten, was bewirken kann, daß wiederum Stil in die redenden Künste hineinkommt, in die redenden Künste, die ja den Stil gründlich beseitigt haben. Keine Kunst ist möglich ohne Stil.

Nun, hier, möchte ich sagen, geziemt es sich, wenn diese Dinge besprochen werden, zu gleicher Zeit immer darauf aufmerksam zu machen, wie sie sich verhalten mit Bezug auf das okkult hinter den Dingen Steckende. Und da entsteht denn die Frage: Wovon im Menschen geht eigentlich das Sprechen aus?

Das Sprechen geht nämlich nicht unmittelbar vom Ich aus, sondern das Sprechen geht eigentlich vom astralischen Organismus aus. Das Tier hat auch den astralischen Organismus, bringt es aber normalerweise nicht zum Sprechen. Das ist aus dem Grunde, weil alle Glieder der menschlichen Wesenheit, der tierischen Wesenheit, nicht nur für sich da sind, sondern jedes einzelne von allen anderen durchdrungen und dadurch in seiner Wesenheit modifiziert wird.

Es ist niemals in vollem Sinne des Wortes richtig, zu sagen, der Mensch besteht aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich, denn man bekommt da leicht den Gedanken, diese Glieder der menschlichen Natur seien nebeneinander, und es sei eine Auffassung möglich, welche diese Glieder nebeneinander stellt. Sie stehen nicht nebeneinander. Sie durchdringen sich im wachen Bewußtsein. Und so muß man sagen: Der Mensch hat nicht nur einen physischen Leib der würde ganz anders aussehen, wenn er nur seinen eigenen Gesetzen folgte -, sondern der Mensch hat einen physischen Leib, der vom Ätherleib, vom astralischen Leib, vom Ich modifiziert wird. - In jedem einzelnen Gliede der menschlichen Natur stecken auch die drei übrigen darin. So steckt auch im astralischen Leib jedes andere Glied der menschlichen Natur.

Nun, das hat ja auch das Tier: der physische Leib steckt im astralischen Leib des Tierischen, der Ätherleib steckt im astralischen Leib des Tierischen, aber das Ich modifiziert lediglich beim Menschen den astralischen Leib. Und von diesem astralischen Leib, der von dem Ich modifiziert wird, geht der Impuls des Sprechens aus.

Das ist es gerade, was berücksichtigt werden muß, wenn man künstlerisch in der Sprachgestaltung bis zum Laut kommen will, denn der Laut wird im gewöhnlichen alltäglichen Sprechen vollständig im Unbewußten geformt. Aber dieses Unbewußte muß in einer gewissen Weise ins Bewußtsein heraufgehoben werden, wenn das Sprechen von dem Nichtkünstlerischen in das Künstlerische gehoben werden soll.

Bedenken wir dabei nur das eine. Von demjenigen Sprechen, das wir heute im gewöhnlichen Leben pflegen, ist das Sprechen überhaupt nicht ausgegangen, gerade so wenig wie von unserer Schrift das Schreiben der Menschen ausgegangen ist. Vergleichen Sie die alte ägyptische Bilderschrift, so haben Sie noch eine Vorstellung, wovon das Schreiben ausgegangen ist. Und ebenso ist das Reden nicht von dem heutigen Reden ausgegangen, das alles mögliche in sich enthält, Konventionelles, Erkenntnismäßiges und so weiter, sondern es ist das Sprechen von dem ausgegangen, was künstlerisch im Menschen lebt. Will man daher das Künstlerische durchschauen, dann muß man schon wenigstens eine Empfindung dafür haben, daß die Sprache von menschlicher Künstlerschaft, nicht von menschlicher Zweckmäßigkeit, Wissenschaftlichkeit ausgegangen ist.

Es gab Zeiten in der Erdenentwickelung, in welchen die Menschen unrhythmisch überhaupt nicht haben sprechen können, sondern das Bedürfnis hatten, wenn sie überhaupt sprachen, immer im Rhythmus zu sprechen. Es gab Zeiten, in denen man zum Beispiel gar nicht anders konnte, als, wenn man etwas sagte, was einem pointiert erschien, es durch Sprachgestaltung zu sagen. Nehmen wir zum Beispiel in ganz einfacher Weise, jemand wollte aus den Impulsen des ursprünglichen Sprechens heraus sagen, ein Mensch stolpert dahin. Es würde genügt haben, wenn er gesagt hätte, er stolpert über Stock, denn Stöcke, die liegen überall in der Urkultur, oder auch, weil Steine überall liegen, er stolpert über Stein. Aber das sagte er nicht, sondern er sagte, er stolpert über Stock und Stein, weil in dem «Stock und Stein», ganz gleichgültig, ob man exakt die Außenwelt damit bezeichnet oder nicht, ein inneres künstlerisches Gestalten der Sprache liegt. Will man etwas pointiert andeuten, so sagt man, ein Schiff geht nicht bloß unter mit Mann, sondern auch mit demjenigen, das man vielleicht gar nicht gern auf dem Schiffe hat, mit Maus. Man sagt, das Schiff geht unter mit «Mann und Maus», wenn man aus dem ursprünglichen Impuls des Sprechens heraus gestaltet.

Dieser Impuls des Sprechens lebt eigentlich heute am allerwenigsten in der Menschheit. Dafür gibt es Gründe, daß er nicht waltet. Die Gründe bestehen darinnen, daß er schon leider in der Schule nicht waltet, weil unsere Schulen, und zwar im ganzen internationalen Leben, das Künstlerische verloren haben. Deshalb müssen wir ja so stark in der Waldorfschule wiederum für das Künstlerische eintreten, weil unsere Schule das Künstlerische verloren hat und auf die Wissenschaft gestellt ist. Die Wissenschaft ist aber unkünstlerisch. Und so ist eben die Wissenschaft in die Schule hinuntergesickert. Nach und nach, im Laufe der letzten vier bis fünf Jahrhunderte, ist unsere Schule für denjenigen, der mit künstlerischem Gefühl in eine Klasse hineinkommt, das Barbarischeste geworden, das man sich denken kann.

Aber wenn in der Erziehung schon nicht das Künstlerische da ist und gesprochen wird ja in der Klasse, denn Sprechen ist ein Teil des Unterrichtes -, wenn in der Schule schon das Künstlerische nicht da ist, es also nicht in die Erziehung fließt, so ist es ganz selbstverständlich, daß die Menschen es im späteren Leben nicht haben. Und daher hat heute eigentlich die Menschheit am allerwenigsten im allgemeinen künstlerisches Gefühl, und deshalb auch nicht viel künstlerisches Bedürfnis, die Sprache zu gestalten.

Es wird einem auch sehr wenig oft gesagt, das ist nicht schön gesprochen; aber sehr häufig, das ist nicht richtig gesprochen. Der pedantische Grammatiker bessert einen aus, aber der künstlerisch empfindende Mensch bessert einem heute sehr wenig die Sprache aus. Es ist so allgemeine Umgangsform, daß dies nicht so nötig ist.

Der astralische Leib ist zum großen Teil im Unbewußten der Menschen gelegen. Aber der Sprachkünstler muß dasjenige, was im astralischen Leib für das gewöhnliche Sprechen unbewußt abläuft, beherrschen lernen. Das hat man auch allmählich gefühlt in der neueren Zeit. Daher sind die verschiedenen Methoden nicht nur für das Singen, sondern auch für das Rezitieren, Deklamieren und so weiter aufgetreten. Aber dabei verfährt man zumeist in einer eigentümlichen Weise.

Man verfährt so, wie man etwa verfahren würde, wenn man, sagen wit, jemandem das Pflügen lehren wollte und keine Rücksicht darauf nehmen würde, wie der Pflug ausschaut, wie der Acker ausschaut, auf dem man pflügt, was durch das Pflügen erreicht werden soll, sondern fragen würde: Ja, da ist der menschliche Oberarm, der menschliche Unterarm; welchen Winkel soll naturgemäß - dieses Wort gebraucht man ja sehr häufig — Ober- und Unterarm haben? Wie soll sich der Unterschenkel bewegen, wenn sich Ober- und Unterarm in einem bestimmten Winkel bewegen, einstellen? Und so weiter. — Wie wenn man gar nicht Rücksicht darauf nehmen würde, was der Pflug auf dem Felde erreichen soll, und bloß fragen würde, welche Methode bringt den Menschen in eine bestimmte Form von Bewegungen. So sind diese Methoden für das Sprechen eingerichtet. Sie werden mit Ausschluß des objektiven Bestandes der Sprache gepflogen. Pflügen lehrt man einen Menschen dadurch, daß man vor allen Dingen den Pflug zu behandeln weiß, daß man weiß, wie richtig gepflügt wird, und daß man dann achtgibt, daß der Mensch das nicht falsch macht. Und so handelt es sich auch bei der Sprachgestaltung darum, daß alle diese heute in der dilettantischesten Weise aufgestellten Methoden, weil sie das nicht berücksichtigen, was ich gesagt habe, daß diese Methoden von Atemtechnik, Zwerchfelltechnik, Nasenresonanz und so weiter, alle so unterrichten, als ob die Sprache eigentlich gar nicht da wäre, daß sie nicht ausgehen von der Sprache, sondern im Grunde genommen von der Anatomie. Dasjenige, um was es sich handelt, ist, daß man vor allen Dingen den Organismus der Sprache selber kennenlernt. Der Organismus der Sprache ist im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung aus dem Menschen heraus gekommen. Daher wird er im wesentlichen, wenn er richtig erfaßt wird, der menschlichen Organisation nicht widersprechen, und wo er ihr widerspricht, muß es in den Einzelheiten gefunden werden, kann nicht eine Korrektur erfahren durch Methoden, die eigentlich mit der Sprache im Grunde so viel zu tun haben wie das Turnen mit dem Pflügen, wenn nicht gerade ein Pflug unter die Turngeräte aufgenommen würde, was ich bisher in keiner Turnanstalt gefunden habe. Ich würde es nicht als eine Torheit betrachten, einen Pflug unter die Turngeräte aufzunehmen; es wäre vielleicht sogar ganz gescheit, aber es ist eben noch nicht geschehen.

Darum handelt es sich also, daß vor allen Dingen erkannt wird der Sprachorganismus als solcher. Dieser Sprachorganismus, der ist im Grunde genommen so, daß er unmittelbar im Laufe der Menschheitsentwickelung erflossen ist aus der durch das Ich modifizierten Gestaltung des astralischen Menschenleibes. Da kommt die Sprache heraus. Nur so, daß man dabei berücksichtigen muß: der Astralleib stößt nach unten an den Ätherleib, nach oben an das Ich, so wie der Mensch im Wachen ist. Und im Schlafen reden wir ja nicht im normalen Zustande.

Der astralische Leib stößt zunächst an den Ätherleib. Was tut er dabei? Er wendet sich an dasjenige, wovon der Mensch eigentlich im gewöhnlichen Leben sehr wenig weiß; denn mit was hat es der Ätherleib zu tun? Der Ätherleib hat es zunächst damit zu tun, daß er in Empfang nimmt schon dann, wenn wir im Munde das Nahrungsmittel aufgenommen haben, dieses Nahrungsmittel und es allmählich umwandelt, so wie es der menschliche Organismus braucht, besser gesagt, so wie der menschliche Organismus seine Kraft braucht.

Der ätherische Organismus ist derjenige, welcher das Wachstum besorgt hat von der Kindheit bis in den erwachsenen Zustand. Der Ätherleib ist aber auch seelisch beteiligt, er ist dasjenige, was das Gedächtnis besorgt und so weiter. Aber dieser Ätherleib hat Verrichtungen, von denen der Mensch im Grunde genommen sehr wenig weiß. Daher weiß der Mensch kaum, wenn er auch weiß von den Ergebnissen, weiß, ob er satt ist oder Hunger hat, so doch nicht, wie der Ätherleib diese Zustände macht. Die Tätigkeit des Ätherleibes bleibt für den Menschen eigentlich ziemlich unbewußt.

Nun aber spielt sich im Sprechen zwischen dem astralischen Leib und dem Ätherleib alles dasjenige ab, was für die Sprache das Vokalisieren ist. Der Vokal entsteht dadurch, daß der Impuls des Sprechens beim Menschen vom astralischen Leib, wo er urständet, übergeht an den Ätherleib. Der Vokal ist daher etwas, was sich tief im Inneren der Menschennatur abspielt. Unbewußter wird der Vokal gestaltet, als die Sprache im allgemeinen gestaltet wird. Daher handelt es sich gerade bei der Vokalisierung um außerordentlich starke Intimitäten des Sprechens, um dasjenige, was im tiefsten Inneren des Menschen mit der ganzen menschlichen Wesenheit zusammenhängt. So daß wir es also zu tun haben bei der Wirkung des Sprachimpetus auf den Ätherleib mit dem Vokalisieren (siehe Schema).

Nach der anderen Seite stößt der astralische Leib an das Ich. Das Ich ist dasjenige, das in der Form, wie es schon einmal im Erdenmenschen ist, jeder Mensch kennt. Denn das Ich ist es, wodurch wir unsere Sinneswahrnehmungen haben. Das Ich ist es, wodurch wir im wesentlichen auch denken. Dasjenige, was wir als bewußte Tätigkeit ausführen, spielt sich im Ich ab. Weil der astralische Leib daran beteiligt ist, kann das, was sich in der Sprache abspielt, nicht ganz bewußt sich so abspielen wie irgendeine bewußte Willenstätigkeit, aber ein Stück Bewußtsein kommt im gewöhnlichen Sprechen durchaus in das Konsonantisieren hinein, denn das Konsonantisieren spielt sich ab zwischen dem astralischen Leib und dem Ich (siehe Schema),

Da ist zunächst einmal auf die menschliche Natur verwiesen in bezug auf die Konsonanten- und Vokalbildung. Wir können aber weitergehen. Wir können uns jetzt fragen: Was stellt denn die Sprache in der Gesamtheit der menschlichen Wesenheit überhaupt dar? — Diese Frage beantwortet man richtig eigentlich nur dann, wenn man dazu sich frägt: Wie war es denn eigentlich in der menschlichen Ursprache, in der Sprache, wie sie zuerst unter die Menschheit getreten ist?

Diese Sprache war eigentlich etwas Wunderbares. Abgesehen davon, daß der Mensch von vornherein veranlaßt sich gesehen hat, im Rhythmus, im Takt zu sprechen, sogar in Assonanz und Alliteration zu sprechen, abgesehen davon war es in dieser Ursprache so, daß der Mensch in der Sprache fühlte und in der Sprache dachte. Das Gefühlsleben der Urmenschheit war so, daß man nicht solche abstrakten Gefühle hatte wie heute, sondern daß in dem Augenblick, wo man ein Gefühl hatte, und sei es auch das intimste Gefühl, man sogleich zu irgendeiner Sprachgestaltung kam. Man konnte in alten Zeiten nicht zärtliche Gefühle, sagen wir, für ein Kind entwickeln, ohne diese zärtlichen Gefühle durch den eigenen seelischen Impetus in der Sprache zu gestalten. Es würde keinen Sinn gehabt haben, von einem Kinde bloß zu sagen: Ich liebe das Kind zärtlich -, sondern es hätte vielleicht einen Sinn gehabt, wenn man gesagt hätte: Ich liebe das Kind so eiei-ei. - Es war immer das Bedürfnis, das ganze Gefühl zu durchdringen mit Sprachgestaltung.

Ebensowenig hatte man in alten Zeiten abstrakte Gedanken, wie wir sie heute haben. Abstrakte Gedanken ohne Sprache gab es in alten Zeiten nicht, sondern, wenn der Mensch etwas dachte, wurde es in ihm zum Worte und zum Satze. Er sprach innerlich. Daher ist es selbstverständlich, daß man im Beginne des Johannes-Evangeliums nicht sagte: Im Urbeginne war der Gedanke -, sondern: Im Urbeginne war das Wort - das Verbum. - Das Wort, weil man innerlich redete, und nicht abstrakt dachte wie heute. Man redete innerlich. Und es war die Ursprache so, daß sie Gefühle und Gedanken enthieit. Sie war gewissermaßen das Schatzkästlein in der menschlichen Wesenheit für Gefühl und Gedanke.

Nun ist der Gedanke mehr in das Ich hinaufgerutscht, die Sprache im astralischen Leib verblieben, und das Gefühl in den Ätherleib hinuntergerutscht, so daß wir sagen können (siehe Schema Seite 67): Mensch, innerlich; nach außen, wo das Ich mehr beteiligt ist; nach innen, noch mehr verinnerlicht, wo der Ätherleib beteiligt ist, also wo es ganz in das Innere hineingeht.

Die Urpoesie war eine Einheit, sie drückte in der Sprache Gefühl und Gedanke, die man über die Dinge haben konnte, aus. Die Urpoesie war eine Einheit. Dadurch, daß die Sprache nach dem Inneren des Menschen das Gefühl abgeladen hat, das nach dem Ätherleib rutscht, entsteht die lyrische Stimmung der Sprache. Dasjenige, dem die Urpoesie am ähnlichsten geblieben ist, das also auch am meisten in der Sprache selber liegt, das ohne etwas zu erneuern von dem Urgefühl gegenüber der Sprache gar nicht gepflegt werden kann, das ist die Epik, die unmittelbar aus dem astralischen Leibe kommt. Dasjenige aber, was die Sprache nach außen hin treibt, zum Ich hin, das mit der Außenwelt zunächst beim Erdenmenschen in Verbindung steht, das ist die Dramatik.

Der für die Dramatik tätige Künstler steht in der Regel, wenn er nicht monologisch spricht, einem anderen gegenüber. Und daß er dem anderen gegenübersteht, das gehört geradeso zu seinem Sprechen wie dasjenige, was er in sich selber erlebt.

Der Lyriker steht keinem anderen gegenüber. Er steht nur sich selbst gegenüber. Sein Sprechen muß so gestaltet werden, daß dieses Sprechen der reine Ausdruck des menschlichen Inneren wird. Die heutige Lyrik kann daher nicht anders gesprochen werden, als daß - wir werden das später alles deutlicher ausführen - selbst das Konsonantisieren etwas nach dem Vokalisieren hinüberneigt. Lyrik zu sprechen macht notwendig, daß man weiß, daß jeder Konsonant auch eine gewisse vokalische Nuance in sich trägt, zum Beispiel das l ein i, was Sie daran sehen können, daß in manchen Sprachen zu einer bestimmten Zeit eine l-Entwickelung in einem Worte stattfindet, in anderen Formen aber noch ein ; dasteht. So hat aber jeder Konsonant etwas Vokalisches in sich. Und für den Lyriker ist es vor allen Dingen notwendig, daß er das Vokalische eines jeden Konsonanten empfinden lernt.

Der Epiker muß vor allen Dingen ein Gefühl dafür entwickeln ich meine jetzt immer den Deklamator oder Rezitator, also denjenigen, der die Epik an das Publikum heranbringt -: Sobald du an den Vokal herankommst, kommst du an den Menschen heran; sobald du an den Konsonanten herankommst, schnappst du in die Dinge ein. Dadurch wird gerade die Epik möglich. Sie hat es nicht nur mit dem menschlichen Inneren zu tun, sondern mit diesem menschlichen Inneren und mit einem gedachten Äußeren. Denn dasjenige, wovon der Epiker erzählt, ist nicht da, sondern es wird nur gedacht. Es gehört der Vergangenheit an, oder es wird überhaupt von einer Sache nur erzählt, wenn sie nicht da ist, sonst ist keine Veranlassung, daß von einer Sache erzählt wird. Der Epiker also hat es mit dem Menschen und der gedachten Sache zu tun.

Der Dramatiker hat es mit dem wirklichen Objekte zu tun. Derjenige, an den er sich wendet, steht vor ihm. Das gibt auch die Unterschiede, die wir strenge beachten müssen. Es wird gefühlt werden müssen dasjenige, was ich schon, wenn ich von verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten aus da oder dort eine Anregung gegeben habe, nach einer gewissen Terminologie suchend, auch schon gesagt habe; es wird das tatsächlich genau durchfühlt werden müssen. So wird man durchfühlen müssen: lyrisch sprechen bedeutet, aus dem menschlichen Inneren heraus sprechen. Das Innere offenbart sich selbst. Wenn sein Inneres sich von ihm losringen will, wenn das Innere von irgend etwas so stark impulsiert ist, daß es aus sich heraus muß — und das ist bei der Lyrik der Fall -, dann geht das bloße Fühlen in das Rufen, clamare über, und dann entsteht, wenn es sich um das Sprechen handelt, die Deklamation. So daß ein Teil der Sprechkunst die Deklamation ist, die vorzugsweise auf das Lyrische hinzugehen hat.

Natürlich ist aber das Lyrische wieder enthalten in jeder Form der Dichtung, daher handelt es sich darum, daß in gewissen Stellen auch beim Epiker, auch beim Dramatiker der Übergang ins Lyrische notwendig ist. Bei dem Epiker handelt es sich darum, daß er ein gedachtes Objekt hat, das er durch seine eigene sprachliche Zauberkunst zitiert und immer wiederum zitiert. Der Epiker rezitiert vorzugsweise,

Der Lyriker drückt sich aus, offenbart sich, ist ein Deklamator. Derjenige, der sein Objekt zitiert, durch die Zauberkunst der Sprache es gegenwärtig macht vor dem Publikum, der ist ein Rezitator. Weiterzugehen habe ich ja erst da Veranlassung, wo eine vollständige Entwickelung der Sache gegeben werden soll.

Derjenige, der dann nicht nur sein gedachtes Objekt vor sich hat, das er zitiert, sondern der dieses Objekt, gegenüber dem er spricht, leibhaftig vor sich hat, der konversiert. Das ist die dritte Form: Konversation.

In diesen drei Arten der Sprachgestaltung besteht eigentlich die Kunst des Sprechens. Das letztere wird am meisten verkannt, weil die Konversation am meisten aus dem Künstlerischen herausgeholt worden ist, und weil Konversation zu beurteilen eigentlich heute mehr die Menschen berufen sind, die weniger der Kunst, als, sagen wir, dem Diplomatischen oder dem Five-o’clock-tea-mäßigen oder sonst solchen Dingen nahestehen. So ist gar nicht mehr gefühlt, daß Konversation etwas hoch Künstlerisches in sich schließen kann. Indem aber die Schauspielkunst selbstverständlich monologisierend wird, greift sie wiederum hinüber in die anderen Gebiete, in die Deklamation und die Rezitation.

Daraus schon, indem ich dieses in einer etwas pedantischen Form noch vor Sie hinstelle, ersehen Sie, daß darauf hingearbeitet werden muß, wirklich für die Sprachgestaltung so etwas zu schaffen, wie es für den Musikunterricht zum Beispiel da ist. Denn es wird zum Beispiel durchaus notwendig sein, irgendeinen Dialog, der auf der Bühne auftritt, wirklich in konversationsmäßigem Sinne zu gestalten.

Nun handelt es sich darum, daß innerhalb der Sprache selbst, wenn man sie richtig betrachtet, die Notwendigkeit der Gestaltung wiederum hervorgeht. Denn bedenken Sie, wir haben so etwa zweiunddreißig Laute. Denken Sie, wenn Sie Goethes «Faust» in die Hand nehmen, und wenn einer gerade so weit wäre, die Laute zu kennen, aber noch nicht die Laute verbinden zu können, so würde der ganze «Faust» aus zweiunddteißig Lauten bestehen. Es ist nämlich gar nichts anderes darinnen im ganzen «Faust» als diese zweiunddreißig Laute, und doch werden sie in ihrer Kombination zum Goetheschen «Faust».

Daraus folgt sehr vieles. Wir haben nun einmal etwa diese zweiunddreißig Laute. Aber alles dasjenige, was den ganz unermeßlichen Reichtum des Sprachlichen hervorruft, besteht in der Gestaltung von Laut auf Laut. Das wird aber auch schon innerhalb des Lautsystems selbst gestaltet. So denken Sie sich zum Beispiel, wir sprechen einfach den Laut a. Was ist er? Der Laut a löst sich aus der Seele ursprünglich heraus, wenn diese Seele in Bewunderung erfließt. Bewunderung, Erstaunen vor etwas, über etwas, sondert aus der Seele den a-Laut los. Jedes Wort, in dem der «-Laut steht, ist dadurch entstanden, daß der Mensch die Verwunderung an der Sache hat ausdrücken wollen. Und Sie werden niemals ganz fehlen und ganz dilettantisch gehen, wenn Sie ein beliebiges Wort nehmen, zum Beispiel Band = ein a ist darinnen. Irgendwie geht das darauf zurück, daß der Mensch über etwas, was im Bande sich darstellt, verwundert war und daher den a-Laut hineinbrachte.

Daß es in einer anderen Sprache anders heißt, macht nichts aus; da hat man sich eben anders zu der Sache gestellt. Und wenn der Mensch über etwas ganz besonders verwundert ist und noch etwas versteht, darüber verwundert zu sein, wie das bei der Bildung der Sprachen der Fall war, dann drückt er das ganz besonders durch den a-Laut aus. Man muß nur verstehen, Verwunderung an der richtigen Stelle zu haben. Man kann verwundert sein über den üppigen Haarwuchs, den irgendein menschliches Wesen an sich trägt. Man kann verwundert sein über den Kahlkopf, dem die Haare wieder ausgefallen sind. Man kann verwundert sein darüber, was ein Haarwasser bewirkt hat, wenn es mangelnden Haarwuchs wieder ersetzt hat. Alles, was mit Haaren zusammenhängt, kann die tiefsteBewunderung hervorrufen. Man schreibt daher nicht «Har», sondern sogar zweimal das a: «Haar» hin.

Sie werden nicht sehr weit weg sein von dem, was im Beginne der Menschheitsentwickelung ein solches Wort war, eine viel stärkere Wirklichkeit war als diejenige, von der unsere heutige Erkenntnis oftmals spricht, wenn Sie überall da, wo Sie a haben, den Ausgangspunkt für die Bildung des Wortes bei der Verwunderung suchen.

Was bedeutet das aber? Das bedeutet, daß der Mensch, indem er sich verwundert, indem er erstaunt ist über eine Sache, in dieser Sache aufgeht. Worin besteht der a-Laut? In dem absoluten Öffnen des ganzen Sprachorganismus. a bedeutet, vom Mund angefangen, das vollständige Öffnen des Sprachorganismus. Der Mensch läßt seinen astralischen Leib nach außen fließen. Der Mensch beginnt, indem er a sagt, zu schlafen; er hindert es nur gleich wiederum. Aber wie oft ist die Müdigkeit, wenn sie sich ausdrücken will, verbunden mit dem «Laut! a-sagen bedeutet immer ein Heraustretenlassen, wenigstens den Beginn eines Heraustretenlassens des astralischen Leibes. Das a ist das Öffnen nach außen.

Der völlige Gegensatz des a ist das u. Indem Sie das u aussprechen, schließen Sie vom Munde ab alles, was nur zu schließen ist, und lassen den Laut durchgehen: u. Am meisten wird beim u geschlossen. Das ist der Gegensatz: a u. Zwischen a und u liegt das o. Das o enthält in der Sptachgestaltung eigentlich die Vorgänge des a, die Vorgänge des u, die Vorgänge des Sich-Öffnens, die Vorgänge des Sich-Schließens in harmonischer Verbindung.

Das u bedeutet, daß wir eigentlich immer aufwachen, mehr auf wachen, als wir aufgewacht sind. Wer u ausspricht, deutet darauf hin, daß er aufwachen möchte in bezug auf den Gegenstand, den er wahrnimmt. Man kann nicht stärker ausdrücken, daß man aufwachen möchte, als wenn die Eule sich geltend macht. Dann sagt man «Uhu». Die Eule veranlaßt, daß man so recht wachen möchte der Eule gegenüber.

Und wenn einer einen, sagen wir, mit Streusand bewirft — aber das gibt es heute nicht mehr -, dann wird man «uff» sagen, wenn man sich unbefangen seiner Empfindung überläßt, wenn einen etwas aufweckt, oder wenn man aufwachen will. Das u löst sich los. Der astralische Leib verbindet sich intensiver mit dem Ätherleib und dem physischen Leib. Das «a ist daher am meisten konsonantisch, und das z ist am meisten vokalisch.

Bei manchen Menschen kann man in den deutschen Dialekten gar nicht mehr unterscheiden, ob sie ein a oder ein r sagen, denn es wird das r bei ihnen vokalisch und das a konsonantisch. Im steirischen Dialekt kann ‚man nicht unterscheiden, ob man sagen soll Bur oder Bua, r oder a.

Aber alle anderen Vokale liegen zwischen a und u. Das o ist gewissermaßen mitten darinnen, nicht ganz mitten darinnen, sondern so darinnen in der Mitte, wie die Quart in der Oktave in der Mitte darinnen liegt in der Skala. Das o liegt zwischen beiden.

Aber jetzt nehmen wir folgendes. Jemand will dasjenige, was im o liegt, ausdrücken. Das o ist der Zusammenfluß von a und , ist der Zusammenfluß von Einschlafen und Aufwachen. Gerade der Moment entweder des Einschlafens oder des Erwachens ist das o. Wenn der Orientale seine Schüler anwies, weder zu schlafen noch zu wachen, sondern an jene Grenze zwischen Wachen und Schlafen zu gehen, wo man so viel erfahren kann, was man weder im Schlafen noch im Wachen erfahren kann, dann wies er sie an, die Silbe om zu sprechen. Damit verwies er sie auf das Leben zwischen Wachen und Schlafen.