Colour

Part I

GA 291

6 May 1921, Dornach

1. Colour-Experience

Colour, the subject of these three lectures, interests the physicist and—though we shall not speak of it from this aspect today—it interests also—or should do—the psychologist; more than all these, it must interest the artist, the painter. In a survey of the modern idea of the world of colour, we notice that although the psychologist may, admittedly, have something to say about the subjective experience of colour this is nevertheless of no value for the knowledge of the objective nature of the world of colour—a knowledge which really lies only in the province of the physicist. In the first place, Art is not allowed to decide anything at all about the nature of colour and its quality in the objective sense. At the present time people are very far from what Goethe intended in his oft-repeated utterance: “The man to whom Nature begins to reveal her open secret feels an irresistible longing for her most worthy interpreter—Art.”

Any one who, like Goethe, really lives in art, can never doubt that what the artist has to say about the world of colour must be bound up with the nature of colour. In ordinary life colour is dealt with according to the surface of the objects presenting themselves to us as coloured, according to the impressions received through the nature of the coloured object.

We obtain the colour fluctuating, in a sense, varying, as it were, through the well-known prismatic experiment, and we look into, or try to look into the world of colour in many ways. In so doing we have always in mind the idea that we ought to estimate colour according to subjective impressions. For a long time it has been the custom—we might say, the mischievous custom—in some places, to contend that what we perceive as a coloured world really exists only for our senses, whereas in the world outside, objective colour presents nothing but certain undulatory movements of the very finest substance, known as ether. Any one who wishes to form an idea from definitions and explanations such as these is able to make nothing of the concept that what he knows as colour-impressions, his personal experience of colour, has to do with some kind of ether in motion. Yet when people speak of the quality of colour, they really have only the subjective impression in mind, and seek for something objective. They then wander away from colour, however, for in all the vibrations of ether which are thought out, there is really nothing further from the content of our real world of colour. In order to arrive at the objective nature of colour we must try to keep to the world of colour itself and not leave it; then we may hope to fathom its real nature.

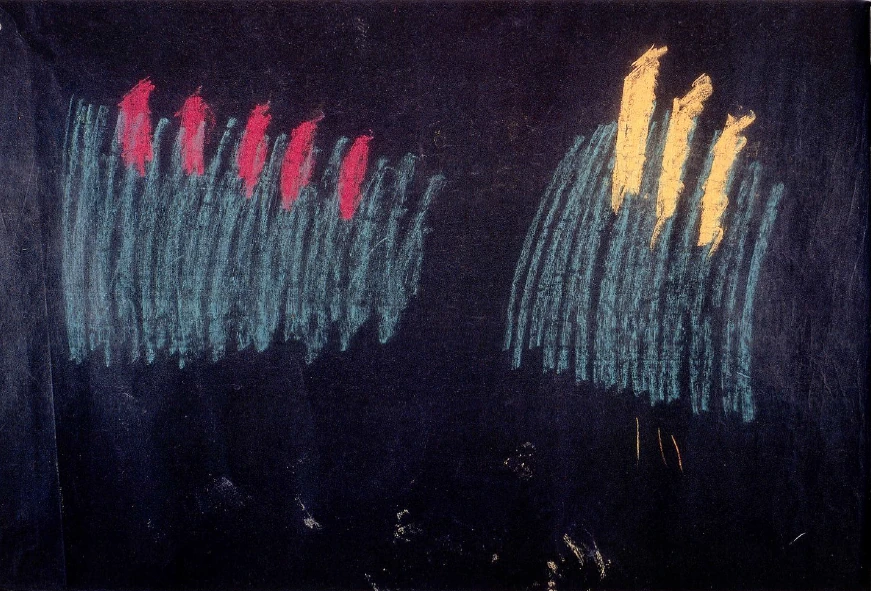

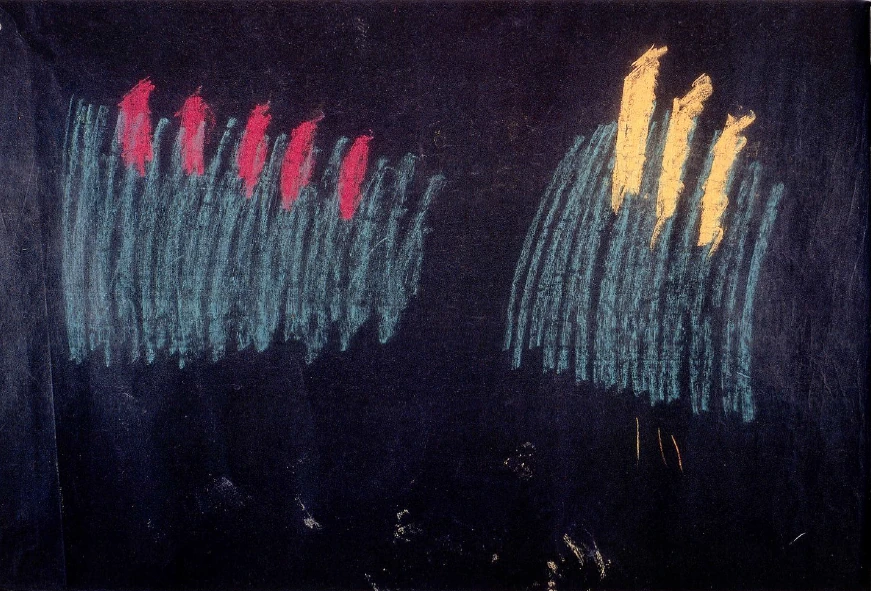

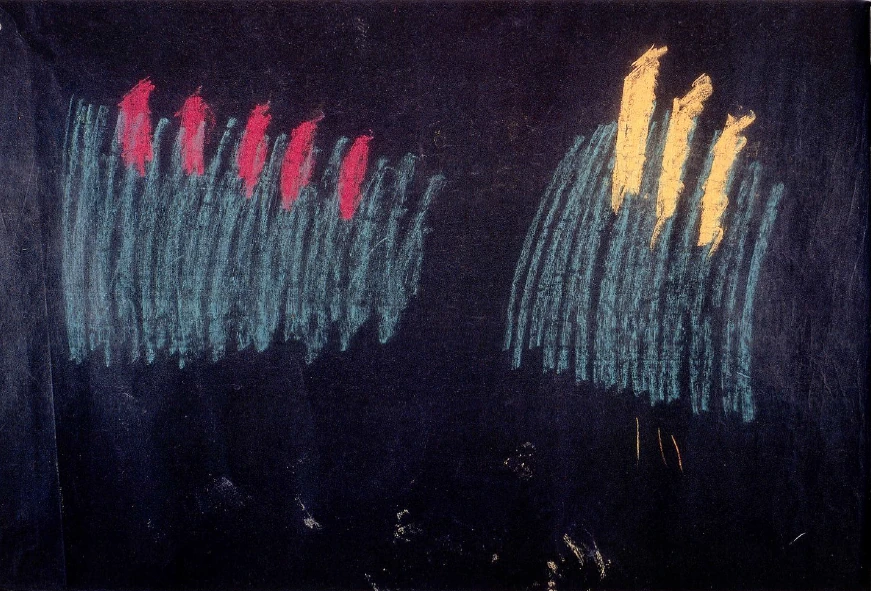

Let us try for a while to sink ourselves into something which can be given us from the whole wide, varied world of colour. Then in order to penetrate into the nature of colour, we must experience something in regard to it which raises the whole consideration into our life of feeling. We must try to question our feeling as to what colour is in our surrounding world. In a sense we shall best proceed by means of an inward experiment, so that we may have before us not only the processes which on the whole are difficult to analyze and are not easily seen, but we will proceed at once to the essential thing. Suppose we colour a flat surface green. We shall only sketch this roughly. (see Diagram 1)

If we simply allow the colour to stimulate our feelings, we can experience something in green as such, something which we need not define further. No one will doubt that we can experience the same thing when gazing on the green plant-covering of the earth; we must do so, of course, because it is green. We must disregard everything else offered by the plants, as we only wish to look at the greenness. Let us suppose we have this greenness before our mental eyes.

When painting, we can introduce different colours into this greenness. Let us picture three. We have before us three green surfaces. Into the first we will introduce red; into the second, peach-blossom colour; into the third, blue.

You must admit that the sensation aroused is very different in the three cases, that there is a certain quality of sensation when red, peach-blossom colour, or blue forms are pictured in the green. It is now a question of expressing in some way the content of the sensation thus presented to our soul.

If we wish to express such a thing as this, we must try to characterize it, for extremely little can be attained by abstract definitions. We must try to describe it somehow. Let us try to do so by bringing a little imagination into what we have painted before us. Suppose we really wish to produce the sensation of a green surface in the first place, and in it we paint red figures. Whether we give them red faces and red skin, or whether we paint them entirely red, is immaterial. In the first example we paint red figures; in the second, peach-blossom colour—which would approximate human flesh-colour—and on the third green surface we paint blue figures. We are not copying Nature in this experiment, but placing something before the soul in order to bring a complex of sensation into discussion.

Suppose we have before us this landscape: Across a green meadow red, peach-blossom colour or blue figures are passing; in each of the three cases we have an utterly different complex of sensation. If we look at the first we shall say: These red figures in the green meadow enliven the whole of it. The meadow is greener because of them; it becomes still more saturated with green, more vivid because red figures are there, and we ought to be enraged on seeing these red figures. We may say: That is really nonsense, an impossible case. I should really have to make the red figures like lightning, they must be moving. Red figures at rest in a green meadow act disturbingly in their repose, for they are already in motion by reason of their red colour; they produce something in the meadow which it is really impossible to picture at rest. We must come into a very definite complex of feeling if we wish to make such a concept at all.

The second example is harmonious. The peach-blossom coloured figures can stand there indefinitely; if they stand there for an hour it does not trouble us. Our sensation tells us that these peach-blossom coloured figures have really no special conditions; they do not disturb the meadow, they do not enhance its greenness, they are quite neutral. They may stand where they will, it does not trouble us. They suit the meadow everywhere; they have no inner connection with the green meadow.

We pass on to the third; we look at the blue figures in the green meadow. That does not last long, for the blue figures deaden the green meadow to us. The greenness of the meadow is weakened. It does not remain green. Let us try to realize the right imagination of blue figures walking over a green meadow; or blue beings generally, they might be blue spirits. The meadow ceases to be green, it takes on some of the blueness, it becomes itself bluish, it ceases to be green. If the figures stay there long we can no longer picture them at all; we have the idea that there must be somewhere an abyss, and that the blue figures take the meadow from us, carry it away and cast it into the abyss. It becomes impossible; for a green meadow cannot remain if blue figures stand there; they take it away with them.

That is colour-experience. It must be possible to have it, otherwise we shall not understand the world of colour. If we wish to acquaint ourselves with something which finds its most beautiful and significant application in imagination, we must be able to experiment in that sphere. We must be able to ask ourselves: What happens to a green meadow when red figures walk therein? It becomes still greener; it becomes very real in its greenness. The green begins veritably to burn. The red figures bring so much life into the greenness that we cannot think of them in repose. They must really be running about. If we wish to portray it exactly and to paint the true picture of the meadow, we should not paint red figures standing quietly in it; they must be seen dancing in a ring. A ring of red dancers would be permissible in a green meadow.

On the other hand, people clothed not in red but entirely in flesh-colour might stand for all eternity in a green meadow. They are quite neutral to the green; they are absolutely indifferent to the meadow; it remains as it is, not the slightest tint is altered.

In the case of the blue figures, however, they run from us with the meadow, for the entire meadow loses its greenness because of them. We must, of course, speak comparatively when speaking of experiences in colour. We cannot talk like pedants about colour-experiences, for we cannot approach them so. We must speak in analogy—not, indeed, as those who say that one billiard ball pushes another; stags push, also bullocks and buffaloes, but not billiard balls in actual fact. Nevertheless, in Physics we speak of a “thrust” because everywhere we need the support of analogy if we are to begin to speak at all.

Now this makes it possible to see something in the world of colour itself, as such. There is something in that world which we shall have to seek as the nature of colour. Let us take a very characteristic colour, one we have already in mind, the colour which meets us everywhere in summer as the most attractive—green. We find it in plants; we are accustomed to regard it as characteristic of them. There is no other such intimate connection as that of greenness with the plant. We do not feel it as a necessity that certain animals which are green could only be green; we have always the subconscious thought that they might be some other colour; but as regards the plants our idea is that greenness belongs to them, that it is something peculiarly their own. Let us endeavour by means of the plants to penetrate into the objective nature of colour—as a rule the subjective nature alone is sought.

What is the plant, which thus, as it were, presents green to us? We know from Spiritual Science that the plant owes its existence to the fact that it has an etheric body in addition to its physical body. It is this etheric body which really lives in the plant; but the etheric body is not itself green. The element which gives the plant its greenness is, indeed, in its physical body, making green peculiar to the plant, but in reality it cannot be the essential nature of the plant, for that lies in the etheric body. If the plant had no etheric body it would be a mineral. In its mineral nature the plant manifests itself through green. The etheric body is quite a different colour, but it presents itself to us by means of the mineral green of the plant. If we study the plant in relation to its etheric body, if we study its greenness in this connection, we must say: if we set on the one hand the essential nature of the plant, and on the other the greenness, dividing it abstractly, taking the greenness from the plant, it is really as though we simply made an image of something; in the greenness withdrawn from the etheric we have really only an image of the plant, and this image peculiar to it is necessarily green. We really find in greenness the image of the plant. While we ascribe the colour green very positively to the plant, we must ascribe greenness to the image of the plant and must seek in the greenness the special nature of the plant-image.

Here we come to something very important. Anyone entering the portrait gallery of some ancient castle—such as may still frequently be seen—will not fail to say that the portraits are only the portraits of the ancestors, not the ancestors themselves. As a rule, the ancestors are not there, only their portraits are to be found. In the same way, we no more have the entity of the plant in the green than we have the ancestors in the portraits. Now let us reflect that the greenness is characteristic of the plant, and that of all beings the plant is the being of life. The animal possesses a soul; man has both spirit and soul. The mineral has no life. The plant is a being of which life is the special characteristic. The animal has, in addition, a soul. The mineral has as yet no soul. Man has, in addition to the soul, a spirit. We cannot say of man, of the animal or of the mineral, that its peculiar feature is life; it is something else. In the case of the plant its characteristic is life. The green colour is the image. Thus we remain entirely within the world of objective fact in saying that green represents the lifeless image of life.

We have now—we will proceed inductively, if we wish to express ourselves in a scholarly way—we have now gained something by means of which we can place this colour objectively in the world. When I receive a photograph I can say that it is a portrait of Mr. N. In the same way we can say that green is the lifeless image of life. We do not now think merely of the subjective impression, but we realize that green is the lifeless image of life.

Let us now take peach-blossom colour. More exactly, let us call it the colour of the human skin; of course, it is not the same for all people, but this colour, speaking generally, is that of the human skin. Let us endeavour to arrive at its essential nature. As a rule we see this human skin-colour only from outside. The question now arises as to whether a consciousness of it, a knowledge of it, can be gained from within, as we did in relation to the green of the plant. It can, indeed, be done in the following way.

If a man really tries to imagine himself inwardly ensouled, and thinks of this ensouling as passing into his physical bodily form, he can imagine that in some way that which ensouls him flows into this form. He expresses himself by pouring his soul-nature into his form in the flesh-colour. What this means can best be realized by looking at a man in whom the psychic nature is withdrawn somewhat and does not ensoul the outer form. What colour does he then become? Green; he becomes green. Life is there, but he becomes green. We speak of green men; we know the peculiar green of the complexion when the soul is withdrawn; we can see this very well by the colour of the complexion. On the other hand, the more a person assumes the special florid tint, the more we shall notice his experience of this tint. If you observe the constitutional humour in a green person and in one who has a really fresh flesh-colour, you will see that the soul experiences itself in the flesh-colour. That which rays outwards in the colour of the skin is none other than the man's self-experience. We may say that in flesh-colour we have before us the image of the soul, really the image of the soul. If, however, we go far into the world around, we must select the lifeless peach-blossom colour for that which appears as human flesh-colour. We do not really find it in external objects. What appears as human flesh-colour we can only attain by various tricks of painting. It is the image of the soul-nature, but it is not the soul itself; there can be no doubt about that. It is the living image of the soul. The soul experiences itself in flesh-colour. It is not lifeless like the green of the plant, for if a man withdraws his soul more and more he becomes green. He can become a corpse. In flesh-colour we have the living. Thus peach-blossom colour represents the living image of the soul.

We have now passed on to another colour. We endeavour to keep objectively to the colour, not merely to reflect upon the subjective impression and then to invent some kind of undulations which are then supposed to be objective. It is palpable that it is an absurdity to separate human experience from flesh-colour. The experience in the body is quite different when the colour of the flesh is ruddy and when it is greenish. There is an inward entity which really presents itself in the colour.

We now pass on to the third colour, blue, and say: We cannot in the first place find a being to which blue is peculiar as green is to the plant. Nor can we speak of blue as we have spoken of the peach-blossom-like flesh-colour of man. In the case of animals we do not find a colour as innate to the animal as green is to the plant and flesh-colour to man. We cannot in this way start from blue in regard to Nature. We nevertheless wish to go forward; we will see whether we can proceed still further in our search into the essential nature of colour. We cannot continue by way of blue, but it is possible to proceed first of all to the light colours; we shall, however, progress more easily and quickly if we take the colour known as white. We cannot say that white is peculiar to any being in the outer world. We might turn to the mineral kingdom, but we will try in another way to form an objective idea of white. If we have white before us and expose it to the light, if we simply throw light upon it, we feel that it has a certain relationship to light. At first this remains a feeling. It will at once become more than a feeling if we turn to the sun, which appears tinged quite distinctly in the direction of white, and to which we must trace back all the natural illumination of our world.

We might say that what appears to us as sun, what manifests itself as white—which at the same time shows an inner relationship to light—has the peculiarity that of itself it does not appear to us at all in the same way as an external colour. An external colour appears to us upon the object. Such a thing as the white of the sun, which for us represents light, does not appear to us directly on objects. Later on we shall consider the kind of colour which we may call the white of paper, chalk and the like, but to do this we shall have to enter upon a bypath. To being with, if we venture to approach white, we must say that we are led by white first of all to light as such. In order fully to develop this feeling, we need do no more than say to ourselves that the polar opposite of white is black. That black is darkness, we no longer doubt; so we can very easily identify white with brightness, with light as such. In short, if we raise the whole consideration into feeling, we shall find the inner connection between white and light. We shall go more fully into this question later.

If we reflect upon light itself, and are not tempted to cling to the Newtonian fallacy; if we observe these things without prejudice, we shall say to ourselves that we actually see colours.

Between white, which appears as colour, and light there must be a special relation. We will therefore first of all exclude true white. We know of light as such, not in the same way as other colours. Do we really perceive light? We should not perceive colours at all if we were not in an illuminated space. Light makes colours perceptible to us, but we cannot say we perceive light just as we do colours. Light is indeed, in the space where we perceive a colour, but it is in the nature of light to make the colours perceptible. We do not see light as we see red, yellow, blue, etc. Light is everywhere where it is bright, but we do not see it. Light must be fixed to something if we are to perceive it. It must be caught and reflected. Colour is on the surface of objects; but we cannot say that light belongs to something, it is wholly fluctuating. We ourselves, however, on awakening in the morning when the light streams upon us and through us, feel ourselves in our true being; we feel an inner relationship between the light and our essential being. At night, if we awake in dense darkness, we feel we cannot reach our real being; we are then, indeed, in a sense withdrawn into ourselves, but through the conditions we have become something which does not feel in its element. We know, too, that what we have from the light is a “coming to ourselves.” That the blind do not have it, is no contradiction; they are organized for this, and the organization is the essential point. We bear to the light the same relationship as that of our ego to the world, yet, again, not the same; for we cannot say that when the light fills us we gain the ego. Nevertheless, for us to gain this ego, light is essential, if we are beings which see.

What underlies this fact? In light we have what is represented in white—we have yet to learn the inner connection—we have in light what really fills us with spirit, brings to us our own spirit. Our ego, that is, our spiritual entity, is connected with this condition of illumination. If we consider this feeling—all that lives in light and colour must first be grasped as feeling—if we consider this feeling we shall say: There is a distinction between light and that which manifests itself as spirit in the ego, in the “I.” Nevertheless, the light gives us something of our own spirit. We shall have an experience through the light in such a way that by means of the light the ego really experiences itself inwardly.

If we sum up all this, we cannot but say that the ego is spiritual and must experience itself in the soul; this it does when it feels itself filled with light. Reduced to a formula, it may be expressed in the words: White or light represents the psychic image of the spirit.

It is natural that we should have to construct this third stage from pure feeling; but if you try to sink yourselves deeply into the matter according to these formulae, you will see that a great deal is contained in them:

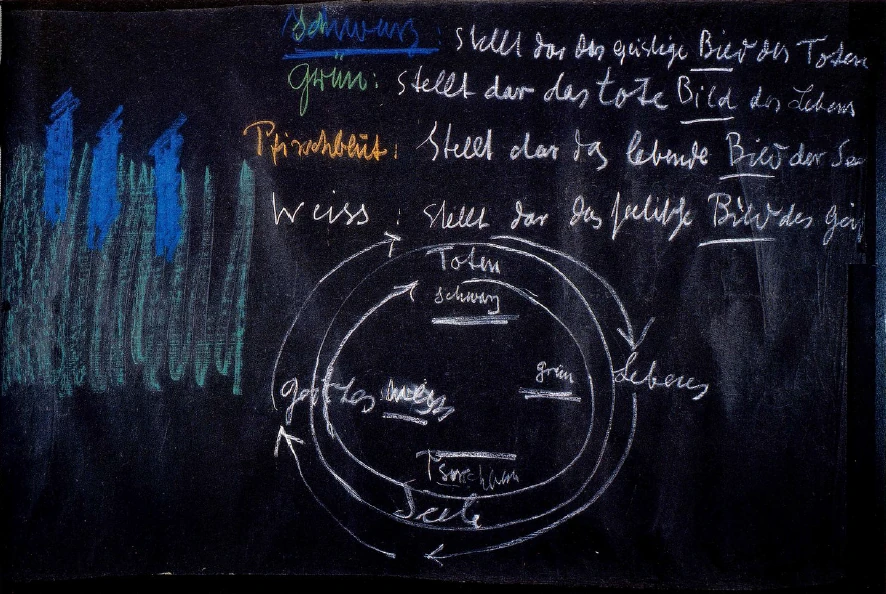

Green represents the lifeless image of Life.

Peach-blossom colour represents the living image of the Soul.

White or Light represents the psychic image of the Spirit.

Let us now pass on to black or darkness. We see that we can speak of white or light, brightness, in connection with the relation which exists between darkness and blackness. Let us now take black, and try to connect something with a black darkness. We can do so. Certainly black is easy to find as a characteristic of something even in Nature, just as green is an essential peculiarity of the plants. We need only look at carbon. In order to represent more clearly that black has something to do with carbon, let us realize that carbon can also be quite clear and transparent; but then it is a diamond. Black, however, is so characteristic of carbon that if it were not black, if it were white and transparent, it would be a diamond. Black is so integral a part of carbon that the latter really owed its whole existence to the blackness. Thus carbon owes its dark, black, carbon-existence to the dark blackness in which it appears; just as the plant has its image somehow in green, so carbon has its image in black.

Let us place ourselves in blackness, absolute black around us, black darkness—in black darkness no physical being can do anything. Life is driven out of the plants when they become charcoal, carbon or coal. Thus black shows itself to be foreign in life, hostile to life. We see this in carbon, for when plants are carbonized they turn black; Life, then, can do nothing in blackness. Soul—the soul slips away from us when awful blackness is within us. The spirit, however, flourishes; the spirit can penetrate the blackness and make its influence felt within it. We may therefore say that in blackness—and if we endeavour to investigate the art of black and white, light and shade on a surface—we shall return to this later—then, by drawing with black on a white surface we bring spirit into the white surface by means of the black strokes; in the black surface the white is spiritualized. The spirit can be brought into the black. It is, however, the only thing that can be brought into black. Therefore we obtain the formula:

Black represents the spiritual image of the lifeless.

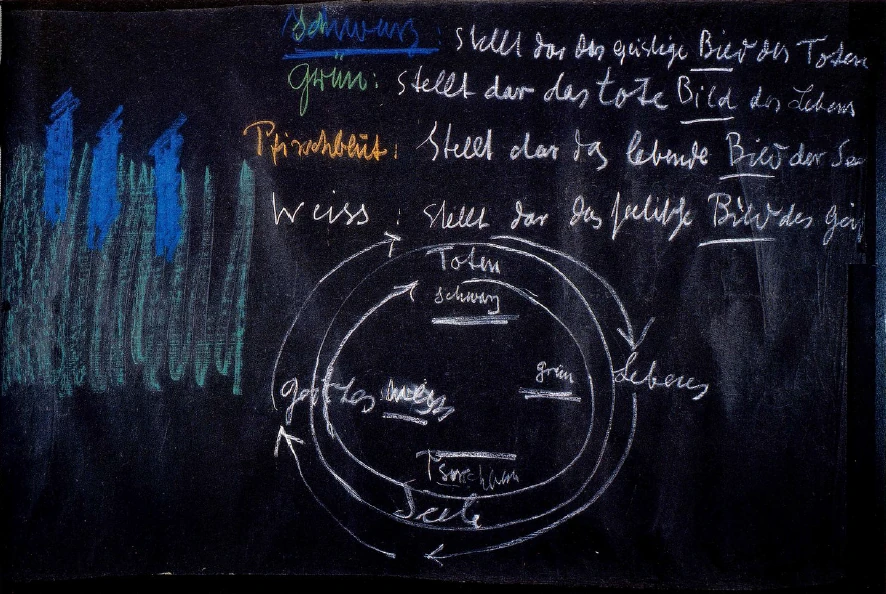

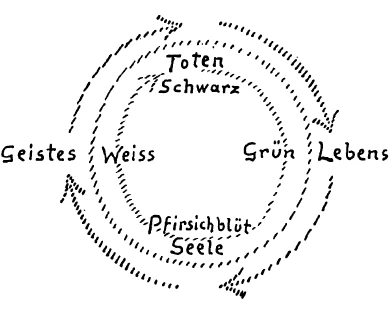

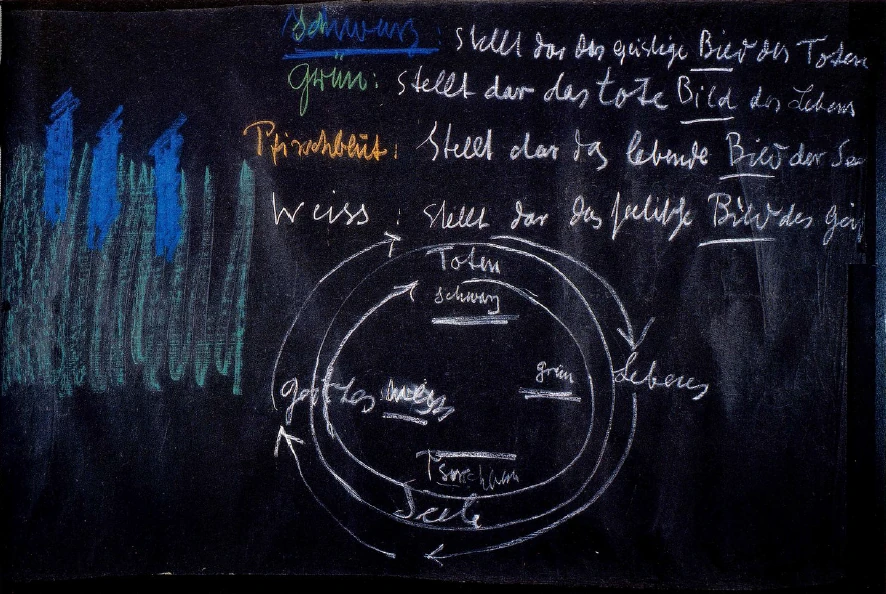

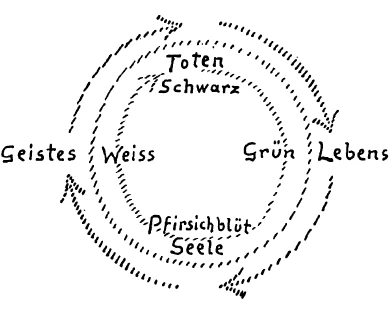

We have now obtained a remarkable circle respecting the objective nature of colour. In this circle we have in each colour an image of something. In all circumstances colour is not a reality, it is an image. In one case we have the image of the lifeless, in another the image of life, in another the image of the soul, and the image of the spirit (see Diagram 2). As we go around the circle, we have black, the image of the lifeless; green, the image of life; peach-blossom colour, the image of the soul; white, the image of the spirit. If we wish to have the adjective, we must start from the previous, thus: Black is the spiritual image of the lifeless; Green is the lifeless image of life; Peach-blossom colour is the living image of the soul; White is the psychic image of the spirit.

In this circle we can indicate certain fundamental colours, Black, White, Green and Peach-blossom colour, while always the previous word indicates the adjective for the next one; Black is the spiritual image of the Lifeless; Green is the lifeless image of the Living; Peach-blossom colour is the living image of the Soul; White is the psychic image of the Spirit.

If we take the kingdoms of Nature in this way—the lifeless kingdom, the living kingdom, the ensouled kingdom, the spiritual kingdom, we ascent—precisely as we ascend from the lifeless to the living, to the ensouled, to that possessing spirit—from black to green, to peach-blossom colour, white. As truly as I can ascend from the lifeless, through the living, to the psychic, to the spiritual as truly as I have there the world which surrounds me, so truly have I the world around me in its images when I ascend from black to green, peach-blossom colour, white. As truly as Constantine, Ferdinand, Felix, etc. are the real ancestors, and I can ascend through this ancestral line, so truly can I go through these portraits and have the portraits of this line of ancestry. I have before me a world; the mineral, plant, animal and spiritual kingdom—in as far as man is the spiritual. I ascent through the realities; but Nature gives me only the images of these realities. Nature is reflected. The world of colour is not a reality; even in nature itself it is only image; the image of the lifeless is black; that of the living is green; that of the psychic, peach-blossom colour; and the image of the spirit is white.

This leads us to the objective nature of colour. This we had to set forth today, since we wish to penetrate further into the nature, the peculiar feature of colour; for it avails us nothing to say that colour is a subjective impression. That is a matter of absolute indifference to colour. To green it is immaterial whether we pass by and stare at it; but it is not a matter of indifference that, if the living gives itself its own colour, if it is not tinged by the mineral and appears coloured in the flower, etc., if the living appear in its own colour, it must image itself outwardly as green. That is something objective. Whether or not we gaze at it, it is entirely subjective. The living, however, if it appear as a living being, must appear green, it must image itself in green; that is something objective.

Das Wesen der Farben I

Das Farberlebnis — Die vier Bildfarben

Die Farben, von denen wir in diesen drei Tagen sprechen wollen, sie beschäftigen den Physiker - von dieser Seite der Farben wollen wir diesmal nicht sprechen -, sie beschäftigen aber auch, oder sollten wenigstens beschäftigen, den Psychologen, den Seelenforscher, und sie müssen ja vor allen Dingen beschäftigen den Künstler, den Maler. Und wenn wir uns umsehen in den Anschauungen, die sich bis in die Gegenwart herein über die Farbenwelt gebildet haben, so werden wir etwa konstatieren müssen, daß zwar dem Seelenforscher zugestanden wird, daß er dies oder jenes über die subjektiven Erlebnisse mit den Farben zu sagen habe, daß aber das doch keine eigentliche Bedeutung haben könne für die Erkenntnis des Objektiven der Farbenwelt, welche Erkenntnis eigentlich nur dem Physiker zukomme. Und erst recht gesteht man der Kunst nicht zu, irgend etwas über das Wesen der Farben und des Farbigen im objektiven Sinne zu entscheiden. Die Menschen sind eben gegenwärtig weit, weit weg von dem, was Goethe etwa meinte mit dem oftmals zitierten Ausspruche: «Wem die Natur ihr offenbares Geheimnis zu enthüllen anfängt, der empfindet eine unwiderstehliche Sehnsucht nach ihrer würdigsten Auslegerin, der Kunst.»

Einem Menschen, der nun wirklich im Künstlerischen drinnensteht wie Goethe, kann es keinen Augenblick zweifelhaft sein, daß dasjenige, was der Künstler über die Farbenwelt zu sagen hat, durchaus mit dem Wesen des Farbigen zusammenhängen müsse. Man behandelt das Farbige ja zunächst im gewöhnlichen trivalen Leben nach den Oberflächen der Gegenstände, die sich uns als farbig darstellen, nach den Eindrükken, die wir in der Natur vom Farbigen haben. Man gelangt dann dazu, das Farbige in einem gewissen Sinne, ich möchte sagen fluktuierend, durch den bekannten prismatischen Versuch zu erhalten, und man verschafft sich oder sucht sich zu verschaffen auf manche andere Art noch irgendwelche Einblicke in die Welt des Farbigen. Man hat eigentlich dabei immer im Auge, daß man das Farbige zunächst nach dem subjektiven Eindruck beurteilen soll. Sie wissen, eine lange Zeit war es in der Physik Sitte, man könnte auch sagen Unsitte, zu sagen: Was wir als eine farbige Welt wahrnehmen, das ist eigentlich nur für unsere Sinne vorhanden, während draußen in der Welt die objektive Farbe nichts anderes darstelle als eine gewisse Wellenbewegung des feinsten Stoffes, den man Äther nennt.

Wer allerdings sich unter den Definitionen, den Erklärungen, die auf diese Weise gegeben werden, auch etwas vorstellen will, der kann nichts anfangen mit einem solchen Begriff, daß dasjenige, was er als den Farbeindruck kennt, was er als Farbeindruck als sein Erlebnis hat, irgend etwas zu tun haben soll mit irgendeinem bewegten Äther. Aber man hat eben immer nur, wenn man von der Farbe, von der Qualität der Farbe spricht, den subjektiven Eindruck im Auge, und man sucht nach irgend etwas Objektivem. Dann aber kommt man ganz von der Farbe ab. Denn in all den Ätherschwingungen, die da ersonnen werden ersonnen sind sie ja in Wirklichkeit -, liegt natürlich nichts mehr von dem, was unsere farbige Welt ist. Und man muß, gerade wenn man in das Objektive der Farben hineinkommen will, versuchen, sich an die Welt der Farben selbst zu halten. Man muß versuchen, nicht herauszugehen aus der Welt des Farbigen. Dann kann man hoffen, einzudringen in dasjenige, was eigentlich das Wesen der Farbe ist.

Wollen wir einmal versuchen, uns zu vertiefen in etwas, was uns von der ganzen weiten, mannigfaltigen Welt durch die Farbe gegeben sein kann. Und da wir eindringen wollen in das Wesen des Farbigen, so müssen wir schon, da wir ja bei der Farbe etwas empfinden, gewissermaßen die ganze Betrachtung heraufheben in unser Empfindungsleben. Wir müssen versuchen, unser Empfindungsleben zu fragen über dasjenige, was als Farbiges in unserer Umwelt lebt. Und wir werden am besten in einem gewissen Sinne ideell experimentierend zunächst vorgehen, damit wir nicht nur die im allgemeinen ja schwierig zu analysierenden, gegebenen Vorgänge haben, die sich uns nicht so eklatant, nicht so radikal zeigen, daß wir gleich auf das Wesentliche kommen.

Nehmen Sie einmal an, ich würde versuchen, vor Sie hinzumalen auf die Fläche eine Grünheit, also ich würde die Fläche bedecken mit einer grünen Farbe. Nun, wenn ich das tue, so würde also eine Fläche dann irgendwie mit einer grünen Farbe bedeckt erscheinen. Ich bitte Sie, hier abzusehen von demjenigen, was sich nicht ergeben kann — man malt ja gewöhnlich nicht grün auf schwarz. Ich will aber nur das Schematische Ihnen hier vorführen. [Es wird gezeichnet.]

Wenn wir einfach aus der Farbe heraus uns empfindungsgemäß anregen lassen, können wir irgend etwas, was wir weiter gar nicht zu definieren brauchen, an dem Grün als solchem erleben. Und niemand wird jetzt im Zweifel darüber sein, daß wir dasselbe, was wir an einem solchen Grün erleben können, natürlich auch erleben müssen, wenn wir die grüne Pflanzendecke der Erde uns anschauen. Wir werden das, was wir an dem reinen Grün erleben, auch an der Pflanzendecke der Erde dadurch erleben, daß diese Pflanzendecke eben grün ist. Wir müssen absehen von allem übrigen, was sonst uns diese Pflanzendecke noch darbietet, wir wollen nur auf die Grünheit sehen. Und nehmen wir jetzt an, ich stelle mir vor das Seelenauge diese Grünheit.

Wenn ich in diese Grünheit nun etwas hineinmale, so kann ich das mit den verschiedensten Farben hineinmalen. Wir wollen uns einmal drei Farben vor das Auge führen.

Ich habe also hier eine Grünheit, hier die zweite Grünheit, hier die dritte Grünheit. Stellen Sie sich nun vor, ich male hier ins erste irgendwie hinein in die Grünheit ein Rotes; ich male im zweiten Fall in die Grünheit hinein eine Art Pfirsichblütfarbe — nun, ich habe sie nicht, aber nehmen wir das -, und ich male zum dritten hinein ein Blaues.

Sie werden nun zugeben müssen, daß rein empfindungsgemäß durch dasjenige, was ich da getan habe, in den drei Fällen etwas ganz Verschiedenes geschehen ist, und daß ein gewisser Empfindungsgehalt da ist, wenn ich diese rote Form, oder was es immer ist, im Grünen drinnen wiedergebe, oder die pfirsichblütigeForm indem Grünen drinnen wiedergebe, oder gar die blaue Form in dem Grünen drinnen wiedergebe. Es wird sich nun darum handeln, daß wir in irgendeiner Weise ausdrücken den Empfindungsgehalt, der sich uns da vor das Seelenauge hinstellt.

Wenn man so etwas ausdrücken will, so wird man versuchen müssen, es irgendwie zu umschreiben, denn man wird natürlich mit abstrakten Definitionen außerordentlich wenig erreichen können. Nun, damit wir zu einer Umschreibung kommen, versuchen wir einfach etwas hineinzuphantasieren in dasjenige, was wir uns da vorgemalt haben. Nehmen wir einmal an, ich hätte im ersten Falle wirklich die Empfindung erregen wollen einer grünen Pflanzendecke, und ich zeichne rote Menschen hinein. Ob ich diese nun im Antlitz rot mache und der Haut nach rot mache, oder ob ich sie rot ankleide, das ist ja ganz gleich. Hier [in das erste Grün] male ich rote Menschen hinein, hier in das zweite Grün male ich pfirsichblütige Menschen hinein — was ungefähr mit dem menschlichen Inkarnat stimmen würde —, und hier [in das dritte Grün] male ich blaue Menschen hinein. So daß ich also dieses jetzt nicht mache, um irgend etwas der Natur nachzubilden, sondern nur, um mir einen Empfindungskomplex vor die Augen führen zu können von dem, was da eigentlich vorliegt.

Stellen Sie sich einmal vor, Sie hätten diesen Anblick: über eine grüne Wiese gingen rote Menschen, oder über eine grüne Wiese gingen pfirsichblütige Menschen, oder es gingen gar blaue Menschen über die grüne Wiese — in allen drei Fällen ein durch und durch verschiedener Empfindungskomplex! Wenn Sie das erste sehen, dann werden Sie sich sagen: Diese roten Menschen, die ich da drinnen sehe in dem Grün, auf der grünen Wiese, die beleben mir die ganze grüne Wiese. Die Wiese ist noch grüner dadurch, daß die roten Menschen darübergehen. Es wird das Grün noch gesättigter, noch lebendiger dadurch, daß die roten Menschen da drinnen gehen. Und ich werde wütend werden, wenn ich mir diese Menschen so anschaue, wie sie da sind als rote Menschen. Das ist eigentlich ein Unsinn, werde ich sagen, das kann es gar nicht geben. Ich müßte eigentlich diese roten Menschen wie Blitze machen; sie müßten sich bewegen. Denn ruhige rote Menschen in einer grünen Wiese, die wirken aufregend in ihrer Ruhe, denn sie bewegen schon durch ihre rote Farbe, sie verursachen etwas auf der Wiese, was eigentlich unmöglich ist, in der Ruhe festzuhalten. Also, ich muß in ganz bestimmte Empfindungskomplexe hineinkommen, wenn ich eine solche Vorstellung überhaupt vollziehen will.

Das [beim zweiten Grün] geht ganz gut. Die Menschen, die so sind wie diese Pfirsichblütigen, die können [ruhig] da drinnenstehen; wenn sie stundenlang stehen, so geniert mich das weiter nicht. So daß ich in meiner Empfindung merke: Diese pfirsichblütigen Menschen, die haben eigentlich kein besonderes Verhältnis zur Wiese, sie regen die Wiese nicht auf, machen sie nicht noch grüner, als sie ist, sind ganz neutral zur Wiese. Sie können stehen wo sie wollen, sie genieren mich nicht da drinnen. Sie taugen überall hinzu. Sie haben kein inneres Verhältnis zur grünen Wiese.

Ich gehe zum dritten über: Ich sehe mir die blauen Menschen in der grünen Wiese an. Das [Blaue], nicht wahr, das hält nicht einmal an; das hält gar nicht an. Denn dieses Blaue der Menschen in der grünen Wiese, das dämpft mir diese ganze grüne Wiese ab. Die Wiese wird abgelähmt in ihrer Grünheit. Sie bleibt gar nicht grün. Versuchen Sie es nur einmal, sich in richtiger Phantasie vorzustellen, auf einer grünen Wiese blaue Menschen herumgehend oder überhaupt blaue Wesen — es können ja auch blaue Geister sein, die da herumwandeln -, versuchen Sie das einmal: sie hört ja auf, grün zu sein, sie nimmt selber etwas Bläulichkeit an, wird selber bläulich, hört auf, grün zu sein. Und wenn sich diese blauen Menschen da lange auf dem Grün aufhalten, dann kann ich mir das überhaupt gar nicht mehr vorstellen. Dann habe ich die Vorstellung: da muß irgendwo ein Abgrund sein, und die blauen Menschen nehmen mir die Wiese weg, tragen sie fort, werfen sie in den Abgrund hinein. Das geht so wenig, daß es gar nicht dableiben kann, denn eine grüne Wiese kann gar nicht dableiben, wenn blaue Menschen dastehen; die nehmen sie mit, die führen sie hinweg.

Sehen Sie, das ist Farbenerlebnis. Man muß dieses Farbenerlebnis haben können, sonst wird man nichts machen können aus dem, was die Welt der Farben überhaupt ist. Wenn man das kennenlernen will, was seine schönste, seine bedeutsamste Anwendung in der Phantasie erlebt, dann muß man auch in der Lage sein, ich möchte sagen, im Bereiche der Phantasie eben zu experimentieren. Man muß sich fragen können: Was wird aus einer grünen Wiese, wenn rote Menschen darauf herumgehen? — Sie wird noch grüner, sie wird ganz real in ihrer Grünheit. Das Grün fängt förmlich an zu brennen. Aber die roten Menschen, sie verursachen um sich herum ein solches Leben in der Grünheit, daß ich mir das nicht ruhig vorstellen kann; sie müssen eigentlich herumlaufen. Und würde ich das Bild wirklich malen, so könnte ich nicht ruhige Leute, die dastehen, rot malen, sondern ich müßte so malen, daß ich... [Lücke im Text]. Wie im Reigen bewegen sie sich. Ein Reigen mit roten Menschen gemalt, würde sich auf einer grünen Wiese machen lassen. Dagegen können Menschen, die nicht rot angezogen sind, die ganz sich in das Inkarnat kleiden würden, in alle Ewigkeit auf der grünen Wiese stehen. Sie sind eben ganz und gar neutral zum Grün, sind absolut gleichgültig der grünen Wiese; die bleibt, wie sie ist. Nicht um die geringste Nuance ändert sie sich. Aber die blauen Menschen, die laufen mir mit der Wiese davon, denn die ganze Wiese verliert ihre Grünheit durch die blauen Menschen.

Man muß natürlich vergleichsweise reden, wenn man von Farbenerlebnissen spricht. Man kann nicht wie der Philister von Farbenerlebnissen reden, denn da kommt man nicht an das Farbenerlebnis heran. Man muß vergleichsweise reden. Aber nicht wahr, schließlich redet ja schon der gewöhnliche Philister vergleichsweise, wenn er sagt: eine Billardkugel stößt die andere. — Hirsche stoßen, und Ochsen und Büffel stoßen in Wirklichkeit, aber Billardkugeln stoßen nicht in Wirklichkeit. Dennoc spricht man in der Physik von «Stoßen», weil man überall analoge Anlehnungen braucht, wenn man überhaupt anfangen will zu reden.

Nun, das gibt uns sozusagen die Möglichkeit, in der Welt der Farbe als solcher etwas zu sehen. Es ist etwas drinnen, was wir werden aufsuchen müssen als das Wesen der Farbe.

Nehmen wir einmal eine ganz charakteristische Farbe — wir haben sie hier schon ins Auge gefaßt —, nehmen wir eben die Farbe, die uns in unserer Umgebung zur Sommerszeit am reizvollsten entgegenkommt: die grüne Farbe. Sie kommt uns an der Pflanze entgegen. Und wir sind schon einmal gewöhnt, dieses Grün der Pflanze als Eigentümlichkeit der Pflanze anzusehen. Nicht wahr, so verbunden mit dem Wesen einer Sache wie die Grünheit mit der Pflanze, empfinden wir eigentlich etwas anderes nicht. Wir empfinden keine Notwendigkeit, daß gewisse Tiere, die grün sind, auch wirklich nur grün sein könnten; wir haben immer den Untergedanken, sie könnten auch anders als grün sein. Aber bei der Pflanze haben wir einmal die Vorstellung, daß die Grünheit zu ihr gehört, daß die Grünheit etwas ihr Eigentümliches ist. Versuchen wir gerade an der Pflanze einmal einzudringen in das objektive Wesen der Farbe, währenddem sonst nur das subjektive Wesen der Farbe gesucht wird.

Was ist die Pflanze, die uns also gewissermaßen darlebt das Grüne? Nun, Sie wissen ja, daß geisteswissenschaftlich betrachtet, die Pflanze ihren Bestand eigentlich dadurch hat, daß sie neben ihrem physischen Leib den Ätherleib hat. Dieser Ätherleib ist dasjenige, was eigentlich lebt in der Pflanze. Aber dieser Atherleib ist nicht grün. Das Wesen, das die Pflanze grün macht, ist eben schon im physischen Leib der Pflanze gelegen, so daß das Grün zwar der Pflanze ureigentümlich ist, aber doch nicht das eigentliche Urwesen der Pflanze ausmachen kann. Denn das eigentliche Urwesen der Pflanze liegt im Ätherleib; und hätte die Pflanze keinen Ätherleib, so wäre sie ein Mineral. In ihrem Mineralischen lebt sich uns die Pflanze eigentlich dar durch das Grün. Der Atherleib ist ganz anders gefärbt. Aber der Ätherleib lebt sich uns durch das mineralisch Grüne an der Pflanze dar. Wenn wir in bezug auf den Ätherleib die Pflanze betrachten, wenn wir sie in ihrer Grünheit in bezug auf den Ätherleib betrachten, ja, dann müssen wir sagen: Setzen wir auf die eine Seite das eigentliche Wesen der Pflanze, das Ätherische, und setzen wir auf die andere Seite, indem wir es in abstracto abtrennen, die Grünheit, so ist das wirklich so - wenn wir die Grünheit herausnehmen aus der Pflanze -, als wenn wir bloß ein Abbild von etwas machen. In dem, was ich da als Grünes herausgezogen habe aus dem Atherischen, habe ich eigentlich nur ein Bild der Pflanze, und dieses Bild ist - das ist der Pflanze eigentümlich — notwendig grün. Also, ich bekomme eigentlich die Grünheit im Bilde der Pflanze. Und indem ich der Pflanze die grüne Farbe ganz wesentlich zuschreibe, muß ich dem Bilde der Pflanze diese Grünheit zuschreiben, und in der Grünheit muß ich das besondere Wesen des Pflanzenbildes suchen.

Sehen Sie, da sind wir auf etwas sehr Wesentliches gekommen. Niemand wird verfehlen, wenn er irgendwo eine Ahnengalerie sieht in einem alten Schlosse - man kann sie ja jetzt vorläufig noch sehen -, zu sagen: Das sind nur die Bilder der Ahnen, das sind nicht die wirklichen Ahnen. - Nicht wahr, sie stehen in der Regel nicht da, die Ahnen; es sind nur die Bilder der Ahnen. Aber auch wenn wir das Grün der Pflanze sehen, so haben wir nicht das Wesen der Pflanze, geradesowenig wie wir in den Ahnenbildern die Ahnen haben. Wir haben in dem Grün, was da vor uns auftritt, nur das Bild der Pflanze. Und nun bedenken Sie einmal, daß die Grünheit eben der Pflanze eigentümlich ist, daß die Pflanze unter allen Wesen eben das eigentliche Wesen des Lebens ist. Nicht wahr, das Tier hat Seele, der Mensch hat Geist und Seele. Die Mineralien haben kein Leben. Die Pflanze ist das Wesen, welches gerade dadurch charakteristisch ist, daß es Leben hat. Die Tiere haben noch dazu die Seele. Die Mineralien haben noch nicht die Seele. Der Mensch hat dazu den Geist. Wir können weder vom Menschen, noch vom Tier, noch vom Mineral sagen, daß sein Wesen das Leben ist; es ist eben etwas anderes das Wesen. Bei der Pflanze ist das Wesen das Leben; die grüne Farbe ist das Bild. So daß ich eigentlich ganz im Objektiven drinnenbleibe, wenn ich sage:

Grün stellt dar das tote Bild des Lebens.

Sehen Sie, jetzt habe ich auf einmal für eine Farbe - wir wollen induktiv vorgehen, wenn wir uns gelehrt ausdrücken wollen - so etwas bekommen, wodurch ich diese Farbe objektiv in die Welt hineinstellen kann. Ich kann sagen, geradeso wie ich, wenn ich eine Photographie bekomme, sagen kann, diese Photographie ist die von Herrn N., geradeso kann ich auch sagen: Wenn ich Grün habe, so stellt mir das Grün das tote Bild des Lebens dar. Ich reflektiere jetzt nicht bloß auf den subjektiven Eindruck, sondern ich komme darauf, daß das Grün das tote Bild des Lebens ist.

Nehmen wir diese Farbe hier, das Pfirsichblüt. Genauer will ich lieber sprechen von der Farbe des menschlichen Inkarnates, das ja natürlich bei den verschiedenen Menschen nicht ganz gleich ist, aber wir kommen da zu einer Farbe, die ich eigentlich im Grunde meine, wenn ich von Pfirsichblüt spreche .... [Lücke ich Text]. Pfirsichblüt: also menschliches Inkarnat, menschliche Hautfarbe. Wir wollen einmal versuchen, auf das Wesen dieser menschlichen Hautfarbe zu kommen. Man sieht ja diese menschliche Hautfarbe gewöhnlich nur von außen. Man sieht den Menschen an, und dann sieht man diese menschliche Hautfarbe von außen. Aber es frägt sich, ob auch ein Bewußtsein von dieser menschlichen Hautfarbe als ein Erkennen von innen, so ähnlich, wie wir das bei dem Grün der Pflanze getan haben, erlangt werden kann. Nun, das kann allerdings auf die folgende Weise erlangt werden.

Wenn der Mensch wirklich richtig versucht, sich vorzustellen, daß er innerlich durchseelt ist und dieses sein Durchseeltsein übergehend denkt in seine physisch-leibliche Gestaltung, so kann er sich vorstellen, daß das, was ihn durchseelt, sich in irgendeiner Weise in die Gestaltung hinein ergießt. Er lebt sich aus, indem er sein Seelisches hineinergießt in seine Gestalt, in dem Inkarnat. Was damit gesagt ist, können Sie sich am besten vielleicht dadurch vor die Seele führen, daß Sie sich einmal Menschen anschauen, bei denen das Seelische aus der Haut, aus der äußeren Gestalt etwas zurücktritt, bei denen das Seelische nicht, sagen wir, durchseelt die Gestalt. Wie werden denn diese Menschen? Die werden grün! Leben ist in ihnen, aber sie werden grün. Sie sprechen von grünen Menschen, und Sie können dieses eigentümliche Grün im Teint, wenn die Seele sich zurückzieht, sehr gut wahrnehmen. Dagegen werden Sie, je mehr der Mensch diese besondere Nuance des Rötlichen annimmt, das Erleben dieser Nuance in ihm merken. Beobachten Sie nur einmal Temperament, Humor bei grünen Menschen und bei denjenigen, die ein wirklich frisches Inkarnat haben, so werden Sie sehen, da erlebt sich die Seele in dem Inkarnat. Was da nach außen strahlt in dem Inkarnat, das ist nichts anderes als der sich als Seele in sich erlebende Mensch. Und wir können sagen: Was wir da im Inkarnat als Farbe vor uns haben, es ist das Bild der Seele, richtig das Bild der Seele. Aber gehen Sie [noch so] weit in der Welt herum, [Sie werden finden]: für dasjenige, was als menschliches Inkarnat auftritt, müssen wir das Pfirsichblüt wählen. Sonst finden wir es ja eigentlich nicht an äußeren Gegenständen. Wir können es ja auch nur durch alle möglichen Kunstgriffe in der Malerei erreichen; [denn] dasjenige, was da als menschliches Inkarnat auftritt, ist schon Bild des Seelischen, aber es ist, daran kann ja gar kein Zweifel sein, nicht selber seelisch. Es ist das lebendige Bild der Seele. Die Seele, die sich erlebt, erlebt sich im Inkarnat. Es ist nicht tot, wie das Grün der Pflanze, denn wenn der Mensch die Seele zurückzieht, so wird er grün: dann kommt er bis zum Toten. Aber ich habe in dem Inkarnat das Lebendige. Also:

Pfirsichblüt stellt dar das lebendige Bild der Seele.

Wir haben also Bild im ersten und Bild im zweiten Falle.

Sie sehen, ich bin zu einer anderen Farbe gegangen. Wir versuchen objektiv das Farbige festzuhalten, nicht bloß den subjektiven Eindruck zu erwägen und dann irgendwelche Wellenbewegungen und so weiter zu erfinden, die dann objektiv sein sollen. Man kann es ja, ich möchte sagen, mit Händen greifen, daß es ein Unding ist, das menschliche Erleben von dem Inkarnat zu trennen. Es ist ein anderes Erleben im Leiblichen, wenn das Inkarnat frisch ist, als wenn der Mensch ein Grünling wird. Es ist schon ein innerliches Wesen, das sich in der Farbe wirklich darlebt.

Und nun nehmen wir dasjenige, was wir hier als drittes gehabt haben, das Blau, dann werden wir uns sagen: Dieses Blau können wir zunächst nicht eigentümlich finden einem solchen Wesen, wie es die Pflanze ist, der das Grün eigentümlich ist; wir können nicht so über das Blau sprechen, wie wir sprechen konnten über das pfirsichblütartige Inkarnat beim Menschen. Bei den Tieren finden wir nicht solche Farben, die so ureigentümlich sind den Tieren, wie die Menschen und die Pflanzen ureigentümlich haben Inkarnat und Grünheit. Also mit dem Blau können wir zunächst nicht in dieser Weise der Natur gegenüber etwas anfangen. Aber wir wollen doch vorschreiten, wir wollen doch einmal sehen, ob wir vielleicht noch weiter im Aufsuchen des Wesens der Farbe kommen können.

Wir haben zunächst die Möglichkeit, da wir über das Blau nicht gehen können, zu den hellen Farben hinzugehen; aber damit wir leichter, schneller vorwärtskommen, nehmen wir gerade dasjenige, was uns bekannt ist als das Weiß. Wir können zunächst nicht sagen, daß irgendeinem Wesen der Außenwelt dieses Weiß eigentümlich ist. Wir könnten uns ja an das Mineralreich wenden, aber wir wollen doch versuchen, uns auf eine andere Weise von dem Weißen eine objektive Vorstellung zu machen. Und da können wir sagen: Wenn wir das Weiße vor uns haben und es dem Lichte aussetzen, wenn wir das Weiße einfach beleuchten, so haben wir die Empfindung: dieses Weiße hat eine gewisse Verwandtschaft zum Lichte. Aber das bleibt zunächst eine Empfindung. Es wird aber in dem Augenblicke mehr als eine Empfindung, wenn wir uns an die Sonne halten, die uns zunächst ja deutlich wenigstens gegen das Weiß hin nuanciert erscheint, und auf die wir zurückführen müssen alles, was Beleuchtung ist in unserer Welt zunächst von der Natur aus. Wir können sagen: Was uns als Sonne erscheint, was sich als Weißes darlebt, was aber zugleicher Zeitseine innere Verwandtschaftmitdem Lichte darlebt, das hat die Eigentümlichkeit, daß es uns überhaupt durch sich selber nicht auf dieselbe Art wie eine äußere Farbe erscheint. Eine äußere Farbe erscheint uns an den Dingen. Und so etwas wie die Weiße der Sonne, welche uns das Licht repräsentiert, erscheint uns nicht unmittelbar an den Dingen. Wir werden später eingehen auf jene Art von Farbe, die man etwa an Papier und Kreide und dergleichen als weiß bezeichnen kann, aber da werden wir eben einen Umweg machen müssen. Zunächst, wenn wir uns ans Weiße heranwagen, so müssen wir sagen: Wir werden zunächst durch das Weiße zum Lichte als solchem geführt. Wir brauchen ja, um diese Empfindungen ganz auszubilden, nichts anderes zu tun, als etwa uns zu sagen: Das polarische Gegenbild des Weißen ist das Schwarze.

Daß das Schwarze die Dunkelheit ist, daran zweifeln wir nicht mehr; so werden wir das Weiße sehr leicht identifizieren können mit der Helligkeit, mit dem Lichte als solchem. Kurz, wir werden schon, wenn wir die ganze Betrachtung in das Empfindungsgemäße heraufheben, die innige Beziehung des Weißen und des Lichtes finden. Wir werden auf die Frage dann noch näher eingehen in den nächsten Tagen.

Wenn wir nun über das Licht selber nachdenken, und wenn wir nicht versucht sind, an den Newton-Popanz uns zu halten, sondern wenn wir die Dinge unbefangen beobachten, so werden wir uns sagen: Farben sehen wir schon. Zwischen der Weiße, die als Farbe auftritt, und dem Licht muß es eine besondere Bewandtnis haben. Wir wollen also das eigentliche Weiß zunächst ausschalten. Aber anders als von den anderen Farben wissen wir vom Lichte als solchem. Fragen Sie sich einmal, ob Sie das Licht eigentlich wahrnehmen. Sie würden ja gar nicht Farben wahrnehmen, wenn Sie nicht im durchleuchteten Raume wären. Das Licht macht Ihnen die Farben wahrnehmbar; aber Sie können nicht sagen, daß Sie das Licht ebenso wahrnehmen wie die Farben. Das Licht ist ja in dem Raume, wo Sie eine Farbe wahrnehmen. Es liegt in dem Wesen des Lichtes, die Farben wahrnehmbar zu machen. Aber nicht so, wie wir das Rot, Gelb, Blau sehen, sehen wir das Licht. Das Licht ist überall, wo es hell ist, aber wir sehen nicht das Licht. Es muß das Licht überall fixiert sein an etwas, wenn wir es sehen sollen. Es muß behalten werden, es muß zurückgeworfen werden. Die Farbe ist an der Oberfläche der Dinge, das Licht aber - wir können nicht sagen, daß es irgendwo haftet —, das Licht ist etwas durch und durch Fluktuierendes. Aber wir selbst, wenn wir des Morgens aufwachen und vom Lichte durchstrahlt und überstrahlt werden, dann fühlen wir uns in unserem eigentlichen Wesen, wir fühlen eine innige Verwandtschaft des Lichtes mit unserem eigentlichen Wesen. Und wenn wir in der Nacht in tiefer Finsternis aufwachen, fühlen wir: Da können wir nicht zu unserem eigentlichen Wesen kommen, da sind wir wohl gewissermaßen in uns zurückgezogen, aber wir sind durch die Verhältnisse etwas geworden, was sich selber nicht in seinem Elemente fühlt. Und wir wissen auch: Das, was wir vom Lichte haben, es ist ein Zu-uns-Kommen. Es widerspricht dem nicht, daß der Blinde es nicht hat. Er ist dafür organisiert, und auf die Organisation kommt es an. Wir haben zum Lichte das Verhältnis, das unser Ich zur Welt hat, aber doch wieder nicht dasselbe; denn wir können nicht sagen, daß dadurch, daß das Licht uns erfüllt, wir schon zum Ich kommen. Aber dennoch, das Licht ist notwendig, damit wir zu diesem Ich kommen, wenn wir sehende Wesen sind.

Was liegt da eigentlich vor? Wir haben in dem Lichte, von dem wir gesagt haben, daß es sich im Weiß hinstellt — wie gesagt, die innere Beziehung wollen wir dann noch kennenlernen -, dasjenige, was uns eigentlich durchgeistigt, was uns zu unserem eigenen Geiste bringt. Es hängt unser Ich, daß heißt, unser Geistiges, mit diesem Durchleuchtetsein zusammen. Und wenn wir diese Empfindung nehmen - es muß eben alles, was im Licht und in der Farbe lebt, als Empfindung zunächst gefaßt werden —, so werden wir sagen: Es ist ein Unterschied zwischen dem Lichte und demjenigen, was sich im Ich als Geist darlebt. Und dennoch, es gibt uns das Licht etwas von unserem eigenen Geiste. - Wir werden in einer solchen Weise durch das Licht ein Erlebnis haben, daß das Ich sich eigentlich innerlich erleben kann am Lichte.

Wenn wir das alles zusammenfassen, so können wir nicht anders sagen als: Das Ich ist geistig, es muß sich aber seelisch erleben; es erlebt sich seelisch, indem es sich durchleuchtet fühlt. Und das jetzt in eine Formel gefaßt, werden Sie sehen:

Weiß oder Licht stellt dar das seelische Bild des Geistes.

Es ist natürlich, daß ich Ihnen diese dritte Stufe aus lauter Empfindung habe zusammensetzen müssen. Aber versuchen Sie, nachdem diese Formel jetzt gewonnen ist, sich immer mehr und mehr hineinzudenken in die Sache und Sie werden sehen, es liegt wirklich etwas in dem:

Grün stellt dar das tote Bild des Lebens,

Pfirischblüt stellt dar das lebende oder lebendige Bild der Seele,

Weiß oder das Licht stellt dar das seelische Bild des Geistes.

Und jetzt gehen wir zum Schwarz oder zur Finsternis. Da werden Sie schon verstehen, daß ich vom Weißen und vom Hellen, vom Lichte sprechen kann im Zusammenhange mit der Beziehung, die besteht zwischen der Finsternis und dem Schwarzen. Nehmen wir also jetzt das Schwarz. Ja, und nun versuchen Sie einmal mit dem Schwarzen, mit der Finsternis etwas anzufangen! Sie können etwas anfangen. Es ist ja zweifellos das Schwarze sehr leicht sogar in der Natur zu finden, so als eine Eigentümlichkeit, als eine wesenhafte Eigentümlichkeit von etwas, wie das Grüne eine wesenhafte Eigenheit ist von der Pflanze. Sie brauchen nur die Kohle sich anzusehen. Und um sich noch erhöht das vorzustellen, daß da das Schwarze irgend etwas mit der Kohle zu tun hat, stellen Sie sich vor, daß die Kohle auch ganz hell und durchsichtig sein kann: dann ist sie allerdings ein Demant. Aber so bedeutsam ist das Schwarz für die Kohle, daß, wenn sie nicht schwarz wäre, sondern weiß und durchsichtig, sie ein Demant wäre. So stark wesenhaft ist das Schwarz für die Kohle, daß eigentlich die Kohle ihr ganzes Kohlendasein der Schwärze verdankt. Also die Kohle verdankt ihr finsteres, schwarzes Kohlendasein eben der schwarzen Finsternis, in der sie erscheint. Geradeso wie die Pflanze ihr Bild irgendwie hat in dem Grünen, so hat die Kohle ihr Bild in dem Schwarzen.

Aber versetzen Sie sich selbst jetzt in das Schwarze: Alles ist absolut schwarz um Sie herum - die schwarze Finsternis —, da kann in einer schwarzen Finsternis ein physisches Wesen nichts machen. Leben wird aus der Pflanze vertrieben, indem sie zur Kohle wird. Also das Schwarze zeigt schon, daß es dem Leben fremd ist, daß es dem Leben feindlich ist. An der Kohle zeigt sich das; denn die Pflanze, indem sie verkohlt, wird schwarz. Also Leben? Da ist nichts zu machen im Schwarzen. Seele? Es vergeht uns die Seele, wenn das grausige Schwarz in uns ist. Aber der Geist blüht, der Geist kann durchdringen dieses Schwarze, der Geist kann sich da drinnen geltend machen.

Und wir können sagen: Im Schwarzen — und versuchen Sie es nur einmal, die Schwarz-Weiß-Kunst, das Hell-Dunkel auf der Fläche daraufhin zu prüfen, wir werden darauf noch zurückkommen -, da bringen Sie eigentlich, indem Sie auf die weiße Fläche das Schwarz daraufmalen, den Geist in diese weiße Fläche hinein. Gerade in dem schwarzen Strich, in der schwarzen Fläche durchgeistigen Sie das Weiße. Den Geist können Sie in das Schwarz hineinbringen. Aber es ist das einzige, was in das Schwarz hineingebracht werden kann. Und dadurch bekommen Sie die Formel:

Schwarz stellt dar das geistige Bild des Toten.

Wir haben jetzt einen merkwürdigen Kreislauf bekommen für die objektive Wesenheit der Farben. Wenn wir uns den Kreislauf darstellen, haben wir immer in der Farbe irgendwie ein Bild. Farbe ist unter allen Umständen nichts Reales, sondern Bild. Und wir haben einmal das Bild des Toten, einmal das Bild des Lebens, das Bild der Seele, das Bild des Geistes [siehe Zeichnung]. Wir bekommen also, indem wir so herumgehen: Schwarz, das Bild des Toten; Grün, das Bild des Lebens; Pfrsichblüt, das Bild der Seele; Weiß, das Bild des Geistes. Und will ich das Eigenschaftswort dazu haben, das Adjektiv, dann muß ich immer von dem Vorhergehenden ausgehen: Schwarz ist das geistige Tate Bild des Toten; Grün ist das tote Bild des Lebens; Pfirsichblüt ist das lebende Bild der Seele; Weiß ist das seelische Bild des Geistes.

Ich bekomme in diesem Zirkel, in diesem Kreise die Möglichkeit, auf gewisse Grundfärbungen, Schwarz, Weiß, Grün und Pfirsichblüt, hinzuweisen, indem immer das Frühere mir das Eigenschaftswort für das Spätere andeutet: Schwarz ist das geistige Bild des Toten; Grün ist das tote Bild des Lebenden; Pfirsichblüt ist das lebende Bild der Seele; Weiß ist das seelische Bild des Geistes.

Wenn ich also die Reiche der Natur nehme, das tote Reich, das lebende Reich, das beseelte Reich, das geistige Reich, dann steige ich auf — geradeso wie ich aufsteige vom Toten zum Lebenden, zum Seelischen, zum Geistigen -, so steige ich auf: Schwarz, Grün, Pfirsichblüt, Weiß. Sie sehen, so wahr ich aufsteigen kann vom Toten durch das Leben zum Seelischen, zum Geistigen, so wahr ich da die Welt habe, die um mich herum ist, so wahr habe ich diese Welt um mich herum in ihren Bildern, indem ich aufsteige: Schwarz, Grün, Pfirsichblüt, Weiß. Wirklich, so wahr es ist, daß der Konstantin und der Ferdinand und der Felix und so weiter die wirklichen Ahnen sind und ich aufsteigen kann durch diese Ahnenreihe, so wahr kann ich durch die Bilder weitergehen und habe die Bilder dieser Ahnenreihe. Ich habe eine Welt vor mir: mineralisches, pflanzliches, tierisches, geistiges Reich, insofern der Mensch das Geistige ist. Ich steige auf durch die Wirklichkeiten; aber die Natur gibt mir selbst die Bilder dieser Wirklichkeiten. Sie bildet sich ab. Die farbige Welt ist keine Wirklichkeit, die farbige Welt ist schon in der Natur selber Bild: und das Bild des Toten ist das Schwarze, das Bild des Lebenden ist das Grüne, das Bild des Seelischen ist das Pfirsichblüt, das Bild des Geistes ist das Weiß.

Das führt uns hinein in die Farbe in bezug auf das Objektive derselben. Das mußten wir heute voraussetzen, indem wir weitergehen wollen, um in die Natur der Farbe, in das Wesenhafte der Farbe hineinzudringen. Denn es nützt nichts, zu sagen: Die Farbe ist ein subjektiver Eindruck. — Das ist der Farbe höchst gleichgültig. Dem Grün ist es höchst gleichgültig, ob wir da hingehen und es anglotzen; aber es ist ihm nicht gleichgültig, daß sich das Lebende, wenn es sich seine eigene Farbe gibt, wenn es sich nicht durch das Mineralische tingiert und in der Blüte farbig erscheint und so weiter, wenn das Lebende in seiner eigenen Farbe erscheint, es sich nach außen grün abbilden muß. Das ist etwas, was objektiv ist. Ob wir es anglotzen oder nicht, das ist etwas ganz Subjektives. Aber daß das Lebende, wenn es als Lebendes erscheint grün erscheinen muß, grün sich abbilden muß, das ist ein Objektives.

Ja, das ist dasjenige, was ich heute voraussetzen wollte... [Lücke im Text.]

Nun, morgen werden wir wiederum um halb neun Uhr den Fortsetzungsvortrag über die Farbenlehre haben.

The Essence of Color I

The color experience — The four image colors

The colors we want to talk about over these three days are of interest to physicists — we won't be discussing that aspect of colors this time — but they are also, or at least should be, of interest to psychologists and researchers of the soul, and above all they must be of interest to artists and painters. And if we look around at the views that have formed about the world of colors up to the present day, we will have to conclude that, although psychologists are allowed to say this or that about subjective experiences with colors, this cannot have any real significance for the understanding of the objective world of colors, which is something that only physicists can actually understand. And art is certainly not allowed to decide anything about the nature of colors and color in an objective sense. People today are far, far removed from what Goethe meant in his often-quoted statement: “Those to whom nature begins to reveal its obvious secrets feel an irresistible longing for its most worthy interpreter, art.”

A person who is truly immersed in the arts, like Goethe, cannot doubt for a moment that what the artist has to say about the world of color must be closely related to the essence of color. In ordinary, trivial life, we initially treat color according to the surfaces of objects that appear colorful to us, according to the impressions we have of color in nature. We then arrive at a certain understanding of color, which I would describe as fluctuating, through the well-known prismatic experiment, and we gain or seek to gain insights into the world of color in many other ways. In doing so, we always keep in mind that color should first be judged according to subjective impression. You know, for a long time it was customary in physics, one might even say customary, to say: What we perceive as a world of color is actually only present for our senses, while out in the world, objective color represents nothing more than a certain wave motion of the finest substance, which is called ether.

However, anyone who wants to imagine something among the definitions and explanations given in this way cannot make sense of such a concept that what they know as color impression, what they experience as color impression, has anything to do with some kind of moving ether. But when we talk about color, about the quality of color, we always have the subjective impression in mind, and we look for something objective. But then we stray completely from color. For in all the ether vibrations that are conceived—conceived they are in reality—there is of course nothing left of what our colorful world is. And if you want to get into the objective nature of colors, you have to try to stick to the world of colors itself. One must try not to leave the world of color. Then one can hope to penetrate into what is actually the essence of color.

Let us try to delve into something that can be given to us by color from the whole wide, diverse world. And since we want to penetrate the essence of color, we must, since we perceive something in color, raise the whole observation into our sensory life, so to speak. We must try to ask our sensory life about what lives as color in our environment. And it is best to proceed in a certain sense by experimenting ideally, so that we do not only have the given processes, which are generally difficult to analyze and do not appear so striking or radical to us, but can get straight to the essentials.

Suppose I were to try to paint a green color on the surface in front of you, that is, I would cover the surface with a green color. Now, if I did that, the surface would appear to be covered with a green color in some way. I ask you to disregard what cannot happen — one does not usually paint green on black. But I only want to show you the schematic here. [Drawing is made.]

If we simply allow ourselves to be stimulated by the color, we can experience something in the green as such that we do not need to define further. And no one will now be in any doubt that what we can experience in such green, we must of course also experience when we look at the green plant cover of the earth. We will also experience what we experience in pure green in the plant cover of the earth, precisely because this plant cover is green. We must disregard everything else that this vegetation cover offers us; we want to look only at the greenness. And let us now assume that I imagine this greenness in my mind's eye.

If I now paint something into this greenness, I can paint it in with a wide variety of colors. Let us consider three colors.

So here I have one shade of green, here the second shade of green, and here the third shade of green. Now imagine that I paint something red into the first shade of green; in the second case, I paint a kind of peach blossom color into the green — well, I don't have it, but let's assume I do — and in the third case, I paint something blue into it.

You will now have to admit that, purely in terms of sensation, what I have done in these three cases has produced something completely different, and that there is a certain emotional content when I reproduce this red form, or whatever it is, in the green, or reproduce the peach blossom form in the green, or even reproduce the blue form in the green. The task now is to express in some way the feeling content that presents itself to the soul's eye.

If one wants to express something like this, one will have to try to describe it in some way, because one will of course achieve very little with abstract definitions. Now, in order to come up with a description, let's simply try to imagine something in what we have painted before us. Let's assume that in the first case I really wanted to evoke the feeling of a green plant cover, and I draw red people into it. Whether I make their faces red and their skin red, or whether I dress them in red, it doesn't matter. Here [in the first green] I paint red people, here in the second green I paint peach-blossom people—which would roughly correspond to human flesh—and here [in the third green] I paint blue people. So I am not doing this to reproduce anything from nature, but only to be able to visualize a complex of sensations of what is actually there.

Imagine you had this view: red people walking across a green meadow, or peach-blossom people walking across a green meadow, or even blue people walking across the green meadow — in all three cases, a thoroughly different complex of sensations! When you see the first, you will say to yourself: These red people I see there in the green, on the green meadow, they enliven the whole green meadow for me. The meadow is even greener because the red people are walking across it. The green becomes even more saturated, even more alive because the red people are walking there. And I will become angry when I look at these people as they are, as red people. That's actually nonsense, I'll say, that can't be. I would actually have to make these red people like lightning; they would have to move. Because calm red people in a green meadow have an exciting effect in their calmness, because they already move through their red color, they cause something on the meadow that is actually impossible to hold in calmness. So, I have to get into very specific complexes of feeling if I want to carry out such an idea at all.

That [with the second green] works quite well. People who are like these peach blossom people can stand there [calmly]; if they stand there for hours, it doesn't bother me. So that I notice in my feeling: these peach-blossom people actually have no special relationship to the meadow, they do not excite the meadow, they do not make it greener than it is, they are completely neutral to the meadow. They can stand wherever they want, they do not bother me there. They are suitable everywhere. They have no inner relationship to the green meadow.

I move on to the third: I look at the blue people in the green meadow. The [blue], you see, doesn't even last; it doesn't last at all. Because this blue of the people in the green meadow dampens the whole green meadow for me. The meadow is dulled in its greenness. It doesn't remain green at all. Just try to imagine, in your imagination, blue people walking around on a green meadow, or blue beings in general—they could also be blue ghosts wandering around—just try that: it stops being green, it takes on a bluish hue itself, becomes bluish itself, stops being green. And if these blue people stay on the green for a long time, then I can't imagine it at all. Then I have the idea that there must be an abyss somewhere, and the blue people are taking the meadow away from me, carrying it away, throwing it into the abyss. That is so impossible that it cannot remain, because a green meadow cannot remain when blue people are standing there; they take it with them, they carry it away.

You see, that is the experience of color. One must be able to have this experience of color, otherwise one will not be able to do anything with what the world of colors actually is. If you want to get to know what experiences its most beautiful, most significant application in the imagination, then you must also be able to experiment, I would say, in the realm of the imagination. You must be able to ask yourself: What becomes of a green meadow when red people walk on it? — It becomes even greener, it becomes completely real in its greenness. The green literally begins to burn. But the red people cause such life around them in the greenness that I cannot imagine it calmly; they actually have to run around. And if I were to really paint the picture, I could not paint calm people standing there in red, but I would have to paint in such a way that I... [gap in the text]. They move as if in a round dance. A round dance painted with red people would be possible on a green meadow. In contrast, people who are not dressed in red, who would dress entirely in flesh tones, could stand on the green meadow for all eternity. They are completely neutral to the green, absolutely indifferent to the green meadow; it remains as it is. It does not change in the slightest. But the blue people run away from me with the meadow, because the whole meadow loses its greenness because of the blue people.

Of course, one must speak comparatively when talking about color experiences. One cannot talk about color experiences like a philistine, because then one cannot approach the color experience. One must speak comparatively. But isn't it true that even the ordinary philistine speaks comparatively when he says: one billiard ball hits another. — Deer butt, and oxen and buffalo butt in reality, but billiard balls do not butt in reality. Nevertheless, in physics we speak of “bumping” because we need analogies everywhere if we want to start talking at all.

Well, that gives us, so to speak, the opportunity to see something in the world of color as such. There is something inside that we will have to seek out as the essence of color.

Let's take a very characteristic color—we have already considered it here—let's take the color that appeals to us most in our environment during the summer: the color green. We encounter it in plants. And we are already accustomed to seeing this green in plants as a characteristic of plants. When something is so closely associated with the essence of a thing, as greenness is with plants, we do not actually perceive it as anything else. We do not feel that certain animals that are green could really only be green; we always have the underlying thought that they could also be something other than green. But with plants, we have the idea that greenness belongs to them, that greenness is something peculiar to them. Let us try to penetrate the objective essence of color in plants, whereas otherwise only the subjective essence of color is sought.

What is the plant that, in a sense, presents us with green? Well, you know that, from a spiritual scientific point of view, the plant actually exists because it has an etheric body in addition to its physical body. This etheric body is what actually lives in the plant. But this etheric body is not green. The essence that makes the plant green is already located in the physical body of the plant, so that although green is intrinsic to the plant, it cannot constitute the actual primordial essence of the plant. For the actual primordial essence of the plant lies in the etheric body; and if the plant had no etheric body, it would be a mineral. In its mineral nature, the plant actually reveals itself to us through its greenness. The etheric body is colored quite differently. But the etheric body reveals itself to us through the mineral greenness of the plant. When we consider the plant in relation to the etheric body, when we consider its greenness in relation to the etheric body, then we must say: If we put the actual essence of the plant, the etheric, on one side, and on the other side, by separating it in abstracto, the greenness, then it is really as if we were merely making an image of something when we take the greenness out of the plant. In what I have extracted as green from the etheric, I actually only have an image of the plant, and this image is — as is peculiar to the plant — necessarily green. So, I actually get the greenness in the image of the plant. And by attributing the green color to the plant in a very essential way, I must attribute this greenness to the image of the plant, and in the greenness I must seek the special essence of the plant image.

You see, we have come to something very essential. No one will fail to say, when they see an ancestral gallery somewhere in an old castle — you can still see them for the time being — that these are only pictures of the ancestors, not the real ancestors. — That's right, the ancestors are not usually there; they are only pictures of the ancestors. But even when we see the green of the plant, we do not have the essence of the plant, just as we do not have the ancestors in the pictures of the ancestors. In the green that appears before us, we only have the image of the plant. And now consider that greenness is peculiar to the plant, that the plant is, among all beings, the very essence of life. Isn't it true that animals have souls, and humans have minds and souls? Minerals have no life. The plant is the being that is characterized precisely by the fact that it has life. Animals also have a soul. Minerals do not yet have a soul. Humans also have a spirit. We cannot say that the essence of humans, animals, or minerals is life; their essence is something else. In plants, the essence is life; the green color is the image. So I am actually remaining entirely objective when I say:

Green represents the dead image of life.

You see, now I have suddenly found something for a color—let's proceed inductively if we want to express ourselves in a scholarly way—that allows me to place this color objectively in the world. I can say, just as I can say when I receive a photograph that this photograph is of Mr. N., I can also say: When I have green, green represents the dead image of life to me. I am not merely reflecting on the subjective impression, but I come to the conclusion that green is the dead image of life.

Let's take this color here, peach blossom. To be more precise, I would rather speak of the color of human incarnate, which of course is not quite the same in different people, but we come to a color that I actually mean when I speak of peach blossom .... [gap in text]. Peach blossom: that is, human incarnate, human skin color. Let us try to get to the essence of this human skin color. Usually, we only see this human skin color from the outside. We look at a person and then we see this human skin color from the outside. But the question arises as to whether an awareness of this human skin color can also be attained as a recognition from within, similar to what we did with the green of the plant. Well, this can indeed be achieved in the following way.

If a person really tries to imagine that they are imbued with soul within and that this soulfulness is transferred to their physical form, they can imagine that what imbued them with soul pours into their form in some way. They live themselves out by pouring their soul into their form, into their incarnate body. You can perhaps best understand what this means by looking at people whose soul recedes somewhat from their skin, from their outer form, whose soul does not, so to speak, permeate their form. What happens to these people? They turn green! Life is within them, but they turn green. You speak of green people, and you can perceive this peculiar green in the complexion very clearly when the soul recedes. On the other hand, the more a person takes on this particular reddish hue, the more you will notice the experience of this hue in them. Just observe the temperament and humor of green people and those who have a really fresh incarnate, and you will see that the soul experiences itself in the incarnate. What radiates outwardly in the incarnate is nothing other than the person experiencing themselves as a soul. And we can say: what we see in the incarnate as color is the image of the soul, truly the image of the soul. But travel as far as you like in the world, [you will find]: for what appears as human incarnate, we must choose the peach blossom. Otherwise, we cannot really find it in external objects. We can only achieve it through all kinds of artistic tricks in painting; [because] what appears there as human incarnate is already an image of the soul, but it is, without a doubt, not itself soulful. It is the living image of the soul. The soul that experiences itself experiences itself in the flesh. It is not dead, like the green of the plant, for when man withdraws his soul, he turns green: then he reaches the dead. But in the flesh I have the living. So:

Peach blossom represents the living image of the soul.

So we have an image in the first case and an image in the second case.