Colour

Part I

GA 291

7 May 1921, Dornach

2. The Luminous and Pictorial Nature of Colours

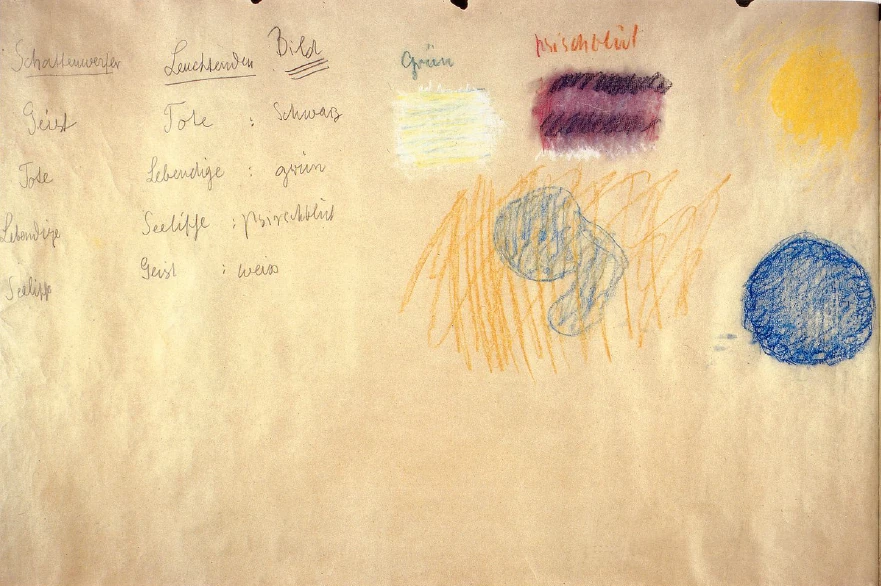

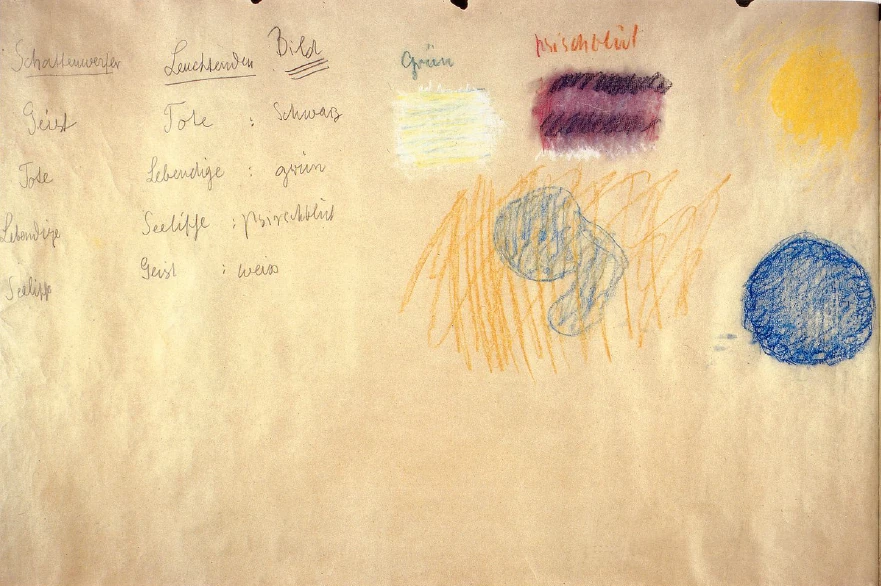

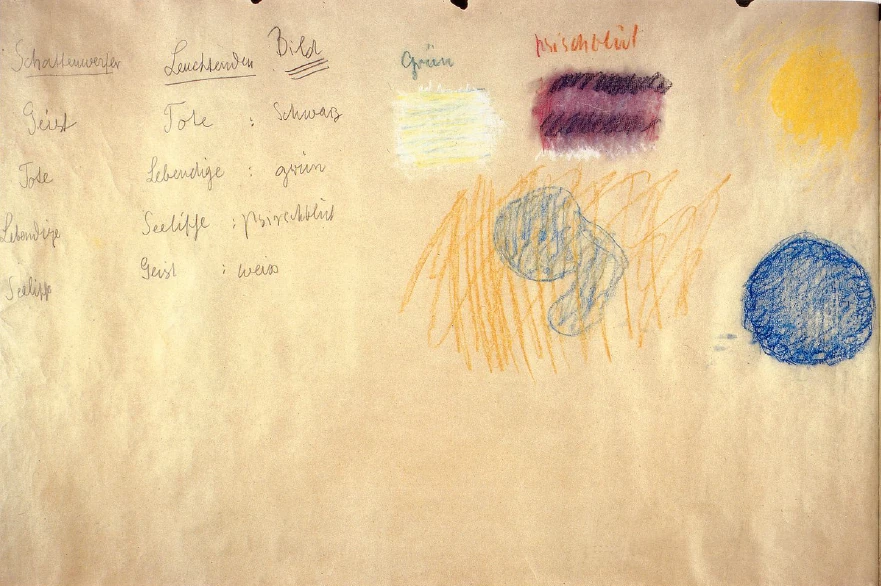

We tried yesterday to understand the nature of colour from a certain point of view and found on the way—white, black, green, peach-blossom colour; and in such a manner that we were able to say: these colours are images or pictures, they are already present in the world with the character of pictures; but we saw also that something essential proceeded from something else giving rise to the pictorial character of the colour. We saw, for example, that the living must proceed from the lifeless, and that in the lifeless the image of the living, the green arises. I shall continue today from our yesterday's experience, and in such a way as to differentiate between, so to speak, the receiver and the give, between that in which the picture is formed, and the originator of it. Then I shall be able to put the following division before you: I differentiate (you will understand the expression if you take the whole of what we did yesterday)—I differentiate the shadow-thrower from the Illuminant. If the shadow-thrower is the spirit, the spirit receives that which is thrown upon it; if the shadow-thrower is the spirit and if the illuminant (it is an apparent contradiction, but not a real one) is the dead, then black is pictured in the spirit as the image of the dead, as we saw yesterday.

If the shadow-thrower is the dead, and the illuminant the living, as in the case of the plant, then, as we saw, you have green. If the shadow-thrower is the living and the illuminant the psychic, then, as we saw, you get the image of peach-colour. If the shadow-thrower is the psychic and the illuminant the spirit, you get white as the image.

So you see, we have got these four colours with the pictorial character. We can therefore say: with a shadow-thrower and an illuminant, we get a picture. So we get here four colours—but you must reckon black and white among the colours—with the picture-character: black, white, green, peach-colour.

When the lifeless appears in the Spirit you get black.

| SHADOW THROWER | ILLUMINANT | PICTURE |

| The Spirit | The dead | black |

| The dead | The living | green |

| The living | The psychic | peach-colour |

| The psychic | The spirit | white |

Now, as you know, there are other so-called colours, and we have to search also for their natures. We shall not search for them through abstract concepts any more than before, but approach the matter according to feeling, and then you will see that we come to a certain understanding of the colours if we put the following before our eyes.

Think of a quiescent white. Then we will let beams of different colours from opposite sides play on to this quiescent white—it can be a quiet white room—from one side yellow and from the other blue. We then get green.

In this way therefore we got green. We have to visualize exactly what happens: we have a quiescent white, into which we throw rays of colour from both sides, one yellow and the other blue and we get the green we have already found from another point of view.

You see, we cannot look for the peach-colour as we looked for the green, if we confine ourselves to the living production of colour. We must seek it in another way, as follows: Imagine I paint here a black, below it a white, another black, below it a white and so on—black and white alternately—now imagine that this black and white was not quiescent—they would vibrate, as it were. In fact, it is the opposite of what we had up here: here we had a quiescent white and let beams of colour into it from both sides in a continuous process, yellow and blue from left and right. Now I take black and white; I cannot of course paint that at the moment, but imagine these undulating through each other; and just as I let in yellow and blue before, allow now this undulation, with its continual interplay of black and white, to be shone through, pierced with red: if I could select the right shade, I should, through this play of black and white into which I let the red shine, get peach-colour.

Notice how we must resort to quite different methods of producing colours. With one we must take a quiescent white—and thus we must destroy one of the picture-colours in the scale we already have here—and let two other colours which we have not yet got play upon it. But here we have to go about it differently; here we have to take two of the colours we have, black and white, we must instill movement into them, take a colour we have not yet got, namely red, and let is shine through the moving white and black. You will also see something which will strike you if you observe life: green you have in nature; peach-colour you have (as I explained yesterday, in my sense) only in a fully healthy man. And, I said, the possibility is not easily present of reproducing this shade of colour. For one could really reproduce it only if one could represent white and black in motion and then let fall on them the beam of red. One would really have to produce a circumstance—it is after all present in the human organism—in which there was always motion. Everything is in movement and from that fact arises this colour of which we are speaking. So that we can get this colour only in a roundabout way, and for this reason the majority of portraits are really only masks, because flesh-colour can be realized only by means of all sorts of approximations. It could be achieved only, you see, if we had a continual wave movement of black and white, with red rays through it.

I have here pointed out to you from the nature of things a certain difference in relation to colour. I have shown you how to use the colours which we get as pictorial colours, how in one case we used white, in a condition of rest, and by throwing upon it two colours which we have not yet got, we obtained another pictorial colour, namely, green.

Again, we take two colours, black and white, in a scale of reciprocated movement, and let them be penetrated or illuminated by a new colour, that we have not yet got, and the result is another colour—peach-colour. We get peach-colour and green, therefore, in quite different ways. In one case we required red, in the other yellow and blue. Now we shall be able to go a step further towards the nature of colour if we consider another thing.

Taking the colours we found yesterday, we may say as follows: By its own nature green always allows us to make it with definite limits. Green can be enclosed or limited: in other words it is not unpleasant to us if we paint a surface green and give is a circumscribed area. But just imagine this is the case of peach-colour. It does not agree with our artistic sense. Peach-colour can be represented really only as a mood, without reference to a defined area, without expecting one. If you have a sense of colour, you can feel that. If, for instance, you think of a green—you can easily think of green card-tables. Because a game is a limited pedantic activity, something very Philistine, one can think of such an arrangement—a room with card-tables covered in green. What I mean is that it would be enough to make you run away, if you were invited to play cards on mauve tables. On the other hand, a lilac coloured room, or a room furnished throughout in mauve, would lend itself very well, shall we say, to mystical conversation, in the best and the very worst sense. It is true, the colours in this respect are not anti-moral, but amoral. Thus we note that as a result of its own nature, colour has a inner character; whereby green allows itself to be defined, lilac and peach or flesh-colour tend to spread into vagueness.

Let us try to get a the colours which we did not have yesterday, from this point of view. Let us take yellow, the whole inner nature of yellow, if we make here a yellow surface. Yes, you see, a defined surface of yellow is something disagreeable; it is ultimately intolerable for someone with artistic feeling. The soul cannot bear a yellow surface which is limited and defined in extent. So we must make the yellow paler towards the edges, and then still paler. In short we must have a full yellow in the centre and from there it must shade off to pale yellow. You cannot picture yellow in any other way, if you want to feel it with your own being. Yellow must radiate, getting paler all the time. That is what I might call the secret of yellow. And if you hem in the yellow, it is in fact as if you laughed at it. You always see the human factor in it, which has bounded the yellow. Yellow does not speak when it is bounded, for it refuses to be bounded, it wants to radiate in some direction or other.

We shall see a case in a moment, where yellow consents to be bounded, but it will just go to show how impossible it is, considering its real inner nature. It wants to radiate. Let us take blue on the other hand. Imagine a surface covered equally with blue. One can imagine it, but it has something super-human. When Fra Angelico paints equal blue surfaces, he summons, as it were, something super-terrestrial into the terrestrial sphere. He allows himself to paint an equal blue when he brings super-terrestrial things into the terrestrial sphere. In the human sphere he would not do it, for blue as such, because of its own nature, does not permit a smooth surface. Blue by its inner nature demands the exact opposite of yellow. It demands that the colour is intensified on the circumference and shades off towards the center. It demands to be strongest at the edges and palest in the middle. Then blue is in its element. By this it is differentiated from yellow. Yellow insists on being strongest in the center, and then paling off. Blue piles itself up at the edges and flows together, to make a piled-up wave, as it were, round a lighter blue. Then it shows itself in its very own nature.

We arrive therefore on all sides at what I might call the feeling or longing of the soul in face of colours. And these are fulfilled; that is, the painter really responds to them, if he paints in accordance with what the colour itself demands. If he consciously thinks—now I've dipped my brush in the green, now I must be a bit of a Philistine and give the green a sharp outline; if he thinks: now I am painting yellow—I must make that radiate, I must imagine myself the spirit of radiation; and if he thinks when painting blue: I draw myself in, into my innermost self and build, as it were, a crust round me, and so I must also paint by giving the blue a kind of crust: then he lives in his colour and paints in his picture what the soul really must want if it yields itself to the nature of colour.

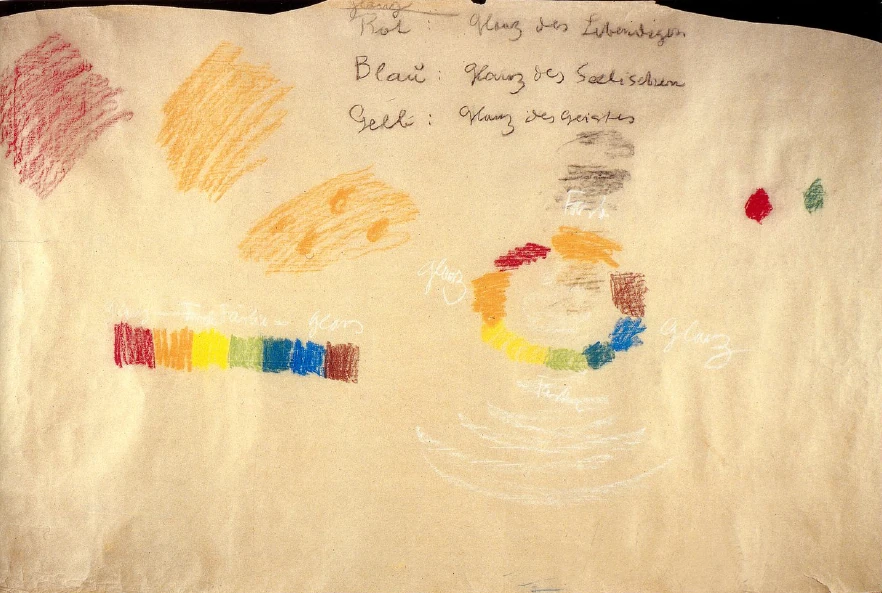

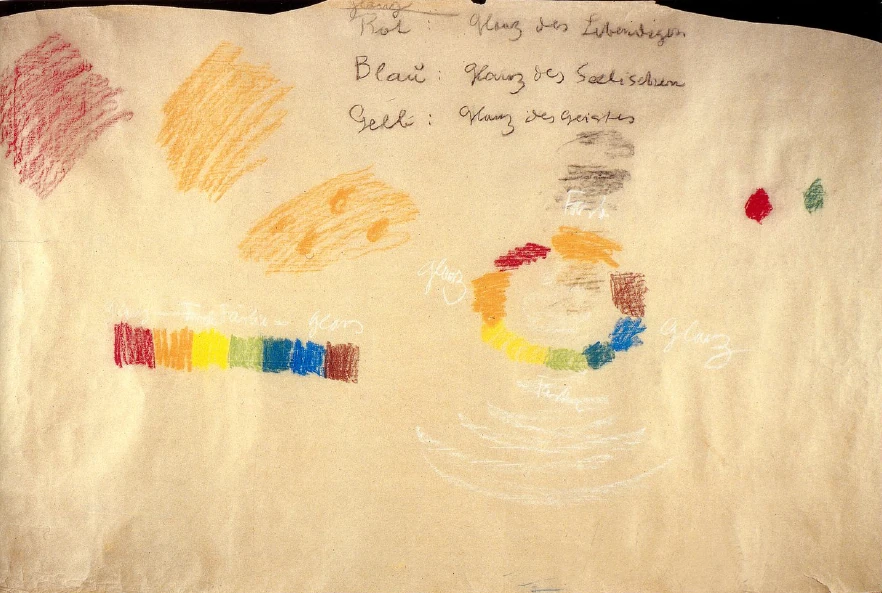

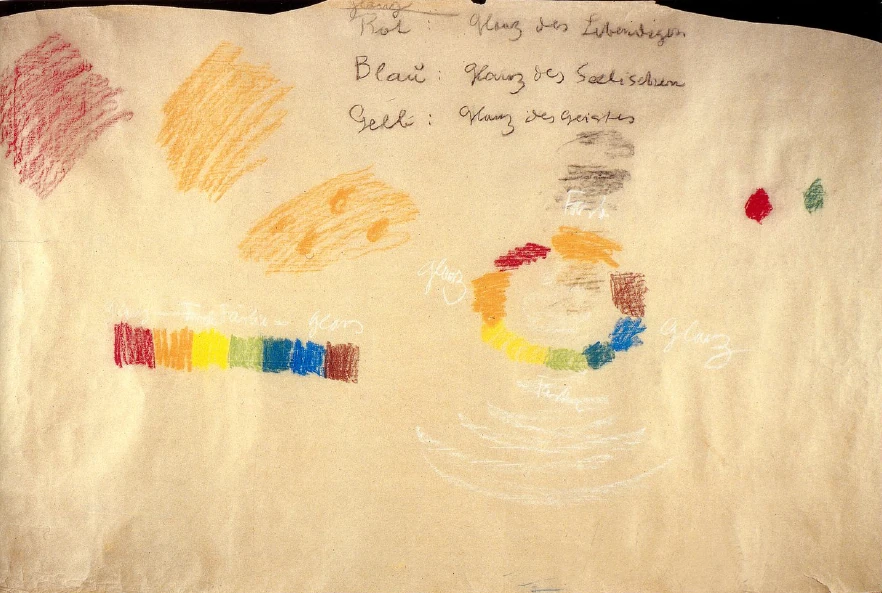

Of course, as soon as we touch upon art, a factor comes in which modifies the whole thing. I'll make circles here for you which I fill in with colour. (Diagram 1)

One can of course have other figures than these; but the yellow must always radiate in some direction and the blue must always contract, as it were, into itself.

The red I might call the balance between them. We can accept the red completely as a surface. We understand it best if we differentiate it from peach-colour, in which it is, you remember, incorporated as an illuminant. Take the two shades side by side, red and peach-colour. What happens when you let the red really influence your soul? You say, this red affects me as a quiet redness. It is not the case with peach-colour. That wants to split up, to spread. It is a nice difference between red and peach-colour. Peach-colour wants to disintegrate, it wants to get ever thinner and thinner till it has disappeared. The red remains, but its effect is one of surface. It does not want to radiate or pile itself up, or to escape; it asserts itself. Lilac, peach-colour, flesh-colour, do not really assert themselves: they want always to change their form, because they want to escape. That is the difference between this colour, peach, which we already have, and red, which belongs to those colours which we have not yet got. But we have not three colours together: blue, red and yellow.

Yesterday we found the four colours: black, white, peach-colour and green; now red, blue and yellow are before us and we have tried to get inside these three colours with our feeling, to see how they interplay with the others. We let the red interplay with a motionless white and we shall easily find the distinction if we now examine what we have brought before the soul. We cannot make such a distinction in the colours we found yesterday as we now have made between yellow, blue and red. We were compelled today to let black and white move in and out of each other when we produced peach-colour. Black and white are “picture-colours” which can do this; let us leave it at that.

Peach-colour we must also leave; it disappears of its own accord, we cannot do anything with it, we are powerless against it. Nor can it help itself, it is its nature to disappear. Green outlines itself, that is it nature. But peach-colour does not demand to be differentiated in itself, but to be uniform, like red; if it were differentiated it would level itself out at once. Just imagine a peach-coloured surface with lumps in it! It would be awful. It would promptly dissolve the lumps, for it always strives for uniformity. If you have an extra green on green, that is a different matter; green has to be applied evenly and has to be outlined. We cannot imagine a radiating green. You can imagine a twinkling star, can't you; but hardly a twinkling tree-frog. It would be a contradiction for a tree-frog to twinkle. Well—that is the case also with peach-colour and green.

If we want to bring black and white together at all we must make them undulate into each other as pictures, even if as moving pictures. But it is different with the three colours we have found today.

We saw that yellow wants, of its own nature, to get paler and paler towards the edges; it wants to radiate; blue wants to heap itself up, to intensify itself, and red wants to be evenly distributed without outline. It wants to hold the middle place between radiating and concentrating; that is red's nature. So you see there is a fundamental difference between colours that are in themselves quiet or mobile, quiet as green, or mobile as mauve, or isolated like black and white. If we want to bring these colours together, it must be as pictures. And red, yellow and blue, in accordance with their inner activity, their inner mobility, are distinguished from the inner mobility of lilac. Lilac tends to dissolve—that is not an inner mobility—it tends to evaporate; red is quiet—it is movement come to rest—but, when we look at it, we cannot rest at one point: we want to have it as an even surface, which, however, is unlimited. With yellow and blue we saw the tendency to vary. Red, yellow and blue differ from black, white, green and peach-colour. You see it from this: Red, yellow and blue have, in contrast to those other colours which have pictorial qualities, another character and if you consider what I have said about them you will find the term I apply to this different character justified. I have called the colours black, white, green and peach-colour pictures—“pictorial colours” (Bildfarben,) I call the colours yellow, red and blue “lusters”—luster colours. (Blanz-farben,) in yellow, red and blue, objects glisten: they show their surfaces outwards, they shine or glisten.

That is the nature and the difference in coloured things. Black, white, green, peach-colour have a pictorial colour, they take their colour from something; in yellow, blue and red there is an inherent luster. Yellow, blue, red are external to something essential. The others are always projected pictures, always something shadowy. We can call them the shadow-colours. The shadow of the spiritual on the psychic is white. The shadow of the lifeless on the spirit is black. The shadow of the living on the lifeless is green. The shadow of the psychic on the living is peach-colour. “Shadow” and “picture or image” are akin.

On the other hand with blue, red and yellow we have to do with something luminous, not with shadow, but with that by which the nature advertises itself outwardly. So that we have in the one case pictures or shadows and in the other, in the colours red, blue and yellow we have what are modifications of illuminants. Therefore I call them lustrous. The things shine, they throw off colour in a way; and therefore these colours have of their own accord the nature of radiation: yellow radiating outwards, blue radiating inwards, and red the balance of the two, radiating evenly. This even radiation shining on and through the combination of white and black in motion produces peach-colour.

Letting yellow flash from one side on to stationary white and blue from the other side, produces green.

You will observe, we come here upon things which upset Physics completely—you can take everything known today in Physics about colours. There one just writes down the scale: Red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. One does not mention the reciprocal interplay. Let us run along the scale. You will see that starting with the luster red, the lustrous property ceases more and more till we come to a colour in picture, in shadow-colour, to green. Then we come again to a lustrous colour of an opposite kind to the former, we come to blue, the concentrated luster-colour. Then we must leave the usual physical colour-scale entirely in order to get to the colour which can really not be represented at all except in a state of movement. White and black, pierced by rays of red give peach-colour. If you take the ordinary scheme of the physicist, all you can say is: All right—red, orange, yellow, green blue, indigo, violet ...

Notice I start from a luster, go on to what is properly a colour, on again to a luster and only then come to a colour.

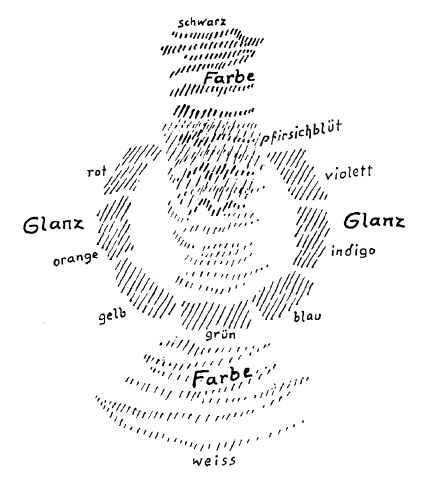

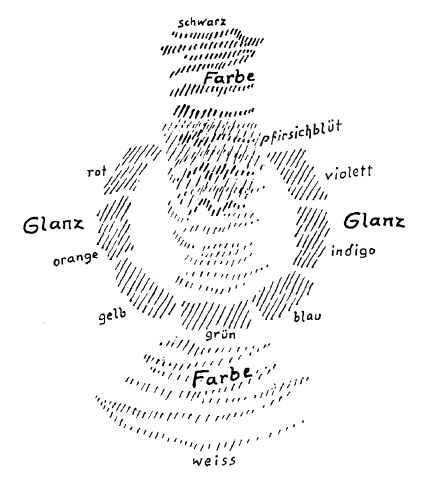

Now, if I did not do that as it is on the physical plane, but were to turn it as it is in the next higher world, if I were to bend the warm side of the spectrum and the cold side so that I drew it like this (Diagram 2) red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet; if I were to bend this stretched-out line of colour into a circle, then I should get my peach-colour up here at the top.

Thus I return again to colour. Colour I and Colour II to and bottom, Luster III and Luster IV left and right. Now there still lurks hidden only that other colour—white and black. You see, if I go up here with the white (from the bottom upwards) it would stick in the green, so the black comes down here to meet it (from the top downwards,) and here at V they begin to overlap; thus, together with the rays from the red, they produce the peach-colour.

I have therefore to imagine a white and a black, overlapping and interplaying (See Diagram 2) and in this way I get a complex colour combination, which however corresponds more closely to the nature of colours than anything you see in the books on Physics.

Now, let us take luster: but luster means that something shines. What shines? If you take the yellow (and you must take it with your feeling and colour-sense, not with the abstract-loving understanding,) you need only say: In receiving the impression of yellow, I am really so moved by it that it lives on within me, as it were. Just think, yellow makes us gay; but being gay means, really, being filled with a greater vitality of soul. We are therefore more attuned to the ego through yellow, in other words we are spiritualized. So, if you take yellow in its original nature, that is, fading outwards, and think of it shining within you, because it is a luster-colour, you will have to agree: Yellow is the luster of the spirit. Blue, concentrating, intensifying itself outwards, is the luster of the psychic. Red, filling space evenly, is the luster of the living. Green is the picture of the living; red, the luster.

You can see this very well if you try to look at a fairly strong red on a white surface; if you look away quickly, you see green as the after-image, and the same surface as a green after-image. The red shines into you and it forms its own picture within you.

But what is the picture of the living in the inner being? You have to destroy it to get an image. The image of the living is the green. No wonder that red luster produces the green as its image when it shines into you.

Thus we get these three colour-natures of quite different kinds. They are the active colour-natures. It is the thing that shines which contains the differentiation; the other colours are quiescent images. We have something here which has its analogy in the Cosmos. We have in the Cosmos the contrast of the Signs of the Zodiac, which are quiescent images, and that which differentiates the Cosmos in the Planets. It is only a comparison, but one which is founded on fact. We may say that we have in black, white, green and peach-colour something whose effect is static; even when it is in movement; something of the fixed stars. And in red, yellow and blue we have something essentially in motion, something planetary. Yellow, blue, red give a nuance to the other colours; yellow and blue tinge white to green, red gives peach colour when it shines into the combined black and white.

Here you see the Colour-Cosmos. You see the world in its inter-action, and you see that we really have to go to colour if we want to study the laws of coloured things. We must not go from colours to something else, we must remain in the colours themselves. And when we have a grasp of colours, we come to see in them what is their mutual relationship, what is the lustrous, the luminous, and what is the shadow-giving, the image-producing element in them.

Just think what this means to Art. The artist knows if he is dealing with yellow, blue and red that he must conjure into his picture something that has a dynamic character, that itself gives character. When he works with peach-colour and green on black and white, he knows that the picture-quality is already there. Such a colour-theory is inherently so completely living that it can be transferred directly form the psychic into the artistic. And if you so understand the nature of the colours that you recognize, as it were, what each colour wants—that yellow wants to be stronger in the middle and to pale off towards the edge, because that is the inherent quality of yellow—then you must do something if you want to fix the yellow, if you want to have a smooth, even yellow surface somewhere. What does one do then? Something must be put into the yellow which deprives it of its own character, of its own will. The yellow has to be made heavy. How can this be done? By putting something into the yellow which gives it weight, so that it becomes gilded. There you have yellow without the yellow, left yellow to a certain extent, but deprived of its nature. You can make an even gold background to a picture, but you have given weight to the yellow, inherent weight; you have taken away its own will; you hold it fast.

Hence the old painters who had a susceptibility to such things found that in yellow they have the luster of the spirit. They looked up to the spiritual, to the light of the spirit in yellow; but they wanted to have the spirit here on earth. They had to give it weight, therefore. If they made a gold background, like Cimabue, they gave the spirit habitation on earth, they evoked the heavenly in their picture. And the figures could stand out of the background of gold, could grow as creations of the spiritual. These things have an inherent conformity to law. You observe, therefore, if we deal with yellow as a colour, of it sown accord it wants to be strong in the centre and shade off outwards. If we want to retain it on an evenly-coloured surface, it is necessary to metallize it. And so we come to the concept of metallized colour, and to the concept of colour retained in matter, of which we shall say more tomorrow.

But you will notice one must first understand colours in their fleeting character before one can understand them in solid substantial form. We shall proceed to this tomorrow. We come in this to what ordinary people—and “extraordinary” people, for that matter—alone call colour. For they know only the colours which are present in solid bodies, and therefore they say—“If one speaks of the spirit, as, for instance, of thought (pretty sentence, isn't it?), then the spirit either is coloured—or not coloured.” Well, then, in this case there is not the least possibility of rising to the volatility of colour!

You will observe that what I have been explaining provides a way to recognize the materialization of the colours in the physical colour-spectrum. It stretches right and left endlessly, that is indefinitely; in the spirit and in the psychic realm, everything is joined up. We must join up the colour-spectrum. And if we train ourselves to see not only peach-colour, but the movement in it; if we train ourselves not only to see flesh-colour in man, but also to live in it; if we feel that our bodies are the dwelling-place of our souls as flesh-colour, then this is the entrance, the gateway into a spiritual world. Colour is that thing which descends as far as the body's surface; it is also that which raises man from the material and leads him into the spiritual.

Das Wesen der Farben II

Bildwesen und Glanzwesen der Farben

Wir versuchten gestern das Wesen der Farben in einem gewissen Sinne zu erfassen und haben auf unserem Wege gefunden: Weiß, Schwarz, Grün und Pfirsichblütfarbe. Und zwar haben wir sie so gefunden, daß wir sagen konnten: Diese Farben sind Bilder, sind schon innerhalb der Welt mit dem Bildcharakter vorhanden. Aber wir haben gesehen, daß es sich darum handelt, daß irgendein Wesenhaftes gewissermaßen aufgefangen werde von einem anderen, damit der Bildcharakter der Farbe entstehe. Wir haben gesehen, daß zum Beispiel das Lebende von dem Toten aufgefangen werden muß und im Toten dann das Bild des Lebenden, das Grün entsteht. Ich werde heute noch einmal ausgehen von dem, was sich uns da gestern als Ergebnis herausgestellt hat, und zwar in der Art, daß ich unterscheiden werde zwischen dem gewissermaßen Empfangenden und dem Gebenden, demjenigen, in dem sich das Bild gestaltet, und dem Veranlasser des Bildes. Dann werde ich etwa die folgende Gliederung vor Sie hinstellen können, werde sagen können: Ich unterscheide — Sie werden den Ausdruck verstehen, wenn Sie das Ganze zusammennehmen, was wir gestern gemacht haben -, ich unterscheide den Schattenwerfer von dem Leuchtenden. Ist der Schattenwerfer der Geist, empfängt der Geist dasjenige, was ihm zugeworfen wird; ist der Schattenwerfer der Geist, und ist das Leuchtende — es ist ein scheinbarer Widerspruch, aber in Wirklichkeit ist es kein Widerspruch —, und ist das Leuchtende das Tote, dann bildet sich im Geiste als Bild des Toten, wie wir gesehen haben, das Schwarz [siehe Schema]. Ist der Schattenwerfer das Tote, und ist das Leuchtende das Lebendige wie bei der Pflanze, dann bildet sich, wie wir gesehen haben, das Grün. Ist der Schattenwerfer das Lebendige, das Leuchtende das Seelische, dann haben wir gesehen, bildet sich als Bild das Pfirsichblüt. Ist der Schattenwerfer das Seelische, das Leuchtende der Geist, dann bildet sich als Bild das Weiß.

Sie sehen also, wir haben diese vier Farben bekommen mit dem Bildcharakter. Wir können also sagen: Wir haben ein Schattenwerfendes, ein Leuchtendes, und bekommen das Bild. Wir bekommen also hier vier Farben - Sie müssen nur Schwarz und Weiß zu den Farben rechnen -, wir bekommen hier vier Farben mit Bildcharakter: Schwarz, Weiß, Grün, Pfirsichblütfarbe.

| Schattenwerfer | Leuchtende | Bild |

|---|---|---|

| Geist | Tote | Schwarz |

| Tote | Lebendige | Grün |

| Lebendige | Seelische | Pfirsichblüt |

| Seelische | Geist | Weiß |

Nun gibt es ja, wie Sie wissen, andere sogenannte Farben, und wir müssen auch für sie das Wesen suchen. Wir werden dieses in der Weise suchen, daß wir uns wiederum nicht durch abstrakte Begriffe, sondern empfindungsgemäß der Sache nähern, und da werden Sie sehen, daß wir zu einer gewissen empfindungsgemäßen Auffassung des anderen Farbigen kommen, wenn wir das Folgende einmal uns vor Augen führen.

Denken Sie sich ein ruhiges Weiß. Wir wollen in dieses Weiß, in dieses ruhige Weiß von den zwei entgegengesetzten Seiten verschiedene Farben hereinstrahlen lassen. Wir wollen von der einen Seite in dieses ruhige Weiß Gelb hereinstrahlen lassen, und wir lassen von der anderen Seite Blau hineinstrahlen. Aber Sie müssen sich vorstellen, daß wir ein ruhiges Weiß haben, und daß wir in dieses ruhige Weiß — es kann ein ruhender weißer Raum sein — von der einen Seite Gelb und von der anderen Seite Blau hereinstrahlen lassen. Wir bekommen dann Grün. [Es wird gezeichnet.]

Wir bekommen also auf diese Weise Grün. Wir müssen den Vorgang wirklich genau vor unsere Seele führen: Wir haben ein ruhiges Weiß, in das wir von beiden Seiten einstrahlen lassen, von der einen Seite Gelb, von der anderen Seite Blau, und bekommen das Grün, das wir von dem anderen Gesichtspunkte aus eben schon gefunden haben.

Sehen Sie, so wie wir jetzt das Grün gesucht haben, so können wir nicht, wenn wir im Lebendigen des Farbenwerdens uns bewegen, das Pfirsichblüt suchen. Wir müssen das Pfirsichblüt auf eine andere Weise suchen. Wollen wir das Pfirsichblüt suchen, dann könnten wir das etwa auf folgende Weise tun. Denken Sie sich, ich male das Folgende hin: Ich male hier ein Schwarz, darunter ein Weiß, wieder ein Schwarz, darunter ein Weiß und würde so fortgehen, Schwarz, Weiß... Aber nun denken Sie sich, dieses Schwarze und Weiße wäre nicht ruhig, sondern es bewegte sich ineinander, es wellte ineinander. Also das ist das Gegenteil von dem, was hier oben war: hier habe ich ein ruhendes Weiß gehabt und lasse von beiden Seiten einstrahlen, so daß die Strahlung eine fortgehende Tätigkeit ist von links und rechts [Gelb und Blau]. Jetzt nehme ich Schwarz und Weiß. Ich kann das natürlich zunächst nicht malen, aber denken Sie sich diese ineinanderwellend. Und so wie ich vorhin von links und rechts habe strahlen lassen Gelb und Blau, so lassen Sie sich jetzt dieses Gewellte, in dem fortwährend Schwarz und Weiß ineinanderspielt, das lassen Sie sich bitte durchglänzen, durchstrahlen von Rot. Ich würde es etwa bekommen, wenn ich es jetzt einfach verschmieren würde. Wenn ich die richtige Nuance hätte wählen können, so würde ich durch dieses Ineinanderwellen von Schwarz und Weiß, in das ich das Rot hineinglänzen lasse, das PAirsichblüt bekommen.

Sie sehen, wie wir die ganz verschiedene Entstehung aufsuchen müssen. Das eine Mal müssen wir ein ruhiges Weiß nehmen - also in der Skala, die wir hier schon haben, müssen wir eine von den Bildfarben zugrunde legen, und zwei andere Farben, die wir noch nicht haben, müssen wir einstrahlen lassen. Hier aber müssen wir anders verfahren. Hier müssen wir zwei von den Farben, die wir hier haben, Schwarz und Weiß, nehmen, wir müssen sie in Bewegung bringen und müssen dann eine Farbe nehmen, die wir noch nicht haben, nämlich das Rot, und müssen es einstrahlen lassen durch das bewegte Weiß und Schwarz. Sie sehen damit auch etwas, was Ihnen, wenn Sie das Leben beobachten, auffallen wird. Das Grün haben Sie in der Natur; das Pfirsichblüt haben Sie eigentlich nur, so wie ich es meine — wie ich gestern auseinandergesetzt habe —, beim ganz gesunden, gesund durchseelten Menschen in seinem Organismus. Und wir bekommen [in der Malerei] nicht leicht, sagte ich, die Möglichkeit, überhaupt diese Farbennuance darzustellen. Denn sehen Sie, man könnte sie eigentlich nur darstellen, wenn man Weiß und Schwarz in Bewegung darstellen könnte und dann sie durchstrahlen ließe von dem roten Scheine. Man müßte also eigentlich einen Vorgang malen. Dieser Vorgang ist ja auch vorhanden im menschlichen Organismus; da ist niemals Ruhe, da ist alles in Bewegung, und dadurch entsteht eben [im Inkarnat] diese Farbe, von der wir hier sprechen. Diese Farbe aber können wir nur annäherungsweise erreichen, Daher sind ja die meisten Porträts eigentlich nur Masken, weil dasjenige, was nun wirklich als das Inkarnat vorhanden ist, im Grunde genommen nur durch allerlei Annäherungsversuche versinnlicht werden kann; aber erreicht werden könnte es ja nur, wenn wir fortwährend ein Auf- und Abwellen von Schwarzem und Weißem hätten, das durch das Rote durchstrahlt wäre, durchscheint wäre.

Ich habe Ihnen hier aus dem Wesen der Sache heraus einen gewissen Unterschied in bezug auf das Farbige angedeutet. Ich habe Ihnen angedeutet, wie man sich bedienen kann der Farben, die wir als Bildfarben haben; wie wir das eine Mal eine — das Weiß — verwenden können als ruhend, und indem wir die zwei Farben - von denen, die wir noch nicht haben - hineinscheinen lassen, eine andere Bildfarbe bekommen: das Grün.

Nun können wir zwei von den Farben nehmen, Schwarz und Weiß, die sich ineinander bewegen, und wir lassen sie durchscheinen von einer Farbe, die wir noch nicht haben, und wir bekommen die andere Farbe, das Pfirsichblüt. In ganz verschiedener Weise also bekommen wir Grün und Pfirsichblüt. Das eine Mal brauchen wir das Rot als Schein, das andere Mal brauchen wir das Gelb und Blau als Schein. Nun werden wir des weiteren auf das Wesen dieses Farbigen kommen können, wenn wir noch ein anderes überlegen.

Wenn wir die Farben nehmen, die wir gestern gefunden haben, so können wir das Folgende sagen: Grün gestattet uns eigentlich immer durch seine eigene Wesenheit, daß wir es mit bestimmten Grenzen machen. Grün läßt sich gewissermaßen begrenzen; es ist uns nicht antipathisch, wenn wir eine grüne Fläche anstreichen und ihr Grenzen geben. Aber denken Sie sich das einmal mit Pfirsichblüt gemacht. Das läßt sich gewissermaßen nicht mit malerischer Empfindung vereinigen: Pfirsichblüt mit Grenzen. Pfirsichblüt läßt sich eigentlich nur als eine Stimmung auftragen, ohne daß man auf Grenzen reflektiert, ohne daß man es eigentlich darauf absieht, Grenzen zu haben. Man kann ja das schon, wenn man Farbenempfindung hat, erleben. Denken Sie sich zum Beispiel irgendein Grünes: man kann sich ganz gut Spieltische mit grünem Überzug denken. Weil das Spiel eine begrenzt pedantische Tätigkeit ist, etwas Urphiliströses ist, läßt sich solch eine Einrichtung denken, ein Zimmer mit Spieltischen, die grün überzogen sind. Aber ich meine, es wäre zum Davonlaufen, wenn einen jemand zu Tarockpartien auf lila eingelegten Tischen einlüde. Dagegen läßt sich sehr wohl zum Beispiel in einem lila Zimmer, das also sein ganzes Innere lila austapeziert hat, in dem läßt sich sehr wohl, sagen wir, mystisch reden, im besten und im schlechtesten Sinne. Die Farben sind in dieser Beziehung zwar nicht antimoralisch, aber amoralisch. Also wir merken, daß da aus der Natur der Farbe selber etwas folgt, daß die Farbe einen innerlichen Charakter hat, wodurch sich also das Grüne begrenzen läßt; das Lila, das Pfirsichblüt, das Inkarnat ins Unbestimmte verschwimmen will.

Versuchen wir einmal, die Farben, die uns gestern nicht vor die Seele getreten sind, von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus zu erfassen. Nehmen wir das Gelbe. Nehmen wir die ganze innere Wesenheit des Gelben, wenn wir das Gelbe als Fläche auftragen. Ja, sehen Sie, das Gelbe als Fläche aufgetragen mit Grenzen, das ist eigentlich etwas Widerliches, das kann man im Grunde genommen nicht ertragen, wenn man Kunstgefühl hat. Die Seele erträgt nicht eine gelbe Fläche, welche begrenzt ist. Da muß man das Gelbe da, wo Grenzen sind, schwächer gelb machen, dann noch schwächer gelb, kurz, man muß ein sattes Gelb in der Mitte haben, und das muß gegen schwaches Gelb ausstrahlen. [Es wird gezeichnet.] Anders kann man sich das Gelbe im Grunde genommen gar nicht vorstellen, wenn man es aus seiner eigenen Wesenheit heraus erleben will. Das Gelbe muß strahlen, das Gelbe muß durchaus in der Mitte gesättigt sein und strahlen, es muß sich verbreiten und im Verbreiten muß es weniger satt, muß es schwächer werden. Das ist, möchte ich sagen, das Geheimnis des Gelben. Und wenn man das Gelbe begrenzt, so ist das eigentlich so, wie wenn man über die Wesenheit des Gelben lachen wollte. Man sieht immer den Menschen drinnen, der das Gelbe begrenzt hat. Es spricht nicht das Gelbe, wenn es begrenzt ist, denn das Gelbe will nicht begrenzt sein, das Gelbe will nach irgendeiner Seite hin strahlen. Wir werden gleich nachher zwar einen Fall sehen, wo das Gelbe gestattet, begrenzt zu sein, aber der Fall wird uns gerade zeigen, wie es unmöglich ist, das Gelbe als solches seiner inneren Wesenheit nach zu begrenzen. Es will strahlen.

Nehmen wir dagegen das Blaue. Denken Sie sich eine blaue Fläche gleichmäßig aufgetragen. Man kann sich so eine blaue Fläche gleichmäßig aufgetragen denken, aber das hat etwas, was uns aus dem Menschlichen hinausführt. Wenn Fra Angelico blaue Flächen gleichmäßig aufträgt, so ruft er gewissermaßen ein Überirdisches in die irdische Sphäre herein, Er gestattet sich, das Blau dann gleichmäßig aufzutragen, wenn er das Überirdische in die irdische Sphäre hereinspielen läßt. Er würde sich nicht gestatten, in der Menschheitssphäre eine gleichmäßig blaue Fläche zu haben; denn das Blau als solches, durch seine eigene Wesenheit, durch seinen eigenen Charakter, gestattet nicht eine glatte blaue Fläche. Da muß schon ein Gott eingreifen, wenn das Blau wirklich gleichmäßig aufgetragen sein soll. Das Blaue fordert durch seine innere Wesenheit das genaue Gegenteil vom Gelben. Es fordert nämlich, daß es vom Rande nach innen einstrahlt. Es fordert, am Rande am gesättigtsten und im Inneren am wenigsten gesättigt zu sein. [Es wird gezeichnet.] Dann ist das Blaue in seinem ureigenen Elemente, wenn wir es am Rande gesättigter und im Inneren weniger gesättigt machen. Dadurch unterscheidet es sich von dem Gelben. Das Gelbe will in der Mitte am gesättigtsten sein und dann auslaufen. Das Blau, das staut sich an seinen Grenzen und rinnt in sich selber, um so einen Stauwall um ein helleres Blau herum zu machen. Dann offenbart es sich in seiner ureigenen Natur, dieses Blau.

Wir kommen da überall, ich möchte sagen, zu Empfindungen, Sehnsuchten, die die Seele hat, wenn sie den Farben entgegentritt. Und wenn diese erfüllt werden, das heißt, wenn der Maler wirklich dem entgegenkommt, wenn er also so malt, daß er aus der Farbe heraus malt, was die Farbe selber fordert, wenn er also sich denkt: Jetzt hast du den Pinsel in das Grüne eingetaucht, jetzt mußt du ein bißchen Philister werden, mit scharfen Härchen das Grün aufmalen; wenn er denkt: Jetzt malst du das Gelbe, das mußt du ausstrahlen lassen, da mußt du dich in den Geist versetzen, in den strahlenden Geist; wenn er, indem er das Blau malt, denkt: Ich ziehe mich in mich selbst zusammen, ich ziehe mich in mein eigenes Inneres und bilde gewissermaßen eine Kruste um mich, und so male ich auch, indem ich dem Blau eine Art von Kruste gebe, dann lebt er in der Farbe drinnen, dann malt er auf das Bild dasjenige, was die Seele sich eigentlich wünschen muß, wenn sie sich dem Wesen der Farbe hingibt.

Natürlich kommt, sobald man ins Künstlerische hineingeht, das in Betracht, was dann die ganze Sache modifiziert. Ich mache Ihnen hier Kreise, die ich ausfülle mit Farbigem. Aber man kann natürlich andere Figuren, andere Ausfließungen haben. Man wird dann zum Beispiel ein Gelbes, das man, sagen wir, schmal anfängt, dann erweitert, in dem Schmalen anders strahlen lassen als in der Erweiterung. Aber es muß das Gelbe immer irgend etwas überstrahlen, es muß das Blaue immer an einer Stelle angebracht sein, wo gewissermaßen die Sache sich in sich selbst zusammenzieht. Das Rote, das ist, ich möchte sagen, der Ausgleich ‘zwischen beiden.

Wir können das Rote durchaus als irgendeine Fläche fassen. Wir fassen es am besten, wenn wir es unterscheiden von dem PArsichblüt, worinnen es ja, wie wir vorhin gesehen haben, in einer gewissen Weise steckt als Schein. Nehmen Sie die beiden Nuancen nebeneinander, das annähernde Pfirsichblüt und das Rote. Wenn Sie das Rote seinem Wesen nach wirklich auf die Seele wirken lassen, wie ist Ihnen da? Es ist Ihnen so, daß Sie sich sagen: Dieses Rote wirkt auf mich als ruhige Röte. Das ist beim Pfirsichblüt nicht der Fall. Das will auseinander, das will sich weiter verbreiten. [Es wird gezeichnet.] Da ist ein feiner Unterschied zwischen dem Rot und dem Pfrsichblüt. Das Pfirsichblüt strebt auseinander, das will eigentlich immer dünner und dünner werden, bis es sich verflüchtigt hat. Das Rote bleibt, aber es wirkt durchaus als Fläche; es will weder strahlen noch sich inkrustieren, es will weder strahlen noch sich stauen, es bleibt; es bleibt in ruhiger Röte; es will sich nicht verflüchtigen, es behauptet sich. Das Lila, das Pfirsichblüt, das Inkarnat, behauptet sich eigentlich nicht, das will immerfort neu gestaltet werden, weil es sich verflüchtigen will. Das ist der Unterschied zwischen dieser Farbe, dem Pfirsichblüt, die wir schon haben, und dem Roten, das zu denjenigen Farben gehört, die wir noch nicht haben. Aber wir haben jetzt drei Farben zusammen: das Blau, das Rot und das Gelb.

Wir haben gestern gefunden die vier Farben Schwarz, Weiß, Pfirsichblüt und Grün; jetzt stehen Rot, Blau und Gelb vor uns, und wir haben versucht, uns in diese drei Farben empfindungsgemäß hineinzufinden, wie sie in die anderen hineinspielen: Wir haben das Rote hineinspielen lassen in ein bewegtes Schwarz-Weiß; wir haben das Gelb und Blau hineinspielen lassen in ein ruhiges Weiß, und wir werden leicht den Unterschied finden, wenn wir jetzt auf das eingehen, was uns da vor die Seele getreten ist. Wir haben nicht die Möglichkeit, bei den Farben, die wir gestern gefunden haben, solche Unterschiede zu machen, wie wir jetzt zwischen Gelb, Blau und Rot gemacht haben. Wir waren heute gezwungen, indem wir das Pfirsichblütige entstehen ließen, Schwarz und Weiß, aber in sich konsolidiert, ineinander sich verwandeln [sich verwellen?] zu lassen. Wir müssen es aber lassen, Schwarz und Weiß, es sind Bilder, die können sich ineinander verwandeln [verwellen?], aber wir müssen es lassen. Das Pfirsichblüt müssen wir auch lassen. Es verflüchtigt sich von selber, aber wir können nichts mit ihm anfangen, wir sind ohnmächtig gegen dieses Verflüchtigen. Und es selber kann auch nichts machen: das ist seine Natur, daß es sich verflüchtigt. Das Grün begrenzt sich, das ist seine Natur. Aber das Pfirsichblüt verlangt nicht, daß es in sich selber differenziert wird, sondern daß es gleichartig bleibt wie das Rot. Es will nicht in sich differenziert werden, denn es würde sogleich die Differenzierung aufheben und sich verflüchtigen. Es würde sogleich — gleichmachen. Wenn Sie sich irgendein Pfirsichblüt denken und da drinnen solche Knollen [es wird gezeichnet], nun, nicht wahr, es wäre scheußlich! Es würde sofort diese Knollen auflösen, denn es strebt nach gleichartiger, nach gleichmäßiger Stimmung, dieses Pfirsichblüt. Wenn man im Grün noch extra ein Grün hat, so ist es eine Sache für sich. Es ist das Grüne einmal dasjenige, was gleichmäßig aufgetragen sein will und sich begrenzen will. Wir können uns ein strahlendes Grün nicht denken. Nicht wahr, Sie können sich einen strahlenden Stern denken, aber nicht gut einen strahlenden Laubfrosch; es wäre ein Widerspruch zu einem Laubfrosch, wenn er strahlen würde. Nun, das ist auch mit dem Pfirsichblüt und Grün der Fall.

Schwarz und Weiß müssen wir, wenn wir sie überhaupt zusammenbringen wollen, ineinanderwellen lassen als Bilder, wenn auch als bewegte Bilder. Das ist anders bei den drei Farben, die wir heute gefunden haben.

Wir haben gesehen: Das Gelbe will ‘durch seine eigene Natur an seinen Rändern schwächer und immer schwächer werden, es will ausstrahlen; das Blaue will sich einstauen, und das Rote will gleichmäßig sein, keine Grenzen haben, aber als gleichmäßig ruhiges Rot wirken. Es will, wenn wir so sagen dürfen, weder strahlen noch sich stauen, es will in sich gleichmäßig wirken, es will die Mitte halten zwischen Strahlen und Stauen, zwischen Verfließen und Stauen. Das ist die Wesenheit des Roten.

Also Sie sehen, es ist ein Grundunterschied zwischen dem, was in sich gewissermaßen entweder ruhig oder bewegt ist, ruhig wie das Grün, oder bewegt wie das Lila, oder abgeschlossen wie Schwarz und Weiß. Wenn wir diese Farben irgendwie zusammenbringen wollen, müssen wir sie als Bilder zusammenbringen. Und bei dem anderen, was wir gefunden haben als Rot, Gelb und Blau — Rot, Gelb und Blau nach innerer Regsamkeit, innerer Beweglichkeit -, die unterscheiden sich von der inneren Beweglichkeit des Lila. Das Lila will sich auflösen — das ist nicht eine innere Beweglichkeit -, es will sich verflüchtigen. Das Rot, das ist zwar ruhig, es ist die zur Ruhe gekommene Bewegung, aber wir können, wenn wir es anschauen, nicht ruhen an einem Punkt: wir wollen es als Fläche haben, als gleichmäßige Fläche, die aber unbegrenzt ist. Beim Gelb und beim Blau haben wir gesehen, wie es sich in sich differenzieren will.

Rot, Gelb und Blau sind etwas anderes als Schwarz, Weiß, Grün und Pfirsichblüt. Das sehen Sie daraus: Rot, Gelb und Blau haben im Gegensatz zu diesen Farben, die Bildcharakter haben, einen anderen Charakter, und wenn Sie das, was ich über sie gesagt habe, nehmen, dann werden Sie das Wort, das ich für diesen anderen Charakter dieser Farben gebrauche, gerechtfertigt finden. Ich habe die Farben Schwarz, Weiß, Grün und Pfirsichblüt Bilder, Bildfarben genannt. Ich nenne die Farben Gelb, Rot und Blau: Glanze, Glanzfarben. Schwarz, Weiß, Grün, Pfirsichblüt entstehen als Bilder. In Gelb, Blau und Rot erglänzen die Dinge; sie zeigen ihre Oberfläche nach außen, sie erglänzen. Das ist das Wesen, und das ist der Unterschied im Farbigen:

Schwarz, Weiß, Grün, Pfirsichblüt haben Bildcharakter, sie bilden etwas ab. In Gelb, Blau und Rot erglänzt etwas.

Gelb, Blau, Rot: das ist die Außenseite des Wesenhaften. Grün, Pfirsichblüt, Schwarz, Weiß sind immer hingeworfene Bilder, sind immer etwas Schattiges.

So daß wir sagen könnten: Schwarz, Grün, Pfirsichblüt und Weiß sind im Grunde genommen im weitesten Sinne die Schattenfarben. Der Schatten des Geistes in das Seelische ist Weiß. Der Schatten des Toten in den Geist ist Schwarz. Der Schatten des Lebendigen in das Tote ist Grün. Der Schatten des Seelischen in das Lebendige ist Pfirsichblüt. Schatten oder Bilder ist etwas Verwandtes.

Dagegen in Blau, Rot, Gelb haben wir es zu tun mit dem Leuchtenden, nicht mit dem Schattigen, mit demjenigen, wodurch das Wesen sich nach außen ankündigt. So daß wir hier in dem einen Fall Bilder oder Schatten haben. In den Farben Rot, Blau und Gelb haben wir dagegen das, was Modifikationen des Leuchtenden sind. Daher nenne ich sie Glanz. Es erglänzen, es erstrahlen die Dinge in gewisser Weise. Daher haben diese Farben ihrer eigenen Wesenheit nach in sich die Natur des Strahlenden: das Gelb das Ausstrahlende, das Blau das Einstrahlende, das in sich Zusammenstrahlende, das Rot die Neutralisation von beiden, das gleichmäßig Strahlende. Dieses gleichmäßig Strahlende, in das bewegte Weiß und, Schwarz hineinscheinend, hineinglänzend, gibt Pfirsichblüt. In das ruhende Weiß auf der einen Seite hineinglänzen lassen das Gelbe, auf der anderen Seite hineinglänzen lassen das Blaue, gibt Grün.

Sehen Sie, hier trifft man auf Dinge auf, die die Physik — Sie können alles, was es heute an Physik über die Farben gibt, nehmen — chaotisch, ganz chaotisch durcheinanderwirft. Da schreibt man einfach die Skala auf: Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett. Man denkt nicht, was da ineinanderspielt: Im Roten ein Glanz. Gehen wir nun die Skala entlang, so hört das Glänzende immer mehr und mehr auf, und wir kommen in eine Farbe hinein, in ein Bild, in eine Schattenfarbe, in das Grün. Wir kommen wiederum zu einem Glanz, der jetzt entgegengesetzter Art ist von dem anderen Glanz, zu dem sich stauenden Glanz, indem wir nach dem Blauen hinübergehen. Und dann müssen wir ganz aus dem Physischen heraus, aus der gewöhnlichen Farbenskala heraus, um zu dem zu kommen, was man eigentlich gar nicht anders darstellen kann als in Bewegung. Weiß und Schwarz durchscheint, durchstrahlt, durchglänzt von dem Roten, das gibt Pfirsichblüt.

Wenn Sie das gewöhnliche Schema der Physiker nehmen, dann müssen Sie sagen: Nun ja, Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett. Sehen Sie, da[gegen] gehe ich aus von einem Glanz, gehe in die eigentliche [Bild-]Farbe hinein, gehe hier wiederum zu einem Glanz über und käme jetzt erst [wieder] zu einer [Bild-]Farbe.

Ja, wenn ich das Band nicht so machen würde, wie es auf dem physischen Plan ist, sondern wenn ich es wenden würde, wie es dann in der nächsthöheren Welt ist; wenn ich die warme Seite des Spektrums und die kalte Seite des Spektrums so wenden würde, daß ich es eigentlich so zeichnen würde [siehe Zeichnung]: Rot, Orange, Gelb, Grün, Blau, Indigo, Violett; wenn ich das, was im Farbenband in einer Linie ausgebreitet ist, hier zusammenbringen würde, dann würde ich hier [oben] mein Pfirsichblüt bekommen. Ich komme also wiederum zur Farbe zurück. Farbe oben, Farbe unten, Glanz rechts, Glanz links; nur liegt da [oben] noch geheimnisvoll zugrunde das andere der Farben, Schwarz und Weiß. Sie sehen, wenn ich mit dem Weißen jetzt hier herauffahren würde [von unten nach oben], würde es im Grün drinnenstecken, da kommt ihm das Schwarze hier [von oben nach unten] entgegen, nun fangen sie hier in der Mitte an zu raufen: so geben sie mit dem roten Schein zusammen das Pfirsichblüt. Ich muß mir also ein Weiß, ein Schwarz denken, hier übereinandergreifend und ineinanderspielend, und auf diese Weise bekomme ich eine kompliziertere Farbenzusammenstellung, die aber dem Wesen der Farben mehr entspricht als dasjenige, was Sie in den Physikbüchern finden.

Nun sagen wir — Glanz; aber Glanz führt uns darauf, daß etwas glänzt. Was glänzt denn? Ja, sehen Sie, wenn wir das Gelb haben, da brauchen Sie ja nur das folgende — aber Sie müssen das mit der Empfindung, nicht mit dem abstrahierenden Verstande als Erwägung anstellen - sich vor die Seele zu stellen, brauchen sich nur zu sagen: Indem ich das Gelb empfange, werde ich von dem Gelben eigentlich so berührt, daß es innerlich in mir weiterlebt. Das Gelb lebt innerlich in mir weiter. Bedenken Sie, das Gelbe macht uns heiter. Heiter sein, heißt aber im Grunde genommen, sich mit einer größeren inneren seelischen Lebendigkeit im Inneren erfüllen. Wir werden also eigentlich mehr nach unserem Ich hin gestimmt durch das Gelbe. Wir werden durchgeistet, mit anderen Worten, Wenn Sie also das Gelbe in seiner Urwesenheit nehmen, wie es nach außen hin verschwimmt, und wenn Sie sich vorstellen, es glänzt nun, weil es ein Glanz ist, nach Ihrem Inneren, und wenn es in Ihrem Inneren als Geist aufglänzt, so werden Sie sagen müssen:

Das Gelb ist der Glanz des Geistes.

Blau, das Sich-innerlich-Zusammennehmen, das Sich-Stauen, das Sich-innerlich-Erhalten, es ist der Glanz des Seelischen.

Das Rot, das gleichmäßige Erfülltsein des Raumes, es ist der Glanz des Lebendigen.

Das Grün ist das Bild des Lebendigen, und das Rot ist der Glanz des Lebendigen. Das zeigt sich Ihnen ja wunderschön, wenn Sie versuchen, ein Rot auf einer weißen Fläche anzusehen, ein ziemlich gesättigtes Rot; schauen Sie dann rasch weg, so sehen Sie das Grün als Nachbild, so sehen Sie dieselbe Fläche als grünes Nachbild. Das Rot glänzt in Sie herein; es bildet sein eigenes Bild im Inneren. Was ist aber das Bild des Lebendigen im Inneren? Sie müssen es ertöten, um ein Bild zu haben. Das Bild des Lebendigen ist das Grün. Es ist kein Wunder, daß das Rote als Glanz, wenn es in Sie hineinglänzt, das Grün als sein Bild gibt.

So daß wir also eben diese drei ganz andersartigen Farbennaturen bekommen. Es sind die aktiven Farbennaturen. Es ist dasjenige, was glänzt, was gewissermaßen in seiner Wesenheit die Differenzierung hat; die anderen Farben sind ruhige Bilder. Wir haben etwas hier, was den Analogon hat im Kosmos. Wir haben im Kosmos den Gegensatz von Tierkreisbildern, die ruhige Bilder sind, und das den Kosmos Differenzierende in den Planeten. Es ist nur ein Vergleich, aber ein Vergleich, der innerlich sachlich begründet ist. Wir können sagen: Wir haben in Schwarz, Weiß, Grün und Pfrsichblüt etwas, was wie das Ruhende wirkt. Selbst wenn es in Bewegung ist, wenn es ineinanderfließt, so muß es noch innerlich ruhig sein, wie beim Schwarz-Weißen im Pfirsichblüt. Und wir haben in den drei Farbennuancen, im Rot, Gelb und Blau, ein innerlich Bewegtes, ein Planetarisches. Ein Fixsternhaftes in Schwarz, Weiß, Pfirsichblüt und Grün; ein Planetarisches in Gelb, Blau und Rot. Gelb, Blau und Rot nuancieren die anderen Farben. Das Weiße wird nuanciert durch Gelb und Blau zum Grün; das Pfirsichblüt wird nuanciert durch das Rote, indem es hineinglänzt in das ineinanderwirkende Weiß und Schwarz.

Sie sehen hier förmlich den Farbenkosmos. Sie sehen die Welt als Farbe in ihrem Ineinanderwirken, und Sie sehen, daß wir wirklich zu den Farben gehen müssen, wenn wir die Gesetzmäßigkeiten des Farbigen studieren wollen. Wir müssen nicht von den Farben weggehen zu etwas anderem hin, sondern wir müssen in den Farben selber bleiben. Und wenn wir eine Auffassung für die Farben haben, dann kommen wir schon dazu, in den Farben selber dasjenige zu sehen, was ihre gegenseitige Beziehung ist, was in ihnen das Glänzende, Leuchtende ist, was in ihnen das Schattige, Bildgebende ist.

Bedenken Sie, was das für die Kunst bedeutet. Wir haben den Künstler, der weiß, wenn er es mit Gelb, Blau und Rot zu tun hat, so zaubert er auf sein Bild etwas, was einen innerlich aus sich heraus aktiven Charakter hat, was sich selber Charakter gibt. Wenn er mit Pfirsichblüt und Grün auf Schwarz und Weiß arbeitet, da weiß er, daß er in der Farbe schon den Bildcharakter gibt. Eine solche Farbenlehre ist durchaus innerlich so lebendig, daß sie von dem Seelischen aus unmittelbar in das Künstlerische übergehen kann. Und wenn Sie so die Wesenheit der Farbe ergreifen, daß Sie der Farbe es selber ankennen, möchte ich sagen, was sie will: wenn Sie erkennen, daß das Gelb eigentlich in der Mitte gesättigt sein will und verfließen will nach dem Rande, weil das die eigene Natur des Gelben ist — ja, dann muß man etwas machen, wenn man das Gelb fixieren will, wenn man irgendwo eine gleichmäßige gelbe Fläche haben will. Was macht man da? Es muß in das Gelb etwas hineinspielen, es muß etwas hinein in das Gelb, was dem Gelb seinen ureigenen Charakter, seinen eigenen Willen wegnimmt. Es muß das Gelb schwer gemacht werden. Wie kann das Gelb schwer gemacht werden? Indem man etwas in das Gelb hineintut, was ihm die Schwere gibt. Es wird goldfarbig. Da haben Sie das Gelbe entgelbt, gewissermaßen gelb gelassen, aber ihm seine Wesenheit getilgt. Machen Sie in ein Bild einen Goldgrund, dann dürfen Sie es gleichmäßig über die Fläche hin machen, aber Sie haben dem Gelb Schwere gegeben, innerliche Schwere. Sie haben ihm seinen eigenen Willen genommen. Sie halten es in sich fest.

Daher empfanden alte Maler, die für solche Dinge eine Empfindung hatten, daß sie in dem Gelben den Glanz des Geistes haben. Also sie schauten hinauf zum Geistigen, dem Glanz des Geistes im Gelben. Aber sie wollten den Geist hier auf der Erde haben. Sie mußten ihm Schwere geben. Machten sie einen Goldgrund, wie Cimabue, dann gaben sie dem Geistigen Wohnung auf der Erde, dann hatten sie im Bilde gewissermafßen das Himmlische vergegenwärtigt. Und die Gestalten durften herauskommen aus dem Goldgrunde, durften sich entwickeln auf dem Goldgrunde als dasjenige, was Geschöpf ist des Geistigen. Diese Dinge haben eben durchaus eine innerliche Gesetzmäßigkeit. Sie sehen also, wenn wir das Gelbe als Farbe behandeln, so will es aus sich selber in der Mitte satt sein und zerfließen. Wollen wir es in gleichmäßiger Fläche festhalten, dann müssen wir es metallisieren. Und damit kommen wir zu dem Begriff der metallisierten Farbe und zu dem Begriff der stofflich festgehaltenen Farbe, von der wir dann morgen weitersprechen wollen.

Aber Sie sehen, die Farben muß man zuerst in ihrem flüchtigen Charakter erfassen, dann kann man erst die Farbe auch am Körperlichen, am äußerlich Dinglichen erfassen. Und zu dem wollen wir dann morgen schreiten...

Sehen Sie, es ist damit zugleich in dem, was ich angedeutet habe, ein Weg gegeben, das Materialisierte der Farben zu erkennen in dem physikalischen Farbenband. Das geht links und rechts im Grunde ins Unendliche, das heißt ins Unbestimmte. Im Geiste und im Seelischen schließt sich alles zusammen. Da müssen wir das Farbenband zusammenfassen. Und erziehen wir uns dazu, nicht nur Pfirsichblüt zu sehen, sondern das Bewegte des Inkarnats zu sehen, erziehen wir uns dazu, uns das Inkarnat nicht nur vom Menschen zeigen zu lassen, sondern in ihm zu leben, empfinden wir die Erfüllung unseres Leibes mit unserer Seele selber als Inkarnat, so ist dieses der Eintritt, das Tor in eine geistige Welt, dann kommen wir in die geistige Welt hinein. Es ist die Farbe dasjenige, was sich hinuntersenkt bis zu der Oberfläche der Körper, es ist die Farbe auch dasjenige, was den Menschen von dem Materiellen erhebt und in das Geistige hineinführt. Wie gesagt, davon wollen wir dann morgen weitersprechen.

The Essence of Color II

The pictorial nature and luminous nature of colors

Yesterday we attempted to grasp the essence of colors in a certain sense and found our way to white, black, green, and peach blossom color. We found them in such a way that we could say: These colors are images, they already exist within the world with an image-like character. But we saw that it is a matter of something essential being captured, as it were, by something else, so that the image-like character of the color can arise. We saw, for example, that the living must be captured by the dead, and then the image of the living, the green, arises in the dead. Today I will start again from what we arrived at yesterday as a result, in such a way that I will distinguish between, as it were, the receiver and the giver, the one in whom the image is formed and the one who causes the image. Then I will be able to present the following structure to you, and say: I distinguish — you will understand the expression when you take together everything we did yesterday — I distinguish between the shadow caster and the light caster. If the shadow caster is the spirit, the spirit receives what is cast upon it; if the shadow caster is the spirit, and the light is — it is an apparent contradiction, but in reality it is no contradiction — and if the light is the dead, then, as we have seen, black forms in the spirit as the image of the dead [see diagram]. If the shadow caster is the dead, and the luminous is the living, as in the plant, then, as we have seen, green is formed. If the shadow caster is the living, the luminous is the soul, then, as we have seen, the image of the peach blossom is formed. If the shadow caster is the soul, the luminous is the spirit, then the image of white is formed.

So you see, we have obtained these four colors with the image character. We can therefore say: we have a shadow caster, a luminous element, and we obtain the image. So here we have four colors—you only need to add black and white to the colors—we have four colors with image character: black, white, green, and peach blossom color.

| Shadow-casting | Luminous | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Ghost | Dead | Black |

| Dead | Living | Green |

| Living | Spiritual | Peach blossom |

| Spiritual | Ghost | White |

Now, as you know, there are other so-called colors, and we must also seek their essence. We will seek this in such a way that we again approach the matter not through abstract concepts, but through feeling, and you will see that we arrive at a certain feeling-based understanding of the other colors when we consider the following.

Imagine a calm white. We want to let different colors shine into this white, into this calm white, from the two opposite sides. Let us shine yellow into this calm white from one side, and let us shine blue into it from the other side. But you must imagine that we have a calm white, and that we shine yellow into this calm white — it can be a resting white space — from one side and blue from the other. We then get green. [Drawing is made.]

So in this way we get green. We must really visualize the process clearly in our minds: we have a calm white into which we let light shine in from both sides, yellow from one side and blue from the other, and we get the green that we have just found from the other point of view.

You see, just as we have now sought green, we cannot seek peach blossom when we move in the living world of color formation. We must seek peach blossom in a different way. If we want to seek peach blossom, we could do so in the following way. Imagine that I paint the following: I paint black here, white underneath, black again, white underneath, and so on, black, white... But now imagine that this black and white is not static, but moves into each other, waving into each other. So that is the opposite of what was above: here I had a resting white and let light shine in from both sides, so that the radiation is a continuous activity from left and right [yellow and blue]. Now I take black and white. Of course, I can't paint that at first, but imagine them waving into each other. And just as I had yellow and blue radiating from the left and right earlier, now let this undulating, in which black and white continuously interact, let it shine through, radiate through red. I would get it if I simply smeared it now. If I could choose the right shade, I would get the PAirsichblüt through this intertwining of black and white, into which I let the red shine.

You see how we have to seek out very different origins. In one case, we have to take a calm white—that is, in the scale we already have here, we have to take one of the colors in the picture as a basis, and we have to let two other colors that we don't yet have shine through. Here, however, we have to proceed differently. Here we have to take two of the colors we have here, black and white, we have to set them in motion and then take a color that we don't yet have, namely red, and let it shine through the moving white and black. You will also see something that will strike you when you observe life. You have green in nature; you only have peach blossom, as I understand it — as I explained yesterday — in the organism of a completely healthy person with a healthy soul. And we do not easily get [in painting], I said, the opportunity to represent this color nuance at all. For you see, one could actually only represent it if one could represent white and black in motion and then let them shine through with the red glow. So one would actually have to paint a process. This process is also present in the human organism; there is never any rest, everything is in motion, and this is what creates [in the incarnate] this color we are talking about here. However, we can only approximate this color. That is why most portraits are actually only masks, because what really exists as the incarnate can basically only be sensualized through all kinds of attempts at approximation; but it could only be achieved if we had a continuous ebb and flow of black and white, which would be radiated through by the red, would shine through.

I have indicated to you here a certain difference in relation to color, based on the nature of the matter. I have indicated to you how one can make use of the colors that we have as picture colors; how we can use one color — white — as a resting color, and by letting the two colors — which we do not yet have — shine through it, we get another picture color: green.

Now we can take two of the colors, black and white, which move into each other, and we let them shine through with a color that we do not yet have, and we get the other color, peach blossom. In completely different ways, we get green and peach blossom. One time we need red as a shine, the other time we need yellow and blue as a shine. Now we will be able to further understand the essence of this color if we consider another one.

If we take the colors we found yesterday, we can say the following: Green actually always allows us, through its own essence, to do this within certain limits. Green can be limited, so to speak; we do not find it unpleasant when we paint a green surface and give it boundaries. But imagine doing the same with peach blossom. In a sense, this cannot be reconciled with painterly sensibility: peach blossom with boundaries. Peach blossom can really only be applied as a mood, without reflecting on boundaries, without actually intending to have boundaries. If you have a sense of color, you can experience this. Think, for example, of any green color: it is quite easy to imagine gaming tables with green covers. Because gaming is a limited, pedantic activity, something primal and philistine, it is possible to imagine such an arrangement, a room with gaming tables covered in green. But I think it would be enough to make you run away if someone invited you to play tarot on tables with purple inlays. On the other hand, in a purple room, for example, which is entirely wallpapered in purple, it is quite possible to Let's say, mystical talk, in the best and worst sense. In this respect, colors are not anti-moral, but amoral. So we notice that something follows from the nature of color itself, that color has an inner character, whereby green can be limited; purple, peach blossom, and incarnate tend to blur into the indefinite.

Let us try to understand the colors that did not strike us yesterday from this point of view. Let us take yellow. Let us take the whole inner essence of yellow when we apply yellow as a surface. Yes, you see, yellow applied as a surface with boundaries is actually something repulsive; basically, if you have an appreciation of art, you cannot bear it. The soul cannot bear a yellow surface that is limited. Where there are boundaries, the yellow must be made weaker, then even weaker; in short, there must be a rich yellow in the middle, and it must radiate toward a weaker yellow. [A drawing is made.] Basically, there is no other way to imagine yellow if one wants to experience it from its own essence. Yellow must radiate, yellow must be saturated in the center and radiate, it must spread, and as it spreads, it must become less saturated, it must become weaker. That, I would say, is the secret of yellow. And if you limit yellow, it is actually as if you wanted to laugh at the essence of yellow. One always sees the person inside who has limited the yellow. Yellow does not speak when it is limited, because yellow does not want to be limited; yellow wants to radiate in some direction. We will see a case shortly where yellow allows itself to be limited, but this case will show us precisely how it is impossible to limit yellow as such in its inner essence. It wants to radiate.

Let us take blue, on the other hand. Imagine a blue surface applied evenly. One can imagine such a blue surface applied evenly, but there is something about it that takes us beyond the human realm. When Fra Angelico applies blue surfaces evenly, he brings something supernatural into the earthly sphere, so to speak. He allows himself to apply the blue evenly when he lets the supernatural play into the earthly sphere. He would not allow himself to have an evenly blue surface in the human sphere, because blue as such, through its own essence, through its own character, does not allow for a smooth blue surface. A god must intervene if the blue is to be applied evenly. The blue, through its inner essence, demands the exact opposite of the yellow. It demands that it radiates from the edge inwards. It demands to be most saturated at the edge and least saturated in the center. [It is drawn.] Then blue is in its own element when we make it more saturated at the edge and less saturated in the center. This distinguishes it from yellow. Yellow wants to be most saturated in the center and then fade out. The blue accumulates at its edges and flows into itself, creating a dam around a lighter blue. Then it reveals itself in its true nature, this blue.

We arrive everywhere, I would say, at sensations, longings that the soul has when it encounters colors. And when these are fulfilled, that is, when the painter really responds to them, when he paints in such a way that he paints out of the color what the color itself demands, when he thinks to himself: Now you have dipped your brush in the green, now you must become a little philistine, paint the green with sharp little hairs; when he thinks: Now you are painting the yellow, you must let it radiate, you must put yourself in the spirit, in the radiant spirit; when, while painting the blue, he thinks: I withdraw into myself, I withdraw into my own inner being and form a kind of crust around myself, and so I also paint, giving the blue a kind of crust, then he lives inside the color, then he paints on the picture what the soul must actually desire when it surrenders to the essence of color.

Of course, as soon as one enters into the artistic realm, what then modifies the whole thing comes into consideration. Here I am making circles that I fill with color. But of course, one can have other figures, other outflows. For example, one might take a yellow that one starts, let's say, narrowly, then expands, allowing it to shine differently in the narrow part than in the expansion. But the yellow must always outshine something, the blue must always be placed in a spot where, in a sense, the thing contracts into itself. The red, I would say, is the balance between the two.

We can certainly understand the red as any kind of surface. We understand it best when we distinguish it from peach blossom, in which, as we saw earlier, it is present in a certain way as an illusion. Take the two shades side by side, the approximate peach blossom and the red. If you really let the red affect your soul in its essence, how do you feel? You will say to yourself: this red has a calming effect on me. This is not the case with peach blossom. It wants to spread out, it wants to spread further. [It is drawn.] There is a subtle difference between red and peach blossom. Peach blossom strives to spread out, it actually wants to become thinner and thinner until it has evaporated. Red remains, but it acts as a surface; it neither wants to shine nor encrust itself, it neither wants to shine nor accumulate, it remains; it remains in a calm redness; it does not want to evaporate, it asserts itself. The purple, the peach blossom, the incarnate, does not really assert itself; it wants to be constantly redesigned because it wants to evaporate. That is the difference between this color, the peach blossom, which we already have, and the red, which belongs to the colors we do not yet have. But we now have three colors together: blue, red, and yellow.

Yesterday we found the four colors black, white, peach blossom, and green; now we have red, blue, and yellow before us, and we have tried to find our way into these three colors according to our feelings, as they interact with the others: We let red play into a moving black and white; we let yellow and blue play into a calm white, and we will easily find the difference when we now respond to what has come before our soul. We do not have the opportunity to make such distinctions with the colors we found yesterday as we have now made between yellow, blue, and red. Today, by allowing the peach blossom to emerge, we were forced to let black and white, but consolidated within themselves, transform [wave?] into each other. But we must leave it alone, black and white, they are images that can transform into each other [become wavy?], but we must leave it alone. We must also leave the peach blossom alone. It evaporates by itself, but we cannot do anything with it, we are powerless against this evaporation. And it itself can do nothing either: it is its nature to evaporate. Green limits itself, that is its nature. But the peach blossom does not demand that it be differentiated within itself, but that it remain the same as the red. It does not want to be differentiated within itself, because it would immediately remove the differentiation and evaporate. It would immediately — equalize. If you imagine any peach blossom and inside it such tubers [it is drawn], well, wouldn't it be awful! It would immediately dissolve these tubers, because it strives for uniformity, for a uniform mood, this peach blossom. If you have an extra green in the green, it is a thing in itself. Green is something that wants to be applied evenly and wants to be limited. We cannot imagine a radiant green. You can imagine a radiant star, but not a radiant tree frog; it would be a contradiction to a tree frog if it were to shine. Well, that is also the case with peach blossoms and green.

If we want to bring black and white together at all, we have to let them wave into each other as images, albeit as moving images. This is different with the three colors we found today.

We have seen that yellow, by its very nature, wants to become weaker and weaker at its edges; it wants to radiate. blue wants to accumulate, and red wants to be uniform, to have no boundaries, but to appear as a uniformly calm red. It wants, if we may say so, neither to radiate nor to accumulate; it wants to appear uniform in itself; it wants to maintain a balance between radiating and accumulating, between flowing and accumulating. That is the essence of red.

So you see, there is a fundamental difference between what is, in a sense, either calm or moving, calm like green, or moving like purple, or closed like black and white. If we want to bring these colors together in some way, we have to bring them together as images. And with the other colors we have found, red, yellow, and blue—red, yellow, and blue, which are characterized by inner liveliness and inner mobility — these differ from the inner mobility of purple. Purple wants to dissolve — this is not inner mobility — it wants to evaporate. Red is calm, it is movement that has come to rest, but when we look at it, we cannot rest at one point: we want it as a surface, as an even surface, but one that is unlimited. With yellow and blue, we have seen how they want to differentiate themselves within themselves.

Red, yellow, and blue are different from black, white, green, and peach blossom. You can see this from the fact that red, yellow, and blue have a different character to these colors, which have an image-like character, and if you take what I have said about them, you will find the word I use for this different character of these colors to be justified. I have called the colors black, white, green, and peach blossom image colors. I call the colors yellow, red, and blue: brilliance, brilliant colors. Black, white, green, and peach blossom arise as images. In yellow, blue, and red, things shine; they show their surface to the outside, they shine. That is the essence, and that is the difference in color:

Black, white, green, and peach blossom have an image character; they depict something. In yellow, blue, and red, something shines.

Yellow, blue, red: that is the outside of the essential. Green, peach blossom, black, and white are always thrown images, always something shadowy.

So we could say that black, green, peach blossom, and white are basically, in the broadest sense, the shadow colors. The shadow of the spirit in the soul is white. The shadow of the dead in the spirit is black. The shadow of the living in the dead is green. The shadow of the soul in the living is peach blossom. Shadows and images are related.

In contrast, in blue, red, and yellow, we are dealing with the luminous, not the shadowy, with that through which the essence announces itself to the outside world. So that in one case we have images or shadows. In the colors red, blue, and yellow, on the other hand, we have what are modifications of the luminous. That is why I call them brilliance. Things shine and radiate in a certain way. Therefore, these colors have within themselves the nature of the radiant: yellow is the radiant, blue is the shining, the converging, red is the neutralization of both, the evenly radiant. This evenly radiant light, shining and glistening into the moving white and black, produces peach blossom. The yellow glistens into the resting white on one side, the blue glistens into it on the other, producing green.

You see, here we encounter things that physics—you can take everything that physics has to say about colors today—throws into chaotic, complete chaos. You simply write down the scale: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. You don't think about what's going on: a shine in the red. If we now go along the scale, the shine stops more and more, and we come into a color, into an image, into a shadow color, into green. We come again to a brilliance that is now the opposite of the other brilliance, the accumulating brilliance, as we move over to blue. And then we have to leave the physical realm entirely, leave the ordinary color scale, in order to arrive at what cannot really be represented other than in motion. White and black shine through, radiate, glisten through the red, which gives us peach blossom.

If you take the usual scheme of physicists, then you have to say: Well, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet. You see, [in contrast] I start from a brilliance, go into the actual [picture] color, then transition back to a brilliance, and only now would I [again] arrive at a [picture] color.

Yes, if I didn't make the band as it is on the physical plane, but if I turned it as it is in the next higher world; if I turned the warm side of the spectrum and the cold side of the spectrum so that I would actually draw it like this [see drawing]: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet; if I were to bring together here what is spread out in a line in the color band, then I would get my peach blossom here [above]. So I come back to color again. Color above, color below, shine on the right, shine on the left; only there [above] still lies mysteriously underlying the other colors, black and white. You see, if I were to move the white up here now [from bottom to top], it would be stuck inside the green, where the black here [from top to bottom] meets it, and now they start to fight here in the middle: together with the red glow, they produce the peach blossom. So I have to imagine a white and a black overlapping and interacting here, and in this way I get a more complicated color combination, but one that corresponds more to the essence of colors than what you find in physics books.