Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

21 August 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion One

My Dear Friends, in these afternoon sessions I shall speak informally about your educational tasks—about the distribution of work in the school, arrangement of lessons, and so on. For the first two or three days we will have to deal mainly with the question of our relationship to the children. When we meet the children we very soon see that they have different dispositions, and despite the necessity of teaching them in classes, even large classes, we must consider their various dispositions. First, aside from everything else, we will try to become conscious of what I would say is ideal necessity. We need not be too anxious about classes being too full, because a good teacher will find the right way to handle this situation. The important thing for us to remember is the diversity of children and indeed of all human beings.

Such diversity can be traced to four fundamental types, and the most important task of the educator and teacher is to know and recognize these four types we call the temperaments. Even in ancient times the four basic types—the sanguine, melancholic, phlegmatic, and choleric temperaments—were differentiated. We will always find that the characteristic constitution of each child belongs to one of these classes of temperament. We must first acquire the capacity to distinguish the different types; with the help of a deeper anthroposophical understanding we must, for example, be able to distinguish clearly between the sanguine and phlegmatic types.

In spiritual science we divide the human being into I-being, astral body, etheric body, and physical body. In an ideal human being the harmony predestined by the cosmic plan would naturally predominate among these four human principles. But in reality this is not so with any individual. Thus it can be seen that the human being, when given over to the physical plane, is not yet really complete; education and teaching, however, should serve to make the human being complete. One of the four elements rules in each child, and education and teaching must harmonize these four principles.

If the I dominates—that is, if the I is already very strongly developed in a child, then we discover the melancholic temperament. It is very easy to err in this, because people sometimes view melancholic children as though they were especially favored. In reality the melancholic temperament in a child is due to the dominance of the I in the very earliest years. If the astral body rules, we have a choleric temperament. If the etheric body dominates, we have the sanguine temperament. If the physical body dominates, we have the phlegmatic temperament.

In later life these things are connected somewhat differently, so you will find a slight variation in a lecture I once gave on the temperaments.1“The Four Temperaments” in Anthroposophy in Everyday Life, Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, NY, 1995. In that lecture I spoke of the temperaments in relation to the four members of the adult. With children, however, we certainly come to a proper assessment when we view the connection between temperament and the four members of the human being as I just described. This knowledge about the child should be kept in the back of our minds as we try to discover which temperament predominates through studying the whole external bearing and general habits of the child.

If a child is interested in many different things, but only for a short time, quickly losing interest again, we must describe such a child as sanguine. We should make it our business to familiarize ourselves with these things so that, even when we have to deal with a great many children, we can pick out those whose interest in external impressions is quickly aroused and as quickly gone again. Such children have a sanguine temperament.

Then you should know exactly which children lean toward inner reflection and are inclined to brood over things; these are the melancholic children. It is not easy to give them impressions of the outer world. They brood quietly within themselves, but this does not mean that they are unoccupied in their inner being. On the contrary, we have the impression that they are active inwardly.

When we have the opposite impression—that children are not active inwardly and yet show no interest in the outer world, then we are dealing with the phlegmatic children.

And children who express their will strongly in a kind of blustering way are cholerics.

There are of course many other qualities through which these four types of temperament express themselves. The essential thing for us during the first few months of our teaching, however, is to observe the children, watching for these four characteristics so that we learn to recognize the four different types. In this way we can divide a class into four groups, and you should gradually rearrange the seating of the children with this goal in mind. When we have classes of boys and girls, we will have eight groups, four groups of boys and four of girls—a choleric, a sanguine, a phlegmatic, and a melancholic group.

This has a very definite purpose. Imagine that we are giving a lesson; during our teaching we will sometimes talk to the children and at other times show them things. As teachers we must be conscious that when we show something to be looked at, it is different from judging it. When we pass judgment on something we turn to one group, but when we show the children something, we turn to another. If we have something to show that should work particularly on the senses, we turn with particular attention toward the sanguine group. If we want the children to reflect on what has been shown, we turn to the melancholic children. Further details on this matter will be given later. But it is necessary to acquire the art of turning to different groups according to whether we show things or speak about them. In this way what is lacking in one group can be made good by another. Show the melancholic children something that they can express an opinion about, and show the sanguine something they can look at; these two groups will complement each other in this way. One type learns from the other; they are interested in each other, and one supplies what the other lacks.

You will have to be patient with yourselves, because this kind of treatment of children must become habit. Eventually your feeling must tell you which group you have to turn toward, so that you do it involuntarily, as it were. If you did it with fixed purpose you would lose your spontaneity. Thus we must come to think of this way of treating the different tendencies in the temperaments as a kind of habit in our teaching.

Now you should not hurry the preparation of your lessons, but be sure to truly strengthen yourselves for the work. I do not mean that you should spend the limited time at your disposal in a lot of detailed preparation, but nevertheless you can only make these things your own if you ponder over them in your souls. It will thus be our task to concern ourselves in a truly practical way with the teacher’s attitude to the temperamental tendencies of children. So now we will divide the work among you as follows. I will ask one group to concern themselves with the sanguine temperament, a second group with the phlegmatic, a third with the melancholic, and the fourth with the choleric. And then, in our free discussions tomorrow, I would like you to consider the following questions: first, how do you think the child’s own temperament is expressed? Second, how should we deal with each temperament?

With regard to the second question I have something more to say. You can see from the lecture I gave some years ago that, when we want to help a temperament, the worst method is to foster the opposite qualities in a child. Let’s suppose we have a sanguine child; when we try to train such a child by driving out these qualities, we provide a bad treatment. We must work to understand the temperament, to go out to meet it. In the case of the sanguine child, for example, we bring as many things as possible to the attention of the child, who becomes thoroughly occupied, because in this way we can work with the child’s propensities. The result will be that the child’s connection with the sanguine tendency will gradually weaken and the temperaments will harmonize with each other. Similarly, in the case of the choleric child we should not try to prevent ranting and raging, but endeavor to meet the child’s needs properly through some external means. Of course it is often not so easy to allow a child to have a fling in a fit of temper!

You will find a distinct difference between phlegmatic and choleric children. A phlegmatic child is apathetic and is also not very active inwardly. As teachers you must try to arouse a great deal of sympathy within yourselves for a child of this type, and take an interest in every sign of life in such a child; there will always be opportunities for this. If you can only find your way through to the apathy, the phlegmatic child can be very interesting. You should not however express this interest, but try to appear indifferent, thus dividing your own being in two, as it were, so that inwardly you have real sympathy, while outwardly you act so that the child finds a reflection in you. Then you will be able to work on the child in an educational way.

With the choleric child, on the other hand, you must try to be indifferent inwardly, to look on cooly when the child is in a bad temper. For example, if the child flings a paint jar on the floor, be as phlegmatic and calm as possible outwardly during such a fit of temper—imperturbable! On the other hand, you should talk about these things with the child as much as you can, but not immediately afterward. At the time you must be as quiet as possible outwardly and say with the greatest possible calm, “Look, you threw the paint jar.” The next day when the child is calm again, you should talk about the matter with the child sympathetically. Speak about what has been done and offer your sympathy and understanding. In this way you will compel the child to repeat the whole scene in memory. You should then also calmly judge what happened, how the paint jar was thrown on the floor and broke in pieces. By these means very much can be done for children who have a temper. You will not get them to master their temper in any other way.

This will guide you in dealing with the two questions we will consider tomorrow. We will arrange it so that each of you can present what you have to say. Make short notes on what you have thought of and we will talk about what you have prepared. Time must always be allowed for the teaching faculty to discuss these and similar matters. In discussions of this kind, which have a more democratic character, a substitute must be found for a dictatorial leadership like that of a headmaster, so that in reality every individual teacher can always share in the affairs and interests of the others. So tomorrow we will begin with a discussion. As a starting point I would like to give you a kind of diagram to work from.

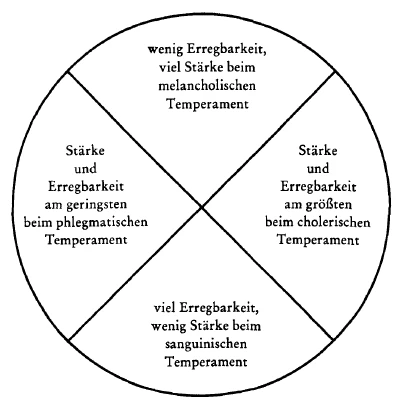

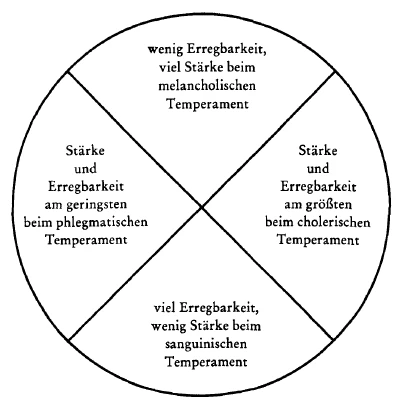

A circle divided into four quadrants:

Top: Attention not easily aroused, but a very strong quality present in the melancholic temperament.

Left: Least amount of strength, attention least easily aroused in the phlegmatic temperament.

Right: Greatest amount of strength, and attention most easily aroused in the choleric temperament.

Bottom: Attention easily aroused, but little strength in the sanguine temperament

Whenever people express themselves in any way, you can tell from their dispositions whether they perceive things strongly or weakly; and further, whether they perceive and feel more strongly what is outside themselves or within their own inner situation. We must also notice whether such people are changeable or not. People either persevere at something and change very little, or show less perseverance and change greatly. This is how the various temperaments differ.

When you have observed such things you will understand certain indications about the temperaments in this diagram. Sanguine and phlegmatic temperaments are frequently found together, and you will see that they are next to each other in the diagram. You will never find a phlegmatic temperament passing easily into the choleric. They are as different as the North and South Poles. The melancholic and sanguine temperaments are also polar opposites. The temperaments that are next to each other merge into one another and mingle; so it will be good to arrange your groups as follows: if you put the phlegmatics together it is good to have the cholerics on the opposite side, and to let the two others, the melancholies and sanguines, sit between them.

All these things bring us back to what I spoke of this morning.22. See The Foundations of Human Experience (previously Study of Man), Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, NY, 1996 and Practical Advice to Teachers, Rudolf Steiner Press, London, 1988 (at the end of the first lectures in each). In addition to these lectures and discussions with the teachers, Rudolf Steiner was giving other lectures simultaneously in order to prepare for the opening of the school the following month. See The Spirit of the Waldorf School: Lectures Surrounding the Founding of the First Waldorf School, Stuttgart–1919, Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, NY, 1995 (these lectures began August 24, 1919). The inner life, the life of soul, is the most significant aspect in the child. Teaching and education depend on what passes from the soul of the teacher to the soul of the child.

We cannot overestimate what takes place in the hidden links that pass from one soul to another. There is, for example, a remarkable interplay between souls when you remain calm and indifferent around a choleric child, or when you have inner sympathy toward a phlegmatic child. In this way your education of the child through your own inner soul mood will have a truly supersensible quality. Education occurs because of what you are, or rather, let’s say, what you make of yourself when you are with the children. You must never lose sight of this.

But children also influence each other. And that is the remarkable thing about this division into four groups of similar temperaments; when you put those that are alike together, it does not have the effect of intensifying their temperamental tendencies but of reducing them. For example, when sanguine children are put together in one group, they do not intensify each other’s sanguinity but tone it down. And when in your lessons you turn to the choleric children, the sanguine profit from what you say, and vice versa. As a teacher you must allow your own soul mood to influence the children, while the children of like temperaments are toning down each other’s soul moods. Talking and chattering together signifies an inner desire to subdue each other, even the chattering that goes on during the breaks. The cholerics will chatter less when sitting together than they would when sitting with children of other temperaments. We must avoid viewing and assessing these things externally.

Right from the very beginning I would like to point out the importance of arranging your teaching in the most concentrated way possible. Only in this way can you consider all the things I have spoken of, especially the temperaments. Therefore we shall not have what is ordinarily called the “schedule.” In this sense our method will be directly opposite to the ideal of modern materialistic education. In Bâle, for example, we hear of the forty-minute period. One forty-minute lesson is immediately followed by another, and this simply means that whatever occurred in the first forty minutes is immediately wiped out again, and fearful confusion is created in the minds of the children.

We must consider very carefully what subject is suitable for a particular age, and then we take this subject—perhaps reading—for awhile without interruption. That is, a child will learn reading every morning for six or eight weeks; after that writing will take its place and then arithmetic, so that for a certain period of time the child will concentrate on one subject. Thus, if I wanted to outline a scheme, our education would consist in this: whenever possible, as far as external arrangements will allow, we should begin the morning with reading and continue this for some weeks, then pass on to writing, and finally to arithmetic.

In such “main lessons” we should also include stories. In the first school year these will be mainly fairy tales. In the second year we try to introduce animal life in story form. From the fable we pass on to speaking of how the animals behave toward each other in real life. But in any case, our lessons will be arranged so that the attention of the children will be concentrated for several weeks on the same thing. Then at the end of the school year we allow time to recapitulate so that what was learned at the beginning will be revived. The only thing that will be kept apart and carried continuously is the artistic work. Either in the afternoons or, if there is enough time, in the mornings we should have art lessons, treating them as a special training of the will.

It would be ideal in school education if concentrated teaching, which require the child to exert the head forces, could be limited to an hour and a half a day. Then we could have another half hour for telling fairy tales—and besides that, it would always be possible to add about another hour and a half for artistic work. This would amount to no more than three and a half hours teaching in the day for children up to the age of twelve. Out of these three and a half hours we could then, on any given day, allow the short time necessary for the religion lesson, and in this way we could teach the children in relays. Thus, if we have a large number of children in one class we could arrange for one group of children from 7 A.M. to 10 A.M., and another group from 10:15 A.M. until 1:15 P.M., and in this way we could manage with the available classroom space.

Our ideal would be, therefore, not to occupy any child for longer than three and a half hours. Then the children would always be fresh, and our only other problem would be to think of what we could do with them in the school gardens when there are no lessons. They can play outside during the summer, but during the winter, when they have to be inside, it is difficult to keep them occupied all the time in the gymnasium. One eurythmy lesson and one gymnastics lesson should be arranged each week. But it is good to keep the children at school even when there are no lessons, so they can play and amuse themselves. I do not think it makes much difference if lessons are begun first thing in the morning or later, so that we could very well divide certain classes into two groups.

Now you must realize that there are all kinds of tasks before you. Over time we will have to discuss the whole organization of our work, but first let’s take this question of story-telling lessons. It would be good if you could consider what you really want to foster in the children by means of these lessons. Our study of the general educational principles will give you what you need for the actual class teaching, but for the story-telling lessons you will have to find the material yourselves to be given to the children during all of their school life, from seven to fourteen years of age, in a free narrative style.33. Seven to fourteen years of age was the original range in the Waldorf school.

To this end, in the initial school years you should have a number of fairy tales available. These must be followed by stories from the animal world in fables; then Bible stories taken as general history, apart from the actual religion lessons; then scenes from ancient, medieval, and modern history. You must also be prepared to tell about the different races and their various characteristics, which are connected with the natural phenomena of their own countries. After that you must move on to how the various races are mutually related to each other—Indians, Chinese, or Americans, and what their peculiarities are: in short, you must give the children information about the different peoples of the Earth. This is particularly necessary for our present age.

These are the special tasks I wanted to give you today. You will then see how discussions can help us. All I wanted to do today was to lay down the general lines for our discussions. During the session Rudolf Steiner had written up the following summary on the blackboard:

1. A fund of fairy tales

2. Stories from the animal realm in fables

3. Bible stories as part of general history (Old Testament)

4. Scenes from ancient history

5. Scenes from medieval history

6. Scenes from modern history

7. Stories of the various races and tribes

8. Knowledge of the races

Questions and Answers

A question concerning the pictures used for sounds and letters—for example, the f in fish, mentioned in the first lecture of Practical Advice to Teachers, which was given in the morning.

RUDOLF STEINER: One must find such things, these pictures for example, for oneself. Don’t rely on what other people have already done. Put your own free, but controlled, imagination to work, and have faith in what you find for yourselves; you can do the same thing for letters that express motion, the letter s for example. Work it out for yourselves.

A question about the treatment of melancholic children.

RUDOLF STEINER: The teacher should view the melancholic child in this way: melancholic tendency arises when the soulspirit of the human being cannot fully control the metabolic system. The nerve-sense human is the least spiritual part of a human being—it is the most physical. The least physical part is the metabolic human. The spiritual human is most firmly rooted in the metabolic organism, but nevertheless, it has realized itself least of all within it. The metabolic organism must be worked on more than any other. Thus, when the metabolic presents too many hindrances, the inner striving toward spirit is revealed in a brooding temperament.

When we deal with a melancholic children, we should try to arouse an interest in what they see around them; we should act, as much as possible, as though we were sanguine, and characterize the world accordingly. With sanguine children, on the other hand, we must be serious, with all inner earnestness, giving them clear strong pictures of the external world, which will leave an impression and remain in their minds.

Spirit has entered most into human beings in the nerve-sense system;44. That is, as free spirit, not absorbed in physical processes. On this important distinction see The Foundations of Human Experience. and spirit has entered least into the metabolic; spirit has the strongest tendency to penetrate into and to be absorbed by the nerve-sense system.

A question about school books.

RUDOLF STEINER: You will have to look at those commonly used. But the less we need to use books the better. We only need printed books when the children have to take public examinations. We have to be clear about how we want to reach our goal in education. Ideally we should have no examinations at all. The final exams are a compromise with the authorities. Prior to puberty, dread of examinations can become the driving impulse of the whole physiological and psychological constitution of the child. The best thing would be to get rid of all examinations. The children would then become much more quick-witted. The temperament gradually wears down its own corners; as the tenth year approaches the difference in temperaments will gradually be overcome. Boys and girls need not be separated; we only do this for the benefit of public opinion. Liaisons will be formed, which need not worry us, although we will be criticized for it. As long as the teacher has authority the teaching will not suffer.

Specialty teachers will be needed for the art subjects, which work on the will, and also for languages, which are taught apart from the Main Lesson. The subjects that the class teacher brings belong together as a whole, and the class teachers can base their work very largely on this unity. In all teaching they will work especially on the intellect and on the feelings.5The German word is Gemüt, which has no exact English equivalent. It expresses “the feeling mind” in the medieval sense—the mind coming from the heart, permeated with feeling, as expressed in an old poem: God be in my head, And in my understanding; God be in mine eyes, And in my looking; God be in my mouth, And in my speaking; God be in my heart, And in my thinking God be at mine end, And at my departing. Anon. From a Sarum Primer of 1558. The arts, gymnastics, eurythmy, drawing, and painting, all work on the will. The teacher goes along in the school with the class. The teacher of the highest class (the eighth grade) then begins again with the lowest (the first grade).

Erste Seminarbesprechung

Meine lieben Freunde, nachmittags will ich in freier Weise besprechen, was bei Ihnen Unterrichtsaufgabe werden soll, Einteilung des Schulwesens, Ordnung des Unterrichts und dergleichen. In den ersten Tagen werden wir uns wohl hauptsächlich zu beschäftigen haben mit dem Kapitel, wie wir den Kindern gegenübertreten.

Wenn wir Kindern gegenübertreten, sehen wir bald, daß die Kinder verschieden geartet sind, und auf die verschiedene Artung der Kinder muß trotz des Massenunterrichtes, auch bei großen Klassen, Rücksicht genommen werden. Wir wollen zuerst, unabhängig von allem anderen, uns dasjenige zum Bewußtsein bringen, was gewissermaßen ideale Notwendigkeit ist. Wir brauchen uns nicht allzusehr daran zu halten, daß Klassen überfüllt sein könnten, denn ein richtiger Lehrer wird, wenn es notwendig sein sollte, vor überfüllten Klassen zu lehren, auch mit überfüllten Klassen zurechtkommen können. Berücksichtigt muß werden die Vielartigkeit der Menschenwesen, der Kinder.

Nun läßt sich diese Vielartigkeit zurückführen auf vier Grundtypen, und es ist die wichtigste Aufgabe des Erziehers und Lehrers, diese vier Grundtypen, die man die Temperamente nennt, wirklich zu kennen. Seit alters unterscheidet man die vier Grundtypen des sanguinischen, des melancholischen, des phlegmatischen und des cholerischen Temperamentes. Wir werden immer finden, daß die charakterologische Beschaffenheit eines jeden Kindes in einer dieser Temperamentsklassen unterzubringen ist. Wir müssen uns zuerst die Fähigkeit aneignen, die verschiedenen Typen zu unterscheiden, von einem tieferen anthroposophischen Standpunkt aus zum Beispiel sanguinische von phlegmatischen wirklich zu unterscheiden.

Wir gliedern im geisteswissenschaftlichen Sinne die Menschenwesenheit in Ich, Astralleib, Ätherleib und physischen Leib. Nun würde natürlich beim Idealmenschen die von der kosmischen Ordnung vorgezeichnete Harmonie walten zwischen diesen vier Gliedern der Menschenwesenheit. Dies ist aber in Wirklichkeit bei keinem Menschenwesen der Fall. Und schon daraus kann man ersehen, daß die Menschenwesenheit nicht eigentlich fertig abgeschlossen ist so, wie sie dem physischen Plan übergeben wird, sondern daß Erziehung und Unterricht dazu dienen sollen, einen vollständigen Menschen aus dem Menschen zu machen. Eines der vier Elemente waltet vor bei einem jeden, und es muß Ergebnis von Erziehung und Unterricht sein, die Harmonisierung zwischen den vier Gliedern herzustellen.

Waltet das Ich besonders vor, das heißt, ist das Ich schon beim Kinde sehr stark entwickelt, dann tritt uns das Kind entgegen mit einem melancholischen Temperament. Man verkennt diese Tatsache sehr leicht, weil man melancholische Kinder manchmal als bevorzugte Wesen ansieht. Eigentlich beruht die melancholische Anlage beim Kinde auf einem Vorherrschen des Ich in den allerersten Jahren.

Waltet der Astralleib vor, dann tritt uns das cholerische Temperament entgegen.

Waltet der Ätherleib vor, dann tritt uns das sanguinische Temperament entgegen.

Waltet der physische Leib vor, dann tritt uns das phlegmatische Temperament entgegen.

Diese Dinge gliedern sich beim späteren Menschen etwas anders. Daher werden Sie bei einem Vortrag, den ich gehalten habe in bezug auf die Temperamente, eine kleine Veränderung finden. In diesem Vortrage sind die Temperamente in Beziehung zu den vier Gliedern des erwachsenen Menschen besprochen worden. Aber beim Kinde werden wir durchaus zu einem richtigen Urteil kommen, wenn wir die Gliederung in dieser Weise betrachten.

Nun müssen wir gewissermaßen solch ein Wissen dem Kinde gegenüber im Hintergrunde halten und versuchen, durch das ganze äußere Auftreten des Kindes, durch den Habitus des Kindes auf die Temperamentsgrundlage zu kommen.

Wenn ein Kind sich für alles mögliche nur kurz interessiert, sein Interesse rasch wieder zurückzieht, dann werden wir es als sanguinisch bezeichnen müssen. Diese Orientierung sollten wir uns durchaus angelegen sein lassen, selbst wenn wir viele Kinder zu erziehen haben, zu konstatieren, welche Kinder sich rasch für äußere Eindrücke interessieren und das Interesse rasch vorübergehen lassen. Die haben ein sanguinisches Temperament.

Dann sollten wir genau wissen, welche Kinder zum inneren Grübeln, zum Brüten neigen; das sind die melancholischen Kinder. Sie sind nicht leicht zu haben für Eindrücke der Außenwelt. Sie brüten still in sich hinein, aber wir haben niemals den Eindruck, daß sie eigentlich innerlich unbeschäftigt sind. Wir haben den Eindruck, daß sie innerlich beschäftigt sind.

Haben wir den anderen Eindruck, daß Kinder innerlich unbeschäftigt sind, daß sie in sich versunken sind und doch auch keine Teilnahme nach außen zeigen, dann haben wir es mit den phlegmatischen Kindern zu tun.

Kinder, die stark ihren Willen durch eine Art von Toben zum Ausdruck bringen, das sind die cholerischen Kinder.

Es wird natürlich noch viele Eigenschaften geben, durch welche sich diese vier Temperamentstypen bei den Kindern ankündigen. Notwendig haben wir aber, daß wir uns in den ersten Monaten unseres Unterrichtes damit beschäftigen, daß wir die Kinder in dieser Zeit auf diese vier Merkmale hin prüfen, daß wir diese Typen bei den Kindern wissen. Wir werden eine Klasse dadurch in vier Abteilungen, in vier Gruppen gliedern können. Es ist wünschenswert, daß wir allmählich ein Umsetzen der Kinder vornehmen. Wenn wir Klassen haben mit beiden Geschlechtern, werden wir acht Gruppen haben. Wir werden die Knaben für sich und die Mädchen für sich in vier Gruppen teilen, in eine cholerische, eine sanguinische, eine phlegmatische und eine melancholische Gruppe.

Das hat einen ganz bestimmten Zweck. Wir unterrichten; und während wir unterrichten, werden wir verschiedene Dinge behandeln, werden Verschiedenes zu sagen, Verschiedenes zu zeigen haben, und wir werden uns als Lehrer zum Bewußtsein zu bringen haben, daß es, wenn wir etwas zeigen, was angeschaut werden soll, etwas anderes ist, als wenn wir ein Urteil darüber abgeben. Wir wenden uns, wenn wir ein Urteil abgeben, zu einer anderen Gruppe, als wenn wir etwas zeigen. Wir wenden uns, wenn wir etwas aufzuzeigen haben, was besonders auf die Sinne wirken soll, mit besonderer Aufmerksamkeit an die sanguinische Gruppe. Wenn wir irgendeine Reflexion über das, was angeschaut wurde, anstellen, dann wenden wir uns an die melancholischen Kinder. Nähere Details werden noch gegeben werden. Aber es ist notwendig, daß wir uns die Geschicklichkeit aneignen, unsere Aufzeichnungen und Ansprachen immer an andere Gruppen zu richten. Dadurch kommt das zustande, daß das, was der einen Gruppe fehlt, durch die andere Gruppe ersetzt wird. Den melancholischen Kindern etwas zeigen, worüber sie urteilen können; den sanguinischen etwas, was sie anschauen können. Sie ergänzen sich dadurch, sie lernen voneinander, richten ihr Interesse aufeinander, diese beiden Gruppen.

Sie müssen mit sich selbst Geduld haben, denn diese Behandlung der Kinderwelt muß einen gewohnheitsmäßigen Charakter annehmen. Man muß das im Gefühl haben, an welche Gruppe man sich zu wenden hat, muß es gewissermaßen von selbst tun. Würde man sich das vornehmen, dann würde man die Unbefangenheit verlieren. Also als eine Art Unterrichtsgewohnheit müßten wir diese Behandlung der verschiedenen Temperamentsanlagen berücksichtigen.

Nun sollen Sie sich nicht in der Vorbereitung überhasten, sondern kräftigen für die Arbeit. Daher meine ich nicht, daß Sie die wenige Tageszeit, die Ihnen noch bleibt, zu großen äußeren Ausarbeitungen verwenden sollen. Dennoch kann man aber die Dinge nur zu seinem inneren Eigentum machen, wenn man sie seelisch verarbeitet. Daher ist es unsere Aufgabe, daß wir mit diesem Verhältnis des Lehrers zu den Temperamentsanlagen der Kinder wirklich sachgemäß verfahren. Wir wollen die Lehrer so einteilen, daß ich bitten werde, daß sich eine Gruppe mit dem sanguinischen Temperament beschäftigt, eine zweite Gruppe mit dem phlegmatischen, eine dritte mit dem melancholischen und eine vierte mit dem cholerischen Temperament.

Ich bitte, daß Sie nachdenken über die zwei Fragen: Wie äußert sich im Kinde das Temperament, das ich eben ausgesprochen habe, je für eine der Gruppen? Da würden Sie morgen in der freien Aussprache auseinandersetzen: Erstens, wie Sie glauben, daß sich das betreffende Temperament in dem Kinde äußert. Zweitens, wie hat man das Temperament zu behandeln.

Über dieses «zu behandeln» will ich noch einiges sagen. Sie können schon aus dem Vortrag, den ich vor Jahren gehalten habe, ersehen, daß es die schlechteste Methode ist, wenn man einem Temperament dadurch beikommen will, daß man gewissermaßen die entgegengesetzten Eigenschaften beim Kinde pflegt. Nehmen wir an, wir haben ein sanguinisches Kind. Wenn wir das dadurch dressieren wollen, daß wir ihm diese seine Eigenschaften austreiben wollen, werden wir es schlecht behandeln. Worum es sich handelt, ist, daß wir gerade auf das Temperament eingehen, ihm entgegenkommen, daß wir möglichst viel beim sanguinischen Kind in die Sphäre seiner Aufmerksamkeit bringen, daß wir es sensitiv beschäftigt sein lassen und dadurch gewissermaßen dem Hang, den es hat, entgegenkommen. So wird sich ergeben, daß dann diese Anlage, in die es eingespannt ist, sich allmählich ablähmt und sich mit den anderen Temperamenten harmonisiert.

Ferner, beim cholerisch tobenden Kinde sollen wir nicht versuchen, es nicht zum Toben kommen zu lassen, sondern versuchen, seine tobenden Eigenschaften in einer solchen Weise zu behandeln, daß wir von außen dem Kinde in der richtigen Weise entgegenkommen. Nun ist esschwer, ein Kind sich immer austoben zu lassen.

Es ist ein deutlicher Unterschied vorhanden zwischen einem phlegmatischen und einem cholerischen Kinde. Ein phlegmatisches Kind ist teilnahmslos, und es ist innerlich nicht viel beschäftigt. Nun versuchen Sie als Lehrer, recht viel Teilnahme für ein solches Kind in Ihrem Inneren aufzubringen, zu erwecken, sich zu interessieren für jede Lebensregung des Kindes. Es gibt immer Gelegenheit dazu. Das phlegmatische Kind kann, wenn man den Zugang findet zu seiner Teilnahmslosigkeit, sehr interessant werden. Aber äußern Sie dieses innere Interesse nicht, suchen Sie teilnahmslos zu scheinen. Versuchen Sie selbst, Ihr Wesen zu spalten. Haben Sie innerlich viel Teilnahme, äußerlich geben Sie sich so, daß es aus Ihnen das Spiegelbild seines eigenen Wesens zu sehen bekommt. Dann werden Sie erzieherisch einwirken können.

Beim cholerischen Kinde dagegen versuchen Sie innerlich teilnahmslos zu werden, mit kaltem Blut zuzuschauen, wenn es tobt. Versuchen Sie, wenn es zum Beispiel das Tintenfaß zur Erde schmeißt, diesem Toben gegenüber äußerlich so phlegmatisch, so gelassen wie möglich zu sein, durch gar nichts ergriffen zu sein! Und versuchen Sie, im Gegenteil dazu, äußerlich möglichst viel von diesen Dingen mit dem Kinde in Teilnahme zu besprechen, aber nicht unmittelbar nachher! Zeigen Sie sich möglichst ruhig äußerlich und sagen Sie mit der möglichsten Ruhe: Du hast nun das Tintenfaß zerschmissen. Am anderen Tag, wenn das Kind selbst ruhig ist, besprechen Sie teilnahmsvoll die Sache mit ihm. Sprechen Sie darüber, was es getan hat, zeigen Sie die größte Teilnahme. Zwingen Sie so das Kind, hinterher die ganze Szene in seinem Gedächtnis zu wiederholen, durchzunehmen. Verurteilen Sie auch ruhig die Vorgänge, wie es das Tintenfaß auf den Boden geworfen, zerschlagen hat. Man kann auf diese Weise mit tobenden Kindern außerordentlich viel erreichen. Auf andere Weise bringt man sie nicht dazu, das Toben zu bekämpfen.

Das kann Sie auf den Weg leiten, nun selbst zu versuchen, die beiden Fragen, die wir uns stellen werden, bis morgen zu behandeln. Wir werden das so behandeln, daß jeder von Ihnen das vorbringen kann, was er eben vorzubringen hat. Machen Sie sich kurze Notizen über das, was Sie sich ausgedacht haben, und diese Notizen werden dann besprochen.

Es muß immer zu Besprechungen solcher und ähnlicher Art in der Lehrerschaft Zeit bleiben. In solchen Besprechungen, die einen mehr republikanischen Charakter tragen, muß Ersatz gefunden werden für eine diktatorische Leitung, wie sie in einem Rektorat gegeben ist, so daß eigentlich jeder einzelne Lehrer an den Angelegenheiten und Interessen der anderen immerwährend teilnimmt. Damit wollen wir morgen gleich beginnen in einer Art Disputation. Als Unterlage möchte ich Ihnen eine Art Schema geben, nach dem Sie arbeiten können.

Sie können unterscheiden, wenn der Mensch sich äußert, nach seinem ganzen Seelenhabitus, ob er etwas stark oder schwach ins Auge faßt; ob er etwas stark empfindet, das etwas Äußerliches ist, oder stark empfindet seine inneren Zustände.

Dann haben wir zu unterscheiden das Wechseln. Entweder man bleibt stark dabei und wechselt wenig, oder man bleibt weniger stark dabei und wechselt sehr viel. Dadurch unterscheiden sich die Temperamente.

Wenn Sie dieses ins Auge fassen, dann werden Sie gleichzeitig in dem Schema eine gewisse Andeutung haben. Nebeneinander sind häufig sanguinisches und phlegmatisches Temperament, und Sie haben es so im Schema. Niemals geht phlegmatisches Temperament leicht ins Cholerische über. Sie sind verschieden wie Nord- und Südpol. Ebenso stehen sich gegenüber melancholisches und sanguinisches Temperament. Sie verhalten sich polarisch entgegengesetzt. Die nebeneinander liegenden Temperamente gehen ineinander über, die verschwimmen. Dagegen wird es gut sein, die Einteilung nach Gruppen so zu befolgen: Wenn Sie eine phlegmatische Gruppe zusammensetzen, ist es gut, wenn diese zum Gegenpol die cholerische hat und dazwischen die beiden anderen sitzen, die melancholische und die sanguinische.

All diese Dinge gehen zurück auf das heute morgen Gesagte. Es hat das Innere, das Seelische eben die allergrößte Bedeutung beim Zusammensein mit dem Kinde. Das Kind wird unterrichtet und erzogen von Seele zu Seele. Ungeheuer viel spielt in den unterirdischen Drähten, die von Seele zu Seele gehen. Und so spielt außerordentlich viel dem cholerischen Kinde gegenüber, wenn Sie teilnahmslos bleiben, dem phlegmatischen gegenüber, wenn Sie inneren Anteil haben. Da werden Sie durch die eigene innere Seelenstimmung übersinnlich erziehend auf das Kind wirken. Das Erziehen geschieht durch das, was Sie sind, das heißt in diesem Fall, wozu Sie sich machen innerhalb der Kinderschar. Das dürfen Sie eigentlich nie aus dem Auge verlieren.

Ebenso wirken aber auch die Kinder aufeinander. Und das ist das Eigentümliche: wenn man Kinder in vier Gruppen von gleichen Temperamentsanlagen einteilt und die gleichartigen nebeneinandersetzt, so wirken diese Anlagen nicht verstärkend aufeinander, sondern aufhebend. Eine Gruppe von sanguinischen Kindern zum Beispiel verstärken nicht ihre Anlagen, sondern sie schleifen sich gegeneinander ab. Wenn man sich dann im Unterricht an die cholerischen Kinder richtet, so nehmen die Sanguiniker davon auf und umgekehrt. Sie müssen als Lehrer die Stimmung Ihrer Seele auf das Kind wirken lassen, während gleichgeartete Temperaments-Seelenstimmungen bei den Kindern sich abschleifen. Das Schwätzen miteinander bedeutet den inneren Hang, sich innerlich abzuschleifen, auch das Schwätzen in den Zwischenpausen. Die Choleriker werden weniger miteinander schwatzen, als wenn sie neben anderen sitzen. Wir dürfen die Dinge nicht äußerlich betrachten und beurteilen.

Nun möchte ich gleich von Anfang an Sie darauf aufmerksam machen, daß wir einen großen Wert darauf legen werden, den Unterricht möglichst konzentriert zu gestalten. Wenn man das nicht tut, kann man auf alle diese Dinge nicht Rücksicht nehmen, von denen ich eben gesprochen habe, namentlich auf die Temperamente nicht. Daher werden wir das, was man im äußeren den Stundenplan nennt, nicht haben. In dieser Beziehung werden wir also geradezu entgegengesetzt der Einrichtung arbeiten, die das Ideal der modernen materialistischen Erziehung ist. In Basel zum Beispiel spricht man vom Vierzigminutenbetrieb. Man läßt gleich wieder etwas anderes folgen. Das heißt nichts anderes, als alles, was in den vierzig Minuten voranging, sofort wieder auszulöschen und furchtbare Verwirrung in den Seelen anzurichten.

Wir werden uns genau überlegen, welcher Lehrstoff einer gewissen Altersstufe des Kindes entspricht, und dann werden wir diesen Lehrstoff, das Lesen zum Beispiel, durch eine gewisse Zeit hindurch verfolgen. Das heißt, das Kind wird seinen Vormittagsunterricht im Lesen während sechs bis acht Wochen haben, dann wird Schreiben an seine Stelle treten, dann Rechnen, so daß das Kind sich die gesamte Zeit hindurch jeweilig konzentriert auf einen Unterrichtsstoff. So daß etwa, wenn ich es schematisch andeuten wollte, unser Unterricht darin bestehen würde, daß wir möglichst am Morgen beginnen - das heißt aber nur möglichst, denn es werden alle möglichen Modifikationen eintreten — mit Lesen, so daß wir einige Wochen lesen, dann schreiben, dann rechnen.

An diesen eigentlichen Unterricht reihen wir dasjenige an, was etwa in der Form des Erzählens zu machen ist. Wir werden im ersten Schuljahr hauptsächlich Märchen erzählen. Im zweiten Schuljahr werden wir uns bemühen, das Leben der Tiere in erzählender Form vorzubringen. Wir werden von der Fabel übergehen zu der Wahrheit, wie die Tiere sich zueinander verhalten. Aber es wird der Unterricht so gestaltet, daß die Aufmerksamkeit des Kindes durch Wochen hindurch auf dasselbe konzentriert ist. Dann werden wir am Ende des Schuljahrs Repetitionen folgen lassen, wodurch aufgefrischt wird, was im Anfang durchgenommen wurde. Absondern und fortdauernd pflegen werden wir nur alles Künstlerische. Entweder nachmittags oder, wenn die nötige Zeit vorhanden, vormittags, sollen wir das Künstlerische als besondere Willensbildung pflegen.

Nun würde es dem Ideal des Unterrichts entsprechen, daß das Kind eigentlich für den konzentrierten Unterricht, wozu Anstrengung des Kopfes notwendig ist, überhaupt nicht mehr als täglich eineinhalb Stunden braucht. Dann können wir noch eine halbe Stunde Märchen erzählen. Außerdem bleibt dann immer noch die Möglichkeit, in etwa eineinhalb Stunden das Künstlerische anzugliedern. Und wir würden dann für die Kinder bis etwa zum zwölften Jahre keine längere Zeit bekommen, als nur dreieinhalb Stunden am Tage. Von diesen dreiieinhalb Stunden nehmen wir dann am einzelnen Tage das wenige, was an Religionsunterricht notwendig ist, so daß wir schon auch die Möglichkeit haben würden, die Kinder so zu unterrichten, daß wir abwechseln könnten.

Wenn wir also viele Kinder für eine Klasse haben, so können wir das so einrichten, daß wir von sieben bis zehn die eine Gruppe haben und von zehn ein Viertel bis ein ein Viertel die andere Gruppe der Kinder, so daß wir auf diese Weise mit dem Klassenraum auskommen könnten.

Das würde das Ideal darstellen, daß wir kein Kind länger als dreieinhalb Stunden beschäftigen. Wir werden dabei immer frische Kinder haben und werden uns nur der Aufgabe unterziehen müssen, auszudenken, was wir mit den Kindern anfangen in den großen Gärten während der Zeit, wo kein Unterricht ist. Sie dürfen auf den freien Plätzen spielen im Sommer; aber im Winter, im Turnsaal, wird es schwer sein, sie beschäftigen zu können. Eine Stunde in der Woche für Turnen und eine Stunde für Eurythmie soll eingerichtet werden. Es wird gut sein, daß die Kinder auch da sein können, wenn kein Unterricht ist, daß sie spielen können und dergleichen. Ich glaube, daß es keinen großen Unterschied macht, ob mit dem Unterricht begonnen wird gleich morgens oder später, so daß wir gut in zwei Gruppen einteilen können.

Nun werden Sie die Aufgabe haben, sich mit allerlei zu beschäftigen. Wir werden nach und nach zu der Eingliederung der Arbeit kommen, indem wir uns in unserer Disputation damit beschäftigen. Aber ich glaube, es wird gut sein, wenn Sie sich überlegen, worin dasjenige bestehen muß, was Sie gewissermaßen in der Erzählungsstunde mit den Kindern zu pflegen haben. Die eigentlichen Unterrichtsstunden werden sich dann aus unseren allgemeinen pädagogischen Gesichtspunkten ergeben. Aber Sie werden für die Erzählungsstunden einen Stoff aufnehmen müssen, der durch die ganze Schulzeit vom siebenten bis vierzehnten Jahr an die Kinder im freien, erzählenden Tone wird herangebracht werden müssen.

Da wird es notwendig sein, daß in den ersten Schuljahren eben ein gewisser Märchenschatz zur Verfügung steht. Dann würden Sie sich für die folgende Zeit damit beschäftigen müssen, Geschichten aus der Tierwelt in Verbindung mit der Fabel vorzubringen. Dann biblische Geschichte, in die allgemeine Geschichte aufgenommen, außerhalb des anderen Religionsunterrichtes. Dann Szenen aus der alten Geschichte, Szenen aus der mittleren Geschichte und aus der neueren Geschichte. Dann müssen Sie sich in die Lage versetzen, Erzählungen über die Volksstämme zu bringen, wie die Volksstämme geartet sind, was mehr mit der Naturgrundlage zusammenhängt. Dann die gegenseitigen Beziehungen der Volksstämme, Inder, Chinesen, Amerikaner, was ihre Eigentümlichkeiten und so weiter sind, das heißt Kenntnis der Völker. Das ist eine ganz besondere Notwendigkeit aus der gegenwärtigen Zeitepoche heraus.

Ich wollte, daß wir uns heute diese besonderen Aufgaben gestellt haben. Sie werden dann sehen, wie wir diese Seminarstunden verwenden werden. Heute soll alles eben fadengeschlagen sein.

Während des Sprechens hatte Rudolf Steiner folgende Übersicht an die Wandtafel geschrieben:

1. ein gewisser Märchenschatz

2. Geschichten aus der Tierwelt in Verbindung mit der Fabel

3. Biblische Geschichte als Teil der allgemeinen Geschichte (Altes Testament)

4. Szenen aus der alten Geschichte

5. Szenen aus der mittleren Geschichte

6. Szenen aus der neueren Geschichte

7. Erzählungen über die Volksstämme

8. Erkenntnis der Völker.

Fragenbeantwortung

Es wird gefragt nach den Bildern für die Laute und Buchstaben wie dem Fisch für das F, wovon am Vormittag im ersten Vortrag des methodisch-didaktischen Kurses gesprochen worden war.

Rudolf Steiner: Solche Dinge, solche Bilder muß man selber finden. Man braucht nicht das historisch Gegebene zu suchen. Man sollte die freie, gezügelte Phantasie wirken lassen und Vertrauen haben zu dem, was man selber findet; auch für Tätigkeitsformen, zum Beispiel für das S. Was Sie selbst erarbeiten!

L. fragt nach der lateinischen Schrift.

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, die lateinische Schrift ist der Ausgangspunkt, weil diese die charakteristischen Formen enthält. Und dann erst, wenn es nötig wird, geht man über auf die deutsche, die gotische Schrift, die eigentlich ganz verschwinden sollte.

O. fragt nach der Behandlung der melancholischen Kinder.

Rudolf Steiner: Der Lehrer steht so gegenüber dem melancholischen Kinde: Die melancholische Anlage beruht auf einem nicht ganz vollständigen Unterkriegen des Stoffwechsels durch den geistig-seelischen Menschen. Der Nerven-Sinnesmensch ist der ungeistigste Teil des Menschen, ist der physischste Mensch. Am wenigsten physisch ist der Stoffwechselmensch. Der geistige Mensch steckt am meisten im Stoffwechselorganismus, ist dort aber am wenigsten zur Realisierung gekommen. Der Stoffwechselorganismus muß am meisten bearbeitet werden. Wenn der Stoffwechsel zuviel Beschwerde macht, dann offenbart sich in dem Brüten das innerliche Streben nach dem Geiste.

In der Nähe eines melancholischen Kindes sollten wir als Lehrer möglichst viel sichtbares Interesse an den äußeren Dingen seiner Umgebung entwickeln, sollten möglichst so sein, wie wenn wir Sanguiniker wären, und sollten so die Außenwelt charakterisieren. Dem sanguinischen Kinde gegenüber verhalten wir uns ernst, geben ihm mit innerem Ernst eindringliche, langanhaltende Charakteristiken der Außenwelt. Im Nerven-Sinnesmenschen ist der Geist am meisten in den Menschen hineingestiegen, im Stoffwechselmenschen am wenigsten; da hat er am stärksten die Tendenz, sich durchzusetzen.

Es wird die Frage nach Lehrbüchern gestellt.

Rudolf Steiner: Man muß sich die gebräuchlichen ansehen. Wenn wir ohne Bücher auskommen, um so besser. Wenn die Kinder keine öffentlichen Prüfungen machen müssen, dann braucht man keine Bücher. In Osterreich müßte man die Kinder zur öffentlichen Prüfung führen. Wir müßten feststellen, wie man wünscht, daß wir das Erreichen der Lehrziele nachweisen. Das Ideal wäre, gar keine Prüfung zu haben. Die Schlußprüfung ist ein Kompromiß mit der Behörde. Man muß ohne Prüfung wissen, so und so steht es mit den Kindern. Prüfungsangst vor der Geschlechtsreife ist sehr gefährlich für die ganze physiologische Struktur des Menschen. Sie wirkt so, daß sie die physiologisch-psychologische Konstitution des Menschen treibt. Das beste wäre die Abschaffung alles Prüfungswesens. Die Kinder werden viel schlagfertiger werden.

Das Temperament schleift sich ab; gegen das zehnte Jahr wird der Temperamentsunterschied überwunden sein.

Knaben und Mädchen müßten nicht getrennt werden. Wir trennen sie nur wegen der öffentlichen Meinung. Es bilden sich Liaisons; man braucht sich darüber nicht aufzuregen, aber man wird es uns übelnehmen. Der Unterricht leidet darunter nicht, wenn der Lehrer Autorität hat.

Fachlehrer brauchen wir für die Künste, die auf den Willen wirken, auch für die Sprachen, die besonders gegeben werden. Die künstlerischen Dinge gehören dem Fachlehrer. Der Klassenlehrer hat in der Hauptsache als Einheitslehrer zu wirken. Durch seinen gesamten Unterricht wirkt er besonders auf den Intellekt und auf das Gemüt. Auf den Willen wirken die Künste: Turnen, Eurythmie, Zeichnen, Malen.

Der Lehrer steigt mit den Schülern auf bis zum Schluß. Der Lehrer der letzten Klasse wird wieder der der ersten.

First Seminar Discussion

My dear friends, in the afternoon I would like to discuss in a free manner what your teaching tasks should be, the organization of the school system, the structure of lessons, and so on. In the first few days, we will probably mainly focus on the chapter on how we should approach children.

When we encounter children, we soon see that they are of different natures, and despite mass education, even in large classes, consideration must be given to the different natures of children. First of all, regardless of everything else, we want to make ourselves aware of what is, in a sense, an ideal necessity. We need not be overly concerned that classes may be overcrowded, for a good teacher will be able to cope with overcrowded classes if it is necessary to teach them. The diversity of human beings, of children, must be taken into account.

Now, this diversity can be traced back to four basic types, and it is the most important task of the educator and teacher to really know these four basic types, which are called temperaments. Since ancient times, a distinction has been made between the four basic types of sanguine, melancholic, phlegmatic, and choleric temperaments. We will always find that the characterological nature of each child can be classified into one of these temperament classes. We must first acquire the ability to distinguish between the different types, for example, to truly distinguish between sanguine and phlegmatic from a deeper anthroposophical point of view.

In the spiritual-scientific sense, we divide the human being into the ego, the astral body, the etheric body, and the physical body. Now, of course, in the ideal human being, the harmony prescribed by the cosmic order would prevail between these four members of the human being. But in reality, this is not the case with any human being. And from this alone we can see that human nature is not actually complete as it is handed over to the physical plane, but that education and instruction should serve to make a complete human being out of the human being. One of the four elements prevails in each person, and it must be the result of education and instruction to bring about harmony between the four members.

If the ego is particularly dominant, that is, if the ego is already very strongly developed in the child, then the child will appear to us as having a melancholic temperament. It is very easy to misjudge this fact, because melancholic children are sometimes regarded as privileged beings. In fact, the melancholic disposition in children is based on a predominance of the ego in the very early years.

If the astral body predominates, then we encounter a choleric temperament.

If the etheric body predominates, then we encounter a sanguine temperament.

If the physical body predominates, then we encounter a phlegmatic temperament.

These things are structured somewhat differently in later human beings. Therefore, you will find a slight change in a lecture I gave on the temperaments. In this lecture, the temperaments were discussed in relation to the four members of the adult human being. But in the case of children, we will come to a correct judgment if we consider the structure in this way.

Now, we must keep such knowledge in the background when dealing with children and try to determine their temperament based on their entire outward appearance and behavior.

If a child is only briefly interested in all sorts of things and quickly loses interest, then we must describe them as sanguine. We should make it our business to note which children are quickly interested in external impressions and quickly lose interest, even if we have many children to educate. These children have a sanguine temperament.

Then we should know exactly which children tend to brood and ponder; these are the melancholic children. They are not easily impressed by the outside world. They brood silently within themselves, but we never have the impression that they are actually unoccupied internally. We have the impression that they are internally occupied.

If we have the opposite impression that children are not busy internally, that they are absorbed in themselves and yet show no interest in the outside world, then we are dealing with phlegmatic children.

Children who strongly express their will through a kind of raging are choleric children.

There will, of course, be many other characteristics that reveal these four temperament types in children. However, it is necessary that we spend the first few months of our teaching examining the children for these four characteristics so that we know which types they belong to. This will enable us to divide a class into four sections, four groups. It is desirable that we gradually rearrange the children. If we have classes with both genders, we will have eight groups. We will divide the boys and girls into four groups: a choleric group, a sanguine group, a phlegmatic group, and a melancholic group.

This has a very specific purpose. We teach; and while we teach, we will deal with different things, we will have different things to say, different things to show, and we as teachers will have to be aware that when we show something that is to be looked at, it is different from when we pass judgment on it. When we pass judgment, we turn to a different group than when we show something. When we have something to show that is intended to have a particular effect on the senses, we address the sanguine group with special attention. When we reflect on what has been seen, we address the melancholic children. More details will be provided later. But it is necessary that we acquire the skill of always addressing our notes and speeches to different groups. This ensures that what one group lacks is replaced by the other group. Show the melancholic children something they can judge; show the sanguine children something they can look at. In this way, they complement each other, learn from each other, and focus their interest on each other, these two groups.

You must be patient with yourself, because this approach to the world of children must become habitual. You have to have a feeling for which group to address; it has to come naturally, so to speak. If you set out to do it deliberately, you would lose your impartiality. So, as a kind of teaching habit, we should take this approach to the different temperaments into account.

Now, you should not rush your preparations, but rather strengthen yourself for the work. Therefore, I do not think that you should use the few days you have left for extensive external preparations. Nevertheless, one can only make things one's own if one processes them spiritually. It is therefore our task to proceed appropriately with this relationship between the teacher and the temperaments of the children. We want to divide the teachers in such a way that I will ask one group to deal with the sanguine temperament, a second group with the phlegmatic, a third with the melancholic, and a fourth with the choleric temperament.

I ask you to think about the following two questions: How does the temperament I have just described manifest itself in children in each of the groups? Tomorrow, in the free discussion, you will discuss: First, how you believe the temperament in question manifests itself in the child. Second, how to deal with the temperament.

I would like to say a few more words about this “dealing with.” You can already see from the lecture I gave years ago that the worst method is to try to overcome a temperament by cultivating the opposite characteristics in the child. Let's assume we have a sanguine child. If we want to train it by trying to drive out these characteristics, we will be treating it badly. What is important is that we respond to the temperament, accommodate it, bring as much as possible into the sphere of the sanguine child's attention, let it be sensitively occupied, and thereby accommodate its inclinations. As a result, this predisposition, in which it is locked, will gradually diminish and harmonize with the other temperaments.

Furthermore, with a choleric, raging child, we should not try to prevent it from raging, but rather try to deal with its raging characteristics in such a way that we accommodate the child in the right way from the outside. Now, it is difficult to always let a child rage.

There is a clear difference between a phlegmatic and a choleric child. A phlegmatic child is apathetic and not very busy internally. As a teacher, try to muster a great deal of sympathy for such a child within yourself, to awaken an interest in every movement of the child's life. There is always an opportunity to do so. The phlegmatic child can become very interesting if you find a way to access their apathy. But do not express this inner interest; try to appear apathetic. Try to split your own nature. Be very interested inwardly, but outwardly behave in such a way that the child sees the reflection of their own nature in you. Then you will be able to have an educational influence.

With a choleric child, on the other hand, try to become indifferent internally, to watch with a cool head when they rage. For example, if they throw the inkwell on the floor, try to be as phlegmatic and calm as possible outwardly in response to this rage, and do not be moved by anything! On the contrary, try to discuss as much of these things as possible with the child in a sympathetic manner, but not immediately afterwards! Remain as calm as possible and say as calmly as possible: “You have now broken the inkwell.” The next day, when the child is calm, discuss the matter with them sympathetically. Talk about what they have done and show the greatest sympathy. In this way, you force the child to repeat and review the whole scene in their memory afterwards. Calmly condemn the actions of throwing the inkwell on the floor and smashing it. In this way, you can achieve a great deal with raging children. There is no other way to get them to stop raging.

This can guide you on your way to trying to address the two questions we will be asking ourselves by tomorrow. We will approach this in such a way that each of you can present what you have to say. Make brief notes about what you have thought of, and these notes will then be discussed.

There must always be time for discussions of this and similar kinds among the teaching staff. In such discussions, which are more republican in character, a substitute must be found for the dictatorial leadership that exists in a rectorate, so that each individual teacher is constantly involved in the affairs and interests of the others. We will begin tomorrow with a kind of debate. As a basis, I would like to give you a kind of outline that you can work from.

When a person expresses themselves, you can distinguish, based on their entire mental disposition, whether they perceive something strongly or weakly; whether they feel something strongly that is external, or feel their inner states strongly.

Then we have to distinguish between change. Either one remains strong and changes little, or one remains less strong and changes a great deal. This is how temperaments differ.

If you consider this, you will simultaneously have a certain indication in the diagram. Sanguine and phlegmatic temperaments are often found side by side, and you have this in the diagram. A phlegmatic temperament never easily turns into a choleric one. They are as different as the North and South Poles. Melancholic and sanguine temperaments are also opposites. They behave in polar opposites. The temperaments that lie next to each other merge into one another and become blurred. On the other hand, it is good to follow the division into groups as follows: when you put together a phlegmatic group, it is good to have the choleric as the opposite pole and the other two, the melancholic and the sanguine, in between.

All these things go back to what was said this morning. The inner, the soul, is of the utmost importance when being with children. Children are taught and educated from soul to soul. An enormous amount plays out in the underground wires that run from soul to soul. And so an extraordinary amount plays out in relation to the choleric child when you remain indifferent, and in relation to the phlegmatic child when you are inwardly involved. Your own inner mood will have a supernatural educational effect on the child. Education happens through who you are, which in this case means what you make of yourself within the group of children. You should never lose sight of that.

But children also influence each other in the same way. And this is what is peculiar: if you divide children into four groups of the same temperament and place those of the same type next to each other, these dispositions do not reinforce each other, but cancel each other out. A group of sanguine children, for example, do not reinforce their dispositions, but wear each other down. If you then address the choleric children in class, the sanguine children pick up on this and vice versa. As a teacher, you must allow the mood of your soul to influence the child, while similar temperamental moods in the children wear each other down. Chatting with each other means an inner tendency to wear each other down, even chatting during breaks. The choleric children will chat less with each other than when they sit next to others. We must not look at and judge things externally.

Now, right from the start, I would like to point out that we will attach great importance to making lessons as focused as possible. If we do not do this, we cannot take into account all the things I have just mentioned, namely the temperaments. Therefore, we will not have what is externally called a timetable. In this respect, we will work in direct opposition to the institution that is the ideal of modern materialistic education. In Basel, for example, they talk about forty-minute sessions. They immediately follow up with something else. This means nothing less than immediately erasing everything that went on in the previous forty minutes and causing terrible confusion in the souls of the children.

We will carefully consider which subject matter is appropriate for a certain age group of children, and then we will pursue this subject matter, reading for example, for a certain period of time. This means that the child will have reading lessons in the morning for six to eight weeks, then writing will take its place, then arithmetic, so that the child concentrates on one subject throughout the entire period. So, if I wanted to outline it schematically, our lessons would consist of starting in the morning, if possible—but only if possible, because all kinds of modifications will occur—with reading, so that we read for a few weeks, then write, then do arithmetic.

We will supplement these actual lessons with what can be done in the form of storytelling. In the first school year, we will mainly tell fairy tales. In the second school year, we will endeavor to present the life of animals in narrative form. We will move from fables to the truth about how animals behave toward each other. But the lessons will be designed in such a way that the children's attention is focused on the same thing for weeks on end. Then, at the end of the school year, we will follow up with repetitions to refresh what was covered at the beginning. We will isolate and continuously cultivate only everything artistic. Either in the afternoon or, if the necessary time is available, in the morning, we should cultivate the artistic as a special form of will training.

Now, it would correspond to the ideal of teaching that the child actually needs no more than an hour and a half a day for concentrated teaching, which requires mental effort. Then we can spend another half hour telling fairy tales. In addition, there is still the possibility of adding artistic subjects for about an hour and a half. And then we would not have more than three and a half hours a day for the children up to about the age of twelve. From these three and a half hours, we would then take the little that is necessary for religious instruction on each day, so that we would also have the opportunity to teach the children in such a way that we could alternate.

So if we have many children in a class, we can arrange it so that we have one group from seven to ten and the other group of children from ten to a quarter past ten, so that we could manage with the classroom in this way.

This would be the ideal situation, as we would not have to occupy any child for more than three and a half hours. We would always have fresh children and would only have to think about what to do with the children in the large gardens during the time when there are no lessons. They are allowed to play in the open spaces in summer, but in winter, in the gym, it will be difficult to keep them occupied. One hour per week should be set aside for gymnastics and one hour for eurythmy. It will be good for the children to be able to be there when there are no lessons, so that they can play and so on. I believe that it makes no great difference whether lessons begin first thing in the morning or later, so that we can divide them into two groups.

Now you will have the task of dealing with all sorts of things. We will gradually come to the integration of the work by dealing with it in our discussion. But I think it will be good if you consider what you need to cultivate with the children in the storytelling hour, so to speak. The actual lessons will then be based on our general pedagogical principles. But for the storytelling lessons, you will have to select material that will be presented to the children in a free, narrative tone throughout their school years from the age of seven to fourteen.

It will therefore be necessary to have a certain treasure trove of fairy tales available in the first years of school. Then, for the following period, you would have to deal with stories from the animal world in connection with fables. Then biblical history, included in general history, outside of other religious instruction. Then scenes from ancient history, scenes from medieval history, and scenes from modern history. Then you must put yourself in a position to tell stories about the tribes, what the tribes are like, which is more related to the natural environment. Then the mutual relationships of the tribes, Indians, Chinese, Americans, what their peculiarities are and so on, that is, knowledge of the peoples. This is a very special necessity arising from the present era.

I wanted us to set ourselves these particular tasks today. You will then see how we will use these seminar hours. Today, everything should be laid out clearly.

While speaking, Rudolf Steiner wrote the following overview on the blackboard:

1. A certain treasure trove of fairy tales

2. Stories from the animal world in connection with fables

3. Biblical history as part of general history (Old Testament)

4. Scenes from ancient history

5. Scenes from medieval history

6. Scenes from modern history

7. Stories about the tribes

8. Knowledge of the peoples.

Question and answer session

Questions are asked about the images for sounds and letters, such as the fish for the letter F, which was discussed in the morning during the first lecture of the methodological-didactic course.

Rudolf Steiner: You have to find such things, such images, yourself. There is no need to search for historical references. One should let one's free, restrained imagination work and have confidence in what one finds oneself, including forms of activity, for example for the S. What you work out yourself!

L. asks about the Latin alphabet.

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, Latin script is the starting point because it contains the characteristic forms. And only when it becomes necessary do you move on to German, Gothic script, which should actually disappear completely.

O. asks about the treatment of melancholic children.

Rudolf Steiner: The teacher stands in this way opposite the melancholic child: The melancholic disposition is based on the spiritual-soul human being not having complete control over the metabolism. The nervous-sensory human being is the least spiritual part of the human being, the most physical human being. The least physical is the metabolic human being. The spiritual human being is most present in the metabolic organism, but has achieved the least realization there. The metabolic organism needs the most work. When the metabolism causes too much discomfort, the inner striving for the spirit reveals itself in brooding.

As teachers, we should develop as much visible interest as possible in the external things of the environment of a melancholic child, we should be as much like sanguine people as possible, and we should characterize the outside world in this way. We behave seriously toward the sanguine child, giving them emphatic, long-lasting characteristics of the outside world with inner seriousness. In the nervous-sensory person, the spirit has entered most deeply into the human being, and least in the metabolic person; there it has the strongest tendency to assert itself.

The question of textbooks is raised.

Rudolf Steiner: We must look at the ones in common use. If we can manage without books, so much the better. If the children do not have to take public examinations, then there is no need for books. In Austria, the children would have to take public examinations. We would have to determine how we want to demonstrate that the teaching goals have been achieved. The ideal would be to have no exams at all. The final exam is a compromise with the authorities. Without exams, one must know how the children are doing. Exam anxiety before puberty is very dangerous for the entire physiological structure of the human being. It has the effect of driving the physiological and psychological constitution of the human being. The best thing would be to abolish all examinations. Children will become much more quick-witted.

Temperament wears off; by the age of ten, differences in temperament will have been overcome.

Boys and girls should not be separated. We separate them only because of public opinion. Liaisons form; there is no need to get upset about this, but people will resent us for it. Teaching does not suffer if the teacher has authority.

We need specialist teachers for the arts, which influence the will, and also for languages, which are taught separately. Artistic subjects belong to the specialist teacher. The class teacher's main role is to act as a unified teacher. Through all his teaching, he has a particular effect on the intellect and the mind. The arts have an effect on the will: gymnastics, eurythmy, drawing, painting.

The teacher accompanies the students to the end. The teacher of the last class becomes the teacher of the first class again.