Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

22 August 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Two

A report was presented on the following questions: How is the sanguine temperament expressed in a child? How should it be treated?

RUDOLF STEINER: This is where our work of individuating begins. We have said that we can group children according to temperament. In the larger groups children can all take part in the general drawing lesson, but by dividing them into smaller groups we can personalize to some extent. How is this individuating to be done? Copying will play a very small part, but in drawing you will try to awaken an inner feeling for form so that you can individuate. You will be able to differentiate by your choice of forms by taking either forms with straight lines or those with more movement in them—by taking simpler, clearer forms, or those with more detail. The more complicated, detailed forms would be used with the child whose temperament is sanguine. From the various temperaments you can learn how to teach each individual child.

A report was given on the same theme.

RUDOLF STEINER: We must also be very clear that there is no need to make our methods rigidly uniform, because, of course, one teacher can do something that is very good in a particular case, and another teacher something else equally good. So we need not strive for pedantic uniformity, but on the other hand we must adhere to certain important principles, which must be thoroughly comprehended.

The question about whether a sanguine child is difficult or easy to handle is very important. You must form your own opinion about this and you must be very clear. For example, suppose you have to teach or explain something to a sanguine child. The child has taken it in, but after some time you notice that the child has lost interest—attention has turned to something else. In this way the child’s progress is hindered. What would you do if you noticed, when you were talking about a horse, for example, that after awhile the sanguine child was far away from the subject and was paying attention to something entirely different, so that everything you were saying passed unnoticed? What would you do with a child like this?

In such a case much depends on whether or not you can give individual treatment. In a large class many of your guiding principles will be difficult to carry out. But you will have the sanguine children together in a group, and then you must work on them by showing them the melancholic pattern. If there is something wrong in the sanguine group, turn to the melancholic group and then bring the melancholic temperament into play so that it acts as an antidote to the other. In teaching large numbers you must pay great attention to this. It’s important that you should not only be serious and restful in yourself, but that you should also allow the serious restfulness of the melancholic children to act on the sanguine children, and vice versa.

Let’s suppose you are talking about a horse, and you notice that a child in the sanguine group has not been paying attention for a long time. Now try to verify this by asking the child a question that will make the lack of attention apparent. Then try to verify that one of the children in the melancholic group is still thinking about some piece of furniture you were talking about quite awhile ago, even though you have been speaking about the horse during that time. Make this clear by saying to the sanguine child, “You see, you forgot the horse a long time ago, but your friend over there is still thinking about that piece of furniture!”

A real situation of this kind works very strongly. In this way children act correctively on each other. It is very effective when they come to see themselves through these means. The subconscious soul has a strong feeling that such lack of cooperation will prevent a continuation of social life. You must make good use of this unconscious element in the soul, because teaching large numbers of children can be an excellent way to progress if you let your pupils wear off each other’s corners. To bring out the contrast you must have a very light touch and humor, so that the children see you are never annoyed nor bear a grudge against them—that things are revealed simply through your method of handling them.

The phlegmatic child was spoken of.

RUDOLF STEINER: What would you do if a phlegmatic child simply did not come out of herself or himself at all and nearly drove you to despair?

Suggestions were presented for the treatment of temperaments from the musical perspective and by relating them to Bible history.

Phlegmatics: Harmonium and piano; Harmony; Choral singing; The Gospel of Matthew; (variety)

Sanguines: Wind instruments; Melody; Whole orchestra; The Gospel of Luke; (Inwardness of soul)

Cholerics: Percussion and drum; Rhythm; Solo instruments; The Gospel of St. Mark; (Force, strength) Melancholics: Stringed Instruments; Counterpoint; Solo singing; The Gospel of St. John; (Deepening of the spirit)

RUDOLF STEINER: Much of this is very correct, especially the choice of instruments and musical instruction. Equally good is the contrast of solo singing for the melancholic, the whole orchestra for the sanguine, and choral singing for the phlegmatic. All this is very good, and also the way you have related the temperaments to the four Evangelists. But it wouldn’t be as good to delegate the four arts according to temperaments; it is precisely because art is multifaceted that any single art can bring harmony to each temperament.1 The teacher who presented the above suggestions had also allocated particular arts to the various temperaments. Within each art the principle is correct, but I would not distribute the arts themselves in this way. For example, you could in some circumstances help a phlegmatic child very much through something that appeals to the child in dancing or painting. Thus the child would not be deprived of whatever might be useful in any of the various arts. In any single art it is possible to allocate the various branches and expressions of the art according to temperament. Whereas it is certainly necessary to prepare everything in the best way for individual children, it would not be good here to give too much consideration to the temperaments.

An account was given about the phlegmatic temperament and it was stated that the phlegmatic child sits with an open mouth.

RUDOLF STEINER: That is incorrect; the phlegmatic child will not sit with the mouth open but with a closed mouth and drooping lips. Through this kind of hint we can sometimes hit the nail on the head. It was very good that you touched on this, but as a rule it is not true that a phlegmatic child will sit with an open mouth, but just the opposite. This leads us back to the question of what to do with the phlegmatic child who is nearly driving us to despair. The ideal remedy would be to ask the mother to wake the child every day at least an hour earlier than the child prefers, and during this time (which you really take from the child’s sleep) keep the child busy with all kinds of things. This will not hurt the child, who usually sleeps much longer than necessary anyway. Provide things to do from the time of waking up until the usual waking hour. That would be an ideal cure. In this way, you can overcome much of the child’s phlegmatic qualities. It will not be possible very often to get parents to cooperate in this way, but much could be accomplished by carrying out such a plan.

You can however do the following, which is only a substitute but can help greatly. When your group of phlegmatics sit there (not with open mouths), and you go past their desks as you often do, you could do something like this: [Dr. Steiner jangled a bunch of keys]. This will jar them and wake them up. Their closed mouths would then open, and exactly at this moment when you have surprised them, you must try to occupy them for five minutes! You must rouse them, shake them out of their lethargy by some external means. By working on the unconscious you must combat this irregular connection between the etheric and physical bodies. You must continually find fresh ways to jolt the phlegmatics, thus changing their drooping lips to open mouths, and that means that you will be making them do just what they do not like doing. This is the answer when the phlegmatics drive you to despair, and if you keep trying patiently to shake up the phlegmatic group in this way, again and again, you will accomplish much.

Question: Wouldn’t it be possible to have the phlegmatic children come to school an hour earlier?

RUDOLF STEINER: Yes, if you could do that, and also see that the children are wakened with some kind of noise, that would naturally be very good; it would be good to include the phlegmatic children among those who come earliest to school.2This refers to the need for having school in shifts. The important thing with the phlegmatic children is to engage their attention as soon as you have changed their soul mood.

The subject of food in relation to the different temperaments was introduced.

RUDOLF STEINER: On the whole, the main time for digestion should not be during school hours, but smaller meals would be insignificant; on the contrary, if the children have had their breakfast they can be more attentive than when they come to school on empty stomachs. If they eat too much—and this applies especially to phlegmatic children—you cannot teach them anything. Sanguine children should not be given too much meat, nor phlegmatic too many eggs. The melancholic children, on the other hand, can have a good mixed diet, but not too many roots or too much cabbage. For melancholic children diet is very individual, and you have to watch that. With sanguine and phlegmatic children it is possible to generalize.

The melancholic temperament was spoken of.

RUDOLF STEINER: That was very good. When you teach you will also have to realize that melancholic children get left behind easily; they do not keep up easily with others. I ask you to remember this also.

The same theme was continued.

RUDOLF STEINER: It was excellent that you stressed the importance of the teacher’s attitude toward the melancholic children. Moreover, they are slow in the birth of the etheric body, which otherwise becomes free during the change of teeth. Therefore, these children have a greater aptitude for imitation; if they have become fond of you, everything you do in front of them will make a lasting impression on them. You must use the fact that they retain the principle of imitation longer than others.

A further report on the melancholic temperament.

RUDOLF STEINER: You will find it very difficult to treat the melancholic temperament if you fail to consider one thing that is almost always present: the melancholic lives in a strange condition of self-deception. Melancholics have the opinion that their experiences are peculiar to themselves. The moment you can bring home to them that others also have these or similar experiences, they will to some degree be cured, because they then perceive they are not the singularly interesting people they thought themselves to be. They are prepossessed by the illusion that they are very exceptional as they are.

When you can impress a melancholic child by saying, “Come on now, you’re not so extraordinary after all; there are plenty of people like you, who have had similar experiences,” then this will act as a very strong corrective to the impulses that lead to melancholy. Because of this it is good to make a point of presenting them with the biographies of great persons; they will be more interested in these individuals than in external nature. Such biographies should be used especially to help these children over their melancholy.

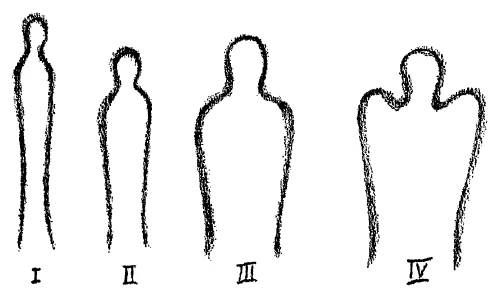

Two teachers spoke about the choleric temperament. Rudolf Steiner then drew the following figures on the board:

What do we see in these figures? They depict another characterization of the four temperaments. The melancholic children are as a rule tall and slender; the sanguine are the most normal; those with more protruding shoulders are the phlegmatic children; and those with a short stout build so that the head almost sinks down into the body are choleric.

Both Michelangelo and Beethoven have a combination of melancholic and choleric temperaments. Please remember particularly that when we are dealing with the temperament of a child, as teachers we should not assume that a certain temperament is a fault to be overcome. We must recognize the temperament and ask ourselves the following question: How should we treat it so that the child may reach the desired goal in life—so that the very best may be drawn out of the temperament and with the help of their own temperaments, children can reach their goals.

Particularly in the case of the choleric temperament, we would help very little by trying to drive it out and replacing it with something else. Indeed, much arises from the life and passion of choleric people—especially when we look at history and find that many things would have happened differently had there been no cholerics. So we must make it our task to bring the child, regardless of the temperament, to the goal in life belonging to that child’s nature.

For the choleric you should use as much as possible fictional situations, describing situations you have made up for the occasion, and that you bring to the child’s attention. If, for example, you have a child with a temper, describe such situations to the child and deal with them yourself, treating them in a choleric way. For example, I would tell a choleric child about a wild fellow whom I had met, whom I would then graphically describe to the child. I would get roused and excited about him, describing how I treated him, and what I thought of him, so that the child sees temper in someone else, in a fictitious way the child sees it in action. In this way you will bring together the inner forces of such a child, whose general power of understanding is thus increased.

The teachers asked Rudolf Steiner to relate the scene between Napoleon and his secretary.

Rudolf Steiner: For this you would first have to get permission from the Ministry of Housing! Through describing such a scene the choleric element would have to be brought out. But a scene such as I just mentioned must be described by the teacher so that the choleric element is apparent. This will always arouse the forces of a choleric child, with whom you can then continue to work. It would be ideal to describe such a situation to the choleric group in order to arouse their forces, the effect of which would then last a few days. During that few days the children will have no difficulty taking in what you want to teach them. Otherwise they fume inwardly against things that they should be getting through their understanding.

Now I would like you to try something: we should have a record of what we have been saying about the treatment of temperaments, and so I should like to ask Miss B. to write a comprehensive survey (approximately six pages) of the characteristics of the different temperaments and how to treat them, based on everything I have spoken about here. Also, I will ask Mrs. E. to imagine she has two groups of children in front of her, sanguine and melancholic and then, in a kind of drawing lesson, to use simple designs, varied according to sanguine and melancholic children. I will ask Mr. T. to do the same thing with drawings for phlegmatic and choleric children; and please bring these tomorrow when you have prepared them.

Then I will ask, let us say, Miss A., Miss D., and Mr. R. to deal with a problem: Imagine that you have to tell the same fairy tale twice—not twice in the same way, but clothed in different sentences, and so on. The first time pay more attention to the sanguine and the second time to the melancholic children, so that both get something from it.

Then I ask that perhaps Mr. M. and Mr. L. work at the difficult task of giving two separate descriptions of an animal or animal species, first for the cholerics and then for the phlegmatics. And I will ask Mr. O., Mr. N., and perhaps with the help of Mr. U. to solve the problem of how to consider the four temperaments in arithmetic.

When you consider something like the temperaments in working out your lessons, you must remember above all that the human being is constantly becoming, always changing and developing. This is something that we as teachers must have always in our consciousness—that the human being is constantly becoming, that in the course of life human beings are subject to metamorphosis. And just as we should give serious consideration to the temperamental dispositions of individual children, so we must also reflect on the element of growth, this becoming, so that we come to see that all children are primarily sanguine, even if they are also phlegmatic or choleric in certain things. All adolescents, boys and girls, are really cholerics, and if this is not so at this time of life it shows an unhealthy development. In mature life a person is melancholic and in old age phlegmatic.

This again sheds some light on the question of temperaments, because here you have something particularly necessary to remember at the present time. In our day we love to make fixed, sharply defined concepts. In reality, however, everything is interwoven so that, even while you are saying that a person is made up of head, breast, and limb organizations, you must be clear that these three really interpenetrate one another. Thus a choleric child is only mostly choleric, a sanguine mostly sanguine, and so on. Only at the age of adolescence can one become completely choleric. Some people remain adolescents till they die, because they preserve this age of adolescence within themselves throughout life. Nero and Napoleon never outgrew the age of youth. This shows us how qualities that follow each other during growth can still—through further change—permeate each other again.

What is the poet’s productivity actually based on—or indeed any spiritually creative power? How does it happen that a man, for example, can become a poet? It is because he has preserved throughout his whole life certain qualities that belonged to early manhood and childhood. The more such a man remains “young,” the more aptitude he has for the art of poetry. In a certain sense it is a misfortune for such a man if he cannot keep some of the qualities of youth, something of a sanguine nature, his whole life through. It is very important that teachers can become sanguine out of their own resolve. And it is moreover tremendously important for teachers to remember this so they may cherish this happy disposition of the child as something of particular value.

All creative qualities in life—everything that fosters the spiritual and cultural side of the social organism—all of this depends on the youthful qualities in a human being. These things will be accomplished by those who have preserved the temperament of youth. All economic life, on the other hand, depends on the qualities of old age finding their way into people, even when they are young. This is because all economic judgment depends on experience. Experience is best gained when certain qualities of old age enter into people, and the old person is indeed a phlegmatic. Those business people prosper most whose other attributes and qualities have an added touch of the phlegmatic, which really already bears the stamp of old age. That is the secret of very many business people—that in addition to their other good qualities as business people, they also have something of old age about them, especially in the way they manage their businesses. In the business world, a person who only developed the sanguine temperament would only get as far as the projects of youth, which are never finished. A choleric who remains at the stage of youth might spoil what was done earlier in life through policies adopted later. The melancholic cannot be a business person anyway, because a harmonious development in business life is connected with a quality of old age. A harmonious temperament, along with some of the phlegmatic’s unexcitability is the best combination for business life.

You see, if you are thinking of the future of humankind you must really notice such things and consider them. A person of thirty who is a poet or painter is also something more than “a person of thirty,” because that individual at the same time has the qualities of childhood and youth within, which have found their way into the person’s being. When people are creative you can see how another being lives in them, in which they have remained more or less childlike, in which the essence of childhood still dwells. Everything I have exemplified must become the subject of a new kind of psychology.

Zweite Seminarbesprechung

L. berichtet über die Fragen: Erstens, wie äußert sich das sanguinische Temperament im Kinde, und zweitens, wie hat man es zu behandeln?

Rudolf Steiner: Hier beginnen ja die Individualisierungen. Wir haben gesagt, daß wir nach den Temperamenten einteilen können. Man muß ja das Kind im Massenunterricht mit an dem allgemeinen Zeichenunterricht beschäftigen, und nun können wir bei den einzelnen Gruppen etwas individualisieren. Dann würde es sich darum handeln, in welcher Hinsicht Sie den Zeichenunterricht individualisieren wollten. Nachahmung wird man überhaupt weniger pflegen. Man wird im Zeichnen versuchen, das innere Formgefühl zu erwecken. Man wird nur darin individualisieren können. Man wird einen Unterschied machen können, ob man mehr geradlinige Formen oder mehr bewegte, ob man mehr einfache, übersichtliche Formen nimmt oder solche mit mehr Details. Kompliziertere, mehr Detailformen, würden für das Kind mit sanguinischem Temperament zu verwenden sein. Man wird nach dem "Temperament mehr die Art bestimmen, wie man den einen oder den anderen unterrichtet.

E. berichtet über dasselbe Thema.

Rudolf Steiner: Nicht wahr, bei solchen Dingen muß man sich immer ganz klar sein, daß namentlich die Behandlung doch nicht eindeutig sein muß. Es kann natürlich von dem einen etwas gemacht werden, was ganz gut ist in einem solchen Fall, und von dem anderen etwas anderes, was auch gut ist. Also die pedantische Eindeutigkeit braucht nicht angestrebt zu werden, doch gewisse große Richtlinien muß man schon einhalten, die müssen durchdrungen werden.

Die Frage, ob ein sanguinisches Kind schwer oder leicht zu behandeln ist, ist schon sehr bedeutsam. Darüber müßte man sich schon eine Ansicht verschaffen und sich zum Beispiel folgendes klarmachen: Es kann passieren bei einem sanguinischen Kinde, daß man irgend etwas vorzubringen, zu erklären hat. Das Kind hat wohl die Sache aufgenommen, aber nach einiger Zeit merkt man, es ist gar nicht mehr dabei, sondern hat sich einer anderen Sache zugewendet. Dadurch wird der Fortschritt des Kindes beeinträchtigt. Was würden Sie tun, wenn Sie bemerken würden, Sie reden in der Schule vom Pferde, und nach einiger Zeit hat sich das sanguinische Kind sehr weit entfernt vom Gegenstande und hat seine Aufmerksamkeit einem ganz anderen Gegenstande zugewendet, so daß alles, was Sie besprechen, an seinen Ohren vorbeigehen könnte? Was würden Sie mit einem solchen Kinde tun?

Viel wird ja davon abhängen, wie weit man in solchem Falle individualisieren kann oder nicht. Hat man viele Kinder, so werden viele Maßregeln nicht leicht durchzuführen sein. Man hat ja, wenn man viele Kinder hat, die sanguinischen Kinder in einer Gruppe beisammen. Dann muß man vorbildlich wirken auf die sanguinischen durch die melancholischen Kinder. Wenn in der sanguinischen Gruppe irgend etwas nicht stimmt, sich zur melancholischen Gruppe wenden und dieses Temperament dann spielen lassen, um ausgleichend zu wirken! Gerade beim Massenunterricht ist das sehr ins Auge zu fassen. Da ist es wichtig, daß man nicht bloß selber den Ernst und die Ruhe bewahrt, sondern daß man den Ernst und die Ruhe der melancholischen Kinder in Wechselwirkung treten läßt mit der sanguinischen Gruppe.

Nehmen wir an, Sie sprechen über das Pferd. Sie sehen, ein sanguinisches Kind aus der Gruppe, das ist längst nicht mehr dabei. Jetzt versuchen Sie das zu konstatieren. Indem Sie das Kind etwas fragen, machen Sie, daß es wirklich hervortritt, daß das Kind nicht mehr dabei ist. Dann versuchen Sie, in der melancholischen Gruppe die Tatsache zu konstatieren, daß ein Kind, während Sie früher vom Kleiderschrank gesprochen haben und jetzt schon lange vom Pferd sprechen, noch immer an den Kleiderschrank denkt. Konstatieren Sie das: «Sieh, du hast schon längst das Pferd vergessen, dein Freund ist noch nicht vom Kleiderschrank weggekommen!»

Solche Tatsachen wirken stark. Auf diese Weise schleifen sich die Kinder aneinander ab. Dieses Selbstsehen der Kinder hat eine starke Wirkung. Die unterbewußte Seele hat ein starkes Gefühl davon, daß bei solchem Nicht-miteinander-Mitkommen das soziale Leben nicht weitergeht. Dieses Unbewußte in der Seele muß man stark benützen, dann kann sogar der Massenunterricht ein außerordentlich gutes Mittel sein, um vorwärtszukommen, wenn man die Eigenschaften der Kinder aneinander abschleift. Um den Kontrast zu zeigen, muß man eine wirklich leichte Hand haben und den Humor, so daß die Kinder sehen: man ärgert sich nie, man hat auch keinen Groll, sondern man behandelt die Dinge so, daß sie sich selber zeigen.

T. spricht über das phlegmatische Kind.

Rudolf Steiner: Was würden Sie tun, wenn ein phlegmatisches Kind nun gar nicht herauskommt und Sie zur Verzweiflung bringt?

U. berichtet über die Behandlung der Temperamente vom musikalischen Standpunkt aus und in bezug auf die biblische Geschichte.

Phlegmatiker: Harmonium und Klavier Harmonie; Chorgesang

Sanguiniker: Blasinstrumente Melodie Rhythmus; ganzes Orchester

Choleriker: Schlagzeuge und Trommel; Soloinstrumente

Melancholiker: Streichinstrumente Kontrapunkt (was mehr intellektuell durchgearbeitet werden muß); Sologesang

In bezug auf die biblische Geschichte:

Matthäus Evangelium (Mannigfaltigkeit)

Lukas Evangelium (Innigkeit)

Markus Evangelium (Kraft)

Johannes Evangelium (Geistige Vertiefung)

Rudolf Steiner: Es ist vieles sehr richtig, namentlich auch in bezug auf die Instrumente und die Wahl des musikalischen Unterrichts. Ebensogut ist der Gegensatz von Sologesang beim Melancholiker, dem ganzen Orchester beim Sanguiniker, und Chorgesang beim Phlegmatiker. Die Dinge sind sehr gut, und auch die Evangelisten sind sehr gut. Aber die vier Künste sind deshalb weniger den Temperamenten zuzuteilen, weil es möglich ist, gerade durch die Vielheit des Künstlerischen auf jedes Temperament ausgleichend zu wirken. Innerhalb der einzelnen Kunst ist das Prinzip sehr richtig, aber ich würde nicht die Künste selbst verteilen. In bezug auf die Musik ist das richtig. Wenn Sie zum Beispiel den Phlegmatiker haben, können Sie unter Umständen sehr gut durch etwas, was ihn im Tanz ergreift oder in der Malerei ergreift, auf ihn wirken. Da möchte ich nicht verzichten auf das, was in den verschiedenen Künsten auf ihn wirken kann. In der einzelnen Kunst wird es wieder möglich sein, die Richtungen und Betätigungsgebiete der Kunst auf die Temperamente zu verteilen. Es würde nicht gut sein, wenn man da den Temperamenten zuviel nachgibt, während es doch notwendig ist, alles so zuzubereiten, wie es für die einzelnen richtig ist.

O. berichtet über das phlegmatische Temperament und sagt, daß das Kind mit offenem Munde dasitzt.

Rudolf Steiner: Sie sind im Irrtum; das phlegmatische Kind wird nicht mit offenem Munde dasitzen, sondern mit zugemachtem Munde, aber mit hängenden Lippen. Man kann schon manchmal durch einen solchen Hinweis den Nagel auf den Kopf treffen. Dies zu berühren war sehr gut. Es wird in der Regel aber nicht der Fall sein; das phlegmatische Kind wird nicht mit offenem Munde dasitzen, sondern im Gegenteil. Das führt zurück auf die Frage: Wie kann man sich dem phlegmatischen Kinde gegenüber verhalten, wenn es uns zur Verzweiflung bringt?

Das Idealste, das man tun könnte, das wäre, die Mutter des Kindes zu bitten, es immer wenigstens eine Stunde früher aufzuwecken, als es gewohnt ist zu erwachen, und in dieser Zeit, die man ihm eigentlich wegnimmt — man wird es nicht beeinträchtigen, weil es in der Regel immer viel länger schläft als nötig —, es mit allem möglichen zu beschäftigen. Von der Zeit an, wo man es aufgeweckt hat, bis zu der Zeit, wo es sonst aufzuwachen gewohnt war, wird man es beschäftigen; das würde ein ideales Kurieren sein. Auf diese Weise würde man viel von seinem Phlegma wegnehmen. Das wird man in der Regel nicht können, weil die Eltern sich nicht darauf einlassen werden, aber man würde sehr viel damit tun können.

Man wird folgendes tun können, was ein Surrogat ist, was aber viel helfen kann: Wenn die Gruppe so dasitzt — mit offenem Munde wird sie nicht dasitzen — und Sie vorbeigehen, und Sie gehen öfter vorbei, könnten Sie so etwas machen (Dr. Steiner schlägt mit einem Schlüsselbund auf den Tisch), wodurch Sie einen Schock hervorrufen, um die Kinder aufzuwecken, wodurch die Kinder dann übergehen von dem zugemachten zu dem offenen Mund. In diesem Moment, wo Sie sie schockiert haben, versuchen Sie, sie während fünf Minuten zu beschäftigen. Man muß sie durch eine äußere Veranlassung aus ihrer Lethargie herausbringen, aufstampern. Man muß dadurch, daß man auf das Unbewußte wirkt, dieses unregelmäßige Verbundensein des Ätherleibes mit dem physischen Körper bekämpfen. Man wird immer wieder ein anderes Mittel finden müssen, das sie schockiert und sie dadurch von ihren hängenden Lippen zum offenen Munde bringt; das also gerade das hervorruft, was sie nicht gerne tun. So wäre diese Frage zu behandeln, wenn diese Kinder einen zur Verzweiflung bringen. Wenn man das mit Geduld fortsetzt und wirklich die phlegmatische Gruppe immerzu in dieser Weise aufrüttelt, dann wird man gerade da viel erreichen.

T.: Wäre es nicht möglich, die phlegmatischen Kinder eine Stunde früher zur Schule kommen zu lassen?

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, wenn man das machen würde und es dazu bringen könnte, daß die Kinder mit einem gewissen Geräusch aufgeweckt werden, das wäre natürlich sehr gut. Da wäre es auch gut, die phlegmatische Gruppe zu den am frühesten in die Schule Kommenden einzureihen. Wichtig ist beim Phlegmatiker, daß man aus einem veränderten Seelenzustand heraus seine Aufmerksamkeit in Anspruch nimmt.

Es wird die Frage der Ernährung für Kinder der verschiedenen Temperamente angeschnitten.

Rudolf Steiner: Man wird überhaupt darauf zu sehen haben, daß nicht gerade die Hauptverdauungszeit zugleich die Schulzeit ist, aber kleinere Mahlzeiten werden keine zu große Bedeutung haben. Im Gegenteil, wenn die Kinder gefrühstückt haben, werden sie besser aufpassen können, als wenn sie mit hungrigem Magen kommen. Wenn man sie natürlich überfüttert, was bei den phlegmatischen Kindern sehr in Betracht kommen wird, dann wird man ihnen gar nichts beibringen können. Den sanguinischen Kindern wäre nicht allzuviel Fleisch, den phlegmatischen nicht zuviel Eier zu geben. Dagegen können die melancholischen Kinder immerhin eine gut gemischte Nahrung bekommen, aber nicht allzuviel Wurzelzeug und Kohl. Bei melancholischen Kindern ist die Nahrung sehr individuell, da muß man beobachten. Bei sanguinischen und phlegmatischen Kindern kann man schon generalisieren. Es folgen Ausführungen von D. über das melancholische Temperament der Kinder.

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, das war sehr schön. Für den Unterricht wird aber noch das in Betracht kommen, daß melancholische Kinder leicht zurückbleiben, daß sie nicht leicht mitkommen. Das bitte ich noch zu berücksichtigen.

A. spricht über dasselbe Thema.

Rudolf Steiner: Da ist die Bemerkung sehr gut, daß es sich bei melancholischen Kindern sehr darum handelt, wie man sich selbst zu ihnen stellt. Sie bleiben zurück auch mit dem Geborenwerden des Ätherleibes, der sonst mit dem Zahnwechsel frei wird. Daher sind diese Kinder viel zugänglicher für die Nachahmung. Was man ihnen vormacht, daran halten sie fest, wenn sie einen liebgewonnen haben. Das muß man bei ihnen benützen, daß sie das Imitationsprinzip länger haben.

N. berichtet ebenfalls über das melancholische Temperament.

Rudolf Steiner: Besonders bitte ich zu berücksichtigen, daß man das melancholische Temperament sehr schwer wird behandeln können, wenn man nicht eins betrachtet, was fast immer da ist: der Melancholiker ist in einer merkwürdigen Selbsttäuschung; er ist der Meinung, daß die Erlebnisse, die er hat, nur ihn selbst betreffen. In dem Augenblick, wo man ihm beibringt, daß andere Leute diese und ähnliche Erlebnisse auch haben, ist das immer eine Art Kur für ihn, weil er bemerkt, daß er nicht allein so eine interessante Individualität ist, wie er glaubt. In dieser Illusion ist er befangen, daß er ganz auserlesen ist, so wie er gerade ist. Läßt man ihn das stark merken: «Du bist kein solch außerordentlicher Kerl, solche Exemplare gibt es viele, die das oder jenes erleben», dann ist das eine sehr starke Beeinträchtigung der Impulse, die gerade zur Melancholie führen. Deshalb ist es gut, ihn besonders mit Biographien großer Persönlichkeiten zu behandeln. Er wird sich weniger interessieren für die äußere Natur, aber mehr für die einzelnen Persönlichkeiten. Diese Biographien sollte man besonders gebrauchen, um ihn über seine Melancholie hinwegzubringen.

Zwei Lehrer berichten über das cholerische Temperament.

Rudolf Steiner zeichnet folgende Figuren an die Tafel:

Was ist das? Das ist auch eine Charakterisierung der vier Temperamente. Die melancholischen Kinder sind in der Regel schlank und dünn; die sanguinischen sind die normalsten; die, welche die Schultern mehr heraus haben, sind die phlegmatischen Kinder; die den untersetzten Bau haben, so daß der Kopf beinah untersinkt im Körper, sind die cholerischen Kinder.

Bei Michelangelo und Beethoven haben Sie eine Mischung von melancholischem und cholerischem Temperament.

Nun bitte ich, durchaus zu berücksichtigen, daß wir, wenn es sich um das Temperament beim Kinde handelt, als Lehrer durchaus nicht berufen sind, die betreffenden Temperamente von vornherein als «Fehler» anzusehen und bekämpfen zu wollen. Wir müssen das Temperament erkennen und uns die Frage stellen: Wie haben wir es zu behandeln, um ein wünschbares Lebensziel mit ihm zu erreichen, so daß aus dem Temperament das Allerbeste wird und die Kinder mit Hilfe des Temperaments das Lebensziel erreichen? Gerade beim cholerischen Temperament würde es ja sehr wenig helfen, wenn wir es austreiben wollten und etwas anderes an seine Stelle setzten. In der Tat geht aus dem Leben und der Leidenschaft des Cholerikers sehr viel hervor, und insbesondere in der Weltgeschichte wäre vieles anders geworden, wenn es nicht die Choleriker gegeben hätte. Aber gerade beim Kind muß man sehen, daß man es trotz seines Temperaments zu entsprechenden Lebenszielen bringt.

Beim Choleriker sind möglichst zu berücksichtigen erdichtete Situationen, künstlich gebildete Situationen, die man in die Aufmerksamkeitssphäre des Kindes bringt. Man sollte zum Beispiel bei einem tobenden Kind die Aufmerksamkeit auf erdichtete Situationen lenken und diese erdichteten Situationen selbst cholerisch behandeln, so daß ich dem jungen Choleriker zum Beispiel erzähle von einem wilden Kerl, dem ich begegnet bin, den ich ihm vormale wie eine Wirklichkeit. Dann würde ich in Ekstase kommen, würde schildern, wie ich ihn behandle, wie ich ihn beurteile, so daß er die Cholerik an anderem sieht, an Ausgeklügeltem, so daß er die Tat sieht. Dadurch wird man in ihm die Kraft sammeln, daß er auch anderes gut begreifen kann.

Rudolf Steiner wird gebeten, die Szene zwischen Napoleon und seinem Sekretär zu erzählen.

Rudolf Steiner: Da müßte man erst die Baukommission um Erlaubnis fragen! — Diese in der Rede vorgemalte Szene müßte die redende Person so behandeln, daß Cholerisches dabei herauskommt. Das wird immer Kraft sammeln beim cholerischen Kinde, so daß man es dann weiter behandeln kann. Ein Ideal wäre: der cholerischen Gruppe eine Situation vormalen, um auf diese Weise wiederum Kraft gesammelt zu haben. Dann hält es immer ein paar Tage an. Die Kinder werden dann ein paar Tage hindurch gar nicht gehindert sein, die Dinge aufzunehmen. Sonst toben sie innerlich an gegen Dinge, die sie begreifen sollten.

Nun möchte ich, daß Sie folgendes versuchen: Von diesem Behandeln der Temperamente sollte etwas bleiben, und da würde ich Fräulein B. bitten, auf höchstens sechs Seiten eine zusammenfassende Darstellung zu geben von der Eigentümlichkeit der Temperamente und ihrer Behandlung, auf Grund alles dessen, was ich hier besprochen habe. Es braucht nicht schon morgen zu sein.

Dagegen möchte ich Frau E. bitten, sich vorzustellen, sie hätte zwei Gruppen vor sich: sanguinische Kinder und melancholische Kinder, und sie sollte so abwechseln mit einer Art Zeichenunterricht, mit einfachen Zeichenmotiven, daß das eine Mal gedient wäre den sanguinischen, das andere Mal den melancholischen Kindern.

Jetzt möchte ich außerdem noch bitten: Herr T. kann dieselbe Sache machen mit dem Zeichnen für phlegmatische und cholerische Kinder, so daß Sie uns dann dies morgen vorführen können, so wie Sie es sich zurechtgelegt haben.

Dann würde ich vielleicht Fräulein A., Fräulein D. und Herrn R. bitten, folgende Aufgaben zu behandeln: Sie denken sich, Sie sollen ein und dasselbe Märchen erzählen, zweimal hintereinander, so, daß Sie es nicht ganz gleich erzählen, sondern in verschiedene Sätze einkleiden und so weiter. Das erste Mal nehmen Sie mehr Rücksicht auf sanguinische, das zweite Mal auf melancholische Kinder, so daß beide etwas davon haben.

Dann würde ich bitten, daß Herr M. und Herr L. sich mit der schwierigen Aufgabe befassen, die individuelle Beschreibung eines Tieres oder einer Tiergattung zu geben und sie das eine Mal für cholerische, das andere Mal für phlegmatische Kinder zuzurichten.

Herr O., Herr N., und vielleicht hilft auch Herr U. mit, die würde ich bitten, einmal die Aufgabe zu lösen, wie man im Rechnen Rücksicht nehmen könnte auf die vier Temperamente, gerade nur im Rechnen.

Nicht wahr, wenn Sie nun auf solche Dinge wie auf die Temperamente so Ihre Aufmerksamkeit lenken, um darnach die Klasse für den Unterricht einzuteilen, müssen Sie vor allen Dingen darauf Rücksicht nehmen, daß der Mensch als solcher ein fortwährend Werdender ist. Und das ist etwas, was wir uns in unserem Erzieherbewußtsein immerwährend aneignen müssen, daß der Mensch ein fortwährend Werdender ist, daß er Metamorphosen unterliegt im Verlaufe seines Lebens. Und ebensogut wie wir stark reflektieren auf die einzelnen Temperamentsanlagen der einzelnen Kinder, können wir reflektieren auf das Werdende, und können sagen: In der Hauptsache sind alle Kinder Sanguiniker, ob sie auch im einzelnen phlegmatisch oder cholerisch sind. Alle Jünglinge und Jungfrauen sind eigentlich Choleriker, und wenn es nicht so ist, wenn es in dieser Zeit nicht da ist, ist es eine ungesunde Entwickelung. Im Mannes- und Frauenalter ist der Mensch Melancholiker. Und im Greisenalter ist er phlegmatisch.

Das beleuchtet wiederum doch ein wenig die Situation in bezug auf die Temperamente, denn Sie sehen da etwas, was ganz besonders notwendig ist, in unserer jetzigen Zeit zu berücksichtigen. Wir lieben in unserer Jetzigen Zeit, uns starre, fest definierte Begriffe zu machen. In Wirklichkeit geht alles ineinander, so daß man in dem Augenblick, wo man gesagt hat, der Mensch bestehe aus Kopf-, Brust- und Gliedmaßenmensch, sich auch klarmachen muß, daß eben alles ineinandergeht. So ist ein cholerisches Kind nur der Hauptsache nach cholerisch, ein sanguinisches nur der Hauptsache nach sanguinisch und so weiter. Gelegenheit, vollcholerisch zu sein, hat man eigentlich erst im Jünglings- und Jungfrauenalter. Manche bleiben ihr ganzes Leben hindurch Jünglinge, weil sie sich das Jünglingsalter ihr ganzes Leben hindurch bewahren. Nero und Napoleon kamen überhaupt nicht über das Jünglingsalter hinaus. Wir ersehen daraus, wie sich Dinge, die eigentlich im Werden miteinander wechseln, doch wieder im Wechsel ineinanderschieben.

Worauf beruht des Dichters, wie überhaupt geistige Produktivität? Worauf beruht es, daß man Dichter werden kann? Darauf, daß man gewisse Eigenschaften des Jünglings- und Kindesalters das ganze Leben hindurch bewahrt. Man hat um so mehr Anlage zur Dichtkunst, je mehr man jung geblieben ist. Es ist in gewissem Sinne ein Unglück für den Menschen, wenn man sich nicht die Möglichkeit bewahrt, gewisse Jugendeigenschaften, ein gewisses Sanguinisches, so für das ganze Leben zu bewahren. Es ist sehr wichtig für den Erzieher, sanguinisch durch Entschluß werden zu können. Das ist außerordentlich wichtig, daß man das als Erzieher berücksichtigt, so daß man diese glückliche Veranlagung des Kindes als etwas ganz Besonderes pflegt.

Alle produktiven Eigenschaften, alles, worauf das Gedeihen des geistig-kulturellen Gliedes des sozialen Organismus beruhen wird, das werden die jugendlichen Eigenschaften des Menschen sein, das wird gemacht werden von Menschen, die Jugendtemperament bewahrt haben.

Alles Wirtschaftliche beruht darauf, daß im Menschen Alterseigenschaften hereinragen, auch wenn wir jung sind. Denn alles wirtschaftliche Urteil beruht auf der Erfahrung. Erfahrung wird nicht besser bewirkt als dadurch, daß in den Menschen gewisse Alterseigenschaften hereinragen, und der Greis ist ja Phlegmatiker. Der Geschäftsmann gedeiht am besten, wenn er in die übrigen Merkmale und Eigenschaften des Menschen ein gewisses Phlegma beigemischt hat, das eigentlich schon ein Greisenhaftes ist. Das ist das Geheimnis sehr vieler Geschäftsleute, daß sie sonst sehr gute Geschäftsleute sind, aber etwas Greisenhaftes beigemischt haben, namentlich in Dispositionen und so weiter. Derjenige, der in der Wirtschaft nur das sanguinische Temperament entwickeln würde, der würde nur zu Jugendprojekten kommen, die nie fertig werden. Der Choleriker, der jünglinghaft geblieben ist, würde sich durch gewisse spätere Maßregeln frühere verderben. Der Melancholiker kann ja sowieso nicht Geschäftsmann werden. Dagegen ist eine harmonische Geschäftsentwickelung mit einer greisenhaften Fähigkeit verbunden, die einen in die Lage versetzt, Erfahrungen aus dem Wirtschaftsleben zu sammeln. Wer Neigung zur Erfahrung hat, der ist stets ein phlegmatischer Greis. Harmonische Temperamente mit Phlegma, das gibt die beste Wirtschaftskonstellation.

Sie sehen, daß man, wenn man die Zukunft der Menschheit bedenkt, solche Dinge beachten, Rücksicht darauf nehmen muß. Man ist als dreißigjähriger Dichter oder Maler nicht nur dreißigjähriger Mensch, sondern es haben sich zugleich kindliche, jugendliche Eigenschaften in den Menschen hereingeschoben. Wenn einer produktiv ist, kann man sehen, wie ein Zweiter in ihm lebt, in dem er mehr oder weniger kindlich geblieben ist, in dem das Kindliche in ihn hereingeschoben ist.

Alle diese angeführten Dinge müssen Gegenstand einer neuartigen Psychologie werden.

Second Seminar Discussion

L. reports on the questions: First, how does the sanguine temperament manifest itself in children, and second, how should it be treated?

Rudolf Steiner: This is where individualization begins. We have said that we can classify according to temperaments. In mass education, children must be taught general drawing, and now we can individualize somewhat within the individual groups. Then it would be a matter of how you wanted to individualize the drawing lessons. Imitation will be cultivated less and less. In drawing, one will try to awaken the inner sense of form. It will only be possible to individualize in this way. A distinction can be made between more linear forms and more dynamic ones, between simpler, clearer forms and those with more detail. More complicated, more detailed forms would be suitable for children with a sanguine temperament. The temperament will determine the way in which one or the other is taught.

E. reports on the same topic.

Rudolf Steiner: Isn't it true that with such things one must always be very clear that the treatment does not have to be unambiguous? Of course, one can do something that is quite good in such a case, and the other can do something else that is also good. So there is no need to strive for pedantic clarity, but certain broad guidelines must be adhered to and thoroughly understood.

The question of whether a sanguine child is difficult or easy to deal with is very important. One should form an opinion on this and, for example, realize the following: It can happen with a sanguine child that one has to bring up or explain something. The child has probably taken in the matter, but after a while one notices that it is no longer paying attention, but has turned to something else. This impairs the child's progress. What would you do if you noticed that you were talking about horses at school, and after a while the sanguine child had drifted far away from the subject and turned their attention to something completely different, so that everything you were discussing could go in one ear and out the other? What would you do with such a child?

Much will depend on how far you can individualize in such a case. If you have many children, many measures will not be easy to implement. If you have many children, you will have the sanguine children together in one group. Then you must set an example for the sanguine children through the melancholic children. If something is wrong in the sanguine group, turn to the melancholic group and let this temperament play out to have a balancing effect! This is particularly important to consider in mass teaching. It is important not only to remain serious and calm yourself, but also to allow the seriousness and calmness of the melancholic children to interact with the sanguine group.

Let's say you are talking about horses. You notice that a sanguine child from the group is no longer paying attention. Now try to acknowledge this. By asking the child a question, you make it clear that the child is no longer paying attention. Then try to state the fact in the melancholic group that while you were talking about the wardrobe earlier and have now been talking about the horse for a long time, one child is still thinking about the wardrobe. State this: “Look, you have long since forgotten about the horse, but your friend has not yet moved on from the wardrobe!”

Such facts have a strong effect. In this way, the children rub off on each other. This self-awareness of the children has a strong effect. The subconscious soul has a strong feeling that social life cannot continue if they do not get along with each other. This unconsciousness in the soul must be used strongly, then even mass education can be an extraordinarily good means of progressing, if the characteristics of the children are worn down by each other. To show the contrast, one must have a really light touch and a sense of humor, so that the children see: one never gets annoyed, one has no grudges, but treats things in such a way that they reveal themselves.

T. talks about the phlegmatic child.

Rudolf Steiner: What would you do if a phlegmatic child does not come out at all and drives you to despair?

U. reports on the treatment of temperaments from a musical point of view and in relation to biblical history.

Phlegmatic: harmonium and piano harmony; choral singing

Sanguine: wind instruments melody rhythm; entire orchestra

Choleric: percussion and drums; solo instruments

Melancholic: string instruments counterpoint (which requires more intellectual work); solo singing

In relation to biblical history:

Gospel of Matthew (diverse)

Gospel of Mark (power)

Gospel of John (spiritual depth)

Rudolf Steiner: Much of this is very true, especially with regard to the instruments and the choice of music lessons. Equally good is the contrast between solo singing for melancholics, the whole orchestra for sanguine types, and choral singing for phlegmatic types. These things are very good, and the evangelists are also very good. But the four arts are less suited to the temperaments because it is possible to have a balancing effect on each temperament precisely through the diversity of the arts. Within the individual arts, the principle is very correct, but I would not distribute the arts themselves. This is correct with regard to music. If, for example, you have a phlegmatic person, you may be able to influence them very well through something that moves them in dance or painting. I would not want to forego what can influence them in the various arts. In the individual arts, it will again be possible to distribute the directions and fields of activity of art among the temperaments. It would not be good to give in too much to the temperaments, when it is necessary to prepare everything in the way that is right for the individual.

O. reports on the phlegmatic temperament and says that the child sits with its mouth open.

Rudolf Steiner: You are mistaken; the phlegmatic child will not sit with its mouth open, but with its mouth closed, but with drooping lips. Sometimes such a remark can hit the nail on the head. It was very good to touch on this. However, this will not usually be the case; the phlegmatic child will not sit with its mouth open, but rather the opposite. This brings us back to the question: How can we behave towards the phlegmatic child when it drives us to despair?

The ideal thing to do would be to ask the child's mother to wake them up at least an hour earlier than they are used to, and during this time that is actually taken away from them — it will not affect them because they usually sleep much longer than necessary — to keep them busy with all kinds of activities. From the time you wake them up until the time they would normally wake up, you keep them occupied; that would be an ideal cure. That way, you would take away a lot of their phlegm. As a rule, you won't be able to do that because the parents won't agree to it, but you could do a lot with it.

You can do the following, which is a substitute but can help a lot: When the group is sitting there—they won't be sitting there with their mouths open—and you walk past, and you walk past often, you could do something like this (Dr. Steiner bangs on the table with a bunch of keys), causing a shock to wake the children up, which will then cause the children to go from having their mouths closed to having their mouths open. At that moment, when you have shocked them, try to keep them busy for five minutes. You have to bring them out of their lethargy through an external stimulus, to shake them up. By acting on the unconscious, you have to combat this irregular connection between the etheric body and the physical body. You will always have to find another means of shocking them and thereby bringing them from their drooping lips to an open mouth; that is, bringing about precisely what they do not like to do. This is how this question should be dealt with when these children drive you to despair. If you continue this with patience and really shake up the phlegmatic group in this way all the time, then you will achieve a lot in this area.

T.: Would it not be possible to have the phlegmatic children come to school an hour earlier?

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, if you could do that and manage to wake the children with a certain noise, that would of course be very good. It would also be good to place the phlegmatic group among those who arrive at school earliest. With phlegmatic children, it is important to capture their attention from a changed state of mind.

The question of nutrition for children of different temperaments is raised.

Rudolf Steiner: One will have to make sure that the main digestion time does not coincide with school time, but smaller meals will not be too important. On the contrary, if the children have had breakfast, they will be able to pay better attention than if they come with an empty stomach. Of course, if they are overfed, which is very likely with phlegmatic children, then it will be impossible to teach them anything. Sanguine children should not be given too much meat, and phlegmatic children should not be given too many eggs. Melancholic children, on the other hand, can be given a well-balanced diet, but not too many root vegetables and cabbage. With melancholic children, nutrition is very individual, so you have to observe them. With sanguine and phlegmatic children, you can generalize. This is followed by comments from D. on the melancholic temperament of children.

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, that was very good. For teaching purposes, however, it should also be taken into account that melancholic children easily fall behind and do not easily keep up. I would ask you to bear this in mind.

A. speaks on the same topic.

Rudolf Steiner: It is very good to note that with melancholic children, it is very much a question of how one relates to them. They also lag behind in the development of the etheric body, which otherwise becomes free with the change of teeth. Therefore, these children are much more receptive to imitation. They hold on to what you show them if they have grown fond of you. You have to take advantage of the fact that they have the principle of imitation for longer.

N. also reports on the melancholic temperament.

Rudolf Steiner: I would ask you to take particular account of the fact that it is very difficult to treat the melancholic temperament if one does not consider something that is almost always present: the melancholic person is in a strange state of self-deception; he believes that the experiences he has only affect himself. The moment you teach them that other people also have these and similar experiences, it is always a kind of cure for them, because they realize that they are not as interesting an individual as they believe themselves to be. They are caught up in the illusion that they are completely unique, just as they are. If you make him realize this strongly: “You are not such an extraordinary person; there are many others who experience this or that,” then this has a very strong effect on the impulses that lead to melancholy. That is why it is good to treat him especially with biographies of great personalities. He will be less interested in the external world and more interested in individual personalities. These biographies should be used especially to help him overcome his melancholy.

Two teachers report on the choleric temperament. Rudolf Steiner draws the following figures on the blackboard:

What is this? This is also a characterization of the four temperaments. Melancholic children are usually slim and thin; sanguine children are the most normal; those with more prominent shoulders are phlegmatic children; those with a stocky build, so that their head almost sinks into their body, are choleric children.

Michelangelo and Beethoven had a mixture of melancholic and choleric temperaments.

Now, please bear in mind that when it comes to children's temperaments, we as teachers are by no means called upon to regard the temperaments in question as “faults” from the outset and to try to combat them. We must recognize the temperament and ask ourselves the question: How should we treat it in order to achieve a desirable goal in life, so that the temperament becomes the very best and the children achieve their goal in life with the help of their temperament? In the case of the choleric temperament in particular, it would be of very little help if we tried to drive it out and replace it with something else. In fact, the life and passion of the choleric person has achieved a great deal, and in world history in particular, many things would have been different if it had not been for the choleric person. But especially in the case of children, we must ensure that they achieve appropriate life goals despite their temperament.

With choleric children, it is important to take into account fictional situations, artificially created situations that are brought to the child's attention. For example, when a child is raging, one should direct their attention to fictional situations and treat these fictional situations in a choleric manner, so that I tell the young choleric child, for example, about a wild guy I met, which I present to them as reality. Then I would become ecstatic, describing how I treat him, how I judge him, so that he sees the choleric temperament in others, in sophisticated people, so that he sees the deed. This will gather strength within him so that he can also understand other things well.

Rudolf Steiner is asked to recount the scene between Napoleon and his secretary.

Rudolf Steiner: First you would have to ask the building commission for permission! — The speaker would have to treat the scene described in the speech in such a way that choleric behavior comes out. This will always gather strength in the choleric child, so that it can then be dealt with further. An ideal would be to paint a situation for the choleric group in order to gather strength in this way. Then it will always last a few days. The children will then not be hindered at all in taking things in for a few days. Otherwise, they will rage inwardly against things they should understand.

Now I would like you to try the following: Something should remain of this treatment of temperaments, and I would ask Miss B. to give a summary of the peculiarities of temperaments and their treatment on a maximum of six pages, based on everything I have discussed here. It does not have to be tomorrow.

On the other hand, I would like to ask Ms. E. to form a mental image of having two groups in front of her: sanguine children and melancholic children, and she should alternate between a kind of drawing lesson with simple drawing motifs so that one time it would serve the sanguine children and the other time the melancholic children.

Now I would also like to ask Mr. T. to do the same thing with drawing for phlegmatic and choleric children, so that you can demonstrate this to us tomorrow, as you have arranged it.

Then I would perhaps ask Miss A., Miss D., and Mr. R. to tackle the following tasks: Imagine that you are to tell the same fairy tale twice in a row, but not in exactly the same way, rather using different sentences and so on. The first time, pay more attention to sanguine children, the second time to melancholic children, so that both groups benefit.

Then I would ask Mr. M. and Mr. L. to tackle the difficult task of giving an individual description of an animal or animal species, tailoring it once for choleric children and once for phlegmatic children.

Mr. O., Mr. N., and perhaps Mr. U. will also help. I would ask them to solve the task of how to take the four temperaments into account in arithmetic, and only in arithmetic.

Isn't it true that when you focus your attention on things like temperaments in order to divide the class for teaching, you must above all take into account that human beings as such are constantly evolving. And that is something we must constantly remind ourselves of in our awareness as educators, that human beings are constantly developing, that they undergo metamorphoses in the course of their lives. And just as we reflect deeply on the individual temperamental dispositions of individual children, we can reflect on what is developing and say: Essentially, all children are sanguine, even if they are phlegmatic or choleric in individual cases. All young men and women are actually choleric, and if this is not the case, if it is not present at this time, it is an unhealthy development. In adulthood, human beings are melancholic. And in old age, they are phlegmatic.

This sheds a little light on the situation with regard to temperaments, because you see something there that is particularly important to consider in our present time. In our present time, we love to form rigid, firmly defined concepts. In reality, everything is intertwined, so that the moment you say that human beings consist of head, chest, and limb, you must also realize that everything is intertwined. Thus, a choleric child is only choleric in the main, a sanguine child is only sanguine in the main, and so on. The opportunity to be fully choleric actually only arises in adolescence. Some people remain adolescents throughout their lives because they preserve their adolescence throughout their lives. Nero and Napoleon never grew out of adolescence. We can see from this how things that are actually in the process of becoming change with each other, yet merge into each other again in the process of change.

What is the basis of the poet's, and indeed all intellectual, productivity? What is the basis for becoming a poet? It is the preservation of certain characteristics of youth and childhood throughout one's life. The more one remains young, the more one is predisposed to poetry. In a certain sense, it is unfortunate for a person if they do not preserve the possibility of retaining certain youthful qualities, a certain sanguine nature, for their entire life. It is very important for educators to be able to become sanguine through determination. It is extremely important that educators take this into account, so that they nurture this happy disposition in children as something very special.

All productive qualities, everything on which the flourishing of the intellectual and cultural limb of the social organism will be based, will be the youthful qualities of human beings, which will be created by people who have retained their youthful temperament.

Everything economic is based on the fact that age-related qualities emerge in human beings, even when we are young. For all economic judgment is based on experience. Experience is best gained when certain characteristics of old age come to the fore in people, and the old man is, after all, phlegmatic. The businessman thrives best when he has mixed a certain phlegmatic quality into the other characteristics and qualities of man, which is actually already an old man's quality. This is the secret of many businesspeople: they are otherwise very good businesspeople, but they have added something elderly, particularly in their dispositions and so on. Those who only develop a sanguine temperament in business will only end up with youthful projects that are never completed. The choleric person who has remained youthful will ruin earlier projects through certain later measures. The melancholic cannot become a businessman anyway. On the other hand, harmonious business development is linked to an aged ability that enables one to gain experience from economic life. Those who have a penchant for experience are always phlegmatic old men. Harmonious temperaments with phlegm provide the best economic constellation.

You see that when considering the future of humanity, one must take such things into account and give them due consideration. A thirty-year-old poet or painter is not only a thirty-year-old human being, but at the same time childlike, youthful qualities have crept into the person. When someone is productive, you can see how a second person lives within them, in whom they have remained more or less childlike, in whom the childlike has crept in.

All these things mentioned must become the subject of a new kind of psychology.