Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

3 September 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Twelve

Speech Exercises:

Curtsey cressets Betsy jets cleric

lastly plotless light skeptic

RUDOLF STEINER: You will only get the words right when you can reel them off by heart. Be conscious of every syllable you speak!

Narrow wren

mirror royal

gearing grizzled

noting nippers

fender coughing

Some of the teachers, as requested, gave a comprehensive survey of the natural history of plants as discussed in yesterday’s discussion.

RUDOLF STEINER: Give as many examples as possible! Ideas about metamorphosis and germination cannot really be understood by children under the age of fourteen, and certainly not by children of nine to eleven. Related to this is something else of great importance that needs to be said. You must have followed the recent discussions from every side about so-called “sex education” for children. Every possible perspective, for and against, has been presented.

The subject essentially breaks down into three questions. First, we consider who should present such sex education. Those who think seriously about their great responsibility as teachers in the school soon realize the extraordinary difficulty of such an undertaking. I doubt if any of you would really welcome the job of providing sex education to young teenagers between twelve and fourteen. The second question concerns how this teaching should be given. This is not an easy question either. The third question is about its place in education. Where should you introduce it? In natural history lessons perhaps?

If teaching were based on true educational principles this task would fall very naturally into place. If in your teaching you explain the process of growth to the children in relation to light, air, water, earth, and so on, the children will absorb such ideas so that you can proceed gradually to the process of fertilization in plants, and then in animals and human beings. But you must look comprehensively at this matter and show how plants come into existence through light, water, earth, and so on; in short, for the complicated process of growth and fertilization you must prepare ideas that will provide children with a foundation in imaginative thinking. The fact that there has been so much chatter about sex education proves that there is something wrong with teaching methods of today; it should certainly be possible in the early school years to prepare for later sex education. For instance, by explaining the process of growth in connection with light, air, water, and so on, the teacher could foster the pure and chaste views necessary for sex education later on.

In map drawing you should color the mountains brown and rivers blue. Rivers should always be drawn as they flow, from source to mouth, never from mouth to source. Make one map for the soil and ground nature—coal, iron, gold, or silver, and draw another map for towns, industries, and so on. I ask you to note the importance of choosing some particular part of the world as a subject for your lessons, and then as you continue, you should refer back to this area again and again. The way that your subject is presented is also very important; try to live directly into your subject so that the children always get the feeling that you are describing something in which you are actually involved. When you describe an industry they should feel that you are working there, and the same is true when you describe a mine, and so on. Make it as lively as possible! The more life there is in your descriptions, the better the children will work with you.

Someone calculated the measurement of areas, beginning with the square and proceeding to the rectangle, parallelogram, trapezium, and triangle.

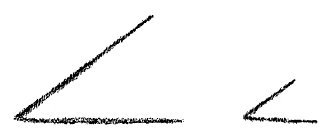

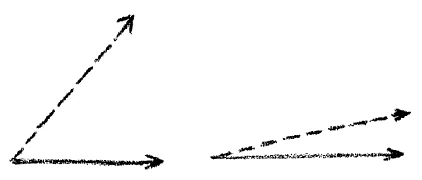

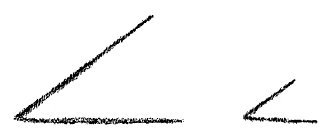

RUDOLF STEINER: It is difficult to explain to a child what an angle actually is. Can you make up a method for doing this? Perhaps you remember how difficult it was for you to be clear about it—aside from the fact that there may be some of you who do not yet know what an angle really is.

You can explain to the children what a larger or smaller angle is by drawing angles, first with longer arms and then with shorter arms. Now which angle is the larger? They are exactly the same size!

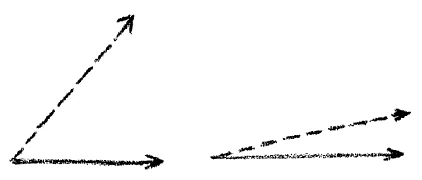

Then have two of the children walk from a certain point simultaneously, two times, and show them that the first time they walked they made a larger angle, and the second time a smaller one. When they walked making the smaller angle their paths were closer together, with the larger angle further apart. This can also be shown with an elbow movement.

It’s good to arrive at a view of larger and smaller angles before beginning to measure angles in degrees.

The transformation of a parallelogram into a square was spoken about, to show that the area, in both cases, is base multiplied by height.

RUDOLF STEINER: Yes, it can be done like that. But if by tomorrow you would consider the whole subject on a somewhat different basis, perhaps you will find it beneficial to introduce the children to a clear concept of area as such first, and then the size of the area. The children know the shape of a square, and now you want to show it to them as a surface that could be larger or smaller.

Second, figure out for tomorrow how you would give the children arithmetical problems to solve without writing down any figures—in other words, what we could call mental arithmetic. You could, for example, give the children this problem to do: A messenger starts from a certain place and walks so many miles per hour; another messenger begins much later; the second messenger does not walk but rides a bicycle at a certain number of miles per hour. When did the cyclist pass the messenger on foot?

The object of these problems is to develop in children a certain presence of mind in comprehending a situation and evaluating it as a whole.

Zwölfte Seminarbesprechung

Sprechübungen:

Ketzerkrächzer petzten jetzt kläglich

Letztlich plötzlich leicht skeptisch

Rudolf Steiner: Erst dann sind die Dinge richtig, wenn man sie auswendig herschnurren kann. Bewußt jede Silbe sprechen!

Nur renn nimmer reuig

Gierig grinsend

Knoten knipsend

Pfänder knüpfend

Aus «Wir fanden einen Pfad» von Christian Morgenstern:

Wer vom Ziel nicht weiß,

Kann den Weg nicht haben,

Wird im selben Kreis

All sein Leben traben;

Kommt am Endehin,

Wo er hergerückt,

Hat der Menge Sinn

Nur noch mehr zerstückt.Wer vom Ziel nichts kennt,

Kann’s doch heut erfahren;

Wenn es ihn nur brennt

Nach dem Göttlich-Wahren;

Wenn in Eitelkeit

Er nicht ganz versunken

Und vom Wein der Zeit

Nicht bis oben trunken.

Rudolf Steiner: Die Nuancen, in denen die Strophen gelesen werden müssen, werden wir erst morgen nach Vorlesung der dritten Strophe ersehen können.

Einige Kursteilnehmer geben die als Aufgabe gestellte zusammenfassende Darstellung der bisher besprochenen Pflanzengeschichte.

Rudolf Steiner: Möglichst viele Beispiele geben! - Der Metamorphosegedanke und der Gedanke des Keimens ist für die Kinder unter vierzehn Jahren, besonders für Kinder von neun bis elf Jahren noch nicht verständlich.

Da ist noch etwas zu bemerken, was sehr wichtig ist. Sie haben ganz gewiß verfolgt, daß in der neueren Zeit von allen Seiten her die Frage erörtert worden ist über die sogenannte sexuelle Aufklärung der Kinder. Nun ist ja dabei alles mögliche pro und kontra angegeben worden. In der Hauptsache ergeben sich drei Fragen.

Es ist in Betracht zu ziehen: Wer soll die sexuelle Aufklärung geben? Wer sich im Ernst mit aller Verantwortung des Erziehers in die Schule hineindenkt, der wird bald merken, daß es außerordentlich schwer ist, diese Aufgabe zu übernehmen. Ich glaube, Sie würden alle nicht gern zwölf- bis vierzehnjährigen Rangen und Ranginnen sexuelle Aufklärung geben.

Zweitens handelt es sich darum: Wie soll man die Aufklärung geben? Auch das ist nicht so ganz leicht, wie man zu Werke gehen soll.

Drittens handelt es sich darum: Wo soll man sie geben? Wo soll man sie anbringen? Beim naturwissenschaftlichen Unterricht und so weiter?

Wenn man den Unterricht nach richtigen pädagogisch-didaktischen Grundsätzen erteilen würde, so würde die Sache sich ganz von selbst ergeben. Wenn Sie so vorgehen, daß Sie den Kindern den Wachstumsvorgang in Zusammenhang mit Licht, Luft, Wasser, Erde und so weiter erklären, dann nimmt das Kind solche Begriffe auf, daß Sie langsam bei den Pflanzen übergehen können zum Befruchtungsvorgang, und dann bei den Tieren und beim Menschen. Aber Sie müßten im großen die Sache betrachten, die Pflanzen entstehen lassen an Licht, Wasser, Erde, kurz, jene Vorstellungen vorbereiten, die überhaupt den komplizierten Wachstums- und Befruchtungsvorgang vorstellungsgemäß beim Kinde veranlagen. Daß so viel geschwätzt wurde über die sexuelle Aufklärung, ist ein Beweis dafür, daß die Methoden des Unterrichtes heute nicht in Ordnung sind, sonst würde man die Elemente schon ganz früh geschaffen haben aus solchen keuschen, reinen Vorstellungen heraus wie den Erklärungen des Wachstumsvorganges im Zusammenhang mit Licht, Luft, Wasser und so weiter.

M. macht geographische Ausführungen über Gegenden am mittleren und unteren Rhein.

Rudolf Steiner: Beim Kartenzeichnen sollte man die Gebirge braun, die Flüsse blau zeichnen. Den Fluß sollte man immer seinem Lauf gemäß vom Ursprung an zeichnen, nie von der Mündung aus. Eine Karte für die Bodenverhältnisse und die Naturgrundlage, Kohle, Eisen, Gold, Silber; dann eine zweite für die Städte, die Industrie und so weiter.

Ich mache darauf aufmerksam, daß es wichtig ist, eine Auswahl zu treffen und so zu gliedern, daß man öfter einmal zurückkommt auf dieses Gebiet. Auch ist die Art des Vortrages da recht wichtig. Versuchen Sie, sich recht in den Stoff hineinzulegen, so daß das Kind immer das Gefühl hat, man schildert, sich absolut hineinlebend, wenn man Industrie schildert, immer so, als wenn man selber dort arbeitete. Beim Bergbau wieder so und so weiter. Möglichst lebendig! Je lebendiger man schildert, um so mehr arbeiten die Kinder da mit.

T. entwickelt die Flächenberechnung, ausgehend vom Quadrat und übergehend zum Rechteck, Parallelogramm, Trapez, Dreieck.

Rudolf Steiner: Es ist schwierig, dem Kinde beizubringen, was ein Winkel wirklich ist. Könnten Sie eine Methode bringen, um dem Kinde das zu zeigen? Vielleicht erinnern Sie sich, wie schwer es Ihnen geworden ist, das zu unterscheiden, ganz abgesehen davon, daß es Herrschaften hier geben könnte, die noch nicht wissen, was ein Winkel wirklich ist.

Auf diese Weise werden Sie dem Kinde beibringen, was ein großer und ein kleiner Winkel ist, indem Sie zuerst Winkel zeichnen, wobei Sie die Schenkel einmal groß, einmal klein machen. Welcher Winkel ist größer? — Sie sind beide gleich groß!

Dann lassen Sie zwei Kinder zweimal gleichzeitig von demselben Punkte aus laufen und machen ihnen klar, daß sie das erste Mal unter einem großen, das zweite Mal unter einem kleinen Winkel gelaufen sind. Wenn sie unter einem kleinen Winkel gelaufen sind, so sind ihre Wege näher beieinander; wenn unter einem großen, sind sie weiter auseinander. Auch beim Ellbogen läßt sich das zeigen.

Es ist gut, daß schon vorher eine Vorstellung vom großen und kleinen Winkel da ist, ehe man beginnt, durch den Kreis den Winkel zu messen.

T. spricht weiter über die Verwandlung eines Parallelogramms in ein Rechteck, um klarzumachen, daß die Fläche gleich Grundlinie mal Höhe ist.

Rudolf Steiner: Man kann schon so vorgehen. Aber wenn Sie die ganze Überlegung bis morgen noch einmal auf einen etwas anderen Boden bringen, so würde sich vielleicht doch empfehlen, darüber nachzudenken, ob man nicht den Begriff der Fläche als solcher und den der Größe der Fläche dem Kinde auf irgendeine Weise rationell beibringen könnte. Das Kind kennt die Figur des Quadrates, und Sie wollen jetzt dem Kinde beibringen, daß das eine Fläche ist und daß die Fläche gröRer und kleiner sein könnte.

Zweitens: Denken Sie bis morgen nach, wie Sie den Kindern Aufgaben stellen würden, wo sie das Rechnen, ohne Zahlen zu schreiben, ausführen könnten, was man sonst immer Kopfrechnen genannt hat.

Denken Sie einmal, Sie würden dem Kinde die Aufgabe stellen: Von irgendwo geht ein Bote ab, der macht so und so viele Meilen, und weit hinterher geht ein anderer Bote ab, der geht nicht, sondern der fährt mit dem Fahrrad, der macht so und so viele Meilen. Wann hat der Bote mit dem Fahrrad den gehenden Boten eingeholt? Dieses ist so zu behandeln, daß die Kinder eine gewisse Geistesgegenwart entwickeln im Ergreifen von Situationen und im Überblicken von Situationen.

Twelfth Seminar Discussion

Speech exercises:

Heretics now croaked pitifully

Ultimately suddenly slightly skeptical

Rudolf Steiner: Only then are things right when you can recite them by heart. Speak every syllable consciously!

Just don't ever run remorsefully

Grinning greedily

Cutting knots

Tying pledges

From “We Found a Path” by Christian Morgenstern:

Those who do not know their destination,

Cannot find the way,

Will trot in the same circle

All their lives;

Will end up,

Where they started,

Having fragmented the meaning

Even more.Those who know nothing of the goal

Can still learn it today;

If only they burn

For the divine truth;

If he is not completely immersed in vanity

And not drunk to the top

With the wine of time.

Rudolf Steiner: We will only be able to see the nuances in which the verses must be read tomorrow, after reading the third verse.

Some course participants give the summary presentation of the plant history discussed so far, which was set as an assignment.

Rudolf Steiner: Give as many examples as possible! - The idea of metamorphosis and the idea of germination are not yet understandable for children under the age of fourteen, especially for children between the ages of nine and eleven.

There is something else to note that is very important. You have certainly noticed that in recent times the question of so-called sex education for children has been discussed from all sides. Now, all kinds of pros and cons have been put forward. Three main questions arise.

It must be considered: Who should provide sex education? Anyone who seriously considers the full responsibility of the educator in school will soon realize that it is extremely difficult to take on this task. I believe that none of you would like to provide sex education to twelve- to fourteen-year-old boys and girls.

Secondly, there is the question of how to provide sex education. It is not entirely easy to know how to go about this.

Thirdly, where should it be provided? Where should it be incorporated? In science lessons and so on?

If lessons were taught according to correct pedagogical and didactic principles, the matter would resolve itself. If you proceed by explaining to the children the growth process in connection with light, air, water, soil, and so on, then the child will absorb such concepts that you can slowly move on to the fertilization process in plants, and then in animals and humans. But you would have to look at the big picture, letting plants grow with light, water, earth, in short, preparing those mental images that predispose the child to imagine the complicated process of growth and fertilization. The fact that there has been so much talk about sex education is proof that today's teaching methods are not adequate, otherwise the elements would have been created at a very early age from chaste, pure mental images such as explanations of the growth process in connection with light, air, water, and so on.

M. gives geographical explanations about areas on the middle and lower Rhine.

Rudolf Steiner: When drawing maps, mountains should be drawn in brown and rivers in blue. Rivers should always be drawn according to their course from their source, never from their mouth. One map for soil conditions and natural resources, coal, iron, gold, silver; then a second for cities, industry, and so on.

I would like to point out that it is important to make a selection and structure it in such a way that you can return to this area more often. The style of the lecture is also quite important. Try to immerse yourself in the material so that the child always has the feeling that you are describing it with absolute empathy, as if you yourself were working there when you describe industry. The same applies to mining, and so on. As vividly as possible! The more vividly you describe it, the more the children will engage with it.

T. develops area calculation, starting with the square and moving on to the rectangle, parallelogram, trapezoid, and triangle.

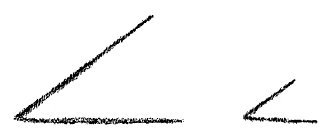

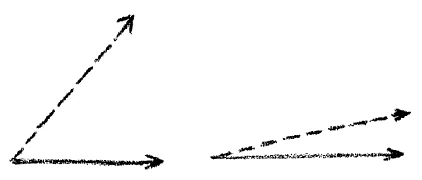

Rudolf Steiner: It is difficult to teach children what an angle really is. Could you suggest a method for showing this to children? Perhaps you remember how difficult it was for you to distinguish between them, not to mention the fact that there may be people here who do not yet know what an angle really is.

In this way, you will teach the child what a large and a small angle is by first drawing angles, making the sides large in one case and small in the other. Which angle is larger? — They are both the same size!

Then let two children run twice at the same time from the same point and make it clear to them that the first time they ran under a large angle and the second time under a small angle. If they ran under a small angle, their paths are closer together; if under a large angle, they are further apart. This can also be demonstrated with the elbow.

It is good that there is already a mental image of the large and small angle before one begins to measure the angle through the circle.

T. continues to talk about the transformation of a parallelogram into a rectangle to make it clear that the area is equal to the base times the height.

Rudolf Steiner: You can proceed in this way. But if you reconsider the whole idea tomorrow from a slightly different perspective, it might be advisable to think about whether the concept of area as such and the size of the area could be taught to the child in some rational way. The child is familiar with the shape of a square, and you now want to teach the child that this is an area and that the area could be larger or smaller.

Secondly: Think about how you would set the children tasks where they could perform calculations without writing numbers, what has always been called mental arithmetic.

Imagine you set the child the following task: A messenger sets off from somewhere and travels a certain number of miles, and far behind him another messenger sets off, not on foot but by bicycle, and travels a certain number of miles. When did the messenger on the bicycle catch up with the messenger on foot? This should be treated in such a way that the children develop a certain presence of mind in grasping situations and in surveying situations.