Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

2 September 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Eleven

RUDOLF STEINER: In the speech exercises that we will take now, the principal purpose is to make the speech organs more flexible.

Curtsey Betsy jets cleric

lastly light sceptic

One should acquire the habit of letting the tongue say it on its own, so to speak.

Tu-whit twinkle ‘twas

twice twigged tweaker

to twenty twangy twirlings

the zinnia crisper

zither zooming shambles

this smartened smacking

smuggler sneezing

snoring snatching.

Both these exercises are really perfect only when they are said from memory.

From “We Found a Path” (by Christian Morgenstern):

Those who don’t know the goal

can’t find the way,

they will trot the same circle

all their lives long,

and return in the end

whence they began,

their piece of mind

more disturbed than before.

RUDOLF STEINER: Now we will proceed to the task that we have been gnawing at for so long.

Someone presented a list of the human soul moods and the soul moods of plants that could be said to correspond to them.

RUDOLF STEINER: All these things that have been presented are reminiscent of when phrenology was in vogue, when people classified human soul qualities according to their fantasies, and then searched the head for all kinds of bumps that were then associated with these qualities. But things are not like that, although the human head can certainly be said to express human soul nature. It is true that if a person has a very prominent forehead, it may indicate a philosopher. If a person has a very receding forehead and is at the same time talented, such a person may become an artist. You cannot say that the artist is located in a particular part of the head, but through your feelings you can differentiate between one or another form. You should consider the soul in this way. The more intellectual element drives into the forehead, and the more artistic element allows the forehead to recede. The same thing is also true in the study of plants. I mean your research should not be so external, but rather you should enter more deeply into the inner nature of plants and describe conditions as they actually are.

Some remarks were added.

RUDOLF STEINER: When you confine yourself too much to the senses, your viewpoint will not be quite correct. The senses come into consideration insofar as each sense contributes to the inner life of human beings, whatever can be perceived by a particular sense. For example, we owe several soul experiences to the sense of sight. We owe different soul experiences to other senses. Thus we can retrace our soul experiences to these various senses. In this way the senses are associated with our soul nature. But we should not assert unconditionally that plants express the senses of the Earth, because that is not true.

Someone cited samples from the writings of Emil Schlegel, a homeopathic doctor from Tübingen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Schlegel’s comparisons are also too external. He returns to what can be found in the mystics—Jacob Boehme and others—to the so-called “signatures.” Mystics in the Middle Ages were aware of certain relationships to the soul world that led them into deeper aspects of medicine. You find, for example, that a definite group of plants is associated with a quality of soul; mushrooms and fungi are associated with the quality that enables a person to reflect, to ponder something, the kind of inner life that lies so deeply in the soul that it does not demand much of the outer world for its experience, but “pumps,” as it were, everything out of itself. You will also find that this soul quality, most characteristic of mushrooms, is very intimately associated with illnesses of a headache nature; in this way you discover the connection between mushrooms and illnesses that cause headaches. Please note that you cannot make such comparisons when teaching about animals.

There are, as yet, no proper classifications of plants, but by means of these relationships between human soul qualities and groups of plants you must try to bring some kind of classification into the life of plants. We will now attempt to classify the plant kingdom.

You must first distinguish what are properly seen as the different parts of the plant—that is, root, stem (which may develop into a trunk), leaves, blossoms, and fruits. All the plants in the world can be divided into groups or families. In one family the root is more developed; the rest of the plant is stunted. In another the leaves are more developed, and in others the blossoms; indeed, these last are almost entirely blossom. Such things must be considered in relation to each other. Thus we can classify plants by seeing which system of organs predominates, root, trunk, leaves, and so on, since this is one way that plants vary. Now, when you recognize that everything with the nature of a blossom belongs to a certain soul quality, you must also assign other organic parts of the plant to other soul qualities. Thus, whether you associate single parts of the plant with qualities of soul or think of the whole plant kingdom together in this sense, it is the same thing. The whole plant kingdom is really a single plant.

Now what are the actual facts about the sleeping and waking of the Earth? At the present time [September] the Earth is asleep for us, but it is awake on the opposite side of the Earth. The Earth carries sleep from one side to the other. The plant world, of course, takes part in this change, and in this way you get another classification according to the spatial distribution of sleeping and waking on the earth—that is, according to summer and winter. Our vegetation is not the same as that on the opposite side of the Earth.

For plant life, everything is related with the leaves, for every part of a plant is a transformed leaf.

Someone compared groups of plants with temperaments.

RUDOLF STEINER: No, you are on the wrong track when you relate the plant world directly to the temperaments.

We might say to the children, “Look children, you were not always as big as you are now.1According to the Waldorf curriculum, the children are around eleven years old when they are taught about the plant kingdom. You have learned to do a great many things that you couldn’t do before. When your life began you were small and awkward, and you couldn’t take care of yourselves. When you were very small you couldn’t even talk. You could not walk either. There were many things you could not do that you can do now. Let’s all think back and remember the qualities you had when you were very young children. Can you remember what you were like then and what kinds of things you did? Can you remember this?” Continue to ask until they all see what you mean and say “No.” “So none of you know anything about what you did when you were toddlers?

“Yes, dear children, and isn’t there something else that happens in your lives that you can’t remember, and things that you do that you can’t remember afterward?” The children think it over. Perhaps someone among them will find the answer, otherwise you must help them with it. One of them might answer, “While I was asleep.” “Yes, the very same thing happens when you are very young that happens when you go to bed and sleep. You are ‘asleep’ when you are a tiny baby, and you are asleep when you are in bed.

“Now we will go out into nature and look for something there that is asleep just like you were when you were very young. Naturally you could not think of this yourselves, but there are those who know, and they can tell you that all the fungi and mushrooms that you find in the woods are fast asleep, just as you were when you were babies. Fungi and mushrooms are the sleeping souls of childhood.

“Then came the time when you learned to walk and to speak. You know from watching your little brothers and sisters that little children first have to learn to speak and walk, or you can say walk and then speak. That was something new for you, and you could not do that when you began your life; you learned something fresh, and you could do many more things after you learned to walk and speak.

“Now we will go out into nature again and search for something that can do more than mushrooms and fungi. These are the algae,” and I now show the children some examples of algae, “and the mosses,” and I show them some mosses. “There is something in algae and mosses that can do much more than what is in the fungi.”

Then I show the children a fern and say, “Look, the fern can do even more than the mosses. The fern can do so much that you have to say it looks as if it already had leaves. There is something of the nature of a leaf.

“Now you do not remember what you did when you learned to speak and walk. You were still half asleep then. But if you watch your brothers and sisters or other little children you know that, when they grow a little older, they do not sleep as long as when they were first born. Then came the time when your mind woke up, and you can return to that time as your earliest memory. Just think! That time in your mind compares with the ferns. But ever since then you can remember more and more of what happened in your mind. Now let’s get a clear picture of how you came to say ‘I.’ That was about the time to which your memory is able to return. But the I came gradually. At first you always said ‘Jack wants.. .’ when you meant yourself.”

Now have a child speak about a memory from childhood. Then you say to the child, “You see, when you were little it was really as though everything in your mind was asleep; it was really night then, but now your mind is awake. It is much more awake now, otherwise you would be no wiser than you used to be. But you are still partly asleep; not everything in you is awake yet; much is still sleeping. Only a part of you has awakened. What went on in your mind when you were four or five years old was something like the plants I am going to show you now.”

We should now show the children some plants from the family of the gymnospernms—that is, conifers, which are more perfectly formed than the ferns—and then you will say to the children, “A little later in your life, when you were six or seven years old, you were able to go to school, and all the joys that school brought blossomed in your heart.” When you show a plant from the family of the ferns, the gymnosperms, you go on to explain, “You see there are still no flowers. That was how your mind was before you came to school.

“Then, when you came to school, something entered your mind that could be compared to a flowering plant. But you had only learned a little when you were eight or nine years old. Now you are very smart; you are already eleven years old and have learned a great many things.

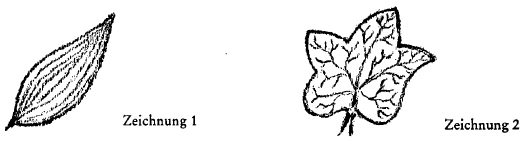

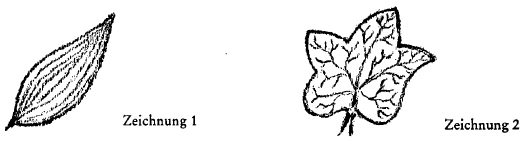

“Now look; here is a plant that has leaves with simple parallel veins

and here is another with more complicated leaves with a network of veins. When you look at the blossoms that belong to the simple leaves, they are not the same as those on the plants with the other kind of leaf, where the blossoms and everything else are more complicated than in those with the simpler leaves.”

Now you show the children, for example, an autumn crocus, a monocotyledon; in these plants everything is simple, and you can compare them to children between seven and nine. Then you can continue by showing the children plants with simple blossoms, ones that do not yet have real petals. You can then say, “You have plants here in which the green sepals and the colored petals are indistinguishable, in which the little leaves under the blossom cannot be distinguished from those above. This is you! This is what you are like now.

“But soon you will be even older, and when you are twelve, thirteen, or fourteen you will be able to compare yourselves with plants that have calyx and corolla; your mind will grow so much that you’ll be able to distinguish between the green leaves we call the calyx and the colored leaves called petals. But first you must reach that stage!” And so you can divide the plants into those with a simple perianth—compared to the elevenyear- old children—and plants with a double perianth—those of thirteen to fourteen years.2The perianth is the envelope of a flower, particularly one in which the calyx and corolla are combined so that they are indistinguishable from one another; these include such flowers as tulips, orchids, and so on. The perianth is single when it has one verticil, and double when it has both calyx and corolla. “So children, this is another stage you have to reach.”

Now you can show the children two or three examples of mosses, ferns, gymnosperms, monocotyledons, and dicotyledons, and it would be a fine thing at this point to awaken their memory of earlier years. Have one of them speak of something remembered about little four-year-old Billy, and then show your ferns; have another child recall a memory of seven-year-old Fred, and then show the corresponding plant for that age; and yet another one could tell a story about eleven-year-old Ernie, and here you must show the other kind of plant. You must awaken the faculty of recalling the various qualities of a growing child and then carry over to the plant world these thoughts about the whole development of the growing soul. Make use of what I said yesterday about a tree, and in this way you will get a parallel between soul qualities and the corresponding plants.

There is an underlying principle here. You will not find parallels accidentally according to whatever plants you happen to pick. There is principle and form in this method, which is necessary. You can cover the whole plant kingdom in this way, with the exception of what happens in the plant when the blossom produces fruit. You point out to the child that the higher plants produce fruits from their blossoms. “This, dear children, can only be compared to what happens in your own soul life after you leave school.” Everything in the growth of the plant, up to the blossom, can be compared only with what happens in the child until puberty. The process of fertilization must be omitted for children. You cannot include it.

Then I continue, “You see, dear children, when you were very small you really only had something like a sleeping soul within you.” In some way remind the children, “Now try to remember, what was your main pleasure when you were a little child? You have forgotten now because, in a way, you were really asleep at that time, but you can see it in little Anne or Mary, in your little baby sister. What is her greatest joy? Certainly her milk bottle! A tiny child’s greatest joy is the milk bottle. And then came the time when your brothers and sisters were a little older, and the bottle was no longer their only joy, but instead they loved to be allowed to play. Now remember, first I showed you fungi, algae, mosses; almost everything they have, they get from the soil. We must go into the woods if we want to get to know them. They grow where it is damp and shady, they do not venture out into the sunlight. That’s what you were like before you ‘ventured out’ to play; you were content with sucking milk from a bottle. In the rest of the plant world you find leaves and flowers that develop when the plants no longer have only what they get from the soil and from the shady woods, but instead come out into the sun, to the air and light. These are the qualities of soul that thrive in light and air.” In this way you show the child the difference between what lives under the Earth’s surface on the one hand (as mushrooms and roots do, which need the watery element, soil, and shade), and on the other hand, what needs air and light (as blossoms and leaves do). “That is why plants that bear flowers and leaves (because they love air and light) are the so-called higher plants, just as you, when you are five or six years old, have reached a higher stage than when you were a baby.”

By directing the children’s thoughts more and more—at one time toward qualities of mind and soul that develop in childhood, and then toward the plants—you will be able to classify them all, based on this comparison. You can put it this way:

Pleasures of infancy (babies): Mushrooms and Fungi

Pleasures of early childhood (the awakening life of feeling, both sorrows and joys): Algae, Mosses

Experiences at the awakening of consciousness of self: Ferns

Experiences of fifth and sixth year, up to school age: Gymnosperms, Conifers

First school experiences, seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth and eleventh year: Parallel-veined plants, Monocotyledons; Plants with simple perianth

Experiences of the eleven-year-old: Simple dicotyledons

School experiences from twelfth to fifteenth year: Net-veined plants, Dicotyledons; Plants with green calyx and colored petals

“You are not smart enough yet for these last experiences (the plants with a green calyx and colored blossoms), and you won’t know anything about them until you are thirteen or fourteen years old.

“Just think; how lovely! One day you will have such rich thoughts and feelings, you will be like the rose with colored petals and green sepals. This will all come later, and you can look forward to it with great pleasure. It is lovely to be able to rejoice over what is coming in the future.” The important thing is that you arouse within children’s hearts a joyful anticipation of what the future will bring them.

Thus, all the successive soul qualities before puberty can be compared with the plant kingdom. After that the comparison goes no further because at this point the children develop the astral body, which plants do not possess. But when the plant forces itself into fertilization beyond its nature, it can be compared with soul qualities of the sixteenth to seventeenth year. There is no need to call attention to the process of fertilization, but you should speak of the process of growth, because that agrees with reality. The children would not understand the process of fertilization, but they would understand the process of growth, because it can be compared with the process of growth in the mind and soul. Just as a child’s soul is different at various ages, so also the plants are different because they progress from the mushroom to the buttercup, which is usually included among the most highly developed plants, the Ranunculuses. It is indeed true that, when the golden buttercups appear during spring in lush meadows, we are reminded of the soul life and soul mood of fourteen-and fifteen-year-old boys and girls.

If at some time a botanist should go to work along these lines in a thoroughly systematic way, a plant system would be found that corresponds to fact, but you can actually show the children the whole external plant world as a picture of a developing child’s soul. Much can be done in this way. You should not differentiate in the individualized way practised by the old phrenologists, but you should have one clear viewpoint that can be carried right through your teaching. Then you will find that it is not quite correct to merely take everything with a root nature and relate it to thought. Spirit in the head is still asleep in a child. Thus, thinking in general should not be related to what has root nature, but a child’s way of thinking, which is still asleep. In the mushroom, therefore, as well as in the child, you get a picture of childlike thinking, still asleep, that points us toward the root element in plants.

Rudolf Steiner then gave the following assignments:

1. To comprehensively work out the natural history of plants as discussed up to this point;

2. The geographical treatment of the region of the lower Rhine, from the Lahn onward, “in the way I showed you today when speaking of lessons in geography”: mountains, rivers, towns, civilization, and economics.3See Practical Advice to Teachers, lecture 11.

3. Do the same for the basin of the Mississippi.

4. What is the best way to teach the measurement of areas and perimeters?

Elfte Seminarbesprechung

Rudolf Steiner: Bei der sprachlichen Übung, die wir hier vornehmen, handelt es sich ja hauptsächlich um ein Geschmeidigmachen der Sprachorgane.

Sprechübungen:

Ketzer petzten jetzt kläglich

Letztlich leicht skeptisch

Man sollte sich gewöhnen, daß die Zunge es wie von selbst sagt.

Zuwider zwingen zwar

Zweizweckige Zwacker zu wenig

Zwanzig Zwerge

Die sehnige Krebse

Sicher suchend schmausen

Daß schmatzende Schmachter

Schmiegsam schnellstens

Schnurrig schnalzen

Ganz vollkommen sind diese letzten Dinge nur, wenn sie auswendig gesagt werden, ebenso das vorige.

Aus «Wir fanden einen Pfad» von Christian Morgenstern:

Wer vom Ziel nicht weiß,

Kann den Weg nicht haben,

Wird im selben Kreis

All sein Leben traben;

Kommt am Ende hin,

Wo er hergerückt,

Hat der Menge Sinn

Nur noch mehr zerstückt.

Rudolf Steiner: Jetzt wollen wir zu unserer Aufgabe gehen, an der wir ja schon lange nagen.

M. gibt ein Verzeichnis von Seelenstimmungen und von den Pflanzen, die diesen Stimmungen zuzuteilen wären.

Rudolf Steiner: Alle diese vorgebrachten Dinge sind so, daß sie einen erinnern an die Zeit der Phrenologie, wo man in beliebiger Weise menschliche Seeleneigenschaften zusammengelesen hat, und dann allerlei Erhebungen am Kopf gesucht und diese mit menschlichen Seeleneigenschaften zusammengebracht hat. So sind aber die Dinge nicht, obwohl das menschliche Haupt durchaus als Ausdruck der Seelenbildung gefaßt werden kann. Man kann sagen, wenn jemand eine ganz stark vorspringende Stirn hat, so kann er ein Philosoph sein, während er mit nach hinten fliehender Stirn, wenn er begabt ist, ein Künstler werden kann. Man kann nicht sagen, der Künstler «sitzt» irgendwo, aber man kann mit der Empfindung unterscheiden, was in die eine oder in die andere Form hineinfließt. Nun handelt es sich darum, daß man die Seele in dieser Weise anschaut: was mehr intellektualistisch ist, das treibt in die Stirn hinein; was mehr künstlerisch ist, das läßt die Stirn verlaufen. — So ist es auch bei diesem Suchen unter den Pflanzen. Ich meine, man sollte nicht so äußerlich suchen, sondern man sollte mehr ins Innere eindringen und die tatsächlichen Verhältnisse schildern.

I. macht Ausführungen dazu.

Rudolf Steiner: Wenn Sie zu sehr nur nach den Sinnen sehen, werden Sie den Gesichtspunkt etwas verrücken. Die Sinne kommen insofern in Betracht, als von jedem Sinn aus etwas in unserer Seele lebt, was von diesem Sinn wahrgenommen wird. Wir verdanken zum Beispiel dem Sehsinn eine Anzahl von seelischen Erlebnissen; anderen Sinnen verdanken wir andere Erlebnisse der Seele, die von den Sinnen herkommen. Da können wir dann Erlebnisse in unserer Seele zurückdatieren zu diesen Sinnen. Dadurch kommt der Sinn in Zusammenhang mit dem Seelischen. Aber direkt sollte man nicht für die Pflanzen geltend machen, daß sie die Sinne der Erde ausdrücken. Das tun sie nicht.

S. führt Beispiele an aus den Schriften von Emil Schlegel, dem homöopathischen Arzt in Tübingen.

Rudolf Steiner: Auch Schlegel vergleicht noch zu äußerlich. Er geht dabei zurück auf das, was bei den Mystikern zu finden ist, bei Jakob Böhme und anderen, auf die sogenannten «Signaturen». Die mittelalterlichen Mystiker kannten gewisse Beziehungen zur seelischen Welt und hatten daraus auch tiefere medizinische Gesichtspunkte. Wenn man findet: diese bestimmte Pflanzengruppe steht in Beziehung zu einer seelischen Eigenschaft — zum Beispiel Pilze stehen in besonderer Beziehung zu der seelischen Eigenschaft des viel Nachdenkens, des viel Überlegens, des So-seelisch-Lebens, daß man zu diesem seelischen Erleben nicht viel braucht aus der Außenwelt, sondern alles mehr aus sich selbst herauspumpt -, dann wird man wiederum finden, daß diese seelische Eigenschaft, die im Grunde genommen auf die Pilze hinweist, sehr intime Beziehungen zu allen kopfschmerzartigen Krankheiten hat. Daraus wird man auf Beziehungen von Pilzen zu kopfschmerzartigen Krankheiten kommen. In der Tierlehre kann man diese Vergleiche nicht so machen.

Eine ordentliche Anordnung der Pflanzen gibt es heute noch nicht. Sie müssen versuchen, gerade durch die Beziehungen des menschlichen Seelischen zu den Pflanzen Ordnung in das Pflanzenleben selbst hineinzubekommen. Wir wollen eine Ordnung des Pflanzenreiches haben.

Sie müssen zuerst an der Pflanze unterscheiden dasjenige, was berechtigte Teile an der Pflanze sind: Wurzel, Stengel, der zum Stamm auswachsen kann, Blätter, Blüten, Früchte. Die Pflanzen gliedern sich so in der Welt, daß bei der einen Pflanzengattung mehr die Wurzel ausgebildet ist; das andere verkümmert. Bei anderen sind mehr die Blätter ausgebildet, bei anderen mehr die Blüten; sie sind fast nur Blüte. Die Dinge müssen verhältnismäßig genommen werden. Wir bekommen eine Gliederung der Pflanzen, indem wir darauf sehen, welche Organsysteme, Wurzel, Stamm, Blatt und so weiter überwiegen, dadurch unterscheiden sich die Pflanzen in gewisser Beziehung voneinander. Wenn Sie nun alles Blütenhafte als zu einer gewissen Seeleneigenschaft gehörig erkennen, so werden Sie auch die anderen Organsysteme wiederum anderen Seeleneigenschaften zuteilen müssen. So daß es also eins und dasselbe ist, einzelne Teile zu den Seeleneigenschaften zu rechnen, und das ganze Pflanzenreich dazuzurechnen. Das ganze Pflanzenreich ist eigentlich wiederum eine einzige Pflanze.

Wie ist es denn eigentlich mit dem Schlafen und Wachen der Erde? Jetzt schläft die Erde bei uns, aber bei den Gegenfüßlern erwacht sie. Sie trägt den Schlaf auf die andere Seite. Daran nimmt natürlich auch die Pflanzenwelt teil, und das bedingt auch Unterschiede der Vegetation. Da bekommen Sie dann die Möglichkeit, nach dieser räumlichen Verteilung von Schlafen und Wachen auf der Erde, das heißt nach Sommer und Winter, eine Gliederung, eine Einteilung der Pflanzen herauszubekommen. Es ist ja unsere Vegetation nicht dieselbe wie beim Gegenfüßler. Wir werden hier nur Rücksicht nehmen auf die schlafende und wachende Seele, wie wir sie bei uns kennen. Zu den Blättern gehört bei den Pflanzen alles; alles an ihnen ist umgewandeltes Blatt.

Ein Teilnehmer vergleicht Pflanzengruppen mit Temperamenten.

Rudolf Steiner: Man kommt auf eine schiefe Ebene, wenn man die Ternperamente unmittelbar auf das Pflanzenreich bezieht.

Wir wollen einmal folgendes sagen; wir sind ja nach unserem Lehrplan, wenn wir das Pflanzenreich zu lehren anfangen, gegen das elfte Jahr der Kinder. Wir sagen: «Kinder! Ihr waret doch nicht immer so groß, als ihr jetzt seid. Ihr habt eine ganze Menge gelernt, was ihr früher nicht gekonnt habt. Ihr waret, wie euer Leben angefangen hat, klein und ungeschickt und habt das Leben noch nicht führen können. Damals konntet ihr, wie ihr noch ganz klein waret, noch nicht einmal sprechen. Ihr konntet auch noch nicht gehen. Ihr habt vieles nicht gekonnt, was ihr jetzt könnt. Besinnen wir uns einmal alle, denken wir zurück an die Eigenschaften, die ihr gehabt habt, wie ihr ganz kleine Kinder waret. Könnt ihr euch erinnern an die Eigenschaften, die ihr da gehabt habt? Könnt ihr euch erinnern? Könnt ihr euch erinnern, was ihr da getan habt?» Man fragt so fort, bis alle einsehen und «nein» sagen.

«Ihr wißt also alle nichts über dasjenige, was ihr getan habt, wie ihr ganz kleine Pürzelchen waret. — Ja, liebe Kinder, gibt es nicht noch etwas anderes in euch, von dem ihr auch nicht wißt hinterher, was ihr getan habt?» Die Kinder denken nach. Vielleicht ist einer dabei, der darauf kommt, andernfalls führt man sie darauf hin. Es kann dann die Antwort kommen von einem: «Wie ich geschlafen habe.» - «Ja, es geht euch also da gerade so, wenn ihr klein seid, wie wenn ihr im Bett liegt und schlaft. Da schlaft ihr also als ganz kleine Sputzi, und da schlaft ihr, wenn ihr im Bett liegt.

Nun gehen wir in die Natur hinaus und suchen etwas, was da draußen in der Natur so schläft, wie ihr geschlafen habt, als ihr noch ein ganz kleines Sputzi waret. Ihr könnt natürlich nicht selber draufkommen, aber diejenigen, die so etwas wissen, die wissen, daß so fest, wie ihr schlaft, wenn ihr ein ganz kleines Sputzi seid, alles das schläft, was ihr im Walde als Pilze und Schwämme finder. Pilze, Schwämme, sind kindschlafende Seelen.

Jetzt kam die Zeit, wo ihr sprechen und gehen gelernt habt. Ihr wißt das von euren kleinen Geschwistern, daß man zuerst sprechen und gehen lernt. Das Sprechen zuerst und dann das Gehen, oder das Gehen zuerst und dann das Sprechen. Da ist eine Eigenschaft, die eure Seele dazubekommt, die habt ihr von Anfang an nicht gehabt. Ihr habt etwas dazugelernt, ihr könnt dann mehr, wenn ihr gehen und sprechen könnt.

Jetzt gehen wir in die Natur hinaus und suchen uns wiederum etwas, was auch mehr kann als die Schwämme und Pilze. «Das sind Algen» ich muß jetzt dem Kinde etwas von Algen vorführen — «das sind Moose» — ich muß dem Kinde Moose zeigen. — «Was da drinnen in Algen und Moosen ist, das kann schon viel mehr, als was in den Pilzen drinnen ist.»

Dann zeige ich dem Kinde ein Farnkraut und sage: «Sieh mal, das Farnkraut, das kann noch viel mehr als die Moose. Das Farnkraut, das kann schon so viel, daß man sagen muß, es sieht so aus, wie wenn es schon Blätter hätte. Es ist schon Blattartiges daran. Ja, du erinnerst dich nicht, was du getan hast, als du sprechen und gehen gelernt hast. Da warst du immer ziemlich schlafend. Aber wenn du deine Geschwister anschaust oder andere kleine Kinder, dann weißt du, daß sie dann später nicht mehr so lang schlafen als im Anfang. Aber einmal kam der Zeitpunkt, bis zu dem ihr euch zurückerinnert, wo eure Seele aufwachte. Denkt nur daran! Der Zeitpunkt, der da in eurer Seele gewesen ist, der läßt sich vergleichen mit den Farnen. Aber immer besser könnt ihr euch an euer Seelenleben erinnern, immer besser und besser. Wir wollen uns einmal ganz klar sein darüber, wie ihr dazu gekommen seid, «Ich» zu sagen. Es ist ungefähr der Zeitpunkt, bis zu dem ihr euch erinnern könnt. Aber das «Ich» kam so nach und nach. Zuerst sagtet ihr immer «der Wilhelm», wenn ihr euch selber meintet.» Nun läßt man sich von dem Kinde so etwas erzählen, was es von seiner Kindheit weiß. Dann sagt man zu ihm: «Sieh mal, vorher war es wirklich so in deiner Seele, wie wenn alles schläft; da war es wirklich Nacht in deiner Seele. Aber nun ist sie erwacht. Jetzt ist mehr in dir erwacht als früher, sonst wärest du nicht gescheiter. Aber da mußt du doch noch immer wieder schlafen. Es ist nicht alles in dir erwacht, es schläft noch vieles. Es ist erst ein Teil erwacht.

Deine seelischen Eigenschaften, wie du so vier, fünf Jahre alt geworden bist, die, ja, die kommen dem nahe, was ich dir jetzt zeige.» Wir werden dem Kind irgendwelche Pflanzen vorführen aus der Familie der Gymnospermen, der Nadelhölzer, die sich nur etwas vollkommener gestalten als die Farne, und dann werden Sie dem Kinde sagen: «Sieh einmal, dann gibt es in deinem späteren Seelenleben, wie du sechs oder sieben Jahre alt geworden bist, das, daß du hast in die Schule gehen können, und alle die Freuden, die dir die Schule gebracht hat, die gingen dann in deiner Seele auf.» - Da macht man ihm klar, indem man ihm eine Pflanze aus der Familie der Nadelhölzer, der Gymnospermen vorführt: «Sieh mal, die haben noch keine Blüten. So war es mit deiner Seele, ehe du in die Schule gekommen bist.

Jetzt aber, wo du in die Schule gekommen bist, da kam in deine Seele etwas hinein, was sich nur mit der blühenden Pflanze vergleichen läßt. Aber sieh, da hast du zuerst nur wenig gelernt, wie du so acht, neun Jahre alt warst. Jetzt bis du schon ein ganz gescheites Wesen, schon elf Jahre alt, jetzt hast du schon eine ganze Menge gelernt.

Sieh einmal, da reiche ich dir eine Pflanze, die hat solche Blätter, einfach streifennervige (Zeichnung 1). Und da reiche ich dir eine Pflanze, die hat solche Blätter, kompliziertere Blätter, netznervige (Zeichnung 2). Und wenn du die Blüten anschaust, bei denen (Zeichnung 1), da sind sie anders als bei den Pflanzen, die solche Blätter haben (Zeichnung 2). Deren Blüten sind komplizierter, und alles ist komplizierter bei denen, die solche netznervigen Blätter haben (Zeichnung 2), als bei denen, die solche streifennervigen haben (Zeichnung 1).»

Jetzt weist man dem Kinde so etwas vor wie Herbstzeitlose, Monokotyledonen. Bei denen ist alles einfach. Das vergleicht man mit dem siebenten, achten, neunten Jahre.

Und dann geht man dazu über, zeigt dem Kinde solche Pflanzen, welche die Blüten oben einfach haben, so daß sie noch nicht ordentliche Blumenblätter haben. Man sagt: «Da hast du Pflanzen, wo du an der Blüte noch nicht unterscheiden kannst grüne Blättchen und farbige Blättchen; solche, wo du die Blättchen unten an der Blüte noch nicht unterscheiden kannst von denen, die die Blüte oben hat. Das bist du! Das bist du jetzt!

Und später, da wirst du noch älter! Wenn du zwölf, dreizehn, vierzehn Jahre alt sein wirst, da wirst du dich vergleichen können mit solchen Pflanzen, die Kelch und Blütenblätter haben. Da wirst du in deiner Seele so sein, daß du unterscheiden kannst grüne Blätter, die man den Kelch nennt, und farbige Blätter, die man die Blumenblätter nennt. Das mußt du aber erst werden»! — So läßt man die Pflanzen unterscheiden in Pflanzen mit einfacher Blütenhülle = elfjährige Kinder, und Pflanzen mit doppelter Blütenhülle = dreizehn- bis vierzehnjährige Kinder. «Das wirst du erst!»

Und nun können Sie wunderschön dem Kinde irgend zwei, drei Exemplare Moose, Farne, Gymnospermen, Monokotyledonen, Dikotyledonen vorführen. Nun können Sie wunderschön sich ergehen darinnen, daß das Kind sich erinnern soll. Und Sie lassen erzählen vom kleinen vierjährigen Wilhelm, führen das Farnkraut vor, lassen erzählen vom siebenjährigen Fritz und führen da vor die entsprechende Pflanze, lassen erzählen den elfjährigen Ernst und führen die andere Pflanze vor. Sie bringen das Kind dahin, daß es sich besinnt auf die Seeleneigenschaften des werdenden Kindes. Und dann übertragen Sie das ganze Wachstum der werdenden Seele auf die Pflanze, nehmen das zu Hilfe, was ich gestern gesagt habe vom Baum, da bekommen Sie die Seeleneigenschaften parallelisiert mit den entsprechenden Pflanzen.

Da ist Prinzip darin! Da wird nicht in beliebiger Weise das eine mit dem anderen parallelisiert, wie man es gerade aufliest. Da ist Prinzip darinnen, Gestaltung! Das muß darin sein! Sie bekommen das ganze Pflanzenreich heraus, mit Ausnahme desjenigen, was in der Pflanze entsteht, wenn die Blüte Frucht bringt. Sie machen das Kind aufmerksam, daß aber die höheren Pflanzen aus ihren Blüten Früchte hervorbringen: «Das kann man mit eurer Seele erst vergleichen, wenn ihr aus der Schule herausgekommen seid.» — Alles, was bis zur Blüte geht, kann man nur vergleichen mit dem, was bis zur Geschlechtsreife geht. Den Befruchtungsvorgang, den läßt man draußen für Kinder, den kann man darin nicht haben.

Nun sage ich noch etwa: «Seht, liebe Kinder, wie ihr ganz klein waret, da habt ihr doch eigentlich nur so etwas wie eine schlafende Seele gehabt.» - Nun, je nachdem es ist, erinnert man das Kind daran: «Nun, sieh mal, woran hast du denn deine Hauptfreude gehabt als kleines Kind? Du hast es jetzt vergessen, weil du es verschlafen hast, aber du siehst es jetzt beim Annchen oder Mariechen, bei deinem kleinen Schwesterchen. Woran hat denn das die größte Freude? Zuerst am Schnuller oder der Milchflasche. Nicht wahr, da hat auch die Seele noch die größte Freude am Schnuller oder an der Milchflasche. Dann kommt erst die Zeit bei dem größeren Brüderchen oder Schwesterchen, wo man nicht bloß Freude an der Milchflasche hat, wo man Freude hat, wenn man spielen darf. — Ja, sieh, da habe ich dir zuerst gesprochen von den Pilzen, von den Algen, von den Moosen. Die haben fast alles, was sie haben, von der Erde. Wir müssen in den Wald gehen, wenn wir sie kennenlernen wollen. Da wachsen sie, wo es feucht ist, wo es schattig ist. Die getrauen sich nicht recht heraus in die Sonne. Das ist so, wie deine Seele war, als du dich noch nicht herausgetrautest zum Spielen, sondern mit Milch und Saugflasche dich vergnügtest. Bei dem, was die andere Pflanzenwelt ist, da ist es so, daß Blätter und Blüten sich entwickeln, wenn die Pflanze nun nicht mehr bloß das hat, was sie von der Erde, vom schattigen Wald hat, sondern wenn sie an die Sonne, an Luft und Licht herauskommt. Das sind die seelischen Eigenschaften, die an Licht und Luft’gedeihen.» — So zeige man dem Kinde den Unterschied zwischen dem, was unten wie der Pilz oder wie Wurzeln lebt und das braucht, was unten Wässeriges, Erde und Schatten ist, und dem, was Luft und Licht braucht wie Blüten und Blätter. - «Daher sind auch diejenigen Pflanzen, die Blüten und Blätter tragen, weil sie Luft und Licht lieben, die sogenannten «höheren» Pflanzen, wie du, wenn du fünf oder sechs Jahre alt bist, das höhere Alter hast als damals mit dem Schnuller.»

Wenn man immer mehr und mehr herüber- und hinüberlenkt die Gedanken von den seelischen Eigenschaften, wie sie sich entwickeln im kindlichen Alter, zu den Pflanzen, dann bekommt man die Möglichkeit, alles in entsprechender Weise einzuteilen. Daher kann man sagen:

Säuglings-Seelenfreuden: Pilze, Schwämme

Erste kindliche Seelenfreuden, Seelenschmerzen und Affekte: Algen, Moose

Erlebnisse an der Entstehung des Selbstbewußtseins: Farne

Erlebnisse im späteren Zeitalter bis zur Schule, mit vier bis fünf Jahren: Gymnospermen, Nadelhölzer

Erste Schulerlebnisse, siebentes, achtes, neuntes Jahr bis zum elften Jahr hin: Streifennervige Pflanzen, Monokotyledonen; Pflanzen mit einfacher Blütenhülle Erlebnisse der Elfjährigen: Einfache Dikotyledonen

Schulerlebnisse vom zwölften bis fünfzehnten Jahr: Netznervige Pflanzen, Dikotyledonen; Pflanzen, die einen grünen Kelch und farbige Blumenblätter haben,

«also Erlebnisse an dem, wofür ihr jetzt noch zu dumm seid, was ihr jetzt noch nicht wißt, was ihr erst werdet mit dem dreizehnten, vierzehnten Jahr: an dem, wo ein grüner Kelch ist und eine farbige Blüte. Freut euch! Ihr werdet einmal so reich in eurer Seele sein, daß ihr gleicht der Rose mit farbigem Blumenblatt und grünem Kelchblatt. Das ist etwas, was erst wird, aber freut euch! Das ist schön, wenn man sich freuen kann auf das, was man erst wird.» — Freude machen auf die Zukunft! Daß man Freude damit macht, darauf kommt es an.

Also die aufeinanderfolgenden seelischen Eigenschaften bis zur Geschlechtsreife hin kann man mit dem Pflanzenreiche vergleichen. Dann geht der Vergleich nicht mehr weiter, weil da das Kind den Astralleib entwickelt, den die Pflanze nicht mehr hat. Aber wenn die Pflanze über sich selbst hinaustreibt bis in die Befruchtung hinein, so kann man das mit seelischen Eigenschaften des sechzehnten, siebzehnten Jahres vergleichen. Man braucht aber gar nicht auf den Befruchtungsvorgang aufmerksam zu machen, sondern auf den Wachstumsvorgang, weil das der Realität entspricht. Dem Befruchtungsvorgang bringen die Kinder kein Verständnis entgegen, aber dem Wachstumsvorgang, weil er sich vergleichen läßt mit dem Wachstumsvorgang der Seele. So wie die Seele des Kindes sich unterscheidet in den verschiedenen Lebensjahren, so unterscheiden sich die Pflanzen von den Pilzen bis zum Hahnenfuß, der gewöhnlich zu den Höchstentwickelten, zu den Ranunkulazeen, gerechnet wird. Es ist wirklich so, wenn die gelben Hahnenfüße im Frühling herauskommen auf den saftigen Wiesen, so erinnert das an die seelische Verfassung, an die seelische Stimmung vierzehn-, fünfzehnjähriger Knaben und Mädchen.

Wird einmal ein wirklich systematisierender Botaniker so vorgehen, so wird er auch ein Pflanzensystem herausbekommen, das den Tatsachen entspricht. Aber den Kindern kann man wirklich die ganze äußere Pflanzenwelt als ein Bild der sich entwickelnden Kinderseele vorführen. Da kann man ungeheuer viel tun.

Man soll nicht in dieser vereinzelnden Art, wie die alten Phrenologen es haben, unterscheiden, sondern man soll einen Gesichtspunkt, der durchführbar ist, drinnen haben. Da werden Sie finden, daß es nicht ganz richtig ist, einfach ohne weiteres alles Wurzelhafte mit dem Denken in eins zu beziehen. Beim Kinde ist ja das Geistige im Kopfe noch schlafend. Also nicht das Denken im Allgemeinen, sondern das kindlich Denkende, das noch schläft, ist nach dem Wurzelhaften hin zu orientieren. So bekommen Sie von dem schlafenden Denken in den Pilzen sowohl wie in dem Kinde ein Bild, wie das kindlich Denkerische, das noch schläft, mehr nach dem Wurzelhaften hin gerichtet ist.

Rudolf Steiner stellt dann folgende Aufgaben:

Erstens: Sich eine zusammenfassende Gestaltung der bisherigen Pflanzengeschichte zurechtlegen.

Zweitens: Geographische Behandlung der Niederrheingegend, etwa von der Lahn an, in der Art, wie ich heute über den Geographieunterricht gesprochen habe: Gebirge, Flüsse, Städte, Kulturelles, Wirtschaftliches.

Drittens: Dasselbe für die Gegend des Mississippi.

Viertens: Wie unterrichtet man am besten über Flächenberechnung und Umfangberechnung von Flächen?

Eleventh Seminar Discussion

Rudolf Steiner: The language exercises we are doing here are mainly about making the speech organs more supple.

Speech exercises:

Heretics now snitched pitifully

Ultimately slightly skeptical

One should get used to the tongue saying it as if by itself.

Adverse compulsion

Dual-purpose Zwacker too little

Twenty dwarves

The sinewy crabs

Searching confidently, feasting

That smacking smackers

Supple as quickly as possible

Snapping purrily

These last things are only perfect when said from memory, as is the previous one.

From “We Found a Path” by Christian Morgenstern:

Those who do not know their destination,

Cannot find the way,

Will trot in the same circle

All their lives;

Will end up

Where they started,

Has the meaning of the crowd

Only further fragmented.

Rudolf Steiner: Now let us turn to our task, which we have been gnawing at for a long time.

M. gives a list of soul moods and the plants that could be assigned to these moods.

Rudolf Steiner: All these things that have been put forward are reminiscent of the time of phrenology, when human soul characteristics were read in any way one liked, and then all kinds of elevations were sought on the head and these were brought together with human soul characteristics. But that is not how things are, although the human head can certainly be understood as an expression of the formation of the soul. One could say that if someone has a very prominent forehead, they may be a philosopher, while if they have a receding forehead, they may be an artist, if they are gifted. One cannot say that the artist “sits” somewhere, but one can distinguish with one's senses what flows into one form or the other. Now it is a matter of looking at the soul in this way: what is more intellectual drives into the forehead; what is more artistic causes the forehead to recede. — It is the same with this search among plants. I think one should not search so externally, but should penetrate more into the inner life and describe the actual conditions.

I. elaborates on this.

Rudolf Steiner: If you look too much at the senses alone, you will shift your point of view somewhat. The senses come into consideration insofar as something lives in our soul from each sense that is perceived by that sense. For example, we owe a number of soul experiences to the sense of sight; we owe other experiences of the soul to other senses, which come from the senses. We can then trace experiences in our soul back to these senses. This brings the senses into connection with the soul. But one should not directly claim that plants express the senses of the earth. They do not do that.

S. cites examples from the writings of Emil Schlegel, the homeopathic physician in Tübingen.

Rudolf Steiner: Schlegel also makes too superficial a comparison. He goes back to what can be found in the mystics, in Jakob Böhme and others, to the so-called “signatures.” Medieval mystics knew certain relationships to the spiritual world and also had deeper medical insights from this. If one finds that this particular group of plants is related to a spiritual quality — for example, mushrooms have a special relationship to the spiritual quality of thinking a lot, of reflecting a lot, of spiritual life that one does not need much from the outside world for this spiritual experience, but rather draws everything more from within oneself — then one will find that this spiritual quality, which basically points to mushrooms, has very intimate relationships with all headache-like illnesses. From this, one will arrive at relationships between mushrooms and headache-like illnesses. In zoology, these comparisons cannot be made.

There is still no proper classification of plants today. You must try to bring order into plant life itself, precisely through the relationships between the human soul and plants. We want to have an order in the plant kingdom.

First, you must distinguish between the legitimate parts of the plant: roots, stems that can grow into trunks, leaves, flowers, and fruits. Plants are structured in such a way that in one plant genus, the roots are more developed, while in another, they are stunted. In others, the leaves are more developed, in others the flowers; they are almost entirely flower. Things must be taken in proportion. We obtain a classification of plants by looking at which organ systems, root, stem, leaf, and so on, predominate, whereby the plants differ from each other in a certain respect. If you now recognize everything flower-like as belonging to a certain soul quality, you will also have to assign the other organ systems to other soul qualities. So it is one and the same thing to count individual parts as soul qualities and to include the entire plant kingdom. The entire plant kingdom is actually a single plant.

What about the sleeping and waking of the earth? Now the earth is sleeping here, but it is awakening in the antipodes. It carries sleep to the other side. The plant world naturally participates in this, and this also causes differences in vegetation. This gives you the opportunity to work out a structure, a classification of plants, according to this spatial distribution of sleeping and waking on the earth, that is, according to summer and winter. Our vegetation is not the same as that of the antipodes. Here we will only consider the sleeping and waking soul as we know it. Everything in plants belongs to the leaves; everything about them is transformed leaf.

One participant compares plant groups with temperaments.

Rudolf Steiner: One gets onto a slippery slope when one relates the temperaments directly to the plant kingdom.

Let us say the following: according to our curriculum, when we begin to teach the plant kingdom, we are approaching the eleventh year of the children's lives. We say: "Children! You were not always as big as you are now. You have learned a great deal that you could not do before. When your life began, you were small and clumsy and could not yet lead a life. Back then, when you were still very small, you could not even speak. You could not walk either. There were many things you couldn't do that you can do now. Let's all think back and remember the characteristics you had when you were very small children. Can you remember the characteristics you had then? Can you remember? Can you remember what you did then?“ We keep asking until everyone understands and says ”no."

“So you all know nothing about what you did when you were very little. — Yes, dear children, isn't there something else in you that you don't know what you did afterwards?” The children think about it. Perhaps one of them will come up with an answer, otherwise you can guide them. One of them may then answer: “How I slept.” — “Yes, when you are small, it is just like when you lie in bed and sleep. You sleep as tiny little babies, and you sleep when you lie in bed.”

Now let's go out into nature and look for something out there in nature that sleeps the way you slept when you were a tiny little Sputzi. Of course, you can't figure it out for yourselves, but those who know such things know that everything you find in the forest, such as mushrooms and sponges, sleeps as soundly as you do when you are a tiny little Sputzi. Mushrooms and sponges are souls sleeping like children.

Now came the time when you learned to speak and walk. You know from your little siblings that you learn to speak first and then to walk. First speaking and then walking, or first walking and then speaking. There is a quality that your soul acquires that you did not have from the beginning. You have learned something new, you can do more when you can walk and talk.

Now let's go out into nature and look for something that can do more than sponges and mushrooms. “These are algae” — now I have to show the child something about algae — “these are mosses” — I have to show the child mosses. — “What is inside algae and mosses can do much more than what is inside mushrooms.”

Then I show the child a fern and say, "Look, the fern can do much more than moss. The fern can do so much that you have to say it looks as if it already had leaves. It already has leaf-like features. Yes, you don't remember what you did when you learned to speak and walk. You were always pretty sleepy then. But when you look at your siblings or other small children, you know that later on they don't sleep as long as they did in the beginning. But there came a time, which you can remember, when your soul awoke. Just think about it! The moment that was in your soul can be compared to ferns. But you can remember your soul life better and better, better and better. Let's be very clear about how you came to say “I.” It's about the moment you can remember. But the “I” came gradually. At first, you always said “the Wilhelm” when you meant yourself. Now let the child tell you something it knows about its childhood. Then say to it: "Look, before, it was really like that in your soul, as if everything were asleep; it was really night in your soul. But now it has awakened. Now more has awakened in you than before, otherwise you would not be smarter. But you still have to sleep again and again. Not everything in you has awakened; much still sleeps. Only a part has awakened.

Your spiritual qualities, as you are now four or five years old, are close to what I am showing you now." We will show the child some plants from the gymnosperm family, the conifers, which are only slightly more perfect in form than the ferns, and then you will say to the child: “Look, then in your later soul life, when you were six or seven years old, you were able to go to school, and all the joys that school brought you blossomed in your soul.” You make this clear to them by showing them a plant from the conifer family, the gymnosperms: “Look, they don't have any flowers yet. That's how it was with your soul before you started school.”But now that you have started school, something has entered your soul that can only be compared to a flowering plant. But look, at first you learned very little when you were eight or nine years old. Now you are already a very intelligent being, already eleven years old, and you have already learned a great deal."

Look, here I am giving you a plant that has leaves like this, with simple veins (drawing 1). And here I am giving you a plant that has leaves like this, more complicated leaves, with reticulate veins (drawing 2). And if you look at the flowers, in the case of (drawing 1), they are different from the plants that have such leaves (drawing 2). Their flowers are more complex, and everything is more complex in those that have such reticulate leaves (drawing 2) than in those that have such striate leaves (drawing 1)."

Now you show the child something like autumn crocuses, monocotyledons. Everything is simple with them. You compare that with the seventh, eighth, and ninth years.

And then you move on to showing the child plants that have simple flowers at the top, so that they do not yet have proper petals. They say: “Here you have plants where you cannot yet distinguish between green leaves and colored leaves on the flower; plants where you cannot yet distinguish the leaves at the bottom of the flower from those at the top. That is you! That is you now!”

And later, when you get older! When you are twelve, thirteen, fourteen years old, you will be able to compare yourself to plants that have calyxes and petals. Then you will be able to distinguish between the green leaves, called calyxes, and the colored leaves, called petals. But you must first become that!" — This is how plants are distinguished into plants with a simple perianth = eleven-year-old children, and plants with a double perianth = thirteen- to fourteen-year-old children. “You will become that!”

And now you can beautifully show the child two or three specimens of mosses, ferns, gymnosperms, monocotyledons, and dicotyledons. Now you can delight in the fact that the child should remember. And you let them talk about little four-year-old Wilhelm, show them the fern, let them talk about seven-year-old Fritz and show them the corresponding plant, let them talk about eleven-year-old Ernst and show them the other plant. You lead the child to reflect on the soul qualities of the unborn child. And then you transfer the entire growth of the developing soul to the plant, using what I said yesterday about the tree to help you, and you get the soul characteristics paralleled with the corresponding plants.

There is a principle in this! It is not a matter of arbitrarily paralleling one thing with another, as one might just pick up. There is a principle in it, a design! That must be there! You bring out the whole plant kingdom, with the exception of what arises in the plant when the flower bears fruit. You make the child aware that higher plants produce fruit from their flowers: “You can only compare that with your soul when you have left school.” — Everything that goes up to flowering can only be compared to what goes up to sexual maturity. The process of fertilization is left out for children; it cannot be included.

Now I say something like: "Look, dear children, when you were very small, you actually only had something like a sleeping soul. “ - Well, depending on the situation, you remind the child: ”Well, look, what was your main joy as a small child? You've forgotten it now because you've slept through it, but you can see it now in Annchen or Mariechen, your little sister. What gives her the greatest joy? First of all, the pacifier or the milk bottle. Isn't that right, the soul also has the greatest joy in the pacifier or the milk bottle. Then comes the time with the older brother or sister, when you don't just enjoy the milk bottle, when you enjoy being allowed to play. — Yes, you see, that's when I first told you about the mushrooms, the algae, the mosses. They get almost everything they have from the earth. We have to go into the forest if we want to get to know them. They grow where it is damp, where it is shady. They don't really dare to come out into the sun. That is how your soul was when you didn't dare to come out to play, but enjoyed yourself with milk and a feeding bottle. In the other plant world, leaves and flowers develop when the plant no longer has only what it gets from the earth and the shady forest, but when it comes out into the sun, air, and light. These are the qualities of the soul that thrive on light and air." — So show the child the difference between what lives below, like mushrooms or roots, and needs what is below, water, earth, and shade, and what needs air and light, like flowers and leaves. - “Therefore, those plants that bear flowers and leaves because they love air and light are the so-called ‘higher’ plants, just as you, at five or six years of age, are older than you were when you had a pacifier.”

If you increasingly shift your thoughts from the soul qualities that develop in childhood to plants, you will be able to classify everything in an appropriate way. Therefore, we can say:

Infant soul joys: mushrooms, sponges

First childhood joys, pains, and emotions: algae, mosses

Experiences in the development of self-awareness: ferns

Experiences in later childhood up to school age, four to five years old: gymnosperms, conifers

First school experiences, seventh, eighth, ninth to eleventh years: striped-veined plants, monocotyledons; plants with simple perianth Experiences of eleven-year-olds: simple dicotyledons

School experiences from the twelfth to fifteenth years: net-veined plants, dicotyledons; plants that have a green calyx and colored petals,

"that is, experiences of what you are still too stupid for, what you do not yet know, what you will only become at the age of thirteen or fourteen: where there is a green calyx and a colored flower. Rejoice! One day you will be so rich in your soul that you will resemble the rose with its colored petals and green calyx. This is something that is yet to come, but rejoice! It is wonderful to be able to rejoice in what you will become." — Rejoice in the future! The important thing is to rejoice in it.

So the successive soul qualities up to sexual maturity can be compared to the plant kingdom. Then the comparison ends, because the child develops the astral body, which the plant no longer has. But when the plant grows beyond itself into fertilization, this can be compared to the soul qualities of the sixteenth and seventeenth years. However, it is not necessary to draw attention to the process of fertilization, but rather to the process of growth, because that corresponds to reality. Children do not understand the process of fertilization, but they do understand the process of growth, because it can be compared to the growth process of the soul. Just as the soul of a child differs in different years of life, so plants differ from mushrooms to buttercups, which are usually considered to be among the most highly developed, among the Ranunculaceae. It is really true that when the yellow buttercups come out in spring on the lush meadows, it is reminiscent of the mental state, the mental mood of fourteen- and fifteen-year-old boys and girls.

If a truly systematic botanist were to proceed in this way, he would also arrive at a plant system that corresponds to the facts. But children can really be shown the whole external plant world as an image of the developing child's soul. There is an enormous amount that can be done here.

One should not distinguish in the isolating way that the old phrenologists did, but should have a point of view that is feasible. You will find that it is not entirely correct to simply relate everything root-related to thinking. In children, the spiritual in the head is still dormant. So it is not thinking in general, but childlike thinking, which is still dormant, that needs to be oriented toward the root-related. In this way, you will get a picture of the dormant thinking in mushrooms as well as in children, how the childlike thinking that is still dormant is more oriented toward the root.

Rudolf Steiner then sets the following tasks:

First: to prepare a summary of the history of plants to date.

Second: a geographical treatment of the Lower Rhine region, starting from the Lahn, in the manner in which I spoke today about geography lessons: mountains, rivers, cities, culture, economy.

Third: Do the same for the Mississippi region.

Fourth: What is the best way to teach area calculation and perimeter calculation?