Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

1 September 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Ten

Speech Exercises:

Children chiding

Chaffinch chirping

Choking chimneys

Cheerfully chatteringChildren chiding and fetching

Chaffinch chirping switching

Choking chimneys hitching

Cheerfully chattering twitchingBeach children chiding and fetching

Reach chaffinch chirping switching

Birches choking chimneys hitching

Perches cheerfully chattering twitching

RUDOLF STEINER: The “ch” should be sounded in a thoroughly active way, like a gymnastic exercise.1The original German exercise (which appears in the appendix) uses the “pf ” sound; the “ch” sound has been substituted in the English version.

The following is a piece in which you have to pay attention both to the form and the content.

From “Galgenlieder” by Christian Morgenstern:

The Does’ Prayer

The does, as the hour grows late,

Med-it-ate;

Med-it-nine;

Med-i-ten;

Med-eleven;

Med-twelve;

Mednight!

The does, as the hour grows late,

Meditate,

They fold their little toesies,

the doesies.2Max Knight, trans., University of California Press, Berkeley, 1964.

RUDOLF STEINER: Now we will continue our talk about the plant world.

Various contributions were offered by those present.

RUDOLF STEINER: Later there will be students in the school who will study the plant kingdom on a more scientific basis, in which case they would learn to distinguish mosses, lichens, algae, monocotyledons, dicotyledons, and so on. All children, who in their youth learn to know plants according to scientific principles, should first learn about them as we have described—that is, by comparing them with soul qualities. Later they can study the plant system more scientifically. It makes a difference whether we try first to describe the plants and then later study them scientifically, or vice versa. You can do much harm by teaching scientific botany first, instead of first presenting ideas that relate to the feeling life, as I have tried to show you. In the latter case the children can tackle the study of scientific botanical systems with a truly human understanding.

The plant realm is the soul world of the Earth made visible. The carnation is a flirt. The sunflower an old peasant. The sunflower’s shining face is like a jolly old country rustic. Plants with very big leaves would express, in terms of soul life, lack of success in a job, taking a long time with everything, clumsiness, and especially an inability to finish anything; we think that someone has finished, but the person is still at it. Look for the soul element in the plant forms!

When summer approaches, or even earlier, sleep spreads over the Earth; this sleep becomes heavier and heavier, but it only spreads out spatially, and in autumn passes away again. The plants are no longer there, and sleep no longer spreads over the Earth. The feelings, passions, and emotions of people pass with them into sleep, but once they are there, those feelings have the appearance of plants. What we have invisible within the soul, our hidden qualities—flirtatiousness, for example—become visible in plants. We don’t see this in a person who is awake, but it can be observed clairvoyantly in people who are sleeping. Flirtation, for example, looks like a carnation. A flirt continually produces carnations from the nose! A tedious, boring person produces gigantic leaves from the whole body, if you could see them.

When we express the thought that the Earth sleeps, we must go further: the plant world grows in the summer. Earth sleeps in the summer and is awake during winter. The plant world is the Earth’s soul. Human soul life ceases during sleep, but when the Earth goes to sleep its soul life actually begins. But the human soul does not express itself in a sleeping person. How are we going to get over this difficulty with children?

One of the teachers suggested that plants could be considered the Earth’s dreams.

RUDOLF STEINER: But plants during high summer are not the Earth’s dreams, because the Earth is in a deep sleep in the summer. It is only how the plant world appears during spring and autumn that you can call dreams. Only when the flowers are first beginning to sprout—when the March violet, for example, is still green, before flowers appear, and again when leaves are falling—that the plant world can be compared to dreams. With this in mind, try to make the transition to a real understanding of the plant.

For example, you can begin by saying, “Look at this buttercup,” or any plant we can dig out of the soil, showing the root below, the stalk, leaves, blossoms, and then the stamens and pistil, from which the fruit will develop. Let the child look at a plant like this. Then show a tree and say, “Imagine this tree next to the plant. What can you tell me about the tree? Yes, it also has roots below of course; but instead of a stalk, it has a trunk. Then it spreads its branches, and it’s as if the real plants grew on these branches, because many leaves and flowers can be found there; it’s as if little plants were growing on the branches above. So, we could actually look at a meadow this way: We see yellow buttercups growing all over the meadow; it is covered with individual plants with their roots in the Earth, and they cover the whole meadow. But when we look at the tree, it’s as if someone had taken the meadow, lifted it up, and rounded it into an arch; only then do we find many flowers growing very high all over it. The trunk is a bit of the Earth itself. So we may say that the tree is the same as the meadow where the flowers grow.

“Now we go from the tree to the dandelion or daisy. Here there is a root-like form in the soil, and from it grows something like a stalk and leaves, but at the top there is a little basket of flowers, tiny little blossoms close together. It’s as though the dandelion made a little basket up there with nothing in it but little flowers, perfect flowers that can be found in the dandelion-head. So we have the tree, the little ‘basket-bloomers,’ and the ordinary plant, a plant with a stalk. In the tree it’s as though the plants were only high up on the branches; in the compound flowers the blossom is at the top of the plant, except that these are not petals, but countless fully-developed flowers.

“Now imagine that the plant kept everything down in the Earth; suppose it wanted to develop roots, but that it was unsuccessful—or perhaps leaves, but could not do this either; imagine that the only thing to unfold above ground were what one usually finds in the blossom; you would then have a mushroom. At least, if the roots down below fail and only leaves come up, you would then have ferns. So you find all kinds of different forms, but they are all plants.”

Show the children the buttercup, how it spreads its little roots, how it has its five yellow-fringed petals, then show them the tree, where the “plant” only grows on it, then the composite flowers, the mushroom, and the fern; do not do this in a very scientific way, but so that the children get to know the form in general.

Then you can say, “Why do you think the mushroom remained a mushroom, and why did the tree become a tree? Let’s compare the mushroom with the tree. What is the difference between them? Take the tree. Isn’t it as though the Earth had pushed itself out with all its might—as though the inner being of the tree had forced its way up into the outside world in order to develop its blossoms and fruits away from the Earth? But in the mushroom the Earth has kept within itself what usually grows up out of it, and only the uppermost parts of the plant appear in the form of mushrooms. In the mushroom the ‘tree’ is below the soil and only exists as forces. In the mushroom itself we find something similar to the tree’s outermost part. When lots and lots of mushrooms are spread over the Earth, it is as though you had a tree growing down below them, inside the Earth. And when we look at a tree it is as though the Earth had forced itself up, turning itself inside out, as it were, bringing its inner self into the outer world.”

Now you are coming nearer to the reality: “When you see mushrooms growing you know that the Earth is holding something within itself that, in the case of a growing tree, it pushes up outside itself. So in producing mushrooms the Earth keeps the force of the growing tree within itself. But when the Earth lets the trees grow it turns the growing-force of the tree outward.” Now here you have something not found within the Earth during summer, because it rises out of the Earth then and when winter comes it goes down into the Earth again. “During summer the Earth, through the force of the tree, sends its own force up into the blossoms, causing them to unfold, and in winter it draws this force back again into itself. Now let us think of this force, which during the summer circles up in the trees—a force so small and delicate in the violet but so powerful in the tree. Where can it be found in winter? It is under the surface of the Earth. What happens during the depth of winter to all these plants—the trees, the composite flowers, and all the others? They unfold right under the Earth’s surface; they are there within the Earth and develop the Earth’s soul life. This was known to the people of ancient times, and that was why they placed Christmas—the time when we look for soul life—not in the summer, but during winter.

“Just as a person’s soul life passes out of the body when falling asleep, and again turns inward when a person wakens, so it is also for the Earth. During summer while asleep it sends its sap-bearing force out, and during winter takes it back again when it awakens—that is, it gathers all its various forces into itself. Just think, children, our Earth feels and experiences everything that happens within it; what you see all the summer long in flowers and leaves, the abundance of growth and blossom, in the daisies, the roses, or the carnations—this all dwells under the Earth during winter, and there it has feelings like you have, and can be angry or happy like you.”

In this way you gradually form a view of life lived under the Earth during winter. That is the truth. And it is good to tell the children these things. This is something that even materialists could not argue with or consider an extravagant flight of fancy. But now you can continue from this and consider the whole plant. The children are led away from a subjective attitude toward plants, and they are shown what drives the sap over the Earth during summer heat and draws it back again into itself in winter; they come to see the ebb and flow in plant life. In this way you find the Earth’s real soul life mirrored in plants. Beneath the Earth ferns, mosses, and fungi unfold all that they fail to develop as growing plants, but this all remains etheric substance and does not become physical. When this etheric plant appears above the Earth’s surface, the external forces work on it and transform it into the rudiments of leaves we find in fungi, mosses, and ferns. But under a patch of moss or mushrooms there is something like a gigantic tree, and if the Earth cannot absorb it, cannot keep it within itself, then it pushes up into the outer world.

The tree is a little piece of the Earth itself. But what remains underground in mushrooms and ferns is now raised out of the Earth, so that if the tree were slowly pushed down into the Earth everything would be different, and if it were to be thus submerged then ferns, mosses, and mushrooms would appear; for the tree it would be a kind of winter. But the tree withdraws from this experience of winter. It is the nature of a tree to avoid the experience of winter to some extent, but if I could take hold of a fern or a mushroom by the head and draw it further and further out of the Earth so that the etheric element in it reached the air, then I would draw out a whole tree, and what would otherwise become a mushroom would now turn into a tree. Annual plants are midway between these two. A composite flower is merely another form of what happens in a tree. If I could press a composite flower down into the Earth it would bear only single blossoms. A composite flower could almost be called a tree that has shot up too quickly.

And so we can also find a wish, a desire, living in the Earth. The Earth feels compelled to let this wish sink into sleep. The Earth puts it to sleep in summer, and then the wish rises as a plant. It is not visible above the Earth until it appears as a water-lily. Down below it lives as a wish in the Earth, and then up above it becomes a plant.

The plant world is the Earth’s soul world made visible, and this is why we can compare it with human beings. But you should not merely make comparisons; you must also teach the children about the actual forms of the plants. Starting with a general comparison you can then lead to the single plant species.

Light sleep can be compared with ordinary plants, a kind of waking during sleep with mushrooms (where there are very many mushrooms, the Earth is awake during the summer), and you can compare really sound deep sleep with the trees.

From this you see that the Earth does not sleep as people do, but in one part it is more asleep and in another more awake; here more asleep, there more awake. People, in their eyes and other sense organs, also have sleeping, waking, and, dreaming side by side, all at the same time.

Now here is your task for tomorrow. Please make out a table; on the left place a list of the human soul characteristics, from thoughts down through all the emotions of the soul—feelings of pleasure and displeasure, actively violent emotions, anger, grief, and so on, right down to the will; certain specific plant forms can be compared with the human soul realm. On the right you can then fill in the corresponding plant species, so that in the table you have the thought plants above, the will plants below, and all the others in between.

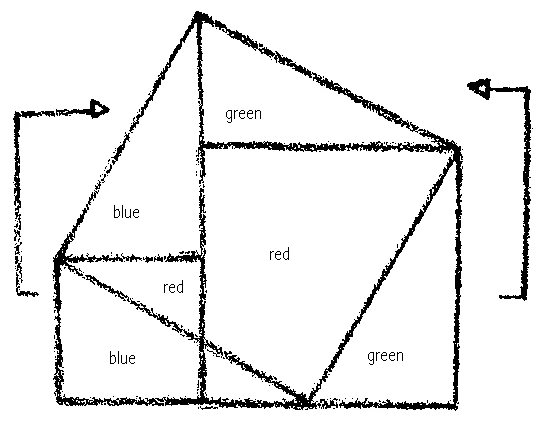

Rudolf Steiner then gave a graphic explanation of the Pythagorean theorem and referred to an article by Dr. Ernst Müller in Ostwald’s magazine for natural philosophy, Annalen der Naturphilosophie, entitled “Some Observations on a Theory of Knowledge underlying the Pythagorean theorem.”

In the drawing, the red parts of the two smaller squares already lie within the square on the hypotenuse. By moving the blue and the green triangles in the direction of the arrows, the remaining parts of the two smaller squares will cover those parts of the square on the hypotenuse still uncovered.

You should cut out the whole thing in cardboard and then you can see it clearly.3The Pythagorean theorem states that the square of the hypotenuse of a right triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. For another brief discussion of the Pythagorean theorem in teaching see Rudolf Steiner, The Kingdom of Childhood: Introductory Talks on Waldorf Education, Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, NY, 1995, pp. 85–90.

Zehnte Seminarbesprechung

Sprechübungen:

Pfiffig pfeifen aus Näpfen

Pfäffische Pferde schlüpfend

Pflegend Pflüge hüpfend

Pferchend Pfirsiche knüpfendKopfpfiffig pfeifen aus Näpfen

Napfpfäffische Pferde schlüpfend

Wipfend pflegend Pflüge hüpfend

Tipfend pferchend Pfirsiche knüpfend

Rudolf Steiner: Das «pf» sollte recht regsam turnerisch gemacht werden.

Ein Stück, wobei zum Teil auf die Form, zum Teil auf den Inhalt zu achten ist, ist das Folgende:

Aus den «Galgenliedern» von Christian Morgenstern:

Das Gebet

Die Rehlein beten zur Nacht, Hab acht!

Halb neun!

Halb zehn!

Halb elf!

Halb zwölf!

Zwölf!Die Rehlein beten zur Nacht,

Hab acht!

Sie falten die kleinen Zehlein,

die Rehlein.

Rudolf Steiner: Jetzt werden wir unsere Betrachtungen über die Pflanzenwelt fortsetzen.

Es folgen Ausführungen einiger Kursteilnehmer.

Rudolf Steiner macht mehrfache Zwischenbemerkungen dazu: Es wird später einmal solche Schüler geben, die das Pflanzenreich kennenlernen mehr nach wissenschaftlichen Begriffen, die da wären: Moose, Flechten, Algen, Monokotyledonen, Dikotyledonen. Dies systematische Kennenlernen nach wissenschaftlichen Grundsätzen wird manchmal in die Schule hineingetragen. Aber jeder Mensch, der in der Jugend Pflanzen nach wissenschaftlichen Grundsätzen kennenlernt, sollte sie zuerst kennenlernen so, wie wir sie beschreiben, durch Vergleich mit den menschlichen Seeleneigenschaften. Niemand sollte zuerst wissenschaftliche Botanik kennenlernen. Nachher, später kann er dann an das mehr wissenschaftliche Pflanzensystem herankommen. Es ist ein Unterschied, ob wir erst versuchen die Pflanzen zu beschreiben, und nachher wissenschaftlich an sie herankommen, oder umgekehrt. Man verdirbt sehr viel beim Menschen, wenn man ihm gleich wissenschaftliche Botanik beibringt, wenn er nicht zuerst solche Begriffe bekommt, wie wir sie jetzt darzustellen versuchten. Er sollte aus der Seele, aus dem Gedächtnis herausbringen solche allgemein menschlichen Pflanzenbegriffe, wenn er an die wissenschaftliche Systematik herankommt.

Die Pflanzenwelt ist die sichtbar gewordene Seelenwelt der Erde. Die Nelke ist kokett. Die Sonnenblume ist so richtig bäurisch. Die Sonnenblumen lieben so bäurisch zu glänzen. Recht große Blätter von Pflanzen würden seelisch bedeuten: mit nichts fertig werden, lange zu allem brauchen, ungeschickt sein, namentlich nicht fertig werden können. Man glaubt, er ist fertig, er ist aber immer noch dabei. — Das Seelische in den Pflanzenformen suchen!

Wenn der Sommer herankommt, schon wenn der Frühling herankommt, so breitet sich Schlaf über die Erde aus. Der wird immer dichter und dichter; es ist nur ein Räumlich-Ausbreiten. Wenn die Pflanze am meisten sich entfaltet, schläft sie am meisten. Und im Herbst vergeht der Schlaf, da sind die Pflanzen nicht mehr da, da ist der Schlaf nicht mehr über die Erde ausgebreitet. Beim Menschen gehen die Gefühle, Leidenschaften und Affekte und so weiter mit hinein in den Schlaf, aber dadrinnen würden sie aussehen wie die Pflanzen. Was wir an der Seele unsichtbar haben, verborgene Eigenschaften der Menschen, sagen wir Koketterie, wird sichtbar in den Pflanzen. Beim wachenden Menschen sehen wir das nicht, am schlafenden Menschen aber könnte es hellseherisch beobachtet werden. Koketterie: so sieht sie aus, wie eine Nelke. Eine kokette Dame, die würde aus ihrer Nase fortwährend Nelken hervortreiben. Da würde ein langweiliger Mensch riesige Blätter aus seinem ganzen Leibe hervortreiben, wenn Sie ihn sehen könnten. Wenn der Gedanke angeschlagen wird, daß die Erde schläft, muß man auch weitergehen. Man muß festhalten: die Pflanzenwelt wächst im Sommer. Die Erde schläft im Sommer, im Winter wacht sie. Die Pflanzenwelt ist die Seele der Erde. Beim Menschen hört alles auf, was Seelenleben ist, wenn er einschläft; bei der Erde fängt es recht an, wenn sie einschläft. Das Seelische äußert sich am schlafenden Menschen aber nicht. Wie führt man das Kind über diese Schwierigkeit hinweg?

Ein Kursteilnehmer hatte gemeint, die Pflanzen seien als die Träume der Erde anzusehen.

Rudolf Steiner: Aber die Pflanzenwelt des Sommers sind nicht die Träume der Erde. Die Erde schläft im Sommer. Träume können Sie nur das nennen, wie die Pflanzenwelt aussieht im Frühling und im Herbst. Nur in den ersten Anfängen, meinetwegen das Märzveilchen, wenn es noch grün ist, nicht aber mehr, wenn es blüht, und dann die Zeit, wo das Laub wieder abfällt, können Sie mit Träumen vergleichen. Versuchen Sie, von da den Übergang zu gewinnen zu dem wirklichen Begreifen der Pflanze.

Sie müßten zum Beispiel folgendes mit dem Kinde anfangen: «Sieh dir einmal an einen Hahnenfuß, irgendeine Pflanze, die wir ausgraben können aus der Erde, die uns unten Wurzeln zeigt, Stengel, Blätter, Blüten, und dann Staubgefäße, Stempel, um daraus die Frucht zu entwikkeln.» - Solch eine Pflanze führe man dem Kinde wirklich vor.

Dann führe man dem Kinde vor einen Baum und sage ihm: «Sieh einmal, stelle dir neben der Pflanze diesen Baum vor! Wie ist es mit diesem Baum? Ja, er hat da unten auch Wurzeln, allerdings, aber dann ist kein Stengel da, sondern ein Stamm. Dann breitet er erst die Äste aus, und dann ist es so, als ob auf diesen Ästen erst die eigentlichen Pflanzen wüchsen. Denn da sind viele Blätter und Blüten auf den Ästen darauf; da wachsen kleine Pflanzen wie auf den Ästen selber oben darauf. So daß wir tatsächlich, wenn wir wollen, die Wiese so anschauen können: Da wachsen zum Beispiel so gelbe Hahnenfüße über die ganze Wiese hin. Sie ist bedeckt mit einzelnen Pflanzen, die ihre Wurzeln in der Erde haben, und die da wachsen über die ganze Wiese hin. Aber beim Baum ist es, wie wenn man die Wiese genommen hätte, hätte sie hinaufgehoben, hätte sie gebogen, und dann wachsen erst da droben die vielen Blüten. Der Stamm ist ein Stück Erde selbst. Der Baum ist dasselbe wie die Wiese, auf der die Pflanzen wachsen.

Dann gehen wir vom Baum über zum Löwenzahn oder zur Kamille, Da ist etwas Wurzelhaftes in der Erde darinnen; es wächst etwas heraus wie Stengel, Blätter. Aber da ist oben ein Blütenkörbchen, da stehen lauter kleine Blüten nebeneinander. Beim Löwenzahn ist es ja so, daß der da oben ein Körbchen macht, und da hat er lauter kleine Blüten, vollständige Blüten, die da drinnen stecken im Löwenzahn. Jetzt, nicht wahr, haben wir: den Baum, den Korbblütler und die gewöhnliche Pflanze, die Stengelpflanze. Beim Baum ist es so, wie wenn die Pflanzen erst da oben wachsen würden. Beim Korbblütler ist die Blüte da oben; das sind aber keine Blumenblätter, das sind unzählige, vollentwickelte Blumen.

Jetzt denken wir, es wäre die Geschichte gerade so, als ob die Pflanze alles da unten behält in der Erde. Sie will die Wurzeln entfalten, bringt es aber nicht dazu. Sie will Blätter entfalten, bringt es nicht dazu. Nur da oben, dasjenige, was sonst in der Blüte drinnen ist, entfaltet sich: da kommt ein Pilz heraus. Und wenn es zur Not ist und die Wurzel da unten mißglückt und nur Blätter herauskommen: da kommen Farne heraus. Das sind alles verschiedene Formen, aber es sind alles Pflanzen.»

Zeigen Sie dem Kinde den Hahnenfuß, wie der seine Würzelchen ausbreitet, wie der seine fünf gelben gefransten Blütenblätter hat. Dann zeigen Sie ihm den Baum, wie da darauf erst das Pflanzliche wächst; dann Korbblütler, dann den Pilz, dann Farnkraut, nicht sehr wissenschaftlich, sondern so, daß die Kinder die Form im allgemeinen kennen. Dann sagen Sie dem Kinde: «Ja, was glaubst du eigentlich, warum ist denn eigentlich der Pilz ein Pilz geblieben? Warum ist der Baum ein Baum geworden? - Vergleichen wir einmal den Pilz mit dem Baum. Was ist denn da für ein Unterschied? Ist es denn nicht so, als ob die Erde in ihrer Kraft sich herausgedrängt hätte, wie wenn sich ihr Innerstes im Baum herausgedrängt hätte in den äußeren Raum, in die Höhe, um da draußen erst die Blüten und Früchte zu entwickeln? Und beim Pilz hat sie da drinnen behalten, was sonst über die Erde emporwächst, und nur das Alleroberste sind die Pilze. Beim Pilz ist der Baum unter der Erde, er ist nur in den Kräften vorhanden. Der Pilz ist, was sonst ÄAußerstes des Baumes ist. Wenn sich viele, viele Pilze über der Erde ausbreiten, dann ist das so, wie wenn da unten ein Baum wäre, nur ist er in der Erde drinnen. Wenn wir einen Baum sehen, ist es so, wie wenn die Erde sich selbst aufgestemmt, aufgestülpt hätte und ihr Inneres nach außen bringen würde.»

Jetzt kommen Sie schon näher dem, wie die Sache eigentlich ist: «Wenn da die Pilze wachsen, da mit den wachsenden Pilzen, da nimmt die Erde etwas auf, was sie nach außen befördert, wenn sie Bäume wachsen läßt. Wenn die Erde also Pilze wachsen läßt, so behält sie die Kraft des wachsenden Baumes in sich. Wenn die Erde aber Bäume wachsen läßt, dann kehrt sie die wachsende Kraft des Baumes nach außen.»

Jetzt haben Sie etwas, was allerdings, wenn es Sommer wird, nicht in der Erde darinnen ist, sondern herauskommt aus der Erde; und wenn es Winter ist, da geht es hinunter in die Erde. — «Wenn es Sommer ist, da sendet die Erde durch diese Kraft des Baumes ihre eigene Kraft in die Blüten hinein, läßt sie entfalten, und wenn es Winter ist, nimmt sie sie wieder zurück in sich selber. Wo ist eigentlich die Kraft, die im Sommer da außen in den Bäumen kreist - nur klein sich zeigt in dem Veilchen, groß in den Bäumen -, im Winter? Die ist da drunten in der Erde im Winter. Und was tun denn die Bäume, die Korbblütler und dies alles, wenn es tief Winter ist? Da entfalten sie sich dann ja ganz unter der Erde, da sind sie da drinnen in der Erde, da entfalten sie das Seelenleben der Erde. Das haben die alten Leute gewußt. Deshalb haben sie Weihnachten, wo man das Seelenleben sucht, nicht auf den Sommer gesetzt, sondern auf den Winter.

Geradeso wie beim Menschen, wenn er einschläft, sein Seelenleben nach außen geht, und wenn er wacht, nach innen, nach dem Leibe geht, so geschieht es ja bei der Erde auch. Im Sommer, wenn sie schläft, schickt sie ihre safttragende Kraft nach außen. Im Winter nimmt sie sie zurück, wacht auf, indem sie all die verschiedenen Kräfte in sich hat. Denkt, Kinder, wie diese Erde alles empfindet, alles fühlt! Denn dasjenige, was ihr den ganzen Sommer da seht in Blüten und Blättern, was im Sommer da strotzt, wächst, blüht, in den Hahnenfüßchen, den Rosen, den Nelken: im Winter ist es unter der Erde, da fühlt, zürnt, freut sich das, was unter der Erde ist.»

So bekommt man nach und nach den Begriff des unter der Erde im Winter lebenden Lebens. Das ist die Wahrheit! Und das ist gut, wenn man das den Kindern beibringt. Das ist nicht etwas, was die materialistischen Menschen für eine Schwärmerei halten könnten. Aber man geht da zu dem über, was wirklich als das Ganze in dem Pflanzenleben besteht. Die Kinder werden abgeleitet von dem gewöhnlichen In-denPflanzen-Aufgehen in das, was die Säfte im Sommer in der Hitze über die Erde treibt, im Winter wieder zurücknimmt in die Erde hinein, in dieses Aufundabflutende.

Auf diese Weise bekommen Sie dasjenige, was wirkliches Seelenleben der Erde ist, sich spiegelnd in den Pflanzen. Farne, Moose, Pilze entfalten unter der Erde alles das, was ihnen fehlt, nur bleibt es Äthersubstanz, wird nicht physische Substanz. Wenn diese Ätherpflanze über die Erdoberfläche herauskommt, dann verwandelt sie das, was da herausdringt, durch die Wirkung der äußeren Kräfte in diese Rudimente von Blättern, was die Pilze, Moose, Farne sind. Drunten unter einer Moosfläche, oder einer von Pilzen bewachsenen Fläche, ist etwas wie ein Riesenbaum, und wenn die Erde das da unten nicht aufzehren kann, nicht bei sich behalten kann, dann drängt es sich nach außen.

Der Baum ist ein Stückchen der Erde selbst, Stamm und Äste. Da wird nur das, was bei den Pilzen und Farnen noch da drunten ist, herausgehoben. So daß der Baum, wenn er langsam hineingeschoben würde in die Erde, alles ändern würde; wenn man ihn untertauchen ließe, würden aus den Blättern und Blüten werden Farne, Moose, Pilze, und es würde für ihn dann Winter werden. Nur entzieht er sich dem Winterwerden. Er ist dasjenige, was sich etwas dem Winterwerden entzieht. Würde ich aber so einen Pilz oder Farn beim Schopf packen können und immer weiter herausziehen aus der Erde, so daß das, was unten an Äthersubstanz ist, an die Luft käme, so würde ich einen ganzen Baum herausziehen, und was Pilze wären, würden außen Blüten werden und aussehen wie Bäume. Und die einjährigen Pflanzen stehen mitten drinnen. Die Korbblüte ist, nur in einer einzelnen Form, dasjenige, was da dann entsteht. Wenn ich die Korbblüte herunterschicken würde, dann würden sich auch lauter einzelne Blüten entwickeln. Die Korbblüte ist etwas, was man nennen könnte einen zu schnell aufgeschossenen Baum.

So kann auch in der Erde ein Wunsch leben. Die Erde hat das Bedürfnis, den Wunsch ins Schlafleben versinken zu lassen. Das tut sie im Sommer, und der Wunsch steigt auf als Pflanze. Oben wird er dann erst sichtbar, als Wasserlilie. Unten in der Erde lebt er als Wunsch, oben wird er dann Pflanze.

Die Pflanzenwelt ist die sichtbar gewordene Seelenwelt der Erde, und daher mit der Seele des Menschen zu vergleichen. Aber man soll nicht bloß vergleichen, sondern die wirklichen Formen der Pflanzen hineinbekommen. Erst aus dem Gesamtvergleich kann man zu den einzelnen Pflanzen kommen.

Ein leises Schlafen werden Sie vergleichen mit den gewöhnlichen Pflanzen, ein Wachen während des Schlafes mit den Pilzen - wo viele Pilze sind, da ist eine Stelle, wo die Erde wacht während des Sommers -, ein ganz gründliches, tiefes Schlafen mit den Bäumen. Daraus ersehen Sie, daß die Erde nicht so schläft wie der Mensch, sondern daß die Erde an verschiedenen Stellen mal mehr schläft, mehr wacht, mehr schläft, mehr wacht. So auch der Mensch, der ja im Auge und in den übrigen Sinnesorganen gleichzeitig nebeneinander hat Schlafen, Wachen und Träumen.

Aufgabe für morgen: Machen Sie ein Verzeichnis und stellen Sie auf: links ein Register der menschlichen Seeleneigentümlichkeiten, vom Gedanken herunter durch alle seelischen Affekte, Lust-, Unlustgefühle, aktive, heftige Affekte, Zorn, Trauer und so weiter bis zum Willen herunter. Mit dem Plan der menschlichen Seelenwelt können bestimmte Pflanzenformen verglichen werden.

Rechts führen Sie dann an die zugehörigen einzelnen Pflanzengestaltungen, so daß Sie in diesem Glied oben haben die Gedankenpflanzen, unten die Willenspflanzen, in der Mitte alle die übrigen Pflanzen.

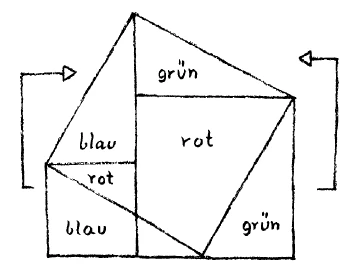

Rudolf Steiner gibt darauf noch eine anschauliche Erläuterung des pythagoreischen Lehrsatzes und verweist auf einen Artikel von Dr. Ernst Müller - in Ostwalds «Annalen der Naturphilosophie»: «Bemerkung über eine erkenntnistheoretische Grundlegung des pythagogoreischen Lehrsatzes.»

In der Zeichnung liegt der rote Teil des Flächeninhaltes der beiden Kathetenquadrate bereits innerhalb des Hypotenusenquadrates. Der übrige Teil dieses Kathetenquadrat-Inhaltes wird durch Verschiebung des blauen und grünen Dreiecks in der Richtung der Pfeile mit den innerhalb des Hypotenusenquadrates liegenden, noch ungedeckten Flächen zur Deckung gebracht.

Rudolf Steiner: Man muß das Ganze aus Pappe ausschneiden, dann wird es erst anschaulich.

Tenth Seminar Discussion

Speech exercises:

Whistling cleverly from bowls

Whistling horses slipping

Caring plows hopping

Penning peaches knottingClever whistling from bowls

Bowl-whistling horses slipping

Waving, caring, plows jumping

Tiptoeing, penning, peaches knotting

Rudolf Steiner: The “pf” should be done quite energetically, like gymnastics.

The following is a piece in which attention should be paid partly to the form and partly to the content:

From the “Gallows Songs” by Christian Morgenstern:

The Prayer

The fawns pray at night, pay attention!

Half past eight!

Half past nine!

Half past ten!

Half past eleven!

Twelve!The little deer pray at night,

Take heed!

They fold their little hands,

the little deer.

Rudolf Steiner: Now we will continue our reflections on the plant world.

The following are comments from some of the course participants.

Rudolf Steiner makes several interjections: Later on, there will be students who will learn about the plant kingdom more in terms of scientific concepts, which would be: mosses, lichens, algae, monocotyledons, dicotyledons. This systematic approach to learning based on scientific principles is sometimes introduced in schools. But anyone who learns about plants according to scientific principles in their youth should first learn about them as we describe them, by comparing them with the characteristics of the human soul. No one should learn scientific botany first. Afterwards, later on, they can then approach the more scientific plant system. There is a difference between first trying to describe the plants and then approaching them scientifically, or vice versa. You spoil a lot in people if you teach them scientific botany right away, if they don't first get concepts like the ones we've tried to describe. They should bring out such general human plant concepts from their soul, from their memory, when they approach the scientific system.

The plant world is the soul world of the earth made visible. The carnation is coquettish. The sunflower is really rustic. Sunflowers love to shine in such a rustic way. Quite large leaves on plants would mean, in spiritual terms: not being able to cope with anything, taking a long time to do everything, being clumsy, namely not being able to cope. One thinks he is finished, but he is still at it. — Seek the spiritual in the forms of plants!

When summer approaches, even when spring approaches, sleep spreads over the earth. It becomes denser and denser; it is only a spatial spread. When the plant unfolds most, it sleeps most. And in autumn, sleep passes, the plants are no longer there, sleep is no longer spread over the earth. In humans, feelings, passions, emotions, and so on go into sleep, but inside they would look like plants. What we have invisibly in our souls, hidden characteristics of humans, let's say coquetry, becomes visible in plants. We don't see this in waking humans, but in sleeping humans it could be observed clairvoyantly. Coquetry: it looks like a carnation. A coquettish lady would constantly sprout carnations from her nose. A boring person would sprout huge leaves from their entire body, if you could see them. When the idea that the earth is asleep is raised, one must also go further. One must remember: the plant world grows in summer. The earth sleeps in summer and wakes in winter. The plant world is the soul of the earth. In humans, everything that is soul life ceases when they fall asleep; in the earth, it begins when it falls asleep. However, the soul does not manifest itself in sleeping humans. How can we help children overcome this difficulty?

One course participant had suggested that plants should be regarded as the dreams of the earth.

Rudolf Steiner: But the plant world of summer is not the dreams of the earth. The earth sleeps in summer. You can only call what the plant world looks like in spring and autumn dreams. Only in the very beginning, for example the March violet when it is still green, but not when it blooms, and then the time when the leaves fall off again, can you compare it to dreams. Try to use this as a transition to a real understanding of the plant.

For example, you should start with the child as follows: “Take a look at a buttercup, any plant that we can dig out of the ground, which shows us its roots, stems, leaves, flowers, and then stamens and pistils, from which the fruit develops.” Show the child such a plant.

Then show the child a tree and say to them: "Look, imagine this tree next to the plant! What about this tree? Yes, it also has roots down there, but then there is no stem, but a trunk. Then it spreads out its branches, and then it is as if the actual plants grow on these branches. For there are many leaves and flowers on the branches; small plants grow on them as if on the branches themselves. So that we can actually, if we want, look at the meadow like this: for example, yellow crowfoot grows all over the meadow. It is covered with individual plants that have their roots in the earth and grow all over the meadow. But with the tree, it is as if one had taken the meadow, lifted it up, bent it, and then the many flowers grow up there. The trunk is a piece of earth itself. The tree is the same as the meadow on which the plants grow.

Then we move from the tree to the dandelion or chamomile. There is something root-like in the earth inside; something grows out of it like stems and leaves. But at the top there is a flower head, with lots of little flowers next to each other. With the dandelion, it is the case that it forms a basket up there, and it has lots of little flowers, complete flowers, which are inside the dandelion. Now, we have: the tree, the composite flower, and the ordinary plant, the stem plant. With the tree, it is as if the plants were growing up there first. With the composite flower, the flower is up there; but these are not petals, they are countless, fully developed flowers.

Now we think it would be just as if the plant kept everything down there in the earth. It wants to unfold its roots, but it can't do it. It wants to unfold its leaves, but it can't do it. Only up there, what is otherwise inside the flower unfolds: a mushroom emerges. And when it is necessary and the root down there fails and only leaves emerge: ferns emerge. These are all different forms, but they are all plants."

Show the child the buttercup, how it spreads its little roots, how it has its five yellow fringed petals. Then show them the tree, how the plant grows on it first; then the composite flower, then the fungus, then the fern, not very scientifically, but in such a way that the children know the form in general. Then say to the child: "Yes, what do you think, why did the mushroom remain a mushroom? Why did the tree become a tree? Let's compare the mushroom with the tree. What is the difference between them? Isn't it as if the earth had pushed itself out in its power, as if its innermost part had pushed itself out into the outer space, into the height, in order to develop the flowers and fruits out there? And in the mushroom, it has kept inside what otherwise grows above the earth, and only the very top are the mushrooms. In the mushroom, the tree is underground; it exists only in its forces. The mushroom is what is otherwise the outermost part of the tree. When many, many mushrooms spread out above the earth, it is as if there were a tree down there, only it is inside the earth. When we see a tree, it is as if the earth had lifted itself up, turned itself inside out, and brought its interior to the outside.

Now you are getting closer to how things actually are: "When mushrooms grow, with the growing mushrooms, the earth takes in something that it transports to the outside when it lets trees grow. So when the earth lets mushrooms grow, it retains the power of the growing tree within itself. But when the earth lets trees grow, it turns the growing power of the tree outward."

Now you have something that, when summer comes, is not inside the earth, but comes out of the earth; and when it is winter, it goes down into the earth. — "When it is summer, the earth sends its own power into the flowers through this power of the tree, allowing them to unfold, and when it is winter, it takes them back into itself. Where is the power that circulates outside in the trees in summer — small in the violet, large in the trees — in winter? It is down there in the earth in winter. And what do the trees, the composite flowers and all the rest do when it is deep winter? They unfold completely underground, they are there inside the earth, they unfold the soul life of the earth. The old people knew this. That is why they did not set Christmas, when one seeks the soul life, in summer, but in winter.

Just as when a human being falls asleep, his soul life goes outward, and when he wakes up, it goes inward, toward the body, so it is with the earth. In summer, when it sleeps, it sends its sap-bearing power outward. In winter, it takes it back, awakens, having all the different powers within itself. Think, children, how this earth perceives everything, feels everything! For what you see there all summer long in blossoms and leaves, what bursts forth, grows, and blooms in the summer, in the buttercups, the roses, the carnations: in winter it is underground, where what is underground feels, rages, and rejoices.

In this way, one gradually gains an understanding of the life that exists underground in winter. That is the truth! And it is good to teach this to children. This is not something that materialistic people might consider fanciful. But one moves on to what really constitutes the whole of plant life. Children are led away from the usual immersion in plants to what the juices drive above the earth in the heat of summer and take back into the earth in winter, in this ebb and flow.

In this way, you get what is really the soul life of the earth, reflected in the plants. Ferns, mosses, and fungi unfold everything they lack underground, but it remains etheric substance and does not become physical substance. When this etheric plant emerges above the earth's surface, it transforms what emerges there, through the action of external forces, into these rudiments of leaves, which are the fungi, mosses, and ferns. Down below, under a surface of moss or an area covered with fungi, there is something like a giant tree, and if the earth cannot consume what is down there, cannot keep it for itself, then it pushes its way out.

The tree is a piece of the earth itself, trunk and branches. Only what is still down there with the fungi and ferns is lifted out. So that if the tree were slowly pushed into the earth, it would change everything; if it were submerged, the leaves and flowers would become ferns, mosses, fungi, and it would then become winter for it. But it avoids becoming winter. It is the one thing that avoids becoming winter. But if I could grab a mushroom or fern by the top and pull it further and further out of the earth, so that what is etheric substance below would come into contact with the air, I would pull out a whole tree, and what would be mushrooms would become flowers on the outside and look like trees. And the annual plants stand in the middle. The basket flower is, in a single form, what then arises. If I were to send the basket flower down, then lots of individual flowers would also develop. The basket flower is something that could be called a tree that has grown too quickly.

In this way, a desire can also live in the earth. The earth has the need to let the desire sink into its sleep life. It does this in summer, and the desire rises as a plant. Above ground, it first becomes visible as a water lily. Below ground, it lives as a desire; above ground, it becomes a plant.

The plant world is the visible manifestation of the soul world of the earth, and can therefore be compared to the soul of man. But one should not merely compare, but rather understand the real forms of the plants. Only from the overall comparison can one arrive at the individual plants.

You will compare a quiet sleep with ordinary plants, waking during sleep with mushrooms – where there are many mushrooms, there is a place where the earth wakes during the summer – and a very thorough, deep sleep with trees. From this you can see that the earth does not sleep like humans, but that in different places the earth sometimes sleeps more, sometimes wakes more, sometimes sleeps more, sometimes wakes more. The same is true of humans, who have sleeping, waking, and dreaming simultaneously side by side in the eye and in the other sense organs.

Task for tomorrow: Make a list and draw up a register of the characteristics of the human soul, starting with thoughts and working down through all the emotions, feelings of pleasure and displeasure, active, intense emotions, anger, sadness, and so on, down to the will. Certain plant forms can be compared with the plan of the human soul world.

On the right, list the corresponding individual plant forms, so that at the top of this section you have the thought plants, at the bottom the will plants, and in the middle all the other plants.

Rudolf Steiner then gives a vivid explanation of the Pythagorean theorem and refers to an article by Dr. Ernst Müller in Ostwald's “Annalen der Naturphilosophie” (Annals of Natural Philosophy): “Remarks on an epistemological foundation of the Pythagorean theorem.”

In the drawing, the red part of the area of the two cathetus squares is already within the hypotenuse square. The remaining part of this cathetus square area is brought into alignment by shifting the blue and green triangles in the direction of the arrows with the areas within the hypotenuse square that are still uncovered.

Rudolf Steiner: You have to cut the whole thing out of cardboard, then it becomes clear.