Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

30 August 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Nine

Speech exercise.

Deprive me not of what, when I give it to you freely, pleases you.

Rudolf Steiner: This sentence is constructed chiefly to show the break in the sense, so that it runs as follows: First the phrase “Deprive me not of what,” and then the phrase “pleases you,” but the latter is interrupted by the other phrase, “when I give it to you freely.” This must be expressed by the way you say it. You must notice that the emphasis you dropped on the word “what” you pick up again at “pleases you.”

Rateless ration

roosted roomily

reason wretched

ruined Roland

royalty rosterName neat Norman on nimble moody mules

Piffling fifer

prefacing feather

phlegma fluting

fairground piercing

Weekly verse from The Calendar of the Soul:

I feel a strange power bearing fruit,

Gaining strength, bestowing me on myself,

I sense the seed ripening

And presentiment weaving, full of Light,

Within me on my selfhood’s power.1Verse for August 25–31 (twenty-first week); see Rudolf Steiner, The Calendar of the Soul, Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, NY, 1988.

RUDOLF STEINER: Now we arrive at the difficult task before us today. Yesterday I asked you to consider how you would prepare the lessons in order to teach the children about the lower and higher plants, making use of some sort of illustration or example. I have shown you how this can be done in the case of animals—with a cuttlefish, a mouse, a horse, and a person—and your botany lessons must be prepared in the same spirit. But let me first say that the correct procedure is to study the animal world before coming to terms with the natural conditions of the plants. In the efforts necessary to characterize the form of your botany lessons—finding whatever examples you can from one plant or another—you will become clear why the animal period must come first.

Perhaps it would be a good idea if we first ask who has already given botany lessons. That person could speak first and the others can follow.

Comment: The plant has something like an instinctive longing for the Sun. The blossoms turn toward the Sun even before it has risen. Point out the difference between the life of desire in animals and people, and the pure effort of the plant to turn toward the Sun. Then give the children a clear idea of how the plant exists between Sun and Earth. At every opportunity mention the relation of the plant to its surroundings, especially the contrast between plants and human beings, and plants and animals. Talk about the outbreathing and in-breathing of the plant. Allow the children to experience how “bad” air is the very thing used by the plant, through the power of the Sun, to build up again what later serves as food for people. When speaking of human dependence on food you can point to the importance of a good harvest, and so on. With regard to the process of growth it should be made clear that each plant, even the leaf, grows only at the base and not at the tip. The actual process of growth is always concealed.

RUDOLF STEINER: What does it actually mean that a leaf only grows at the base? This is also true of our fingernails, and if you take other parts of the human being, the skin, the surfaces of the hands, and the deeper layers, the same thing applies. What actually constitutes growth?

Comment: Growth occurs when dead matter is “pushed out” of what is living.

RUDOLF STEINER: Yes, that’s right. All growth is life being pushed out from inside, and the dying and gradual peeling off of the outside. That is why nothing can ever grow on the outside. There must always be a pushing of substance from within outward, and then a scaling off from the surface. That is the universal law of growth—that is, the connection between growth and matter.

Comment: Actually the leaf dies when it exposes itself to the Sun; it sacrifices itself, as it were, and what happens in the leaf also happens at a higher level in the flower. It dies when it is fertilized. Its only life is what remains hidden within, continuing to develop.

With the lower plants one should point out that there are plants—mushrooms, for example—that are similar to the seeds of the higher plants, and other lower plants resemble more particularly the leaves of the higher plants.

RUDOLF STEINER: Much of what you have said is good, but it would also be good in the course of your description to acquaint your students with the different parts of a single plant, because you will continually have to speak about the parts of the plant—leaf, blossom, and so on. It would therefore be good for the pupil to get to know certain parts of a plant, always following the principle that you have rightly chosen—that is, the study of the plant in relation to Sun and Earth. That will bring some life to your study of the plants; from there you should build the bridge to human beings. You have not yet succeeded in making this connection, because everything you said was more or less utilitarian—how plants are useful to people, for example—and other external comparisons.

There is something else that must be worked out before these lessons can be of real value to the children; after you have made clear the connection between animal and human being, you must also try to show the connection between plant and human being. Most of the children are in their eleventh year when we begin this subject, and at this point the time is ripe to consider what the children have already learned—or rather, we must keep in mind that the children have already learned things in a certain way, which they must now put to good use. Then too you must not forget to give the children the kind of image of the plant’s actual form that they can understand.

Comment: The germinating process should be demonstrated to the children—for example, in the bean. First the bean as a seed and then an embryo in its different stages. We could show the children how the plant changes through the various seasons of the year.

RUDOLF STEINER: This should not really be given to your students until they are fifteen or sixteen years old. If you did take it earlier you would see for yourself that the children who are still in the lower grades cannot yet fully understand the germinating process. It would be premature to develop this germinating process with younger children—your example of the bean and so on. That is foreign to the child’s inner nature.

I only meant to point out to the children the similarity between the young plant and the young animal, and the differences as well. The animal is cared for by its mother, and the plant comes into the world alone. My idea was to treat the subject in a way that would appeal more to the feelings.

RUDOLF STEINER: Even so, this kind of presentation is not suitable for children; you would find that they could not understand it.

Question: Can one compare the different parts of the plant with a human being? The root with the head, for example?

RUDOLF STEINER: As Mr. T. correctly described, you must give plants their place in nature as a whole—Sun, Earth, and so on—and always remember to speak of them in relation to the universe. Then when you give the proper form to your lesson you will find that the children meet what you present with a certain understanding.

Someone described how plants and human beings can be compared—a tree with a person, for example: human trunk = tree trunk; arms and fingers = branches and twigs; head = root. When a person eats, the food goes from above downward, whereas in a tree the nourishment goes from below upward. There is also a difference: whereas people and animals can move around freely and feel pleasure and pain, plants cannot do this. Each type of plant corresponds to some human characteristic, but only externally. An oak is proud, while lichens and mosses are modest and retiring.

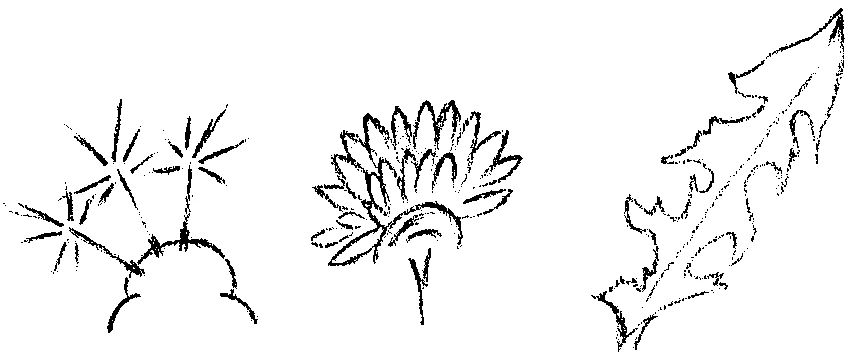

RUDOLF STEINER: There is much in what you say, but no one has tried to give the children an understanding of the plant itself in its various forms. What would it be like if, for example, you perhaps ask, “Haven’t you ever been for a walk during the summer and seen flowers growing in the fields, and parts of them fly away when you blow on them? They have little ‘fans’ that fly away. And you have probably seen these same flowers a little earlier, when summer was not quite so near; then you saw only the yellow leaf shapes at the top of the stem; and even earlier, in the spring, there were only green leaves with sharp jagged edges. But remember, what we see at these three different times is all exactly the same plant! Except that, to begin with, it is mainly a green leaf; later on it is mainly blossom; and still later it is primarily fruit. Those are only the fruits that fly around. And the whole is a dandelion! First it has leaves—green ones; then it presents its blossoms, and after that, it gets its fruit.

“How does all this happen? How does it happen that this dandelion, which you all know, shows itself at one time with nothing but green leaves, another time with flowers, and later with tiny fruits?

“This is how it comes about. When the green leaves grow out of the earth it is not yet the hot part of the year. Warmth does not yet have as much effect. But what is around the green leaves? You know what it is. It is something you only notice when the wind passes by, but it is always there, around you: the air. You know about that because we have already talked about it. It is mainly the air that makes the green leaves sprout, and then, when the air has more warmth in it, when it is hotter, the leaves no longer remain as leaves; the leaves at the top of the stem turn into flowers. But the warmth does not just go to the plant; it also goes down into the earth and then back again. I’m sure that at one time or another you have seen a little piece of tin lying on the ground, and have noticed that the tin first receives the warmth from the Sun and then radiates it out again. That is really what every object does. And so it is also with warmth. When it is streaming downward, before the soil itself has become very warm, it forms the blossom. And when the warmth radiates back again from the earth up to the plant, it is working more to form the fruit. And so the fruit must wait until the autumn.”

This is how you should introduce the organs of the plant, at the same time relating these organs to the conditions of air and heat. You can now go further, and try to elaborate the thoughts that were touched on when we began today, showing the plants in relation to the outer elements. In this way you can also connect morphology, the aspect of the plant’s form, with the external world. Try this.

Someone spoke about plant-teaching.

RUDOLF STEINER: Some of the thoughts you have expressed are excellent, but your primary goal must be to give the children a comprehensive picture of the plant world as a whole: first the lower plants, then those in between, and finally the higher plants. Cut out all the scientific facts and give them a pictorial survey, because this can be tremendously significant in your teaching, and such a method can very well be worked out concerning the plant world.

Several teachers spoke at length on this subject. One of them remarked that “the root serves to feed the plant.”

RUDOLF STEINER: You should avoid the term serves. It’s not that the root “serves” the plant, but that the root is related to the watery life of earth, with the life of juices. It is however not what the plant draws out of the ground that makes up its main nourishment, but rather the carbon from the air.

Children cannot have a direct perception of a metamorphosis theory, but they can understand the relationship between water and root, air and leaves, warmth and blossoms.

It is not good to speak about the plants’ fertilization process too soon—at any rate, not at the age when you begin to teach botany—because children do not yet have a real understanding of the fertilization process. You can describe it, but you’ll find that they do not understand it inwardly.

Related to this is the fact that fertilization in plants does not play as prominent a part as generally assumed in our modernday, abstract, scientific age. You should read Goethe’s beautiful essays, written in the 1820s, where he speaks of pollination and so on. There he defends the theory of metamorphosis over the actual process of fertilization, and strongly protests the way people consider it so terribly important to describe a meadow as a perpetual, continuous “bridal bed!” Goethe strongly disapproved of giving such a prominent place to this process in plants. Metamorphosis was far more important to him than the matter of fertilization. In our present age it is impossible to share Goethe’s belief that fertilization is of secondary importance, and that the plant grows primarily on its own through metamorphosis; even though, according to modern advanced knowledge, you must accept the importance of the fertilization process, it still remains true, however, that we are doing the wrong thing when we give it the prominence that is customary today. We must allow it to retire more into the background, and in its place we must talk about the relationship between the plant and the surrounding world. It is far more important to describe the way air, heat, light, and water work on the plant, than to dwell on the abstract fertilization process, which is so prominent today. I want to really emphasize this; and because this is a very serious matter and particularly important, I would like you to cross this Rubicon, to delve further into the matter, so that you find the proper method of dealing with plants and the right way to teach children about them.

Please note that it is easy enough to ask what similarities there are between animal and humankind; you will discover this from many and diverse aspects. But when you look for similarities between plants and humankind, this external method of comparison quickly falls apart. But let’s ask ourselves: Are we perhaps on the wrong path in looking for relationships of this kind at all?

Mr. R. came closest to where we should begin, but he only touched on it, and he did not work it out any further.

We can now begin with something you yourselves know, but you cannot teach this to a young child. Before we meet again, however, perhaps you can think about how to clothe, in language suited to children, things you know very well yourselves in a more theoretical way.

We cannot just take human beings as we see them in life and compare them with the plant; nevertheless there are certain resemblances. Yesterday I tried to draw the human trunk as a kind of imperfect sphere.2See Practical Advice to Teachers, lecture 7. The other part that belongs to it—which you would get if you completed the sphere—indeed has a certain likeness to the plant when you consider the mutual relationship between plants and human beings. You could even go further and say that if you were to “stuff ” a person (forgive the comparison—you will find the right way of changing it for children) especially in relation to the middle senses, the sense of warmth, the sense of sight, the sense of taste, the sense of smell, then you would get all kinds of plant forms.3See The Foundations of Human Experience, lecture 8. If you simply “stuffed” some soft substance into the human being, it would assume plant forms. The plant world, in a certain sense, is a kind of “negative” of the human being; it is the complement.

In other words, when you fall asleep everything related to your soul passes out of your body; these soul elements (the I and the actual soul) reenter your body when you awaken. You cannot very well compare the plant world with the body that remains lying in your bed; but you can truthfully compare it with the soul itself, which passes in and out. And when you walk through fields or meadows and see plants in all the brightness and radiance of their blossoms, you can certainly ask yourselves: What temperament is revealed here? It is a fiery temperament! The exuberant forces that come to meet you from flowers can be compared to qualities of soul. Or perhaps you walk through the woods and see mushrooms or fungi and ask: What temperament is revealed here? Why are they not growing in the sunlight? These are the phlegmatics, these mushrooms and fungi.

So you see, when you begin to consider the human element of soul, you find relationships with the plant world everywhere, and you must try to work out and develop these things further. You could compare the animal world to the human body, but the plant world can be compared more to the soul, to the part of a human being that enters and “fills out” a person when awaking in the morning. If we could “cast” these soul forms we would have the forms of the plants before us. Moreover, if you could succeed in preserving a person like a mummy, leaving spaces empty by removing all the paths of the blood vessels and nerves, and pouring into these spaces some very soft substance, then you would get all kinds of forms from these hollow shapes in the human body.

The plant world is related to human beings as I have just shown, and you must try to make it clear to the children that the roots are more closely related to human thoughts, and the flowers more related to feelings—even to passions and emotions. And so it happens that the most perfect plants—the higher, flowering plants—have the least animal nature within them; the mushrooms and the lowest types of plant are most closely akin to animals, and it is particularly these plants that can be compared least to the human soul.

You can now develop this idea of beginning with the soul element and looking for the characteristics of the plants, and you can extend it to all the varieties of the plant world. You can characterize the plants by saying that some develop more of the fruit nature—the mushrooms, for example—and others more of the leaf nature, such as ferns and the lower plants, and the palms, too, with their gigantic leaves. These organs, however, are developed differently. A cactus is a cactus because of the rampant growth of its leaves; its blossom and fruit are merely interspersed among the luxuriant leaves.

Try now to translate the thought I indicated to you into language suited for children. Exert your fantasy so that by next time you can give us a vivid description of the plant world all over the Earth, showing it as something that shoots forth into herb and flower, like the soul of the Earth, the visible soul, the soul made manifest.

And show how the different regions of Earth—the warm zone, the temperate zone, and the cold zone—each has its prevailing vegetation, just as in a human being each of the various spheres of the senses within the soul make a contribution. Try to make it clear to yourself how one whole sphere of vegetation can be compared with the world of sound that a person receives into the soul, another with the world of light, yet another with the world of smell, and so on.

Then try to bring some fruitful thoughts about how to distinguish between annuals and perennials, or between the flora of western, central, and eastern European countries. Another fruitful thought that you could come to is about how the whole Earth is actually asleep in summer and awake in winter.

You see, when you work in this way you awaken in the child a real feeling for intimacy of soul and for the truth of the spirit. Later, when the children are grown, they will much more easily understand how senseless it is to believe that human existence, as far as the soul is concerned, ceases every evening and begins again each morning. Thus they will see, when you have shown them, that the relationship between the human body and soul can be compared to the interrelationship between the human world and the plant world. How then does the Earth affect the plant? Just as the human body works, so when you come to the plant world you have to compare the human body with the Earth—and with something else, as you will discover for yourselves.

I only wanted to give you certain suggestions so that you, yourselves, using all your best powers of invention, can discover even more before next time. You will then see that you greatly benefit the children when you do not give them external comparisons, but those belonging to the inner life.

Neunte Seminarbesprechung

Sprechübungen:

Nimm mir nicht, was, wenn ich freiwillig dir es reiche, dich beglückt.

Rudolf Steiner: Der Spruch ist mehr gemeint für die Sinnabteilung, sodaß Sie folgendes haben: Erst einen Satz, der kurz ist: «Nimm mir nicht», und dann den Satz: «was dich beglückt», der aber unterbrochen ist durch den anderen: «wenn ich freiwillig dir es reiche». Es ist die Absicht diese, daß das im Sprechen zur Geltung kommt. Man muß merken, Sie nehmen denselben Betonungscharakter wiederum auf, den Sie bei «was» ausgelassen haben und bei «dich» wiederum einsetzen lassen.

Redlich ratsam

Rüstet rühmlich

Riesig rächend

Ruhig rollend

Reuige Rosse

Nimm nicht Nonnen in nimmermüde Mühlen

Pfiffig pfeifen

Pfäffische Pferde

Pflegend Pflüge

Pferchend Pfirsiche

Wochenspruch (letzte August-Woche) aus dem «Seelenkalender»:

Ich fühle fruchtend fremde Macht

Sich stärkend mir mich selbst verleihn,

Den Keim empfind ich reifend

Und Ahnung lichtvoll weben

Im Innern an der Selbstheit Macht.

Rudolf Steiner: Jetzt kommen wir zu unserer heutigen schweren Aufgabe.

Ich habe Sie gestern gebeten, darüber nachzudenken, wie Sie die Unterrichtsstunden einrichten wollen, in denen Sie die niederen und die höheren Pflanzen in irgendeinem Beispiel mit den Kindern durchnehmen wollten, so aus demselben Geiste heraus, wie ich es Ihnen gezeigt habe bei Tintenfisch, Maus, Pferd und Mensch, wie man das für die Tiere machen muß. Vorausschicken will ich nur, daß ein sachgemäßer Unterricht die Betrachtung über die Tiere vorausgehen lassen muß der Behandlung der naturgeschichtlichen Verhältnisse an den Pflanzen. Das wird sich nun ergeben, warum das so ist, indem Sie sich anstrengen werden, soweit Sie Beispiele geben können an der einen oder anderen Pflanze, die Pflanzenunterrichtsstunde zu charakterisieren.

Nun wird es ja vielleicht gut sein, wenn wir zuerst fragen: Wer hat schon Pflanzenunterricht gegeben? Der könnte zunächst einmal anfangen. Darnach könnten sich die anderen richten.

T.: Die Pflanze hat ein triebmäßiges Sehnen nach der Sonne. Die Blüten wenden sich der Sonne zu, auch wenn sie noch nicht aufgegangen ist. Aufmerksam machen auf den Unterschied zwischen dem Wunschleben des Tieres und des Menschen, und dem reinen Streben der Pflanze, sich der Sonne zuzuwenden. Dann dem Kinde den Begriff des Eingespanntselns der Pflanze zwischen Sonne und Erde klarmachen. Bei jeder Gelegenheit die Beziehung zwischen der Pflanze und ihrer Umgebung erwähnen, besonders die Gegensätzlichkeit zwischen Pflanze und Mensch, Pflanze und Tier. Das Aus- und Einatmen der Pflanze besprechen. Das Kind fühlen lassen, daß die Pflanze gerade aus der «verdorbenen» Luft durch die Kraft der Sonne das wieder aufbaut, was nachher dem Menschen zur Nahrung dient. Wenn man die Abhängigkeit des Menschen bezüglich der Nahrung bespricht, kann man hinweisen auf die Wichtigkeit einer guten Ernte und so weiter. Über den Wachstumsprozeß: Jede Pflanze, selbst das Blatt, wächst nur am Grunde, nicht aber an der Spitze. Der eigentliche Wachstumsprozeß ist stets verhüllt.

Rudolf Steiner: Was heißt das, ein Blatt wächst nur am Grunde? Bei den Fingernägeln des Menschen ist es ebenso. Und wenn Sie etwas anderes am Menschen nehmen, die Haut, die Handoberfläche und tie fer gelegene Teile, da ist es ebenso. Worin besteht denn eigentlich das Wachsen?

T.: Eigentlich in einem Herausschieben des Toten aus dem Lebenden.

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, so ist es. Alles Wachsen ist ein Herausschieben des Lebendigen aus dem Inneren und ein Absterben und allmähliches Abschälen des Äußeren. Daher kann niemals außen etwas anwachsen. Es muß sich immer das Substantielle von innen nach außen vorschieben und an der Oberfläche abschuppen. Das ist das allgemeine Gesetz des Wachstums, das heißt des Zusammenhanges des Wachstums mit der Materie.

T.: Was am Blatt geschieht, daß eigentlich das Blatt stirbt, wenn es sich der Sonne aussetzt, gewissermaßen sich opfert, das geschieht erhöht in der Blüte. Sie stirbt, wenn sie befruchtet ist. Es bleibt bloß das im Innern Verborgene leben, was sich weiterentwickelt. - Bei den niederen Pflanzen muß man aufmerksam machen darauf, daß es Pflanzen gibt wie zum Beispiel die Pilze, die Ähnlichkeit haben mit dem Samen der höheren Pflanzen, daß andere niedere Pflanzen vor allem Ähnlichkeit haben mit den Blättern der höheren Pflanzen.

Rudolf Steiner: Sie haben ja manches Gute gesagt, aber es wäre doch zu wünschen, daß der Zögling im Verlaufe einer solchen Darstellung bekannt würde mit den Gliedern einer einzelnen Pflanze. Sie sind ja auch genötigt, fortwährend von den Gliedern der Pflanze zu sprechen, vom Blatt, Blüte und so weiter. Es wäre nun gut, wenn der Zögling bekannt würde mit gewissen Gliedern der Pflanze, nach dem Prinzip, das Sie ja richtig gewählt haben: Die Pflanze an Sonne und Erde betrachten. Da muß etwas Leben hineinkommen in die Pflanzenbetrachtung, und von da aus muß dann die Brücke geschlagen werden zum Menschen. Es ist Ihnen noch nicht gelungen, diese zu schlagen, denn das, was Sie gesagt haben, sind mehr oder weniger Utilitätsgeschichten, wie die Pflanzen dem Menschen nützlich sind, oder auch äußere Vergleiche. Was da herausgearbeitet werden muß, damit wirklich gerade das Kind sehr viel hat von einer solchen Betrachtung, das ist: Man wird versuchen müssen, nachdem man die Beziehung des Tieres zum Menschen klargelegt hat, doch auch die Beziehung der Pflanze zum Menschen klarzumachen. Denn es ist ja wohl zumeist im elften Jahr, wo wir mit so etwas einzusetzen haben, wo man also berücksichtigen kann, was das Kind schon gelernt hat, oder besser gesagt, daß das Kind die Dinge in irgendeiner Weise schon gelernt hat, die es da verwerten muß. — Nicht versäumt darf werden, die Pflanze selbst, nach ihrer Gestaltung, an die Fassungskraft des Kindes heranzubringen.

M.: Man zeigt den Kindern den Keimprozef, etwa an der Bohne. Zunächst die Bohne als Samenkorn, dann den Keim in verschiedenen Stadien. Man zeigt die Verschiedenheit der Pflanze durch die Jahreszeiten hindurch.

Rudolf Steiner: Das ist etwas, was eigentlich rationell erst vorgenommen werden sollte mit Zöglingen, die schon das vierzehnte, fünfzehnte Jahr überschritten haben. Wenn Sie das machen würden, so würden Sie sich überzeugen, daß die Kinder, die noch in der Volksschule sind, den Keimvorgang noch nicht wirklich verstehen können. Das würde also verfrüht sein, den Keimvorgang vor den jüngeren Kindern zu entwickeln, die Geschichte mit der Bohne und so weiter. Innerlich ist das den Kindern sehr fremd.

M.: Ich wollte auch nur auf die Ähnlichkeit aufmerksam machen zwischen der jungen Pflanze und dem jungen Tier, und auch auf die Unterschiede. Das Tier wird von der Mutter versorgt, die Pflanze wird allein in die Welt geschickt. Mehr gemüthaft wollte ich die Sache vorbringen.

Rudolf Steiner: Auch diese gemüthaften Vorstellungen taugen nicht für das Kind. Sie würden kein Verständnis finden bei dem Kinde.

M.: Kann man Teile der Pflanze mit dem Menschen vergleichen? Zum Beispiel die Wurzel mit dem Kopf und so weiter?

Rudolf Steiner: Sie müssen die Pflanzen, wie es richtig war bei Herrn Ts. Ausführung, in die ganze Natur, Sonne, Erde und so weiter hineinstellen und müssen die Pflanze gleichsam im Zusammenhang mit der Welt lassen. Dann bekommen Sie eine Betrachtung heraus, die, wenn sie richtig gestaltet wird, auch schon beim Kinde auf ein gewisses Verständnis trifft.

R. beschreibt, wie man Pflanze und Mensch vergleichen kann, zum Beispiel den Baum mit dem Menschen: Rumpf = Stamm; Gliedmaßen = Äste und Zweige; Kopf = Wurzelwerk. Wenn wir essen, geht die Nahrung beim Menschen von oben nach unten, beim Baum von unten nach oben. Verschiedenheit: Mensch und Tier können sich frei bewegen, können Lust und Leid empfinden, die Pflanze nicht. Jede Pflanzenart entspricht, aber nur äußerlich, einer menschlichen Charaktereigentümlichkeit, Eiche = Stolz und so weiter, Flechten und Moose sind bescheiden.

Rudolf Steiner: Damit ist wieder vieles gesagt, aber es ist natürlich noch immer nicht der Versuch gemacht worden, die Pflanze selbst, ihren Formen nach, an das Kind heranzubringen. Wie wäre es, wenn Sie zum Beispiel folgendes machen würden. Sie würden etwa fragen: «Seid ihr noch niemals spazierengegangen gegen den Sommer hin? Habt ihr da nicht auf den Feldern solche Blumen stehen sehen, wenn man sie anbläst, fliegen von ihnen Teile fort. Sie haben so kleine Fächerchen, die fliegen dann fort. Dann habt ihr diese Blumen doch auch etwas früher gesehen, wenn wir noch nicht so nahe am Sommer waren. Da schaut das so aus, daß oben nur die gelben blattartigen Gebilde waren. Und noch früher, mehr dem Frühling zu, da waren nur die grünen Blätter da, die sehr spitz gekerbt sind.

Das, was wir da betrachten, zu drei verschiedenen Zeiten, das ist immer dieselbe Pflanze! Nur ist sie zuerst hauptsächlich grünes Blatt, nachher ist sie hauptsächlich Blüte, und nachher ist sie hauptsächlich Frucht. Denn das sind nur die Früchte, die da herumfliegen. Das Ganze ist ein Löwenzahn! Zuerst bekommt er Blätter, die grünen; dann treibt er Blüten und nachher kriegt er seine Früchte. Wodurch geschieht denn das alles? Wie kommt es denn, daß dieser Löwenzahn, den ihr kennt, sich einmal zeigt bloß mit grünen Blättern, dann mit Blüten und nachher mit Früchtchen?

Das kommt davon her: Wenn die grünen Blätter aus der Erde herauswachsen, da ist es noch nicht so heiß im Jahr. Da wirkt noch nicht so stark die Wärme. Aber um die grünen Blätter herum, was ist denn da? Ihr wißt es. Es ist etwas, was ihr nur spürt, wenn der Wind geht, aber immer ist es um euch herum: die Luft. Ihr kennt das ja, wir haben schon davon gesprochen. Die Luft bringt hauptsächlich die grünen Blätter hervor, und wenn dann die Luft mehr durchzogen ist von der Wärme, wenn es wärmer wird, dann bleiben die Blätter nicht mehr Blätter, dann werden die obersten Blätter zur Blüte. Aber die Wärme geht ja nicht bloß zur Pflanze hin, sondern sie geht auch zu der Erde und dann wiederum zurück. Ihr seid gewiß schon einmal da gewesen, wo ein Stückchen Blech lag. Da werdet ihr bemerkt haben, daß das Blech die Wärme erst empfängt von der Sonne und dann sie wiederum ausstrahlt. Das tut eigentlich jeder Gegenstand. Und so macht es die Wärme: wenn sie noch herunterstrahlt, wenn die Erde noch nicht gar so warm geworden ist, da bildet sie die Blüte. Und wenn die Wärme wieder zurückstrahlt von der Erde zu der Pflanze herauf, dann bildet sie erst die Frucht. Daher muß die Frucht warten bis zum Herbst.»

Wenn Sie es so machen, dann bringen Sie die Organe, aber Sie bringen diese Organe zu gleicher Zeit in Beziehung zu dem, was Luft- und Wärmeverhältnisse sind. Nun können Sie in einer solchen Betrachtung dann weitergehen, und Sie können auf diese Weise versuchen, den zuallererst heute angeschlagenen Gedanken weiter auszuführen, die Pflanzen in Beziehung zu bringen zu den äußeren Elementen. Dadurch kommen Sie dazu, das Morphologische, das Gestaltliche der Pflanzen auch mit der Außenwelt etwas in Berührung zu bringen. Versuchen Sie das einmal zu machen.

D. spricht über den Pflanzenunterricht.

Rudolf Steiner: Da ist viel Treffliches gesagt worden, aber man muß darauf hinarbeiten, daß die Kinder eine Übersicht bekommen über die Pflanzen: erst die niederen, dann mittlere, dann höhere. Das Gelehrte kann ganz wegbleiben. Eine Übersicht über die Pflanzen zu schaffen, das ist nicht leicht, aber das kann etwas sehr Bedeutsames werden für den Unterricht, und das kann an der Pflanzenwelt herausentwickelt werden.

Mehrere Lehrer geben längere Ausführungen. Dabei wird einmal gesagt, «die Wurzel dient zur Ernährung der Pflanze».

Rudolf Steiner: Den Ausdruck «dienen» sollte man vermeiden. Nicht die Wurzel «dient» zur Ernährung, sondern die Wurzel hängt zusammen mit dem Wasserleben der Erde, mit dem Säfteleben, während sich an der Luft die Blätter entwickeln. Aber was die Pflanze aus dem Boden saugt, ist nicht die hauptsächlichste Nahrung der Pflanze, sondern das ist der Kohlenstoff von oben, aus der Luft. Die Pflanze nimmt Nahrung von oben her auf.

Den Metamorphosengedanken werden Kinder unmittelbar nicht aufnehmen, aber den Zusammenhang zwischen Wasser und Wurzel, Luft und Blättern, Wärme und Blüten.

Es ist nicht gut, den Befruchtungsvorgang bei der Pflanze zu früh zu besprechen; jedenfalls nicht in dem Alter, wo man anfängt, Botanik zu treiben. Aus dem Grunde nicht, weil das Kind diesem Befruchtungsvorgang nicht wirklich ein Verständnis entgegenbringt. Man kann ihn schildern, aber man findet beim Kinde dafür kein inneres Verständnis.

Das hängt damit zusammen, daß der Befruchtungsvorgang bei der Pflanze gar nicht einmal etwas so furchtbar Hervorragendes ist, als es von der heutigen, abstrakten naturwissenschaftlichen Zeit angenommen wird. Lesen Sie nur einmal die schönen Aufsätze Goethes aus den zwanziger Jahren des 19. Jahrhunderts, wo er über die «Verstäubung» und so weiter geschrieben hat, wo er die Metamorphose verteidigt gegen den eigentlichen Befruchtungsvorgang, und wo er weidlich schimpft darüber, daß die Menschen es für so furchtbar wichtig halten, die Fluren eigentlich als fortwährendes, kontinuierliches Hochzeitsbett zu schildern. Das widerstrebte Goethe, daß man den Befruchtungsvorgang zu sehr in den Vordergrund stellte bei der Pflanze. Da ist die Metamorphose viel wichtiger als der Befruchtungsvorgang. Wenn man auch heute nicht mehr den Glauben Goethes teilen kann, daß eigentlich die Befruchtung etwas Nebensächliches ist und die Pflanze hauptsächlich durch Metamorphose, durch sich selbst wächst, wenn auch heute nach den fortgeschrittenen Erkenntnissen der Befruchtungsvorgang als wichtig angesehen werden muß, so bleibt doch dieses bestehen, daß wir eigentlich schon unrecht tun, wenn wir den Befruchtungsvorgang bei der Pflanze so sehr hervorkehren, wie wir es heute tun. Wir müssen ihn mehr zurücktreten lassen und müssen an diese Stelle die Beziehungen der Pflanze zur Umwelt setzen. Es ist viel wichtiger, zu schildern, wie Luft und Wärme und Licht und Wasser an der Pflanze wirken als diesen abstrakten Befruchtungsvorgang, der heute so sehr in den Vordergrund gestellt wird. Das möchte ich ganz besonders betonen. Und ich möchte, weil dieses wirklich eine Crux ist und von besonderer Wichtigkeit, daß Sie über diesen Rubikon kommen und weiterschürfen nach dieser Richtung: Suchen Sie die richtige Methodik, die richtige Behandlungsweise der Pflanzen.

Ich mache Sie darauf aufmerksam, daß Sie leicht fragen können: Welches sind die Ähnlichkeiten des Tieres mit dem Menschen? Sie werden mannigfaltige Ansichten finden. Aber die äußere Vergleichsmerhode versagt sehr bald, wenn man sucht nach Ähnlichkeiten der Pflanze mit dem Menschen. Aber man kann sich doch auch fragen: Suchen wir nicht vielleicht bloß falsch, wenn wir solche Vergleiche suchen?

Am nächsten kam dem, wovon hier ausgegangen werden sollte, das, was Herr R. berührt, aber dann fallengelassen und nicht weiter ausgeführt hat.

Wir können jetzt ausgehen von etwas, was Sie ja wissen, was Sie aber dem Kinde im kindlichen Alter nicht beibringen können. Aber Sie können vielleicht bis zu unserer nächsten Zusammenkunft nachdenken darüber, wie Sie das in kindlich-verständliche Worte kleiden können, was Sie mehr theoretisch sehr gut wissen können.

Also, nicht wahr, unmittelbar vergleichen können wir den Menschen, so wie er uns entgegentritt, nicht mit der Pflanze, aber es gibt gewisse Ähnlichkeiten. Ich habe gestern versucht, den menschlichen Rumpf aufzuzeichnen wie eine Art unvollkommene Kugel. Das, was dazugehört, was man da bekommen würde, wenn man die Kugel ergänzte, das hat nämlich so eine gewisse Ähnlichkeit mit der Pflanze im Wechselverhältnis mit dem Menschen. Ja, man könnte noch weitergehen und könnte sagen: Wenn Sie, namentlich für die mittleren Sinne, für den Wärmesinn, den Sehsinn, den Geschmackssinn, den Geruchssinn, den Menschen - verzeihen Sie den Vergleich! Sie werden ihn ins Kindliche umsetzen müssen — «ausstopfen», so würden Sie allerlei Pflanzenformen bekommen. Einfach indem Sie ein weiches Material in den Menschen hineinstopfen, würde das von selbst Pflanzenformen annehmen. Die Pflanzenwelt ist in gewissem Sinne eine Art Negativ für den Menschen: es ist das die Ergänzung.

Mit anderen Worten: Wenn Sie einschlafen, geht Ihr eigentlich Seelisches aus dem Leibe heraus; wenn Sie aufwachen, geht Ihr Seelisches, Ich und eigentliche Seele, wiederum in den Leib hinein. Mit diesem Leibe, der im Bette liegen bleibt, können Sie nicht gut die Pflanzenwelt vergleichen. Wohl aber können Sie die Pflanzenwelt vergleichen mit der Seele selbst, die hinaus- und hereingeht. Und Sie können ganz gut, wenn Sie über die Felder und Wiesen gehen und sehen die durch ihre Blüten leuchtende Pflanze, sich fragen: Was ist das für eine Temperament, das da herauskommt? Das ist feurig! — Mit seelischen Eigenschaften können Sie diese strotzenden Kräfte, die Ihnen aus den Blüten entgegenkommen, vergleichen. - Oder Sie gehen durch den Wald und sehen Schwämme, Pilze, und fragen sich: Was ist das für ein Temperament, das da herauskommt? Warum ist das nicht an der Sonne? Das sind die Phlegmatiker, diese Pilze.

Also wenn Sie zu dem Seelischen übergehen, finden Sie überall Vergleichsmomente mit der Pflanzenwelt. Versuchen Sie die nur auszubilden! Während Sie die Tierwelt mehr vergleichen müssen mit der Leiblichkeit des Menschen, müssen Sie die Pflanzenwelt mehr vergleichen mit dem Seelischen des Menschen, mit dem, was den Menschen «ausstopft», und zwar als Seele ausstopft, wenn er am Morgen aufwacht. Die Pflanzenwelt ergänzt den Menschen, wie seine Seele ihn ergänzt. Würden wir die Formen ausstopfen, so würden wir die Pflanzenformen bekommen. Sie würden auch sehen, wenn Sie das zustande brächten, den Menschen zu konservieren wie eine Mumie, und beim Herausnehmen nur alle Blutgefäßbahnen, alle Nervenbahnen leer ließen, und würden da hineingießen einen sehr weichen Stoff, dann würden Sie alle möglichen Formen bekommen durch die Hohlformen des Menschen.

Die Pflanzenwelt steht zum Menschen so, wie ich Ihnen eben ausgeführt habe, und Sie müssen versuchen, den Kindern klarzumachen, wie die Wurzeln mehr verwandt sind mit den menschlichen Gedanken, die Blüten mehr mit den menschlichen Gefühlen, ja schon mit den Affekten, den Emotionen.

Daher ist es auch, daß die vollkommensten Pflanzen, die höheren Blütenpflanzen, am wenigsten Tierisches haben. Am meisten Tierisches haben die Pilze und die niedrigsten Pflanzen, die man auch am wenigsten mit der menschlichen Seele vergleichen könnte.

Also arbeiten Sie darauf hin, daß Sie jetzt diesen Gedanken, von dem Seelischen auszugehen und die pflanzlichen Charaktere zu suchen, über die verschiedensten Pflanzen hin ausdehnen. Dadurch charakterisieren Sie ja die Pflanzen, daß die einen mehr ausbilden den Fruchtcharakter: die Pilze und so weiter; die anderen mehr den Blattcharakter: die Farne, die niederen Pflanzen; auch die Palmen haben ja ihre mächtigen Blätter. Nur sind diese Organe in verschiedener Weise ausgebildet. Ein Kaktus ist dadurch ein Kaktus, daß die Blätter wuchern in ihrem Wachstum; ihre Blüte und Frucht ist ja nur etwas, was da eingestreut ist in die wuchernden Blätter.

Also versuchen Sie, den Gedanken, den ich Ihnen andeutete, so recht ins Kindliche zu übersetzen. Strengen Sie Ihre Phantasie an, daß Sie bis zum nächsten Mal die Pflanzenwelt über die Erde hin ganz lebendig schildern können wie etwas, was wie die Seele der Erde ins Kraut, ins Blühen schießt, die sichtbare, die offenbar werdende Seele.

Und verwenden Sie die verschiedenen Gegenden der Erde, warme Zone, gemäßigte Zone, kalte Zone, nach dem vorwiegenden Pflanzenwachstum, so wie im Menschen die verschiedenen Sinnesgebiete in seiner Seele ihre Beiträge liefern. Versuchen Sie sich klarzumachen, wie eine ganze Vegetation verglichen werden kann mit der Tonwelt, die der Mensch aufnimmt in seine Seele. Wie eine andere Vegetation verglichen werden kann mit der Lichtwelt, eine andere mit der Geruchswelt und so weiter.

Dann machen Sie den Gedanken fruchtbar, wodurch Sie herauskriegen den Unterschied zwischen einjährigen und mehrjährigen Pflanzen, zwischen westlicher, mitteleuropäischer, osteuropäischer Pflanzenwelt. Machen Sie den Gedanken fruchtbar, daß eigentlich im Sommer die ganze Erde schläft und im Winter wacht.

Sehen Sie, wenn Sie so etwas tun, werden Sie viel Sinn im Kinde erwecken für Sinnigkeit und für Geistigkeit. Das Kind wird später viel mehr begreifen, wenn es einmal ein ausgewachsener Mensch ist, wie unsinnig es ist, zu glauben, daß der Mensch seiner Seele nach am Abend aufhört zu sein, und morgens wieder anfängt zu sein, wenn man ihm das Entsprechen von Leib und Seele beim Menschen verglichen haben wird mit dem, was sich ergibt als Wechselverhältnis zwischen der Menschenwelt und der Pflanzenwelt ebenso wie zwischen Leib und Seele. Wie wirkt denn die Erde auf die Pflanze? Die Erde wirkt auf die Pflanze, wie eben der menschliche Leib wirkt auf die Seele. Die Pflanzenwelt ist überall das Umgekehrte zum Menschen, so daß Sie, wenn Sie an die Pflanzenwelt kommen, den menschlichen Leib mit der Erde — und noch mit etwas anderem, da werden Sie selbst darauf kommen vergleichen müssen. Ich wollte nur Andeutungen geben, damit Sie dann möglichst erfinderisch auf noch mehr kommen bis zum nächsten Mal. Dann werden Sie sehen, daß Sie den Kindern sehr viel Gutes tun, wenn Sie ihnen nicht äußerliche Vergleiche beibringen, sondern innerliche.

Ninth Seminar Discussion

Speech exercises:

Do not take from me what, if I voluntarily give it to you, makes you happy.

Rudolf Steiner: The saying is meant more for the sense department, so that you have the following: First a short sentence: “Do not take from me,” and then the sentence: “what makes you happy,” which is interrupted by the other: “if I voluntarily give it to you.” The intention is that this should be emphasized in speech. You must note that you take up the same emphasis again that you omitted in ‘what’ and use again in “you.”

Honestly advisable

Equips praiseworthy

Huge avenging

Rolling calmly

Repentant steeds

Do not take nuns into tireless mills

Whistling smartly

Priestly horses

Caring plows

Penning peaches

Weekly saying (last week of August) from the “Seelenkalender” (Soul Calendar):

I feel a fruitful foreign power

Strengthening me, lending itself to me,

I feel the seed ripening

And weaving a luminous inkling

Inside, at the power of selfhood.

Rudolf Steiner: Now we come to our difficult task for today.

Yesterday I asked you to think about how you want to organize your lessons in which you want to go through the lower and higher plants with the children using some example, in the same spirit as I showed you with the squid, mouse, horse, and human, how to do this for animals. I would just like to say in advance that proper teaching must precede the study of natural history in plants with the observation of animals. The reason for this will become clear as you strive to characterize the plant lesson with examples from one plant or another, as far as you are able.

Now, it might be a good idea to first ask: Who has already taught a plant lesson? That person could start. The others could then follow suit.

T.: Plants have an instinctive longing for the sun. Flowers turn toward the sun even before it has risen. Draw attention to the difference between the desire life of animals and humans and the pure striving of plants to turn toward the sun. Then explain to the children the concept of plants being caught between the sun and the earth. Mention the relationship between the plant and its environment at every opportunity, especially the contrast between plants and humans, plants and animals. Discuss the plant's exhalation and inhalation. Let the child feel that the plant uses the power of the sun to rebuild what is “spoiled” in the air, which then serves as food for humans. When discussing human dependence on food, point out the importance of a good harvest and so on. About the growth process: Every plant, even the leaf, grows only at the base, not at the tip. The actual growth process is always hidden.

Rudolf Steiner: What does it mean that a leaf only grows at the base? It is the same with human fingernails. And if you take something else in humans, the skin, the surface of the hand and deeper parts, it is the same. What does growth actually consist of?

T.: Actually, it consists of pushing out the dead from the living.

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, that's right. All growth is a pushing out of the living from within and a dying off and gradual peeling away of the outer. Therefore, nothing can ever grow on the outside. The substance must always push itself outwards from within and peel off at the surface. That is the general law of growth, that is, the connection between growth and matter.

T.: What happens to the leaf, that the leaf actually dies when it is exposed to the sun, sacrifices itself in a sense, happens in an elevated form in the flower. It dies when it is fertilized. Only what is hidden inside remains alive and continues to develop. In the case of lower plants, it should be noted that there are plants, such as fungi, that resemble the seeds of higher plants, while other lower plants resemble the leaves of higher plants.

Rudolf Steiner: You have said many good things, but it would be desirable for the pupil to become familiar with the parts of a single plant in the course of such a presentation. You are also compelled to talk constantly about the parts of the plant, the leaf, the flower, and so on. It would be good if the pupil became familiar with certain parts of the plant, according to the principle you have correctly chosen: to observe the plant in relation to the sun and the earth. Something of life must enter into the observation of plants, and from there a bridge must be built to the human being. You have not yet succeeded in building this bridge, because what you have said are more or less stories of utility, how plants are useful to humans, or even external comparisons. What needs to be worked out so that the child really benefits greatly from such an observation is this: After clarifying the relationship between animals and humans, we must also try to clarify the relationship between plants and humans. For it is usually in the eleventh year that we have to deal with such things, when we can take into account what the child has already learned, or rather, that the child has already learned things in some way that it must now utilize. — It is important not to neglect to introduce the plant itself, according to its form, to the child's capacity for understanding.

M.: The germination process is shown to the children, for example using beans. First the bean as a seed, then the sprout in various stages. The diversity of the plant throughout the seasons is shown.

Rudolf Steiner: This is something that should really only be done with pupils who are already over fourteen or fifteen years old. If you did that, you would see that children who are still in elementary school cannot really understand the germination process yet. So it would be premature to develop the germination process in front of younger children, the story with the bean and so on. Internally, this is very foreign to children.

M.: I just wanted to point out the similarity between the young plant and the young animal, and also the differences. The animal is cared for by its mother, the plant is sent out into the world alone. I wanted to present the matter in a more emotional way.

Rudolf Steiner: These mental images are also not suitable for children. They would not be understood by children.

M.: Can parts of the plant be compared to humans? For example, the root to the head and so on?

Rudolf Steiner: As Mr. Ts. correctly explained, you must place plants in the context of nature as a whole, the sun, the earth, and so on, and you must leave the plant in connection with the world, as it were. Then you will arrive at a view which, if presented correctly, will be understood to a certain extent even by children.

R. describes how plants and humans can be compared, for example, trees and humans: torso = trunk; limbs = branches and twigs; head = root system. When we eat, food goes from top to bottom in humans, but from bottom to top in trees. Difference: humans and animals can move freely and feel pleasure and pain, but plants cannot. Each plant species corresponds, but only externally, to a human character trait, oak = pride and so on, lichens and mosses are modest.

Rudolf Steiner: That says a lot, but of course no attempt has yet been made to introduce the plant itself, according to its forms, to the child. How about doing the following, for example. You could ask: "Have you ever gone for a walk in the summer? Haven't you seen flowers in the fields that, when you blow on them, parts of them fly away? They have little fans that fly away. Then you saw these flowers a little earlier, when we weren't so close to summer. Then it looks as if there were only yellow leaf-like structures at the top. And even earlier, closer to spring, there were only green leaves, which are very pointed.

What we are looking at here, at three different times, is always the same plant! Only at first it is mainly green leaves, then it is mainly flowers, and later it is mainly fruit. Because those are just the fruits flying around. The whole thing is a dandelion! First it gets leaves, the green ones; then it sprouts flowers and afterwards it gets its fruits. How does all this happen? How is it that this dandelion, which you know, first shows itself with only green leaves, then with flowers and afterwards with little fruits?

This is why: when the green leaves grow out of the ground, it is not yet so hot in the year. The heat is not yet so strong. But what is there around the green leaves? You know. It is something you only feel when the wind blows, but it is always around you: the air. You know this, we have already talked about it. The air is mainly responsible for producing the green leaves, and when the air is more permeated by heat, when it gets warmer, the leaves no longer remain leaves, but the uppermost leaves turn into flowers. But the heat doesn't just go to the plant, it also goes to the earth and then back again. You have certainly been somewhere where there was a piece of sheet metal. There you will have noticed that the sheet metal first receives the warmth from the sun and then radiates it back out again. Actually, every object does this. And this is what the warmth does: when it is still radiating down, when the earth has not yet become so warm, it forms the blossom. And when the warmth radiates back up from the earth to the plant, it first forms the fruit. That is why the fruit has to wait until autumn.

Now you can go further in such a consideration, and in this way you can try to elaborate on the idea first raised today, namely to relate plants to the external elements. In this way you will also bring the morphology, the form of the plants, into contact with the outside world. Try to do that.

D. talks about teaching about plants.

Rudolf Steiner: Many excellent things have been said, but we must work toward giving children an overview of plants: first the lower ones, then the middle ones, then the higher ones. Scholarly knowledge can be left out entirely. Creating an overview of plants is not easy, but it can be very important for teaching, and it can be developed from the plant world.

Several teachers give longer explanations. One of them says, “The root serves to nourish the plant.”

Rudolf Steiner: The expression “serve” should be avoided. It is not the root that “serves” to nourish, but rather the root is connected to the water life of the earth, to the sap life, while the leaves develop in the air. But what the plant draws from the soil is not the plant's main food, but rather the carbon from above, from the air. The plant takes in nourishment from above.

Children will not immediately grasp the idea of metamorphosis, but they will understand the connection between water and roots, air and leaves, warmth and flowers.It is not a good idea to discuss the process of fertilization in plants too early, at least not at the age when children are beginning to study botany. The reason for this is not that children do not really understand the process of fertilization. It can be described to them, but they will not find any inner understanding of it.

This has to do with the fact that the fertilization process in plants is not as remarkable as is assumed in today's abstract scientific world. Just read Goethe's beautiful essays from the 1820s, where he wrote about “dusting” and so on, where he defended metamorphosis against the actual fertilization process, and where he rails against the fact that people consider it so terribly important to describe the fields as a continuous, perpetual marriage bed. Goethe resented the fact that too much emphasis was placed on the fertilization process in plants. Metamorphosis is much more important than the fertilization process. Even if we can no longer share Goethe's belief that fertilization is actually something secondary and that plants grow mainly through metamorphosis, through themselves, even if today, according to advanced knowledge, the fertilization process must be regarded as important, it remains true that we are actually doing wrong when we emphasize the fertilization process in plants as much as we do today. We must allow it to recede more into the background and replace it with the plant's relationship to its environment. It is much more important to describe how air, heat, light, and water affect the plant than this abstract fertilization process, which is so much in the foreground today. I would like to emphasize this in particular. And because this is really a crucial point and of particular importance, I would like you to cross this Rubicon and continue to explore in this direction: Find the right methodology, the right way of treating plants.

I would like to point out that you can easily ask: What are the similarities between animals and humans? You will find a variety of opinions. But the external method of comparison soon fails when one looks for similarities between plants and humans. But one can also ask oneself: Are we perhaps looking in the wrong place when we seek such comparisons?

The closest thing to what should be assumed here is what Mr. R. touched on, but then dropped and did not elaborate on.

We can now start from something that you know, but that you cannot teach to a child at a young age. But perhaps you can think about how you can put what you know very well in theoretical terms into words that a child can understand before our next meeting.

So, it is true that we cannot directly compare humans, as they appear to us, with plants, but there are certain similarities. Yesterday I tried to draw the human torso as a kind of imperfect sphere. What belongs to it, what you would get if you completed the sphere, has a certain similarity to the plant in its interaction with the human being. Yes, one could go even further and say: If you, especially for the middle senses, for the sense of warmth, the sense of sight, the sense of taste, the sense of smell, the human being — forgive the comparison! You will have to translate it into childish terms — “stuff” it, you would get all kinds of plant forms. Simply by stuffing a soft material into the human being, it would take on plant forms by itself. The plant world is, in a sense, a kind of negative for the human being: it is the complement.

In other words, when you fall asleep, your actual soul leaves your body; when you wake up, your soul, your I and your actual soul, enters your body again. You cannot really compare the plant world with this body that remains in bed. But you can compare the plant world with the soul itself, which goes out and comes in. And when you walk through the fields and meadows and see the plants shining with their flowers, you can ask yourself: What kind of temperament is coming out of them? It is fiery! — You can compare these bursting forces that come toward you from the flowers with soul qualities. - Or you walk through the forest and see sponges, mushrooms, and ask yourself: What kind of temperament is that that comes out? Why isn't it in the sun? These mushrooms are the phlegmatic ones.

So when you move on to the soul, you will find moments of comparison with the plant world everywhere. Just try to develop them! While you have to compare the animal world more with the physicality of humans, you have to compare the plant world more with the soul of humans, with what “stuffs” humans, namely stuffs them with soul when they wake up in the morning. The plant world complements humans, just as their soul complements them. If we were to stuff the forms, we would get the plant forms. You would also see, if you managed to preserve humans like mummies, and when removing them, left only the blood vessels and nerve pathways empty, and poured a very soft substance into them, you would get all kinds of forms through the hollow forms of humans.

The plant world relates to humans as I have just explained, and you must try to make it clear to children how the roots are more closely related to human thoughts, the flowers more to human feelings, even to the affects, the emotions.

That is why the most perfect plants, the higher flowering plants, have the least animalistic qualities. The most animalistic qualities are found in fungi and the lowest plants, which are also the least comparable to the human soul.

So work towards extending this idea of starting from the soul and seeking the plant characteristics across a wide variety of plants. In this way, you characterize the plants, some of which develop more of a fruit character: mushrooms and so on; others more of a leaf character: ferns, lower plants; even palms have their mighty leaves. Only these organs are developed in different ways. A cactus is a cactus because its leaves proliferate in their growth; its flowers and fruit are only something that is scattered among the proliferating leaves.

So try to translate the idea I have suggested to you into something childlike. Use your imagination so that by next time you can describe the plant world across the earth as something that shoots up like the soul of the earth into grass and flowers, the visible, manifest soul.

And use the different regions of the earth, warm zones, temperate zones, cold zones, according to the predominant plant growth, just as in humans the different sensory areas in their souls make their contributions. Try to understand how the whole of vegetation can be compared to the world of sound that humans absorb into their souls. How one type of vegetation can be compared to the world of light, another to the world of smell, and so on.

Then make the idea fruitful by finding out the difference between annual and perennial plants, between Western, Central European, and Eastern European flora. Develop the idea that in summer the whole earth actually sleeps and in winter it wakes up.

You see, when you do something like this, you awaken a great deal of sense in the child for meaningfulness and spirituality. Later, when the child is a grown-up, they will understand much better how absurd it is to believe that the human soul ceases to exist in the evening and begins again in the morning, if you have compared the correspondence between body and soul in humans with the interrelationship between the human world and the plant world, as well as between body and soul. How does the earth affect the plant? The earth affects the plant just as the human body affects the soul. The plant world is everywhere the opposite of the human being, so that when you come to the plant world, you will have to compare the human body with the earth — and with something else, which you will discover for yourself. I only wanted to give you hints so that you can be as inventive as possible and come up with even more ideas by next time. Then you will see that you are doing the children a lot of good if you teach them inner comparisons rather than outer ones.