Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

5 September 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Fourteen

The principles were developed for teaching music to the first and second grades.

RUDOLF STEINER: Children should be allowed to hear an instrument, to hear music objectively, apart from themselves. This is important. It should be a matter of principle that well before the ninth year the children should learn to play solo instruments, and the piano can be added later for those for whom it is considered advisable. What matters most is that we make a right beginning in this sphere.

Further remark on the concept of interest, proceeding to algebra: If \(A =\) amount, \(P =\) principal, \(I =\) interest, \(R =\) rate of interest, \(T =\) time, then \(A = P + I\). Since \(I = \frac{P \cdot R \cdot T}{100}\) then \(A = P + \frac{P \cdot R \cdot T}{100}\)

RUDOLF STEINER: It would never be possible to describe capital in this way these days; this formula only has real value if \(T\) equals a year or less, because in reality two cases are given: Either you remove the interest each year, in which case the same initial capital always remains, or else you leave the interest with the capital, in which case you need to figure according to compound interest. If you omit \(T\)—that is, if you figure it for only one year, then it is an actual thing; it is essential to present realities to the children. Do not fail to observe that the transition to algebra as we have spoken of it, is really carried out—first from addition to multiplication, and then from subtraction to division. This must be adhered to strictly.

RUDOLF STEINER explained the transition from arithmetic to algebra with the following example: First you write down a number of figures in which all the addenda are different:

$$20 = 7 + 5 + 6 + 2$$Some of the addenda could also be equal:

$$25 = 5 + 5 + 9 + 6$$Or all the addenda could be the same:

$$18 = 6 + 6 + 6$$If you proceed, as described in our previous discussion, to replace numbers with letters, then you could have the equation:

\(S_1 = a + a + a\); that is, three \(a\)’s, or three times \(a = 3a\).

then

\(S_2 = a + a + a + a + a\); five times \(a = 5a\);then

\(S_3 = a + a + a + a + a + a + a\); or seven times \(a = 7a\)

and so on. I can keep doing this; I could do it \(9\) times, \(21\) times, \(25\) times, I can do it \(n\) times:

\(S_n = a + a + a ... n\) times \(= na\)

Thus, I get the factor by varying the number of the addenda, while the addendum itself is the other factor. In this way multiplication can easily be developed and understood from addition, and you thus make the transition from actual numbers to algebraic quantities:

\(a × a = a2\), \(a × a × a = a3\).

In the same way you can derive division from subtraction. If we take b away from a very large number a, we get the remainder \(r\):

\(r = a – b\)

If we take b away again, we get the remainder:

\(r_2 = a – b – b = a – 2b\)

If b is taken away a third time we obtain:

\(r_3 = a – b – b – b = a – 3b\) and so on.

We could continue until there is nothing left of number \(a\): suppose this happens after subtracting \(b\) \(n\) times:

\(r_n = a – b – b – b ... n\) times \(= – nb\) When there is nothing left—that is, when the last remainder is \(0\), then:

\(0 = a – nb\)

So a is now completely divided up, because nothing remains:

\(a = nb\)

I have taken b away n times, I have divided \(a\) into nothing but \(bs\), \(a/b = n\), so the \(a\) is completely used up. I have discovered that I can do this \(n\) times, and in so doing I have gone from subtraction to division.

Thus we can say: multiplication is a special case of addition, and division is a special case of subtraction, except that you add to it or take away from it, not just once, but repeatedly, as the case may be.

Negative and imaginary numbers were discussed.

RUDOLF STEINER: A negative number is a subtrahend [the number subtracted] for which there is no minuend [the number from which it is subtracted]; it is a demand that something be done: there being nothing to do it with, thus it cannot be done. Eugen Dühring rejected imaginary numbers as nonsense and spoke of Gauss’s definition of “the imaginary” as completely stupid, unrealistic, farfetched nonsense.1Karl Eugen Dühring (1833–1921), German positivist philosopher and economist. Wrote Kapital und Arbeit (Capital and Labor), and Logik und Wissenschaftstheorie (Logic and Epistemological Theory).

From addition, therefore, you develop multiplication, and from multiplication, rise to a higher power. And then from subtraction you develop division, and from division, find roots.

addition—subtraction

multiplication—division

raising to a higher power—finding roots

You should not proceed to raising to a higher power and finding roots until after you have begun algebra (between the eleventh and twelfth years), because, with roots, raising to a power of an algebraic equation of more than one term (polynomial) plays a role. In this connection you should also deal with figuring gross, net, taxes, and packing charges.

A question about the use of formulas.

RUDOLF STEINER: The question is whether you should avoid the habitual use of formulas, but go through the thought processes again and again (a good opportunity for practicing speech), or whether it might be even better to go ahead and use the formula itself. If you can succeed, tactfully, in making the formula fully understood, then it can be very useful to use it as a speech exercise—to a certain extent.

But from a certain age on, it is also good to make the formula into something felt by the children, make it into something that has inner life, so that, for example, when the \(T\) increases in the formula \(I = PRT/100\), it gives the children a feeling of the whole thing growing.

In effect, this is what I wanted to say at this point—that you should use the actual numbers for problems of this kind—for example, in interest and percentages—in order to make the transition to algebra, and in doing so, develop multiplication, division, raising powers, and roots. These are things that certainly must be done with the children.

Now I would like to ask a question: Do you consider it good to deal with raising to a higher power and finding roots before you have done algebra, or would you do it later?

Comment about raising to a higher power first and finding roots after.

RUDOLF STEINER: Your plan then would be (and should continue to be) to start with algebra as soon as possible after the eleventh or twelfth year, and only after that proceed to raising to a higher power and finding roots. After teaching the children algebra, you can show them in a very quick and simple way how to square, cube, raise to a higher power, and extract the root, whereas before they know algebra you would have to spend a terribly long time on it. You can teach easily and economically if you take algebra first.

A historical survey for the older children (eleven to fourteen years) was presented concerning the founding and development of towns, referring to the existence of a “Germany” at the time of the invasion of the Magyars.

RUDOLF STEINER: You must be very careful not to allow muddled concepts to arise unconsciously. At the time of Henry, the so-called “townbuilder,” there was of course no “Germany.” You would have to express what you mean by saying “towns on the Rhine” or “towns on the Danube” in the districts that later became “German.”2This could as well apply to speaking of “America” in regard to events and places prior to the time of Columbus and the European settlers.

Before the tenth century the Magyars are not involved at all, but there were invasions of Huns, Avars, and so on. But after the tenth century you can certainly speak of “Germany.” When the children reach the higher grades (the seventh and eighth grades) I would try to give them a concept of chronology; if you just say ninth or tenth century, you do not give a sufficiently real picture. How then would you manage to awaken in the children a concrete view of time?

You could explain it to them like this: “if you are now of such and such an age, how old are your mother and father? Then, how old are your grandfather and grandmother?” And so you evoke a picture of the whole succession of generations, and you can make it clear to the children that a series of three generations makes up about 100 years, so that in 100 years there would be three generations. A century ago the great grandparents were children. But if you go back nine centuries, there have not been three generations, but \(9\ x\ 3 = 27\) generations. You can say to the child: “Now imagine you are holding your father’s hand, and he’s holding your grandfather’s hand, and he is, in turn, holding your great-grandfather’s hand, and so on. If they were now all standing together side by side, which would be Henry I, which number in the row would have stood face to face with the Magyars around the year 926? It would be the twenty-seventh in the row.” I would demonstrate this very clearly in a pictorial way. After giving the children this concrete image of how long ago it was, I would present a graphic description of the migrations of the Magyars. I would tell them about the Magyars’ invasion of Europe at that time, how they broke in with such ferocity that everyone had to flee before them, even the little children in their cradles, who had to be carried up to the mountaintops, and how then the onrushing Magyars burned the villages and forests. Give them a vivid picture of this Magyar onset.

It was then described how Henry, knowing he had been able to resist the Magyars in fortified Goslar, resolved to build fortified towns, and in this way it come about that numerous towns were founded.

RUDOLF STEINER: Here again, could you not present this more in connection with the whole history of civilization? It is only a garbled historical legend to say that Henry founded these towns. All these tenth century towns were built on their original foundations—that is, the markets—before then. But what helped them to expand was the migration of the neighboring people into the towns in order to defend themselves more easily against the Magyars’ assaults, and for this reason they fortified these places. The main reasons for building these towns were more economic in nature. Henry had very little part in all this.

I ask you to be truly graphic in your descriptions, to make everything really alive, so that the children get vivid pictures in their minds, and the whole course of events stands out clearly before them. You must stimulate their imagination and use methods such as those I mentioned when I showed you how to make time more real. Nothing is actually gained by knowing the year that something occurred—for example, the battle of Zama; but by using the imagination, by knowing that, if they held hands with all the generations back to Charles the Great, the time of their thirtieth ancestor, the children would get a truly graphic, concrete idea of time. This point of time then grows much closer to you—it really does—when you know that Charles the Great is there with your thirtieth ancestor.

Question: Wouldn’t it also be good when presenting historical descriptions to dwell on the difference in thought and feeling of the people of those times?

RUDOLF STEINER: Yes. I have always pointed this out in my lectures and elsewhere. Most of all, when speaking of the great change that occurred around the fifteenth century, you should make it very clear that there was a great difference between the perception, feeling, and thought of people before and after this time. Lamprecht too (whom I do not however especially recommend) is careful to describe a completely different kind of thinking, perceiving, and feeling in people before this time.3Karl Gottfried Lamprecht (1856–1915), historian who developed the theory that history is social-psychological rather than political. The documents concerning this point have not yet been consulted at all.

In studying the books written on cultural history you must, above all, develop a certain perceptive faculty; with this you can properly assess all the different things related by historians, whether commonplace or of greater importance, and so gain a truer picture of human history.

Rudolf Steiner recommended for the teachers’ library Buckle’s History of Civilization in England and Lecky’s History of Rationalism in Europe.

RUDOLF STEINER: From these books you can learn the proper methods of studying the history of human progress. With Lamprecht only his earlier work would be suitable, but even much of this is distorted and subjective. If you have not acquired this instinct for the real forces at work in history, you will be in danger of falling into the stupidity and amateurism of a “Wildenbruch” for example;4Ernst von Wildenbruch (1845–1909), German writer, author of Spartacus. he imagined that the stories of emperors and kings and the family brawls between Louis the Pious and his sons were important events in human history.

Gustav Freytag’s Stories from Ancient German History are very good;5Gustav Freytag (1816–1895), German writer, promoter of German liberalism and the middle class. His books included a series of six historical novels. but you must beware of being influenced too much by this rather smug type of history book (written for the unsophisticated). The time has come now when we must get out of a kind of thinking and feeling that belonged to the middle of the nineteenth century.

Mention was made of Houston Stuart Chamberlain’s Foundations of the Nineteenth Century.6Houston Stuart Chamberlain (1855–1927), British publicist, naturalized German citizen. Wrote on the superiority of the Western Aryan race.

RUDOLF STEINER: With regard to Chamberlain also you must try to develop the correct instinct. For one part of clever writing you get three parts of bad, unwholesome stuff. He has some very good things to say, but you must read it all yourselves and form your own judgements. The historical accounts of Buckle and Lecky are better.7Probably refers to Henry Thomas Buckle (1821–1862), English historian, who wrote the incomplete History of Civilization in England. William Edward Hartpole Lecky 1838–1903), Irish historian who wrote on modern European history. Chamberlain is more one of these “gentlemen in a dinner jacket.” He is rather a vain person and cannot be accepted as an authority, although many of his observations are correct. And the way he ended up was not particularly nice—I mean his lawsuit with the “Frankfurter Zeitung.”

Kautsky’s writings were mentioned.8Karl Johann Kautsky (1854–1938), German Marxist theorist, journalist, and secretary to Friedrich Engels in London, he opposed Bolshevism and the Russian revolution.

RUDOLF STEINER: Well yes, but as a rule you must assume that the opposite of what he says is true! From modern socialists you can get good material in the way of facts, as long as you do not allow yourselves to be deceived by the theories that color all their descriptions. Mehring too presents us with rather a peculiar picture;9Franz Mehring (1846–1919), German Socialist historian and journalist. because at first, when he was himself a progressive Liberal, he inveighed against the Social Democrats in his book on Social Democracy; but later when he had gone over to the Social Democrats he said exactly the same things about the Liberals!

An introduction was presented on the fundamental ideas in mathematical geography for twelve-year-old children, with observations on the sunrise and the ecliptic.

RUDOLF STEINER: After taking the children out for observations, it would be very good to let them draw what they had observed; you would have to make sure there is a certain parallel between the drawing and what the children saw outside. It is advisable not to have them do too much line drawing. It is very important to teach these things, but if you include too much you will reach the point where the children can no longer understand what you are saying. You can relate it also to geography and geometry.

When you have developed the idea of the ecliptic and of the coordinates, that is about as far as you should go.

Someone else developed the same theme—that is, sunrise and sunset—for the younger children, and tried to explain the path of the Sun and planets in a diagrammatic drawing.

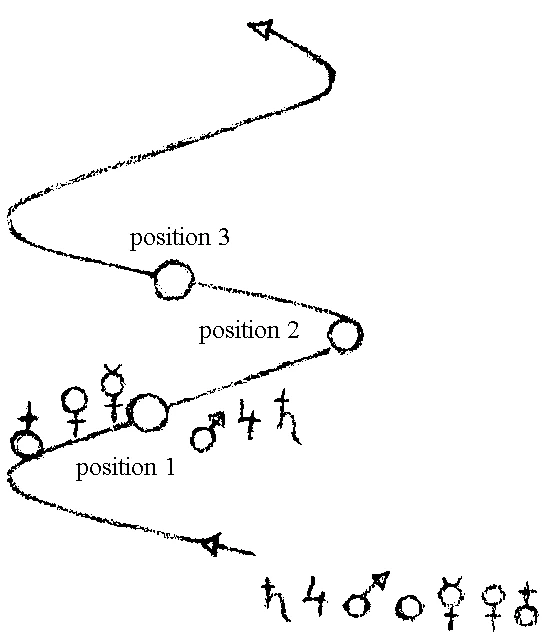

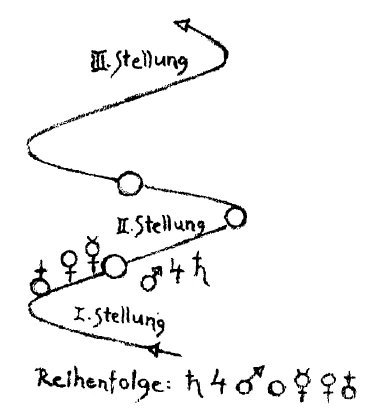

RUDOLF STEINER: This viewpoint will gradually lose more and more of its meaning, because what has been said until now about these movements is not quite correct. In reality it is a case of a movement like this (lemniscatory screw-movement):

Here, for example, [in position 1] we have the Sun; here are Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, and here are Venus, Mercury, and Earth. Now they all move in the direction indicated [spiral line], moving ahead one behind the other, so that when the Sun has progressed to the second position we have Saturn, Jupiter, and Mars here, and we have Venus, Mercury, and Earth over there. Now the Sun continues to revolve and progresses to here [position 3]. This creates the illusion that Earth revolves round the Sun. The truth is that the Sun goes ahead, and the Earth creeps continually after it.

The ancient Egyptian civilization was described.

RUDOLF STEINER: It is most important to explain to the children that Egyptian art was based on a completely different method of representing nature. The ancient Egyptians lacked the power of seeing things in perspective. They painted the face from the side and the body from the front. You may certainly explain this to the children, especially the Egyptian concept of painting. Then you must point out how Egyptian drawing and painting was related to their view of natural history—how, for example, they portrayed men with animal heads and so on.

In ancient times the habit of comparing people with the animals was very common. You could then point out to the children what is present in seed form, as it were, within every human face, which children can still see to a certain extent.10See The Foundations of Human Experience, lecture 9. The Egyptians still perceived this affinity of the human physiognomy with animals; they were still at this childlike stage of perception.

Question: What should one really tell children about the building of the Egyptian pyramids?

RUDOLF STEINER: It is of course extraordinarily important for children too that you should gradually try to present them with what is true rather than what is false. In reality the pyramids were places of initiation, and this is where you reach the point of giving the children an idea of the higher Egyptian education, which was initiation at the same time. You must tell them something about what happened within the pyramids. Religious services were conducted there, just as today they are conducted in churches, except that their services led to knowledge of the universe. Ancient Egyptians learned through being shown, in solemn ritual, what comes about in the universe and in human evolution. Religious exercises and instruction were the same; it was really such that instruction and religious services were the very same thing.

Someone described the work of the Egyptians on the pyramids and obelisks, and said that several millions of people must have been needed to transport the gigantic blocks of stone, to shape them, and to set them in place. We must ask ourselves how it was possible at all, with the technical means available at that time, to move these great heavy blocks of limestone and granite and to set them in place.

RUDOLF STEINER: Yes, but you only give the children a true picture when you tell them: If people were to do this work with the physical strength of the present day, two and a half times as many people would be necessary. The fact is that the Egyptians had two and a half times the physical strength that people have today; this is true, at least, of those who worked on the pyramids and so on. There were also, of course, those who were not so strong.

Question: Would it be good to include Egyptian mythology?

RUDOLF STEINER: Unless you can present Egyptian mythology in its true form, it should be omitted. But in the Waldorf school, if you want to go into this subject at all, it would be a very good plan to introduce the children to the ideas of Egyptian mythology that are true, and are well known to you.11See Rudolf Steiner, Egyptian Myths and Mysteries, Anthroposophic Press, Hudson, NY, 1990.

Vierzehnte Seminarbesprechung

U. entwickelt die Prinzipien des musikalischen Unterrichts im ersten und zweiten Schuljahr.

Rudolf Steiner: Man sollte nicht versäumen, das Objektive, vom Menschen Abgesonderte, das Instrument, auch hören zu lassen. Immer muß darauf gesehen werden, daß das Kind ziemlich lange vor dem neunten Jahre, in der zweiten Hälfte des zweiten Schuljahres, an das Soloinstrument herankommt, so daß das Klavier sich später anschließen würde für diejenigen, die dafür in Betracht kommen. Das ist ja das Wesentliche, daß wir auf diesem Gebiete richtig anfangen.

T. gibt eine Fortsetzung der Zinsrechnung mit Übergang zur Buchstabenrechnung. Wenn \(E\) = Endkapital, \(A\) = Anfangskapital, \(Z\) = Zins, \(P\) = Prozentsatz, \(T\) = Zeit ist so ist \(E = A + Z\). Da ferner \(Z = \frac{A \cdot P \cdot T}{100}\) so wird \(E = A + \frac{A \cdot P \cdot T}{100}\)

Rudolf Steiner: In dieser Form kann man ja heute nie ein Kapital anlegen. Diese Form hat nur dann einen Realitätswert, wenn \(7\) gleich oder kleiner als ein Jahr ist. Denn in der Realität sind zwei Fälle gegeben: entweder man hebt die Zinsen jährlich ab, dann verbleibt immer das gleiche Anfangskapital, oder man läßt die Zinsen beim Kapital, dann braucht man die Zinseszinsrechnung. Läßt man \(T\) weg, das heißt, rechnet man für ein Jahr, dann ist es real. Es ist notwendig, den Kindern die Realität zu geben.

Es wird gut sein, stramm darauf hinzuarbeiten, daß der Übergang in die Buchstabenrechnung auch wirklich gemacht wird. Zunächst wird man den Übergang entwickeln von der Addition in die Multiplikation, dann von der Subtraktion in die Division.

Rudolf Steiner erläutert dann den Übergang vom Zahlenrechnen zum Buchstabenrechnen an nachfolgendem Beispiel. Man schreibt zunächst eine Summe von Zahlen hin, in welcher die Addenden alle ungleich sind:

$$20 = 7 + 5 + 6 + 2$$

Es können auch einzelne Addenden gleich sein:

$$25=5+5+976$$

Und es können alle Addenden gleich sein:

$$18=6+6+6$$

Geht man nun in der gestern bereits geschilderten Weise dazu über, die Zahlen durch Buchstaben zu ersetzen, so habe ich einmal die Summe \(S_1 = a + a + a,\) das sind drei \(a\), dreimal \(a=3 \cdot a\); dann, \(S_2 = a + a + a + a + a,\) fünfmal \(a=5 \cdot a\); dann \(S_3 = a + a + a + a + a +a,\) siebenmal \(a =7 \cdot a\) und so weiter.

Ich mache das immerzu, kann es neunmal, einundzwanzigmal, fünfundzwanzigmal machen. Ich mache es \(m\)-mal: S\(S_m = a + a + a + a + a...\) \(m\)-mal -( = m \cdot a.\)

So bekomme ich aus der Unbestimmtheit der Anzahl der Addenden den einen Faktor, während der Addend selbst der andere Faktor ist. Auf diese Weise läßt sich leicht aus der Addition die Multiplikation entwickeln und begreifen. So macht man den Übergang von bestimmten Zahlen zu algebraischen Größen, zu \( a \cdot a = a^2, a \cdot a \cdot a = a^3.\)

Ebenso kann man aus der Subtraktion die Division ableiten.

Wenn wir \(b\) wegnehmen von einer sehr großen Zahl a, dann bekommen wir den Rest \(r_1.\)

$$r_1 = a - b$$

Nehmen wir nochmals 5 weg, so erhalten wir den Rest

$$r_2 = a - b - b = a - 2b$$

Ein drittes Mal 5 weggenommen, ergibt

$$r_3 = a - b - b - b = a -3b$$

und so weiter.

Wir können dies so lange machen, bis von der Zahl \(a\) kein Rest mehr übrig bleibt, können es \(n\)- mal machen:

$$r_n = a - b - b - b - b ... n = a - nb$$

Wenn dann kein Rest mehr bleibt, das heißt, der letzte Rest gleich \(0) ist, so ist

$$0 = a - nb.$$

Dann ist a ganz aufgeteilt, weil ja kein Rest bleibt, \(a = nb\). Ich habe \(n\)-mal das \(b\) weggenommen, habe das \(a\) in lauter \(b\) aufgeteilt, \(\frac{a}{b} = n,\) da ist eben das a ganz aufgezehrt. Ich habe gefunden, daß ich das n-mal machen kann und bin damit übergegangen von der Subtraktion zur Division.

Man kann somit sagen: Es ist die Multiplikation ein besonderer Fall der Addition, die Division ein besonderer Fall der Subtraktion, nur daß man eben nicht nur einmal, sondern wiederholt hinzufügt, beziehungsweise wegnimmt.

Es kommt die Rede auf negative und imaginäre Zahlen.

Rudolf Steiner: Eine negative Zahl ist ein Subtrahend, zu dem kein Minuend mehr da ist; eine Aufforderung zu einer Operation, zu der kein Stoff mehr da ist, die nicht ausgeführt werden kann. - Eugen Dühring wies die imaginären Zahlen als Unsinn zurück und sagte von der Gaußschen Definition des Imaginären, sie sei eine Eselei, keine Realität, ein ausspintisiertes Zeug.

Also man entwickelt immer das Multiplizieren aus der Addition, und dann das Potenzieren aus der Multiplikation. Und weiter das Dividieren aus der Subtraktion, das Radizieren aus der Division.

addieren subtrahieren

multiplizieren dividieren

potenzieren radizieren

Erst nach Beginn der Buchstabenrechnung, vom elften bis zwölften Jahre ab, geht man zum Potenzieren und Radizieren über, weil beim Radizieren das Potenzieren eines algebraischen Polynoms eine Rolle spielt.

In diesem Zusammenhang ist weiter durchzunehmen: Brutto-, Netto-, Tara-, Emballagerechnung.

Es wird eine Frage gestellt, die Benützung von Formeln betreffend.

Rudolf Steiner: Nun handelt es sich aber darum, ob Sie lieber sehr häufig die Formel nicht benützen, sondern immer wieder den Gedankengang machen wollen — wobei Sie ja allerdings Sprachkultur treiben können, das ist ja richtig -, oder aber, ob Sie nicht doch zur Formel übergehen wollen. Wenn Sie es taktvoll machen, daß die Formel gut verstanden wird, ist das auch recht nützlich, um bis zu einem gewissen Grade Sprachkultur daran zu üben.

Aber von einem gewissen Zeitpunkt an ist es auch gut, die Formel zu etwas Gefühltem beim Kinde zu machen. Die Formel zu etwas zu machen, was inneres Leben hat, so daß zum Beispiel wenn bei

$$Z = \frac{K \cdot P \cdot T}{100}$$

das \(T\) größer wird, das Kind ein Gefühl von dem Anwachsen des Ganzen dabei bekommt.

Damit würde also gesagt worden sein, was ich an dieser Stelle sagen wollte, daß man die konkreten Zahlen benützen sollte bei einer solchen Gelegenheit wie bei der Zins- und Prozentrechnung, um den Übergang zur Buchstabenrechnung zu finden, und um daran Multiplizieren, Dividieren, Potenzieren, Radizieren zu entwickeln. Das sind ja Dinge, die durchaus mit den Kindern schon gemacht werden müssen.

Nun möchte ich die Frage aufwerfen: Halten Sie es für gut, das Potenzieren und das Wurzelziehen, das Radizieren, schon zu behandeln, bevor Sie Buchstabenrechnung gemacht haben, oder würden Sie es nachher machen?

T.: Potenzieren vorher, Radizieren nachher.

Rudolf Steiner: Also Sie gehen doch aus und sollten auch in Zukunft davon ausgehen, daß Sie möglichst bald, vom elften, zwölften Jahre ab, mit der Buchstabenrechnung beginnen und dann erst zum Potenzieren, Radizieren übergehen. Denn nach der Buchstabenrechnung läßt sich auf sehr einfache und ökonomische Weise quadrieren, kubieren, potenzieren und wurzelziehen mit den Kindern, während man vorher furchtbar viel Zeit darauf verwendet. Sie werden leicht und ökonomisch unterrichten, wenn Sie zuerst die Buchstabenrechnung mit den Kindern besprochen haben.

E. gibt eine geschichtliche Ausarbeitung für Schüler der letzten Klasse über Städtegründung und -entwicklung und spricht für die Zeit der Magyareneinfälle von «Deutschland».

Rudolf Steiner: Ich würde da doch recht achtgeben, daß nicht unbewußt verwurstelte Vorstellungen entstehen. Es gab natürlich damals, zur Zeit Heinrichs, des sogenannten Städtebauers, kein Deutschland. Man muß sich etwa so ausdrücken: Städte am Rhein oder an der Donau, an den Orten, die später deutsch geworden sind. Nicht wahr, vor dem 10. Jahrhundert hat man es ja auch nicht mit Magyaren zu tun; vorher hat man es bei solchen Einfällen mit Hunnen, Avaren zu tun. Vom 10. Jahrhundert an kann man dann schon sagen «Deutschland».

Sehen Sie, ich würde da zum Beispiel - das ist ja eine Aufgabe, die man vornimmt bei den Schülern der letzten Volksschulklassen — den Kindern einen Begriff der Chronologie beizubringen versuchen. Wenn man so sagt «9., 10. Jahrhundert», da wird die Vorstellung zu wenig konkret. Wie würden Sie das machen, daß eine konkrete Vorstellung von der Zeit bei den Kindern ersteht?

Da könnten Sie dem Kinde klarmachen: «Wenn du jetzt so alt bist, wie alt sind deine Mutter, dein Vater? Dann, wie alt sind Großvater und Großmutter?» — Da bringen Sie die ganze Generationenfolge heraus und können dem Kinde klarmachen, daß eine solche von drei Generationen etwa hundert Jahre ausmacht. Also in hundert Jahren wären es drei Generationen. Vor hundert Jahren waren also die Urgroßeltern Kinder. Vor neun Jahrhunderten waren es nicht drei, sondern 9:3 = 27 Generationen. — «Nimm einmal an», sagt man zum Kinde, «du hältst die Hand deines Vaters, der hält die Hand deines Großvaters, der die Hand deines Urgroßvaters und so fort. Wenn sie nun so nebeneinander stünden, der wievielte Mann wäre Heinrich I., der wievielte Mann würde dann den Magyaren etwa um das Jahr 926 gegenüberstehen? Der siebenundzwanzigste Mensch würde das sein.» - Das würde ich dann recht anschaulich darstellen. Nachdem ich so die Kinder konkret zu der Vorstellung gebracht habe, wie lange das her ist, dann würde ich ihnen schildern die Magyarenzüge. Würde ihnen klarmachen, wie die Magyaren damals Mitteleuropa überfielen. Wie die Magyaren hereinbrachen mit einer Wildheit, so daß alles flüchten mußte bis auf die kleinen Kinder in den Wiegen, die man auf die Gipfel der Berge tragen mußte. Wie dann die hereinbrechenden Magyaren Dörfer und Wälder verbrannten. Recht anschaulich würde ich den Magyarensturm schildern.

E. schildert weiter, wie Heinrich aus der Erkenntnis heraus, daß er in dem befestigten Goslar den Magyaren habe widerstehen können, den Entschluß zur Grün dung befestigter Städte gefaßt habe, und daß es auf diese Weise zu zahlreichen Städtegründungen gekommen sei.

Rudolf Steiner: Könnten Sie diese Darstellung nicht noch einmal kulturhistorisch bringen? Denn das ist etwas monarchisch auffrisierte Geschichtslegende, daß Heinrich diese Städte gegründet habe. Alle diese Städte des 10. Jahrhunderts waren ja in ihrer Grundanlage, in den Märkten, schon da. Sie wurden nur in ihrem Ausbau dadurch gefördert, daß Leute, die in der Nachbarschaft dieser Städte wohnten, sich anschlossen, um eine leichtere Verteidigungsmöglichkeit zu gewinnen gegen die anstürmenden Magyaren, und so diese Orte stärkten. Es waren mehr wirtschaftliche Gründe, die da wirkten und die zur Städtebildung führten. Heinrich hat nicht gar viel dazu getan.

Ich würde Sie nur bitten, recht anschaulich das alles zu bringen, recht lebendig zu verfahren, damit die Kinder innerlich anschauliche Bilder bekommen, so daß die Kinder förmlich alles greifen können. Sie müssen die Phantasie in Anspruch nehmen und solche Dinge benützen, wie ich sie Ihnen gezeigt habe bei dem Konkretmachen der Zeit. Man hat tatsächlich nichts davon, zu wissen, in welchem Jahre zum Beispiel die Schlacht bei Zama gewesen ist und so weiter, aber wenn man sich vorstellt, wenn man weiß, daß Karl der Große zum dreißigsten Vorfahren hinaufreicht, wenn man sich durch die Generationen hindurch die Hände reichen würde, dann erhält man dadurch eine anschauliche, konkrete Vorstellung von der Zeit. Da rückt diese Zeit viel näher — ja freilich, sie rückt viel näher! -, wenn man weiß, daß Karl der Große bis zum dreißigsten Vorfahren hinauf zu finden ist.

T.: Wäre es nicht gut, bei solchen Kulturbeschreibungen auch auf das ganz andere Denken und Fühlen der Menschen in diesen Perioden hinzuweisen?

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, darauf habe ich ja immer in meinen Vorträgen und auch sonst hingewiesen. Vor allem auch, daß Sie namentlich den großen Umschwung um das 15. Jahrhundert, das ganz andere Empfinden, Fühlen und Denken der Menschen vor und nach dieser Zeit recht anschaulich machen. Zum Beispiel auch schon Lamprecht, den ich aber damit nicht besonders empfehlen will, ist bemüht, ein ganz anderes Denken, Empfinden und Fühlen der Menschen vor dieser Zeitperiode zu konstatieren. -— Die Dokumente sind daraufhin noch gar nicht benützt worden.

Wenn Sie sich ein bißchen hineinfinden wollen in die kulturgeschichtliche Betrachtung, so müssen Sie vor allem entwickeln können einen gewissen Spürsinn, und wenn Sie diesen haben für Weiteres und Engeres, was die Autoren erzählen, für Spießigeres und etwas Weitherzigeres, dann können Sie richtigere Vorstellungen gewinnen für Kulturgeschichtliches.

Rudolf Steiner empfiehlt auf eine Anfrage hin zur Anschaffung für die Lehrerbibliothek:

Buckle, Geschichte der Zivilisation in England.

Lecky, Geschichte der Aufklärung in Europa.

An diesen kann man die Methode schulen für die kulturgeschichtlichen Betrachtungen. Von Lamprecht kämen in Frage die älteren Teile, aber es ist vieles schief und subjektiv.

Wenn Sie sich diesen Instinkt für die wirklichen treibenden kulturgeschichtlichen Kräfte nicht angeeignet haben, dann werden Sie Gefahr laufen, mit wahrhaft Wildenbruchscher Blödigkeit, mit Wildenbruchscher Dilettantenhaftigkeit zum Beispiel die Kaiser- und Königsdramen und solche Familienkatzbalgereien wie zwischen Ludwig dem Frommen und seinen Söhnen für wesentliche kulturgeschichtliche Ereignisse zu halten.

Gustav Freytags «Bilder aus der deutschen Vergangenheit» sind ganz gut, aber man darf sich nicht zu sehr beschmieren lassen von dieser Gemütlichkeit einer für Tanten geschriebenen Geschichtsbetrachtung. Wir müssen gerade heute herauskommen aus dem Denk- und Empfindungsstil, der so bei diesen Leuten der Grenzbotenliteratur der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts da war, bei Gustav Freytag, Julian Schmidt und so weiter. Lassalle nannte ihn «Schmulian Jüd»; bei Lassalle klang das nicht antisemitisch.

Es wird gefragt, nach Houston Stewart Chamberlains «Grundlagen des 19. Jahrhunderts».

Rudolf Steiner: Auch bei Chamberlain muß man erst recht einen guten Instinkt entwickeln, denn ein Viertel bei ihm ist geistreich, und drei Viertel ist wüstes, ungesundes Zeug. Es steht sehr viel sehr Gutes bei ihm, aber man muß alles selber übersehen und selber ein Urteil entwickeln. Die kulturgeschichtlichen Schilderungen sind besser bei Buckle und Lecky. Chamberlain ist mehr so ein Smokingträger. Er ist doch ein etwas eitler Herr, der nicht gerade als Autorität zu gelten hat, der aber doch manches richtig bemerkt hat. Es ist ja auch sein Ende kein schönes gewesen, ich meine den Prozeß mit der «Frankfurter Zeitung».

Es werden Kautskys Schriften erwähnt.

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, wenn man in der Regel das Gegenteil von dem annimmt, das er da zeigt. Man bekommt von modernen Sozialisten ein gutes und interessantes Taatsachenmaterial, wenn man sich nicht betäuben läßt von den Theorien, die ihre Schilderungen durchziehen.

Ein eigentümliches Bild bietet auch Mehring, wie er erst in seinem Buch, in seiner Geschichte der Sozialdemokratie, auf die Sozialdemokraten schimpft, so lange er Freisinniger war; dann nachher, als er zu den Sozialdemokraten übergetreten war, ändert er das nur um auf die Freisinnigen.

M. gibt eine Einführung in die Grundbegriffe der mathematischen Geographie für Schüler im dreizehnten Jahr, Beobachtungen am Sonnenaufgang und an der Sonnenbahn.

Rudolf Steiner: Sie können, wenn Sie die Kinder hinausbestellt haben, das später sehr gut in die Zeichnung verwandeln lassen und darauf sehen, daß ein gewisser Parallelismus besteht zwischen der Zeichnung und dem, was die Kinder draußen angesehen haben. Es ist nur ratsam, nicht zuviel auf einmal von diesem Linienhaften zu geben. Es ist sehr wichtig, daß man diese Dinge den Kindern beibringt, aber wenn man zuviel zusammenfaßt, dann bringt man es so weit, daß die Kinder es nicht mehr auffassen. Man kann es einfügen in Geographie und Geometrie. Der ungefähre Abschluß solcher Ausführungen würde sein, daß man den Begriff der Ekliptik und der Koordinaten entwickelt. A, führt das gleiche Thema, Sonnenaufgang und Sonnenuntergang, für kleinere Kinder aus und versucht, den Gang der Sonne und der Planeten durch eine schematische Zeichnung klarzumachen.

Rudolf Steiner: Nun, es wird diese Auffassung immer mehr an Bedeutung abnehmen, weil das seither Angenommene über diese Bewegungen nicht ganz richtig ist. In Wirklichkeit hat man es zu tun mit einer solchen Bewegung (Rudolf Steiner zeichnet an die Tafel):

Da ist zum Beispiel (1. Stellung) einmal hier die Sonne; da ist Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, und da ist Venus, Merkur, Erde. Nun bewegen sich die alle in der angegebenen Richtung (Schraubenlinie) so hintereinander fort, daß, wenn die Sonne dann da herübergekommen ist (2. Stellung), so ist Saturn, Jupiter, Mars hier, Venus, Merkur und die Erde da. Und jetzt dreht sich die Sonne weiter und geht dahin (3. Stellung). Dadurch wird der Schein hervorgerufen, als wenn sich die Erde um die Sonne drehte. In Wahrheit geht die Sonne voran, und die Erde kriecht immer nach.

B. gibt eine Darstellung aus der altägyptischen Kultur.

Rudolf Steiner: Vor allem müßte man dazu übergehen, das vorzubringen, was das ganz andere Prinzip der Nachbildung ist. Es besteht bei den alten Ägyptern der Mangel, daß sie unperspektivisch sehen. Es malt der alte Ägypter das Gesicht im Profil und den übrigen Körper en face. Diese Eigentümlichkeit der Auffassung müßte man den Kindern schon beibringen.

Dann müßte man herstellen den Zusammenhang des ägyptischen Zeichnens und Malens mit dem naturgeschichtlichen Prinzip, das sie hatten, daß sie die Menschen mit Tierköpfen machten und so weiter. Schon in alten Zeiten ist die Vergleichung des Menschen mit den Tieren sehr weit getrieben worden. Man könnte dann dem Kinde dasjenige beibringen, was veranlagt ist in jedem menschlichen Kopf und was zum Teil das Kind heute noch sieht. Die Ägypter haben noch diese Verwandtschaft der Menschenphysiognomie mit den Tieren wahrgenommen. Sie waren noch auf dieser kindlichen Stufe der Anschauung.

B. fragt bei der Besprechung der Pyramiden, was man eigentlich den Kindern darüber sagen solle.

Rudolf Steiner: Es ist natürlich außerordentlich wichtig, allmählich zu versuchen, auch für die Kinder das Richtige an die Stelle des Falschen zu setzen. Tatsächlich waren die Pyramiden ja Einweihungsstätten. Und da kommt man ja nun dahin, daß man den Kindern den Begriff des höheren ägyptischen Unterrichts, der zu gleicher Zeit eine Einweihung war, beibringt. Man muß etwas erzählen davon, was da vorgegangen ist. Es sind da religiöse Handlungen ausgeführt worden, wie sie heute in den Kirchen ausgeführt werden, die aber zugleich dazu führten, daß das Weltall erkannt werden konnte. Der alte Ägypter hat eben so gelernt, daß ihm vorgezeigt worden ist in feierlichen Handlungen, was sich im Weltall und in der Menschheitsentwickelung vollzieht. Es war religiöse Übung und Unterricht eines. Es war so, daß Unterricht und religiöse Handlung eigentlich zusammenfielen.

B. beschreibt die Arbeit an den Pyramiden und Obelisken und sagt, daß man annehmen müsse, daß zum Herbeischaffen, Bearbeiten und Einbauen der riesigen Blöcke mehrere Millionen Menschen benötigt sein müßten. Man müsse sich fragen, wie es überhaupt möglich gewesen sei, mit den damaligen technischen Hilfsmitteln die großen, schweren Kalk- und Granitblöcke zu bewegen und aufzuschichten.

Rudolf Steiner: Ja, aber ganz richtige Vorstellungen werden Sie bei den Kindern nur hervorrufen, wenn Sie ihnen sagen, daß, wenn die Menschen mit der heutigen Körperkraft arbeiten würden, man zweieinhalbmal soviel Menschen brauchen würde. Aber in Wahrheit haben die Ägypter ja zweieinhalbmal soviel Körperkräfte gehabt wie unsere heutigen Menschen, wenigstens die, die an den Pyramiden und so weiter gearbeitet haben. Es gab natürlich auch schwächere Menschen.

B. fragt, ob auch auf die Mythologie einzugehen wäre.

Rudolf Steiner: Nicht wahr, wenn man die ägyptische Mythologie nicht in ihrer wahren Gestalt darstellen kann, so muß man sie eben weglassen. Kann man aber die ägyptische Mythologie in der wahren Gestalt darstellen, dann soll man es tun. In der Waldorfschule wird es ganz gut sein, die richtigen Begriffe von der ägyptischen Mythologie, die Sie ja ganz gut kennen, schon den Kindern beizubringen, wenn man überhaupt darauf eingehen will.

K. macht Ausführungen über die Erarbeitung der Begriffe: Geometrischer Ort, Kreis, Ellipse, Hyperbel, Lemniskate. (Das soll am nächsten Tage noch fortgesetzt werden.)

Fourteenth Seminar Discussion

U. develops the principles of music teaching in the first and second school years.

Rudolf Steiner: One should not neglect to let the objective, separate from the human being, the instrument, be heard as well. Care must always be taken to ensure that the child is introduced to the solo instrument well before the age of nine, in the second half of the second school year, so that the piano can be added later for those who are suitable. It is essential that we start correctly in this area.

T. continues with interest calculations and transitions to letter calculations. If \(E\) = final capital, \(A\) = initial capital, \(Z\) = interest, \(P\) = percentage, \(T\) = time, then \(E = A + Z\). Furthermore, since \(Z = \frac{A \cdot P \cdot T}{100},\) then \(E = A + \frac{A \cdot P \cdot T}{100}\)

Rudolf Steiner: You can never invest capital in this form today. This form only has a real value if \(T\) is equal to or less than one year. In reality, there are two cases: either you withdraw the interest annually, in which case the initial capital always remains the same, or you leave the interest with the capital, in which case you need to calculate compound interest. If you leave out \(T\), i.e., if you calculate for one year, then it is realistic. It is necessary to give children a realistic picture.

It will be good to work hard to ensure that the transition to letter calculation is actually made. First, the transition from addition to multiplication will be developed, then from subtraction to division.

Rudolf Steiner then explains the transition from number calculation to letter calculation using the following example. First, write down a sum of numbers in which the addends are all unequal:

$$20 = 7 + 5 + 6 + 2$$

Individual addends can also be equal:

$$25=5+5+976$$

And all addends can be the same:

$$18=6+6+6$$

If we now proceed as described yesterday and replace the numbers with letters, I have the sum \(S_1 = a + a + a,\) which is three \(a\), three times \(a=3 \cdot a\); then \(S_2 = a + a + a + a + a,\) five times \(a=5 \cdot a\); then \(S_3 = a + a + a + a + a +a,\) seven times \(a =7 \cdot a\) and so on.

I do this over and over again, I can do it nine times, twenty-one times, twenty-five times. I do it \(m\)-times: S\(S_m = a + a + a + a + a...\) \(m\)-times -( = m \cdot a.\)

This gives me one factor from the uncertainty of the number of addends, while the addend itself is the other factor. In this way, multiplication can be easily developed and understood from addition. This is how you make the transition from specific numbers to algebraic quantities, to \( a \cdot a = a^2, a \cdot a \cdot a = a^3.\)

Similarly, division can be derived from subtraction.

If we subtract \(b\) from a very large number a, we get the remainder \(r_1.\)

$$r_1 = a - b$$

If we subtract 5 again, we get the remainder

$$r_2 = a - b - b = a - 2b$$

Subtracting 5 a third time gives us

$$r_3 = a - b - b - b = a -3b$$

and so on.

We can do this until there is no remainder left of the number \(a\), we can do it \(n\) times:

$$r_n = a - b - b - b - b ... n = a - nb$$

If there is no remainder left, i.e., the last remainder is \(0\), then

$$0 = a - nb.$$

Then a is completely divided, because there is no remainder left, \(a = nb\). I have subtracted \(b\) \(n\) times, divided \(a\) into \(b\) parts, \(\frac{a}{b} = n,\) so that \(a\) is completely consumed. I have found that I can do this \(n\) times and have thus moved from subtraction to division.

One can thus say: Multiplication is a special case of addition, division is a special case of subtraction, except that one does not add or subtract just once, but repeatedly.

The discussion turns to negative and imaginary numbers.

Rudolf Steiner: A negative number is a subtrahend for which there is no longer a minuend; a request for an operation for which there is no longer any material, which cannot be carried out. - Eugen Dühring rejected imaginary numbers as nonsense and said of Gauss's definition of the imaginary that it was foolishness, not reality, a figment of the imagination.

So you always develop multiplication from addition, and then exponentiation from multiplication. And then division from subtraction, and root extraction from division.

add subtract

multiply divide

exponentiate root extract

Only after beginning to calculate with letters, from the eleventh to twelfth year, does one move on to exponentiation and root extraction, because exponentiation of an algebraic polynomial plays a role in root extraction.

In this context, the following should also be covered: gross, net, tare, and packaging calculations.

A question is asked regarding the use of formulas.

Rudolf Steiner: Now the question is whether you would rather not use the formula very often, but instead want to go through the thought process again and again — whereby you can, of course, cultivate your language skills, that is true — or whether you would like to move on to the formula after all. If you do it tactfully so that the formula is well understood, it is also quite useful for practicing linguistic culture to a certain extent.

But from a certain point on, it is also good to make the formula something that the child can feel. To make the formula something that has an inner life, so that, for example, when

$$Z = \frac{K \cdot P \cdot T}{100}$$

the \(T\) becomes larger, the child gets a feeling of the growth of the whole.

This would have said what I wanted to say at this point, namely that concrete numbers should be used on occasions such as interest and percentage calculations in order to make the transition to letter calculations and to develop multiplication, division, exponentiation, and root extraction. These are things that definitely need to be done with children.

Now I would like to ask the question: Do you think it is good to deal with exponentiation and root extraction, root extraction, before you have done letter calculation, or would you do it afterwards?

T.: Exponentiation first, root extraction afterwards.

Rudolf Steiner: So you should assume, and continue to assume in the future, that you will begin with letter calculation as soon as possible, from the eleventh, twelfth year, and only then move on to exponentiation and root extraction. This is because after letter calculation, squaring, cubing, exponentiation, and root extraction can be taught to children in a very simple and economical way, whereas before that, it takes an awful lot of time. You will teach easily and economically if you have first discussed letter calculation with the children.

E. gives a historical elaboration for students in the final grade on the founding and development of cities and speaks of the time of the Magyar invasions of “Germany.”

Rudolf Steiner: I would be very careful not to allow unconsciously confused mental images to arise. Of course, at the time of Henry, the so-called city builder, there was no Germany. One must express it something like this: cities on the Rhine or on the Danube, in places that later became German. Before the 10th century, there were no Magyars to deal with; before that, such invasions involved the Huns and Avars. From the 10th century onwards, one can already speak of “Germany.”

You see, I would, for example—this is a task that is undertaken with pupils in the last grades of elementary school—try to teach the children a concept of chronology. When you say “9th, 10th century,” the mental image becomes too vague. How would you go about giving the children a concrete mental image of time?

You could explain to the child: “If you are this old now, how old are your mother and father? Then how old are your grandfather and grandmother?” — This brings out the whole sequence of generations and you can explain to the child that three generations make up about a hundred years. So in a hundred years there would be three generations. A hundred years ago, the great-grandparents were children. Nine centuries ago, there were not three, but 9:3 = 27 generations. “Suppose,” you say to the child, "you are holding your father's hand, he is holding your grandfather's hand, who is holding your great-grandfather's hand, and so on. If they were standing next to each other, which man would be Henry I, and which man would be facing the Magyars around the year 926? It would be the twenty-seventh man. I would then illustrate this very clearly. After I had given the children a concrete mental image of how long ago that was, I would describe the Magyar migrations to them. I would explain to them how the Magyars invaded Central Europe at that time. How the Magyars broke in with such ferocity that everyone had to flee, except for the small children in their cradles, who had to be carried to the tops of the mountains. How the invading Magyars then burned villages and forests. I would describe the Magyar invasion in great detail.

E. goes on to describe how Heinrich, realizing that he had been able to resist the Magyars in the fortified town of Goslar, decided to found fortified towns, and that this led to the founding of numerous towns.

Rudolf Steiner: Could you not present this account again from a cultural-historical perspective? For it is a somewhat monarchically embellished historical legend that Henry founded these cities. All these cities of the 10th century already existed in their basic form, in the markets. Their expansion was only promoted by the fact that people who lived in the vicinity of these towns joined together to gain easier defense against the advancing Magyars, thus strengthening these places. It was more economic reasons that were at work and led to the formation of towns. Henry did not do very much to contribute to this.

I would just ask you to present all this in a very vivid way, to proceed in a very lively manner, so that the children can form vivid images in their minds and can really grasp everything. You must appeal to their imagination and use things such as those I have shown you to make the period concrete. It is of no real use to know in which year, for example, the Battle of Zama took place, and so on, but if you imagine, if you know that Charlemagne goes back thirty generations, if you were to join hands across the generations, then you would get a vivid, concrete mental image of time. That brings that time much closer — indeed, it comes much closer! — when you know that Charlemagne can be traced back to your thirtieth ancestor.

T.: Wouldn't it be good to point out the very different ways of thinking and feeling of people in these periods when describing such cultures?

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, I have always pointed this out in my lectures and elsewhere. Above all, you should make the great upheaval around the 15th century, the completely different sensibilities, feelings, and ways of thinking of people before and after this time, very clear. For example, Lamprecht, whom I do not particularly recommend, endeavors to establish a completely different way of thinking, feeling, and sensing among people before this period. — The documents have not yet been used for this purpose.

If you want to familiarize yourself a little with cultural-historical considerations, you must above all be able to develop a certain intuition, and if you have this for further and narrower things that the authors tell you, for more narrow-minded and somewhat more broad-minded things, then you can gain more accurate mental images of cultural history.

In response to a request, Rudolf Steiner recommends the following purchases for the teachers' library:

Buckle, History of Civilization in England.

Lecky, History of the Enlightenment in Europe. These can be used to train the method for cultural-historical observations. The older parts of Lamprecht would be suitable, but much of it is flawed and subjective.If you have not acquired this instinct for the real driving forces of cultural history, then you run the risk of, with truly Wildenbruchian stupidity and Wildenbruchian dilettantism, considering, for example, the imperial and royal dramas and such family squabbles as those between Louis the Pious and his sons to be essential events in cultural history.

Gustav Freytag's “Pictures from Germany's Past” are quite good, but one must not allow oneself to be overly influenced by the cozy atmosphere of a historical perspective written for aunts. Today, we must break away from the style of thinking and feeling that was so prevalent among the writers of mid-19th century border literature, such as Gustav Freytag, Julian Schmidt, and so on. Lassalle called him a “Schmulian Jew”; in Lassalle's mouth, this did not sound anti-Semitic.

The question is asked about Houston Stewart Chamberlain's “Fundamentals of the 19th Century.”

Rudolf Steiner: With Chamberlain, too, one must develop a good instinct, because a quarter of what he writes is witty, and three quarters is wild, unhealthy stuff. There is a great deal of very good stuff in his work, but one must review everything oneself and develop one's own judgment. The cultural-historical descriptions are better in Buckle and Lecky. Chamberlain is more of a tuxedo wearer. He is a somewhat vain gentleman who cannot exactly be considered an authority, but who has nevertheless made some correct observations. His end was not a happy one, I mean the lawsuit with the Frankfurter Zeitung.

Kautsky's writings are mentioned.

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, if you generally assume the opposite of what he shows there. You can get good and interesting factual material from modern socialists if you don't let yourself be numbed by the theories that permeate their descriptions.

Mehring also presents a peculiar picture, as he first rails against the Social Democrats in his book, his history of social democracy, as long as he was a liberal; then afterwards, when he had joined the Social Democrats, he simply changes his tune to rail against the liberals.

M. provides an introduction to the basic concepts of mathematical geography for thirteenth-year students, observations at sunrise and on the sun's path.

Rudolf Steiner: Once you have sent the children outside, you can later turn this into a drawing and see that there is a certain parallelism between the drawing and what the children saw outside. It is only advisable not to give too much of this linearity at once. It is very important to teach these things to the children, but if you summarize too much, you will reach a point where the children can no longer grasp it. You can incorporate it into geography and geometry. The approximate conclusion of such explanations would be to develop the concept of the ecliptic and coordinates. A, explain the same topic, sunrise and sunset, to younger children and try to clarify the course of the sun and the planets by means of a schematic drawing.

Rudolf Steiner: Well, this view will become less and less important because what has been assumed about these movements is not entirely correct. In reality, we are dealing with a movement like this (Rudolf Steiner draws on the blackboard):

For example (1st position), here is the sun; there is Saturn, Jupiter, Mars, and there is Venus, Mercury, Earth. Now they all move in the indicated direction (helical line) one after the other, so that when the sun has moved over there (2nd position), Saturn, Jupiter, Mars are here, Venus, Mercury, and Earth are there. And now the sun continues to turn and goes there (3rd position). This creates the illusion that the Earth is revolving around the sun. In reality, the sun goes ahead and the Earth always creeps along behind.

B. gives an account from ancient Egyptian culture.

Rudolf Steiner: Above all, one would have to move on to presenting what is the completely different principle of imitation. The ancient Egyptians had the shortcoming of seeing without perspective. The ancient Egyptian painted the face in profile and the rest of the body en face. This peculiarity of perception would have to be taught to children.

Then we would have to establish the connection between Egyptian drawing and painting and the natural history principle they had, whereby they depicted humans with animal heads and so on. Even in ancient times, the comparison of humans with animals was taken very far. One could then teach the child what is inherent in every human mind and what the child still sees to some extent today. The Egyptians still perceived this relationship between human physiognomy and animals. They were still at this childlike stage of perception.

During the discussion of the pyramids, B. asks what one should actually tell children about them.

Rudolf Steiner: It is, of course, extremely important to gradually try to replace what is wrong with what is right, even for children. In fact, the pyramids were places of initiation. And so we come to the point where we teach children about the higher Egyptian teachings, which were at the same time an initiation. We must tell them something about what went on there. Religious acts were performed there, as they are performed in churches today, but at the same time they led to the recognition of the universe. The ancient Egyptians learned in this way, as they were shown in solemn ceremonies what takes place in the universe and in the development of humanity. Religious practice and teaching were one and the same. It was so that teaching and religious ceremony actually coincided.

B. describes the work on the pyramids and obelisks and says that one must assume that several million people would have been needed to procure, work, and install the huge blocks. One must ask oneself how it was even possible to move and stack the large, heavy limestone and granite blocks with the technical aids available at that time.

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, but you will only give the children a completely accurate mental image if you tell them that if people worked with today's physical strength, two and a half times as many people would have been needed. But in reality, the Egyptians had two and a half times as much physical strength as people today, at least those who worked on the pyramids and so on. Of course, there were also weaker people.

B. asks whether mythology should also be addressed.

Rudolf Steiner: If you cannot present Egyptian mythology in its true form, then you must simply leave it out. But if you can present Egyptian mythology in its true form, then you should do so. In Waldorf schools, it would be quite good to teach children the correct concepts of Egyptian mythology, which you know very well, if you want to address it at all.

K. elaborates on the development of the concepts: geometric locus, circle, ellipse, hyperbola, lemniscate. (This will be continued the next day.)