Discussions with Teachers

GA 295

6 September 1919, Stuttgart

Translated by Helen Fox

Discussion Fifteen

Speech Exercises:

Slinging slanging a swindler

the wounding fooled a victor vexed

The wounding fooled a swindler

slinging slanging vexedMarch smarten ten

clap rigging rockets

Crackling plopping lynxes

fling from forward forthCrackling plopping lynxes

fling from forward forth

March smarten ten

clap rigging rockets

RUDOLF STEINER: With this exercise you should share the recitation, like a relay race, coming in quickly one after the other. One begins, points to another to carry on, and so on.

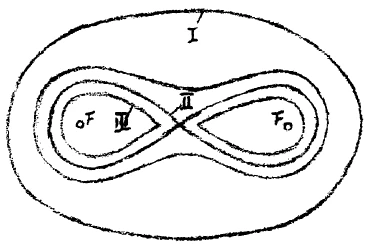

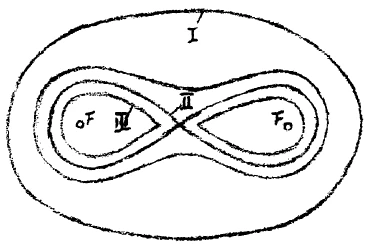

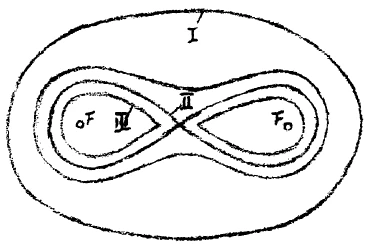

Someone spoke about the ellipse, the hyperbola, the circle, the lemniscate, and the conception of geometrical loci. At the same time he mentioned how the lemniscate (Cassini curve) can take on the form III, in the diagram, where the one branch of the curve leaves space and enters space again as the other branch.

RUDOLF STEINER: This has an inner organic correlate. The two parts have the same relation to each other as the pineal gland to the heart. The one branch is situated in the head—the pineal gland, the other lies in the breast—the heart. Only the pineal gland is more weakly developed, the heart is stronger.

Someone spoke on a historical theme—the migrations of various peoples.

RUDOLF STEINER: The causes assigned to such migrations very often depend on the explanations of historical facts. As to the actual migrations—for example, the march of the Goths—at the root of the matter, you will find that the Romans had the money and the Germanic peoples had none, and at every frontier there was a tendency among the Germanic peoples to try to acquire Roman money one way or another. Because of this, they became mercenaries and the like. Whole legions of the Germanic peoples entered into Roman hire. The migration of the people was an economic matter. This was the only thing that made the spread of Christianity possible, but the migrations as such began, nevertheless, with the avarice of the Germanic peoples who wanted to acquire Roman money. The Romans of course were also impoverished by this. This was already the case as early as the march of the Cimbri. The Cimbri were told that the Romans had money, whereas they themselves were poor. This had a powerful effect on the Cimbri. “We want gold,” they cried, “Roman gold!”

There are still various race strata—even Celtic traces. Today there are definite echoes of the Celtic language—for example, at the sources of the Danube, Brig and Breg, Brigach, and Brege, and wherever you find the suffix ach in the place names such as Unterach, Dornach, and so on. Ach comes from a word meaning a “small stream” (related to aqua), and points to a Celtic origin. “Ill,” too, and other syllables remind us of the old Celtic language. The Germanic language subsequently overlaid the Celtic.

[Rudolf Steiner referred to the contrast between Arians and Athanasians.1Athanasian refers to the doctrine of Saint Athanasius, or Athanasius the Great (c. 293–373), who was a Greek theologian and prelate in Egypt. Throughout his life he opposed Arianism and became known as the “Father of Orthodoxy.” He was exiled three times by Roman emperors for his stand; he wrote Four Orations against the Arians but not the Athanasian Creed (written after the fifth century), which espouses his teachings on the Trinity. The Arian doctrine, on the other hand, has to do with Arius (c. 250–336), also a Greek ecclesiastic in Alexandria, who taught a Neoplatonic doctrine that God is alone and unknowable, the creator of every being, including the Christ. Emperor Constantine I formed the Council of Nicaea in 325 to declare Arianism a heresy.]

There is something connected with the history of these migrations that is very important to explain to the children—that is, that it was very different for the migrating peoples to come into districts that were already fully developed agriculturally. In the case of the Germanic peoples, such as the Goths in Spain and Italy, they found that all the land was being cultivated already. The Goths and other ethnic groups arrived but soon disappeared. They became absorbed by the other nations who were there before them. The Franks, on the other hand, preferred to go to the West, and arrived in districts not yet fully claimed for agriculture, and they continued to exist as Franks. Nothing remained of the Goths who settled where the land was all already owned. The Franks were able to preserve their nationality because they had migrated into untilled areas. That is a very important historical law. You can refer to this law again later in relation to the configuration of North America. There, it is true that the Red Indians were almost exterminated, but it was also true, nevertheless, that people could migrate into uncultivated districts.

It is also important to explain the difference between such things as, for example, the France of Charles the Great and the state of a later time. If you are unaware of this difference, you cannot cross the Rubicon of the fifteenth century. The empire of Charles the Great was not yet a state. How was it for the Merovingians? Initially they were no more than large-scale landowners. The only thing that mattered to them was civil law. As time passed, this product of the old Germanic conditions of ownership became the Roman idea of “rights,” whereby those who were merely administrators gradually acquired power. And so, by degrees, property went to the administrative authorities, the public officials, and the state arose only when these authorities became the ruling power later. The state, therefore, originated through the claims of the administration. The “count nobility” arose as the antithesis of “prince nobility.” The word Graf (count) has the same origin as “graphologist” or “scribe.” It is derived from graphein, to write. The “count” is the Roman scribe, the administrator, whereas the “prince nobility,” originally the warrior nobility, is still associated with bravery, heroism, and similar qualities. The prince (Fürst) is “first,” the foremost one. And so this transition from Fürst to Graf (prince to count) marked the rise of the concept of “state.” This can of course be made very clear by using examples such as these.

Someone described how he would introduce the spread of Christianity among the Germanic peoples.

RUDOLF STEINER: Arian Christianity, expressed in practical life, is very similar to later Protestantism, except that it was less abstract and more concrete. During the first and second centuries the Mithras cult was very widespread among Roman soldiers on the Rhine and the Danube, especially among the officers. In what is now Alsace and elsewhere, Thor, Wotan, and Saxnot were worshipped as the three principal gods of the ancient Germanic people, and the old Germanic religious rites and ceremonies were used.2This is a reference to Steiner’s lectures on the history of the Middle Ages, given in the Workers’ College in Berlin between October 18 and December 20, 1904 Geschichte des Mittelalters bis zu den großen Erfindungen und Entdeckungen (GA 51).

We could describe many scenes that demonstrate how the little churches were built in Alsace and the Black Forest by the Roman clerics. “We want to do this or that for Odin” sang the men. The women sang, “Christ came for those who do nothing by themselves.” This trick was actually used to spread Christianity—that by doing nothing one could achieve salvation.

Eiche (the oak), in the old Germanic cult-language, designates the priest of Donar. During the time of Boniface it was still considered very important that the formulas were still known. Boniface knew how to gain possession of some of these formulas; he knew the magic word, but the priest of Donar no longer knew it. Boniface, through his higher power, felled the priest of Donar—the “Donar-oak”—by means of his “axe,” the magic word. The priest died of grief; he perished through the “fire from Heaven.” These are images of imagination. Several generations later this was all transformed into the well-known picture.

You must learn to “read” pictures of this kind, and thus through learning to teach, and through teaching to learn.

Boniface romanized Germanic Christianity. Charles the Great’s biography was written by Eginhard, and Eginhard is a flatterer.

Music teaching was spoken about.

RUDOLF STEINER: Those who are less advanced in music should at least be present when you teach the more advanced students, even if they do not take part and merely listen. You can always separate them later as a last resort. There will be many other subjects in which the situation will be just as bad, in which it will be impossible for the more advanced students to work with those who are backward. This will not happen as often if we keep trying to find the right methods. But due to a variety of circumstances, such things are not obvious now. When you really teach according to our principles you will discover that the difficulties, usually unnoticed, will appear not only in music lessons, but in other subjects as well—for example, in drawing and painting. You will find it very difficult to help some of the children in artistic work, and also in the plastic arts, in modeling.

Here, too, you should try not to be too quick to separate the children, but try to wait until they can no longer work together.

,em>Someone spoke about teaching poetry in French and English [foreign language] lessons.

RUDOLF STEINER: We must stay strictly with speaking a certain amount of English and French with the children right from the beginning—not according to old-fashioned methods, but so that they learn to appreciate both languages and get a feeling for the right expressions in each.

When a student in the second, third, or fourth grade breaks down over recitation, you must help in a kind and gentle way, so that the child trusts you and doesn’t lose courage. The child’s good will must also be aroused for such tasks.

The lyric-epic element in poetry is suitable for children between twelve and fifteen years of age, for example, ballads or outstanding passages from historical writings, good prose extracts, and selected scenes from plays.

Then in the fourth grade we begin Latin, and in the sixth grade Greek for those who want it, and in this way they can get a three-year course. If we could enlarge the school we would begin Latin and Greek together. We shall have to see how we can manage to relieve children who are learning Latin and Greek of some of their German. This can be done very easily, because much of the grammar can be dealt with in Latin and Greek, which would otherwise come into the German lessons. There can also be various other ways.

C was pronounced “K” in old Latin; and in medieval Latin, which was a spoken language, it was C as in “cease.” The ancient Romans had many dialects in their empire. We can call Cicero “Sisero” because in the Middle Ages it was still pronounced like that. We can’t speak of what is “right” in pronunciation because it is something quite conventional. The method of teaching classical languages can be similarly constructed; here, however, with the exception of what I referred to this morning,3See morning lecture pp. 189–190. it is usually possible to use the normal contemporary curricula, because they originated in the best educational periods of the Middle Ages, and they still contain much that has pedagogical value for teaching Latin and Greek. Today’s curricula still copy from the old, which makes good sense.

You should avoid one thing, however: the use of the little doggerel verses composed for memorizing the rules of grammar. To the people of today they seem rather childish, and when they are translated into German they are just too clumsy. You must try to avoid these, but otherwise such methods are not at all bad.

Sculpting should begin before the ninth year. With sculpture too, you should work from the forms—spheres first, then other forms, and so on.

Someone asked whether reports should be provided.

RUDOLF STEINER: As long as children remain in the same school, what is the purpose of writing reports? Provide them when they leave school. Constant reports are not vitally important to education. Remarks about various individual subjects could be given freely and without any specific form.

Necessary communication with the parents is in some cases also a kind of grading, but that cannot be entirely avoided. It may also prove necessary, for example, for a pupil to stay in the same grade and repeat the year’s work (something we should naturally handle somewhat differently than is usual); this may be necessary occasionally, but in our way of teaching it should be avoided whenever possible. Let’s make it our practice to correct our students so that they are really helped by the correction.

In arithmetic, for example, if we do not stress what the child cannot do, but instead work with the student so that in the end the child can do it—following the opposite of the principle used until now—then “being unable” to do something will not play the large role it now does. Thus in our whole teaching, the passion for passing judgment that teachers acquire by marking grades for the children every day in a notebook should be transformed into an effort to help the children over and over, every moment. Do away with all your grades and placements. If there is something that the student cannot do, the teachers should give themselves the bad mark as well as the pupil, because they have not yet succeeded in teaching the student how to do it.

Reports have a place, as I have said, as communication with the parents and to meet the demand of the outside world; in this sense we must follow the usual custom. I don’t need to enlarge on this, but in school we must make it felt that reports are very insignificant to us. We must spread this feeling throughout the school so that it becomes a kind of moral atmosphere.

You now have a picture of the school, because we have been through the whole range of subjects, with one exception; we still have to speak about how to incorporate technical subjects into school. We have not spoken of this yet, merely because there was no one there to do the work. I refer to needlework, which must still be included in some way. This must be considered, but until now there was no one who could do it. Of course it will also be necessary to consider the practical organization of the school; I must speak with you about who should teach the various classes, whether certain lessons should be given in the morning or afternoon, and so on. This must be discussed before we begin teaching. Tomorrow will be the opening festival, and then we will find time, either tomorrow or the day after, to discuss what remains concerning the practical distribution of work. We will have a final conference for this purpose where those most intimately concerned will be present. I shall then also have more to say about the opening ceremony.

Fünfzehnte Seminarbesprechung

Sprechübungen:

Schlinge Schlange geschwinde

Gewundene Fundewecken wegGewundene Fundewecken

Geschwinde schlinge Schlange wegMarsch schmachtender

Klappriger Racker

Krackle plappernd linkisch

Flink von vorne fortKrackle plappernd linkisch

Flink von vorne fort

Marsch schmachtender

Klappriger Racker

Rudolf Steiner: Das ist zum Einsetzen gut. Hinweisen auf den, der fortsetzen soll; dann setzt der nächste oder ein anderer fort.

K. spricht über Ellipse, Hyperbel, Kreis, Lemniskate und den Begriff des geometrischen Ortes. Er erwähnt dabei, wie die Lemniskate (Cassinische Kurve) eine Form III annehmen kann, bei der der eine Ast der Kurve den Raum verläßt und als der andere Ast wieder in ihn eintritt.

Rudolf Steiner: Das hat ein inneres organisches Korrelat. Die beiden Stücke verhalten sich zueinander wie Zirbeldrüse und Herz. Der eine Ast liegt im Kopf, die Zirbeldrüse, der andere Ast liegt in der Brust, das Herz. Nur ist das eine, die Zirbeldrüse, schwächer ausgebildet, das Herz stärker.

D. spricht über ein geschichtliches Thema, über die Völkerwanderung.

Rudolf Steiner macht dazu mehrere Zwischenbemerkungen: Was als Gründe für die Völkerwanderung angeführt wird, beruht sehr häufig auf geschichtlichen Konstruktionen. Das Wesentliche ist, wenn man den Dingen zu Leibe geht, bei der eigentlichen Völkerwanderung, wo die Goten und so weiter vorrücken, daß die Römer das Geld haben, und die Germanen kein Geld haben, und daß die Tendenz besteht, daß überall da, wo eine Grenze ist, die Germanen in irgendeiner Weise sich das römische Geld aneignen wollen. Daher werden sie Söldner und alles mögliche. Es sind ja ganze Legionen von Germanen in den römischen Sold eingetreten. Es ist die Völkerwanderung eine wirtschaftlich-finanzielle Frage. Erst auf dieser Grundlage konnte dann die Ausbreitung des Christentums vor sich gehen. Die Völkerwanderung als solche rührt aber von der Habgier der Germanen her, die das Geld der Römer haben wollten. Die Römer wurden auch arm dabei! Auch schon beim Cimbernzug war es so. Den Cimbern wurde gesagt: Die Römer haben Gold! — während sie selbst arm waren. Das wirkte auf die Cimbern sehr stark. Sie wollen Gold holen. Römisches Gold!

Es sind verschiedene Völkerschichten da, auch noch keltische Überreste. Sie finden heute noch deutliche Sprachanklänge an die keltische Sprache, zum Beispiel bei den Quellflüssen der Donau, Brig und Breg, Brigach und Brege. Dann überall, wo in den Ortsnamen «-ach» vorhanden ist, zum Beispiel Unterach, Dornach und so weiter. «Ach» kommt von Wässerchen her, von aqua, weist auf Keltisches zurück. Auch «Ill» und dergleichen erinnert ans alte Keltische. Über das Keltische schichtet sich dann das Germanische. - Gegensatz von Arianern und Athanasianern.

Sehr wichtig ist, daß Sie den Kindern klarmachen müssen, daß ein großer Unterschied besteht - das ist gerade an der Völkerwanderung ersichtlich -, ob, wie zum Beispiel in Spanien und Italien, die germanischen Völker, wie die Goten, in schon der Agrikultur nach völlig in Anspruch genommene Gebiete einziehen. Hier wurde alles besessen. Da ziehen die gotischen und andere Völker ein. Die verschwinden. Die gehen also auf in den anderen Völkern, die schon da waren. - Nach Westen ziehen die Franken vor. Die kommen in Gegenden, die der Agrikultur nach noch nicht vollständig besetzt sind. Die erhalten sich. Daher hat sich von den Goten nichts erhalten, die eben in Gegenden eingezogen sind, wo der Boden schon ganz in Besitz genommen war. Von den Franken hat sich alles erhalten, weil sie in noch brachliegende Gegenden eingezogen sind. Das ist ein geschichtliches Gesetz, das sehr wichtig ist. Später kann der Hinweis wiederholt werden bei der Konfiguration von Nordamerika, wo allerdings die Indianer ausgerottet worden sind, aber doch das bestand, daß in Brachgegenden eingewandert werden konnte.

Es handelt sich auch darum, daß Sie dann klarmachen, welches der Unterschied ist zwischen so etwas, wie zum Beispiel das Frankenreich Karls desGroßen war, und einem späteren Staat. Wenn Sie diesen Unterschied nicht kennen, kommen Sie nicht über den Rubikon des 15. Jahrhunderts hinweg. Das Reich Karls des Großen ist noch kein Staat. Wie ist es bei den Merowingern? Sie sind eigentlich zunächst nichts anderes als Großgrundbesitzer. Und bei ihnen gilt lediglich nur das Privatrecht. Und immer mehr geht dann dasjenige, was aus den alten germanischen Großgrundbesitz-Verhältnissen stammt, über in das römische Recht, wo derjenige, der bloß die Ämter verwaltet, nach und nach die Macht bekommt. So geht allmählich der Besitz über an die Verwaltung, an die Beamten, und indem dann später die Verwaltung die eigentliche Herrschermacht wird, entsteht erst der Staat. Der Staat entsteht also durch die Inanspruchnahme der Verwaltung. Es entsteht der Grafenadel im Gegensatz zum Fürstenadel. «Graf» hat denselben Ursprung wie Graphologe: es kommt her von graphein, schreiben. «Graf» heißt Schreiber. Der Graf ist der römische Schreiber, der Verwalter, während der Fürstenadel als alter Kriegeradel noch mit Tapferkeit und Heldenmut und dergleichen zusammenhängt. Der «Fürst» ist der Erste, der Vorderste. So ist also mit dem Übergang vom Fürsten zum Grafen das staatliche Prinzip entstanden. Das kann man natürlich an diesen Dingen ganz gut anschaulich machen.

L. führt aus, wie er die Ausbreitung des Christentums bei den Germanen an die Kinder heranbringen würde.

Rudolf Steiner: Das arianische Christentum hat im praktischen Ausleben etwas sehr stark dem späteren Protestantismus ähnliches, es war aber weniger abstrakt, war noch konkreter.

Im 1. und 2. Jahrhundert war unter den römischen Soldaten an Rhein und Donau sehr stark der Mithrasdienst verbreitet, namentlich unter den Offizieren. — Thor, Wotan, Saxnot wurden im heutigen EIsaß und überall bis ins 6., 7., 8. Jahrhundert als die alten germanischen Volksgötter, als die drei wesentlichen Hauptgötter verehrt mit germanischen religiösen Gebräuchen.

Man kann zahlreiche Szenen schildern, wie im Elsaß, im Schwarzwald die Kirchlein durch die römischen Kleriker gebaut werden. «Wir wollen dem Wotan das und das tun», sangen die Männer. Die Frauen sangen: «Der Christus ist für die gekommen, die nichts tun von sich aus.» Dieser Trick wurde schon benützt bei der Ausbreitung des Christentums, daß man nichts zu tun hatte, um selig zu werden.

«Eiche» ist in der altgermanischen Kultsprache die Bezeichnung für den Priester des Donar. In der Zeit, als Bonifatius wirkte, kam noch stark in Betracht, ob man noch die Formeln wußte. Bonifatius wußte sich in Besitz gewisser Formeln zu setzen. Er wußte das Zauberwort, der Donarpriester wußte es nicht mehr. Bonifatius hat durch seine höhere Macht, durch die «Axt», das Zauberwort, den Priester des Donar, die «Donar-Eiche», gefällt. Der Priester starb vor Gram; er ging zugrunde «durch das Feuer des Himmels». Das sind Imaginationsbilder! Nach einigen Generationen ist das in das bekannte Bild umgeformt worden.

Solche imaginativen Bilder müssen Sie lesen lernen. Und so lernend lehren, lehrend lernen.

Bonifatius hat das germanische Christentum verrömischt.

Karls des Großen Leben hat Eginhard beschrieben. Eginhard ist ein Schmeichler.

U. spricht über den musikalischen Unterricht.

Rudolf Steiner: Die im Musikunterricht weniger Fortgeschrittenen sollte man wenigstens zu den Übungen der Fortgeschrittenen dazunehmen, wenn sie auch untätig dabei sind und nur zuhören. Wenn alles nichts nützt, kann man sie immer noch absondern. Es wird übrigens noch viele Gegenstände geben, wo ähnliche Übelstände eintreten, daß also die Fortgeschrittenen und die Zurückgebliebenen nicht in Einklang zu bringen sind. Das wird sich weniger einstellen, wenn man für die richtigen Methoden sorgt. Heute wird das nur durch allerlei Verhältnisse kaschiert. Wenn Sie nach unseren Gesichtspunkten praktisch unterrichten werden, werden Sie die Schwierigkeiten, die Sie sonst gar nicht bemerken, auch mit anderen Gegenständen bekommen als nur mit der Musik. Zum Beispiel beim Zeichnen und Malen. Sie kriegen Kinder, die Sie im Künstlerischen sehr schwer vorwärtsbringen können, auch im Plastisch-Künstlerischen, im Bildnerisch-Künstlerischen. Da muß man auch versuchen, nicht zu früh an die Trennung der Kinder zu gehen, sondern erst, wenn es gar nicht mehr geht.

N. spricht über die Behandlung des Poetischen im französischen und englischen Unterricht.

Rudolf Steiner: Wir halten durchaus daran fest, das Englische und Französische ganz von Anfang an mit den Kindern in mäßiger Weise zu treiben. Nicht gouvernantenhaft, sondern so, daß sie die beiden Sprachen richtig schätzen lernen, und daß sie ein Gefühl bekommen für den richtigen Ausdruck in den beiden Sprachen.

Wenn ein Schüler in der zweiten bis vierten Klasse beim Rezitieren steckenbleibt, muß man ihm gutmütig und in aller Sanftheit nachhelfen, damit er zutraulich wird und nicht den Mut verliert. Man muß da den guten Willen auch für das Werk nehmen.

Für die zwölf- bis fünfzehnjährigen Kinder ist das lyrisch-epische Element geeignet, Balladen; auch markante historische Darstellung, gute Kunstprosa und einzelne dramatische Szenen.

Und dann fangen wir mit dem vierten Schuljahr mit der lateinischen Sprache an, und im sechsten Schuljahr mit dem Griechischen, für diejenigen Kinder, die es mitnehmen wollen, damit wir es drei Jahre lang treiben können. Wenn wir die Schule ausbauen könnten, würden wir mit dem Lateinischen und dem Griechischen zugleich beginnen. Wir müssen dann Rat schaffen dafür, daß diejenigen Kinder, die Lateinisch und Griechisch mitnehmen, im Deutschen etwas entlastet werden. Das kann sehr gut geschehen, weil viel Grammatikalisches dann im Griechischen und Lateinischen besorgt wird, was sonst im Deutschen besorgt werden muß. Und auch noch manches andere wird erspart werden können.

Man sprach C wie K im alten Latein; das mittelalterliche, das ein gesprochenes Latein war, hatte C. Im alten Römerland wurden viele Dialekte gesprochen. Man kann «Cicero» sagen, weil das im Mittelalter noch so gesprochen wurde. Man kann von etwas «Richtigem» in der Sprache nicht reden, da es etwas Konventionelles ist.

Die Methodik des altsprachlichen Unterrichts ist auf derselben Linie aufzubauen, nur ist darauf Bedacht zu nehmen, daß man beim altsprachlichen Unterricht, mit Ausnahme dessen, was ich heute morgen gesagt habe, im wesentlichen den Lehrplan benützen kann. Denn er stammt noch aus den besten pädagogischen Zeiten des Mittelalters her. Es ist da noch vieles, was sich pädagogisch noch ein wenig zeigen kann, was sich für die Methodik des Griechischen und Lateinischen findet. Da schreiben die Lehrpläne noch immer das nach, was man früher getan hat, und das ist nicht ganz unvernünftig. Die Abfassung der Schulbücher ist etwas, was man heute nicht mehr benützen kann, insofern man die etwas holperigen Memorierregeln doch heute eigentlich unterlassen sollte. Die kommen dem heutigen Menschen etwas kindlich vor, und sie sind ja, indem sie ins Deutsche übertragen sind, auch etwas zu holperig. Das wird man versuchen zu vermeiden, sonst aber ist die Methodik nicht so schlecht.

Plastisches soll vor dem neunten Jahre beginnen, Kugeln, dann anderes und so weiter. Auch beim Plastischen soll man ganz aus den Formen heraus arbeiten.

R. fragt, ob man Zeugnisse geben soll.

Rudolf Steiner: Solange die Kinder in derselben Schule sind, wozu soll man da Zeugnisse geben? Geben Sie sie dann, wenn die Kinder abgehen. Es ist ja nicht von einer tiefgehenden pädagogischen Bedeutung, neue Zensuren auszusinnen. Zensuren unter die einzelnen Arbeiten wären ganz frei zu geben, ohne bestimmtes Schema.

Die Mitteilung an die Eltern ist ja unter Umständen auch etwas wie eine Zensur, aber das wird sich nicht ganz vermeiden lassen. Wie es auch zum Beispiel als notwendig sich herausstellen kann — was wir natürlich mit einer gewissen anderen Note behandeln würden, als es gewöhnlich behandelt wird -, daß ein Schüler länger auf einer Stufe bleiben muß; das müssen wir natürlich dann auch machen. Wir werden es ja tunlichst vermeiden können durch unsere Methode. Denn wenn wir den praktischen Grundsatz verfolgen, womöglich so zu verbessern, daß der Schüler durch die Verbesserung etwas hat - also wenn wir ihn rechnen lassen, weniger Wert darauf legen, daß er etwas nicht kann im Rechnen, sondern darauf, daß wir ihn dazu bringen, daß er es nachher kann -, wenn wir also das dem bisherigen ganz entgegengesetzte Prinzip verfolgen, dann wird das Nichtkönnen nicht mehr eine so große Rolle spielen, als es jetzt spielt. Es würde also im ganzen Unterricht die Beurteilungssucht, die der Lehrer sich dadurch anerzieht, daß er jeden Tag Noten ins Notizbuch notiert, umgedreht werden in den Versuch, in jedem Momente dem Schüler immer wieder und wiederum zu helfen und gar keine Beurteilung an die Stelle zu setzen. Der Lehrer müßte sich ebenso eine schlechte Note geben wie dem Schüler, wenn der Schüler etwas nicht kann, weil es ihm dann nur noch nicht gelungen ist, es ihm beizubringen.

Als Mitteilung an die Eltern und als von der Außenwelt Gefordertes können wir, wie gesagt, Zeugnisse figurieren lassen. Da müssen wir uns schon an das halten, was üblich ist. Aber in der Schule müssen wir durchaus die Stimmung geltend machen, daß das eben für uns — das brauchen wir ja nicht besonders auseinanderzusetzen — nicht in erster Linie eine Bedeutung hat. Diese Stimmung müssen wir verbreiten wie eine moralische Atmosphäre.

Nun ist alles zur Geltung gekommen bei uns, so daß Sie eine Vorstellung bekommen, mit Ausnahme dessen, was dann in irgendeiner Form noch in bezug auf die technische Eingliederung in die Schule wird zur Sprache kommen müssen, wozu wir noch nicht gekommen sind, weil einfach die Besetzung nicht da war: das sind die weiblichen Handarbeiten. Das ist etwas, was in irgendeiner Weise noch eingegliedert werden muß. Darauf muß gesehen werden, aber es war niemand da, der dafür in Betracht gekommen wäre.

Nun wird es natürlich notwendig sein, daß wir auch die Schule in ihrer praktischen Gliederung besprechen. Daß mit Ihnen besprochen wird, in welchen Klassen Sie zu unterrichten haben und so weiter, wie wir die Sachen auf Vor- und Nachmittag verlegen und so weiter. Das muß besprochen werden, bevor wir den Unterricht beginnen. Morgen wird ja die feierliche Eröffnung sein, und dann werden wir schon Gelegenheit nehmen, morgen oder übermorgen das, was noch für die technische Einteilung nötig ist, zu besprechen. Wir werden darüber noch eine entscheidende Konferenz im engsten Kreise haben. Ich werde dann auch noch einige Worte über die Schulweihe zu sagen haben.

Fifteenth Seminar Discussion

Speech exercises:

Swiftly sling the snake

Winding Fundewecken awayWinding Fundewecken

Swiftly sling snake awayMarch languishing

Rattling rascal

Crackle babbling awkwardly

Quickly away from the frontCrackle babbling awkwardly

Quickly away from the front

March languishing

Rickety rascal

Rudolf Steiner: That's good for starting. Point out the one who should continue; then the next or another continues.

K. talks about ellipses, hyperbolas, circles, lemniscates, and the concept of geometric location. He mentions how the lemniscate (Cassini curve) can take on a form III, in which one branch of the curve leaves space and re-enters it as the other branch.

Rudolf Steiner: This has an inner organic correlate. The two parts relate to each other like the pineal gland and the heart. One branch is located in the head, the pineal gland, the other branch is located in the chest, the heart. Only one, the pineal gland, is weaker, the heart stronger.

D. talks about a historical topic, the migration of peoples.

Rudolf Steiner makes several interjections on this subject: The reasons given for the migration of peoples are very often based on historical constructions. The essential point, when one gets to the heart of the matter, is that during the actual migration of peoples, when the Goths and so on advanced, the Romans had money and the Germanic peoples had no money, and there was a tendency for the Germanic peoples to want to acquire Roman money in some way wherever there was a border. That is why they became mercenaries and all sorts of other things. Entire legions of Germanic tribesmen entered the Roman army. The migration of peoples is an economic and financial issue. It was only on this basis that the spread of Christianity could then take place. However, the migration of peoples as such stems from the greed of the Germanic tribes, who wanted the money of the Romans. The Romans also became poor in the process! It was the same with the Cimbrian migration. The Cimbri were told: The Romans have gold! — while they themselves were poor. This had a strong effect on the Cimbri. They wanted to get gold. Roman gold!

There are different ethnic groups there, including Celtic remnants. Even today, you can still find clear echoes of the Celtic language, for example in the source rivers of the Danube, Brig and Breg, Brigach and Brege. Then everywhere where “-ach” is present in place names, for example Unterach, Dornach, and so on. “Ach” comes from ‘Wässerchen’ (little water), from “aqua,” and refers back to Celtic. “Ill” and similar words also remind us of ancient Celtic. Germanic then layers itself over Celtic. - Contrast between Arians and Athanasians.

It is very important that you make it clear to the children that there is a big difference – this is particularly evident in the migration of peoples – between, for example, Spain and Italy, where Germanic peoples such as the Goths moved into areas that were already fully occupied by agriculture. Everything here was owned. Then the Goths and other peoples moved in. They disappeared. So they assimilated into the other peoples who were already there. The Franks moved westward. They came to areas that were not yet fully occupied by agriculture. They preserved themselves. That is why nothing has survived of the Goths, who moved into areas where the land was already completely occupied. Everything about the Franks has been preserved because they moved into areas that were still uncultivated. This is a very important historical law. Later, this point can be repeated in the configuration of North America, where the Indians were exterminated, but where it was still possible to migrate to uncultivated areas.

It is also important that you clarify the difference between something like Charlemagne's Frankish Empire and a later state. If you do not know this difference, you will not be able to cross the Rubicon of the 15th century. Charlemagne's empire is not yet a state. What about the Merovingians? They are actually nothing more than large landowners at first. And only private law applies to them. And then, more and more, what originated in the old Germanic large landownership conditions is transferred to Roman law, where those who merely administer the offices gradually gain power. Thus, ownership gradually passes to the administration, to the officials, and when the administration later becomes the actual ruling power, the state is created. The state is thus created through the use of the administration. The count nobility emerges in contrast to the princely nobility. “Count” has the same origin as graphologist: it comes from graphein, to write. “Count” means writer. The count is the Roman scribe, the administrator, while the princely nobility, as the old warrior nobility, is still associated with bravery, heroism, and the like. The “prince” is the first, the foremost. Thus, with the transition from prince to count, the principle of the state came into being. Of course, this can be illustrated quite well with these examples.

L. explains how he would teach children about the spread of Christianity among the Germanic peoples.

Rudolf Steiner: In its practical application, Arian Christianity was very similar to later Protestantism, but it was less abstract and more concrete.

In the 1st and 2nd centuries, the cult of Mithras was very widespread among Roman soldiers on the Rhine and Danube, especially among the officers. — Thor, Wotan, and Saxnot were worshipped in what is now Alsace and everywhere else until the 6th, 7th, and 8th centuries as the ancient Germanic folk gods, as the three main gods, with Germanic religious customs.

One can describe numerous scenes, such as in Alsace and the Black Forest, where small churches were built by Roman clerics. “We want to do this and that for Wotan,” sang the men. The women sang: “Christ has come for those who do nothing of their own accord.” This trick had already been used in the spread of Christianity, that one did not have to do anything to be saved.

“Eiche” is the term used in the ancient Germanic cult language to refer to the priest of Donar. At the time when Boniface was active, it was still very much a question of whether people still knew the formulas. Boniface knew how to take possession of certain formulas. He knew the magic word, but the priest of Donar no longer knew it. Boniface, through his higher power, through the “axe,” the magic word, felled the priest of Donar, the “Donar oak.” The priest died of grief; he perished “by the fire of heaven.” These are images of the imagination! After a few generations, this was transformed into the familiar image.

You must learn to read such imaginative images. And in learning, teach; in teaching, learn.

Boniface Romanized Germanic Christianity.

Charlemagne's life was described by Einhard. Einhard is a flatterer.

U. talks about music lessons.

Rudolf Steiner: Those who are less advanced in music lessons should at least be included in the exercises for the advanced students, even if they are inactive and only listen. If all else fails, they can always be separated. Incidentally, there will be many other subjects where similar problems arise, where the advanced and the backward cannot be brought into harmony. This will be less of a problem if the right methods are used. Today, this is only concealed by all kinds of circumstances. If you teach practically according to our principles, you will encounter difficulties that you would not otherwise notice, even in subjects other than music. For example, in drawing and painting. You will have children who are very difficult to advance artistically, including in the plastic arts and the visual arts. In such cases, you must try not to separate the children too early, but only when it is absolutely necessary.

N. talks about the treatment of poetry in French and English lessons.

Rudolf Steiner: We firmly believe in teaching English and French to children in moderation from the very beginning. Not in a governess-like manner, but in such a way that they learn to appreciate both languages and develop a feeling for the correct expression in both languages.

If a student in the second to fourth grade gets stuck while reciting, you have to help them gently and kindly so that they become confident and don't lose heart. You have to take their good will for the work as well.

For children aged twelve to fifteen, the lyrical-epic element is suitable, ballads; as well as striking historical depictions, good artistic prose, and individual dramatic scenes.

And then we begin with Latin in the fourth grade and Greek in the sixth grade for those children who want to take it, so that we can continue for three years. If we could expand the school, we would start with Latin and Greek at the same time. We would then have to make arrangements so that those children who take Latin and Greek are given some relief in German. This can be done very well, because much of the grammar that would otherwise have to be taught in German is then taught in Greek and Latin. And many other things can also be spared.

C was pronounced like K in ancient Latin; medieval Latin, which was a spoken language, had C. Many dialects were spoken in ancient Rome. One can say “Cicero” because that is how it was still pronounced in the Middle Ages. One cannot speak of something “correct” in language, as it is something conventional.

The methodology of classical language teaching should be based on the same principles, but it should be noted that, with the exception of what I said this morning, the curriculum can essentially be used for classical language teaching. This is because it dates back to the best pedagogical times of the Middle Ages. There is still much that can be learned pedagogically from the methodology used for Greek and Latin. The curricula still follow what was done in the past, and that is not entirely unreasonable. The composition of the textbooks is something that can no longer be used today, insofar as the somewhat clumsy memorization rules should actually be avoided today. They seem a little childish to people today, and since they have been translated into German, they are also a little too clumsy. We will try to avoid this, but otherwise the methodology is not so bad.

Sculpture should begin before the age of nine, with spheres, then other things, and so on. In sculpture, too, one should work entirely from forms.

R. asks whether report cards should be given.

Rudolf Steiner: As long as the children are in the same school, why should report cards be given? Give them when the children leave. There is no profound pedagogical significance in devising new grades. Grades for individual pieces of work could be given quite freely, without any specific scheme.

The communication to the parents is, under certain circumstances, also something like a grade, but that cannot be completely avoided. For example, it may prove necessary—which we would of course treat with a slightly different tone than is usually the case—for a student to remain at the same level for longer; we would of course have to do that. We will be able to avoid this as far as possible with our method. Because if we follow the practical principle of improving as much as possible in such a way that the student benefits from the improvement—in other words, if we let him do the math, and place less emphasis on the fact that they cannot do something in arithmetic, but rather on getting them to be able to do it afterwards — if we follow the principle that is completely opposite to the previous one, then not being able to do something will no longer play as big a role as it does now. The whole teaching process would be transformed from the teacher's obsession with assessment, which he cultivates by writing grades in his notebook every day, to an attempt to help the student again and again at every moment and not to substitute any assessment at all. The teacher would have to give himself a bad grade just as he would give the student if the student cannot do something, because then he has simply not yet succeeded in teaching him.

As a message to parents and as required by the outside world, we can, as I said, issue report cards. We have to stick to what is customary. But in school, we must make it clear that this is not of primary importance to us — we don't need to go into detail about that. We must spread this sentiment like a moral atmosphere.

Now everything has come to fruition for us, so that you can get a mental image, with the exception of what will then have to be discussed in some form with regard to technical integration into the school, which we have not yet come to because we simply did not have the staff: that is female handicrafts. This is something that still needs to be integrated in some way. This must be looked into, but there was no one available who could be considered for this.

Now, of course, it will be necessary for us to discuss the practical structure of the school. We will discuss with you which classes you will be teaching and so on, how we will arrange things for the morning and afternoon, and so on. This must be discussed before we begin teaching. Tomorrow will be the grand opening, and then we will take the opportunity tomorrow or the day after tomorrow to discuss what is still necessary for the technical organization. We will have a decisive conference about this in a very small circle. I will then also have a few words to say about the school dedication.