The Genius of Language

GA 299

29 December 1919, Stuttgart

The Transforming Powers of Language in Relation to Spiritual Life

The experiences of life often lead to apparent contradictions. However, it is just when we carefully examine the contradictions that we discover deep and intrinsic relationships. If you ponder somewhat carefully what I explained in my first talk and restated in the second, and you compare this with my examples yesterday of the inner connections between European languages, you will find such a contradiction. Look at the two series of facts that were characterized. We find in modern German many linguistic “immigrants.” We can feel how many words accompanied Christianity from the South and were added to the original treasure house of the Germanic languages. These words came to us together with Christian concepts and Christian perceptions; they belong today very much to our language. I spoke, too, of other immigrant words as significant because they belong to the widened range of our language possibilities, those that came in from the western Romance languages in the twelfth century. At that time the genius of the German language still possessed the power of adaptation; it transformed in its own way what was received from Western Europe, not only as to sound but also as to meaning. Few people suspect, I said before, that the German word fein (fine) is really of French origin: fin, and that it entered our language only after the twelfth century.

I mentioned Spanish elements coming in at a later time, when German no longer had the same strength of transformation—and how this strength was totally at an end when English words entered the German language during the last part of the eighteenth but particularly during the nineteenth century. Thus we see words being continually taken over in Central Europe, from the Latin or from the Greek through Latin, or from the western Romance languages. Because of all this, we can say that our present vocabulary has absorbed foreign elements but also that our language in its very origin is related to the languages that gave it seemingly foreign components in later times.

We can easily establish the fact—not in the widest sense but through characteristic examples—that languages over far-flung areas of the earth have a common origin. Take naus for instance, the Sanskrit word for ‘ship’. In Greek it is also naus, in Latin navis. In areas of Celtic coloring you will find nau. In Old Norse and the older Scandinavian tongues you have nor: [In English there is nautical, nautilus, navy, navigate, and so forth]. It is unimportant that this word root has been thrown overboard [German has Schiff noun, and schiffen, verb, as English ship, noun and verb]. Despite this, we can observe that there exists a relationship encompassing an exceedingly large area across Europe and Asia.

Take the ancient East Indian word aritras. We find the word later as eretmón in Greek and then, with some consonants dropped, as remus in Latin. We find it in Celtic areas as rame and in Old High German as ruodar. We still have this word; it is our Ruder tudder’, ‘oar’. In this way one can name many, many words that exist in adaptations, in metamorphoses, across wide language sectors; the Gothic, the Norse, the Friesian, Low German, and High German—also in the Baltic tongues, the Lithuanian, Latvian, and Prussian. We can also find such words in the Slavic languages, in Armenian, Iranian, Indian, Greek, Latin, and Celtic. All across the regions where these languages were spoken, we discover that a primeval relationship exists; we can easily imagine that at a very ancient time the primordial origins of language-forming were similar right across these territories and only later became differentiated.

I did say at the beginning that the two series of facts contradict each other, but it is just by observing such contradictions that we can penetrate more deeply into certain areas of life. The appearance of such phenomena leads to our discovering that human evolution through the course of history has not at all taken place in a continuously even way, but rather in a kind of wave movement. How could you possibly imagine this whole process, expressed in two seemingly contradictory bodies of fact, without supposing that some relationship existed between the populations of these far-flung territories? We can imagine that these peoples kept themselves shut off at certain times, so that they developed their own unique language idioms, and that periods of isolation alternated with periods of influencing or being influenced by another folk. This is a somewhat rough and ready characterization, but only by looking at such rising and falling movements can we explain certain facts. Looking at the development of language in both directions, as I have just indicated, it is possible to gain deeper insights also into the essential nature of folk development.

Consider how certain elements of language develop—and this we will do now for the German language—when a country closes itself off from outside influences and at other times takes in foreign components that contribute their part to the spirit-soul elements expressed through language. We can already guess that these two alternating movements evoke quite different reactions in the spirit and soul life of the peoples.

On one hand it is most significant that a primordial and striking relationship exists between important words in Latin and in the older forms of the Central European languages—for instance, Latin verus ‘true’, German wahr ‘true’, Old High German wâr [in German /w/ is pronounced /v/. We have in English verity, very, from Old French veras]. If you take such obvious things as Latin, velle = wollen ‘will’ or even Latin, taceo ‘I am silent’ and the Gothic thahan [English tacit, taciturn, you realize that in ancient times there prevailed related, similar-sounding language elements over vast areas of Europe—and this could be proven also for Asia.

On the other hand, it is really remarkable that the inhabitants of Central Europe from whom the present German population originated, accepted foreign elements into their languages relatively early, even earlier than I have described it. There was a time when Europe was much more strongly pervaded by the Celtic element than in later historic times, but the Celts were subsequently crowded into the western areas of Europe; then the Germanic tribes moved into Central Europe, quite certainly coming from northern areas. The Germans accepted foreign word elements from the Celts, who were then their western neighbors, much as they later accepted them from the Romans coming from the South. This shows that the inhabitants of Central Europe, after their separate, more closed-off development, later accepted foreign language elements from the neighbors on their outer boundaries, whose languages had been originally closely related to their own.

We have a few words in German that are no longer considered very elegant, for instance Schindmähre ‘a dead horse’. Mähre ‘mare’, is a word rarely used in German today but it gave us the word Marstall ‘royal stables’. Mähre is of Celtic origin, used after the Celts had been pushed toward the West. [While English mare is in common usage, nightmare has a different origin: AngloSaxon mearh, ‘horse’; mere, ‘female horse’; Anglo-Saxon mara, ‘goblin, incubus'.] There seems to have been no metamorphosis of the word, either in Central Europe or the West; apparently the Germans took over the word later from the Celts. In fact, a whole series of such words was taken over, for some of which the power of adaptation could be found. For instance, the name—which is really only partly a name—Vercingetorix contains the word rix. Rix, originally Celtic, was taken up by the Celts to mean ‘the ruler,” the person of power (Gothic reiks Latin rex). It has become the German word reich (Anglo-Saxon, rice, ‘powerful’, ‘rich’), ‘to become powerful through riches’. And thus we find adaptations not only from Latin but also from the Celtic at the time when the Central European genius of language still possessed the inner strength of transformation.

If the external development of language could be traced back far enough—of course, it cant be—we would ultimately arrive at that primeval language-forming power of ancient times when language came about through what I described yesterday as a relationship to consonants and vowels, a relationship of sound and meaning. Languages start out with a primitive structure. What then brings about the differences in them? Variety is due, for instance, to whether a tribe lives in a mountainous area or perhaps on the plain. The larynx and its related organs wish to sound forth differently according to whether people live high up in the mountains or in a low-lying area, and so on, even though at the very beginning of speech, what emerges from the nature of the human being forms itself in the same way.

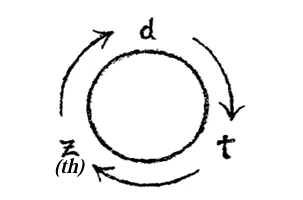

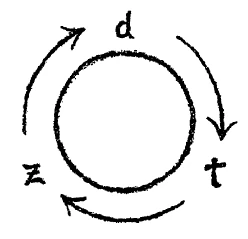

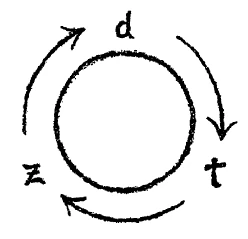

There exists a remarkable phenomenon in the growth and development of language, which we can look at through examples from the Indo-European languages. Take the word zwei (two), Latin duo. In the older forms of German [also AngloSaxon], we have the word twa or ‘two’. Duo points to the oldest step of a series of metamorphoses in the course of which duo changes to twa and finally to zwei It is too complicated to take the vowels into account. Considering only the consonants, we find that the direction of change runs like this: /d/ becomes /t/ and /t/ becomes /z/, exactly in this sequence:

We note that as the word moves from one area to another, a transformation of the sound takes place. The corresponding step to German /z/ is in other languages a step to /th/.

This is by no means off-base theorizing. To describe the process in detail we should have to collect many examples, yet this sequence corresponds to Grimm’s Law in the metamorphosis of language.1Jakob Grimm in his book on Germanic grammar codified this consonant shift so that it is known as Grimm’s Law. See lecture 2, pp. 29-30.Take, for instance, the Greek word thyra, ‘door’. If we take it as an early step, arrested at the first stage, we must expect the next step to use a /d/, and sure enough, we find it in English: door: The final change would arrive clockwise at /t/, and there it is: modern German Tür, ‘door’.

Therefore we can find, if we look, the oldest “language-geological stratum,” where the metamorphosing word stands on any one of these steps. The next change will stand on the following step, and then on the final step as modern German.

If the step expressed in Latin or Greek contains /t/, English (which has remained behind) will have the /th/, and modern German (which has progressed beyond English) will have a /d/ [cf. Latin tu, Anglo-Saxon thu ‘thou’, German du ‘you'].

When modern German has /z/ (corresponding to English /th/ the previous step would have been /t/, and the original GrecoLatin word would have had a /d/. This can be discovered.

We would then expect, following a word with a /t/ in Gothic, to find as the second step a /z/. Take the word Zimmer ‘room’, for the relationship of modern German to the next lower, earlier step in the Gothic or in Old Saxon, both of which stand on the same level: Zimmer has come from timbar. From /z/ we have to think back to /t/. This is merely the principle; you yourselves can find all this in the dictionary.2See also Rudolf Steiner, The Realm of Language and Arnold Wadler, One Language.

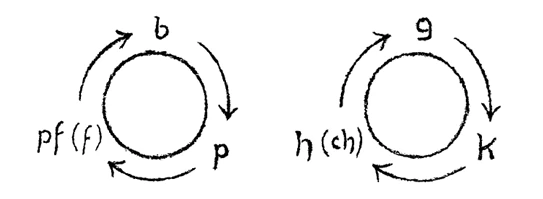

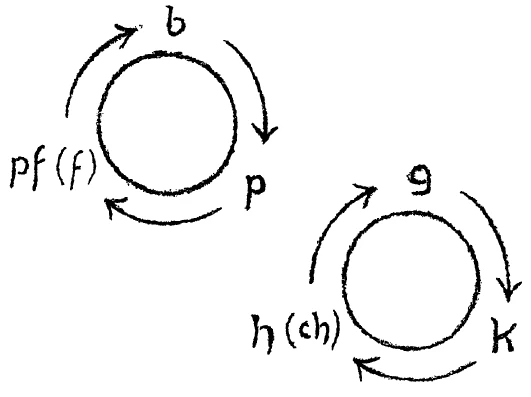

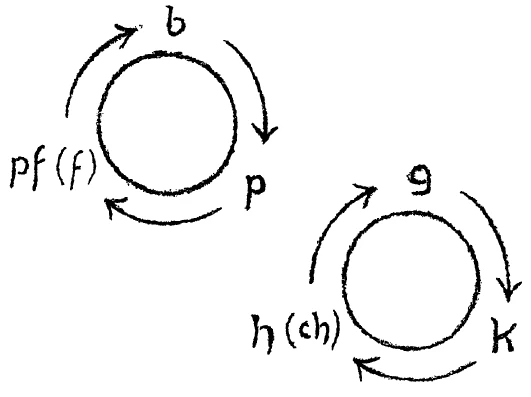

There are many other lively language metamorphoses; as a parallel to the just-mentioned sequence, there is also this one: if an earlier word has a /b/, this becomes on the next step a /p/, followed on the third step by /f/, /ph/, or /pf/ [Latin labi ‘slip’, Anglo-Saxon, hleapan ‘leap’, German laufen ‘run’].

In the same way the connection /g/—/k/—/h/ or /ch/ exists. You will find corresponding examples [cf. Latin ego, Anglo-Saxon ic, Dutch ik German ich]. We can sum up as follows: Greek and Latin have retained language elements at an early stage of metamorphosis. Whatever then became Gothic advanced to a later stage and this second stage still exists today, for instance in Dutch and in English. A last shift of consonants took place finally around the sixth century A.D., when language advanced one stage further to the level of modern German. We can assume that the first stage will probably be found spread far into Europe, in time perhaps only up to about 1500 B.C. Then we find the second stage reigning over vast areas, with the exception of the southern lands where the oldest stage still remained. And finally there crystallizes in the sixth century A.D. the modern German stage. While English and Dutch remain back in the earlier second stage, modern German crystallizes out.

I urge you now to take into account the following: The relationship that people have to their surroundings is expressed by the consonants forming their speech, completely out of a feeling for the word-sound character. And this can only happen once—that is, only once in such a way that word and outer surroundings are in complete attunement. Centuries ago, if the forerunners of the Central European languages used, let’s say, a /z/ on the first step to form certain words, they had the feeling that the consonant character must be in harmony with the outside phenomena. They formed the /z/ according to the outer world.

The next stage of change can no longer be brought about according to the outside world. The word now exists; the next stages are being formed internally, within human beings themselves and no longer in harmony with their surroundings. The reshaping is in a way the independent achievement of the folk soul. Speech is first formed in attunement with the outer world, but then the following stages would be experienced only inwardly. An attuning to the external does not take place again.

Therefore we can say that Greek and Latin have remained at a stage where in many respects a sensitive attunement of the language-forming element to the outer surroundings has been brought to expression. The next stage, forming Gothic, Old High German, Old English, and so forth, has proceeded beyond this immediate correspondence and has undergone a change to the element of soul. These languages have therefore a far more soul-filled character. We see that the first change that occurs gives language an inner soul coloring. Everything that enters our sensing of language on reaching this second stage gives inwardness to our speech and language. Slowly and gradually this has come about since 1500 B.Cc. This kind of inwardness is characteristic of certain ancient epochs. Carried over into later ages, however, it changed into a simpler, more primitive quality. Where it still exists today, in Dutch and English, it has passed over into a more elemental feeling for words and sounds.

Around the sixth century A.D. modern German reached the third stage.3“Starting most probably in the southernmost reaches of the German-speaking lands, some time in the fifth century, a series of sound changes gradually resulted in restructuring the phonetic systems of all the southern and many of the midland dialects, resulting in High German”—John T. Waterman, A History of the German Language (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1966). Now the distancing from the original close attunement to the outside proceeds still further. Through a strong inward process the form of modern German proceeds out of its earlier stage. It had reached the second stage of its development and moved into the realm of soul; the third stage takes the language a good distance away from ordinary life. Hence the peculiar, often remote, abstract element in the German language today, something that presses down on the German soul and that many other people in the rest of Europe cannot understand at all. Where the High German element has been wielded to a special degree, by Goethe and Hegel for instance, it really can't be translated into English or into the Romance languages. What comes out are merely pseudo-translations. People have to make the attempt, of course, since it is better to reproduce things somehow or other rather than not at all. Works that belong permanently to this German organism are penetrated by a strong quality of spirit, not merely a quality of soul. And spirit cannot be taken over easily into other languages, for they simply have no expressions for it.

The ascent of a language to the second step, then, is not only the ensouling of the language, but also the ensouling of the folk-group’s inwardness through the language. The ascent to the third step that you can study especially in modern German [and especially in written German], is more a distancing from life, so that by means of its words such abstract heights can be reached as were reached, for instance, by Hegel, or also, in certain cases, by Goethe and Schiller. That is very much dependent on this reaching-the-third-step. Here German becomes an example. The language-forming, the language-development frees itself from attuning to the external world. It becomes an internal, independent process. Through this the human-individual soul element progresses which, in a sense, develops independently of nature.

Thus the Central European language structure passed through stages where from a beginning step of instinctive, animal-like attuning to the outer world, it acquired soul qualities and then became spiritual. Other languages, such as Greek and Latin, developed differently in their other circumstances. As we study these two ancient languages primarily from the standpoint of word formation, we have to conclude that their word and sound structures are very much attuned to their surroundings. But the peoples who spoke these languages did not stop with this primitive attunement to the world around them. Through a variety of foreign influences, from Egypt and from Asia, whose effects were different from those in Europe, Greek and Latin became the mere outer garment for an alien culture introduced to them from outside, essentially a mystery culture. The mysteries of Africa and Asia were carried over to the Greeks and to a certain degree to the Romans; there was enough power in them to clothe the Asian mysteries and the Egyptian mysteries with the Greek and Latin languages. They became the outer garments of a spiritual content flowing into them drop by drop. This was a process that the languages of central and northern Europe did not participate in. Instead, theirs was the course of development I have already described: On the first step they did not simply take in the spiritual as the Greeks had done but first formed the second stage; they were about to reach the third stage when Christianity with its new vocabulary entered as a foreign, spiritual element. Evidently, too, the second stage had been reached when the Celtic element made its way in, as I described earlier. With this we see that the spiritual influence made its entrance only after an inner transforming of the Germanic languages had taken place. In Greek and Latin there was no transforming of this kind but rather an influx of spirituality into the first stage.

To determine the character of a single people, we have to study concrete situations or events, in order to discover the changes in its language and its relationship to spiritual life. Thus we find in modern German a language that, on reaching its third stage, removed itself a good distance from ordinary life. Yet there are in German so many words that entered it through those various channels: Christianity from the South, scholasticism from the South, French and Spanish influences from the West. All these influences came later, flowing together now in modern German from many different sources.

Whatever has been accepted as a foreign element from another language cannot cause in us as sensitive a response as a word, a sound combination, that has been formed out of our own folk-cultural relationship to nature or to the world around us. What do we feel when we utter the word Quelle ‘spring’, ‘source’, ‘fountain’; ‘cognate, well? We can sense that this word is so attuned to the being of what it describes, we can hardly imagine calling it anything else if with all our sensitivity we were asked to name it. The word expresses everything we feel about a Quelle. This was the way speech sounds and words were originally formed: consonants and vowels conformed totally to the surrounding world. [English speakers can feel the same certainty about spring. Anglo-Saxon springan. Arnold Wadler has pointed out the particularly lively quality of all spr- words, such as sprout, sprig, sprite, spray, sprinkle, surprise, even sport—and of course spirit.] But now listen to such words as Essenz ‘essence’ or Kategorie ‘category’ or Rhetorik ‘rhetoric’. Can you feel equally the relationship to what the word meant at its beginning? No! As members of a folk-group we have taken in a particular word-sound, but we have to make an effort to reach the concept carried on the wings of those sounds. We are not at all able to repeat that inner experience of harmony between word-sound and concept or feeling. Deep wisdom lies in the fact that a people accepted from other peoples such words in either their ascending or descending development, words it has not formed from the beginning, words in which the sound is experienced but not its relationship to what is meant. For the more a people accepts such words, the more it needs to call upon very special qualities in its own soul life in order to come to terms with such words at all. Just think: In our expletives and exclamations we are still able today to experience this attuning of the language-forming power to what is happening in our surroundings. Pfui! ‘pooh! ugh!’, Tratsch! ‘stupid nonsense!’, Tralle walle! [probably an Austrian dialect term. English examples: ‘Ow!’, ‘Damn!’, ‘Hah!’, ‘Drat it!']. How close we come to what we want to express with such words! And what a difference you find when you're in school and take up a subject—it needn't even be logic or philosophy—but simply a modern science course. You will immediately be confronted with words that arouse soul forces quite different from those that let you sense, for instance, the feeling you get from Moo! that echoes in a “word” the forming of sounds you hear from a cow. When you say the word Moo, the experience of the cow is still resounding in you.

When you hear a word in a foreign language, a very different kind of inner activity is demanded than when you merely hear from the sound of the word what you are supposed to hear. You have to use your power of abstraction, the pure power of conceptualizing. You have to learn to visualize an idea. Hence a people that has so strongly taken up foreign language elements, as have the Central Europeans, will have educated in itself—by accepting these foreign elements—its capacity for thinking in ideas.

Two things come together in Central Europe when we look at modern German: on the one hand the singular inwardness, actually an inner estrangement from life, that results from moving into the third stage of language development; on the other hand, everything connected with the continuous takingin of foreign elements. Because these two factors have come together, the most powerful ability to form ideas has developed in the German language; there is the possibility to rise up to completely clear concepts and to move about freely within them. Through these two streams of language development, a prodigious education came about for Central Europe, the education of INNER WORDLESS THINKING, where we truly can proceed to a thinking without words. This was brought about in abundant measure by means of the phenomena just described.

These are the things that have evolved; we will not understand the nature of modern German at all if we don't take them into account. We should observe carefully the sound-metamorphoses and word-metamorphoses that occur through the appropriation of foreign words at the various stages of development.

This is what I wanted to present to you today, in order to characterize the Central European languages.

Dritter Vortrag

Die Tatsachen des Lebens führen oftmals, äußerlich betrachtet, zu Widersprüchen; aber gerade wenn man solche Widersprüche dann richtig der Untersuchung unterwirft, kommt man auf die tieferen, wesenhaften Zusammenhänge. Einen solchen Widerspruch können Sie bei einigermaßen gründlichem Nachdenken konstatieren zwischen demjenigen, was ich Ihnen im ersten Vortrag hier auseinandergelegt und im zweiten rekapituliert habe, und demjenigen, was ich dann gestern an einzelnen Beispielen als einen inneren Zusammenhang europäischer Sprachen auseinandergesetzt habe. Stellen wir uns doch einmal die dadurch charakterisierten zwei Tatsachenreihen vor das Auge: Wir haben auf der einen Seite darauf aufmerksam gemacht, daß wir im gegenwärtigen Bestand unserer Sprache viele Eindringlinge finden; daß wir fühlen, wie von Süden her mit dem Christentum in unsere Gegenden zu dem ursprünglichen deutsch-germanischen Sprachreichtum anderes hinzugekommen ist, was gewissermaßen mit den christlichen Vorstellungen und christlichen Empfindungen zugleich die christlichen Wörter gebracht hat; so daß jetzt diese christlichen Wörter in der charakterisierten Art innerhalb unseres Sprachwesens bestehen. Dann habe ich noch von anderen Eindringlingen gesprochen, die immerhin auch eine Bedeutung haben, weil sie schon einmal zu dem Umfang unseres Sprachwesens gehören; von jenen Invasionen, die etwa im 12. Jahrhundert beginnen, die von westlichen romanischen Ländern ausgehen, und die auch noch in eine Zeit hineinfallen, in welcher der deutsche Sprachgenius umbildende Kraft hat. Da bildet er, was er vom Westen empfängt, in seiner Art noch um, bildet es dem Laut nach, bildet es auch der Bedeutung nach noch um. Ich sagte damals: Wenige ahnen heute, daß zum Beispiel das im Deutschen gebrauchte Wort fein eigentlich französischen Ursprungs ist: fin und daß es erst nach dem 12, Jahrhundert in unser Sprachwesen hereingekommen ist, vorher nicht da war. — Ich machte dann darauf aufmerksam, wie auch Spanisches schon in einer Zeit, in der nicht mehr die umbildende Kraft des deutschen Sprachwesens vorhanden war, eindrang; und wie ganz und gar nicht mehr diese umbildende Kraft da war, als im letzten Teil des 18. Jahrhunderts, insbesondere aber im 19. Jahrhundert Elemente des Englischen eindrangen in das deutsche Sprachwesen. Da sehen wir fortwährend, daß vom Lateinischen oder auch vom Griechischen, auf dem Umwege durch das Lateinische, oder wiederum von den westlichen romanischen Sprachen her Wörter aufgenommen wurden nach Mitteleuropa hinein. Das ist eine Tatsache, die uns dazu führen muß, zu sagen: Unser gegenwärtiger Sprachschatz besteht nur zum Teil aus Ursprünglichem und trägt dann eben später Aufgenommenes in sich. Nun aber habe ich Sie wiederum aufmerksam gemacht, wie zwischen einer ganzen Reihe von Sprachen engere Verwandtschaft besteht. Ich habe Sie hingewiesen auf manche gotische Formen und gezeigt, wie dann diese in die Formen unserer Sprache übergegangen sind; und wir haben hinweisen können an manchen Stellen, wie das betreffende Wort auch im Lateinischen oder Griechischen zu finden ist. Während wir also sagen müssen: Unsere Sprache hat Fremdes in sich aufgenommen -, müssen wir auf der anderen Seite sagen: Unsere Sprache ist urverwandt mit denjenigen Sprachen, aus denen sie in späterer Zeit wiederum etwas wie fremde Bestandteile aufgenommen hat.

Nun kann man sehr leicht nachweisen, wenn auch nicht in sehr umfassendem Sinn, aber an charakteristischen Beispielen, daß über weitere Erdenterritorien hin eine Urverwandtschaft des Sprachlichen besteht. Sie brauchen nur so etwas zu nehmen wie naus, das Sanskritwort für Schiff. Wenn Sie dieses Wort im Griechischen aufsuchen, dann haben Sie ebenfalls raus, wenn Sie dieses Wort im Lateinischen aufsuchen, so haben Sie navis. Suchen Sie dasselbe Wort auf im mehr keltisch gefärbten Gebiete, so haben Sie das Wort nau, suchen Sie das Wort auf im Altnordischen, in den altskandinavischen Sprachen, so haben Sie nor. Daß solche Worte dann für das Deutsche abgeworfen sind, hat ja geringere Bedeutung. Aber wir sehen, daß im weitesten Umfang eine Verwandtschaft besteht, eine Verwandtschaft, die wir für vieles nachweisen können, eben auf einem außerordentlich großen Gebiet über Europa und Asien hinüber. Nehmen Sie das altindische Wort aritras, so finden wir das Wort wieder als eretmón im Griechischen; wir finden dasselbe Wort wiederum mit gewissen Abwerfungen als remus im Lateinischen; wir finden in keltischen Gebieten rame, und wir finden im Althochdeutschen ruodar. Wir haben dieses Wort noch; es ist unser Ruder. Und so könnte man eine große Anzahl von Wörtern zusammenstellen, die in Umbildungen, in Metamorphosierungen über weite Gebiete der Sprachen vorhanden sind: etwa im Gotischen, den nordisch-skandinavischen Sprachen, den friesischen Sprachen, niederdeutschen Sprachen, in der hochdeutschen Sprache, auch in baltischen Idiomen, im Litauischen, Lettischen, Preußischen. Auch kann man solche Verwandtschaften nachweisen in slawischen Sprachen; im Armenischen, im Iranischen, im Indischen, im Griechischen, im Lateinischen, im Keltischen. Über die Gebiete dieser Sprachen hin sehen wir, wie eine Urverwandtschaft des Sprachlichen besteht. So daß wir uns sehr leicht vorstellen können, daß gewissermaßen die Ursachen des Sprachbildens über all diese Territorien hinüber in einer sehr alten Zeit ähnliche waren, daß sie sich nur dann später differenziert haben.

Ich sagte: Diese beiden Tatsachenreihen widersprechen einander; aber gerade durch die Beobachtung solcher Widersprüche kann man in manche Dinge des Lebens wesenhaft tiefer eindringen. Denn wir werden gerade durch eine solche Erscheinungsreihe dazu geführt, uns zu sagen: Die Entwickelung, welche die Menschheit im Laufe der Geschichte durchmacht, vollzieht sich ganz und gar nicht, wie man sich oftmals vorstellt, recht kontinuierlich, sondern in einer Art von Wellenbewegung. Denn wie sollen Sie sich denn eigentlich diesen ganzen Vorgang, der durch diese zwei einander scheinbar widersprechenden Tatsachen ausgedrückt wird, anders vorstellen, als daß eine gewisse Verwandtschaft der Bevölkerungen über diese weiten Territorien besteht; daß diese Völker sich eine gewisse Zeit hindurch so abgeschlossen halten, daß sie ihre differenzierten Sprachidiome ausbilden; daß es also eine Periode des Abschlusses der Völker gibt, und daß diese wechselt mit einer Periode, wo Einfluß eines Volkes auf das andere stattfindet. Das ist zwar die Sache etwas roh charakterisiert; aber nur dadurch, daß man auf eine solche auf- und absteigende Bewegung hinblickt, können gewisse Tatsachen wirklich erklärt werden. Nun kann man, wenn man nach den beiden Richtungen hin, wie ich Ihnen jetzt angegeben habe, die Entwickelung der Sprache betrachtet, tiefere Blicke hineintun in das Wesen der Volksentwickelung überhaupt. Man muß nur Rücksicht nehmen auf der einen Seite - und wir werden das nun anwenden auf die Entwickelung der deutschen Sprache — auf die Art, wie gewissermaßen unter Abschluß nach außen sich gewisse Elemente des Sprachlichen entwickeln, und wie wiederum Fremdbestandteile aufgenommen werden und auch beitragen zu all dem Geistig-Seelischen, das durch die Sprache zum Ausdruck kommen kann. Wir können ja schon ahnen, daß diese beiden Elemente in ganz verschiedener Weise sich zum Geistes- und Seelenleben des betreffenden Volkes verhalten müssen.

Wir können auf der einen Seite auf die außerordentlich bedeutungsvolle Tatsache hinsehen, daß eine Urverwandtschaft da ist, die uns ganz besonders entgegentritt, wenn wir sehen, daß außerordentlich wichtige Wörter verwandt sind, sagen wir für das Lateinische und für die älteren Formen der mitteleuropäischen Sprachen. Lateinisch verus: wahr; althochdeutsch: wâr. Wenn Sie solche auffallenden Dinge nehmen wie: velle = wollen, oder das lateinische taceo = ich schweige, für das im Gotischen auftretende thahan, so müssen Sie sich sagen: ähnlich Klingendes, also sprachlich Verwandtes hat in alter Zeit über weite Gebiete Europas — und man könnte es auch für Asien nachweisen — geherrscht.

Auf der anderen Seite ist es außerordentlich merkwürdig, daß die Bewohner Mitteleuropas, aus denen dann die heutigen Deutschen hervorgegangen sind, doch auch verhältnismäßig früh Fremdsprachliches aufgenommen haben. Sogar noch früher, als ich es Ihnen bisher charakterisiert habe. Es hat eine Zeit gegeben, wo Europa viel mehr vom keltischen Element erfüllt war als in den historischen Zeiten, von denen man gewöhnlich spricht. Die Kelten sind aber dann in westliche Gegenden Europas gedrängt worden, und es zogen in Mitteleuropa germanische Völkerschaften ein, ganz gewiß von nördlichen Gegenden aus. Nun haben auch schon von den Kelten, die nun ihre westlichen Nachbarn waren, die Germanen ebenso fremde Wortbestandteile aufgenommen, wie sie sie später vom Süden aufgenommen haben, vom Lateinischen. Das heißt, die Bewohner Mitteleuropas haben, nachdem sie mehr abgeschlossen sich entwickelt haben und die anderen sich für sich entwickelt haben, von den Randgebieten, die aber ursprünglich mit ihnen sprachlich verwandt waren, später fortwährend Fremdsprachliches aufgenommen.

Wir haben gar manches Wort, das nicht mehr ganz der Eleganz angehört, sagen wir das Wort Schindmähre: das ist ein verschundenes Pferd. Dieses Schindmähre weist hin überhaupt auf ein altes Wort: Mähre, für Pferd; wovon wir etwa noch das Wort Marstall haben. Dieses Wort ist aber keltischen Ursprungs, findet sich unter den Kelten, nachdem diese bereits nach Westeuropa gedrängt worden sind. Und es ist wohl nicht eine Metamorphose vorhanden, die auf der einen Seite in Mitteleuropa wäre und dann im Westen, sondern dieses Wort müssen die Germanen einfach von den Kelten später übernommen haben. Und eine ganze Reihe von solchen Wörtern ist übernommen worden, allerdings auch solche, für die man die umbildende Kraft hat. Sie haben zum Beispiel in dem Namen, der eigentlich nur teilweise ein Name ist, Vercingetorix, das Wort rix darinnen. Rix ist eine ursprünglich keltische Bildung, ist aufgenommen worden bei den Kelten, bedeutete bei ihnen den Herrscher, den Mächtigen, und ist zu unserem Worte reich geworden, mächtig sein durch Reichtum. Also auch da Umbildung nicht nur vom Lateinischen, sondern auch vom Keltischen in der Zeit, als der mitteleuropäische Sprachgenius noch innere umbildende Kraft hatte.

Würde man nun äußerlich die Entwickelung der Sprache genügend weit zurückverfolgen können — man kann es ja nicht -, so würde man zuletzt ankommen bei jener primitiven sprachbildenden Gewalt alter Zeiten, in denen aus einem solchen Verhältnis zum Konsonantischen und Vokalischen, wie ich es gestern charakterisiert habe, die Sprachen entstehen. Die Sprachen entstehen in einer primitiven Form. Was dann als Differenzierung in den Sprachen auftritt, rührt davon her, daß das, was ursprünglich eigentlich in der gleichen Weise aus der menschlichen Natur sich bilden will, in der verschiedensten Art, je nachdem zum Beispiel ein Stamm eine Gebirgsgegend oder eine ebene Gegend bewohnt, zum Ausdruck kommt. Der Kehlkopf und seine benachbarten Organe wollen sich anders äußern in einer Gebirgsgegend, anders in einer flachen Gegend und so weiter.

Nun tritt in der Fortbildung der Sprache eine eigentümliche Erscheinung auf, die wir am Beispiel der indogermanischen Sprachen betrachten wollen. Nehmen wir das Wort zwei, so haben wir im Lateinischen duo. Wenn das in ältere Formen der Sprachen in Mitteleuropa geht, haben wir dafür das Wort two, und wenn wir zu uns selber heutigen Tages gehen, haben wir dafür das Wort zwei. Sie sehen in diesem Worte auf seinem Metamorphosengang das Folgende: Dieses duo weist uns hin auf eine älteste Stufe, die sich im Lateinischen erhalten hat; two ist eine spätere Stufe, und die neueste Stufe, die sich gebildet hat, ist zwei. Sehr kompliziert wäre es, auf die Vokale Rücksicht zu nehmen. Wir nehmen auf den Konsonanten hier Rücksicht und müssen uns sagen: Auf dem Metamorphosenwege, den dieses Wort gemacht hat, sehen wir, das d wird zum t und das t wird zum z, und zwar in dieser Reihenfolge d-t-z. Wir sehen also, daß auf der Wanderung des Wortes eine Umbildung des Lautes sich vollzieht. Dem deutschen z entspricht in anderen Sprachen die th-Stufe.

Das ist durchaus nicht etwas, was in künstlicher Weise ausspekuliert ist. Wollte man es in Einzelheiten beschreiben, so müßte man es natürlich ausführen, aber dieses Schema ist etwas, das einem gesetzmäßigen Gange in der Metamorphose der Sprache entspricht. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel das griechische Wort thyra. Wenn Sie es ansehen als eine alte Stufe, die auf früherem Stadium stehengeblieben ist, so müßte die nächste Stufe eine solche sein, die das d hat. Diese Stufe finden Sie bei dem englischen door. Und die letzte umgewandelte Stufe müßte von dem d auf t kommen, dem Zeiger der Uhr nach. Wir haben das hochdeutsche Wort Tür. Und so können wir sagen: Wir können gewissermaßen eine älteste sprachgeologische Schicht konstatieren, in der die Wortmetamorphosen immer auf irgendeiner dieser Stufen stehen. Die nächste Metamorphose steht auf der nächsten Stufe. Und dann können wir eine dritte Stufe im Hochdeutschen konstatieren, die steht wiederum auf der nächsten Stufe.

Würde die Stufe, die ihren Ausdruck im Griechischen hat, ein t haben, so würde das Englische, das zurückgeblieben ist, ein th haben; das Hochdeutsche, das fortgeschritten wäre gegenüber dem Englischen, würde ein d haben.

Da, wo das Hochdeutsche ein dem englischen th entsprechendes z hat, würde die vorhergehende Stufe ein t haben müssen, die vorhergehende griechisch-lateinische Stufe ein d. Das können wir als etwas, was existiert, nachweisen.

Also ein Wort, das zum Beispiel auf der zweiten Stufe, im Gotischen, ein t hätte, das müßte in der nächsten Stufe ein z haben. Nehmen wir ein Wort, das hier gebraucht werden kann für das Verhältnis des Neuhochdeutschen zu der nächst tieferen Stufe im Gotischen, so haben wir Zimmer; im Gotischen, beziehungsweise in dem auf gleicher Stufe stehenden Altsächsischen, ist das Zimmer timbar. Vom z müssen wir auf das £ zurückgehen; ich will Ihnen nur das Prinzip angeben, Sie können sich selber, wenn Sie ein Lexikon nehmen, diese Dinge zusammensuchen.

Geradeso nun wie diese Reihenfolge richtig ist, so können Sie noch außer manchem anderen wesenhaft Metamorphosischen in der Sprache dieses verfolgen: wenn Sie Worte vergleichen, die ein b haben, so wird dies in der nächsten Stufe zu einem p, dieses in der nächsten Stufe zu einem pf, ph oder f und dieses wiederum zu einem b.

Ebenso wie dieses gibt es noch den Zusammenhang g-k-ch (h) und wiederum zurück zu g. Auch dafür gibt es entsprechende Beispiele. So daß wir folgendes sagen können: Das Griechisch-Lateinische hat das Sprachelement auf einer früheren Metamorphosenstufe erhalten. Dasjenige, was da gotisch geworden ist, ist aufgerückt zu einer späteren Stufe. Vieles von dem, was bis zu dieser Stufe aufgerückt ist, ist heute noch erhalten, zum Beispiel im Holländischen. Ein letzter Ruck, der erst eigentlich im 6. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert zustande gekommen ist, rückt noch um eine Stufehinauf: es ist die hochdeutsche Stufe. So daß wir sagen können: Wir müßten einmal finden die erste Stufe, vielleicht sehr weit in Europa ausgedehnt, vielleicht nur bis 1500 vor Christi gehend. Dann finden wir alles das, was weite Gegenden beherrscht mit Ausnahme der südlichen Gegenden, in denen die älteste Stufe geblieben ist -, die zweite Stufe. Und dann kristallisiert sich heraus im 6. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert die hochdeutsche Stufe. Das Englische, Holländische bleibt zurück auf der früheren Stufe, das Hochdeutsche kristallisiert sich heraus.

Nun bitte ich Sie, das Folgende zu beachten. Nur einmal gewissermaßen kann das Verhältnis, das der Mensch eingeht zur Umwelt, indem er aus dem Konsonantischen heraus sich den Wortlaut bildet — also noch jetzt vollständig aus dem Sprachgefühl den Wortlaut bildet -, nur einmal kann das in vollständiger Anpassung an die Umgebung geschehen. Wenn einmal die weit zurückliegenden Vorfahren der mitteleuropäischen Sprachen nach der ersten Stufe, sagen wir, auf der Stufe des z ihren Wortlaut für gewisse Worte gebildet haben, da haben sie empfunden: das Konsonantische muß angepaßt werden den äußeren Erscheinungen; da haben sie das z nach der Außenwelt gebildet. Die nächsten Stufen des Fortschrittes können nicht mehr nach der Außenwelt gebildet sein. Ist das Wort einmal da, werden die nächsten Stufen innerlich umgebildet, werden nicht mehr in Anpassung an die äußere Welt gebildet. Die Umbildung ist gewissermaßen eine selbständige Leistung des volksseelischen Elementes. Erst wird auf irgendeiner Stufe der Wortlaut ausgebildet im Einklang mit der Außenwelt, dann müssen die folgenden Stufen nur innerlich erlebt sein; da paßt man sich nicht wiederum an das Äußerliche an.

So kann man sagen: Die Stufe, die in dem Griechisch-Lateinischen stehengeblieben ist, hat in vieler Beziehung zum Ausdruck gebracht, was gefühlte Anpassung des Sprachbildungs-Elementes an die Umgebung ist. Die nächste Stufe, die sich im Gotischen, Altgermanischen und so weiter ausgebildet hat, die ist über dieses unmittelbare Anpassen hinausgeschritten, hat eine seelische Umbildung durchgemacht. Das gibt dieser Sprache eine weit seelischere Nuance. Mit dem Beschreiten der ersten Stufe der Umwandlung erhält das Sprachelement also eine seelische Nuance. So daß alles dasjenige, was in unser Sprachgefühl dadurch hineingekommen ist, daß wir diese zweite Stufe durchgemacht haben, unserer Sprache die Innerlichkeit gibt.

Dies hat sich langsam und allmählich herausgebildet seit dem Jahr 1500 vor Christi Geburt. Diese Art von Innerlichkeit, sie eignete gewissen alten Zeiten. Indem sie sich aber für spätere Zeiten erhielt, ging sie mehr in das Primitive über. So daß da, wo sie heute noch vorhanden ist, im Holländischen und Englischen, sie mehr in ein primitives Erfühlen des Wortlautes übergegangen ist.

Nun hat das Hochdeutsche etwa im 6. nachchristlichen Jahrhundert die dritte Stufe erstiegen. Das ist aber ein noch weitergehendes Entfernen von der ursprünglichen Anpassung, das ist ein starker innerlicher Prozeß, durch den das Hochdeutsche aus der früheren Stufe sich herausgebildet hat. Während das Ersteigen der zweiten Stufe ein Seelisches bewirkt, entfernt man sich mit der dritten Stufe gar sehr vom Leben. Daher das eigentümliche, oftmals lebensfremde, abstrakte Element der hochdeutschen Sprache, dieses, was die hochdeutsche Sprache von sich aus der deutschen Seele aufdrückt als etwas, was viele andere Menschen in Europa überhaupt nicht verstehen. Wo zum Beispiel das hochdeutsche Element in besonderem Maße verwendet worden ist, wie bei Goethe und Hegel, da kann man es nicht in das Englische oder in die romanischen Sprachen übersetzen. Das sind bloße Pseudoübersetzungen. Man muß solche machen, weil es besser ist, wenn die Dinge nachgebildet werden, als wenn sie nicht nachgebildet werden. Was in solchen Worten, die im eminentesten Sinne erst dem Organismus des Hochdeutschen angehören, an sehr stark Durchgeistigtem, nicht bloß Durchseeltem liegt, das kann man nicht einfach in die anderen Sprachen hinübernehmen. Denn die haben keinen Ausdruck dafür.

Es ist also das Ersteigen der zweiten Stufe ein Durchseelen der Sprache auf der einen Seite, aber auch ein Durchseelen der betreffenden Volksinnerlichkeit durch die Sprache. Das Ersteigen der dritten Stufe, das man gerade am Hochdeutschen studieren kann, das ist mehr ein Sich-Entfernen vom Leben, so daß man durch seine Worte solche abstrakte Höhen ergreifen kann, wie sie zum Beispiel Hegel oder auch in gewissen Fällen Goethe und Schiller ergriffen haben. Das hängt gar sehr mit diesem Ersteigen der dritten Stufe durch das Hochdeutsche zusammen. So sehen Sie an dem Beispiele der hochdeutschen Sprache, wie dadurch, daß gewissermaßen die Sprachbildung, die Sprachentwickelung, sich losreißt von der Anpassung an die Außenwelt, wie dadurch, daß sie ein innerlicher, selbständiger Prozeß wird, dasjenige menschlich-individuelle Seelische fortschreitet, das sich in einer gewissen Weise unabhängig von der Natur entwickelt.

So hat das mitteleuropäische Sprachelement Stadien durchgemacht, durch die es erst seelisch, dann geistig geworden ist, während es eine Art instinktmäßigen animalischen Sich-Anpassens an die Außenwelt auf der ersten Stufe war. Durch andere Dinge haben sich dann solche Sprachen, wie das Griechische und Lateinische, entwickelt. Wenn man diese Sprachen den bloßen Wortformen nach nimmt, so muß man sagen: die Wortformen, die Lautformen, sind sehr stark angepaßt an die Umgebung. Aber die entsprechenden Völker, die diese Sprache gesprochen haben, die sind nicht dabei geblieben, diese primitive Anpassung an die Umgebung beizubehalten. Ihre Sprachen sind durch allerlei fremde Einflüsse, die nun anders gewirkt haben als in Europa aus Ägypten, aus Asien —, zum bloßen äußeren Kleid für eine ihnen überbrachte Kultur, zum großen Teil für eine Mysterienkultur geworden. Den Griechen und bis zu einem gewissen Grade den Römern sind die Mysterien Afrikas und Asiens überbracht worden, und man hat die Gewalt gehabt, in die Sprache der Griechen und Römer die Mysterien Asiens und Ägyptens zu kleiden. So sind diese Sprachen äußere Kleider geworden für einen ihnen gleichsam eingeträufelten geistigen Inhalt. Das war ein Prozeß, den die Sprachen Mitteleuropas und die nordischen europäischen Sprachen nicht durchgemacht haben, sondern die haben den anderen eben beschriebenen Prozeß durchgemacht. Sie haben nicht einfach auf der ersten Stufe das Geistige aufgenommen, sondern haben sich erst wenigstens zur zweiten Stufe herangebildet und waren eben im Erreichen der dritten Stufe drinnen: da erst drang zum Beispiel das Christentum als ein fremdes geistiges Element mit neuen Wörtern in sie ein. Und die zweite Stufe war offenbar auch schon erreicht, als jenes keltische Element eindrang, von dem ich heute gesprochen habe. Da haben wir es also mit einem inneren Umbilden der Sprache zu tun. Dann erst kommt der geistige Einfluß. Bei dem Griechisch-Lateinischen aber haben wir es mit keiner derartigen Umbildung der Sprache zu tun, sondern mit einem Hineingießen des Geistigen in die erste Stufe.

So muß man im Konkreten aufsuchen, wodurch eigentlich der Charakter der einzelnen Völker bestimmt wird. Durch solche Dinge findet man so etwas wie die Umbildung der Sprachen und das Verhältnis zum geistigen Leben. Nun haben wir im Neuhochdeutschen erstens eine Sprache, die dadurch, daß sie zur dritten Metamorphosenstufe aufgestiegen ist, sich weit vom Leben entfernt hat. Dann aber sind in dieser Sprache eben durchaus viele solche Wörter drinnen, die auf all den Wegen hereingekommen sind, wie durch das Christentum vom Süden, wie durch die Scholastik vom Süden, wie aus dem französischen, spanischen Wesen vom Westen her. Diese Sprachelemente sind alle später hereingekommen; die sind nun im Hochdeutschen drinnen. Das alles zeigt, wie dieses Hochdeutsche aus seinen Elementen zusammengeflossen ist.

Für etwas, was nun als ein fremdes Element aus einer anderen Sprache aufgenommen wird, hat man ja kein solches Gefühl wie für ein Wort, für einen Lautzusammenhang, den man innerhalb eines Volkes selber bildet im Verhältnis zu der Natur. Empfinden wir etwa das Wort Quelle. Es ist ein Wort, das so, wie wir es empfinden können, so angepaßt ist dem Wesen, zu dem es gehört, daß man sich eigentlich kaum denken kann, daß man aus unserem empfindenden Wesen heraus es anders nennen könnte. Es drückt das Wort alles aus, was man mit der Quelle erlebt. So war überhaupt das ursprüngliche Bilden der Sprachlaute, der Sprachworte und so weiter, daß sie konsonantisch und vokalisch ganz angepaßt waren der Umgebung. Aber wenn Sie zum Beispiel das Wort Essenz oder das Wort Kategorie oder das Wort Rhetorik hören, können Sie da in derselben Weise den Zusammenhang mit dem fühlen, was das Wort ursprünglich bedeutet? Nein, man bekommt als Volk den Wortklang und muß sich bemühen, auf den Flügeln des Wortklanges den Begriff zu bekommen. Man kann dieses innere Erlebnis gar nicht durchmachen, das den Einklang darstellt zwischen dem Wortklang und dem Begriff, der Empfindung. Es liegt eine tiefe Weisheit darin, daß in jenem charakterisierten auf- und abwärts gehenden Entwickeln ein Volk von anderen Völkern solche Wörter aufnimmt, die es nicht selbst unmittelbar gebildet hat, bei denen es den Wortklang hört, aber nicht den Zusammenklang erlebt mit dem, was bezeichnet wird. Denn je mehr solche Wörter aufgenommen werden, desto mehr hat das Volk, das sie aufnimmt, die Notwendigkeit, etwas ganz Besonderes im Seelenleben zu Hilfe zu nehmen, um überhaupt mit so etwas zurechtzukommen. Man braucht sich ja nur zu erinnern. Sehen Sie, an den Empfindungslauten können wir heute noch diese Anpassung der sprachbildenden Kraft an die Umgebung ein bißchen studieren, wie die in konkreter Weise zum menschlichen Erleben sprechen: Pfui! Tratsch! Tralle walle! - Wie passen wir uns darin demjenigen an, was wir ausdrücken wollen! Wie anders ist es, wenn Sie nun in der Schule, ich will nicht einmal sagen Logik lernen oder Philosophie, sondern überhaupt eine heutige Wissenschaft. Da bekommen Sie wahrhaftig Wörter, wo Sie unter den Seelenkräften anderes zu Hilfe nehmen müssen als das, was sich im Muh zum Beispiel als eine Nachbildung von dem, was Sie von der Kuh hören, empfinden läßt. Wenn Sie das Muh aussprechen, dann empfinden Sie nach, was Ihnen da als Erlebnis auftritt.

Wenn Sie ein Wort aus einem fremden Sprachidiom hören, dann müssen Sie wahrhaftig etwas anderes tun, als aus dem Wortklang heraus das hören, was Sie hören sollen. Sie müssen die abstrahierende Kraft gebrauchen, Sie müssen die reine Begriffskraft gebrauchen; Sie müssen lernen, ideell vorzustellen. Daher hat sich ein Volk, das wie die mitteleuropäischen Völker ganz besonders fremde Elemente aufgenommen hat, durch diese Aufnahme fremder Elemente erzogen zur Kraft des ideellen Denkens. Und zwei Dinge kommen in diesem Mitteleuropa zusammen, wenn wir auf das Hochdeutsche Rücksicht nehmen: auf der einen Seite jene eigentümliche Innerlichkeit, die schon eine innerliche Lebensfremdheit ist, die durch das Ersteigen der dritten Stufe da ist, und auf der anderen Seite dasjenige, was mit dem fortwährenden Aufnehmen von fremden Elementen gegeben ist. Dadurch, daß diese zwei Dinge zusammenkommen, ist innerhalb des hochdeutschen Elementes jene stärkste ideelle Kraft entwickelt worden, die einmal in diesem hochdeutschen Elemente drinnen ist, jene Möglichkeit, zu den ganz reinen Begriffen hinaufzukommen und in den reinen Begriffen sich zu bewegen. Das ist einmal eine gewaltige Erziehung gewesen, die durch diese zwei Strömungen der Sprachentwickelung für das mitteleuropäische Sprachwesen zustande gekommen ist. Die Erziehung zum innerlichen wortlosen Denken - wo wir wirklich fortschreiten zu einem wortlosen Denken -, die ist in besonderem Maße in Mitteleuropa durch die eben charakterisierten Tatsachen erzeugt worden.

Das sind Dinge, die sich unmittelbar aus den Tatsachen ergeben, und wir verstehen gar nicht das hochdeutsche Sprachwesen, wenn wir es nicht in diesem Sinne betrachten, wenn wir es nicht durch die Lautmetamorphose hindurch und durch die Wortmetamorphose, durch die Aneignung fremder Wörter auf den verschiedenen Stufen, betrachten. Das wollte ich Ihnen heute darlegen zur Charakteristik der mitteleuropäischen Sprachen.

Third Lecture

The facts of life often lead to contradictions when viewed from the outside; but it is precisely when such contradictions are properly examined that one arrives at the deeper, essential connections. If you think about it thoroughly, you will find such a contradiction between what I explained to you in the first lecture here and recapitulated in the second, and what I then discussed yesterday using individual examples as an internal connection between European languages. Let us form in our minds the mental image of the two sets of facts characterized by this: On the one hand, we have pointed out that we find many intruders in the current inventory of our language; that we feel how, with Christianity coming from the south into our regions, other elements have been added to the original Germanic linguistic richness, which, in a sense, brought Christian mental images and Christian sentiments along with Christian words; so that these Christian words now exist in our language in the manner described. Then I spoke of other intrusions that are nevertheless also significant because they already belong to the scope of our language system; of those invasions that began around the 12th century, originating in Western Romance countries, and which also fall into a period in which the German linguistic genius had a transformative power. There it transforms what it receives from the West in its own way, transforming it in terms of sound and also in terms of meaning. I said at the time: Few people today realize that, for example, the word fein used in German is actually of French origin: fin, and that it only entered our language after the 12th century, having not been there before. I then pointed out how Spanish also penetrated at a time when the transformative power of the German language was no longer present, and how this transformative power was completely absent when elements of English penetrated the German language in the latter part of the 18th century, but especially in the 19th century. We see that words were continually adopted into Central Europe from Latin or Greek, via Latin, or again from the Western Romance languages. This is a fact that must lead us to say: our current vocabulary consists only partly of original elements and also contains words that were adopted later. But now I have again drawn your attention to the close relationship that exists between a whole series of languages. I have pointed out some Gothic forms and shown how these have been incorporated into the forms of our language; and in some places we have been able to show how the word in question can also be found in Latin or Greek. So while we must say: Our language has incorporated foreign elements , we must also say that our language is closely related to those languages from which it later incorporated something like foreign elements.

Now it is very easy to prove, albeit not in a very comprehensive sense, but using characteristic examples, that there is a close linguistic relationship across large areas of the earth. You only need to take something like naus, the Sanskrit word for ship. If you look up this word in Greek, you will find the same thing; if you look up this word in Latin, you will find navis. If you look up the same word in areas with a more Celtic influence, you will find the word nau, and if you look up the word in Old Norse, in the Old Scandinavian languages, you will find nor. The fact that such words have been discarded for German is of little significance. But we see that there is a relationship in the broadest sense, a relationship that we can prove for many things, across an extraordinarily large area spanning Europe and Asia. Take the Old Indian word aritras, we find the word again as eretmón in Greek; we find the same word again with certain omissions as remus in Latin; we find rame in Celtic areas, and we find ruodar in Old High German. We still have this word; it is our Ruder (oar). And so one could compile a large number of words that exist in transformations, in metamorphoses across wide areas of languages: for example, in Gothic, the Nordic-Scandinavian languages, the Frisian languages, Low German languages, in High German, also in Baltic idioms, in Lithuanian, Latvian, Prussian. Such affinities can also be found in Slavic languages; in Armenian, Iranian, Indian, Greek, Latin, and Celtic. Across the areas covered by these languages, we see how a primordial linguistic kinship exists. So we can easily form a mental image of how, in a sense, the causes of language formation across all these territories were similar in very ancient times, and that they only differentiated later on.

I said: These two sets of facts contradict each other; but it is precisely by observing such contradictions that we can penetrate more deeply into some aspects of life. For it is precisely such a series of phenomena that leads us to say: The development that humanity has undergone in the course of history does not take place, as is often the case, in a continuous manner, but rather in a kind of wave motion. For how else can you form a mental image of this whole process, which is expressed by these two seemingly contradictory facts, other than that there is a certain kinship between the populations across these vast territories; that these peoples remain so isolated for a certain period of time that they develop their own distinct languages; that there is therefore a period of isolation between peoples, alternating with a period in which one people influences another. This is, of course, a somewhat crude characterization of the matter; but it is only by looking at such an upward and downward movement that certain facts can really be explained. Now, if we consider the development of language in the two directions I have just indicated, we can gain a deeper insight into the nature of the development of peoples in general. One must only take into account, on the one hand — and we will now apply this to the development of the German language — the way in which certain elements of language develop, as it were, in isolation from the outside world, and how, in turn, foreign elements are absorbed and also contribute to all that can be expressed through language in terms of spirit and soul. We can already guess that these two elements must relate in very different ways to the spiritual and soul life of the people in question.

On the one hand, we can look at the extremely significant fact that there is a primordial kinship that strikes us particularly when we see that extremely important words are related, for example in Latin and in the older forms of the Central European languages. Latin verus: true; Old High German: wâr. If you take such striking examples as: velle = to want, or the Latin taceo = I am silent, for which the Gothic thahan occurs, you have to say to yourself: similar-sounding, i.e. linguistically related words prevailed in ancient times across large areas of Europe — and one could also prove this for Asia.

On the other hand, it is extremely strange that the inhabitants of Central Europe, from whom today's Germans emerged, also adopted foreign languages relatively early on. Even earlier than I have characterized it to you so far. There was a time when Europe was much more filled with the Celtic element than in the historical times that are usually referred to. However, the Celts were then pushed into western regions of Europe, and Germanic peoples moved into Central Europe, certainly from northern regions. Now, the Germanic peoples had already adopted foreign word elements from the Celts, who were now their western neighbors, just as they later adopted them from the south, from Latin. This means that the inhabitants of Central Europe, after developing more independently and the others developing on their own, later continuously adopted foreign language elements from the peripheral areas, which were originally linguistically related to them.

We have quite a few words that are no longer considered elegant, such as the word Schindmähre: this is a worn-out horse. This Schindmähre refers to an old word: Mähre, meaning horse; from which we still have the word Marstall (stable). However, this word is of Celtic origin and can be found among the Celts after they had already been pushed into Western Europe. And there is probably no metamorphosis that would have taken place in Central Europe on the one hand and then in the West on the other, but rather the Germanic peoples must simply have adopted this word from the Celts later on. A whole series of such words has been adopted, including those for which one has the power to transform. For example, in the name Vercingetorix, which is actually only partly a name, they have the word rix in it. Rix is originally a Celtic formation, was adopted by the Celts, meant to them the ruler, the powerful one, and has become our word rich, to be powerful through wealth. So here too, transformation not only from Latin, but also from Celtic at a time when the Central European linguistic genius still had an inner transformative power.

If one could trace the development of language far enough back in time—which is impossible—one would ultimately arrive at that primitive language-forming force of ancient times, in which languages arose from the relationship between consonants and vowels that I characterized yesterday. Languages arise in a primitive form. What then appears as differentiation in languages stems from the fact that what originally wants to form in the same way from human nature is expressed in the most diverse ways, depending, for example, on whether a tribe inhabits a mountainous region or a flat region. The larynx and its neighboring organs want to express themselves differently in a mountainous region than in a flat region, and so on.

Now, in the development of language, a peculiar phenomenon occurs, which we will consider using the example of the Indo-European languages. If we take the word two, we have duo in Latin. When this enters older forms of languages in Central Europe, we have the word two, and when we come to ourselves today, we have the word zwei. You can see the following in the metamorphosis of this word: This duo points us to an oldest stage that has been preserved in Latin; two is a later stage, and the newest stage that has formed is zwei. It would be very complicated to take the vowels into account. We take the consonants into account here and must say to ourselves: in the metamorphosis that this word has undergone, we see that the d becomes a t and the t becomes a z, in that order d-t-z. We can therefore see that a transformation of the sound takes place during the migration of the word. The German z corresponds to the th stage in other languages.

This is by no means something that has been artificially speculated. If one wanted to describe it in detail, one would of course have to explain it, but this pattern is something that corresponds to a natural course in the metamorphosis of language. Take, for example, the Greek word thyra. If you look at it as an old stage that has remained at an earlier stage, the next stage would have to be one that has the d. You will find this stage in the English word door. And the last transformed stage would have to go from d to t, following the hands of the clock. We have the High German word Tür. And so we can say: We can, in a sense, identify the oldest linguistic layer, in which the word metamorphoses always stand on one of these stages. The next metamorphosis stands on the next stage. And then we can identify a third stage in High German, which in turn stands on the next stage.

If the stage that finds its expression in Greek had a t, then English, which has remained behind, would have a th; High German, which would have advanced compared to English, would have a d.

Where High German has a z corresponding to the English th, the previous stage would have to have a t, and the previous Greek-Latin stage a d. We can prove that this exists.

So a word that would have a t in the second stage, in Gothic, for example, would have to have a z in the next stage. If we take a word that can be used here for the relationship of New High German to the next lower stage in Gothic, we have Zimmer; in Gothic, or in Old Saxon, which is at the same stage, Zimmer is timbar. From the z we have to go back to the £; I just want to give you the principle, you can look these things up yourself if you take a dictionary.

Just as this sequence is correct, you can also observe other essential metamorphoses in the language: if you compare words that have a b, this becomes a p in the next level, which in turn becomes a pf, ph or f in the next level, and this in turn becomes a b.

Similarly, there is also the connection g-k-ch (h) and back again to g. There are corresponding examples for this as well. So we can say the following: Greek-Latin retained the linguistic element at an earlier stage of metamorphosis. That which became Gothic moved up to a later stage. Much of what moved up to this stage is still preserved today, for example in Dutch. A final shift, which actually only took place in the 6th century AD, moved up another stage: the High German stage. So we can say: we would have to find the first stage, perhaps extending very far across Europe, perhaps only going back to 1500 BC. Then we find everything that dominates large areas, with the exception of the southern regions, where the oldest stage has remained – the second stage. And then, in the 6th century AD, the High German stage crystallizes. English and Dutch remain at the earlier stage, while High German crystallizes.

Now I ask you to note the following. Only once, so to speak, can the relationship that humans enter into with their environment, by forming words from consonants—that is, even now forming words entirely from their sense of language—only once can this happen in complete adaptation to the environment. Once the distant ancestors of the Central European languages had formed their wording for certain words after the first stage, let's say at the stage of z, they felt that the consonants had to be adapted to external phenomena; they formed the z according to the outside world. The next stages of progress can no longer be formed according to the outside world. Once the word is there, the next stages are transformed internally and are no longer formed in adaptation to the external world. The transformation is, in a sense, an independent achievement of the folk-soul element. First, at some stage, the wording is formed in harmony with the external world, then the following stages must only be experienced internally; one does not adapt to the external world again.

So we can say that the stage that remained in Greek and Latin expressed in many ways what is felt to be the adaptation of the language-forming element to the environment. The next stage, which developed in Gothic, Old Germanic, and so on, has gone beyond this immediate adaptation and undergone a spiritual transformation. This gives this language a much more spiritual nuance. With the first stage of transformation, the language element thus acquires a spiritual nuance. So that everything that has entered our sense of language as a result of our having gone through this second stage gives our language its inner quality.

This has developed slowly and gradually since the year 1500 BC. This kind of inner quality was characteristic of certain ancient times. However, as it was preserved for later times, it became more primitive. So that where it still exists today, in Dutch and English, it has become more of a primitive feeling for the wording.

Now, in the 6th century AD, High German has climbed to the third level. However, this is an even further departure from the original adaptation, a powerful inner process through which High German has developed from the earlier stage. While climbing to the second level has a spiritual effect, the third level takes one very far away from life. Hence the peculiar, often unworldly, abstract element of the High German language, which the High German language imposes on the German soul as something that many other people in Europe do not understand at all. Where, for example, the High German element has been used to a particular degree, as in Goethe and Hegel, it cannot be translated into English or the Romance languages. These are mere pseudo-translations. One has to make them because it is better to reproduce things than not to reproduce them. What lies in such words, which in the most eminent sense belong to the organism of High German, in terms of their very strong spiritualization, not merely their soulfulness, cannot simply be transferred into other languages. For they have no expression for it.

So climbing the second step is, on the one hand, imbuing language with soul, but also imbuing the inner life of the people in question with soul through language. Climbing the third step, which can be studied in High German, is more a distancing oneself from life, so that one can grasp such abstract heights through one's words as, for example, Hegel or, in certain cases, Goethe and Schiller have grasped. This is very much connected with this climbing of the third step through High German. Thus, you can see from the example of the High German language how, by means of the formation and development of language breaking away, as it were, from adaptation to the outside world, how, by means of it becoming an inner, independent process, that which is human and individual in the soul progresses, developing in a certain way independently of nature.

Thus, the Central European language element has gone through stages in which it first became spiritual and then intellectual, whereas in the first stage it was a kind of instinctive, animalistic adaptation to the outside world. Through other things, languages such as Greek and Latin then developed. If one takes these languages purely in terms of word forms, one must say that the word forms, the sound forms, are very strongly adapted to the environment. But the peoples who spoke these languages did not remain stuck in this primitive adaptation to their surroundings. Their languages, through all kinds of foreign influences that had a different effect than in Europe, from Egypt and Asia, became merely the outer garment for a culture that was brought to them, largely a mystery culture. The mysteries of Africa and Asia were brought to the Greeks and, to a certain extent, to the Romans, and they had the power to clothe the mysteries of Asia and Egypt in the language of the Greeks and Romans. Thus, these languages became outer garments for a spiritual content that was, as it were, instilled in them. This was a process that the languages of Central Europe and the Nordic European languages did not undergo; instead, they underwent the process just described. They did not simply absorb the spiritual at the first stage, but first developed to at least the second stage and were in the process of reaching the third stage: only then did Christianity, for example, penetrate them as a foreign spiritual element with new words. And the second stage had obviously already been reached when that Celtic element, which I spoke about today, penetrated. So we are dealing here with an inner transformation of the language. Only then does the spiritual influence come. In the case of Greek and Latin, however, we are not dealing with such a transformation of the language, but with an infusion of the spiritual into the first stage.

So we must look for the concrete factors that actually determine the character of individual peoples. Through such things, we find something like the transformation of languages and their relationship to spiritual life. Now, in New High German, we have, first of all, a language that, having ascended to the third stage of metamorphosis, has distanced itself far from life. But then this language also contains many words that have entered it in various ways, such as through Christianity from the south, through scholasticism from the south, and from the French and Spanish cultures from the west. These linguistic elements all entered later; they are now part of High German. All this shows how High German has evolved from its elements.

We do not feel the same way about something that is now accepted as a foreign element from another language as we do about a word, a sound connection that we ourselves form within a people in relation to nature. Let us consider the word Quelle (source). It is a word that, as we can perceive it, is so adapted to the essence to which it belongs that it is actually hard to imagine that we could call it anything else based on our perceptive nature. The word expresses everything that one experiences with the source. Thus, the original formation of speech sounds, speech words, and so on was such that they were completely adapted to the environment in terms of consonants and vowels. But when you hear, for example, the word essence or the word category or the word rhetoric, can you feel the connection with what the word originally means in the same way? No, as a people, we get the sound of the word and have to make an effort to grasp the concept on the wings of the sound of the word. It is impossible to go through this inner experience, which represents the harmony between the sound of the word and the concept, the feeling. There is a deep wisdom in the fact that, in this characteristic upward and downward development, a people takes on words from other peoples that it has not formed itself, words whose sound it hears but whose harmony with what is being described it does not experience. For the more such words are adopted, the more the people who adopt them need to call upon something very special in their soul life in order to cope with such things at all. One need only remember. You see, in the sounds of feeling we can still study a little today how the language-forming power adapts to its surroundings, how it speaks in a concrete way to human experience: Pfui! Tratsch! Tralle walle! – How we adapt ourselves in this to what we want to express! How different it is when you learn at school, I don't even want to say logic or philosophy, but any modern science at all. There you are given words where you have to draw on other soul forces than those that can be felt in the moo, for example, as a reproduction of what you hear from the cow. When you pronounce the moo, you empathize with what you experience there.

When you hear a word from a foreign language idiom, you really have to do something other than hear what you are supposed to hear from the sound of the word. You have to use your power of abstraction, you have to use your pure power of conception; you have to learn to form an ideal mental image. Therefore, a people such as the Central European peoples, who have absorbed foreign elements to a particular degree, have been educated by this absorption of foreign elements to the power of ideal thinking. And two things come together in this Central Europe, if we consider High German: on the one hand, that peculiar inwardness, which is already an inner alienation from life, which is present through the ascent of the third stage, and on the other hand, that which is given by the continuous absorption of foreign elements. Through the coming together of these two things, the strongest idealistic power has been developed within the High German element, that possibility of rising to the very pure concepts and moving within the pure concepts. This has been a tremendous education, brought about by these two currents of language development for the Central European language system. The education in inner wordless thinking – where we really progress to wordless thinking – has been produced to a particular degree in Central Europe by the facts just characterized.

These are things that arise directly from the facts, and we do not understand the High German language at all if we do not consider it in this sense, if we do not consider it through sound metamorphosis and word metamorphosis, through the appropriation of foreign words at various stages. That is what I wanted to explain to you today about the characteristics of the Central European languages.