The Genius of Language

GA 299

31 December 1919, Stuttgart

History of Language in Its Relation to the Folk Souls

You have seen that the most important concern of this course is to show how the history of language-forming originates in human soul qualities. Indeed, it is impossible to arrive at an understanding of the vocabulary of any modern language without understanding its inner soul nature. So I would like to add today some examples to show you how the phenomena of language are related to the development of the folk souls.

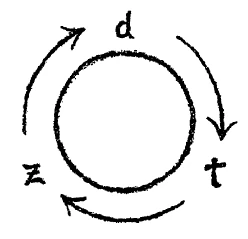

First let me call your attention to two words that belong together: Zuber ‘tub’ and Eimer ‘pail’. They are old German words; when you use them today, you are aware that an Eimer is a vessel with a single handle fastened on top in which something can be carried; Zuber has two handles. That is what they are today when we use the two words, Zuber and Eimer. To investigate the word Eimerwe have to go back a thousand years and find it in Old High German as the word ein-bar. You remember that I introduced you to the sound group bar (lecture 2), related to beran, ‘to carry’. Through the contraction of ein-bar ‘one carry’, Eimer ‘pail’ came about. We have it clearly expressed, transparently visible in the old form: the carrying with one handle, for bar is simply something to carry with. Zuber in Old High German is Zwei-bar ‘two-carry’, a vessel carried by two handles, a tub. [The origin of tub from Middle High German tubbe surely has to do also with ‘two’.] You see how words today are contractions of what in the older form were separate pieces or phrases that we no longer distinguish.

There are many such examples; we can put our minds to a few typical ones. Take the word Messer 'knife’. It goes back to Old High German mezzi-sahs. Mezzi is related to ezzan, the old form of essen, ‘to eat’, with an introductory /m/. As for sahs (sax is another pronunciation of the same word), we need to remember that when Christianity spread across southern Germany, the monks encountered the worship of three ancient divinities, one of whom was Sachsnot or Ziu, the God of War [still present in English Tuesday ‘Mars-day’]. Sachsnot means ‘the living sword’; sahs has the same sound configuration. Therefore in the word Messer you have the composite ‘eating sword,” the sword with which you eat.

Interesting, too, is the word Wimper [‘eyelash’ today, but seems to describe eyebrow], which goes back to wint-bra. Bra is the ‘brow’ and wint is something that ‘winds itself around’. You can picture it: the ‘curving brow’. In the contraction Wimper we no longer distinguish the single parts.

Another word that characterizes such contractions, where originally the relationships were felt perceptively, you know as the fairly common German word Schulze ‘Mayor’. When we look back at Old High German we find sculd-heizo. That was the man in the village to whom one had to go to find out what one’s debt (Schuld) was. He told a fellow who had been up to some kind of mischief what his fine would be. The person who had to decide, to say (heissen) what debt or fine was due was the Sculd-heisso, Schuld-heisser ‘debt namer’. This became Schulze. I am giving you these examples so that you can follow me as we trace the course of language development.

Something else can be observed in this direction, something that still often happens in dialects. In Vienna, for instance, a great deal of dialect has been retained in a purer state than in northern Germany, where abstractness came about quite early. The Austrian dialect goes back to a primitive culture, as far back as the tenth century. The language-forming genius with its lively image quality was still active in southern German areas but did not enter the northern German culture. There is a picturesque word in Vienna: Hallodri. That's ‘a rascal, a rowdy’, who likes to raise a ruckus, who's a trouble-maker, who's possibly guilty of a few minor offences. The Hallo in the word points to how a person shouts [like English Hello! with a touch of holler]. The ri has to do with the shouting person’s behavior; it is a dialect holdover from the Old High German ari, which became aeri in Middle High German, finally becoming weakened in modern German to the suffix -er [This corresponds exactly to -er in English, as in baker, farmer, storyteller] If you take the Old High German word wahtari, there at the end of it is the syllable you encountered in the Austrian dialect word Hallodri. It means somehow or other ‘being active in life'—that is the syllable ari; waht is ‘to watch'. The person who takes on the office of watching is the wahtari In Middle High German it became wachtaere, still with the complete suffix. Now in Modern German it is Wächter ‘watcher, watchman, guard’. The ari has become the syllable -er; in which you perceive very little of the original meaning: handling or managing something. This you should feel in words with the suffix -er; retained from ancient times, for example: The person who handles or manages the garden is the gartenaere, the gardener: It is an illustration of the way language today makes an effort to adapt sound qualities—everything I would call musical—slowly into abstractness, where the full sense of the sound can no longer be perceived, especially not in the full sense of the concept or its feeling quality.

The following is an interesting example. You know the prefix -ur ‘original, archetypal’ in the words Ursache ‘first cause, original cause’, Urwald ‘primeval forest, jungle’, Urgrossvater ‘great-grandfather, ancestor’, and so on. If we go back almost two thousand years in the history of our language, we find this same syllable in Gothic as uz In Old High German, about the year 1000 A.D. we find the same syllable as ar; ir; or ur. Seven hundred years ago it was ur and so it remains today, having changed rather early. As a prefix to verbs it has become weak. We say, for instance, to express something being announced, Kunde ‘message’; if we want to designate the first message, the original, the one from which the other messages arise, we say Urkunde ‘document, charter’. In verbs the ur is weakened to er. To augment the verb kennen ‘to know’; (cognate: ken) we do not say—as might have been possible—Urkennen, but rather erkennen ‘to understand, recognize’. Er has exactly the same level of meaning in such a word as ur does in urkunde. If I make it possible for someone to do a certain thing, I erlaube ‘allow’” him something. If I change this into a noun, in a certain situation, it becomes Urlaub ‘vacation’, something I give a person through my act of ‘allowing’. Another word formation related to all this is exceedingly interesting—you know the expression “to make land urbar" ‘arable’. Urbar is also related to beran (‘to bear’; see lecture 2). Urbaris the ‘primordial cause inducing the land to bear’. There is an analogous meaning in the word ertragen ur-bear, to yield, endure’. If you say nowadays something about the Ertrag des Ackers ‘the yield of one’s land’, you are using the same word as in urbar machen des Ackers ‘making the field yield its first crop’. Originally the word urbar was also used to say ‘work the land so that it bears enough, for instance, to pay its taxes or rent’. [Note: English acre has become a measurement, whereas Acker is the land itself. Arnold Wadler in his One Language takes this word back to Agros (Greek, ‘soil’), further back to Ikker (Hebrew, ‘peasant’), and finally to A-K-R (Egyptian, ‘earth-god’) to show how ancient words with a spiritual meaning descend through the ages to a sense that is more and more physical and abstract. ‘God’—‘human being’—‘land’—‘measurement’. A similar change occurs from Agni, Hindu god of fire, to Ignis (Latin, ‘fire’) and finally ignition, ‘part of an internal-combustion engine’.]

To study the prefixes and suffixes of a language is in every sense most interesting! For instance, there is the prefix ge- in numerous words. This goes back to the Gothic ga, in which one truly felt the gathering. [Here the best example is offered in English: Anglo-Saxon gaed, ‘fellowship’, related to gador in ‘together’.] Ga- carries the feeling of assembling, pushing together. In Old High German it became gi, and in modern German ge [Wadler once described the consonant as the musical instrument on which the vowel-melody is played, hence the ever-changing vowels in epochs of time and in comparable languages.]| When you put ge in front of the word salle or selle ‘room, hall’, you come to Geselle ‘fellow, journeyman’ a person who shares a room with another or sleeps in the same lodging with him. Genosse ‘comrade’ is a person who geniesst ‘enjoys’ something together with another.

I want to call your attention to what is characteristic in these examples. Someone who experiences within the sounds of a word the immediate feeling for its meaning surely has a different relationship to the word than does a person without that feeling. If you simply say Geselle because you've known what it means since childhood, it is a different thing than if you have a feeling for the room and the connection within the room of two or more people. This element of feeling is being thrown off; the result is the possibility of abstractness.

Another example is part of many of our words, the suffix - lich (English -ly) as in göttlich ‘divine, godly, and freundlich ‘friendly’. If you look for it two thousand years ago, you will find it in Gothic as leiks. It became lich in Old High German, related originally to leich and also leib ‘body’. I told you (see lecture 2, pages 32-33) that leich/leib expresses the form' (Gestald left behind when a person dies. Leichnam ‘corpse’ is really a somewhat redundant expression, a structure such as a child creates when it combines two similar sounding words like bow-wow or quack-quack, where the meaning arises through repetition. Dissimilar sounding words, however, may also be combined in this way, and such a combination is the word Leichnam. Leich, as we said, is the form that remains after the soul has left the body. Nam, in turn, derives from ham and ham is the word still preserved in Hemd ‘shirt’, meaning shroud or sheath, Hülle. Leichnam means therefore the form-shroud’ that we cast off after death. Hence there is a combination of two similar things, form’ and—somewhat altered—‘sheath’, put together like bow-wow.

Out of this leiks/leich our suffix -lich has developed. When we use the word göttlich ‘godly’, it points toward a form’ with its - lich, which is leiks ‘form’: a form that is godly or divine, ‘of the shape or form of God'. This is particularly interesting in the Old High German word anagilih, which still contains ana from the Gothic; ana means ‘nearly’, ‘almost’. Gilihis the form. Today’s word ähnlich ‘similar, analogous’ means what ‘almost has the form'.

This is a good example for studying not so much the history as more particularly the psychology of language. It still shows how nuances of feeling, in earlier times, were vividly alive in the words people used. Later this feeling, this emotional quality slowly separated from any language experience, so that whatever unites a mental picture with speech sounds has become a totally abstract element. I have just spoken about the prefix ge-, Gothic ga-. Imagine that the ‘gathering together’ of ga-, which is now ge-, could still be felt and were now applied to the element of form’, to the leich, then according to what we could feel historically, it could mean ‘agreement of form'. This meaning lives in the word like an open secret. Geleich = gleich means ‘forms that agree’, forms that act together’: gleich ‘very similar, identical, equal’.

Consider for a moment a word that unveils many secrets. Today we will look at it from only one point of view. It is Ungetüm ‘monster’. [In German the two dots over an /ä/, /ö/ or /ü/, called an Umlaut, change the quality and sound of the vowel.1See discussion of the umlaut in lecture 6, page 90. ] The /ü/ in Ungetüm was originally /u/ and this tum, if looked at separately, goes back to Old High German fuom, which is related to the verb tun ‘to do, bring about, achieve, bring into a relationship’. In every word containing the suffix -tum, the relationship of things working together can still be felt—as in Königtum ‘kingdomy', Herzogtum ‘dukedom, duchy'. The Ungetüm is a creature with whom no real working together is possible. Un, the prefix, denotes the ‘negative’; getum could be the ‘working together’.

We have numerous words, as you know, with the suffix -ig (English -y), such as feurig ‘fiery’, gelehrig ‘docile, teachable’, [cf. saucy; bony, earthy] and so on. This goes back to Old High German -ac or -ic and to Middle High German -ag or -ig. It signifies approximately what we describe with the adjective eigen ‘own, one’s own'. Hence, where the suffix -ig appears, it points to a kind of ownership. Feurig is feuereigen, something whose property is fiery’. I have told you that it is possible to observe how the genius of a language undergoes increasing abstractness, which is the result of this sort of contracting and what comes about then as the assimilation of sound elements, such as feurig from feuer-eigen.

It could be expressed like this: In very ancient stages of a people’s language development, the feelings were guided totally by the speech sounds. One could say language was made up only of differentiated, complicated images through the consonant sounds, picturing outer processes, and of vowel elements, interjections, expressions of feeling occurring within those consonant formations. The language-forming process then moves forward. Human beings pull themselves out, more or less, of this direct experience, the direct sensing of sound language. What are they actually doing as they pull themselves out and away? Well, they are still speaking but as they do so, they are pushing their speech down into a much more unconscious region than the one where mental pictures and feelings were closely connected with the forming of the sounds. Speech itself is being pushed down into an unconscious region, while the upper consciousness tries to catch the thought. Look closely at what is going on as soul-event. By letting the sound associations fall into unconsciousness, human beings have raised their consciousness to mental pictures (Vorstellen) and perceptions that no longer are immersed in language sounds and sound associations. Now people have to try to capture the meaning, a meaning somehow still indicated by the sounds but no longer as intimately connected with them as it had been. We can observe this process even after the original separating-out of the sound associations has taken place; just as people previously had related to the sounds, now they had to make a connection to words. By that time there had come into existence words with sound associations no one finds any relationship to; they are words connected through memory to the conceptual. There, on a higher level, words pass through the same process that sounds and syllables underwent earlier.

Suppose you want to say something about the people of a certain area, but you don't want to sound completely abstract. You wouldn't want to say “the human beings of Württemberg" [the German state where the lecture was being given]; that would be too abstract. And you probably wouldn't want to reach top level abstraction with “the inhabitants of Württemberg.” If you want to catch something more concrete than “human beings,” you might think of “the city and country people of Württemberg” (die Bürger und Bauern). This would denote not actually city people nor country people but something that hovers in between. In order to catch that hovering something, both words are used. This becomes especially clear and interesting when the two words, used to express a concept, approach from two sides and are quite far apart from each other, for instance when you say Land und Leute ‘land and people’. [Something similar in English: the world and his wife]. When you use such a phrase, what you want to express is something hanging between the two words that you are trying to approach. Take Wind und Wetter ‘wind and weather’: when you say it, you can't use just one word; you mean neither wind nor weather, but something that lies between, put into a kind of framework. [In English we have many similar double phrases from earliest times: might and main; time and tide; rack and ruin; part and parcel; top to toe; neither chick nor child—and many of them are alliterative, that is, repeating the same consonant at the beginning of both words.].

It is interesting to note that as language develops, such double phrases use alliteration, assonance, or the like. This means that the feeling for tone and sound is still playing its part; people who have a lively sense for language are still able, even today, to continue using such phrases and with them are able to capture a mental image or idea for which one specific word is not immediately available.

Suppose I want to describe how a person acts, what his habits are, what his essential nature is. I will probably hesitate to use just one word that would make him out to be a living person but passive—for I don't want to characterize him as living essentially a passive life nor on the other hand an active life; I want to deduce his activity out of his intrinsic nature. I can't say, his soul lebt ‘exists’; that would be too passive. Nor can I say, his soul webt ‘is actively in motion, weaves, wafts’; that would be too active. I need something in between, and today we can still say, Die Seele lebt und webt ‘Just as he lives and breathes'.

Numerous examples of this kind proceed from the language-forming genius. If you want to express what is neither Sang ‘song’ nor Klang ‘sound’, we say Sang und Klang ‘with drums drumming and pipes piping’. Or you might want to describe a medieval poet creating both the melody and the words of a song—people often wanted to say that the Minnesingers did both. One couldn't say Sie ziehen herum und singen ‘they wander about and sing’ but rather, Sie ziehen herum und singen und sagen ‘they wander about singing and telling’. What they did was a concept for which no single word existed. You see, such things are only what I would call latecomers or substitutes for the sound combinations we no longer quite understand. Today we form contractions of such phrases as Sang und Klang, singen und sagen, sound-phrases which in earlier times retained the connection between sound-content and the conceptual feeling element.

To take something very characteristic in this respect, look at the following example. When the ancient Germans convened to hold a court of justice, they called such a day tageding ‘daything’. What they did on that day was a ding We still use the expression Ding drehen, literally, ‘to turn a thing’; slang, ‘to plan something fishy'. A ding is what took place when the ancient Germans got together to make legal decisions. They called it a tageding. Now take the prefix ver-: it always points to the fact that something is beginning to develop (Anglo-Saxon for- used in forbear, forget, forgive, and so forth). Hence, the occurrences at the fageding began to develop further and one could say, they were being vertagedingt. And this word has slowly become our verteidigen ‘to defend, to vindicate’, with a small change of meaning. You see how the sound combination vertageding began to undergo the same process as the word combinations do later.

Thus we find that little by little the conceptual life digresses ever further from the pure life of language sounds. Consider the example of the Old High German word alawari. All-wahr, ganz wahr ‘completely true, altogether true’ was the original meaning, but it has become today's word albern ‘foolish’. Just think what shallowness of the folk soul you are looking into when you see that something with the original meaning of ‘altogether true’ has become ‘foolish’, as we hear and feel the word today. The alawari must have been used by tribes, I would say, who considered the appearance of human all-truth as something stupid and who favored the belief that a clever person is not alawari. Hence the feeling that ‘one who is completely honest is not very clever’, ie., albern ‘silly, foolish, weak-minded’. It has carried us over to something for which originally we had a quite different feeling.

When studying such shifts of meaning, we are able to gaze deeply into the language-forming genius in its connection with qualities of soul. Take our word Quecksilber ‘quicksilver, mercury’, for instance, a lively, fluid metal. Queck is the same word as Quecke ‘couch grass’, also called quick, quitch, twitch, or witch grass’, which has to do with movement, the same word as quick contained in the verb erquicken ‘to refresh, revive’; cognate, to quicken, ‘the quick and the dead’. This sound combination queck and quick, with the small shift to keck ‘bold, saucy’ originally meant ‘to be mobile’. If I said five hundred years ago 'er ist ein kecker Mensch’, I would have meant that he is a ‘lively person’, not one to loaf around, to let the grass grow under his feet, one who ‘likes work and gets going’. Through a shift of meaning, this keck has become ‘bold, saucy'. The path inward toward a soul characteristic led at the same time to an important change of meaning.

Another word frech originally meant kühn im Kampfe ‘bold in battle’. Only two hundred years ago frech ‘fresh, impudent, insolent’ meant a courageous person, someone not afraid to stand his man in a fight. Note the shift of meaning. Such shifts allow us to look deeply into the life and development of the human soul.

Take the Old High German word diomuoti. Deo/dio always meant ‘man-servant’; muoti is related to our word Mut ‘courage’; cognate, mood, but formerly it had a different meaning, to be explained today by attitude, the way we are attuned to the world or to other people. We can say that dio muoti actually signified the attitude of a servant, the mood a servant should have toward his master. Then Christianity found its way north. The monks wanted to tell the people something of what their attitude should be toward God and toward spiritual beings. What they wanted to express in this regard they could only do in relation to the feeling they already had for the ‘servant’s attitude’. And so diomuoti gradually became Demut ‘humility’. The religious feeling of humility derives from the attitude of a servant in ancient Germanic times; this is how shifts of meaning occur.

To study this process it is especially interesting to look at words, or rather the sound- and syllable-combinations where the shift of meaning arose through the introduction of Christianity. When the Roman clergy brought their religion to the northern regions of Europe, changes occurred whose fundamental significance can be outwardly understood only by looking at the shifts of meaning in the language. In earlier times before the advent of Christianity, there existed a well-defined master/servant relationship. About a person who had been captured in battle, put into service, and made submissive, his master—wishing to imply Der ist mir nützlich ‘he is useful to me'—would say Der ist fromm, das ist ein frommer Mensch ‘he is a pious man'. Only a last remnant of this word fromm exists today where, to put it a bit jokingly, it is only somewhat reminiscent of its original meaning in the phrase zu Nutz und Frommen ‘for use and profit’, that is, ‘for the greater good'. The verb frommen is combined here with ‘usefulness’, which originally was its identical meaning, but the idea of finding something useful is pointed out with tongue in cheek. The servant who was fromm was a most useful one. The Roman clergy did find that some people were more useful to them than others and these they called fromm ‘pious’. And so this word has come about in a peculiar way through the immigration of Christianity from Rome. With such words as Demut ‘humility’ and Frommsein ‘piety’ you can study some of the special impulses carried by Christianity from south to north.

To understand language and its development you have to pay attention to its soul element, to the inner experience that belongs to it. There exists in the forming of words what I characterized as the consonantal element on the one hand, the imitation of external processes, and on the other hand, the element of feeling and sensing, for instance, as interjections., when perceptions are expressed in their relationship to the external world. (See also expletives, lecture 3, p 48)

Let us consider a distinctly consonantal effect one can experience in one’s feeling for language, quite far along in its development.

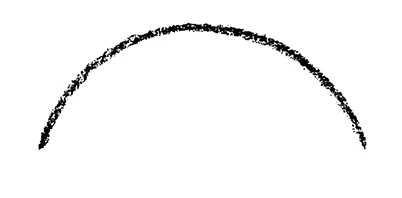

Suppose that someone is looking at this form I am drawing here. A simple person long ago would have had two kinds of feeling about it. Looking at the form from below, that person perceived it as something pressed inward; the feeling itself slowly grew into the sound formation we have in our word Bogen ‘bow, as in rainbow’. However, looking at the form from above downward and perhaps bending it out as much as possible (drawing it), what I see now, looking down, comes into speech as Bausch ‘hump, bunch, ball’. From below it is a Bogen; from above, it is a Bausch. The two words still contain something of our perceptive feeling. When you want to express what is contained in both words together but is no longer attached to our perception, and goes outward to describe the whole process, you may say in Bausch und Bogen, ‘in bump and bow’ [lock, stock and barrel’ is a similar English idiomatic phrase]. In Bausch und Bogen would be an imaginative phrase for this (pointing to the drawing), seen from above and below. You can apply these two points of view also in the moral or social realm, in closing a business deal with someone, so that the final outcome is considered from both inside and outside. Looking at it from within, the result is profit; from outside there is the corresponding loss. When you close a business deal, whether for profit or loss, you can say it's done in Bausch und Bogen; you don't have to pay attention to either of the single components (as in the English phrase for better or for worse).

With all this I have wanted to explain to you that by following the development of speech sound elements as well as words and phrases, pictures will arise of the folk soul development as such. You will be able to discover many things if you trace along these lines the movement from the concrete life of speech sounds to the abstract life of ideas. You need only to open an ordinary dictionary or pick up words from the talk going on around you, and then trace the words as we have done. Especially for our teachers I want to mention that it is extraordinarily stimulating to point out such bits of language history occasionally to the children right in the middle of your lesson; at times it can truly enlighten a subject and also stimulate more lively thinking. But you must remember that it’s easy to get off on the wrong track; one must be exceedingly careful, for—as we've seen—words pass through a great variety of metamorphoses. It is very important to proceed conscientiously and not seize on superficial resemblances in order to form some theory or other.

You will see from the following example how necessary it is to proceed cautiously. Beiwacht ‘keeping watch together’ was originally an honest German word, like Zusammenwacht ‘together watch’, used to describe people sitting together and keeping watch. It is one of the words that did not wander from France into Germany as so many others did, but it somehow managed to wander into France, as did the word guerre (French, ‘war’) from the German Wirren ‘disorder, confusion’. In early times Beiwacht got to France and there became bivouac. And then it wandered back again, in one of the numerous treks of western words moving toward German regions after the twelfth century. When it returned, it became Biwak ‘an encampment for a short stay’. Thus an original German word wandered into France and then returned. In between it was used very little. Such things can happen, you see: Words emigrate, then it gets too stuffy for them in the foreign atmosphere—and back home they come again. There are many sorts of relationships like this that you can discover.

Vierter Vortrag

Sie haben gesehen, daß in diesen Betrachtungen es zunächst darauf ankommt, die sprachgeschichtlichen Momente auf das Seelische zurückzuführen. Man kann in der Tat kein Verständnis des Vorganges der Sprachbildung und auch kein Verständnis des heutigen Bestandes irgendeines Sprachgebildes bekommen, wenn man nicht auf das seelische Element eingeht. Und ich will auch heute noch — um das in den nächsten Stunden dann durch speziell Sprachgeschichtliches zu illustrieren — einiges von demjenigen vorführen, was Sie von der Betrachtung sprachgeschichtlicher Erscheinungen zu der Entwickelung der Volksseelen leiten kann.

Da möchte ich Ihre Aufmerksamkeit hinlenken auf zwei zusammengehörige Wörter: Zuber und Eimer. Wenn Sie heute diese Wörter, die alte deutsche Wörter sind, nehmen, so werden Sie aus dem Gebrauch dieser Wörter darauf kommen, daß ein Eimer ein Gefäß ist, in dem man etwas trägt, und das einen einzigen, oben angebrachten Henkel hat; ein Zuber ist das, was zwei Henkel hat. Diese Tatsache liegt heute vor und sie kommt zum Ausdruck in den beiden Wörtern: Zuber und Eimer. Untersuchen wir das Wort Eimer, so können wir über tausend Jahre zurückgehen: wir finden es im Althochdeutschen oder in einem noch früheren Stadium und finden das Wort einbar. Nun erinnern Sie sich, daß ich Ihnen ja den Lautzusammenhang bar vorgeführt habe. Er hängt zusammen mit beran: tragen, und durch Zusammenziehung des einbar ist Eimer entstanden. Wir haben also deutlich ausgedrückt, so daß man es durchsichtig in der alten Form erschauen kann, das Tragen mit einem Griff; denn bar ist einfach etwas zum Tragen. Zuber heißt im Althochdeutschen zwiebar, etwas, was man durch zwei trägt, also ein Gefäß mit zwei Griffen. So sehen wir, wie heutige Wörter durch Zusammenziehungen entstanden sind, die wir in der alten Form noch auseinandergelegt finden, was wir jedoch heute im Worte nicht mehr unterscheiden können.

Ähnliche Dinge können wir auch bei anderem Sprachmaterial beobachten. Wollen wir uns ein paar charakteristische Erscheinungen vor die Seele führen. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel das Wort Messer. Das Wort führt zurück auf das althochdeutsche mezzisahs. Mezzi ist mit einem vorlautenden M nichts anderes, als was zusammenhängt mit ezzi, essen — ezzan, die alte Form für essen. Nun aber sahs, sax könnte man auch sagen in anderer Aussprache. Sie brauchen sich nur zu erinnern: Als sich das Christentum über Süddeutschland ausbreitete, da fanden die Mönche dort noch die ältere Verehrung für jene drei Gottheiten vor, wovon die eine die Gottheit Saxnot war; das ist der Kriegsgott Ziu. Saxnot ist die Zusammensetzung für das lebende Schwert, und sahs ist derselbe Lautzusammenhang. So daß Sie in dem Wort Messer das zusammengesetzte Wort Essensschwert haben: das Schwert, mit dem Sie essen.

So ist auch interessant das Wort Wimper. Das führt zurück auf wintbra. Bra = die Braue, und wint ist das sich Windende. Sie sehen hier anschaulich: die sich windende Braue. Im zusammengesetzten Wort Wimper unterscheiden wir das nicht mehr.

Nun noch ein charakteristisches Wort für solche Zusammenziehungen, wo ursprünglich noch gefühlte Zusammenhänge vorliegen. Sie kennen das nicht so selten vorkommende deutsche Wort Schulze. Gehen wir zurück ins Althochdeutsche, so finden wir dafür das Wort sculdheizo. Das war der Mann, zu dem man im Dorfe ging, daß er einem sagte, was man für eine Schuld habe, der einen aufmerksam machte, wenn man etwas ausgefressen hat. Der Mann, der zu entscheiden, zu heißen hat, was man für eine Schuld habe, der sculdheizo, Schuld-heißer, das ist der Schulze geworden. Ich will diese Beispiele einmal hinstellen, damit Sie mir folgen können, wie der Gang der sich fortentwickelnden Sprache ist.

Man kann nach dieser Richtung auch noch etwas anderes beobachten. Nehmen wir einmal etwas an, was im Dialekt leicht noch vorkommt. In Wien zum Beispiel hat sich ja manches Dialektische reiner erhalten als in Norddeutschland, wo die Abstraktion früh Platz gegriffen hat. Und dies geht zurück bis in die primitive Kultur, die bis ins 10. Jahrhundert hineinreicht. In die nordische Kultur hat sich das nicht eingeschoben, was in süddeutschen Gegenden erhalten geblieben ist an sprachbildendem Genius, dem man noch vielfach anmerkt, wie alte Formen des Sprachwirkens in ihm auftreten. So gibt es zum Beispiel ein anschauliches Wort in Wien, das heißt der Hallodri. Das ist einer, der gern Unfug treibt, der viel Schwierigkeiten macht, der sich unter Umständen Ausschweifungen, wenn auch nicht gerade außerordentlich bedenklichen, hingibt. Das Hallo weist hin auf das, was er tut; dann auf sein Gebaren weist die Endsilbe ri hin. Dieses ri ist noch ein dialektischer Überrest von dem althochdeutschen ari, das zum mittelhochdeutschen aere geworden ist, und das sich ganz abgeschwächt hat im Neuhochdeutschen in die Endsilbe er. Nehmen Sie also zum Beispiel ein althochdeutsches Wort: wahtari. Da haben Sie auch diese Silbe, haben das, was man im österreichischen Dialekt in dem Hallodri empfindet. Dieses Auftreten im Leben mit irgend etwas, das liegt in der Endsilbe ari, und wath ist das Wachen. Derjenige, der es mit dem Amt des Wachens so macht, das ist der wathari; im Mittelhochdeutschen wird es wahtaere, also noch mit voller Endsilbe; im Neuhochdeutschen ist es Wächter. Es ist zur Silbe er geworden, der man nurmehr wenig anfühlt von dem, was man bei dem ari empfunden hat: das Hantieren mit der Sache. In allen Wörtern, die diese Endsilbe er haben, sollte man daher fühlen, wenn man sich wieder durchdringt mit dem, was aus alten Zeiten erhalten ist, dieses Hantieren mit einer Sache. Derjenige, der im Garten hantiert, ist der gartenaere, unser heutiger Gärtner. Sie sehen daraus, wie die Sprache bemüht ist, Klangvolles, ich möchte sagen, Musikalisches in Abstraktes allmählich umzuwandeln, bei dem nicht mehr der volle Inhalt des Klanges nachempfunden wird und namentlich nicht mehr im Zusammenhang mit dem vollen Inhalt der Vorstellung oder der Empfindung.

Ein interessantes Beispiel ist das folgende: Sie kennen heute die Silbe ur in Ursache, Urwald, Urgroßvater und so weiter. Gehen wir etwa zwei Jahrtausende in unserer Sprachentwickelung zurück, so haben wir gotisch dieselbe Silbe als uz vorhanden; gehen wir ins Althochdeutsche zurück, also etwa ins Jahr 1000, so haben wir dieselbe Silbe als ar, ir, ur. Vor siebenhundert Jahren ist es noch immer ur und heute auch. Also verhältnismäßig früh hat sich diese Silbe umgewandelt. Nur bei Zeitwörtern hat sie sich abgeschwächt. Wir sagen zum Beispiel, indem wir dasjenige, was bekanntmacht, ausdrücken: Kunde. Wollen wir aber auf die erste Kunde hinweisen, auf diejenige, von der die andere Kunde ausgeht, so sagen wir Urkunde. Nun schwächt sich das ur für die Verben ab in er, so daß, wenn wir das Verbum kennen bilden, wir nicht sagen, wie es auch möglich wäre, urkennen, sondern erkennen; aber das er ist genau von demselben Bedeutungswert wie das ur in Urkunde. Wenn ich jemandem möglich mache, daß er irgend etwas tue, dann erlaube ich ihm irgend etwas; wenn ich das in einem bestimmten Falle zum Hauptwort mache, so wird daraus das Wort Urlaub, den ich ihm gebe durch mein Erlauben. Nun ist noch eine Bildung, die an alles das anklingt, außerordentlich interessant. Sie kennen das Wort: einen Acker urbar machen. Dieses urbar hängt auch mit beran zusammen, tragen machen. Urbar ist das ursprüngliche, das erste Tragenmachen eines Ackers. Sie haben da, ich möchte sagen, eine Bedeutungsanalogie in dem heute noch vorhandenen Wort ertragen. Wenn Sie heute sagen: Ertrag des Ackers —, dann ist dies dasselbe Wort wie das Urbarmachen des Ackers = das erste Erträgnis des Ackers. Und man hat ursprünglich das urbar auch dafür gebraucht, wenn man sagen wollte: den Acker so bearbeiten, daß er etwas tragen kann, zum Beispiel seinen Zins, seine Steuer.

Das Studium der Vor- und Nachsilben, die in unseren Worten auftreten, ist überhaupt außerordentlich interessant. So haben wir zum Beispiel in zahlreichen Wörtern die Vorsilbe ge. Sie führt zurück auf ein gotisches ga. In diesem gotischen ga wurde noch durchaus das Zusammenziehende gefühlt; ga hat etwa die Gefühlsbedeutung des Zusammenziehens, Zusammenschiebens. Das wurde dann im Althochdeutschen gi und im Neuhochdeutschen eben ge. Wenn Sie dann das auf anderen Wegen gebildete Wort salle, selle, haben, und Sie setzen das ge voran, Geselle, so haben Sie einen Menschen, der mit einem anderen das gleiche Zimmer bewohnt oder im gleichen Saal mit ihm schläft: das ist dann der Geselle. Genosse ist derjenige, der mit dem anderen das gleiche genießt.

Ich mache Sie hier schon aufmerksam auf das durch diese Beispiele charakteristisch Hindurchgehende. Man muß zum Wort in anderer Weise stehen, wenn man im Laute darinnen noch ein unmittelbares Gefühl hat von dem, was es bedeutet, als wenn man dies nicht mehr hat. Wenn man einfach ausspricht: Geselle, weil man sich von Kindheit an gemerkt hat, Geselle bedeutet dieses oder jenes, so ist es doch ein anderes, als wenn man dabei noch das Gefühl hat des Saales und bei Geselle eben diesen Zusammenhang des Saales mit zwei oder mehreren Menschen. Dieses Gefühlselement wird abgeworfen. Dadurch ist erst die Möglichkeit des Abstrahierens vorhanden.

Nun haben Sie zum Beispiel in vielen unserer Worte die Nachsilbe lich: göttlich, freundlich. Wenn Sie dieses lich aufsuchen vor zweitausend Jahren, so haben Sie es im Gotischen als leiks. Aber dieses gotische leiks, das dann althochdeutsch lich wird, das ist urverwandt mit leich und auch mit leib; und ich habe Ihnen schon gesagt, daß leich-leib ausdrückt die Gestalt, die zurückgeblieben ist, wenn der Mensch gestorben ist. Leichnam ist eigentlich schon etwas wie eine tautologische Bildung, wie eine Bildung von der Art, wie sie etwa ein Kind bildet, wenn es zunächst zwei ganz gleichlautende Wörter hat und sie zusammenstellt: wau-wan, muh-muh, wobei in der Wiederholung die Bedeutung aufgestellt wird. Es können aber auch nichtgleiche Laute zusammengestellt werden; und solch eine Zusammenstellung haben Sie zum Beispiel im Worte Leichnam. Leich ist eigentlich schon die Gestalt, welche zurückbleibt, wenn der Mensch von dem Seelischen verlassen ist; nam führt aber zurück auf ham, und ham ist das Wort, das erhalten geblieben ist noch in Hemd und heißt Hülle; so daß Leichnam die Gestalten-Hülle, das Gestalten-Hemd ist, das wir abgeworfen haben nach dem Tode. Es sind also zwei ähnliche Dinge: Gestalt - und das etwas verschobene Hülle, zusammengestellt wie wauwau. Nun ist aber aus diesem leiks, leich unsere Nachsilbe lich gebildet. So daß Sie also sehen: wenn Sie das Wort göttlich bilden, so muß dieses auf eine Gestalt hindeuten; denn das lich ist leiks: Gestalt. Ich weise da auf eine Gestalt hin, die das Göttliche ausdrückt; also gottgestaltet würde göttlich sein. Das ist besonders interessant zum Beispiel zu beobachten, wenn wir das althochdeutsche Wort anagilih ins Auge fassen. Da haben wir noch drinnen eben das aus dem Gotischen stammende ana, und ana ist: nahezu, fast; gilih ist die Gestalt. Was also ähnlich ist, das ist dasjenige, was fast die Gestalt hat. Das wird also, wenn es ein neuhochdeutsches Wort wird, zu ähnlich.

Gerade bei diesem Beispiel können Sie etwas studieren, was zunächst nicht rein sprachgeschichtlich, sondern, ich möchte sagen, sprachpsychologisch ist, weil es Ihnen noch zeigen kann, wie die Gefühlswerte in den Wörtern leben, wie aber diese Gefühlswerte allmählich im menschlichen Erfühlen sich loslösen, und dasjenige, was die Vorstellung noch verknüpft mit den Lauten, zu einem ganz abstrakten Element wird. Ich habe Ihnen die Vorsilbe ge, gotisch ga vorgeführt. Denken Sie also, man fühle das noch, dieses Zusammenwirken in ga, was jetzt ge wird, und man wendet das an auf die Gestalt, auf das leich; dann würde ich empfindungsgeschichtlich sagen: zusammenstimmende Gestalt. Es lebt darin, ohne daß es sich ausspricht. Geleich, gleich würde also sein: zusammenstimmende Gestalten, zusammenwirkende Gestalten, geleich = gleich.

Betrachten Sie einmal ein Wort, das manche Geheimnisse enthüllt wir wollen es heute nur nach einer Seite hin betrachten -, betrachten Sie unser Wort Ungetüm. Dieses ä ist nur der Umlaut für ein ursprüngliches u: Ungetum; aber das tum, das wir da loslösen, geht zurück auf ein althochdeutsches tuorm, und dieses tuom hängt zusammen mit dem Worte tun: zustande bringen, machen, in ein Verhältnis bringen. In allen Wörtern, wo dieses tum zur Nachsilbe geworden ist, kann man eigentlich noch nachfühlen, daß da etwas von einem zusammenwirkenden Verhältnis enthalten ist: Königtum, Herzogtum, Ungetüm. Ungetüm ist dasjenige, wobei kein ordentlich zusammenwirkendes tum entsteht: das #2 negiert das Zusammenwirken; das getum wäre das Zusammenwirken selber.

Zahlreiche Wörter haben wir, wie Sie wissen, mit der Nachsilbe ig: feurig, gelehrig und so weiter. Das geht zurück auf ein althochdeutsches ac oder auch ic, auf ein mittelhochdeutsches ag, ig, und das ist eigentlich die Wiedergabe von dem, was etwa eigenschaftswörtlich eigen heißt, es ist ihm eig. Wo also die Nachsilbe ig auftritt, da deutet sie auf ein eigen hin. Feurig = feuereigen, dem das Feuer eignet. Ich habe Ihnen gesagt, daß wir also beobachten können, wie durch solche Zusammenziehungen und im Zusammenziehen erfolgende Umgestaltungen der Lautbestände der Abstraktionsprozeß erfolgt, den der Sprachgenius durchmacht.

Man könnte das so ausdrücken: In sehr, sehr frühen Zeiten der Sprachentwickelung eines Volkes lehnt sich der Mensch mit seiner Empfindung ganz an den Laut an. Man möchte sagen: Die Sprache besteht eigentlich nur aus differenzierten, komplizierten Bildern in den konsonantischen Lauten, in denen man nachbildet äußere Vorgänge, und aus darinnen vorkommenden Interjektionen, Empfindungslauten in den vokalischen Bildungen. Nun schreitet der sprachbildende Prozeß fort. Der Mensch hebt sich gewissermaßen heraus aus diesem Miterleben, aus diesem empfindungsmäßigen Miterleben des Lautlichen. Was tut er denn da, indem er sich heraushebt? Er spricht ja noch immer; aber indem er spricht, wird das Sprechen in eine viel unterbewußtere Region hinuntergestoßen als das früher war, wo die Vorstellung, das Empfinden noch zusammenhing mit der Lautbildung. Es wird das Sprechen selbst in eine unterbewußte Region hinuntergeworfen. Das Bewußtsein sucht mittlerweile den Gedanken abzufangen. Beobachten Sie das wohl als einen Vorgang der Seele. Dadurch, daß man den Lautzusammenhang unbewußt macht, erhebt man sich mit dem Bewußtsein zu dem nicht mehr im Laut und Lautzusammenhang allein gefühlten Vorstellen und Empfinden. Man sucht also etwas zu erhaschen, worauf der Laut zwar noch deutet, was aber nicht mehr so innig wie früher mit dem Laut zusammenhängt. Solch einen Vorgang kann man auch dann noch beobachten, wenn das ursprüngliche, ich möchte sagen, Sich-Herausschälen aus den Lautzusammenhängen schon vorbei ist, und man dasselbe, was man früher mit Lautzusammenhängen gemacht hat, jetzt mit Wortzusammenhängen machen muß, weil schon Wörter entstanden sind, bei denen man nicht mehr den Lautzusammenhang voll fühlt, bei denen man schon mehr gedächtnismäßig den Lautzusammenhang mit dem Vorstellungszusammenhang hat. Man macht da auf einer höheren Stufe denselben Prozeß, den man früher mit Lauten und Silben gemacht hat, mit Wörtern durch.

Nehmen Sie an, Sie wollten ausdrücken die menschlichen Wesen einer bestimmten Gegend, Sie wollten noch nicht fortschreiten zur völligen Abstraktion, so daß Sie zum Beispiel sagen würden: Die menschlichen Wesen Württembergs. Das würden Sie noch nicht sagen wollen, das würde noch zu abstrakt sein. Man hätte sich noch nicht aufgeschwungen, nehmen wir an, zu so starken Abstraktionen wie: Die Menschen Württembergs. Würde man dasselbe, was man da später durch dieses: Die Menschen Württembergs ausdrückt, abfangen wollen durch Konkreteres noch, dann würde man sagen: Die Bürger und Bauern Württembergs. Man sagt dieses, indem man dasjenige meint, was weder Bauer noch Bürger ist, oder beides, was aber gewissermaßen dazwischen schwebt. Um dieses abzufangen, was dazwischen schwebt, gebraucht man beide Wörter. Das wird insbesondere interessant und deutlich, wenn die beiden Wörter, die man gebraucht, um einen Begriff auszudrücken, den man dadurch bezeichnet, daß man sich ihm gleichsam von zwei Seiten nähert, wenn die beiden Wörter weiter voneinander abstehen, zum Beispiel, wenn man sagt: Land und Leute. Wenn man dieses sagt, dann liegt dasjenige, was man sagen will, dazwischen, und man nähert sich ihm. Oder: Wind und Wetter. Wenn Sie dieses sagen, so meinen Sie etwas, was Sie nicht durch ein Wort ausdrücken, was weder Wind noch Wetter ist, sondern was dazwischen liegt, was Sie aber einfassen, indem Sie Wind und Wetter gebrauchen.

Nun ist es interessant, daß sich im Laufe der Sprachbildung solche Zusammenstellungen so ausdrücken, daß sie irgendwie alliterieren, assonieren oder dergleichen. Daraus ersehen Sie, daß das Lautempfinden, das Tonempfinden in diese Dinge doch noch hineinspielt. Und wer ein lebendiges Sprachgefühl hat, kann ja heute noch solche Dinge fortsetzen, kann durch Ähnlichlautendes dazwischenliegende Vorstellungen abfangen, für die man zunächst nicht das unmittelbare Wort hat. Nehmen Sie an zum Beispiel, ich will am Menschen ausdrücken so etwas wie sein Verhalten, wie es ihm habituell, wie es ihm wesenhaft eigen ist. Wenn ich Anstoß daran nehme, da bloß ein Wort zu gebrauchen, das den Menschen als ein passiv Lebendiges hinstellt — weil ich ihn in seinem wesenhaften Sich-Äußern, Sich-Offenbaren, nicht als passiv Lebendiges hinstellen, aber auch nicht bloß tätig hinstellen will, sondern die Tätigkeit ableiten will von seinem Wesen -, da kann ich nicht sagen: Die Seele eines Menschen lebt - das wäre mir zu passiv; ich kann auch nicht sagen: Die Seele des Menschen webt -, das wäre mir zu aktiv. Ich brauche etwas, was dazwischen ist, und sage heute noch: Die Seele lebt und webt. Aus dem sprachbildenden Genius heraus finden sich solche Dinge zahlreich. Denken Sie sich zum Beispiel, man will ausdrücken, was weder Sang noch Klang ist, so sagt man Sang und Klang. Oder man will beim mittelalterlichen Dichter ausdrücken, daß er den Ton und Text vorbringt, das wollte man oft ausdrücken, daß die Dichter Ton und Text vorbrachten, da konnte man nicht sagen: Sie ziehen herum und singen -, sondern: Sie ziehen herum und singen und sagen. Das, was sie eigentlich taten, das war ein Begriff, für den das Wort nicht da war. — Sehen Sie, solche Dinge, die sind nur, ich möchte sagen, die Spätlinge für das, was früher mit heute nicht mehr durchsichtigen Lautzusammenhängen geschehen ist. Wir bilden gewissermaßen mit Worten wie Sang und Klang, singen und sagen, noch Zusammenziehungen, die früher mit solchen Lautbeständen gemacht worden sind, welche noch den Zusammenhang hatten zwischen dem Lautbestand und dem Vorstellungs- oder Empfindungselement.

Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel, um sich ein ganz Charakteristisches nach dieser Richtung vorzuführen, das Folgende: Wenn die alten Deutschen zusammenkamen und Gerichtstag hielten, dann nannten sie so einen Tag tagading. So etwas, was sie taten, das war ein ding. Heute haben wir noch Ding drehen. Ein ding ist dasjenige, was da geschah, wenn die alten Deutschen zusammen waren. Man nannte es tagading. Nun nehmen Sie die Vorsilbe ver; die weist immer darauf hin, daß etwas in die Entwickelung eintritt. Wenn also das, was auf dem Tageding geschah, in die Entwickelung eintritt, dann konnte man sagen: es wurde vertagedingt. Und dieses Wort ist so nach und nach zu unserem verteidigen geworden; mit etwas Bedeutungswandel ist unser verteidigen daraus geworden. Und so sehen Sie, wie hier noch im Lautbestand vertagedingen dasselbe sich vollzieht, was sich später durch die Wortbestände vollzieht.

Da kommen wir dann nach und nach dazu, daß das Vorstellungsleben noch weiter abirrt von dem bloßen Lautleben. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel so etwas wie das althochdeutsche alawari. Das würde die Bedeutung haben von: ganz wahr. Daraus ist unser Wort albern geworden. Denken Sie sich nun einmal, in welche Tiefen des Volksseelischen Sie hineinschauen, wenn Sie erblicken, daß etwas, das ursprünglich die Bedeutung hatte des Ganzwahren, wenn das albern wird, so wie wir heute das Wort albern empfinden. Da muß durchgehen die Anwendung des Wortes alawari durch, ich möchte sagen, Stämme, die das Auftreten des Menschen in der Eigenschaft des Ganzwahren als etwas Verächtliches finden, die sich dem Glauben hingeben, daß der Schlaue nicht alawar: ist. Dadurch überträgt sich die Empfindung: wer ganz wahr ist, ist kein Schlauer -, auf das, wofür ursprünglich eine ganz andere Empfindung angewendet worden ist; und so verschiebt sich die Bedeutung des ganz wahr in albern.

Wir können, wenn wir den Bedeutungswandel studieren, tief hineinschauen in den sprachbildenden Genius im Zusammenhang mit dem Seelischen. Nehmen Sie zum Beispiel unser Wort Quecksilber: dies ist das bewegliche Metall. Dieses Queck ist ganz dasselbe Wort wie zum Beispiel, sagen wir in Quecke, das auch Beweglichkeit bedeutet, oder dasselbe Wort, das in erquicken drinnen ist. Dieser Lautzusammenhang: queck und quick — mit einer kleinen Lautverschiebung: keck -, der bedeutete ursprünglich: beweglich sein. Würde ich also von einem von Ihnen vor 500 Jahren gesagt haben: er ist ein kecker Mensch, so würde ich ausgedrückt haben: er ist ein beweglicher Mensch, der nicht auf seiner faulen Haut liegt, sondern der arbeitsam ist, der sich umtut. Durch Bedeutungswandel ist das zu dem heutigen Wort keck geworden. Da ist die Verseelischung zu gleicher Zeit der Weg zu einem sehr bedeutsamen Bedeutungswandel. So finden wir ein Wort, welches ursprünglich kähn im Kampfe ausdrückt. Wir brauchen nur etwa fünfhundert Jahre zurückzugehen, so heißt das Wort kühn im Kampfe: frech. Ein frecher Mensch im Sinne früherer Zeiten würde bedeuten: ein kühner Mensch, ein Mensch, der sich nicht scheut, im Kampfe gehörig aufzutreten. Hier haben Sie den Bedeutungswandel. Diese Bedeutungswandel, die lassen uns wirklich tief in das seelische Leben in seiner Entwickelung hineinschauen. Nehmen Sie das althochdeutsche diomuoti. Deo, dio bedeutet immer Knecht, muoti, was verwandt ist mit unserem Mut, aber früher eine andere Bedeutung hatte, ist heute nur wiederzugeben, wenn wir sagen: Gesinnung, die Art und Weise, gegen die Außenwelt oder gegen andere Menschen gestimmt zu sein. So können wir sagen: diomuoti hatte die Bedeutung von richtiger Knechtsgesinnung, die Gesinnung, die ein Knecht gegen seinen Herrn haben soll. Nun drang das Christentum ein. Die Mönche wollten den Menschen da etwas sagen, was sie haben sollten als die Gesinnung gegen Gott und gegen geistige Wesen. Sie konnten das, was sie ihnen da sagen wollten, nur dadurch zum Ausdruck bringen, daß sie anknüpften an eine Empfindung, die man schon hatte für diese Knechtsgesinnung. So wurde dieses diomuoti nach und nach zur Demut. Die Demut der Religion ist ein Nachkomme der Knechtsgesinnung der alten germanischen Zeit. So geschehen die Bedeutungswandel.

Überhaupt ist es gerade interessant, die Bedeutungswandlungen der Worte, oder besser Laut- und Silbenzusammenhänge, zu studieren, welche die Umänderungen der Bedeutung durch die Einführung des Christentums erfahren haben. Da ist manches vorgegangen, als das römische Priestertum das Christentum nach den nördlichen Gegenden gebracht hat, manches, das man eigentlich nur in seiner Urbedeutung äußerlich erkennt, wenn man auf den Bedeutungswandel der Worte sieht. Wenn in alten Zeiten, wo es noch kein Christentum gab, wo es aber ein ausgeprägtes Verhältnis gab des Herrischen zum Dienerischen, der Herr sagen wollte von irgendeinem Menschen, den er sich dienstbar, knechtbar gemacht hatte, den er erobert hatte: Der ist mir nätzlich, dann sagte er: der ist fromm, das ist ein frommer Mensch. Dieses Wort haben Sie heute nur noch in einem letzten Rest vorhanden - wo es gewissermaßen, um ein bißchen schalkhaft zu sein, an seine ursprüngliche Bedeutung: nützlich sein, erinnert —,in dem Ausdruck: zu Nutz und Frommen. Wenn man dieses sagt, dieses zu Nutz und Frommen, da ist zwar das Wort zusammengestellt mit dem Nutzen, mit dem es ursprünglich in der Wortbedeutung identisch war, aber da wird nur noch schalkhaft hingedeutet auf dieses Nützlichfinden. Der fromme Knecht war der, der einem möglichst viel nützt. Die römischen Priester haben auch gefunden, daß ihnen manche mehr, manche weniger nützen, und die Nützlichsten haben sie fromm genannt. Und so ist das Wort fromm auf einem merkwürdigen Wege gekommen, gerade durch die Einwanderung des Christentums von Rom aus. An Demut, an Frommsein und manchem anderen können Sie schon etwas studieren von den besonderen Impulsen, durch die das Christentum von Süden aus nach Norden getragen worden ist.

Man muß schon auf das Seelische, das heißt, auf das innere Erleben eingehen, wenn man die Sprache verstehen will. Es ist durchaus das im Bilden der Worte vorhanden, was ich auf der einen Seite charakterisierte als das konsonantische Element, wenn man das nachbildet, was äußerer Vorgang ist, und auf der anderen Seite das Empfindende, das interjektive Element, wenn man seine Empfindungen in Anlehnung an das Äußere zum Ausdruck bringt. Nehmen wir ein ausgesprochen konsonantisches Wesen in der Sprachempfindung, in einem vorgerückten Stadium der Sprachentwickelung. Nehmen Sie an, man empfindet diese Form, die ich hier aufzeichne. Wenn der ursprüngliche Mensch diese Form empfand, da empfand er sie zweifach. Da empfand er sie, indem er von unten nach oben schaute, als das Eingedrückte. Das wurde allmählich zu einem solchen Lautbestand, der uns in dem Worte Bogen vorliegt. Wenn er von oben nach unten auf diese Form schaute — wie es äußerlich zum Beispiel besonders ausgedrückt werden kann dadurch, daß ich möglichst das aufbiege (es wird gezeichnet), da kommt das zustande, was ich von oben nach unten anschaue: dann wird es ein Bausch. Von unten nach oben ist es ein Bogen, von oben nach unten ein Bausch; in Bogen und in Bausch liegt noch etwas von der Empfindung drinnen. Will man dann das ausdrücken, was beides umfaßt, was gewissermaßen sich nicht mehr an die Empfindung anlehnt, sondern nach außen läuft, um den ganzen Vorgang auszudrükken, dann sagt man: in Bausch und Bogen. In Bausch und Bogen, imaginativ ausgedrückt, wäre das (Hinweis auf die Zeichnung) von oben und von unten gesehen. — Das kann man dann auch auf moralische Verhältnisse anwenden, wenn man mit jemandem ein Geschäft abschließt, so daß das, was sich ergibt, sowohl von innen wie von außen sich anschauen läßt: von innen angesehen ergibt es Gewinn, von außen angesehen das Gegenteil, Verlust. Wenn man mit jemandem ein Geschäft auf Gewinn und Verlust abschließt, so könnte man sagen: man schließt es in Bausch und Bogen ab, man nimmt nicht Rücksicht auf das, was unterschieden wird in der einzelnen Bezeichnung.

Ich wollte Ihnen damit klarmachen, daß man durch das Verfolgen der Entwickelung der Lautbestände, aber auch der Wortbestände, Bilder hat von dem Entwickeln des volksseelischen Elementes, und Sie können, wenn Sie dieses Vorrücken von dem Konkreten des Lautlebens zu dem Abstrakten des Vorstellungslebens als Richtlinien verfolgen, vieles dann selbst finden. Sie brauchen nur ein gewöhnliches Lexikon aufzuschlagen oder Wörter aufzunehmen aus der Umgangssprache und sie mit solchen Richtlinien zu verfolgen. Für unsere Lehrerschaft sage ich noch insbesondere, daß es außerordentlich anregend ist, mitten im Erzählen einmal hinzuweisen auf solche sprachgeschichtliche Momente, weil sie manchmal tief aufklärend sein können und außerdem das Denken außerordentlich anregen. Aber man muß immer gefaßt sein, daß man natürlich da auf Holzwege abirren kann; daher muß man immer recht vorsichtig sein, denn die Worte machen ja mannigfaltige Metamorphosen durch, wie Sie jetzt gesehen haben. Also es kommt darauf an, daß man nicht gleich auf äußeren Ähnlichkeiten etwa Hypothesen aufstellt, sondern daß man ganz gewissenhaft vorgeht.

Daß man gewissenhaft vorgehen muß, das können Sie an einem Beispiel sehen, das ich Ihnen auch noch vorführen möchte. Es gab ein ursprüngliches, recht ehrliches deutsches Wort, das hieß Beiwacht — wenn sich die Leute zusammensetzten und miteinander wachten -, Beiwacht, Zusammenwacht. Es ist das eins von denjenigen Worten, die nicht wie manche andere von Frankreich nach Deutschland gewandert sind, sondern es ist unversehens einmal nach Frankreich gewandert, wie auch das Wort guerre, Krieg, die Wirren. Beiwacht ist in alten Zeiten einmal nach Frankreich gewandert und ist da zu bivouac geworden. Und es ist wieder zurückgewandert mit den zahlreichen Wanderungen der westlichen Wörter, die herübergekommen sind nach dem 12. Jahrhundert; es ist wieder herübergewandert und ist Biwak geworden. Dies Wort ist ein ursprünglich deutsches, das aber zuerst nach Frankreich gewandert ist und wieder zurückgekommen ist. In der Zwischenzeit war es wenig gebraucht. Solche Dinge finden also auch statt, daß Wörter auswandern, es ihnen dann zu schwül wird in der fremden Atmosphäre und sie wieder heimkehren. Also, alle möglichen Verhältnisse finden da statt.

Fourth Lecture

You have seen that in these considerations, it is first and foremost important to trace the linguistic-historical moments back to the spiritual. Indeed, it is impossible to understand the process of language formation or the current state of any linguistic construct without addressing the spiritual element. And today, in order to illustrate this with specific examples from linguistic history, I would like to present some of the insights that can be gained from observing linguistic phenomena in relation to the development of the folk-souls.

I would like to draw your attention to two related words: Zuber and Eimer. If you take these words, which are old German words, today, you will conclude from their use that an Eimer is a vessel in which something is carried and which has a single handle attached at the top; a tub is something that has two handles. This fact is evident today and is expressed in the two words: tub and bucket. If we examine the word bucket, we can go back over a thousand years: we find it in Old High German or in an even earlier stage and find the word einbar. Now remember that I showed you the sound connection bar. It is related to beran: to carry, and by contracting einbar, Eimer was created. So we have clearly expressed, so that it can be seen transparently in its old form, carrying with one handle; for bar is simply something to carry. Zuber means zwiebar in Old High German, something that is carried by two, i.e., a vessel with two handles. So we see how today's words were formed by contractions, which we still find separated in the old form, but which we can no longer distinguish in the word today.

We can observe similar things in other linguistic material. Let's consider a few characteristic examples. Take, for example, the word knife. The word can be traced back to the Old High German mezzisahs. Mezzi, with a preceding M, is nothing other than what is connected with ezzi, essen — ezzan, the old form for essen (to eat). But now sahs, sax could also be said in a different pronunciation. You only need to remember: when Christianity spread across southern Germany, the monks there still found the older worship of those three deities, one of which was the deity Saxnot; that is the god of war, Ziu. Saxnot is the compound for the living sword, and sahs is the same sound connection. So that in the word knife you have the compound word eating sword: the sword with which you eat.

The word eyelash is also interesting. It goes back to wintbra. Bra = the brow, and wint is the winding. You can see it clearly here: the winding brow. In the compound word eyelash, we no longer distinguish this.

Now for another characteristic word for such contractions, where there are still perceived connections. You are familiar with the not so uncommon German word Schulze. If we go back to Old High German, we find the word sculdheizo. This was the man in the village who told you what your debt was, who made you aware when you had done something wrong. The man who had to decide, to heißen, what your debt was, the sculdheizo, Schuld-heißer, became the Schulze. I want to give these examples so that you can follow me in how language develops.

Something else can also be observed in this direction. Let us take something that still occurs easily in dialect. In Vienna, for example, some dialectal features have been preserved more purely than in northern Germany, where abstraction took hold early on. And this goes back to the primitive culture that dates back to the 10th century. Nordic culture did not adopt what has been preserved in southern German regions in terms of linguistic genius, which can still be seen in many ways in the old forms of language that appear in it. For example, there is a vivid word in Vienna called Hallodri. This is someone who likes to get up to mischief, who causes a lot of trouble, who may indulge in debauchery, even if it is not particularly serious. The Hallo refers to what he does; the final syllable ri refers to his behavior. This ri is a dialectal remnant of the Old High German ari, which became the Middle High German aere and has been greatly weakened in New High German to the final syllable er. Take, for example, an Old High German word: wahtari. There you also have this syllable, you have what is perceived in the Austrian dialect in the word Hallodri. This appearance in life with something lies in the final syllable ari, and wath is waking. The one who does this with the office of watching is the wathari; in Middle High German it becomes wahtaere, i.e. still with the full final syllable; in New High German it is Wächter (guard). It has become the syllable er, which has little of the feeling that one felt with ari: the handling of the matter. In all words that have this final syllable er, one should therefore feel, when one immerses oneself again in what has been preserved from ancient times, this handling of a thing. The one who handles things in the garden is the gartenaere, our modern-day gardener. You can see from this how language strives to gradually transform the sonorous, I would say the musical, into the abstract, in which the full content of the sound is no longer felt and, in particular, is no longer connected with the full content of the mental image or sensation.

The following is an interesting example: Today you know the syllable ur in Ursache (cause), Urwald (primeval forest), Urgroßvater (great-grandfather), and so on. If we go back about two millennia in our language development, we find the same syllable in Gothic as uz; if we go back to Old High German, around the year 1000, we find the same syllable as ar, ir, ur. Seven hundred years ago, it was still ur, and it is still today. So this syllable changed relatively early on. It has only weakened in verbs. For example, we say Kunde (customer) to express what makes something known. But if we want to refer to the first customer, the one from whom the other customer originates, we say Urkunde (document). Now, the ur is weakened to er for verbs, so that when we form the verb kennen (to know), we do not say, as would also be possible, urkennen, but erkennen; but the er has exactly the same meaning as the ur in Urkunde. If I enable someone to do something, then I allow them to do something; if I make this into a noun in a specific case, it becomes the word Urlaub (vacation), which I give them through my permission. Now there is another formation that is extremely interesting and echoes all of this. You know the word: to cultivate a field. This urbar is also related to beran, to bear. Urbar is the original, the first bearing of a field. You have, I would say, a semantic analogy in the word ertrag, which still exists today. When you say today: yield of the field — this is the same word as cultivating the field = the first yield of the field. And originally, urbar was also used when one wanted to say: to work the field so that it can bear something, for example, its interest, its tax.

The study of the prefixes and suffixes that appear in our words is extremely interesting. For example, we have the prefix ge in numerous words. It goes back to a Gothic ga. In this Gothic ga, the sense of pulling together was still very much felt; ga has the emotional meaning of pulling together, pushing together. This then became gi in Old High German and ge in New High German. If you then have the word salle, selle, which was formed in other ways, and you put the ge in front of it, Geselle, you have a person who shares the same room with another or sleeps in the same hall with him: that is then the Geselle. Genosse is someone who enjoys the same things as another person.

I would like to draw your attention to the characteristic feature that runs through these examples. One must approach the word differently if one still has an immediate feeling for what it means when one hears it, than if one no longer has this feeling. If you simply say “journeyman” because you have remembered since childhood that journeyman means this or that, it is different from when you still have the feeling of the hall and, in the case of journeyman, precisely this connection between the hall and two or more people. This emotional element is discarded. Only then is it possible to abstract.

Now, for example, many of our words have the suffix lich: göttlich (divine), freundlich (friendly). If you look up this lich two thousand years ago, you will find it in Gothic as leiks. But this Gothic leiks, which then becomes Old High German lich, is closely related to leich and also to leib; and I have already told you that leich-leib expresses the form that remains behind when a person dies. Leichnam is actually something of a tautological formation, like the kind of formation a child might make when it first has two words that sound exactly the same and puts them together: wau-wan, muh-muh, whereby the meaning is established through repetition. However, dissimilar sounds can also be put together; and you have such a combination, for example, in the word Leichnam. Leich is actually the form that remains when the soul has left the human being; nam, however, leads back to ham, and ham is the word that has been preserved in Hemd (shirt) and means shell; so that Leichnam is the form-shell, the form-shirt that we have cast off after death. So there are two similar things: form – and the slightly shifted covering, combined like wauwau. Now, however, our suffix lich is formed from this leiks, leich. So you see: if you form the word divine, it must refer to a form; for lich is leiks: form. I am referring to a form that expresses the divine; thus, god-formed would be divine. This is particularly interesting to observe, for example, when we consider the Old High German word anagilih. Here we still have the Gothic ana, and ana is: nearly, almost; gilih is the form. So what is similar is that which almost has the form. When it becomes a New High German word, it becomes similar.

In this example in particular, you can study something that is not purely linguistic, but rather, I would say, linguistic-psychological, because it can show you how emotional values live in words, but how these emotional values gradually detach themselves in human perception, and how that which the mental image still associates with the sounds becomes a completely abstract element. I have shown you the prefix ge, Gothic ga. So imagine that one still feels this interaction in ga, which now becomes ge, and applies it to the form, to the leich; then, in terms of the history of feeling, I would say: a harmonious form. It lives in it without being expressed. Geleich, equal, would therefore be: harmonious forms, interacting forms, geleich = equal.

Consider a word that reveals many secrets – we will only look at one aspect of it today – consider our word Ungetüm (monster). This ä is only the umlaut for an original u: Ungetum; but the tum that we detach there goes back to an Old High German tuorm, and this tuom is related to the word tun: to bring about, to make, to bring into a relationship. In all words where this tum has become a suffix, one can actually still sense that there is something of a cooperative relationship contained therein: Königtum (kingship), Herzogtum (duchy), Ungetüm (monster). A monster is something in which no proper cooperative tum arises: the #2 negates the cooperation; the getum would be the cooperation itself.

As you know, we have numerous words with the suffix ig: feurig, gelehrig, and so on. This goes back to an Old High German ac or ic, to a Middle High German ag, ig, and this is actually the rendering of what is called eigenschaftswörtlich eigen, it is eig. So where the suffix ig occurs, it indicates an eigen. Feurig = feuereigen, to which fire is eigen. I have told you that we can observe how, through such contractions and the resulting transformations of the sound inventory, the process of abstraction takes place that the linguistic genius undergoes.

Language actually consists only of differentiated, complicated images in the consonantal sounds, in which external processes are reproduced, and of interjections occurring within them, sounds of feeling in the vowel formations. Now the language-forming process continues. Man, so to speak, withdraws from this shared experience, from this emotional shared experience of the sound. What are they doing when they lift themselves out? They are still speaking, but as they speak, speech is pushed down into a much more subconscious region than it was before, where the mental image and feeling were still connected with sound formation. Speech itself is thrown down into a subconscious region. Meanwhile, consciousness seeks to intercept the thought. Observe this as a process of the soul. By making the sound connection unconscious, one rises with consciousness to the realm of mental image and feeling, which is no longer felt solely in sound and sound connection. One seeks to grasp something that the sound still points to, but which is no longer as intimately connected with the sound as it was before. Such a process can still be observed even when the original I would like to say, peeling away from the sound contexts is already over, and one must now do the same thing that one used to do with sound contexts with word contexts, because words have already been created in which one no longer fully feels the sound context, in which one already has the sound context with the conceptual context more in one's memory. At a higher level, one carries out the same process with words that one used to do with sounds and syllables.

Suppose you wanted to express the human beings of a certain region, but you did not want to proceed to complete abstraction, so that you would say, for example: The human beings of Württemberg. You would not want to say that yet, it would still be too abstract. You would not yet have risen to such strong abstractions as: The people of Württemberg. If you wanted to capture the same thing that you later express with “the people of Württemberg” in even more concrete terms, you would say: “the citizens and farmers of Württemberg.” You say this to refer to those who are neither farmers nor citizens, or both, but who in a sense hover between the two. To capture what hovers in between, both words are needed. This becomes particularly interesting and clear when the two words used to express a concept are approached from two sides, so to speak, and when the two words are further apart, for example, when one says: country and people. When you say this, what you want to say lies in between, and you approach it. Or: wind and weather. When you say this, you mean something that you cannot express with one word, something that is neither wind nor weather, but lies in between, which you capture by using wind and weather.

Now it is interesting that in the course of language development, such combinations are expressed in such a way that they somehow alliterate, assonate, or the like. From this you can see that the perception of sound, the perception of tone, still plays a role in these things. And anyone who has a lively sense of language can still continue to do such things today, can use similar-sounding words to capture intermediate mental images for which there is no immediate word. Suppose, for example, I want to express something about a person, such as their behavior, as it is habitual to them, as it is essentially their own. If I take offense at using a word that presents humans as passive beings — because I do not want to present them in their essential expression and revelation as passive beings, but also do not want to present them as merely active, but rather want to derive their activity from their essence — then I cannot say: The soul of a human being lives — that would be too passive for me; nor can I say: The soul of a human being weaves — that would be too active for me. I need something in between, and so today I still say: The soul lives and weaves. Numerous examples of this can be found in the genius of language. Imagine, for example, that one wants to express something that is neither song nor sound; one says song and sound. Or if you want to express that a medieval poet produces sound and text, you often wanted to express that poets produced sound and text, but you couldn't say: “They go around and sing” – instead, you said: “They go around and sing and speak.” What they actually did was a concept for which there was no word. You see, such things are, I would say, the latecomers for what used to happen with sound connections that are no longer transparent today. With words such as “sang” and “klang,” ‘sing’ and “say,” we still form contractions that used to be made with such sound inventories, which still had the connection between the sound inventory and the element of mental image or sensation.

Take, for example, the following to illustrate something very characteristic in this regard: when the ancient Germans came together and held court, they called such a day tagading. What they did was a thing. Today we still have the expression “to turn a thing.” A thing is what happened when the ancient Germans were together. It was called tagading. Now take the prefix ver; it always indicates that something is entering into development. So when what happened at the Tageding entered into development, one could say: it was vertagedingt. And this word gradually became our verteidigen; with a slight change in meaning, it became our verteidigen. And so you see how, even in the sound structure of vertagedingen, the same thing takes place that later takes place in the word structure.

This brings us gradually to the point where the world of ideas strays even further from the mere world of sounds. Take, for example, something like the Old High German alawari. That would have the meaning of: completely true. From this, our word albern (silly) has developed. Just imagine the depths of the national soul you are looking into when you see that something that originally had the meaning of completely true becomes silly, just as we perceive the word albern today. The use of the word alawari must be understood I would say, tribes who find the appearance of a person in the capacity of the completely true to be something contemptible, who devote themselves to the belief that the clever person is not alawar: . This conveys the feeling that those who are completely true are not clever, which was originally applied to a completely different feeling; and so the meaning of completely true shifts to silly.

When we study the change in meaning, we can look deeply into the language-forming genius in connection with the soul. Take, for example, our word mercury: this is the mobile metal. This Queck is the very same word as, for example, in Quecke, which also means mobility, or the same word that is in erquicken. This phonetic connection: queck and quick — with a slight shift in sound: keck — originally meant “to be mobile.” So if I had said of one of you 500 years ago, “He is a keck person,” I would have meant, “He is a mobile person who does not lie on his lazy skin, but is industrious, who gets things done.” Through a shift in meaning, this has become the modern word keck. At the same time, the spiritualization is the path to a very significant change in meaning. So we find a word that originally expressed boldness in battle. We only need to go back about five hundred years, and the word kühn in battle means cheeky. A cheeky person in the sense of earlier times would mean: a bold person, a person who is not afraid to act appropriately in battle. Here you have the change in meaning. These changes in meaning allow us to look deeply into the development of spiritual life. Take the Old High German diomuoti. Deo, dio always means servant, muoti, which is related to our courage, but used to have a different meaning, can only be reproduced today if we say: attitude, the way of being disposed towards the outside world or towards other people. So we can say: diomuoti had the meaning of the right servant's attitude, the attitude that a servant should have towards his master. Then Christianity arrived. The monks wanted to tell people what they should have as their attitude towards God and spiritual beings. They could only express what they wanted to tell them by linking it to a feeling that people already had for this servant's attitude. So this diomuoti gradually became humility. The humility of religion is a descendant of the servile attitude of ancient Germanic times. This is how the change in meaning came about.