Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner

GA 300a

26 September 1919, Stuttgart

Third Meeting

[The meeting began with a discussion of some children Dr. Steiner had observed that morning.]

Dr. Steiner: E. E. must be morally raised. He is a Bolshevik.

A teacher who was substituting in the first grade poses a question.

Dr. Steiner: You should develop reading from pictorial writing. You should develop the forms from the artistic activity.

A teacher suggests beginning the morning with the Lord’s Prayer.

Dr. Steiner: It would be nice to begin instruction with the Lord’s Prayer and then go on to the verses I will give you. For the four lower grades I would ask that you say the verse in the following way:

The Sun with loving light

Makes bright for me each day;

The soul with spirit power

Gives strength unto my limbs;

In sunlight shining clear

I reverence, O God,

The strength of humankind,

That thou so graciously

Hast planted in my soul,

That I with all my might

May love to work and learn.From Thee come light and strength,

To Thee rise love and thanks.

The children must feel that as I have spoken it. First they should learn the words, but then you will have to gradually make the difference between the inner and outer clear to them.

The Sun with loving light

Makes bright for me each day;

The soul with spirit power

Gives strength unto my limbs;

The first part, that the Sun makes each day bright, we observe, and the other part, that it affects the limbs, we feel in the soul. What lies in this portion is the spirit-soul and the physical body.

In sunlight shining clear

I reverence, O God,

The strength of humankind,

That thou so graciously

Hast planted in my soul,

That I with all my might

May love to work and learn.

Here we give honor to both. We then turn to one and then the other.

From Thee come light and strength (the Sun),

To Thee rise love and thanks (from within).

This is how I think the children should feel it, namely, the divine in light and in the soul.

You need to attempt to speak it with the children in chorus, with the feeling of the way I recited it. At first, the children will learn only the words, so that they have the words, the tempo, and the rhythm. Later, you can begin to explain it with something like, “Now we want to see what this actually means.” Thus, first they must learn it, then you explain it. Don’t explain it first, and also, do not put so much emphasis upon the children learning it from memory. They will eventually learn it through repetition. They will be able to read it directly from your lips. Even though it may not go well for a long time, four weeks or more, it will go better later. The older children can write it down, but you must allow the younger ones to learn it slowly. Don’t demand that they learn it by heart! It would be nice if they write it down, since then they will have it in their own handwriting. I will give you the verse for the four higher classes tomorrow.

[The verse for the four higher grades was:]

I look into the world;

In which the Sun shines,

In which the stars sparkle,

In which the stones lie,

The living plants are growing,

The animals are feeling,

In which the soul of man

Gives dwelling for the spirit;

I look into the soul

Which lives within myself.

God’s spirit weaves in light

Of Sun and human soul,

In world of space, without,

In depths of soul, within.

God’s spirit, ‘tis to Thee

I turn myself in prayer,

That strength and blessing grow

In me, to learn and work.

[The texts of the verses are exactly as Dr. Steiner dictated them according to the handwritten notes. It is unclear whether he said, “loving light” (liebes Licht) or “light of love” (Liebeslicht).]

[Lesson plan for the independent anthroposophical religious instruction for children:]

Dr. Steiner: We should give this instruction in two stages. If you want to go into anthroposophical instruction with a religious goal, then you must certainly take the concept of religion much more seriously than usual. Generally, all kinds of worldviews that do not belong there mix into religion and the concept of religion. Thus, the religious tradition brings things from one age over into another, and we do not want to continue to develop that. It retains views from an older perspective alongside more developed views of the world. These things appeared in a grotesque form during the age of Galileo and Giordano Bruno. Modern apologies justify such things—something quite humorous. The Catholic Church gets around it by saying that at that time the Copernican view of the world was not recognized, the Church itself forbade it. Thus, Galileo could not have supported that world perspective. I do not wish to go into that now, but I mention it only to show you that we really must take religion seriously when we address it anthroposophically.

It is true that anthroposophy is a worldview, and we certainly do not want to bring that into our school. On the other hand, we must certainly develop the religious feeling that worldview can give to the human soul when the parents expressly ask us to give it to the children. Particularly when we begin with anthroposophy, we dare not develop anything inappropriate, certainly not develop anything too early. We will, therefore, have two stages. First, we will take all the children in the lower four grades, and then those in the upper four grades.

In the lower four grades, we will attempt to discuss the things and processes in the human environment, so that a feeling arises in the children that spirit lives in nature. We can consider such things as my previous examples. We can, for instance, give the children the idea of the soul. Of course, the children first need to learn to understand the idea of life in general. You can teach the children about life if you direct their attention to the fact that people are first small and then they grow, become old, get white hair, wrinkles, and so forth. Thus, you tell them about the seriousness of the course of human life and acquaint them with the seriousness of the fact of death, something the children already know.

Therefore, you need to discuss what occurs in the human soul during the changes between sleeping and waking. You can certainly go into such things with even the youngest children in the first group. Discuss how waking and sleeping look, how the soul rests, how the human being rests during sleep, and so forth. Then, tell the children how the soul permeates the body when it awakens and indicate to them that there is a will that causes their limbs to move. Make them aware that the body provides the soul with senses through which they can see and hear and so forth. You can give them such things as proof that the spiritual is active in the physical. Those are things you can discuss with the children.

You must completely avoid any kind of superficial teaching. Thus, in anthroposophical religious instruction we can certainly not use the kind of teaching that asks questions such as, Why do we find cork on a tree? with the resulting reply, So that we can make champagne corks. God created cork in order to cork bottles. This sort of idea, that something exists in nature simply because human intent exists, is poison. That is certainly something we may not develop. Therefore, don’t bring any of these silly causal ideas into nature.

To the same extent, we may not use any of the ideas people so love to use to prove that spirit exists because something unknown exists. People always say, That is something we cannot know, and, therefore, that is a revelation of the spirit. Instead of gaining a feeling that we can know of the spirit and that the spirit reveals itself in matter, these ideas direct people toward thinking that when we cannot explain something, that proves the existence of the divine. Thus, you will need to strictly avoid superficial teaching and the idea of wonders, that is, that wonders prove divine activity.

In contrast, it is important that we develop imaginative pictures through which we can show the supersensible through nature. For example, I have often mentioned that we should speak to the children about the butterfly’s cocoon and how the butterfly comes out of the cocoon. I have said that we can explain the concept of the immortal soul to the children by saying that, although human beings die, their souls go from them like an invisible butterfly emerging from the cocoon. Such a picture is, however, only effective when you believe it yourself, that is, when you believe the picture of the butterfly creeping out of the cocoon is a symbol for immortality planted into nature by divine powers. You need to believe that yourselves, otherwise the children will not believe it.

You need to arouse the children’s interest in such things. They will be particularly effective for the children where you can show how a being can live in many forms, how an original form can take on many individual forms. In religious instruction, it is important that you pay attention to the feeling and not the worldview. For example, you can take a poem about the metamorphosis of plants and animals and use it religiously. However, you must use the feelings that go from line to line. You can consider nature that way until the end of the fourth grade. There, you must always work toward the picture that human beings with all our thinking and doing live within the cosmos. You must also give the children the picture that God lives in what lives in us. Time and again you should come back to such pictures, how the divine lives in a tree leaf, in the Sun, in clouds, and in rivers. You should also show how God lives in the bloodstream, in the heart, in what we feel and what we think. Thus, you should develop a picture of the human being filled with the divine.

During these years, you should also emphasize the picture that human beings, because they are an image of God and a revelation of God, should be good. Human beings who are not good hurt God. From a religious perspective, human beings do not exist in the world for their own sake, but as revelations of the divine. You can express that by saying that people do not exist just for their own sake, but “to glorify God.” Here, “to glorify” means “to reveal.” Thus, in reality, it is not “glory to God in the highest,” but “reveal the gods in the highest.” Thus, we can understand the idea that people exist to glorify God as meaning that people exist in order to express the divine through their deeds and feelings. If someone does something bad, something impious and unkind, then that person does something that belittles God and distorts God into something ugly.

You should always bring in these ideas. At this age you should use the thought that God lives in the human being. In the lower grades, I would certainly abstain from teaching any Christology, but just awaken a feeling for God the Father out of nature and natural occurrences. I would try to connect all our discussions about Old Testament themes, the Psalms, the Song of Songs, and so forth, to that feeling, at least insofar as they are useful, and they are if you treat them properly. That is the first stage of religious instruction.

In the second stage, that is, the four upper grades, we need to discuss the concepts of fate and human destiny with the children. Thus, we need to give the children a picture of destiny so that they truly feel that human beings have a destiny. It is important to teach the child the difference between a simple chance occurrence and destiny. Thus, you will need to go through the concept of destiny with the children. You cannot use definitions to explain when something destined occurs or when something occurs only by chance. You can, however, perhaps explain it through examples. What I mean is that when something happens to me, if I feel that the event is in some way something I sought, then that is destiny. If I do not have the feeling that it was something I sought, but have a particularly strong feeling that it overcame me, surprised me, and that I can learn a great deal for the future from it, then that is a chance event. You need to gradually teach the children about something they can experience only through feeling, namely the difference between finished karma and arising or developing karma. You need to gradually teach children about the questions of fate in the sense of karmic questions.

You can find more about the differences in feeling in my book Theosophy. For the newest edition, I rewrote the chapter, “Reincarnation and Karma,” where I discuss this question. There, I tried to show how you can feel the difference. You can certainly make it clear to the children that there are actually two kinds of occurrences. In the one case, you feel that you sought it. For example, when you meet someone, you usually feel that you sought that person. In the other case, when you are involved in a natural event, you have the feeling you can learn something from it for the future. If something happens to you because of some other person, that is usually a case of fulfilled karma. Even such things as the fact that we find ourselves together in this faculty at the Waldorf School are fulfilled karma. We find ourselves here because we sought each other. We cannot comprehend that through definitions, only through feeling. You will need to speak with the children about all kinds of fates, perhaps in stories where the question of fate plays a role. You can even repeat many of the fairy tales in which questions of fate play a role. You can also find historical examples where you can show how an individual’s fate was fulfilled. You should discuss the question of fate, therefore, to indicate the seriousness of life from that perspective.

I also want you to understand what is really religious in an anthroposophical sense. In the sense of anthroposophy, what is religious is connected with feeling, with those feelings for the world, for the spirit, and for life that our perspective of the world can give us. The worldview itself is something for the head, but religion always arises out of the entire human being. For that reason, religion connected with a specific church is not actually religious. It is important that the entire human being, particularly the feeling and will, lives in religion. That part of religion that includes a worldview is really only there to exemplify or support or deepen the feeling and strengthen the will. What should flow from religion is what enables the human being to grow beyond what past events and earthly things can give to deepen feeling and strengthen will.

Following the questions of destiny, you will need to discuss the differences between what we inherit from our parents and what we bring into our lives from previous earthly lives. In this second stage of religious instruction, we bring in previous earthly lives and everything else that can help provide a reasoned or feeling comprehension that people live repeated earthly lives.

You should also certainly include the fact that human beings raise themselves to the divine in three stages. Thus, after you have given the children an idea of destiny, you then slowly teach them about heredity and repeated earthly lives through stories. You can then proceed to the three stages of the divine.

The first of these stages is that of the angels, something available for each individual personally. You can explain that every individual human being is led from life to life by his or her own personal genius. Thus, this personal divinity that leads human beings is the first thing to discuss.

In the second step, you attempt to explain that there are higher gods, the archangels. (Here you gradually come into something you can observe in history and geography.) These archangels exist to guide whole groups of human beings, that is, the various peoples and such. You must teach this clearly so that the children can learn to differentiate between the god spoken of by Protestantism, for instance, who is actually only an angel, and an archangel, who is higher than anything that ever arises in the Protestant religious teachings.

In the third stage, you teach the children about the concept of a time spirit, a divine being who rules over periods of time. Here, you will connect religion with history.

Only when you have taught the children all that can you go on, at about the twelfth grade, to—well, we can’t do that yet, we will just do two stages. The children can certainly hear things they will understand only later. After you have taught the children about these three stages, you can go on to the actual Christology by dividing cosmic evolution into two parts: the pre-Christian, which was really a preparation, and the Christian, which is the fulfillment. Here, the concept that the divine is revealed through Christ, “in the fullness of time,” must play a major role.

Only then will we go on to the Gospels. Until then, to the extent that we need stories to explain the concepts of angel, archangel, and time spirit, we will use the Old Testament. For example, we can use the Old Testament story of what appeared before Moses to explain to the children the appearance of a new time spirit, in contrast to the previous one before the revelation to Moses. We can then also explain that a new time spirit entered during the sixth century B.C. Thus, we first use the Old Testament. When we then go on to Christology, having presented it as being preceded by a long period of preparation, we can go on to the Gospels. We can attempt to present the individual parts and show that the four-foldedness of the Gospels is something natural by saying that just as a tree needs to be photographed from four sides for everything to be properly seen, in the same way the four Gospels present four points of view. You take the Gospel of Matthew and then Mark, Luke, and John and emphasize them such that the children will always feel that. Always place the main emphasis upon the differences in feeling.

Thus, we now have the teaching content of the second stage. The general tenor of the first stage is to bring to developing human beings everything that the wisdom of the divine in nature can provide. In the second stage, the human being no longer recognizes the divine through wisdom, but through the effects of love. That is the tenor, the leitmotif in both stages.

A teacher: Should we have the children learn verses?

Dr. Steiner: Yes, at first primarily from the Old Testament and then later from the New Testament. The verses contained in prayer books are often trivial, therefore, you should use verses from the Bible and also those verses we have in anthroposophy. In anthroposophy, we have many verses you can use well in this anthroposophical religious instruction.

A teacher: Should we teach the Ten Commandments?

Dr. Steiner: The Ten Commandments are, of course, in the Old Testament, but you should make their seriousness clear. I have always emphasized that the Ten Commandments state that we should not speak the name of God in vain. This is something that nearly every preacher overdoes since they continually speak vainly of Christ. Of course, this is something we must deepen in the feeling. We should not give religious instruction as a confession of faith, but as a deepening of feeling. The Apostles’ Creed as such is not important, only what we feel in the Creed. It is not our belief in God the Father, in God the Son, and in God the Holy Spirit, but what we feel in relationship to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. What is important is that in the depths of our soul, we feel that it is an illness not to know God, that it is a misfortune not to know Christ and that not to know the Holy Spirit is a limitation of the human soul.

A teacher: Should we teach the children about historical things, for instance, the path of the Zarathustra being up to the revelation of Christianity, or the story of the two Jesus children?

Dr. Steiner: You should close the religious instruction by teaching the children about these connections but, of course, very carefully. The first stage is clearly more nature religion, the second, more historical religion.

A teacher: Then we should certainly avoid teaching about functionality in natural history? Schmeil’s guidelines for botany and zoology are teleological.

Dr. Steiner: With regard to books, I would ask that you consider them only as a source of factual information. You can assume that we should avoid the methods described in them, and also the viewpoints. We really must do everything new. We should completely avoid the books that are filled with the horrible attitude we can characterize with statements such as “God created cork in order to cork champagne bottles.” For us, such books exist only to inform us of facts. The same is true for history. All the judgments made in them are no less garbage, and in natural history that is certainly true.

In my opinion it would not be so bad if we used Brehm, for example, if such things are to be up-to-date. Brehm avoids such trivial things, though he is a little narrow-minded. It would be a good idea to copy out such things and use stories as a basis. Perhaps, that would be the best thing to do. The old edition of Brehm is pretty boring. We cannot use the new edition written recently by someone else.

In general, you can assume all school books written after 1885 are worthless. Since that time, all pedagogy has regressed in the most terrible way and simply landed in clichés.

A teacher: How should we proceed with human natural history? How should we start that in the fourth grade?

Dr. Steiner: Concerning human beings you will find nearly everything somewhere in my lecture cycles. You will find nearly everything there somewhere. You also have what I presented in the seminar course. You need only modify it for school. The main thing is that you hold to the facts, also the psychological and spiritual facts. You can first take up the human being by presenting the formation of the skeleton. There, you can certainly be confident. Then go on to the muscles and the glands. You can teach the children about will by presenting the muscles and about thinking by presenting the nerves. Hold to what you know from anthroposophy. You must not allow yourselves to be led astray through the mechanical presentation of modern textbooks. You really don’t need anything at the forefront of science for the fourth grade, so perhaps it is better to take an older description and work with that. As I said, all of the things since the 1880s have become really bad, but you will find starting points everywhere in my lectures.

A teacher: I put together a table of geological formations based on what you said yesterday.

Dr. Steiner: Of course, you should never pedantically draw parallels. When you go on to the primeval forms, to the original mountains, you have the polar period. The Paleozoic corresponds to the Hyperborean, but you may not take the individual animal forms pedantically. Then you have the Mesozoic, which generally corresponds to Lemuria. And then the first and second levels of mammals, or the Cenozoic, that is, the Atlantean age. The Atlantean period was no more than about nine thousand years ago. You can draw parallels from these five periods, the primitive, the Paleozoic, the Mesozoic, the Cenozoic, and the Anthropozoic.

A teacher: You once said that normally the branching off of fish and birds is not properly presented, for example, by Haeckel.

Dr. Steiner: The branching off of fish is usually put back into the Devonian period.

A teacher: How did human beings look at that time?

Dr. Steiner: In very primitive times, human beings consisted almost entirely of etheric substance. They lived among other things but had as yet no density. The human being became more dense during the Hyperborean period. Only those animal forms that had precipitated out, lived. Human beings lived also with no less strength. They had, in fact, a tremendous strength. But they had no substance that could remain, so there are no human remains. They lived during all those periods but only gained an external density during the Cenozoic period. If you recall how I describe the Lemurian period, it was almost an etheric landscape. Everything was there, but there are no geological remains. You will want to take into account that the human being existed through all five periods. The human being was everywhere. Here in the first period (Dr. Steiner points to the table), “primitive form,” there is actually nothing else present except the human being. There are only minor remains. There the Eozoic Canadensa is actually more of a formation, something created as a form that is not a real animal. Here in the Hyperborean/Paleozoic period, animals begin to occur, but in forms that later no longer exist. Here in the Lemurian/Mesozoic period, the plant realm arises, and here in the Cenozoic period, Atlantis, the mineral realm arises, actually already in the last period, in these two earlier periods already (in the last two sub-races of the Lemurian period).

A teacher: Did human beings exist with their head, chest, and limb aspects at that time?

Dr. Steiner: The human being was similar to a centaur, an extremely animal-like lower body and a humanized head.

A teacher: I almost have the impression that it was a combination, a symbiosis, of three beings.

Dr. Steiner: So it is, also.

A teacher: How is it possible that there are the remains of plants in coal?

Dr. Steiner: Those are not plant remains. What appears to be the remains of plants actually arose because the wind encountered quite particular obstacles. Suppose, for instance, the wind was blowing and created something like plant forms that were preserved somewhat like the footsteps of animals (Hyperborean period). That is a kind of plant crystallization, a crystallization into plantlike forms.

A teacher: The trees didn’t exist?

Dr. Steiner: No, they existed as tree forms. The entire flora of the coal age was not physically present. Imagine a forest present only in its etheric form and that thus resists the wind in a particular way. Through that, stalactite-like forms emerge. What resulted is not the remains of plants, but forms that arise simply due to the circumstances brought about by elemental activity. Those are not genuine remains. You cannot say it was like it was in Atlantis. There, things remained and to an extent also at the end of the Lemurian period, but as to the carbon period, we cannot say that there are any plant remains. There were only the remains of animals, but primarily animals that we can compare with the form of our head.

A teacher: When did the human being then stand upright? I don’t see a firm point of time.

Dr. Steiner: It is not a good idea to cling to these pictures too closely, since some races stood upright earlier and others later. It is not possible to give a specific time. That is how things are in reality.

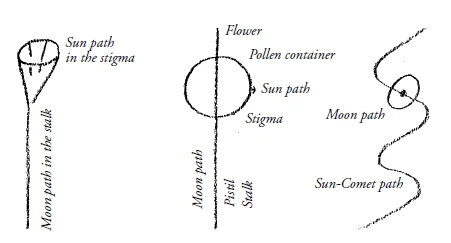

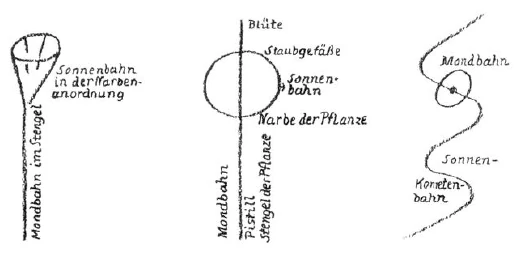

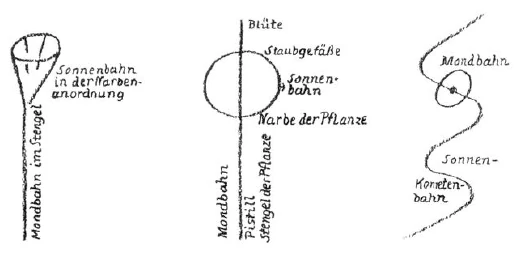

A teacher: If the pistil is related to the Moon and the stigma to the Sun, then how do they show the movement of the Sun and Moon?

Dr. Steiner: You must imagine it in the following way (Dr. Steiner draws). The stigma goes upward, that would be the path of the Sun, and the pistil moves around it, and there you have the path of the Moon. Here we have the picture of the Sun and Earth path as I drew it yesterday. The Moon moves around the Earth. That is in the pistil (Dr. Steiner demonstrates with the drawing). It appears that way because the path of the Moon goes around also, of course, but in relationship, not in a straight line. The path of the Sun is the stigma. This circle is a copy of the helix I drew yesterday. It is also a helix.

A teacher: You have told us that the temperaments have to do with predominance of the various bodies. In GA 129, you said that the physical body predominates over the etheric, the etheric over the astral, and the I over the astral. Is there a connection with the temperaments here? In GA 134, you mention a figure that gives the proper relationship of the bodies.

Dr. Steiner: That gives the relationship of the forces.

A teacher: Is there a further relationship to the temperaments?

Dr. Steiner: None other than what I presented in the seminar.

A teacher: You have said that melancholy arises due to a predominance of the physical body. Is that a predominance of the physical body over the etheric?

Dr. Steiner: No, it is a predominance over all the other bodies.

A question arises about parent evenings.

Dr. Steiner: We should have them, but it would be better if they were not too often, since otherwise the parents’ interest would lessen, and they would no longer come. We should arrange things so that the parents actually come. If we have such meetings too often, they would see them as burdensome. Particularly in regard to school activities, we should not do anything we cannot complete. We should undertake only those things that can really happen. I think it would be good to have three parent days per year. I would also suggest that we do this festively, that we print cards and send them to all of the parents.

Perhaps we could arrange it so that the first such meeting is at the beginning of the school year. It would be more a courtesy, so that we can again make contact with the parents. Then we could have a parent evening in the middle of the year and again one at the end. These latter two would be more important, whereas the first, more of a courtesy. We could have the children recite something, do some eurythmy, and so forth.

We can also have parent conferences. They would be good. You will probably find that the parents generally have little interest in them, except for the anthroposophical parents.

A teacher asks Dr. Steiner to say something about the popularization of spiritual science, particularly in connection with the afternoon courses for the workers [at the Goetheanum].

Dr. Steiner: Well, it is important to keep the proper attitude in connection with that popularization. In general, I am not in favor of popularizing by making things trivial. In my opinion, we should first use Theosophy as a basis and attempt to determine from case to case what a particular audience understands easily, or only with difficulty. You will see that the last edition of Theosophy has a number of hints about how you can use its contents for teaching. I would then go on to discussing some sections of How to Know Higher Worlds, but I would never intend to try to make people into clairvoyants. We should only inform them about the clairvoyant path so that they understand how it is possible to arrive at those truths. We should leave them with the feeling that it is possible with normal common sense to understand and know about how to comprehend those things. You can also treat The Spiritual Guidance of the Individual and Humanity in a popular way. There you have three books that you can use for a popular presentation. Generally, you will need to arrange things according to the audience.

Several children are discussed.

Dr. Steiner: The most important thing is that there is always contact, that the teacher and students together form a true whole. That has happened in nearly all of the classes in a very beautiful and positive way. I am quite happy about what has happened.

I can tell you that even though I may not be here, I will certainly think much about this school. It’s true, isn’t it, that we must all be permeated with the thoughts:

First, of the seriousness of our undertaking. What we are now doing is tremendously important.

Second, we need to comprehend our responsibility toward anthroposophy as well as the social movement.

And, third, something that we as anthroposophists must particularly observe, namely, our responsibility toward the gods.

Among the faculty, we must certainly carry within us the knowledge that we are not here for our own sakes, but to carry out the divine cosmic plan. We should always remember that when we do something, we are actually carrying out the intentions of the gods, that we are, in a certain sense, the means by which that streaming down from above will go out into the world. We dare not for one moment lose the feeling of the seriousness and dignity of our work.

You should feel that dignity, that seriousness, that responsibility. I will approach you with such thoughts. We will meet one another through such thoughts.

We should take that up as our feeling for today and, in that thought, part again for a time, but spiritually meet with one another to receive the strength for this truly great work.

Dritte Konferenz

Zunächst findet eine Besprechung über die einzelnen Kinder statt, die Rudolf Steiner sich am Vormittag angesehen hatte.

[WALTER JOHANNES STEIN, der vertretungsweise die 1. Klasse führte, stellt eine Frage.

RUDOLF STEINER: Man sollte das Lesen sehr stark aus dem malen den Schreiben herausarbeiten. Die Formen [müsste man] aus dem

Künstlerischen heraus ableiten.

Zum Folgenden sind nur Stichworte festgehalten: Muskeln - Wille; Nerven - Denken. Plan; Organisation; Lebenskunde; Wirtschaftswissenschaft; Erschaffung von Lehrmitteln.

Den E. E. [muss man] moralisch heben. [Er ist ein] «Bolschewist».

Es folgen Ausführungen über einen weiteren Schüler, die nicht festgehalten sind.

HERTNA KOEGEL schlägt vor, morgens mit dem Vaterunser zu beginnen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ich würde es sehr schön finden, mit dem Vaterunser den Unterricht zu beginnen. Dann gehen Sie über zu den Sprüchen, die ich Ihnen sagen werde. Für die [vier] unteren Klassen bitte ich, den Spruch in der folgenden Weise zu sagen:

Der Sonne liebes Licht,

Es hellet mir den Tag;

Der Seele Geistesmacht,

Sie gibt den Gliedern Kraft;

Im Sonnen-Lichtes-Glanz

Verehre ich, o Gott,ca Die Menschenkraft, die Du

in meine Seele mir

So gütig hast gepflanzt,

Dass ich kann arbeitsam

und lernbegierig sein.

Von Dir stammt Licht und Kraft,

Zu Dir ström’ Lieb’ und Dank.

Das müssten die Schüler so empfinden, wie ich es gesprochen habe. Man müsste ihnen auch klarmachen nach und nach - erst sollen sie die Worte aufnehmen - den Gegensatz des Äußeren und des Inneren.

Der Sonne liebes Licht,

Es hellet mir den Tag;

Der Seele Geistesmacht,

Sie gibt den Gliedern Kraft;

Das eine bemerkt man beobachtend, wie das Licht den Tag erhellt; das andere [ist] das Fühlen des Seelischen, wie es in die Glieder geht. Geistig-seclisch - physisch-körperlich: Das liegt in diesem Satz.

Im Sonnen-Lichtes-Glanz

Verehre ich, o Gott,

Die Menschenkraft, die Du

In meine Seele mir

So gütig hast gepflanzt,

Dass ich kann arbeitsam

Und lernbegierig sein.

Dies also verehrend zu denselben beiden. Dann noch einmal zu beiden sich wendend:

Von Dir stammt Licht und Kraft, (die Sonne)

Zu Dir ström’ Lieb’ und Dank. (vom Innern)

So, würde ich meinen, sollen die Kinder es empfinden: zu dem Göttlichen im Licht und in der Seele.

Sie müssen versuchen, mit dieser Empfindung, wie ich es vorgelesen habe, es mit den Kindern zusammen im Chor zu sprechen. Zuerst lernen es die Kinder rein wortgemäß, sodass sie Wort, Takt und Rhythmus haben. Erst später erklären Sie mal gelegentlich: Jetzt wollen wir mal sehen, was da drinnen ist. — Erst müssen sie es haben, dann erst erklären. Nicht zuerst erklären, auch nicht viel darauf geben, dass die Kinder es auswendig können. Im Gebrauch erst, nach und nach sollen sie es auswendig lernen. Sie sollen es förmlich von Ihren Lippen zunächst ablesen. Wenn es lange Zeit, vier Wochen meinetwegen, schlecht geht, umso besser wird es später gehen. Die Größeren können es schon aufschreiben; mit den Kleinsten muss man es nach und nach einlernen. Nicht befehlen, dass sie es auswendig lernen! Wenn Sie es ihnen aufschreiben, ist es ja schön; dann haben sie es in Ihrer Schrift.

Den Spruch für die vier höheren Klassen gebe ich Ihnen morgen noch.

Laut Stenogramm hat Steiner den Spruch schriftlich am 27.09.1919 dem Lehrerkollegium überreicht.

Der Spruch für die vier höheren Klassen lautet so:

Ich schaue in die Welt;

In der die Sonne leuchtet,

In der die Sterne funkeln;

In der die Steine lagern,

Die Pflanzen lebend wachsen,

Die Tiere fühlend leben,

In der der Mensch beseelt

Dem Geiste Wohnung gibt;

Ich schaue in die Seele,

Die mir im Innern lebet.

Der Gottesgeist, er webt

Im Sonn- und Seelenlicht,

Im Weltenraum, da draußen,

In Seelentiefen, drinnen.

Zu Dir, o Gottesgeist,

Will ich bittend mich wenden,

Dass Kraft und Segen mir

Zum Lernen und zur Arbeit

In meinem Innern wachse.

Es folgt ein längerer Exkurs Steiners zum Lehrplan des freien anthroposophischen Religionsunterrichts.

RUDOLF STEINER: Dieser Unterricht müsste in zwei Stufen erteilt werden. Wenn Sie überhaupt darauf eingehen wollen, anthroposophischen Unterricht mit religiösen Zielen zu betreiben, dann müssen Sie den Begriff des Religiösen eben viel ernster nehmen, als er gewöhnlich genommen wird. Gewöhnlich wird der Begriff der Religion dadurch entstellt, dass in die Religion allerlei nicht hineingehöriges Weltanschauliches hineingemischt wird. Dadurch wird gerade durch die religiöse Überlieferung von einem Zeitalter ins andere dasjenige hinübergetragen, was man nicht weiterbilden will. Es blieben alte Weltanschauungen neben den weitergebildeten Weltanschauungen gewahrt. Diese Dinge traten ja grotesk hervor in dem Zeitalter des Galilei und des Giordano Bruno. Wie heute noch in Apologien diese Dinge gerechtfertigt werden, das ist geradezu humorvoll. Die katholische Kirche redete sich aus, dass ja dazumal die kopernikanische Weltanschauung nicht anerkannt gewesen sei, die sie selber verboten hatte; daher durfte Galilei sie auch nicht vertreten. Darauf will ich jetzt nicht eingehen, sondern ich will es nur erwähnen, um Ihnen zu sagen, dass das Religiöse ernst genommen werden muss, sobald es sich um Anthroposophisches handelt.

Nicht wahr, das Anthroposophische ist eine Weltanschauung, und diese Weltanschauung, die wollen wir als solche durchaus nicht in unsere Schule hineintragen. Wir müssen aber jenes religiöse Gefühl, welches von dieser Weltanschauung der Menschenseele vermittelt wird, für die Kinder, deren Eltern es ausdrücklich verlangen, entwickeln. Wir dürfen aber gerade, wenn wir von der Anthroposophie ausgehen wollen, nichts Falsches entwickeln, nichts Verfrühtes vor allen Dingen entwickeln. Wir werden daher zwei Stufen unterscheiden. Wir nehmen also die Kinder zunächst zusammen, die wir in den vier Unterklassen haben, und dann die, die wir in den vier Oberklassen haben.

In den [vier] unteren Klassen versuchen wir mit den Kindern Dinge und Vorgänge der menschlichen Umwelt so zu besprechen, dass bei den Kindern die Empfindung entsteht, dass Geist in der Natur lebt. Da kommen also solche Dinge dann in Betracht, wie ich sie als Beispiele angeführt habe. Man will den Kindern zum Beispiel den Begriff der Seele beibringen. Da ist es notwendig, dass man erstens den Begriff des Lebens überhaupt den Kindern nahebringt. Den Begriff des Lebens bringt man den Kindern nahe, wenn man sie aufmerksam macht darauf, dass die Menschen zuerst klein sind, dann heranwachsen, alt werden, dass sie weiße Haare bekommen, Runzeln bekommen und so weiter. Also man weist auf den Ernst des Lebenslaufes beim Menschen hin und macht tatsächlich die Kinder mit dem Ernst des Todes bekannt, mit dem die Kinder ja doch bekannt werden.

Dann ist es durchaus nicht unnötig, nun Vergleiche anzustellen zwischen dem, was in der Menschenseele vorgeht beim Wechsel von Schlafen und Wachen. Auf solche Dinge kann man bei dem kleinsten Kinde auf der ersten Stufe durchaus eingehen. Wachen und Schlafen: Die Erscheinung besprechen, wie da die Seele ruhend ist, wie der Mensch unbeweglich ist im Schlafe und so weiter. Dann bespricht man mit dem Kinde, wie die Seele den Körper durchdringt, wenn er wacht, und macht es aufmerksam darauf, dass es einen Willen gibt, der in den Gliedern sich regt; macht es aufmerksam darauf, dass der Körper der Seele die Sinne gibt, durch die man sieht, hört und so weiter. Solche Dinge sind also [als] ein Beweis [zu geben] dafür, dass Geistiges im Physischen waltet. Das ist mit dem Kinde zu besprechen.

Vollständig vermieden muss werden irgendeine oberflächliche Zweckmäßigkeitslehre. Also der anthroposophische Religionsunterricht darf ja nicht nach dem Muster jener Zweckmäßigkeitslehre irgendwie orientiert sein, die da sagt: «Wozu findet man an dem Baume Kork?» «Damit man Champagnerpfropfen machen kann. Das hat der liebe Gott weise eingerichtet, damit man Kork zu Pfropfen hat.» Dieses, dass etwas da ist «wozu», das wie menschliche Absicht waltet [und] in der Natur sich auslebt, das ist Gift; das darf nicht entwickelt werden. Also ja nicht banale Zweckmäßigkeitsvorstellungen in die Natur hineintragen.

Ebenso wenig darf die Vorstellung gepflegt werden, die die Menschen so sehr lieben, dass das Unbekannte ein Beweis des Geistes ist. Nicht wahr, die Menschen sagen: Oh, das kann man nicht wissen, da offenbart sich der Geist! - Statt dass die Menschen die Empfindung bekommen: Man kann vom Geiste wissen, der Geist offenbart sich in der Materie -, werden die Menschen so sehr darauf hingelenkt, dass da, wo man sich etwas nicht erklären kann, ein Beweis ist für das Göttliche.

Diese zwei Dinge sind also streng zu vermeiden, oberflächliche Zweckmäßigkeitslehre und solche Wundervorstellungen, die also das Wunder geradezu suchen als einen Beweis des göttlichen Waltens.

Dagegen kommt es überall darauf an, dass wir uns Vorstellungen ausbilden, durch die wir aus der Natur auf das Übersinnliche hinweisen. Zum Beispiel habe ich ja oftmals das eine erwähnt: Wir sprechen mit den Kindern über die Schmetterlingspuppe, wie der Schmetterling aus der Puppe kommt, und machen ihnen daran den Begriff der unsterblichen Seele klar, indem wir sagen - nachdem wir früher über den Ernst des Todes gesprochen haben -: Ja, der Mensch stirbt, und dann geht aus ihm die Seele heraus wie ein unsichtbarer Schmetterling, so, wie der Schmetterling aus der Puppe geht. Aber wirksam ist eine solche Vorstellung nur, wenn Sie selber daran glauben, wenn Ihnen selber die Vorstellung des Auskriechens des Schmetterlings aus der Puppe ein von göttlichen Mächten in die Natur hineingepflanztes Symbolum für die Unsterblichkeit ist. Man muss selber daran glauben, sonst glauben einem die Kinder nicht.

Solche Dinge muss man anregen in den Kindern, und sie werden dann besonders wirksam sein in den Kindern, wenn man zeigen kann, wie ein Wesen in vielen Gestalten leben kann, [eine Urgestalt in vielen einzelnen Gestalten]. Aber es kommt darauf an, das Empfindungsgemäße, nicht das Weltanschauungsgemäße im religiösen Unterricht zu pflegen. Sie können zum Beispiel die Gedichte über die Metamorphose der Pflanzen [und] der Tiere ganz gut religiös verwenden, nur müssen Sie die Gefühle, die Empfindungen, die von Zeile zu Zeile gehen, verwenden. Und Sie können in ähnlicher Weise die Natur betrachten, bis die 4. Klasse vollendet ist. Da müssen Sie namentlich auch die Vorstellung immer wieder anregen, dass der Mensch im ganzen Weltenall drinnensteht mit all seinem Denken und all seinem Tun. Und Sie müssten auch diese Vorstellung anregen, dass in dem, was in uns lebt, auch der Gott lebt. Und immer wieder müssen Sie auf solche Vorstellungen zurückkommen: Im Baumblatt lebt das Göttliche, in der Sonne lebt das Göttliche, in der Wolke und im Flusse lebt das Göttliche. Aber das Göttliche lebt auch im Blutkreislauf; das Göttliche lebt im Herzen, in dem, was du fühlst, in dem, was du denkst. Also immer die Vorstellung entwickeln, dass der Mensch auch ausgefüllt ist vom Göttlichen.

Dann muss man sehr stark schon in diesen Jahren die Vorstellung hervorrufen, dass der Mensch verpflichtet ist, weil er den Gott darstellt, [weil er das Göttliche offenbart], ein guter Mensch zu sein. Der Mensch tut dem Gott Schaden, wenn er nicht gut ist. Der Mensch ist nicht um seiner selbst willen in der Welt, religiös gedacht, sondern er ist in der Welt zur Offenbarung des Göttlichen. Man drückt das oft so aus, dass man sagt: Der Mensch ist nicht um seiner selbst willen da, sondern «zur Ehre Gottes». - Zur «Ehre» bedeutet dann aber in Wirklichkeit «zur Offenbarung». Wie es ja auch nicht heißt in Wirklichkeit: «Ehre sei Gott in der Höhe», sondern: «Es offenbaren sich die Götter in der Höhe.» So ist auch der Satz, dass der Mensch «zur Ehre Gottes» da ist, so zu fassen: Er ist da, damit er durch seine Taten und sein ganzes Fühlen das Göttliche ausdrückt. Und wenn er etwas Schlechtes tut, wenn er unfromm und ungut ist, so tut er etwas, was dem Gotte zur Schmach wird, wodurch der Gott selbst entstellt wird, zu etwas Unschönem wird.

Diese Vorstellung muss man besonders hereinbringen. Also das Innewohnen des Gottes in dem Menschen, das ist etwas, was schon auf dieser Stufe verwendet werden muss. Auf dieser Stufe würde ich noch von jeder Christologie absehen und nur aus der Natur und aus Naturvorgängen heraus eben das göttliche Vatergefühl erwecken. Und ich würde versuchen, daran zu knüpfen allerlei Besprechungen über Motive des Alten Testaments, namentlich auch soweit sie verwendbar sind - und sie sind es, wenn sie nur richtig behandelt werden -, die Psalmen Davids, das Hohe Lied und so weiter. Das wäre also die erste Stufe.

Bei der zweiten Stufe, die also jetzt die vier höheren Klassen umfassen würde, würde es sich darum handeln, dass man viel bespricht mit den Kindern die Begriffe von Schicksal, Menschenschicksal. Dem Kinde wäre also eine Vorstellung beizubringen von dem, was Schicksal ist, sodass das Kind wirklich fühlt, dass der Mensch ein Schicksal hat.

Den Unterschied dem Kinde beizubringen zwischen dem, was einen zufällig bloß trifft, und dem, was Schicksal ist, das ist wichtig. Also man muss den Begriff des Schicksals mit dem Kinde behandeln. Die Frage, wann einen etwas als Schicksal trifft, oder wann einen etwas zufällig trifft, die lässt sich nicht definitionsgemäß erläutern. Man kann [sie] aber vielleicht an Beispielen erläutern. Ich will sagen, wenn ich empfinde bei einem Ereignis, das mich trifft, dass ich das Ereignis so wie gesucht habe, dann ist es Schicksal. Wenn ich nicht empfinden kann, dass ich es gesucht habe, aber besonders stark empfinden kann, dass es mich überrascht und dass ich viel daran lernen kann für die Zukunft, dann ist es ein Zufall, dann wird es erst Schicksal. Es muss an diesem, was nur empfindungsgemäß erlebt werden kann, der Unterschied zwischen «vollendetem Karma» und «aufgehendem, werdendem Karma» dem Kinde allmählich beigebracht werden. Man muss wirklich die Schicksalsfrage im Sinne der Karmafrage allmählich mit dem Kinde behandeln.Dass es in der Empfindung Unterschiede gibt, darüber werden Sie Genaueres in der neuesten Auflage meiner «Theosophie» finden. Da habe ich diese Frage einmal behandelt in dem Kapitel «Reinkarnation und Karma», das ganz neu bearbeitet ist. Da habe ich versucht, herauszuarbeiten, wie man den Unterschied empfinden [kann]. Da können Sie [den Kindern] durchaus schon klarmachen, dass es eigentlich zweierlei Ereignisse gibt. Bei dem einen empfindet man eben mehr, dass man es gesucht hat: Zum Beispiel, wenn man einen Menschen kennenlernt, so empfindet man meistens, dass man ihn gesucht hat. Wenn einen ein Naturereignis trifft, in das man verquickt ist, dann empfindet man, dass man viel daran lernen kann für die Zukunft. Trifft einen etwas durch einen Menschen, so ist es meist erfülltes Karma. Selbst in einer solchen Weise, dass Sie sich hier zusammenfinden zum Beispiel in einem Lehrerkollegium in der Waldorfschule, ist ein erfülltes Karma. Man findet sich so zusammen, weil man sich gesucht hat. Das lässt sich aber nicht definitionsgemäß klarmachen, sondern nur empfindungsgemäß. Man muss dem Kinde viel über allerlei besondere Schicksale sprechen, vielleicht in Erzählungen, worin Schicksalsfragen spielen. [Man kann manches sogar wiederholen aus den Märchenerzählungen, indem man die Märchen noch einmal durchnimmt, in denen Schicksalsfragen spielen.] Namentlich kann man auch in der Geschichte solche Beispiele aufsuchen, wo man an einzelnen Personen sieht, wie sich ein Schicksal erfüllt. Die Schicksalsfrage ist also zu besprechen, um von dieser Seite auf den Ernst des Lebens hinzuweisen.

Und dann möchte ich Ihnen klarmachen, was das eigentlich Religiöse im anthroposophischen Sinne ist. Das Religiöse im Sinne der Anthroposophie ist das Gefühlsmäßige, [das], was wir aus der Weltanschauung an Gefühlen aufnehmen für Welt und Geist und Leben. Die Weltanschauung selber ist eine Sache des Kopfes, das Religiöse aber geht immer aus dem ganzen Menschen hervor. Daher ist eine Religion, die Bekenntnisreligion ist, eigentlich nicht wirklich religiös. Dasjenige, worauf es ankommt, ist, dass in der Religion der ganze Mensch, und zwar hauptsächlich Gefühl und Wille, lebt. Dasjenige, was an Weltanschauungsinhalt in der Religion lebt, das ist eigentlich nur zum Exemplifizieren, zur Unterstützung, zur Vertiefung des Gefühls und zur Erstarkung des Willens. Das ist das, was aus der Religion so fließen soll: dass der Mensch über das, was einem die vergänglichen, irdischen Dinge an Gemütsvertiefung und Willenserstarkung geben können, hinauswächst.

Von der Schicksalsfrage wäre dazu überzugehen, den Unterschied zu besprechen zwischen dem, was man von den Eltern ererbt hat, im Gegensatz zu dem, was man aus einem früheren Erdenleben mitbringt. In der zweiten Stufe werden die früheren Erdenleben herangezogen, und alles wird beigetragen, damit ganz verstandesmäßig, gefühlsmäßig begriffen wird, dass der Mensch in wiederholten Erdenleben lebt.

Und dann sollte durchaus berücksichtigt werden, dass der Mensch zunächst sich in drei Stufen zum Göttlichen erhebt. - Also, nachdem man mit dem Schicksalsbegriff beigebracht hat langsam, in Erzählungen, den Vererbungsbegriff, den Begriff der wiederholten Erdenleben, geht man über zu den drei Stufen des Göttlichen:

Erstens zu dem Göttlichen, das zu dem Engelwesen führt, das für jeden einzelnen Menschen persönlich da ist. Und da bespricht man, wie der einzelne Mensch von Leben zu Leben geführt wird durch seinen persönlichen Genius. Also dieses Persönlich-Göttliche, das im Menschen führend ist, das wird zuerst besprochen.

Zweitens versucht man nun zu erklären, dass es höhere Götter gibt, die Erzengel, und dass die dazu da sind - man kommt da allmählich hinein in das, was man in der Geschichte, in der Geografie betrachten kann —, dass die Erzengel dazu da sind, um Menschengruppen zu dirigieren, also Völkermassen und dergleichen. Das muss scharf so beigebracht werden, dass das Kind unterscheiden lernt zwischen dem Gott, von dem zum Beispiel der Protestantismus spricht, der eigentlich nur der Engel ist, und zwischen dem Erzengel, der etwas Höheres ist als dasjenige, was eigentlich in der evangelischen Religionslehre überhaupt vorkommt.

Drittens ist dann nun auch der Begriff des Zeitgeistes beizubringen als eines waltenden Göttlichen über Perioden hin. Da kommt man in den Zusammenhang zwischen der Geschichte und der Religion. Und erst, wenn man solche Begriffe beigebracht hat, geht man [dazu] über, so etwa im zwölften Jahr - wir können es ja jetzt nicht so machen; wir werden zwei Stufen machen; die Kinder können durchaus schon früher hören, was sie dann später besser verstehen -, nachdem wir die drei Stufen dem Kinde möglichst beigebracht haben, gehen wir über zur eigentlichen Christologie, indem wir die Weltentwicklung in die zwei Teile teilen: in die vorchristliche, die eine Vorbereitung war, und in die christliche, die eine Erfüllung ist. Es muss der Begriff eine große Rolle spielen, dass sich das Göttliche durch den Christus offenbarte «in der Fülle der Zeiten».

Und dann gehe man auch erst über zu den Evangelien. Bis dahin verwende man, insofern man Erzählungen braucht, um den Begriff der Engel, Erzengel und des Zeitgeistes zu erklären, das Alte Testament. Man macht aus dem Alten Testament heraus, zum Beispiel das Eintreten eines neuen Zeitgeistes, dem Kinde klar an der Erscheinung des Moses, gegenüber dem früheren Zeitgeist, wo die Offenbarung des Moses noch nicht vorhanden war. Dann macht man wiederum klar, dass ein neuer Zeitgeist auftritt im 6. Jahrhundert der vorchristlichen Zeit. Dazu verwendet man zuerst das Alte Testament. Und dann, wenn man zur Christologie übergegangen ist, aber es so erfasst hat in einer langen vorbereitenden Zeit, dann gehe man über zu den Evangelien und versuche, einzelne Glieder der Evangelien herauszunehmen, und immer wie etwas Selbstverständliches die Vierheit der Evangelien beizubringen, indem man sagt: Wie ein Baum von vier [verschiedenen] Seiten fotografiert werden kann, um richtig gesehen zu werden, so sind die vier Evangelien wie vier Gesichtspunkte. Man nehme einmal das Matthäus-Evangelium, einmal das Markus-Evangelium, einmal das Lukas-Evangelium, einmal das Johannes-Evangelium und lege gerade besonderen Wert darauf, dass das immer gefühlt wird. Auf den Gefühlsunterschied lege man ganz und gar den Hauptwert.

Das wäre also die zweite Stufe mit ihrem Lehrinhalt. Der Tenor der ersten Stufe ist der, dass dem werdenden Menschen beigebracht werden sollte alles dasjenige, was kund werden kann vermittels des Göttlichen in der Natur durch Weisheit.

Auf der zweiten Stufe ist die Umwandlung: Der Mensch erkennt das Göttliche durch Weisheit allein nicht, sondern durch die wirkende Liebe.

Das ist der Tenor, das Leitmotiv in den beiden Stufen.

Jemand fragt: Soll man Sprüche lernen lassen?

RUDOLF STEINER: Ja, vorzugsweise aus dem Alten Testament, später aus dem Neuen Testament. Aber nicht die Sprüche, die oftmals in Gebetbüchern enthalten sind, die sind zumeist trivial. Also Sprüche aus der Bibel, und auch dasjenige, was wir haben in der Anthroposophie an Sprüchen. Wir haben ja allerlei Sprüche, die können gut verwender- werden itdiesem anthtoposophischen Religionsunterricht.

JOHANNES GEYER [vermutlich]: Soll man die Zehn Gebote lehren?

RUDOLF STEINER: Die Zehn Gebote sind ja im Alten Testament enthalten, aber es muss der Ernst der Sache immer klargemacht werden. Ich habe ja immer betont, es steht auch da drinnen, dass man den Namen des Gottes nicht eitel aussprechen soll. Das wird ja übertreten fast von jedem Kanzelredner, indem der Name des Christus fortwährend eitel ausgesprochen wird. Das muss natürlich alles gefühlsmäßig vertieft werden. Der Religionsunterricht soll überhaupt gegeben werden nicht in Bekenntnisform, sondern in gefühlsmäßiger Vertiefung. Das Credo ist als solches nicht die Hauptsache, sondern dasjenige, was empfunden wird beim Credo; nicht der Glaube an den Vatergott, an den Sohngott, an den Geistgott, sondern was man empfindet dem Vater, dem Sohne, dem Geist gegenüber. So, dass immer in den Seelengründen waltet:

Gott nicht erkennen ist eine Krankheit;

Christus nicht erkennen ist ein Schicksal, ein Unglück;

den Geist nicht erkennen ist eine Beschränktheit der Menschenseele.

WALTER JOHANNES STEIN [vermutlich]: Soll man das Historische den Kindern nahebringen, was mit dem Zarathustra zusammenhängt: den Gang der Zarathustra-Individualität bis zur Offenbarung des Christentums? Die Geschichte von den beiden Jesusknaben?

RUDOLF STEINER: Man muss den Religionsunterricht abschließen, indem man den Kindern diese Zusammenhänge beibringt, selbstverständlich sehr vorsichtig. Die erste Stufe ist durchaus mehr Naturreligion, die zweite mehr historische Religion.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Für den Naturgeschichtsunterricht ist wohl auch die Zweckmäßigkeitslchre zu vermeiden? Der Schmeil’sche Leitfaden für Botanik und Zoologie - der ist aber teleologisch.

RUDOLF STEINER: Bei den Büchern bitte ich durchaus zu berücksichtigen, dass ich sie nur betrachtet wissen möchte zu Ihrer Information bezüglich der Tatsachen. Sie können schlechtweg voraussetzen, dass die Methoden, die da drinnen befolgt sind, auch in der Anschauungsweise, durchaus von uns zu vermeiden sind. Bei uns müssen eben alle Dinge wirklich neu werden. Diese schrecklichen Dinge, die man eben nur so charakterisieren kann: Der gute Gott hat den Kork erschaffen, damit man Champagnerpfropfen daraus machen kann - diese Gesinnung, die natürlich solche Bücher ganz durchdringt, die müssen wir vollständig vermeiden. Für uns sind diese Bücher nur da, damit wir uns über die Tatsachen informieren. So ist es auch in der Geschichte. Da ist nicht minder alles Kohl, was an Urteil hineingeflossen ist. In der Naturgeschichte erst recht.

Es scheint mir zum Beispiel nicht schlimm, wenn man den Brehm verwenden würde, wenn solche Dinge aktuell werden sollten. Im Brehm sind solche Trivialitäten vermieden. Er ist ja ein bisschen spießig. Es wäre ganz gut, wenn man solche Dinge herausschreiben würde, und die Erzählungen [dabei] mehr zugrunde legen würde. Das würde vielleicht das Beste sein. Er ist ja philiströs geschrieben, der alte Brehm; der neue kommt nicht in Betracht, der ist wiederum von einem Modernen bearbeitet.

Sie können ungefähr annehmen, dass alles, was vom Jahre 1885 an an Schulbüchern erzeugt worden ist, schlechtes Zeug ist. Seit jener Zeit ist alle Pädagogik in der furchtbarsten Weise zurückgegangen und in die Phrase hineingekommen.

HERTHA KOEGEL: Wie muss man in der Naturgeschichte den Menschen durchnehmen? Wie soll man das [in der 4. Klasse] anfangen?

RUDOLF STEINER: Für den Menschen finden Sie fast alles irgendwie in meinen Zyklen zerstreut. Es ist fast alles irgendwo gesagt. Und dann ist ja auch vieles im Seminarkursus angedeutet. Sie brauchen es nur umzusetzen für die Schule. Die Hauptsache ist, dass Sie sich an die Tatsachen halten, aber auch an die Tatsachen psychologischer und

spiritueller Art. Sie nehmen zunächst den Menschen durch nach der Formung des Knochensystems; da können Sie ja nicht unsicher sein. Dann gehen Sie über zum Muskelsystem, zum Drüsensystem. Am Muskelsystem bringen Sie den Kindern bei den Begriff des Willens, am Nervensystem den Begriff des Denkens. Also halten Sie sich an das, was Sie aus der Anthroposophie kennen. Es ist notwendig, dass Sie sich ja nicht beirren lassen durch ein heutiges schablonenmäßiges Buch. Nehmen Sie sich sogar lieber - Sie brauchen ja nicht für Ihre 4. Klasse etwas, was «auf der Höhe der Wissenschaft» steht - eine ältere Beschreibung und halten Sie sich daran. Alle diese Dinge sind, wie gesagt, spottschlecht geworden, seit den Achtzigerjahren. Aber in den Zyklen finden Sie überall Anhaltspunkte.

WALTER JOHANNES STEIN: Ich habe hier zusammengestellt eine Tabelle der geologischen Formationen im Anschluss an das gestern Gesagte.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ja, Sie dürfen da nie pedantisch parallelisieren. Ja, wenn Sie zu der Primitivform, zum Urgebirge, gehen, haben Sie die polarische Zeit. Die paläozoische entspricht der hyperboreischen Epoche, auch da dürfen Sie nicht pedantisch die einzelnen Tierformen nehmen. Dann haben Sie das mesozoische Zeitalter dem lemurischen im Wesentlichen entsprechend. Dann die erste und zweite Säugetierfauna oder das känozoische Zeitalter, das ist das atlantische Zeitalter. Das atlantische ist nicht älter als etwa neuntausend Jahre. — Diese fünf Zeitalter, das primitive, paläozoische, mesozoische, känozoische, anthropozoische, können Sie also geradezu parallelisieren, nur nicht pedantisch.

WALTER JOHANNES STEIN: Es ist einmal [gesagt], dass die Abzweigung der Fische und die Abzweigung der Vögel gewöhnlich nicht richtig angegeben werden, zum Beispiel bei Haeckel.

RUDOLF STEINER: Die Abzweigung der Fische wird allerdings etwas zurückgeschoben im Devon’schen Zeitalter.

WALTER JOHANNES STEIN: Wie sieht der Mensch in diesem Zeitalter aus?

RUDOLF STEINER: Im primitiven Zeitalter ist er fast ganz von ätherischer Substanzialität. Er lebt zwischen den anderen Erscheinungen. Er hat noch keine Dichte. Er wird dichter im hyperboreischen Zeitalter. Nur diese Tierformen, die eigentlich der Niederschlag sind, die leben. Der Mensch lebt auch, nicht in geringer Kraft, er hat eine ungeheure Kraft. Aber er hat nichts an sich von einer Substanz, die zurückbleiben könnte. Daher gibt es keine Überreste. Er lebt durch die ganzen Zeitalter hindurch und bekommt erst etwa im känozoischen Zeitalter äußere Dichte. Wenn Sie sich erinnern, wie ich das lemurische Zeitalter beschrieben habe, das sind fast ätherische Landschaften. Das ist alles da, aber es sind keine geologischen Überreste da. Aber wenn Sie das berücksichtigen, dass eigentlich hier durch alle fünf Zeitalter überall schon Mensch ist: Mensch ist überall. Dann hier [Rudolf Steiner demonstriert an der Tabelle] im ersten Zeitalter (Primitivform) ist außer dem Menschen eigentlich noch nichts anderes vorhanden; das sind nur geringfügige Überreste. Das Eozoon canadense ist eigentlich mehr Formation, etwas, was sich als Figur bildet; das ist nicht ein wirkliches Tier. Dann hier in der hyperboreisch-paläozoischen Zeit tritt das Tierische schon auf, aber in Formen, die später nicht mehr erhalten sind. Hier in der lemurisch-mesozoischen Zeit tritt das Pflanzenreich auf, und hier tritt in der Atlantis, in der känozoischen Zeit, das Mineralreich auf; eigentlich schon in der letzten Zeit hier, in diesen zwei früheren Zeitaltern schon. In den beiden letzten Unterrassen der lemurischen Zeit.

WALTER JOHANNES Stein: Ist der Mensch schon als Kopfmensch, Brustmensch und Gliedmaßenmensch da?

RUDOLF STEINER: Er ist ähnlich wie ein Kentaur. Stark tierischer Unterleib und vermenschlicht der Kopf.

WALTER JOHANNES STEIN: Man hat fast den Eindruck, als wäre es eine Zusammensetzung, eine Symbiose aus drei Wesenheiten.

RUDOLF STEINER: So ist es auch.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Wie ist es möglich, dass dann im Karbon schon Pflanzenreste sind?

RUDOLF STEINER: Das sind keine Pflanzenreste. Was da so ausschaut wie Pflanzenreste, das ist dadurch entstanden, dass zum Beispiel der Wind weht und ganz bestimmte Hemmungen findet. Sagen wir, der Wind weht und bringt so etwas wie Pflanzenformen hervor, die sich geradeso erhalten haben wie der Tritt der Tiere. (Hyperboreisches Zeitalter.) Es ist eine Art Pflanzenkristallisation. Es ist eine Einkristallisierung mit Pflanzenformen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Also die Bäume, die man da heraustheoretisiert hat, die existierten gar nicht?

RUDOLF STEINER: Nein, die sind als Baumformen vorhanden gewesen. Die ganze Flora der Karbonzeit ist nicht [physisch] vorhanden. Denken Sie sich einen Wald, der eigentlich in seiner Ätherform vorhanden ist, und der daher in bestimmter Weise den Wind aufhält. Dadurch bilden sich da in der Form fast Stalaktiten. Was sich bildet, das sind nicht Überreste von [Pflanzen]. Da bilden sich Formen einfach durch die Konfiguration, die da entsteht durch Elementarwirkungen. Das sind nicht wirkliche Überreste. Man kann nicht sagen, dass das so ist wie in der Atlantis. Da haben sich dann die Sachen erhalten, und in der letzten lemurischen Zeit auch, aber in der Karbonzeit ist keine Rede davon, dass Pflanzenüberreste da sind. Nur tierische Überreste. Aber da handelt es sich auch in der Mehrzahl um solche Tiere, die nur zu parallelisieren sind mit unserer Kopfform.

Jemand fragt: Wann richtete sich der Mensch auf? Man kann den Punkt nicht einordnen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das ist doch nicht gut, wenn Sie sich diese Vorstellungen so festnageln. Denn, nicht wahr, manche Rasse richtete sich eben früher auf und manche später. Man kann nicht den bestimmten Punkt festnageln. So ist es in der Wirklichkeit nicht.

Jemand fragt: Wenn das Pistill dem Monde zugeordnet ist, die Narbe der Sonne, wie drückt sich da die Bewegung von Sonne und Mond aus?

RUDOLF STEINER: Sie müssen sich die Sache so vorstellen. [Rudolf Steiner zeichnet.]

Die Narbe geht nach oben, das wäre die [Sonnen]bahn; und das Pistill bewegt sich ringsherum, da ist man in der [Monden]bahn darinnen. Da haben wir ein Abbild dieser Sonnen-Erdenbahn, die ich gestern aufgezeichnet habe. Der Mond bewegt sich aber um die Erde. Der ist im Pistill drinnen. [Rudolf Steiner demonstriert an der Zeichnung.] Das erscheint daher so, die Mondenbahn, die auch natürlich so herumgeht, aber nicht in gerader Linie für die Verhältnisse erscheint. Die Sonnenbahn ist die Narbe. Dieser Kreis ist eine Nachbildung der Spirale, die ich gestern gezeichnet habe. Es ist auch eine Spirale, eine Schraube.

WALTER JOHANNES STEIN: Wir haben gehört, dass die Temperamente mit dem Übergewicht der einzelnen Leiber zusammenhängen. Im Zyklus 20 ist nun die Rede davon, dass ein Übergewicht besteht des physischen Leibes gegenüber dem Ätherleib, des Ätherleibes gegenüber dem Astralleib, des Astralleibes gegenüber dem Ätherleib, des Ich gegenüber dem Astralleib. - Ist hier ein Zusammenhang mit den Temperamenten? - Im 18. Zyklus ist eine Figur erwähnt, die gibt das richtige Verhältnis der Leiber an.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das gibt das Kräfteverhältnis an.

WALTER JOHANNES Stein: Ist da weiter eine Beziehung zu den Temperamenten?

RUDOLF STEINER: Keine andere, als die im Seminarkursus angegeben wurde.

WALTER JOHANNES Stein: Es wurde gesagt, dass Melancholie durch ein Übergewicht des physischen Leibes entsteht. Ist das ein Übergewicht des physischen Leibes über den Ätherleib?

RUDOLF STEINER: Nein, überhaupt ein Übergewicht über die anderen Leiber.

Es wird nach einem Elterntag gefragt.

RUDOLF STEINER: Er sollte schon vorhanden sein, aber es wäre gut, wenn er nicht allzu oft wäre, sonst versickert das Interesse und die Eltern kommen nicht mehr. Es muss so eingerichtet werden, dass die Eltern auch wirklich kommen. Wenn er zu oft ist, würde es eine übel empfundene Sache. Man sollte gerade in Bezug auf Schuleinrichtungen keine Projekte machen, die nicht erfüllt werden. Man sollte sich nur vornehmen, was auch wirklich geschehen kann. Dreimal im Jahr einen Elterntag ansetzen, das würde ich für gut finden. Dann würde ich aber vorschlagen, dass er möglichst feierlich behandelt wird, dass also Karten gedruckt werden und allen einzelnen Eltern diese Karten zugeschickt werden.

Vielleicht könnte man es so einrichten, dass man den ersten so im Anfang des Schuljahres festsetzt; mehr als Courtoisie, damit man mit den Eltern wiederum in Kontakt kommt. Dann in der Mitte des Schuljahres einen Elternabend und einen am Ende des Schuljahres. Die beiden letzten sind dann die eigentlich maßgebenden. Der erste ist nur eine Courtoisie, da mögen die Eltern dann quasseln. Man könnte die Kinder ja etwas deklamieren lassen, etwas Eurythmie machen lassen und so weiter.

Elternsprechstunden kann man einrichten; das ist ganz gut. Im Allgemeinen werden Sie ja wahrscheinlich die Erfahrung machen, dass sich die Elternschaft zu wenig kümmert, außer die anthroposophischen Eltern.

HERBERT HAHN bittet Rudolf Steiner, ihm doch etwas zu sagen über die Popularisierung der Geisteswissenschaft, besonders in Bezug auf die Nachmittagskurse für Arbeiter.

RUDOLF STEINER: Nun, diese Popularisierung muss sich mehr darauf beziehen, den richtigen Gang einzuhalten. Ich bin im Allgemeinen nicht dafür, dass man das Popularisieren durch Trivialisierung bewirkt. Ich meine also, dass man zunächst das Buch «Theosophie» zugrunde legt und von Fall zu Fall herauszukriegen versucht, was ein bestimmtes Auditorium schwer oder leicht versteht. Sie werden sehen, dass die letzte Auflage der «Theosophie» viele Winke enthält, gerade wenn man sie als Lehrstoff vorträgt. Dann würde ich übergehen zu der Besprechung einzelner Partien von «Wie erlangt man Erkenntnisse der höheren Welten?», aber niemals mit der Tendenz, dass die Leute Hellseher werden sollen. Sie sollen sich nur informieren über die Wege des Hellsehers, sodass sie wissen, auf welche Weise man zu diesen Wahrheiten kommt. Sie sollen das Gefühl bekommen: Durch gesunden Menschenverstand kann man begreifen und wissen, auf welchem Wege diese Dinge erfasst werden. Dann kann man richtig populär behandeln «Die geistige Führung des Menschen und der Menschheit». Das wären für eine populäre Darstellung die drei Bücher. Im Übrigen muss man sich nach dem Auditorium richten.

Es wird noch über einzelne Kinder gesprochen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das Wichtigste ist, dass immer Kontakt da ist, dass der Lehrer mit den Schülern eine richtige Einheit bildet. Das ist im Grunde genommen fast durch alle Klassen hindurch in sehr schöner, erfreulicher Weise vorhanden gewesen. Ich war sehr erfreut über die Sache.

Ich kann Ihnen sagen, ich werde viel, auch wenn ich nicht da bin, an diese Schule herdenken. Denn, nicht wahr, wir müssen ja alle durchdrungen sein:

Erstens von dem Ernst der Sache. Es ist eine ungeheuer wichtige Sache für uns gerade.

Zweitens müssen wir durchdrungen sein von der Verantwortung, die wir tragen, sowohl der Anthroposophie gegenüber [wie der Kulturbewegung gegenüber], der sozialen Frage gegenüber.

Und dann drittens das, was wir als Anthroposophen besonders uns vorhalten müssen: die Verantwortung gegenüber den Göttern.

Wir müssen durchaus innerhalb der Lehrerschaft daran festhalten, dass wir Menschen nicht um unserer selbst willen da sind, sondern um die göttlichen Pläne mit der Welt zu verwirklichen. Halten wir uns das vor, dass wir eigentlich, indem wir das eine oder andere tun, die Intentionen der Götter ausführen, dass wir gewissermaßen die Gehäuse sind, um das zu verwirklichen, was als Strömungen herunterfließt und sich verwirklichen will in der Welt; dass wir keinen Augenblick ermangeln, den ganzen Ernst und die ganze Würde zu empfinden.

Empfinden Sie diese Würde, diesen Ernst, diese Verantwortung. Ich werde Ihnen mit solchen Gedanken entgegenkommen. Wir werden uns mit solchen Gedanken begegnen.

Das wollen wir heute noch als unsere Empfindung aufnehmen und in diesem Sinne eine Weile auseinandergehen, und dann uns immer wiederum geistig treffen, um die Kraft zu bekommen für dieses wirklich große Werk.

Third Conference

First, there is a discussion about the individual children whom Rudolf Steiner had observed that morning.

[WALTER JOHANNES STEIN, who was temporarily teaching the first grade, asks a question.

RUDOLF STEINER: Reading should be developed very strongly from painting and writing. The forms [should be] derived from the artistic.

Only keywords are recorded for the following: Muscles – will; nerves – thinking. Plan; organization; life skills; economics; creation of teaching materials.

E. E. [must be] morally uplifted. [He is a] “Bolshevik.”

This is followed by comments about another student, which are not recorded.

HERTNA KOEGEL suggests starting the morning with the Lord's Prayer.

RUDOLF STEINER: I would find it very nice to begin the lesson with the Lord's Prayer. Then move on to the sayings I will tell you. For the [four] lower classes, I ask that you say the saying in the following way:

The sun's dear light,

It brightens my day;

The soul's spiritual power,

Gives strength to the limbs;

In the sun's light and splendor

I worship you, O God,ca The human strength that you

Have so kindly planted

In my soul,

That I may be industrious

And eager to learn.

From You comes light and strength,

To You flow love and thanks.

The students should feel this as I have spoken it. One should also make clear to them little by little—first they should take in the words—the contrast between the outer and the inner.

The sun's dear light,

It brightens my day;

The soul's spiritual power,

It gives strength to my limbs;

One notices the former by observing how the light brightens the day; the latter [is] the feeling of the soul entering the limbs. Spiritual-soul - physical-bodily: that is what lies in this sentence.

In the sun's light and splendor

I worship, O God,

The human power that You

Have so graciously planted

In my soul,

That I may be industrious

And eager to learn.

Worshipping these two things. Then turning once more to both of them:

From You comes light and strength, (the sun)

To You flow love and thanks. (from within)

This, I would say, is how children should feel: toward the divine in light and in the soul.

You must try to recite this with the children in chorus, with the feeling I have read aloud. First, the children learn it purely verbatim, so that they have the words, meter, and rhythm. Only later do you explain occasionally: Now let's see what's in there. — First they must have it, then explain it. Do not explain it first, nor attach much importance to the children memorizing it. Only in use, little by little, should they learn it by heart. They should first read it formally from your lips. If it goes badly for a long time, four weeks for my part, the better it will go later. The older ones can already write it down; with the youngest, you have to teach it to them little by little. Don't order them to memorize it! If you write it down for them, that's fine; then they have it in your handwriting.

I'll give you the saying for the four higher grades tomorrow.

According to the stenogram, Steiner presented the verse in writing to the teaching staff on September 27, 1919.

The verse for the four higher grades is as follows:

I look at the world;

In which the sun shines,

In which the stars twinkle;

In which the stones lie,

The plants grow alive,

The animals live with feeling,

In which the human being, animated,

Gives dwelling to the spirit;

I look into the soul,

Which lives within me.

The spirit of God weaves

In the light of the sun and the soul,

In the space of the world, out there,

In the depths of the soul, inside.

To you, O spirit of God,

I turn in supplication,

That strength and blessing may

For learning and for work

May grow within me.

This is followed by a longer digression by Steiner on the curriculum of free anthroposophical religious education.

RUDOLF STEINER: This teaching would have to be given in two stages. If you want to engage in anthroposophical teaching with religious goals at all, then you must take the concept of religion much more seriously than it is usually taken. Usually, the concept of religion is distorted by mixing in all kinds of worldviews that do not belong there. As a result, religious tradition carries over from one age to the next precisely those things that we do not want to develop further. Old worldviews are preserved alongside more developed worldviews. These things came to the fore in a grotesque way in the age of Galileo and Giordano Bruno. It is downright humorous how these things are still justified today in apologies. The Catholic Church argued that at that time the Copernican worldview was not recognized, as it had been banned by the Church itself; therefore, Galileo was not allowed to represent it. I do not want to go into that now, but I just want to mention it to tell you that religion must be taken seriously when it comes to anthroposophy.

It is true that anthroposophy is a worldview, and we do not want to bring this worldview into our school as such. However, we must develop the religious feeling that is conveyed by this worldview of the human soul for those children whose parents expressly request it. However, if we want to start from anthroposophy, we must not develop anything wrong, and above all, we must not develop anything premature. We will therefore distinguish between two stages. First, we take the children we have in the four lower classes, and then those we have in the four upper classes.

In the [four] lower classes, we try to discuss things and processes in the human environment with the children in such a way that they develop a sense that spirit lives in nature. This involves things such as those I have given as examples. For example, we want to teach the children the concept of the soul. To do this, it is necessary first of all to familiarize the children with the concept of life itself. The concept of life is conveyed to children by drawing their attention to the fact that people are small at first, then grow up, grow old, get white hair, get wrinkles, and so on. In other words, one points out the seriousness of the human life cycle and actually introduces children to the seriousness of death, with which children will inevitably become familiar.

Then it is by no means unnecessary to make comparisons between what goes on in the human soul when it changes from sleeping to waking. Such things can be discussed with even the youngest children at the first level. Waking and sleeping: discuss the phenomenon of how the soul is at rest, how the human being is immobile in sleep, and so on. Then discuss with the child how the soul permeates the body when it is awake, and draw its attention to the fact that there is a will that stirs in the limbs; draw its attention to the fact that the body gives the soul the senses through which one sees, hears, and so on. Such things are therefore [to be given] as proof that the spiritual reigns in the physical. This should be discussed with the child.

Any superficial doctrine of expediency must be completely avoided. Anthroposophical religious education must not be based on the model of that doctrine of expediency which asks: “Why is there cork in the tree?” ‘So that we can make champagne corks. God wisely arranged it so that we have cork for corks.’ This idea that something is there ‘for a purpose’, that it functions as if guided by human intention [and] plays itself out in nature, is poison; it must not be developed. So we must not introduce banal ideas of expediency into nature.

Nor should we cultivate the idea, so beloved of people, that the unknown is proof of the spirit. Isn't it true that people say: Oh, you can't know that, it's the spirit revealing itself! – Instead of people getting the feeling that One can know about the spirit, the spirit reveals itself in matter — people are so strongly led to believe that where something cannot be explained, there is proof of the divine.

These two things are therefore to be strictly avoided: superficial utilitarianism and such notions of miracles that actually seek miracles as proof of divine intervention.