Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner

GA 300a

25 September 1919, Stuttgart

Second Meeting

Dr. Steiner: Today I want you to summarize all your experiences of the last ten days and then we will discuss what is necessary.

Stockmeyer (the school administrator) reports: We began instruction on September 16, and Mr. Molt gave a short speech to the students. We had to somewhat change the class schedule we had discussed because the Lutheran and Catholic religion teachers were not available at the times we had set. We also had to combine some classes. In addition, we needed to include a short recess of five minutes in the period from 8-10 a.m.

Dr. Steiner: Of course, we can do that, but what happens during that period must remain the free decision of the teacher.

A teacher: During the language classes in the upper grades, it became apparent that some children had absolutely no knowledge of foreign languages. For that reason, at least for now, we must give three hours of English and three hours of French instead of the 1½ hours of each that we had planned. We also had to create a beginners’ class as well as one for more advanced students.

Dr. Steiner: What are you teaching in the eighth grade?

A teacher: The computation of interest. I plan to go on to the computation of discounts and exchanges.

Dr. Steiner: The two seventh- and eighth-grade teachers must remain in constant contact so that when one teacher leaves the class, he brings things to a kind of conclusion. When he returns, he then leads the class through a repetition. In the past few days, have you been able to determine how much the students already know?

A teacher: I was able to make an approximation.

Dr. Steiner: With your small class that certainly would have been possible, but hardly for the other teachers. Certainly, we can try to make it possible for you to change classes an average of once a week, but we must be careful that the exchange takes place only when you finish a topic.

A teacher: The seventh grade knows very little history.

Dr. Steiner: You will probably need to begin something like history from the very beginning in each class, since none of the students will have a proper knowledge of history. The children have probably learned what is common knowledge, but, as I have mentioned in the past, it is unlikely that any of them have a genuine understanding of history. Therefore, you must begin from the beginning in each class.

A teacher: Many parents have been unable to decide whether they should send their children to the independent religious instruction or the Lutheran or Catholic. Many of them wrote both in the questionnaire, since they want their children confirmed for family reasons.

Dr. Steiner: Here we must be firm. It’s either the one or the other. We will need to speak about this question more at a later time. A teacher: An economic question has arisen: Should those students who are paying tuition also purchase their own books? The factory takes care of all of these things for its children, but it could happen that children sit next to one another and one has a book he or she must return and the other a book he or she can keep. This would emphasize class differences.

Dr. Steiner: Clearly we can’t do things in that way, that some children buy their books and then keep them. The only thing we can do is raise the tuition by the amount of the cost of books and supplies, but, in general, we should keep things as they are with the other children. Therefore, all children should return their books.

A teacher: Should we extend that to such things as notebooks? That is common practice here in Stuttgart. Also, how should we handle the question of atlases and compasses?

Dr. Steiner: Of course, the best thing would be to purchase a supply of notebooks and such for each class. The children would then need to go to the teacher when they fill one notebook in order to obtain a new one. We could thus keep track of the fact that one child uses more notebooks than others. We should therefore see that there is a supply of notebooks and that the teacher gives them to the children as needed.

For compasses and other such items, problems arise if we simply allow the children to decide what to buy. Those children with more money will, of course, buy better things, and that is a real calamity. It might be a good idea if all such tools, including things for handwork, belong to the school and the children only use them.

As for atlases, I would suggest the following. We should start a fund for such things and handle the atlases used during the year in much the same way as the other supplies. However, each child should receive an atlas upon graduation. It would certainly be very nice if the children received something at graduation. Perhaps we could even do these things as awards for good work. A larger more beautiful book for those who have done well, something smaller for those who have done less, and for those who were lazy, perhaps only a map. That is certainly something we could do; however, we shouldn’t let it get out of hand.

A teacher: How should we handle the question of books for religious instruction? Until now, instructional materials were provided, but according to the new Constitution, that will probably no longer be so. We thought the children would purchase those books themselves and would pay the ministers directly for their teaching.

Dr. Steiner: I have nothing against doing it that way. However, I think that we should investigate how other schools are handling that, so that everything can move smoothly, at least this year. In the future, we must find our own way of working, but at least for this year, we should do it like the other schools. We need to act in accordance with the public schools. If they do not require the purchase of religion books and separate payment for instruction, we must wait until they do. It would certainly be helpful if we could say we are doing what the public schools are doing.

A teacher: Should we use the secondary schools as our model? Dr. Steiner: No, we should pay more attention to the elementary schools.

A teacher: Nothing is settled there yet.

Dr. Steiner: True. However, I would do what is common in the elementary schools, since the socialist government will not change much at first, but will just leave everything the way it has been. The government will make laws, but allow everything to stay the same.

A teacher: It seems advisable to keep track of what we teach in each class. But, of course, we should not do it the normal way. We should make the entries so that each teacher can orient him- or herself with the work of the other teachers.

Dr. Steiner: Yes, but if we do that in an orderly manner, we will need time, and that will leave time for the children to simply play around. When you are with the children as a teacher, you should not be doing anything else. What I mean is that you are not really in the classroom if you are doing something not directly connected with the children. When you enter the classroom, you should be with the children until you leave, and you should not give the children any opportunity to chatter or misbehave by not being present, for instance, by making entries in a record book or such things.

It would be much better to take care of these things among ourselves. Of course, I am assuming that the class teachers do not get into arguments about that, but respect one another and discuss the subject. If a teacher works with one class, then that teacher will also discuss matters with the others who teach that class. Each teacher will make his or her entries outside of the instructional period. Nothing, absolutely nothing that does not directly interact with the children can occur during class time.

A teacher: Perhaps we could do that during the recesses. Dr. Steiner: Why do we actually need to enter things? First, we must enter them, then someone else must read them. That is time lost for interacting with the students.

A teacher: Shouldn’t we also record when a student is absent?

Dr. Steiner: No, that is actually something we also do not need.

A teacher: If a child is absent for a longer time, we will have to inquire as to what the problem is.

Dr. Steiner: In the context of our not very large classes, we can do that orally with the children. We can ask who is absent and simply take note of it in our journals. That is something that we can do. We will enter that into the children’s reports, namely, how many times a child was absent, but we certainly do not need a class journal for that.

A teacher: I had to stop the children from climbing the chestnut trees, but we want to have as few rules as possible.

Dr. Steiner: Well, we certainly need to be clear that we do not have a bunch of angels at this school, but that should not stop us from pursuing our ideas and ideals. Such things should not lead us to think that we cannot reach what we have set as our goals. We must always be clear that we are pursuing the intentions set forth in the seminar. Of course, how much we cannot achieve is another question that we must particularly address from time to time. Today, we have only just begun, and all we can do is take note of how strongly social climbing has broken out.

However, there is something else that I would ask you to be aware of. That is, that we, as the faculty—what others do with the children is a separate thing—do not attempt to bring out into the public things that really concern only our school. I have been back only a few hours, and I have heard so much gossip about who got a slap and so forth. All of that gossip is going beyond all bounds, and I really found it very disturbing. We do not really need to concern ourselves when things seep out the cracks. We certainly have thick enough skins for that. But on the other hand, we clearly do not need to help it along. We should be quiet about how we handle things in the school, that is, we should maintain a kind of school confidentiality. We should not speak to people outside the school, except for the parents who come to us with questions, and in that case, only about their children, so that gossip has no opportunity to arise. There are people who like to talk about such things because of their own desire for sensationalism. However, it poisons our entire undertaking for things to become mere gossip. This is something that is particularly true here in Stuttgart since there is so much gossip within anthroposophical circles. That gossip causes great harm, and I encounter it in the most disgusting forms. Those of us on the faculty should in no way support it.

A teacher: In some cases, we may need to put less capable children back a grade. Or should we recommend tutoring for these children? Dr. Steiner: Putting children back a grade is difficult in the lower grades. However, it is easier in the upper grades. If it is at all possible, we should not put children back at all in the first two grades.

Specific cases are discussed.

Dr. Steiner: We should actually never recommend tutoring. We can recommend tutoring only when the parents approach us when they have heard of bad results. As teachers, we will not offer tutoring. That is something we do not do. It would be better to place a child in a lower grade.

A teacher speaks about two children in the fourth grade who have difficulty learning.Dr. Steiner: You should place these children at the front of the class, close to the teacher, without concern for their temperaments, so that the teacher can keep an eye on them. You can keep disruptive children under control only if you put them in a corner, or right up at the front, or way in the back of the class, so that they have few neighboring children, that is, no one in front or behind them.

A teacher: Sometimes children do not see well. I know of some children who are falling behind only because they are farsighted and no one has taken that into account.

Dr. Steiner: An attentive teacher will observe organic problems in children such as short-sightedness or deafness. It is difficult to have a medical examination for everything. Such examinations should occur only when the teachers recommend them.

When conventional school physicians perform the examinations, we easily come into problems of understanding. For now we want to avoid the visits of a school physician, since Dr. Noll is not presently here. It would be different if he were. Physicians unknown to the school would only cause us difficulties. The physician should, of course, act as an advisor to the teacher, and the teacher should be able to turn to the physician with trust when he or she notices something with the children.

With children who have learning difficulties, it often happens that suddenly something changes in them, and they show quite sudden improvement. I will visit the school tomorrow morning and will look at some of the children then, particularly those who are having difficulty.

A teacher: My fifth-grade class is very large, and the children are quite different from one another. It is very difficult to teach them all together and particularly difficult to keep them quiet.

Dr. Steiner: With a class as large as that, you must gradually attempt to treat the class as a choir and not allow anyone to be unoccupied. Thus, try to teach the class as a whole. That is why we did that whole long thing with the temperaments.

That children are more or less gifted often results from purely physical differences. Children often express only what they have within themselves, and it would be unjust not to allow the children who are at the proper age for that class (ten to eleven years old) to come along. There will always be some who are weak in one subject or another. That problem often stops suddenly. Children drag such problems along through childhood until a certain grade, and when the light goes on, they suddenly shed the problem. For that reason, we cannot simply leave children behind. We must certainly overcome particularly the difficulties with gifted and slow children.

Of course, if we become convinced that they have not achieved the goal of the previous grade, we must put them back. However, I certainly want you to take note that we should not treat such children as slow learners. If you have children who did not really achieve the goals set for the previous grade, then you need to put them back. However, you must do that very soon.

You can never see from one subject whether the child has reached the teaching goals or not. You may never judge the children according to one subject alone. Putting children back a grade must occur within the first quarter of the school year. The teachers must, of course, have seen the students’ earlier school reports. However, I would ask you to recognize that we may not return to the common teaching schedule simply in order to judge a student more quickly. We should always complete a block, even though it may take somewhat longer, before a judgment is possible.

In deciding to put a child back, we should always examine each individual case carefully. We dare not do something rash. We should certainly not do anything of that nature unthinkingly, but only after a thorough examination and, then, do only what we can justify.

Concerning the question of putting back a child who did not accomplish the goals of the previous school, I should also add that you should, of course, speak with the parents. The parents need to be in agreement. Naturally, you may not tell the parents that their child is stupid. You will need to be able to show them that their child did not achieve what he or she needed at the previous school, in spite of what the school report says. You must be able to prove that. You must show that it was a defect of the previous school, and not of the child.

A teacher: Can we also put children ahead a class? In the seventh grade I have two children who apparently would fit well in the eighth grade.

Dr. Steiner: I would look at their report cards. If you think it is responsible to do so, you can certainly do it. I have nothing against putting children ahead a grade. That can even have a positive effect upon the class into which the children come.

A teacher: That would certainly not be desirable in the seventh grade. Now we can educate them for two years, but if we put them ahead a grade, for only one.

Dr. Steiner: Just because we put the children ahead does not mean that we cannot educate them for two years. We will simply not graduate them, but instead keep them here and allow them to do the eighth grade again. When children reach the age of graduation in the seventh grade, the parents simply take them away. However, the education here is not as pedantic, so each year there is a considerable difference. Next year, we will have just as many bright children as this year, so it would actually be quite good if we were to have children who are in the last grade now, in next year’s last grade, also.

It is certainly clear that this first year will be difficult, especially for the faculty. That certainly weighs upon my soul. Everything depends upon the faculty. Whether we can realize our ideals depends upon you. It is really important that we learn.

A teacher: In the sixth grade I have a very untalented child. He does not disturb my teaching, and I have even seen that his presence in the class is advantageous for the other children. I would like to try to keep the him in the class.

Dr. Steiner: If the child does not disturb the others, and if you believe you can achieve something with him, then I certainly think you should keep him in your class. There is always a disturbance when we move children around, so it is better to keep them where they are. We can even make use of certain differences, as we discussed in detail.

A teacher: In the eighth grade, I have a boy who is melancholic and somewhat behind. I would like to put him in the seventh grade.

Dr. Steiner: You need to do that by working with the child so that he wants to be put back. You should speak with him so that you direct his will in that direction and he asks for it himself. Don’t simply put him back abruptly.

A teacher: There are large differences in the children in seventh grade.

Dr. Steiner: In the seventh and eighth grades, it will be very good if you can keep the children from losing their feeling for authority. That is what they need most. You can best achieve that by going into things with the children very cautiously, but under no circumstances giving in. Thus, you should not appear pedantic to the children, you should not appear as one who presents your own pet ideas. You must appear to give in to the children, but in reality don’t do that under any circumstance. The way you treat the children is particularly important in the seventh and eighth grades. You may never give in for even one minute, for the children can then go out and laugh at you. The children should, in a sense, be jealous (if I may use that expression, but I don’t mean that in the normal sense of jealousy), so that they defend their teacher and are happy they have that teacher. You can cultivate that even in the rowdiest children. You can slowly develop the children’s desire to defend their teacher simply because he or she is their teacher.

A teacher: Is it correct that we should refrain from presenting the written language in the foreign language classes, even when the children can already write, so that they first become accustomed to the pronunciation?

Dr. Steiner: In foreign languages, you should certainly put off writing as long as possible. That is quite important.

A teacher: We have only just begun and the children are already losing their desire for spoken exercises. Can we enliven our teaching through stories in the mother tongue [German]?

Dr. Steiner: That would certainly be good. However, if you need to use something from the mother tongue, then you certainly need to try to connect it to something in the foreign language, to bring the foreign language into it in some way. You can create material for teaching when you do something like that. That would be the proper thing to do. You could also bring short poems or songs in the foreign language, and little stories. In the language classes we need to pay less attention to the grades as such, but rather group the children more according to their ability.

A teacher: I think that an hour and a half of music and an hour and a half of eurythmy per week is too little.

Dr. Steiner: That is really a question of available space. Later, we will be able to do what is needed.

A teacher: The children in my sixth-grade class need to sing more, but I cannot sing with them because I am so unmusical. Could I select some of the more musical children to sing a song?

Dr. Steiner: That’s just what we should do. You can do that most easily if you give the children something they can handle independently. You certainly do not need to be very musical in order to allow children to sing. The children could learn the songs during singing class and then practice them by singing at the beginning or end of the period.

A teacher: I let the children sing, but they are quite awkward. I would like to gather the more musically gifted children into a special singing class where they can do more difficult things.

Dr. Steiner: It would certainly not violate the Constitution if we eventually formed choirs out of the four upper classes and the four lower classes, perhaps as Sunday choirs. Through something like that, we can bring the children together more than through other things. However, we should not promote any false ambitions. We want to keep that out of our teaching. Ambition may be connected only with the subject, not with the person. Taking the four upper classes together and the four lower classes would be good because the children’s voices are somewhat different. Otherwise, this is not a question of the classes themselves. When you teach them, you must treat them as one class. In teaching music, we must also strictly adhere to what we already know about the periods of life. We must strictly take into consideration the inner structure of the period that begins about age nine, and the one that begins at about age twelve. However, for the choirs we could eventually use for Sunday services, we can certainly combine the four younger classes and the four older classes.

A teacher: We have seen that eurythmy is moving forward only very slowly.

Dr. Steiner: At first, you should strongly connect everything with music. You should take care to develop the very first exercises out of music. Of course, you should not neglect the other part, either, particularly in the higher grades.

We now need to speak a little bit about the independent religious instruction. You need to tell the children that if they want the independent religious instruction, they must choose it. Thus, the independent religious instruction will simply be a third class alongside the other two. In any case, we may not have any unclear mixing of things. Those who are to have the independent religious instruction can certainly be put together according to grades, for instance, the lower four and the upper four grades. Any one of us could give that instruction. How many children want that instruction?

A teacher: Up to now, there are sixty, fifty-six of whom are children of anthroposophists. The numbers will certainly change since many people wanted to have both.

Dr. Steiner: We will not mix things together. We are not advocating that instruction, but only attempting to meet the desires. My advice would be for the child to take instruction in the family religion. We can leave those children who are not taking any religious instruction alone, but we can certainly inquire as to why they should not have any. We should attempt to determine that in each case. In doing so, we may be able to bring one or another to take instruction in the family religion or possibly to come to the anthroposophic instruction. We should certainly do something there, since we do not want to just allow children to grow up without any religious instruction at all.

A teacher: Should the class teacher give the independent religious instruction?

Dr. Steiner: Certainly, one of us can take it over, but it does not need to be the children’s own class teacher. We would not want someone unknown to us to do it. We should remain within the circle of our faculty.

With sixty children altogether, we would have approximately thirty children in each group if we take the four upper and four lower classes together. I will give you a lesson plan later. We need to do this instruction very carefully.

In the younger group, we must omit everything related to reincarnation and karma. We can deal with that only in the second group, but there we must address it. From ten years of age on, we should go through those things. It is particularly important in this instruction that we pay attention to the student’s own activity from the very beginning. We should not just speak of reincarnation and karma theoretically, but practically.

As the children approach age seven, they undergo a kind of retrospection of all the events that took place before their birth. They often tell of the most curious things, things that are quite pictorial, about that earlier state. For example, and this is something that is not unusual but rather is typical, the children come and say, “I came into the world through a funnel that expanded.” They describe how they came into the world. You can allow them to describe these things as you work with them and take care of them so that they can bring them into consciousness. That is very good, but we must avoid convincing the children of things. We need to bring out only what they say themselves, and we should do that. That is part of the instruction.

In the sense of yesterday’s public lecture, we can also enliven this instruction. It would certainly be very beautiful if we did not turn this into a school for a particular viewpoint, if we took the pure understanding of the human being as a basis and through it, enlivened our pedagogy at every moment. My essay that will appear in the next “Waldorf News” goes just in that direction. It is called “The Pedagogical Basis of the Waldorf School.” What I have written is, in general, a summary for the public of everything we learned in the seminar. I ask that you consider it an ideal.

For each group, an hour and a half of religious instruction per week, that is, two three-quarter hour classes, is sufficient. It would be particularly nice if we could do that on Sundays, but it is hardly possible. We could also make the children familiar with the weekly verses in this instruction.

A teacher: Aren’t they too difficult?

Dr. Steiner: We must never see anything as too difficult for children. Their importance lies not in understanding the thoughts, but in how the thoughts follow one another. I would certainly like to know what could be more difficult for children than the Lord’s Prayer. People only think it is easier than the verses in the Calendar of the Soul. Then there’s the Apostles’ Creed! The reason people are so against the Apostles’ Creed is only because no one really understands it, otherwise they would not oppose it. It contains only things that are obvious, but human beings are not so far developed before age twenty-seven that they can understand it, and afterward, they no longer learn anything from life. The discussions about the creed are childish. It contains nothing that people could not decide for themselves. You can take up the weekly verses with the children before class.

A teacher: Wouldn’t it be good if we had the children do a morning prayer?

Dr. Steiner: That is something we could do. I have already looked into it, and will have something to say about it tomorrow. We also need to speak about a prayer. I ask only one thing of you. You see, in such things everything depends upon the external appearances. Never call a verse a prayer, call it an opening verse before school. Avoid allowing anyone to hear you, as a faculty member, using the word “prayer.” In doing that, you will have overcome a good part of the prejudice that this is an anthroposophical thing. Most of our sins we bring about through words. People do not stop using words that damage us. You would not believe everything I had to endure to stop people from calling Towards Social Renewal, a pamphlet. It absolutely is a book, it only looks like a pamphlet. It is a book! I simply can’t get people to say, “the book.” They say, “the pamphlet,” and that has a certain meaning. The word is not unnecessary. Those are the things that are really important. Anthroposophists are, however, precisely the people who least allow themselves to be contained. You simply can’t get through to them. Other people simply believe in authority. That is what I meant when I said that the anthroposophists are obstinate, and you can’t get through to them, even when it is justified!

A teacher: My fifth-grade class is noisy and uncontrolled, particularly during the foreign language period. They think French sentences are jokes.

Dr. Steiner: The proper thing to do would be to look at the joke and learn from it. You should always take jokes into account, but with humor. However, the children must behave. They must be quiet at your command. You must be able to get them quiet with a look. You must seek to maintain contact from the beginning to the end of the period. Even though it is tiring, you must maintain the contact between the teacher and the student under all circumstances. We gain nothing through external discipline. All you can do is accept the problem and then work from that.

Your greatest difficulty is your thin voice. You need to train your voice a little and learn to speak in a lower tone and not squeal and shriek. It would be a shame if you were not to train your voice so that some bass also came into it. You need some deeper tones.

A teacher: Who should teach Latin?

Dr. Steiner: That is a question for the faculty. For the time, I would suggest that Pastor Geyer and Dr. Stein teach Latin. It is too much for one person.

A teacher: How should we begin history?

Dr. Steiner: In almost every class, you will need to begin history from the beginning. You should limit yourself to teaching only what is necessary. If, for example, in the eighth grade, you find it necessary to begin from the very beginning, then attempt to create a picture of the entire human development with only a few, short examples. In the eighth grade, you would need to go through the entire history of the world as we understand it.

That is also true for physics. In natural history, it is very much easier to allow the children to use what they have already learned and enliven it. This is one of those subjects affected by the deficiencies we discussed. These subjects are introduced after the age of twelve when the capacity for judgment begins. In the subjects just described, we can use much of what the children have learned, even if it is a nuisance.

A teacher: In Greek history, we could emphasize cultural history and the sagas and leave out the political portion, for instance, the Persian Wars.

Dr. Steiner: You can handle the Persian Wars by including them within the cultural history. In general, you can handle wars as a part of cultural history for the older periods, though they have become steadily more unpleasant. You can consider the Persian Wars a symptom of cultural history.

A teacher: What occurred nationally is less important?

Dr. Steiner: No, for example, the way money arose.

A teacher: Can we study the Constitution briefly?

Dr. Steiner: Yes, but you will need to explain the spirit of the Lycurgian Constitution, for example, and also the difference between the Athenians and the Spartans.

A teacher: Standard textbooks present Roman constitutionalism.

Dr. Steiner: Textbooks treat that in detail, but often incorrectly. The Romans did not have a constitution, but they knew not only the Twelve Laws by heart, but also a large number of books of law. The children will get an incorrect picture if you do not describe the Romans as a people of law who were aware of themselves as such. That is something textbooks present in a boring way, but we must awaken in the children the picture that in Rome all Romans were experts in law and could count the laws on their fingers. The Twelve Laws were taught at that time like multiplication is now.

A teacher: We would like to meet every week to discuss pedagogical questions so that what each of us achieves, the others can take advantage of.

Dr. Steiner: That would be very good and is something that I would joyfully greet, only you need to hold your meeting in a republican form.

A teacher: How far may we go with disciplining the children?

Dr. Steiner: That is something that is, of course, very individual. It would certainly be best if you had little need to discipline the children. You can avoid discipline. Under certain circumstances it may be necessary to spank a child, but you can certainly attempt to achieve the ideal of avoiding that. You should have the perspective that as the teacher, you are in control, not the child. In spite of that, I have to admit that there are rowdies, but also that punishment will not improve misbehavior. That will become better only when you slowly create a different tone in the classroom. The children who misbehave will slowly change if the tone in the classroom is good. In any event, you should try not to go too far with punishment.

A teacher: To alleviate the lack of educational material, would it be possible to form an organization and ask the anthroposophists to provide us with books and so forth that they have? We really should have everything available on the subject of anthroposophy.

Dr. Steiner: We are planning to do something in that direction by organizing the teachers who are members of the Society. We are planning to take everything available in anthroposophy and make it in some way available for public education and for education in general. Perhaps it would be possible to connect with the organization of teachers already within the Anthroposophical Society.

A teacher: We also need a living understanding about the various areas of economics. I thought that perhaps within the Waldorf School, we could lay a foundation for a future economic science.

Dr. Steiner: In that case, we would need to determine who would oversee the different areas. There are people who have a sense for such things and who are also really practical experts. That is, we would need to find people who do not simply lecture about it, but who are really practical and have a sense for what we want to do. Such people must exist, and they must bring the individual branches of social science together. I think we could achieve a great deal in that direction if we undertook it properly. However, you have a great deal to do during this first year, and you cannot spread yourselves too thin. That is something you will have to allow others to take care of, and we must create an organization for that. It must exclude all fanaticism and monkeying around and must be down to Earth. We need people who live in the practicalities of life.

A teacher: Mr. van Leer has already written that he is ready to undertake this.

Dr. Steiner: Yes, he could certainly help. A plan could be worked out about how to do this in general. People such as Mr. van Leer and Mr. Molt and also others who live in the practicalities of economic life know how to focus on such questions and how to work with them. The faculty would perhaps not be able to achieve as much as when we turn directly to experts. This is something that might be possible in connection with the efforts of the cultural committee. Yes, we should certainly discuss all of this.

A teacher: In geology class, how can we create a connection between geology and the Akasha Chronicle?

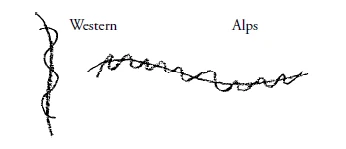

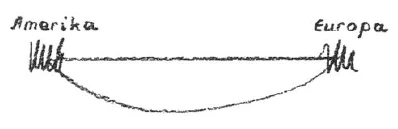

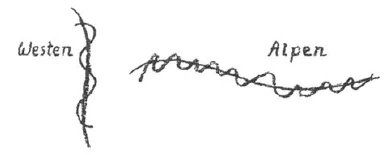

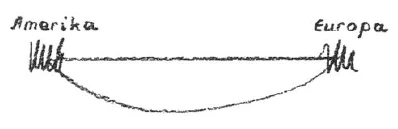

Dr. Steiner: Well, it would be good to teach the children about the formation of the geological strata by first giving them an understanding of how the Alps arose. You could then begin with the Alps and extend your instruction to the entire complex—the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Carpathians, the Altai Mountains, and so forth—all of which are a wave. You should make the entirety of the wave clear to the children. Then there is another wave that goes from North to South America. Thus you would have one wave to the Altai Mountains, to the Asian mountains running from west to east and another in the western part of the Americas going from North to South America, that is, another wave from north to south. That second wave is perpendicular to the first.

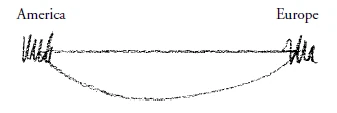

We can begin with these elements and then add the vegetation and animals to them. We would then study only the western part of Europe and the American East Coast, the flora and fauna, and the strata there. From that we can go on to develop an idea about the connections between the eastern part of America and the western part of Europe, and that the basin of the Atlantic Ocean and the west coast of Europe are simply sunken land. From there, we can attempt to show the children in a natural way how that land rhythmically moves up and down, that is, we can begin with the idea of a rhythm. We can show that the British Isles have risen and sunk four times and thus follow the path of geology back to the concept of ancient Atlantis.

We can then continue by trying to have the children imagine how different it was when the one was below and the other above. We can begin with the idea that the British Isles rose and sank four times. That is something that is simple to determine from the geological strata. Thus, we attempt to connect all of these things, but we should not be afraid to speak about the Atlantean land with the children. We should not skip that. We can also connect all this to history. The only thing is, you will need to disavow normal geology since the Atlantean catastrophe occurred in the seventh or eighth millennium.

The Ice Age is the Atlantean catastrophe. The Early, Middle and Late Ice Ages are nothing more than what occurred in Europe while Atlantis sank. That all occurred at the same time, that is, in the seventh or eighth millennium.

A teacher: I found some articles about geology in Pierer’s Encyclopedia. We would like to know which articles are actually from you.

Dr. Steiner: I wrote these articles, but in putting together the encyclopedia there were actually two editors. It is possible that something else was stuck in, so I cannot guarantee anything specifically. The articles about basalt, alluvium, geological formations, and the Ice Age are all from me. I did not write the article about Darwinism, nor the one about alchemy. I only wrote about geology and mineralogy and that only to a particular letter. The entries up to and including ‘G’ are from me, but beginning with ‘H,’ I no longer had the time.

A teacher: It is difficult to find the connections before the Ice Age. How are we to bring what conventional science says into alignment with what spiritual science says?

Dr. Steiner: You can find points of connection in the cycles. In the Quaternary Period you will find the first and second mammals, and you simply need to add to that what is valid concerning human beings. You can certainly bring that into alignment. You can create a parallel between the Quaternary Period and Atlantis, and easily bring the Tertiary Period into parallel, but not pedantically, with what I have described as the Lemurian Period. That is how you can bring in the Tertiary Period. There, you have the older amphibians and reptiles. The human being was at that time only jelly-like in external form. Humans had an amphibian-like form.

A teacher: But there are still the fire breathers.

Dr. Steiner: Yes, those beasts, they did breathe fire, the Archaeopteryx, for example.

A teacher: You mean that animals whose bones we see today in museums still breathed fire?

Dr. Steiner: Yes, all of the dinosaurs belong to the end of the Tertiary Period. Those found in the Jura are actually their descendants. What I am referring to are the dinosaurs from the beginning of the Tertiary Period. The Jurassic formations are later, and everything is all mixed together. We should treat nothing pedantically. The Secondary Period lies before the Tertiary and the Jurassic belongs there as does the Archaeopteryx. However, that would actually be the Secondary Period. We may not pedantically connect one with the other.

[Remarks by the German editor: In the previous paragraphs, there appear to be stenographic errors. The text is in itself contradictory, and it is not consistent with the articles mentioned and the table in Pierer’s Encyclopedia nor with Dr. Steiner’s remarks made in the following faculty meeting (Sept. 26, 1919). The error appears explainable by the fact that Dr. Steiner referred to a table that the stenographer did not have. Therefore, the editor suggests the following changes in the text. The changes are underlined:

You can find points of connection in the cycles. In the Tertiary Period you will find the first and second mammals, and you simply need to add to that what is valid concerning human beings. You can certainly bring that into alignment. You can create a parallel between the Tertiary Period and Atlantis, and easily bring the Secondary Period into parallel, but not pedantically, with what I have described as the Lemurian Period. That is how you can bring in the Secondary Period. There, you have the older amphibians and reptiles. The human being was at that time only jelly-like in external form. Humans had an amphibian-like form.

Yes, all of the dinosaurs belong to the end of the Secondary Period. Those found in the Jura are actually their descendants. What I am referring to are the dinosaurs from the beginning of the Secondary Period. The Jurassic formations are later, and everything is all mixed together. We should treat nothing pedantically. The Secondary Period lies before the Tertiary and the Jurassic belongs there as does the Archaeopteryx. However, that would be actually the Secondary Period. We may not pedantically connect one with the other.]

A teacher: How do we take into account what we have learned about what occurred within the Earth? We can find almost nothing about that in conventional science.

Dr. Steiner: Conventional geology really concerns only the uppermost strata. Those strata that go to the center of the Earth have nothing to do with geology.

A teacher: Can we teach the children about those strata? We certainly need to mention the uppermost strata.

Dr. Steiner: Yes, focus upon those strata. You can do that with a chart of the strata, but certainly never without the children knowing something about the types of rocks. The children need to know about what kinds of rocks there are. In explaining that, you should begin from above and then go deeper, because then you can more easily explain what breaks through.

A teacher: I am having trouble with the law of conservation of energy in thermodynamics.

Dr. Steiner: Why are you having difficulties? You must endeavor to gradually bring these things into what Goethe called “archetypal phenomena.” That is, to treat them only as phenomena. You can certainly not treat the law of conservation of energy as was done previously: It is only a hypothesis, not a law. And there is another thing. You can teach about the spectrum. That is a phenomenon. But people treat the law of conservation of energy as a philosophical law. We should treat the mechanical equivalent of heat in a different way. It is a phenomenon. Now, why shouldn’t we remain strictly within phenomenology? Today, people create such laws about things that are actually phenomena. It is simply nonsense that people call something like the law of gravity, a law. Such things are phenomena, not laws. You will find that you can keep such so-called laws entirely out of physics by transforming them into phenomena and grouping them as primary and secondary phenomena. If you described the so-called laws of Atwood’s gravitational machine when you teach about gravity, they are actually phenomena and not laws.

A teacher: Then we would have to approach the subject without basing it upon the law of gravity. For example, we could begin from the constant of acceleration and then develop the law of gravity, but treat it as a fact, not a law.

Dr. Steiner: Simply draw it since you have no gravitational machine. In the first second, it drops so much, in the second, so much, in the third, and so on. From that you will find a numerical series and out of that you can develop what people call a law, but is actually only a phenomenon.

A teacher: Then we shouldn’t speak about gravity at all?

Dr. Steiner: It would be wonderful if you could stop speaking about gravity. You can certainly achieve speaking of it only as a phenomenon. The best would be if you considered gravity only as a word.

A teacher: Is that true also for electrical forces?

Dr. Steiner: Today, you can certainly speak about electricity without speaking about forces. You can remain strictly within the realm of phenomena. You can come as far as the theory of ions and electrons without speaking of anything other than phenomena. Pedagogically, that would be very important to do.

A teacher: It is very difficult to get along without forces when we discuss the systems of measurement, the CGS system (centimeter, gram, second), which we have to teach in the upper grades.

Dr. Steiner: What does that have to do with forces? If you compute the exchange of one for the other, you can do it.

A teacher: Then, perhaps, we would have to replace the word “force” with something else.

Dr. Steiner: As soon as it is clear to the students that force is nothing more than the product of mass and acceleration, that is, when they understand that it is not a metaphysical concept, and that we should always treat it phenomenologically, then you can speak of forces.

A teacher: Would you say something more about the planetary movements? You have often mentioned it, but we don’t really have a clear understanding about the true movement of the planets and the Sun.

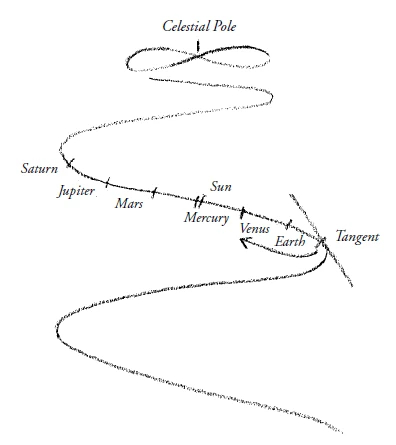

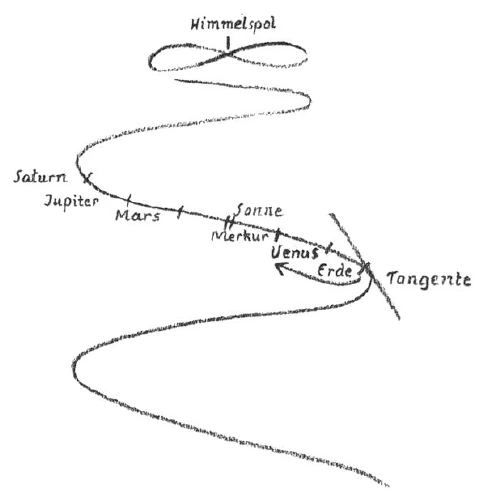

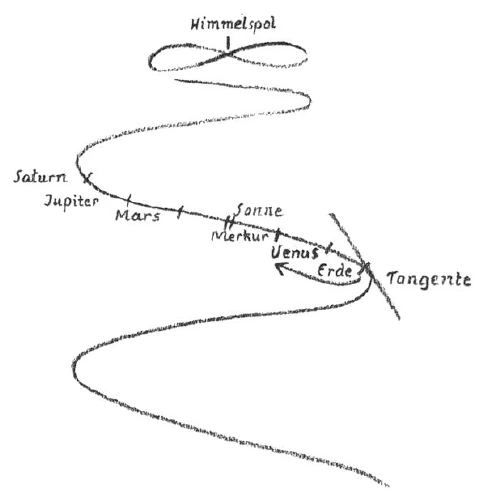

Dr. Steiner: In reality, it is like this [Dr. Steiner demonstrates with a drawing]. Now you simply need to imagine how that continues in a helix. Everything else is only apparent movement. The helical line continues into cosmic space. Therefore, it is not that the planets move around the Sun, but that these three, Mercury, Venus, and the Earth, follow the Sun, and these three, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, precede it. Thus, when the Earth is here and this is the Sun, the Earth follows along. But we look at the Sun from here, and so it appears as though the Earth goes around it, whereas it is actually only following. The Earth follows the Sun. The incline is the same as what we normally call the angle of declination. If you take the angle you obtain when you measure the ecliptic angle, then you will see that. So it is not a spiral, but a helix. It does not exist in a plane, but in space.

A teacher: How does the axis of the Earth relate to this movement?

Dr. Steiner: If the Earth were here, the axis of the Earth would be a tangent. The angle is 23.5×. The angle that encloses the helix is the same as when you take the North Pole and make this lemniscate as the path of a star near the North Pole. That is something I had to assume, since you apparently obtain a lemniscate if you extend this line. It is actually not present because the North Pole remains fixed, that is the celestial North Pole.

A teacher: Wasn’t there a special configuration in 1413?

Dr. Steiner: I already mentioned that today. Namely, if you begin about seven thousand years before 1413, you will see that the angle of the Earth’s axis has shrunk, that is, it is the smallest angle. It then becomes larger, then again smaller. In this way, a lemniscate is formed, and thus the angle of the Earth was null for a time. That was the Atlantean catastrophe. At that time, there were no differences in the length of the day relative to the time of year.

A teacher: Why should the celestial pole, which is in reality nothing other than the point toward which the Earth’s axis is directed, remain constant? It should certainly change over the course of years.

Dr. Steiner: That happens because the movement of the Earth’s axis describes a cone, a double cone whose movement is continuously balanced by the movement of the Earth’s axis. If you always had the axis of the Earth parallel to you, then the celestial pole would describe a lemniscate, but it remains stationary. That is because the movement of the Earth’s axis in a double cone is balanced by the movement of the celestial pole in a lemniscate. Thus, it is balanced.

A teacher: I had changed my perspective to the one you described regarding the movement of the Earth’s axis. I said to myself, The point in the heavens that remains fixed must seem to move over the course of the centuries. It would be, I thought, a movement like a lemniscate, and, therefore, not simply a circle in the heavens during a Platonic year.

Dr. Steiner: It is modified because this line, the axis of the helix, is not really a straight line, but a curve. It only approximates a straight line. In reality, a circle is also described here. We are concerned with a helix that is connected with a circle.

A teacher: How is it possible to relate all this to the Galilean principle of relativity? That is, to the fact that we cannot determine any movement in space absolutely.

Dr. Steiner: What does that mean?

A teacher: That means that we cannot speak of any absolute movement in space. We cannot say that one body remains still in space, but instead must say that it moves. It is all only relative, so we can only know that one body changes its relationship to another.

Dr. Steiner: Actually, that is true only so long as we do not extend our observations into what occurs within the respective body. It’s true, isn’t it, that when you have two people moving relative to one another, and you observe things spatially from a perspective outside of the people (it is unimportant what occurs in an absolute sense), you will have only the relationships of the movement.

However, it does make a difference to the people: Running two meters is different from running three. That principle is, therefore, only valid for an outside observer. The moment the observer is within, as we are as earthly beings, that is, as soon as the observation includes inner changes, then all of that stops. The moment we observe in such a way that we can make an absolute determination of the changes in the different periods of the Earth, one following the other, then all of that stops. For that reason, I have strongly emphasized that the human being today is so different from the human being of the Greek period. We cannot speak of a principle of relativity there. The same is true of a railway train; the cars of an express train wear out faster than those on the milk run. If you look at the inner state, then the relativity principle ceases. Einstein’s principle of relativity arose out of unreal thinking. He asked what would occur if someone began to move away at the speed of light and then returned; this and that would occur. I would ask what would happen to a clock if it were to move away with the speed of light? That is unreal thinking. It has no connection to anything. It considers only spatial relationships, something possible since Galileo. Galileo himself did not distort things so much, but by overemphasizing the theory of relativity, we can now bring up such things.

A teacher: It is certainly curious in connection with light that at the speed of light you cannot determine your movement relative to the source of light.

Dr. Steiner: One of Lorentz’s experiments. Read about it; what Lorentz concludes is interesting, but theoretical. You do not have to accept that there are only relative differences. You can use absolute mechanics. Probably you did not take all of those compulsive ideas into account. The difference is simply nothing else than what occurs if you take a tube with very thin and elastic walls. If you had fluid within it at the top and the bottom and also in between, then there would exist between these two fluids the same relationship that Lorentz derives for light. You need to have those compulsive interpretations if you want to accept these things.

You certainly know the prime example: You are moving in a train faster than the speed of sound and shoot a cannon as the train moves. You hear the shot once in Freiburg, twice in Karlsruhe, and three times in Frankfurt. If you then move faster than the speed of sound, you would first hear the three shots in Frankfurt, then afterward, the two in Karlsruhe, then after that, one shot in Freiburg. You can speculate about such things, but they have no reality because you cannot move faster than the speed of sound.

A teacher: Could we demonstrate what you said about astronomy through the spiral movements of plants? Is there some means of proving that through plants?

Dr. Steiner: What means would you need? Plants themselves are that means. You need only connect the pistil to the movements of the Moon and the stigma to those of the Sun. As soon as you relate the pistil to the Moon’s movements and the stigma to those of the Sun, you will get the rest. You will find in the spiral movements of the plant an imitation of the relative relationship between the movements of the Sun and the movements of the Moon. You can then continue. It is complicated and you will need to construct it. At first, the pistil appears not to move. It moves inwardly in the spiral. You must turn these around, since that is relative. The pistil belongs to the line of the stem, and the stigma to the spiral movement. However, because it is so difficult to describe further, I think it is something you could not use in school. This is a question of further development of understanding.

A teacher: Can we derive the spiral movements of the Sun and the Earth from astronomically known facts?

Dr. Steiner: Why not? Just as you can teach people today about the Copernican theory. The whole thing is based upon the joke made concerning the three Copernican laws, when they teach only the first two and leave out the third. If you bring into consideration the third, then you will come to what I have spoken of, namely, that you will have a simple spiral around the Sun. Copernicus did that. You need only look at his third law. You need only take his book, De Revolutionibus Corporum Coelestium (On the orbits of heavenly bodies) and actually look at the three laws instead of only the first two. People take only the first two, but they do not coincide with the movements we actually see. Then people add to it Bessel’s so-called corrective functions. People don’t see the stars as Copernicus described them. You need to turn the telescope, but people turn it according to Bessel’s functions. If you exclude those functions, you will get what is right.

Today, you can’t do that, though, because you would be called crazy. It is really child’s play to learn it and to call what is taught today nonsense. You need only to throw out Bessel’s functions and take Copernicus’s third law into account.

A teacher: Couldn’t that be published?

Dr. Steiner: Johannes Schlaf began that by taking a point on Jupiter that did not coincide with the course of the Copernican system. People attacked him and said he was crazy.

There is nothing anyone can do against such brute force. If we can achieve the goals of the Cultural Commission, then we will have some free room. Things are worse than people think when a professor in Tübingen can make “true character” out of “commodity character.” The public simply refuses to recognize that our entire school system is corrupt. That recognition is something that must become common, that we must do away with our universities and the higher schools must go. We now must replace them with something very different. That is a real foundation.

It is impossible to do anything with those people. I spoke in Dresden at the college. I also spoke at the Dresden Schopenhauer Society. Afterward, the professors there just talked nonsense. They could not understand one single idea. One stood up and said that he had to state what the differences were between Schopenhauer’s philosophy and anthroposophy. I said I found that unnecessary. Anthroposophy has the same relationship to philosophy as the crown of a tree to its roots, and the difference between the root and the crown of a tree is obvious. Someone can come along and say he finds it necessary to state that there is a difference between the root and the crown, and I have nothing to say other than that. These people can’t keep any thoughts straight. Modern philosophy is all nonsense. In much of what it brings, there is some truth, but there is so much nonsense connected with it that, in the end, only nonsense results. You know of Richert’s “Theory of Value,” don’t you? The small amount that exists as the good core of philosophy at a university, you can find discussed in my book Riddles of Philosophy.

The thing with the “true character” reminds me of something else. I have found people in the Society who don’t know what a union is. As I have often said, such things occur. If we can work objectively in the Cultural Commission, then we could replace all of these terrible goings on with reason, and everything would be better. Then we could also teach astronomy reasonably. But now we are unable to do anything against that brute force. In the Cultural Commission, we can do what should have been done from the beginning, namely, undertake the cultural program and work toward bringing the whole school system under control. We created the Waldorf School as an example, but it can do nothing to counteract brute force. The Cultural Commission would have the task of reforming the entire system of education. If we only had ten million marks, we could extend the Waldorf School. That these ten million marks are missing is only a “small hindrance.”

It is very important to me that you do not allow the children’s behavior and such to upset you. You should not imagine that you will have angels in the school. You will be unable to do many things because you lack the school supplies you need. In spite of that, we want to strictly adhere to what we have set out to do and not allow ourselves to be deterred from doing it as well as possible in order to achieve our goals.

It is, therefore, very important that in practice you separate what is possible to do under the current circumstances from what will give you the strength to prevail. We must hold to our belief that we can achieve our ideals. You can do it, only it will not be immediately visible.

Zweite Konferenz

Rudolf Steiner kam am 24. September aus Dresden zurück nach Stuttgart und besuchte am nächsten Morgen die Schüler bei der Arbeit in den acht Klassen. Zehn Tage war in beengten Räumlichkeiten unterrichtet worden; für Lehrer und Schüler war alles neu: der Ort, der Unterricht und der Tagesablauf. Die Klassen hatten im Durchschnitt 32 Schüler.

Am 30. September reiste Rudolf Steiner zusammen mit Marie Steiner weiter nach Dornach.

Themen [der 2. und 3, Konferenz]: Temperamente berücksichtigen zur Bewältigung großer Klassen. Professionelle Verschwiegenheit der Lehrer. Nachhilfestunden. Der Geschichtsunterricht. Zur Geologie. Die Morgensprüche. Der Grundriss für den freien christlichen Religionsunterricht. Über die Evolution der menschlichen Gestalt. Über Elternabende.

Bemerkungen: Die Lehrer überhäuften Steiner mit Fragen und Alltagssorgen des Unterrichts. Es war schwierig für sie, das Können und vor allem das Nichtkönnen der Kinder richtig einzuschätzen. Daher kam es zu vielen pädagogischen Fragen, die die Unerfahrenheit der Kollegen zeigen.

Zwischen den pädagogischen Fragen und Sorgen kam es schon in dieser Konferenz zu einem Dialog der eigenen Art, indem die Kollegen Steiner gleichsam herausforderten, mit Fragen zur Geologie, Astronomie, Geschichte und Botanik. Steiner zeigte sich als überragender Kenner aller angeschlagenen Themen, ein Beispiel freier republikanischer Unterredungen.

Zum Schluss lenkte Steiner das Gespräch zurück zum Tagesgeschäft und bat die Lehrer, sich nicht von «Ungezogenheit und dergleichen» abschrecken zu lassen. «Sie dürfen nicht die Vorstellung haben, dass sie Engel in die Schule kriegen.» Wie sich zeigen sollte, waren das prophetische Worte.

Auch wenn Steiner nicht in Stuttgart war, hielten die Lehrer Konferenzen ab, um den Schulalltag zu ordnen. In unveröffentlichten Notizen von Stockmeyer wird festgehalten, dass der versetzte Hauptunterricht nicht im ursprünglichen Maße durchgeführt werden musste; es waren dank zweier Reservezimmer doch genügend Räumlichkeiten vorhanden. In diesen Notizen wird auch festgehalten, dass die Fachstunden von 60 auf 50 Minuten heruntergesetzt wurden. Auch in einer solchen Konferenz war kurzerhand beschlossen worden, den übernächsten Tag schulfrei zu geben, da Steiner die Schule besuchen würde. (Notiz vom 23.09.1919)

Beiden Ausführungen zu den Elternabenden muss bedacht werden, dass die Mehrheit der Eltern zu der Arbeiterschaft der Waldorf-Astoria-Zigarettenfabrik gehörte. Es waren mehrheitlich «proletarische» Elternhäuser: Von den 253 eingeschulten Kindern stammten 143 aus den Familien der Belegschaft der Zigarettenfabrik.

Vor seiner Abreise legte Rudolf Steiner den Lehrern ans Herz, immer den Kontakt zu den Schülern zu pflegen, dass «der Lehrer mit den Schülern eine richtige Einheit bildet».

RUDOLF STEINER: Meine lieben Freunde! Heute wird es sich darum handeln, dass Sie die in den letzten zehn Tagen gesammelten Erfahrungen vorbringen und wir das Nötige besprechen.

KARL STOCKMEYER berichtet: Wir haben den Unterricht am 16. September angefangen mit einer kurzen Ansprache an die Schüler durch Herrn Molt, und es zeigte sich dabei gleich, dass der Stundenplan nicht ganz so aufgestellt werden konnte, wie es hier verabredet wurde, weil verschiedene Klassen zusammengelegt wurden. Dann ergab sich noch eine andere Notwendigkeit der Abweichung vom Stundenplan dadurch, dass die [evangelischen und katholischen] Religionslehrer zu den von uns festgesetzten Stunden nicht Zeit haben.

Der eigentliche Klassenunterricht bleibt aber auf den Vormittag gelegt, daran wollte ich nicht rütteln.

Dann hat sich die Notwendigkeit ergeben, in den Unterricht von 8-10 eine kleine Pause von fünf Minuten einzuschieben.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das kann gemacht werden. Aber was in der Zeit geschieht, muss im freien Ermessen des Lehrers stehen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Es ist versucht worden, ganz ohne Glocke auszukommen. Aber um am Schluss der Pause die Kinder wieder zusammenzurufen, muss doch eine Glocke angebracht werden, die besonders draußen hörbar ist.

Beim Sprachunterricht in den oberen Klassen stellte sich heraus, dass bei einzelnen Kindern noch gar keine Sprachkenntnisse vorhanden sind. Infolgedessen müssen am Anfang statt eineinhalb Stunden nun drei Stunden französischer und [drei Stunden] englischer Unterricht erteilt werden. Auch müsste ein Anfängerkurs gegeben werden und einer für die Fortgeschrittenen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Was unterrichten Sie in der 8. Klasse?

KARL STOCKMEYER: Mathematisches. Da in der 8. Klasse vom Buchstabenrechnen noch nichts gewusst wird, auch das Zinsrechnen noch nicht ausgebildet ist, habe ich mit Zinsrechnung in einer Art repetierender Weise angefangen und das so weit geführt, dass ich jetzt zu Diskont- und Wechselrechnung übergehen will.

Der Unterricht in der 7. und 8. Klasse wurde damals von zwei Klassenlehrern in der Weise gegeben, dass die beiden Lehrer miteinander abwechselten und der eine in beiden Klassen die humanistischen, der andere die realistischen [die naturwissenschaftlichen] Fächer unterrichtete.

RUDOLF STEINER: Sie [die beiden Lehrer der 7. und 8. Klasse] müssen sich eben fortlaufend miteinander verständigen, dass immer, wenn ein Lehrer oder [eine] Lehrerin die Klasse verlässt, ein gewisser Abschluss vorhanden ist. Wenn er dann in die Klasse zurückkommt, muss wiederholt werden.

Ist es Ihnen in den paar Tagen schon gelungen, genau zu wissen, wie viel die Schüler schon können?

KARL STOCKMEYER: Das konnte ich ungefähr schon feststellen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Bei Ihrer beschränkten Schülerzahl ist dies ja wohl möglich gewesen, aber die anderen werden es wohl nicht gekonnt haben. Man kann durchaus daran festhalten, dass Sie vielleicht ungefähr im Mittel acht Tage nehmen zum Wechseln, aber es muss dann speziell so eingerichtet werden, dass ein Kapitel abgeschlossen ist.

RUDOLF TREICHLER: Ich habe gefunden, dass in der 7. Klasse die Geschichtskenntnisse sehr verschieden sind.

RUDOLF STEINER: Sie werden wahrscheinlich in so etwas wie in der Geschichte in jeder Klasse von vorne anfangen müssen, denn eine ordentliche Geschichte wird keiner kennen. Die Kinder werden sich vielleicht das Landläufige angeeignet haben, aber eine ordentliche Geschichte, wie wir sie hier angedeutet haben, werden Sie bei niemand finden. Sie werden sie in jeder Klasse von vorne anfangen müssen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Wäre es angängig, den sogenannten freien Religionsunterricht zusammen zu haben mit einem evangelischen oder anderen konfessionellen Unterricht? Die Eltern konnten sich nicht entscheiden, ob sie den freien Religionsunterricht allein oder ob sie katholischen oder evangelischen [für ihre Kinder] geben lassen wollten. Sie wollten zum Teil die Möglichkeit haben, dass die Kinder beides mitnehmen. Viele Eltern haben auf den Fragebogen geschrieben: «beides». Viele Eltern wollten eben für die Tanten und Onkel nicht auf den Konfirmationsunterricht verzichten.

RUDOLF STEINER: Da dürfen wir nicht nachgeben; entweder - oder. Wir werden über die Frage später noch extra sprechen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Wir wollen versuchen, die beiden Religionsstunden auf die gleiche Stunde zu verlegen.

Nun ist noch eine Sache zu besprechen, die durch Herrn Molt schon eine gewisse Entscheidung gefunden hat als rein wirtschaftliche Frage. Wir hatten uns die Frage vorgelegt, ob es angängig wäre, dass die Schüler, die Schulgeld bezahlen, [auch] ihre Bücher bezahlen müssen. [Für die Kinder aus der Waldorf-Astoria-Fabrik haben wir ja Lehrmittelfreiheit.] Es könnte vorkommen, dass Kinder nebeneinander sitzen, das eine hat ein Buch, von dem es weiß: Es muss es wieder abgeben, das andere darf es behalten. Das ist etwas, was die Klassengegensätze betont.

RUDOLF STEINER: In dieser Form kann es nicht gemacht werden, dass die Kinder die Bücher kaufen und behalten. Es kann nur so gemacht werden, dass man für die [Eltern], die das Schulgeld bezahlen, dieses Schulgeld um die Lehrmittelpreise erhöht; es im Übrigen aber so hält wie mit den anderen Kindern. Also die Bücher müssen zurückgegeben werden wie bei den anderen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Wäre die Lehrmittelfreiheit auch auszudehnen auf Hefte und andere Dinge? Hier in Stuttgart ist das Usus geworden. Weniger erwünscht wäre es, wenn die Kinder Atlanten und Zirkel von der Schule gestellt bekommen. Das müssen wohl die Schüler anschaffen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Es würde natürlich das Beste sein bezüglich der Hefte und Ähnlichem, wenn für jede Klasse ein Vorrat angeschafft würde, und die Kinder gezwungen wären, wenn sie ein Heft ausgeschrieben haben, zum Lehrer zu kommen, um ein neues zu bekommen, damit Rechnung getragen werden könnte dem Umstand, dass das eine Kind mehr Hefte braucht als das andere. Es müsste also ein Vorrat von Heften vorhanden sein, und die Hefte nach Bedarf von dem Lehrer den Kindern gegeben werden.

Für Zirkel und dergleichen, da reißen natürlich auch Unsitten ein, wenn man es bloß in den Willen der Eltern oder der Kinder stellt, was sie sich kaufen oder nicht kaufen sollen. [Diejenigen], die mehr Geld haben, die kaufen dann bessere Sachen. Das ist auch eine Kalamität. Es wäre schon vielleicht nicht schlecht, wenn man es auch da so machen würde, dass das ganze Handwerkzeug der Schule gehört und die Kinder es nur zum Benützen bekommen.

Für den Atlas würde ich etwas anderes vorschlagen: dass eine Art Fonds gestiftet würde für solche Dinge und dass die Atlanten, die während des Jahres gebraucht werden, ebenso behandelt werden wie die anderen Lehrmittel. Dagegen sollte beim Abgang von der Schule jedes Kind einen Atlas bekommen. Das wäre außerdem eine sehr schöne Sache, wenn die Kinder beim Abgang das eine oder andere bekommen würden. Vielleicht könnte man diese Dinge sogar als Prämie für Fleiß geben: ein größeres, schöneres Buch dem, der mehr geleistet hat; ein kleineres dem, der weniger geleistet hat; und dem, der faul war, vielleicht nur eine Landkarte. Das ist etwas, was man tun könnte; es darf nur nicht zu weit führen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Wie sollen wir es handhaben mit den Büchern für den [konfessionellen] Religionsunterricht? Die Pfarrer sind in Nöten. Sie sagen: Bisher gab es Lehrmittelfreiheit auch für den religiösen Unterricht. Nach der neuen Verfassung wird es, wenigstens voraussichtlich, nicht mehr so sein, weil die Gelder nicht mehr vom Staat oder von der Gemeinde in Anspruch genommen werden können. Dieselbe Frage ist hier bei uns. Herr Molt hat entschieden, dass die Kinder die Bücher für den Religionsunterricht selber anschaffen müssen und dass auch der Unterricht des Religionslehrers selbst bezahlt werden muss. Das müsste geteilt werden unter die Kinder.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ich habe nichts dagegen, dass es so gemacht wird. Ich würde nur meinen, dass wir zunächst für dieses Jahr, damit alles ohne Reibung abläuft, uns erkundigen sollten, wie es andere Schulen machen. In der Zukunft werden wir schon zu einem eigenen Modus kommen, aber in diesem Jahr sollten wir es so machen wie die anderen Schulen. Wir müssen uns nach den öffentlichen Schulen richten. Wenn diese noch nicht verlangen, dass die Religionsbücher bezahlt werden und der Unterricht bezahlt wird, dann müssen wir auch warten, bis die es verlangen.

EMIL MOLT: Das ist heute alles frei.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das würde uns schon viel helfen, wenn wir sagen würden, wir machen es genauso wie die anderen öffentlichen Schulen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Es wird ein großer Unterschied bestehen zwischen Volks- und höheren Schulen. Wir müssen uns wohl nach den höheren Schulen richten?

RUDOLF Steiner: Nein, die Volksschule kommt für uns in Betracht.

EMIL MOLT: Es ist noch nichts geschehen, wir können noch alles so machen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ja, ich würde es machen nach dem Usus der Volksschule. Denn die sozialistische Regierung wird zunächst nichts tun, sondern alles beim Alten lassen. Sie wird Gesetze machen, aber alles beim Alten lassen.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Es wurde als eine Notwendigkeit empfunden, doch vielleicht eine Art Klassenbuch zu führen, damit die Klassen- und Fachlehrer besser Fühlung miteinander nehmen können. Es würde in freier Weise darin eingetragen, was gemacht worden ist. Natürlich nicht so, wie es bisher bei Klassenbüchern üblich war, sondern nur so, dass die einzelnen Lehrer sich über die Arbeit der anderen Lehrer ein wenig orientieren können.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ja, schreibt man etwas Ordentliches hinein, so braucht man Zeit. Das ist dann die Zeit, die zu den Allotrias der Kinder führt. In der Zeit, in der man als Lehrer mit den Kindern zusammen ist, sollte man nie irgendetwas anderes machen. Ich meine also, man ist nicht im Klassenzimmer drinnen, wenn man eine Tätigkeit ausübt, die sich nicht auf die Kinder bezieht. Wenn man das Zimmer betritt, ist man mit den Kindern, bis man weggeht, und man sollte ihnen nicht einen Augenblick Veranlassung geben, etwa durch Eintragung ins Klassenbuch oder dergleichen, untereinander zu schwätzen und abgezogen zu werden.

Viel besser ist es, diese Fragen unter sich zu erledigen. Wir setzen ja voraus, dass die Klassenlehrer keine Händel kriegen und sich sehr lieb haben und sich mündlich besprechen. Wer mit einer Klasse zu tun hat, bespricht sich mit den anderen, die auch damit zu tun haben. Und was sich die Einzelnen aufschreiben wollen, das machen sie außerhalb des Unterrichts. Nichts, gar nichts irgendwie machen in den Unterrichtsstunden, was vom unmittelbaren Verkehr mit den Kindern abzieht.

RUDOLF TREICHLER: Vielleicht kann man das in der Pause machen?

RUDOLF STEINER: Wozu ist es denn nötig, immer einzutragen? Erstens muss es eingetragen werden, zweitens muss es der andere lesen. Das ist ein Zeitaufwand, der verloren geht für den Verkehr mit den Schülern.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Wäre auch davon abzusehen, dass man einträgt, welche Schüler fehlen? Sollte man das auch nur im eigenen Tagebuch eintragen?

RUDOLF STEINER: Das ist ja eigentlich auch etwas, was man nicht braucht.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Nur für den Fall, dass ein längeres Fehlen eintritt, müsste man sich erkundigen, was los ist.

RUDOLF Steiner: Das kann bei einer nicht allzu großen Klasse auch mündlich abgemacht werden im Verkehr mit den Schülern. Man kann ja fragen, wer fehlt, und es sich dann eintragen ins eigene Notizbüchelchen. Das ist etwas, was man tun kann. Es wird ja sonst in den Schulen in die Zeugnisse eingetragen, wie viel ein Kind gefehlt hat, aber wir brauchen dafür kein Klassenbuch.

KARL. STOCKMEYER: Es erwies sich als notwendig, weil gerade die Kastanien auf den Bäumen reifen, den Schülern das Klettern auf die Bäume zu verbieten, damit kein Schaden entsteht durch Herunterfallen. Da mussten wir schon manchmal mit Verboten anfangen, aber wir sind uns immer bewusst, dass solche Verbote möglichst beschränkt werden müssen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Es ist sehr notwendig, dass wir uns darüber klar sind, dass wir in die Schule herein nicht lauter Engel bekommen. Das darf uns in keinem Falle hindern, unseren Ideen und unseren Idealen nachzugehen. Diese Dinge dürfen uns nicht dazu führen, auch nur zu sagen: Wir können nicht erreichen, was wir uns vorgenommen haben. Wir müssen immer klar vor uns haben auf der einen Seite, dass wir das, was in den Intentionen liegt, die wir im Kursus durchgeführt haben und auch sonst, verfolgen. Wie viel wir davon nicht erreichen, ist eine andere Frage; die müssen wir für sich behandeln und von Zeit zu Zeit genau besprechen. Heute ist noch zu kurze Zeit vergangen. Sie werden nur sagen können, wie stark die Rangenhaftigkeit zum Ausbruch gekommen ist.

Aber eines möchte ich Sie doch bitten, dass Sie es recht berücksichtigen. Das wäre das, dass wir als Lehrerschaft selbst - was die anderen machen durch die Kinder, das ist eine Sache für sich -, dass wir als Lehrerschaft versuchen, möglichst nicht unsere Schulangelegenheiten in die Öffentlichkeit hinauszutragen. Ich bin jetzt erst [seit] Stunden wieder da, aber ich habe schon so viel Geschwätz gehört über die Art, wie die Kinder behandelt werden, wer eine Ohrfeige gekriegt hat und so weiter; es geht schon ins Grenzenlose, dieses Geschwätz durch die Leute hindurch, dass es mir schrecklich war. Nicht wahr, wir brauchen uns nicht zu kümmern, wenn es durch alle möglichen unrichtigen Fugen herauskommt. Da sind wir harthäutig dagegen; aber tragen wir nur ja nicht selber dazu bei. Schweigen wir über alles das, was wir handhaben in der Schule. Halten wir uns an eine Art Schulgeheimnis. Reden wir nicht zu den Außenstehenden, außer zu den Eltern, die mit Fragen zu uns kommen, und da wiederum immer nur über die eigenen Kinder, das nicht zu Geschwätzen Veranlassung gegeben wird. Es gibt Leute, die reden aus Sensationslust und mit Wollust über solche Dinge. Das ist Gift für unsere ganze Unternehmung, wenn sie in dieser Weise in Klatsch übergeht. Das ist ja leider besonders in Stuttgart, dass viel in anthroposophischen Kreisen geklatscht wird. Das ist auch, was uns viel schadet, dieser Klatsch, der mir in widerwärtiger Weise schon entgegengetreten ist, und der von uns Lehrern nicht in irgendeiner Weise unterstützt werden darf.

KARL STOCKMEYER: Es sind einzelne Fälle zu besprechen, wo es vielleicht nötig sein wird, Kinder in niederere Klassen zurückzuversetzen. [Oder soll man empfehlen, diesen Kindern Nachhilfestunden geben zu lassen?]

RUDOLF STEINER: Das [Zurückversetzen] ist natürlich bei niedrigeren Klassen schwieriger; bei höheren wird es sich leichter machen lassen. In den ersten zwei Klassen sollte man möglichst nicht zurückversetzen.

Es werden einzelne Fälle besprochen.

RUDOLF STEINER: Nachhilfestunden sind technisch nie zu empfehlen. Nur in den Fällen, wo die Eltern selbst [an uns] herankommen, wenn sie von schlechten Erfolgen hören, kann man ihnen zu Nachhilfestunden raten. Wir selber als Lehrer werden nicht Nachhilfestunden geben. Das tun wir nicht. Da würde es dann noch besser sein, ein Kind herunterzuschieben in eine andere Klasse.

HANNAH Lang bespricht einen Fall, wo es lange dauert, bis der Schüler die Antwort herausbringt; die Antwort wird aber immer erwartet, auch wenn es lange dauert.

RUDOLF STEINER: Ja, cs ist wichtig, dass jedes Kind das herausbringt, das es machen soll.

HERTHA KOEGEL spricht über zwei Kinder in der 4. Klasse, die beschränkt sind.

RUDOLF Steiner: Diese Kinder müssen ganz [nach vorn] in die Nähe des Lehrers gesetzt werden, [unbeschadet des Temperaments], damit sie jeden Augenblick im Auge behalten werden.

[Rabiate Kinder kann man dadurch bei der Stange halten, dass man sie an die Ecken setzt oder ganz vorne oder ganz hinten hin, damit sie weniger Nachbarn haben, keine Vorder- und Hintermänner.]

DR. LUDWIG NOLL: Manchmal sehen Kinder nicht richtig. Eine Augenuntersuchung würde das ergeben. Ich kenne Kinder, die aus dem Grunde zurückgeblieben sind, weil sie weitsichtig waren und man [das] nicht beachtete.

RUDOLF STEINER: Das muss der aufmerksame Lehrer auch sehen, wo bei den Kindern Organfehler vorliegen [wie Kurzsichtigkeit oder Schwerhörigkeit]. Es ist schwierig, auf alles hin ärztliche Untersuchungen anzustellen. Nur wenn der Lehrer es angibt, sollte eine solche stattfinden.

Durch die schulärztlichen Untersuchungen, wie sie an den Schulen üblich sind, kommen wir zu stark in das Sachverständigensystem hinein. Wir wollen jetzt lieber von einem Schularzt absehen, da ja Herr Dr. Noll nicht hier sein wird; das würde etwas anderes sein. Jeder fremde Arzt würde uns Schwierigkeiten bereiten. Der Arzt sollte selbstverständlich der Berater der Lehrer sein, und der Lehrer sich vertrauensvoll an ihn wenden können, wenn er etwas bei seinen Kindern bemerkt.