The Renewal of Education

GA 301

10 May 1920, Basel

XIII. Children's Play

We have already seen that teaching history is beneficial only for developing children at about the age of twelve. Considering history is a kind of preparation for the period of life that begins with sexual maturity, that is, at about the age of fourteen or fifteen. Only at that time can human beings gain the capacity for independent reasoning. A capacity for reasoning, not simply intellectual reasoning, but a comprehensive reasoning in all directions, can only develop after puberty. With the passing of puberty, the supersensible aspect of human nature that carries the capacity of reason is born out of the remainder of human nature. You can call this what you like. In my books I have called it the astral body,but the name is unimportant. As I have said, it is not through intellectual judgment that this becomes noticeable, but through judgment in its broadest sense. You will perhaps be surprised that what I will now describe I also include in the realm of judgment. If we were to do a thorough study of psychology here, you would also see that what I have to say can also be proven psychologically.

When we attempt to have a child who is not yet past puberty recite something according to his or her own taste, we are harming the developmental forces within human nature. These forces will be harmed if an attempt is made to use them before the completion of puberty; they should only be used later. Independent judgments of taste are only possible after puberty. If a child before the age of fourteen or fifteen is to recite something, she should do so on the basis of what an accepted authority standing next to her has provided. This means she should find the way in which the authority has spoken pleasing. She should not be led astray to emphasize or not emphasize certain words, to form the rhythm out of what she thinks is pleasing, but instead she should be guided by the taste of the accepted authority. We should not attempt to guide that intimate area of the child’s life away from accepted authority before the completion of puberty. Notice that I always say “accepted authority” because I certainly do not mean a forced or blind authority. What I am saying is based upon the objective observation that from the change of teeth until puberty, a child has a desire to have an authority standing alongside her. The child demands this, longs for it, and we need to support this longing, which arises out of her individuality.

When you look at such things in a comprehensive way, you will see that in my outline of education here I have always taken the entire development of the human being into account. For this reason I have said that between the ages of seven and fourteen, we should only teach children what can be used in a fruitful way throughout life. We need to see how one stage of life affects another. In a moment I will give an example that speaks to this point. When a child is long past school age, has perhaps long since reached adulthood, this is when we can see what school has made of the child and what it has not. This is visible not only in a general abstract way but also in a very concrete way.

Let us look at children’s play from this perspective, particularly the kind of play that occurs in the youngest children from birth until the change of teeth. Of course, the play of such children is in one respect based upon their desire to imitate. Children do what they see adults doing, only they do it differently. They play in such a way that their activities lie far from the goals and utility that adults connect with certain activities. Children’s play only imitates the form of adult activities, not the material content. The usefulness in and connection to everyday life are left out. Children perceive a kind of satisfaction in activities that are closely related to those of adults. We can look into this further and ask what is occurring here. If we want to study what is represented by play activities and through that study recognize true human nature so that we can have a practical effect upon it, then we must continuously review the individual activities of the child, including those that are transferred to the physical organs and, in a certain sense, form them. That is not so easy. Nevertheless the study of children’s play in the widest sense is extraordinarily important for education.

We need only recall what a person who set the tone for culture once said: “A human being is only a human being so long as he or she plays; and a human being plays so long as he or she is a whole human being.” Schiller1 wrote these words in a letter after he had read some sections of Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister. To Schiller, free play and the forces of the soul as they are artistically developed in Wilhelm Meister appeared to be something that could only be compared with an adult form of children’s play. This formed the basis of Schiller’s Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man. He wrote them from the perspective that adults are never fully human when carrying out the activities of normal life. He believed that either we follow the necessities of what our senses require of us, in which case we are subject to a certain compulsion, or we follow logical necessity, in which case we are no longer free. Schiller thought that we are free only when we are artistically creative. This is certainly understandable from an artist such as Schiller; however, it is one-sided since in regard to freedom of the soul there is certainly much which occurs inwardly,in much the same way that Schiller understood freedom. Nevertheless the kind of life that Schiller imagined for the artist is arranged so that the human being experiences the spiritual as though it were natural and necessary, and the sense-perceptible as though it were spiritual. This is certainly the case when perceiving something artistic and in the creation of art.

When creating art, we create with the material world, but we do not create something that is useful. We create in the way the idea demands of us, if I may state it that way, but we do not create abstract ideas according to logical necessity. In the creation of art, we are in the same situation as we are when we are hungry or thirsty. We are subject to a very personal necessity. Schiller found that it is possible for people to achieve something of that sort in life, but children have this naturally through play. Here in a certain sense they live in the world of adults, through only to the extent that world satisfies the child’s own individuality. The child lives in creation, but what is created serves nothing.

Schiller’s perspective, from the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century, can be used as a basis for further development. The psychological significance of play is not so easy to find. We need to ask if the particular kind of play that children engage in before the change of teeth has some significance for the entirety of human life. We can, as I said, analyze it in the way that Schiller tried to do under the influence of Goethe’s adult childishness. We could also, however, compare this kind of play with other human activities. We could, for example, compare children’s play before the change of teeth with dreaming, where we most certainly will find some important analogies. However, those analogies are simply related to the course of the child’s play, to the connection of the activities to one another in play. In just the same way that children put things together in play—whatever those might be—not with external things but with thoughts, we put pictures together in dreams. This may not be true of all dreams, but it is certainly so in a very large class of them. In dreaming, we remain in a certain sense children throughout our entire lives.

Nevertheless we can only achieve a genuine understanding if we do not simply dwell upon this comparison of play with dreams. Instead we should also ask when in the life of the human being something occurs that allows those forces that are developed in early children’s play until the change of teeth, which can be fruitful for the entirety of external human life. In other words, when do we actually reap the fruits of children’s play? Usually people think we need to seek the fruits of young children’s play in the period of life that immediately follows, but spiritual science shows how life passes in a rhythmical series of repetitions. In a plant, leaves develop from a seed; from the leaves, the bud and flower petals emerge, and so forth. Only afterwards do we have a seed again; that is, the repetition occurs only after an intervening development. It is the same in human life.

From many points of view we could understand human life as though each period were affected only by the one preceding, but this is not the case. If we observe without prejudice, we will find that the actual fruits of those activities that occur in early childhood play become apparent only at the age of twenty. What we gain in play from birth until the change of teeth, what children experience in a dreamy way, are forces of the still-unborn spirituality of the human being, which is still not yet absorbed into, or perhaps more properly said, reabsorbed into the human body.

We can state this differently. I have already discussed how the same forces that act organically upon the human being until the change of teeth become, when the teeth are born, an independent imaginative or thinking capacity, so that in a certain sense something is removed from the physical body. On the other hand, what is active within a child through play and has no connection with life and contains no usefulness is something that is not yet fully connected with the human body. Thus a child has an activity of the soul that is active within the body until the change of teeth and then becomes apparent as a capacity for forming concepts that can be remembered.

The child also has a spiritual-soul activity that in a certain sense still hovers in an etheric way over the child. It is active in play in much the same way that dreams are active throughout the child’s entire life. In children, however, this activity occurs not simply in dreams, it occurs also in play, which develops in external reality. What thus develops in external reality subsides in a certain sense. In just the same way that the seed-forming forces of a plant subside in the leaf and flower petal and only reappear in the fruit, what a child uses in play also only reappears at about the age of twenty-one or twenty-two, as independent reasoning gathering experiences in life.

I would like to ask you to try to genuinely seek this connection. Look at children and try to understand what is individual in their play: try to understand the individuality of children playing freely until the change of teeth, and then form pictures of their individualities. Assume that what you notice in their play will become apparent in their independent reasoning after the age of twenty. This means the various kinds of human beings differ in their independent reasoning after the age of twenty in the just the same way that children differ in their play before the change of teeth.

If you recognize the full truth of this thought, you will be overcome by an unbounded feeling of responsibility in regard to teaching. You will realize that what you do with a child forms the human being beyond the age of twenty. You will see that you will need to understand the entirety of life, not simply the life of children, if you want to create a proper education.

Playing activity from the change of teeth until puberty is something else again. (Of course, things are not so rigidly separated, but if we want to understand something for use in practical life, we must separate things.) Those who observe without prejudice will find that the play activity of a child until the age of seven has an individual character. As a player, the child is, in a certain sense, a kind of hermit. The child plays for itself alone. Certainly children want some help, but they are terribly egotistical and want the help only for themselves. With the change of teeth, play takes on a more social aspect. With some individual exceptions, children now want to play more with one another. The child ceases to be a hermit in his play; he wants to play with other children and tobe something in play. I am not sure if Switzerland can be included in this, but in more military countries the boys particularly like to play soldier. Mostly they want to be at least a general, and thus a social element is introduced to the children’s play.

What occurs as the social element in play from the change of teeth until puberty is a preparation for the next period of life. In this next period, with the completion of puberty, independent reasoning arises. At that time human beings no longer subject themselves to authority; they form their own judgments and confront others as individuals. This same element appears in the previous period of life in play; it appears in something that is not connected with external social life, but in play. What occurs in the previous period of life, namely, social play, is the prelude to tearing yourself away from authority. We can therefore conclude that children’s play until the age of seven actually enters the body only at the age of twenty-one or twenty-two, when we gain an independence in our understanding and ability to judge experiences. On the other hand, what is prepared through play between the ages of seven and puberty appears at an earlier developmental stage in life, namely, during the period from puberty until about the age of twenty-one. This is a direct continuation. It is very interesting to notice that we have properly guided play during our first childhood years to thank for the capacities that we later have for understanding and experiencing life. In contrast, for what appears during our lazy or rebellious years we can thank the period from the change of teeth until puberty. Thus the connections in the course of human life overlap.

These overlapping connections have a fundamental significance of which psychology is unaware. What we today call psychology has existed only since the eighteenth century. Previously, quite different concepts existed about human beings and the human soul. Psychology developed during the period in which materialistic spirit and thought arose. Thus in spite of all significant beginnings, psychology was unable to develop a proper science of the soul, a science that was in accord with reality and took into account the whole of human life. Although I have tried hard, I have to admit that I have been able to find some of these insights only in Herbart’s psychology. Herbart’s psychology is very penetrating; it attempts to discover a certain form of the soul by beginning with the basic elements of the soul’s life. There are many beautiful things in Herbart’s psychology. Nevertheless we need to look at the rather unusual views it has produced in his followers. I once knew a very good follower of Herbart, Robert Zimmermann, an aesthete who also wrote a kind of educational philosophy in his book on psychology for high-school students. Herbart once referred to him as a Kantian from 1828. In his description of psychology as a student of Herbart, he discusses the following problem:

If I am hungry, I do not actually attempt to obtain the food that would satisfy my hunger. Instead, my goal is that the idea of hunger will cease and be replaced by the idea of being full. My concern is actually with ideas. There exists an idea that must arise contrary to inhibitions, and which must work against those inhibitions. Food is actually only a means of moving from the idea of hunger to the idea of being full.

Those who look at the reality of human nature, not simply in a materialistic sense, but also with an eye toward the spiritual, will see that this kind of view is somewhat one-sidedly rationalistic and intellectual. It is necessary to move beyond this one-sided intellectualism and comprehend the entire human being psychologically. In so doing, education can gain much from psychology that otherwise would not be apparent. We should consider what we do in teaching not simply to be the right thing for the child, but rather to be something living that can transform itself. As we have seen, there are many connections of the sort I have presented. We need to assume that what we teach children in elementary school until puberty will reappear in a quite different form from the age of fifteen until twenty-one or twenty-two.

The elementary-school teacher is extremely important for the high-school teacher or the university teacher—in a sense even more important, since the university teacher can achieve nothing if the elementary-school teacher has not sent the child forth with properly formed strengths. It is very important to work with these connected periods of life. If we do, we will see that real beginning points can be found only through spiritual science.

For instance, people define things too much. As far as possible, we should avoid giving children any definitions. Definitions take a firm grasp of the soul and remain static throughout life, thus making life into something dead. We should teach in such a way that what we provide to the child’s soul remains alive. Suppose someone as a child of around nine or ten years of age learns a concept, for instance, at the age of nine, the concept of a lion, or, at the age of eleven or twelve, that of Greek culture. Very good; the child learns it. But these concepts should not remain as they are. A person at the age of thirty should not be able to say she has such-and-such a concept of lions and that is what she learned in school, or that she has such-and-such a concept of Greek culture and that was what she learned in school. This is something we need to overcome. Just as other parts of ourselves grow, the things we receive from the teacher should also grow; they should be something living. We should learn concepts about lions or Greek culture that will not be the same when we are in our thirties or forties as they were when we were in school.

We should learn concepts that are so living that they are transformed throughout our lives. To do so, we need to characterize rather than define. In connection with the formation of concepts, we need to imitate what we can do with painting or even photography. In such cases, we can place ourselves to one side and give one aspect, or we can move to another side and give a different aspect, and so forth. Only after we have photographed a tree from many sides do we have a proper picture of it. Through definitions, we gain too strong an idea that we have something.

We should attempt to work with thoughts and concepts as we would with a camera. We should bring forth the feeling within the child that we are only characterizing something from various perspectives; we are not defining it. Definitions exist only so that we can, in a sense, begin with them and so that the child can communicate understandably with the teacher. That is the basic reason for definitions. That may sound somewhat radical, but it is so. Life does not love definitions. In private, human beings should always have the feeling that, through incorrect definitions, they have arrived at dogmas. It is very important for teachers to know that. Instead of saying, for instance, that two objects cannot be in the same place at the same time, and that is what we call impermeable, the way we consciously define impermeability and then seek things to illustrate this concept, we should instead say that objects are impermeable because they cannot be at the same place at the same time. We should not make hypotheses into dogmas. We only have the right to say that we call objects impermeable when they cannot be at the same place at the same time. We need to remain conscious of the formative forces of our souls and should not awaken the concept of a triangle in the external world before the child has recognized a triangle inwardly.

That we should characterize and not define is connected with recognizing that the fruits of those things that occur during one period of human life will be recognized perhaps only very much later. Thus we should give children living concepts and feelings rather than dead ones. We should try to present geometry, for example, in as lively a way as possible. A few days ago I spoke about arithmetic. I want to speak before the end of the course tomorrow about working with fractions and so forth, but now I would like to add a few remarks about geometry. These remarks are connected with a question I was asked and also with what I have just presented.

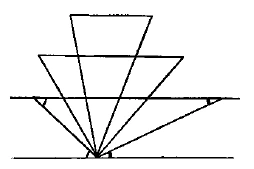

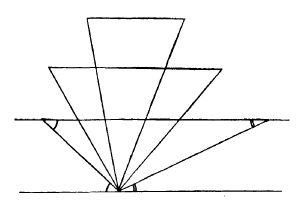

Geometry can be seen as something that can slowly be brought from a static state into a living one. In actuality, we are speaking of something quite general when we say that the sum of the angles of a triangle is 180°. That is true for all triangles, but can we imagine a triangle? In our modern way of educating, we do not always attempt to teach children a flexible concept of a triangle. It would be good, however, if we teach our children a flexible concept of a triangle, not simply a dead concept. We should not have them simply draw a triangle, which is always a special case. Instead we could say that here I have a line. I can divide the angle of 180° into three parts. That can be done in an endless number of ways. Each time I have divided the angle, I can go on to form a triangle, so that I show the child how an angle that occurs here then occurs here in the triangle. When I transfer the angles in this way, I will have such a triangle. Thus in moving from three fan-shaped angles lying next to one another, I can form numerous triangles and those triangles thus become flexible in the imagination. Clearly these triangles have the characteristic that the sum of their angles is 180° since they arose by dividing a 180° angle. It is good to awaken the idea of a triangle of a child in this way, so that an inner flexibility remains and so that they do not gain the idea of a static triangle, but rather that of a flexible shape, one that could just as well be acute as obtuse, or it could be a right triangle (see diagram).

Imagine how transparent the whole concept of triangles would be if I began with such inwardly flexible concepts, then developed triangles from them. We can use the same method to develop a genuine and concrete feeling for space in children. If in this way we have taught children the concept of flexibility in figures on a plane, the entire mental configuration of the child will achieve such flexibility that it is then easy to go on to three-dimensional elements—for instance, how one object moves past another behind it, forward or backward. By presenting how an object moves forward or backward past another object, we present the first element that can be used in developing a feeling for space. If we, for example, present how it is in real life—namely how one person ceases to be visible when he or she moves behind an object or how the object becomes no longer visible when the person moves in front of it—we can go on to develop a feeling for space that has an inner liveliness to it. The feeling for three-dimensional space remains abstract and dead when it is presented only as perspectives. The children can gain that lively feeling for space if, for instance, we tell a short story.

This morning at nine o’clock I came across two people. They were sitting someplace on a bench. This afternoon at three, I came by again and the same two people were sitting on the same bench. Nothing had changed.

Certainly as long as I only consider the situation at nine in the morning and three in the afternoon, nothing had changed. However, if I go into it more and speak with these people, then perhaps I would discover that after I had left in the morning, one person remained, but the other stood up and went away. Though he was gone for three hours,he then returned and sat down again alongside the other. He had done something and was perhaps tired after six hours. I cannot recognize the actual situation only in connection with space, that is, if I think only of the external situation and do not look further into the inner, to the more important situation.

We cannot make judgments even about the spatial relationships between beings if we do not go into inner relationships. We can avoid bitter illusions in regard to cause and effect only if we go into those inner relationships. The following might occur: A man is walking along the bank of a river and comes across a stone. He stumbles over the stone and falls into the river. After a time he is pulled out. Suppose that nothing more is done than to report the objective facts: Mr. So-and-So has drowned. But perhaps that is not even true. Perhaps the man did not drown, but instead stumbled because at that point he had a heart attack and was already dead before he fell into the water. He fell into the water because he was dead. This is an actual case that was once looked into and shows how necessary it is to proceed from external circumstances into the more inner aspects.

In the same way if we are to make judgments about the spatial relationship of one being to another, we need to go into the inner aspects of those beings. When properly grasped in a living way, it enables us to develop a spatial feeling in children so that we can use movements for the development of a feeling for space. We can do that by having the children run in different figures, or having them observe how people move in front or behind when passing one another.

It is particularly important to make sure that what is observed in this way is also retained. This is especially significant for the development of a feeling for space. If I cast a shadow from different objects upon the surface of other objects, I can show how the shadow changes. If children are capable of understanding why, under specific circumstances, the shadow of a sphere has the shape of an ellipse—and this is certainly something that can be understood by a child at the age of nine—this capacity to place themselves in such spatial relationships has a tremendously important effect upon their capacity to imagine and upon the flexibility of their imaginations.

For that reason we should certainly see that it is necessary to develop a feeling for space in school. If we ask ourselves what children do when they are drawing up until the change of teeth, we will discover that they are in fact developing experience that then becomes mature understanding around the age of twenty. That understanding develops out of the changing forms, so the child plays by drawing; at the same time, however, that drawing tells something. We can understand children’s drawings if we recognize that they reflect what the child wants to express.

Let us look at children’s drawings. Before the ages of seven or eight or sometimes even nine, children do not have a proper feeling for space. That comes only later when other forces slowly begin to affect the child’s development. Until the age of seven, what affects the child’s functioning later becomes imagination. Until puberty, it is the will that mostly affects the child and which, as I mentioned earlier, is dammed up and becomes apparent through boys’ change of voice. The will is capable of developing spatial feeling. Through everything that I have just said, that is, through the development of a spatial feeling through movement games and by observing what occurs when shadows are formed—namely, through what arises through movement and is then held fast—all such things that develop the will give people a much better understanding than simply through an intellectual presentation, even though that understanding may be somewhat playful, an understanding with a desire to tell a story.

Now, at the end of this lecture, I would like to show you the drawings of a six-year-old boy whose father, I should mention, is a painter so that you can see them in connection with what I just said. Please notice how extraordinarily talkative this six-year-old boy is through what he creates. I might even say that he has in fact created a very specific language here, a language that expresses just what he wants to tell. Many of these pictures,which we could refer to as expressionist, are simply his way of telling stories that were read to him, or which he heard in some other way. Many of the pictures are, as you can see, wonderfully expressive. Take a look at this king and queen. These are things that show how children at this age tell stories. If we understand how children speak at this age—something that is so wonderfully represented here because the boy is already drawing with colored pencils—and if we look at all the details, we will find that these drawings represent the child’s being in much the way that I described to you earlier. We need to take the change that occurred with the change of teeth into consideration if we are to understand how we can develop a feeling for space.

13. Das Kindliche Spiel

Ich werde diese letzten Vorträge so gestalten, wie es sich ergibt durch diese oder jene Fragestellung, die an mich entweder schriftlich oder mündlich ergangen ist; ich werde auch versuchen, noch einiges ergänzend zu dem einen oder anderen hinzuzufügen, das ich schon vorgebracht habe. Zunächst möchte ich bemerken, daß jene Befruchtung, die für die pädagogische Kunst von seiten der Geisteswissenschaft ausgehen könnte, unter vielem anderen darin bestehen soll, daß die Erziehungskunst durch Geisteswissenschaft wirklich in die Lage kommt, sachgemäß den Blick auf die ganze Entwickelung des Menschen zu lenken.

Wir haben ja gesehen, wie so etwas wieGeschichtsbetrachtung eigentlich erst gegen das 12. Jahr für den heranwachsenden Menschen fruchtbar gemacht werden kann. Denn in der Geschichtsbetrachtung liegt schon eine Art Vorbereitung für das Lebensalter, das erst mit der Geschlechtsreife, also mit dem 14. oder 15. Jahr beginnt. Da beginnt beim Menschen im Grund erst die Fähigkeit, aus dem Innern heraus zu urteilen. Urteilsvermögen, nicht bloß intellektualistisches Urteilsvermögen, sondern umfassendes Urteilsvermögen nach allen Richtungen hin, kann sich erst nach der Geschlechtsreife entwickeln. Erst mit der Geschlechtsreife wird jenes übersinnliche Glied der menschlichen Wesenheit, das Träger der Urteilskraft ist, aus der übrigen menschlichen Natur heraus geboren. Man nenne dieses Glied, wie man will. In meinen Büchern habe ich es astralischer Leib genannt, aber auf den Namen kommt es nicht an. Ich sagte, nicht allein beim intellektualistischen Beurteilen merkt man dies, sondern bei jeder Art von Urteil im weitesten Sinne. Sie werden vielleicht etwas erstaunt darüber sein, daß ich das, was ich jetzt bezeichnen will, auch unter die Sphäre des Urteils fasse. Allein würden wir hier eine ausführliche Psychologie treiben können, so würde man das, was ich sage, auch psychologisch nachweisen können. Wenn wir zum Beispiel den Versuch machen, das Kind vor der Geschlechtsreife aus seinem eigenen Geschmacksurteil heraus rezitieren zu lassen, so verdirbt man Entwickelungskräfte der menschlichen Natur, die im Grunde erst später in Anspruch genommen werden sollen und die eben verdorben werden, wenn sie vor der Geschlechtsreife in Anspruch genommen werden. Auch das Fällen eines selbständigen Geschmacksurteils ist erst nach der Geschlechtsreife möglich. Wenn ein Kind vor dem 14., 15. Jahr zum Deklamieren angehalten werden soll, so geschehe es in Anlehnung an denjenigen, der eben als selbstverständliche Autorität neben dem Kinde steht. Das heißt, das Kind soll Gefallen finden an der Art und Weise, wie der andere rezitiert. Nicht soll das Kind angeleitet werden, selber aus seinem Geschmacksurteil heraus etwas so zu betonen, so etwas nicht zu betonen, den Rhythmus so oder so zu gestalten, sondern das Kind soll auf Autorität hin auch in bezug auf die Geschmacksführung sich leiten lassen. Gerade das Gebiet des intimen Kindeslebens soll man ja nicht vor der Geschlechtsreife aus dem Folgen der selbstverständlichen Autorität herauszuführen suchen. Ich sage immer »selbstverständliche Autorität«, weil ich durchaus nicht eine aufgezwungene oder gar eine blinde Autorität meine, sondern ich gehe ja von dem aus, was sich einer unbefangenen Beobachtung ergibt: Das Kind will vom Zahnwechsel bis zur Geschlechtsreife neben sich die Autorität haben. Es verlangt das. Es hat Sehnsucht danach. Und dieser Sehnsucht, die aus der Individualität des Kindes kommt, soll man entgegenkommen.

Wenn Sie solche Dinge im umfassenden Sinne ins Auge fassen, dann werden Sie sehen, daß in der Darstellung, in welcher ich hier versucht habe, einiges skizzenhaft über pädagogische Kunst zu sagen, immer Rücksicht auf die Gesamtentwickelung des Menschen genommen wird. Darum wird gesagt, man soll zwischen dem 7. und 14. Jahr nichts anderes in das Kind hineinbringen, als was für das ganze Leben dann fruchtbar sein kann. Man muß eben sehen, wie ein Lebensalter auf das andere wirkt. Ich werde gleich ein sprechendes Beispiel dafür geben. Das Kind mag längst aus der Schule fort sein, ist vielleicht längst erwachsen, da zeigt sich erst, was wir in der Schule aus ihm gemacht haben und was nicht. Aber es zeigt sich nicht nur in einer allgemeinen, abstrakten, es zeigt sich in einer ganz konkreten Weise.

Betrachten wir von diesem Gesichtspunkte aus einmal das kindliche Spiel, und zwar gerade jenes Spiel, das beim allerjüngsten Kind zwischen der Geburt und dem Zahnwechsel auftritt. Dieses Spiel beruht ja selbstverständlich nach der einen Seite hin auf dem Nachahmungstrieb. Die Kinder machen das nach, was sie bei den Erwachsenen sehen; aber sie machen es anders; sie machen es vor allen Dingen so, daß sie weit entfernt sind von dem Zweck und der Nützlichkeit, die der Erwachsene mit gewissen Handlungen verbinden muß. Das Spiel wird nur der formalen Seite nach eine Nachahmung der Erwachsenen-Tätigkeit darstellen, nicht der materiellen Seite nach. Die Nützlichkeit, das zweckmäßige Sichhineinstellen in das Leben bleibt fort. Das Kind empfindet eine Befriedigung an der Tätigkeit, die der Betätigung der Erwachsenen nahe verwandt ist. Nun kann man untersuchen; was ist denn da eigentlich tätig? Wenn man das, was in der Spielbetätigung zum Vorschein kommt, studieren will und dabei die wahre Wesenheit des Menschen so erkennen will, daß man praktisch an der Entwickelung des Menschen sich betätigen kann, so muß man fortwährend die einzelnen Tätigkeiten der menschlichen Seele ins Auge fassen, auch diejenigen, welche sich dann auf die leiblichen Organe übertragen, sich gewissermaßen auf sie ausgießen. So einfach ist das nicht. Das Studium der Spielbetätigung im ausgedehntesten Maße wäre jedoch für die pädagogische Kunst schon ganz außerordentlich wichtig. Nun hängt diese Spielbetätigung mit Mannigfaltigem zusammen. Da sollte man sich doch erinnern, daß einmal von einem tonangebenden Geistesmenschen das Wort geprägt worden ist: Der Mensch ist nur so lange ganz Mensch, als er spielt, und der Mensch spielt nur, so lange er ganz Mensch ist. Dieses Wort hat Schiller in einem Brief geprägt, als er Goethes »Wilhelm Meister« in gewissen Partien gelesen hatte. Das freie Spiel mit den Seelenkräften, wie es sich entfaltet in der künstlerischen Gestaltung des »Wilhelm Meister«, erschien Schiller als etwas, das er nur vergleichen konnte mit einem Erwachsenwordensein des kindlichen Spiels. Und im Grunde schrieb Schiller seine Briefe: »Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen« ganz aus dieser Gesinnung heraus. Schiller schrieb ja aus der Gesinnung heraus, daß man als erwachsener Mensch mit der Betätigung, die man im gewöhnlichen Leben zu üben hat, eigentlich nie ganz Mensch ist. Entweder folgt man, meint Schiller, der sinnlichen Notdurft, demjenigen, was die Sinne fordern; dann steht man unter einem gewissen Zwang. Oder man folgt der logischen Notwendigkeit, die man von der Vernunft vorgeschrieben erhält, dann folgt man der Vernunftnotwendigkeit und ist wieder kein freierMensch. Frei, meint Schiller, ist man eigentlich nur im künstlerischen Schaffen und im künstlerischen Sinnen. Das ist gewiß begreiflich bei einem Künstler wie Schiller, aber es ist einseitig, da es in bezug auf die Erfassung der Freiheit der Seele viel menschliches Erleben gibt, das ebenso nur innerlich verläuft, wie dasjenige, was Schiller unter Freiheit versteht. Aber die Lebensform, in der Schiller den Künstler befindlich denkt, ist tatsächlich so, daß der Mensch Geistiges erlebt, wie wenn es natürlich und notwendig wäre, und wiederum Sinnliches so, wie wenn es schon Geistiges wäre. Das ist ja gewiß beim künstlerischen Genießen und auch beim künstlerischen Schaffen der Fall. Man schafft im sinnlichen Material, aber man schafft nicht nach Nützlichkeit, nicht nach äußeren Zweckmäßigkeitsprinzipien. Man schafft so, wie es die Idee will -— wenn man das Wort im weitesten Sinne gebraucht -, aber man schafft auch nicht in abstrakten Ideen nach logischen Notwendigkeiten, sondern beim künstlerischen Schaffen ist man so dabei, wie man bei Hunger und Durst dabei ist. Es ist eine ganz persönliche Notwendigkeit. Schiller fand, daß der Mensch sich so etwas erringen kann im Leben, daß aber das Kind auf naturgemäße Weise dieses Spiel hat, in welchem es gewissermaßen in der Welt der Erwachsenen lebt, aber nur so, daß es seine Individualität befriedigt, daß es sich auslebt im Geschaffenen, ohne daß das Geschaffene zu irgend etwas dient.

Nun, das war eine Betrachtung, die angestellt worden ist im Beginne des 19. Jahrhunderts und am Ende sogar des 18. Jahrhunderts von Schiller und die einen anregen kann, die Sache weiter zu verfolgen. In der Tat, die psychologische Bedeutung des Spieles, sie ist nicht so ganz einfach zu finden. Man muß ja sich sagen: Hat nun die besondere Art von Spieltätigkeit, die das Kind ausübt vor dem Zahnwechsel, eine Bedeutung für das ganze Menschenleben? Man kann, wie gesagt, sie so analysieren, wie das Schiller versucht hat unter der Anregung von Goethes gewissermaßen Erwachsenen-Kindlichkeit. Man kann aber diese Spieltätigkeit auch mit einer anderen Betätigung der menschlichen Wesenheit vergleichen. Man kann diese Spieltätigkeit des Kindes vor dem Zahnwechsel mit der Traumtätigkeit vergleichen. Da wird man sehr wohl gewisse bedeutsame Analogien finden. Nur just beziehen sich diese Analogien bloß auf den Verlauf, auf den Zusammenhang desjenigen, was das Kind in der Spielbetätigung tut. So wie das Kind im Spiel die Dinge zusammenstellt — was es auch immer zusammenistelle -, so stellt man, wenn auch nicht mit äußeren Dingen, sondern nur mit Gedanken, mit Bildern, im Traume die Bilder zusammen, wenn auch nicht in allen Träumen, aber in einer sehr wesentlichen Klasse von Träumen. Man bleibt im Träumen tatsächlich das ganze Leben hindurch in einem gewissen Sinne Kind. Man kann aber, um die Sache nun zu einem wirklichen Real-Erkennen zu bringen, dabei nicht stehenbleiben, das Spiel mit dem Traume zu vergleichen, sondern man muß sich fragen: Wann tritt denn im Leben des Menschen etwas ein, wodurch diejenigen Kräfte, die in diesem ersten kindlichen Spiel bis vor dem Zahnwechsel entwickelt werden, für das ganze äußere Menschenleben fruchtbar werden, wann hat man eigentlich die Früchte des kindlichen Spiels? Da meint man gewöhnlich, man müsse in der unmittelbar darauffolgenden Lebensepoche diese Früchte des kindlichen Spieles suchen, und das ist es eben, was Geisteswissenschaft erst zeigen soll, wie in einer Art von rhythmischen Wiederholungen das Leben abläuft. So wie man einen Pflanzenkeim hat, aus dem sich Blätter entwickeln in mannigfaltigen Gestalten, erst Kelchblätter, dann Blütenblätter und so weiter, und dann kommt erst wiederum der Keim, wie da dazwischen etwas liegt und die Wiederholung des Früheren nach einer Zwischenperiode auftritt, so ist es tatsächlich auch im Menschenleben.

Man ist durch die mannigfaltigste Betrachtungsweise dahin gebracht worden, das Menschenleben lediglich so aufzufassen, als wenn jedes folgende Zeitalter die Wirkung des vorangehenden wäre. Das ist nicht der Fall. Gibt man sich einer unbefangenen Beobachtung hin, so findet man, daß die eigentlichen Früchte derjenigen Lebensbetätigung, die im ersten Spiel auftritt, erst in den Zwanzigerjahren herauskommen. Was wir uns im Spiel von der Geburt bis zum Zahnwechsel erwerben, was da traumhaft vom Kinde dargelebt wird, das sind Kräfte der jetzt noch ungeborenen Geistigkeit des Menschen, der noch nicht in den Körper hinein absorbierten, oder resorbierten, wenn Sie besser wollen, Geistigkeit des Menschen. Das ist so: Ich habe Ihnen auseinandergesetzt, wie dieselben Kräfte, die an dem Menschen bis zum Zahnwechsel hin organisch arbeiten, dann selbständig sind, wenn sie die Zähne geboren haben, als Vorstellungs-, als Denktätigkeit; da wird gewissermaßen aus dem Leiblichen etwas herausgezogen. Das, was das Kind betätigt im Spiel, was auch noch nicht zusammenhängt mit dem Leben, dem keine Nützlichkeit innewohnt, das ist dagegen etwas, was noch nicht mit dem Leib zusammengewachsen ist; so daß das Kind eine seelische Betätigung hat, die im Leibe arbeitet bis zum Zahnwechsel und dann zum Vorscheine kommt als Kraft zur Bildung von Begriffen, die dann erinnert werden können. Auf der anderen Seite hat es eine geistig-seelische Betätigung, die gewissermaßen noch leicht ätherisch über das Kind hinschwebt, die sich imSpiel so betätigt, wie sich im ganzen Leben die Träume betätigen. Aber diese Tätigkeit wird beim Kinde eben nicht bloß im Traum, sie wird am Spiel, also doch an einer äußeren Realität, entwickelt. Was da an dieser äußeren Realität entwickelt wird, das tritt gewissermaßen zurück. Wie die keimbildende Kraft in der Pflanze im Blatt und im Blütenblatt zurücktritt und erst wiederum in der Frucht erscheint, so erscheint dasjenige, was da im Kinde angewendet und aufgewendet wird, erst wiederum etwa vom 21. oder 22. Jahre beim Menschen als der nun selbständig im Leben Erfahrungen sammelnde Verstand. Und da möchte ich Sie bitten: Versuchen Sie diesen Zusammenhang wirklich aufzusuchen, gehen Sie wirklich gewissenhaft Kinder durch, versuchen Sie das Individuelle ihres Spieles zu begreifen, überhaupt das Individuelle der freien spielerischen Betätigung der Kinder zu begreifen bis zum Zahnwechsel hin, und machen Sie sich Bilder von den Individualitäten der Kinder, und setzen Sie zunächst hypothetisch voraus: die individuelle Gestaltung, die im Spiel bis zum Zahnwechsel bemerkbar ist, die tritt in irgendeiner Weise im besonderen Charakter des selbständigen Urteilens des Menschen nach dem 20. Jahre wieder auf; das heißt, die Menschentypen nach dem 20. Jahre sind verschieden in bezug auf ihr selbständiges Urteilen, so wie die Kinder verschieden sind beim Spiel vor dem Zahnwechsel.

Denkt man so etwas aus der vollen Wirklichkeit heraus, dann bekommt man tatsächlich ein, ich möchte sagen, unbegrenztes Verantwortlichkeitsgefühl gegenüber dem Erziehen und auch dem Unterrichten; denn man kommt dazu, sich zu sagen: Was du jetzt mit dem Kinde tust, das formt den Menschen noch über die Zwanzigerjahre hinaus. Man sieht aus dem, daß man das ganze Leben, nicht bloß das Kindesleben kennen muß, wenn man eine richtige Erziehungskunst aufbauen will.

Die weitere spielende Tätigkeit von dem Zahnwechsel bis zur Geschlechtsreife ist etwas anderes. Gewiß, die Dinge sind nicht streng voneinander geschieden, will man aber etwas Ordentliches erkennen gerade für das praktische Leben, so muß man die Dinge ordentlich scheiden. Wer beobachten kann, wird finden, daß die spielende Tätigkeit des Kindes bis zum 7. Jahre etwas von einem individuellen Charakter hat. Das Kind ist gewissermaßen als Spielender eine Art Einsiedler. Es spielt für sich. Gewiß, es will auch Hilfe haben, aber dann ist es ein furchtbarer Egoist, es will eben auch allein die Hilfe haben. Ein geselliges Leben für das Spiel tritt mit dem Zahnwechsel ein. Die Kinder wollen dann mehr untereinander spielen. Das tritt mit dem Zahnwechsel ein, wenigstens ist das der typische Fall, obwohl es gerade einzelne Ausnahmen gibt. Da hört das Kind auf, der Einsiedler im Spiel zu sein; es will mit andern Kindern seine Spiele machen und etwas im Spiel bedeuten. Dieses Im-Spiel-etwas-bedeuten-Wollen, das ist es, was insbesondere zwischen dem Zahnwechsel und der Geschlechtsreife auftritt. In mulitaristischen Ländern - ich weiß nicht, ob die Schweiz auch zu ihnen gehört, das will ich nicht entscheiden -, in militaristischen Ländern machen die Knaben insbesondere die Soldatenspiele, die ja gesellige Spiele sind, bei denen die Knaben »etwas sein« wollen. Die meisten wollen mindestens General sein bei diesen Spielen; ein geselliges Element tritt ein in die kindlichen Spiele. Dabei bleibt der Charakter des Spiels gewahrt, indem das, was da im kindlichen Spiel geübt wird, sich nicht nach dem Zweckmäßigkeitsprinzip in das soziale Leben hineinstellt. Aber das Eigentümliche ist, daß man das, was als Geselliges auftritt, im Spiel vom Zahnwechsel bis zur Geschlechtsreife eigentlich wie das vorbereitende Element für das nächste Lebensalter findet. Es ist sehr eigentümlich, wie im nächsten Lebensalter mit der Geschlechtsreife das selbständige Urteil auftritt, wo der Mensch sich der Autorität entreißt, sein eigenes Urteil bildet, als einzelner Mensch dem andern gegenübertritt. Vorbereitend tritt im kindlichen Spiel, eben nicht ins äußere soziale Leben eingegliedert, sondern eben nur in der Spieltätigkeit, dieses gleiche Element gerade in der vorhergehenden Lebensepoche auf. Das, was also in der vorhergehenden Lebensepoche auftritt im kindlichen, geselligen Spiel, ist das vorläufige Sichlosreißen von der Autorität. Wir müssen daher sagen: Das Spiel gibt dem Kinde bis zum 7. Jahre, bis zum Zahnwechsel, etwas, was verleiblicht erst im 21. oder 22. Jahre ins Menschenleben eintritt, womit erworben wird die selbständige Individualität des Verstandes- und Erfahrungsurteils und so weiter. Dasjenige aber, was vom 7. Jahre bis zur Geschlechtsreife im Spiele sich vorbereitet, das tritt früher in der Entwickelung im Lebenslaufe auf, das tritt dann von der Geschlechtsreife bis zum 21. Jahre auf. Das ist ein Übergreifen. Es ist sehr interessant, darauf aufmerksam zu werden, daß wir das, was wir für unseren Verstand, für unsere Lebenserfahrung, für unsere gesellige Zeit als Fähigkeiten haben, den ersten Kinderjahren verdanken, wenn das Spiel ordentlich geleitet wird. Das hingegen, was in unseren Lümmel- oder Flegeljahren in die Erscheinung tritt, verdanken wir der Zeit von dem Zahnwechsel bis zur Geschlechtsreife. Da überschneiden sich also die Zusammenhänge in dem menschlichen Lebenslauf.

Solches Übergreifen von Zusammenhängen im menschlichen Lebenslauf ist von fundamentaler Bedeutung, und das ist etwas, was der Psychologie entgangen ist. Denn das, was wir heute Psychologie nennen, gibt es auch erst seit dem 18. Jahrhundert. Vorher hatte man ganz andere Begriffskonfigurationen über den Menschen und die Menschenseelen. Aber das entwickelte sich durchaus in dem Zeitalter, in dem schon der materialiistische Geist und das materialistischeDenken kamen, und daher konnte sich Psychologie trotz aller bedeutsamen Anfänge nicht so entwickeln, daß eine richtige Seelenwissenschaft entstanden wäre, die der Wirklichkeit gemäß mit dem ganzen Menschenleben rechnete. Ich muß gestehen, ich habe mir sehr, sehr viel Mühe gegeben, auch das Allerbeste, was nur zu finden ist, in der Herbartschen Psychologie zu entdecken. Die Herbartsche Psychologie ist scharfsinnig. Die Herbartsche Psychologie bemüht sich tatsächlich, aus elementaren Bestandteilen des Seelenlebens heraus auf eine gewisse Gestaltung der Seele hinzuarbeiten. Es ist außerordentlich viel Schönes in der Herbartschen Psychologie; allein man muß doch hinschauen darauf, was diese Herbartsche Psychologie bei guten Herbartianern für eigentümliche Ansichten hervorgerufen hat.

Ich kannte einen ganz hervorragenden Herbartianer sehr nahe, den Ästheten Robert Zimmermann, der auch eine »Philosophische Propädeutik« mit einer Psychologie für Gymnasiasten geschrieben hat und Herbart für das 19. Jahrhundert einen Kantianer von 1828 genannt hat. Der setzte in seiner psychologischen Schilderung als Herbart-Schüler tatsächlich das Folgende auseinander: Wenn ich Hunger habe, so strebe ich nicht danach, das Nahrungsmittel zu erhalten, welches den Hunger befriedigt, sondern eigentlich nur danach, daß die Vorstellung des Hungers aufhört und von der Vorstellung der Sättigung abgelöst wird. Ich habe es nur zu tun mit einer Bewegung von Vorstellungen. Es ist eine Vorstellung da, welche gegen Hemmungen aufkommen muß, die sich gegen Hemmungen heraufarbeiten muß. Und das Essen sei eigentlich nur ein Mittel, um übergehen zu können von der Vorstellung des Hungers zu der Vorstellung der Sättigung.

Wer nun die Wirklichkeit der menschlichen Natur nicht etwa im materialistischen Sinne, sondern gerade im spirituell-geistigen Sinne ins Auge fassen kann, der wird sehen, daß in dieser Art der Anschauung eben etwas einseitig Rationalistisches und Intellektualistisches steckt und daß es notwendig ist, daß wir über dieses einseitig Intellektuelle hinauskommen und den ganzen Menschen gerade psychologisch erfassen. Dann werden wir von der Psychologie aus gar manches für die pädagogische Kunst fordern müssen, was sonst für diese pädagogische Kunst nicht zum Vorschein kommen kann. Was wir in dem Menschen heranerziehen, heranunterrichten, dürfen wir nicht so betrachten, daß es für das Kind gerade richtig sein soll, sondern das soll ein Lebendiges sein, das sich umbilden kann. Denn wir sehen ja, es gibt solche Zusammenhänge, wie ich sie dargestellt habe. Man muß rechnen damit, daß man das, was man in der Volksschule heranbildet bis zur Geschlechtsreife, in einer ganz anderen Form vom 15. bis zum 21., 22. Jahre im Menschen aufgehen sieht.

Der Volksschullehrer ist für den Gymnasiallehrer oder für den Universitätslehrer unendlich wichtig, ja, er ist wichtiger, weil der Universitätslehrer gar nichts machen kann, wenn ihm der Volksschullehrer nicht richtig vorgebildete Kräfte hinaufschickt. Das ist tatsächlich von einer großen Bedeutung, daß man mit diesen zusammengehörigen Lebensabschnitten wirklich rechnet. Man wird dann sehen, daß reale Anhaltspunkte nur aus der Geisteswissenschaft heraus zu gewinnen sind.

Nun aber bedenken Sie, was alles in der Schule getrieben wird, weil man in Abhängigkeit lebt von gewissen Vorurteilen. Sicherlich, es ist schon manches aus gewissen Instinkten heraus besser geworden; es muß aber radikal besser werden — man definiert zum Beispiel noch zu viel. Man sollte, so viel es geht, vermeiden, vor den Kindern irgendwelche Definitionen zu geben. Definitionen legen immer die Seele fest, und ein Definitionsbegriff bleibt das Leben hindurch und macht das Leben zu etwas Totem. Wir sollen aber so erziehen, daß das, was wir in die kindliche Seele hineintragen, lebendig bleibt. Nehmen wir an, jemand bekommt als Kind im 9. Jahre oder im 11. Jahre von dem oder jenem einen Begriff, also im 9. Jahre, sagen wir, von einem Löwen, im 11. oder 12. Jahre von der griechischen Kultur. Schön, das bekommt es. Aber diese Begriffe sollen nicht so bleiben. Es sollte das gar nicht möglich sein im Leben, daß einer sagt mit 30 Jahren: Ich habe diesen oder jenen Begriff vom Löwen, den habe ich in der Schule gelernt. Ich habe diesen oder jenen Begriff vom Griechentum, das habe ich in der Schule gelernt. Das müßte eigentlich etwas werden, was überwunden wird. Geradeso wie das andere an uns wächst, so soll dasjenige, was uns der Lehrer gibt, auch wachsen, soll ein Lebendiges sein. Wir sollen solche Begriffe vom Löwen, solche Begriffe vom Griechentum bekommen, die durch sich selber im 30., 40. Jahre nicht mehr das sind, was sie gewesen sind in.der Schule, sondern die so lebendig sind, daß sie sich mit dem Leben umgestalten. Dazu müssen wir charakterisieren und nicht definieren. Wir müssen versuchen mit Bezug auf die Bildung der Begriffe, dasjenige nachzumachen, was wir beim Malen oder auch beim Photographieren tun können; da können wir uns nur auf eine Seite hinstellen und einen Aspekt geben oder auf die andere Seite hinstellen und einen anderen Aspekt geben und so weiter. Erst wenn wir von mehreren Seiten einen Baum photographiert haben, können wir eine Vorstellung davon gewinnen. Man ruft zu stark die Idee hervor: durch die Definition habe man etwas. Man sollte versuchen, auch mit Gedanken, mit Begriffen so zu arbeiten wie mit dem photographischen Apparat, und soll auch kein anderes Gefühl hervorrufen als dieses, daß man von verschiedenen Seiten her ein Wesen oder ein Ding charakterisiert, nicht definiert. Definitionen sind eigentlich nur dazu da, daß man sie, wenn man will, an den Anfang stellt, damit man in diesem einen Punkt sich mit dem Lehrer verstehen kann. Dazu sind Definitionen im Grunde da. Es ist etwas radikal gesprochen, aber im wesentlichen doch so. Das Leben liebt keine Definitionen. Und im Geheimen sollte der Mensch immer empfinden, wie er durch das falsche Definieren Postulate zu Dogmen macht. Das ist sehr wichtig, daß der Lehrer das weiß. Statt daß wir sagen: Zwei Wesen, die zu gleicher Zeit nicht an ein und demselben Orte sein können, nennen wir undurchdringlich — wobei wir bewußt den Begriff der Undurchdringlichkeit aufstellen und dann für diesen Begriff die Sache suchen -, statt daß wir so vorgehen, sagen wir: Körper sind undurchdringlich, weil sie nicht zu gleicher Zeit an ein und demselben Orte sein können. Wir dürfen nicht Postulate zu Dogmen machen, sondern wir haben nur ein Recht zu sagen: Wir nennen diejenigen Körper undurchdringlich, die nicht zu gleicher Zeit an einem und demselben Orte sein können. Wir müssen uns der bildenden Kraft unserer Seele bewußt bleiben und müssen in dem Kinde auch nicht die Vorstellung erwecken, daß es, bevor es innerlich das Dreieck erkannt hat, das Wesentliche vom Dreieck in der äußeren Welt begreifen kann.

Daß man charakterisieren soll und nicht definieren, hängt zusammen mit derErkenntnis, daß dasjenige, was in einem Menschenzeitalter auftritt, vielleicht erst in einem sehr fernen Zeitalter in seinen Früchten erkannt wird und daß man deshalb nicht tote, sondern lebendige Begriffe, lebendige Empfindungen dem Kinde übermitteln soll. Und so soll man auch versuchen, Geometrie zum Beispiel so lebendig als möglich zu gestalten. Ich habe vor einigen Tagen über das Rechnen gesprochen - über das Rechnen mit Brüchen und mit ähnlichem will ich dann, bevor morgen der Kursus zu Ende geht, einige Bemerkungen machen -, aber über das Geometrische möchte ich heute noch einiges anfügen, das sich ganz gut anschließt erstens an eine Frage, die mir gestellt worden ist, und zweitens an dasjenige, was ich eben jetzt ausgesprochen habe.

Das Geometrische wird von demjenigen, der selbst gewisse Erfahrungen mit der Geometrie gemacht hat, wirklich so empfunden werden können, daß es allmählich aus dem Ruhenden ins Lebendige hereingeholt werden sollte. Eigentlich reden wir doch von etwas sehr allgemeinem, wenn wir sagen: Die Winkelsumme eines Dreiecks ist 180 Grad. Das ist bei jedem Dreieck der Fall, nicht wahr. Können wir uns aber jedes Dreieck vorstellen? Wir werden nicht immer aus der heutigen Bildung heraus anstreben, unseren Kindern einen beweglichen Begriff des Dreiecks beizubringen; es wäre aber gut, wenn wir unsern Kindern einen beweglichen Begriff des Dreiecks beibrächten, nicht einen toten Begriff, nicht bloß ein Dreieck, das ja dann immer ein spezielles, individuelles Dreieck ist, hinzeichnen lassen, sondern ihnen sagen: Hier habe ich eine Linie. Ich bringe das dann so weit, daß ich auf irgendeine Weise - ich kann Ihnen natürlich nicht alle Einzelheiten in diesem kurzen Vortragskurse entwickeln — dem Kinde den Winkel von 180 Grad in drei Teile teile. Ich kann auf unendlich viele Weisen diesen Winkel in drei Teile teilen. Ich kann dann jedesmal, wenn ich diesen Winkel in drei Teile geteilt habe, zum Dreieck dadurch übergehen, daß ich dem Kinde zeige, wie der Winkel, der hier ist, hier auftritt; so werde ich, indem ich die Sache auf dieses übertrage, ein solches Dreieck bekommen. Indem ich übergehe von den drei fächerförmig nebeneinanderliegenden Winkeln, kann ich unzählige Dreiecke, die sich da bewegen, vorstellen, und diese unzähligen Dreiecke haben selbstverständlich die Eigenschaft, daß ihre Winkelsumme 180 Grad ist, denn sie entstehen ja aus der Teilung der 180 Grade der Winkelsumme. So ist es gut, in dem Kinde die Vorstellung des Dreiecks hervorzurufen, das eigentlich in innerer Beweglichkeit ist, so daß man gar nicht die Vorstellung bekommt eines ruhenden Dreiecks, sondern die Vorstellung eines bewegten Dreiecks, das ebensogut ein spitzwinkliges wie ein stumpfwinkliges, wie ein rechtwinkliges sein kann, weil ich gar nicht die Vorstellung des ruhenden Dreiecks fasse, sondern die Vorstellung des bewegten Dreiecks.

Denken Sie sich, wie durchsichtig die ganze Dreieckslehre würde, wenn ich von einem solchen innerlich bewegten Begriffe ausgehen würde, um das Dreieckmäßige zu entwickeln. Dies könnten wir dann auch sehr gut als Unterstützung benützen, wenn wir nun in dem Kinde eine ordentliche Raumempfindung, eine konkrete, eine wahre Raumempfindung heranbilden wollen. Wenn wir in dieser Weise den Begriff der Bewegung für die Ebenenfigur gebraucht haben, dann bekommt die ganze geistige Konfiguration des Kindes eine solche Beweglichkeit, daß ich dann leicht übergehen kann zu jenem perspektivischen Elemente: ein Körper geht an dem anderen vorn vorbei oder rückwärts vorbei. Dieses Übergehen, Vorwärts-Vorbeigehen, Rückwärts-Vorbeigehen, das kann das erste Element sein zum Hervorrufen einer entsprechenden Raumempfindung. Weiter: Wenn man lebensgemäß dieses Vorne- und Rückwärts-Vorbeigehen namentlich eines Menschen, das Unsichtbarwerden hinter einem Körper und das Unsichtbarmachen vor einem Körper erörtert hat, dann kann man dazu übergehen - es bleibt nämlich sonst doch abstrakt und tot, wenn es bloß ein perspektivisches Raumgefühl ist -—, das Raumgefühl innerlich lebendig werden zu lassen. Das bekommt man aber nur dadurch heraus, daß man zum Beispiel sagt: Sieh einmal, ich traf an einem bestimmten Orte morgens um 9 Uhr zwei Menschen; die saßen dort an dem Orte auf einer Bank. Nachmittags um 3 Uhr komme ich wieder hin, da sitzen wiederum die zwei Menschen auf der Bank - es hat sich nichts geändert. Gewiß, so lange ich den Tatbestand um 9 Uhr und um 3 Uhr betrachte, bloß äußerlich, so lange hat sich nichts geändert. Aber gehe ich ein auf das Innere, komme ich ins Gespräch mit dem einen Menschen und mit dem anderen Menschen, so mache ich vielleicht die Entdeckung, daß, nachdem ich weggegangen war, der eine sitzenblieb, der andere aber wegging. Der eine Mensch ist drei Stunden lang weggewesen und wiederum zurückgekommen, sitzt neben dem anderen dort, hat aber innerlich etwas durchgemacht, ist innerlich etwas ermüdet nach sechs Stunden. Den Tatbestand aber lerne ich nicht erkennen in seinem Zusammenhang nach dem Raum, wenn ich nur nach dem äußeren Tatbestand urteile, und nicht auf das Innere, Wesentliche eingehe.

Man kann selbst über das Räumliche, über die räumliche Beziehung zwischen den Wesen nicht urteilen, wenn man nicht auf das Innerliche eingeht. Nur wenn man auf dieses Innerliche eingeht, kann man vor den herbsten Illusionen in bezug auf Ursache und Wirkung bewahrt bleiben. Es passierte einmal folgendes: Ein Mann geht am Rande eines Flusses. An einer Stelle steht ein Stein. Der Mann stolpert über den Stein und verschwindet in den Wellen und wird nach einer gewissen Zeit herausgezogen. Nehmen wir an, es wird sonst nichts getan als der nüchterne Tatbestand aufgenommen; Der Mann so und so ist ertrunken. Vielleicht ist dies aber gar nicht wahr. Vielleicht ist der Mann nicht ertrunken, sondern er ist gestolpert, weil ihn auf der Stelle der Schlag getroffen hat, und er schon tot ins Wasser gefallen ist. Das InsWasser-Fallen war eine Folge des Todes. Es ist dies eine wahre Geschichte, die untersucht worden ist. Sie zeigt, wie notwendig es ist, vom Äußeren auf das Innere einzugehen.

So ist es auch notwendig, wenn man im Räumlichen das Verhältnis der Wesen zueinander beurteilen will, auf das Innere der Wesen einzugehen. Und das richtig, lebendig erfaßt, bringt uns dazu, das Raumgefühl in den Kindern dadurch zu entwickeln, daß wir tatsächlich das Bewegungsspiel selber zum Entwickeln des Raumgefühles verwenden, indem wir das Kind Figuren laufen lassen oder dergleichen oder indem wir das Kind beobachten lassen, wie Menschen hintereinander oder voreinander vorbeilaufen und dergleichen.

Dann aber ist es von ganz besonderer Wichtigkeit, nun wirklich aus dem, was auf diese Art beobachtet wird, zum Festhalten des Beobachteren überzugehen. Namentlich ist für die Entwickelung des Raumgefühles — das bezieht sich jetzt auf die Frage, die mir gestellt worden ist — von großer Bedeutung, wenn ich auf verschiedene gekrümmte Flächen durch Körper von verschiedener Krümmung Schatten werfen lasse und nun versuche, ein Verständnis für die besondere Konfiguration des Schattens hervorzurufen. Man kann geradezu behaupten: Wenn ein Kind imstande ist zu begreifen, warum eine Kugel unter gewissen Verhältnissen einen Ellipsenschatten wirft — das ist etwas, was vom Kind schon vom 9. Jahre ab erfaßt werden kann -, dann wirkt dieses Sichhineinversetzen in Flächenentstehungen im Raume auf die ganze innere Beweglichkeit des Empfindungs- und Vorstellungsvermögens des Kindes ungeheuer. Man sollte deshalb die Entwickelung des Raumgefühls in der Schule als etwas Nötiges ansehen. Wenn man sich nun frägt: Was tut das Kind bis zum Zahnwechsel hin, bis zum 7., 8. Jahre selbst, indem es spielerisch zeichnet? Es entwickelt tatsächlich das, was als Erfahrung, Verstand in den Zwanzigerjahren dann reif wird. Das entwickelt sich aus dem Fluktuieren der Gestalt, so daß das kindliche Zeichnen spielt, aber indem es spielt, erzählt das kindliche Zeichnen; und wir werden das kindliche Zeichnen besonders gut verstehen, wenn wir es so auffassen, daß es eine Wiedergabe ist von dem, was uns das Kind erzählen will. Es will sich aussprechen.

Schauen wir diese Zeichnungen des Kindes an. Das, was man ein richtiges Raumgefühl nennen könnte, haben die Kinder vor dem 7., 8. Jahre, selbst vor dem 9. Jahre gerade noch nicht. Dazu kommt es erst später, wenn sich allmählich die andere Kraft in die kindliche Entwickelung hineinfindet. Bis zum 7. Jahre arbeitet an der kindlichen Organisation das, was später Vorstellung wird; bis zur Geschlechtsreife arbeitet an der kindlichen Organisation der Wille, der dann, wie ich Ihnen gesagt habe, sich staut und in dem Knaben-Stimmeswandel eben zeigt, wie er in den Körper geschossen ist. Dieser Wille ist dazu geeignet, das Raumgefühl in sich zu entwickeln. So daß man durch all das, was ich jetzt gesagt habe, durch dieses Entwickeln eines Raumgefühls an Bewegungsspielen, durch die Anschauung dessen, was geschieht, wenn Schattenfiguren entstehen, namentlich durch das, was in der Bewegung entsteht und festgehalten wird, indem durch dieses alles der Wille entwickelt wird, der Mensch zu einem viel besseren Verständnis der Dinge gelangt als durch das Verstandesmäßige, selbst wenn es der spielerische kindliche Verstand ist, der flächenhaft sich ausdrückt, der erzählend sein will.

Nun möchte ich heute am Schluß der Stunde gerade in Anknüpfung an das Gesagte für diejenigen, die es sehen wollen, die kindlichen Zeichnungen eines sechsjährigen Knaben, der allerdings einen Maler-Illustrator zum Vater hat, hier auflegen. Ich bitte, sie ein wenig zu betrachten, um aufmerksam darauf zu werden, wie außerordentlich beredt dieser sechsjährige Knabe in dem, was er hier schafft, ich möchte sagen, sich in der Tat eine ganz individuelle Sprache schafft, eine ganz individuelle Schrift für das, was er erzählen will oder auch nacherzählen will. Manche von diesen Bildern, die man, wenn man will, richtig expressionistische Bilder nennen kann, sind einfache Nacherzählungen dessen, was dem Knaben vorgelesen worden ist, was er gehört hat und dergleichen; manches ist, wie Sie sehen werden, außerordentlich ausdrucksvoll, großartig ausdrucksvoll. So zum Beispiel weise ich Sie hin auf dasjenige, was Sie hier sehen werden als einen König und eine Königin. Das sind Dinge, die zeigen, wie erzählt wird in diesem Alter. Versteht man, wie in diesem Alter erzählt wird, was gerade hier so charakteristisch hervortritt, weil der Knabe schon mit Farbstiften zeichnet, und nimmt man das in allen Einzelheiten auf, so wird man finden, daß in der Tat diese Zeichnungen der Abdruck des kindlichen Wesens sind, wie ich es Ihnen bisher geschildert habe, und daß man diesen Umschwung, der mit dem Zahnwechsel auftritt, ins Auge fassen muß, wenn man verstehen will, wie man das Raumgefühl hervorzurufen hat.

13. Childlike Play

I will structure these final lectures according to the questions that have been put to me either in writing or verbally; I will also try to add a few things to supplement what I have already said. First of all, I would like to note that the enrichment that spiritual science could bring to the art of education should consist, among many other things, in enabling the art of education to truly direct its gaze appropriately toward the entire development of the human being.

We have seen how something like the study of history can only really be made fruitful for the growing human being around the age of 12. For the study of history already contains a kind of preparation for the age of life that only begins with sexual maturity, that is, at the age of 14 or 15. It is then that the human being begins to develop the ability to judge from within. Judgment, not merely intellectual judgment, but comprehensive judgment in all directions, can only develop after sexual maturity. Only with sexual maturity is that supersensible member of the human being, which is the bearer of judgment, born out of the rest of human nature. Call this member what you will. In my books, I have called it the astral body, but the name is not important. I said that this is not only noticeable in intellectual judgment, but in every kind of judgment in the broadest sense. You may be somewhat surprised that I also include what I am about to describe in the sphere of judgment. However, if we were able to engage in detailed psychology here, what I am saying could also be proven psychologically. If, for example, we attempt to have a child recite from its own taste judgment before reaching sexual maturity, we spoil the developmental powers of human nature, which should basically only be called upon later and which are spoiled if they are called upon before sexual maturity. Making an independent judgment of taste is also only possible after puberty. If a child is to be encouraged to recite before the age of 14 or 15, this should be done with the support of someone who is a natural authority figure for the child. This means that the child should enjoy the way the other person recites. The child should not be instructed to emphasize something or not to emphasize something based on their own taste, or to shape the rhythm in a certain way, but should instead be guided by authority in terms of taste. It is precisely the area of the child's intimate life that should not be led away from following natural authority before reaching sexual maturity. I always say “natural authority” because I do not mean an imposed or even blind authority, but rather I proceed from what is evident from unbiased observation: from the time they lose their baby teeth until puberty, children want to have authority beside them. They demand it. It longs for it. And this longing, which comes from the child's individuality, should be accommodated.

If you consider such things in a comprehensive sense, you will see that in the presentation in which I have attempted here to say something in outline about the art of education, consideration is always given to the overall development of the human being. That is why it is said that between the ages of 7 and 14, nothing should be instilled in the child that cannot be fruitful for their entire life. One must see how one age affects another. I will give a telling example of this in a moment. The child may have long since left school, may have long since grown up, and only then does it become apparent what we have made of them at school and what we have not. But this is not only evident in a general, abstract way; it is evident in a very concrete way.

Let us consider from this point of view the play of children, and specifically the play that occurs in the youngest children between birth and the change of teeth. This play is, of course, based on the one hand on the urge to imitate. Children imitate what they see adults doing, but they do it differently; above all, they do it in a way that is far removed from the purpose and usefulness that adults associate with certain actions. The play is only a formal imitation of adult activity, not a material one. The usefulness, the purposeful adaptation to life, remains absent. The child derives satisfaction from activities that are closely related to those of adults. Now we can examine what is actually at work here. If one wants to study what comes to light in play activity and thereby recognize the true essence of the human being in such a way that one can practically engage in the development of the human being, one must constantly consider the individual activities of the human soul, including those that are then transferred to the physical organs, pouring out onto them, so to speak. It is not that simple. However, studying play in its broadest sense would be extremely important for the art of education. Now, play is connected with many things. We should remember that a leading intellectual once coined the phrase: Man is only fully human as long as he plays, and man only plays as long as he is fully human. Schiller coined this phrase in a letter after reading certain parts of Goethe's “Wilhelm Meister.” The free play of the soul's powers, as it unfolds in the artistic creation of “Wilhelm Meister,” appeared to Schiller as something he could only compare to the maturation of childlike play. And basically, Schiller wrote his letters “On the Aesthetic Education of Man” entirely out of this conviction. Schiller wrote out of the conviction that as an adult, with the activities one has to perform in ordinary life, one is never truly human. Either, Schiller believes, one follows sensual needs, what the senses demand; then one is under a certain compulsion. Or one follows the logical necessity prescribed by reason, then one follows the necessity of reason and is again not a free person. According to Schiller, one is only truly free in artistic creation and artistic thinking. This is certainly understandable for an artist like Schiller, but it is one-sided, since there is much human experience in relation to the understanding of the freedom of the soul that takes place just as much internally as what Schiller understands by freedom. But the way of life in which Schiller thinks the artist exists is actually such that man experiences the spiritual as if it were natural and necessary, and in turn experiences the sensual as if it were already spiritual. This is certainly the case with artistic enjoyment and also with artistic creation. One creates in sensual material, but one does not create according to utility, according to external principles of expediency. One creates as the idea dictates—if one uses the word in the broadest sense—but one does not create in abstract ideas according to logical necessities; rather, in artistic creation, one is engaged in it as one is engaged in hunger and thirst. It is a very personal necessity. Schiller believed that human beings can achieve something like this in life, but that children naturally engage in this kind of play, in which they live, as it were, in the world of adults, but only in such a way that it satisfies their individuality, that they live themselves out in what they have created, without what they have created serving any purpose.

Now, that was an observation made at the beginning of the 19th century and even at the end of the 18th century by Schiller, and it may inspire some to pursue the matter further. In fact, the psychological significance of play is not so easy to find. One must ask oneself: Does the particular kind of play that children engage in before they lose their baby teeth have any significance for their entire lives? As mentioned, one can analyze it as Schiller attempted to do, inspired by Goethe's adult childishness, so to speak. But one can also compare this play activity with another activity of the human being. One can compare the play activity of the child before the change of teeth with the activity of dreaming. There one will certainly find certain significant analogies. Only these analogies relate solely to the course, to the connection of what the child does in its play activity. Just as the child puts things together in play — whatever it may be putting together — so too, in dreams, one puts images together, albeit not with external things, but only with thoughts and images, and although not in all dreams, but in a very significant class of dreams. In dreams, one actually remains a child in a certain sense throughout one's entire life. However, in order to bring the matter to a real understanding, one cannot stop at comparing play with dreams, but must ask oneself: When does something occur in human life that makes the powers developed in this first childhood play before the change of teeth fruitful for the whole of external human life? When does one actually reap the fruits of childhood play? One usually thinks that one must look for these fruits of childlike play in the immediately following epoch of life, and this is precisely what spiritual science is supposed to show, how life proceeds in a kind of rhythmic repetition. Just as a plant seed develops leaves in various forms, first sepals, then petals, and so on, and then the seed reappears, as if something lies in between and the repetition of the earlier stage occurs after an intervening period, so it is in human life.

Through the most diverse ways of looking at things, we have been led to understand human life as if each successive age were the effect of the previous one. This is not the case. If we engage in unbiased observation, we find that the actual fruits of the life activity that occurs in the first game only come out in our twenties. What we acquire in play from birth to the change of teeth, what is lived out in dreams by the child, are the forces of the as yet unborn spirituality of the human being, the spirituality of the human being that has not yet been absorbed, or resorbed, if you prefer, into the body. It is like this: I have explained to you how the same powers that work organically in the human being until the change of teeth are then independent when they have given birth to the teeth, as imaginative and thinking activity; in a sense, something is drawn out of the physical body. What the child does in play, which is not yet connected with life and has no inherent usefulness, is something that has not yet grown together with the body; so that the child has a soul activity that works in the body until the change of teeth and then emerges as a power for forming concepts that can then be remembered. On the other hand, it has a spiritual-soul activity that, in a sense, still hovers slightly ethereally above the child, which is active in play in the same way that dreams are active throughout life. But this activity is not developed in the child merely in dreams; it is developed in play, that is, in an external reality. What is developed in this external reality recedes, so to speak. Just as the germ-forming power in the plant recedes into the leaf and petal and only reappears in the fruit, so what is applied and expended in the child only reappears around the age of 21 or 22 in the human being as the intellect, which now independently gathers experience in life. And here I would like to ask you: try to really seek out this connection, really conscientiously observe children, try to understand the individuality of their play, indeed to understand the individuality of children's free play until they lose their baby teeth, and form pictures of the individualities of children, and first of all assume hypothetically: the individual character that is noticeable in play until the change of teeth reappears in some way in the special character of the independent judgment of the human being after the age of 20; that is, the types of human beings after the age of 20 are different in terms of their independent judgment, just as children are different in their play before the change of teeth.

If you think about this in terms of the full reality, then you actually develop, I would say, an unlimited sense of responsibility towards education and also teaching; because you come to say to yourself: what you do with the child now will shape the person beyond the age of twenty. This shows that you have to know the whole of life, not just childhood, if you want to develop the right educational approach.