Soul Economy

Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education

GA 303

5 January 1922, Stuttgart

XIV. Aesthetic Education

The human organization and its various bodies, or members, as I have described them to you, helps in understanding the whole human being. It’s an image that can be presented from many different viewpoints, and it is these manifold aspects that enable us to go further into what lies behind the human constitution. I have spoken about the human astral body as being the member of the human being that, using spatial and temporal relationships in its own way, breaks all bounds of space and time, as it were. I have tried to describe how we can experience something of this quality in our dreams, which emanate largely from the astral body and weave together incidents of our lives, otherwise separated by time, into continuous dream imagery.

We can characterize the astral body from many aspects, one of which is based on events in the human being during the process of sexual maturity. If we observe the relevant phenomena and their underlying forces, we arrive at a picture of the astral body, because puberty is the time of its birth, when it can be freely used by a human being.

St. Augustine (354–430), the medieval writer, tried to approach the human astral body in yet another way. I wish to point out that, in his writings, we find a description of the invisible members of the human being that agrees with the one spiritual science provides. His findings, however, were the outcome of an instinctive clairvoyance, once the common heritage of all humankind, and not the result of conscious investigation into the spiritual realm, as practiced in anthroposophy.

St. Augustine’s description of the astral body gaining independence at puberty is truly characteristic of human life. He says that, because of the fundamental properties of the astral body, people can understand all the human inventions that affect human life. If we build a house, make a plough, or invent a spinning machine, we do so by using forces directly connected to the astral body. It is a fact that, through the astral body, human beings learn about everything in their environment that is produced by human activity. It is therefore fully consistent with a true knowledge of the human being when, as educators, we introduce adolescents to the practical side of life and the results of human ingenuity. This, however, is a far more complicated process today than in St. Augustine’s time, when life was much simpler.

Only by applying what I have called soul economy in teaching can we hope to succeed in planning an education for students between fifteen and twenty (or even older) that will gradually introduce them to the manifold contrivances surrounding them today. Just think for a moment of how much we fall short of this in our present civilization. You just need to ask yourselves how many people regularly use the telephone, public transportation, or even a steam ship without having the faintest idea of how they work. In our civilization, people are practically engulfed by a technology that they do not understand. Those who believe that it is only our conscious experiences that are truly important will dismiss these remarks as irrelevant.

Certainly, it is easy to enjoy life consciously when one has successfully bought a train ticket to get where one chooses to go, or if one receives a telegram without having any real idea of how the message reached its destination or having the slightest notion of what a Morse apparatus is like. Ordinary consciousness is unconcerned about whether it understands the processes or not, and from this point of view it can be argued whether these things matter or not. But when we look at what is happening in the depths of the unconscious, the picture looks entirely different. To use modern technology with no knowledge of how things work or how they were made is like being a prisoner in a cell without windows through which one could at least look out into nature and to freedom.

Educators need to be fully aware of this. When adolescents experience differentiation between the sexes, the time is ripe for understanding other differentiations in modern life as well. Students now need to be introduced to the practical areas of life, and this is why, as puberty approaches, we include crafts such as spinning and weaving in our curriculum. Naturally, such a plan brings with it many difficulties, certainly in terms of the schedule. When planning our curriculum, we must also keep in mind the demands of other training centers, such as universities, technical colleges, or other institutions our students may wish to enter. This requires that we include subject material that, in our opinion, has less value for life. It really requires a great deal of trouble and pain to attain a balanced curriculum that depends entirely on strict soul economy in teaching. It is a very difficult task, but not impossible. This can be done if teachers develop a sense of what has real importance for life, and if teachers can communicate simply and economically to their students so that, eventually, they understand what they are doing while using a telephone, conveyance, or other modern invention. We must try to familiarize our students with the ways of today’s civilization so they can make sense of it. Even before the age of puberty, teachers must prepare the chemistry and physics lessons so that, after the onset of puberty, they can build on what has been given and then extend it as a basis for understanding the practical areas of life.

Here we must consider yet another point; students are now entering an age when, to a certain extent, they need to be grouped according to whether they will follow a more academic or practical career later on. At the same time, we must not forget that an education based on a real knowledge of the human being always strives for balance in teaching, and we need to know how this is done in practice. Naturally, we must equip students of a more academic disposition with what they will need for their future education. At the same time, if we are to retain the proper balance, any specialization (later on also) should be compensated by some broadening into otherwise neglected areas. If, on the one hand, we direct their will impulses more toward the academic side, we must also give them some concrete understanding of practical life so they do not lose sight of life as a whole. Thus, we actually fulfill the demands of the human astral body; when it guides conscious will impulses in one direction, it also feels the need for appropriate counter-impulses. A concrete example may help.

As an extreme example, it would be incorrect for a statistician to gather statistics on soap consumption in certain districts without the least notion of how soap is manufactured. No one could understand such statistics without at least a general knowledge of how soap is made. But life has become so complex that it seems there is no end to all the things we must consider. Consequently, the principles of soul economy in teaching have become more important than ever. In fact, it is the only way to deal with this large problem in education. And making it even more difficult is the fact that we ourselves are clogged with erroneous, outmoded forms of education we receive during our own education, mistakes resulting from educational traditions that are no longer justifiable today.

An ancient Greek would have been surprised to see young people of the time being introduced, before going out into life, to the ways of the Egyptians, Chaldeans, or other previous civilizations. Yet, this is more or less how it works in grade schools today. It is impossible to talk freely about these issues, however, because we have to consider how our students will fit into society as it exists.

Those of our students who are likely to follow an academic career should gain at least some experience of practical work involving manual skills. On the other hand, students who are likely to apprentice in a trade should become familiar with the sort of background one needs for a more academic career. All this should be part of the general school curriculum. It is not right to send boys and girls straight into factories to work alongside adults. Instead, various crafts should be introduced at school, so that young people can use what they have learned as a kind of model before finding their way into more professional skills. Nor do I see any reason why older students should not be given the task of manufacturing certain articles in school workshops, which can then be sold to the public. This has already been done in some of our prisons, with the prisoners’ products being sold outside.

Young people should remain in a school setting as long as possible and as long as school is constructive and healthy. It is in keeping with inner human nature to enter life gradually and not be flung into it too soon or too quickly. Today’s world youth movement has become strong because the older generation showed so little understanding of the younger generation’s needs, and older people at least understand its justification. There are deep reasons for the emergence of this movement, which should not only be recognized but channeled in the right directions. But this will be possible only when the principles of education are also channeled in the right directions.

A primary objective of Waldorf education is to prepare students for life as much as possible. Thus, when they reach their early twenties and their I-being enables them to take their full place in society, they will be able to develop the right relationship to the world as a whole. Then, young people should be able to feel a certain relationship with their elders, since it was, after all, their generation that provided the means for the younger generation. Young people should be able to appreciate and understand the achievements of the older generation. Thus, when sitting in a chair, they should not only realize that the chair was made by someone of their father’s generation but should also know something about how it was made.

Naturally, today there are many opinions that argue against introducing young people to practical life as described, but I speak here from a completely practical viewpoint. We can honestly say that, of all the past ages of human development, our present materialistic age is, in its own way, the most spiritual. Perhaps I can explain myself better by telling you something about certain theosophists I once met who were working toward a truly spiritual life. And yet they were, in fact, real materialists. They spoke of the physical body and its density. And the ether body was seen as having a certain density and corporeality, though far more rarefied. They described the astral body as infinitely less dense than the ether body, yet still having a certain density. And this is how they talked about all sorts of other mysterious things as well, believing they were reaching into higher and more spiritual spheres, until the substances they imagined would become so thin and attenuated that one would no longer know what to make of it all. All their images bore the stamp of materialism and, consequently, never reached the spiritual world at all. Strangely, the most materialistic views I ever encountered were among some members of the Theosophical Society. For instance, after giving a lecture to theosophists in Paris, I once asked a member of the audience what impression the lecture had made upon him. I had to put up with the answer that my lecture had left behind good vibrations in the room. It sounded as though one might be able to smell the impressions created by my talk. In this way, everything was reduced to the level of a materialistic interpretation.

On the other hand, I like to tell those who are willing to listen that I prefer a person with a materialistic concept of the world—one who is nevertheless capable of the spiritual activity of thinking—to a theosophist who, though striving toward the spiritual world, falls back on materialistic images. Materialists are mistaken, but even their thinking contains spirit—real spirit. It is “diluted” and abstract, but spirit nevertheless. And this way of thinking compels people to enter the realities of life. Therefore I have found materialists who are richer in spirit than those who are anxious to overcome materialism but do so in an entirely materialistic way. It is characteristic of our time that people absorb spirit in such diluted forms and can no longer recognize it. The most spiritual activity in our time, however, can be found in technological innovation, where everything arises from spirit—human spirit.

It does not require great spiritual accomplishment to put a vase of beautiful flowers on a table, since nature provides them. But to construct even the simplest machine does in fact require spiritual activity. The spirit plays a part, though it goes unnoticed, since people do not observe themselves in the right way. Spirit remains in a person’s subconscious during such activities, and human nature finds this difficult to bear unless one has mastered the necessary objectivity. Only by finding our way into practical life do we gradually learn to bear the abstract spirit, which we have poured out through today’s civilization.

I can assure you that, once an art of education based on spiritual science has gained a firm foothold, it will put people into the world who are far more practical than those who have gone through our more materialistically inclined educational systems. Waldorf education will be imbued with creative spirit, not with the dreamy kind that tempts people to close their eyes to outer reality. I will call it a true anthroposophic initiative when we find spirit without losing the firm ground under our feet.

Any teacher who wishes to introduce adolescents to the practicalities of life could easily become discouraged by the lack of manual skills that is symptomatic of our time. We really have to ask ourselves whether there is any possibility of encouraging children between their second dentition and puberty to become more practical and skilful. And if we look at life as it really is—guided by life and not by abstract ideas or theorizing—we find that the answer is to bring children as close as possible to beauty. The more we can lead them to appreciate beauty, the better prepared they will be at the time of puberty to tackle practical tasks without being harmed for the rest of their lives. Our students will not be able to safely understand the workings of conveyances or railroad engines unless an esthetic appreciation of painting or sculpture was cultivated at the right age. This is a fact that teachers should keep in mind. Beauty, however, needs to be seen as part of life, not separate and complete in itself. In this sense, our civilization must still learn a great deal, especially in the field of education.

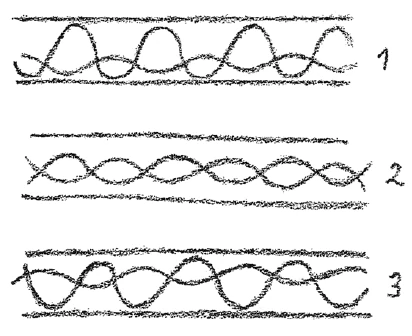

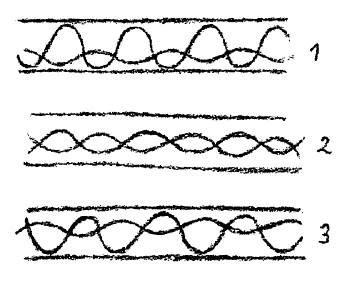

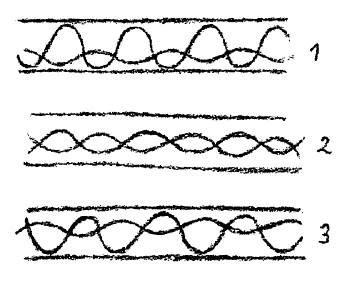

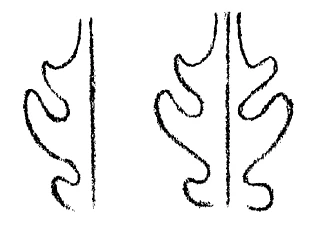

A few simple examples may give you a better idea of what is meant by cultivating a sense of beauty that is not estranged from daily life. Perhaps you have been present when handwork was done, either in a family home or in a school classroom. You may have seen girls sewing patterns into ribbons, maybe something like this (see diagram 2).

I will keep it as simple as possible and draw it merely for the sake of clarification. If you then ask a student, “What are you doing?” the answer may be, “We first sew this pattern around the neck of the dress, then on the waistband, and finally around the hem of the dress.” This kind of remark is enough to make one despair, because it shows a total disregard for fitting beauty to a given purpose. If we are sensitive to these matters and see a girl or young lady sewing the same pattern to the upper, middle, and lower parts of a dress, we can’t help feeling that when someone wears such a dress, she will appear to have been compressed or telescoped, from top to bottom. We must open our students’ eyes to the necessity of adapting a pattern according to where it appears, whether around the neck, the middle, or around the hem. The uppermost ribbon could be varied somewhat like this (diagram 1), and the bottom one in this way (diagram 3). I am keeping the patterns simple, merely for clarification. Now students can safely sew the first pattern around the neck, because the form indicates that the head will rise above it. The second pattern can be sewn into a belt, and the third to the hem, showing that its place is below. There really is a difference between above and below in the human figure, and this needs to be expressed artistically.

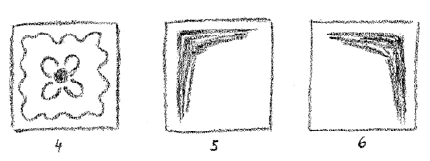

I once discovered that pillows had been embroidered in this way (diagram 4). Would you want to rest your head on a pattern with a center that will scratch your face? It was certainly not designed for putting your head on it. This pattern does not express the function of the pillow in the least. This is how it should be done (diagram 5). But now it can be used only if one’s face is turned to the left. To solve the problem artistically, we need the same arrangement on the opposite side as well (diagram 6). But this is not the correct solution either. Fortunately, art enables us to create impressions of something that does not really exist, so the pattern should create the feeling that the pillow allows our head to assume any position it chooses.

This leads us right into what I would like to call “reality within the world of appearances” as expressed through art. Only by entering this reality can we develop a faculty that could be viewed as the counter-sense of what is merely practical. Only when our sense of beauty enters the fullness of life are we able to experience the practical realm in a right and balanced way.

It has recently become fashionable to embellish pompadours with all sorts of ornamentation. When I see one of these knitting bags, I often wonder where to look for the opening. Surely the pattern on these bags should indicate the top and bottom, as well as where to put the wool. These things are generally ignored completely, just as book covers are often designed with no indication of where the pages should be opened. Such designs are chosen at random and often encourage one to leave the book closed rather than read it.

These examples merely indicate how a practical sense of beauty can be developed in young people. Unless this has been accomplished, we cannot move on to the next step, which is to fit them into the practicalities of life.

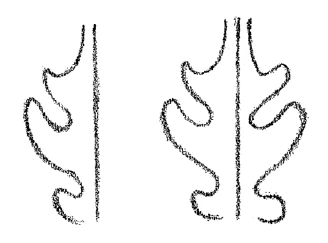

What children need is a sense of reality. Again I will choose a very simple example to show you what I mean. One could draw a pattern such as this (see diagram). Teachers must be able to evoke a feeling in children that such a pattern is intolerable because it does not represent reality, and a little practice with students who react in healthy ways will soon enable you to do so. Teachers should intensify this healthy feeling—not through suggestions, but by drawing it out of the students—to the extent that, if they see such a pattern, it will be as though they were seeing a person with only half a face or one arm or foot. Such a thing goes against the grain, because it does not represent reality. This is the kind of reaction teachers should induce in students, for it is all part of an esthetic sensibility. In other words, teachers should allow the students to feel that they cannot rest until they have completed a pattern by drawing the missing, complementary part. In this way one cultivates in children an immediate, living sense of beauty. In German, the word schön (“beautiful”) is related to the word Schein (“shine” or “glory”). Such an approach stimulates the child’s astral body to become flexible and to function well as a living member of the human being.

It is important for teachers to cultivate an esthetic sense also in themselves. Teachers quickly see how this enlivens the children. Thus, they also nurture an artistic approach to the other activities, as I have already stated in these lectures. I pointed out that everything teachers bring to children when they enter class one should be permeated by an artistic element. And when talking to children about their surroundings, teachers should do so with real artistry, since otherwise they might easily slip into anthropomorphism, restricting everything to narrow human interests. For instance, when using fairy tales or legends to clothe their lessons, teachers may be misled into telling a class that certain kinds of trees spring from the ground just so people can make corks from the bark and seal their bottles. A pictorial approach must never be presented in such terms. The pictures used at this particular age must be created from a sense of beauty. And beauty demands truth and clarity, which speaks directly to human feeling. Beauty in nature does not need anthropomorphism. If we encourage prepubescent students toward an appreciation of beauty in everything they encounter, after puberty they will take human qualities with them into the practical life, harmonizing their views of the world with the practical tasks that await them.

All this has an important bearing on the social question, which must be tackled from many different angles. Few people are aware of this today. If we could cultivate the sense of beauty that lives unspoiled in every child, it is certainly possible that we could transform all the ugliness that surrounds us in almost every European city within a few generations—and you can hardly deny that, esthetically, we are surrounded by all sorts of atrocities in virtually every large city.

Today we look at the human being from the outside and see the physical body. And we observe the inner human being in terms of the personality, or self. Between the I-being and the physical body are the astral and ether bodies, which are becoming more and more stunted today. Essentially, they are properly developed only in Asians. In the West, they are becoming atrophied and do not develop properly. By awakening an overall feeling for beauty, however, we can nurture the free development of those two bodies. During the school years, growing human beings are most receptive to an the appreciation of beauty. We should thus do everything possible to awaken and cultivate a sense of beauty in children, especially between the second dentition and the beginning of puberty so that it will live on into later life.

This is especially important with regard to speech. Languages arose from a direct human response to inner experiences. If we immerse ourselves in the quality of spoken sounds, we can still hear the important role those inner responses played in forming certain words. In our abstract life, however, the logic of language plays the leading part, and our perception of the artistic element has been almost lost. It’s true that logic is inherent in language, but it represents only the skeleton, which is dead. There is much besides logic in language, but unless you have been touched by the creative genius of language, you cannot feel its breath and pulse.

In this sense, try to feel the way words try to project themselves into outer life. I will give a typical example, and I hope you will understand it, although it is from the German language. In the word Sucht (“sickness”), you can detect the word suchen (“to seek”). When the body has a Sucht, it is looking for something that normally it would not. Certain other words point to what the body seeks. For example, Gelbsucht (“jaundice”) or Fallsucht (“epilepsy”). The word Sucht enables the human soul to experience what the body is seeking through certain forms of sickness.

The farther west we go, the more we find that people have lost the ability to appreciate the artistic element in language, which Asians can still experience. It is very important for us to regain at least some basic experience of the living genius of language. This will especially promote worldwide social understanding. Forgive me if I use another example—near and dear to me—to explain what I mean. But please be very careful not to misunderstand what I am about to say. On page eighty-eight in the English translation of my book Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage—translated as The Threefold Commonwealth—I find this: “The freedom of one cannot prosper without the freedom of all.” This sentence makes no sense when weighed by a deep feeling for words. As I said, you must not misunderstand me, but this English sentence is simply nonsense, because it says something very different from the original German words, which read, “Die Freiheit des Einen kann micht ohne die Freiheit des Anderen gedeihen.” This sentence really tries to say something completely different.

To convey its meaning correctly, the translator would have to circumscribe it completely. The translation of any book should read as if it were written directly from the genius of the new language; anything else is unacceptable. I know for certain that Bentham’s hair would stand on end if, in the astral world, he were to encounter “The freedom of one cannot prosper without the freedom of all.” It simply does not stand up to clear thinking, and for a particular reason. If you encountered such a sentence, you would immediately respond that, yes, freedom exists, but the author talks about something that does not apply to England, especially if you relate it to education. In the original German, however, this is not the situation. There it does make sense. But when translated as quoted, the real meaning of the original cannot be understood. Why is this?

I will demonstrate by focusing on the significant word in the sentence. In English, the word is freedom. If we match the quality of this word with the corresponding German word, one would have to use Freitum—the ending “dom” in English corresponds to the ending “tum” in German. If such a word existed, we could use freedom with impunity. Freitum would then be translated as “freedom,” and there would be no misunderstanding. But the word used in the original text is Freiheit—the ending “heit” corresponds to the English ending “hood.” To show you that the translation of Freiheit as “freedom” does not harmonize with the genius of language, I will use another German word, Irrtum (“error”), which expresses a definite fact that happens only once. If we wanted to give this word the ending “heit,” we would have to form the word Irreheit. You won’t find this word in any German dictionary, but it would not go against the genius of the language to invent it. It would be quite possible to use it. Irreheit immediately leads us to the inner human being. It expresses a quality of inner human nature. There are no words in the German language ending with “heit” that do not point to something flexible within a person. Such words carry their meaning toward a person. Indeed, it is a pity that we do not use the word Freitum in German, because, if it existed, we could express the meaning of the English word freedom directly, without circumscribing it.

This kind of thing leads us right into the depths of language itself and makes us aware of the genius of language. Consequently, when I write a book in German, I try to choose words that can be translated correctly into other languages—and my German readers do not hesitate to call it poor style. But this is not always possible. If, for example, a book is addressed to the culture of Germany, it may be necessary sometimes to consider the German situation first. And this is why I have repeatedly used the word Freiheit, which should never be translated as “freedom.” My book Die Philosophie der Freiheit should never be titled in English The Philosophy of Freedom. A correct English title for this book has yet to be found.

It is also very interesting to look at these things from a statistical point of view. In doing so, I am being neither pedantic nor unscrupulous, but my findings are the results of deliberate investigation. If I were to write a book about education in German, the word Freiheit would appear again and again in certain chapters. To find out whether the corresponding word freedom could be also used in an English book on education, I carefully looked through the likely chapters of such a book, and discovered that the word freedom did not appear at all, not once. This is the sort of thing for which we should develop a fine perception, because it is the very thing we need for greater world understanding. And it should be considered during the school years as well. I am keenly aware of this when writing books, as I mentioned. Consequently I am very cautious in the choice of certain words. If, for example, I use the German word Natur in various sentences, I can be certain that it will be translated as the word nature in English. There is no doubt at all that Natur would be translated as nature. And yet, the English word nature would awaken a very different concept than would the German word Natur. This is why, when anticipating translations, I have paraphrased certain words in some of my writings. I do this to avoid the wrong interpretation of what I want to say. Of course, there have been numerous times when I used the word Natur, but when it was important to match the German concept with a foreign one, I paraphrased Natur with “the sensory world” (die sinnliche Welt), especially if the book was likely to be translated into Western languages. To me, “the sensory world” seems to match, more or less, the concept of Natur as used in German. Obviously, I expected sinnliche Welt to be translated as nature in English, only to find that, again, it was translated literally into “the sensory world.” It really is very important to be aware of the living genius of language, especially where an artistic treatment of language is concerned.

Apart from the fact that the genius of language was not recognized in the translation of the sentence I quoted (I simply mention this in passing), you will also find the following wording: “The freedom of one cannot prosper without the freedom of all.” Again, this makes no sense in German. It was neither written nor implied. The original sentence says, “The freedom of one cannot prosper without the freedom of the other”—in other words, our fellow human beings, or neighbors. That is the real point.

I ask you again not to misunderstand my intentions. I chose this example, near and dear to me, to show how we have reached a stage in human development where, instead of experiencing the realities of life, we tend to skim over them, and language offers a particularly striking example of this. Our civilization has gradually made us rather sloppy. Now we must make an effort to go into language again and to live with the words. Until we do this, we will not be able to meet the request I made earlier—that children, after being introduced to grammar and then to the rhetoric and beauty of language, should eventually be brought to an appreciation of the artistic element of language. We must open the eyes and hearts of students to the artistic element that lives in language. This is also important in nurturing a stronger feeling of community with other nations. And it is equally important to look, in very new and different ways, at what is usually called the social question.

Questions and Answers

Rudolf Steiner: Several questions have been handed in and I will try to answer as many as possible in the short time available.

First Question: This question has to do with the relationship between sensory and motor nerves and is, primarily, a matter of interpretation. When considered only from a physical point of view, one’s conclusion will not differ from the usual interpretation, which deals with the central organ. Let me take a simple case of nerve conduction. Sensation would be transmitted from the periphery to the central organ, from which the motor impulse would pass to the appropriate organ. As I said, as long as we consider only the physical, we might be perfectly satisfied with this explanation. And I do not believe that any other interpretation would be acceptable, unless we are willing to consider the result of suprasensory observations, that is, all-inclusive, real observation.

As I mentioned in my discussions of this matter over the past few days, the difference between the sensory and motor nerves, anatomically and physiologically, is not very significant. I never said that there is no difference at all, but that the difference was not very noticeable. Anatomical differences do not contradict my interpretation. Let me say this again: we are dealing here with only one type of nerves. What people call the “sensory” nerves and “motor” nerves are really the same, and so it really doesn’t matter whether we use sensory or motor for our terms. Such distinctions are irrelevant, since these nerves are (metaphorically) the physical tools of undifferentiated soul experiences. A will process lives in every thought process, and, vice versa, there is an element of thought, or a residue of sensory perception, in every will process, although such processes remain mostly unconscious.

Now, every will impulse, whether direct or the result of a thought, always begins in the upper members of the human constitution, in the interplay between the I-being and the astral body. If we now follow a will impulse and all its processes, we are not led to the nerves at all, since every will impulse intervenes directly in the human metabolism. The difference between an interpretation based on anthroposophic research and that of conventional science lies in science’s claim that a will impulse is transmitted to the nerves before the relevant organs are stimulated to move.

In reality, this is not the case. A soul impulse initiates metabolic processes directly in the organism. For example, let’s look at a sensation as revealed by a physical sense, say in the human eye. Here, the whole process would have to be drawn in greater detail. First a process would occur in the eye, then it would be transmitted to the optic nerve, which is classified as a sensory nerve by ordinary science. The optic nerve is the physical mediator for seeing.

If we really want to get to the truth of the matter, I will have to correct what I just said. It was with some hesitation that I said that the nerves are the physical instruments of human soul experiences, because such a comparison does not accurately convey the real meaning of physical organs and organic systems in a human being. Think of it like this: imagine soft ground and a path, and that a cart is being driven over this soft earth. It would leave tracks, from which I could tell exactly where the wheels had been. Now imagine that someone comes along and explains these tracks by saying, “Here, in these places, the earth must have developed various forces that it.” Such an interpretation would be a complete illusion, since it was not the earth that was active; rather, something was done to the earth. The cartwheels were driven over it, and the tracks had nothing to do with an activity of the earth itself.

Something similar happens in the brain’s nervous system. Soul and spiritual processes are active there. As with the cart, what is left behind are the tracks, or imprints. These we can find. But the perception in the brain and everything retained anatomically and physiologically have nothing to do with the brain as such. This was impressed, or molded, by the activities of soul and spirit. Thus, it is not surprising that what we find in the brain corresponds to events in the sphere of soul and spirit. In fact, however, this is completely unrelated to the brain itself. So the metaphor of physical tools is not accurate. Rather, we should see the whole process as similar to the way I might see myself walking. Walking is in no way initiated by the ground I walk on; the earth is not my tool. But without it, I could not walk. That’s how it is. My thinking as such—that is, the life of my soul and spirit—has nothing to do with my brain. But the brain is the ground on which this soul substance is retained. Through this process of retention, we become conscious of our soul life.

So you see, the truth is quite different from what people usually imagine. There has to be this resistance wherever there is a sensation. In the same way that a process occurs (say in the eye) that can be perceived with the help of a so-called sensory nerve, in the will impulses (in one’s leg, for example), a process occurs, and it is this process that is perceived with the help of the nerve. The so-called sensory nerves are organs of perception that spread out into the senses.

The so-called motor nerves spread inward and convey perceptions of will force activities, making us aware of what the will is doing as it works directly through the metabolism. Both sensory and motor nerves transmit sensations; sensory nerves spread outward and motor nerves work inward. There is no significant difference between these two kinds of nerves. The function of the first is to make us aware, in the form of thought processes, of processes in the sensory organs, while the other “motor” nerves communicate processes within the physical body, also in form of thought processes.

If we perform the well-known and common experiment of cutting into the spinal fluid in a case of tabes dorsalis, or if one interprets this disorder realistically, without the usual bias of materialistic physiology, this illness can be explained with particular clarity. In the case of tabes dorsalis, the appropriate nerve (I will call it a sensory nerve) would, under normal circumstances, make a movement sense-perceptible, but it is not functioning, and consequently the movement cannot be performed, because movement can take place only when such a process is perceived consciously. It works like this: imagine a piece of chalk with which I want to do something. Unless I can perceive it with my senses, I cannot do what I want. Similarly, in a case of tabes dorsalis, the mediating nerve cannot function, because it has been injured and thus there is no transmission of sensation. The patient loses the possibility of using it. Likewise, I would be unable to use a piece of chalk if it were lying somewhere in a dark room where I could not find it. Tabes dorsalis is the result of a patient’s inability to find the appropriate organs with the help of the sensory nerves that enter the spinal fluid.

This is a rather rough description, and it could certainly be explained in greater detail. Any time we look at nerves in the right way, severing them proves this interpretation. This particular interpretation is the result of anthroposophic research. In other words, it is based on direct observation. What matters is that we can use outer phenomena to substantiate our interpretation. To give another example, a so-called motor nerve may be cut or damaged. If we join it to a sensory nerve and allow it to heal, it will function again. In other words, it is possible to join the appropriate ends of a “sensory” nerve to a “motor” nerve, and, after healing, the result will be a uniform functioning. If these two kinds of nerves were radically different, such a process would be impossible.

There is yet another possibility. Let us take it in its simplest form. Here a “sensory” nerve goes to the spinal cord, and a “motor” nerve leaves the spinal cord, itself a sensory nerve (see drawing). This would be a case of uniform conduction. In fact, all this represents a uniform conduction. And if we take, for example, a simple reflex movement, a uniform process takes place. Imagine a simple reflex motion; a fly settles on my eyelid, and I flick it away through a reflex motion. The whole process is uniform. What happens is merely an interpretation. We could compare it to an electric switch, with one wire leading into it and another leading away from it. The process is really uniform, but it is interrupted here, similar to an electric current that, when interrupted, flashes across as an electric spark. When the switch is closed, there is no spark. When it is open, there is a spark that indicates a break in the circuit. Such uniform conductions are also present in the brain and act as links, similar to an electric spark when an electric current is interrupted. If I see a spark, I know there is a break in the nerve’s current. It’s as though the nerve fluid were jumping across like an electric spark, to use a coarse expression. And this makes it possible for the soul to experience this process consciously. If it were a uniform nerve current passing through without a break in the circuit, it would simply pass through the body, and the soul would be unable to experience anything.

This is all I can say about this for the moment. Such theories are generally accepted everywhere in the world, and when I am asked where one might be able to find more details, I may even mention Huxley’s book on physiology as a standard work on this subject.

There is one more point I wish to make. This whole question is really very subtle, and the usual interpretations certainly appear convincing. To prove them correct, the so-called sensory parts of a nerve are cut, and then the motor parts of a nerve are cut, with the goal of demonstrating that the sensations we interpret as movement are no longer possible. If you take what I have said as a whole, however, especially with regard to the interrupt switch, you will be able to understand all the various experiments that involve cutting nerves.

Question: How can educators best respond to requests, coming from children between five and a half and seven, for various activities?

Rudolf Steiner: At this age, a feeling for authority has begun to make itself felt, as I tried to indicate in the lectures here. Yet a longing for imitation predominates, and this gives us a clue about what to do with these children. The movable picture books that I mentioned are particularly suitable, because they stimulate their awakening powers of fantasy.

If they ask to do something—and as soon as we have the opportunity of opening a kindergarten in Stuttgart, we shall try to put this into practice—if the children want to be engaged in some activity, we will paint or model with them in the simplest way, first by doing it ourselves while they watch. If children have already lost their first teeth, we do not paint for them first, but encourage them to paint their own pictures. Teachers will appeal to the children’s powers of imitation only when they want to lead them into writing through drawing or painting. But in general, in a kindergarten for children between five and a half and seven, we would first do the various activities in front of them, and then let the children repeat them in their own way. Thus we gradually lead them from the principle of imitation to that of authority.

Naturally, this can be done in various ways. It is quite possible to get children to work on their own. For instance, one could first do something with them, such as modeling or drawing, which they are then asked to repeat on their own. One has to invent various possibilities of letting them supplement and complete what the teacher has started. One can show them that such a piece of work is complete only when a child has made five or ten more such parts, which together must form a whole. In this way, we combine the principle of imitation with that of authority. It will become a truly stimulating task for us to develop such ideas in practice once we have a kindergarten in the Waldorf school. Of course, it would be perfectly all right for you to develop these ideas yourself, since it would take too much of our time to go into greater detail now.

Question: Will it be possible to have this course of lectures published in English?

Rudolf Steiner: Of course, these things always take time, but I would like to have the shorthand version of this course written out in long hand as soon as it can possibly be done. And when this is accomplished, we can do what is necessary to have it published in English as well.

Question: Should children be taught to play musical instruments, and if so, which ones?

Rudolf Steiner: In our Waldorf school, I have advocated the principle that, apart from being introduced to music in a general way (at least those who show some special gifts), children should also learn to play musical instruments technically. Instruments should not be chosen ahead of time but in consultation with the music teacher. A truly good music teacher will soon discover whether a child entering school shows specific gifts, which may reveal a tendency toward one instrument or another. Here one should definitely approach each child individually. Naturally, in the Waldorf school, these things are still in the beginning stage, but despite this, we have managed to gather very acceptable small orchestras and quartets.

Question: Do you think that composing in the Greek modes, as discovered by Miss Schlesinger, means a real advance for the future of music? Would it be advisable to have instruments, such as the piano, tuned in such modes? Would it be a good thing for us to get accustomed to these modes?

Rudolf Steiner: For several reasons, it is my opinion that music will progress if what I call “intensive melody” gradually plays a more significant role. Intensive melody means getting used to the sound of even one note as a kind of melody. One becomes accustomed to a greater tone complexity of each sound. This will eventually happen. When this stage is reached, it leads to a certain modification of our scales, simply because the intervals become “filled” in a way that is different from what we are used to. They are filled more concretely, and this in itself leads to a greater appreciation of certain elements in what I like to call “archetypal music” (elements also inherent in Miss Schlesinger’s discoveries), and here important and meaningful features can be recognized. I believe that these will open a way to enriching our experience of music by overcoming limitations imposed by our more or less fortuitous scales and all that came with them. So I agree that by fostering this particular discovery we can advance the possibilities of progress in music.

Question: Is it also possible to give eurythmy to physically handicapped children, or perhaps curative eurythmy to fit each child?

Rudolf Steiner: Yes, absolutely. We simply have to find ways to use eurythmy in each situation. First we look at the existing forms of eurythmy in general, then we consider whether a handicapped child can perform those movements. If not, we may have to modify them, which we can do anyway. One good method is to use artistic eurythmy as it exists for such children, and this especially helps the young children—even the very small ones. Ordinary eurythmy may lead to very surprising results in the healing processes of these children.

Curative eurythmy was worked out systematically—initially by me during a supplementary course here in Dornach in 1921, right after the last course to medical doctors. It was meant to assist various healing processes. Curative eurythmy is also appropriate for children suffering from physical handicaps. For less severe cases, existing forms of curative eurythmy will be enough. In more severe cases, these forms may have to be intensified or modified. However, any such modifications must be made with great caution.

Artistic eurythmy will not harm anyone; it is always beneficial. Harmful consequences arise only through excessive or exaggerated eurythmy practice, as would happen with any type of movement. Naturally, excessive eurythmy practice leads to all sorts of exhaustion and general asthenia, in the same way that we would harm ourselves by excessive efforts in mountain climbing or, for example, by working our arms too much. Eurythmy itself is not to blame, however, only its wrong application. Any wholesome activity may lead to illness when taken too far.

With ordinary eurythmy, one cannot imagine that it would harm anyone. But with curative eurythmy, we must heed a general rule I gave during the curative eurythmy course. Curative eurythmy exercises should be planned only with the guidance and supervision of a doctor, by the doctor and curative eurythmist together, and only after a proper medical diagnosis.

If curative exercises must be intensified, it is absolutely essential to proceed on a strict medical basis, and only a specialist in pathology can decide the necessary measures to be taken. It would be irresponsible to let just anyone meddle with curative eurythmy, just as it would be irresponsible to allow unqualified people to dispense dangerous drugs or poisons. If injury were to result from such bungling methods, it would not be the fault of curative eurythmy.

Question: In yesterday’s lecture we heard about the abnormal consequences of shifting what was right for one period of life into later periods and the subsequent emergence of exaggerated phlegmatic and sanguine temperaments. First, how does a pronounced choleric temperament come about? Second, how can we tell when a young child is inclined too much toward melancholic or any other temperament? And third, is it possible to counteract such imbalances before the change of teeth?

Rudolf Steiner: The choleric temperament arises primarily because a person’s I-being works with particular force during one of the nodal points of life, around the second year and again during the ninth and tenth years. There are other nodal points later in life, but we are interested in the first two here. It is not that one’s I-being begins to exist only in the twenty-first year, or is freed at a certain age. It is always present in every human being from the moment of birth—or, more specifically, from the third week after conception. The I can become too intense and work with particular strength during these times. So, what is the meaning and nature of such nodal points?

Between the ninth and tenth years, the I works with great intensity, manifesting as children learn to differentiate between self and the environment. To maintain normal conditions, a stable equilibrium is needed, especially at this stage. It’s possible for this state of equilibrium to shift outwardly, and this becomes one of many causes of a sanguine temperament. When I spoke about the temperaments yesterday, I made a special point in saying that various contributing factors work together, and that I would single out those that are more important from a certain point of view.

It is also possible for the center of gravity to shift inward. This can happen even while children are learning to speak or when they first begin to pull themselves up and learn to stand upright. At such moments, there is always an opportunity for the I to work too forcefully. We have to pay attention to this and try not to make mistakes at this point in life—for example, by forcing a child to stand upright and unsupported too soon. Children should do this only after they have developed the faculty needed to imitate the adult’s vertical position.

You can appreciate the importance of this if you notice the real meaning of the human upright position. In general, animals are constituted so that the spine is more or less parallel to the earth’s surface. There are exceptions, of course, but they may be explained just on the basis of their difference. Human beings, on the other hand, are constituted so that, in a normal position, the spine extends along the earth’s radius. This is the radical difference between human beings and animals. And in this radical difference we find a response to strict Darwinian materialists (not Darwinians, but Darwinian materialists), who deny the existence of a defining difference between the human skeleton and that of the higher animals, saying that both have the same number of bones and so on. Of course, this is correct. But the skeleton of an animal has a horizontal spine, and a human spine is vertical. This vertical position of the human spine reveals a relationship to the entire cosmos, and this relationship means that human beings bear an I-being. When we talk about animals, we speak of only three members—the physical body, the ether body (or body of formative forces), and the astral body. I-being incarnates only when a being is organized vertically.

I once spoke of this in a lecture, and afterward someone came to me and said, “But what about when a human being sleeps? The spine is certainly horizontal then.” People often fail to grasp the point of what I say. The point is not simply that the human spine is constituted only for a vertical position while standing. We must also look at the entire makeup of the human being—the mutual relationships and positions of the bones that result in walking with a vertical spinal column, whereas, in animals, the spine remains horizontal. The point is this: the vertical position of the human spine distinguishes human beings as bearers of I-being.

Now observe how the physiognomic character of a person is expressed with particular force through the vertical. You may have noticed (if the correct means of observation were used) that there are people who show certain anomalies in physical growth. For instance, according to their organic nature, they were meant to grow to a certain height, but because another organic system worked in the opposite direction, the human form became compressed. It is absolutely possible that, because of certain antecedents, the physical structure of a person meant to be larger was compressed by an organic system working in the opposite direction. This was the case with Fichte, for example. I could cite numerous others—Napoleon, to mention only one. In keeping with certain parts of his organic systems, Fichte’s stature could have become taller, yet he was stunted in his physical growth. This meant that his I had to put up with existing in his compressed body, and a choleric temperament is a direct expression of the I. A choleric temperament can certainly be caused by such abnormal growth.

Returning to our question—How can we tell when a young child is inclined too much toward melancholic or another temperament?—I think that hardly anyone who spends much time with children needs special suggestions, since the symptoms practically force themselves on us. Even with very naive and unskilled observation, we can discriminate between choleric and melancholic children, just as we can clearly distinguish between a child who “just sits” and seems morose and miserable and one who wildly romps around. In the classroom, it is very easy to spot a child who, after having paid attention for a moment to something on the blackboard, suddenly turns to a neighbor for stimulation before looking out the window again. This is what a sanguine child is like. These things can easily be observed, even on a very naive level.

Imagine a child who easily flies into a fit of temper. If, at the right age, an adult simulates such tantrums, it may cause the child to tire of that behavior. We can be quite successful this way. Now, if one asks whether we can work to balance these traits before the change of teeth, we must say yes, using essentially the same methods we would apply at a later age, which have already been described. But at such an early age, these methods need to be clothed in terms of imitation.

Before the change of teeth, however, it is not really necessary to counteract these temperamental inclinations, because most of the time it works better to just let these things die off naturally. Of course, this can be uncomfortable for the adult, but this is something that requires us to think in a different way. I would like to clarify this by comparison. You probably know something of lay healers, who may not have a thorough knowledge of the human organism but can nevertheless assess abnormalities and symptoms of illnesses to a certain degree. It may happen that such a healer recognizes an anomaly in the movements of a patient’s heart. When asked what should be done, a possible answer is, “Leave the heart alone, because if we brought it back to normal activity, the patient would be unable to bear it. The patient needs this heart irregularity.” Similarly, it is often necessary to know how long we should leave a certain condition alone, and in the case of choleric children, how much time we must give them to get over their tantrums simply through exhaustion. This is what we need to keep in mind.

Question: How can a student of anthroposophy avoid losing the capacity for love and memory when crossing the boundary of sense-perceptible knowing?

Rudolf Steiner: This question seems to be based on an assumption that, during one’s ordinary state of consciousness, love and the memory are both needed for life. In ordinary life, one could not exist without the faculty of remembering. Without this spring of memory, leading back to a certain point in early childhood, the continuity of one’s ego could not exist. Plenty of cases are known in which this continuity has been destroyed, and definite gaps appear in the memory. This is a pathological condition. Likewise, ordinary life cannot develop without love.

But now it needs to be said that, when a state of higher consciousness is reached, the substance of this higher consciousness is different from that of ordinary life. This question seems to imply that, in going beyond the limits of ordinary knowledge, love and memory do not manifest past the boundaries of knowledge. This is quite correct. At the same time, however, it has always been emphasized that the right kind of training consists of retaining qualities that we have already developed in ordinary consciousness; they stay alive along with these new qualities. It is even necessary (as you can find in my book How to Know Higher Worlds) to enhance and strengthen qualities developed in ordinary life when entering a state of higher consciousness. This means that nothing is taken away regarding the inner faculties we developed in ordinary consciousness, but that something more is required for higher consciousness, something not attained previously. To clarify this, I would like to use a somewhat trivial comparison, even if it does not completely fit the situation.

As you know, if I want to move by walking on the ground, I must keep my sense of balance. Other things are also needed to walk properly, without swaying or falling. Well, when learning to walk on a tightrope, one loses none of the faculties that serve for walking on the ground. In learning to walk on a tightrope, one meets completely different conditions, and yet it would be irrelevant to ask whether tightrope walking prevents one from being able to walk properly on an ordinary surface. Similarly, the attainment of a different consciousness does not make one lose the faculties of ordinary consciousness—and I do not mean to imply at all that the attainment of higher consciousness is a kind of spiritual tightrope walking. Yet it’s true that the faculties and qualities gained in ordinary consciousness are fully preserved when rising to a state of enhanced consciousness.

And now, because it is getting late, I would like to deal with the remaining questions as quickly as possible, so I can end our meeting by telling you a little story.

Question: What should our attitude be toward the ever-increasing use of documentary films in schools, and how can we best explain to those who defend them that their harmful effects are not balanced by their potential educational value?

Rudolf Steiner: I have tried to get behind the mysteries of film, and whether or not my findings make people angry is irrelevant, since I am just giving you the facts. I have to admit that the films have an extremely harmful effect on what I have been calling the ether, or life, body. And this especially true in terms of the human sensory system. It is a fact that, by watching film productions, the entire human soul-spiritual constitution becomes mechanized. Films are external means for turning people into materialists. I tested these effects, especially during the war years when film propaganda was made for all sorts of things. One could see how audiences avidly absorbed whatever was shown. I was not especially interested in watching films, but I did want to observe their effects on audiences. One could see how the film is simply an intrinsic part of the plan to materialize humankind, even by means of weaving materialism into the perceptual habits of those who are watching. Naturally, this could be taken much further, but because of the late hour there is only time for these brief suggestions.

Question: How should we treat a child who, according to the parents, sings in tune at the age of three, and who, by the age of seven, sings very much out of tune?

Rudolf Steiner: First we would have to look at whether some event has caused the child’s musical ear to become masked for the time being. But if it is true that the child actually did sing well at three, we should be able to help the child to sing in tune again with the appropriate pedagogical treatment. This could be done by studying the child’s previous habits, when there was the ability to sing well. One must discover how the child was occupied—the sort of activities the child enjoyed and so on. Then, obviously, with the necessary changes according to age, place the child again into the whole setting of those early years, and approach the child with singing again. Try very methodically to again evoke the entire situation of the child’s early life. It is possible that some other faculty may have become submerged, one that might be recovered more easily.

Question: What is attitude of spiritual science toward the Montessori system of education and what would the consequences of this system be?

Rudolf Steiner: I really do not like to answer questions about contemporary methods, which are generally backed by a certain amount of fanaticism. Not that I dislike answering questions, but I have to admit that I do not like answering questions such as, What is the attitude of anthroposophy toward this or that contemporary movement? There is no need for this, because I consider it my task to represent to the world only what can be gained from anthroposophic research. I do not think it is my task to illuminate other matters from an anthroposophic point of view. Therefore, all I wish to say is that when aims and aspirations tend toward a certain artificiality—such as bringing to very young children something that is not part of their natural surroundings but has been artificially contrived and turned into a system—such goals cannot really benefit the healthy development of children. Many of these new methods are invented today, but none of them are based on a real and thorough knowledge of the human being. Of course we can find a great deal of what is right in such a system, but in each instance it is necessary to reduce also the positive aspects to what accords with a real knowledge of the human being.

And now, ladies and gentlemen, with the time left after the translation of this last part, I would like to drop a hint. I do not want to be so discourteous as to say, in short, that every hour must come to an end. But since I see that so many of our honored guests here feel as I do, I will be polite enough to meet their wishes and tell a little story—a very short story. There once lived a Hungarian couple who always had guests in the evening (in Hungary, people were very hospitable before everything went upside down). And when the clock struck ten, the husband used to say to his wife, “Woman, we must be polite to our guests. We must retire now because surely our guests will want to go home.”

Vierzehnter Vortrag

Dasjenige, was ich Ihnen als Gliederung der menschlichen Wesenheit dargestellt habe und was dienen kann, eine totale Menschenerkenntnis zu erringen, das kann von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus dargestellt werden, und gerade wenn es von den verschiedensten Gesichtspunkten aus dargestellt wird, so kommt der Mensch allmählich zu einer wirklichen Erkenntnis desjenigen, was eigentlich dahintersteckt. Ich habe Ihnen von dem astralischen Leibe gesprochen, also von demjenigen Gliede der menschlichen Wesenheit, das sich gewissermaßen über die räumlichen sowohl wie die zeitlichen Zusammenhänge hinwegsetzt, das in freier Weise die räumlichen und die zeitlichen Zusammenhänge braucht. Ich habe versucht zu zeigen, wie dies im Traume mit seinen Bildern zum Ausdrucke kommt, indem gezeigt wurde, daß ja der Traum im wesentlichen von dem astralischen Leibe herrührt, und daß der Traum das zeitlich Auseinanderstehende in seinen Bildern ineinander verwebt.

Man kann viele Gesichtspunkte wählen, um das zu charakterisieren, was der menschliche astralische Leib ist. Man kann zum Beispiel auch versuchen, einen Einblick zu gewinnen in all diejenigen Eigenschaften und Zustände, die der Mensch mit der Geschlechtsreife aus sich heraus entwickelt, und man wird, indem man auf diese Zustände, auf diese Kräfte sieht, auch ein Bild des Astralleibes gewinnen; denn mit der Geschlechtsreife wird gerade das zur freien Behandlung des Menschen geboren, was der astralische Leib ist.

Augustinus, der mittelalterliche Schriftsteller, sucht nun in einer anderen Art an den astralischen Leib heranzukommen. Ich muß betonen, daß man bei Augustinus durchaus noch die Gliederung des Menschen in dem Sinne findet, wie ich sie hier darstelle, nicht aus der bewußten anthroposophischen Forschung heraus, sondern bei Augustinus wird sie verzeichnet aus dem instinktiven Hellsehen, das die Menschheit einmal gehabt hat. Und die Art, wie Augustinus diese Seite des astralischen Leibes charakterisiert, die mit dem Geschlechtsalter im Menschen zur freien Entfaltung kommt, ist für das Leben des Menschen ganz charakteristisch. Augustinus sagt nämlich eigentlich: Durch die Grundeigenschaften des astralischen Leibes mache sich der Mensch mit alledem bekannt, was durch die Menschheit künstlich in die Menschheitsentwickelung hineinwellt. Wenn wir ein Haus bauen, einen Pflug fabrizieren, eine Spinnmaschine konstruieren, so ist das so, daß die Kräfte, die dabei vom Menschen in Betracht kommen, an den astralischen Leib gebunden sind. Der Mensch lernt tatsächlich durch seinen astralischen Leib dasjenige kennen, was ihn in der Außenwelt von dem durch Menschen selbst Hervorgebrachten umgibt.

Daher ist es durchaus auf eine wahre Menschenerkenntnis begründet, wenn wir uns im Erziehungs- und Unterrichtswesen bemühen, den Menschen von dem Zeitpunkte an, wo er durch die Geschlechtsreife hindurchgeht, praktisch in diejenigen Seiten des Lebens einzuführen, die vom Menschen selbst hervorgebracht worden sind. Das ist allerdings heute eine kompliziertere Sache als zur Zeit des heiligen Augustin. Damals war das Leben um den Menschen herum wesentlich einfacher. Heute ist es kompliziert geworden. Aber gerade dem, was ich an den vorhergehenden Tagen seelische Ökonomie im Unterrichts- und Erziehungswesen genannt habe, dem muß es gelingen, auch heute auf den geschlechtsreifen Menschen so hinzuschauen, daß er in der Zeit vom fünfzehnten bis gegen das zwanzigste Jahr oder noch über das zwanzigste Jahr hinaus nach und nach so erzogen wird, daß er in das ihn umgebende künstliche Menschendasein hineingeführt wird.

Bedenken Sie nur, wieviel unserer ganzen Zivilisation nach dieser Richtung hin eigentlich fehlt. Fragen Sie sich einmal, ob es nicht zahlreiche Menschen gibt, die sich heute des Telephons, des Tramway bedienen, ja man kann sogar sagen, des Dampfschiffes bedienen, ohne eine Vorstellung davon zu haben, was da eigentlich geschieht im Dampfschiff, im Telephon und in der Fortbewegung des Tramwaywagens. Der Mensch ist ja innerhalb unserer Zivilisation ganz umgeben von Dingen, deren Sinn ihm fremd bleibt. Das mag denjenigen als unbedeutend erscheinen, die da glauben, für das Menschenleben habe nur das eine Bedeutung, was sich im bewußten Leben abspielt. Gewiß, im Bewußtsein läßt es sich ganz gut leben, wenn man bloß ein Tramwaybillett kauft und bis zu der Station fährt, zu der man fahren will, oder wenn man ein Telegramm empfängt, ohne eine Ahnung zu haben, auf welche Weise es zustande gekommen ist, ohne jemals etwas gesehen zu haben von einem Morseapparat. Für das gewöhnliche Bewußtsein, kann man ja sagen, ist das gleichgültig; aber für dasjenige, was sich in den Tiefen der menschlichen Seele abspielt, ist es eben nicht gleichgültig; der Mensch in einer Welt, deren er sich bedient, und deren Sinn er nicht versteht, ist wie ein Mensch in einem Gefängnis ohne Fenster, durch das er in die freie Natur hinausschauen könnte.

Von dieser Erkenntnis muß Erziehungs- und Unterrichtskunst gründlich durchzogen sein. Indem der Mensch, wie ich gestern charakterisiert habe, in die Differenzierung nach Mann und Frau eintritt, wird er auch reif, in die anderen Differenzierungen des Lebens einzutreten, und er muß eben in das wirkliche Leben eingeführt werden. Daher nehmen wir, wenn das geschlechtsreife Alter bei unseren Waldorfschulkindern herannaht, so etwas wie Spinnerei, Weberei in den Schulplan auf. Natürlich erwächst einem dadurch eine große Aufgabe, und es ist schwierig, den Schulplan zu bearbeiten, wenn man die Tendenz verfolgt, in diesen Schulplan vom geschlechtsreifen Alter an alles das hineinzubringen, was den Menschen zu einem lebenspraktischen Menschen macht; das heißt, zu einem solchen, der in der Welt mit Verständnis drinnensteht. Wir kämpfen ja natürlich in der Waldorfschule auch mit den äußeren Opportunitäten des heutigen Lebens. Wir müssen ja die Schüler und Schülerinnen dazu bringen, daß sie eventuell eine Universität in dem heutigen Sinne, eine technische Hochschule und dergleichen besuchen können. Wir müssen daher all dasjenige auch in den Lehrplan hineinbringen, was wir vielleicht sonst für unnötig halten würden, was aber aus dem angedeuteten Grunde hinein muß. Gerade für diejenigen Schüler und Schülerinnen, die das geschlechtsreife Alter erreichen, den Schulplan möglichst seelisch-ökonomisch einzurichten, das ist schon etwas, was einem recht schwere Sorge macht. Es macht viel Mühe, aber man kann es. Man kann es dadurch, daß man eben gerade selber einen Sinn entwickelt für die Hauptsache des Lebens, und diese in möglichst ökonomischer Weise dann an die Schüler und Schülerinnen heranbringt, so daß sie auf die einfachste Weise erkennen lernen, was sie eigentlich tun, wenn sie ein Telephongespräch empfangen oder aufgeben, was der Tramway tut mit den ganzen übrigen Einrichtungen und so weiter. Man muß nur in sich die Fähigkeit entwickeln, bis dahin zu kommen, daß alle diese Dinge möglichst auf einfache Formeln gebracht werden; dann kann man diese Dinge durchaus im entsprechenden Lebensalter sinngemäß an die Schüler und Schülerinnen heranbringen. Denn das ist es, was angestrebt werden muß, daß die Schüler und Schülerinnen mit dem Sinn unseres Kulturlebens durchaus bekannt werden. - Man muß nur schon im chemischen, im physikalischen Unterricht alles in der Weise vorbereiten, wie es eben wiederum für das betreffende Lebensalter vor der Geschlechtsreife taugt, damit man wiederum in möglichst ökonomischer Weise die ganz praktischen Seiten des Lebens darauf aufbauen kann, wenn die Geschlechtsreife eingetreten ist.

Da kommt natürlich auch schon das in Betracht, daß ja die Schüler und Schülerinnen nunmehr in das Alter eintreten, wo sie in einer gewissen Weise differenziert werden müssen darnach - natürlich einzelne auch wiederum nach anderen Richtungen -, aber darnach vor allen Dingen, ob sie einen mehr geistigen Beruf oder einen mehr handwerklichen Beruf ergreifen. Dabei muß durchaus berücksichtigt werden, daß eine auf wirkliche Menschenerkenntnis gebaute Erziehungskunst ja wie als etwas Selbstverständliches erkennt, daß die einzelnen Glieder der menschlichen Natur nach Totalität hinstreben. Es muß nur immer eine Einsicht vorhanden sein, wie diese Totalität angestrebt werden soll. Man muß natürlich diejenigen Schüler und Schülerinnen, die ihrer besonderen Begabung nach für mehr geistige Berufe taugen, in diesem Sinne erziehen und unterrichten. Aber dasjenige, was auch in den späteren Lebensaltern einseitig in dem Menschen heranentwickelt wird, muß in gewissem Sinne durch eine andere Entwickelung wiederum zu einer Art Totalität erhoben werden. Wenn wir auf der einen Seite dem Schüler und der Schülerin Willensimpulse beibringen, die nach einer mehr geistigen Seite gehen, dann müssen wir die Erkenntnisseite denn der astralische Leib verlangt, wenn er seine Willensimpulse nach einer gewissen Seite hin ausbildet, daß die auch in ihm liegenden Erkenntnisimpulse nach der anderen Seite des Lebens auch ausgebildet werden -, wir müssen die Erkenntnisimpulse dann so ausbilden, daß der Mensch wenigstens eine Einsicht hat und zwar eine anschauliche Einsicht in Gebiete des praktischen Lebens, die ihm einen Sinn beibringen für die Gesamtheit des praktischen Lebens.

Es ist zum Beispiel in unserer Zivilisation durchaus ein Mangel, wenn sich, ich will einen extremen Fall nennen, Statistiker finden, welche in ihre Statistiken einsetzen, wieviel in einem gewissen Territorium an Seife verbraucht wird und keine Ahnung haben, wie man Seife fabriziert. Niemand kann mit einem wirklichen Verständnis den Seifenverbrauch statistisch konstatieren, wenn er nicht eine Ahnung davon hat, wenigstens ganz im allgemeinen, wie man Seife fabriziert.

Sie sehen, weil ja das heutige Leben so kompliziert geworden ist, daß die Dinge, die man zu berücksichtigen hat, fast schier unermeßlich sind, wird da ganz besonders das Prinzip des Seelisch-Okonomischen die größtmögliche Rolle spielen müssen. Das Erziehungsproblem, das auf diesem Gebiete vorliegt, ist eben: in ökonomischer Weise das herauszufinden, was für dieses Lebensalter getan werden muß. Es könnte leicht getan werden, wenn uns nicht immer noch die Schlacken von allen möglichen Erziehungsveranstaltungen im Leibe steckten, die nun traditionell heraufgekommen sind in die Gegenwart und die eigentlich dem gegenwärtigen Leben gegenüber keine Berechtigung haben.

Der Grieche würde ein sonderbares Gesicht gemacht haben, wenn man die jungen Leute zunächst, bevor sie ins griechische Leben hineingestellt worden sind — etwa so ähnlich, wie wir das bei unseren Gymnasiasten tun -, in das Ägyptische oder Chaldäische eingeführt hätte. Aber über diese Dinge läßt sich noch gar nicht sprechen, weil wir ja die Opportunitäten des heutigen Lebens eben durchaus berücksichtigen müssen.

Nun handelt es sich darum, in möglichst umfassender Weise denjenigen, der sich einem mehr geistigen Berufe zuwendet, mit den Dingen des äußerlichen handwerklichen Lebens bekanntzumachen, und umgekehrt denjenigen, der sich dem handwerklichen Leben zuwendet, soweit er urteilsfähig wird, in gewissen Grenzen mit dem, was den Menschen als geistiger Beruf zugeführt wird. Dabei muß betont werden, daß es durchaus wenigstens angestrebt werden muß, diese praktische Seite des Lebens durch die Schule selbst zu pflegen. Auch das Handwerkliche sollte nicht eigentlich dadurch gepflegt werden, daß man die jungen Leute sogleich unter die Erwachsenen in die Fabrik steckt, sondern man sollte innerhalb des Schulmäßigen selbst die Möglichkeit zur Hand haben, die praktische Seite des Lebens zu berücksichtigen, damit dann der junge Mensch dasjenige, was er in einer kurzen Zeit, ich möchte sagen, bildlich gesprochen, am Modell sich angeeignet hat, in das praktische Leben übersetzen kann. Das Aneignen am Modell kann nämlich so praktisch sein, daß durchaus die betreffende Sache ins praktische Leben hineingetragen werden kann. Ich sehe auch nicht ein, da es doch einmal in unseren Gefängnissen gelungen ist, die Gefangenen so arbeiten zu lassen, daß sie Dinge fabrizieren, die dann im Leben draußen irgendeine Rolle spielen, warum nicht auch in den Schulwerkstätten Dinge sollten fabriziert werden, die dann einfach ans Leben hinaus verkauft werden könnten.

Aber daß der junge Mensch möglichst lange in dem schulmäßigen Milieu bleibt, das allerdings dann gesund sein muß, darauf ist zu sehen; denn es entspricht eben einfach der inneren Wesenheit des Menschen, nach und nach an das Leben heranzutreten und nicht mit einem Stoß in das Leben hineingeführt zu werden. Weil das Alter so wenig verstanden hat, was mit der Jugend anzufangen ist, deshalb haben wir ja heute die wirklich schon im Internationalen drinnenstehende Jugendbewegung, eine Bewegung, welche von den Alten heute am allerwenigsten in ihrer tiefen Berechtigung verstanden wird. Sie hat eine tiefe Berechtigung und müßte durchaus in dieser tiefen Berechtigung verstanden werden. Sie müßte aber auch in die richtigen Wege geleitet werden. Und das kann im Grunde genommen nur dadurch geschehen, daß das Erziehungswesen in die rechten Wege geleitet wird.

Das ist es, was wir vor allen Dingen im Waldorfschul-Prinzip anstreben: möglichst den Menschen an das Leben heranzubringen, damit er im Beginne der Zwanzigerjahre, wenn das eigentliche Ich in freier Handhabe sich in die Welt hineinstellt, auch wirklich das rechte Weltgefühl entwickeln kann, damit er sich dann auch wirklich in einer Welt drinnen fühlen kann, von der er die Empfindung zu empfangen in der Lage ist: Ich habe Mitmenschen, die sind älter als ich, die haben die frühere Generation gebildet. Diese früheren Generationen haben alles das hervorgebracht, dessen ich mich nun bediene; aber ich habe eine Gemeinschaft mit diesen früheren Generationen. Ich verstehe dasjenige, was sie in die Welt hineingestellt haben. Ich setze mich nicht bloß auf den Stuhl, den mir mein Vater hingestellt hat, sondern ich lerne verstehen, wie dieser Stuhl zustande gekommen ist.